Parasocial Relationships in Social Contexts: Why do Players View a Game Character as Their Child?

by Nansong ZhouAbstract

Many Chinese players view the game character in Travel Frog as their child. Using Travel Frog as an example, this paper explores the meaning constructed by players through their parasocial relationship with the ‘frog’ and the social context of this construction. The author conducted in-depth interviews with 20 players from first-tier cities in China, and the findings are based primarily on a thematic analysis of the data. This study finds that the reasons young Chinese players view the frog in the game as their child are deeply rooted in their conceptions of their ideal lifestyle and ideal parent-child relationship. Some players project their desire to live freely through their parasocial relationship with the frog, and express their expectations for an ideal parent-child relationship. This study aims to go beyond the limited perspective of individual gratification to understand the social and cultural reasons behind the formation of the player-game character relationship and game culture in a Chinese context.

Keywords: Urban China, parasocial relationship, young individuals, parent-child relationship, lifestyle

Introduction

Digital games are a popular area of academic interest in the field of communication. The question of whether a digital game is defined by a specific type of media consumption or by the practices of the player is still an open question in game research. Existing research focuses on the consumption of games, and pays little attention to players’ concrete practices (Shaw, 2010). One of the crucial aspects of game practice is the interaction between players and game characters. Studies focusing on parasocial interaction -- the interaction between the audience and media characters -- and parasocial relationships -- the long-term relationship between the audience and media characters within a game -- often measure the audience's preference for game characters, and often characterize parasocial relationships based on individual gratification. However, little is known about the social and cultural motivation behind users’ practice (Giles, 2002; Jin & Park, 2009; Kavli, 2012). Moreover, existing research concerning parasocial interactions or relationships often defaults toward conceiving of parasocial relationships as friendships, which may prevent researchers from capturing other types of player-character relationships. In recent years, as the variety of digital games has grown and the lifestyles of young people have changed, the categorization of game characters has become more diverse. Some scholars have emphasized the need to broaden the conceptual boundaries of parasocial relationships to include other types of relationships (Bond, 2020; Schramm & Hartmann, 2008; Tian & Hoffner, 2010). To fill these gaps, this article takes Travel Frog, a mobile game that became a sensation in China in 2018, as a case study and considers parasocial relationships as a media practice embedded in the daily life of players to explore the social and cultural reasons behind this practice and its meaning to society.

As young urban dwellers in China experience changes in society and family due to forces such as globalization and individualization (Yan, 2009), some of their opinions about their lifestyle and family relationships are reflected in their understanding of the games they play. This study conducted in-depth interviews with 20 young players living in first-tier cities in China. Based on the thematic analysis of the interview data, this article demonstrates that Chinese players’ parasocial interactions in Travel Frog, in which the frog in the game is viewed as a child, is deeply related to their ideal lifestyle and ideal parent-child relationship. We find that 1) some players project their desire to live freely through their parasocial relationship with the frog, and 2) young people express their expectations of an ideal parent-child relationship through game culture.

Contextualizing Parasocial Phenomena

Although parasocial interactions and parasocial relationships have long been considered interchangeable ideas, recent research has offered productive distinctions between the concepts (Dibble, Hartmann, & Rosaen, 2015; Liebers & Schramm, 2019). Parasocial interactions are interactions between an audience and characters in media during media consumption. In contrast, parasocial relationships are a form of long-term relationship between a viewer or user and character, which may begin to develop during consumption, but also extends beyond the media exposure. In this article, we follow Liebers and Schramm’s usage of parasocial phenomena (Liebers & Schramm, 2019) to summarize all parasocial responses of audiences to media characters, including their distinction between parasocial interactions and parasocial relationships.

After the notion of parasocial interactions was first proposed by Horton and Wohl, scholars did not show much research interest in the concept as a media phenomenon until uses and gratifications theory was proposed (Giles, 2002; Gurevitch, 1949). Based on that theory, although it is still controversial whether parasocial phenomena constitute a media phenomenon or a psychological phenomenon, many researchers analyze it from the perspective of individual gratification, arguing that parasocial interactions/relationships compensate for and substitute real-life interactions, and that individuals seek to obtain certain kinds of satisfaction from it (Baek, Bae, & Jang, 2013; Giles, 2002; Greenwood, 2008; Jin & Park, 2009; Levy, 1979; Rubin, 1983; Rubin, Perse, & Powell, 1985). In addition, researchers often measure users’ impressions of game characters and experience (Ekman et al., 2012; Schramm & Hartmann, 2008; Weber, Behr, & Demartino, 2017), but little is known about how the construction of social context influences players’ experience. The media and the content of the media have become part of social life, and cultural context is necessary for understanding some media practices (Daniel Pargman; Peter Jakobsson, 2008; Deuze, 2011; Galloway, 2004; Montola, 2012). Some scholars have pointed out that cultural context and audience members’ values, attitudes, personal experiences, etc., influence parasocial interactions (Newcomb & Hirsch, 1983) because individuals’ understanding of the parasocial phenomenon is based on their understanding of the social relationship in a social context. It is also crucial to describe the interaction between audience members and media in the social contexts of their everyday lives (Takahashi, 2002).

Additionally, from the method used to measure parasocial interaction with newscasters proposed by Levy (1979) to the Audience-Persona Interaction Scale developed by Auter and Palmgreen (2000), scholars have attempted to analyze individual motivation and its influence on how people regard a parasocial relationship as a friendship. However, some researchers have noted that the tendency to limit parasocial relationships to friendships may prevent researchers from capturing other types of player-character relationships (Bond, 2020; Schramm & Hartmann, 2008; Tian & Hoffner, 2010). For example, in many love games (LVG), such as EVOL×LOVE, Memories Off, and Tokimeki Memorial, players are encouraged to view game characters as lovers. In animal stimulation games, such as Pokémon, some players view game characters as pets. It is difficult to evaluate the emotional involvement of players in this game through measures of friendship or “like, neutral, or dislike” ratings. Hence, this article seeks to place the parasocial relationship in Travel Frog in the Chinese social context. We aim to go beyond the limitations of uses and gratifications theory and the tendency to regard parasocial relationships as friendships to explore the social and cultural factors underlying these relationships and their relevance to society.

