Mustaches, Blood Magic and Interspecies Sex: Navigating the Non-Heterosexuality of Dorian Pavus

by Gaspard PelursonAbstract

Dorian Pavus from Dragon Age: Inquisition has sometimes been described as a "breakout gay game character." While video games are now catching up on LGBTQ representation, only a few characters are granted a role that is as significant as that of Dorian. This article explores the negotiations of game communities towards Dorian, and more generally sexually distinct characters. It reflects upon the attitudes of the game communities towards the representation of non-heterosexuality in video games and the challenges and opportunities of creating a playable gay character in a video game. Forum comments reveal that LGBTQ gamers are divided. Indeed, some read Dorian as a gay stereotype while others read Dorian as a faithful representation of LGBTQ individuals. However, some game fans move beyond this duality by producing and sharing fan-arts and fan-fiction which depict inter-species sexual intercourse between Dorian and one of his non-human teammates. I argue that these artworks encourage a reading of Dorian that is queer as they fall outside the representation of the hegemony of both heterosexuality and homosexuality.

Keywords: queer theory, Dragon Age: Inquisition, gaymers, stereotypes, interspecies sex

Introduction

Striding across the forests, bogs and mountains of Thedas would have never been the same without Dorian. His jokes and wit, but also his great sense of fashion and convenient magic made him an indispensable companion. Of course, as a "gaymer," I am indubitably biased: having a handsome gay dandy mage by my side is rare in a gamer's life. Needless to say, I was more than thrilled to have face-to-face interactions and eventually share more intimate moments with the mage in my avatar's room. I am far from being the first one to write about their love for Dorian Pavus and some would even say that I am late to the party. Indeed, much ink has been spilled on the fact that Dorian is, according to BioWare's lead writer David Gaider, the first "fully gay" (Gaider, 2014a) video game character.

This claim was something that Gaider later regretted making (Dumitrescu, 2014), not least because it indirectly dismissed bisexuality and types of fluid sexuality that had previously appeared in video games, a particular aspect that many fans complained about on social media (Grill, 2014), accusing Gaider of being disrespectful towards fluid sexualities. Other (presumably straight) video game commentators such as MundaneMatt (2014) questioned the point of such a claim, reproaching BioWare to market their characters. As a result, Gaider felt impelled to clarify that he meant that Dorian was only attracted to men, but also indicated that his mention of Dorian being "fully gay" was not an official press release and deplored that some fans misunderstood his words (Grill, 2014).

Most LGBTQ game characters who flout gender and sex roles "usually [are] minor characters; mostly predatory or lecherous men included for comedic effect" (Mulcahy, 2013). Compared to straight characters, they are often reduced to demeaning roles (Kies, 2015, p. 213) that have little direct involvement or ability to interact within the confines of the game. Conversely, not only is Dorian romanceable[1], he is also arguably the first playable gay character both within the BioWare games catalogue, and more broadly across AAA games.

However, having a gay character in an AAA video game does not mean that the industry should be considered progressive, or that it has begun to fully cater to a LGBTQ audience. Indeed, as Shaw (2009) argues, a significant segment of the LGBTQ gaming community does not wish to be particularly marketed to, mainly because a game about LGBTQ content is likely to appear "preachy," or because of the stereotypes and prejudices attached to it. Shaw argues that "gaymers" are "well versed in the subversion of texts" (p. 231), and that queer readings that "allow audiences to compensate for a lack of representation do not preclude a demand for representation" (p. 232). This leads her to conclude that not being "referred to in the [gaming] public discourse is just as problematic as being referred to stereotypically" (p. 231). Shaw's work points that LGBTQ stereotypes are often perceived as being negative and harmful to LGBTQ identities. As such, and while ostensibly representing a confident move forward in terms of LGBTQ representation, Dorian has not achieved unanimous support among gamers – LGBTQ or otherwise. That said, while he is imperfect, there seems to be a general agreement about the fact that Dorian is depicted "positively" (Karmali, 2015).

In her discussion of the Mass Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game (MMORPG) Star Wars: the Old Republic (SWTOR) (Bioware, 2011), Megan Condis (2015, p. 203) argues that several gamers still show resistance towards the inclusion of non-heterosexual characters and practices. Meanwhile, BioWare caused great controversy when they revealed plans to censor the use of words such as "gay" and "lesbian" on their forums in order to prevent derogatory and offensive uses of these terms (Sliwinski, 2009). While the word gay is often used to refer to anything "unmasculine, non-normative, or uncool" (Thurlow, 2001, p. 26), BioWare's plan was criticised for furthering the marginalization of the gay and lesbian community by censoring them (Condis, 2015, p. 202). The ban was finally lifted with an apology; yet, several gamers supported BioWare's decision and argued that video games, as virtual spaces, should be located outside the "real world," and that including LGBTQ content (in games or discussions of games) was breaking this barrier (p. 203). Through her case study, Condis demonstrates how all things encompassing queerness in the gaming community are considered an "aberration or an outlying position creating by privileging straightness" (Warner, 1993, p. xxi). BioWare ended up including a "gay planet" via an optional downloadable content (Hamilton, 2013), but the damage had been done and the planet was mostly perceived as another way of ostracizing the LGBTQ community. Fortunately, BioWare made amends for this faux pas by engraining a strong and inclusive politics in its offline franchises Mass Effect (2007-present) and Dragon Age (2009- present).

As of 2017, the Dragon Age (Bioware, 2009-present) and Mass Effect (Bioware, 2007-present) franchises arguably display the most diverse cast of LGBTQ characters and relationships. While the first two instalments of DA and ME were not considered inclusive enough as they presented limited same-sex options[2], these games are at present considered to be some of the few that depict non-heterosexuality in a positive light (Kies, 2015, p. 214). However, BioWare's move was not welcome by all gamers. Studying the romancing system of DA2 (2011), Peter Kelly (2014) mentions how BioWare's take on romance and sexuality bothered a minority of straight gamers who felt "neglected" (p. 46), but also put a heavy responsibility on the studio to represent non-heterosexuality "fairly" (p. 50) for their queer gamers.

Yet, this did not stop the company to go further and include the full spectrum of L, G, B and T[3] in Dragon Age: Inquisition (Bioware, 2014). DA:I stands out as a progressive game because it actively creates LGBT characters in a game world instead of simply allowing same-sex pairing. It differed from most older games as it provides characters who "exist out in the open," "regardless of the player's choices and actions," while "someone could easily spend hours in a game like The Sims (2000- present) and never know the option for same-sex couples even existed" (Kane, 2015, n.p.).

Although these games are not without their limitations, particularly because some of the romances available in the earlier games are still produced for the heterosexual male gaze (Glassie, 2015, p. 162), they offer a refreshing alternative to the overwhelmingly hypermasculine narratives that continue to populate fantasy and science-fiction games today (Hollinger, 1999, p. 24). This is often made possible by an increasing diversification of developer teams, which is the case of DA:I. Indeed, DA:I's narrative was created by Gaider, who is openly gay and who surrounded himself with female co-workers (Theora, 2016; Hernandez, 2012). Gaider praised the influence his female colleagues had on the writing of the romances, particularly because a lot of video games (and even those that would be considered progressive) still depict situations that are not far from rape or rely on forms of implicit sexism or outright misogyny (Hernandez, 2012). In this way, BioWare has positioned itself as a developer that is keen to promote diversity and represent gender and sexual minorities (Gaider, 2014b).

In this article, I explore the challenges and opportunities presented by a character such as Dorian. Through an analysis of forum comments about Dorian, I map out the unstable politics of gay male representation within the context of contemporary video game culture. I begin by analyzing criticisms of Dorian, and identify two lines of reasoning that these critics adopt. These two lines of criticism focus on and signify the fact that, despite BioWare's progressive take on sexuality, Dorian is still considered stereotypical. Following an in-depth analysis of this criticism, I explore how Dorian speaks to LGBTQ politics of post-Stonewall identity construction through the analysis of forum comments that celebrate and praise Dorian as an aspirational character. Finally, I argue that while several aspects of Dorian define him as a gay character, he should not be excluded from queer readings. Through the study of transformative works, and in particular fan art that builds upon the relationship between Dorian and the Iron Bull, I argue that Dorian can be positioned beyond the debate between stereotypes and a "true" gay identity, and ultimately recuperated as a queer figure. I demonstrate that while his relationship is ambivalent as it mirrors heteronormative traits, it still sheds a positive light on non-normative sex and love.

