“There Has To Be More To It”: Diegetic Violence and the Uncertainty of President Kennedy’s Death

by Carrie AndersenAbstract

Few moments in American history are as contested and controversial as President John F. Kennedy’s death in 1963, a story still mired in uncertainty and disinformation. Consequently, the assassination has been explored through literature, film, and television—and, more recently, videogames—in ways that have generated countless alternate historical narratives, unsettling the possibility of determining what actually happened to the President half a century ago. In this article, I consider whether videogames that have engaged with Kennedy’s death have similarly opened up this historical narrative to reinterpretation. I provide narratological and ludological readings of two first-person shooter (FPS) games that invite players to experience President Kennedy’s assassination—JFK:Reloaded (released in 2004) and Call of Duty: Black Ops (released in 2010)—as well as other players’ accounts and interpretations of their gaming experiences gleaned from online forum posts, focusing on the way violence is constructed within both games. Although scholars have linked diegetic violence, clear narrative progression, and the oversimplification of historical events in FPS games, I illustrate that the specific type of diegetic violence these games afford thwarts comprehensibility of the historical narrative of Kennedy’s death by limiting how players experience and control violent acts. Due to that emergent historical uncertainty, the production of historical knowledge through Reloaded and Black Ops does not solely emerge from games and gameplay, but from extratextual dialogue and debate that extends beyond the games themselves.

Keywords

History, violence, first-person shooter, Call of Duty, historical memory, truth, guns

In a recent New York Times editorial, celebrated documentarian Errol Morris (2011) pontificated about the open-endedness of historical narratives surrounding President John F. Kennedy’s assassination: “Why, after 48 years, are people still quarrelling and quibbling about this case? What is it about this case that has not led to a solution, but to the endless proliferation of possible solutions?” Half a century later, the story of Kennedy’s death remains contested. The unknowability of this significant historical moment has led to myriad media representations across genres that feature Kennedy’s death, from light-hearted parodies of the assassination on the 1990s sitcom Seinfeld to Oliver Stone’s controversial JFK (1991), a film that many critics argued promoted conspiracy theories and lies at the expense of historical truth.

These representations construct what Alison Landsberg (2004) describes as “prosthetic memories,” or visions of the past that are facilitated by the repetition of artificially created historical moments through media. Prosthetic memories arise from a process in which an individual does not simply encounter an historical narrative, but “takes on a more personal, deeply felt memory of a past event through which he or she did not live” (Landsberg 2004, p. 2). Even if histories’ constructions emerge from mass-mediated representations of past events, these prosthetic memories can feel as real as if we had been eyewitnesses and can thus interpolate our historical knowledge and visions of politics.

Although Kennedy’s death has predominantly been featured in film and on television since the mid-1960s, his assassination has more recently been incorporated into videogames, a medium newly concerned with historical representation. Game Studies scholars have recently attended to videogames’ representations and simulations of history, often exploring how videogames afford different ways of engaging with the past than other media provide. Andrew B.R. Elliott and Matthew Wilhelm Kapell (2013), for example, emphasize the contingency of history as presented in videogames, a medium that rejects the inevitability of the historical past in favour of more open-ended narrative possibilities. Kevin Schut (2007), Ryan Lizardi (2014), Marcus Schulzke (2013), and William Uricchio (2005) similarly offer that historical games can expand the possibilities of historical narrative beyond what is prescribed in orthodox stories of the past.

With their emphasis on opening history to reimagination and reinterpretation, videogames are an especially well-suited medium for contending with the assassination of President Kennedy, a deeply fraught and ambiguous narrative that, as Don DeLillo (1983) muses, has become “a story about our uncertain grip on the world” (p. 28). In this article, I explore two videogames in which the player enacts or witnesses this historical moment. The first, JFK: Reloaded, was developed by Traffic Games in 2004. Its designers intended for Reloaded to prove the Warren Commission’s assessment of Kennedy’s assassination to be unequivocally true, in that players would be able to reenact the shots the Commission argued Oswald took from the sixth floor of the Texas Book Depository. The second, Call of Duty: Black Ops, was developed by Treyarch and released in 2010 by Activision and presents a fictional, alternative history of Kennedy’s assassination, complete with state conspiracy and CIA-led brain-washing. These games are both first-person shooter (FPS) games, and both foreground Kennedy’s death to a greater extent than other videogames, perhaps being the only games to explore the assassination narrative at all. Given the uncertainty that continues to plague the history of Kennedy’s death, I question whether these games clarify or amplify that uncertainty, and what the consequences that clarification or obfuscation are for players’ engagement with history and with the ways we understand the production of historical knowledge.

Within the FPS genre, scholars have often linked diegetic violence, the clear progression of a game’s narrative, and a reductionist vision of historical and political events as comprehensible (see Campbell 2008, Gish 2010, Tanine 2010, Hitchens, Patrickson, and Young 2014). In this article, however, narratological and ludological readings of Reloaded and Black Ops alongside other players’ accounts of gameplay reveal that the specific type of diegetic violence these games afford ultimately thwarts the production of certainty in the historical narrative of Kennedy’s death. Rather than rendering a historical tale simple and digestible, both Reloaded and Black Ops muddy the past in the ways they enable players to experience and enact violence—an outcome that distances players from historical certainty. I centre my analysis on the ideological meaning of diegetic gunfire. Guns have driven many of the most significant events in the course of human history, from wars to assassinations. The words of writer Tom McCarthy (2007) from the fiction novel Remainder are instructive here:

Each time a gun is fired the whole history of engineering comes into play. Of politics, too: war, assassination, revolution, terror. Guns aren’t just history’s props and agents: they’re history itself, spinning alternate futures in their chamber, hurling the present from their barrel, casting aside the empty shells of the past (p. 190).

By this account, violence is history, and enacting violence means propelling an historical narrative forward. The same is true of many video games and especially of FPS games, according to scholars like Harrison Gish (2010), whose reading of Call of Duty World War II games emphasizes how the games “foreground singular acts of violence as the sole catalyst of military victory and the impetus for historical progression” (p. 173).

