A Survey of First-person Shooters and their Avatars

by Michael HitchensAbstract

The First-Person Shooter (FPS) is a popular game form, with examples appearing on many different platforms. The genre has an almost two decade history and is represented by hundreds of commercial titles. While there has been extensive study of the FPS genre, this has tended to focus on particular games, or at best a limited set of examples. In order to provide a wider context for such work this paper surveys 566 separate FPS titles, across a range of platforms. The titles are compared by year of release, platform and game setting. Characteristics of avatars within the surveyed titles are also examined, including race, gender and background, and how these vary across platform and time. The analysis reveals definite trends, both historically and by platform.

Keywords: First-person Shooter; Avatar; History; Statistical survey; Gender; Race

Introduction

Figure 1 shows Wolfenstein 3D (id Software, 1992), the face of the avatar, B.J. Blazkowicz, directly in the centre of the player’s view. This avatar is well-defined: a caucasian male, with a military background. Wolfenstein 3D initially appeared on IBM PC compatibles and has been called the foundation of the First-person Shooter (FPS) genre (Malliet & de Meyer, 2005). There were earlier ancestors, and Catacomb 3-D (id software, 1991) perhaps has a better claim to being the first, but Wolfenstein 3D played a central role in promoting the style’s popularity. In the 18 years since its release hundreds of titles have followed and the FPS is now a popular and commercially successful video game style (Cifaldi, 2006). Some examples, such as the Bioshock (Irrational Games, 2007), Halo (Bungie 2001) and Half-Life (Valve, 1998) series, have sold millions of copies. FPS games have been released across a range of platforms, from its origins on the IBM PC and other home computers such as the Macintosh and Amiga to over a dozen different game consoles and now with an increasing presence on modern mobile phones. Yet how far has the genre come since the release of Wolfenstein 3D? Is it still dominated by the likes of B.J. Blazkowicz, in his original home of the PC? Or have other platforms and avatar types come to prominence?

Figure 1: Wolfenstein 3D

The FPS is characterized by a first-person viewpoint and a heavy emphasis on combat, typically involving firearms. Removing the avatar from the player’s field of view both makes these games distinctly visually different from those with a third-person perspective, but otherwise similar gameplay, such as Max Payne (Remedy Entertainment 2001), and locks the player’s and avatar’s views together. Even more, as noted by Klevjer, (Klevjer, 2003, p.1) “Looking and targeting came together in the same movement, and the player was invited to, as it were, follow his gun”. Given the absence of the avatar from the player’s view (except, perhaps, for a hand as in figure 1) it could be asked whether the characteristics of the avatar matter. Gameplay in FPS games is focused through the avatar. As noted by Pinchbeck (Pinchbeck, 2007b) all the affordances a player has in a FPS game are provided through the avatar.

The time since the release of Wolfenstien 3D has seen the maturing of game studies as a discipline. We now have a much greater understanding of the nature of games and how they are played than might even have been imagined in the early nineties. However the bulk of research has concentrated on either analyzing or employing a small number of titles (and sometimes only one). This is as true for studies focusing on the FPS as for those examining other genres. While this has been sufficient to the individual needs of those studies, the result is a lack of wider-ranging data that can help provide context for the detailed cases. It can then be difficult to assess a work’s full worth and to know how, and if, to generalize any results.

There is considerable research on FPS games, for example examining their aesthetics (Klevjer, 2006), the relationship between FPSs and narrative (Aarseth, 1999; MacTavish 2002), avatar categorisation for FPSs and other game styles (Kromand, 2007), the role of the avatar in an FPS (Klevjer, 2003), player behaviour in FPSs (Pinchbeck et al., 2006) and player recall of events in a FPS (Pinchbeck, 2007a). This literature covers a significant range, but share one common feature - the number of games used as concrete examples is small. This ranges from a single game, Half-Life 2 (Valve, 2004), with about half-a-dozen more fleetingly mentioned, in the case of (Pinchbeck et al., 2006) to 24 in (Klevjer, 2006). In some cases, such as empirical studies, it is logistically difficult to employ a large number of games. In other examples the range chosen is more than sufficient for the topic addressed.

In this paper, rather than examining a particular aspect of FPSs through a limited number of examples, we attempt a wider (and admittedly relatively shallow) analysis of the basic characteristics of the form. We present a quantitative survey of over 550 FPS titles. While this is not exhaustive, in that we do not claim every FPS title is included, it does appear to be a more than significant fraction of them. We present basic data on the platforms on which the games were available, release dates and some basic characteristics of the player avatars, such as gender, race and background. How these vary over time and platform are also considered. This allows us to answer some basic characteristics about the development of the genre, including

- How, if at all, has it changed over time, in terms such as avatar characteristics and setting.

- Are there significant differences, in the terms mentioned, between FPSs that that exist on computers and those that exist on consoles.

While space in this paper prohibits investigation of the consequences to the answers to these questions, they can give both a context to other work and illuminate opportunities for future investigation.

Range of the Study

The modern FPS traces its roots to Wolfenstein 3D (Malliet & de Meyer, 2005) and Catacomb 3-D. The current study therefore commences from these games. Comparing the games covered here to their ancestors could be useful, but it was considered best to limit ourselves to subjects more directly comparable. This principle (games where comparison appears reasonable) was used in choosing the limits of the study. The FPS is not the only style of game that uses a first-person perspective. To keep the study within manageable limits while attempting to compare “like to like” it was decided to include only games that:

- Employ a first-person perspective.

- Give the player an anthropomorphic avatar that interacts directly with the game world.

- Have as the primary gameplay mode both the player avatar attempting to damage other game entities and those game entities attempting to damage the player avatar.

- Place movement of the player avatar mainly under the control of the player.

The second requirement excludes flight simulators, mech and other vehicle based games. The third requirement precludes hunting games (where the in-game entities not controlled by the player do not fight back). The final requirement excludes “on-rails” games such as Touch the Dead (Dream On Studio, 2007) and other arcade style shooters, where the player avatar moves through virtual world under the control of the game engine, and also games where the player occupies a turret or other emplacement and waits for the opponents to attack.

On the basis of the given characteristics roleplaying games that enable a first-person perspective are also excluded from the study. Roleplaying games are usually considered to form their own genre, with distinguishably different characteristics and gameplay to those listed above. For example, a roleplaying game will usually allow all of the following: character development, open world navigation (as opposed to distinct levels which cannot be returned to once completed) and extensive non-violent interaction with NPCs. For example, The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind (Bethesda, 2000) employs a first-person perspective, but fits the short definition of a roleplaying game just given and is not included in the survey. On the other hand, System Shock 2 (Irrational Games, 1999) is considered a FPS for current purposes, as it lacks extensive dialogue interaction with NPCs. Deus Ex (Ion Storm, 2000) is also included here, as its world consists of distinct levels. For more discussion of the definition of a roleplaying game used here in deciding whether or not to include certain games, see (Hitchens, 2008).

