Language, Identity and Games: Discussing the Role of Players in Videogame Localization

by Marina Fontolan, James Malazita, Janaina Pamplona da CostaAbstract

Videogame localization is the process of adapting and translating a game to other cultures than the culture the game was originally created in. This paper aims to analyze the role players have in videogame localization based on the perceptions of localization experts. We use data gathered during ethnographic field work in videogame conventions, archival materials and interviews with localization experts. The paper concludes that localizers perceive players as more than just consumers of the industry, as they put pressure on the industry to invest in game localization. Players further play a significant role in evaluating the effectiveness of the localization process.

Keywords: Videogames, players, localization, professional localization, games and identity

Introduction

“All your base are belong to us” (Zero Wing, Toaplan, 1989 -- Cf. Mandelin and Kuchar, 2017). The phrase, which became iconic in the gamer community, served as a hybrid nostalgia trip and meta-observation of the games industry of the 1980s and 1990s when “localizing” a game meant badly translating it, often with humorous results. It can lead us to think about the impact localization has exerted on the industry, why many games today use this process, how to keep an authentic feel of the game even in different versions and the role of players in this process. Localization is the adaptation and translation of videogames from their original language into another language. This is a highly complex process that involves word-level translation, including transliteration [1], as well as an adjustment of or creation of new cultural references that impact the player’s experience of the game.

Localization practices are not only in the purview of game publishers or translation professionals; players and customers, too, are affected. This can be especially true in marginalized and underrepresented languages. This paper analyzes the multiple practices and roles players play in videogame localization. Players can exert pressure on game companies to invest in localization for different languages, and often evaluate the work done in the localization process. Our previous research shows that some player communities intervene more directly than others, and use a combination of modding [2] tools and community labor to produce localization ecologies [3]: a set of systems used both to localize untranslated games and also to develop “counter-localizations” of official translations released by publishers (Fontolan, 2020).

As such, players exert agency in translation and localization practices, while also sharing a complex relationship with publishers, who may condone, condemn, or benevolently ignore their work. This decision, perhaps unsurprisingly, is often determined by the publisher's view of how much they will profit from it. “Localization” of a game is thus not a singular event, but rather emerges out of larger sociotechnical systems that include game designers, publishers, players, social media campaigns and software/modding communities. Specifically, we want to address the question of how professional localizers understand the role players have in videogame localization.

A key analytical framework for this paper is the concept of culture performance. According to Bhabha (1994), one has two different ways to engage in culture: in an antagonistic or in an affiliative way; especially towards the Other and their culture. In this sense, one might frame some or all aspects of another culture or even antagonize it. Of course, these relationships are complex and constantly ongoing, seeking to authorize cultural hybrids. This process is called hybridization, which is important not only for tracking cultural changes when observing different groups, but also for considering industry processes such as localization in videogames (see also Edwards, 2011).

Discussing Some Issues in Game Localization

Localization is more than the act of word-for-word translation. As the games industry grows at a steady pace, localization practices (see endnote 1) that account both for linguistic and cultural accuracy and authenticity have become a standard expectation in large markets -- especially among “EFIGS” European language groups (English, French, Italian, German and Spanish).

The localization process often occurs when a game is still under development. Typically, the goal is to complete localization before the game releases to the public, such that the game is released in different countries and languages simultaneously (a process also known as sim-ship). When and how the localization team is brought onto a project influences the result (Bernal-Merino, 2015).

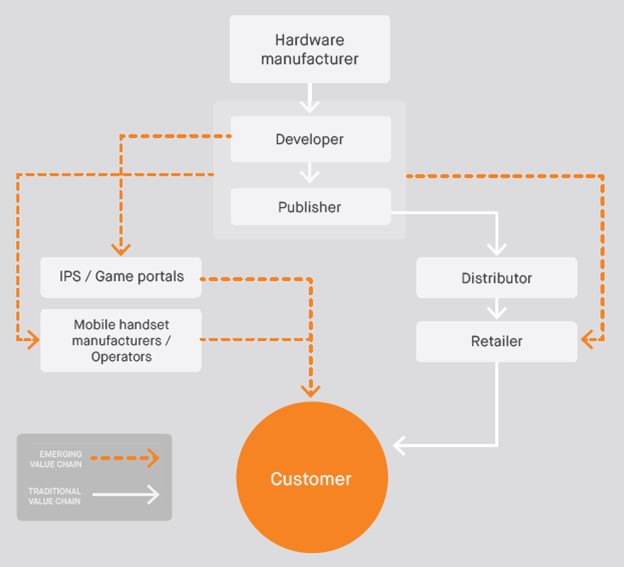

Figure 1: New configuration of the productive chain in the videogame industry (González-Piñero, 2017, p. 24). Click image to enlarge.