Methodological Details

This chapter's data was gathered from forum threads and YouTube videos which were selected through a combination of key words[4] on Google, Bing and Yahoo!. Privileging diverse and quality forum conversations, I paid particular attention to the flow of online debates and dismissed threads that quickly went off topic. In addition to the aforementioned criteria, I focused on comments which introduced new debates, were detailed and articulate. Overall, I selected nine forum threads and two YouTube videos which included at the time of this research 1567 comments. I also ran text queries on the qualitative data analysis software NVivo, using the same combination of key words. I then selected and archived 51 comments on word documents.

While this thesis follows the MLA style of referencing, I made an exception for forum references in the interest of transparency and clarity. Hence, instead of indicating the names of the website, or the author of the comment, I directly refer to the title of the thread. This enables me to clearly differentiate threads that would be on the same website (Harvard style would only differentiate by dates and letters), and also gives the reader more information about the nature of the forum conversations.

Coupled with forum comments, I included pieces of fan art in the corpus of primary material during the writing of the last section. On top of adopting an intersubjective and intermediated approach, these artworks served as illustrations of a greater corpus of transformative works (such as fan fiction), which specifically focus on a queer side of Dorian, his optional inter-species relationship. Since this aspect was not the primary focus of this chapter, fan artworks were a sufficient way to obtain a general understanding of how 'Adoribull' — the portmanteau referring to Dorian's inter-species relationship — was approached in the fan fiction community. Contrary to forum comments, most fan art conveyed a very similar vision of the relationship (tender, happy and kinky) which enabled me to restrict this research to a small sample of four artworks.

Introducing Dorian Pavus

Dragon Age: Inquisition (DA:I) is an action role-playing game structured around main quests, which allow the plot to unfold, and side quests, which offer additional experiences and cut-scenes. Most of the quests require the player to kill enemies, loot equipment, talk to NPCs[5] and explore new areas in exchange for experience. The plot is set in a world called Thedas and follows the main character, called the Inquisitor, whose gender, race and class (warrior, mage, rogue) is chosen by the player. The Inquisitor sets out on a quest to close the "Breach," a gigantic tear in the sky which allows demons to terrorise Thedas. The aim is to gather enough strong members of a fellowship called the Inquisition in order to stop Corypheus, a demon who opened the breach in an attempt to conquer Thedas. Each member of the Inquisition freely and willingly joins the fellowship and has their own backstory. Dorian Pavus is one such member (Picture 1).

Picture 1. DorianPavus by BioWare, Dragon Age Wiki, Public Domain (click to expand).

Dorian comes from Tevinter, a northern region of Thedas. The Tevinter Imperium is a decaying but still powerful magocracy that is notoriously decadent. Powerful houses fight for dominance and vie for the perfection of their bloodlines through careful matchmaking strategies, following politics and practices that are reminiscent of eugenics. Being openly gay and refusing to perpetuate his bloodline with the female companion chosen for him, Dorian's backstory involves him running counter his father's plans and since "every perceived flaw — every aberration — is deviant and shameful" in Tevinter (Dragon Age: Inquisition 2014), Dorian's father previously schemed to "change" him through the use of blood magic[6]. Before his father could act, however, Dorian left Tevinter and cut links with his father.

The Mustachioed Mage: Dorian as a Gay Stereotype

We are NOT all flamboyant, sex crazed, walking LGBT[Q] stereotypes irl so why are we being represented this way? […] Seriously Dorian & Sera are walking stereotypes and that just pisses me off to no end ('As much as I love Dorian…', 2015, 1).

Not all gamers welcome the introduction of LGBTQ characters such as Dorian into video games. As the comments above indicate, many of Dorian's traits — flamboyance, flirtatiousness, being overtly sexual — are perceived by some as being negative stereotypes that harm LGBTQ people. Out of 162 comments debating whether Dorian was a stereotypical character, only 9 (approximately 5.6%) considered Dorian to be a negative stereotype and 21 (12.9%) expressed mixed views (see Table 1). While these comments are a minority, they illustrate the views and arguments that still fuel debates in game studies, and LGBTQ identity politics more widely.

Dorian is not seen as a stereotypical character and his storyline is not defined by his sexuality. |

Dorian might be stereotypical and/ or his sexuality might be given too much attention, but he is still represented in a positive light. |

Mixed views. |

Dorian is a stereotypical character and/or his storyline focuses too much on his sexuality. As a result, he is represented in a negative light. |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

‘As much as I love Dorian…’ |

39 |

10 |

11 |

4 |

'How do you feel about Dorian Pavus’ Homosexuality?’ |

18 |

11 |

5 |

1 |

‘How can someone NOT romance Dorian?’ |

3 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

‘Why the straight male romance option suck?’ |

5 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

‘Does Dorian look like Freddy Mercury to anybody else?’ |

2 |

4 |

||

‘How do you feel about Dorian Pavus’ Homosexuality? |

20 |

9 |

2 |

|

‘So how many straight males romanced Dorian?’ |

8 |

1 |

||

Total |

95 |

37 |

21 |

9 |

Table 1. Readings of Dorian.

It is true that Dorian may be a convincing illustration of what Dyer (1980, p. 31) has previously termed "gay iconography" as the mage embodies several of the stereotypical traits that have previously been used to suggest homosexuality in Hollywood cinema. Dyer defines iconography as a "certain set of visual and aural signs which immediately bespeak" a symbolic representation (in this case homosexuality) and which "connote the qualities associated, stereotypically, with it" (p. 31). In this way, gay male iconography manifests itself through an "over-concern with appearance" and an association with a "good taste that is just shading into decadence" (p. 32).

This concern with appearance is pointed out by several other characters of DA:I, who often tease and criticize Dorian for his dapper style. For instance, the mage Solas comments on the futility of Dorian's "flashy" moves (DA:I, 2014), clearly indicating that the latter willingly puts on a show as he displays his magical abilities. Meanwhile Vivienne, a high ranked enchantress who does not hold Tevinter mages in her heart, recognises that "he does have a great sense of fashion" (DA:I, 2014). Indeed, most members of the Inquisition at some point comment on the Dorian's refined style of dress and well-groomed appearance.

However, beyond his clothing and attention to detail, one particular aspect of Dorian's grooming caught the eye of several forum users: his impeccable moustache. Indeed, four of the ten forums selected for this research included at least one post about Dorian's facial hair. Several gamers compared Dorian's moustache to that of Freddy Mercury, implying that it should be read as a gay characteristic:

[From] the moment I saw a video of him I just assumed he was gay, because he reminded me of how I picture Freddie Mercury ('How do you feel about Dorian Pavus' Homosexuality?', 2015).

I dunno why but every time I see Dorian all I can think of is putting the Freddy Mercury mustache on him and they'd look exactly alike ('Does Dorian look like Freddy Mercury to anybody else?', 2015).

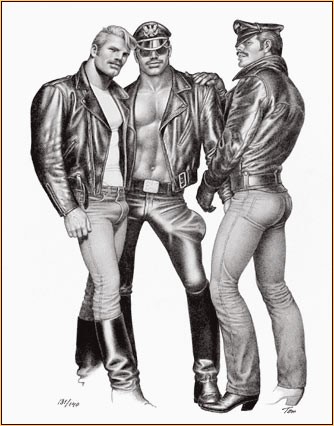

The moustache is a perfect illustration of Dorian's reading as a stereotype as it is also reminiscent of those found in artworks by a Finnish artist who had a major influence in shaping today's gay iconography – Tom of Finland. Famous for his homoerotic drawings (Picture 2), it is said that he inspired the look of both Freddie Mercury and the Village People (McCormick, 2016). Albeit slightly more proportioned, Dorian's muscles and moustache are very similar to Finland's policemen, sailors and leather men. John Mercer (2003) argues that Finland, along with other illustrators such as Harry Bush, Rex and George Quaintance, had a major impact in the "formulation of a paradigm of erotic Prototypes of gay porn" (p. 287) and, more generally, gay iconography.