Individualization in Urban China

Individualization in urban China is an ongoing social process that will continue for a long time; this process is part of the dissolution of traditional patriarchal society and the improvement of the status and power of individuals. In China, the traditional patriarchal society is based on filial piety and renqing(favor), and the improvement of an individual’s status is closely related to the individual's perceived effort in meeting social obligations.

Filial Piety and Renqing

The traditional Chinese family is structured by the concepts of filial piety and fraternal duty. The filial piety advocated by Confucianists is the core of traditional Chinese culture and the basis of China’s ethical order and social structure (Cheung, 2014; Hwang, 1999; Yan, 2009; Zhou, 2008). Filial piety is a manifestation of the idea of requiting renqing (favor). Renqing is the social expression and exchange of emotional and material goods, including gifts and favors, in Chinese society (Wang, 2012). China is a renqing society, which means that if you receive a favor, you have to pay it back. This philosophy is rooted in Chinese culture and is related to ethics, human communication and family. Based on the principle of requiting favor, traditional Chinese culture emphasizes that the old are superior and the young are inferior; the old have more power and higher status, and the younger generation should respect and be filial to the older generation (Dong, 2015; Zhou, 2008). The younger generation must not only take good care of the older generation, but also carry out older people’s wishes to exhibit filial piety (Xiao, 2000). Moreover, taking care of one’s parents is not sufficient to repay the considerable favor bestowed by them; young people raising their own children as their parents did is a form of appreciation for their parents (Yan, 1996). According to the concept of filial piety, an individual belongs to his or her parents, and the individual’s life is the continuation of his or her parents’ lives. Therefore, some people place their expectations on their children: the younger generation must inherit the older generation’s ambition instead of doing what they want to do (Hwang, 1987, 1999; Yan, 2009).

However, two movements critical of Confucianism arose in the 1910s and in the 1970s, weakening the culture of patriarchal authority and filial piety (J. Liu, 2017). During the first movement, reformists thought the hierarchical family with great power prevented the state from uniting all classes of society against the enemy, which resulted in defeat during the Opium War. This movement led to limited progress among bourgeois and intellectual families. In the second movement, in order to improve people’s loyalty to the state, the communists wiped out family elders’ power and recreated a new political structure through the Cultural Revolution and other activities. Then, under Maoist socialism, the traditional social relations centered on the family were criticized as feudalistic, and a new universalistic comradeship was created to guide not only interactions among individuals, but also the relationship between the individual and the state (Vogel, 1965). Mao waged a massive class struggle and prioritized loyalty to the party over filial piety. This movement impacted the former patriarchal culture and family structure, suppressing the power of family elders and strengthening citizens’ loyalty to the state (Hsu, 1948; J. Liu, 2017). Moreover, the introduction of Western values and modernization also eroded filial obligations (Croll, 2006). Nevertheless, China’s core as a renqing society has not changed, and the concept of requiting favor has been maintained. Moreover, to reduce the pressure on the state to provide social welfare and public services, China has introduced policies and laws to define adult children’s responsibility to take care of their parents, which reinforces filial norms (J. Liu, 2017). Since filial piety is approved by the government but the power of the older generation has weakened, conflicts tend to arise in parent-child relationships. Parents may ask young people to do one thing to fulfill filial norms, but young people are becoming less willing to comply because they believe their parents have the same status as them and do not have the right or power to give orders. Although in some families, filial obligation has transformed into mutual support based on reciprocity (Croll, 2006; J. Liu, 2017), the requirement of obedience in filial piety still exists in some Chinese families.

Enterprising Individuals and Social Pressure

Changing attitudes toward filial piety mean that individuals no longer live under the shadow of their ancestors (Hsu, 1948). Together with other factors, this has influenced modern lifestyles in urban China; most clearly represented by enterprising individuals (Yan, 2010). Young people work hard to save money to purchase a house and car, and get married as soon as possible.

Before the 1980s, people who graduated from college would have a job for life, with a decent paycheck, good benefits, and occasional promotion -- although they did not have personal choice or autonomous rights (Hoffman, 2006). In the planned economic system, the centralized and unified arrangement of the planners reduced competition for labor, so many individuals did not experience the pressure of competition and enterprise (Cai, Park, & Zhao, 2011). In 1984, the Communist Party started opening up the economy, introducing a market competition mechanism to realize the optimal allocation of resources and produce maximal social benefits (Hoffman, 2006). Similarly, a series of reform measures to marketize housing, medicine and education began in the 1990s; these reforms absolved the government of responsibility for individual development and placed it on individuals themselves (Cai et al., 2011; Yan, 2010, 2009).

