Beyond the French Touch: The Contestataire Moment in French Adventure Digital Games (1984-1990)

by Filip JankowskiAbstract

This article attempts to suggest a revision of the historical aesthetic category frequently called the “French Touch.” Proving that this category has become blurred nowadays, the author suggests a more nuanced approach to French digital game history. The article focuses on games that matched the contestataire moment in the history of France. Instead of producing science fiction and fantasy themes, three examined development circles (Froggy Software, Cobra Soft and François Coulon), active at a similar time, followed journalist Guy Delcourt’s advice to make games rooted in the current reality. Their adventure games, inventive both formally and in terms of the topics covered, responded vividly to sociopolitical events. Froggy Software, led by Jean-Louis Le Breton, directly captured the May 1968 countercultural spirit. Cobra Soft, directed by Bertrand Brocard, took a revisionist approach to World War II and its aftermath. Finally, François Coulon experimented with ludic means of expression while focusing on the parody of contemporary events. Thus, the creative output of these development circles shows that the French digital game field escapes the categorization attributed to the concept of “French Touch.”

Keywords: Counterculture, French Touch, French video games, video game history, adventure games

Introduction

How does one define French digital game aesthetics? The so-called “French Touch” category served as a crucial yet vague response to that question. Indeed, French Touch contributed to shaping digital games’ status as a form of art--which in fact did happen in France (Dauncey, 2012). However, this article implies that this category should be nuanced. Because the numerous theoreticians who coined the French Touch category focused on the 1980s and 1990s as its defining moment, this period--not the movement--has importance in French gaming history. Nevertheless, I would like to show the blind spots which scholars beyond the French Touch seem to miss: first, to indicate the countercultural and revolutionary origins of the national industry’s renaissance, and second, to more adequately signal that adventure games with real-life settings had an essential impact on the French gaming industry between the decades mentioned above.

Background

In the mid-1990s, Anglo-Saxon writers coined the term “French Touch” to describe the idiosyncrasies of French digital games (Brown, 1996; Squires, 1992). It was explained first as a “cinematic look and approach to story-telling” (Brown, 1996, p. 9), but French journalists and scholars overused this term. Moreover, there are still complaints about its actual meaning and scope. Serge Dupuy-Fromy (2012, pp. 190-191) indicated innovation and technological mastery as its main factors. Alexis Blanchet supported this view at first, naming creators from Muriel Tramis to Michel Ancel as the movement’s members. According to Blanchet, the French Touch lasted from 1987 to 1995 and encompassed only science fiction and fantasy games (Blanchet, 2015, p. 184).

This notion contradicted what Tristan Donovan (2010) and Hugo Labrande (2011) had settled. According to them, the French Touch lasted through the late 1980s. Crucially, Donovan and Labrande believed the French Touch consisted of only 1980s games. To them, “strong narratives” and real-life settings were the movement’s primary means of expression (Donovan, 2010, p. 128), with Jean-Louis Le Breton branded as its godfather (Labrande, 2011, p. 412).

The French-press discourse after 2010 did not improve the situation either. Ubisoft Montpellier, Arkane Studios and Quantic Dream’s worldwide triumphs spurred journalists to reuse the term (Grallet et al., 2013; “La French Touch Des Jeux Vidéo,” 2011). Paradoxically, the French Touch became even more blurred as a movement.

Nowadays, French Touch has been abandoned. Admittedly, Therrien et al. (2021) tried to define this category via the historical-analytical comparative system. Their findings state that neither a specific setting nor date determines the movement’s aesthetics. Instead, elaborated interfaces and genre mixtures are crucial for the “French Touch.” However, the research results by Therrien et al. scarcely define the proposed movement’s scope. There are giant aesthetic and technological leaps between games like Le Vampire Fou (Le Breton, 1983) and Heavy Rain (Quantic Dream, 2010). The first one is a first-person black-and-white graphic adventure manned with a text parser, and the second one is a third-person adventure game ostentatiously imitating mainstream Hollywood movies. Therrien et al. (2021) attempt to reconcile games 30 years apart. In the meantime, Blanchet, along with Guillaume Montagnon and Sebastien Genvo, abandoned the problematic phrase French Touch in favour of “French adventure games” [jeu d'aventure à la française] (Blanchet & Montagnon, 2020, pp. 327-350). Thus, Therrien et al.’s (2021) efforts to reconstitute the French Touch hardly defend the term.

Still, Blanchet & Montagnon (2020) claim the period between 1982 and 1990 as the French digital gaming industry’s defining moment. They underline that many French games discussed political topics within this period (Blanchet & Montagnon, 2020, pp. 335-344). This article suggests following the Blanchet & Montagnon’s findings and pointing out a specific “contestataire moment” in French gaming historiography which the French Touch founders seem to miss. With no ambition to define the French gaming industry in all of its complexities, the paper implies focusing on a narrow period in French digital game history, more rooted in the domestic reality.

The research below concentrates on so-called “adventure games.” Veli-Matti Karhulahti defines the latter as “story-driven video games, which encourage exploration and puzzle solving and always have at least one player character… based on object manipulation and spatial navigation” (Karhulahti, 2011, p. 73). The genre choice was made after Donovan (2010), Labrande (2013) and Cyrille Baron (2019). According to them, French adventure games in the 1980s were especially innovative and attached to reality, compared to other ludic genres (Baron, 2019, pp. 24-25; Donovan, 2010, p. 130; Labrande, 2013, pp. 411).

Likewise, I borrow the French term contestataire as referring to the 1960s social movements in Western Europe and the United States, known also as the “counterculture” (Munck, 2007, p. 20). These movements attempted to overturn the violence-based social order (hidden behind the facade of democratic systems), where consumption increased, and technology dominated human life. Here, the links between anti-technological movements and digital games may sound paradoxical. Nevertheless, contestants spread revolutionary ideas using digital technologies (see Medina, 2011; Turner, 2006), and the counterculture in the 1980s moved from street barricades to computers.