Picture 2. A Tom of Finland's drawing of three men in their leather gear, by Tom of Finland, EUNIC London, Public Domain.

For instance, "the Leatherman had no explicit representational existence until Tom of Finland's illustrations of the 1950s and 1960s." Today, this figure — and Finland's work — still plays a central role in the "repertoire" of homoerotic figures that populate media representation (p. 287). Hence, by immediately associating Dorian's facial grooming with Mercury's moustaches, these comments understand the moustache as a gay trope of a particular kind.

Along the same lines, I gathered no less than fifteen comments which focus on two clichés regarding gay characters in popular culture – that of the gay man as a sexually unthreatening character and as being an "accessory" for straight individuals.:

I instantly loved him. He's my favorite [sic] mage and will always bring him with me now. ('How can someone NOT romance Dorian?', 2014, p. 2)

Dorian often appears in these comments as nothing more than the "funny sidekick" – a figure, often depicted hanging out with straight women in TV series and movies such as Sex In The City (1998-2004), Will and Grace (1998-2006), Bridget Jones's Diary (2001) and The Object of My Affection (1998). Their relationship with other women is based on "safe eroticism" (Dreisinger, 2000, p. 6), often reducing the gay man to the position of being the fag hag's ultimate accessory (Owens, 2015), mainly supporting female lead characters and allowing them to shine (Richardson, 2012).

As I indicated at the beginning of this section, not all forum users were happy with the representation of Dorian as a character who shows traits that are reminiscent of gay iconography. Indeed, while they remained a minority, negative and mixed comment about Dorian could be found in the seven forums selected for this research, showing that Dorian is not universally popular. These comments often expressed their annoyance about Dorian's flamboyance or found him stereotypical and offensive:

With Dorian I'm almost surprised he doesn't come pre-packaged with a limp-wrist, a handbag, some lip-gloss and an ipod filled with Cher's greatest hits since they're clearly trying to go for "offensive stereotype" with him. I haven't heard him speak yet but I'm guessing based on his flamboyant and FAB-U-LOUS character design they're giving him a lisp? […] If they didn't want to add a gay character why didn't they just leave it at that instead of producing this grotesque parody of what people thought a homosexual looked like back in the 1950s? ('So how many straight males romanced Dorian?', 2015)

Because I'm a heterosexual male. I find him annoying and arrogant, to be honest ('How can someone NOT romance Dorian?', 2014, p. 1).

As such, these two comments complain about Dorian's representation for different reasons. The first comment echoes the two forum posts which introduced this section, and see Dorian as an outdated and offensive cliché. They consider BioWare's attempt to convey progressive politics as a failure, and argue for a less flamboyant representation of LGBTQ characters. The last comment illustrates the concerns of those previously mentioned: Dorian, as a gay character, is annoying to straight gamers. The latter are, therefore, unlikely to learn more about him and, by extension, LGBTQ identities.

As such, these comments illustrate the fears of LGTBQ gamers who do not think that Dorian will help easing the assimilation of LGBT individuals. In this respect, these comments echo the debates revolving around the identity politics of the first decade after the Stonewall Riots (Gross, 2005, p. 518). Indeed, post-Stonewall identity politics focuses on challenging the "overwhelming invisibility broken occasionally by representations of sexual minorities that were negative, limiting, and demeaning" (p. 518). Organised gay movements in the 1970s made efforts to improve the ways television network programmers handled LGBT representation (Montgomery, 1981; Moritz, 1989). There was an attempt for the LGBT community to historically construct its own identity and reinvent itself "out of a paradigm of referents belonging to an oppressive heterosexual culture" (Mercer, 2003, p. 286). Ultimately, the main project of post-Stonewall politics was to "rehandle gender assignment and gender hierarchy, and hence to repel the stigma of effeminacy," which involved "claiming masculinity for gay men, declaring that gay femininity is all right, and various combinations of these" (Sinfield, 1997, p. 205).

While it is unclear whether or not the gamers quoted in this section declare that gay femininity is "all right" (and, therefore, move away from the final aim of post-Stonewall politics), they clearly do not see Dorian as a character who has the potential to challenge gender normative attitudes, and imply that BioWare have failed to produce a character that empowers LGBT people. In this way, these gamers illustrate that the rationale of post-Stonewall politics — here mainly understood as positive identity politics — still applies today.

Nevertheless, the fear that Dorian might not positively represent gay individuals also seems to illustrate these gamers' uneasiness about visibility. As such, even the comments criticizing Dorian for being offensive might not advocate for a more liberal agenda. This contradiction is reinforced by another group of comments which specifically deplore the significant role given to Dorian's sexuality in his personal arc[7]:

I'm disappointed in BioWare for his personal arc. Most writers seem to have yet to realise that gay characters can have personal issues that are unrelated to their gayness. Shocking stuff ('How can someone NOT romance Dorian?', 2014, p. 4).

He's by far my favorite character in the game; I love the banter he has with Sera and Varric, and he has a voice I bloody wish I had. But I'm a little disappointed that his personal mission was solely based on him being gay ('As much as I love Dorian….', 2015, p. 1).

These gamers see Dorian's distinct narrative as another stereotype of gay narratives. As such, they might appreciate Dorian as a character, but not his backstory, which is further developed in his personal quest. In this, these comments express the wish for "divergent modes of validation" (Sinfield, 1997, p. 206), by finding Dorian's gay narrative too distinctive from straight narratives, particularly because, according to them, it mainly focuses on his sexuality. As such, these arguments do not actually side with post-Stonewall identity politics, but run against them, as they support an equal treatment to characters of all sexualities. In that, they echo one of the main counter-arguments to post-Stonewall views according to which "our gender attributes (whatever they are) don't make us very different from other people." As such, "homophobia [becomes] just a misunderstanding" (p. 206.) and assimilation is key.

Some might even argue that the politics of assimilation is gaining ground. Indeed, scholars have noted a tendency among millennial gays to shun labels (Savin-Williams, 2005), detaching themselves from "historical understandings of what it means to be gay" (Westrate & McLean, 2010, p. 228). Consequently, a significant part of the millennial generation argue that we might be "growing out of 'gay'" (Sinfield, 1998, p. 1) and that we have reached a "post-gay era" (Westrate & McLean, 2010, p. 237; Cohler & Hammack, 2007) represented by a diversification of gay narratives. While it is impossible to determine the age of these gamers because of the forums' anonymity policy, these gamers' complaints bear strong similarities with the views of the millennial generation. They deplore the lack of "multiplicity" (Westrate & McLean, 2010, p. 237) in the portrayal of gay narratives in video games, presenting Dorian as "tedious," "contrived" and "boring" because his sexuality plays a central part in his story-arc. Hence, in the context of an era where there is no need to define or distinguish oneself through sexuality, the flamboyant dandy appears as an outdated and harmful trope.

Thus, Dorian as a gay character is criticised by two different sets of identity politics. His personality traits and physical attributes can be associated with stereotypical gay iconography. Consequently, some gamers read him as another stereotypical and negative representation of LGBTQ identities in video games, while a second group of gamers judge that he delivers a gay narrative that has become unnecessary and obsolete in today's society. As such, most comments in this section expressed views that seem to genuinely support LGBTQ identities, despite their disagreement with BioWare's methods.

However, while Dorian might appear as an embarrassing stereotype to the eyes of some, arguing that we are "past accepting gays" ('How can someone NOT romance Dorian?', 2014, p. 6) and that BioWare privileges queer gamers (Kelly, 2014) blatantly ignores the inequalities and remaining oppressive environment towards women and LGBTQ gamers in video game culture. Recent controversies such as GamerGate illustrate the necessity to portray distinguishable LGBTQ characters, particularly if they still resonate with a lot of gamers.