The number of titles included in the survey does not count expansion packs which require the original game. Information from those is combined with the original game. Stand-alone sequels are counted separately. Also not included are mods, free open source ports and non-commercial releases. Finding exhaustive information on these would be prohibitively difficult and, as many non-commercial releases are never truly finished, it would be problematic to decide which to include. Free to play multiplayer FPSs are included, if those games include some commercial element, such as micro-transactions.

In collecting the survey data, and in compiling the results, no account was taken of sales figures for games. Admittedly, this means that obscure titles count for as much as million-plus sellers. However, the alternative is not altogether clear. Weighting the results by sales figures is impossible, as the necessary data is not available for many titles. It is difficult to know how to interpret any results from such an approach. Another possibility would have been to only consider games which managed to sell above a certain cut-off. However, again limited data prevented this approach, and any such choice would be potentially subjective. A commercial release represents a notable contribution to the genre, and hence was decided upon on as the criteria for inclusion.

In effect, and not accidentally, the limitations give games in the style of Catacomb 3-D and Wolfenstein 3D. A player avatar, which is essentially the physical body of the avatar, moves through a virtual space under the control of the player. Movement is free and contiguous or at least as free as the virtual space and the limits of technology allow. Combat is the central, though not necessarily exclusive, game play mode. This is not to say that the games excluded are uninteresting. However, in the interests of space and logistics the limits imposed appear to be useful.

Method

The early choices in a survey of this nature concern the sample size and how the data is to be gathered. A smaller sample allows more detail, but risks statistical anomalies due to accidents of chance in the sample taken. In some fields where similar surveying, such as motion pictures, has been attempted the possible pool of data is so large that exhaustive surveying is logistically impossible. For example, in a survey of smoking in movies from 1960 to 1990 (Hazan et al., 1994) two films per year (for a total of 62) were considered to be sufficiently representative. This is a very small percentage of the number of films that could have been examined. By restricting the study to a single type of game, the FPS, the chance exists to include a much greater percentage of existing titles. By extensively searching we hope to have included at least half, if not a much greater proportion, of the possible titles.

While this significantly decreases the chances of statistical anomalies, it is not possible to play that many games for a single study. For the greater part reliance was placed on secondary sources for information. The most important of these was www.mobygames.com, which includes images of many of the game boxes (front, back and, where applicable, inside covers). While not a primary source we consider them to be useful and reliable. Also consulted were reviews, from magazines such as PC Gamer and PC Powerplay, online sites such as www.gamespot.com and screenshots, hosted at various online including those already mentioned.

The accuracy of these secondary sources was verified by comparing them to first-hand information about a selection of the games. 63 games were played in whole, while a further 15 in part and the findings compared to the secondary sources. In no cases were any errors found in the secondary sources, giving a high level of confidence in their accuracy concerning the remaining games.

For each game the following information was sought:

- Year of first release

- Platforms on which the game was available

- Gender of the avatar(s)

- Ethnicity of the avatar(s)

- Background of the avatar(s)

- Game setting

More information could be mined from these games, for example the weapons available, the avatar’s name, the use of role-playing game like character improvement in skills, and so on. However, the more detailed the information the harder it is to obtain from the secondary sources and the above represents information that could be obtained for a high percentage of the games studied.

Results

The games surveyed ranged from 1991 to 2009 (figure 2). As the time of writing is part way through 2010 complete information for that year is unavailable. We are addressing trends on a yearly basis so it was thought best to omit what 2010 data was available as including it would give an incomplete picture of that year. The reader is asked to note the low number of games found for 1991 (one) and 1992 (three) and to bear this in mind when considering the results for those years in later sections. The small numbers lead to some apparently anomalous results for those years. While those years could have been omitted from later analysis, it was thought best to include it with the just given proviso.

Figure 2: Distribution of titles by year

After the release Catacomb 3-D in 1991 the number of games found rises rapidly. This may result from multiple game developers and publishers seeking to exploit opportunities in the newly popular genre. The fall in the sample data between 1995 and 1996 can perhaps be explained by the increasing graphical sophistication required of FPSs with the release in the later year of games such as Quake (id software, 1996). The increased development time and budgets required may have served to thin the number of games coming to market. Another possible factor is the decline of non-IBM PC computer platforms as FPS platforms. In 1995 seven FPS games were released for the Amiga and one for the Atari ST. In 1996 that shrunk to two titles, Alien Breed 3D II: The Killing Grounds (Team17, 1996) for the Amiga and Marathon Infinity (Bungie Software. 1996) for the Macintosh. After 1996 only four more FPS titles were found that have been released for a non IBM-PC computer platform without a corresponding IBM PC version. These four titles were all for the Amiga and were released in 1997 and 1998.

From 1996 to 1999 the IBM PC reigned supreme as the platform for FPSs. Of the 87 titles released in that period, only 13 were not available for the PC. This is 85 percent of titles playable on the PC versus the figure of 76 percent for the period 2000 to 2009. The overall figure from 1991 to 2009 is 80 percent. Of the 74 PC titles, 45 were available solely on that platform while 29 had versions on other platforms. Included in the latter figure are a number of well-known games which could considered PC games but were later widely ported, such as Quake, Quake II (id Software, 1997) and Half-Life. Only seven titles in this period were home console-only.

The importance of home gaming consoles as FPS platforms accelerated from 2000. 2000 and 2001 produced a total of 10 games playable only on consoles, compared to seven in the preceding four years. The overall total of titles available on consoles, including those available on computers as well, was 24 of 87 in the period 1996 to 1999 (26 percent). In 2000 to 2009 it is 225 of 405 (56 percent).

Figure 3: Number of titles available on non-computer platforms

Figure 2 shows a sharp rise in overall numbers from 2002. This might be explained by the FPS’s increasing presence on home gaming consoles and, later in the decade, mobile phones (figure 3). The marked increase in 2009 is at least partially explained by a continuing rise in the number of titles available for mobile phones. Of the 53 titles from 2009 11 of them are mobile phone-only releases. The two series in Figure 3 depict (1) the games available only on console and (2) the games available both on consoles and computers. The impact of the sixth and seventh generation home consoles (PS2, PS3, Xbox, Xbox360, Gamecube and Wii) can be clearly seen. The increased power, and particularly graphical capacity, of these consoles over their predecessors appears to have opened up the home game console as an FPS platform.

The dramatic impact of the mobile phone can be seen in the console only series from Figure 3. 18 titles which can only be found on mobile phones are included in the survey. Of these four are from 2008 and, as mentioned above, 11 from 2009. Given the more ephemeral nature of the mobile phone game market it is possible that the survey has missed a significant number of such games, but their inclusion would only further highlight the trend away from the IBM PC.

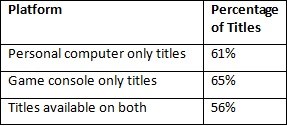

Table 1. Number of titles included in survey, by platform

FPSs have appeared on many different platforms (table 1). The second column gives the number of titles released for each platform, the third column gives the number of those titles released only for that platform and is a subset of the second column. The historically dominant role of the IBM PC in the FPS world is immediately obvious. The figure is perhaps a little misleading, as it includes all games available on any version of Microsoft DOS or Windows. Many games were released for both DOS and Windows and individual sums for each version of the Microsoft operating system were impossible to determine. Perhaps fairer is to combine version generations of console systems. The closest to the IBM PC are then the Playstation family, with 149, and the Xbox family, with 146. These totals count titles released for a number of members of a family only once, so do not quite match the totals by adding the entries in table 1.

