Quests in Context: A Comparative Analysis of Discworld and World of Warcraft

by Faltin KarlsenAbstract

Within the field of computer game studies, quests are often described as a structural entity intimately connected to games. The quest is usually also seen as a functioning whole - as a substructure within a larger game area. However, these analyses usually pay little attention to contextual elements, like other parts of the game mechanics. Another topic seldom analysed is the motivation of players to solve the quests, and the producers to create them. The main goal of this article is to investigate how quests relate to, and are influenced by, different contextual elements. Three contextual elements will be discussed: the producers, the players and the overall game environment. My analysis shows how these elements influence the way quests are designed, how they are used and also what meaning-production and aesthetics they might be subject to. The analysis is comparative and the MUD Discworld and the MMORPG World of Warcraft are my two objects of analysis. The bulk of my material consists of interviews with developers and players of the MUD Discworld, as well as information from the official game sites of Discworld and World of Warcraft.

My analysis shows that quests fill different roles and have different positions within the content hierarchy of the games, both with regard to difficulty level, playing ethos and artistic expression. In World of Warcraft, quests are mainly an easily accessible and temporary occupation while advancing toward the maximum level. In Discworld the quests are hidden in the environment and employ syntax or actions that are often unique to each quest. While the developers of World of Warcraft furnished an instrumental approach, the developers of Discworld tried to prevent this kind of approach by restricting dissemination of information related to their quests, first by relying on social mechanisms, later through game mechanical means.

Keywords: Quests, MUDs, MMORPGs, World of Warcraft, Discworld, players, developers, co-production

Introduction

Within the field of computer game studies, quests have been the object of just a handful of analyses and theoretical exercises (Tronstad, 2001, 2004, 2005; Tosca, 2003; Aarseth, 2003, 2005; Rettberg, 2007, 2008). Some studies have focused on the relationship between quests and narratives, like Jeff Howard's recent study Quests: Design, Theory, and History in Games and Narratives (Howard 2008). The majority of studies approach quests as a structural entity intimately connected to games and, in most cases, the quest is seen as a functioning whole - as a substructure within a larger game area. However, these analyses pay little attention to elements that surround the quests and that stand in relation to them, like other parts of the game mechanics. Another topic seldom analysed is the motivation of players to solve the quests, and the producers to create them. One exception is Susana Tosca who, in the paper The Quest Problem in Computer Games, reminds us of the importance of separating the perspectives of the player and the producer. For the players, she writes, quests are first and foremost a semiotic challenge, whereas for the producers they are structural elements that are intended to limit the users' range of choice (Tosca, 2003).

The main goal of this article is to investigate how quests relate to, and are influenced by, different contextual elements. I will, broadly speaking, discuss three contextual elements: the producers, the players and the overall game environment. I will analyse how these elements influence the way quests are designed, how they are used and also what meaning-production and aesthetics they might be subject to. The analysis is comparative and the MUD Discworld and the MMORPG World of Warcraft are my two objects of analyses. The bulk of my material consists of interviews with developers and players of the MUD Discworld, as well as information from the official game sites of Discworld and World of Warcraft.[1] Quests from the games will be used as illustrations.

MUDs are a close relative to MMORPGs with regard to game mechanics and structure, and they are both inheritors of another relative, the fantasy role-playing game. The reason for my comparative approach is to contrast two games that, although being representatives of the same wide genre, have significant differences with regard to gameplay. My comparative approach will also show the plasticity of the quest element and how it can be shaped by different contextual settings.

Earlier Research on Quests

In her PhD thesis Interpretation, Performance, Play, & Seduction Ragnhild Tronstad offers a thorough analysis of quests from the MUD Tubmud. Inspired by Baudrillard's concept of seduction, she explains that the player has to be willing to be seduced by the text to be able to properly engage with the quest. She writes that:

Every discourse contains something that will evade interpretation, and everything evading interpretation may function seductively: including the MUD quest, starting out as a total enigma. Everything in the description of the room may be significant - and at the same time, nothing really is significant. Nothing leads anywhere at this point. When a player doesn't know where to start, every insignificant word may successfully fake significance. Gradually, though, the initial stage of helplessness is overcome, through examination, exploration, and interpretation (2004: 158).

In the MUD she examines, the quests are constructed as riddles that must be solved through exploration by the player. Tronstad regards quests as sub-games and states that there are: "rules governing each particular sub-game where they define the procedures that lead to a situation where the player either wins or loses the game" (Tronstad, 2004: 29). Hence, the MUD quest can be separated from the overall game as a functional entity of its own. What her analysis shows is that the enigmatic character of the quests is to a certain degree tied to, and dependent on, their uniqueness. Each quest, in spite of being easily recognisable as belonging to the same family of riddles, stands out from other quests by employing an idiomatic set of rules, a specific syntax or a new set of challenges. Experiences with other quests will only provide the player with basic tools for solving new quests, and the method of solving will still be through "examination, exploration and interpretation". In contrast to this, we see Espen Aarseth's more general approach when he states that:

Quests are a basic, dominant ingredient in a number of types of games in virtual environments, from the early adventure games to today's massive multiplayers, and by understanding their function and importance for game design and game aesthetics we can contribute to many of the current debates in game studies, such as the question of genres and typologies (2005: 1)

Aarseth virtually starts at the other end of the spectrum from Tronstad. Unlike Tronstad, who does close analyses of single quests, he zooms out trying to capture the most general traits of quests. Aarseth underscores his structural approach by stating that: "it is on the grammatical level that we must look for structure and design principles." (2005: 2) On the basis of this approach he offers two different definitions of quest games, the most elaborate of which states that it is:

a game with a concrete and attainable goal, which supersedes performance or the accumulation of points. Such goals can be nested (hierarchic), concurrent, or serial, or a combination of the above (Ibid)

