The Leisure of Serious Games: A Dialogue

by Geoffrey M. Rockwell, Kevin KeeAbstract

This dialogue was performed by Dr. Geoffrey Rockwell and Dr. Kevin Kee1 as a plenary presentation to the 2009 Interacting with Immersive Worlds Conference at Brock University in St. Catharines, Canada. Kevin introduced Geoffrey as a keynote speaker prepared to present on serious games. Instead of following convention, Geoffrey invited Kevin to engage in a dialogue testing the claim that "games can be educational". Animated by a spirit of Socratic play, they examined serious gaming in the light of the insights of ancient philosophers including Socrates, Plato and Aesop, twentieth-century theorists such as Ludwig Wittgenstein, Bernard Suits, Johan Huizinga, and Roger Callois, and contemporaries such as Espen Aarseth, Bernard Suits and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Their dialogue touched on topics ranging from definitions of play and games, to existing examples of “serious games”, to divisions between games and simulations, and the historical trajectories of comparable media. Their goal was to provide an introduction to these topics, and provoke discussion among their listeners during the conference that followed. In the end, they agreed that the lines of separation between "games" and "learning" may not be as clear as sometimes assumed, and that in game design we may find the seeds of serious play.Keywords: serious games, play, education, Socratic dialogues, theory.

“Anyone who tries to make a distinction between education and entertainment doesn't know the first thing about either.”

- Marshal McLuhan

GEOFFREY ROCKWELL: Dear Kevin, I'm sorry to have to disappoint you. You invited me here today to talk to you about serious games, but I don't really know the first thing about them, because I don't believe that games can be serious.

But don't be dismayed, I am possessed by a playful spirit, let us call it a Socratic "anime ludens", that insists that someone at the end of the day, before the wine, speak for games themselves, which all the rest of you take so seriously.

“Making games educational is like dumping Velveeta on broccoli. Liberal deployment of the word blaster can't hide the fact that you're choking down something that's supposed to be good for you”.2

So Kevin, help me out in the spirit of Socratic play. Lets pretend you are the advocate of serious games so I can question you.

You think a great deal about the improvement of youth?3

KEVIN KEE: Yes, I do.

GEOFFREY: And you think games, especially computer games, can improve youth?

KEVIN: Absolutely, and I can show you some examples.

GEOFFREY: Please do.

Examples of Serious Games

Figure 1: September 12 Introduction Screenshot

http://www.newsgaming.com/games/index12.htm

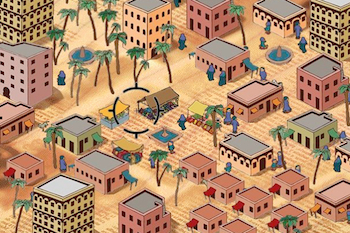

KEVIN: The first example I’d point to is September 12, created by newsgaming.com. This is the company lead by Gonzalo Frasca, one of the strongest voices for understanding computer games as games, and not as movies or books or something else.4 In short, he’s a “ludologist”, and if we really wanted to mix it up, we could debate “ludology” and “narratology”.5

GEOFFREY: Let's leave that for Epen Aarseth and Janet Murray [Note: these speakers also gave plenary presentations at the conference], shall we? I have enough questions for one plenary.

KEVIN: Fair enough. The point I wanted to make was that “ludologists” basically argue that games are an altogether new form of entertainment, and that anyone who wants to truly understand them must focus on the mechanics of game play. Frasca’s one of those. And the focus on play comes through in September 12. Frasca created September 12 following the September 11 attacks. In essence, September 12 argues that the U.S. government’s attempts to stop terrorists, often manifested in the firing of missiles into villages from 30,000 feet, only serve to create more terrorists. The solution is the problem.

GEOFFREY: Are you really going to build your case on a 5-minute experience with Flash?

KEVIN: It's a simple game, I'll grant you, but it's still a game. And let me say as an aside that I think a lot of people who don’t like serious games don’t like the fact that they’re simple and played for a short period of time. If it’s not World of Warcraft6 and going to take three hours every day to play, for the next 5-6 years of my life, then it’s not worthy of the name “game”.

GEOFFREY: I think you just lost about a third of our audience, but go ahead. It's fun watching you dig your own grave.

