Myths, Monsters and Markets: Ethos, Identification, and the Video Game Adaptations of The Lord of the Rings

by Mark Rowell WallinMarshal McLuhan noted in Understanding Media that there comes a point in the development of a new aesthetic form where the new media attempts to gain legitimation by means of association with previous forms. Ancient epic poetry adopted the structure and narratives of oral storytelling; opera and ballet began by adapting significant dramatic works, as did film; the early novel appropriated the form and structure of the historical treatise; and video games are no different. Bolter and Grusin (1999) test McLuhan’s media axiom in their work Remediation, where they clearly demonstrate the ways that videogames draw upon the conventions, material, and perspectives of other media - primarily television and film. But in an exploding market, where it has long surpassed its closest media cousin (film) in terms of profits, the only world left for the video game to conquer is the one of critical acceptance and aesthetic legitimacy. Rhetorically, identification is the process by which agents establish themselves within a community by adopting its terms and expressive strategies to the point where those agents identify with and are identified as part of the community. From this perspective, adaptations create identification with earlier titles, authors, and techniques in order to gain acceptance and distinguish themselves from others with whom they compete. In the case of The Lord of the Rings series of video game adaptations, we find that adaptive legitimation is sought not only at the titular level but also at the level of form and content. Each competing company seeks to appeal to a culturally perceived authority to improve its chances of being seen as “the real” The Lord of the Rings adaptation.

Of course, such rhetorical concern with authority and identification cannot help but trespass on the ground of ethos. But while much critical invocation of ethos addresses matters of an author’s “character,” in this case, the author is a shadowy figure. To which author does EA’s series of Lord of the Rings games appeal for its authority? J.R.R. Tolkien, or Peter Jackson? What we find is that video games, currently lacking their own cannon of authorship [1], use the process of identification with both cinematic and literary elements to create a sense of “origin” that would be otherwise provided by an author-figure. Each corporate line must strike an associative balance between populism (say, in the form of Jackson’s hit films) and purity (in the form of Tolkien’s revered classic). While EA attempts to link itself directly to Peter Jackson’s filmic texts, it retains a structural association with Tolkien’s work. Conversely, the Vivendi/Tolkien Estates line of adaptations, designed by Sierra Entertainment, Black Label Games and Liquid Entertainment, overtly eschew Jackson’s blockbuster series for a direct, familial consubstantiality with Tolkien’s oeuvre - they chose to enter The Lord of the Rings canon by means of direct association with the books, rather than the films. But because EA has the association with the sexy, prominent media juggernaught of Jackson’s films, Vivendi turns to structure to provide its populist appeal; Vivendi adapts the Lord of the Rings settings to classic gaming platforms to provide continuity.

Adaptation’s power, then, is generated primarily from association: we approach the new interpretation in the terms of the source, or model. That is, we are asked to, to one degree or another, think of these two separate texts as simultaneously different (insofar as each text contains its own aesthetic values and media-specific features) and the same (similitude ranging from the semiotic association of paronomasia [2], to the overt sameness of title, form, and content). In the same way, authors are evoked in order to create distinction or identification, as well as to demonstrate similitude or consubstantiality. This paradoxical relationship is perhaps the most difficult one to handle for adaptation studies. The most common solution is to simply pick which method of analysis best suit the texts in question (film theory for film adaptations, literary criticism for literary adaptations, new media analysis for new media adaptations, etc.) and slavishly adhere to that model, but such a strategy ignores the subtle nuances that occur between adaptation and adaptation as they vie for cultural capital, or between competing models attempting to establish which is the more “authentic.”

The EA/Peter Jackson, Lord of the Rings Games

The video or computer game medium provides a unique opportunity to realize events portrayed in other media forms. By adding various levels of interaction between players and the environment, the legitimated narrative is enriched. But as interactivity and narrative are frequently at odds (narrative is an imposed order, while interactivity presumes a measure of indeterminacy), when one adapts a model to the game a range of constrains naturally follows. The adapted text is characterized by a hybridization of, on the one hand, interactive elements (at the level of spatial task), and on the other, narrative (in the larger presumptions of character movement and total game trajectory). Simply, plot is transformed into geography insofar as “when you adapt a film into a game, the process typically involves translating events in the film into environments within the game” (Jenkins, 2004). Henry Jenkins describes this process as the creation of “spatial stories” which share with the science fiction and fantasy genres a preoccupation with world creation at the expense of plot and character. In fact, when it comes to the realization of a secondary world, the video game may have an edge:

“When game designers draw story elements from existing film or literary genres, they are most apt to tap those genres - fantasy, adventure, science fiction, horror, war - which are most invested in world-making and spatial storytelling. Games, in turn, may more fully realize the spatiality of these stories, giving a much more immersive and compelling representation of their narrative worlds” (2004).

From this standpoint, the function of the game, regardless of the level of narrative overlay, or correspondence with the model is not “so much [to] reproduce the story of a literary work… as [to evoke] its atmosphere” (2004). The video game may produce narrative on at least one of four levels: it may evoke a pre-existing narrative association, it may provide a staging ground upon which narratives may be created, it may imbed narrative elements in its mise en scene, and it may provide resources for emergent narratives. Significantly, when we examine the EA and Vivendi lines of The Lord of the Rings games we find that all four levels of adaptive narration are being exploited. But most obviously, we find that EA exploits the advantage of a cinematic, as opposed to a literary model to, both evoke a pre-existing narrative through its title, character associations, and setting designs, as well as embedding narrative elements in its mise en scene, at both the gameplay and skill-advancement levels.

Plot Overlapping

Both The Two Towers (2002) and The Return of the King (2003) divide the narrative into three parts that coalesce and diverge. The first line is that of the Frodo and Sam, the second, that of Gandalf, and the third, of Aragorn. This branching of narrative is reflected directly in The Return of the King video game (2004). Rather than forcing the gamer to move through a strict and linear narrative trajectory, as in The Two Towers (2002) [as well as Vivendi’s Hobbit (2003) and Fellowship of the Ring (2002)], EA’s Return attempts to replicate Jackson’s (as well as Tolkien’s) strategies of representing temporal simultaneity. This simultaneity occurs primarily by the overall game sequence screen, but also by the occasional interactions between characters that separate and then come together to further the overall plot. Thus, as Jenkins predicts, narrative plot is transformed, at least partially, into geographical space. But the most apparent moments of identification between the video game and film occur at the level of direct exposition.