In both these games, however, the limitations on the ways the player can commit a violent act hamper the construction of a knowable historical narrative. Although violence may propel history forward, a player may still harbour uncertainty about the events that comprise that history. Reloaded—a game in which players act as Lee Harvey Oswald in reenacting President Kennedy’s assassination—requires extreme precision in shooting at the president. Rather than verifying the single-shooter theory of Kennedy’s death, as the game’s creators hoped, the difficulty of the prescribed task actually inspires player subversion and the consequential creation of alternate histories of Kennedy’s assassination that deviate from orthodox historical narrative. By contrast, Black Ops, a first-person shooter game, privileges more open expressions of violence to advance the narrative, but the game’s blend of unplayable narrative cut scenes and playable missions means some central moments of narrative progression, like Kennedy’s death, are not moments that the player can control. Thus his death leaves many players with questions as to what truly transpired both in the Black Ops story and in the real world narrative of Kennedy’s death.

These two games exemplify the open-ended nature of history that videogames can facilitate, even as games within the FPS genre typically close off or simplify historical narrative. Video games like Reloaded or Black Ops can expand how we understand history. Patrick Jagoda (2013) notes, for example, that the independently developed videogame Braid complicates history by imbuing historical practice with conceptual play, enabling players to contend with historical contradiction and dissonance in a way other media do not afford. Moreover, Schut (2007) suggests that videogames tend to present history as “less about an account of time and more about an experience of space and people in the past” (p. 230). Rather than focusing on history as a process of play, discord, and spatial engagement, however, I close by discussing how the production of historical knowledge through these two games does not solely emerge from games and gameplay, but from extratextual dialogue beyond the games themselves.

Documenting and Creating the Past: A Summary of Reloaded and Black Ops

Before beginning a deeper analysis of these games, let me first provide an overview of each game’s central conceit. Reloaded requires players to reenact Kennedy’s assassination. The task is simple: the player must replicate the same three shots that Lee Harvey Oswald took from the sixth floor of the Texas State Book Depository in Dallas, according to the Warren Report (see Figure 1). Those shots must resemble Oswald’s in time (they must be fired at the same moment), space (they must strike the victims, Kennedy and Governor John B. Connally Jr., at the precise angles that enable the same ricochets and trajectories), and sequence (one cannot kill Kennedy with the first shot, for example). The game’s straightforward objective belies the many variables that make exact replication of Oswald’s shots difficult. The more deviations from these variables, the lower the score. If the player completes the mission with total accuracy, he or she receives 1000 out of 1000 points.

Figure 1. Screenshot from JFK: Reloaded. The player acts as Lee Harvey Oswald in delivering a series of gunshots at the President.

The motivations behind creating Reloaded in the first place are twofold. In addition to a pedagogical motivation to educate young gamers in the history of Kennedy’s assassination, Reloaded’s creator Kirk Ewing noted that a central goal of creating Reloaded was to validate the findings of the Warren Commission through simulation: a fully successful round of play could show that Oswald’s gunshots were plausible (Vågnes 2011). Although translating a traumatic moment in American history into a game yielded criticism, inviting players to simulate the assassination also provided historical knowledge that might otherwise have been less accessible, like viewing the kill from several angles (Galloway, McAlpine and Harris 2007).

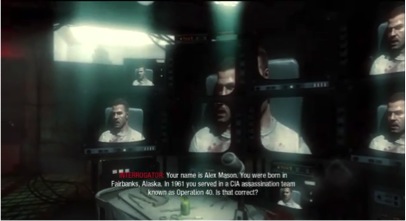

Contrary to Reloaded, Black Ops does not offer pure historical reenactment, instead providing an alternate history of Kennedy’s assassination. A player’s introduction to the single-player campaign is through an unplayable narrative cut scene, where he or she first meets the main character, operative Alex Mason, in a decrepit interrogation room in 1968 (see Figure 2). Mason is strapped to a chair against his will, surrounded by television screens playing old newscasts and flashes of numbers. A low, gravelly voice from an unseen source prods Mason to discuss specifics of CIA missions in his past. The player pieces together the Black Ops narrative through a series of unplayable narrative cut scenes interspersed with playable flashbacks.

Figure 2. Screenshot from Call of Duty: Black Ops. Mason is interrogated by unknown captors.

A failed covert mission in Cuba leaves Mason in the hands of Soviet General Nikita Dragovich and held for two years in prison, where he meets Viktor Reznov, a former Soviet soldier turned ally. During a cut scene, Reznov reveals information about Mason’s captors, including Dragovich and a Nazi scientist who has created a deadly nerve gas. After escaping, Mason meets President Kennedy in an unplayable cut scene in which Mason is charged with a new mission: assassinate Dragovich. Hereafter, the player operates through the point of view of several characters, Mason included, on several missions designed both to seize the Nazi’s nerve agent and to kill Dragovich.

After a series of combat missions, the player is shown in a cut scene that Soviet sleeper agents have been planted in America to release the nerve gas and kill President Kennedy upon receiving a transmission of a series of numbers over the airwaves. The player also learns that the Soviets implanted those numbers in Mason’s mind, indicating that he has been brainwashed to kill Kennedy. Meanwhile, the player controls Mason on a mission to kill the Nazi scientist, accompanied by Reznov. After the mission, the player returns to an unplayable interrogation scene where Mason claims that Reznov killed the scientist, but the interrogators reveal that Mason was behind the kill. This cut scene throws Mason’s memories and the game’s narrative into disarray: Mason learns that his interrogators are actually his fellow CIA operatives and that Reznov died long before the Nazi’s death. Moreover, before Reznov died, he manipulated Mason’s brainwashing to trigger the assassinations of Dragovich and the Nazi rather than to kill President Kennedy. At this point, Mason does not know which of his experiences actually transpired, and which were mental fabrications emerging from mental trauma and brainwashing.

The final playable mission takes the player and some other American operatives to a ship off the coast of Cuba, which holds both Dragovich and the numbers broadcast station that will cause the sleeper agents to release the nerve gas. The U.S. Navy destroys the ship, but Mason kills Dragovich, yelling, “You’re trying to fuck with my mind! You tried to make me kill my own president!” Dragovich grins and replies, “Tried?” Mason then chokes Dragovich to death with the player’s rapid button pushing, the player’s final playable act in the campaign. Upon their escape, Mason’s fellow operative expresses relief that both the ship and Dragovich are history: “It’s over. We won.” Mason is not so sure, merely replying, “For now.” Of course, the story is not over. An unplayable cut scene shows a woman reading a series of numbers into a microphone, and the player watches archival footage featuring Kennedy as he descends from an airplane. Kennedy climbs into a car next to his wife, and they drive into Dallas. The film rewinds, slows down, and zooms into a man in the crowd at the airport: Alex Mason. The implication is that Dragovich successfully brainwashed Mason to assassinate President Kennedy.