In his search for the basic building blocks of the quest, Aarseth further distinguishes between three basic quest types: place-, time- and objective-oriented quests. A typical place-oriented quest would imply getting to a specific location, such as finding your path through a maze in a first person shooter game. He explains that most quests consist of a combination of these categories and can, for instance, imply retrieving an item from a specific location within a limited amount of time. A weakness with Aarseth's categories is that they are indeed very general and his "grammar" too crude. This is not least evident in his other definition of quest games that reads as follows: "a game which depends on mere movement from position A to position B." (2005) Even his first definition of a quest game is more or less all-embracing, as most activities in computer games could be labelled space-, time- and object-oriented. The open-endedness of both definitions makes it hard to distinguish between quests as a specific sub-structure and other game elements that might be subject to goal oriented activities. In contrast to this, the quest analyses conducted by Tronstad clearly focus on sub-structures and not on general game goals. The quests in these analyses will also be easily identified as quests by the player community as distinguished from other types of game content. What I find most convincing in Aarseth's approach is that he might be right in assuming that there are some basic elements of quests that exist in a wide variety of computer game genres. A more systematic examination of different game genres would probably establish better data concerning this.

What Tronstad and Aarseth have in common is a focus on the structural, textual and aesthetics traits of quests - basic questions concerning what a quest is and how it functions. This perspective also seems to be predominant in the discourse surrounding quests in the writings of Jill Walker Rettberg. In her article "Quests in World of Warcraft: Deferral and Repetition" (2008) she examines quests in World of Warcraft as rhetorical structures and argues that "studying the structure and dominant pattern of quests in a game gives us access to some of the basic patterns of the game itself" (Ibid: 168). Although this structural approach has its own merit, my approach is rather the opposite of Rettberg's: my aim is to highlight how contextual elements influence how quests are perceived, designed and used. Rather than trying to find the essence, the grammar, of the quest, I will highlight the plasticity of the quest feature.

Quests in Multiplayer Games

Persistent games as MUDs and MMORPGs do not have any definite goal as part of their structure and would for that reason fall outside Aarseth's definition of a quest game. Quests are, however, a prominent feature of this genre of games. The definition of quest I will use in this analysis is one that is identifiable by the MUD and MMORPG community, and is to a lesser degree informed by an aesthetic, ontological academic discussion. A quest is, in these terms, a special mission that the player engages in, that requires a specific set of action to be performed, that has a definite ending point with some sort of reward. As such, the quest is an easily identifiable sub-structure within the larger media frame. Solving these quests by questing will also be recognised as a separate gaming activity that differs from mere killing and exploring. A quest can structurally speaking fulfil Jesper Juul's classic game definition (Juul, 2005, p.36), but is not usually regarded as a stand-alone game by the gaming community [2]. However, this self-contained structure illustrates why quests often are regarded as "mini-games" and highlights an ambiguity in Juul's classic game model.

Quests in World of Warcraft

Questing is one of the core activities in World of Warcraft, especially when the player is levelling an avatar, as quests normally give a substantial amount of experience points. During my research I have levelled several avatars from different classes, and two of them to the maximum level of 70. Since questing even for a researcher is essential for fast levelling, I have probably completed hundreds, if not thousands, of quests. The most comprehensive online resource regarding quests lists a total of around 6000 quests from World of Warcraft.[3]

In World of Warcraft a quest is a task normally given by an NPC that yields different types of rewards when completed. As long as the character has not reached the maximum level of 70, all quests give experience points when completed. In addition they can reward the avatar with a small sum of money or an item that can be consumed or used as equipment by the avatar. Item rewards are normally armour or weapon items of common quality, but recipes for professions that the avatar can learn might also be given as rewards.[4] Some types of quests also increase the avatar's reputation with a specific faction of NPCs in the game. A higher reputation with these factions gives the avatar access to items that can be bought from representatives of that faction. In general, the quests in World of Warcraft are multipurpose: experience points might normally be regarded as the most important rewards, but money, items and reputation might be just as important for players at certain points.

Finding quests in World of Warcraft is straightforward, as the NPCs that give quests, also known as quest givers, are marked by a large yellow exclamation mark over their head. When a quest is completed, the exclamation mark will be substituted by a yellow question mark [5]. As most aspects of the game, quests are level-coordinated. In this case there are level restrictions as to when a quest can be obtained. This ensures that the players will not engage in a quest that may be impossible to complete, but on the other hand, it also ensures that the players will not get hold of quest rewards that are beyond their level. When a quest is finished, the NPC with the reward will also be indicated by a yellow dot on the mini-map in the user interface.

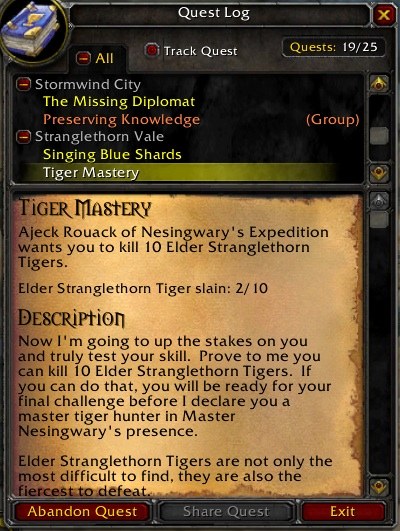

Figure 1: Quest givers in World of Warcraft

The simple semiotic systems surrounding quests in World of Warcraft. From top left: 1) Quest giver with a quest ready. 2) Quest giver with a reward for a finished quest. 3) Quest giver with a repeatable quest. 4) Quest giver with a reward for a not yet completed quest. 5) Quest giver with a quest too high a level for the avatar.

