The Agony and the Exidy: A History of Video Game Violence and the Legacy of Death Race

by Carly A. KocurekAbstract:

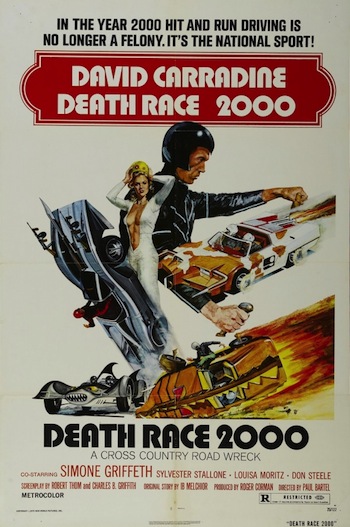

In 1976, Exidy's Death Race triggered the United States’ first video gaming moral panic. Public outrage not only fueled sales of the game and made Exidy a household name, but established a pattern by which controversial games receive a high levels of press attention, which in turn drives these games' marketplace success. Exidy released Death Race in the midst of changing cinema production codes and distribution regulations that led to the emergence of films featuring unprecedented displays of violence and sexuality. The game is based on one of these films, Death Race 2000, in which competitors in the Annual Transcontinental Road Race mow down pedestrians for points. Although the filmmakers did not authorize the use of their concepts for the game, the game relies directly on the film's narrative. The chase-and-crash game invites players to strike stick-figure "gremlins" with on-screen cars. Context, including the game's cabinet graphics and the film, contributed to moral guardians' perception that the game was celebrating violence. However, Death Race was distributed in a market filled with numerous other violent games. This suggests the game triggered outrage not only because it was violent, but because it depicted violence which questioned the state's monopoly on legitimized violence and did not follow culturally accepted narratives of violence, such as military or police violence, or the western. Public disapproval of Death Race did not squelch distribution, instead driving sales and vaulting Exidy into the national spotlight. Discourse surrounding Death Race forged a strong tie between video gaming and violence in the public imagination, ensuring the development of similarly violent games. This bond has persisted and led to the development of several similar games, including the controversial Grand Theft Auto franchise, which is the progeny of Death Race in both narrative theme and reception.

Keywords: arcade, videogames, history, moral panic, Exidy, violence

Introduction

In July 2011, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association that video games qualify for the same free speech protections that cover other forms of expression; in their ruling, the justices cite a rich history of prior free speech cases1. These cases include landmark decisions which helped deregulate film screenings and cable television broadcasting, and the court's 2010 decision in United States v. Stevens, 559 U.S. 130 S.Ct. 1577 (2010), which "held that new categories of unprotected speech may not be added to the list by a legislature that concludes certain speech is too harmful to be tolerated"2 (Brown v. EMA, 2011). In the majority opinion in Brown v. EMA, the justices note that, "this country has no tradition of specially restricting children's access to depictions of violence," and hold that "California's claim that ꞌinteractiveꞌ video games present special problems, in that the player participates in the violent action on screen and determines its outcome, is unpersuasive" (Brown v. EMA, 2011).

In the United States, debate over the alleged social ills of video gaming has a lengthy and colorful history.

The fetishization of novel media technologies in industrial and public narratives of video gaming help obscure the medium's cultural history. Debates about video game violence seem perpetually new as the specific technologies used to depict violent acts are endlessly retooled with an eye toward interactivity, immersion, and realism. But, the history of moral panics about video game violence stretches almost as long as the history of the industry itself, beginning with Exidy's Death Race in 1976. The game, based on the 1975 film Death Race 2000, made waves far beyond the confines of the coin-op industry and helped establish the Exidy brand nationally. For moral guardians suspicious of or hostile to the budding culture of video gaming, Death Race became the signature example of video games' depravity and corrupting influence.

To explore the lasting impact and implications of Exidy's Death Race, I will begin with an overview of Death Race 2000, placing it in its historical and cultural context. I then provide a history of Exidy's Death Race game and the public response to the game's perceived violence. By placing the game in the historical context of changing cinema production codes, I show how it served as a flash point in broader discussions about what constituted appropriate subject matter for popular media. Additionally, I suggest that, because Death Race existed in a games market already replete with depictions of militarized violence, the game triggered outrage not merely because it was violent, but because it depicted violence which clearly questioned the state's monopoly on legitimized violence and did not exist in other culturally accepted narratives of violence, such as the cinematic western. I outline how the reaction to Death Race did little to squelch the game's distribution, and instead had the contrary effect of driving sales and vaulting Exidy into the national spotlight. Further, I argue that the discourse surrounding Death Race helped forge a strong tie between video gaming and violence in the public imagination, effectively ensuring the development of similarly violent games. This bond has persisted to the present, leading to the development of several similar games, most famously the controversial Grand Theft Auto franchise – the progeny of Death Race in both theme and reception.

Before proceeding, I would like to provide a working definition of violence guiding its use in this paper; I do not wish to argue for or against any particular definitions or uses of the term, but simply to clarify what that term will mean in the confines of this work. Violence can be a rather elastic concept, referring to everything from profanity to axe murder. For the purposes of this chapter, I will define "violence" as causing deliberate physical harm to people, animals, or property. This follows the standard centering of discourse over "violent" media on displays of physical acts such as simulated killing, fighting, or – in the case of Death Race – running over figures. The "violent" media considered in this essay have been key texts in this longstanding debate about propriety and morality.