KEVIN: OK, why stop now? I have a sneaking suspicion that this isn't going to end well for me anyway. What I want to argue is that despite its simplicity and brief game play, in fact, because of its simplicity and brief game play, September 12 provides a profoundly educational experience.

The game board is obvious: it’s a village somewhere in the Middle East. The sprites are easily identifiable: men, women, children, terrorists. And then there’s you, the player, high above, firing missiles. And you shoot - you don’t have to, but you want to - I've yet to see anybody "play" this game by not shooting.

GEOFFREY: But September 12 is subtitled "A Toy World" and the first line of the Instructions say "This is not a game."

KEVIN: Don't let that fool you.

GEOFFREY: Why not? ... OK, for the sake of argument, I'll agree this is a game. But a serious game? Where is the sustained learning? Where is the improvement of youth?

KEVIN: Right - so let's come back to game play. When you shoot, you’re challenged by a small but very important change to conventional game play mechanics. You think that you can just fire at will, with pinpoint accuracy, in the manner of an arcade shooter. But there’s a delay between the moment that you fire the missile, and the time that it lands, and in that delay people move, and innocent civilians get killed.

Where’s the education? You see clearly that in real life, there’s a delay between the moment that the decision is made to fire a missile at terrorists -- in the cockpit, in the control center, in the White House -- and the time that the missile lands. And during that delay, the situation on the ground changes, and innocent people get hurt. The delay can be literal - time - or metaphorical - imperfect information.

GEOFFREY: Yes, but the question that I asked is: "where is the sustained learning"? You've made a case that there's a brief revelation, a moment of learning, a fable with a moral. I can see that. But this is hardly something that a politician is going to be able to build a campaign around.

KEVIN: No, but that's not the purpose. This is a conversation starter: some people think that the way to crush terrorism is to fire missiles from 30,000 feet. Frasca makes the point, through the way the game is played, that that kind of anti-terrorism strategy only creates more terrorism. Then he wants others to go from there. If you want to talk about sustained learning in a game, I have another example to refer you to.

GEOFFREY: I thought you were going to say that.

Figure 2: The History Game Canada

http://www.historycanadagame.com

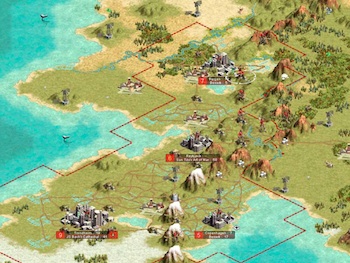

KEVIN: This is a game called “History Canada”, produced by Toronto’s bitcasters7 (As someone who researches the ways that history can be expressed in games, I’ve got a soft spot for this one.) It’s a modification of Civilization III.

Figure 3: Civilization III Screenshot

Bitcasters got the source code from Firaxis and so retained all of the game mechanics, but changed the maps, the characters, etc. Instead of taking over the world from the Stone Age to the Space Age, you try to recolonize Canada in the 1700s - imagine Civ III with a map of the Eastern seaboard of Canada and the United States, and French, English, and aboriginal people sprites.

GEOFFREY: This sounds like a great way to ruin one of the best games of all time.

KEVIN: Not at all. You can choose to play as one of the three so-called "founding peoples" of Canada. Your goal is to achieve dominance on the new continent. You take your turn, moving your sprites to different parts of the map, allocating resources, building your civilization. You watch your computerized opponent take its turn, as it moves the other founding peoples to different parts of the map, allocates their resources, and builds their civilizations, in an attempt to beat you. It’s a classic resource management simulation/game.

GEOFFREY: It's a classic resource management simulation/game with a limited number of options. You can play as anyone, as long as its one of the three founding peoples. You can take over the entire planet, as long as all you care about is Canada and the northern U.S..

KEVIN: It's a constrained game, agreed. But bringing Canadian history learning into Civilization III requires that you impose some limits. In so doing, you focus the user's attention. Playing this game, you come to realize that not all civilizations are created equal. Choosing to play as aboriginal peoples has some advantages: they are highly mobile, for instance. But it also carries disadvantages: the weapons technology that they can access is not as effective as those of the Europeans. Where’s the education? Through game-play, you realize the inherent advantages and disadvantages that the three groups - English, French and aboriginal - brought to their contact with one another.

GEOFFREY: These look to be two completely separate experiences.

