When Seeing is Playing: The History of the Videogame Camera

by Selim KrichaneAbstract

The rise of the "camera" in the context of videogames is generally associated with the widespread use of real-time 3D graphics during the 1990s. The "virtual camera" of videogames is therefore perceived by researchers as a direct and stable consequence of graphical and computational procedures (Manovich, 2001; Jones, 2007). This reading is often supported by the linear narrative provided by the classical history of videogames. Our research aims at retracing the emergence of the notion of "camera" through a close reading of a textual corpus that provides a representative sample of production and press discourses from 1987 to 1998. Data extraction has been conducted by the perusal of two leading European magazines as well as several hundred instruction booklets. In this article, we focus on the earliest conception of the term "camera" within discourses associated with videogames from the end of the 1980s to the mid-1990s, a framing we refer to as the "diegetic camera." Our analysis shows that the word "camera" bears no stable nor irrevocable meaning in the context of videogames, but has rather gone through a historical process of naturalization determined by the gradual disappearance of the cinematic mindset originally associated with the term.

Keywords: Camera, paratext, magazines, 3-D, Historiography, Video game history, Game reviews

Introduction

The research presented here is part of the prolific field of studies dealing with the relationship between audiovisual media and video games. As such, this work mobilizes methodological and epistemological foundations that come from both game studies and film/media studies. While intermediality has been a topic of debate in the early years of game studies (Perron et al., 2019), it has subsequently given rise to important work, on the graphic styles of video games (Järvinen, 2002), adaptations (Picard & Fandango, 2008), photorealism (Perron & Therrien, 2009), machinima (Lowood & Nitsche 2011), or game spectatorship (T.L. Taylor, 2012), among other topics of interest.

This article focuses more specifically on the history of the "camera" in the context of video games. Rather than opting for a formal, technical, or anthropological approach (N. Taylor, 2016), we will focus on the transfer of the notion of "camera" within video game discourses. The mapping of the discursive history of this notion, sketched out in this paper, stems from a larger research study we have conducted on the modes of visualization in video games and their relationship to cinema and television (Krichane, 2018).

The term "camera" has become a familiar expression in discourses addressing videogames since the 1990s. For more than twenty-five years, it has been used by designers and critics alike in order to designate the point of view of a game, the specific framing of the gameworld as presented to the player on his screen. As many researchers have pointed out, the advent of such a term historically associated with the technical apparatus of cinema has taken place in the context of the wide-ranging implementation of real-time 3D graphics in the videogame industry (Manovich, 2001; Nitsche, 2008; Perron & Therrien, 2009). Among researchers focusing on intermediality and the cinematic aspect of certain games (or game genres), the "camera" has attracted a lot of attention as a junction point between the two media. In most cases, the videogame camera has been approached by researchers as a technical entity closely linked to the history of 3D computer-aided design (Jones, 2007). Referring to the famous example of Alone in the Dark (Raynal, 1992), Bernard Perron indicates that since the advent of 3D computer graphics, "the window into the world of videogames is mainly considered to be a virtual camera" (Perron, 2014, p.77).

The Camera as a Technical Entity

In his analysis of 3D gameworlds, Michael Nitsche points out that "technically, a virtual camera is a 2D projection plane, not a spatial entity in the game space" (Nitsche, 2008, p.90). The need for such a projection plane derives from the fact that "virtual environments do not have a ‘natural’ point of view." In order to continuously render and display images of the gameworld on the screen, the game uses a specific module (a set of algorithmic procedures) designated as a "camera" or "virtual camera" in computer design talk: "Each view into the gameworld has to be generated by positioning a virtual camera inside the virtual world" (Nitsche, 2008, p.77).

In their 2005 article, David Thomas and Gary Haussmann argue that the videogame "camera," although by no means restricted to rendering a linear perspective, tends to imitate cinema’s optical camera and its "cinematic perspectives." According to Thomas and Haussmann, the linear perspective in videogames has become a "visual cliché" which is undermining the medium’s expressive potential (Thomas & Haussmann, 2005). Thomas and Haussmann’s take on the videogame "camera" shows how much the meaning of the term is unstable, being used to designate all manners of on-screen visualization in videogames.

If one asserts that the videogame "camera" can generate any kind of non-linear perspective, as is the case with most of Thomas and Haussmann’s examples (Asteroids, Atari, 1979; Super Mario Bros., Nintendo, 1985), then one assumes that the term can be used outside of its original context of 3D computer design. As they discuss examples of non-linear (and therefore, non-cinematic) perspectives among classical arcade games, the authors focus their attention on the case of the wrapped-around space of Asteroids.

Their analysis aims at identifying the type of "camera" responsible for rendering the space of the game, stating that "when you consider the notion of camera in the game Asteroids, your first instinct is to assume the camera position is at a fixed point, hovering high above in space, looking down on the scene […]" (Thomas & Haussmann, 2005).

Although the thorough analysis of modes of visualization and "spatial structures" (Wolf, 2001, p.53) in videogames is a viable -- if not necessary -- focus of research in the field of game studies, we believe that the words we use in conducting such research need to be scrutinized.

Such scrutiny should entail retracing the discursive history and formation of key concepts as well as the semantic shifts they have undergone in discourses. One of the problems that rises from an ahistorical use of the word "camera" comes from the fact that in the case of Asteroids -- and more broadly, of all and every arcade game from the classical era -- the word "camera" was never used at the time of their release. Not by designers, players, critics, nor editors. The word was simply not in circulation at the time and did not appear in the paratext of videogames. One can easily surmise the methodological bias that arises from backdating a notion, especially if one is hoping to grant it theoretical valence.

To put it differently, before asking "Where is the camera?" in Asteroids, one should ask, as did Edward Branigan in the context of film theory, "What is a camera?" (Branigan, 1984a). Moving from "Where" (or "How") to "What" is also a way to move away from the technical primacy often at work in media studies, in favor of a contextualized and discursive analysis of the term "camera."

What is a Camera?

Rather than a technical object or an algorithmic construct, the "camera" can be seen and scrutinized first and foremost as a "label" used by players, designers, or critics in order to make sense of their gaming experience. Our working hypothesis suggests that the "camera" cannot be approached as a preconceived theoretical concept bearing an irrevocable meaning, independently of the various historical contexts that have enabled its use. We follow here Branigan’s methodological precautions first stated in his 1984 article "What is a Camera," more recently followed up and expanded to a series of key notions in the field of film studies (Branigan, 2006).