As seen in Figure 1, videogame development generally begins with developers identifying the platforms or hardware that their games will run on, though advancements in game engine and development software have afforded developers platform flexibility (González-Piñero, 2017; Silva, 2016). Development companies take the lead in producing the software and art assets that make up what we generally understand to be “the game,” often with the aid of subcontracted development houses. Publishers are generally responsible for marketing and managing the product's distribution chain, though developers have become increasingly enrolled in public relations strategies (Fleury, A. et al., 2014, pp. 53-54; de Lima, 2016; González-Piñero, 2017). This might be considered as a “new” production chain, as the digital distribution of games is fairly recent and introduced another dynamic to the industry. The diversity of technical needs, languages and financial resources of different studios that make up the games industry led to a diversity of localization practices. Mangiron and O’Hagan (2006, p. 2) state that:

Videogames (...) [are] a technology-driven sector and [are] constantly evolving with the developers maximising the use of cutting edge technology to demonstrate their creative talents. One of the most recent developments is the technical capability to incorporate human voices for in-game dialogues. This has replaced the use of written text in many cases, in turn giving rise to the need for dubbing and subtitling when games are localised. (...) There are a number of specialised game localisation vendors who provide a full range of localisation services [4].

The localization process starts when the game is still in its conceptual phase -- when the developers and publisher decide which market they will release the game in, and in which languages. As we will discuss later, a regional release does not necessarily guarantee a regional localization. When the game moves to alpha testing -- an early stage build of the game used to test for gameplay cohesiveness, glitches, early performance issues and basic cross-platform functionality -- game narrative and linguistic texts (including dialogue, system narration and menu options), are isolated from the code and sent to the localization team. The text is adapted, translated and returned to the development team, who implements the new text in the game for testing.

From a technical perspective, game localization has much in common with other forms of software/digital localization and translation (Cordoli, 2006; Maranesi, 2011). However, the aims and scope of games as media and entertainment objects introduces twists in the process. As Magiron and O’Hagan argue:

Game localization is an emerging professional practice and the translation process involved is characterized by a high degree of freedom and a number of constraints that distinguish it from any other type of translation (...). The reason for this lies in the nature of videogames as interactive digital entertainment which demands a new translation approach. Although it shares some similarities with screen translation and software localization, game localization stands apart because its ultimate goal is to offer entertainment for the end-user. To this end, the scope of game localization is to produce a target version that keeps the ‘look and feel’ of the original, yet passing itself off as the original. (Magiron and O’Hagan, 2006, online; Ranford, 2017)

While some of the localizers we interview in this essay have for-hire relationships with game studios, larger studios may employ their own in-house localization teams. For example, Ubisoft is a French videogame publisher with international development and sales offices, including in Brazil [5]. Traditionally it has developed its own games, and has had its own localization teams who decide where each game will be released and in which languages.

How much creative agency a localizer or localization team has is a subject of some debate in the games industry. Localization practices can and do change original scripts and word-choices of a game’s creators; potentially also changing emotional intent. Allison (2006) addresses issues of authenticity in the Pokémon franchise (Nintendo 1995), noticing that during the process of localization for Western countries, Japanese references had been erased from monster names and storefronts. This erasure helps Western audiences think that the product was made for them, rather than media imported from another country. However, not all videogame localizations are as aggressive. The Persona series (Atlus, 1996), for example, retains much of its Japanese geographical and cultural context in its Western localizations.

Localization changes are not only made to increase cultural familiarity or accessibility; legal institutions (such as ministries, secretaries and regulatory agencies) and regulatory frameworks, too, come into play. Localizing for the German market, for example, once required the removal or alteration of any references to Nazism, as the country’s policies disallowed any reference to them across various media formats until 2018. Localizers must work creatively within each localized country's legal codes.

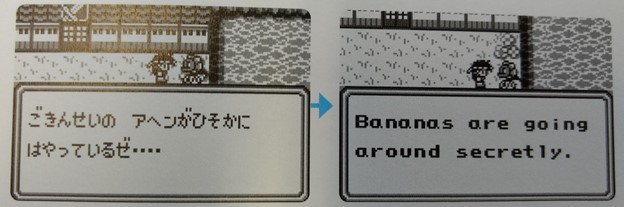

Figure 2: Final Fantasy Legend II Screenshot (Square Enix, 1990). Image retrieved from (Mandelin, 2017, p. 33). Click image to enlarge.