KEVIN: Exactly. If “September 12” represents one end of the serious gaming spectrum, “HistoriCanada” represents the other. “September 12” is a Flash game played online; “HistoriCanada” requires that you have the original game upon which you run the mod - you’ve got to make a commitment. “September 12” can be used anywhere you’ve got an internet connection, a Browser and Flash. “HistoriCanada” is probably best used in a computer lab at school. Where “September 12” is a 10-minute experience, “HistoriCanada” will take you a few hours. Where “September 12” is pitched at a target audience that is conversant with contemporary geo-political debates, “HistoriCanada” is meant to be used by teenagers in a high school classroom who are studying eighteenth-century North American history. Last summer, 15 teenagers played this for a week in a computer lab at Brock when they could have been doing a lot of other things, so I can testify to its effectiveness from the perspective both of “learning” and “fun”.

Defining Serious Games

GEOFFREY: The problem, Kevin, is that a couple of examples, even hundreds of examples, doesn't prove your point that games can be educational. There is no doubt that learning can happen accidentally while playing a game, or that some games may provoke conversations that are educational, but what is educational about the game qua game? I would like to propose that serious games can't, by definition, be both.KEVIN: By what definition can't games be serious?

GEOFFREY: Well ... for example, look at how play has been defined by Huizinga in Homo Ludens:

“Summing up the formal characteristics of play we might call it a free activity standing quite consciously outside ‘ordinary’ life as being ‘not serious,’ but at the same time absorbing the player intensely and utterly. It is an activity connected with no material interest, and no profit can be gained from it. It proceeds within its own proper boundaries of time and space according to fixed rules …” 8KEVIN: But Huizinga is defining "play" not "game". Play may not be serious, but games can have serious ends.

GEOFFREY: Well if you want a definition of "game" then we could turn to Roger Caillois in Man, Play and Games. Caillois defines the playing of games through six characteristics:

- Free - in his words “not obligatory; if it were, it would at once lose its attractive and joyous quality as diversion.”

- Separate - or “circumscribed within limits of space and time”

- Uncertain - in the sense that outcome is not predetermined

- Unproductive - as opposed to disconnected from material interest - his point is that nothing is produced in play, though money can change hands

- Governed by rules - or “under conventions that suspend ordinary laws, …” and finally,

- Make-believe - or “accompanied by a special awareness of a second reality or a free unreality, as against real life” 9

KEVIN: I think you choose selectively from Caillois. After all, he introduces his defining characteristics because he thinks Huizinga's definition is too limiting. He wants to make room for betting games and the breadth of forms of play. In addition to his characteristics of play he also provides "categories for a systematic classification of games" which are Competition (Agon), Chance (Alea), Simulation (Mimicry), and Vertigo (Ilinx). Of these, competitive games and simulation would both seem candidate classes for serious games, though serious in different ways.

GEOFFREY: I'm glad you mentioned competition and simulation, and I want to return to them, but that doesn't get you out of the paradox of serious games. My sense is that Caillois would classify serious games as a form of "corruption of games." I quote:

“the tendency to interfere with the isolated, sheltered, and neutralized kind of play spreads to daily life and tends to subordinate it to its own needs, as much as possible. What used to be a pleasure becomes an obsession. What was an escape becomes an obligation, and what was a pastime is now a passion, compulsion, and source of anxiety”Is he not warning us to leave games alone and not try to deform them into something educational?

KEVIN: Be serious Geoff. Are you really comfortable writing off serious games because of a fifty-year-old definition of the play of games?

GEOFFREY: Why should I be serious about games? You would accuse me then of being inconsistent? No ... I continue to wear this mask a little longer.

KEVIN: Then let me propose an anti-definition and that is the discussion in Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations in sections 66 and 67:

“66. Consider for example the proceedings that we call “games”. I mean board-games, card-games, ball-games, Olympic games, and so on. What is common to them all? -Don‘t say: "There must be something common, or they would not be called ’games'" -but look and see whether there is anything common to all. -For if you look at them you will not see something that is common to all, but similarities, relationships, and a whole series of them at that. ... 67. I can think of no better expression to characterize these similarities than ‘family resemblances’; ...”GEOFFREY: You know what Bernard Suits says about Wittgenstein in The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia?

KEVIN: I knew you were going to bring him up. Go ahead and remind our audience.