Urbanization’s various social reforms and the introduction of Western values into Chinese culture have led to a considerable increase in individuals who pursue personal freedom, prioritize individual rights and seek out self-worth. These enterprising individuals wish to make their own decisions, manage their careers, plan their futures and construct a self. They also experience unprecedented social pressure. The problem of settling in the city caused by the household registration system (hukou) and the problem of caring for parents force young people to abandon their ideals and face reality (J. Liu, 2017; Yan, 2009). Although the government has eased the restrictions on population mobility, the hukou system has been retained to manage urban resources. Only citizens who have local hukou in the city have access to local services and welfare, including public education and medical insurance -- causing housing, marriage and hukou to be closely interrelated (Afridi, Farzana; Li, Sherry Xin; Ren, 2015; Chan, 2009; Chan & Buckingham, 2008). Housing and hukou have become symbols of eligibility to access urban resources, which is also one of the standards for choosing a spouse (Lui, 2017; Nie & XING, 2011). “Squeezed between the increasing market competition on the one hand and the decreasing support from family, kinship, and state institutions on the other, many Chinese individuals suffer from various degrees of mental illness” (Yan, 2010, p505-506). With the pressure of the high cost of living and fierce competition, they attempt to search for identity but have to work hard, take a job they do not like or even accept the 996 working hour system (work from 9:00 am to 9:00 pm 6 days per week, i.e., 72 hours per week)(King, 2017; Yuan, 2017). Yan (2010) pointed out that in the face of uncertain risk and decreasing national support, Chinese individuals have no choice but to live a "life of their own" with a lack of genuine individuality. It is in this kind of social context that the mobile game Travel Frog thrived. Many players said playing this game helps them to release their pressure and stress in real life.

Overview of Travel Frog

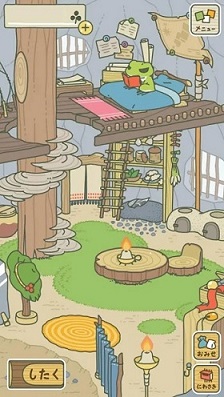

In 2018, the mobile game Travel Frog was ranked first for more than two weeks in the Chinese App Store (W. Zhou, 2018). It was formerly one of the most famous single-player games in China. Travel Frog is a life simulation game developed by Hit-Point Co., Ltd., a game company in Japan. It is easy to play and has only one game character, a cute green frog, and it uses bright and natural colors and simple animation. There are only three scenes in the game: the hut, the shop, and the garden. In the hut, the frog can sleep, eat, read and sharpen a pencil, but players cannot do anything else except pack up and enter the shop. In the shop, players can buy supplies. Goods with higher prices increase the possibility of the frog traveling somewhere it has never been. If players buy nothing, the frog is unaffected.

Figure 1. The scene of the hut.

Figure 2. The interface for packing up.

Figure 3. The interface for the shop.

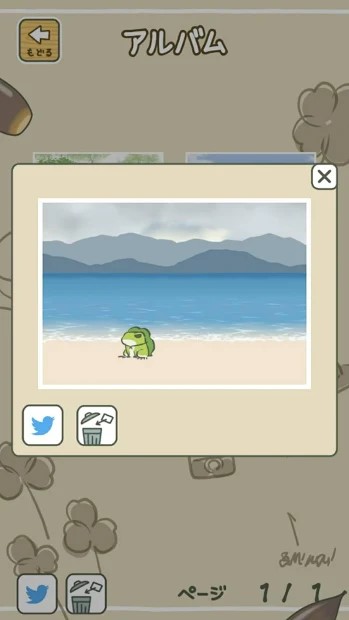

In the garden, players can collect clover leaves that can be used to buy things, and sometimes, insects will visit and the player can entertain them. Moreover, there is a mailbox where the player can receive postcards sent by the frog.

Figure 4. The scene of the garden.

Figure 5. The postcard interface.

There are only a few functions in the game: packing up, buying, collecting clover leaves, entertaining visitors and receiving postcards. Players do not know when the frog goes out or where it travels to, nor do they have any control over the frog’s destination. Most of the time, the only thing players can do is collect clover leaves to buy goods in preparation for the frog’s travels, which require minimal but potentially entail a large amount of emotional involvement. The game has attracted many young Chinese urban people, especially women. Travel Frog became a social sensation not only because of its gameplay and animation style, but particularly because of the kind of connection players fostered toward the game’s central character. The phenomenon in Travel Frog of viewing the frog as a child has also been reported by many authoritative media sources, including the BBC, The New York Times and China Daily (Karoline Kan & Ramzy, 2018; W. Zhou, 2018). Chinese players’ game experience in Travel Frog reflects certain social and cultural characteristics of China. While playing the game, many Chinese players regard the frog on the phone screen as their son to take care of. However, according to an interview with the designer of Travel Frog[1], in Japan, the frog in the game is more likely to be viewed as the husband in the family because husbands usually go on a business trip and sometimes bring home local products. These perceptions of the game character’s behavior and identity reflect cultural and social differences. This difference inspired us to place Chinese players' parasocial interaction in a Chinese social context to understand the reason for this game behavior.

According to Aurora Mobile (2018), 43.6% of Travel Frog players are between 20 and 24 years old. In addition, approximately 70% of Travel Frog players are female, and players from first-tier cities account for the largest proportion. Thus, our interview focused on young female players in first-tier cities.

Methodology

Research Methods

We performed a thematic analysis of interview data collected in order to study players’ experience playing Travel Frog. Most existing research on parasocial phenomena adopts a quantitative approach to measure parasocial interaction in digital games (Banks & Bowman, 2014; Jin & Park, 2009; Kavli, 2012; Mccutcheon, 2002; Weber et al., 2017). Although these studies identified several factors correlated with parasocial interaction, the quantitative method presents some obstacles to an in-depth examination of the complexities of life, and the social context behind player practice. Using quantitative data can limit players’ interpretation of their game experience, especially their perception and understanding of game characters and their relationship with them; as well as the description of social context. Thus, we chose a qualitative approach, which seemed necessary to understand why Chinese players view the frog as their child.

This study involved semistructured interviews with players to collect data and analyze the data through thematic analysis. After sorting out the interview materials, we coded the important statements using various tags -- pressure, filial piety, responsibility, relaxation, freedom and yearning, etc. -- and extracted the themes of parent-child relationship, lifestyle, spiritual sustentation, etc., from these statements.