Looking at various canonical texts of film studies, Branigan has shown that the term "camera" can bear different meanings depending on the writer’s theoretical agenda and methodological framework. In doing so, Branigan distinguishes eight different conceptions of the term "camera" in discourses related to cinema. His method for discourse analysis offers a viable alternative to decontextualized efforts made to define theoretical notions:

The question "What is a camera ?" resembles André Bazin’s famous question "What is cinema ?" Both questions seem to call for a special kind of definition that seeks to isolate an inherent quality, an essence, shared by all instances of "camera" or "cinema" while being absent from all things not a camera or not cinema. In this approach an object’s unique existence is defined by a set of individually necessary and jointly sufficient conditions. However, one problem that has arisen in asking this kind of general question is that the relationship an object has to one or more contexts is not given adequate importance when defining the object. In thinking about the nature of a given object, we should keep in mind that a thing is not defined simply by its intrinsic properties (e.g., material and shape) but also by its placement within various causal sequences as well as its relationship to other things (other contexts, other states of being). (Branigan, 2006, p.65)

The term "camera" bears a different meaning whether it is associated with a light recording machine or the shifting point of view of a film. Whether it is used by a critic as an embodiment of the director’s "point of view" in order to assert an auteurist judgment, or defined by a scholar as the primary vector of spatial organization. The semantic discrepancies of the term "camera" are even more apparent when one considers its migration from one medium to another, from film to videogames.

According to Branigan’s cognitive stance, the term is often used by spectators and critics as a "label" in order to aggregate the various "spatial effects" that constitute cinematic space (Branigan, 1984a). This is where our approach significantly departs from Branigan’s. His interest in the term "camera" stems from his theoretical framing of the "point of view" in cinema (Branigan, 1984b). As such, looking at the various inflexions and semantic functions of the term in discourses is mainly a way to warrant his own conception of the "camera." As it happens, the eighth and final definition of the "camera" in Branigan’s work is his own. The "camera" is thought of as a label used by viewers to formulate inferences and test hypotheses with regards to on-screen spatial variations: as a "‘tool’ […] employed by a spectator to solve interpretive problems" (Branigan, 2006, p.90).

Methodology

Contrary to Branigan’s approach to discursive analysis, our study is based on a methodically selected textual corpus that offers a representative sample of production and press discourses from 1987 to 1998 in the field of videogames [1]. In order to retrace and examine the formation of the term "camera" in discourses associated with videogames, we looked for every instance of the term by conducting a close reading of two major European magazines: Génération 4 and Computer & Videogames. Based on the identified occurrences of the term and the associated games, this initial reading of two magazines over a period of 10 years then led us to do additional reading of other specialized magazines and game manuals in order to further document the implementation of the notion of “camera” within videogame discourses. Given the varying textual layouts and the many-colored look of videogame magazines, the preliminary tests conducted using OCR software proved too unreliable, compelling us to resort to a "traditional" perusal [2].

The two main magazines of our corpus were chosen based on a series of criteria aimed at ensuring their representativity: continuous publication of magazines over the studied period, independence from the industry, wide circulation, and variety of the games and platforms covered (home consoles, arcade, micro-computers, etc.) [3]. Our geographical and institutional anchorage led us to constitute a corpus in French and in English. We can further note that the specialized press in English served as an important model for the French-speaking press since the beginning of the 1980s.

These various textual sources were read carefully, looking for occurrences of the term "camera" in order to trace its discursive history. We have privileged, within the framework of our study, a qualitative analysis in order to trace the process of formation of the term, rather than a quantitative study. The aim of this work is not to provide quantitative results that would fit into a methodology similar to the ones frequently adopted in the fields of Natural Language Processing or Digital Humanities (Pelletier-Gagnon, 2018; Rochat, 2019). Rather, it demands to be perceived as a complementary approach to such methods [4].

Given the length constraints of this essay, we will focus on a major result of this research: the progressive shift of the notion of "camera" from a diegetic to a virtual framing. The examples presented hereafter are representative of this general transition, on the basis of all the sources we have examined. We deliberately refrain from studying the presence of the term in contexts that are already well documented, such as American or French adventure games of the 1980s-1990s (Sierra On-Line, Lucasfilm Games, Delphine Software), action-adventure games of the mid-1990s, and only briefly touch upon video games that belong to the "canonical" history of the medium (e.g., Super Mario 64, Lara Croft: Tomb Raider) [5].

Game manuals tell us a lot about how designers intended their game to be played and provide a valuable insight into the lexis used to address the players. These booklets offer a rich textual resource encompassing the lexical options at hand to designate representations, point of view, or movement in videogames. Trade magazines also constitute a rich (and mainly untapped) resource, as they present a regularly updated trace of the assessment of games and a reworking of the promotional discourse produced by editors. These documents allow researchers to reconstruct a history of discursive (dis)continuities within the videogame paratext (Foucault, 1969, pp.9-10). A close reading of trade magazines gives us information about the history of videogames, their various historical modes of consumption, and the assessment criteria used by critics. Beyond the normative dimension of reception practices (Bordwell, 1991, pp.34-35), every article constitutes a textual trace of the journalist’s game experience. Such articles can be seen as a "mediation space" between gamers and designers, opened up by the discursive practice of game critics (Noyer, 2001, pp.69-70).

While reading this vast collection of documents, we singled out every instance of the term "camera" and paid attention to the numerous notions that were used in conjunction with the latter [6]. One of the unexpected findings that emerged from our research is related to the varying role of the cinematic mindset when it comes to the uses of the word "camera" in relation to videogames. Contrary to the assumption of many theoretical discourses in game studies, the "cinematic" quality of the videogame "camera" constitutes a historical variable rather than an intrinsic property. From such a standpoint, the "cinematic" aspect of videogames becomes a discursive and historical issue rather than an ontological debate.

Following Tortajada and Albera’s research in epistemology of viewing and listening "dispositives" (2015) [7], our approach considers the "camera" as a "key concept" associated with videogames. In order to examine the term’s epistemological foundations and understand its use in a given textual environment, one has to reflect upon the fact that "the type-notion has a history, which is that of its ‘making’: as a consequence, its use should be historicized and de-naturalized" (p.34). This statement aptly illustrates the main goal of our textual analysis which aims at retracing the advent and evolution of the term "camera" in reception and production discourses in the field of videogames, and in so doing, reconstructing the "cluster of relations" which contains this notion over the historical period considered (1987-1998).