GEOFFREY: He calls Wittgenstein's admonition to "look and see whether there is anything common" "unexceptionable advice" that "unfortunately, Wittgenstein himself didn't follow." 11

KEVIN: You can quote Bernard to suit yourself, but his alternative "longer and more penetrating look at games" ends up a series of dialogues with Aesop's Grasshopper as the main character. Hardly a serious response to Wittgenstein.

GEOFFREY: And what is wrong with dialogue as a way of looking at games, especially if as Suits says, you want to propose games as the best example we have of intrinsically valuable activity - things you do for themselves in a utopia as opposed to instrumental activities or work. Aesop's Grasshopper is the model of improvidence - the Grasshopper plays away his time choosing death over work.

“Why not come and chat with me,” said the Grasshopper, “instead of toiling and moiling in that way?” 12KEVIN: Are you really going to set up Aesop's Grasshopper as an answer to Wittgenstein? Remember what happened to the Grasshopper - he died of hunger regretting his improvidence and moralizing that it is best to prepare.

GEOFFREY: The Grasshopper is just the first in a long line of thinkers who refused to compromise and died for their leisurely principles. Socrates is reported in the Phaedo to have been setting Aesop's fables to song right before his death - if you will he was singing and playing around before a death he could have avoided. Likewise there is a history of discussion about seriousness and art; Italian Renaissance theorists, like Speroni, when they turned to the poetics of dialogue, noted how the dialogue was a form of play suitable for leisure not work. Dialogue is classified as "commedia", where the effect depends on the variety of characters misunderstanding each other, not the serious work of logic13 If you will, the dialogueb like the game, is theorized as a form that doesn't work when put to work - that doesn't work when filled with serious characters. I see myself in a long line of Grasshoppers who avoid lecturing for chatter, song and, yes play in virtual worlds.

KEVIN: It is easy for you and Suits to play with the fable to suit your ends. Wittgenstein's point still stands and Suits doesn't really answer it by substituting a philosophical dialogue for an answer to the problem of defining. Even Suit's Grasshopper's portable definition to the effect that "playing a game is the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles" (p. 41) suffers from a focus on inefficient means in the pursuit of goals. I think Wittgenstein would answer that the Grasshopper is an example of playing that has no goals, no obstacles and therefore, is no game.

GEOFFREY: And your goal in bringing up Wittgenstein is?

KEVIN: To state the obvious in the face of your pretence of Socratic ignorance - there are things called "serious games" which, even if they don't fit the definitions you deploy, still bear a family resemblance to others types of games that do. Let me admit that “serious games” is a terrible term, but it has a history and is the term used since serious games took off as a field of academic development with the foundation of the Serious Games Initiative at the Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars in 2002 [14]. To understand serious games you need to look at how they described the goals of the emerging field:

“to help usher in a new series of policy, education, exploration, and management tools utilizing state of the art computer game designs, technologies, and development skills. As part of that goal the Serious Games Initiative also plays a greater role in helping to organize and accelerate the adoption of computer games for a variety of challenges facing the world today.” 15GEOFFREY: If you don't like the term what would you propose?

KEVIN: Well, people have called these games - and here I’m referring to the family of “games for teaching and learning” - all kinds of names (and some of them very unkind). Some prefer “simulations”. I’ve used this from time to time, and usually it means a serious game that isn’t any fun. You know, then you’re off the hook. Ian Bogost has gone in a different direction, distinguishing “serious games” from his object of interest: “persuasive games” that leverage the procedural rhetoric (the use of processes) inherent to computers to persuade the player of an opinion or point of view; he contends that the real intent of these kinds of non-entertainment games is to persuade you of a specific argument, not be “serious”. Kindergarten to Grade 12 educators have, since the 1980s, variously called them “games to teach”, or even worse, “edutainment”. When you look at the possibilities, you can see why the term “serious games” stuck.

Figure 4: Screen from Reader Rabbit (The Learning Company)

Simulation and Imitation

GEOFFREY: So, if we set aside the term and definition of games, can you explain what there is to a game that as a game makes it suited to the improvement of youth?KEVIN: Well, I would build on Bogost's discussion of how games work rhetorically. Games represent real or fictional systems with which players can interact, as if immersed in the system. They provide a safe simulation of the experience of the system that players can explore. If properly designed players will form conclusions about the system or world - the constraints, the rules, and the interactive possibilities.