Figure 2 shows a result of such legal maneuvering. This figure is a screenshot from Final Fantasy Legend II, released for the Game Boy by Square Enix (then Squaresoft) in 1990. In this scene, the protagonist speaks to a flower; the flower is a poppy, the plant used to extract opium (Mandelin, 2017). The original Japanese sentence directly translated to “Prohibited opium is going around secretly” [6]. During the 1990s, Nintendo of America was prohibited from making any reference to drugs in their videogames, so the game's localizers changed the text to instead reference another plant-based material: bananas. The resulting conversation, “Bananas are going around secretly,” became another example of common localization “mistakes” in the 1990s.

Localization, then, is more than a simple word-for-word translation: it deals with local and global policies, forms of play and the production of individual, cultural and national identities. Localizers make some editorial choices that determine what game content becomes included in a given location, as well as what form that content takes.

Methodology

In this study, we aimed to understand how localizers construct their work and their role in the games industry. In addition, we were interested in analyzing the role that “authenticity” plays in localization, including perceptions of the importance of cultural authenticity, transnational legal frameworks and fan reception in the region chosen for translation. Fieldwork was conducted in four different game conventions, two in Brazil and two in the United States. They were carried on Brasil Game Show (BGS - São Paulo, 2017), Campus Party (São Paulo, 2018), PAX East (Boston, 2019) and Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3 - Los Angeles, 2019). These fieldwork excursions had two aims. First, getting in contact with industry representatives in order to interview localization teams and managers. Second, getting the developers’ and publishers’ points of view on localization practices during conversations. Notes were taken during these conversations with their consent. In total, there were 24 people who informally talked to the researchers during these conventions.

This study employed both semi-structured interviews with localization professionals and archival analysis of translated game texts. Our interviewees were either direct employees for videogame publishers, or performed contract-based work for several different companies in the videogame industry. They comprise a total of seven people. Our interviewees also represented a range of nationalities, which is to be expected from localization work, though it is important to note that all of our interviewees represented the Global North (see Table 1, below).

|

Name |

Role |

Type of Games they Work with |

Country of Origin |

|

Bailey |

Localization Manager |

PC games |

Germany |

|

Evan |

Localization Manager |

Multi-platform games |

United Kingdom |

|

Finley |

Localization Manager |

Multi-platform games |

Sweden |

Table 1: Interviewees

Participant names were changed to gender-neutral alternatives to meet anonymized research ethical standards. This research was approved by the Universidade Estadual de Campinas’ (English: University of Campinas -- Unicamp) ethics committee -- process number: 84249818.4.0000.8142. The three interviewees in Table 1 had their interviews recorded and transcribed, and they were chosen to be featured in this paper because they were the only localization managers. Considering that their role requires them to participate in several steps of the localization process, they were better able to systematize their perception on the role of players than the other interviewees.

Some other cases presented in this paper did not have their interviews recorded. These will be referenced with a name and where we spoke with them. These were the cases where we spoke with different industry representatives during PAX East (Boston, 2019) and E3 (Los Angeles, 2019). The sheer noise of the conventions and their fast-paced environment did not allow for a formal, recorded interview. All the information, however, was annotated on-site with the consent of the participants.

In addition to interviews, we conducted archival research at The Strong Museum of Play in Rochester, NY, USA. The archival research presented here draws mainly from the Chris Kohler papers collection, which include his journalistic writings and his fanzine VideoZone (Chris Kohler Archives. The Strong Archive). This research is supplemental in nature and was used as historical context for this paper.

Analyzing the Data: The Role of Players in the Localization Process

Discussing how game localizers perceive the players’ role in game localization is still a rare topic among scholars; with much of the prior work in localization studies focusing on player reactions to localized game content (Barcelos, 2017; Esqueda and Coelho, 2017; Ranford, 2017; Silva, 2016; de Souza, 2015; Postigo, 2007; O’Hagan and Mangiron 2013; O’Hagan, 2007). The growth of broadband internet access worldwide has allowed players to participate more formally and actively in the videogame industry as a whole, including in localization (Finley and Bailey interviews). Our data deepens some discussions that points to players participating in localization practices in multiple ways (see e.g., O’Hagan and Mangiron 2013), including by driving market demand, contributing to fan translations and scripts and using custom and commercial game modification software to develop homebrewed localizations. There were two prominent roles described: the role of localization reviewers and the role of localization demand.

Player expectation of localized game releases emerged as a recurring theme during interviews. Evan (a multi-platform games localizer from United Kingdom) noted that:

[localization is] an expectation from the players. If there’s a new game released, then they want to have their language included. Which of course, again, means that localization has to start earlier. And it has to be completely done when the game is ready to ship.

In other words, even though the process itself is not that well known among players, they will expect it to occur, resulting in a game that is adapted to them.