Exploring the Kennedy Assassination Narrative

In attending to the meaning of diegetic violence and the construction of prosthetic memories of Kennedy’s death, I build my analysis upon two data sources: my own close reading of the game’s narratological and ludological content, and the reactions of several players who engaged with these games, gleaned from user comments on YouTube videos of gameplay and from online forum posts. The games’ structures and narratives contribute to debates that emerge in online spaces among players regarding both the gameplay and the veracity of the Warren Commission’s assassination narrative that Oswald was Kennedy’s lone shooter in the real world.

I make no claims, however, that either my reading or the players’ perspectives constitute preferred readings of either game, or that these readings are representative of the majority of gamers encountering these narratives. These games afford a variety of readings about how players might encounter and interpret the prosthetic memories of Kennedy’s assassination, and how these readings constitute a form of historical knowledge. In this case, I focus on how diegetic representation opens up historical narratives to uncertainty and instability.

This article questions whether these games’ constructions of Kennedy’s assassination, as much as they differ in narrative content, gameplay, and authorial intent, provided additional answers about his death. “What can we understand about these historical recreations through their simulation?” asks Tracy Fullerton (2008) of Reloaded, and these questions are also instructive in considering the residual effects of Black Ops. “Can we understand the reasons behind an assassination? The emotions of the assassin? The nuances of the political content? Or only its basic forensic data?” (p. 229-230). This article poses an additional question: what are the limits on historical knowledge gleaned from videogames? My analysis suggests that limiting diegetic violence in both Reloaded and Black Ops renders the historical narrative of Kennedy’s death murkier than it already is, creating historical uncertainty and consequentially opening a space for historical debate. I focus here on three key limitations of violence in both Reloaded and Black Ops : difficult gameplay, a limited temporal scope, and the juxtaposition between interactive and non-interactive gaming elements.

The Difficulty of Constrained Violence

Typically, FPS games reward great magnitudes of violence: the more a player shoots, the more enemies die, and the more the game progresses (Schut 2007, Hitchens, Patrickson, and Young 2014). As a result, accuracy is often secondary to simply killing as many enemies as possible in an indiscriminate spray of bullets. Yet Reloaded deviates from this tradition in requiring that players fire only three precise shots. Simply killing Kennedy is not enough to win the game: the shots must be fired within particular parameters. These shots are especially difficult to reenact not only because of the precision required to score well—for example, a mere fraction of a second off of Oswald’s shots will lower the player’s score—but because the game seeks to approximate both the Warren Commission’s account of Kennedy’s death and the physics of the real world. The player must aim slightly ahead of the targets to ensure that the bullet will meet the target at the right moment. Moreover, due to the effects of gravity, attempting to strike a faraway target means a player must aim higher to account for the miniscule loss of height over time. Even the way the Mannlicher-Carcano rifle fires is imbued with real-world accuracy: because firing each shot requires removing the empty shell case and reloading the gun, for example, he or she must wait before firing again. Success in the game requires complying with these diegetic limitations on violence, but those limitations also make it ostensibly impossible to win [1].

Even Ewing acknowledges the difficulty of Oswald’s task: “We’ve created the game with the belief that Oswald was the only person that fired the shots on that day, although this recreation proves how immensely difficult his task was” (Richardson 2012). The results of the contest confirm the difficulty: the high score was only 782/1000 by a French player with the username of Major_Koenig on Monday, February 21, 2005. No player over the course of the contest could reenact Oswald’s shots with complete accuracy. Rather than validating the Warren Report, then, the contest questioned it.

Playing within these boundaries also reveals the peculiarity of Oswald’s shots, according to the Warren Report. Rather than firing a head-on shot at the Kennedy motorcade as they drive down Houston—an easy kill to make in Reloaded—the player must wait until the cars turn the corner and drive away from the Depository to fire the shot as Oswald did. This is a harder shot to make, since players must follow the car’s horizontal motion with their rifles to kill Kennedy. This difficulty inspires concerns about whether Oswald would have been able to fire the shots the Commission claimed he did. Fullerton (2008) comes to similar conclusions in her experience playing the game:

I am struck by two things: first, how deeply disturbing it is to play [Oswald’s] particular role, and second, how convinced I’ve become after fifteen or twenty attempts that Lee Harvey Oswald could not have made those shots — at least not if this simulation is in any way accurate (p. 228-229).

The official narrative begins to make less sense as players like Fullerton can fully experience the difficulty of Oswald’s supposed shots.

Since the game’s creation, other players have also linked the game’s difficulty and the unfeasibility of the official assassination tale in dialogues online. Although the game website is no longer active, one can access it now through archived snapshots of the page, but the forum section of the site where players would discuss their strategies and experiences is completely defunct. Noting this dearth of source material, media studies scholar Steve Anderson (2011) looks instead to “machinima video recordings of playthroughs of the game,” many of which can be found on YouTube (p. 136), an approach this article also takes. The few videos that highlight respectable scores include some debates about the veracity of the Warren Report’s conclusions based on the game’s difficulty:

[The game] may be sick, but the game just shows how impossible it must have been for Oswald to do this on his own (Rahhelthethird 2008).

It is impossible to win. Because JFK was shot by three different people. From three different angles. It is also impossible to shoot a bolt action rilfe [sic] accurately at a moving target three times in under 6 seconds. JFK was not killed by Lee Harvey Oswald. He was killed by Operation 40, the same group that committed the Watergate Scandal (fallensk8r2222 2008).

While some users describe the game as proving to them the Warren Commission was right—one user explains, “JFK Reloaded definitely proves to me that it was HIGHLY probable Oswald fired all three shoots [sic] and assassinated the president on his own,” while another notes, “this game convinced me that Kennedy really was shot from the top floor of a book depository” —the game nonetheless did not resolve this uncertain historical narrative for many players largely because it prescribed such strict limitations on the violence players were supposed to enact to engage with that history (cfh0384 2011, thespread 2008).