Quests in World of Warcraft are, structurally speaking, quite homogenous, or, as Rettberg explains: "Quests in World of Warcraft have a very clear syntax. The basic parts of a quest do not vary: Quest-giver, background story, objectives, rewards." (Rettberg 2008: 168). These quests could possibly be categorised and sorted according to a "grammar" after Aarseth's fashion, since, to a large degree, they are based on a limited set of building blocks. The information site wowwiki.com lists a total of ten different quest types in World of Warcraft, but even these might be considered to be sub-categories of even broader types, such as killing and exploring quests. I will now briefly describe some of the quest types in World of Warcraft.

Most quests include either the tasks of killing a specific number of monsters or collecting one or several items, either from monsters or from some specific location. So-called delivery quests ask the player to deliver a specific item to an NPC at another location. These quests often take the character to a new zone or a new area and therefore serve as vehicles for further exploration of the game. Another quest type is the escort quest, where the player has to follow an NPC to a safe area. In this scenario, the NPC will normally move painfully slowly in order to draw attention to every available monster before the destination is reached - the object being to fight off the monsters while keeping the NPC alive. Other quests involve exploring a specific area or retrieving a specific item from some kind of container, which also serves as a way of directing the player to new or useful areas. Finally, I will mention one specific type of quest: the attunement quest. All attunement quests consist of chains of quests that need to be completed in order for an avatar to get access to the most difficult raid dungeons, called instances, in the game. The main objective is therefore not money, experience points or items, but simply access to game content. A typical attunement quest chain involves repeated runs to easier instances, lots of travelling and item gathering. These quests are most easily done with a cooperating group of players and preferably within a large player guild.

Given the fact that World of Warcraft has many thousands of quests to offer, the range of quests can seem quite limited. They have a prefabricated flavour to them, at least compared with the quests Tronstad describes in her study. The benefit of this limitation, however, is that the quests are easily recognisable by the player and normally quite easy to complete. The semiotic system surrounding the quest system points in the same direction; simplicity is key. This is also evident in the quest log feature that stores a description of every quest the player has accepted, up to a maximum of 25 quests.

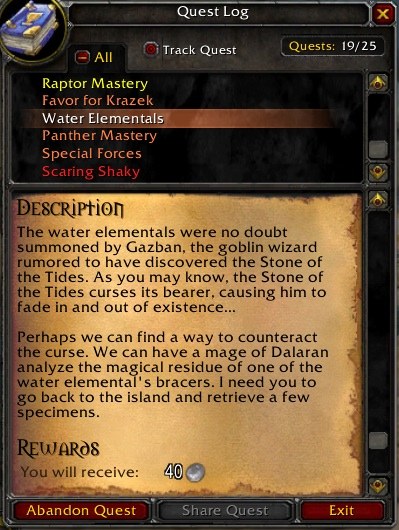

Figure 2: Quest log

Two screen shots from a quest log. To the left we see the quest Tiger Mastery that is part of a quest chain. This is the second quest in the chain and as we see the description hints toward at least one more quest. The quest log keeps track of the quest progression, in this case the number of tigers slain. In the other picture we see the log revealing how much money will be gained from the quest, but not how many experience points. The titles are colour-coded, indicating degree of difficulty. Grey is easiest, blood red most difficult.

Every quest is given a short description that places it in the overall fictional universe. This description serves at least two different functions. First, players that are willing to immerse themselves in the fictional universe of the game can read about what heroic deed they are about to undertake. Others, probably the majority of the players, will scan through the fiction to uncover the details necessary for completing the quest. Most quests have a summary at the end of the log, listing the objectives of the quest and as information is so easily available, there is little incentive for the player to dwell on the fiction.

The quest logs in World of Warcraft do not reveal all information necessary to complete the quest; the player for instance has to find out where the different monsters or items are located. This has opened up opportunities for information sites on the net that offer more detailed information and reveal hints about the completion of quests. Two of the most popular are thottbot.com and allakhazam.com, the latter having also, earlier, developed a large database of information regarding EverQuest. The most common information sought after seems to be the exact location of things, but strategy hints about how to defeat different monsters are also common. Players can contribute hints to these databases, and there are many descriptions of how to proceed with a quest and what fighting tactics the different classes might apply for a successful solution. There are also mini-programs or addons that facilitate quest solving. The addon Quest helper, for instance, is integrated directly into the game's map feature and displays locations and explains objectives of the different quests the avatar is currently on. It also creates a route describing what order the player should complete the different tasks, in order to solve the quests in the most time efficient way.

Figure 3: Quest helper

In this screen shot we see the map over the zone Hellfire Peninsula. The different signs on the map indicate activities the player has to undertake. The greyed out areas are places the avatar has not yet visited. As we see, quest objectives in these areas are also indicated on the map.

The rewards from the quests in World of Warcraft as a whole correspond with the level of difficulty or amount of work involved. Some of the best rewards are at the end of a nested quest, or so-called quest chains. The most arduous chains can consist of as many as 30-40 quests. The reward at the end is usually an item of rare quality. Quests that involve more than one player, the so-called group quests, are usually part of the longer quest chains and are therefore also subject to better rewards.

In general, quests in World of Warcraft do not require any riddle or puzzle solving, but are more about fighting tactics and time efficiency, and how to avoid dying in the process. In this respect, the quests in World of Warcraft differ from the puzzle quests Tronstad describes. In a passage quoted by Tosca (2003), Løvlie (2005) and Howard (2008) Tronstad states that: "To do a quest is to search for the meaning of it. Having reached this meaning, the quest is solved" (Tronstad, 2001: 3). In contrast to this, the point of doing quests in World of Warcraft is to reach the reward. The quests are not so much intellectual challenges as logistical ones.