Of Silver Screens and Death Screams

In the film Death Race 2000, set in the year 2000, the United States has collapsed due to a financial crisis and a military takeover. In the wake of the upheavals, the United States has been reconceived as the United Provinces. The Bipartisan Party has subsumed all political parties, creating a one-party system. The Bipartisan Party also serves as the nation's religious leadership, as church and state have unified. The nation's figurehead is the charismatic Mr. President (Sandy McCallum), who alternates between soothing assurances and fiery incitements like the most skilled cult leader. The citizens of the United Provinces remain placated through the spectacle of a slew of ultraviolent sports. The most popular of these bloody public contests is the Annual Transcontinental Road Race. The race, considered an important symbol of the nation's values (which include "the American tradition of no holds barred"), is a cross-country road race in which motorists run down pedestrians for points. Elderly victims are worth a whopping 70 points, while women are worth 10 more points than men in all age brackets, teenagers are worth 40 points, and so on. For efficiency's sake, the race coincides with the ever-popular Euthanasia Day, so motorists can contribute to the public good by mowing down pensioners whose wheelchairs and hospital beds have been rolled out for the occasion.

Figure 1: Poster for Death Race 2000.

The film is intended as dystopic social satire. Despite a sense of general malaise, the citizens of the United Provinces are not universally content. A resistance group, called "the Army of the Resistance," led by Thomas Paine's descendant Thomasina Paine (Harriet Medin) works to assassinate the racer Frankenstein (David Carradine) and replace him with a double. The resistance believes Frankenstein is a personal friend of Mr. President and the leader will end the race in exchange for Frankenstein’s safe return. Annie (Simone Griffeth) is Thomasina's granddaughter and Frankenstein's navigator; she plans to lure Frankenstein into an ambush. She learns, however, that Frankenstein wants to win the race in part so he can blow up Mr. President with a grenade disguised in his prosthetic hand. Frankenstein becomes the winner – and only survivor – of the race, but his hand grenade plan is derailed by an injury. Annie dresses in his costume and plans to stab Mr. President, but is shot and wounded by her grandmother in a case of mistaken identity. Mr. President is ultimately mowed down by Frankenstein in his race car. In the film's epilogue, Frankenstein and Annie are married and Frankenstein has become the new President. He overhauls the United Provinces legal system, and includes among his reforms the abolition of the Transcontinental Road Race.

The bloodbath of outrageous deaths and car stunts yields a smorgasbord of cinematic violence. The carsꞌ spiked fronts equip them as killing machines. A construction worker performing road maintenance is gored, and his freshly-minted widow is later interviewed on national television and informed that as the widow of the race's first victim, she has won an apartment in Acapulco and a 50" three-dimensional television. A fan, who has won the opportunity to meet Frankenstein, insists 'scoring isn't killing … it's part of the race." Another racer chases a fisherman down a creek and flattens him. These and other scenes of violence present a deliberate excess.

Critics were divided over whether the film was scathingly funny or simply a crass bloodbath delighting too easily in the same culture of violence it ostensibly critiques. Writing for The New York Times, Lawrence Van Gelder (1975) dismissed the film by suggesting it had failed as satire:

In the end, it [Death Race 2000] reveals itself to have nothing to say beyond the superficial about government or rebellion. And in the absence of such a statement, it becomes what it seems to have mocked – a spectacle glorifying the car as an instrument of violence.

Roger Ebert, writing for the Chicago Sun-Times, awarded the film zero stars, and did not engage with the film much in his review, choosing instead to meditate on his experience seeing an audience full of children watch the movie with glee (Ebert, 1975). Negative critical response to the film was not universal. In The Los Angeles Times, Kevin Thomas (1975) said the film "demonstrates that imagination can overcome the tightest budget." In addition to praising several actorsꞌ performances, he dismissed criticisms of the film's violence saying, "there's much slaughter in ꞌDeath Race 2000,ꞌ but it's presented so swiftly that the film avoids an unduly hypocritical exploitation of that which it means to condemn."

As in the case of many other cult films, critical distaste did not mark the film as a failure. The outrage evident in reviews like Ebert's and Van Gelder's may have served the contrary purpose of driving audience members to the theaters. Exploitation films had – and still have – an audience of devotees who came to them for bare breasts, violence, and scandalous subject matter (Greene, 2003). The movie was a low-budget piece produced by Roger "King of the B-Movies" Corman. Intended to compete with Rollerball, Death Race 2000 performed well, despite having a budget of only $300,000 (Death Race 2000, 1975). Rental revenues totaling $4.8 million fleshed out the filmꞌs box office profits (Ramao, 2003). The same visual orgy of visceral pleasure that delighted many audience members – some of them quite young -- also outraged moral guardians. As Ebert had noted, the film's R rating did not seem to serve as an adequate barrier between the film and the minds of impressionable youngsters3. Despite the film's modest budget and relatively low box office take, it gained a high profile. Reviews in The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, and the Chicago Sun-Times would have reached a large audience.

In addition to fitting within the historical production category of the exploitation film, Death Race 2000 was released simultaneous to an emergent mainstream cinema more prone to displays of violence and overt sexuality. The U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Memoirs v. Massachusetts in 1966, holding that only materials which could be shown to be both "patently offensive" and "utterly without redeeming social value" did not qualify for First Amendment protections. Two years later, the Hayes Code which had restricted cinema production was replaced by the more permissive voluntary Motion Picture Association of America ratings system. In 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court further extended free speech protections in the decision inMiller v. California, permitting obscene materials as long as they were not distributed to minors or to third parties who had not specifically requested these materials. Looser definitions of obscenity led to a proliferation of violent and risqué films in the United States which would not have passed muster under the preceding regulatory standards. Many like Death Race 2000 or even pornographic films like The Devil in Miss Jones (1973) and Deep Throat (1972) gained cult status which sustained their popularity long enough to make them early video rental favorites later that decade.