In the following part of this article, we will focus on the earliest conception of the term "camera" within discourses associated with videogames from the end of the 1980s to the mid-1990s, a framing that we will refer to as the "diegetic camera." We will argue that this specific conception of the term "camera" -- dependent upon "causal sequences" strongly linked to a cinematic mindset -- has been crucial to the term’s implementation in discourses surrounding videogames.

Within this discursive category we call the "diegetic camera," we grouped all the instances of the term that are coupled to an overt portrayal of a camera within the diegetic world of the game. Contemplating the history of the term "camera" in videogame discourses, we came to realize how much televisual norms and practices impacted the spatial structures and images of driving and sports simulations as early as the 1980s. This particular lineage of the videogame camera, tracing back to sports simulations (as well as flight simulations), is often neglected in traditional historical narratives. The diegetic camera delineates a conception of the videogame camera very much dependent upon its original cinematic framework of intelligibility through a series of associated notions such as "director," "film," or "editor" [8].

Within our theoretical framework, the "diegetic camera" is opposed to the "virtual camera." The "virtual camera" refers to the use of the term "camera" deprived of references to recording, capture, or any similar terms connected to a cinematic mindset. The "virtual camera" represents the end result of the term’s naturalization process in the context of videogames and thus coincides with its contemporary meaning in discourses. Although both conceptions appear very early on, the "virtual camera" only becomes the dominant framing of the notion during the second half of the 1990s. Hence, the varying historical meaning of the term "camera" in the paratext of videogames follows the trajectory of a gradual disappearance of the semantic field of cinema within discourses.

The Diegetic Camera

As we have stated previously, the "camera" is often associated with the rise of 3D graphics in the mid-1990s. Famous examples often cited in classical historical accounts in order to illustrate the emergence of the "camera" and/ or the advent of 3D graphics include "early" titles such as Alone in the Dark (Raynal, 1992) and Virtua Racing (Sega AM2, 1992; cited by Donovan, 2010, p. 267), or canonical ones from the mid-1990s such as Tomb Raider: Lara Croft (Core Design, 1996) and -- very frequently -- Super Mario 64 (Nintendo, 1996). Although the classical historical narrative usually lingers upon "pioneers" in the field of home consoles (e.g., Trip Hawkin’s 3DO) and arcade games (Sega’s AM2 team and Atari’s Hard Drivin’, 1989) before turning to the dissemination of 3D graphics in 1995-1996 with the release of Sony’s PlayStation and Nintendo’s Nintendo 64 (Donovan, 2010, pp.265-279; Kent, 2001, pp.481-525), the history of 3D graphics has in fact been strongly influenced by productions and experimentations in the microcomputer sector during the second half of the 1980s.

In its January 1989 issue, Génération 4 dedicates an entire section to "3D games" which aims at presenting a ranking of all the games "that include the slightest bit of 3D" [9]. In the home computer sector, the 3D craze is wide-ranging, involving exploration and puzzle games (The Sentinel, Crammond, 1986), sports simulations (3D Pool, Aardvark Software, 1989), flight simulations and space exploration games (Elite, Acornsoft, 1984; Starglider, Argonaut Software, 1986; Voyager, Ocean Software, 1989), shooting games (Backlash, Novagen Software, 1987), as well as driving games (Stunt Cars, Distinctive Software, 1990).

However, the extensive use of real-time 3D graphics and filled polygons in many computer games during the second half of the 1980s does not guarantee the use of the term "camera" by the editors or the press. In fact, the vast majority of videogames that partake in this "3D craze" are not associated with the word "camera." This historical state of affairs complicates the causal relationship that many researchers establish between a technical paradigm (3D computer design) and the use of the term "camera" (Manovich, 2001). For instance, the computer game Driller (Major Developments, Incentive Software, 1987), often cited as an early example of real-time 3D games (being the first to use Incentive’s 3D engine Freescape), does not include the word "camera" in its thirty-two-pages-long instruction booklet. The manual of the game describes the part of the screen that renders the gameworld as the "viewing window" [10] while the promotional discourse boasts the "revolutionary 3-D scaling and perspectives" [11].

The first instance of the term "camera" we found within our corpus appears inside Starglider’s instruction booklet [12]. While the front panel of the space ship controlled by the player is not termed "camera," the game includes a secondary game mechanic that allows the player to launch a camera into space in order to inspect the gameworld without risking being attacked by enemy crafts. This peculiar system called "VidiMon remote-controlled television guided camera" [13] works as an actual camera inside the fictional world of Starglider and replaces the forward viewing panel of the ship when used by the player (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Starglider’s remote-controlled "camera-missile" (Argonaut Software, 1987, DOS version).

In this instance, the use of the term "camera" (as an alternative to the common term "view") is motivated by an in-game remote recording device, which momentarily supersedes the pilot’s view of the gameworld. The occurrence of the term constitutes a prime example of its diegetic conception, central to its naturalization process. In 1987, Starglider’s "camera" is not solely a designation of a computerized image rendering technique associated with three-dimensional modeling, but rather an "actual" (i.e., fictional) camera within the gameworld: a diegetic recording machine implemented as an optional tool giving more leeway to the player.

A year and a half later, the conception of the "camera" within discourses associated with the Starglider series evolved. Although the term "camera" does not appear inside the Starglider II diegetic world, the term is used by the press in order to describe the "external views" available to the player in addition to the standard "cockpit view" situated inside the Icarus spacecraft (Figure 2). Even though the term "camera" does not appear in the instruction booklet of the game, it is used by the press already familiar with its meaning within the context of 3D computer-assisted design. A journalist from Génération 4 indicates that the game "offers a variety of camera angles that allow you to observe space all around you and even glance at the Icarus from any point in space" [14].

Figure 2. An "external view" from Starglider II referred to as a "camera" by the press. (Source: www.mobygames.com)

The multiplication of various "views" available to the player in space combat games and flight simulations constitutes a decisive factor in the expansion of the term "camera" from 1987 to 1989. As illustrated by Starglider II, the word "camera" is used to describe a specific view of the gameworld, close in many respects to the "camera angles" available in computer-aided design software which benefit from a growing popularity during the same period among computer enthusiasts. Furthermore, the spatial structure of Starglider II draws heavily upon the visualization norms and codes of flight simulations, being "among the most popular micro applications" in the late 1980s, according to a journalist from ACE magazine [15].