The Moving Mage: Dorian as a "breakout gay character"

Righteous dismissal does not make the stereotypes go away, and tends to prevent us from understanding just what stereotypes are, how they function, ideologically and aesthetically, and why they are so resilient in the face of our rejection of them. In addition, there is a real problem as to just what we would put in their place (Dyer, 1980, p. 27)

The idea that Dorian's personal arc is stereotypical needs to be qualified. Indeed, stereotypes are dangerous because they make the audience, and more particularly the gay audience, believe "[…] that the stereotypes are accurate and act accordingly in line with them" (Dyer, 1980, p. 32). Stereotypes connote a wealth of meanings and are similar to ideology in that "they are both (apparently) true and (really) false at the same time" (Perkins, 1979, p. 155). Stereotyping exposes individuals who are "different from the majority" (Hall, 1997, p. 229) through binary forms of representation. As a result, LBGTQ stereotypes are harmful because they exclude LGBTQ people and make them "fall short of the 'ideal' of heterosexuality (that is, taken to be the norm of being human)" (p. 31). However, this does not prevent LGBTQ individuals from being regularly exposed to and confronted with these same "failing" stereotypes. Williams et al. (2009) demonstrate that LGBTQ employees are often expected by their coworkers to dress and behave in ways that relate to LGBTQ culture, no matter how tolerant their work space can be. Along the same lines, Mitchell and Ellis (2010) show that American college students tend to immediately attribute cross-gender characteristics to a person who is labeled gay. Thus, it comes as no surprise that Dorian, a character who was announced as gay before the release of the game, is read by several gamers through gay stereotypes.

Nevertheless, Dorian's story is not essentially stereotypical. While some aspects of his life, such as his sexuality, play an important part in some of his cut-scenes, most of the stereotypes attributed to him could, "in the larger context" ('As much as I love Dorian….', 2015, p. 13), be ruled out. For instance, Dorian does not talk about the difficulty of coming out, but about the refusal to adhere to Tevinter's eugenics, which encourage reproduction between people from high lineages. However, it is not Dorian's desire for other men that upsets his father, but his inability and (more importantly) his refusal to produce an heir. There is, therefore, a nuance here, between the idea that Dorian's father potentially tolerates his son's sexuality, but does not accept its consequences. Indeed, out of the 161 comments debating stereotypes, 95 comments (approximatively 58.6%) disagreed with the idea of Dorian being stereotypical and 37 (22.8%) agreed to a certain extent, but did not think that it was harmful or unrealistic:

Having friends who are gay, that cutscene hit really hard. One of my favorite characters was experiencing the same thing as one of my close friends. I couldn't help but feel some more bro-love for him ('So how many straight males romanced Dorian?', 2015, n.p.).

I've recently done Dorian's personal quest, and to be honest...I like [italics] the heavy-handed aspect of it, given that it's something that actually happens [italics] to gay people in real life ('Dragon Age Inquisition players: How do you feel Bioware handled Dorian's sexual orientation?', 2014, p. 1, p. 3).

As these comments indicate, Dorian's storyline immediately evokes the memory of the user's personal experience about navigating homosexuality in a family environment. Furthermore, they illustrate that stereotypes do not automatically make a story less realistic. On the contrary, the second comment illustrates how they can function as a tool that reinforces the politics of its narrative. Stereotypes are a double-edged sword: they are generally created by the hegemony to marginalise a specific group, who can in turn reappropriate and use them as tools to resist and "fashion the whole of society according to their own world-view, value-system, sensibility and ideology" (Dyer, 1980, p. 30). Stereotypes have a strong transgressive potential: LGBTQ clichés run counter the "typically masculine" and the heterosexual "sex-caste" (p. 31). Instead of shunning stereotypes, LGBTQ individuals, as this second comment suggests, should celebrate and navigate them, no matter how heavy-handed they might be.

In this way, Dorian can be read as a strong and relatable gay character. As one of the first video game gay characters to hold such a significant positive presence, he embodies the continuation of a fight that started with the Gay Liberation movement of the 1970s, standing as "an appropriate response to invisibility and a history of negative images was the construction and circulation of positive ones" (Arroyo, 1997, p. 70). Concentrating on gay narratives that focused on themes such as "Stonewall, AIDS, and the gay rights movement," the "rise of gay culture" (Harris, 1997, p. 236) of the 70s and 80s fought the silencing of gay life stories. Similarly, Dorian resists a gaming environment that can be hostile to any significant change. As these comments indicate, Dorian has the potential to have a positive impact on gaymers as several elements of his narrative deliberately moved them.

A reading of Dorian as a flagship of positive representation would not be complete without a brief mention of his romance option. Although his gameplay does not diverge widely from the other mage characters — Vivienne and Solas — several gamers mention how influential his (interactive) dialogues were in their choice of including Dorian in their party. Indeed, in 'So, how many straight males romanced Dorian?', 30 comments out of 271 specifically indicated that presumably straight forum users chose Dorian as their first in-game romance or decided to start a new game to be able to romance him ('So how many straight males romanced Dorian?', 2015). 15 forums users wrote that they decided to romance another character while the rest of the comments were mainly answers to these posts, jokes and subconversations that were off-topic. Hence, Dorian won a significant number of straight gamers over with his wit and charisma, including The Guardian journalist Kate Gray (2015), who writes about the entanglement between herself and her avatar.

These experiences echo Waern's (2014) argument regarding the potential of the Dragon Age franchise to offer powerful gaming experiences. Waern focuses on the concept of "bleed," comprised of two main effects: "bleed-in," which refers to the influence of a player's emotions over the playing of a game character, and "bleed-out" (p. 28), where both player and character share the same emotions. In this light, Dorian's "snark" and "humour" made his romance a "heartwarming" and "touching" experience (So, how many straight males romanced Dorian?, 2015) which conveys a strong bleed-in effect.

Thus, thanks to the quality of the crafting of his character and the possibility to pursue a same-sex romance with him, Dorian stands as the flagship of BioWare's politics of "positive representation." Using games as a medium that creates new worlds and "invite[s] players to take on various identities within them" (Gee, 2007, p. 145), BioWare enables gamers to playfully explore gay romance and, hopefully, come to terms with some of the stereotypes related to gay identity (Karmali, 2015). As a result, DA:I serves as a platform which enables some gamers to challenge players' taken-for-granted views about LGBTQ identities (p. 145), or at least facilitates debates about these views to take place. The emotion provided "lies in the interplay between how and why players like to indulge in romance, and in how the game design supports and actively endorses such indulgence" (Waern, 2014, p. 42).

However, Dorian should be approached as more than an example of positive gay representation. Indeed, if Dorian is not romanced by the main character, he might start a relationship with the Iron Bull, a non-human pansexual warrior. This unusual relationship redefines Dorian's sexual identity, and allows for a new queer reading of this extravagant mage.

The Mage and The Bull: Dorian's Secret Queer Love

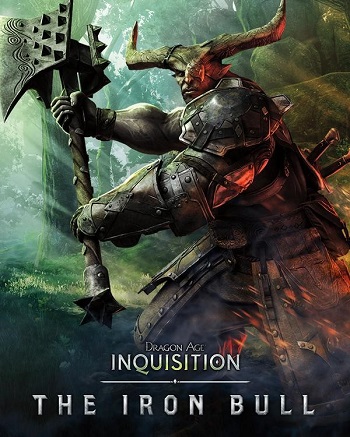

The Iron Bull (Picture 3) is a pansexual Qunari — a metallic-skinned race of giants — mercenary who joins, like Dorian, the main character to close the Breach. If the player refuses to intimately interact with both characters, there is a chance of a romance developing between the two. When teamed up, the mage and the bull start having in-game banter. Their innocent teasing quickly takes a more flirtatious turn, particularly when the Iron Bull reveals that Dorian pays him nocturnal visits:

Iron Bull: Quite the stink-eye you've got going, Dorian.

Dorian: You stand there, flexing your muscles, huffing like some beast of burden with no thought save conquest.

Iron Bull: That's right. These big muscled hands could tear those robes off while you struggled, helpless in my grip.