Sample and Interviews

From May 2019 to July 2019, a recruitment advertisement was posted in Travel Frog discussion groups in WeChat, Weibo and QQ, the three most important social platforms where Travel Frog players discuss the game. Each participant received 40 RMB (worth approximately $ 5 U.S.) as compensation. Due to the decline in popularity of Travel Frog and the number of the players at the time the study was conducted, we also requested that the interviewees ask their friends who played Travel Frog to take part in the interview. This research involved in-depth interviews with 20 Chinese players of Travel Frog. We organized and collated the audio recordings, which included more than 30 hours in total during the period between September and October in 2019.

We conducted semi-structured interviews via telephone or WeChat online phone. The young interviewees consisted of 14 female players and 6 male players, who lived in Beijing, Shanghai, Chongqing, Chengdu, Tianjin and Xiamen. Fifteen interviewees (14 females and 1 male) thought of the frog as their son, and the others (5 males) thought of the frog as just a virtual character, not a son or a pet.

The semi-structured interview outline included three main parts: basic information, the motivation for and experience of playing Travel Frog, and individual living status and interpersonal relationships. During the basic information part, personal information including age, job, city of residence, digital game preferences and game-playing history was collected. In the second part, interviewees answered questions such as "How did you find out about this game?", "Why did you play it?", "What did you think of the frog in the game?", "Did you ever view it as your pet/friend/partner/son?", "Why or why not?", and "Have you ever missed it?" The third part of the interview was based on interviewees’ answers in the previous part to inquire into their real-life situation. For example, if the interviewee said Travel Frog made them feel relaxed, we would ask whether he/she felt stressed in reality and the source of the stress. If they mentioned they liked the lifestyle of the frog in the second part, we would ask them to evaluate their current life and describe their ideal lifestyle, etc. The specific interview was based on the interviewees' answers, and the interviewer continued asking questions to inquire more deeply into the interviewees’ answers.

Findings

According to the interview materials, we found that most interviewees initially downloaded the app and began to play in order to follow a social trend and share a common experience with friends. They did not regard the frog in the game as a son at first, but came to do so over time as they played the game. After repeated encounters with the frog, interviewees reported that they admired and appreciated the frog’s depicted lifestyle, and how it seemed to relate to players. The emotional involvement and understanding of the frog did not arise from the specific interaction in the game but, rather, the interpretation and imagination of the players. Moreover, the players’ emotions toward and opinions of the frog were not limited to the Travel Frog game, but extended to life beyond the game. They projected their hopes of living freely on their relationship with the frog, and wished to have similar relationships with their parents or children, allowing the players to think of the frog as their child. Players formed a stable and long-term relationship with the frog, which is a typical parasocial relationship. We illustrate two reasons why players viewed the frog as their child: to project the hope of living freely and to express their expectation of an ideal parent-child relationship.

Projecting the Hope of Living Freely

Since the reform of the market mechanism in China, young people have faced more certain risks, but the government has not implemented a complete welfare system and social security system to support individual development. The individual must rely on himself or herself.

“In real life, many people are full of worries, just like most people have one kind of lifestyle: work hard and save money to buy a home to settle down. We are facing this pressure…” (Female interviewee 4, 20 years old, Chengdu).

With the introduction of economic rationality, the status and function of property have substantially improved, and property ownership has become one of the most important components of a good life (Wu, 2016). The role of the economic foundation in marriage is becoming increasingly obvious in both rural and urban areas. The bride price in rural areas is increasing yearly. In urban areas, prospective partners are expected to have a car and a house before marriage (Nie & XING, 2011). Moreover, for most young people who are not local inhabitants in a city, if they want to obtain local urban hukou, which gives access to public services and social welfare, they are required to purchase a home (Lui, 2017; Nie & XING, 2011). High prices force these individuals to work hard and accept overtime work to maintain job stability in the face of unemployment and fierce competition (B. Liu, Chen, Yang, & Hou, 2019). However, young people study hard or work overtime not only because of the high cost of living and development costs, but also because of their expectations for themselves.

“Q: Why do you think you are stressed?

A: I think most of the pressure comes from myself and surroundings. Just like the final exam, I don’t want to muddle through my work, so I will force myself to study hard, even some unimportant subjects. Then, actually, sometimes it is not easy to finish my goal I set for myself, so I would feel stressed……and the pressure from my peers also would make me feel dysphoric. I would start to feel that they were better than me…”(F2, 21 years old, Beijing).

“Q: Do you think you are relaxed in daily life?

A: I think I am usually restricted by the goals set by myself. But I think as a young person, it is normal to have this restriction, and we should be aspirant. I feel that my stress comes from essentially myself” (F4).

F2 and F4 both suggested they set goals for themselves, but were simultaneously restricted by these goals. Most of the pressure they experience comes from these goals, and thus, themselves. This perception is consistent with Yan’s opinion (2010) that Chinese individuals force themselves to live a "life of their own" with a lack of genuine individuality. With the development of the market and competitive mechanisms and the reform of the education system, the power of young people is amplified, and their status in society is improving. They are calculating, proactive, self-disciplined and believe that they should live freely and independently -- that they deserve to pursue a good life and fulfilling work on their own (Yan, 2010, 2009). These enterprising individuals try to construct a self and achieve value by doing what they like doing.

“We are facing the pressure from settling down in real life, but the frog in Travel Frog doesn’t worry about these things…” (F4).

Compared with the lives of these young people, the life of the frog in Travel Frog is much more careless, free and independent. In the game, the frog can do anything it likes at any time, including traveling, reading and sleeping. Players prefer this carefree, independent and free lifestyle to their specific life context. No one can control or intervene in the frog's life, not even the player. For many players, the frog seems to do as it wishes; it does not follow convention or care about others’ judgments. It has a free and independent lifestyle that represents the ideal for many young players.

