december 2003

Shuen-shing Lee is Associate Professor in the Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures at the National Chung Hsing University, Taiwan. In 1998 he created one of the first Taiwanese websites devoted to Chinese hypertext literature. He is investigating the interlaced poetics of representation and simulation in digital literature and computer games. Lee has published two novels.

"I Lose, Therefore I Think"

A Search for Contemplation amid Wars of Push-Button Glare

by Shuen-shing Lee

Introduction

This paper investigates a small group of computer games imbued with socio-political critique, putting forward perspectives and readings on design conventions and poetical observations in the game field. Socially or politically critical games involve a careful examination of certain aspects of society, often self-reflexively criticizing the dominant tendencies of the game industry itself. They appropriate and twist the established gaming models and schemas of popular games. These re-calibrations challenge the supposition that games equal fun. They appeal to new audiences, offering alternative goals such as meditative play or off-gaming engagement, very often by way of pain, rather than pleasure. The artistry achieved by these games transcends the scope delimited by the emerging poetics of games, uniformly based on popular examples.

1. Games You Never Win

Gonzalo Frasca, the webmaster of ludology.org, declares that it is almost impossible to "find 'serious' computer games," particularly in the case of tragedy. He contends that the binary win-lose logic of games induces players to wield means of any kind in order to win and thus easily corrupts any seriousness implicit in their content. For instance, one mechanism that dilutes the intent of serious computer games is replayability or action-reversibility, which undermines the signification of the linear progression toward death defaulted in conventional tragedy (Frasca, 2001b). Frasca's approaches, rooted in conventional tragic forms, may be justified in certain computer games, but he may overlook the possibility that computer games possess serious or tragic forms of their own.[1] A “you-never-win” game could be considered a tragedy, for example, a game with a goal that the player is never meant to achieve, not because of a player's lack of aptitude but due to a game design that embodies a tragic form. In Stef & Phil's New York Defender (2002), for example, no matter how frantically a player shoots down airplanes aimed at the twin towers, he is doomed to fail because the number of airplanes increases exponentially in relation to his firing. Gaming within the context of 9-11 and the shadow of terrorism, one easily sympathizes with the defender's inability to protect the twin towers, or symbolically our society, which projects a tragic sense of powerlessness and hopelessness in confronting terrorism, as Clive Thompson (2002) points out.

Another more stylistically decorative example of the same un-winnable form is, interestingly, Frasca's own Kabul Kaboom (2002). He used to proclaim that "there is a lack of 'serious' videogames that use the medium as a way to make a philosophical point of view or to share an artist's perception of reality" (Frasca, 2001b). Kabul Kaboom definitely answers the call implied by this statement, judging from the timeline.[2]

The beginning of the year 2002 witnessed a series of US military operations against Afghanistan's Taliban regime. The US air force attacked the Taliban to paralyze its communications and simultaneously air-dropped food, aiming to relieve the devastated civilians on the ground. Frasca illustrates this moment of moral contradiction in an interactive environment by juxtaposing two symbols, bombs and hamburgers, swooping down from the sky. The avatar is meant to grab as many hamburgers as she can while avoiding the pouring rain of bombs. Once she gets hit, the screen advances to a static scene crowded with body parts, debris and rubble and two observers, uttering: "Mmm, yummy." The message is hard to miss. Never can a life be made worse or more tragic, being so mercilessly trampled: to survive in a no-exit space with endless warfare going on, the civilian victim chases and dodges, receives and rejects simultaneously, doomed to perish indignantly within moments. The creative aesthetic of the game is more realized with hamburgers than it could be with any other form of food because "hamburger" is a common slang term for "mutilated bodies" (as in "Hamburger Hill", the particularly bloody Vietnam War battle).[3]

Despite its extremely time-worn arcade model, Kabul Kaboom is distant from pure entertainment, mostly due to its powerful irony. Another tour de force of the work resides in Frasca's appropriation of Picasso's "Guernica" (1939). The figures of a wailing mother with a dead baby in her arms, cropped from "Guernica," are relocated to the interactive situation and assigned the avatarship. Situated in the air-raids, the avatar acts out the misery of the weak inflicted by wars. This skillful integration of representation and simulation accounts for the artistic success of the work. It draws upon Picasso's masterly pictorial narration of war atrocities and reprocesses the same theme through simulation, which allows the player to create the experience through what Craig A. Lindley calls "a pattern of perceptual, cognitive, and motor operations" (2002b).

2. Trial-and-Error Breakout

New York Defender and Kabul Kaboom land jabs of black humour on the well-entrenched trial-and-error template of computer games. In both games, retrial improves nothing, but only intensifies the sense of impotence and tragedy. This breakout constitutes a critique of game design, a rear-viewing of popular computer games that have been unconsciously reiterating the concept of trial-and-error without much modal innovation.

The cover page of Kabul Kaboom says: "Remember kids, you can't win this game, just lose." Actually, the un-winnable form has had a relatively long history in arcade games. It aims to measure its players' ability to endure a particular situation, thereafter ranking their positions on a score chart. In Berzerk (1980) the avatar fights till he dies. Another example, and one which is readily available on the internet, is Ferry Halem's Hold the Rope (2001). Its gamespace features a tug of war between a rhinoceros and five contesting avatars. The player's job is to continually click the five participants, a symbolic move of energy boost. When one of the contestants uses up his energy, the team is pulled away by the rhinoceros. Players cannot beat the rhinoceros, as such is the design. Nonetheless, the goal of the game is to break the record set by previous players. In terms of the score chart, it is a game of competition among players. Agônal (competitive) games are molded on the binary logic of win-lose. This opposition also applies to Hold the Rope in the sense that the win-lose rule is effected in the relationship between players, rather than between the machine and the player. Accordingly, trial-and-error repetition still works in games of this type since retrial will normally improve a player's score in competition with others.