Temporal Limitations and Alternate Histories

Reloaded further hinders verifying the Warren Commission narrative by limiting the time a player spends in gameplay. Each trial is a rapid experience: from the moment Kennedy’s motorcade becomes visible to the moment a player fires the shots, about forty-five seconds pass. As a result, a player can easily repeat the assassination over and over. The potential for quick repetition partially compensates for the game’s difficulty—a player can quickly try again—but it also creates a gaming experience in which players create and witness a slew of alternate historical outcomes that deviate from orthodox historical narrative. Fullerton (2008) recognizes this accrual of outcomes in which the diegetic narrative repeatedly differs from the event that it is meant to simulate: “…in all of the alternate endings of the event conceived by my play of the game, only once was the president seriously injured. Every other time, the motorcade made it out of range before history could be fulfilled” (p. 229).

In addition to the unintended alternative narratives that Fullerton describes, the short duration of each trial also creates a space for intentional deviations. Referring to online videos of gamers’ rounds of Reloaded, Anderson (2007) notes that “even a cursory survey of these videos reveals a remarkable array of the divergent trajectories of digital historiography” (p. 136). This ability to subvert, of course, is inherent to game design itself, as game designers can merely control what Cindy Poremba (2009) describes as the “design of the conditions of experience, rather than the direct design of experience itself” (p. 7). Players of Reloaded can play through myriad trials in the span of minutes. A player may discover easier methods of killing Kennedy, or a player might discover other modes of exacting violence in this limited timespan that are more destructive, produce more absurd results, and are more entertaining. Although, as Schut (2007) and Sicart (2011) note, the rules and mechanics of a game system limit player choice, playing in a way that rubs against a game’s intended path—in this case, rejecting the objective to assassinate Kennedy according to the strictures of the Warren Report—constitutes what Nick Dyer-Witheford and Greig de Peuter (2009) describe as “counterplay,” a form of dissidence rooted in playing against the strictures of a game system that reifies imperial power.

As such, rather than highlighting the historical accuracy of their trials, players who post videos of their gameplay instead tend to celebrate the power or breadth of their violent acts, subtly challenging the state’s control over the narrative of Kennedy’s death. Many players fire at other members of the motorcade, like Kennedy’s driver or members of the secret service to see what might happen when their violence exceeds the boundaries of what history apparently prescribed. The titles of these YouTube player videos are particularly revealing of players’ desires to play against the grain. Examples include “JFK Reloaded — Crash Bang Wallop!!!!”, “Physics Phun with JFK Reloaded,” “JFK Reloaded lulz,” and “JFK Reloaded Biker Mistakes,” all highlighting gameplay that departs from the prescribed objective to recreate Oswald’s shots. Similarly, many players’ forum posts on the International Skeptics Forum—a site for debating historical narrative and conspiracy theories—do not discuss how to replicate history, nor do they explicitly question the official assassination narrative. Although this forum does contain many debates about Kennedy’s death, Reloaded players who post on the forum often discuss how to kill as many characters as possible:

You get the highest body count if you aim for the driver just after he makes the turn. My ‘best’ was the driver, the other agent in the front seat, all 4 passengers, 2 motorcycle cops and a few bystanders (Retrograde 2007).

True experts know to shoot the limo driver, then shoot the driver in the VP's car, (the third car) and then the driver of the secret service car (directly behind the Presmobile). It’s scripted so the VP's car will always speed up, but if he’s shot it’ll be uncontrolled. So it’ll rocket into the SS car, which sends the agents standing on the running boards flying, which will hit the now accelerating limo, and then the rest of the motorcade panics and speeds up, causing a horrific pile-up that leaves a trail of corpses across the plaza (Rich M 2007).

I played this a little while ago. I remember that you can change the size of the motorcade and how bonkers the drivers are. So, set the Motorcade to max size and make the drivers as crazy as possible. When the cars come around, shoot some of them. Watch the havoc (Coritani 2007).

These players work around the designers’ intentions for this game to create chaos in Dealey Plaza. Whether this mode of play constitutes an expression of sadism or a means of pushing against the parameters of the game system is unclear, but ultimately, recreating Oswald’s shots is no part of some players’ gaming experiences. The new object of the game becomes inciting as much devastation and death in the very limited window of time the game provides. In doing so, these players impede the game’s status as a tool that could validate official narratives of Kennedy’s death and foster greater historical certainty.

Although some players have played Reloaded in order to reenact the historical narrative of Kennedy’s death, the game’s limitations on the violence players can enact, whether making successful gunshots too difficult to enact or whether condensing the time frame in which players can enact violence, clouds prosthetic memories of Kennedy’s assassination. Even as Ewing and the game’s designers intended for the game to put to rest alternative stories of Kennedy’s death, the constraints on diegetic violence opened up possibilities for the proliferation of new stories.

Call of Duty: Black Ops and the Frailty of Memory

Like Reloaded, Black Ops engages with the troubled narrative of Kennedy’s assassination and raises questions about the ways that games can represent historical moments. Black Ops is the only game in the Call of Duty series thus far to centre on the early Cold War era, but analyses of other games in the series reveal how this franchise typically represents history. Gish (2010) argues that representations of World War II in the series challenge “grand narratives of past events” through blending playable levels and cut scenes that provoke diverse player experiences (p. 168). Even so, the games nonetheless reduce the War “to singular acts of violence” and project “a linearity that leaves little room for interpretation” (Gish 2010, p. 172). Evidence of the simplification of historical narratives of war lies in the games’ valorisation of American military heroes and structured spacing that inheres in most videogames: players physically move to propel the narrative forward but are limited in their “tightly regimented” movement through the game space (Gish 2010, p. 172). My reading of Black Ops departs from this assessment. Instead, like Reloaded, Black Ops thwarts the typical construction of diegetic history as simple and knowable through exacting limitations on player violence. Although Black Ops is predominantly a fictional story, the game’s narrative incorporates historical elements of Kennedy’s assassination outside of the game’s fiction, and in doing so, troubles players’ understandings of both the game narrative and of the history beyond it.

Central to the notion of unknowable history in Black Ops is the merger of interactive gameplay and non-interactive narrative cut-scenes. Although, as Clemens Reisner (2013) notes, shooting is essential to progressing through the Black Ops historical narrative, not all spaces are equally navigable, nor can the player fire his or her weapon in any moment of the game. While the player can trudge through the jungle and shoot at Vietcong soldiers, he or she can merely look around the room of the interrogation chamber. While he or she can choke Dragovich to death—a truly grisly use of the controller—he or she can only watch as Defence Secretary Robert MacNamara escorts Mason to meet with President Kennedy. The collage of playable missions with non-playable cinematic cut scenes, what Gish (2010) describes as “layers,” suggests both a limited ability to construct historical meaning and an often passive relationship with diegetic historical narrative. As Daniel Punday (2004) writes, cut-scenes offer narrative continuity and coherence but push “a sense of narrative inevitability” in forestalling alternative paths (p. 83). We see this transpire in Black Ops. In many of the game’s most instructive narrative moments—strategizing with Reznov, meeting with Kennedy—a player can watch a narrative unfold, but he or she cannot refashion that narrative beyond a prescribed path.