GEOFFREY: Can you give me an example?

Figure 5: Flight Simulator

KEVIN: Well I could talk about how "war games" are used to train officers, and there is a long history of using computers in military training simulations that predates the coining of the term "serious games", but perhaps a better example would be a "flight simulator." Imagine trying to learn something as complex as flying from a book or a lecture. It's obvious that to learn to fly you need to practice flying, and because it's dangerous, it is useful to practice it in a safe environment that immerses you in a world where flying matters.

GEOFFREY: So the persuasive power of the simulator does not lie in an explicit argument about flying - for example, a discussion of the physics of flight in a book - but in immersion in a simulation in which you practice behaviour in a cockpit and are rewarded for the appropriate behaviour.

KEVIN: Right. Serious games as a term gained traction because the people who were doing the work of developing immersive worlds, and applying for funding - think lots of guys in crew cuts and uniforms, working for the Department of Defense - wanted to be taken, you know, seriously. The military had been “war gaming” and “simulating” for decades (as expensive as these are to develop, they’re a lot cheaper than crashing a real F-16 on a real aircraft carrier) and they saw a real future for this kind of work.

GEOFFREY: I can see how you could learn certain subjects in simulation, but a simulation is not a game.

Figure 6: First Responder

KEVIN: Why not? Caillois, who you are fond of quoting, has mimicry or simulation as one of his four categories of games. Espen Aarseth has argued that the hidden structure behind computer games is not story (getting back to the whole ludology-narratology debate), but simulation. Simulation is what drives most "serious games" (you learn to pilot a plane, or to deal with a crisis like a first responder), and simulation is the backbone of all entertainment games - in fact he calls entertainment games a "subgenre" of simulation. In simulations, and I quote, "knowledge and experience is created by the player's actions and strategies". Aarseth calls for recognition of simulation as "a major new hermeneutic discourse mode, coinciding with the rise of computer technology, and with roots in games and playing." 16

GEOFFREY: But this doesn't get to the crux of the matter. The rhetoric of serious games is that of leveraging the "fun" of games for serious ends. The promise of games in education is that we can trick a generation of youth who play games for fun into learning subjects they otherwise find tedious.

KEVIN: And what's wrong with that? As Ralph Koster argues in his book, A Theory of Fun, video games are essentially “iconic depictions of patterns in the world” 17 - they are puzzles made up of symbols and icons that the brain can quickly recognize and understand. A developer's goal is not to capture reality as it is, but rather as it can be interpreted in a game. That usually requires filtering out distracting details, and instead focusing the player's attention on the elements that she needs to understand to be successful.

GEOFFREY: Well, I think you have to decide whether games are going to be simulations or fun. You can't filter out the distracting details if you want a game to be an accurate enough simulation to be educational. If you do simplify the game so its fun then you lose the educational component.

It is like arguing for serious television learning. Students watch TV for fun so why not conceal the bitter taste of the wormwood of education with the honey of the new medium of television. Sesame Street for university students.

No, there is a long history of trying to trick patients into taking their medicine with whatever is the latest flavour. Now it seems that youth like to play first-person-shooters for hours on end so why not try presenting social issues using game engines and trick them into learning? I don't think youth are fooled, at least not for long, just as we weren't fooled by chocolate flavoured cod liver oil. It didn't work with the last new medium television, so why would it work with the new new medium?

To paraphrase Plato from the Phaedrus, no technology, not even writing, is a substitute for the living dialogue with someone who can answer the unexpected question. Everything else is prepackaged and ultimately predictable.

KEVIN: It is easy for you to quote the writings of Plato, but that doesn't make you right, or Plato. After all, you couldn't quote him if he hadn't written and if there wasn't a history of reinterpreting Plato. I think he expelled the poets from the Republic not because they wrote, but because what they wrote wasn't serious. I believe with his dialogues he was trying to re-imagine writing just as we are trying to repurpose gaming.

GEOFFREY: I would agree with your interpretation, but point out that for Plato the problem was one of imitation or simulation. Why not take the argument to its conclusion. The works of the poets, like computer games, were performed, not read. Youth would practice being the characters they performed like they practice killing in shooters. Writings were scripts that you memorized and internalized to build your character. That's what made them dangerous because they tended to script disreputable characters. Plato wanted to expel the poets and replace them with simulations of noble people. To be consistent you would have to take seriously Lt Col Grossman's book, Stop Teaching Our Kids to Kill, and consider banning any game that simulated unethical behaviour. And then where would be the fun that serious games can simulate?