“It is an attractive frog. It always has its own life and own circle. There is a kind of sense of distance between it and me, which makes it very attractive……at present, I yearn for its life. I think when I am young, this kind of life is better, which means I won’t be locked in one place, one person or one thing. I wish to go to more places and meet more people, which may help me feel a sense of fulfillment…” (F5, 21 years old, Tianjin).

F5 longs to live a life like the frog because there is a meaningful distance between the frog and others that prevents mutual interference and unnecessary communication. Moreover, by maintaining distance, the individual does not rely on a single person and can be independent and free. Not being restricted by one thing or one person would bring more opportunities to understand the world and construct the self.

“Q: Why do you yearn for the life of the frog?

A: Because I think that kind of life is very cool, and it breaks the success-driven life routines. I particularly object to the opinion that young people should get married at a certain age, and we should save money to a certain level by a certain age. I believe there is no routine in life, and no one can tell me what I should do. I think the only thing I should do is what I want to do” (F6, 19 years old, Beijing).

F6 seeks to find and construct herself on her own, and she argues that there should not be a mainstream lifestyle that people are required to follow. She wishes to live her life the way she wants to live it, like the frog in the game, breaking the routine and enjoying life freely. Nevertheless, F5 and F6 conceded that young people would not be able to live this kind of life all the time:

“It is impossible to always live like the frog in Travel Frog. If you do not follow the mainstream, for example, you will not get married at the age that people should get married, you will not withstand the pressure from society. I don’t think there will be serious consequences of not getting married in the future, but it is difficult to withstand the pressure from doing different things from the rest at a certain age” (F5).

“Q: Why do you like this life but do not expect to live this life?

A: Because it is quite difficult to achieve it. There are a lot of matters of reality. For example, if you love travel, what about your parents? Who will take care of them? If you travel outside every day, you will not have a stable relationship. How do you make money? Will you save money? There are a lot of problems in reality” (F6).

F5 pointed out that the mainstream lifestyle limits the development of young people. The older generation outlines a timetable of their children’s lives -- including when to get married and buy a home -- according to their experience, which restricts young people’s development and pursuits (Wu, 2016). Based on this timetable of life, young people have to study hard to get a stable job and then work hard to make money to purchase a home and get married as soon as possible before they turn 30. F6 suggests that she is unable to live the free and careless life she desires because many practical problems limit her, including taking care of her parents, saving money and getting married. She cannot afford the price of living that lifestyle even though she prefers it. These practical problems are based on the idea of the Chinese family, and relate to the duty young people have in the family: connecting the older and the younger generations. The family is the basic unit of Chinese society, and the traditional social hierarchy and power structure were derived from the family power structure by Confucianists; thus, Chinese culture emphasizes family inheritance and reproduction (Xiao, 2000). There is a Chinese saying that of all who lack filial piety, the worst are those who have no children. Individuals must get married and have children to achieve filial piety, which is considered the mainstream lifestyle. If young people do not get married before age 30, the older generation becomes impatient and forces them to go on blind dates; behavior that does not factor the young person’s will (To, 2013). In addition, the whole family feels belittled and humiliated by society because the mainstream culture shames those who aren’t married with a car and a house by a certain age.

Many players know that although they yearn for the frog’s lifestyle, they are unable to live like the frog due to the practical problems they face in real life. The pressures of reality force them to follow the mainstream However, they project their desires onto the frog and hope that the frog can live freely as they wish to instead of giving up completely.

“Q: Why do you view the frog as your child?

A: This is a life simulation game. Many people have this idea of placing a lot of desires on it. This seems like an absolute statement, but I remember at that time many players called it “frog son…” (F6).

F6 pointed out that many players project their desires, especially of living freely, on the frog by viewing the frog as their child. In China, parents usually hope that their children will fulfill their unfulfilled desires and live a happy life as defined by their parents. There is an expectation of living out the ideal through the Chinese parent-child relationship. This expectation comes from the parents’ love for their children on the one hand, and on the other, it is rooted in traditional filial piety and the idea of the family. In the traditional Chinese context, the child is part of the parents and the life extension of the older generation, representing the family inheritance and hope. For example, parents who came of age during the Cultural Revolution of 1966-1976 suffered a lack of educational opportunities themselves, so they sought to give their children the best education that they could afford (Liu, 2007). Under the influence of Confucian filial piety, children are expected to fulfill their parents' expectations, win honor for the family, and reduce their parents' stress and anxiety (Leung & Shek, 2011).

“My parents have left something incomplete when they were young, so they want me to finish it. But, I don’t want to do that…” (F1, 22 years old, Beijing).

For young Chinese players, living a carefree and free life is a hope that is nearly impossible to achieve. However, they do not have a child in real life to place their hopes on, so the frog in Travel Frog, which they consider their child, becomes an object through which to live out their ideal. By projecting their hopes onto it, players can easily turn the game character into their child.

Expressing their Expectations of an Ideal Parent-child Relationship

Although filial piety has been criticized by scholars and governments in modern China, it continues to have a profound influence on the parent-child relationship. In China, young people believe that the parent-child relationship should be equal and respectful and that privacy and distance should be maintained. However, in reality, the relationship is quite the opposite -- it is difficult to achieve an equal parent-child relationship.

“Q: Do you think an unequal relationship between parents and children is normal?A: I don’t think so. I think it should be equal. But, in China, there are few families with this equal relationship. At least my family is very unequal…” (F1).

“In my opinion, children are supposed to be on an equal footing with their parents, but in real life, they are not…” (F4).