Generally, the player rarely has control over his or her character when the narrative drifts towards non-violent activity. Cut-scenes offer a similar experience, as the player witnesses a moment crucial to the narrative without controlling or participating in it. This passivity fosters distance from the narrative: the player can learn the backstory that makes the myriad exchanges of gunfire possible, but the lack of interactivity detaches him or her from those moments.

Players’ accounts of Black Ops reveal frustration with cut scenes that hamper the game’s otherwise quick and action-packed pace. While some players report enjoyment of the cut scenes on the official Call of Duty: Black Ops forum (for example, snoman76 (2010) notes, “I truly enjoyed the cut-scenes as well (felt like a top rated movie) as the gameplay”), the predominant response to the cut scenes is boredom and annoyance, revealed in discussions of the campaign on the online forum Reddit:

Too much scripted things. Scripting is ok but not when it interrupts the game every few minutes” (tpa, 2011).

I don’t like the too-long ‘stories’ in between the action. WAY too long. But the story is pretty good (wheeldog, 2010).

Oh don’t get me wrong, I loved [the cut scenes], but it was kind of annoying when you had to restart the mission…and you just want to get [the cut scene] out of the way (thisloser 2010).

While the game designers consciously paced the game to avoid inciting boredom—Olin describes, “[Black Ops is] not just white-knuckle edge-of-your-seat action the entire way through; you’d feel exhausted and it would get monotonous”—many players would have rather been barraged with intense action sequences (as cited in Arnott, 2010).

Consequently, the fact that Kennedy’s arrival in Dallas and apparent assassination are presented within an unplayable cut scene invites interrogation. The historical moment of Kennedy’s death, rather than something a player can influence, is cordoned off from interaction. The player watches what looks like archival film footage of Kennedy on the Dallas tarmac, swarmed by a crowd admirers before he climbs into his vehicle and drives through the city, before the footage rewinds, taking the player back to the tarmac and zooming in on Mason’s visage in the crowd. The game ends before a shot is fired, but the player is led to believe that Mason was behind Kennedy’s death (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Screenshot from Black Ops. Mason appears in apparent documentary footage of Kennedy’s arrival in Dallas, Texas.

Players must watch Kennedy’s journey to his death in Dallas with no opportunity to change the story. Given Mason’s mental trauma and the inherent uncertainty of the Kennedy assassination narrative, if the player does not fire at Kennedy himself or herself, the player cannot easily know how the assassination transpired. Is Mason actually in the crowd at the airport? Is this simply another figment of his imagination assembled after being brainwashed? Mason’s damaged memories fabricated an intricate tale of Kennedy’s assassination, but the game evokes uncertainty as to which cut scenes and missions are untainted, if any, because of the non-interactivity of this scene.

Because the player does not fire a shot at the president at the game’s close, questions as to how Kennedy was killed plagued players who posted discussion threads on the topic on the Black Ops forums and elsewhere, as seen in these excerpts of a lengthy online debate on Call of Duty’s Black Ops forum:

“Judging from the comments and flashback at the end of the game it is safe to assume that he did… On the other hand I myself agree with you.. I do not think that he did…” (Boondocks_Saint 2011).

“I don’t think he did. The image flashed into his head because he was programmed at Vorkuta to kill Kennedy. However, Reznov interfered and reprogrammed Mason to kill Dragovich, [Nazi scientist] Steiner, and [Dragovich’s second-in-command] Kravchenko instead” (hehedin 2011).

I agree with part of this, but I do believe Mason killed JFK. There is a part toward the end when he confronts the bad guy, and says ‘you tried to make me kill the president!’ and [Dragovich] replies incredulously: ‘what? you have no idea what we’ve done to you’, which I take to mean that he was programmed to kill the president, but at a later date, not in the pentagon [sic] during the storyline (croesius 2011).

It certainly was suggested [that Mason killed Kennedy], but not confirmed. I don't think Mason would have helped him so much if he had, but then did he know? I don't think we will ever know for certain (sweatyclam 2010).

The debate about the Black Ops narrative in these comments reveals that Black Ops indeed stoked uncertainty in players regarding the story’s final outcome, which encouraged a close reading of the game in hopes of discovering the truth. That uncertainty frustrated some players, as this one complains:

dammit they should have just told instead of leaving us with a big question mark (sir n00b alott 2011).

The historical uncertainty that infuses the Black Ops narrative invites players to consider the validity of their memories of Kennedy’s death out of the gaming space: as one player describes, the uncertain Black Ops story dovetails with the way the Kennedy assassination narrative outside of the game is “still full of rumors and myths” (RGC Sparks, 2010). And videogames are not the only media to function in this way. The amateur film shot by Abraham Zapruder of Kennedy’s motorcade in Dallas, for example, has provided both eyewitnesses and those who were not present in Dallas with prosthetic memories of the assassination. Particularly for those who did not bear witness to the assassination, this film stands in for what really happened, and enables the construction of prosthetic memories for non-eyewitnesses. The Zapruder film is popularly deemed an authentic vision of a past still murky after fifty years of analysis. Consequently, drawing from the aesthetics of Zapruder’s film, Black Ops promotes the authenticity of the diegetic moment of Kennedy’s assassination through framing the scene as part of a film extracted from archival footage, a practice afforded by the growing sophistication of digital technology to blend forms of representation (Fogu 2009). A player hears the click of the filmstrip as the footage plays; filmstrip material borders the images (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Screenshot from Black Ops. President Kennedy and his wife Jackie arrive in Dallas.