Methodology

I restricted the research scope of this investigation using the following premises:

- The “here and now” premise: While there is no denying that a large part of French games constituted those with science fiction and fantasy settings, there were also numerous games related to real-life sociopolitical events in France. Therefore, I sought for games which would express the authors’ stance towards the present. This meant shelving the software linked to fantasy, science fiction or horror settings. This premise would exclude retrospective historical games such as Les passagers du vent (Infogrames, 1986) and Le Manoir de Mortevielle (Lankhor, 1987), but also generally escapist SF games such as L’Arche du Capitaine Blood (Exxos, 1987) and Another World (Delphine Software, 1991). Although L’Arche du Capitaine Blood’s co-writer, Philippe Ulrich, was known for his contestatory happenings, his games did not refer directly to France’s actual events; Ulrich’s project would rather represent a futuristic counterculture.

- The formal premise. The research would also encompass games featuring mechanical or technological experiments. Those could include hybrid mechanics which Therrien et al. (2020) mentioned. Whereas in other cultural forms of expression (e.g., films) opposing the so-called mainstream is not hard to achieve, counter-cultural digital games may differ from the mainstream only mechanically, through innovation or creativity (Jahn-Sudmann, 2008).

Based on those premises, I inspected three leading development circles: Froggy Software, Cobra Soft and François Coulon’s works. Those three circles were active between circa 1984 and 1990. Froggy Software, founded in 1984 by Jean-Louis Le Breton and Fabrice Gille, ceased producing games in 1987. Meanwhile, however, Froggy Software managed to produce more than a dozen games (Le Breton, n.d.-a). Likewise, Cobra Soft, created in 1984 by Bertrand Brocard and Gilles Bertin, kept developing games until emerging national industry giant Infogrames bought Cobra in 1987, only to neutralize it in 1990 (Hoagie, 2019). Coulon--not associated with any permanent developer--also programmed his first games in 1985. Yet, when Bill Palmer (Arcan, 1987) flopped, Coulon would stay inactive until L'Égérie (Les Logiciels d’en Face, 1990) was released. Thus, the release of L'Égérie, which combines a digital game and graphical hypertext, symbolically ends the contestataire moment within the French digital game field which I would like to explore.

Table 1 shows 12 selected games, examined and listed.

|

Development circle |

Canonical games |

|

Froggy Software |

Paranoïak (Froggy Software, 1984), Le Crime du parking (Froggy Software, 1985a), Le Mur de Berlin va sauter (Froggy Software, 1985b), Même les pommes de terre ont des yeux (Froggy Software, 1985c), La Femme qui ne supportait pas les ordinateurs (Froggy Software, 1986a), Baratin blues (Froggy Software, 1986b) |

|

Cobra Soft |

Meurtre à grande vitesse (Cobra Soft, 1984), Dossier G: L’Affaire Rainbow Warrior (Cobra Soft, 1986), Meurtres en série (Cobra Soft, 1987), Meurtres à Venise (Cobra Soft, 1988) |

|

François Coulon |

Hawaii (Excalibur, 1986), L'Égérie (Les Logiciels d’en Face, 1990) |

Table 1: List of examined games

The games listed above were played and analyzed in terms of two factors, corresponding to formerly stated premises:

- Intertextual references. Here, the paper refers to Gérard Genette’s understanding of intertextuality. Genette indicates intertextual references as a “relationship of co-presences between two texts or among several other texts” (Genette, 1997, p. 1). Genette cites quoting, plagiarism and allusion as three examples of intertextuality. However, intertextual references are here understood as unrestricted to literary or cinematic fiction, and they include political news and faits divers. This factor serves to verify the “here and now” premise.

- Formal experiments (in terms of game mechanics). The paper refers to Miguel Sicart’s definition of game mechanics as “methods invoked by agents, designed for interaction with the game state” (Sicart, 2008). In other words, game mechanics “control what any agent, especially the player, can or cannot do with the game world, thereby determining what the player will experience” (Roe & Mitchell, 2019, p. 2). Thus, the paper also shows how the player’s experience was expanded in the games mentioned above. This factor serves to verify the formal premise.

Historical Context

After 1982, when the worldwide console and arcade-game market declined because of the infamous crash that occurred during this year, the personal-computer industry in France grew considerably. Such growth was enormously important for the local digital-game culture. On the one hand, console games and slot machines were condemned in the national press (Lacan & Spitz, 1984), and the production of arcade machines declined as a result of government regulations (Charreyron, 1986). On the other hand, President François Mitterrand, in his first years of governing France, placed particular emphasis on computerization and programming-skills education as essential factors for building a new IT sector (Cole, 1999). Personal computers were multi-functional, which made them ideal tools for both work and creative programming, and consequently for creating games. Some home-grown programmers established development studios. However, French software houses limited their activity at first to copying American and Japanese arcade hits (Delcourt, 1984).

This situation prompted Guy Delcourt, a journalist writing for Tilt magazine, to write an elaborate article titled La puce aux œufs d’or (The Golden Egg Chip). Published in August 1984, the article constructively criticized the state of the French digital-gaming industry. Delcourt encouraged game developers in his reportage to end the creative stagnation in two ways: by “getting involved in the adventure [lancer dans l’aventure]” (Delcourt, 1984, p. 16) and taking inspiration from the real-life environment: “So prepare yourself for the challenge. Try to look for personal ideas, new initiatives, original themes that you can draw--here is a free hint--from the news” [Essayez de trouver des idées personnelles, des démarches nouvelles, des thèmes inédits que vous pouvez par exemple puiser -- c’est un tuyau gratuit -- dans l’actualité] (Delcourt, 1984, p. 18).

Although it is debatable whether Delcourt’s advice actually inspired specific game developers, his article came at a special moment. Firstly, the phrase mentioned before--lancer dans l’aventure--would not only mean “getting involved in the adventure” but also making adventure games, known in French as l’aventures. Indeed, after 1984, the number of adventure games in France rose rapidly (Donovan, 2010, p. 128). Secondly, Delcourt’s postulate to borrow inspiration from current events and politics became the postulate of the emerging development studio Froggy Software.