F1 and F4 argue that there are few families that have an equal parent-child relationship. Moreover, F1 notes that this unequal status is related to parental favors:

“Because your parents pay a lot. What you eat and what you wear are all given by your parents, even your life. Your parents help you live in the world, so they have more rights and higher status. Your parents give you things that you need for the first half of your life or you have nothing. There is an old Chinese saying: ‘When you eat food from others, you will speak a good word to others. When you get something from others, you will be controlled by others’” (F1).

F1 states that some parents’ generosity gives parents higher status over their children. This opinion reflects the practice of renqing in Chinese society. Requiting favors is the basis of social relationships in China, involving the exchange of interests and emotional engagement, and filial piety is the act of requiting parents’ favor (Zhai, 2004). During the process of owing and repaying a favor, the giver is in a position of power, and the receiver has to serve the giver to show appreciation, as is expressed in an old Chinese saying: “Little help brings much return.” If recipients of a favor do not reciprocate in some way, they will have a sense of guilt. In some Chinese families, parents expect to be requited by their children, as in the old Chinese proverb, “Bring up sons to support parents in their old age.” The exchange of resources can be valued; however, the favor is a matter of perception and is difficult to measure (Cheung, 2009; Wang, 2012; X. Zhou, 2008). (Zhai, 2004). Due to the fuzzy nature of favors (Biyang, 2011), there is no limitation or standard regarding the resource or the date of repayment; so for some parents, it is reasonable for children to obey their requirements and rules.

“My parents set a lot of rules to restrict me, even with what I wear. If I buy clothes for myself, my mom will be unhappy because she thinks the daughter’s clothes should be bought by the mother instead of the daughter…” (F1).

“I used to have fierce quarrels with my parents because they made a lot of rules for all the necessities of life, including clothing, eating, and living…” (F3).

F1 and F3 indicate that their parents take complete care of them and regulate all aspects of their children’s lives. In addition, some parents not only have requirements for the quotidian matters of daily living, but also intervene in fundamental choices.

“Even with my choice of university and major, I have to follow their opinion…” (F1).

“Sometimes I feel disappointed by my family. For example, my parents force my little brother to study. My brother is good at sports, but they believe study is the only way to rise…” (F4).

In the opinion of some Chinese parents, young people should obey the life schedule established by their parents, which may limit the younger generation’s exploration of the self and life; therefore, some young people want to end their dependence on their parents. They emphasize the role of financial independence in living freely and independently, and they prefer to rely on themselves rather than their parents because they believe it is a beneficial way to escape from the interference of the mainstream represented by their parents.

“…because I do not want to ask my parents for money. You have to live by yourself. Living requires money. If you need money, you must find a job to make money…” (F1).

F1 is unwilling to receive money from her parents because she believes it puts her deeply in her parents’ debt. Because of this debt, her parents may restrict her activities and life, which would affect her freedom. Therefore, she works several part-time jobs to make money and try to achieve financial independence. Some of the interviewees pointed out that financial independence makes the relationship with their parents equal, which gives them more freedom, like the game character in Travel Frog.

These young people experience an ideal parent-child relationship in their parasocial interaction with the frog. This parasocial interaction in Travel Frog is different from that in other games. While most games give immediate feedback based on the player's actions, the interaction with the traveling frog does not. In Travel Frog, the player has no idea whether, when or how his or her efforts will be responded to. This delayed feedback gives the player a feeling that they cannot control the frog and that the frog has its own free will. It acts on its own terms, which is exactly what the player desires in a parent-child relationship.

“I named the frog with my English name…The frog is like my son, and it is also like myself…it has its things to chase after …” (F1).

F1 further indicated that there is little restriction and interference between the frog and the player, so the frog has room and time to do what it likes. The frog does not have to consider how to repay the favors bestowed by the player, and the player does not exert much effort on the frog's behalf either. F1 expressed the desire that her relationship with her parents would be like the interaction between her and the frog. Since F1 was a child, she has followed her parents’ strict rules and has had almost no autonomy. She has a constant desire to get out of this relationship that creates so much pressure, and she has taken part-time jobs to achieve financial independence and rarely connects with her parents. In contrast, the parasocial interaction with the frog makes F1 feel relaxed. With the sense of distance between her and the frog, she does not feel a burden. Although she plans to not have children, she, as a daughter of her parents, still desires the ideal parental relationship and projects this desire onto the frog.

“Q: Do you want a child like the frog in Travel Frog?

A: Yes, because I want to be independent, so I want my children to be independent, too. It is good that the child sometimes sends a postcard and does not usually visit. As a child of my parents, I also hope that my parents can feel the same way and not wish me to always be with them…” (F4).

The ideal parent-child relationship F4 hopes for is one of distant connection, and it encompasses her status not only as a child but also as a parent and the attitudes of her parents and children toward her. Her view of the frog as a child shows her approval of the status and behavior of the mother and child in the player-frog model. The player expects her mother to treat her as she treats the frog and to live as freely as the frog. The player also expects her children to be able to live like the frog and wants to treat her children as she treats the frog.

The interaction with Travel Frog offers players an archetype of the ideal parent-child interaction. Some young people express their ideal parent-child relationship through this interaction. The existing literature demonstrates that in China, previously, hopes for a free life, love and an easy job were limited, but during modernization these desires are expressed through the Internet and other media (C. Liu & Wang, 2009).