Quests in Discworld

Quests in Discworld are quite different from the ones we find in World of Warcraft. First, they differ by being hidden in the environment. There are often only vague indications that the player has stumbled upon a quest, and it can be hard or even impossible to know if one has started on a quest. They can include simple elements such as uncovering items or delivering something to an NPC, which we can recognise from World of Warcraft. However, the quests are normally more elaborate and include activities and syntax that are unique to that particular quest. An additional issue is that very little information is revealed in Discworld about quests; for instance, how far a player is from completing a quest or at what stage in the quest the player is.

A related issue concerns the lack of information when a quest fails or a player does something inappropriate to the quest. There are no features in Discworld resembling the quest log in World of Warcraft and the player has to store and compile information about the quests manually. The quests in Discworld also lack the level restriction we found in World of Warcraft, which makes it difficult to decide whether an avatar will be able to access the areas involved in the quest. A circumstance that emphasises these difficulties is the fact that the players are not allowed to share direct information about quests on the MUD, a point that is even mentioned in the MUD's terms of agreement as one of six major topics. Besides agreeing that profanity is not allowed on public channels-that harassment of any kind is a reason for immediate banishment-the player must also accept that: "Giving out quest solutions, in whole or in part is not permitted either on the mud or through other media" (last accessed 28. August 2007).

In spite of this, new players sometimes ask in the general chat about how to find quests. These requests are often directed to the "help quest" file that comments:

Note that some players get a lot of satisfaction by completing the quests by themselves. If you discuss how to solve a quest on a public channel or by shouting it, you're probably ruining the experience for many others. If you're desperate you can ask another player in a "tell" for some kind of additional hint or insight. (last accessed 28. August 2007)

When a player enters Discworld with a new avatar, he or she at first will only have access to the so-called newbie area. This area has several signs that explain different aspects of the game. To get out of this area, the player will have to complete a specific quest, called Womble's Friend the object of which is to retrieve a brooch for this womble. This is the first lesson where the player learns that reading descriptions of rooms and items and using the "search" command can reveal information about possible quests. One of the signs in this area shows the following message:

Some of the quests in Discworld imply that specific incidents from the books have to be re-enacted within the MUD, and a player without thorough knowledge of the books will occasionally find it more difficult to solve them. The large majority does, however, not rely on the book series. The quests in World of Warcraft are also related to their fictional universe, but the difference is that the main source of the lore concerning the World of Warcraft is the game itself.

The number of quests in Discworld is far lower than in World of Warcraft. During my research I gathered information about 156 quests and completed most of them.[6] The exact number of quests was probably not more that 200 in total at the time of my study. In the last years there have been several quests added, along with the addition of new game areas, but the total number of quest is still less than 220. Of the 156 quests on which I collected data, almost a third gave some type of reward, of which nine were money and the other either some kind of item or access to a specific syntax or command in the game. Most noticeable are the quests that give the player access to the emote and remote commands. These commands are crucial for role-players as they are basic tools for staging this kind of play, but they are also used by the broader player community to mimic emotions, mood and extra-linguistic information. Other quests give access to specific game commands, for instance the leatherworking feature. One specific quest gave access to an intra-MUD chat channel, that is, a channel that is accessible for players on two other MUDs apart from Discworld. Only a handful of the quests gave useful rewards like weapons; the rest were of a more humorous character and included a yo-yo, some extremely hard soap flakes, a handful of peanuts and a pogo stick.

In general, the quests in Discworld are not as easy to categorise as in World of Warcraft, as they often involve unique elements. I will therefore spend some time describing how a quest might be structured. The quest Bethan's Buddy will serve as an example, and I will illustrate this by narrating my own process of solving it. This quest is of average complexity of the quests in Discworld, but there are quests that both involve a more complicated syntax, more items and a larger number of sub-goals. This particular quest mainly involves acquiring items.

On entering Cohen's house on Vagabond Street in Ankh-Morpork, you will find his wife Bethan. If you stay in the room a few seconds the following chat will appear:

>Bethan says: Can you please help me? I'll never find everything on my own.

> Bethan asks: What am I going to do? What am I going to do

An NPC that addresses the player directly is a good indication that some sort of interaction will be possible. In this case, if you answer the NPC's request by entering the command "say help," the following will happen:

> You say: help

> Bethan asks: You'll help me? That's wonderful! Thank you so much. I just need you to find a few things for me. You wouldn't mind, would you?

> You say: no

> Bethan says: Great! My problem is that my husband is very particular about his few luxuries in life, and gets very upset if he can't have them. I just haven't got time to find them all, so, if it were at all possible, would you be able to find me some soft lavatory paper and some hot water? Oh, and also do something about his dentures if you could - they have been hurting him like crazy, the poor old guy.