The contestataire moment

Froggy Software

To justify using the term contestataire for the reality other than May 1968, I need to refer to Jean-Louis Le Breton’s presence. Le Breton was a member of May 1968 student protests in Paris, where he lived. As he reminisced in an interview with Donovan, this failed revolution “was both a period of political consciousness and of utopia. We used to mix flower power with throwing cobblestones at policemen” (Donovan, 2010, p. 125). Le Breton continued his flirtation with contestation, joining two musician groups: Los Gonococcos and Dicotyledon. Having quit Los Gonococcos in 1982, Le Breton exchanged his synthesizer with an Apple II computer. He programmed probably the first French-language graphic adventure game, Le Vampire Fou (Le Breton, 1983), released by the ephemeral software house Ciel Bleu. Despite Le Vampire Fou’s commercial failure, Le Breton still enjoyed creating games. He joined forces with his friend Fabrice Gille and created Froggy Software in 1984, a company intended to release games rooted in the May 1968 spirit from the beginning. As Le Breton said, “May 1968 surely had an influence on the way we started the company… Humour, politics and new technologies seemed to be an interesting way to spread our state of mind” (Donovan, 2010, p. 126).

Indeed, politics were present in numerous digital games that came from Froggy Software. Paranoïak, Froggy Software’s flagship title that received a Pomme d’Or award (“Pomme d’Or télématique,” 1985), broke with the SF and fantasy themes attributed to digital games in 1984. Set in an unknown contemporary French locality, Le Breton and Gille’s game allows for steering a male avatar suffering from multiple diseases, symptoms, or complexes. Remedies are comically peculiar. For example, curing the avatar of vertigo requires typing “grimper sur un fauteuil et sauter [climb on a chair and jump]” during the séance of Blade Runner. This action is positively valued in the game, although it would typically outrage the audience in non-virtual cinemas. However, Paranoïak fits into the May 1968 postulate that cinema, regarded by Marxist critics such as Henri Lefebvre as the passive medium propagating bourgeois ideology, should be reinvented (Lefebvre, 1958, p. 18). Meaningfully, typing the command “regarder la télé [watch TV]” in the avatar’s room made the health score decrease. Thus, Paranoïak procedurally discourages players from what Guy Debord (1970) considered as spectacle, the passive consumption of moving images.

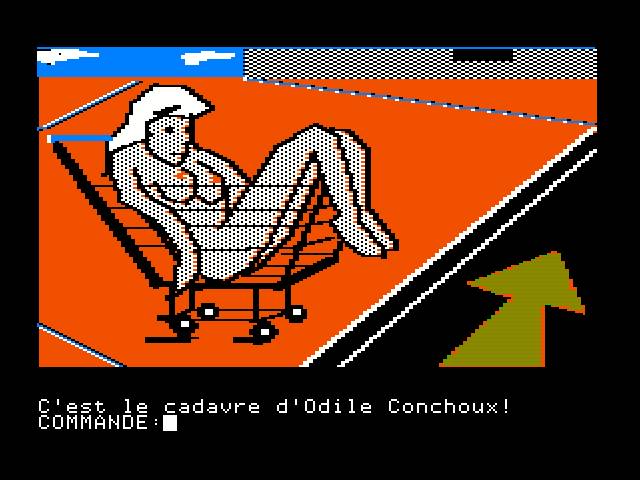

Another Froggy Software title, Le Crime du parking, introduced such themes as homosexuality and drug use to digital games. The player investigates the death of a young woman Odile Conchoux, having found her naked body left in the parking lot (Figure 1). The game’s early stage resembles the dark fantasy comic book Odile et les crocodiles (Montellier, 1984), whose titular female protagonist is raped by crocodiles in the parking lot. [1] The rest of Le Crime establishes the foundations for further French mystery games. The game involves interrogating several suspects and finding new clues, and its game mechanics were comparable at its release time only to the American Déjà Vu (ICOM Simulations, 1985). Le Crime du parking was the most successful of Froggy Software’s games, selling around 1,600 copies (Blanchet & Montagnon, 2020, p. 336).

Figure 1: A screenshot from Le Crime du parking (Froggy Software, 1985). Source: Froggy Software, under permission of Jean-Louis Le Breton.

Tristan Cazenave, a future professor at the Université Paris-Dauphine, was responsible for two other Froggy Software titles. Le Mur de Berlin va sauter, set in West Germany during the Cold War, was no less innovative than Le Breton and Gille’s games. The player has to contain a left-wing terrorist named Carlus [2] from destroying the Berlin Wall. Although Le Mur de Berlin’s political criticism was juvenile (Lebelle, 2005), its rhetoric of failure stood out at the time. The player may fail frequently: for example, she can get beaten by a policeman or killed by a Soviet agent in a public bath. Even the “positive” ending is apocalyptic, as the player cannot prevent Carlus’s terrorist attack regardless of her efforts. The game concludes with the United States’ response to the attack: bombarding the Soviet bloc with intercontinental ballistic missiles.

Pascal Labrevois and François Lamoureux programmed, in turn, Baratin blues. Its action occurs in Paris and Saint-Tropez, with the player having to prevent a biological poison attack on the Parisian sewers. Not coincidentally, the game mocked the actions of the conservative politician Jacques Chirac, the Mayor of Paris at the time, who planned to privatize companies supplying drinking water to Paris (Ambroise-Rendu, 1986). Likewise, Baratin blues indicates that instead of privatization, Chirac should focus on renationalization. Baratin blues’ visual content includes two Coca-Cola advertisements. Thus, because Froggy Software’s art-house profile precluded promoting Coke, Labrevois and Lamoureux’s game would more veraciously indicate that Parisians’ real poisoner is the American corporation.