New York Defender and Kabul Kaboom both undermine the rigid formula of a score chart, thus nullifying the concept of competition among players,[4] and restoring the win-lose struggle between the player and the machine. The you-never-win form is totally unfavourable to both games' players, but, most significantly, this particular form assumes an aesthetic correspondence to the content of the games – these games assert that there is no winner in a situation in which buildings are toppled or bodies are turned into "hamburgers," and the form reflects and strengthens this message. This incorporation of gaming into social critique also transcends the convention dictated by entertainment consumerism. This mixture is claimed to be pioneered by Eugene Jarvis' Narc (1988), an early arcade game. In an interview, Jarvis narrates his motivation of injecting "something more" into games: "it seems like so rarely does a videogame make any kind of statement about anything – it's always a battle against some generic army, or the space aliens, or the little munchkins. You never see any kind of political statement or any kind of topicality" (Herz, 1997). Narc embodies an anti-drug statement by providing an arena for players to manoeuvre some drug busting officers (narcs) to blast away an army of drug-dealing related creatures. It turns out to be an interactive version of action movies with "a little Schwarzenegger hard edge," as Jarvis acknowledges (Herz, 1997). Despite its intention of social critique, its storyline does not go beyond the over-simplified schema of good versus bad. Only to further weaken its proclaimed critique, the game, conceived in the typical contours of shoot 'em ups, duplicates the un-reigned violence indulged in action movies and games. It thus succumbs to the trend prevalent in the entertainment market, itself another target for social critique.[5] In terms of its critical aspect, the game is only marginally successful. However, its call for "something more" anticipates the current promotion of computer games as a tool of alternative expression. In contrast, New York Defender and Kabul Kaboom both break out of the confinement of the good versus bad pattern, along with the hollow heroism embedded therein. Faithfully addressing painful issues of the real world, both games "show" their message in action rather than "tell" it in a non-interactive statement, an accomplishment made possible mainly by the anti-competitive twist of the you-never-win form.

3. "I Lose, Therefore I Think": Alternative Goals in Games

After examining several essential elements in computer games, Greg Costikyan achieves "a functional definition of 'game' [as] an interactive structure of endogenous meaning that requires players to struggle toward a goal" (2002). Both New York Defender and Kabul Kaboom meet the definition at first glance. However, one close look at the goal in these two games erodes one's certainty. According to Costikyan, a goal in games may be explicit or implicit (2002). In Pac Man, the player commands his avatar to gobble up dots, evade ghosts and advance to further levels, in quest of the highest rank on the score chart. A game such as SimCity, however, as Costikyan observes, "has no inherent 'win-state,' no explicit, built-in goal for the game. SimCity works because it allows players to choose their own goal, and supports a wide variety of possible goals."[6] This is particularly the case for MUDs and MOOs, wherein players, in general, are encouraged to motivate themselves towards a goal of their own.

Put another way, Costikyan's concept of an explicit goal rotates around a definite end, in the quest of which all the game's elements are meant to be supportive. Games of such kind are usually centralized in structure. Costikyan's idea of implicit goal, to the contrary, refers to a networked environment wherein only the player-selected elements in a gameplay attain significance in response to an emerging centre based on the player's motivation. This player-centric design contributes to the formation of a de-centralized structure in games. Explicit or implicit, centralized or dispersed, directly provided or indirectly supported by games, goal is the ultimate fulfilling factor in what we know of computer games so far. Viewed in this manner, the goal in both New York Defender and Kabul Kaboom proves to be to lose.

This unusual goal does not denote the regular terminal point of a game toward which the player's effort is directed. It is a metaphorical end, en route to which a specific kind of player is able to realize the implications of "to lose" in an intentionally un-winnable form. These particular players can be termed "second-level model players." Modified from Umberto Eco's definition of model readership, the second-level model player is here designated as an off-gaming thinker, "who wonders what sort of player that games would like him or her to become" and, most significantly, "who wants to discover precisely how the designer goes about serving as a guide for the player." This off-gaming thinker, an inquirer into the designer's strategy, is the opposite of the first-level model player who, solely concerned with conquering hurdles or solving riddles, "wants to know, quite rightly, how the game ends" (Eco, 1994). [7]

To lose is a common result in agônal games, especially in the early stage of a given gameplay. "I lose, therefore I think, so as to figure out a strategy toward the win state": This is a "player response" overtly desired by game design mandated by the trial-and-error notion. In order to stop the player from advancing through the game too quickly and to get him to think, the protocol of difficulty level arises. In Costikyan's opinion "A game without struggle is a game that's dead," but he also reminds designers that games have to be balanced between being too easy and too difficult, in order not to scare off the players" (2002). Other critics also share the same perspective. According to Aki Järvinen, for instance, games have to be "challenging" to be fun (2002). In this light, to lose denotes a temporary setback rather than an ultimate consequence of gaming. Inverted in this manner, the game design in New York Defender and Kabul Kaboom dictates absolutely that player lose, affording the player little room to hang about in the un-winnable struggle. A player's score is an empty sign. His effort to stave off death in these game spaces through retrial is futile, only signifying a possible misunderstanding of the games. They are dead games, by Costikyan's criteria. However, it is not until the games go belly up that their ulterior motive emerges. Both games are meant to morph the player from an in-gaming loser into an off-gaming thinker, an observation shared but not well elaborated in Thompson's report of a group of political games: "These games aren't trying to get you hooked or make your thumbs sore. They're trying to make you think" (2002).