Localization demands are not limited to yet-to-be released games; potential localizations of previously released games were also a common topic of discussion among the interviewees. Shannon, a representative from an American publisher (Shannon, PAX East 2019), shared a story of demand over a recent release where the game’s interface and subtitles were available in ten different languages, but where the game's audio was English-only. There was demand among the game’s player community that the publisher localize the game's text in Hungarian, which was not one of the game’s 10 original languages. This was not done, Shannon noted, as the cost would be too high for what they perceived as too small of a market. Similarly, Finley (multi-platform games localizer from Sweden) also reported active community localization demands:

The more languages we make available, the more players we get, and also it can give us more players who also want other languages. You'll have people talking about Turkish for several of our projects. It's a kind of hard language to translate into, because it’s only Turkey that has it... And it's also not very cheap. (Finley)

Players demand a game to be localized, which is a significant part of their role in the process. This, however, is not always an issue at the time of a game’s release, as the case of Final Fantasy V (Square Enix, 1992) shows. This game was originally released in Japan in 1992 for the Super Famicom (console known in the United States as Super NES). The game was not released in the US during that year, due to Square Enix’s inability to localize it -- which included both language and gameplay localization [7]. Players pressured Square Enix to release the game in the US, leading to an official US release by late September, 1999 for the PlayStation.

This example and Finley’s statement also reads as a way for players to get their language represented in products worldwide, which ties to a representation and identity discussion. Having a game localized into a specific language should give players the sense that they are being represented in the industry, supporting the game by boosting its consumption. One interesting aspect of this is that players, in these contexts, are already playing the game, but are nonetheless demanding a new language be added to the game. In other words, these players seem able to understand at least more than one language, so the situation is not exactly as black-and-white as Finley constructs. However, the demand here might come from a place of experiencing the game differently, either enjoying the game along with people who are not multilingual or by the player themself. In this later case, game consumption is stimulated by players who are willing to have a more authentic experience of the game in their native language (Fontolan, 2020).

The discussion on players, language and game consumption was a common topic among fieldwork respondents. According to Jackie, a representative from a Japanese publisher (Jackie, E3 2019), the company’s employees regarded Brazilians as a strange population. Brazilian players would often manage to play games available in their market regardless of the game’s language; a practice not shared by European gamers whose game choices were in part determined by language availability. Jackie framed Brazilian players as “subservient” [8] to games and will play them regardless of the language, an attitude the Japanese company could not properly understand. This relationship between resisting a product [9] and not accepting it unless it is presented in the player’s preferred language reveals how vital players are to the industry in general and to the localization process in particular. Not all players seem to care about the language the game is in. Some players even prefer playing games in their original languages, even though they might not understand the game (see Shaw, 2013). However, players are able to pressure the industry to localize and release the games they want to play, and Final Fantasy V (Square Enix, 1992) is a major example of this industry’s dynamic. A more recent example of this is the game World of Warcraft (Blizzard Entertainment, 2004), which was released into Brazilian-Portuguese in 2011 after a two-year localization effort required by the players. This also included being able to play in Portuguese, pay for the game in Brazilian Reais, and have their own server within the game [10].

The second time the discussion on players, language and game consumption came up was during PAX East (Boston, 2019), when a representative from an American indie developer company (Ricky) discussed how localization practices are market-driven. This account shows how not all game communities are sufficiently influential to secure localized content. At that time, the game they were developing was going to be released exclusively in English. All the game advertisements were in English, and the representative thought it was sufficient, as the game did not develop a large enough French-speaking community to warrant French localization. French localization was considered a waste of resources compared to other marketing strategies they prioritized. It is interesting to notice that the representative was not considering the role localization could have in building a community for the game, contrasting with Finley’s (a multi-platform game localizer from Sweden) discussion on the topic.

However, even though the games were not always localized, many players would still play them, and use FAQs and walkthroughs available on different websites [11]. Some players would even upload their own translations of games they played as mods, creating an entirely new game culture in a country that deals with language barriers in different ways. Jackie’s view that players in such countries are subservient to games is, actually, much more complex than they seem to believe. It is important to notice that this is not exclusive to countries in the Global South like Brazil or India. The following excerpt was taken from Issue 16 of the Video Zone Magazine:

(…) If you are saying “I really would buy it except for the Japanese” then buy it ‘cause you [sic] problems are solved -- I have written a FAQ that is up on AOL that translates almost everything in the game (you just need a Japanese viewer, but that’s on AOL too). Contact me (…) if you want to know where to DL it from, and if you don’t have AOL, I can mail the FAQ to you on a disk with the viewer if you want, just get in touch with me. (Video Zone, Issue 16, Page 2, 1995) [12]

This shows that playing a game in another language does not necessarily mean being subservient and playing the game for the sake of playing. It might also mean creating different strategies to cope with language limitations; which may lead to growing a stronger community with more power to acquire official localized game versions in the future. The idea is that industry representatives might at some point consider new languages and countries for localization, search for player communities already dealing with videogame localization in an informal setting and contract hobbyist translators to assist with official localizations.