Discussion

The parasocial interaction in Travel Frog is rooted in the Chinese social context. With the introduction of market mechanisms and Western values and the reform of education, the rise in their sense of individual autonomy has led young people to expect to live a free and independent life. However, the formation of the mainstream lifestyle, which contradicts the wishes of some young people, has been promoted by fierce competition for jobs, the hukou system, and family values. In the context of limited state welfare provision, the Chinese government emphasizes filial piety and the family obligations of the younger generation. In some families, parents try to intervene in all aspects of their children’s lives, which affects traditional filial piety. Some players of Travel Frog feel that the present mainstream lifestyle and their parent-child relationship restrict their ability to construct their own lives. This study finds that players project their desire to live freely onto the frog and express their idea of an ideal parent-child relationship by viewing the game character as their child. The emotional involvement in parasocial relationships is quite diverse. What Travel Frog provides to Chinese players is not simple enjoyment, excitement or stimulation, but a kind of special emotion existing in the parent-child relationship in a Chinese context. It includes the attachment to ideals and beauty, but this emotional experience is not an escape from reality. Instead, it is based on the criticism of current lifestyle and parent-child relationship in reality, which is difficult to characterize using quantitative methods of parasocial phenomenon research from the perspective of individual gratification. Moreover, the formation of this kind of game culture in Travel Frog is not generated by consciously and actively utilizing media to realize psychological needs but, rather, the consistency of interaction and emotional experience between real interpersonal relationships and the parasocial relationship. This consistency is similar to the congruence noted by Alexander Galloway (2004), in which some form of fidelity of context exists that transliterates itself from the social reality of the gamer, through one's thumbs, into the game environment and back again. This consistency connects the virtual game space with the real world and forms the basis for substituting real relationships into the relationship with the game character. To view the game character as a real-life character, the consistency of emotional experience may be more crucial than the similar interaction model; four interviewees who did not regard the frog as their child indicated that although they admitted that the interaction with frog is akin to their interaction with their parents, they could not have feelings toward virtual characters and regard them as real figures, which is an issue that could be further explored. Interestingly, all four of these interviewees were male. It seems that there is a gender difference in parasocial relationship: female players are more likely to regard the frog as their children. It may be one of reasons that Travel Frog attracted more female players: female players have a more special and richer game experience than male players. Future research might work to resolve this relative weakness in our project by further scrutinizing how gender roles factor in creating parent-child parasocial relationships between players and game characters.

Acknowledgements

In the process of finishing this paper, a lot of people offered help to me. First of all, I would like to thank Ms. Wu Hao, who provided many valuable suggestions for this article. Without her support and encouragement, I could not have completed this paper. At the same time, I am also very grateful to the editorial team, with special mention of Ms. Maria Gedoz Tieppo, whose efforts were indispensable to the publication of this paper. Finally, I would like to thank my anonymous reviewers for their sincere and insightful advice, providing me with great help and improvement.

Endnotes

[1] Wangyi Games. Date of visit: December 10, 2020. https://ent.163.com/game/18/0201/21/D9JEIH7J00318T0C.html.

References

Afridi, Farzana; Li, Sherry Xin; Ren, Y. (2015). Social Identity and Inequality: The Impact of China’s Hukou System. Journal of Public Economics, 123, 17-29.

Aurora. (2018). Female Mobile Game User Research Report in February 2018. Retrieved May 6, 2019, from https://www.jiguang.cn/reports/238.

Baek, Y. M., Bae, Y., & Jang, H. (2013). Social and Parasocial Relationships on Social Network Sites and Their Differential Relationships. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(7). https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0510.

Banks, J., & Bowman, N. D. (2014). Avatars are ( sometimes ) people too : Linguistic indicators of parasocial and social ties in player -- avatar relationships. New Media & Society, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814554898.

Biyang, F. (2011). Favor Society and Contract Society: On the Perspective of Theory of Social Exchange. Journal of Social Sciences, (2), 67-75.

Bond, B. J. (2020). The Development and Influence of Parasocial Relationships With Television Characters : A Longitudinal Experimental Test of Prejudice Reduction Through Parasocial Contact. Communication Research, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650219900632.

Cai, F., Park, A., & Zhao, Y. (2011). The Chinese Labor Market in the Reform Era. In China’s Great Economic Transformation (Cambridge. Cambridge University Press).

Chan, K. W. (2009). The Chinese Hukou System at 50. EURASIAN GEOGRAPHY AND ECONOMICS, 50(2), 197-221. https://doi.org/10.2747/1539-7216.50.2.197.

Chan, K. W., & Buckingham, W. (2008). Is China Abolishing the Hukou System ?*. The China Quarterly, 5(6), 582-606. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741008000787.

Cheung, C. (2009). The erosion of filial piety by modernisation in Chinese cities. Ageing & Society, 29(02), 179-198. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X08007836.

Croll, E. J. (2006). The Intergenerational Contract in the Changing Asian Family. Oxford Development Studies, 34(4), 473-491. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600810601045833.

Deuze, M. (2011). Media life. Media, Culture & Society, 33(1), 137-148. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443710386518.

Dibble, J. L., Hartmann, T., & Rosaen, S. F. (2015). Parasocial Interaction and Parasocial Relationship : Conceptual Clarification and a. Human Communication Research, 42(1), 21-44. https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.12063.

Ekman, I., Chanel, G., Järvelä, S., Kivikangas, J. M., Salminen, M., & Ravaja, N. (2012). Social Interaction in Games: Measuring Physiological Linkage and Social Presence. Simulation and Gaming, 43(3), 321-338. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878111422121.

Elihu Katz, J. G. B. and M. G. (1973). Uses and gratifications research. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 37(4), 509-523.

Galloway, Alexander. (2004). Social Realism in Gaming. Game Studies, 4(1).

Galloway, Anne. (2004). Intimations of everyday life : Ubiquitous computing and the city. Cultural Studies, 18(2), 384-408. https://doi.org/10.1080/0950238042000201572.

Giles, D. C. (2002). Parasocial Interaction : A Review of the Literature and a Model for Future Research. MEDIAPSYCHOLOGY, 4, 279-305.

Greenwood, D. (2008). Television as escape from self : Psychological predictors of media involvement. Personality and Individual Difference, 44, 414-424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.09.001.

Hit-Point. (2017). Travel Frog [Android mobile phone]. Digital game published by Hit Point Co. Ltd.