As flight simulations aim at reproducing the real-life conditions of an aircraft’s flight, they have constituted a genre favorable to technical and graphical innovation during the second half of the 1980s (Manovich, 2001; Picard, 2009). The semantic shift at work within the Starglider series regarding the "camera" -- moving from a localized diegetic entity to a virtual camera used to designate the "external views" from the aircraft -- also occurs within flight simulations. As noted by ACE Magazine’s journalist, the choice of "aerial views" available to the player has been an important feature of the genre that allowed players to compare the different sims. Starting from 1987-1988, most flight simulations let players switch between several different "views" during the game.

Writing about the various "views" available in Falcon (Mirrorsoft, 1987-1988), a critic mentions the presence of a "remote camera" [16] that enables the player to zoom and rotate the viewpoint around his plane. The term "camera" regularly appears within discourses in order to designate the "external views" in flight simulations (although it does not appear in the instruction booklet of Falcon) [17]. The discrepancies at work between the lexicon used by the press and the words favored in the game manuals show how much the emergence of the term "camera" has been gradual and somewhat erratic, at a point in history when its meaning was not yet constant (nor consistent!). The diversity of viewpoints in most flight simulations is furthermore combined to a popular feature: the "replay mode." Starting from 1987-1988, many flight simulations enable players to "replay" their game session using a graphical interface reminiscent of a VCR display [18].

"Press C for Camera": The Replay Mode

The replay option has significantly contributed to the dissemination of the term "camera" in videogame paratext since the end of the 1980s. The term frequently appears within discourses related to Lucasfilm’s Battlehawks 1942 released in 1988 [19]. A critic from Génération 4 takes note of the "photorealistic" appearance of the game and further comments: "Battlehawks 1942 is more of an actual movie, as everything in it is so realistic!" According to the journalist, the cinematic aspect of Battlehawks is in part due to its "replay mode," allowing players to "see the whole fight again from any vantage point" (Figure 3).

Figure 3. A replay sequence from Battlehawks 1942 (Lucasfilm Games, 1988). The "camera indicator" can be seen on the plane’s control panel. (Source: www.mobygames.com)

The wide array of dial switches inside Battelhawks’ Second World War crafts includes a "camera indicator" that is switched on as soon as the player uses the "replay camera." According to the game manual, "the replay camera is an excellent tool for learning flight tactics, as well as a way to enjoy the game from a movie-like perspective" [20]. Accordingly, the recording of a game session and its subsequent viewing is thought of as a "cinematic" enterprise by the game developers. Within production discourses, the term "camera" is used as a means to designate the editing practices at work during the replay, as well as the recording of the game session. On a rhetorical level, the "camera" also promotes the "cinematic" aspiration of the game, used by the production team as a marketing feature.

In the course of its description of the replay mode, Red Baron’s (Dynamix, 1990) instruction booklet states: "You essentially become actor, producer and director of your own WWI aerial dogfights." [21] This statement shows how much the "camera" of the game is dependent upon a cinematic mindset. The algorithmic procedures at work in the continuous storage of "game states" and in their playback through a VCR-like interface are addressed as a set of cinematic practices (Figure 4). The replay option also singles out the player’s spectatorship: seeing becomes in itself a primary game mechanic [22]. The replay option entails a major reconfiguration of the "gaming situation" (Eskelinen, 2001), well before the recording and sharing practices popularized by platforms such as YouTube. As early as the end of the 1980s, the replay mode forecasts the empowerment of the act of looking as an autonomous game mechanic.

Figure 4. The VCR-like display of Red Baron’s "Mission Recorder" option (Dynamix, 1990).

Coming back to the term "camera," one can note that, starting from 1988, its use is very systematic within the promotional and press discourses that refer to the replay mode in flight simulations. What is more, the replay option as well as the abundance of various "views" will progressively gain ground within dominant modes of visualization and become a model for sports simulations (football, basketball, golf, etc.) and driving simulations [23]. Contrary to flight simulations, such sports have long been mediated through televisual broadcasting, prior to their remediation as videogames. As such, their representation derives from institutionalized "modes of audiovisual representation of sports" (Guido, 2010, p.193) that have their own multifaceted history. Such modes of representation will become a central model for sports simulations during the 1990s. Since 1988-1990, the visual architectures of many sports simulations are accompanied by several "TV cameras" in an effort to remediate televisual modes of representation. Accordingly, the point of view is coined "camera," referring to the fictional presence of a recording device within the diegetic world of the game.

While the vast majority of studies dealing with the relationship between audiovisual media and video games have focused on the modeling function of "cinema," these examples show that television, which has incidentally been instrumental in the technological history of video games (Lowood 2009), has also played an important role in the development of video games’ modes of visualization.

Driving and Sports Simulations

Among the six different "camera angles" available in the replay mode of Indianapolis 500 (Papyrus Design Group, 1989), the game manual mentions the "TV mode" [24], which renders the view of a "camera" situated inside a blimp flying over the racetrack. Several "camera" locations are predefined, serving as the various angles available to the player when using the replay mode. The edited sequence that derives from this specific replay mode resembles the televisual mode of representation of F1 races. The extensive use of the term "camera" also appears within Distinctive Software’s 4D Sports series as early as 1990. 4D Sports Tennis, released on PC in 1990, made an extensive use of 3D modeling techniques in an effort to remediate the televisual mode of representation of tennis. The game offers two very distinct modes of visualization. As stated by a critic from Génération 4, the user can "see the field through the eyes of [his] tennis player, or see him as on TV. A system composed of cameras, rotations and zooms allows you to fully customize the in-game view" [25].

The position of the camera in 4D Tennis corresponds to "the main camera position" of tennis’s televisual mode of representation as defined by Laurent Guido (2010). His description of "Television’s Tennis Dispositive" is based on the analysis of four Wimbledon finals that took place between 1977 and 2007. The researcher shows that this specific camera position, as it "provides a general view of the court from above, covering the whole breadth of the surface of the court in a single, synthetic vision" (p.198), has been constantly used for over thirty years, serving as the organizational matrix for the rest of the camera angles involved in shooting and broadcasting tennis matches. It comes as no surprise that such a camera angle has been chosen by 4D Tennis designers as a means to remediate tennis’s televisual mode of representation (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The "main camera position" as well as the "Camera Control" panel from the main menu in 4D Tennis (Distinctive Software, 1990).