While porting of games is not uncommon, most games have only been released for a single platform. In the sample surveyed, 353 games (62 percent) were released for a single platform, 213 (38 percent) were released for multiple platforms. However games available on platforms other than the PC are much more likely to be ported. While the 255 games available only on the PC represents 58 percent of the titles available for that platform, that leaves 311 titles available on other platforms. Of these only 98 (32 percent) are available on only a single platform. While the IBM PC is not the only home computer platform for FPSs, the others (the Macintosh, Amiga and Atari ST) are not particularly significant. All the Macintosh games, apart from the four solely available for it, Pathways into Darkness (Bungie Software, 1993), Sensory Overload (Reality Bites, 1994), Marathon (Bungie Software, 1994) and Marathon Infinity (Bungie Software, 1996), are available on the PC. The Amiga contributes only 3.2 percent of the total - although interestingly a high proportion of them were only ever available on that platform (12 out of 18). Only a single example for the Atari ST, Substation (Unique Development Studios, 1995), was found.

The proportion of titles solely available on the PC falls in the latter half of the surveyed period. In the period 1991 to 2001, of the 205 titles included in the survey 107 (or 52 percent) were solely available for the PC. For 2002 to 2009 this falls to 40 percent (144 out of 361). However, 33 further titles from 2002 to 2009 exist on the PC and either the Xbox or Xbox360, but no other home console. Including these games raises the percentage in that period to 49 percent, close to that of the preceding decade. Whether these games would have been PC-only titles can only be speculated upon, but it is clear that the advent of the seventh generation consoles has loosened the PC’s grip on the FPS. The same period has seen a range of titles from Eastern European studios available only for the PC. Perhaps the most well-known of these are the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. (GSC Game World, 2007) titles, but many other examples exist, such as the military themed games published by City Interactive of Poland. The PC is a popular development platform in Eastern Europe and other developing areas, for a variety of reasons. Without this support from outside traditional development areas the proportion of PC-only titles would probably have fallen further.

Figure 4: Percentage of releases in platform categories

Figure 4 displays trends in platform releases as percentages by year. Note that the values in each year for series one and two add to 100 percent, as do those for series three and four. The early dominance of home computers can easily be seen. Marked changes in the figures appear to roughly co-incide with the release of recent console generations. With the advent of sixth generation in 2000 the percentage of releases available on console platforms rises noticeably. With the seventh generation in 2005 the percentage of titles released only for home computer systems for the first time slips consistently under 50 percent. In 2009 console releases top computer releases for the first time.

FPSs appear in many variants. For example there are single player games, multiplayer games and those which support both. Despite the attention they sometimes receive, games which have multiplayer as their main, or only, focus are distinctly in the minority, only 55 being found in the data surveyed - less than 10 percent. The earliest of these is Starsiege Tribes (Dynamix 1998). Since then only a few have been released each year, with the highest number being 11, in 2007. These figures do not include titles with a significant multiplayer aspect, but only ones where it is the overwhelming rationale of the game. For example, while Quake famously had a multiplayer component it could not be claimed that this was the primary focus of the game’s design. Of these 55 titles only seven are not available on the PC. 37 out of the 55 (67 percent) exists solely on the PC (or PC and Macintosh). Remembering that these titles occur mainly in the latter period of the period this contrasts strongly with the general trend over that time.

While the IBM compatible PC remains the platform with the greatest number of FPS titles it is being challenged by the increasing sophistication of the home-console platforms and the convenience of mobile phones. Whether it remains so may depend on the success of the home-console platforms in expanding into markets where the PC remains strong, such as in network play and certain geographical regions.

Avatar Gender

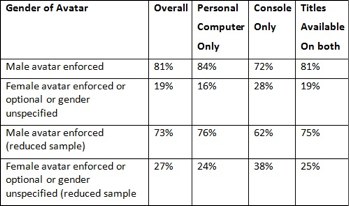

Of the 566 games surveyed, information about the gender of the player avatar was gathered for 482. The distribution, both overall and by platform, is given in table 2.

Table 2. Avatar Gender Distribution by platform

The first two rows show games in which the player is offered no choice in the gender of their avatar(s). The heavy skew towards male avatars is apparent. The third row shows games in which more than one avatar is played over the course of the game and both genders are represented. The fourth row games in which the player is able to choose the avatar gender. The fifth row games in which the gender of the avatar is unspecified. The number of games enforcing a male avatar is affected by 140 titles (29 percent of those for which avatar gender information was found) with settings in which male avatars might be expected to be the only option - for example soldiers in WWII or in contemporary military organisations which do not allow front-line female combatants. The final row gives the figures for male avatars when these games are not considered. This still leaves a large number of games with fixed male avatars in settings (such as science fiction or contemporary non-military) that do not of themselves restrict the choice. That such fixation on the male avatar cannot be said to be driven by story-based needs is shown by such games as Deus Ex: Invisible War (Ion Storm, 2003). Notable for its complex story, that game allows the player to choose both the gender and race of their avatar. While allowing the players choice may result in additional development costs, for example additional graphical assets and duplicated voice recordings, it is at least possible that this cost saving is outweighed by the disenfranchising of potential players. The figure of 49 for games that give the player the choice of avatar gender is slightly misleading, as 25 of these are multiplayer games where the choice of avatar is primarily cosmetic. In single player FPSs the male avatar dominates.

Table 3. Avatar Gender Distribution percentages by platform

When gender is considered by platform personal computers offer a slightly less balanced gender choice than other platforms (table 3). The difference is marginal (except when compared to titles only available on non-PC platforms) and the fixed male avatar dominates across all platforms. The last two rows are calculated without the 140 titles mentioned above.

Figures 5 and 6 display the trends of gender options of playable avatars over time. In both cases the data used discounts the 140 titles with setting-enforced male avatars. Figure 6 gives the raw numbers of the remaining 342 titles, showing games where a male avatar is enforced versus those where a female avatar is possible (for at least part of the game). In the period 1994 to 2000 the number of male focused titles released per year remained relatively constant (around 10). A slow rise is seen in the number of titles were it is at least possible to play a female avatar, from their first introduction, in Rise of the Triad (Apogee Software, 1994) and Zero Tolerance (Technopop, 1994), with the two almost meeting in 2000 (nine titles versus seven). After 2000 there is a noticeable shift, with male avatars increasingly predominating. An exception is 2007, but that can be explained by the release that year of a relatively high number (seven) of multiplayer games which allowed choice of avatar gender.

Figure 5: Male avatar (mandatory) versus Female avatar (mandatory or possible)

This changing trend before and after 2000 can be seen even more clearly when the relative percentage is considered (figure 7).