4. "De-Gaming" Games

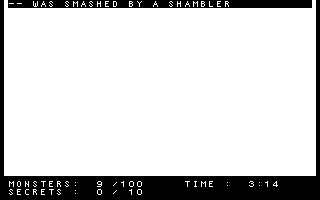

The socio-political critique inherent in both New York Defender and Kabul Kaboom readily manifests itself in their gameplay, but their meta-interrogation of game design such as the trial-and-error routine is less apparent. In the same spirit of social critique, Jodi's series of "de-gaming" games (Jim Andrews' term) places games of violence in the crosshairs, not concealing its intentional twist of the original sources. For instance, Arena, one from the series, plays upon Quake in a minimalist manner. In an extensive sense, the game is a toddler's aping of first-person shooters seeking Doom-style violence. Arena provides the commonly defaulted setup seen in games of Quakeian variants, including button-pushing (the "enter" key and "space bar") for firing and jumping, numerical indicators for arsenal and health status, textual notes of weapons and cells obtained, number of monsters killed and secrets unfolded at the end of the game. The sound effects from the battle assault one's ears, alloying alien creatures' roaring, the avatar's deep moaning and the bang of shooting guns. Except for some occasional flashes of glare, the screen remains blank white as the noise persists (see Figure 1). That is, it is a game of violence without visual display. An aural game, it features violence-related sounds as its major mode of representation. The blank screen of the game begs further exploration.

Figure 1. The game-over scene of one session of gameplay in Arena.

The screen remains blank the entire time.

There is play between absence and presence in Arena.[8] It is important to recognize that, without direct reference to Quake or other such games, Arena would be deprived of its critical force, the sole gaming perception worth attention. The critical force springs up from the gameplay in affiliation with players' memory (mental presence) of violence prevalent in games, as the kind evoked by an overview of Quake: "Arm yourself against the cannibalistic Ogre, fiendish Vore and indestructible Schambler using lethal nails, fierce Thunderbolts and abominable Rocket and Grenade Launchers" (id, 2003).[9] In other words, its critical force is initiated by the physical absence of the most essential element in violent games: the visual effect. This absence invites the player to fill the space, a spontaneous move induced by the violent ambience triggered by his button-pushing/ shooting. One scene in Stuart Moulthrop's Victory Garden (1991), a hypertext novel, reflects a like moment. Veronica and Harley, two of the characters, notice something unusual as they step into a favourite café:

Veronica stalled with one foot over the threshold, causing Harley to bump against her shoulderblades. Something wasn't right there. It rolled right up and hit her in the face.

"No music?" Harley noticed, a beat late.

Absence is presence. There was not a trace of melody in the [café] . . . . ("No Music")

In the café, music has been turned off, all the patrons focusing their attention on a television screen running breaking news from the Gulf War. The shock Veronica and Harley experience arises from the absence of something they are used to, one of the elements that defines the space they have entered. At this moment of realization, being "hit in the face," "absence is presence." That is, the missing object gains a stronger presence through the raised tension of unmet expectation. Arena takes the player to the same "café without music," or "a soap opera going on without actors in sight"—and he catches the beat effortlessly and unconsciously due to his familiarity with the narrative schema. Absence and presence interact in a way similar to that of the Taoist concepts of yin and yang, complimenting and intertwining endlessly toward the completion of a life, or in the case of Arena, the formation of a critique.

The gaming perception generated by Arena may differ from the common experiences derived from playing regular games of violence, wherein gaming models repeat themselves endlessly. As Mez (2002) points out in her unique language termed "mezangelle":

::these reworked quake "instances"

::r more profound than the ty.pica.][she][ll][ed][y repetitious

::pleasure-loadings derived from playing the original.

It is "more profound" mainly because the noisy void provides a venue for players to be struck with the essence of violent games. The whited-out surface metaphorically pinpoints the existence of the inner circuits in violent games that tend to acclimate the player's mentality to loops of gaming routs, eventually turning him into a "smart" mouse fully integrated with sets of gaming rules. Admittedly, retrial of gaming rules enhances the player's eye-hand coordination, but violent gaming, absent of content, confines or dwarfs his mentality to a primitive biological stage. The blankness of Arena, therefore, is a gesture of protest, a critique of the excess of senseless violence in games.

Brody Condon's Adam Killer (2001), a modified version of Half-Life, also serves a critical purpose in relation to the issue of violence. Instead of alien combatants, Condon installs a photograph of his friend Adam Frelin as the opposing figure in the game and has it duplicated, stuffing the scenario full. This modification, or to be exact, distortion of the original version wherein the goal is to gun down all the opponents and win the battle, intrigues one to look deeper into the game's intention. The shooting of this Adam figure frightens one in a certain way by conjuring up the memory of the Columbine shooters, who, as Condon reminds us, have mimicked Doom. This terror mainly takes origin in one's realizing that while Adam Killer is "the mixture of game elements and real representations in game space," the Columbine shooters' action was "a mixture, or a 'mapping', of game elements and real elements in real space" (Condon, 2002).[10] In the gameplay of Adam Killer, the mixture might make some fun-seekers uneasy with "trigger happiness," since the shooting is distinct from that executed in confrontation with a horde of monsters or an army of anonymous pawns.