Because no other cut scene is framed as authentic archival footage, a player is led to believe that this moment actually transpired in Mason’s world; that this diegetic portrayal of Kennedy is a simple, truthful representation of history. Jaimie Baron (2010) finds the same to be true of Call of Duty: World at War, where that the presence of archival documentary footage means that a game’s history is “coded as predetermined and inevitable, as having a single direction, a single narrative, and a single meaning,” forestalling the construction of alternate narratives and limiting the game’s narrative to that which is represented in that cut-scene (p. 308). Beyond narrowing the game’s historical narrative, however, the presentation of this diegetic footage as an archival documentary film also suggests that this event happened outside of the game as well. Black Ops is not alone among video games in blurring fiction and nonfiction in representations of the past through documentary-based cut-scenes, nor is this practice unique to videogames themselves. Media studies scholar Janet Staiger (1996) notes that, in documentary television and film, documentary footage is often mixed with reconstructed or staged scenes, in which audiences may incorrectly see the staged footage “as an authentic ‘trace’ of the real” (p. 44). And Tanine (2010) and Salvati and Bullinger (2013) describe how World War II shooter games present documentary newsreel footage of the war within gameplay to suggest a game’s historical authenticity. The incorporation of purported archival footage in Black Ops suggests both that this history is closed off from reinterpretation and that this vision of Kennedy’s death is not strictly limited to the fictional diegetic world. Instead, this narrative is constructed as reality through its aesthetic portrayal as authentic documentary footage.

Some players were indeed swayed by the injection of this pseudo-documentary scene in Black Ops, as they wonder if the actual footage and photographs connect with what they saw in the game:

waoh [sic] wait. if I look up that pic [of Kennedy in Dallas]. will there be a guy that looks like mason [sic] (Kitty_Hips 2011).

wait wat [sic] the hell.O.O!....how the heck did mason get inna [sic] real video of JFK?... (MrAngel1398 2011).

This footage leaves some players asking questions about the Kennedy assassination narrative in real life, with many players concluding that Mason was a real person who killed Kennedy. Online forum contributions reveal that Black Ops, for some players, indeed blurs the boundaries between fictional narrative and the history of Kennedy’s assassination outside of the game:

I think Alex Mason was a REAL person in REAL life.. And that some of Black Ops its-self referes [sic] to his life. But I’m not sure who actually killed JFK (IOwnAtZombies123456 2012).

Guys the person in real life who killed JFK is called alex mason [sic] (Holy Powerade 2011).

I think at the end it was implied that Mason was the second shooter on the grassy knoll... People need to read up on their conspiracy theories... (M0byFish 2011).

But some players do believe that Alex Mason was involved with the assassintion [sic] (if he was a real person) because Mason mumbles something about Lee Harvey Oswald being comprise [sic] (stevegili 2011).

Other players suggest that the game reveals broader conspiracies about the assassination narrative outside of the game:

The truth is to [sic] dangerous to know and a cover up by the US government. I believe Mason was real and this cutscene is dropping clues about our corrupted government. And last JOHN F. KENNEDY was not assassinated by Lee Harvey Oswald if you study the pictures and video of that tragic day you’ll see that he has a bullet wound on the Right top of his skull which proves that the bullet entered threw [sic] the front not the back which caused the back of his head and brain to explode (OBEY DGAF 2011).

Relatively few players insist that Oswald acted alone—one notes, “Kennedy didn’t died [sic] by mason he died by Oswald a sniper killed him” (Supreme Murder66 2011)—and few indicate their trust that the Warren Report’s single shooter theory was true. Overall, however, the plurality of these accounts reveals both the continued uncertainty surrounding Kennedy’s death and the ability for even a fictional videogame narrative to generate and strengthen the uncertainty surrounding a real world moment in history.

The questions players ask after completing the campaign about the veracity of the historical narrative presented in Black Ops suggests they question both the validity of the narrative within the game as well as the Warren Report’s narrative outside of the game—uncertainty that might have been mitigated had players had the opportunity to exact violence against Kennedy within the game, rather than to more passively watch the preamble to his death. The limits on player violence within the game through unplayable narrative cut-scenes, particularly in the moment of Kennedy’s death, meant that many players were ultimately unable to conclusively understand the game’s story of the Kennedy assassination. And, similar to Reloaded, the uncertainty evoked in playing Black Ops extended from gameplay into players’ understanding of history in the real world.

Conclusion

Against interpretations of diegetic violence as a source of historical simplification, I have shown here how the narrative style, difficulty of gameplay, and the character of violence within videogames is central to determining how real world historical narratives can be destabilized through video game representation, generating uncertain prosthetic memories. This destabilization can occur even when a game is intended to concretize and crystallize orthodox historical narratives, like Reloaded was intended to do, or when a game belongs to a genre and series that typically simplifies historical narratives, like Black Ops. In both cases, limiting diegetic violence constrained historical certainty, displayed both through my reading of these games as well as other players’ reported experiences. Ultimately, my analysis raises questions as to how Game Studies scholars might consider diegetic violence with greater subtlety. I have demonstrated how limitations in gameplay, instead of rigidifying historical narratives, instead open up historical narrative to reinterpretation. Consequently, scholars might not only attend to how violent acts can drive narratives forward, but also how the specific formal constraints upon violence can produce ideological effects, including prosthetic memories that rub against orthodox narratives.

I close here by raising some questions as to the consequences of the open-ended diegetic histories that Reloaded and Black Ops proffer, particularly as they clearly extend beyond the boundaries of both games. The way that alternative histories and counterfactual histories—histories that explore the potential consequences of historical events occurring differently than they did—can open up history to agency and free will is not, of course, limited to video games. Historian Simon T. Kaye (2010), for example, catalogues the history of the speculative and counterfactual in history and literature to illustrate a progressive opening of rigid narratives of the past to human agency which democratized power over narrative construction to “the increasingly enfranchised masses” (p. 47). Games can also afford players agency in allowing them to play through histories that extend beyond the boundaries of orthodox historical narratives. Uricchio (2005) notes that although historical video games often still project simple, linear histories, such games can “offer a new means of reflecting upon the past, working through its possibilities, its alternatives, its ‘might-have-beens,’” lauding the possibilities of the medium to provide new ways to imagine the past (p. 336). Lizardi (2014) offers a similar approach to digital history in his analysis of Bioshock, suggesting that the gameplay “involves players on an agentive, interactive level with the questioning and destabilization of accepted historical events.” And Schut (2007) notes that, in games, “the player always has the ability to redo history” (229). For these scholars, players have the opportunity to create their own story that may rub against generally accepted historical narrative.