Bailey, Evan and Finley discussed how localization is a process that boosts consumption. Moreover, the idea of game communities and their role in localization practices was even further discussed. In other words, localizers understand that the role players have in these communities goes beyond demanding languages they want to play games in, or creating mod-based localizations on their own; they are also key in reviewing and criticizing professional localization work.

Interviewees were also asked to comment on the relationship between their localization practices and the player community’s comments on them, which often took the form of forum posts and bug reports (Bailey, Evan and Finley interviews). According to interviewees Parker (PAX East 2019) and Winter (PAX East 2019), users’ reviews on localization are essential assets for quality assurance, though how the information provided by users is incorporated into localization practices differs from case to case. Bailey (a multi-platform game localizer from Germany) comments:

(…) I'm all the time in touch with the consumer. So, if there's something they are complaining about the localization, that's something I see immediately. And if it is a typo or if it is anything else or if there is a big problem, I report back to the development team and they take care of that. (Bailey)

Bailey notes that the player base's reactions to a localization are constantly monitored. Localization bugs provided by players are then sent to the development team for fixing. Evan (a multi-platform game localizer from the United Kingdom), though, described the process a little differently:

(…) We do have dedicated forums, and bug report systems for reporting any localization bugs. But the thing with players reporting anything is that they often have a very strong, but very subjective opinion about how things should be called. So, we always have to review whether these are justified to be changed. But of course, if we can, if it makes sense, then we are quite happy to accommodate the suggestions of the players. And important approach that I normally tend to follow is that the ownership of the text always stays with the translators. So even if there is a comment from the players, and we think it might be okay to change, we always send it back to the translators to have a final say in this. And an important thing that we try to do with the players is always provide feedback about their comments, and to let them know what is being implemented. What are the things we cannot do for various reasons, but we always try to acknowledge that we have received their feedback, we’re looking into it, we've implemented this will be the next update. And these are the things that we couldn't do. And sorry about that. So, we try to be very open in general with how to communicate to the players, not just in this regard, but generally. (Evan)

This approach to player suggestions outlined by Evan is quite different from what was described by Bailey (a multi-platform game localizer from Germany). First of all, Evan describes having a forum system where players can report any issues they have, including localization issues. The process of considering player demands to change some part of a game’s localization is relevant. After all, not all reported or suggested changes will actually be implemented into the game. The decision-making process involves the publisher’s localization team and the localizer who worked on that text. The relationship built with players is based on feedback that states if a change will be made and what it will be. This acknowledgment seems to be essential to encourage players to continually file bug and localization reports, providing constant feedback to the publisher. Players, in this case, are allowed to explore their ideas and provide the company with them. The interactions between player community and publisher allow both for free-labor bug reporting and localization ideas, resulting in cost-free game enhancements. Of course, there are tensions in this model, especially regarding the publisher’s team not accepting player-suggested localization ideas; which can create friction in their relationship. These differences might be related to each company’s policies regarding localization, and is probably tied to the types of games each company publishes: Bailey’s company is specialized in PC games and Evan’s on multi-platform games. Further research on this theme is required to understand how these factors influence publisher-player relations.

This structure seems to be close to the structure described by Finley (a multi-platform game localizer from Sweden):

We do have the forum, which is very vocal (...). Most [players] do give us bug reports and list what's wrong with everything. And had some friends who would tell us "Ok, so this language has these problems, we think it should be like this instead." (…) And those reports are often assigned to me and [I] then either ask the translators for help or I can, in some cases, fix it myself, because it's might be something that that's broken... A file has the wrong format or something. (…) the designers are very welcome to go back [and] update localization, which means that we have to... Either we catch that and we managed to send it off to the translators and they fix it, or [they rewrite the text]. (Finley)

These cases suggest that localizers consider specialized forums play a major role in understanding player opinions of a game. These opinions can include how the game should be localized, as well as any other issues players find during their play. Of course, not all player considerations are taken into account, but generally player reactions to the localization are considered essential to the process.