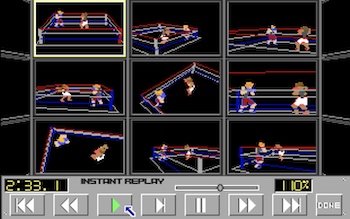

The series’ second game, 4D Boxing, published a year later, offers a greater diversity of camera angles (Figure 6). It is possible to retrace -- within the scope of the 4D Sports series -- a historical evolution in sports simulations that follows that of the televisual representation of spectator sports, namely through the increased number of camera angles. In a very positive review of 4D Boxing in 1990, the French critic Didier Latil declares that the "multiple cameras" make for "the game’s most interesting feature" [26]. The instruction booklet’s chapter on camera control contains seventy-one mentions of the term "camera" and states that the player will soon become "the best TV director in [his] streets" (providing he follows the instructions detailed in the manual!).

Figure 6. Multiple camera angles in 4D Boxing (Distinctive Software, 1991).

Thus far, we have provided a few examples of the use of the term "camera" within discourses associated with sports and driving simulations around 1990. These modes of visualization will spread throughout the decade along with the term "camera." Among the hundreds of occurrences of the term "camera" we have identified from 1988 to 1996, the vast majority was used in reviews addressing sports simulations. This is notably the case in football simulations such as FIFA International Soccer (Extended Play Production, 1993), even though the first versions of the game did not include real-time 3D graphics (on Genesis and SNES) [27]. In a preview article of FIFA’s 3DO version dated April 1994, a critic beckons the readers to "imagine a camera that broadcasts the match from any point on the field" and further adds: "The end result will be very close to an actual TV broadcast" [28]. The instruction manual of the game makes use of the term "camera" in order to name the seven different visualization options available to the player in the menu of the game (Figure 7).

Figure 7. The different "camera angles" available in FIFA International Soccer (3DO, 1994) (Source: The 3DO Club www.club3do.wordpress.com/page/2/)

The multiplication of "camera angles" also appears in golf simulations during the 1990s. In 1992, PGA Tour Golf II (Sterling Silver Software) allowed the player to "use a camera to look at every hole" [29], allowing him to plan his actions ahead. In 1995, Scottish Open (Core Design) offered "scores of different camera angles from which to watch your player or your ball taking flight -- all emphasizing the detail of the 3D environment" [30]. Link LS 1998 Edition (Access Software) released in 1997 had "10 different camera angles," which would "embarrass the Canal+ sports department" according to a French critic.

The latter statement establishes a comparison praising videogames at the expense of television, in a context of heightened media competition. This comparative process stems from production discourses whose primary goal is to promote videogames among competing media in the domestic space. The ensuing media rivalry is at the same time a question of resemblance and distinction, as the "new media" often relates to cinema or television through the use of norms and codes familiar to the audience (Bolter & Grusin, 1999), while at the same time having to set itself apart from the old. This discursive process is in part responsible for the overt presence of the cinematic framework within discourses addressing videogames.

The "Player as Director" Myth

As the term "camera" gains ground within discourses about videogames, it is often accompanied by the associated notions of "director" and "directing" in the first half of the 1990s. The displacement of a cinematic mindset mostly operates within games that explicitly draw upon the representational codes of cinema or television, as is the case in the previously addressed 4D Boxing. Such a rhetorical strategy aims at portraying the player as a film (or television) director and thus makes use of the legitimacy of cinema in portraying the player’s experience. The "player as director" myth appears in the famous example of Super Mario 64 (Nintendo, 1996), a game that emphasizes its use of the cinematic apparatus by portraying the Lakitu brothers as "cameramen" who follow Mario’s every step in the game. The game manual dedicates several pages to the "camera options," stating early on that the user is "not just the player, but the cinematographer, too!" [31]

Such a conception of the "camera" also appears within the paratext of Stunt Island (The Assembly Line), a computer game published by Walt Disney in 1992, described on its game box as a flight simulation coupled with a "filming simulation" [32]. In Stunt Island, the player takes part in the shooting of stunt sequences on an imaginary island purchased by Hollywood’s "major movie studios" [33].

In this uncommon computer game, the player has to complete a series of missions based of flying feats. His trials and errors are punctuated by a fixed screen showing a film operator behind his camera, with a clapperboard counting the number of takes -- amounting to the number of trials the player has undertaken so far (Figure 8). As soon as the player has accomplished a mission, he is brought to the island’s editing room where he takes part in the postproduction of the sequence and presents it to a test audience (Figure 9-10). This screening leads to a final score calculated by the game’s (rather obscure) algorithm, taking into account the player’s actions as well as the positioning of the eight different in-game "cameras."

Figure 8. Director’s screen in Stunt Island (The Assembly Line, 1992), appearing in between the player’s trials.

While flying his stunt plane, the player can choose from a selection of "internal views" and a "spotter plane view," which corresponds to what is usually referred to as a "third-person view" in present-day vocabulary. The choice of terms can easily be explained as a way to distinguish the "views" from the eight diegetic cameras positioned by the player within the gameworld prior to each stunt. In view of our discursive classification, Stunt Island represents the utmost example of the diegetic conception of the videogame camera, highly dependent upon a cinematic mindset, both in terms of visualization and gameplay. Within videogame discourses, the term "camera" can migrate while carrying in its wake a set of associated notions used by game designers in order to create a unique game experience which amounts to playing at filming, in the case of Stunt Island.

Figure 9. Editing room on the imaginary island of Disney’s "Filming Simulation."

Figure 10. Test screening on the imaginary island of Disney’s "Filming Simulation."

From Diegetic to Virtual: Towards the Lexicalization of the "Camera"

Focusing on the diegetic conception of the videogame camera, we have shown how much this framing of the notion has been crucial to the implementation of the term within discourses addressing videogames from 1987 to 1996. The "diegetic camera" will nonetheless make way to a conception of the term deprived of notions reminiscent of the cinematic (or televisual) frame of intelligibility. Within our discursive classification, the "virtual camera" designates this specific framing of the notion that gains ground during the second half of the 1990s, comprising the instances of the term that are not associated with words stemming from a cinematic mindset. Although the cinematic framework has been crucial to the term’s initial implementation within discourses about videogames, its naturalization process has involved the gradual disappearance of such a mindset. Indeed, in 1990-1991, a French critic could write concerning the "camera" in Chuck Yeager’s Air Combat (Electronic Arts, 1991) that it "shot" [filmer] the plane’s flight, just as 4D Boxing’s production team could suggest that the player would become a "TV Director" while playing the game. Just a few years later, this set of cinematic terms would soon disappear from discourses about videogames [34]. Starting from the mid-1990s, the term “camera” designates the point of view and its manipulation by the player, mostly associated to notions specific to gaming, such as "mobility," "control," or "maneuverability" (Krichane, 2018: pp. 191-213).