The relaxing of governmental and industry regulation of film production meant that films like Death Race 2000 could make some claim to cultural legitimacy and were less likely to face outright banning or suppression. Death Race 2000 may have been a low-budget film, but it had a cast of legitimate actors and a production team with enough clout to garner reviews in major papers. The film was a recognizable name and became a cult hit; film listings for Dallas Morning News indicate that theaters in the area were still screening the film with some regularity in 1978, three years after the film's release, with screenings also occurring in 1979 and 1980, often alongside domestic and international horror/action films like Death Rage, Master of the Flying Guillotine, Schoolgirls in Chains, and Chain Gang Women4. Despite Ebert's concerns about the film reaching a young audience, Death Race 2000 fit in well at drive-ins and late-night screenings catering to devotees of oddball cinema, an outlet where it persisted long enough to become a recognizable brand. And where, at least in the case of the drive-in, viewing context may have added to the effect of watching cars mowing down hapless pedestrians.

The cultural context into which Exidy launched Death Race as an arcade upright in 1976 was shaped not only by the film that inspired the game, but also by a broader debate about media and amusement regulation and youth access in the United States. Coin-op amusements had long been regarded with suspicion in the U.S., and moral reformers had successfully influenced the regulation of film and comic books among other media. The Comics Code, in particular, resulted from efforts to curb the spread of materials deemed inappropriate for young readers. While U.S. video game manufacturers may have early thought of their machines as bar amusements intended for adult consumers, the appeal to and popularity among younger players fueled moral guardians anxieties around video games. Arcade video games had no ratings system to indicate the intended or appropriate audience for particular machines. Even the MPAA film ratings system was quite young at the time, and as Roger Ebert notes in his review of Death Race 2000, that rating system was not entirely effective at keeping younger viewers away from adult materials. In the absence of a clear definition of appropriate audience for Death Race, moral guardians seem to have assumed that the game’s accessibility to children meant it was intended for them.

Marketing Controversy

In 1976 when Exidy selected the name Death Race for a new driving chase-and-crash game, the game company was attempting to cash in on the film's infamy, a strategy which guaranteed the game a certain level of name recognition and invited controversy. Exidy was not alone in attempting this strategy; a year earlier, Atari had released Shark Jaws as an unlicensed tie-in to the highly successful Jaws (1975) film. Like Shark Jaws, Death Race was not licensed, and the film's copyright holders were not consulted, but consumers readily made the connection between the game's pixilated graphics and the film's orgy of automotive violence. This connection precipitated what became video gaming's first significant moral panic. Atari's Gotcha (1973) had caused a bit of a kerfuffle several years earlier owing to its pair of round pink rubber controllers which looked a bit too much like breasts for the comfort of some critics – especially since the controllers had to be squeezed to operate the game. Employees at Atari reportedly referred to Gotcha as "the boob game." Overall, Gotcha fared poorly in the market even after the pink globes were replaced with standard joysticks (Gotcha, n.d.). The mild controversy over Gotcha could not hold a candle to the deluge of media attention and moral outrage that met Death Race.

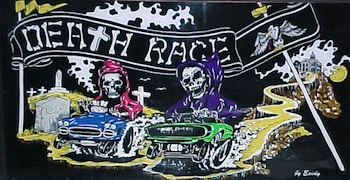

Figure 2: Death Race marquee (Source: The International Arcade Museum/The Killer List of Video Games)

Death Race followed on the success of Exidy's Destruction Derby (1975), which had sold well. However, while Destruction Derby was one of at least three car crash games on the market, Death Race was presented as something innovative and exciting5. The first of a series of advertisements for the game to appear in trade journal RePlay boasted of the game's unique design and linked it to a variety of historical car and motorcycle-loving bad guys:

Exidy introduces:

th Race 98

It's indescribable. So different, it's in a class by itself.

Death Race 98 is what the player wants it to be:

mobsters in the 30's

commandos in the 40's

dragsters in the 50's

hells angels in the 60's

street racers in the 70's

The first game to require the player to "get involved" in whatever way he wants.

If you liked Destruction Derby …

Double your profits with DEATH RACE 98 –

It's a chase and crash game with a twist6.

The advertisement featured the marquee picture from the game cabinet complete with muscle-car racing ghouls, and the first line describing the game is punctuated with tiny skull-and-crossbones graphics. The statement that the player will have to "ꞌget involvedꞌ in whatever way he wants" suggests a male audience, but more importantly, it suggests the game will provide an immersive, engrossing environment.

The advertisements in RePlay do not target players directly, but in fact target the route operators who purchase and place coin-op machines in public places. The goal is not to convince individuals to play the game, but instead to convince operators that the game will hook a general audience and prove a moneymaking investment. Exidy considered the cabinet graphics to be a major selling point for Death Race, and so the flashy marquee graphic dominates the advertisement. Individual coin-op machines represented significant investments for route operators, and the move toward video games increased the investment required for each machine. Operators could be hard to sell on new games, especially when they could instead purchase and place more copies of games already successful on their routes. The reference to Destruction Derby links the game to Exidy's past success while the text as a whole suggests, none too subtly, that the game is different enough to hook a larger audience of players, whether they're interested in '50s dragsters, '30s mobsters, or '70s street racers, while ensuring that it will be as good an investment as Destruction Derby7.