In this case the magic word "help" uncovers the objectives of the quest. Saying help in the vicinity of NPCs might, in many cases, prompt them to reveal hints about quests; in other cases, repeating words they say can have the same function. When the necessary information is obtained, the implementation of the quest can start. In this case we have to find three different things: toilet paper, a set of dentures and some hot water. The easy part is to get hold of some toilet paper, which I remember seeing in a house nearby. After some minutes backtracking my traversal, I find the paper. Locating a dentist is a bit harder, but here an inquiry in the general chat reveals that there is one located in another part of the city. Inside the building where the dentist is located there is a "neat secretary" who prevents me from entering his office. When I try the command "make appointment" or "say appointment", the secretary answers: "I'm sorry, the dentist is fully booked for the next three years. Cohen is quite a handful... ". At least with the mention of Cohen's name I now know that this is the right place. After I have been getting nowhere trying to forcefully enter the dentist's room and trying different commands like "get in queue" and "enter office", the dentist suddenly arrives from his office. Now, the task is to get the NPC to either give me Cohen's dentures or at least reveal how I can get hold of them. Saying words like "Cohen" or "dentures" does not have any effect on this NPC. Having tried many possibilities, including investigating every object in the room, I consult a quest list that reveals that the sentence: "Cohen needs his dentures" will do the trick. The solution was most likely prompted by the mention of the words "Cohen" and "dentures" in the same sentence. By saying this I get the following response:

> The dentist asks: Cohen? His dentures playing up again, huh?

> The dentist says: Well, give him this voucher, then... I owe him a favour.

The dentist gives a dentistry voucher to you.

The riddle first seemed to concern how to get hold of a set of dentures and then the task seemed to be about how to make an appointment with the dentist. Eventually, it turned out to concern what syntax to use to get hold of a voucher. Now the third part of the quest can start: to get hold of some hot water. At this point I am not even trying to find the way on my own, but by consulting a quest list, it turns out that the correct place to search is far away from this city, on a table inside a gingerbread house in a place called Skund. After a relatively long journey, I get hold of the water. All items gathered, I now have to give them to Bethan, using the "give" command, and the quest is completed.

The three different tasks in this quest turned out to involve items that were located at an increasing distance from the quest giver. The first and last task simply involved obtaining an item, but locating the last item was the problem. The second task involved interaction with different NPCs and was structured more like a riddle quest. Tronstad (2005) writes that part of the challenge presented by a riddle is to establish what rules the riddle follows. A good riddle, according to Tronstad, contains hints necessary for understanding the solution: "One of the characteristis of a good riddle or puzzle is that after we've solved it - or even been told its solution - the solution will appear obvious to us. If the solution still appears far-fetched it is simply not a very good puzzle" (Tronstad 2005: 6). A similar point is mentioned by Nick Montfort (2003) who describes a false riddle, the neckriddle, where only the riddler knows the answer. In Discworld, some of the quests have elements that would make them almost qualify as "neckriddles" since they involve finding objects or typing a combination of words or a syntax that the player is very unlikely to find unguided. The second part of the Bethan's buddy quest would probably be solvable for most players as long as they try out enough combinations of words related to the quest. The last part, however, would for most players be impossible to solve, since it is highly unlikely that they would find this house in a random search for a cup of hot water. A player solving a quest like this without any guidance would need to have a very good overview of the MUD's geography and a generous amount of time on his or her hands. As such, the quest is not a self-sustained entity containing the necessary hints for a solution. It is arguably not a very good quest.

Volatile Aesthetics

There are several structural issues that make it hard to complete quests in Discworld. These can be divided into two broad categories. First there are issues related to the development history of the MUD, and secondly, issues related to the quest ethos enforced by the developers. By ethos I mean an ethical standard governing the aesthetic approach the developers advocate as the correct way of solving quests. I will first address what I regard as the source of most of the difficulties regarding quests: design issues related to the development history of the MUD.

The Discworld MUD is now in its 17th year, and many changes have occurred during this time: much of the player base has been replaced several times, as have most of the developers; the programmers, just a handful at the beginning of the MUD's history, now amount to about 180; and the operating systems running the MUD have been upgraded or changed several times. Finally, there has not been any centrally coordinated coding praxis or clear guidelines of what syntax or coding to use for the MUD, particularly in the early days. The result of all this is that quests are, as much of the MUD, a patchwork of different programming practices, different semiotic systems, different gameplay traditions and different game mechanics. As an example of this, I will mention one specific quest, where the objective is simply to enter a tent in a desert to complete the quest. This quest challenges the whole concept of a quest, as no considered effort is needed to complete it. The reason why this can still be considered a quest is the fact that it gives the player both quest points and experience points.[7] This quest more than anything illustrates the lack of coordinated design criteria on this MUD. The differences regarding syntax and programming practice are perhaps more noticeable in quests than in other parts of the game, since commands and syntax usually work universally, whereas it is possible to write specific commands or syntax for each quest. The individual quest programmer, to a certain degree, is able to follow his/her own idiosyncrasies or programming style. At the receiving end, this severely limits how the experience from one quest will benefit a player trying to solve another.

A final contextual element tied to the development history of the MUD concerns the sheer size of it. Discworld has grown from a single street with some surrounding houses, to a large world consisting of tens of thousands of single rooms. A programmer creating a quest in the earlier phase of the MUD would have had no idea that the MUD would eventually become ten times bigger. This is especially relevant in relation to quests that involve many different items, sometimes scattered all over the MUD. Later expansions of the MUD make these kinds of quests far more complicated than initially planned just because of the exponential growth of the possible combination of items.

These are some of the historical related design issues that make quest-solving in Discworld difficult. These difficulties were also apparent in my interview material, as most informants described the quests as being too difficult. A female player, aged 22, who had became a play tester shortly before the interview, had difficulties completing quests. She describes her playing style as an explorer and helper and knew the MUD fairly well having played about 80 days over the last two years, but her explorative approach to the MUD was not always enough to handle the quests she encountered. When I asked her what she though about the quests, she responded:

Informant: Some of them are just… are very difficult. Too difficult. I have loads of half finished quests because I can't work out what to do.Researcher: But you don't use quest lists, no?