The Return of the King game, more than any other Lord of the Rings adaptation, is wholly dependent on the narrative form of its model. Because of vast stretches of direct film insertion used to link the various action episodes, it represents a relatively rare example of adapted gameplay: an interactive medium that borders on being controlled by plot. These prolonged passages from the film are coupled with new voice-over tracks, primarily from Ian Mckellen, which provide motive and direction for the gameplay sequences, but more importantly, drive the sequences toward a narrative conclusion. This direct relationship between the film clips, actors’ voices, and gameplay sequences rigidly control the adaptive process. There can be no confusion as to the model of these games: they are directly connected to the film at every level; and the direct imposition of the cinematic plot through cut scenes and added elements, onto an otherwise fragmented gameplay, demonstrates this nicely.

The game plot attempts to structurally mimic that of its cinematic model by creating three parallel timelines. These are presented in a map that begins the game.

Figure 1: Approaching the Story Map of EA’s Return of the King

The map in figure 1 is a replica of a tree carved into the stone walls of Minas Tirith, an association drawn, not from the film, but from Tolkien’s description of the imposing hall of the Kings of Gondor (1991, p784). Tolkien’s uses the tree of Gondor as a symbol of the health of the line of Kings: the tree itself stands atop Minas Tirith before the hall of kings, but the symbol of the tree is carved into the armor of Gondorian soldiers and on the wall behind the king’s throne. The tree represents both the family lineage of the Gondorian kings and the kingdom itself; when Aragorn is crowned and reunited with Arwen, the tree begins to flower anew (presumably in anticipation of Aragorn’s heir, Eldarion) after generations of sterility. Therefore, the use of the King’s family tree as navigation screen accomplishes four things in the game: first, it links the game to the minutiae of Tolkien lore (Jackson and Weta have commented on the pains they took to use the smallest details of set and costume to flesh out Tolkien’s secondary world [3]). Second, the tree establishes a direct familial consubstantiality between the three diverse narratives of the game - we understand that they are of the same substance and operate toward the same goal.

Third, the tree system allows the gamer to understand relative time by transforming time into space: the game has a beginning (Helm’s Deep) and an end (The Crack of Doom), which are connected by direct lines of narrative plotting that converge at these two moments. What we see here is a clear example of the transformation of plot into space - not only do the episodes unfold in terms of moving the character from one point to another, but the entire plot movement of the game is spatially represented in shorthand. After the Helm’s Deep episode, the timeline branches and gamers must choose between the Gandalf plot which takes them from Helm’s Deep to Isengard and finally to the battle for Minis Tirith; the Hobbit plot which follows Sam, Frodo, and Gollum from Osgiliath through Shelob’s lair and Cirith Ungol, to Mount Doom; and the central (both spatially and narratively) “Path of the King” plot which moves Aragorn, Legolas and Gimli through the Paths of the Dead, to a battle with the king of the dead, the arrival at the southern gates of Osgiliath, to the battle of the Pelinor Fields, and finally to the black gate. Thus, the map places the episodes in a relative chronology. The position of each episode along the timeline, in relation to the other episodes attempts to do something that can only be achieved in traditional narrative forms (such as the film and the novel) through exposition: showing us exactly what happens when. We can see that while Gandalf defends the walls of Minas Tirith, Sam battles with Shelob. We can also see, significantly, that Frodo looses his mithril shirt in Cirith Ungol just before it is presented to Aragorn at the black gate as a ruse to break his will. In other words, the conventions of the gaming medium seem to provide certain advantages to conceiving of the overall plotting of The Lord of the Rings, thereby establishing a clear connection with the claimed model as well as providing an expanded experience of it. But the narrative plotting also seeks to identify with the conventions of the medium by emphasizing Aragorn’s action-figure characteristics and minimizing the other characters’ importance.

Finally, the centrality of the path of the king in the map identifies the gamer with both the title of the piece and the prominent placing of Aragorn on both packages. He is the most action-heroesque of the characters, and so demands a central role in a medium that values such action. The other two storylines are marginalized but are still present to retain the narrative cohesion of the adaptation’s model, and thus maintain the ethotic connection. The notion of ethos here indicates an authority garnered by association. In the case of The Return of the King’s plotlines, its structural similarity - its construction of itself in the terms of its adaptive model - produces a credibility or legitimacy. When we play the game we say, “Oh. This is just like that other Return of the King.” Given this association, the game becomes more “a part of the club” of texts that we deem Lord of the Rings. Generating ethotic credibility by identification is a process of standing out in a group: the text adopts enough of the structural elements of its model to be able to claim itself as genuine, but retains its distinctiveness enough to stand out of the crowd of other competing texts within the group. Bolter and Grusin (1999) touch on this struggle for credibility when they note that media “must enter into relationships of respect and rivalry with other media” (p.98). In the case of the parallel plotlines in EA’s Return, the marginalization to which I refer begins to strain the ethotic connection between the model and adaptation, as the major plotline and thematics of both the film and the novel reside with the Hobbits’ trek toward Mount Doom, whereas the primary narrative thrust of the game is through Aragorn’s kingly battles. The centrality of the “Crack of Doom” episode on the map may be an attempt to restore this thematic connection. But it is obvious that the thematic conventions of the gaming medium are, to a certain degree, at odds with that of its cinematic model. It is clear, by the number of episodes given to Aragorn, and the centrality of his plot line (both literally - as the centre line of the tree, and figuratively), that his is the focal point of the game.