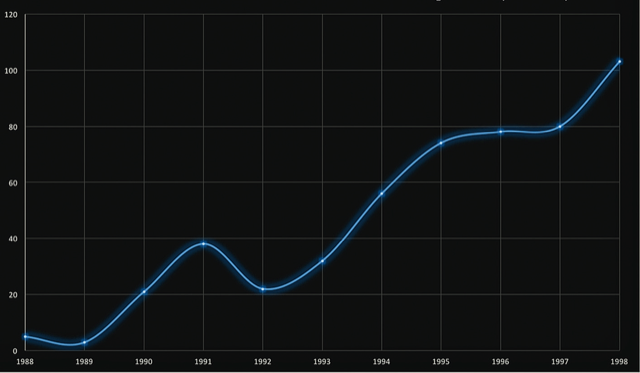

The naturalization process of the "camera" within discourses has been established by means of a transition from a diegetic conception to a virtual understanding of the term suggesting that the notion has gained a certain self-sufficiency in regards to its original discursive context. We believe that the rationale behind this transition is multifaceted as it involves a cluster of determination ranging from the institutionalization of 3D graphics in the mid-1990s, to the intense aesthetic dialogue going on between cinema and videogames during the same period. The naturalization of the term is also a matter of sheer numbers (Figures 11-12). Starting from 1995-1996, it is therefore possible for the term to be -- mainly -- used without reference to a cinematic framework since it has become a familiar notion within discourses. From 1996-1997 onwards, most magazine issues in our corpus include from fifteen to twenty instances of the word "camera," whereas the term was quite rare within the first years of the same decade. Lastly, we should note that this naturalization process within discourses is also dependent upon the broader media landscape. According to Blanchet, in the late 1990s, the videogame industry acquired "a growing self-sufficiency in regards to other media, and especially in regards to cinema" (Blanchet, 2010, p.340). The process of "discursive emancipation" we have come to retrace happens concomitantly to the economic empowerment of the videogame industry.

Figure 11. Number of instances of the term "camera" found in Génération 4 (No. 1-117) between 1988 and 1998.

Figure 12. Number of instances of the term "camera" found in CVG from January 1988 (No. 75) to December 1998 (No. 205).

Endnotes

[1] One of our main working hypotheses was that the naturalization of the notion of "camera" within video game discourses had taken place from the end of the 1980s to 1997-1998. In order to confirm the relevance of our lower historical bound, we proceeded initially to a series of disparate readings, in order to gather various samples, guided by intuition, chance or the analysis of a specific game. As part of a research around the adventure games series King's Quest (Sierra On-Line, 1984-1998), for example, we had the opportunity to go through a set of articles from the 1980s (Krichane 2015). Such readings allowed us to confirm the absence of the term "camera" before the period under consideration.

[2] The same choice has been favored by Carl Therrien in his work on the notion of "First-Person Shooter" (Therrien, 2015).

[3] For more information concerning the research corpus (periodicals and game manuals), see Krichane, 2018: pp.115-121.

[4] For a quantitative study of textual sources based on a set of videogame magazines, see our article (in French) on the appearance and circulation of the term "cinematic" between the English-speaking and French-speaking press (Krichane & Rochat, 2018).

[5] For a more detailed presentation of this study and its results, we encourage the reader to refer to our book available in French: The Imaginary Camera. Video Games and Modes of Visualization [La Caméra imaginaire. Jeux vidéo et modes de visualisation] (Krichane, 2018).

[6] We have initially consulted our sources during several visits at the International Center for the History of Electronic Games (ICHEG, Strong Museum, Rochester) where we had the chance to delineate a representative sample of journalistic discourses. The study was then continued using online databases that archive various textual resources related to the history of videogame.

[7] The term "dispositive" ("dispositif" in French, often translated as "apparatus") has been widely used and discussed in the work of Michel Foucault. The latter defines the term as "a thoroughly heterogeneous ensemble consisting of discourses, institutions, architectural forms, regulatory decisions, laws, administrative measures, scientific statements, philosophical, moral and philanthropic propositions - in short, the said as much as the unsaid." (Foucault, 1980: p.194). For a recent discussion of the use and limits of this notion within film and media studies, see Albera & Tortajada, 2015: pp.21-44).

[8] For example, Red Baron’s instructions booklet states in its description of the "replay" option that "[the player] essentially become[s] actor, producer and director of [his] own WWI aerial dogfights." Red Baron (Dynamix, 1990), game manual, p.C-46.

[9] Génération 4, No. 8, January 1989, pp.78-79. My translation.

[10] Driller’s instruction booklet, 1987, pp.25-26. The "viewing window" is described as "a dense and durable Transpex screen providing you with a survey of the immediate surroundings."

[11] Driller, game box, US version, back cover.

[12] Starglider is a wire-frame 3D space combat simulation created by Argonaut Software and distributed by Rainbird, initially on Atari ST (1986-1987). An earlier example (prior to our corpus’s lower bound) appears on Gunship’s game box (MicroProse, 1986), which mentions a "unique zoom TV camera," allowing the player to select an enemy target and visualize a 3D model of the craft on his flight panel. Gunship, game box, DOS, 1986, UK.

[13] Starglider instruction booklet, Amiga, 1987, p.11: "The AGAV is fitted with a revolutionary new system: the VidiMon remote-controlled television guided camera. Using a high-definition video camera, the AGAV pilot is able to transmit pictures directly back to Military Headquarters at Qazalon City. An automatic sliding visual display has been incorporated into the craft which monitors the flight of the camera. The camera’s flight is started by pressing the LAUNCH button on your keyboard console. Once the camera has been launched, you can guide it using the normal AGAV flight controls […]."

[14] Génération 4, No. 6, November 1988, p.84. My translation.

[15] ACE Magazine, No. 5, February 1988, p.69.

[16] Zero Magazine, No. 1, November 1989, p.24.

