"Interactive Cinema" Is an Oxymoron, but May Not Always Be

by Kevin VealeAbstract

"Interactive Cinema" is a term that has been associated with videogames within historical media discourse, particularly since the early nineties due to the proliferation of CD-ROM technology. It is also a fundamental misnomer, since the processes of experiential engagement presented by the textual structures of videogames and cinema are mutually exclusive.

The experience of cinematic texts is defined, in part, by the audience's lack of ability to alter events unfolding within the film's diegesis. In comparison, the experience of videogames is tied inextricably to the player's investment and involvement within the game's textual diegesis, and within a Heideggerian world-of-concern.

However, there has been a recent development that suggests a bridge between these two structures: texts which are less defined by their ludic qualities than by a set structure - but where the affective qualities of the experience rely entirely on the direct involvement of the person engaging with the text. These are a storytelling form which are neither "played" or "watched," and it may be that "interactive cinema" is an appropriate way of conceptualising these experiences.

Key Words: Affect, alterbiography, ergodicity, interactive cinema, phenomenology, responsibility, tmesis, textual structure, world-of-concern

Introduction

Whenever forum discussion online deals with the subject of indie games, particularly those which qualify as part of the 'casual' games movement1, it's very common for someone to argue that "They're not games." Most often, this happens as an example of the oppositional framing between 'hardcore' and 'casual' games within player communities (Juul, 2010, p. 26), but in some cases the "they're not games," argument is not entirely groundless: these texts do not require the player to pass skill-based challenges to proceed, and are often functionally linear. So, if this subset of 'casual' games are not games, then what are they?

A way into analysing these texts and what sets them apart is to consider how their textual structures shape the experience of engaging with them. However, first it is necessary to establish the ways in which negotiating the textual structures of film and videogames distinguish the experiences of engaging with them, in order to provide a point of comparison. Doing so will require engaging with the problematic critical history of the concept of 'interactive cinema' within videogames discourse, and discussing how affect can be relevant as an analytical concept.

Having discussed some axis on which these texts can be considered, I present a series of case studies to argue that this subset of videogame texts qualify as something new. They may be less 'film-like' than many mainstream games with high-resolution graphics and cut-scenes, but the experience of engaging with them shares elements of engaging with cinema at the same time as they are distinguished by the direct, personal engagement of the player. As such, although 'interactive cinema' has historically been an oxymoron within videogame discourse, it is a productive—though imperfect—way of understanding this subset of texts and what sets them apart.

The Problem with "Interactive Cinema"

Videogames and cinema are both visually centered experiences2 and this shared trait came to dominate much of the discourse surrounding games, particularly in the eighties and early nineties when the proliferation of CD-ROM technology allowed for the inclusion of Full Motion Video (FMV) sequences into games. At the time, in-game graphics could not compete with cinema, so importing much higher resolution pre-rendered graphics and sound through CD technology was seen as a way of leaping past obstacles presented by the technological baseline. Star Wars: Rebel Assault (LucasArts, 1993b) was one of the flagships for the technology, providing players with a graphically detailed rail shooter with images, sounds and FMV from the Star Wars films. Both System Shock (Looking Glass Studios, 1994) and Day of the Tentacle (LucasArts, 1993a) were released in two versions, one with CD-ROM content and one without, so as to take advantage of audiences with different levels of hardware investment3. At the same time as games made use of the technology, the concept that games were demonstrating video quality graphics filtered out into wider discourse, and into the way games were being conceptualised. I argue it is no accident that some controversial forays into "adult" games within Western media occurred in the same timeframe, and using the same technology: Phantasmagoria (Williams, 1995) used blue screen and early motion capture technologies to present entirely "filmed" characters for a horror game which involved graphic violence and a rape scene, while Voyeur (Philips POV Entertainment Group, 1993) provided female nudity and sex scenes. Even games which were not inherently tied to filmed content, such as Wing Commander 3: Heart of the Tiger (Origin Systems, 1994) were promoted almost solely in terms of the actors being cast to act out FMV sequences within the game (Giovetti, 1995, p. 44).

The connection between games and cinema was hardly surprising or unreasonable: as Geoff King and Tanya Krzywinska have argued, to call a game "cinematic" is to praise it, and such associations occur frequently in advertising (King and Krzywinska, 2002a, p. 150). In the modern context, however, the situation is more complicated. A simple websearch for "games should be more like" retrieves far more articles and posts defending games from the argument that they should be more like film or literature than articles actually making such a claim. However, the tendency to suggest that games are not quite "there" yet is still something that surfaces in discourse, although such suggestions always attract lively debate. One of the most obvious recent examples was Roger Ebert's argument that games could never be art (Ebert, 2010b), a stance which Ebert later reframed into an open but unconvinced position in response to the discussion his comment prompted (Ebert, 2010a). Celia Pearce writes about games and conceptualisations of narrative in "Towards a Game Theory of Game," while also referencing prior criticism of games from film and literary scholars (Pearce, 2004b, pp. 143-144)—then has some of that literary criticism directly applied to her work in the response from Mark Bernstein (Bernstein, 2004 ; Pearce, 2004a). Lewis Pulsipher asks how to make games more like films in terms of their wide acceptance and ubiquity, and the core suggestion is to allow the people engaging with games the option of "watching" as much as "playing" (Pulsipher, 2009)—a move which emphasises the distinction between the forms of engagement involved in cinema and games, respectively.