The above discussions are representative of game publisher perspectives. Interview notes sent by Finley show that localizers are as eager to acknowledge feedback from players as game publishers are. These excerpts show the critical role players have in the localizer’s work:

As a translator and a former player I try to collect as much feedback as possible, via specialized forums. The players are essential to finding all those tiny things that may be improved, or whenever some content may be unclear, etc. So they're critical to improving a game translation. (Finley notes)

We naturally check all the users' bug reports, but in 80% [of] cases suggested changes are violating simple grammar and style rules and formal rules of translation. Mostly minor bugs spotted. BUT: the situation with the core fan community, [the] (...) strategy is quite different: there are some super professionals, and we always take their suggestions into consideration and try to partner with those guys during LQA. (Finley notes)

Yes, we do collect comments and opinions from players and make changes accordingly. What we usually do is to open a thread on game forums to collect comments and check the thread from time to time. (Finley notes)

Yes we try to collaborate with the community if possible, but there can be as controversial feedback, and really improving feedback, we discuss the feedback with team worked on a project to decide if it will improve the game indeed or not. The feedback gathered usually on forums or groups in social networks or sometimes a teammate who works on another project but plays the game localized gives feedback on localization. Frequency depends on the process built on client’s side. (Finley notes)

The localizers perceive player reports as a significant issue to improve their localizations, usually using social media or specialized forums for such. However, not all player feedback is taken into account, generating some internal debate on whether to incorporate player feedback, and what kind of feedback to consider for review. These excerpts also highlight a previously-mentioned issue: the reliance on players who participate in a game’s community as localizers and LQA testers.

Even though players hold some sort of agency in requiring that games be localized and in evaluating the efficiency of the localization process, their agency is limited by two main features. The first is related to profit: according to our gathered data, the localization process will only be performed on languages that are more likely to benefit game publishers with additional profit. The second feature is related to the game publisher's willingness to change an already completed localization. Both localization managers and specialists stated that they choose which player suggestions (if any) will be considered when reviewing the localization process.

Player agency, from the localizers’ perspective, is limited to both profit and the company’s will to change the work they paid to be done. However, when faced with these limitations, players might turn to modding the game, adapting it to their wills and necessities [13].

Final Considerations

The rise of digital game distribution played a major role in the localization process and vice-versa. As digital games became more accessible worldwide, players could purchase as many games as there were available with the only major impediment being their willingness to pay for them. One of the results of digital distribution is that games could be introduced to new (and sometimes unknown) markets, allowing users to provide evaluations more easily and frequently. Another result is that publishers and developers were more easily exposed to player needs, and could better understand them. Hence, game communities were empowered to start demanding that games have certain features, including new languages. Players were also enabled to talk about their experience with a given game localization in more formal ways: through forums and bug reports. However, it is crucial to note that player voices are only considered if the game’s publishers and localizers are willing and able to respond to player feedback. These were the major perceptions reported by localizers during the interviews we conducted for this research.

The role of player communities in game localization is as important as the process itself. This is because belonging to a community not only allows a player to be identified with a group, but also allows them to create an identity for themselves. It puts pressure on game producers to create games players expect to play, and to have those games available in languages players want to see themselves represented in. The identity of being a player not only has a role in requiring games be made available in specific languages. It also plays a role in identifying who can be a videogame localizer, as being a native speaker and liking games (especially the genre of the game being localized) was an interesting aspect of this study's empirical evidence. If the language requirement is not addressed, a game might still be consumed and create a resistance culture of modding and writing game walkthroughs such that the game can be played regardless of what language it is in. In other words, games will be played, but players will create new forms of playing them if the industry fails to address their language requests as necessary. These findings show that localizers’ perceptions on the role players have in videogame localization are multifaceted, and therefore require additional empirical study.

These discussions strongly relate to the arguments presented by Kurt Squire (2012) and the elements of play. He analyzes the game in its social context as the most important factor when considering the relationships between culture and play. In this sense, game communities -- formed by players -- act by pressuring the videogame industry to localize games, so that publishers and developers address the context a game is played in. Besides that, the discussion on the role of players in videogame localization also relates to Bhabha’s (1994) idea of culture performance. When a gaming culture becomes recognizably important, it becomes necessary that the industry address it by supporting language localization catered to that culture. This process brings that culture further into the mainstream while also using its players as peer reviewers to improve the localization. This also relates to Kate Edward's (2011) arguments on localization and culturalization.

The tensions between publishers, developers and players regarding localization also show that the player’s role in requesting languages is a new asset for publishers and developers. This contact between players and game developers is often positive. However, it may also lead to problems as players start to require even more languages, and complain about some of the choices localizers make during the localization process and the game's final results. The localization process creates tension in the relationship between a game’s players and the developers and publishers who made it; as the latter want to provide the former with good gaming experiences, but cannot afford to handle all player expectations and requirements.

Acknowledgments

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001 (processes codes: 88882.329775/2018-01 and 88881.188643/2018-01). This finance came in the form of a Ph.D. and International Visiting Scholar grants provided to Marina Fontolan. We also thank Professor Léa Maria Leme Strini Velho for being the Ph.D. program supervisor for Marina Fontolan.

Endnotes

[1] The practice of changing alphabets, or transliterating words from one alphabet to the other without translating the word. For example: transliterating 你好 to NiHao, from the simplified Chinese alphabet into the English alphabet. 你好 means hello. Source: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/transliteration, accessed on May, 16th 2022.