Informant: No, normally I hear rumours, like: oh, there is a quest list, lets see what we can do there. That's normally what we'll do, or someone will tell you: you have to do so and so, just hear bits about them. Mostly I just find them out for myself.

Researcher: Yeah, but if you get really stuck, do you then ask someone to help you?

Informant: Yes, a little, but people won't tell though. Nobody will actually tell. They will just: have a look at so and so and... oh yes.

This player describes how the ethics regarding quest hints are upheld by at least parts of the player population. Regardless of having lots of friends in the game, she seldom finds people who will actually tell her directly how to solve quests. The difficulty of solving quests was also mentioned by some of the developers. A female senior creator aged 26 put it like this:

I: Well, the quests I am familiar with I usually solve with my alts. Mostly for fun, when I run past and: aha right, here we can do this but... yes, sometimes I look for, look actively for quests, but I usually think it is quite hard actually. In spite of the fact that I have been on this MUD for six years and have written a number of quests myself, I sometimes find it tremendously hard to figure out what to do with what, because it's so... I think some creators are very anxious about giving out hints, so it ends up with no hints at all. You have this item and then: oh well (laughs) then you just stand there and see if you can do anything with it. And then you go around testing a few things and then finally you get bored with it.R: It is too time consuming?

I: Yes, too hard to figure out. I think quests should include hints. If you look around and read everything, you should be able to figure out what you are supposed to do. The next step.

When even the developers of the MUD conceive of the quests as being too hard, it might be pertinent to ask why they create them this way. One explanation is related to how the work on the MUD is organised. One of the administrators I interviewed mentioned that programming was hard work and that motivating the programmers could be difficult. At the time of the interview, he was involved in the development of a new continent, the Counterweight Continent, which was put into the game in 2003. He described the process of building the major city, Agathea, like this:

Building Agathea was lonely and tiresome, because was this fun like creating an NPC or a quest? Actually you had to build a hundred street rooms that looked identical around it, and can not be identical. And in each of those it got to be five or six or ten room chats. Five or six or ten items you can look at, each with a little description. So it can take ... to write something like short street which we all know is 25 rooms or something. That could be a fortnights work to write that, or a week's work to write that and actually you have added no more that the street. There is no quest, no interesting things, it is just a road. And actually it takes a long time and that's how it works. Trying to get people to build and build and build. But you have to do it and we managed.

Having produced large amounts of description of ordinary places, items and rooms, the programmers were given the opportunity to create, as he put it, a "funky NPC or a quest" as some sort of reward. It is interesting to note that there is clear evidence of a content hierarchy among the developers of Discworld, with quests and unique NPCs ranking high and generic items, like rooms and items, ranking very low. The quests are definitely regarded as the fine art of the game, as elements where the programmers can show their skills as programmers, game constructors and writers. While quests in Discworld are products of creativity, in World of Warcraft they are largely produced from a pre-defined set of design elements.

The uniqueness of quests in Discworld, as we have seen, will not be met with equal enthusiasm by all the players. One of the players who did enjoy quests however, was a 26 year old male player. At the time of the interview, he had accumulated a total of 175 playing days over the last four years. For him, quests represent a break in the routine; something out of the ordinary:

I think quests are great fun. Because it is such unique stuff. You can't do them more than once, but what is great about them is that they do not go anywhere. They do not disappear. It is never over. If you do something wrong some place, you can almost always start over and then you can solve it. But they are of a specific … there is some kind of depth to them. Because it is something different from the ordinary things you do. They are a little different. Often there is some sort of special commands and stuff happens that you do not see anywhere else. In the beginning it was mainly because you got experience points, but after a while you think that … it is fun as well. It is fun to have a high, to show that you have done a lot of quests as well.

This player obviously recognises and appreciates the unique quality of the quests. It should be mentioned that this specific player had made maps covering the entire MUD and therefore had a much more detailed knowledge of its content than most players, probably most of the developers as well. In the quote above, the player mentions that it is fun to show others that he has completed many quests. In the main Discworld city there is a specific room, the Great Hall of Heroes, where it is possible to see what quests all of the players have completed. Each player is also given a title reflecting the number of quests he or she has completed. Players that have solved many quests receive titles like "an adventurer who is famous" or "an adventurer who is Disc renowned". The really dedicated ones that have completed most of the quests can acquire the title: "an adventurer who is so renowned that no introduction is needed." This simple feature can be seen as mirroring the content hierarchy of the developers. Killing a hundred thousand NPCs yields a great number of experience points but little glory, while solving a mere one hundred quests will earn the player celebrity, or at least the illusion of it.

Ethos Surrounding Quests

So far I have described the type of quests we find in the two games, with emphasis on their difference in difficulty. In Discworld, quests are supposed to present the player with a real challenge. They are not meant to be easy, and the use and possible "exploits" of quests are surrounded by both formal and informal rules. It might be difficult to understand the reason for this design agenda; an issue I will explore more thoroughly in the following. Formally, the rules concerning quests clearly state that:

Giving out quest solutions in whole or part is cheating. Information related to quests must not be discussed over chat channels. If a player is stuck while doing a quest assisting with a hint is acceptable but giving specifics on how to solve the quest will be punished severely. For further information see "help quests".[8]

Compare this with the help description concerning quests in World of Warcraft:

Completing quests is the easiest way to level up, get money, receive trade skill recipes/components, earn equipment, and more. It is best to spend the majority of your time focusing on quests if you want to level up and become more powerful. Be sure to grab every quest you can find, and feel free to jump on to your next quest as soon as you've finished one. You can play however you want, but remember, it's all about having fun![9]

In another section of the help site, Blizzard further state that:

Other players can tell you which quests are good for experience or which might have a quest reward that will benefit your character. Feel free to talk to guild members, party members, or players in the general channels for advice.