But we must also account for divergences, supplements, or excesses in the game plot. Rarely do any games have one-for-one correspondence with the plot of the film to which they are attached. We should not expect any adaptation to achieve such correspondence, as the very notion of adaptation demands change - of mode, of message, of address, etc. Thus, as the medium shifts, so we must expect the constraints to alter the plot. In rhetorical terms, these changes and divergences adaptations make from the model are eurhythmatic, or the proper fit. The fitting adaptation is one that is modeled on a previous form, but conforms to the exigencies of its immediate audience, purpose and context. The eurhythmatic response to the problems presented by adapting a video game from a cinematic model is to diverge from the episodic elements of that model in order to maintain the model’s effects rather than its narrative strategies. In the case of the EA video games, the supplemental aspects of the game are ancillary to the “boss” stages. In the typical design of adventure gaming play, the games are divided into episodic units. There is usually an overarching game plot, or quest that breaks down into any number of episodes. These episodes usually have a super/subordinate organization where players move through various tasks, puzzles, or conflicts with lower minions until they reach a “boss” or ruler of that particular level, against whom players must test their skills before being allowed to proceed into the next episode. In The Two Towers and Return of the King, even when the ancillary gameplay diverges from the film, it logically sets up boss levels, drawn directly from the source, and which mirror it on the levels of both form and content. For example, in The Two Towers game, before gamers can confront the “watcher in the water” at the gates of Moria (a rather lengthy action sequence from The Fellowship of the Ring film), they must proceed through a swampy region where orcs, goblins and Uruk-Hai spring from the muck or leap out from behind rocks to challenge them. While these subordinate tasks do not appear in the films, they create a narrative cohesion to the conventions of the gaming medium. In fact, were the game-tasks in the film, they would cause significant plot problems for the cinematic narrative, as the tranquility of both the approach to Moria and the mountainous trek towards Helm’s Deep provide both the watcher’s and warg’s appearance with the power to terrify. Presuming the convention and audience expectation of the minion/boss episode in game design, the monsters that gamers would rightly expect to fight in an adaptation of Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings must have minions to precede them. For the battle with the cave troll in Dwalin’s tomb, the film provides adequate fodder for such a game scenario - orcs and goblins battle the heroes before the troll’s arrival, so this sequence in the game mirrors the film. But in the film version of The Two Towers, no minion encounter precedes either the watcher or the warg attacks. The game retains its own internal coherence by adding plot elements to the story. Quite simply, given the conventions of the medium, a faithful or moment-by-moment accounting of the film plot would have rendered the game adaptation less viable as an adaptation. The game diverges from its model’s plot, not because it is unfaithful, but because it is eurhythmatic to do so.

Additionally, the supplemental elements may also act as a kind of promotion for the “Special Editions” of the series. “The Mouth of Sauron” sequence occurs in both the book and the game but not in the theatrical release of Jackson’s The Return of the King. As the armies of Gondor and Rohan approach the black gate, the ambassadors of Sauron approach Aragorn to “negotiate:”

At its head there rode a tall and evil shape, mounted upon a black horse, if horse it was; for it was huge and hideous…The rider was robed all in black, and black was his lofty helm; yet this was no Ringwraith, but a living man. The Lieutenant of the Tower of Baradur he was and his name is remembered in no tale; for he himself had forgotten it, and he said: “I am the mouth of Sauron” (Tolkien, 1990, p. 922).

The Mouth shows Aragorn and Gandalf Frodo’s mithril shirt, stolen in the tower of Cirith Ungul, in order to break their spirits before Sauron’s final assault. In the novel, words are exchanged between king and messenger, but Aragorn refuses to be cowed and therefore drums the envoy out as the black gates open. In the video game Aragorn must fight Mouth, a truly difficult boss, in order to confront the hordes of Mordor [4].

What this act of distinction does is call attention to its absence in the cinematic production. A cleverly crafted promotional machine, Jackson’s Wingnut productions in association with Alliance/Atlantis made the delaying of “Special Extended Editions” of the films a part of their promotional strategy - the video games were released (in early December) before the theatrical versions of the film (just before Christmas), then a few months later, the video/dvd versions of the theatrical were released (in the summer), and then, in November, just in time for Christmas, the Special Edition Boxed Sets were released. The first two sets acted as promotion for the upcoming films, but the last boxed set required a certain consumer tension to keep audiences interested into November 2004. The hint of restored sequences in the video game serves this function of consumer appetite-wetting well. Players go to see the film expecting to see the sequences presented in the game in some form on the screen. When they are absent gamers begin to speculate as to whether the scene will be in the Special Edition and are consequently more likely to buy it in hopes of seeing this sequence realized cinematically, not just in a game environment. The inclusion of this promotional sequence acts as a challenge to the simple adaptation/source binary by adding yet another linkage of identification towards a familial relation. While the game overtly establishes the (theatrical) film as its authoritative model, at the same time it gestures to another version of the model text, hinting at the Special Edition’s possible figuration as the authoritative version - the Peter Jackson “authorized,” “true” version of the model. The game, in other words, works to expand the symbolic system of The Lord of the Rings title to include a wide cluster of texts.

Perspective as Associative Link

We tend not to think of the computer game as having a camera to angle, position, or otherwise shape images. But in The Fellowship of the Ring film (2002), Jackson begins with a prologue where he shows the first battle for Middle Earth: the armies of men, elves, and dwarves fought hordes of orcs and goblins under the control of Sauron. The majority of this sequence is computer generated - seemingly realistic characters battle, many in extremely close proximity to the “camera.” Yet, they are computer generated and controlled by a complex algorithm designed to simulate battle sequences - much like the algorithms that control video game NPC’s (non-playing characters). Similarly, the camera that “films” actors in video games is a virtual one. So, when we speak of the camera across media, we do not necessarily speak of the physical mechanisms that capture images, but, rather of the perspective of the image on the screen. We see the images and presume a physical device capturing them, but that device’s reality is by no means assured. While many video game adaptations wish to cultivate this association between the director’s camera and what gamers see on their screens, the term “camera” suggests an illusory objectivity [5], whereas the terms “point of view” or “perspective” appropriately illustrates that relationships on our screen are actively created, that associations are made, that ethos is cultivated and that identification is solicited by agents with purpose (both aesthetic and financial). Point of view, then, is an instrument of these profoundly rhetorical operations. So, while there is a cultivated resemblance between the cinematography of the film and that of the game-scene, the stylistics and strategies of representation should be considered as “perspective.”