In his discussion of Doom, Aarseth comments: "The sheer intensity of the game play is far more striking than the blood effects and violence, which are repetitive and subrealistic" (1999). This observation more or less applies to Half-Life games. Nevertheless, in Condon's twisted space, the intensity of the gameplay is downplayed while the "repetitive and subrealistic" "blood effects and violence" undergoes an artistic elevation with the application of trailing visual effects. The trailing technique morphs the blood-shedding action into an abstract performance of visuality. To enhance this effect, Condon purposefully opts for a white dimension and figures dressed in white in contrast to the meshed effects of red blood, redirecting the gamespace from a violence-driven simulation into an aesthetic perspective (2002). The trailing effect has long been practiced in digital post-production but its application in shooting scenarios is rare, a fresh stroke reminiscent of such stunning visual effects as the slow-motion bullet time in Max Payne.[11]

These two innovations, the incorporation of a real identity into a gamespace and the visual reconfiguration of violence, as critics suggest, convey "a strongly reflexive and ironic stance towards established computer game form" (Lindley, 2002a). The combination of real and surreal or artificial disrupts the player's gaming habitus and diverts him to the dimension of social critique. The trailing effects transcribe violent action into visual signs of abstract quality, thus turning the player's shooting into participation in performance of art. Replacing the original space with a twisted one, Adam Killer works in the same way as Arena does in breaking down the conventional presentation of violence in games. In a way, each game’s critical force is drawn from parodying its counterparts, analogous to Henry Fielding's Shamela playing/ preying upon Samuel Richardson's Pamela.

5. Time and Pleasure in Twisted Spaces

Computer games, as "the art of contested spaces" (Squire and Jenkins, 2002), unanimously embrace a set of rigidified design and gaming conventions, assumed to be indispensable to entertainment. For instance, the trial-and-error principle persists in game design in accordance with the belief that difficulties excite players' desire to conquer. Critical games take one step further to convert contested spaces into twisted ones by perverting conventions for purposes beyond pure entertainment. Apart from design and gaming conventions, critical games also call into question the time and pleasure of games observed by critics. Aarseth proposes three types of time involved in interaction: event time, negotiation time and progression time. Event time refers to the duration of an event in a game. Negotiation time is time running outside the game, "where the possible event times are tested, varied, until a sufficiently satisfying sequence is reached, or not reached." "If it is reached," Aarseth continues, shifting to the definition of the progression time, "a third level of time has been affected: that of progression of the game from beginning to end" (1999). After this delineation of time, Aarseth infers: "The negotiation level may… be structurally different from game to game but the user's strategy of gaining experience by varying a difficult maneuver until a useful technique is reached, is the same for every game" (1999, italics mine). Applying these time levels to New York Defender and Kabul Kaboom, one finds that players are doomed to get stuck forever in the negotiation level for the reason that the un-winnable form precludes the development of "a useful technique" for progression. It is also unneeded in Arena, wherein there are no visual venues for one to improve. In the case of Adam Killer, the negotiation level will not arise from the gameplay at all because the win-lose mode is completely eliminated.

While some players might quit an un-winnable game out of sheer frustration, other players might proceed from the level of negotiation to a cognitive interaction with the game's puzzling design. Subsequently the cognitive inquiry may evolve into the level of recognition: not only realizing the anti-denouement design but also the symbolic meaning of the you-never-win form in aesthetic correspondence with an implanted political message. This recognition emancipates the game from the claw of win-lose logic, turning the game (ludus) of motor action to play (paidia) of cognitive exploration,[12] wherein the form and the political message echo each other, fashioning the gamespace into a thinkspace. Aporia, a dilemma or a difficult moment in making decisions in games, exists in the time span of negotiation. When negotiation grows into recognition, this aporia is dissolved and the emotive state of the player advances into epiphany, "a sudden, often unexpected solution to the impasse in the event space," as defined by Aarseth (1999). However, in the cases of the cited un-winnable games and Arena, the recognition-initiated epiphany does not equal the pleasure arising from an in-gaming resolution. Instead, it provides enlightenment into the games' critical design from an off-gaming position.

Georg Lauteren divides "the pleasure of the playable text" into three categories: "the psychoanalytical, the social and the physical form of pleasure" (2002). One common feature shared among these three types of pleasures in games, based on his analysis, is immersive identification either with a character or a community in a plot. Pleasure of engagement, different from that of immersion, is only slightly hinted by Lauteren in his citing Fiske's differentiation "between the pleasures of popular culture and that of critical and aesthetic distance" (2002). A clear contrast of these two types of pleasure can be found in J. Yellowlees Douglas and Andrew Hargadon's (2000) "The Pleasure Principle: Immersion, Engagement, Flow":

The pleasures of immersion stem from our being completely absorbed within the ebb and flow of a familiar narrative schema. The pleasures of engagement tend to come from our ability to recognize a work's overturning or conjoining conflicting schemas from a perspective outside the text, our perspective removed from any single schema. Our enjoyment in engagement lies in our ability to call upon a range of schemas, grappling with an awareness of text, convention, even of secondary criticism and whatever guesses we might venture in the direction of authorial intention.