It is that key difference in engagement which is why film and games are conceptually difficult to bridge. Celia Pearce argues that cut-scenes are fundamentally antithetical to the state of play due to different levels of activity required by engaging with films and games:

While often beautifully rendered (since typically they are not rendered in real time, they have the luxury of higher graphical quality), many players find cut-scenes to be egregiously interruptive to their play experience. It seems counterintuitive to use passivity as a reward for play. Many game players associate the idea of "narrative" with this type of enforced linearity, which is a throwback to cinema. (Pearce, 2004b, p. 148)

However, although Pearce's argument that cut-scenes are "interruptive to the play experience" is entirely legitimate, the issue is not one of relative activity of engagement, since engaging with film is not more passive than playing games (Howells, 2002, pp. 116-117 ; King and Krzywinska, 2002a, p. 146;). Instead, it is due to the fundamental experiential, phenomenological differences created by engaging with two completely antithetical textual structures. Jesper Juul has discussed the problems of reconciling videogames and cinema through the lens of temporality (Juul, 2001, 2004, 2005). He argues that cut-scenes and cinematic content creates a disruption by presenting events which unfold in the game, yet which are not part of the temporal framework of the player playing the game: they can be skipped because they exist in a temporal context disconnected from the player (Juul, 2005, pp. 146-147). Juul also argues that the "widescreen" format of black bars at the top and bottom of the screen through which some cut-scenes are presented through "... signifies 'cinema,' and also indicates the absence of interactivity," (Juul, 2004, p. 136).

It is this absence of interactivity which has been the core problem with the historical conceptualisation of "interactive cinema": the experience of cinema is so closely tied to an inability to intervene or participate within events unfolding in the text that the experience of the same film watched in a cinema or on a DVD at home is affectively distinctive, due to differences in the textual structures of the two different media forms. In the context of cinema, the audience has no capacity to engage with the text in a way that would modify how events unfold. We as the audience carry an awareness of the fact that we cannot interact with the film into our experience of it. If we anticipate dire events for the protagonists, there is nothing we can do to postpone the inevitable; the most we can do is look away. This awareness has specific consequences for the experience the audience has of the text due to the structure of cinema: I argue that our inability to engage with the structure of cinema is part of what informs how we can be held on the "edge of our seats," by cinematic experience.

In comparison, the experience of the same text at home on DVD is very different. We have more agency, in terms of our capacity to act. Janet Murray defines agency as "…the satisfying power to take meaningful action and see the results of our decisions and choices" (Murray, 1998, p. 126). If the film becomes too tense, the phone rings, we need a drink or to go to the bathroom, then we can engage with the structure of the text and pause it. The consequences which this ability has for our experience of the text are significant4. In the same way that we are aware the film will not stop as part of our experience within the cinema, our knowledge that the DVD allows us to negotiate the structure of the film colours our engagement with it. The DVD takes a film text and opens it significantly to at-home editing, where we can actually modify the order of events as they are encountered, and this change in the underlying textual structure alters the experience of the text5.

If moving the same film from the context of cinematic engagement to that of the DVD is sufficient to change the affective register of the experience, then the contextual difference between films and games must be proportionally larger: DVDs allow greater agency in engaging with filmic texts; videogames require it as a fundamental part of engaging with their textual structures. However, it is worth emphasising that this is not a distinction at the level of whether one textual form is more active or passive:

The videogame player has to respond to events in a manner that affects what happens on screen, something not usually demanded of readers of books or viewers of films... Games are, generally, much more demanding forms of audiovisual entertainment: popular, mainstream games require sustained work of a kind that is not usually associated with the experience of popular, mainstream cinema. It is possible to 'fail' games, or to be 'rejected' by them—to give up in frustration—if the player does not develop the skills demanded by a particular title, a fate that does not really have an equivalent in mainstream cinema (King and Krzywinska, 2002b, pp. 146-147).

Instead, the distinction relies on recognising that games require specific processes of engagement in order to negotiate their underlying structures. These involve both labour and decision-making, and produce an affective tone for the experiences which are entirely distinctive from that of engaging with film:

Herein lies an essential difference between games and cinema: games work with what we might call, borrowing from Nietzsche, the will to power—something far from diminished or blunted by a ludic context and that can easily or sometimes necessarily dominate over what Bernard Suits calls the "lusory attitude" (1990: 35) (in other words a "playful" approach to a task). It would not be wrong to argue that cinema is far better able to solicit a wide range of emotions than games, but I would suggest that games are very powerful machines for soliciting certain types of emotions and in particular a dynamic between frustration and elation—emotions which often sit alongside edgy wariness making for a perfect preparation for inducing horror-related affect such as suspense, trepidation and fear. In cinema, the viewer is unable to do anything to effect what happens on screen (even taking into account slippage in signifying conventions, closing eyes, going to the toilet or personal reading). In games, whatever you do, whether bungled or brilliant, affects the state of things on screen (Krzywinska, 2009, pp. 275-276).