[17] A critic from Génération 4 mentions "the different external vantage points and views from the plane taken from a camera" while discussing Jetfighter (Brøderbund, PC, 1988). Génération 4, No. 11, May 1989, p. 52. In his description of Jet (sequel to Flight Simulator 2, SubLOGIC) a critic discusses the "camera view that follows you everywhere". Génération 4, No. 4, Summer 1988, p.61. My translation.

[18] Falcon’s Amiga version has a "replay mode" with a diegetic polish, as it is conceived as a "black box" in the fictional universe of the game. Ervin Bobo states: "A black box can be used to replay parts of your mission, including encounters with MiGs." COMPUTE’s Amiga Resource, No. 1-2, Summer 1989, p.63.

[19] It is the first game released by Lucasfilm Games LLC on 16-bits microcomputers. The company was then known for their adventure games, which already displayed symptoms of a certain cinematic envy.

[20] Battlehawks 1942 instruction booklet, 1988, PC, pp.61-62. The controls of the camera are mapped as follows: "C: Toggle Replay camera on/off," "R: Enter REPLAY mode" (p.67).

[21] Instruction booklet, Red Baron (PC), p.C-46.

[22] In this article, "game mechanics" are understood as the "actions the players take as means to attain goals when playing" (Järvinen, 2007, p.135). One can further note that the progressive autonomization of the act of vision in relation to other game mechanics is a historical condition of possibility for the development of certain practices, such as photography in games (Poremba, 2007; Möring & Mutiis, 2019), or contemporary spectatorship practices (i.e. e-sports, Twitch streams, etc.).

[23] A critic from The One Magazine outlines the genealogy going from flight simulations to sports sims while discussing 4D Boxing: "The main draw of [4D Boxing] is the use of a graphic style more often associated with flight simulations than sports (although Palace’s Tennis is a notable exception)". The One Magazine, No. 25, October 1990, p.129.

[24] Indianapolis 500: The Simulation game manual, Amiga, 1990: "When you reach the end of the replay tape, a horizontal line rolls down the screen and the replay starts over. Highlight the view you want by pressing Spacebar, or by moving the mouse or joystick forward, backward, right, or left". The replay mode also offers a "slow motion" option.

[25] Génération 4, No. 35, July-August 1991, p.103. My translation.

[26] Génération 4, No. 26, October 1990, pp.56-57. My translation.

[27] The SNES version of FIFA International Soccer includes a "camera option" that allows the viewpoint to roam the field during free kicks, kickoffs, and corners. The player in control of the ball appears in an embedded window in the top-right corner of the screen.

[28] Génération 4, No. 65, April 1994, p.26. My translation.

[29] Génération 4, No. 65, April 1994, p.100. My translation.

[30] Computer & Videogames, No. 161, April 1995, p.26.

[31] Super Mario 64, game manual, Nintendo 64, US version, p.20.

[32] The game is subtitled "The Stunt Flying and Filming Simulation". Stunt Island’s game box, US version, 1992.

[33] Stunt Island, game manual, US version, p.3.

[34] In this sense, Super Mario 64 is a very late example of the "diegetic camera" within videogames, connected to the late transition towards 3D graphics initiated by Nintendo with its 64-bits console in 1996 (Nintendo 64).

References

Aardvark Software. (1989). 3D Pool [Micros]. Digital game published by Firebird Software.

Access Software. (1997). Link LS 1998 Edition [PC]. Digital game published by Access Software.

Acornsoft. (1984). Elite [BBC Micro]. Digital game published by Acornsoft Limited.

Albera, F. & Tortajada, M. (2015). The Dispositive Does Not Exist! In F. Albera & M. Tortajada (Eds.), Cine-Dispositives: Essays in Epistemology Across Media (pp.21-44). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Argonaut Software. (1986). Starglider [Micros]. Digital game published by Rainbird Software.

Argonaut Software. (1988). Starglider II [Amiga & Atari ST]. Digital game published by Rainbird Software.

Atari. (1979). Asteroids [Arcade]. Digital game published by Atari.

Atari. (1988-1990). Hard Drivin’ [Arcade & Micros]. Digital game published by Atari.

Blanchet, A. (2010). Des Pixels à Hollywood. Cinéma et jeu vidéo, une histoire économique et culturelle. Châtillon: Pix’n’Love.

Bolter, J.D. & Grusin, R. (1999). Remediation. Understanding New Media. Cambridge/London: The MIT Press.

Bordwell, D. (1991). Making Meaning: Inference and Rhetoric in the Interpretation of Cinema. Cambridge/London: Harvard University Press.

Branigan, E. (1984a). What Is a Camera? In P. Mellencamp & P. Rosen (Eds.), Cinema Histories, Cinema Practices (pp.87-100). Frederick, Maryland: University Publications of America.

Branigan, E. (1984b). Point of View in the Cinema. A Theory of Narration and Subjectivity in Classical Film. Berlin/New York/Amsterdam: Mouton Publishers.

Branigan, E. (2006). Projecting a Camera. Language-Games in Film Theory. New York/London: Routledge.

Core Design. (1995). The Scottish Open: Virtual Golf [PlayStation, Saturn & PC]. Digital game published by Core Design.

Core Design. (1996). Tomb Raider: Lara Croft [PlayStation & Saturn]. Digital game published by Eidos Interactive.

Crammond, Geoff. (1986). The Sentinel [Micros]. Digital game published by Firebird Software.

Distinctive Software. (1990). Stunt Cars [Micros]. Digital game published by Brøderbund.

Distinctive Software. (1991). 4D Boxing [PC & Micros]. Digital game published by Mindscape International.

Donovan, T. (2010). Replay. The History of Video Games. Lewes: Yellow Ant.

Dynamix. (1990). Red Baron [PC]. Digital game published by Sierra On-Line.

Dynamix. (1990). Red Baron [PC]. Digital game published by Sierra On-Line.

Electronic Arts. (1991). Chuck Yeager’s Air Combat [PC]. Digital game published by Electronic Arts.

Eskelinen, M. (2001). The Gaming Situation. Game Studies: The International Journal of Computer Game Research, 1, 1, 2001. Retrieved September 9, 2019 from www.gamestudies.org/0101/eskelinen/.

Extended Play Production. (1993-1994). FIFA International Soccer [Genesis, SNES & 3DO]. Digital game published by Electronic Arts.

Foucault, M. (1969). L’Archéologie du savoir. Paris: Gallimard.

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/Knowledge. Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972-1977. London: The Harvester Press.