Countercultural tropes also appeared in Froggy Software’s female-developed games, Même les pommes de terre ont des yeux and La Femme qui ne supportait les ordinateurs. Même les pommes’ author Clotilde Marion was among the first females in the French digital-game industry. As Marion claimed in one interview, she invented the script for Même les pommes de terre after peeling potatoes and thinking of South-American dictatorships (Marion, 1986). Not incidentally, Marion’s game targeted especially Augusto Pinochet’s violent military junta in Chile (Blanchet & Montagnon, 2020, p. 343). Thus, the player has to abolish the junta and reestablish democratic rule in a virtual South-American country. Here, the renowned Costa-Gavras film Missing (Costa-Gavras, 1982) probably shaped Marion’s imagination, because both media shared an image of a Chilean stadium filled with political prisoners. Même les pommes de terre also features a joke copied by subsequent French game developers (Blanchet & Montagnon, 2020, p. 337). If the player writes insults to the parser, the game immediately stops. Then, a general’s horrid face appears with the following words: “Demandez pardon à genoux” [Ask for forgiveness on your knees]. Only writing “pardon à genoux” allows for continuing the game session.

However, La Femme remains Froggy’s most countercultural game, mainly because of its self-referential qualities. La Femme’s user impersonates a female character who becomes aggressively seduced during a chat within Calvados (a then-popular French network). The avatar’s two seducers are cyberbullies; a self-reflective computer named Ordine [sic!] rivals a human hacker Comby, but they both threaten the female avatar’s life. Here, La Femme’s creator, Chine Lanzmann, encapsulated her own experience of moderating an actual discussion group within Calvados. Furthermore, several of Froggy’s members, like Le Breton (“Pepe Louis”), Gille (“Faby”) and Lanzmann (“Chine”) herself, make a cameo appearance. [3]

Interestingly, Lanzmann used only the text interface to make the game’s environment resemble the Calvados interface. Moreover, she made an elaborate script where non-player characters’ utterances look improvised (with grammatical errors) and end with questions. When the player writes “oui” or “non” to those questions, different paths during each session are activated, and the choices lead to six different endings. Nevertheless, La Femme’s conclusion is similar regardless of the choices made: that women, with their identities revealed, cannot easily survive in the male-dominated Internet realm.

Cobra Soft

Cobra Soft, a software house founded by Bertrand Brocard and Gilles Bertin, also released several games with countercultural overtones. Cobra Soft rose from the computer shop ARG Informatique, whose owner was Brocard. Having experimented with computer programming, Brocard changed the brand’s name to Cobra Soft, which to him sounded “a little more aggressive” (Blanchet & Montagnon, 2020, p. 214). Thus began his adventure designing and releasing games in the BASIC programming language. Inspiration for his productions came from cinema; his mother worked as a script girl, and Brocard had an 8 mm camera (Brocard, 2016, p. 1). Yet, Brocard favoured making video games because “I could tell stories, I could be the director, the technician, the decorator, in short I could do it all” [Je pouvais raconter des histoires, je pouvais être à la fois un metteur en scène, le technicien, le décorateur, bref je pouvais tout faire] (Brocard, 2016, p. 1). Therefore, his activity in the French digital game industry was part of Brocard’s expression.

Brocard became known for a five-part mystery game series called Meurtres, of which only three installments--Meurtre à grande vitesse, Meurtres en série and Meurtres à Venise--were set in Brocard’s present reality. [4] However, their elaborate plots proved Brocard’s deep interest in history and politics. Brocard’s careful research preceded making the intrigues of each mentioned game. For example, to make Meurtres en série credible, Cobra Soft’s co-founder traveled to the Sark island near Normandy to study its topography and interview its inhabitants (Brocard, 1986a). Brocard claimed, “I work a lot on the basis of reality; it shows in the games” [Je travaille beaucoup à partir de la réalité, cela se sent dans les jeux] (Brocard, 1986b).