Iron Bull: I'd pin you down, and as you gripped my horns; I. Would. Conquer. You.

Dorian: Uh. What?

Iron Bull: Oh. Is that not where we're going?

Dorian: No. It was very much not.

Iron Bull: So, Dorian, about last night...

Dorian: (Sighs) Discretion isn't your thing, is it?

Iron Bull: Three times! Also, your silky underthings, do you want them back, or did you leave those like a token? Or...wait, did you "forget" them so you'd have an excuse to come back? You sly dog!

Dorian: If you choose to leave your door unlocked like a savage, I may or may not come.

Iron Bull: Speak for yourself. (DA:I, BioWare, 2014)

Picture 3. The Iron Bull, by BioWare, Dragon Age Wika, Public Domain (click to expand).

This interspecies coupling came as a surprise to a significant amount of gamers. This can be witnessed in the comment section of two YouTube videos — one including Dorian's flirtatious dialogues with the Iron Bull, and the other excluding them — where gamers express a wide range of reactions. A gamer declares that the relationship "rubs [them] the wrong way" and another confesses that they "cringed horribly" (Annatar, 2014). Others found it "hilarious," "surprising" and "unpredictable" (Danaduchy, 2015).

Taken aback by such an unusual romance, these gamers illustrate how interspecies sex, even in a fantasy setting, falls outside the "imagery" of "hegemonic representation" (Erhart, 2003, p. 174; Huebert, 2015, p. 254). Indeed, Dorian's relationship with the Iron Bull offers an unexpected alternative to the "binary constraints of gender and sexuality" (Zekany, 2015, p. 5). As a Qunari, the Iron Bull cannot be approached as a "gay human." Consequently, he represents an unknown realm: that of the sexual "other" (Tosenberger, 2008, 3.1[8]), which is "often coded […] as lesbian, gay or otherwise queer" (Benshoff, 1997, p. 6). Alien otherness can be also associated with Giffney and Hird's queer reading of "affective relations between human and nonhuman animals which encourage us to think about the animal as a symbol for representing non-normative love and the resistance to normative hegemonies" (2008, p. 10).

This relationship also poses "productive challenges to prevailing structures of sexual, political, and ideological hegemony" (Huebert, 2015, p. 257), which is "too much to handle" for some gamers. Coupling a mage and a Qunari — who is twice the size of the former — pushes the boundaries of the understanding of sex. However, DA:I does not leave the gamers' unanswered doubts about the possibility of these two characters having sex, and openly mentions the sexual challenges that such a relationship entails. In the case when the Inquisitor romances the Qunari, the latter verifies if he has what it takes to "ride the bull," clearly implying that the size of his penis might become a problem for someone that is inexperienced. After their first night, the Iron Bull asks another member of the Inquisition to leave the Inquisitor alone, implying that they need some rest. Human-Qunari sex is, therefore, presented as a physically and psychologically demanding practice and as uncharted territory to the eyes of the player. This sex act requires the Inquisitor to figuratively and literally take all this queerness in, leading to the creation of what we could call an "excessive" queer space (Jagose, 1996, p. 2), which ultimately stands as a milestone in the representation of queer sex in video games.

Nevertheless, the relationship between Dorian and the Iron Bull remains discrete, as it is reduced to a few dialogue lines and banter. During the final scenes of the game, the Iron Bull confesses to the Inquisitor that Dorian is a "good guy," and the latter expresses the wish to stay for a while in Thedas to be with the Bull. Leaving much to the imagination of the players, it can be argued that this pairing provides an incentive for gamers to celebrate queer sexuality through the creation of fan-fiction.

Fan-fiction, or transformative fiction, is "a genre that […] offers a form of commentary on the canon by introducing new perspectives and interpretations that subvert the original intention of the canon" (Leow, 2011, 1.1). While there are several types of transformative fiction, I focus in this chapter on the sub-category of slash fiction, "a slippery genre which has been defined […] as buddy-story bromance, romance, or just plain porn" (Flegel and Roth, 2010, 1.2). Indeed, the Dorian/ Iron Bull in-game relationship indubitably constitutes solid material for any slash-fiction writer as it starts as a "buddy-story bromance" of two characters that everything seems to oppose and then verges on erotic, as suggested in their dialogue lines.

As previously implied, slash-fiction involves "shipping" practices, a term used in fan-fiction to describe the pairing of previously created characters who are not together in the canon[9]. In this way, it could be argued that BioWare anticipated the shipping of Dorian and the Iron Bull, by consciously providing such an unusual relationship, and foreseeing that transformative work would follow. This was confirmed by lead writer David Gaider who indicated on his Tumblr that much of the Dorian/ Iron Bull relationship was left for fans to speculate over:

I'm not going to go into detail on what I think about it – most of their relationship is left undetailed, after all, and the player is only catching the very edge of it…thus I think it's a matter best left to headcanon[10] (Gaider, 2015).

While I indicated previously that several YouTube users reacted negatively to the dialogue between the two characters, others clearly rose to BioWare's bait and express their excitement about their "shipping" of Adoribull (Danaduchy, 2015). Indeed, it can be said that BioWare's strategy has been successful. At the time of writing, 555 fan-fiction stories focusing on Adoribull have been produced on Archiveofourown (AO3), one of the biggest archives of transformative work (Pellegrini, 2017), and hundreds of fan-arts depicting both characters can be found on the internet. As such, it can be argued that the "anticipated" nature of Adoribull shipping has been a success.

However, before delving into the complexity of Adoribull, I must first address the debates about the transgressive nature of regular shipping practices. A large body of academic work underlines the disruptive and political potential of fan-fiction. Lamb and Veith (1986) define slash fiction as a queer practice and argue that fan writers resort to using male characters in slash-fiction enable them to remove gender inequalities in their portraying of a relationship, which often result in male characters showing androgynous characteristics. Jenkins (1992, p. 210) perceives slash fiction as a means for slash to throw "conventional notions of masculinity into crisis by removing the barriers blocking the realization of homosocial desire." As such, slash fiction "unmasks erotics of male friendship, confronting the fears keeping men from achieving intimacy" (p. 210). In this, slash fiction is often associated with queer transgressive pleasure (Bury, 2006).

Yet, the perception of fan fiction as inherently transgressive is not universally shared. Victoria Brownsworth (2010), for instance, fears that the rising prevalence of straight female authors writing about male/ male relationships both removes the agency from queer writers and "fetishizes" (n.p.) queer sexuality, thereby reinforcing a generally negative perception of non-heteronormativity.

Popova (2018) adopts a more nuanced approach through the study of the "Omegaverse" (p. 6), a genre of fan-fiction that is structured through the repetition of common tropes, such as the attribution of a secondary gender following a rigid hierarchy. Although Popova provides surveys showing that fan-fiction is still largely dominated by non-heterosexual female and non-binary writers, she underlines that Omegaverse stories often "establish settings where gender inequality is not only present but taken to extremes" (p. 14). As such, Popova runs counter to the idea that fan-fiction is inherently equalitarian and genderless. However, she does not consider it to be a negative feature, but an opportunity for fan readers and writers to "explore the impact such power structures may have on pleasure and consent in intimate relationships" (p. 14). According to her, fan fiction should be perceived as a platform where strategies dealing with gender inequalities can be established rather than a queer equalitarian genre in itself.

In this light, the non-accidental shipping of Adoribull should not be seen as essentially more or less transgressive than regular fan-fiction. While fan writers do not twist or remove the in-game power dynamic shown between Dorian and the Bull, we should not immediately read this lack of transgression as an undermining of the potential queer disruption of fan-fiction. Firstly, the game only hints at the Adoribull relationship and does not provide more than a dozen dialogue lines, which enables fan writers to develop this relationship freely and divert from the original storyline. Secondly, this particular type of shipping prevents, as Brownsworth fears (2010), straight writers to claim ownership on this queer relationship since it was written and created by a gay man (David Gaider).