So, when we address the particularities of perspective in video games, we must recognize that it can be, just as in film, a hallmark of a directorial style. As Andrew Sarris (1962) claims in his defence of Auteurism, “a director must exhibit certain recurring characteristics of style which serve as his signature. The way a film looks and moves should have some relationship to the way a director thinks and feels” (p. 7) . It would seem to follow as well, that one of the ways a video game could connect itself cinematically to its source would be to, at every turn, mimic and replicate those “characteristics of style” that designate, in this case “Peter Jackson-ness” [6]. This, cleverly, is what EA has done throughout both games.

What is especially notable is that these moments containing the “authorial signature” occur often at moments when the model/adaptation connections are the most strained. For example, as we noted earlier, there are moments when, for eurhythmatic reasons, the game diverges from the plot and narrative of the film, and must incorporate ancillary stages to justify the cinematic boss stages. In the battle in the mountains preceding the warg attack in The Two Towers game, the player’s interactive control of the character is broken by a cinematic moment where their arrow speeds across a gorge into the head of an orc. In placing a non-interactive, cinematic moment at this point in the game and by making it an integral part of every character’s movement through the pass, the game mimics the famous animistic moment in The Fellowship of the Ring film where the viewer sees the world from the perspective Logolas’s arrow as the characters escape down the crumbling steps of Moria toward the fateful bridge of Khazad-dum. Jackson, in order to demonstrate Legolas’s preternatural accuracy with a bow, follows the long path of his arrow into the head of an orc high above the fleeing fellowship. What is significant to note here, is that the Khazad-dum sequence, and therefore, the battle in the pass from the game are distinct creations - hallmarks of Jackson’s unique style. The flight down the steps to the bridge, the arrow, the throwing of the hobbits and Gimli, the falling of the steps are not in the novel, nor are they, according to Phillipa Boynes, even in the script, rather, they are directorial embellishments. The arrow perspective, transplanted into the game serves the function of stamping it as “of” Peter Jackson. So, what we see in the use of perspective in the video game is a keen attempt to provide the game with familial substance - a part of the real family of Tolkien texts, if you will - by replicating elements unique to the cinematic model.

Episodic Structure

For J.R.R. Tolkien, the model of his narrative structure was that of myth. His entire secondary world, explored primarily in The Simarillion (1977) and The Lord of the Rings, hinges on a series of episodic myths that create a pantheon and overarching ur-text. These episodes produce patterns of repetition and resolution through Tolkien’s principle of eucatastrophie, or “the good catastrophe, the sudden joyous ‘turn’” (1983, p. 153), which grounded all Tolkinian principles of “sub-creation.” The eucatastrophic event is the moment where the tide turns for the better. Therefore, the internal structure of mythic episodes can be easily marked by the narrative punctuation of the eucatastrophy. The structure of the EA games models this principle by using eucatastrophic moments to guide the larger work; players must experience a sense of hopelessness and despair that precedes the eucatastrophe so that they can feel the release and euphoria of both facilitating and then being agents of the eucatastrophe when it arrives.

Lisa Anne Mende points to three eucatastrophic moments in the battle of Minas Tirith: the arrival of the Rohirrim, the slaying “of the High Nazgul and the coming of Aragorn in the ships of Umbar” (1986, p.39). Each of the moments is signified by a turn from despair to joy:

Suddenly their hearts were lifted up in such hope as they had not known since the darkness came out of the East; and it seemed to them that the light grew clear and the sun broke through the clouds… ‘beyond all hope the Captain of our foes has been destroyed… (Tolkien, 1990, p. 890)

And then wonder took him and a great joy…upon the foremost ship a great standard broke…there flowered a white tree, and that was for Gondor; but the Seven Stars were about it, and a high crown above it, the signs of Elendil…Thus came Aragorn (p. 881)

As Gandalf, the Return of the King gamer must endure the seemingly hopeless task of defending Minas Tirith, awaiting the arrival of Rohan (as in figure 2). In this case, the action is a process of progressive retreat - Gandalf must successfully defend the walls by fending off enough orcs, and defeat a Nazgul, in order to “succeed.”

Figure 2: Gandalf’s Battle for the Walls of Minas Tirith

But success, in the terms of this game sequence, is in real terms a defeat. While the usual gaming scenario conflates task success with victory, the measure of success here is extremely limited - the gamers may succeed in their task as Gandalf, but the net result is the loss of the wall. Similarly, as Gandalf moves into the courtyard, the task becomes to ensure the safe retreat of civilians (at least 200) as he battles orcs and finally trolls. The only plausible explanation for this inversion is the intentional subsuming of gaming conventions to that of adaptive narration. In his essay “Imitation and Invention in Antiquity: An Historical-Theoretical Revision” (2003), John Muckelbacheur examines the ancient philosophy and practice of mimesis, noting that in one form (imitation-as variation), the adaptation is obliged to “reproduce the effect of the model” (p. 79) as opposed to its constituent elements. Thus, the plot of the game, tied as it is to that of the film, must effectively reflect the Tolkienian principles of eucatastrophe, and therefore, gamers must have a sense of relief at the arrival of Rohan through cinematic interlude, or more significantly, through the gameplay sequences of Aragorn’s arrival in the black ships and Eowyn’s slaying of the Witch King.

Through these two instances, the battle at the southern gate of Osgiliath, and the battle of Pelinor fields, the game inverts the narrative sequence [7] in order to retain the sense of game-agency, while at the same time, providing the relief of eucatastrophe. EA displaces some of the supernatural power of Aragorn’s arrival as represented in the film and novel in order to make it more agent-oriented in gameplay - Aragorn does not herald the routing of Mordor at the hands of the dead or the men of the north, but becomes simply a means by which Eowyn can safely slay the enemy captain. The moment of eucatastrophe, then, is shifted away from the king’s arrival to the defeat of the enemy through the symbolic figure of its leader. This pattern is, of course, in keeping with the video game conventions discussed earlier: the gaming goal is not the restitution of the line of Isildur as the name suggests, but the more direct matter of the defeat of the enemy. Additionally, the patterns of gameplay suggest a progressive movement though smaller tasks to the larger resolution - in this case, the resolution of gameplay is not direct, but intermediary - the final victory of the Pelennor fields comes not at the hands of Aragorn (or in this case, the gamer) as is credited in both the novel and film. Rather, the player, through Aragorn allows Eowyn (an automated character) to defeat the Witch King in an interlude in which the gamer cannot participate.