Figure 6: Percentage of releases where playing a female avatar is possible

Explanations for the trend away from female avatars are not immediately obvious. However, a clue may be discovered by examining the 140 titles excluded from the above discussion (figure 7). Apart from the 1992 entry, representing Wolfenstein 3D and Spear of Destiny (id Software, 1992), this type does not appear again until 1998, when it rapidly becomes a significant factor, representing 30 to 40 percent of releases each year. While this does not directly explain why those titles where a male avatar is not dictated by the choice of setting it may indicate an influence on design choices.

Figure 7: Percentage of releases where setting/background mandates a male avatar

Of the 20 titles in the survey were a female character is mandatory, almost half, Perfect Dark (Rare, 2000), Perfect Dark Zero (Rare, 2005), Metroid Prime (Retro Studios, 2002), Metroid Prime: Hunters (Nintendo Software, 2006), Metroid Prime 2: Echoes (Retro Studios, 2004), Metroid Prime 3: Corruption (Retro Studios, 2007), The Operative: No One Lives Forever (Monolith Productions, 2000) and No One Lives Forever 2: A Spy in H.A.R.M.'s Way (Monlith Productions, 2002) are part of series. As sequels usually indicate commercial success a female avatar appears to be little barrier to sales success.

11 games were identified where the gender of the avatar is not specified within the game, e.g., Killing Time (Studio 3DO, 1995) and Strife (Rogue Entertainment, 1996). This is typically accomplished by either no depiction of the avatar within the game or by complete coverage in armour, combat suit or other full body coverage. As graphical sophistication, and the use of cut-scenes, has increased, this ambiguity has lessened. Even games like Halo, where Master Chief never removes his armour, leave no doubt that the avatar is male. It should be noted that of the 84 games excluded from discussion in this section it is possible that the avatar gender could not be determined simply because it is unspecified. Only games where it was definitely found to be unspecified have been included in this section. 47 of the 84 games excluded are from early in the survey period (1993-1998), and make less use of cut-scenes and similar techniques, leaving details about the avatar, such as gender, ambiguous. Similarly, there are another 12 games that are mobile-only, and subject to some of the same technical limitations. The total given in table 2 as “unspecified” may be an underestimate.

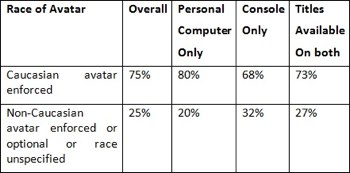

Avatar Race

Racial information about the avatar could be determined for 463 titles (table 4). The same comments apply about games where the ethnicity of the avatar could not be determined as those just made about gender. Of the games (103 in this case) excluded from this section almost two-thirds either come from early in the survey period (53 from 1992 to 1998) or are only available for mobile phones (13 titles). Again, it may be that lack of cut-scenes, etc, has left the race of the avatar unspecified. Only titles were it was possible to determine that the race is definitely unspecified have been included.

The first four rows of table 4 represent titles where the player has no choice in avatar race. The row “multiple” records games where the player plays avatars of different races during the game or where they have a choice of racial background for their avatar. A large percentage of the games where multiple races are playable (28 out of 67 or 42 percent) are multiplayer-focused titles. In none of these 67 games is it impossible to play a Caucasian avatar. In fact, many of them weigh heavily towards the Caucasian, for example, Global Operations (Barking Dog Studios, 2002) gives you a choice of six avatars - five Caucasian, one African-American. The final row records games where the race of the avatar is unspecified.

Table 4. Avatar Racial Distributio

It may be thought that, with the player’s view and the avatar’s being the same, the avatar’s race would not be often brought to the player’s attention. In some early games, such as Wolfenstein 3D, the presence of the avatar’s face in the interface is an obvious counter-example. In more recent games cut-scenes may depict the avatar in a third-person view. In many FPSs the avatar’s hand is consistently in the centre of the player’s view. In some, such as Bioshock, the avatar’s skin colour makes their race apparent. That this is unnecessary is shown, for example, by F.E.A.R. (Monolith Productions, 2005), where gloves and sleeves are used to cover the visible parts of the avatar. Games such as Halo and Timeshift (Saber Interactive, 2007) keep the entire avatar covered, in some form of combat suit, so that even third-person cut-scenes leave the avatar’s race unspecified.

Figure 8: Neves of Steel box art

The lack of detail in earlier games in both avatar features and colour definition may be thought to leave some room for interpretation. However, the intent in many cases is left in little doubt by the evidence of game boxes, for example Nerves of Steel (BnB Software, 1995), figure 8 (from www.mobygames.com), and other information. It could be argued that such illustrations are the product of marketing, not the game designers. However, if these are the only elements the player has in forming the impression of the avatar then they must, by default, prevail.

Figure 9: John Blade, from SiN

There are very few clearly seen avatar models where racial background is undefined. One example is John Blade (figure 9), from SiN (Ritual Entertainment, 1998). Here the use of goggles to hide eye colour and shape and the middle-range skin tone leave scope for interpretation.

While the dominance of the Caucasian avatar is more marked in computer only, even on console only or computer and console titles the predominance remains (table 5).

Table 5. Avatar Racial Distribution as percentages

Figure 10 shows the percentage of titles released each year where either there is no requirement to play a Caucasian avatar for the entire game or the avatar’s race is undefined. This is the 116 games from the first column of table 4. There is a slight (although not significant) downward trend, perhaps explainable by the increased specification brought by improved graphics, leading to a decline in the unspecified category. Another contributor might be the rise, since 1998, of games which enforce a male avatar. While that does not in itself enforce a Caucasian avatar (even in WWII western armies were not wholly Caucasian by any measure) in 122 of those 140 games the player is presented with no choice but to play a Caucasian avatar. It could be argued that Caucasian is not a monolithic block. For example, national backgrounds such as Spanish, Italian and Irish occur alongside the more typical American or British. There are also six games offering Hispanic-American avatars (although the majority of these are from the Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six series, so it cannot be said to be widespread). These are still Caucasian, and distinctly separate from Asian, African or North American Indian avatars.

Figure 10: Percentage of releases where a non-Caucasian avatar is possible

Figure 11 graphs the percentages over time of titles where a non-Caucasian avatar is possible by platform. Games which focus mainly on multiplayer have been removed from this calculation, to reveal any underlying trends when the question is not one of simply providing another avatar skin. The dominance of the Caucasian avatar on the PC is reasonably constant over time. While the figures vary considerably from year to year, as may be expected given the relatively small number of such releases, it does show that the proportion of such titles available on both computers and consoles is consistently higher than that available for computers only. There is no readily apparent explanation for this trend, it may simply be that designers looking to expand their potential market by multi-platform release are also using the avatar to attract to the widest possible audience.

Figure 11: Percentage of releases where a non-Caucasian avatar is possible by platform

The above comparisons have been mainly between games where a Caucasian avatar is compulsory and those where it is, to some extent, optional, This may be because the player can choose the avatar’s ethnicity, as in Deus Ex or the player has a number of avatars, from a range of ethnic backgrounds, over the course of the game, as in Call of Juarez (Techland, 2006). In neither case is the player prevented from playing a Caucasian avatar for at least part of the game. Only seventeen games were identified were the avatar’s ethnicity is explicitly non-Caucasian and the player is given no other choice. The earliest game identified where the player must play a non-Caucasian avatar was Shadow Warrior (3D Realms, 1997) which has an Asian avatar.