If you are having problems completing a quest or finding where to get a quest, ask for help in the general chat channel. You can also post about quests in the Quest Forum. Usually the best place to ask is your guild, especially if there are more experienced players who have completed the quests several times.[10]

It is quite obvious that Blizzard regards quests as a feature that should be easy for the users to accomplish. This could be interpreted as a result of the economic structure of the game. As far as possible, being a commercial company, Blizzard will avoid users that get frustrated with the game and leave because of too high a level of difficulty. In contrast, the developers of Discworld does not need to take any economic considerations into account when deciding on design strategies, as the MUD is exclusively run by volunteers. For several years, to ensure that quests were solved in "the right spirit", the developers of Discworld were hunting down sites on the net that contained quest solutions and made the server providers ban those containing hints and walkthroughs. They even made quest lists themselves with false quest solutions in the hope that this would diminish the value of the correct ones. Finally, in 2002, the developers decided that quests no longer should be rewarded with experience points, as this was regarded as the only way the players would solve them without agendas other than the enjoyment of the quests themselves. When the developers' quest ethos was not agreed on by the players, when the socially enforced rules did not work as intended, they simply changed the game mechanics instead. Several years later, in 2006, they reversed this decision by reintroducing experience points for some quests and also by making available a database consisting of hints for quest solutions. This database is located on their web site and has the following introduction:

Welcome to Discworld MUD's quest database! Here you can find information on where to find and how to solve all the quests on the MUD, choosing yourself if you want to see the whole solution or just to get hints about how to get started.

Disclaimer: A lot of the fun you get out of a quest is the satisfaction of actually having figured it out. Some of that might be lost by reading the solutions found here.[11]

As we can see, the initial reasoning about the proper way of solving quests is still present. The ambition in the earlier phase of Discworld to sanction hints and walkthroughs distributed on the net can easily be regarded as a paradox given the fact that a multi-user medium embedded in an even larger networked media society present the users with almost unlimited access to information. From the players' position, an instrumental approach toward quests can also be highly desirable, since levelling as fast as possible gives access to more game content, represented by more powerful weapons, spells and geographical areas. The quest ethos formulated by the developers of Discworld is in clear conflict with the realities surrounding the medium as well as the enhancement structure of the game. One of the creators that resented the recent changes on the MUD offered this as the reason for his resentment:

I think it devalues one of the more unique elements of DWmud and is in a way almost giving in to the unpleasant individuals who weren't prepared to sign up to the implied social contract that playing the game imposes.[12]

There is a strong moral tenor underlying this statement, but the developers believe they have reasons for trying to uphold this "implied social contract". One explanation offered by this developer is that the players could develop a strong avatar in just a few days by using quest lists, which has led to several incidents where players developed "harassment characters" just to make other players' lives miserable, without running the risk of having their main character being expelled from the MUD.

This reveals an important difference regarding design of the quests in Discworld and World of Warcraft. In Discworld, many of the quests can be completed very quickly if you know exactly where to go and what action to perform, since quests seldom involve repetitive chores. Thus, you do not need a quest list to rapidly advance a new avatar; you just need to have done the quests earlier. In World of Warcraft, even if you know the exact procedure of the quest, the execution of it will take a specific amount of time as you still need to kill these 15 whelps or obtain those 10 pelts. The repetitive pattern of the quests in World of Warcraft simply reduces the benefit of cheating. In Discworld the difference between solving a quest unaided and with a walkthrough can be to do it in minutes instead of hours or, sometimes, even days. Instead of designing quests that required more than a few minutes to solve, they tried to force the players to spend as much time as they thought was appropriate. It is hard not to regard this as a naïve approach toward the player community.

In addition to appealing to a "proper" way of approaching quests, the developers also discussed different design solutions. For a designer who both wants quests to be unique and to avoid the use of quest lists, repetitive chores like the ones we find in World of Warcraft is not a good enough option. One developer wrote the post "Unlisting the listable" explaining some of the elements a quest should include to render quest lists useless. The central argument of the post was to "[i]dentify areas where there is room for randomness." He elaborates as follows:

It's remarkably difficult to design a quest that cannot be listed. It requires an exponential amount of effort to design, and a huge amount of extra effort to develop. However, this is pretty much the only way to ensure a fairness in quest rewards - the reward must equal the expended effort.[13]

This developer describes the high level of complexity involved in designing a quest that has random elements, due to the fact that the combinatorial possibilities grow exponential with every new element added. The normal quest design in Discworld is linear or progressive, which is the reason it is possible to write walkthroughs in the first place. The difficulty of including randomness into the design is another reason why the developers were trying to lean on the players' morals rather than on design solutions.

We might still ask why the developers regard it as imperative for the player to approach the quest in "the right spirit". As we saw from the help file "[a] lot of the fun you get out of a quest is the satisfaction of actually having figured it out." The right way of approaching a quest is in a lonely struggle with the few scraps of information revealed by the MUD. Tronstad's account of how the player should approach the quest might shed some light on this issue:

Only the player who believes that there is something "behind" the surface, some secret to be disclosed, may enter the seductive discourse of questing. At the same time, players who are not willing to indulge in the quest as a seductive practice but who encounter the puzzles forcefully as challenges to be overcome—who are playing for the sole purpose of re-configuring the quest product, to obtain a final meaning—may find it difficult to enjoy questing (2004: 161).