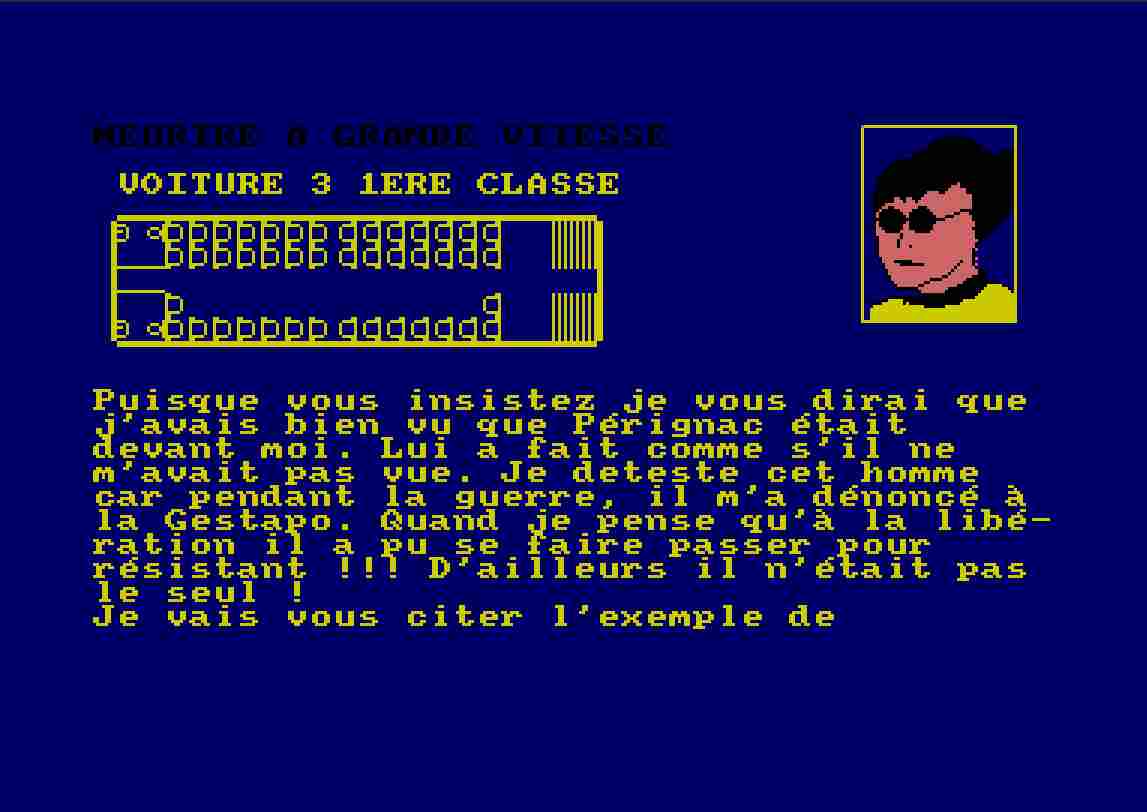

Three mentioned parts of the Meurtres’ series reference World War II and its aftermath in Europe. Much more successful than Froggy’s games, [5] Meurtre à grande vitesse allows the player to determine who murdered fictional radical senator Albert Pérignac during a train journey from Marseilles to Paris. Among the passengers, one can find a female war survivor whom Pérignac had denounced to Gestapo (Figure 2). In turn, Meurtres en série is a race-against-time investigation of the serial murder on the island of Sark near Normandy. As it turns out, former German officers and soldiers commit numerous murders to retrieve a precious treasure buried by them before the German forces’ capitulation in France in 1944. Finally, Meurtres à Venise focuses on smashing the left-wing terrorist group Fraction Ulrika, [6] whose members plan to detonate a bomb and sow chaos in heart of Venice. The inquiry proves that Fraction Ulrika tried to attack a far-right Italian Masons’ lodge in Venice; [7] a police chief, who commissions the inquiry to the player, is among the lodge’s members.

Figure 2: A screenshot from Meurtre à grande vitesse (Cobra Soft, 1985). Source: Conservatoire National du Jeu Vidéo, under permission of Bertrand Brocard.

The selected Meurtres games deserve attention because of their specific handling. Especially Meurtre à grande vitesse importantly shows how Brocard as its designer fought technological constraints. The game was programmed for computers with merely 48 kilobytes of memory, so clues and illustrations that would help find the killer could not be included in the game (Blanchet & Montagnon, 2020, p. 215). Instead, Brocard added printed clues to the game boxes. During the in-game train sweep, the player can display object lists in the game’s various locations. When the lists include objects named with asterisks, the player can reach for the objects’ physical counterparts, which help in further investigation. Meurtres en série and Meurtres à Venise, also designed by Brocard but programmed by Bertin, include physical clues, too. However, those two games feature more digital illustrations than MGV, thanks to the more advanced gaming platforms they were built for.

However, Brocard was uninvolved in Cobra Soft’s most directly political title. In 1986, the company released Dossier G, Daniel Lefèbvre’s unprecedented documentary game about France’s most significant political scandal of the 1980s. In 1985, Greenpeace’s Rainbow Warrior ship, whose crew protested French nuclear tests in the Tahiti archipelago, was sunk by the French left-wing government’s commission (Laroche-Signorile, 2015). The game contains multiple modes. For example, the player can shape events in a “choose your own adventure” manner, read the authorial statement on the affair or even fill in a virtual questionnaire and compare her own statements with official polls.

François Coulon

Dossier G’s criticism of the Rainbow Warrior affair was echoed in François Coulon’s Hawaii. Coulon, whose two early works (Dossier Palmer, Hawaii) were illustrated by Cyrille Vanoye, imitated Froggy’s style at first. While Dossier Palmer, with its interface identical to Paranoïak, also drew inspiration from actual events, [8] it retained Coulon’s stylistic exercise and brought nothing especially original to digital adventure games.