While racial choice overall may seem limited, it is even more restricted when female avatars are examined. Of the 20 titles which enforce a female avatar 18 make that avatar Caucasian. The only exceptions are Portal (Valve, 2007) and Mirror’s Edge (Digitial Illusions CE, 2008), whose avatars have Asian and Eurasian ethnicity respectively, Note this means no games were found which enforce a female avatar of North American Indian or African/African-American ethnicity for the entire game. Some multiplayer games allow extensive choice in avatar design, however when only single player games are considered such choice usually does not exist. Two single player games were found that do allow extensive avatar customisation, essentially allowing female avatars of any ethnicity - Deus Ex: Invisible War and Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six: Vegas 2 (Ubisoft Montreal, 2008). These are exceptions, single player games which allow a choice of male or female avatar tend to present only Caucasian females, even when the ethnic choice is larger in the male avatars, examples of this include Conflict Global Storm (Pivotal Games, 2005), Borderlands (Gearbox Software, 2009), Left 4 Dead (Turtle Rock Studios, 2008), Killzone (Guerrilla Games, 2004) and Clive Barker’s Jericho (MercurySteam, 2007). Some games which offer a choice of character appear to combine diversity within the female choice, for example, Hybrid (Movietime, 1997), Rise of the Triad and Zero Tolerance all have an Asian ethnicity for their sole female avatar choice. Other ethnicities had to wait for female avatars to be available. Turok 3: Shadow of Oblivion (Acclaim Entertainment, 2000) allowed the player to choose a North American Indian female avatar. Timesplitters (Free Radical Design, 2000) had an African-American female avatar for one level. Left 4 Dead 2 (Valve, 2009) was the first single-player game, apart from the two mentioned above offering extensive avatar customization, that allows the player to choose an African-American female avatar for the entire game.

Portal (released 2007!) was the first game found where the player is forced to play an avatar that is not at least one of male and Caucasian. Given that female avatars were available as a choice from 1994, and the first game enforcing a female avatar was Alien Trilogy (Probe Entertainment, 1996), this seems to have taken designers an oddly long time.

Avatar Background

The primary gameplay action in a FPS is to shoot. It is unsurprising that the background of most avatars provides a reasonable explanation for their proficiency with firearms. Of the games surveyed, background information about the avatar could be determined for 475. Military and related backgrounds dominate (table 6).

Table 6. Avatar Background Distribution

Many of the categories are self-explanatory. Intelligence covers avatars working for spy agencies and other government intelligence services, for example in such titles as Goldeneye 007 (Rareware, 1997), The Operative: No One Lives Forever and the Secret Service series. Mercenary covers bounty hunters (such as Samus Aran from the Metroid series and Joanna Dark from the Perfect Dark series), the lone operators from S.T.A.L.K.E.R. and Borderlands and the bodyguards from Red Steel (Ubisoft Paris, 2006) and Shadow Warrior. Warrior and Magic-user are for those avatars trained in particular combat skills, but not from a regular military background. For example, the Hexen series (Raven Software, 1997), Heretic (Raven Software, 1994) and the Magic Carpet (Bullfrog Productions, 1994 to 1995) series. Gunslinger groups a number of avatars from games set in the American Wild West where the personal history of the avatar explains includes extensive experience in weapons. Rebels, such as from a number of Terminator games, have no formal military background but have been sufficiently involved in a guerrilla war to have considerable fighting skills. Hacker could be regarded as a subset of civilian or, in the case of HacX (Banjo Software, 1997) criminal. The Supernatural classification covers ZPC (GT Interactive Software, 1996), Psychotoxic (Nuclearvision Entertainment, 2004) and Requiem: Avenging Angel (Cyclone Studios, 1999), where the avatars are (respectively) a god, a half-angel and an angel. Even where the avatars have no formal military background, and are classified as civilians, other explanations for their competence in combat may be offered, such as in Nosferatu: The Wrath of Malachi (Idol FX, 2003) (a skilled swordsman), Will Rock (Saber Interactive, 2003) (granted powers by a Greek god) or the Redneck Rampage series (Xatrix Entertainment, 1997 to 1998), (the avatar’s cultural background includes particular familiarity with firearms). Even though “Civilian” is the second most numerous category the truly unprepared avatar is rare, with perhaps the most famous example being Gordon Freeman from the Half-Life series. Proportionally, the occurrence of the explicitly military background (the Military category in table 6) is remarkably consistent across platforms (table 7).

Table 7. Proportion of Avatars with Military background

In the nineteen years covered only the military background averages more than two examples per year. It is therefore difficulty to claim any significance in trends for the other categories. Most made relatively early appearances. For example civilian with Bram Stoker’s Dracula (TAG, 1993) and intelligence in Lethal Tender (Pie in the Sky Software, 1993).

Figure 12: Percentage of releases with avatars with military background

The percentage by year of titles with explicitly military avatar backgrounds is shown in figure 12. The figures for titles released only on computer show the same general trend over time. Releases on console only and titles released on both computers and console do not show any general trend. This is probably because they are relatively fewer in number. The same lack of titles prohibits definitive conclusions when the background data is compared to gender. For example, the mercenary category appears to have a relatively large number of female-only avatars, due to the Metroid and Perfect Dark series, but the numbers are so low that this can hardly be claimed to be meaningful.

Figure 13: Percentage of releases with Caucasian male avatars with military background

This trend is matched (as might be expected) by a particular subset, those avatars following directly in the steps of B.J. Blazkowicz. That is games which give the player no choice but to play avatars which are male, Caucasian and from a military background (figure 13, 197 games out of 442 where all of gender, race and background could be determined). The results for 1992 are B.J. himself. As this represents only two games out of the three found for 1992 (see figure 2), this anomalous result can be safely ignored. After that it is interesting that such a particular avatar type becomes more common over time. The graph shows variety from year to year, but the trend is unmistakably upwards. While more variety might have been expected as FPSs grow and mature, here we are seeing less.

Game Setting

FPSs allow players to decimate their enemies across a range of settings. Even in 1992 there was a choice between World War II (Wolfenstein 3D and Spear of Destiny) and the fantasy setting of The Catacomb Abyss. Setting information was found for 499 titles and the range is given in table 8.