The developers of Discworld would probably agree with this as it resonates with the way they conceive of, and construct, quests. The elusive nature of the quests in Discworld compared with the easily accessible ones in World of Warcraft is somewhat reminiscent of the difference between fine art and popular culture. Fine art represents an intellectual journey that is not supposed to be entirely easy or immediately accessible, and the aspect of uniqueness and originality of the quests in Discworld points more toward art than popular culture, while the easy recognisable genre traits of the quests in World of Warcraft are more akin to popular fictional genres like fantasy and crime fiction. As mentioned earlier, some of the quests in Discworld might be considered poorly designed rather than artful, but my intention has been to show how the developers regard their quests, and further, how this influence their view on how a player should approach them.

An analysis based on the quests alone would suggest that Discworld is a more sophisticated and difficult game than World of Warcraft. This is not necessarily the case. In World of Warcraft, the most complicated enterprise of the game is to defeat the toughest monsters, the bosses, in the raiding instances. These bosses will in many ways represent the uniqueness and variety we find in the quests in Discworld. In World of Warcraft, quests represent the average, run-of-the-mill action, and a necessary recourse to advance a character. In Discworld, on the other hand, there is no maximum level an avatar can reach, and no high-end gaming to strive for. The quest is in many ways the high end of this MUD and therefore, like the raiding dungeons in World of Warcraft, at the top of the content hierarchy.

Summary

I will sum up by highlighting three findings from my material. First, both games display a wide range of quest types. When compared, it appears that these quests are very different from one another although some types overlap. The quests in Discworld have many design elements that make them hard to solve. They are hidden in the environment and employ syntax or actions that often are unique to each quest. In World of Warcraft, the quests are easy to find and easy to solve. The quests in World of Warcraft are therefore, on the whole, possible to map structurally as advocated by Aarseth and Walker. The quests in Discworld, on the other hand, cannot be categorised by structural features as easily, due to the variety and complexity of their design. As such, the possibility for academic categorisation and analysis mirrors the accessibility of the quests. In World of Warcraft quests are clearly themed and easily solved, whereas in Discworld they are both harder to solve and to categorise.

Secondly, we have seen that the quests fill different roles and have different positions within the content hierarchy of the games, both with regard to difficulty level and artistic expression. In World of Warcraft, quests are mainly an easy accessible and temporary occupation while advancing toward the maximum level. The raiding is the most complex and challenging game content here, both with regard to social organisation and tactics. The boss encounters represent uniqueness more akin to the quests in Discworld. Designing quests in Discworld is regarded as a sort of aesthetic or creative reward after designing generic items and rooms. Their uniqueness is matched by the difficulty the players have solving them. While quests in World of Warcraft are somewhere in the middle of the content hierarchy of the game, in Discworld they are at the top.

Thirdly, I will bring attention to the difference of ethos in relation to quests. Many of the quests in Discworld are designed so that help from a walkthrough can save the player a tremendous amount of time. The arms race between the players and the developers regarding quest lists illustrates how the developer's intentions with the design were not fully embraced by the player community. The developers tried for some time to prevent players sharing information about quests by relying on social mechanisms but ended up using game mechanics to regulate unwanted behaviour. In World of Warcraft, in contrast, the developers furnish an instrumental approach toward questing in several ways. Through the online forums and help pages the developers support players that want to help each other solving quests. Features like the quest log and addons like Quest helper further facilitate questing. The quest design in World of Warcraft is a solution where, for economical or aesthetic reasons, the player's utilitarian approach is accommodated through the developer's design. In Discworld, the aesthetic ambitions regarding quests is arguably loftier than in World of Warcraft but the fact that the players are subverting the content by cheating is a strong indication that the aesthetic ambitions of the developers is not successfully embodied in design. A more player-oriented view of the quest feature would probably have been beneficial for their design solutions.

References

Aarseth, E. (2003) "Playing Research: Methodological approaches to game analysis." DAC 2003. Melbourne.

Aarseth, E. (2005) "From Hunt the Wumpus to EverQuest: Introduction to Quest Theory." ICEC 2005: 4th International Conference. Sanda, Japan.

Howard, J. (2008) Quests: Design, Theory, and History in Games and Narratives, Wellesley, Massachusetts, A. K. Peters.

Juul, J. (2005) Half-real: video games between real rules and fictional worlds, Cambridge, Mass., MIT Press.

Løvlie, A. S. (2005) "End of story? Quest, narrative and enactment in computer." games. DiGRA: Changing views - Worlds in Play. Vancouver.

Montfort, N. (2003) Twisty Little Passages: An Approach to Interactive Fiction, Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England, The MIT Press.

Tosca, S. (2003) "The Quest Problem in Computer Games." Technologies for Interactive Digital Storytelling and Entertainment (TIDSE) conference. Darmstadt, Fraunhofer IRB Verlag.

Tronstad, R. (2001) "Semiotic and nonsemiotic MUD performance." COSIGN. Amsterdam.

Tronstad, R. (2004) Interpretation, Performance, Play, & Seduction: Textual Adventures in Tubmud, [Oslo], Faculty of Arts Department of Media and Communication University of Oslo : Unipub.

Tronstad, R. (2005) "Figuring the Riddles of Adventure Games." Aesthetics of play. Bergen.

Rettberg, J. W. (2007) "A Network of Quests in World of Warcraft." In Wardrip-Fruin, P. H. A. N. (Ed.) Second Person: Role-Playing and Story in Games and Playable Media. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England, The MIT Press.

Rettberg, J. W. 2008. "Quests in World of Warcraft: Deferral and Repetition." Pp. 167-184 in Digital Culture, Play, and Identity, edited by Jill Walker Corneliussen Hilde G & Rettberg. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Ludography

Discworld MUD (1991)

EverQuest, Sony Online Entertainment (1999)

World of Warcraft, Blizzard (2004)