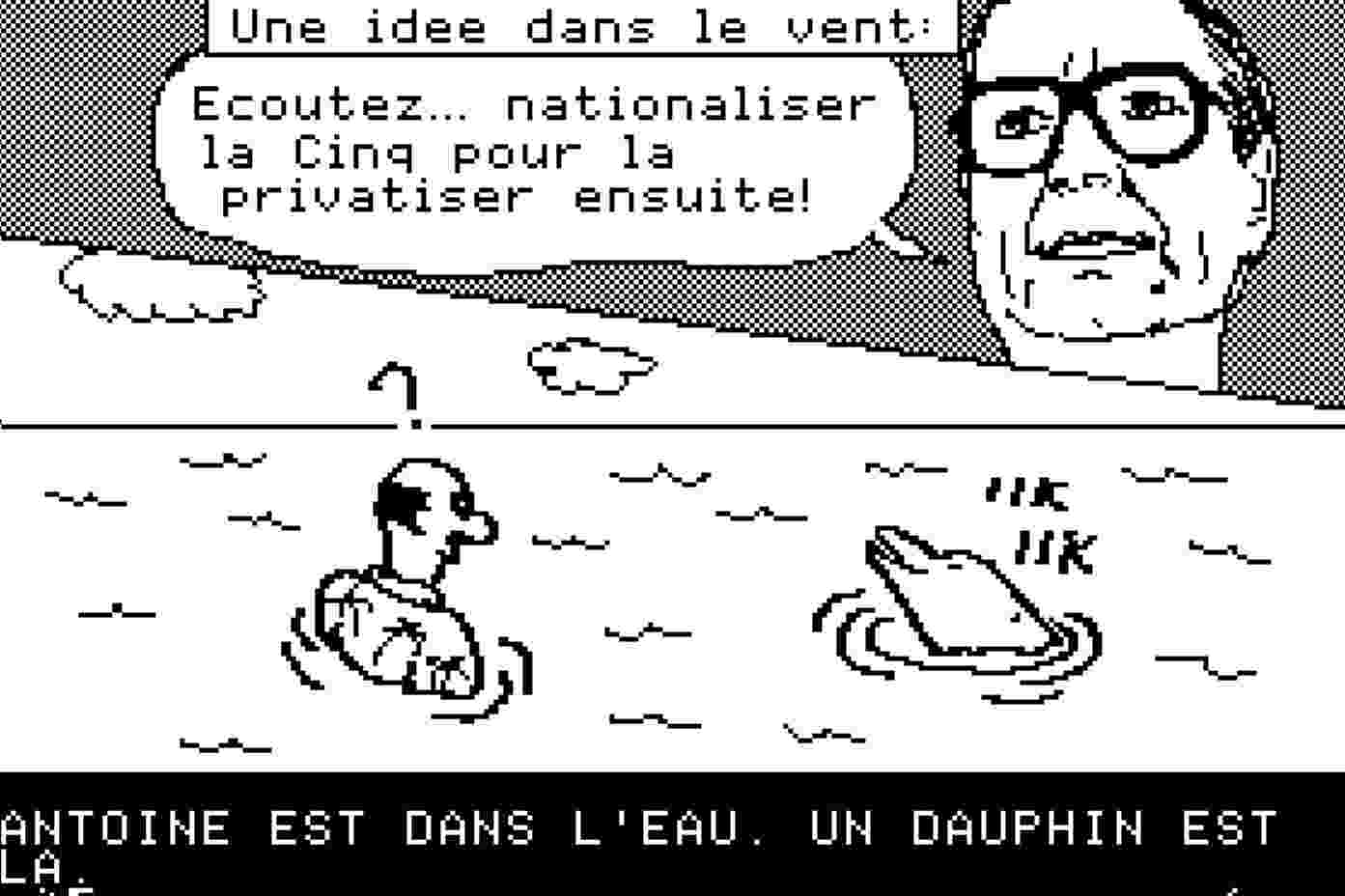

Hawaii is another matter. In this contestataire satirical game, the player steers a burn-out corporation employee who flees from his workplace and tries to reach the titular American state. However, Hawaii’s plot is just a pretext for mockeries directed at the whole French political class. On the one hand, Hawaii attacks the political left just like Dossier G, depicting nuclear tests in Tahiti and sinking Rainbow Warrior, for which then-governing president François Mitterrand was responsible. On the other hand, jokes also reach right-wing politicians such as Jean-Marie Le Pen and Jacques Chirac. For example, Le Pen, who led the far-right National Front, is parodied in billboards such as “Le Pen washes you whiter” [Le Pen lave plus blanc] [9] and “Help! The right wing is coming back” [Au secours! La droite revient]. Chirac, whose conservative party Rally for the Republic won the parliamentary elections in 1986, appears in the game’s penultimate level, delivering an apocalyptic speech (Figure 3): “Listen… Let us nationalize Cinq and then privatize it” [Écoutez… nationaliser la Cinq pour la privatiser ensuite!]. [10]

Figure 3: A screenshot from Hawaii (Excalibur, 1986). Source: Excalibur, under permission of François Coulon.

Coulon and Vanoye used chaotic aesthetics to capture the equally destructive political chaos in France. Surfeit dominates almost every screen of Hawaii, where the illustrations intertwine with authorial comments, jokes or citations from other media. Crude caricatures interchange with carefully digitized images that depict celebrities like Rika Zarai and Pierre Bellemare. Hawaii’s satirical content was so cruel that several mainstream gaming magazines condemned the game (Deconchat, 1987; “News: Hawaii,” 1987).

When Coulon finished his other work, an Indiana Jones franchise parody Bill Palmer (Arcan, 1987), he prepared for an even more radical experiment. Made after a three-year gap spent on writing for gaming magazines, L’Égérie was Coulon’s pioneering graphical hypertext. Illustrated by Laurent Cotton, L’Égérie is devoted to Parisian girl Amandine Palmer.

The software allows the user to shape Palmer’s fate, actuating subtle procedural rhetoric (see Bogost, 2007). Each screen contains several clickable objects or characters. Instead of typing commands or collecting items, the player needs only to click them. Depending on how the user interacts with the game’s graphical content, L’Égérie executes different variants on Palmer’s life. The girl can become a journalist, a cosmetician, or an addict; she can have an affair with her female fellow or end in bed with one of the encountered males. The algorithms that run L’Égérie are not necessarily straightforward. Nevertheless, the software procedurally emphasizes a certain quality of human fate: haphazard. Besides this fact of life, L’Égérie delivers a polysemous authorial portrayal of Parisians’ contemporary existence (i.e., long queues to the public laundry or city bus rides). Thus, L’Égérie construes the biographical bridge between Coulon’s juvenile digital games and his more mature, non-ludic hypertexts.

Discussion

The research results suggest that the term French Touch is outdated. Here, I advocate a revision of French game history. The examined games are not linked to science fiction or fantasy, as Blanchet (2015) stated. Nor they use the cinematic means of expression, regardless of what Dupuy-Fromy said about French Touch. With their explicitly political content, the 1980s contestataire adventure games from France are closer to such phenomena as British Surrealism (Donovan, 2010) and Czechoslovak games made under the Iron Curtain (Švelch, 2018). This coincidental convergence also shows the association between 1980s digital adventure games and countercultural communities.

One thing is certain. Despite goodwill attempts to define such a holistic category as French Touch, we should treat this category as suspicious and unable to capture the French digital game aesthetics overall.

Endnotes

[1] Le Breton may have known Montellier’s book because he admired bandes dessinées. In the 1970s, he worked in L’œil du Futur, a bookstore where he exposed, for example, comic books by Philippe Druillet and Jean-Pierre Dionnet, who were the co-editors of the famous underground magazine Métal Hurlant (Le Breton, n.d.-b).

[2] He was modelled after Carlos the Jackal, far-left activist known for numerous terrorist crimes in Western Europe, including France (Riding, 1994).

[3] Information settled after an email discussion with Hugo Labrande (personal communication 2020). See also the source code of La Femme’s port to I6, made by Labrande himself (Labrande, 2007).

[4] Meurtres sur l’Atlantique (1985) is set in 1938, whereas Murders in Space (1990) takes place in a futuristic spaceship.

[5] MGV sold 20,000 copies, according to Brocard’s estimates (Brocard, 1986).

[6] Modelled after the actual German terrorist group, whose cofounder was Ulrike Meinhof. Her ludic counterpart in Meurtres à Venise is named Ulrika Zaroff.

[7] The source of inspiration came from Propaganda Due, an actual far-right lodge in Italy. Supported by the CIA, the real-life Propaganda Due aimed to restore authoritarian rules in Italy or at least to prevent left-wing parties from seizing power there (Ganser, 2006, p. 776). Among Propaganda Due’s members was Silvio Berlusconi (Eco, 2016, para. 26.35; Lollo, 2016, p. 65).