More importantly, instead of pitting anticipated shipping against regular shipping, we should question how the former affects the intertextual dynamic that defines fan-fiction. Indeed, fan-fiction is constantly "in dialogue with the source material […] they are based on" (Popova, 2018, p. 4), but also other fan works, allowing the building of a "never complete archive of works which are constantly in dialogue with each other" (p. 5). According to Yatrakis (2013, p. 64), fan-fiction is a great illustration of how "convergence culture" — the phenomenon according to which "consumers are encouraged to seek out new information and make connections among dispersed media content" (Jenkins 2006, pp. 2-3) — operates, as fandom sites and fan fiction afford consumers the opportunity to engage with alternative perspectives of cultural products and explore specific interests that would otherwise remain undocumented.

It can be argued that Adoribull demonstrates a full awareness of the intertextuality of convergence culture and entices writers and consumers to explore the interspecies relationship between the mage and the Bull. This choice of deliberately anticipating fiction can be read as a directed and political choice from BioWare, particularly because it is the only romance featuring two secondary characters which does not involve the player's intervention. As such, Adoribull can be seen as a discrete promotion of this queer relationship, ultimately encouraging gamers, fan writers and readers to approach the mage as more than a typical gay character.

This pairing also plays with the intertextual dialogue implemented by fan-fiction through shipping practices as a means to gain visibility. Indeed, the relationship between Dorian and the Bull is accidental, as it can only happen if both characters are in the party and have not been romanced. As such, it cannot be triggered voluntarily if one is playing the game for the first time without having read about it online. This was my personal experience as a gamer: I only discovered Adoribull through fan art and fan-fiction, and then went back to the game to trigger the relationship. As such, the fan art led me to the in-game dialogue between the two characters, which originally inspired the drawings.

Although the creation process of Adoribull is a particular case, the politics are comparable to what can be found in regular shipping practices in that they do not automatically convey queer, or 'queerer' politics than the original source. Indeed, browsing the synopses of the 555 Adoribull fan-fiction on Archiveofourown (AO3) rapidly shows that most stories follow the same structure: Dorian and the Bull are two characters that everything seems to oppose, yet they are unashamedly attracted to each other and decide to pursue a romantic relationship.

This is the case of the four most-read fan-fiction pieces of Archiveofourown[11]: "Drapetomania," "Savages," "Breaking Stereotypes" and "Project Ikimari." These four stories deal with undeniable queer elements such as the reliance on the aforementioned "Omegaverse," men getting pregnant, semi-hardcore BDSM and physical difference, but inevitably conclude their narrative with a sweet and romantic ending, presenting Dorian and the Bull in a monogamous and committed relationship, sometimes even with a child. Derecho (2006, p. 73) underlines that one of the crucial features of fan-fiction is that of "repeating with a difference" motifs, scenes and narrative development. While I do not claim that all Adoribull writings follow the same identical pattern, these four stories are indicative of the general structure of Adoribull's narratives. This claim is reinforced by the relatively homogeneous representation of the Adoribull relationship in fan-made artworks, which are also considered a type of transformative work. Indeed, searching for Adoribull images in any search engine inevitably leads to an endless flow of artworks depicting tender and romantic, rather than carnal, moments between the Mage and the Bull.

Thus, Adoribull adopts a contradictory position as it seems to be both assimilated and queer. In some ways, it follows heteronormative ideals such as monogamous love and feminine domesticity to homosexual romance (Flegel & Roth, 2010, 1.4). Consequently, the relationship becomes acceptable to the eyes of the mainstream, which "unqueers" the pairing by making it similar to homonormative and assimilationist models of romance and sexuality. Thus, the threat that this interspecies relationship represents is diminished, if not sugarcoated by normative ideals.

Nevertheless, Adoribull should not be dismissed for lapsing into sentimentality, precisely because it aims at bringing happiness and monstrosity together. Following Tosenberger (2008), fan fiction has the potential to subvert and queer an original text by allowing misfits to be happy. She takes the example of Wincest, one of the most prolific shipping of the internet based on the television series Supernatural (2005-present) (Baker-Whitelaw, 2014), which pairs up the two brothers, Sam and Dean Winchester, who are also the main protagonists of the TV show. According to Tosenberger (2008), this subverts the original text by making things "happy" for both Sam and Dean and giving them the "measure of comfort" (1.5) that is denied to them in the original series.

Overall, Adoribull aims at picturing the happiness of both characters. In this regard, it operates similarly to "Wincest," even though in most Wincest stories, "the incest taboo is the obstacle that Sam and Dean have to negotiate before their relationship can reach its full potential," however, "the payoff is not so much in the breaking of the taboo, but in the fulfilment — sexual and emotional — that comes afterward" (1.9). In this way, the taboo of incest becomes secondary and is eventually overshadowed. Hence, Tosenberger argues that the most subversive aspect of Wincest is not the depiction of homoerotic incest, but "its insistence on giving Sam and Dean the happiness and fulfilment that the show eternally defers" (5.1), and I add, on making incest socially acceptable in is fictional context.

Adoribull does not subvert the original text as much as Wincest, but pursues and strengthens the game's progressive stance by picturing what was only suggested: the two characters having "fun." Fan art further demonstrates this general move beyond heteronormativity by addressing the physical difference of the mage and the bull in a humourous way (Pictures 4 and 5), but still depicts their cuddles and sexual intercourses as tender and romantic (Pictures 6 and 7). In doing so, Adoribull's fan art exploits the pairing as a "queer zone of possibilities" (Jagose, 1996, p. 33), widening "a space in which the effects of the connections between romantic happiness and heterosexism can be more radically questioned" (Flegel & Roth, 2010, 5.2). Rejecting the vision of queer interspecies relationships as monstrous, they celebrate and reclaim them as an alternative (but also valid and desirable) romantic love story.

Picture 4. Adoribull 1, by Alphabetiful, Pinterest, Public Domain.

Picture 5. Adoribull 2, by Itachaaan, Tumblr blog, Public Domain (click to expand).

Picture 6. Drunk, by TareNagashi, Tumblr blog, Public Domain.

Picture 7. Adoribull 3, by Ionicera-caprifolium, Tumblr blog, Public Domain (click to expand).

These pieces of fan art convey solid politics of resistance against heteronormativity. They first redefine the Iron Bull, a seemingly queer "abjected figure" (Hollinger, 1999, p. 35), as a valid and arguably desirable romantic partner, thereby allowing both characters to successfully overcome their cultural and physical differences. In this way, Adoribull "resists the compulsory heterosexuality of culture at large" (Tosenberger, 2008, 1.3) by sweeping heteronormative concerns away. Ultimately, these fan artworks reflect upon the queer potential of the heroic fantasy genre. In the depiction of this fantastical relationship, they use "the culturally distant settings of […] fantasy [to] clearly present writers with both the opportunity […] to explore gender variations" within homosexual (and queer) acts and "separate these acts from culturally specific identities" (Woledge, 2005, p. 52). As a result, Adoribull challenges "coercive regime[s] of compulsory heterosexuality" (Hollinger, 1999, p. 23). It sheds a queer light on Dorian, who is a gay character with a "gay themed" narrative. Going beyond the questioning of gay and straight stereotypes, Adoribull approaches the "Uncategorisable," offering an unexpected and positive alternative to a straight, bi or gay romance.

Conclusion

To write that Dorian Pavus lives up to his name would be an understatement. As the subject of several polemic discussions, I have demonstrated that Dorian made a mixed, but noticeable impression among the gaming community. Despite his strong popularity and DA:I's progressive approach, gaymers and gamers do not manage to agree on Dorian. For some, the mage is just another stereotypical character, following the norms of heteronormativity and damaging LGBTQ individuals. These gamers are followed by a second group who prefer to shun stereotypes and advocate for an assimilationist approach in the representation of LGBTQ minorities.

However, I have also shown that stereotypes are inevitably part of a wider societal structure. Consequently, they should not be shunned but used as a tool of resistance to promote that which goes against the norms of the ruling group that create them. Thus, despite his relatively stereotypical story, Dorian stands as the flagship character of BioWare post-Stonewall politics. Narrating a relatable story, Dorian also allows gamers to engage in a gay romantic relationship, delivering an experience that potentially enables them to empathise further with the LGBTQ community. In this way, Dorian's romance illustrates how games can enable players to share their avatar's emotions and empathise with their fate (Waern, 2014).