Certainly some players do create alternatives to the Warren Commission’s claim that Oswald acted alone, whether imagining a second shooter in another location far from the Texas State Book Depository or buying into the story of a brainwashed sleeper agent as proffered in Black Ops. These moments of reimagination indeed reflect Uricchio’s (2005) argument that video games “shift in determination from the author to the reader,” opening history to interactivity and reformation (p. 335). In other cases, however, players remain mired in uncertainty. In online comments about Reloaded, for example, many players state that the game showed them that Oswald could not have been the only killer, but fail to provide an alternative story of Kennedy’s death that extends beyond killing him in increasingly grotesque methods. Similarly, in online comments about Black Ops, players often expressed confusion with the historical narrative that the game suggested, but did not present alternative narratives. The final outcome of the open-ended history of both games may not be the democratic construction of a new narrative as the aforementioned scholars hope for, but the construction of historical truth as inaccessible.

I do not mean to suggest that the rigidity of unquestioned master narratives of history is preferable to a vision of history as unknowable. But these games raise questions as to how digital games can afford new forms of historical knowledge, particularly when an historical narrative centres upon a contested historical moment like Kennedy’s assassination. Rather than creating a slew of alternative histories that hew closer to the as-yet-known truth, for some players, these games simply highlight the indeterminacy and unknowability of history itself.

But rather than leaving their players immersed in nihilism, these games gesture towards a reimagination of history. History, these games suggest, is not simply a series of events to be learned about through a game narrative. Rather, the open-endedness of the Reloaded and Black Ops narratives figures history as the outcome of a series of extradiegetic dialogues emerging from playing through a game imbued with indeterminancy. These games present historical events as uncertain and thus as open to debate, discussion, and social engagement, as revealed through the hundreds of posts players made in online spaces to ascertain what “really happened” both in these games and in the still ambiguous Kennedy assassination narrative. As such, the case of Black Ops and Reloaded illustrates how scholars might look beyond the text of a digital game into online spaces to explore the production of historical knowledge. Although the “truth” of Kennedy’s death may never be uncovered, the ongoing process of historical excavation that videogames encourage may nonetheless foster a new way to engage with the past.

Appendix: User Comments

Boondocks_Saint (2011, January 20). Sooo did mason kill the pres. or not? [Msg 3]. Message posted to https://community.callofduty.com/message/104445372.

Cfh0384 (2008, October 10). JFK Reloaded — 697/1000 (with replays from multiple angles). Message posted to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rKV7MLnJt54&lc=liHMbf98L5XH4us2cv730LJl0d7aOpcHzvHAnOmaeMQ.

Coritani (2007, February 26). Retrograde (2007, February 26). JFK: Reloaded [Msg 9]. Message posted to http://www.internationalskeptics.com/forums/showthread.php?t=75699.

Croesius (2011, January 20). Sooo did mason kill the pres. or not? [Msg 9]. Message posted to https://community.callofduty.com/message/104445372.

Fallensk8r2222 (2008, October 10). JFK Reloaded — 697/1000 (with replays from multiple angles). Message posted to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rKV7MLnJt54&lc=liHMbf98L5WVQ3YxlL81kd49Hb-XZJyQgxwJlWoQt7Q.

Great Pretender (2007, March 7). JFK reloaded. Message posted to http://www.fun-motion.com/forums/showthread.php?t=89.

Hehedin (2011, January 20). Sooo did mason kill the pres. or not? [Msg 5]. Message posted to https://community.callofduty.com/message/104445372.

Holy Powerade (2011, February 17). Kennedy and Mason theory on Black Ops. Message posted to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=quMPtDd-dTo&lc=6JqBYR6UYf-qy4_3BZrwR7IltXKgsHQ45B7RNy1w5PI.

IOwnAtZombies123456 (2012, February 14). Sooo did mason kill the pres. or not? [Msg 22]. Message posted to https://community.callofduty.com/message/104445372.

Kitty_Hips (2011, February 24). Call of Duty Black Ops - Mason Kill Kennedy (Ending) (HD). Message posted to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MfRy-6LEGU4&lc=tL4VJJvxG5yN4fMdu_JW8jy-BayUeSowC7TjZ_nLWh8.

M0byFish (2011, January 20). Sooo did mason kill the pres. or not? [Msg 15]. Message posted to https://community.callofduty.com/message/104445372.

OBEY DGAF (2011, February 24). Call of Duty Black Ops — Alex Mason Kill Kennedy (Ending) (HD). Message posted to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MfRy-6LEGU4&lc=z12kdhvywqaic3ard04cef0ilr2agt4btmg0k.

Rahhelthethird (2008, October 10). JFK Reloaded — 697/1000 (with replays from multiple angles). Message posted to https://www.youtube.com/all_comments?v=rKV7MLnJt54&lc=liHMbf98L5XRAgaeVBnn1GCgIyjyLE5AyHGxcRMHnb0.

Retrograde (2007, February 26). JFK: Reloaded [Msg 6]. Message posted to http://www.internationalskeptics.com/forums/showthread.php?t=75699.

RGC Sparks (2010, November 20). JFK and Mason. *SPOILERS* [Msg 4]. Message posted to https://community.callofduty.com/message/103905948.

Rich M (2007, February 26). JFK: Reloaded [Msg 7] Message posted to http://www.internationalskeptics.com/forums/showthread.php?t=75699.

Sir n00b alottt (2010, January 20). Sooo did mason kill the pres. or not? [Msg 1]. Message posted to https://community.callofduty.com/message/104445372.

Snoman76 (2010, November 19). Great Job on The Campaign [Msg 6]. Message posted to https://community.callofduty.com/message/103890052.

Stevegili (2011, February 24). Call of Duty Black Ops — Mason Kill Kennedy (Ending) (HD). Message posted to https://www.youtube.com/all_comments?v=MfRy-6LEGU4&lc=tL4VJJvxG5zm_PqwhIv1iOrhAeQZSNddTlQwuAiQDSc.

Supreme Murder66 (2011, February 24). Call of Duty Black Ops - Mason Kill Kennedy (Ending) (HD). Message posted to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MfRy-6LEGU4&lc=z13kwlsqjkqbhzcmr23wg5eytnicvbczk04.

Sweatyclam (2010, November 20). JFK and Mason. *SPOILERS* [msg 7]. Message posted to https://community.callofduty.com/message/103905948.

Thespread (2008, October 10). JFK Reloaded — 697/1000 (with replays from multiple angles). Message posted to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rKV7MLnJt54&lc=liHMbf98L5Ua5XLVBf7CKXbBxwgkaSb73H8_Nxf9S4M.