The point here is not to diminish the role of Aragorn; in fact, the structure of the game only augments the Aragorn role by keeping his final, kingly victory until the black gates. In the novel and film, Aragorn’s victory at Minas Tirith is a prelude to the seemingly hopeless struggle at the Black Gate. Aragorn is the “hero” of the day both times, but while he is the vehicle of eucatastrophe at Minas Tirith, it is the Eagles and Frodo who are the eucatastrophic elements in the episode at the Black Gate. Again, this will not do for the conventions of gameplay. Aragorn, as the central character of the series (both the EA Two Towers and Return of the King games), must be at his most heroic at the gate - the final place where we see him as a game-character. Therefore, his final success is deferred from the Pelennor Fields to the Black Gate in order to produce a maximum gaming eucatastrophe - the victory of The King on the field of battle. Again, the eurhythmatic response is to alter the narrative emphasis of the game in order to maintain the model’s eucatastrophic effects rather than its exact narrative strategies.

Thus, the Electronic Arts Lord of the Rings games perform two significant actions simultaneously in order to garner credibility: 1) it clearly claims the Peter Jackson films as its primary model, primarily by means of plot overlapping and the rhetorically consubstantial use of “Jackson-esque” visual perspective, and 2) it allows for eurhythmatic flexibility between the video game and its source in order to replicate the narrative effects of the film, rather than the narrative itself.

The Vivendi/Tolkien Estates Games

Even before Electronic Arts began to release the Official Film versions of Lord of the Rings, the Tolkien estate licensed Vivendi Universal Games to develop a line of games in order to compete with Jackson’s, based directly and wholly on the literary texts of The Hobbit, The Fellowship of the Ring, and The Return of the King (but changing the game title to The War of the Ring). Each of the texts, just as the EA Lord of The Rings series, achieves its official status by a medallion and stamp of approval. In this case, the approval is not from Jackson and New Line, but from the Tolkien estate, thus lending a sense of the authority of the “original,” reflected in the design of the seal. Furthermore, the packaging and gameplay design of each of these texts, rather than drawing upon the ready-made ethos of the film genre and adapting to it, draws upon the traditions and designs of some of the most successful titles in the gaming world in an attempt to adapt the subject matter of each classic novel to a corresponding classic game style. In fact, Vivendi has specifically tapped three leaders in the game design world to adapt each of their best-selling products to the Tolkien universe, thereby creating stronger connections to gaming conventions than to the overtly stated source: Sierra, Black Label Games, and Liquid Entertainment.

Each of Vivendi and EA series seeks to distinguish itself from the other and stake claim to authenticity - to the authority of an original model. The function of the term “official” on each of the Vivendi and EA packages (as well as the gratuitous visual portrayals of all the action figures of the New Line films on the EA boxes - Legolas, Gimli, Gandalf, and Aragorn as the central figure on both) serves this purpose. So, while each are attempting to identify themselves in the terms of Tolkien’s masterwork, they are also attempting to distinguish themselves from one another - the authority of the Vivendi games’ association with the person of Tolkien is at the expense of the more “low” and populist association of EA with the films. The authority of a Tolkien-estates licence association is no small matter. Such a model-claim places its texts ahead of a significant body of similar (if not superior) products; as one game review directly states: “Put simply, if it wasn't for the attractive license, we'd have probably filed this game under ‘don't bother even looking at’" (Reed, 2002). Thus we see demonstrated by the Vivendi line, an attempt to privilege one video game series based on its direct, familial relation with a classic, literary text, and against a different media form - the film. This familial distinction can be seen through the rhetorical lens of the scapegoat, or the means by which agents change their identities by means of the annihilation of the other. Most often, the scapegoat represents an attempt to distinguish between parties, aspects or elements that are so close as to be considered familial:

We should also note that a change of identity, to be complete from the familistic point of view, would require nothing less drastic than the obliteration of one’s whole past lineage. A total rebirth would require a change of substance. (Burke, 1989, p. 295)

In the terms of The Lord of the Rings games, in order to establish its uniqueness, the process of branding must either repudiate its past (in an act of patricidal revision) or its future (in sacrificial infanticide).

Figure 3: The Vivendi Universal Games/Tolkien Estates Official Seal www.sierra.com

Figure 4: Electronic Arts Official Seal www.ea.com

The medallion which graces the bottom centre of each of the Vivendi games (figure 3) distinguishes itself from the holographic sticker on the EA products (figure 4). Its archaic and ornate script, and the appearance of age make an obvious distinction between it and its competitor, as the EA design is unique in its holographic design of a three-dimensional ring set into the round marker. The two, the archaic Vivendi and the technologically secure EA, are as distinct as they can be in order to mark their authority of source. Because EA draws from its filmic source, its “official marker” is expected to be a part of the technological apparatus it claims. But the ornate and archaic Vivendi draws visually upon the mythic through its script, oblong shape and elfin design; it demands the authority of the “original source” of Tolkien, the linguistic, the mythic, in direct contrast with Jackson, the cinematic, the technological. As Burke points out, this vilification of the adaptive emanation creates a certain irony of obliteration - in generating its power in the position of text against film it undercuts the familial relationship between the film and the game. Just as siblings fight bitterly for the approval of their parent, Vivendi seeks to symbolically erase Jackson’s textual presence in the Lord of the Rings family by questioning his devotion to Tolkien. The Vivendi games, then attempt to obliterate their indebtedness and relationship to film (specifically, the films that constitute The Lord of the Rings adaptations, not just Jackson’s, but that of the animated renderings of The Hobbit - by Rankin/Bass’ in 1977 - and Lord of the Rings - by Ralph Bakshi in 1978) for the sake of a direct consubstantiality with the original source. The association, then, calls out to discriminating gamers, declaring that if they care about legitimacy, then the Vivendi games are the only ones recognized by the God term “Tolkien.” This ironic assault on the legitimacy of the competing game attempts to obliterate the very factor that allowed it to succeed in the first place. It is no coincidence that Vivendi’s Fellowship of the Ring was released right before the Jackson film version of the same text. The quest for legitimacy by means of audience-recognition creates fascinating paradoxes such as this one: using the release of a text from which they chose to distinguish themselves, Vivendi attempts to supplant the film’s ethotic power for the pedigree of the book.