Enlightenment into the critical design of games belongs to the pleasure of engagement. In actuality, critically biting messages, reconfigured forms, distorted gaming etiquettes and design principles all display a bent towards suspending the player's in-gaming immersion in favour of augmenting his off-gaming engagement.

6. The Unregretful, Objective Player

Geoffrey R. Loftus and Elizabeth F. Loftus's Mind at Play, a pioneering study of videogames, sorts out two types of psychological configurations embedded in game design that aim to get players addicted to gaming. The first type, "partial reinforcement," is that utilized by slot machines which spit out coins intermittently to reward a gambler. The experience of being occasionally rewarded often drives the gambler to continue inserting coins, in hopes of another win or even a jackpot. Arcade game designers have cloned the same reinforcement strategy in their games. Surprises such as score doubling, weapon upgrading, expedient level advancing may pop up randomly during the gaming process to heighten the player's intrigue, stimulating continued playing (Loftus and Loftus, 1983). Game designers also weld the notion of "regret" into circuits, according to Loftus and Loftus. Psychologists propose that the less the difference between one's reality and its "alternate world," the more regret one gets. For instance, two passengers have missed their respective flight "in equal difficulty," but one is late for two minutes while the other late for half an hour. The former usually experiences worse regret, since the discrepancy between his reality (two minutes late) and the alternate world (catching up the flight) is much less. In the gaming process, a wrong decision that ends the game (the reality) usually makes the player regret not having advanced to the next level or cracked the game (the alternate). When tuning the difficulty for a level of a game, designers attempt to minimize the distance between advancement and failure, thus maximizing the degree of regret in the player's response, or, in other words, augmenting the possibility of the player's inserting more quarters or reloading the previously saved game to assuage his regret (Loftus and Loftus, 1983).

These addictive elements are dissolved in the critical games cited above. Though their gaming forms remain within arcade game conventions, particularly that of shoot 'em-ups, these critical games are hardly conditioned by entertainment consumerism. They do not cater to a consumer mentality, sometimes even taking the arcade game genre as a target of critical charge. In short, they possess a proclivity to transform one into an "unregretful" player. This observation leads one to a reconsideration of Julian Kücklich's remark concerning players' split identity in games. In his semiotic approach to the issue of game versus narrative, Kücklich (2002) detects two modes of interaction from gameplay:

From the perspective of the player, his or her actions make sense as a direct response to the fictional world of the game. This is what I call the mode of aesthetic interaction. From the perspective of the observer, the player's individual interactions with the game are only meaningful as a textual strategy, alternatingly in accord with and directed against another textual strategy of the game. This is what I call the mode of hermeneutic interaction.

Kücklich's player is constituted by two entities, one an aesthetic subjectivity and the other a hermeneutic objectivity. The two entities, however, are not parallel but intersect each other along a gameplay. The hermeneutic objectivity is always outside a game, while the aesthetic subjectivity is inside, immersed in the game. But it should be noted that, according to Kücklich, there is an interactive relation between the objective player and the subjective entity, since the objective player's position and the subjective entity's perception shape and condition each other. Kücklich's concept is derived from his imagining the player's mental evolution in a gameplay: "when I observe myself playing a game, a curious thing happens: The player becomes less and less of me, and more and more a part of the game" (2002).

Contrary to Kücklich's observation, in the longer process of critical game playing to investigate and understand what it is all about, what happens to the player is that he becomes less and less of the game, and more and more of "me." That is, the player will eventually retreat from the games and become a pure hermeneutic objectivity. Still, this new-born objective player differs somewhat from Kücklich's version. What concerns Kücklich's objective player most is the strategy design. It is design strategy, however, that the critical games' objective player is intrigued to look into, after realizing the futility of gaming strategies in the gamespace. The objective player and the game designer form a relation similar to that between the decoder and the encoder. But this relation does not implicate that there is an arbitrary message to be mediated through games and to be decrypted by the player, a move usually derogated as intentional fallacy. The cited critical games provoke one to quit and continue gaming paradoxically at the same time. The more you shoot, the more you realize that you're not shooting towards any win-oriented goal. Once the player becomes an objective player, he has stopped playing in the diegetic level, though he is still shooting. At this point of gameplay, shooting or evading missiles in the critical games transforms play from a gaming action into a thinking event, from a means of fun-seeking to a schema for the revelation of the games' critical engagement.

7. The Rise of Art Games

In terms of mainstream popular games, the critical examples cited above can be defined as "pseudo-games" or "texts in the guise of games," as Marie-Laure Ryan [13] suggests to me in reference to Kabul Kaboom:

To what extent is Kabul Kaboom a game? If games are supposed to bring playing pleasure, it certainly does not qualify. The only interest resides in the theme and message. It could be viewed as a satirical artwork that parodies the game form, without being a game itself. Similarly, there are some novels, especially by Italo Calvino, that take the external form of games, but aren't really playable. Kabul Kaboom may be playable, but it certainly isn't worth playing.