KEVIN: I will agree to a weaker claim that, like any medium, including writing, there are well-designed texts and games, suitable, along with other resources, for teaching a subject, and there are poor resources or works not suitable for a learning objective. The good ones are accurate, deep, engaging and ethically persuasive. They will stand the test of teaching time and have a place in the curriculum once teachers learn to use them. The stronger claim that unethical games should be banned doesn't follow necessarily and you should leave it - you are after all speaking for games against society, aren't you.

GEOFFREY: Ah ... the place in the curriculum. I'm with Plato on this - ban them from the curriculm because that's where things have to be serious and the place of games is not a place of seriousness. As de Castell and Jenson, two of the founders of our Canadian Game Studies association write in “Serious Games”:

“In gaming culture, games are not just played, they are talked about, read about, 'cheated', fantasized about, altered, and become models for everyday life and for the formation of subjectivity and inter-subjectivity. There is a politics, an economy, a history, social structure and function, and an everyday, lived experience of a game” 18We might say that what makes a toy or simulation a game is not the thing itself, but the culture of playing. Poker can be played as a game or can be work for the professional - there is only a family resemblance between the two. A flight simulation can be played for fun or assigned as work in the curriculum. What makes you think there is anything to the nature of a game that makes leisure out of work when you have to discard all the irreverent culture of gaming at the classroom door? Aren't we back to the problem hinted at in the definition of play - that it is only play when you can voluntarily choose to start playing, when you can cheat, alter, and mod the game. Without the culture of play a game is just another assignment.

KEVIN: Why can't we create an educational culture of play around serious games?

GEOFFREY: Because the culture of games, especially that of videogames is a counter-culture defined by its resistance to serious culture. It is a time and space of leisure defined, in the sense of delimited, from work. James Newman, author of Videogames writes that, “game play is its own reward and is clearly distinguished from ordinary life.” (p. 18) All these definitions are not just language games, they are acts of negotiating boundaries.

What if the reason youth play videogames is that they are clearly distinguished through all sorts of boundary making from their parent's serious culture of school and work? What if it is not just the game theorists who are defining games, but everyone who marks the place of games as forbidden territory.

This might explain the fetish status that the violent and sexist features of computer games play in game culture. Those features are the "Do not trespass" signs that mark out gaming culture. The signs work the more they offend. They work because each new version of Grand Theft Auto is guaranteed to trigger a critical reaction in the New York Times that then reinforces the idea that adults just don't get it. Both sides, the serious press and the gamer press benefit from the debate, shoring up their side of the fence. Both sides play out a dialogue of the deaf where neither side really listens to the other because neither plays to the audience of the other. They mutually define games as the line in the sand, the line that separates work and play, adult opinion and its youthful other, what it is to be serious and how to transgress.

KEVIN: Fine speech. I'm surprised you didn't weave Foucault and disciplining youth in somehow. You sound worried that serious gaming will succeed - that we actually can move that line, if it really exists. In other words, that serious games will cross the line and spoil the fun. Isn't it ironic that you find serious games so threatening of some order - threatening just as games should be?

GEOFFREY: Exactly. To paraphrase every angry blog response to the perennial eruption of public anxiety about violent games - back off and leave that which you don't understand alone. But seriously, instead of Foucault I would mention Bakhtin here and the need for carnival. Caillois also talks about the games as carnival - the carnival is that defined place and time for transgression when you can play with masks without really threatening the established order, which is why games are tolerated. We all know what the boundaries are, when we are playing and when we aren't. The spirit of games is to keep the carnival in games or the game in the carnival.