Figure 3: Death Race cabinet (Source: Rob Boudon)

The second advertisement for Death Race to appear in RePlay ran the next month in the April 1976 issue. Perhaps in acknowledgement of a feature covering the game's release in the issue, the ad features simple typography with a photographic image of the game cabinet (Death Race from Exidy, 1976). Exidy's marketing and sales manager Linda Robertson suggests the graphics were at least as important to the game as the gameplay: "the artwork alone on this game . . . showing the skeletons, gremlins and graveyard . . . is certain to invite immediate player interest. The play of the game is so much fun they'l come back again and again" (Death Race from Exidy, 1976). More obviously appealing directly to operators, the ad includes promises of high profits and excellent technical service:

STEP ASIDE!

HERE COMES THE LEADER OF THE PACK!

DEATH RACE by EXIDY

A CHASE AND CRASH GAME

WITH A TWIST

This text is followed by a bulleted listing of the game's technical specifications, such as setting options and screen size. The advertisement ends by stressing the game's profit potential, claiming gamers will want to replay the game:

DOUBLE YOUR PROFITS WITH DEATH RACE

IT's INDESCRIBABLE!

SO DIFFERENT, IT's IN A CLASS BY ITSELF!

CAPTURES YOUR EYE WHEN YOU SEE IT

CAPTURES YOUR FANCY WHEN YOU PLAY IT

AND BRINGS "EM BACK FOR MORE (STEP ASIDE!, 1976).

The advertisement appeals to profit motives at several points, promising double profits, repeat customers, and readily available service to save operators from profit-sucking downtime. In a third ad, elements of the cabinet graphics make up most of the ad, with a photographic image of a cabinet shown as well. The ad shows the Exidy name several times, but the main text reads simply, "New! Death Race. It's fascinating! It's fun chasing monsters" (New! Death Race from Exidy, 1976.) Although controversy did not begin brewing until the spring buying season had ended and operators began placing machines, the ad makes explicit that players are chasing "monsters," not to be confused with people.

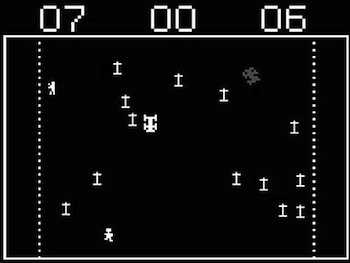

Figure 4: Death Race screen capture (Source: IGN)

The gameplay of Death Race is similar to more recent games like Carmageddon (1997) and Grand Theft Auto (1997), which allow players to drive over human or humanoid figures in the game world, and which I will discuss in more depth later. Death Race can be played as a one- or two-player game. The operator could adjust the game to give players between 80 and 135 seconds of playtime per purchased game with games costing 25 cents for a single-player game and 50 cents for a two-player game. Each player operates one of two on-screen cars using a steering wheel, pedal, and a shift lever. The objective of play is to hit as many "gremlins" as possible. Each struck gremlin leaves behind a cross-shaped tombstone which becomes an in-game obstacle for the duration of the game; because of this, each possible iteration of the game would have a somewhat unique playing field depending on how many gremlins were struck and where they were struck.

Gremlins can only be struck when they are in the central "legitimate playing field" of the game. In two-player mode, players are competing against one another for the most kills. A player therefore might choose to deliberately crash into the other player to prevent him or her from striking a gremlin (Exidy, n.d.). The game ranks players depending on the number of points they scored. These rankings – skeleton chaser for 1-3 points, bone cracker for 4-10 points, gremlin hunter for 11-20, and expert driver for scores greater than 21 – further the horror-inspired theme of the game (Death Race from Exidy, 1976).

As opposed to the lush cabinet graphics, the on-screen graphics in Death Race are rudimentary. The "gremlins" are stick figures and the cars are simple blocks with wheels. The "violence" of the game then is much dependent on context. However, to perceive pixilated black-and-white graphics as simple as those in Death Race as violent gore is not fantasy. Context contributed to the certainty reformers felt when criticizing the game. The film from which the game took its name had already become a notable example of violent cinema, familiar even to those who had not seen the thing. Despite Death Race 2000'slimited circulation reviews like Roger Ebert's primed the public to assign outrage to any media affiliated with the film. Because the game's title deliberately associated it with the movie, the story of the film became the narrative world of the game. No matter how many times Exidy executives claimed the figures were "gremlins" or how many advertisements stressed that the object of the game was to chase "monsters," severing the association with the film's pedestrian targets was an impossible feat. Within a few months of its release, Death Race was attracting national scandal and earning coverage in major news outlets, including The New York Times and 60 Minutes. Interviews with Exidy executives made clear that the company found the controversy a combination annoyance and good source of publicity.

Violent Narratives at Play

One peculiar aspect of the controversy worth drawing attention to is the larger context of other coin-op video games available in 1976. While the lively used market accessible to route operators certainly expanded the number of games available for purchase at any given time, I would like to focus here on the new machines sold through distributors. Even a cursory glance at listings of new machines makes clear that Death Race was not the only violent game on the market. Atari's offerings in 1976 included five games which could be categorized as violent: the rather self explanatory Cops 'N' Robbers; the chase and crash Crash 'N' Score; the wild west-themed gunfighting game OUTLAW; Jetfighter, which featured simulated jet dogfighting; and TANK 8, an 8-player tank warfare game. Chicago Coin, of course, had their chase and crash, Demolition Derby, available. Electra's offerings included AVENGER, a scrolling shooter game in which the player piloted a fighter plane. Digital offered a jet fighting game with the rather self-explanatory name AIR COMBAT. Meadows was manufacturing Bombs Away, in which players piloted bomber planes and sunk ships, and Fun Games had a seek-and-destroy aircraft game named BiPlane.