However, I have also shown that Dorian is not limited to his gay sexuality, and that the game also presents an interspecies relationship with the Iron Bull. I have argued that BioWare indirectly encouraged gamers and fans to build upon this queer relationship and promote alternatives to heteronormative romantic love. As I mentioned, there are, of course, limitations to my queer reading, such as the fact that transformative works aim at normalizing and making this relationship acceptable might ultimately compromise its disruptive nature. While the act of normalizing something disruptive might be enough to be considered queer, it also runs counter the essence of queerness, often defined as non-normative. In this light, Dorian may be more of an introductory than a key figure to visible queer sexuality in video games. Still, he remains, I hope, one of the first of a long list of human and non-human (but these already exist) characters who unashamedly live their queer sexuality in broad daylight.

Endnotes

[1]DA:I enables gamers to play several characters, but also to pursue a romantic relationship with them.

[2]The games mainly included bisexual characters, adapting to the main character’s sexuality.

[3]However, Krem, who is arguably the most significant transgender character in any Bioware title, is not playable.

[4]Dorian, Dragon Age, Stereotypes, gay, sexuality.

[5]NPC stands for non-playable characters.

[6]Blood magic is a deviant "school of magic that uses the power inherent in blood to fuel spellcasting and also to twist the blood in other for violent or corrupting purposes" (Dragon Age Wiki 2016).

[7]An arc is the part of a storyline that, in the case of DA:I, focuses on a specific character.

[8]The Journal of Transformative Work uses paragraph instead of page numbers, following a x.x numeration system

[9]Another word for ‘official’ used in fan fiction to differentiate between the official storyline in which a fan fiction is based on.

[10]The headcanon refers to a particular belief, elements or interpretations of a fictional universe by an individual, or several fans. By letting fans expand on the Adoribull romance, Gaider openly orients and encourages transformative work.

[11]All of these stories were searched more than twenty thousand times.

Bibliography

Annatar (2014). Dragon Age Inquisition Party Banter with All Companions. YouTube. Retrieved June 27, 2017 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ke2DTTs81g0

Arroyo, J. (1997). Film Studies. In Medhurst, A. and Munt, S. (eds), Gay and Lesbian studies (pp. 67-83). London: Cassell.

Baker-Whitelaw, G. (2014). This is what 1 million fanfics looks like. The Daily Dot. Retrieved November 11, 2016, from http://www.dailydot.com/fandom/ao3-million-fanfic/

Benshoff, H. (1997) Monsters in the closet: Homosexuality and the horror film. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Brownsworth, C. (2010). The Fetishizing of Queer Sexuality. A response. LambdaLiterary.org. Retrieved March 14, 2018 from https://www.lambdaliterary.org/features/oped/08/19/the-fetishizing-of-queer-sexuality-a-response/

Bury, R. (2005). Cyberspaces of Their Own: Female Fandoms Online. New York: Peter Lang.

Cohler, B.J. and Hammack (2007). The psychological world of the gay teenager: Social change, narrative, and "normality". Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 47-59.

Condis, M. (2015). No homosexuals in Star Wars? BioWare, ‘gamer’ identity, and the politics of privilege in a convergence culture. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 21 (2), 198-212.

Danaduchy (2015). DA: Inquisition. Last Resort of Good Men (all options). YouTube. Retrieved June 20, 2017 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c-Q6sl5_qBQ

Derecho, A. (2006). Archontic Literature: A Definition, a History, and Several Theories of fan Fiction. In Hellekson, K. and Busse, K. Fan Fiction and Fan Communities in the Age of the Internet (pp. 61-78). Jefferson: McFarland & Co.

Dragon Age Wiki (2016). Blood Magic. dragonagewikia.com. Retrieved November 23, 2016 from http://dragonage.wikia.com/wiki/Blood_magic

Dragon Age Wiki (2016). Qunari. dragonagewiki.com. Retrieved November 23, 2016 from http://dragonage.wikia.com/wiki/Qunari

Dreisinger, B. (2000). The Queen in Shining Armour: Safe Eroticism and the Gay Friend. Journal of Popular Film and Television, 28(1), 3-11.

Dumitrescu, A. (2014). David Gaider clarifies Dorian gay reveal for Dragon Age: Inquisition. news.softpedia.com. Retrieved April 24, 2017: http://news.softpedia.com/news/David-Gaider-Clarifies-Dorian-Gay-Reveal-for-Dragon-Age-Inquisition-449138.shtml

Dyer, R. (1980). Gays and Films. 2nd Ed. London: British Film Institute.

Dyer, R. (2013). Only Entertainment. 2nd Ed. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.

Erhart, J. (2003). Laura Mulvey Meets Catherine Tramell Meets the She-Man: Counter History, Reclamation, and Incongruity in Lesbian, Gay and Queer Film and Media Criticism, A Companion to Queer Theory. In Miller, T. & Stam, R. (eds), A Companion to Film Theory (pp. 165-181). Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell.

Flegel, M., Roth, J. (2010). Annihilating love and heterosexuality without women: Romance, generic difference, and queer politics in Supernatural fan fiction. Transformative Works and Cultures, 4. Retrieved June 27, 2016 from http://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/133/147

Gaider, D. (2014a). Character Profile: Dorian. Dragonage. Retrieved June 13, 2016 from https://www.dragonage.com/en_US/news/character-profile-dorian

Gaider, D. (2014b). A Character like Me: the lead writer of Dragon Age on inclusive games. polygon.com. Retrieved July 24, 2017 from https://www.polygon.com/2014/2/18/5422570/the-lead-writer-of-dragon-age-on-the-first-steps-towards-inclusive

Gaider, D. (2015). Are there people who […]. Tumblr. Retrieved July 24, 2017 from http://becausedragonage.tumblr.com/post/106629181352/i-have-a-question-that-im-not-sure-youd-want-to

Giffney, N., & Hird, M. (2008). Introduction: Queering the Non/Human. In Giffney, N., & Hird, M. (Eds), Queering the Non/Human (pp. 1-16). Farnham: Ashgate.

Grill, S. (2014). ‘Dragon Age: Inquisition’: gay character controversy causes BioWare writer to respond. Inquisitir. Retrieved March 14, 2018 from https://www.inquisitr.com/1335627/dragon-age-inquisition-gay-character-controversy-causes-bioware-writer-to-respond/

Gross, L. (2005). The Past and the Future of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Trangender Studies. Journal of Communication, 55 (3), 508-528.

Hall, S. (1997). Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. London: Sage.

Hamilton, M. (2013). Star Wars: The Old Republic, the gay planet and the problem of the straight male gaze. The Guardian. Retrieved January 25, 2016 from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/gamesblog/2013/jan/25/star-wars-old-republic-gay-planet

Harris, D. (1997). The rise and fall of gay culture. New York: Hyperion.

Hernandez, P. (2012). You Can Thank Women for Dragon Age 3’s Lack of Creepy Sex Plot. Kotaku. Retrieved September 9, 2016 from http://kotaku.com/5964700/you-can-thank-women-for-dragon-age-3s-lack-of-creepy-sex-plot

Hollinger, V. (1999). (Re)reading Queerly: Science Fiction, Feminism, and the Defamiliarization of Gender. Science Fiction Studies, 26 (1), 23-40.

Huebert, D. (2015). Species Panic Human Continuums, Trans Andys, and Cyberotic Triangles in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Transgender Studies Quaterly, 2 (2), 244-260.