KEVIN: How conservative a view this is of gaming. You talk as if leisure was an endangered cultural heritage activity that has to be preserved from work. I think game culture is far more resilient and that it is ready to embrace imaginative work, even serious game design. Your problem really lies in your rigid opposition of work and play. There is “work” and there is “play”, but there are moments where “work” becomes “play” and vice versa. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who stood at this podium two years ago and gave a plenary address to the first Immersive Worlds conference, made this argument. Over the course of many years, Csikszentmihalyi and his colleagues, who form a kind of academic all-star team, have, to grossly oversimplify, given beepers to thousands of people - concert pianists, auto manufacturer line workers, homemakers, professional football lineman, etc.19 And when the beeper has gone off, at random times of the day, over many days, the research subjects have noted what they were doing at the time, and how they were feeling. Out of this research has come a theory of “flow”: we are most happy when we are in a state of “flow” - a state in which we are fully immersed in what we are doing. To be in “flow” is to be “in the zone” or “in the groove”, a feeling of being completely involved in an activity for its own sake. We lose all sense of time. We are completely absorbed. Every action follows from the previous one. Our whole being is involved, and we’re using our skills to the utmost20

Flow can occur for an auto manufacturer line worker when he is completely focused on using his skills to do his job to the best of his ability. It can occur in conversation when you lose track of the time in the playful exchange. For some, these activities may be tedious work, but for others they are play because their interests and skill sets are matched.

GEOFFREY: Sure, there can be flow in any activity, but it is unpredictable, so why games? One person makes a game out of learning while another struggles.

KEVIN: Exactly, so why not help those that struggle with learning games.

GEOFFREY: Because you can't control the flow. You can't script the flow of learning as we did for today's dialogue.

KEVIN: Why not? That’s what good game designers do. They modulate rhythm of the game, they introduce challenges in an appropriate stepped sequence, and they test their games to ensure that players are immersed not frustrated. It’s like any other art. You can't define it - there isn't a recipe, but some people learn the art.

GEOFFREY: Perhaps then it is game design that is the serious play? Perhaps the exhilaration of playing is most serious when it flows into designing games for others. Wouldn't that be a way to teach with games - to create a context - an educational game culture where others can learn to make games, serious or not?

KEVIN: Well, that question raises a host of others. But these will require another dialogue. Right now it seems that, finally, we agree on something, which sort of spoils the fun of arguing with you.

GEOFFREY: Then that must be the end of this conversation and time for some charming wine.

“Yet individuals can once again become involved, and thought and action can again be integrated, in games created to simulate these social processes. The zest for life felt at those exhilarating moments of history when men participated in effecting great changes on the models of great ideas can be recaptured by simulations of roles in the form of serious games” 21

Endnotes:

1 This dialogue was performed at the 2009 Interacting with Immersive Worlds Conference at Brock University in St. Catharines, Canada. For more information about the conference see: http://www.brocku.ca/conferences/immersive-worlds

2 Justin Peters, "World of Borecraft," Slate, June 27, 2007. http://www.slate.com/id/2169019/fr/rss/

3 Thus Socrates starts his interrogation of Meletus in the Benjamin Jowett translation of Plato's Apology at 24d.

See: http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/apology.html. Socrates was accused of corrupting the youth much as games are. In the Apology he defends himself partly by questioning his accuser. As Socrates says, he will show, “O men of Athens, that Meletus is a doer of evil, and the evil is that he makes a joke of a serious matter, and is too ready at bringing other men to trial from a pretended zeal and interest about matters in which he really never had the smallest interest. ” (24c) Of course, in this dialogue it is less clear who is making a joke of serious games.

4 Frasca, “Ludologia kohtaa narratologian”.

5 The discussion concerning the inherent structure of computer games was dominated for several years by an argument, generating considerable heat but little light, between so-called “ludologists” and “narratologists”. The definitions seemed to change regularly, and members of each camp were often surprised to find themselves placed there. In brief, the “narratologists” were researchers with a background in narrative forms such as the novel, theatre, and film, who seemed to herald computer games as a new form of storytelling (Murray, Hamlet on the Holodeck; Laurel, Computers as Theatre; Manovich, The Language of New Media). In an attempt to work out the potential for emerging digital media, they had turned to modes of analysis concerned with these earlier, established narrative forms. The “ludologists” argued that games were not stories, but rather a new form of entertainment that required a new mode of analysis. Drawing on their backgrounds (often in computer science and design), they promoted understanding the potential of computer games through a focus on the mechanics of game play (Juul, “Games Telling Stories?”; Pearce, “Towards a Game Theory of Game”; Frasca, “Ludologia kohtaa narratologian”).