Death Race was not an isolated incident of violent gaming; it existed in a field littered with competitor games with equally violent premises. Despite the overt violence in these games, they did not attract the scrutiny that greeted Death Race's entry into public consciousness. However, the public response indicates that the game's monster chasing was considered more horrifying than the human-on-human violence featured prominently in many other games at the same time. Several factors may have contributed to the specificity of the response to Death Race. At a basic level, the game's flashy cabinet graphics set it apart from other games in the arcade. The game's on-screen graphics, rudimentary as they look in retrospect, were unusual in featuring humanoid figures as general targets. Other games, like OUTLAW and TANK 8, that featured human-on-human violence fit within broadly accepted cultural and historical narratives of violence. Military games, in particular, would not have disrupted the accepted governmental monopoly on violence. War is commonly justified, or even glorified, as a defensive practice at the very least, as well as a means of preserving certain ideals or even proving national vigor. The vigilante justice of the Wild West is often romanticized as a critical step in the "civilizing" of the region. In summary, the violent fantasies of the other games listed here would have fit within accepted violent realities. Further, the violence of many of these games may have been overlooked because it was not considered violence against human actors; although tanks, airplanes, and submarines are presumably operated by people, these human actors never appear on screen and are rarely, if ever, alluded to. Atari founder Nolan Bushnell implied as much:

We were really unhappy with that game [Death Race]. We [Atari] had an internal rule that we wouldn't allow violence against people. You could blow up a tank or you could blow up a flying saucer, but you couldn't blow up people. We felt that that was not good form, and we adhered to that all during my tenure. (Kent, 2002).

Of course, Atari’s OUTLAW directly violates this purported policy. However, regardless of where the line was drawn about human actors, the violent realities depicted by Atari and other companies were like games in being governed by specific rules of engagement. The quickdraw contest starts reliably at ten paces, limited warfare of any kind predicates on agreed-upon rules of engagement. In this way, as James Campbell (2008) suggests, once it has been reduced to a historical narrative draped in nostalgia, even the proverbial hell of war can operate ludologically, which is to say, as a game. Video games based on war and gun duels, then, may not have offended because they are based on realities already experienced as games at some level. Death Race did not fit within these violent realities, instead presenting a fictional landscape that most closely echoed the reality of the pedestrian hit-and-run accident. The reality presented is too unregimented, too suggestive of violent chaos. The objection, then, may not be the violence per se, but the lawlessness of that violence, and the suggestion it carries of violence outside the accepted social order.

Mediating the Mayhem

By 1976 there were several dozen video games on the market and route operators were clamoring to place the most successful machines in prime locations. When RePlay reported on the top performing games in October 1975, just three years after video games became the hot new thing in the coin-op industry, video games already made up a significant percentage of route collections. The estimated weekly gross for video games was $43.00 per machine, outpacing every other type of machine except pool tables, which inched ahead with a weekly gross of $44.00 per machine. In bars and taverns, video games were tied with shuffle alleys as the third most popular type of game after pool tables and pinball machines. However, in less explicitly adult venues, they fared even better: in restaurants and other food serving businesses, they ranked second after pinball games (Replay Route Analysis, 1975). Efforts to curtail the spread of video games, through zoning, code restrictions, and other local measures speak to a more general discomfort with the games and an assumption that the games were reaching and potentially damaging young players. The violent actions depicted in Death Race became a lightning rod for a broader uneasiness regarding games, particularly with regards to youth access. Several of the factors outlined above likely contributed to the reaction to the game, and different factors may have helped to mobilize different people.

Once identified as a controversy, Death Race attracted high-profile media attention. Even coverage that appeared as news, rather than editorial, helped perpetuate the controversy by legitimizing concerns and raising awareness of the issue. An article in The New York Times in December of 1976 indicated the game had attracted the attention not only of local authorities, but of the National Safety Council. In the article, the author refers to the game's stick figure targets as "symbolic pedestrians" and quotes extensively from the manager of the NSC's research department, behavioral psychologist Gerald Driessen. Driessen notes that nearly 9,000 pedestrians were killed in the past year, presumably in driving accidents, and argues that video game violence is categorically different from television violence:

On TV, violence is passive . . . In this game a player takes the first step to creating violence. The player is no longer just a spectator. He's an actor in the process . . . I"m sure most people playing this game do not jump in their car and drive at pedestrians . . . But one in a thousand? One in a million? And I shudder to think what will come next if this is encouraged. It'll be pretty gory. (Blumenthal, 1976).

In the article, Exidy's response, delivered by way of general manager Phil Brooks, is that the game is not actually depicting graphic violence: "If we wanted to have cars running over pedestrians, we could have done it to curl your hair." He goes on to that the sound that accompanies the gremlinsꞌ destruction is a "beep," not a scream or shriek: "We could have had screeching of tires, moans and screams for eight bucks extra . . . But . . . we wouldn't build a game like that. We're human beings, too." At the time of the New York Times article, Exidy had already built and sold 900 Death Race units, and Brooks explicitly said the coverage of the game, no matter how negative, had driven sales (Blumenthal, 1976).

A New York Times article published in August of 1977 again summarizes the game, and quotes from Driessen. However, here, the tone is different. Titled "Postscript: Controversial "Death Race" Game Reaches 'Finish' Line," the article presents itself as a close to a controversy that had made headlines for the better part of a year. Exidy had ceased manufacture of Death Race earlier in 1977, and while the remaining machines might be problematic, the game seems less of a clear and present danger. The article does recount a scene from Westwood Electronic Amusement Center in Los Angeles, where the reporter saw a young girl score 6 hits on the machine while under the supervision of her father, who encouraged her by saying "You sure were chasing them." The article closes by quoting a 13-year-old fan of the game who responds to the suggestion the game may make him violent: "that's stupid, and besides I don't even know how to drive" (Harvey, 1977). The issue is presented as somehow resolved, no longer a serious threat, even though children are still playing the offending game.