Table 8. Game Setting Distribution

Placement within the categories used is occasionally subjective. Contemporary settings are those that are, more or less, chronologically and, for the most part, technologically, current day to when the game was produced. Games set a few years in the future, but with current day weapons and technology, such as Code of Honor 3: Desperate Measures (City Interactive, 2009) are classified as contemporary. It also includes games with particular technological advances that are secret and still under development (such as the genetic engineering in Far Cry (Crytek, 2004) and the cloning in the F.E.A.R. series). Near future covers those titles slightly to some years in the future and in which some reasonably widespread advances in technology are hypothesized. Science fiction covers games with extensive increases in technology over the current day and especially those which posit human possession of at least inter-planetary space travel. For example, Crysis (Crytek, 2007) is classified as Near Future, as the combat armour and associated technology appears to be in production (if limited distribution) and are not one-off prototypes, as for example some weapons are in other games. The Doom (id Software, 1993 to 2005) series is classified science fiction due to the inter-planetary travel to Mars. Some games, such as the Halo series are obviously science fiction, while Deus Ex is classified Near Future as the time frame and technologies posited are not far from current day. Fantasy represents games such as Hexen, Heretic and Zeno Clash (ACE Team, 2009) which have a fantasy setting with no obvious connection to the time line of the real world or have a pseudo-historical setting but such an emphasis on magic that it becomes an over-riding part of the setting. Examples of the latter include the Magic Carpet series and Arthur's Quest: Battle for the Kingdom (ValuSoft, 2002). World War II, World War I, the Vietnam War and the American Civil War are self-explanatory. The American West covers the late nineteenth century American frontier. Other Twentieth Century covers a range of games, from the very early twentieth century setting of Bram Stoker’s Dracula to the 1960’s setting of the No One Lives Forever series, that are scattered in small numbers over that time period. Other historical represents two games, Catechumen (N'Lightning Software Development, 2000) and Ominous Horizons: A Paladin's Calling (N'Lightning Software Development, 2001) which have much earlier historical settings then the other categories (Ancient Rome and the fifteenth century respectively).

The trends in some of the more numerous categories are presented in figures 14 and 15. World War II, World War I and the Vietnam War have been aggregated to give a larger sample. Figure 14 shows the percentage of releases for a year represented by each category. Figure 15 shows the total numbers in each category per year. Perhaps the most obvious trend is the continued rise of contemporary settings. After being only a small factor in the early years of the survey, their proportion rapidly rises through the late nineties, to a position of dominance that has yet to be challenged. There is a corresponding fall in games with a science fiction setting. In terms of quantity science fiction games have not decreased (in fact there were 47 such games in the first half of the survey and 66 in the second half) but their percentage contribution has fallen markedly. Fantasy based games have also fallen away, with a large period in the last decade with no such releases. One possible reason is the rise of fantasy-themed MMORPGs, although it might be expected that this would only influence the lack of multi-player fantasy-themed FPSs, not the single-player style as well. While near future games show a spike in the mid to late nineties this represents only 16 games in the period 1995 to 1997 and so would be difficult to term a significant result. They do show a relatively stable quantitative trend over time.

Figure 14: Percentage of releases in various settings

It would appear that Doom was more immediately influential on other designer’s choice of setting then its iD stablemates. Or if not the cause then it was at least part of a trend, with other science fiction games, such as Blake Stone: Aliens of Gold (JAM productions, 1993).

After the initial two B.J. Blazkowicz titles games set in the major wars of the twentieth century disappear until Nam (TNT Team, 1998). WWII returned with Hidden and Dangerous (Illusion Softworks, 1999), Medal of Honour (Dreamworks Interactive, 1999) and WWII GI (TNT Team, 1999). Given the initial success of Wolfenstein 3D it is at least noteworthy that no attempt was made to revisit the WWII setting for so long. Also worth noting is the correspondence between the contemporary and twentieth century wars percentages in figure 14 and the trend in figure 7. It is perhaps the rise of such titles that has kept the percentage of female avatars relatively low.

Figure 15: Total numbers of releases in various settings

The rise from the late nineties shown in figure 12 of a military background for avatars corresponds to a rise in a particular sub-genre - the contemporary military game. Where previously the titles presenting avatars with military backgrounds had historical or science fiction settings, beginning in the late nineties contemporary settings began to be used. While they have never been the majority (with exception of avatars with military backgrounds in 2008 and 2009), as shown in figure 16, they do constitute a significant sub-genre.

The appearance of titles based around current events (either closely or loosely), since 2001, such as the Terrorist Takedown 2: US Navy SEALs (City Interactive, 2008), Conflict: Denied ops (Pivotal Games, 2008), Combat: Task Force 121 (Direct Action Games, 2005), Elite Forces: Navy SEALS (Jarhead Games, 2002) and Kuma\War (Kuma Games, 2004) have had an impact on these figures. Comparable games are extremely rare in the early part of the period surveyed - in fact the result for 1993 and 1994 represent single games - Pathways into Darkness and Operation Body Count (Capstone Software, 1994).

Figure 16: Percentage of releases with avatars with military background and contemporary settings

Discussion

The modern FPS could be said to have originated with Wolfenstein 3D. A male Caucasian avatar, with a military background, the game played on an IBM PC compatible. Of the 566 games surveyed, 197 (or 35 percent) allow for such an avatar. The FPS has visited many places beyond a castle in WWII Germany. However, its origins continue to be influential. The majority of FPS can be played on a home computer (almost exclusively an IBM PC compatible), and only recently has it ceased to be that a majority can only be played on a home computer. Despite this, FPS have and continue to be available on a range of platforms, with the current generation of home video consoles playing an increasingly important role.

The particular combination of attributes pioneered by B.J. Blazkowicz is not a majority, though the avatars of most games reflect him in least one (if not two) of gender, race and background. 81 percent of titles require a player to play a male avatar, and this shows no signs of decreasing (if anything, the reverse is true). Similarly the games where a Caucasian avatar is required remain firmly in the majority and examination of the trend in this over time shows no noticeable decline. Titles such as Deus Ex: Invisible War show that this need not be the case, but its considerable flexibility in tailoring of the avatar in a single player game has seldom been followed. Multi-player games show a more even balance. However there is little in the way of requirements placed on the avatar by the setting and story in many of these games. While increased cost may make the developers of single player games unwilling to duplicate graphical and audio assets to represent a range of avatars, in multi-player games these considerations are much less important, leading to the question of why avatar choice is not more widely provided in those games at least.

Military and related backgrounds continue to be the almost exclusive providers of FPS avatars, although this is perhaps understandable given the nature of such games. That such a background is not absolutely necessary is shown by the small minority of games which give their avatar a different origin. Yet few games exploit such ideas, despite the overwhelming success of one example, the Half-Life series. This is an example of a wider point, that successful games do not always breed a significant number of followers. As well as Half-Life, another example that could be pointed to is Halo, which was not followed by a significant change in the number of science-fiction based titles released. This is not to say that there were not some clones, only that these games were not followed by greatly significant trends. Doom might be said to have created the dominance of science fiction in the early part of the period surveyed, but whether it was a trend-setter or merely the case that one background would dominate and some game had to be the first is difficult to say. It should be noted that Quake, for all its success, appeared at the time the science fiction genre started to decline. Sometimes popular games pickup up on a trend and reinforce it, for example WWII-based games had re-emerged some years before Battlefield 1942 (Digital Illusions, 2002) and the first Call of Duty (Infinity Ward, 2003).

Technological developments (understandably) and contemporary world events have also had an impact on the development of the FPS. As with any new technology that gains acceptance, initial introduction is followed by rapid growth. This can be seen in the rapid rise of games surveyed up to and including 1995. This growth then slows and stalls for over half a decade. The technology of FPSs evolved rapidly after their introduction. While the early market presented a simple entry point for start-up companies, the increasing sophistication introduced in the mid-90’s by games such as Quake resulted in a much more challenging environment for designers to produce a commercially successful product. It was only with the emergence of home consoles, primarily the 7th generation consoles, that growth in the number of FPSs coming to market resumed. This can be seen by comparing figures 2 and 3. The rise since 2001 in military themed titles with a contemporary setting is a clear from figure 15. That the real world events have had an impact is show by the basing of game son real world events, such as Kuma/War.