[2] Modding is a practice in the videogame industry in which players (known as modders) tamper with the game’s source code to change different aspects of it, including language.

[3] There are several examples of fan translation, including The Elder of Scrolls V: Skyrim (see Fontolan, 2022) and Baldur’s Gate (see https://www.pcgamer.com/baldurs-gate-contains-close-to-a-million-words-of-dialog-and-how-fan-translations-helped-the-enhanced-edition/, accessed May, 16th 2022).

[4] The term localization in British English is written with an 'S'. Thus, one might find the two written forms in this thesis when quoting a British scholar or a British person who works with videogame localization.

[5] On the Ubisoft’s offices: https://www.ubisoft.com/en-US/careers/experience.aspx#world-map, accessed on Sep 27th, 2017.

[6] Source: https://legendsoflocalization.com/were-the-bananas-in-final-fantasy-legend-ii-actually-drugs/, accessed on May, 16th 2022.

[7] Chris Kohler Archives, Box 1, Folder 1. The Strong Archive. Video Zone, Issue 7. The gameplay localization, in this case, is also related to in-game changes that made the game easier to beat.

[8] Here, we opted to use the exact term the interviewee used. As this was not a recorded interview, but only a field note, it is not possible to retrieve the entire sentence that was spoken, but only main terms.

[9] In this case, it stands for consuming a product (e.g., a game), even though one cannot fully appreciate it.

[10] For more information, see: https://g1.globo.com/tecnologia/noticia/2011/10/world-warcraft-em-portugues-chega-ao-brasil-em-dezembro.html, accessed on Jan, 19th 2022.

[11] One example of such websites is: https://pratasdicas.com.br/, accessed February, 5th 2021.

[12] Source: Chris Kohler Archives, Box 1, Folder 1; The Strong Archives.

[13] There are several studies on game modding and romhacking in game studies literature, which discusses different aspects of the practice (see e.g., Postigo, 2007; Poretski & Arazy, 2017). In this research, these issues are included but bring to the fore new areas of investigation. In this sense, it is a limitation of our research.

References

Allison, A. (2006). Millennial Monsters: Japanese Toys and the Global Imagination. University of California Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1ppk4p.13

Atlus. Revelations: Persona. (1996) [Sony PlayStation]. Digital game directed by Kouji Okada, published by Atlus.

Bhabha, H. K. (1994). The Location of Culture. Routledge.

Barcelos, L. G. N. (2017). A Tradução de games: um estudo descritivo baseado no jogo Overwatch [Bachelor’s thesis, University of Brasilia]. Biblioteca Digital da Produção Intelectual Discente da Universidade de Brasília. https://bdm.unb.br/bitstream/10483/18733/1/2017_ LuizGustavoNogueiraBarcelos.pdf

Bernal-Merino, M. Á. (2015). Translation and Localisation in Video Games: Making Entertainment Software Global. Routledge.

Bethesda Game Studios. (2012). The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim. [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Todd Andrew Howard, published by Bethesda Softworks.

Blizzard Entertainment. (2004). World of Warcraft [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Ion Hazzikostas, published by Blizzard Entertainment.

Cordioli, E. M. (2006). Empreendimento em Vigilância Tecnológica para Localização e Internacionalização de Software [Bachelor’s thesis, Federal Univeristy of Santa Catarina]. UFSC Repositorio. https://repositorio.ufsc.br/handle/123456789/183929

de Lima, F. N. (2016). Fatores Críticos de Sucesso na Indústria de Jogos Eletrônicos [Doctoral dissertation, Universidade Estadual do Ceará]. Biblioteca Digital Brasileria de Teses e Dissertações. http://bdtd.ibict.br/vufind/Record/UECE-0_baafb510c2f3a081b78a0852465cabdd

de Souza, R. V. F. (2015). Tradução e videogames: uma perspectiva histórico-descritiva sobre localização de games no Brasil [Master’s thesis, University of São Paulo]. Biblioteca Digital USP. https://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/8/8160/tde-03122015-131933/pt-br.php

Edwards, K. (2011). Culturalization: The Geopolitical and Cultural Dimension of Game Content. TRANS Revista de Traductología, 15, pp. 19-28.