Thisloser (2010, November 19). Just finished the single player campaign.. [Msg 21]. Message posted to https://www.reddit.com/r/codbo/comments/e90p7/just_finished_the_single_player_campaign?sort=new.

Tpa (2011, February 16). So I am the only one that didn’t like the campaign? [Msg 1]. Message posted to https://www.reddit.com/r/codbo/comments/fmjc7/so_i_am_the_only_one_that_didnt_like_the_campaign.

Wheeldog (2010, November 19). Just finished the single player campaign.. [Msg 16]. Message posted to https://www.reddit.com/r/codbo/comments/e90p7/just_finished_the_single_player_campaign?sort=new.

References

Anderson, S. F. (2011). Technologies of History: Visual Media and the Eccentricity of the Past. Hanover: Dartmouth College Press.

Arnott, J. (2010). Call of Duty: Black Ops — Josh Olin interview. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/gamesblog/2010/sep/20/call-of-duty-black-ops-interview.

Baron, J. (2010). Digital Historicism: Archival Footage, Digital Interface, and Historiographic Effects in Call of Duty: World at War. Eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture, 4(2), 303-314.

Campbell, J. (2008). Just Less Than Total War: Simulating World War as Ludic Nostalgia. In Z. Whalen and L. Taylor (Eds.), Playing the Past: History and Nostalgia in Videogames (183-200). Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

Elliott, A.B.R. and Kapell, M.W. (2013). Introduction: To Build a Past That Will “Stand the Test of Time”—Discovering Historical Facts, Assembling Historical Narratives. In A.B.R. Elliott and M.W. Kappell (Eds.), Playing with the Past: Digital Games and the Simulation of History (1-29). New York: Bloomsbury.

Fogu, C. (2009). Digitalizing Historical Consciousness. History and Theory, 47, 103-121.

Fullerton, T. (2008). Documentary Games: Putting the Player in the Path of History. In Z. Whalen and L. Taylor (Eds.), Playing the Past: History and Nostalgia in Videogames, 215-238. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

Galloway, D., McAlpine, K.B., and Harris, P. (2007). From Michael Moore to JFK Reloaded: Towards a Working Model of Interactive Documentary. Journal of Media Practice, (8)3, 325-339.

Gish, H. (2010). Playing the Second World War: Call of Duty and the Telling of History. Eludamos. Journal for Computer Game Culture, 4(2), 167-180.

Hitchens, M., Patrickson, B. and Young, S. (2014). Reality and Terror, the First-Person Shooter in Current Day Settings. Games and Culture, 9(1), 3-29.

Huntemann, N.B. (2010). Playing with Fear: Catharsis and Resistance in Military-Themed Videogames. In N.B. Huntemann and M.T. Payne (Eds.), Joystick Soldiers: The Politics of Play in Military Videogames (232-236). New York, NY: Routledge.

Jagoda, P. (2013). Fabulously Procedural: Braid, Historical Processing, and the Videogame Sensorium. American Literature, 85(4), 745-779.

JFK Reloaded | Competition Results,” Traffic Games, April 3, 2005, accessed January 19, 2012, http://web.archive.org/web/20050403042055/http://www.jfkreloaded.com/competition/.

Kaye, S. (2010). Challenging Certainty: The Utility and History of Counterfactualism. History and Theory, 49(1), 38-57.

Landsberg, A. (2004). Prosthetic Memory: The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Lizardi, R. (2014). Bioshock: Complex and Alternate Histories. Game Studies, 14(1).

McCarthy, T. (2007). Remainder. London, UK: Vintage.

Molina, B. (2011). Call of Duty: Black Ops ’ Sales Hit 25 Million. USA Today. Retrieved April 13, 2015, http://content.usatoday.com/communities/gamehunters/post/2011/08/call-of-duty-black-ops-sales-hit-25-million/1#T5LsPrNYtcl.

Morris, E. (2011). The Umbrella Man. New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/22/opinion/the-umbrella-man.html.

Poremba, C. (2009). Frames and Simulated Documents: Indexicality in Documentary Videogames. Loading…, 3(4).

Punday, D. (2004). Involvement, Interruption, and Inevitability: Melancholy as an Aesthetic Principle in Game Narratives. SubStance, 33(3), 80-107.

Reisner, C. (2013). “The Reality Behind It All Is Very True”: Call of Duty: Black Ops and the Remembrance of the Cold War. In A.B.R. Elliott and M.W. Kappell (Eds.), Playing with the Past: Digital Games and the Simulation of History (247-260). New York: Bloomsbury.

Richardson, T. (2004). JFK Assassination Game Branded ‘Despicable.’ The Register. Retrieved January 19, 2012, http://www.theregister.co.uk/2004/11/23/jfk_game/.

Salvati, A.J. and Bullinger, J.M. (2013). Selective Authenticity and the Playable Past. In A.B.R. Elliott and M.W. Kappell (Eds.), Playing with the Past: Digital Games and the Simulation of History (153-167). New York: Bloomsbury.

Schott, G. and Yeatman, B. (2005). Subverting Game-play: JFK Reloaded as a Performative Space. The Australasian Journal of American Studies, 24(2), 82-94.

Schulzke, M. (2013). Refighting the Cold War: Video Games and Speculative History. In A.B.R. Elliott and M.W. Kappell (Eds.), Playing with the Past: Digital Games and the Simulation of History (261-275). New York: Bloomsbury.

Schut, K. (2007). “Strategic Simulations and Our Past: The Bias of Computer Games in the Presentation of History.” Games and Culture, 2(3), 213-235.

Sicart, M. (2011). Against Procedurality. Game Studies, 11(3), http://gamestudies.org/1103/articles/sicart_ap.

Staiger, J. (1996). Cinematic Shots: The Narration of Violence. In Vivian Sobchack (Ed.), The Persistence of History: Cinema, Television and the Modern Event (39-54). New York: Routledge.

Tanine A. (2010). The World War II Video Game, Adaptation, and Postmodern History. Literary Film Quarterly, 38(3), 183-193.

Treyarch. (2010). Call of Duty: Black Ops. [Wii], USA: Activision, played December 2011.

Uricchio, W. (2005). Simulation, History, and Computer Games. In J. Raessens & J. H.Goldstein (Eds.), Handbook of Computer Game Studies (327-38). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Vågnes, O. (2011). Zaprudered: The Kennedy Assassination Film in Visual Culture. Austin: University of Texas Press.