[8] On 26 November 1983, British criminal Bill Palmer and his five partners robbed the Brink’s-Mat department store. The losses suffered as a result of the robbery were estimated at £26 million. Palmer himself, having fled to Spain in 1985, managed to avoid a police raid (Steele, 2001; Vasagar & Hopkins, 2001).

[9] A parody of Persil’s popular French advertisement and its slogan “Persil lave plus blanc”.

[10] Having taken office, Chirac nationalized the private television channel La Cinq, for which the former left-wing cabinet of Laurent Fabius had previously granted a license. Then, Chirac immediately sold the channel to the company Socpresse, responsible for releasing the conservative daily Le Figaro (Kuhn, 2011, pp. 22, 63).

References

Ambroise-Rendu, M. (1986). M. Chirac confie à une société d’économie mixte l’alimentation en eau de Paris [Mr. Chirac entrusts a semi-public company with the supply of water to Paris]. Le Monde. http://archive.is/7YZrO

Arcan (1987). Bill Palmer [Atari ST]. Digital game directed by François Coulon, published by Arcan.

Baron, C. (2019). Les jeux d’aventure en pixels [Adventure games in pixels]. [Place of publication not identified]: Geeks Line.

Blanchet, A. (2015). France. In M. J. P. Wolf (Ed.), Video games around the world (pp. 175-192). Cambridge-London: MIT Press.

Blanchet, A., & Montagnon, G. (2020). Une histoire du jeu vidéo en France: 1960-1991: Des labos aux chambres d’ados [A history of video games in France: 1960-1991: from labs to teenagers' rooms]. Houdan: Éditions Pix’n Love.

Bogost, I. (2007). Persuasive games: The expressive power of video games. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Brocard, B. (1986a). Meurtres en série manuel. Chalon-sur-Saône: Cobra Soft.

Brocard, B. (1986b). Le créateur du mois: Bertrand Brocart [Creator of the month: Bertrand Brocart]. Tilt (30), 18.

Brocard, B. (2016). Entretien avec Bertrand Brocard [Interview with Bertrand Brocard]. http://controverses.sciences-po.fr/cours/com_2016/jeuxvideos/retranscription-bertrand-b.pdf

Brown, A. W. (1996). Faites vos jeux... Les jeux sont faits [Place your games... The games are made]. I&T Magazine (19), 6-9.

Charreyron, V. (1986). Les arcanes de l’arcade [The mysteries of the arcade]. Tilt (33), 98-103.

Ciel Bleu (1983). Le Vampire Fou [The crazy vampire] [Apple II]. Digital game directed by Jean-Louis Le Breton, published by Ciel Bleu.

Cobra Soft (1984). Meurtre à grande vitesse [High-speed murder] [Amstrad CPC]. Digital game directed by Bertrand Brocard, published by Cobra Soft.

Cobra Soft (1985). Meurtres sur l’Atlantique [Murders on the Atlantic] [Amstrad CPC]. Digital game directed by Bertrand Brocard, published by Cobra Soft.

Cobra Soft (1986). Dossier G: L’Affaire du Rainbow Warrior [Folder G: The Rainbow Warrior Case] [Amstrad CPC]. Digital game directed by Daniel Lefebvre, published by Cobra Soft.

Cobra Soft (1987). Meurtres en série [Serial murder] [Atari ST]. Digital game directed by Bertrand Brocard, published by Cobra Soft.

Cobra Soft (1988). Meurtres à Venise [Murders in Venice] [Amiga]. Digital game directed by Bertrand Brocard, published by Infogrames.

Cobra Soft (1990). Murders in Space [Amiga]. Digital game directed by Bertrand Brocard, published by Infogrames.

Cole, A. (1999). French socialists in office: Lessons from Mitterrand and Jospin. Modern & Contemporary France, 7(1), 71-87. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639489908456471

Costa-Gavras, C. (1982). Missing [Film]. Universal Pictures.

Dauncey, H. (2012). French videogaming: What kind of culture and what support? Convergence, 18(4), 385-402. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856512439509

Debord, G. (1970). The society of the spectacle. Detroit, Michigan: Black & Red.

Deconchat, J. (1987). Logiciels de jeux: Hawaii [Games: Hawaii]. Science et Vie Micro (40), 145.

Delcourt, G. (1984). La puce aux œufs d’or [The Golden Egg Chip]. Tilt (14), 16-22, 82-83.

Delphine Software (1991). Another World [Amiga]. Digital game directed by Éric Chahi, published by Delphine Software.

Donovan, T. (2010). Replay: The history of video games. Lewes: Yellow Ant.

Dupuy-Fromy, S. (2012). Les jeux vidéo dans la société française: Des années 1970 au début des années 2000 [Video games in French society: From the 1970s to the early 2000s] (Phdthesis). Université Paris-Est, Paris.

Eco, U. (2016). Pape Satàn Aleppe. Cronache di una società liquida [Pape Satàn Aleppe. Chronicles of a liquid society]. Milano: La nave di Teseo.

Excalibur (1986). Hawaii [Apple II]. Digital game directed by François Coulon, published by Excalibur.

Exxos. (1987). L’Arche du Capitaine Blood [The Ark of Captain Blood] [Atari ST]. Digital game directed by Didier Bouchon and Philippe Ulrich, published by Infogrames.

Froggy Software (1984). Paranoïak [A weirdo] [Apple II]. Digital game directed by Jean-Louis Le Breton, published by Froggy Software.

Froggy Sofrware (1985a). Le Crime du parking [The parking crime] [Apple II]. Digital game directed by Jean-Louis Le Breton, published by Froggy Software.

Froggy Software (1985b). Le Mur de Berlin va sauter [The Berlin Wall will blow up] [Apple II]. Digital game directed by Tristan Cazenave, published by Froggy Software.

Froggy Software (1985c). Même les pommes de terre ont des yeux! [Even potatoes have eyes] [Apple II]. Digital game directed by Clotilde Marion and Jean-Louis Le Breton, published by Froggy Software.