However, stepping out of the supposition that games equal pleasure, one may suggest, like Frasca does, that "the videogame experience has to be thrilling, but not necessarily fun" (Frasca, 2001a). Artists have become increasingly agitated about equating games and pleasure. Jarvis's declaration of the need for "something more" in games planted a seed of metamorphosis. Its recent embodiments include a series of content-provocative "newsgames" at Newgrounds and the newly launched Newsgaming, a website claimed to be wholly devoted to pristine game design that responds to immediate socio-political issues and happenings. Playing fabulous999's The Suicide Bombing Game (2002) at Newgrounds is fun for those committed to nothing other than score chasing, treating the game simply like one of the early shoot 'em-ups and ignoring the game's political and ideological implications. The gameplay is disturbingly painful, however, to the objective player, able to realize the incidental sensationalism from the Western viewpoint and the socio-political impact in its simulation of a Palestinian suicide bomber on the street.[14] The same disturbance can be perceived in Tom Fulp's Al Quaidamon (2002) at the same site, a game purposefully making itself a difficult gameplay for those players who choose to apply humanitarian options on an Al Quaida prisoner. Playing September 12th (2003), the first shot of Newsgaming, is "chilling" for its intended audience to experience interactively the message that violence against violence brings about endless wars, as currently going on in Middle East. It is noteworthy that the game design echoes an earlier declaration of Frasca's: "It's time to take the game part out of videogames and look more into play and simulation" (Frasca, 2001a). These "entertaining games with non-entertainment goals" or "social impact games" (Marc Prensky's terms) have successfully alienated themselves from the fun-quest trend of popular games. Lacking fun, these games have enjoyed new audiences on the internet, an open medium that plays an indispensable role in promoting them.[15]

I tend to assign these works, critical or arguably sensationalistic, to a subgenre called art games, following Tiffany Holmes' suit (2002), mainly because of their reconception of gaming form, their alternative goals, such as meditative play or off-gaming engagement, and their appeal to new audiences in cyberspace.[16] These elements contribute to the uniqueness of art games and their rapid ascendance on the internet. Art games' ideal player is the second-order model player but they also have the strong inclination to transform the general player into an "unregretful and objective" one. Conceptualized in this direction, art games, in most occasions, defy the generic game poetics derived from popular games, as illustrated above. Distinguished from their popular counterparts, they deserve critical perspectives of their own, rather than those rendering them parasites of popular games. Thematically and formally, they echo the two thrusts pointed out by Lindley and company regarding the current digital art experimentalism: "one concerned with irony and reflexivity in relation to dominant media, and the other being concerned with ongoing formal development beyond the constraints of dominant media structures" (2002a). These new works, along with those pointed out elsewhere by critics,[17] can be considered the first generation of art games, serious in their desire to transform games into a medium of expression for voices unheard, visions seldom seen.

Notes

* I wish to express my gratitude to Marie-Laure Ryan and Game Studies' reviewers for their helpful suggestions and comments. I am grateful to Taiwan's National Science Council for a grant that allowed me to undertake this paper’s research at the University of Baltimore during the 2002-3 academic year.

[1] To be complicated, one can even argue that games have the potential to become serious ones in response to a player's purposive development. A digital tragedy could consist of a consequence derived from a player's aptitude being so poor that he is never able to break through a riddle or a check point and is therefore pathetically stuck somewhere within the game, devoid of strength and resources, able only to see his lover slain or his virtual life-time drain away. In this light, a computer game may be a tragedy for some while a comedy for others, regardless of what is intended by the game's design.

[2] It should be noted that this call for critical games first appears in his master's thesis (2001c), Videogames of the Oppressed: Videogames as a Means of Critical Thinking and Debate.

[3] Scott Ezell, an American friend of mine, responded to Kabul Kaboom and its symbols in the following way (quoted with permission from correspondence):

These images falling out of the sky together create an indirect but powerful irony. Hamburgers are a symbol of America, both as they are conceived by the world as America's national food, and as they are manifested by the spread of America's fast food culture and franchises across the globe. By pairing hamburgers with bombs, the game's creator asserts that, along with bombs, they symbolize US aggression. Many people have responded angrily to the most powerful nation on earth bombing already destitute and war-torn Afghanistan, and especially to the arrogance with which civilian casualties were dismissed as regrettable but necessary. The addition of hamburgers in this scenario broadens the criticism, enlarging it to encompass economic and cultural aggression. As mutilated bodies are often referred to as "hamburger" (cf. the particularly bloody Vietnam battle nicknamed "Hamburger Hill", from which the film of that name is derived), Frasca suggests through this pairing that the food drop on Afghanistan is hypocritical (delivering charity to those you have just bombed) and that the larger food drop of fast food across the world is similar, if less direct, as an imposition of cultural imperative and political will. The irony takes on shades of black humor, as hamburgers, rather sumptuous and sustaining as foodstuffs go, are certainly not what was dropped to those victims of bombing raids. Rather we can imagine unappetizing canned goods and "K" rations. The game rips the skin off the political rhetoric and apology of the time, depicting America dropping hamburgers from the sky while turning people into hamburger on the ground.

[4] An early version of New York Defender retains the score chart design but it is deleted later.

[5] For an investigation of violence in games, see Celia Pearce (1998), "Beyond Shoot Your Friends: A Call to Arms in the Battle Against Violence."

[6] One reviewer of my paper disagrees with Costikyan at this point, claiming that the game "does have a win-state: you are supposed to be re-elected mayor."