6 In World of Warcraft, the most popular MMORPG (Massively Multi-Player Online Role-Playing Game) today (with approximately 12 million monthly subscribers) (Blizzard Entertainment, “World of Warcraft Subscriber Base Reaches 11.5 Million Worldwide,” 2008, http://eu.blizzard.com/en/press/081223.html), a player takes on a character in the game world, then joins a guild of other player-characters who work together to complete quests.

7 For more information, see http://www.bitcasters.com/.

8 Huizinga, Homo Ludens. p. 13

9 Caillois, Man, Play and Games. p. 9 and 10

10 Ibid. p. 44

11 Suits, The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia. p. X of the "Preface"

12 Aesop, "The Ant and the Grasshopper." http://www.bartleby.com/17/1/36.html

13 Speroni's Apologia theorized dialogue in an unsuccessful attempt to prevent his dialogue from being put on the Index of forbidden books. There are interesting parallels between the evolution of the dialogue as a playful philosophical genre and the emergence of serious games. In both cases there are moves to "clean them up" and demonstrate that they can be serious, which of course dialogues are, unlike games. For more see Rockwell, Defining Dialogue.

14 See http://www.wilsoncenter.org/index.cfm for more information about the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

15 About page of the Serious Games Initiative. http://www.seriousgames.org/about2.html

16 Aarseth, p. 52-53.

17 Koster, p. 34.

18 De Castell, “Serious Play”

19 More information about the “Good Work Project”, lead by Csikszentmihalyi, William Damon, and Howard Gardner, can be found at http://goodworkproject.org/.

20 Csikszentmihalyi, Flow.

21 Abt, Serious Games, p.4

Bibliography

Abt, C. C. (1987). Serious Games. Lanham, MD, University Press of America.Aarseth, E. (2004). Genre Trouble: Narrativism and the Art of Simulation. In Noah Wardp-Fruin & Pat Harrigan (Eds.), First person: New media as story, performance, and game. (45-55). Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England: The MIT Press.

Caillois, R. (1961). Man, play, and games. (Meyer Barash, trans.) New York: The Free Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1991). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper Perennial.

De Castell, Suzanne and Jennifer Jenson. "Serious Play", Journal of Curriculum Studies, 35/6 (2003). http://faculty.ed.uiuc.edu/westbury/jcs/Vol35/decastell.html

Frasca, G. (1999). Ludologia kohtaa narratologian. Parnasso 3, 365-371. Published in English as Ludology Meets Narratology: Similitudes and Differences Between (Video) Games and Narrative. http://www.ludology.org/articles/ludology.htm [Accessed August 18, 2009].

Huizinga, J. (1950) Homo ludens: A study of the play-element in culture. Boston: Beacon Press.

Grossman, Lt. Col. Dave and Gloria DeGaetano. (1999). Stop teaching our kids to kill: A call to action against TV, movie & video game violence. New York: Crown Publishers.

Juul, J. (2005). Games telling stories? In Raessens, J. & Goldstein, J. (Eds.), Handbook of Computer Game Studies (pp 175-189). Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Koster, R. (2005). A theory of fun for game design. Scottsdale, Arizona: Paraglyph Press.

Laurel, B. (1991). Computers as theatre. New York: Addison-Wesley.

Manovich, L. (2001). The language of new media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Murray, J. (1997). Hamlet on the holodeck: The future of narrative in cyberspace. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Newman, J. (2004). Videogames. New York: Routledge.

Pearce, C. (2004). Towards a game theory of game. In Wardrip-Fruin, N. & Harrigan, P. (Eds.), First person: New media as story, performance, and game (pp. 143-153). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Plato, Apology. trans. Benjamin Jowett. The Internet Classics Archive: MIT. http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/apology.html

Rockwell, G. (2003). Defining dialogue: From Socrates to the internet. Amherst, New York: Humanity Books (an imprint of Prometheus Books).

Speroni, Sperone. Opere. Ed. Marco Forcellini and Natal dalle Laste. 5 volumes. (Padua 1740. Volume 1 reprinted, with a forward by Mario Pozzi, Rome: Vecchiarelli, 1989.)

Suits, B. (1978).The grasshopper: games, life and utopia. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Wittgenstein, L. (2001). Philosophical investigations. (G. E. M. Anscombe, trans.). Third Edition. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Games

HistoriCanada - http://www.historicanada.com/

Reader Rabbit, The Learning Company, 1989.

September 12th - http://www.newsgaming.com/games/index12.htm World of Warcraft.