FPS avatars are predominantly male, Caucasian and from the military across all platforms (although not all characteristics in the same game). However, games designed for consoles show this uniformity of gender and ethnicity to a markedly lesser degrees than games designed solely for the PC. It might be that as the consoles are aimed at a wider market developers have attempted to make more inclusive design decisions. Interestingly the military background is more predominant in console-only titles than elsewhere, although this may be a product of the number of console titles rising at the same time as the military FPS with a contemporary setting.

The survey presented here has swept widely across the surface of the development of the FPS. More in-depth studies are required to fully understand the development of this game form. One investigation already being undertaken concerns the relationship between real world events and the number of military themed FPSs with a contemporary setting. Planned studies include more detailed examinations of the relationship between avatar ethnicity and background and a comparison between the single-player FPS designed for the home console market versus the overall trends revealed here. Other facets of this genre (or others) could be examined in the manner this paper has looked at platform and basic avatar characteristics. For example, the motivations of the avatar in pursuing the killing spree required in most FPS and the role and nature of non-player characters in these games.

The data presented here may also hopefully be used to give a context for studies which concentrate on a limited number of FPS titles, allowing a better understanding of their results. It may also provide a starting point for similar examinations of other genres and various game aspects that can be considered across genres. The individual numbers may appear overwhelming, but such is the nature of statistical survey. When a game or sub-genre is examined hopefully the results presented here will illuminate how the selected focus fits in the overall development of the FPS.

References

3D Realms. (1997). Shadow Warrior. [DOS,MacOS], USA: GT Interactive.

Acclaim Studios Austin. (2000). Turok 3: Shadow of Oblivion. [Nintendo 64, GBC], USA: Acclaim Entertainment.

Aarseth, E. (1999). Aporia and Epiphany in “Doom” and “The Speaking Clock”: The Temporality of Ergodic Art. In M. Ryan (Ed.), Cyberspace Textuality. Computer Technology and Literary Theory (pp. 31-42). Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

ACE Team. (2009). Zeno Clash. [Windows, Xbox360], USA: Valve Corporation.

Apogee Software. (1994). Rise of the Triad. [DOS], USA: Apogee Software.

Banjo Software. (1997). HacX. [DOS], USA: Banjo Software.

Barking Dog Studios. (2002). Global Operations. [Windows], USA: Crave Entertainment, Electronic Arts.

Bethesda. (2002). The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind. [Windows, Xbox], USA: Bethesda, played 2006.

BnB Software. (1995). Nerves of Steel. [DOS], USA: Merit Studios Inc.

Bullfrog Production. (1994). Magic Carpet. [DPS, PS, Saturn], USA: Electronic Arts.

Bungie. (1993). Pathways into Darkness. [Mac OS]. USA: Bungie.

Bungie. (1994). Marathon. [Mac OS]. USA: Bungie, played 2008.

Bungie. (1996). Marathon Infinity. [Mac OS], USA: Bungie.

Bungie. (2001). Halo: Combat Evolved. [Windows,Xbox,Xbox360,MacOS], USA: Microsoft Game Studios, played 17 June 2007.

Capstone Software. (1994). Operation Body Count. [DOS], USA: Capstone Software.

Cifaldi, F. (2006). Analysts: FPS 'Most Attractive' Genre for Publishers, Retrieved August 5, 2009 from http://gamasutra.com/php-bin/news_index.php?story=8241

City Interactive. (2008). Terrorist Takedown 2: US Navy SEALs. [Windows], Poland: City Interactive.

City Interactive. (2009). Code of Honor 3: Desperate Measures. [Windows], Poland: City Interactive, played August 2011.

Crytek. (2004). Far Cry. [Windows], USA: Ubisoft, played 13 March 2010.

Crytek. (2007). Crysis. [Windows], USA: Electronics Arts, played 25 May 2010.

Cyclone Studios. (1999). Requiem: Avenging Angel. [Windows], USA: 3DO, played 2002.

Digital Illusions CE, (2002). Battlefield 1942. [Windows,Macintosh], USA : Electronic Arts.

Digital Illusions CE. (2008). Mirror’s Edge. [Windows, PS3, Xbox360], USA : Electronic Arts.

Direct Action Games. (2005). Combat: Task Force 121. [Windows, Xbox], USA: Groove Games.

Dream on Studio. (2007). Touch the Dead. [Nintendo DS], USA: Eidos Interactive.

Dreamworks Interactive. (1999). Medal of Honour. [PS], USA: Electronic Arts.

Dynamix. (1998). Starsiege: Tribes. [Windows], USA: Sierra On-line.

Free Radical Design. (2000). Timesplitters. [PS2, Gamecube], USA: Eidos Interactive.

Gearbox Software. (2009). Borderlands. [Windows, Xbox360, PS3, MacOS], USA: 2K Games, played August 2011.

GSC Game World. (2007). S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl. [Windows], USA: THQ, played September 2011.

Guerrilla Games. (2004). Killzone. [PS2]. USA: SCEE

Hazan, A., Lipton H. & Glantz S. (1994). Popular films do not reflect current tobacco use. American Journal of Public Health, 84(6), 998-1000.

Hitchens, M. & Tychsen, A. (2008). The Many Faces of Roleplaying Games, The International Journal of Roleplaying Games, IJRP, Vol.1, #1. Retrieved November 24, 2010 from http://journalofroleplaying.org/

id Software. (1991). Catacomb 3-D. [DOS], USA: Softdisk

id Software. (1992). Spear of Destiny. [DOS], USA: Formgen Inc.

id Software. (1992). Wolfenstein 3D. [DOS etc], USA: Apogee Software

id Software. (1993). Doom. [DOS, etc], USA: id Software, played 2004.

id Software. (1996). Quake. [Windows, etc], USA: GT Interactive, played 1998.

id Software. (1997). Quake II. [Windows, etc]. USA: Activision.

Idol FX. (2003). Nosferatu: The Wrath of Malachi. [Windows], USA: iGames Publishing.

Illusion Softworks. (1999). Hidden and Dangerous. [Windows, Dreamcast, PS], USA: Take-Two Interactive. Played August 2006.

Inifnity Ward. (2003). Call of Duty. [Windows, Macintosh, PS3, Xbox 360, N-Gage], USA: Activision.

Ion Storm. (2000). Deus Ex. [Windows, MacOS, PS2], USA: Eidos Interactive, played 2007.

Ion Storm. (2003). Deus Ex: Invisible War. [Windows, Xbox], USA: Eidos Interactive, played 23 August 2009.

Irrational Games. (1999). System Shock 2. [Windows], USA: Electronic Arts, played, 22 November 2007.

Irrational Games. (2007). Bioshock. [Windows,Xbox360,PS3,MacOS], USA: 2K Games, played 23 November 2010.