Froggy Software (1986a). La femme qui ne supportait pas les ordinateurs [The woman who hated computers] [Apple II]. Digital game directed by Chine Lanzmann and Jean-Louis Le Breton, published by Froggy Software.

Froggy Software (1986b). Digital game directed by Pascal Labrevois and François Lamoureux, published by Froggy Software.

Ganser, D. (2006). The CIA in Western Europe and the abuse of human rights. Intelligence and National Security, 21(5), 760-781. https://doi.org/10.1080/02684520600957712

Genette, G. (1997). Palimpsests: Literature in the second degree. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Grallet, G., Paillon, M., & Cockerell, J. (2013, March 25). Jeu vidéo: La “French Touch” prend les manettes [Video games: The “French Touch” takes the controls]. France 24. https://www.france24.com/fr/20130401-tech-24-jeu-video-france-industrie-culturelle-ubisoft-rayman-kobojo-social-gaming

Hoagie (2019). Abandonware France, #MadeInFrance 08: Watch for the Snake -- The History of Cobra Soft. Abandonware France. https://www.abandonware-france.org/ltf_abandon/ltf_infos_fic.php?id=103216

ICOM Simulations (1985). Déjà Vu [Macintosh]. Digital game directed by Todd Squires, Craig Erickson, Kurt Nelson et al., published by Mindscape.

Infogrames (1986). Les passagers du vent [Atari ST]. Digital game directed by Bruno Bonnell, published by Infogrames.

Jahn-Sudmann, A. (2008). Innovation NOT opposition: The logic of distinction of independent games. Eludamos. Journal for Computer Game Culture, 2(1), 5-10.

Karhulahti, V.-M. (2011). Mechanic/aesthetic videogame genres: Adventure and adventure. Proceedings of the 15th international academic MindTrek conference on envisioning future media environments -- MindTrek ’11. Tampere, Finland: ACM Press. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2181037.2181050

Kuhn, R. (2011). The media in contemporary France. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill/Open University Press.

La french touch des jeux vidéo [Video-gaming French Touch]. (2011). Le Parisien. http://www.leparisien.fr/une/la-french-touch-des-jeux-video-02-03-2011-1338677.php

Labrande, H. (2007). La femme qui ne supportait pas les ordinateurs (source code). Hugo Labrande website. http://hlabrande.fr/if/sources/femme.inf

Labrande, H. (2011). Racontons une histoire ensemble: History and characteristics of French IF. In K. Jackson-Mead & J. R. Wheeler (Eds.), IF theory reader (pp. 389-432). Boston: Transcript on Press.

Labrande, H. (2020, March 17). Comments about your article [Letter to Filip Jankowski].

Lacan, J.-F., & Spitz, B. (1984). Ordinateurs. Le Monde. http://www.lemonde.fr/archives/article/1983/08/15/viii-ordinateurs_2826855_1819218.html

Lankhor. (1987). Le Manoir de Mortevielle [Amiga]. Digital game directed by Bruno Gourier, published by Lankhor.

Laroche-Signorile, V. (2015). Le 10 Juillet 1985, le sabotage du Rainbow Warrior [July 10, 1985, The sabotage of the Rainbow Warrior]. Le Figaro. https://archive.is/nOJU5

Le Breton, J.-L. (n.d.-a). Les jeux Froggy Software [Froggy Software games]. Jean-Louis Le Breton. https://bit.ly/3prkIc9

Le Breton, J.-L. (n.d.-b). L’œil du Futur. Jean-Louis Le Breton. https://jeanlouislebreton.com/?page_id=630

Lebelle, B. (2005). Le mur de Berlin va sauter [The Berlin Wall will blow up]. Grospixels. http://www.grospixels.com/site/murberlin.php

Lefebvre, H. (1958). Critique de la vie quotidienne [Criticism of daily life] (2nd ed., Vol. 1). Paris: L’Arche Editeur.

Logiciels d’en Face (1990). L’Égérie [Atari ST]. Digital game directed by François Coulon, published by Logiciels d’en Face.

Lollo, E. (2016). Social capital accumulation and the exercise of power: The case of P2 in Italy. Journal of Economic Issues, 50(1), 59-71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00213624.2016.1147311

Marion, C. (1986). Le créateur du mois: Clotilde Marion [Creator of the month: Clotilde Marion]. Tilt (28), 8.

Medina, E. (2011). Cybernetic revolutionaries: Technology and politics in Allende’s Chile. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb.31687

Montellier, C. (1984). Odile et les crocodiles [Odile and the crocodiles]. Paris: Les Humanoïdes associés.

Munck, R. (2007). Globalization and contestation: The new great counter-movement. London: Routledge.

News: Hawaii (1987). Amstrad Magazine (20), 23.

Pomme d’Or télématique (1985). Science et Vie Micro (14), 13.

Quantic Dream (2010). Heavy Rain [Various platforms]. Digital game directed by David Cage, published by Sony Computer Entertainment.

Riding, A. (1994). Carlos the terrorist arrested and taken to France. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1994/08/16/world/carlos-the-terrorist-arrested-and-taken-to-france.html

Roe, C., & Mitchell, A. (2019). “Is this really happening?”: Game mechanics as unreliable narrator. DiGRA Conference. http://www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/DiGRA_2019_paper_201-min.pdf

Sicart, M. (2008). Defining game mechanics. Game Studies, 8(2). http://gamestudies.org/0802/articles/sicart

Squires, M. (1992). Complete control: Fascination. Amiga Power (19), 70-71.

Steele, J. (2001). Swindler ran empire with army of thugs. The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1331447/Swindler-ran-empire-with-army-of-thugs.html

Švelch, J. (2018). Gaming the Iron Curtain: How teenagers and amateurs in communist Czechoslovakia claimed the medium of computer games. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Therrien, C., Lefebvre, I., & Ray, J.-C. (2021). Toward a visualization of video game cultural history: Grasping the French Touch. Games and Culture, 16(1), 92-115. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1555412019873469

Turner, F. (2006). From counterculture to cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the rise of digital utopianism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Vasagar, J., & Hopkins, N. (2001). King of crime who became as rich as the queen. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2001/may/24/travelnews.travel1