Each game in the Vivendi series is cleverly linked to a style of play that corresponds to the thematic structure and interpretive consensus about the literary text. Sierra’s The Hobbit links its game to both the novel and the style of play associated with the Zelda series. We can identify this from the outset as the image of Frodo on the packaging and within the game itself bears a curious resemblance to Link, the child-like, elfin main character of the Zelda series: “Bilbo is depicted with the gigantic eyes and the physical proportions of a child. He looks and moves like a four-year-old human, not a 50-year-old hobbit” (Bennett, 2003). The universal critical consensus was twofold: first, that The Hobbit was wholly rigorous to the plot of the text, careful to hit every narrative point: “players [follow] the events from Tolkien’s book, chapter by chapter. Except for a few minor twists in the plot here and there, nothing was put in to alter the main story” (Paul, 2003). Second, that the platform was deeply dependent upon the conventions of the medium - specifically the youthful adventure set, typified by Zelda, and Sonic the Hedgehog: “In terms of its action, The Hobbit seems more inspired by the Sonic Adventure Series games than the novel it's named for -- unless I missed the part where Bilbo runs around the Shire collecting coins and colourful jewels that magically jump into his pockets” (Bennett, 2003). Thus, just as the original Hobbit was intended for children, so the video game draws upon the conventions of the scrolling, youth adventure games as a base. This process of dual connection achieves goals already attained at the outset by the EA franchise: on the one hand, its overt, legal association with the name Tolkien gives it a authority it would otherwise lack. This coupled with the narrative emphasis of the gameplay give us a sense of its adaptive “authorship” - i.e. if Tolkien had made games himself, these would have been the ones he would make. On the other hand, the game draws on the conventions of its own medium by layering the narrative over an easily recognizable - even expected - style of gameplay, thereby modeling an age set for which the original story was designed.

Similarly, Black Label Games’ The Fellowship of the Ring replaces a dependence upon film convention with both a relentless episodic rigor and gameplay design that draws upon significant video game platforms, specifically, the traditional RPG. The role-playing game model is a third person one where the game-player moves a character, controlling them from a vantage (usually from behind, but with the advent of the complete 3-D environment, multiple vantages are possible). Based on a “Dungeons and Dragons” type system, the character is usually allotted various “points” for health (which deplete when the character is attacked, poisoned, or otherwise incapacitated), magic, etc., and a means by which some form of monetary exchange is calculated (gold, usually). The inspirations for this model are the Final Fantasy or Baldur’s Gate series, or more specifically, Black Label Game’s own Enclave. The game is designed as a rigorous attempt at textual fidelity, even going so far as to force changes of main character on the gamer to accommodate for Tolkien’s episodic foci. Depending upon the narrative focus of each of Tolkien’s episodes in the novel, the game automatically changes the main character [8].

We note here how rigorous adherences to a model can, contrary to many assumptions, produce an eurhythmatic defect: the adaptation does not account for its new audience, purpose and context. In this case, “the biggest problem with Fellowship, though, is that it follows the book too closely. …for the most part, anyone who knows the story knows what's coming up next. It would be like basing a game on The Bible” (Steinberg, 2002). Whereas EA adapts its overall plot to better suit the conventions of its medium, Vivendi elects to “take the high road” of fidelity. But in a sense this is in keeping with the cultivation of authority from Tolkien, as distinct from Jackson. The very adaptation of the film was and is fraught with controversy over what plot elements, characters, lines, etc. were selected to represent. Jackson very overtly and publicly made choices based on the medium in which he works: the film and book are related but distinct works. Conversely, Vivendi attempts to produce authority by a wholesale veneration of its model at the expense of gaming conventions.

The War of the Ring, by Liquid Entertainment continues this dual dependency of convention and model - if anything the dependence on the gaming conventions is more pronounced. The textual association drifts into the background, if only because of the radical divergence of the narrative form of the novel versus the “real time strategy” style of game play. The previous incarnations of the Vivendi series feature, by all accounts, an overt connection with the literary works of Lord of the Rings, in direct opposition to the films:

If there’s any other game that War of the Ring would thank on Oscar Night, it would undoubtedly be Warcraft III. The palpable influence of Blizzard’s RTS tour-de-force is felt throughout the War of the Ring’s experience, and from the menu interface to the bright colourful world it assists you in interacting with, it’s clear to whom War of the Rings owes its debt of inspiration. (Cervantes, 2003)

This particular adaptation takes the significant battles of the second half of Lord of The Rings as its inspiration, so rather than directing individual characters, gamers direct armies in strategic manoeuvres that pit them against their opposite in the story. So, if a gamer chooses to battle with the forces of good, then Rohan and Gondor, accompanied by Gandalf and Aragorn, move against Mordor and the Easterlings. The forces of good lay siege to the Black Gate, and gamers can use magic to summon some of the background races from the series, such as Ents or Eagles. Mordor, similarly, can summon Balrogs and Trolls. The focus then, for this game, is not the text, as such, but transplanting the associations of character and monster to a preset system. The text, in this case is little more than an overlay expansion kit to Warcraft. The way the narrative model is replaced by a environmental suggestion corresponds to Henry Jenkins’ presentation of the “evocative space,” where elements of the game point to or gesture at the source, rather than providing any fixed narrative frame, the way say EA’s Return of the King, does: “Such works do not so much tell self-contained stories as draw upon our previously existing narrative competencies. They can paint their worlds in fairly broad outlines and count on the visitor/player to do the rest” (Jenkins 2004).