[7] See Eco (1994, 27). The model reader is elsewhere defined by Eco as "a model of the possible reader," whom the author presumes he is able to communicate with in his text, composed of an "ensemble of codes" shared by both sides (1979).Generally, the first-level model reader refers to one inclined to immerse himself into the narrative of the text. The second-level model reader, in contrast, is one inclined to alienate himself from the narrative, aiming at a revelation of the author's writing strategy.

[8] The play concept here is not necessarily related to that discussed in Jacques Derrida's "Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of Human Sciences." Therein, Derrida defines play as "the disruption of presence," a field without a centre or origin but fraught with "infinite substitutions" or supplements (1978).

[9] See the Quake Overview at <http://www.idsoftware.com/games/quake/quake/>.

[10] Condon cites an anonymous screenshot that mimics Doom's interface to compare with the Columbine incident. He claims that his Adam Killer is "very similar in structure to the fake screenshot image" (2002), which represents a first-person shooter's revolver pointing at a real domestic space.

[11] The bullet time effects, according to Geoff King and Tanya Krzywinska, were first introduced in John Woo's action movies and made prominent by the movie Matrix (2002).

[12] Roger Caillois' Man, Play and Games has identified paidia and ludus as the two principles that occupy the opposite poles of a continuum of "jeu" (play and games): paidia activities manifest "a kind of uncontrolled fantasy" while ludus events have the tendency to observe "arbitrary, imperative, and purposefully tedious conventions" (2001). In search for a suitable definition to differentiate play and games, Frasca slightly twists Caillois' neologism and summarizes Caillois' distinction in a formula by way of Andre LaLande: games are dominated by the ultimate goal of win-lose or other similar binary patterns of opposition, while play entails no such goal (1998).

[13] Ryan's suggestions are attached to the readers' reviews of this paper for Game Studies. Andrews' online posting also touches upon the issue of "playability" in reference to Jodi's games: "While jodi achieves an interesting critical engagement with the violent computer game . . . , the game has been de-gamed in various ways – so that it is not 'playable' within the paradigm of a computer game but as an art object" (2002).

[14] Those in favour of violence-against-violence tactics in Palestine's fight for independence from Israel might perceive less sensationalism or none from the game.

[15] Up to August 2002, according to Clive Thompson, "more than 1 million people have played New York Defender, making it an unusually popular statement about the war on terrorism" (2002).

[16] GameLab, an independent game developer, also claims that they "break new ground by finding new audiences," among other things (http://www.gmlb.com). It should be noted that their works, such as "Strain," "Fluid" and "Arcadia," mostly noted for formal innovation, involve themselves less with socio-political criticism in comparison to the examples cited in this paper.

[17] More instances of art games are discussed in Helene Madsen and Troels Degn Johansson (2002), "Gameplay Rhetoric: A Study of the Construction of Satirical and Associational Meaning in Short Computer Games for the WWW" and Tiffany Holmes (2002), "Art Games and Breakout: New Media Meets the American Arcade." Holmes might be the first scholar to use the term "art games" to designate these particular examples.

References

Aarseth, Espen J. (1999) Aporia and Epiphany in Doom and the Speaking Clock: The Temporality of Ergodic Art. In: Ryan, Marie-Laure (Ed.) Cyperspace Textuality: Computer Technology and Literary Theory. Bloomington, Indiana University Press.

Andrews, Jim. (2002) New Games from Jodi. Online Posting, 17 January, dirGames-L, viewed 10 October 2003, <http://nuttybar.drama.uga.edu/pipermail/dirgames-l/2002-January/013507.html>.

Caillois, Roger. (2001) Man, Play and Games. Chicago, University of Illinois Press.

Condon, Brody Kiel. (2001) Adam Killer. viewed 23 January 2003, <http://www.tmpspace.com/ak_1.html>.

Condon, Brody Kiel. (2002) Where Do Virtual Corpses Go. In: Clarke, Andy, Fencott, Clive, Lindley, Craig, Mitchell, Grethe & Nack, Frank (Eds.). COSIGN 2002. University of Augsburg, Augsburg (Germany), September 2 – 4,

Costikyan, Greg. (2002) I Have No Words but I Must Design: Toward a Critical Vocabulary for Games. In: Mäyrä, Frans (Ed.). Computer Games and Digital Cultures. Tampere, 6 – 8 June, Tampere University Press.

Derrida, Jacques. (1978) Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences. Writing and Difference. Bass, Alan (Tr.), Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Douglas, J. Yellowlees & Hargadon, Andrew. (2000) The Pleasure Principle: Immersion, Engagement, Flow. Eleventh ACM Conference on Hypertext and Hypermedia. San Antonio, Texas, United States, 30 May – 03 June, ACM Press.

Eco, Umberto. (1979) The Role of the Reader: Explorations in the Semiotics of Texts. Bloomington, Indiana University Press.

Eco, Umberto. (1994) Six Walks in the Fictional Woods. Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

fabulous999. (2002) The Suicide Bombing Game. viewed 23 January 2003, <http://www.newgrounds.com/portal/view.php?id=50323>.

Frasca, Gonzalo. (1998) Ludology Meets Narratology: Similitude and Differences between (Video)Games and Narrative. viewed 23 January 2003, <http://www.jacaranda.org/frasca/ludology.htm>.

Frasca, Gonzalo. (2001a) Against Replayability. Online Posting, 18 October, Ludology.org, viewed 10 October 2003, <http://ludology.org/index.php?topic=my_2_cents&page=37>.