When Exidy first began manufacturing Death Race, the company had not considered it as one of their more important designs. According to Paul Jacobs, who served as Executive Vice President for Exidy in the 1980s, the game was "originally viewed by the company as nothing more than an intermediary piece with a limited run" (Brainard, 1983). The game had been performing well, but had not attracted much attention and did not seem slated to become a hit when an Associated Press reporter based in Seattle wrote a story raising questions about how child-appropriate the game was. The story captured public interest and triggered coverage in a variety of other outlets. In defending the game, Exidy rarely addresses the gameꞌs intended audience; instead, the company seeks to minimize the gamesꞌ violence and stresses that the publicity has been beneficial. Jacobs repeated the belief that the publicity had been good for the company's image, had driven sales of the game, and had raised the image of the video game industry:

We're not at all ashamed to talk about "Death Race" … The net result was that we handled the whole thing very well and the publicity was good for the industry …. As for the game, the media attention made it more popular than we ever imagined it would be … We built over ten times the number of machines in the original release. (Brainard, 1983).

As media outlets cast attention, even negative attention, on the Exidy brand and interviewed Exidy executives, they raised the profile of the company among operators choosing games for purchase. The infamy of the Death Race game not only drove sales of the original game, but prodded Exidy to release a sequel to the game, Super Death Chase in 19778. In a RePlay article giving a 10-year retrospective on Exidy's early success, Kathy Brainard (1983) says that Death Race received "more media attention than any other game prior to ꞌPac-Man.ꞌ" Brainard may have been overstating, given the heaps of press received by PONG, but her hyperbole makes an important point about Death Race's infamy and what that infamy afforded. In addition to helping establish Exidy as an industrial player to watch, Death Race helped drive Exidy's sales and helped secure the company's financial position.

Lingering Impact

Death Race not only helped establish the Exidy brand, the game established a pattern for future moral panics regarding video games. Death Race may have been the first of these, but controversy greeted a variety of subsequent games, many of which, like Death Race enjoyed a spike in sales because of the publicity. While for the remainder of the ꞌ70s and the early part of the ꞌ80s the public debate on video games moved from concerns over specific text to worries about the arcades themselves, the issue of violence remained simmering in the background, boiling over at the release of certain games or in the face of particularly horrifying acts of violence perpetuated by youth. Two particularly infamous game franchises, Carmageddon (1997) and Grand Theft Auto (1997) draw inspiration directly from Death Race 2000 and the legacy of the Death Race game.

When, the British company Stainless Games released Carmageddon, in 1997, the public response bore striking similarities to the response to Death Race. Carmageddon is a racing game with incorporated vehicular combat in which players gain extra time by damaging other vehicles, collecting bonuses, or striking pedestrians. Like Death Race, the game featured vehicular violence that existed well outside established and accepted narratives of violence. In the United States, the Entertainment Software Ratings Board gave the game a rating of "M," the board's second-most restrictive rating, intended to indicate that the game is suitable only for players who are at least 17 years of age. The game was censored in other countries, including the United Kingdom, where censors insisted pedestrian victimsꞌ blood be changed from red to green to give credence to the claim that the victims were not human (Poole, 2000). As in the case of Death Race, the controversy did not stifle sales and instead drove them. According to lead programmer and company co-founder Patrick Buckland: "We weren't known, the brand wasn't known … The game had to stand on its own two feet, and it might not have done that without the violence – though it did get fantastic reviews" (The making of . . ., 2008).

Positive reviews or not, Carmageddon would not have drawn much attention outside publications intended for gamers had it not been for the surrounding controversy. As a small studio, Stainless Games did not have the resources to mount large-scale advertising or publicity campaigns. As Buckland points out, the game may not have sold well had it not been for the violence. Even with its positive reviews, Carmageddon would not have reached an audience outside the population of dedicated game consumers if it had not received attention from mainstream media outlets, which it did only as a result of the game’s controversial content.

Another twist on the gleefully violent car game is Rockstar Games" Grand Theft Auto franchise, which originally appeared in the same year as the first Carmageddon. In the Grand Theft Auto games, the protagonist is an aspiring criminal who raises up the organized crime ladder by completing assigned tasks; the game features nudity, gun violence, drunk driving, drug dealing, and vehicular violence including pedestrian hit-and-run collisions. High-profile cases in which the games were blamed for acts of violence have fueled controversy. In 2003, William Buckner, age 16, and his stepbrother Joshua Buckner, 14 killed one person and seriously wounded another by shooting at their cars. The boys told authorities they had decided shoot at vehicles with rifles because of the game Grand Theft Auto III. In another suit plaintiffs blamed Grand Theft Auto for the shooting deaths of two police officers and a dispatcher at the hands of a 17-year-old. The franchise has proven so controversial that the Guinness Book of World Records (2009) named it the most controversial video game series in history. Again, like Death Race and Carmageddon, GTA focuses on violence outside the established social order. This is not the violence of war or the Wild West or even the police procedural, which are often framed as necessary to maintaining order, but instead a violence that is reckless and at times seemingly joyful.

The increasing sophistication of graphics, sound, and other design components of titles like Carmageddon and GTA helps animate debate regarding these games. The novel media technologies employed contribute to the sense that the games pose a new, unique threat and helps sever them from earlier games in public discourse. While Death Race and the controversy that surrounded it may in retrospect appear quaint given contemporary media context, they occupy a critical role in the development of public perceptions of video gaming and public debates about the appropriate and intended audiences for video games. As evidenced not only by Death Race, but by these two more recent franchises, controversy does not still the production of violent video games; in fact, public discourse about violence only helps reiterate that video games are violent, not only by making the connection between video games and violence over and over again, but also by raising the profile of particularly violent games.