Guido, L. (2010). From Broadcast Performance to Virtual Show: Television’s Tennis Dispositive. In F. Albera & M. Tortajada (Eds.), Cinema Beyond Film. Media Epistemology in the Modern Era (pp.193-214). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Incentive Software. (1987-1988). Driller [Micros]. Digital game published by Incentive Software.

Järvinen, A. (2002). Gran Stylissimo: The Audiovisual Elements and Styles in Computer and Video Games. In Franz Mäyrä (Ed.), Proceedings of Computer Games and Digital Cultures Conference. Tampere: Tampere University Press.

Jones, M. (2007). Vanishing Point: Spatial Composition and the Virtual Camera. Animation, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp.225-243.

Kent, S.L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games. New York: Three Rivers Press.

Krichane, S. (2015). King’s Quest : Queen’s Quest ? In F. Lignon (Ed.), Genre et jeux vidéo/ Gender and Videogames, Lyon : Presses Universitaires de Lyon, pp.69-81.

Krichane, S. (2018). La Caméra imaginaire. Jeux vidéo et modes de visualisation. Genève : Georg. Retrieved April 15, 2021 from https://serval.unil.ch/en/notice/serval:BIB_336F3BC9ED5F.

Krichane, S., & Rochat, Y. (2018). Pour une analyse des discours sur le jeu vidéo: l'exemple des "cinématiques". Décadrages. Cinéma à travers champs, No. 39, pp.93-118. Retrieved April 15, 2021 from https://serval.unil.ch/resource/serval:BIB_0E47347F0E51.P001/REF.

Lowood, H., & Nitsche, M. (Eds.) (2011). The Machinima Reader. Cambridge/London: MIT Press.

Lucasfilm Games. (1988). Battelhawks1945 [PC]. Digital game published by Lucasfilm Games.

Manovich, L. (2001). The Language of New Media. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Mirrorsoft. (1987-1988). Falcon [PC & Mac]. Digital game published by Mirrorsoft.

Möring, S., & de Mutiis, M. (2019). Camera Ludica: Reflections on Photography in Video Games. In Fuchs, M., & Thoss, J. (Eds.). Intermedia Games--Games Inter Media: Video Games and Intermediality. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, pp. 69-94.

Nintendo Research and Development 1. (1985). Super Mario Bros. [NES]. Digital game published by Nintendo.

Nintendo Research and Development 1. (1996). Super Mario 64. [Nintendo 64]. Digital game published by Nintendo.

Nitsche, M. (2008). Video Game Spaces: Image, Play, and Structure in 3D Worlds. Cambridge/London: The MIT Press.

Novagen Software. (1987). Backlash [Amiga & Atari ST]. Digital game published by Novagen Software.

Noyer, J. (2001). La presse vidéo-ludique : le jeu de la médiation. Médiamorphose, No. 3, pp.69-70.

Ocean Software. (1989). Voyager [Amiga & Atari ST]. Digital game published by Ocean Software.

Papyrus Design Group. (1989). Indianapolis 500: The Simulation [Amiga & PC]. Digital game published by Electronic Arts.

Pelletier-Gagnon, J. (2018). ‘Very much like any other Japanese RPG you’ve ever played’: Using undirected topic modelling to examine the evolution of JRPGs’ presence in anglophone web publications. Journal of Gaming and Virtual Worlds, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp.135-148. Retrieved April 15, 2021 from https://doi.org/10.1386/jgvw.10.2.135_1.

Perron, B. & Therrien, C. (2009). Da Spacewar! a Gears of War, o come l’immagine videoludica è devintata più cinematografica. bianco e nero, No. 564, pp.40-50.

Perron B. (2014). Conventions. In M.J.P. Wolf & B. Perron (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Video Game Studies (pp.44-82). New York/London: Routledge.

Perron B., Montembeault H., Morin-Simard A., & Therrien C. (2019). The Discourse Community’s Cut: Video Games and the Notion of Montage. In Fuchs, M., & Thoss, J. (Eds.). Intermedia Games--Games Inter Media: Video Games and Intermediality. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, pp.37-68.

Picard, M. (2010). Pour une esthétique du cinéma transludique: figures du jeu vidéo et de l'animation dans le cinéma d'effets visuels du tournant du XXIe siècle, PhD diss., University of Montréal.

Picard, M., & Fandango, G. (2008). Video Games and their Relationship with Other Media. The Video Game Explosion: A History from Pong to Playstation and Beyond. Westport: Greenwood Press, pp.293-300.

Polygames (formerly Sterling Silver). (1992). PGA Tour Golf II [Genesis]. Digital game published by Electronic Arts.

Poremba, C. (2007). Point and Shoot: Remediating Photography in Gamespace. Games and Culture, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 49-58. Retrieved 14 July, 2021 from doi:10.1177/1555412006295397.

Raynal, Frédérick. (1992). Alone in the Dark [PC]. Digital game published by Infogrames.

The Assembly Line. (1992). Stunt Island [PC]. Digital game published by Walt Disney Computer Software.

Rochat, Y. (2019). A Quantitative Study of Historical Video Games (1981-2015). In Alexander von Lunen (Ed.), Historia Ludens: The Playing Historian, Routledge, pp.3-19.

Sega AM2. (1992). Virtua Racing [Arcade]. Digital game published by Sega.

Sierra On-Line. (1984-1998). King’s Quest [Micros & PC]. Digital game published by Sierra On-Line.

Taylor, N. (2016). Play to the camera: Video ethnography, spectatorship, and e-sports. Convergence, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp.115-130.

Taylor, T. L. (2012). Raising the Stakes: E-sports and the Professionalization of Computer Gaming. Cambridge/London: MIT Press.

Therrien, C. (2015). Inspecting Video Game Historiography Through Critical Lens: Etymology of the First-Person Shooter Genre. Game Studies: The International Journal of Computer Game Research, Vol. 15, No. 2. Retrieved September 9, 2019 from www.gamestudies.org/1502/articles/therrien.

Thomas, D. & Haussmann, G. (2005). Cinematic Camera as Videogame Cliché. In S. de Castell & J. Jenson (Eds.), DiGRA 2005 Conference: Changing Views--Worlds in Play, Vancouver: DiGRA. Retrieved September 9, 2019 from www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/06278.52285.pdf.

Wolf, M.J.P. & Perron B. (Eds.) (2001). The Routledge Companion to Video Game Studies. New York/London: Routledge.

Wolf, M.J.P. (2001). The Medium of the Video Game. Austin: University of Texas Press.