Frasca, Gonzalo. (2001b) Ephemeral Games: Is It Barbaric to Design Videogames after Auschwitz? In: Eskelinen, Markku & Koskimaa, Raine (Eds.) Cybertext Yearbook 2000. Research Center for Contemporary Culture, University of Jyväskylä.

Frasca, Gonzalo. (2001c) Videogames of the Oppressed: Videogames as a Means of Critical Thinking and Debate. Master's Thesis, viewed 23 January 2003, <http://www.jacaranda.org/frasca/thesis/>.

Frasca, Gonzalo. (2002) Kabul Kaboom. Ludology.org, viewed 23 January 2003, http://ludology.org/games/kabulkaboom.html.

Fulp, Tom. (2002) Al Quaidamon. Newgrounds, viewed 23 January 2003, <http://www.newgrounds.com/portal/view.php?id=42797>.

Halem, Ferry. (2001) Hold the Rope. 23 January 2003, viewed <http://www.orisinal.org/games/rope.htm>.

Herz, J. C. (1997) Joystick Nation: How Videogames Ate Our Quarters, Won Our Hearts, and Rewired Our Minds. Boston, Little, Brown and Company.

Holmes, Tiffany. (2002) Art Games and Breakout: New Media Meets the American Arcade. In: Mäyrä, Frans (Ed.). Computer Games and Digital Cultures. Tampere, 6 – 8 June, Tampere University Press.

id. (2003) Quake Overview. id Software, viewed 23 January 2003, <http://www.idsoftware.com/games/quake/quake/>.

Järvinen, Aki. (2002) Gran Stylissimo: The Audiovisual Elements and Styles in Computer and Video Games. In: Mäyrä, Frans (Ed.). Computer Games and Digital Cultures. Tampere, 6 – 8 June, Tampere University Press.

Jodi. Arena. viewed 23 January 2003, <http://www.untitled-game.org/pc/arena.zip>.

King, Geoff & Krzywinska, Tanya. (2002) Computer Games / Cinema / Interfaces. In: Mäyrä, Frans (Ed.). Computer Games and Digital Cultures. Tampere, 6 – 8 June, Tampere University Press.

Kücklich, Julian. (2002) The Study of Computer Games as a Second-Order Cybernetic System. In: Mäyrä, Frans (Ed.). Computer Games and Digital Cultures. Tampere, 6 – 8 June, Tampere University Press.

Lauteren, Georg. (2002) The Pleasure of the Playable Text: Towards an Aesthetic Theory of Computer Games. In: Mäyrä, Frans (Ed.). Computer Games and Digital Cultures. Tampere, 6 – 8 June, Tampere University Press.

Lindley, Craig. (2002a) The Emergence of the Labyrinth, the Intrinsic Computational Aesthetic Form. In: Clarke, Andy, Fencott, Clive, Lindley, Craig, Mitchell, Grethe & Nack, Frank (Eds.). COSIGN 2002: Second Conference on Computational Semiotics for Games and New Media. University of Augsburg, Augsburg (Germany), 2 – 4 September,

Lindley, Craig. (2002b) The Gameplay Gestalt, Narrative, and Interactive Storytelling. In: Mäyrä, Frans (Ed.). Computer Games and Digital Cultures. Tampere, 6 – 8 June, Tampere University Press.

Loftus, Geoffrey R & Loftus, Elizabeth F. (1983) Mind at Play: The Psychology of Video Games. New York, Basic Books.

Madsen, Helene & Johansson, Troels Degn. (2002) Gameplay Rhetoric: A Study of the Construction of Satirical and Associational Meaning in Short Computer Games for the Www. In: Mäyrä, Frans (Ed.). Computer Games and Digital Cultures. Tampere, 6 – 8 June, Tampere University Press.

Mez. (2002) Jodi's _Untitled-Game_. Fine Art Forum, 16, 03, viewed 23 January 2003, <http://www.msstate.edu/Fineart_Online/Backissues/Vol_16/faf_v16_n03/text/jodi.html>.

Moulthrop, Stuart. (1991) Victory Garden. Cambridge, Eastgate Systems.

Newsgaming. (2003) September 12th. viewed 10 October 2003, <http://newsgaming.com/games/index12.htm>.

Pearce, Celia. (1998) Beyond Shoot Your Friends: A Call to Arms in the Battle against Violence. In: Dodsworth Jr, Clark (Ed.) Digital Illusion: Entertaining the Future with High Technology. New York, ACM Press.

Prensky, Marc. Social Impact Games. viewed 10 October 2003, <http://www.socialimpactgames.com>.

Squire, Kurt & Jenkins, Henry. (2002) The Art of Contested Space. viewed 23 January 2003, <http://web.mit.edu/21fms/www/faculty/henry3/contestedspaces.html>.

Stef & Phil. (2002) New York Defender. viewed 23 January 2003, <http://www.angelfire.com/nb/cdi/games16.htm>.

Thompson, Clive. (2002) Online Video Games Are the Newest Form of Social Comment. 29 August, Slate, viewed 23 January 2003, <http://slate.msn.com/?id=2070197>.

© 2001 - 2004 Game Studies

Copyright for articles published in this journal is retained by the journal, except for the right to republish in printed paper publications, which belongs to the authors, but with first publication rights granted to the journal. By virtue of their appearance in this open access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.