Esqueda, M. D.; Coelho, B. R. (2017). O inexplorado em Uncharted 3: normas de expactativa versus normas profissionais em games traduzidos. Tradução em Revista, 22, pp. 137-167. https://doi.org/10.17771/PUCRio.TradRev.30592

Fleury, A., Ojima Sakuda, L., Dell’Osso Cordeiro, J. H., Nakano, D., Fortim de Campos, I., Bastos Tigre, P., de Oliveira Lemes, D., Loreto Querette, E., Retto de Queiroz, E. K., Cruz Teixeira, F L.., Schwartz, G., Anders, G., Ranhel Ribeiro, J. H., Goldenstein, L., Petry, L. C., de Oliveira Ramos, R. A., Araújo Sousa, S. V., de Macedo Cabrera, A. C., de Moura Grando, C., Tosi e Colaborado, T. M. (2014). Mapeamento da Indústria Brasileira de Jogos Digitais (Report no. 1). Indústria Brasileira de Jogos Digitais, GEDIGames, University of São Paulo. https://www.abragames.org/uploads/5/6/8/0/56805537/i_censo _da_industria_brasileira_de_jogos_digitais_2.pdf

Fontolan, M. (2022). Fus Ro Dah! Skyrim 10th Anniversary Edition, Subtitles, and Digital Humanities. E-Tramas, 11, pp. 19-36.

Fontolan, M. (2020). It is €0,10 a word! The role of localization in the videogame industry [Doctoral dissertation, University of Campinas (Unicamp)]. Base Acervus Sistema de Biblioteca da UNICAMP. https://doi.org/10.47749/T/UNICAMP.2020.1149424

González-Piñero, M. (2017). Redefining the value chain of the video games industry (Report 01/2017). Knowledge Works National Centre for Cultural Industries. ISBN: 978-82-93482-13-0

Mandelin, C. (2017). Legends of Localization Book 2: EarthBound. Fangamer.

Mandelin, C.; Kuchar, T. (2017). This be book bad translation, video games!. Fangamer.

Mangiron, C.; O’Hagan, M. (2006). Game Localisation: Unleashing Imagination with ‘Restricted’ Translation’. The Journal of Specialised Translation, 6(July). http://www.jostrans.org/issue06/art_ohagan.pdf

Maranesi, L. A. H. (2011). Estudo de um caso de Localização de um Software ERP de Código Livre [Master’s thesis, University of Campinas]. Biblioteca Digital Brasileria de Teses e Dissertações. http://bdtd.ibict.br/vufind/Record/UNICAMP-30_6ee4df4f8d3ffaf9b4e1e2c9a404cc89

O’Hagan, M. (2007). “Video games as a new domain for translation research: From translating text to translating experience”. Revista Tradumàtica: Traducció i Tecnologies de la informació i la Comunicaió. Número 5: Localizació de videojocs. Novembre 2007.

Mangiron, C.; O’Hagan, M. (2013). Game Localization: Translating for the global digital entertainment industry. John Benjamins Publishing.

Pinch, T.; Bijker, W. E. (1990). The Social Construction of Facts and Artifacts: Or How the Sociology of Science and the Sociology of Technology Might Benefit Each Other. In Pinch, T., Hughes T. P., & Bijker, W. E. (Eds.), The Social Construction of Technological Systems (pp. 17-50). The MIT Press.

Porestski, L.; Arazy, O. (2017). Placing Value on Community Co-creations: A Study of a Video Game 'Modding' Community. In Lee, C. P., Poltrock, S. (Eds.), CSCW '17: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing (pp. 480-491). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2998181

Postigo, H. (2007). Of Mods and Modders: Chasing Down the Value of Fan-Based Digital Game Modifications. Games and Culture. 2(4), pp. 300-313. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1555412007307955

Ranford, A. (2017). Targeted translation: How game translations are used to meet market expectations. The Journal of Internationalization and Localization, 4(2), pp. 141-161. https://doi.org/10.1075/jial.00006.ran

Shaw, A. (2013). How Do You Say Gamer in Hindi?: Exploratory Research on the Indian Digital Game Industry and Culture. In Huntemann N.B., Aslinger B. (Eds.), Gaming Globally. Palgrave Macmillan.

Silva, F. (2016). The mapping of localized contents in the videogame inFamous 2: a multimodal corpus-based analysis [Doctoral dissertation, Federal University of Santa Catarina]. UFSC Repositorio. https://repositorio.ufsc.br/handle/123456789/173818

Square Enix. (1990). Final Fantasy Legend II [Nintendo Game Boy]. Digital game directed by Akitoshi Kawazu, published by Square Enix.

Square Enix. (1992). Final Fantasy V [Nintendo Super Famicom]. Digital game directed by Hironobu Sakaguchi, published by Square Enix.

Toaplan. (1989). Zero Wing. [Sega Mega Drive]. Game produced by Toshiaki Ōta, published by Toaplan.

Archival Materials

Chris Kohler Archives, Box 1, Folder 1. The Strong Archive. Video Zone, Issue 7, c. 1993.

Chris Kohler Archives, Box 1, Folder 1. The Strong Archive. Video Zone, Issue 16, 1995.