As loose as this textual connection is, the success of this game adaptation genre cannot be understated; EA’s version of the same real-time strategy platform titles The Battle for Middle Earth I & II (2004 and 2006 respectively) and The Third Age (2004) have been modestly successful even though they have been handicapped by release dates years after their direct cinematic models. The Tolkien Estates, following the franchise lead of Star War Galaxies, has recently licensed the rights to a MMOG (Massively Miltiplayer Online Game) entitled Lord of the Rings: Shadows of Angmar (2007) to compete with highly successful platforms like Everquest and World of Warcraft. So even though the ethotic connection is tenuous - character and plot are reduced to mask, title and/or single episode - the hailing power of the platform type and gameplay style, coupled with the most slight of connections to a model can produce an adaptation that can succeed; what is more important than the fidelity of the association is the use of the conventions of the new media form, again, eurhythmatically. Thus ethos is produced by a ratio of elements produced by both the model and adaptive media.

Thus, while EA draws its primary ethos from a source already replete with credibility by virtue of its popular appeal (Jackson’s films), the Vivendi/Tolkien Estates games must generate their credibility by a process of identification and division by means of scapegoating. They divide or distinguish themselves from the EA/Jackson texts by appealing directly to the Tolkien texts for authority, thereby scapegoating Jackson’s work as secondary, or diminished. Vivendi then strives to claim identification with Tolkinen’s oeuvre by means of their iconic representation and rigorous plotting over highly recognizable gaming styles and conventions.

Conclusion

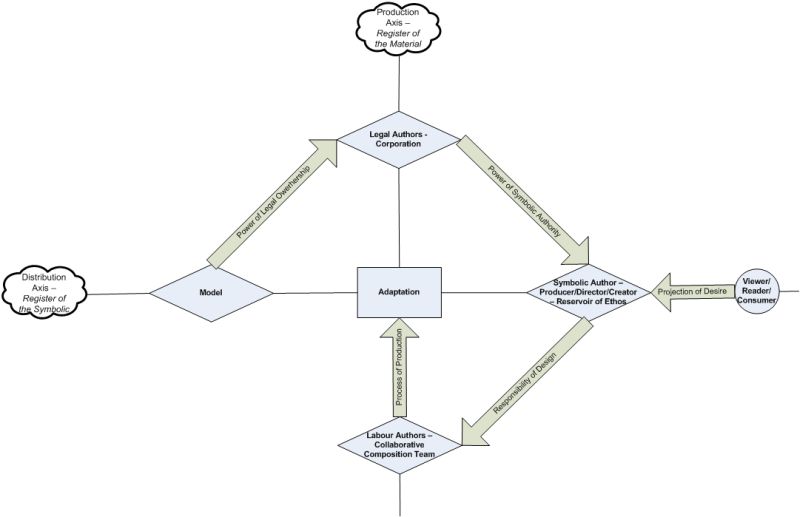

Because of the unique nature of their overt associations, adaptations are profoundly concerned with establishing their own legitimacy. This legitimating process may take several different forms. Critical and historical forces operate to legitimate the process by which texts are adapted for new and different media. But just as ethos is the dynamic force that conjoins authors and texts, so it creates relationships between models and new textual instantiations. These ethotic connections can be described in terms of identification and division, or the process by which agents produce associations and establish distinctions. The Lord of the Rings video game incarnations use form, content, and their transtextual material to establish credibility with their audiences. They do so by clearly identifying their models and hailing audiences who value these associations; drawing upon the conventions of the adaptive medium to ease the transition between media as well as fulfill audience expectation, thereby establishing a fusion of narrative and interactive forms; and by creating distinctions between their text and the other texts available. These overt connections with their sources achieve the effect of providing authorship to an otherwise unauthored text. That is, the audience’s desire for an author-figure - a symbolic author as a reservoir of ethotic power - must be fulfilled, and so instead of producing a faceless programmer, or even a subculture media figure, Electronic Arts and Vivendi have both chosen to have their models act as the authors of the text. But how can a text be the author of another text? The fact is, the conflicting pressures of multi-national corporate ownership, collaborative design, and audiences weaned on presumptions of cinematic auteurism have split the new media author into three distinct figures: 1) corporate legal authors who control tangible rights to new media texts, 2) labor authors who design the texts (behind the scenes, in relative obscurity, and for little pay), and 3) symbolic authors, or high-profile managers who emerge as the public face of collaborative new media texts, much the same as directors do of collaborative cinematic texts. Consumers project their desire for a singular author-figure into the marketplace and legal authors seek to fulfill that desire by putting forward symbolic authors to take credit or blame for the work of the labor authors. But when we add the additional variable of the text being an adaptation, as we have seen, the model is always brought forward to speak for, to account for and to vouch for the adaptation. In other words, the model is claimed by the legal authors as a symbolic co-author. Figure 5 represents these relationships:

Figure 5: Cycle of Adaptation Ethos

In the case of the Lord of the Rings video game adaptations, we are invited to presume that these adaptations naturally spring forth from their models, created from very essences of Peter Jackson’s (in the case of EA) and J.R.R. Tolkien’s (in the case of Vivendi) minds. We are, in other words given authors by proxy in the form of texts.

When we clearly identify that ethos is generated through a complex process of identification and division, certain interpretive strategies begin to emerge. What is obvious is that the EA game line draws upon Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings as its direct model, rather than Tolkien’s texts. The proximity of the gaming and film cultures makes the marketing choice an easy one. But what is not so readily apparent is the complex network of relationships these games create in spite of their overt connection: by directly identifying with and referencing the film, EA must simultaneously distinguish themselves from all other instantiations. These adaptations create subtle identifications between themselves and films, directors, other game designs, and even the complex mythological systems of Middle Earth that exist independently of any overt association with either the novel or film versions of The Lord of the Rings. This is the paradox of adaptation: on the one hand, it seems a simple matter of identifying a model and analyzing the connections between it and its adaptation. But what the rhetorical principle of identification teaches us is that the authority an adaptation seeks to produce, particularly a culturally marginalized new media adaptation, is not a straightforward matter of one-to-one correspondence, but rather a complex of attempted (and sometimes failed) consubstantiations and scapegoatings of symbolic authors, models, and textual conventions. What we find in the end is that the notion of adaptive authority is vested firmly in the rubric of the symbolic order - that agents weave complex networks of association which work at the symbolic level to produce creditability and authority for their texts in order to simultaneously associate their texts with earlier media forms that emit a cultural resonance (or inspiration), while at the same time distinguishing their text from competitors who seek to capitalize on the same rhetorical moves.