JAM Productions. (1993). Blake Stone: Aliens of Gold. [DOS, Windows], USA: Apogee Software.

Jarhead Games. (2002). Elite Forces: Navy SEALS. [Windows], USA: Valusoft.

Klevjer, R. (2003). Gladiator, worker, operative: The hero of the first person shooter adventure. In Proceedings of Level Up. Digital Games Research conference, DIGRA 2003.

Klevjer, R. (2006). The Way of the Gun: The aesthetic of the single-player First Person Shooter , English version of La via della pistola. L’estetica dei first person shooter in single player. In M. Bittanti & S. Morris (Eds.) Doom. Giocare in prima persona, Milano Costa & Nolan. Retrieved August 5, 2009 from http://folk.uib.no/smkrk/docs/wayofthegun.pdf

Kromand, D. (2007). Avatar Categorization. In Proceedings of DiGRA2007: Situated Play. Tokyo, University of Tokyo, 400-406.

Kuma Games. (2004). Kuma/War. [Windows], USA; Kuma Games, played 12 July 2011.

MacTavish, A. (2002). Technological Pleasure: The Performance and Narrative of Technology in Half-Life and other High-Tech Computer Games. In G. King & T. Krzywinska (Eds.), ScreenPlay. Cinema/videogames/interfaces (pp. 33-49). London and New York: Wallflower Press.

Malliet, S. & de Meyer, G. (2005). The History of the Video Game. In J. Raessens, & J. Goldstein, J. (Eds.), Handbook of Computer Game studies (pp. 23-46), Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

MercurySteam. (2007). Clive Barker’s Jericho. [Windows, PS3, Xbox360], USA: Codemasters.

Monolith Productions. (2000). The Operative: No One Lives Forever. [Windows, MacOS, PS2], USA: Fox Interactive, played 2006.

Monolith Productions. (2005). F.E.A.R.. [Windows, PS3, Xbox360], USA: Vivendi Universal, played 18 July 2010.

Movietime. (1997). Hybrid. [PS], USA: SPS.

Nintendo Software Technology. (2006). Metroid Prime: Hunters. [Nintendo DS], USA: Nintendo.

N'Lightning Software Development. (2000). Catechumen. [Windows], USA, N'Lightning Software Development.

N'Lightning Software Development. (2001). Ominous Horizons: A Paladin's Calling. [Windows], USA, N'Lightning Software Development.

Nuclearvision. (2004). Psychotoxic. [Windows], Vidis Electronic Vertriebs GmbH, played 2005.

Pie in the Sky Software. (1993). Lethal Tender. [DOS], USA: Froggman.

Pinchbeck, D., Stevens, B. Van Laar, S., Hand, S. & Newman, K. (2006). Narrative, agency and observational behaviour in a first person shooter environment. In Proceedings of Narrative AI and Games Symposium 2006 (AISB '06). .Bristol, UK, 53-61.

Pinchbeck, D. (2007a). I remember Erebus: memory, story and immersion in first person shooters. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Games Research and Development (CyberGames '07). Manchester, UK, Manchester Metropolitan University, 121-129.

Pinchbeck, D. (2007b). Counting barrels in Quake 4: affordances and homodiegetic structures in FPS worlds. In Proceedings of DiGRA2007: Situated Play. Tokyo, University of Tokyo, 8-14.

Pivotal Games. (2005). Conflict: Global Storm. [Windows, PS2, Xbox], USA,: 2K Games.

Pivotal Games. (2008). Conflict: Denied ops. [Windows, Xbox360, PS3], USA: Eidos Interactive.

Probe Entertainment. (1996). Alien Trilogy. [DOS, Saturn, PS2], USA: Acclaim Entertainment.

Rare. (1997). Goldeneye 007. [Nintendo 64], USA: Nintendo.

Rare. (2000). Perfect Dark. [Nintendo 64], USA: Nintendo.

Rare. (2005). Perfect Dark Zero. [Xbox360], USA: Microsoft Game Studios.

Raven Software. (1994). Heretic. [DOS, MacOS], USA: id Software.

Raven Software. (1995). Hexen. [DOS, etc], USA: id Software.

Reality Bites. (1994). Sensory Overload [Mac OS]. USA: Reality Bites.

Remedy Entertainment. (2001). Max Payne. [Windows, PS2, Xbox, MAcOS, GBA, Xbox360], USA: Gathering of Developers, played 2007.

Retro Studios. (2002). Metroid Prime. [GameCube, Wii], USA: Nintendo, played 18 June 2010.

Retro Studios. (2004). Metroid Prime 2: Echoes. [GameCube, Wii], USA: Nintendo, played 3 August 2010.

Retro Studios. (2007). Metroid Prime 3: Corruption. [Wii], USA: Nintendo, played 21 September 2010.

Ritual Entertainment. (1998). SiN. [Windows, MacOS], USA: Activision, played 11 March 2010.

Rogue Entertainment. (1996). Strife. [DOS], USA: Velocity.

Saber Interactive (2003). Will Rock. [Windows], USA: Ubisoft, played 2007.

Saber Interactive. (2007). Timeshift. [Windows,PS3, Xbox360], USA: Sierra Entertainment.

Studio 3DO. (1995). Killing Time. [3DO, Windows, MacOS, Saturn], USA: Studio 3DO.

TAG. (1993). Bram Stoker’s Dracula. [DOS], USA, Psygnosis limited.

Team 17. (1996). Alien Breed 3D II: The Killing Grounds. [Amiga], USA: Ocean Software.

Techland. (2006). Call of Juarez. [Windows, Xbox360], USA: Ubisoft., played 2008.

Technopop. (1994). Zero Tolerance. [Mega Drive/Genesis], USA: Accolade.

TNT Team. (1999). WWII GI. [DOS], USA: GT Interactive Software.

Turtle Rock Studios. (2008). Left 4 Dead. [Windows, PS3, MacOS], USA: Valve Corporation.

Ubisoft Montreal. (2008). Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six: Vegas 2. [Windows, PS3, Xbox360], USA: Ubisoft.

Ubisoft Paris. (2006). Red Steel. [Wii], USA: Ubisoft.

Unique Development Studios. (1995). Substation. [Atari ST], Sweden: Unique Development Studios.

Valusoft. (2002). Arthur's Quest: Battle for the Kingdom. [Windows], USA: Valusoft.

Valve Corporation. (1998). Half-Life. [Windows,PS2], USA: Sierra Studios, played 2003.

Valve Corporation. (2004). Half-Life 2. [Windows, MacOS, PS3, Xbox, Xbox360], USA: Steam, played 27 September 2010.

Valve Corporation. (2007). Portal. [Windows, PS3, Xbox360], USA: Valve Corporation, played 11 September 2010.

Valve Corporation. (2009). Left 4 Dead 2. [Windows, Xbox360, MacOS], USA: Valve Corporation.

Xatrix Entertainment (1999). Redneck Rampage. [DOS, MacOS], USA: Interplay.

Zombie LLC. (1996). ZPC. [Windows, MacOS], USA : GT Interactive Software.