Jagose, A. (1996). Queer Theory: An Introduction. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Jenkins, H. (1992). Textual Poachers: Television fans and Participatory Culture (Updated Twentieth Anniversary Edition). London: Routledge.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Karmali, L. (2015). How gaming’s breakout gay character came to be. IGN. Retrieved June 26, 2016 from http://uk.ign.com/articles/2015/07/09/how-gamings-breakout-gay-character-came-to-be

Kane, M. (2015). How ‘Dragon Age: Inquisition’ is helping to make a better future for LGBT people. The Daily Dot. Retrieved September 9, 2016 from http://www.dailydot.com/via/bioware-dragon-age-inquisition-gaming-lgbt/

Kelly, P. (2014). Approaching the Digital Courting Process in Dragon Age 2. In Enevold, J., MacCallum-Stewart, E. (eds) Game Love: Essays on Play and Affection (pp. 46-62). Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Incorporated Publishers,

Kies, B. (2015). Death by Scissors: Gay Fighter Supreme and the sexuality that isn’t sexual. In Wysocki, M. and Lauteria, E. (eds.), Rated M for Mature Sex and Sexuality in Video Games (pp. 210-224). London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Lamb, P. and Veil, D. (1986). Romantic Myth, Transcendence, and Star Trek Zines. In Palumbo, D. (ed) Erotic Universe: Sexuality and Fantastic Literature (pp. 235-272). New York: Greenwood Press.

Leow, H. (2011). Subverting the Canon in Feminist Fan Fiction: 'Concession'. Transformative Works and Cultures, 7. Retrieved June 27, 2016 from http://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/286/236

McCormick, J. (2016). The story behind Tom of Finland is to hit the big screen. Pink News. Retrieved June 11, 2016 from http://www.pinknews.co.uk/2016/02/11/the-story-behind-tom-of-finland-is-to-hit-the-big-screen/

Mercer, J. (2003). Homosexual Prototypes: Repetition and the Construction of the Generic in the Iconography of Gay Pornography. Paragraph, 26 (1-2), 280-290.

Mitchell, R. and Ellis, A. (2010). In the Eye of the Beholder: Knowledge that a Man is Gay Promotes American College Students’ Attributions of Cross-Gender Characteristics. Sexuality & Culture, 15, 80-99.

Montgomery, K. (1981). Gay activists and the networks. Journal of communication, 31 (3), 49-57.

Moritz, M. (1989). American television discovers gay women: The changing context of programming decisions at the networks. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 13 (2), 62-78.

Mulcahy, T. (2013). The Gaying of Video Games. Slate. Retrieved June 13, 2016 from http://www.slate.com/blogs/outward/2013/11/12/video_games_embrace_gay_romance_from_the_ballad_of_gay_tony_to_the_last.html

MundaneMatt (2014). Dorian the Redeemer is Gay in DRAGON AGE: INQUISITION… does anyone care? YouTube. Retrieved September 29, 2017 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jnFyn5lZF3I

Owens, E. (2015). Straight Women, Gay Men Are Friends, Not Accessories. Huffington Post. Retrieved June 13, 2016 from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/ernest-owens/straight-women-gay-men-ar_1_b_6427780.html

Pellegrini, N. (2017). FanFiction.Net vs. Archive of Our Own. LetterPile. Retrieved May 9, 2017 from https://letterpile.com/writing/fanfictionnet-vs-archive-of-our-own

Perkins, T.E. (1979). Rethinking Stereotypes. In Barrett, M.; Corrigan, P.; Kuhn, A.; Wolff, J. (eds), Ideology and Cultural Production (pp. 135-159). London: Croom Helm.

Popova, M. (2018). ‘Dogfuck rapeworld’: Omegaverse fanfiction as a critical tool in analyzing the impact of social power structures on intimate relationships and sexual consent. Porn Studies.

Richardson, N. (2012). Fashionable ‘fags’ and stylish ‘sissies’: The representation of Stanford in Sex and the City and Nigel in The Devil Wears Prada. Film Fashion and Consumption, 1 (2), 137-157.

Savin-Williams, R.C. (2005). The New gay teen: Shunning labels. Gay and Lesbian Review, 12, 16-19.

Shaw, A. (2009). Putting the Gay in Games: Cultural Production and GLBT Content in Video Games. Game and Culture, 4 (3), 228-253.

Sinfield, A. (1994). The Wilde Century: Effeminacy Oscar Wilde and the queer moment. New York: Columbia University Press.

Sinfield, A. (1997). Identity and Subculture. In Medhurst, A. and Munt, S. (eds), Gay and Lesbian studies (pp. 201-214). London: Cassell.

Sinfield, A. (1998). Gay and After. London: Serpent’s Tail.

Sliwinski, A. (2009). BioWare’s Old Republic policy on homosexuality reconsidered. Engadget. Retrieved June 14, 2016 from https://www.engadget.com/2009/04/29/biowares-old-republic-policy-on-homosexuality-reconsidered/

Theora (2016). The Evolution of LGBT+ Representation in Dragon Age. Fandom Following. Retrieved September 2, 2016 from http://www.fandomfollowing.com/the-evolution-of-lgbt-representation-in-dragon-age/

Thurlow, C. (2001). Naming the ‘outsider within’: Homophobic pejoratives and the verbal abuse of lesbian, gay and bisexual high-school pupils. Journal of Adolescence, 24, 25-38.

Tosenberger, C. (2008). The epic love story of Sam and Dean’: Supernatural, queer readings, and the romance of incestuous fan fiction. Transformative Worlds and Cultures, 1. Retrieved June 28, 2016 from http://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/30/36

Waern, A. (2014). "I’m in love with someone that doesn’t exist!": Bleed in the Context of a Computer Game. In Enevold, J., MacCallum-Stewart, E. (eds) Game Love: Essays on Play and Affection (pp. 25-45). Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Incorporated Publishers,

Warner, M. (1993). Introduction. In Warner, M. (ed) Fear of a Queer Planet: Queer Politics and Social Theory (pp. 7-31). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Westrate, N. and McLean, K. (2010). The rise and fall of gay: A cultural-historical approach to gay identity development. Memory, 18 (2), 225-240.

Williams, C.; Giuffre, P.; Dellinger, K. (2009). The Gay-Friendly Closet. Sexuality Research & Social Policy: Journal of NSRC, 6 (1), 29-45.

Woledge, E. (2005). From slash to the mainstream: Female writers and gender blending men. Extrapolation, 46, 50–66.

Yatrakis, C. (2013). Fan fictions, fandoms, and literature: or, why it’s time to pay attention to fan fiction. Thesis (Master) DePaul University.

Zekany, E. (2015). "A Horrible Interspecies Awkwardness Thing": (Non)Human Desire in the Mass Effect Universe. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 1-11.

Ludography

BioWare (2011) Star Wars: The Old Republic. LucasArts, Electronic Arts.

BioWare (2011) Dragon Age 2. Electronic Arts.

BioWare (2014) Dragon Age: Inquisition. Electronic Arts.

Forum Comments

Bioware.com (2015). As much as I love Dorian…. Bioware.com. Retrieved March 14, 2018 from https://web.archive.org/web/20160806170234/http://forum.bioware.com/topic/541514-as-much-as-i-love-dorian/

Gamefaqs.com (2014). How can someone NOT romance Dorian? Retrieved June 15, 2016 from http://www.gamefaqs.com/boards/718650-dragon-age-inquisition/70658741

Gamefaqs.com (2015). Does Dorian look like Freddy Mercury to anybody else? Retrieved June 15, 2016 from http://www.gamefaqs.com/boards/718650-dragon-age-inquisition/71407167

Gamefaqs.com (2014). Why the straight male romance option suck? Retrieved December 11, 2017 from http://www.gamefaqs.com/boards/718650-dragon-age-inquisition/70683140

Giantbomb.com (2015). How do you feel about Dorian Pavus’ Homosexuality? Retrieved June 15, 2016 from http://www.giantbomb.com/forums/dragon-age-inquisition-7175/how-do-you-feel-about-dorian-pavus-homosexuality-1760189/

The Escapist (2014). Dragon Age Inquisition players: How do you feel Bioware handled Dorian’s sexual orientation? Retrieved June 15, 2016 from http://www.escapistmagazine.com/forums/read/9.867487-Dragon-Age-Inquistion-players-How-do-you-feel-Bioware-handled-Dorian-s-sexual-orientation

Reddit (2015). So how many straight males romanced Dorian? Retrieved June 15, 2016 from https://www.reddit.com/r/dragonage/comments/2nd5i6/so_how_many_other_straight_males_romanced_dorian/