Sales figures further suggest that controversy drives sales. In 2010 the ESRB reported that only 5% of the games rated by the board received an M, or "Mature" rating, but five of the ten top-selling games that year were rated M (Narcisse, 2011). All five of these M-rated top sellers – Call of Duty: Black Ops, Halo: Reach, Red Dead Redemption, Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2, and Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood – received their M-rating largely for violence. That several of these games depict militarized violence, as in the case of the Call of Duty titles, or Wild West violence, as in the case of Red Dead Redemption, is worth noting as these games continue to adhere to acceptable discussions of violence and are by degrees less controversial than the transgressive violence depicted in Death Race, Carmageddon, and the GTA franchise. Regardless, however, these games prominently feature violence and are frequently cited as examples of violent games while garnering spots on top seller lists. Violent games become the most popular in part because they draw the most attention, which further normalizes them. This is to say there is much more discussion about a game like Death Race or Grand Theft Auto or Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2, and that this discussion, in reaching people who would not necessarily be playing games, renders this violence an integral part of video games as a medium. In the interim from 1976 to the present, violent games have become so common, if not at the level of manufacture, then at least at the level of play and of public discourse, that it is impossible to separate violent video games from the broader category of video games more generally. The case of Death Race makes provocative suggestions about the way that moral panics drive the production and distribution of violent games and help normalize violent content across the medium. In the history of video game violence specifically and the history of moral panics about media culture and youth more generally, the role public controversy plays in shaping industrial production and distribution of certain types of games is a point worthy of further research and consideration.

Endnotes

1 Brown refers to California Governor Jerry Brown; the case was previously known as Schwarzenegger v. EMA, in reference to then-governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. The EMA is the Electronic Merchants Association, and is the international trade association of the home entertainment industry, primarily video gaming.

2 The video game industry took a note from the film industry"s Motion Picture Association of America ratings system with the establishment of the Entertainment Software Review Board (ESRB) in 1994 as a self regulatory measure in an effort to placate demands for external regulation, and today, nearly all games sold through retail outlets are rated.

3 Note that Motion Picture Association of America ratings are industry standards and do not carry the force of law. While theaters may choose to enforce age restrictions for certain films, there are no legal penalties for refusing or failing to do so.

4 Advertisements indicate screenings of the film in January 1978, February 1978, March 1978 (when the film was showing in at least four venues), as well as November 1979 and February 1980. A sampling of these listings:

"Movie Guide," The Dallas Morning News. 9 January 1978. Page 19. Accessed 24 September 2010, NewsBank/Readex, Database: America"s Historical Newspapers.

"Movie Guide," The Dallas Morning News. 14 February 1978. Page 28. Accessed 24 September 2010. NewsBank/Readex, Database: America"s Historical Newspapers.

"Movie Guide," The Dallas Morning News, 13 March 1978. Page 16. Accessed 24 September 2010. NewsBank/Readex, Database: America"s Historical Newspapers.

"Movie Guide," The Dallas Morning News, 15 November 1979. Page 93. Accessed 24 September 2010. NewsBank/Readex, Database: America"s Historical Newspapers.

"Movie Guide," The Dallas Morning News, 21 February 1980. Page 82. Accessed 24 September 2010. NewsBank/Readex, Database; America"s Historical Newspapers.

5 Chase and crash games available in 1976 would have included Demolition Derby (Chicago Coin, 1975), Destruction Derby (Exidy, 1975), and Crash "N" Score (Atari, 1975)

6 I am considering Death Race 98 and Death Race as the same game. The company appears to use the names somewhat interchangeably, with the only difference between the two being the inclusion of the "98" on the cabinet graphics.

7 Exidy actually continued to advertise Destruction Derby in the same issue of RePlay to include the first advertisement for Death Race 98. The market for coin-op machines was such that particularly games would continue to be strong sellers for several years, and companies would usually continue to offer them as long as there was a reliable market for new machines.

8 Although Death Race 98 is sometimes referenced as a sequel to Death Race,based on advertisements, Death Race and Death Race 98 appear to be the same game. Even the cabinet graphics are identical save for the insertion of the "98" on the banner displaying the name of the game. Death Race 98 is first advertised in RePlay in March 1976 and Death Race is first advertised in the April 1976 issue. Given the proximity of these ads to each other and to other coverage of the game Death Race, with no mention of Death Race 98, they appear to have been part of the same publicity campaign. The evidence offered by industry coverage from the time period suggests, as I believe, that they were treated interchangeably by the manufacture.

References

Atari. (1973). Gotcha. USA: Atari.

Atari. (1976). Cops 'N' Robbers. USA: Atari.

Atari. (1976). Crash 'N' Score. USA: Atari.

Atari. (1976). OUTLAW: Jetfighter. USA: Atari.

Atari. (1976). TANK 8. USA: Atari.

Bishop, W. (Producer), and Frost, L. (Director). (1971). Chain gang women. [Motion picture]. United States: Flaming Productions Ltd.

Blumenthal, R. (1976). "Death Race" game gains favor, but not with the safety council. New York Times. Retrieved September 22, 2010. Retrieved from http://www.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/

BradyGames. (2009). Guinness World Records 2009 Gamer's Edition. New York: Time Home Entertainment, Inc.

Brainard, K. (1983). Exidy: Ten years of EXcellence in DYnamics," RePlay, 9(10), 93-99;100-102.

Brown v. EMA, 564 U.S. (2011).