Hoffman, L. (2006). Autonomous choices and patriotic professionalism : on governmentality in late-socialist China. Economy and Society, 35(4), 550-570. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140600960815.

Hsu, F. L. K. (1948). Under the ancestors’ shadow; kinship, personality, and social mobility in village China. SMC Publishing.

Hwang, K. (1999). Filial piety and loyalty : Two types of social identification in Kwang-Kuo Hwang, 163-183.

Jin, S. A., & Park, N. (2009). Parasocial Interaction with My Avatar : Effects of Interdependent Self-Construal and the Mediating Role of Self-Presence in an Avatar-Based Console Game , Wii. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 12(6), 723-727.

Karoline Kan, & Ramzy, A. (2018). China Embraces a Game About a Traveling Frog. The New York Times.

Kavli, K. (2012). The Player ’ s Parasocial Interaction with Digital Entities. In Proceeding of the 16th international academic mindtrek conference (pp. 83-89).

King, N. (2017). China’s “996” working hours are becoming the norm for many. CGTN America.

Leung, J. T. Y., & Shek, D. T. L. (2011). Expecting my child to become “ dragon ” -- development of the Chinese Parental Expectation on Child ’ s Future Scale. International Journal on Disability and Human Development, 10(3), 257-265. https://doi.org/10.1515/IJDHD.2011.043.

Levy, M. R. (1979). Watching TV news as para ‐ social interaction. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 23(1), 69-80. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838157909363919.

Liebers, N., & Schramm, H. (2019). Parasocial Interactions and Relationships with Media Characters -- An Inventory of 60 Years of Research. Communication Research Trends, 38(2), 4-31.

Liu, B., Chen, H., Yang, X., & Hou, C. (2019). Why work overtime? A systematic review on the evolutionary trend and influencing factors of work hours in China. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 343.

Liu, C., & Wang, S. (2009). Transformation of Chinese Cultural Values in the Era of Globalization : Individualism and Chinese Youth. Intercultural Communication Studies, 18(2), 54-71.

Liu, J. (2017). Intimacy and Intergenerational Relations in Rural China. Sociology, 51(5), 1034-1049. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038516639505.

Lui, L. (2017). Hukou Intermarriage in China : Patterns and Trends. Chinese Sociological Review, 49(2), 110-137.

Mccutcheon, L. (2002). Are parasocial relationship styles reflected in love styles? Current Research in Social Psychology, 7(6), 82-94.

Montola, M. (2011). Social Constructionism and Ludology. Simulation & Gaming, 43(3), 300-320. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878111422111.

Newcomb, H., & Hirsch, P. M. (1983). tv as a cultural forum.pdf. Quarterly Review of Film & Video, 8(3), 45-55.

Nie, H., & XING, C. (2011). When City Boy Falls in Love with Country Girl : Baby ’ s Hukou , Hukou Reform , and Inter-hukou Marriage. In Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) annual workshop. Bonn, Germany.

Pargman, D., & Jakobsson, P. (2008). Do you believe in magic ? Computer games in everyday life. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 11(02), 225-244.

Rubin, A. M. (1983). Television Uses and Gratifications : The Interactions of Viewing Patterns and Motivations. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 27(1), 37-51.

Rubin, A. M., Perse, E. M., & Powell, R. A. (1985). Loneliness, parasocial interaction, and local television news viewing. Human Communication Research, 12(2), 155-180.

Schramm, H., & Hartmann, T. (2008). The PSI-Process Scales:A new measure to assess the intensity and breadth of parasocial processes. Communications, 33, 385-402. https://doi.org/10.1515/COMM.2008.025.

Shaw, A. (2010). What Is Video Game Culture ? Cultural Studies and Game Studies. Games and Culture, 5(4), 403-424. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412009360414.

Tian, Q., & Hoffner, C. A. (2010). Parasocial Interaction With Liked , Neutral , and Disliked Characters on a Popular TV Series. Mass Communication and Society, 13(3), 250-269. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205430903296051.

To, S. (2013). Understanding Sheng Nu (“Leftover Women”): the Phenomenon of Late Marriage among Chinese Professional Women. Symbolic Interaction, 36(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1002/SYMB.46.

Vogel, E. F. (1965). From Friendship to Comradeship : The Change in Personal Relations in Communist China. The China Quarterly, 21, 46-60.

Wang, M. (2012). Guanxi , Renqing , and Mianzi in Chinese social relations and exchange rules -- A comparison between Chinese and western societies (A case study on China and Australia). Denmark: Aalborg University.

Weber, R., Behr, K., & Demartino, C. (2017). Measuring Interactivity in Video Games Measuring Interactivity in Video Games. Communication Methods and Measures, 8(2), 79-115. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2013.873778.

Wu, X. (2016). The Research of Chinese Youth’s View of Marriage. Contemporary Youth Research, 344(5), 79-85.

Xiao, Q. (2000). Filial Piety and Chinese Nationality. Philosophical Research, 7, 33-41.

Yan, Y. (2009). The Individualization of Chinese Society. Oxford: Berg.

Yan, Y. (2010). The Chinese path to individualization. The British Journal of Sociology, 61(3), 489-512. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2010.01323.x.

Yuan, L. (2017). China’s Grueling Formula for Success: 9-9-6. The Wall Street Journal.

Zhai, X. (2004). Favor, Face and Reproduction of the Power: A way of social exchange in an reasonableness society. Sociological Research, 5, 48-57.

Zhou, W. (2018). Travel Frog: The cute Japanese game that has China hooked. BBC Chinese.

Zhou, X. (2008). The Tradition of Filial Piety and Seniority Rules:the Inter-generational Relationship in Traditional Chinese Society. ZHEJIANG SOCIAL SCIENCES, 5, 77-82.