Endnotes

1)Apologies to Sid Meyer, Chris Trottier and Will Wright, John Carmack, David Perry, Rand Miller, Toby Gard, Shinji Mikami, and Hironobu Sakaguchi. While all these figures are well-known in gaming circles, they have yet to achieve the mass-marketability of the “auteur.” But the day of the auteur game designer may come sooner than we might think.

2)Paronomasia is a type of play or pun. I use the term here to suggest the way adaptations frequently play with an audience’s knowledge of and associations with previous adaptive instantiations, beyond the level of allusion. In film, such play often occurs at the level of casting. For example, in the case of The Lord of the Rings series, the casting of Christopher Lee in the character of Saruman is a type of semiotic pun, drawing well-versed viewers through a wide range of associate linkages with his many other Saruman-like roles, such as the seemingly benign and noble character of Lord Summerisle in The Wicker Man. In a paronamasic sense, because of his long and pronounced history playing precisely these types of characters, Lee is playing Saruman, acting like himself - at least, our associations with the persona that emerges from Christopher Lee’s oeuvre.

3)Tolkien’s notion of the secondary world posits that the creation of the fairy story differs from other forms of narrative in that it must produce in its readers something more than the wilful suspension of disbelief. Because the author of the fairy story must create a world with laws unlike the one governed by modern realism, the author (or “sub-creator”) must design and slavishly adhere to the internal laws of the world in the story. If the sub-creator breaks the laws, the illusion that suspends the reader is shattered and the effect of the secondary world will be lost. Tolkien’s passages of long description with minute details of setting demonstrate his theory: because Tolkien is the literal creator of the world of Middle Earth, he must clearly and thoroughly express the properties of that world. The setting, therefore, almost subsumes character in the secondary world’s demand for expression. Tolkien’s theory of the sub-creation and secondary world are outlined in his essay “On Fairy Stories” in The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays (1983).

4)The Mouth presents a variation on the usual game order of minion/boss, changing the climax of “The Path of the King” plot to a boss/minion/boss pattern for the EA Return of the King video game.

5)The purported (but illusory) objectivity of the photograph and the moving picture has been widely discussed in essays ranging from Brecht’s rather hopeful materialist manifesto “The Film, the Novel and Epic Theatre” [(1964). In J. Willett (Ed.), Brecht on Theatre. New York: Hill and Wang.], to Barthes’s deconstruction of the image in “The Photographic Message “[(1988). Image, music, text. London: Fontana.].

6)While some may question the connection between game designers and auteur directors, the growing numbers of gamers may yet elevate these figures into household names, just as the explosive popularity of the cinema after World War II gave rise to the first auteurist movement. I discuss the problems confronting the growing phenomena of the game design auteurist in “Reservoirs of Ethos: Symbolic Authorship and the New Media Adaptation.” Rhetor: Journal of the CSSR. Vol. 5. pp. 44-57. http://www.cssr-scer.ca/journal/volumes/rhetor-vol-5/.

7)In both the novel and the film, the slaying of the Witch King precedes the arrival of Aragorn on the black ships. For Tolkien, the progression of joy culminates in the King’s arrival, rather than the defeat of the captain of the enemy.

8)This of course, differs significantly from the EA version of The Two Towers and Return of the King where gamers are given a set of options for their main character (Legolas, Aragorn, Gimli, etc.) so that they can play out the same narrative several times with different characters.

References

Bennett, D. (2003). Review of "The Hobbit". Gamespy. Retrieved August 9, 2004.

Black Label Games. (2002). Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. New York: Vivendi Universal Games.

Bolter, J. D. & Grusin, R. (1999) Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Boyens, P. (2002). Audio Commentary Track [Lord Of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, Special Extended Edition]. New Line Cinema.

Burke, K. (1989). In Gusfield J. R. (Ed.), On Symbols and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cervantes, M. (2003). Review of “Lord of the Rings: War of the Rings.” Game Chronicles. Retrieved August 10, 2004.

Electronic Arts. (2004). Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King. Redwood City: EA Games

Electronic Arts. (2002). Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers. Redwood City: EA Games

Jackson, P. (2002). Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. Special Extended DVD Edition. New Line Entertainment, Inc.

Jackson, P. (2004). Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King. Special Extended DVD Edition. New Line Entertainment, Inc.

Jackson, P. (2003). Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers. Special Extended DVD Edition. New Line Entertainment, Inc.

Jenkins, H. (2004). Game Design as Narrative Architecture. Electronic Book Review, 3. Retrieved August 7, 2004.

Liquid Entertainment (2004). War of the Ring. New York: Vivendi Universal Games.

Mende, L. A. (1986). Gondolin, Minas Tirith and the Eucatastrophe. Mythlore, 48, 37-40.

Muckelbacheur, John. (2003) Imitation and Invention in Antiquity: An Historical-Theoretical Revision Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric. 21/2. 61-88

Paul, U. (2003). Review of "The Hobbit". Gamezone Online, Retrieved August 9, 2004.

Reed, K. (2002). Review of “Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring.” Eurogamer. Retrieved August, 10 2004

Sarris, A. (1962). Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962. Film Culture, 27, 1-8.

Sierra Entertainment (2003). The Hobbit. New York: Vivendi Universal Games.

Steinberg, S. (2002). Review or “Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring”. Gamespy, 20. Retrieved August 10 2004.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1983). On Fairy-Stories. In C. Tolkien (Ed.), The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays. (pp. 109-161). London: George Allen and Unwin. Tolkien, J. R. R. (1990). The Lord of the Rings (One Volume Edition ed.). London: Grafton.

Wallin, M. R. (2013). "Reservoirs of Ethos: Symbolic Authorship and the New Media Adaptation." Rhetor: Journal of the CSSR. Vol. 5. pp. 44-57. http://www.cssr-scer.ca/journal/volumes/rhetor-vol-5/