Bungie. (2010.) Halo: Reach. USA: Bungie.

Campbell, J. (2008). "Just less than total war: Simulating World War II as ludic nostalgia." In S. Whalen and L. N. Taylo, eds. Playing the Past: History and Nostalgia in Video Games pp. 183-200. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

Chicago Coin. (1976). Demolition derby. USA: Chicago Coin.

Corman, R. (Producer and Director). (1966). The wild angels. [Motion picture]. United States: American International Pictures.

Corman, R. (Producer and Director). (1976). The St. Valentine's Day massacre. [Motion picture]. United States: Los Altos Productions.

Corman, R. (Producer), and Bartel, P. (Director). (1975). Death race 2000. [Motion picture]. United States: New World Pictures.

Damiano, G. (Producer and Director). (1972). Deep throat. [Motion picture]. United States: Gerard Damiano Film Productions.

Damiano, G. (Producer and Director). (1973). The devil in Miss Jones. [Motion picture]. United States: Pierre Productions, Inc.

Death race 2000 (1975). (n.d.) Internet Movie Database. Retrieved on 21 September 2010. Retrieved from http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0072856/

"Death Race from Exidy," (1976). RePlay. 2(4), 22.

D'Emilio, J., and Freedman, E.B. (1997). Intimate matters. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Digital Games Incorporated. (1976). AIR COMBAT. United States: Digital Games Incorporated.

Ebert, R. (1975). Death Race 2000. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved April 2010. Retrieved from http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19750427/REVIEWS/808259998

Electra. (1976). AVENGER. United States: Electra.

Exidy. (1975). Destruction derby. USA: Exidy.

Exidy. (1976). Death race. USA: Exidy.

Exidy. (1977). Super death chase. USA: Exidy.

Exidy, ed. (n.d.) Death Race Exidy service manual. Retrieved from http://www.arcade-museum.com/manuals-videogames/D/DeathRace.pdf

Exidy introduces: Death Race 98. (1976). RePlay, 2(3), 29.

Fun Games Inc. (1976). BiPlane. USA: Fun Games Inc.

Gamemaker sued over highway shootings. (2003). SFGate.com. Retrieved September 30, 2010. Retrieved from http://articles.sfgate.com/2003-10-23/business/17515225_1_sony-computer-entertainment-america-punitive-damages-state-custody

Gotcha. (n.d.) The killer list of video games. Retrieved 27 April 2011. Retrieved from http://www.arcade-museum.com/game_detail.php?game_id=7985

Greene, R. (Producer and Director). (2003). Schlock! The secret history of American movies [Motion picture]. United States: Pathfinder Home Entertainment.

Harvey, S. (1977). Postscript: Controversial "Death Race" game reaches "finish" line. The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 22, 2010. Retrieved from http://www.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/

Homer, R., and Lenzi, U. (Producers), and Margheriti, A. (Director). (1976). Death rage. [Motion picture]. Italy: Giovine.

Infinity Ward. (2009). Call of duty: Modern warfare 2. USA: Infinity Ward.

Jewinson, N. (Producer and Director.) (1975). Rollerball. [Motion picture]. United States: Algonquin.

Jones, D. (Producer and Director). (1973). Schoolgirls in chains. [Motion picture]. United States: Mirror Releasing.

Kent, S. L. (2002). The ultimate history of video games: The story behind the craze that touched our lives and changed the world. New York: Three Rivers Press.

"The Making of … Carmageddon," (2008). Edge Magazine. Retrieved September 30, 2010. Retrieved from http://www.next-gen.biz/features/the-making-of%E2%80%A6-carmageddon?page=0%2C0

Meadows. (1976). Bombs away. USA: Meadows.

Memoirs v. Massachusetts, 383 U.S. 413 (1966)

Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15 (1973)

Narcisse, E. (2011). "Games rated 'mature' are made less, bought more," Time Techland. Retrieved August 22, 2011. Retrieved from http://techland.time.com/2011/03/21/games-rated-mature-are-made-less-bought-more/

New! Death Race by Exidy. (1976). RePlay, 2(5), 9.

Poole, S. (2002). Trigger happy. New York: Arcade Publishing.

Thomas, K. (1975). Movie review: Barbarism in big brother era. Review of Death Race 2000. The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 22, 2010. Retrieved from http://www.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/

Ramao, T. (2003). Engines of transformation: An analytical history of the 1970s car chase cycle," New Review of Film and Television Studies, 1.1, p. 45.

Replay Route Analysis. (1975) RePlay, 1(1), 38.

Rockstar Games. (1997). Grand Theft Auto. USA: Rockstar Games.

Rockstar Games. (2001). Grand Theft Auto III. USA: Rockstar Games.

Rockstar Games. (2010). Red dead redemption. USA: Rockstar Games.

Stainless Games. (1997). Carmageddon. USA: Stainless Games.

STEP ASIDE! (1976). RePlay, 2(4), 15.

"Suit: video game sparked police shootings." (2005). ABC News. Retrieved September 30, 2010. Retrieved from http://web.archive.org/web/20050307095559/http://abcnews.go.com/US/wireStory?id=502424

Treyarch. (2010). Call of duty: Black ops. USA: Treyarch.

Ubisoft. (2010). Assassin's creed: Brotherhood. Montreal: Ubisoft.

Van Gelder, L. (1975). The acreen: "Death Race 2000" is short on satire. The New York Times. Retrieved September 20, 2010. Retrieved from http://www.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/ (accessed September 20, 2010).

Wong, C.H. (Producer), and Wang, Y. (Director). (1976). Master of the flying guillotine. [Motion picture]. Hong Kong: First Film Organisation Ltd.