Considering how the processes of engaging with different structures shapes the affective experience of texts helps to illustrate both why the historical conception of "interactive fiction" is implausible—or, as Bernard Perron argues, oxymoronic (Perron, 2003, p. 239)—and to reveal a form of text capable of producing a distinctive tenor of affective experience from either cinema or games.

Affective Phenomenologies

A central difficulty for discussions which involve comparisons between media forms with such different social/cultural contexts and disparate histories—critical and otherwise—is getting everyone on the same page. An element of the "interactive cinema" concept was motivated by an attempt to move away from the "game" moniker and its conceptual baggage, towards something capable of greater ambition—and a great deal of critical argument revolves around the implications of 'quality' that occur as soon as comparisons to "literature" are made. Witness the interchange between Bernstein and Pearce, which can be summarised as a rhetorical flourish asking what games offer artistic substance on merit with traditional media forms (Bernstein, 2004), and a retort that "... games are not the same thing as literature, and should be appreciated for what they are, not what they are not," (Pearce, 2004a).

Different forms of textual storytelling establish distinctive affective relationships with the people who engage with them, as a result of the processes of engagement required in order to negotiate the text. However, before we can discuss how and why the affective experience of videogames, cinema and the examples I argue may earn the title of "interactive cinema" function, we need to establish a framework for considering both the elements of textual structure that shape affective experience and affect itself.

The difficulty in comparing different subjective experiences lies in the extent to which experience is non-cognitive and happens, in some ways, where we are not watching. Or, to put it another way: to be self consciously aware of what you are feeling as you are feeling it is to alter the experience, precisely because you are making a conscious effort to do so. Affect is the term used to distinguish the non-cognitive component of subjective experience from the emotions, which we are more cognitively aware of and which thus present fewer obstacles to critical discussion: it is possible to specifically name an emotion and pin it down, whereas the affective tenor of an experience is by definition harder to label (Kavka, 2008, pp. 31-32).

Affect functions through an economy of cathexis, whereby an individual becomes invested in something, regardless of what that something may be. Affective investment occurs within a "Heideggerian world-of-concern," which Lars Nyre defines as a space shaped by human engagement, rather than an objective space (Nyre, 2007, p. 26). Nyre argues that an objective space is everything present within an environment, such as all of the furniture and fittings within a lecture theatre, whereas a world-of-concern is grounded in contextual relevance. In the context of a seminar, a world-of-concern would involve the speaker, the audience and the subject at hand while the majority of the room fittings would remain irrelevant or uninvolved.

In the context of a videogame, the player is invested in experiencing the game as a lived space with its own chain of sensible cause and effect relationships, and in engaging with the characters within the world-of-concern as legitimate entities in their own right. The importance of this investment is such that Laurie N. Taylor argues for two distinctive forms of immersion based on different subsets of player engagement. Diegetic immersion is where one can become "lost in a good book," remaining "unaware of the creation and relation of the elements within the text" (Taylor, 2002, p. 12). In comparison, Taylor also offers situated immersion, which is where the player is acting within the digital environment rather than upon it. Situated immersion describes the successful world-of-concern established when engaging with videogame texts: the world-of-concern is contextual, and what is affectively relevant to the player's experience (and thus what they are invested in) is acting within the diegetic space of the gameworld, rather than upon it. When situated immersion has been achieved, the person playing the game or exploring the digital environment is no longer policing the dividing line of the virtual, and is invested in being perceptually inside the diegesis of the game text.

Steven Poole uses the term incoherence to describe situations where an action undertaken within the diegetic space of the game environment does not have the consequences which would be expected if the same action were taken in the real world; such incoherence is an impediment to situated immersion (Poole, 2000, p. 95). The action can be as simple as your movement knocking a piece of stone into a river; if the stone sinks with a splash, this is a consequence that fits the contextual world-of-concern as a zone of legitimate cause and effect. On the other hand, if the stone sits unmoving on the surface of the "water," this will emphasise the mediated nature of the world-of-concern and arguably damage the investment the player has in the notion that they are occupying a legitimate space.

Situations which are instead structurally coherent introduce the feeling of responsibility into the experience, which itself reinforces situated immersion: the reason for this is that if you make a choice, then you are responsible for the consequences of that choice6. When a decision has a sensible outcome, the player is aware that their next decision will have a legitimate consequence, and their awareness becomes enfolded into the experience of decision-making. This feedback loop reinforces the contextual world-of-concern, and constructs the diegetic environment of the gameworld as a lived space where there are consistent rules, producing a logic of cause and effect. Responsibility is affectively powerful because within the contextual world-of-concern, being and feeling responsible for other characters is a significant component of forming relationships with them that matter to you. Structural incoherence makes it less likely that the player will feel responsibility within the contextual world-of-concern, because the rules of cause and effect are shown to be inconsistent and determined by something outside the player's control7.

System Shock 2 (Looking Glass Studios and Irrational Games, 1999) presents a good example of what a significant impact responsibility (and a lack of incoherence) within a science-fiction world-of-concern can have for the player's experience of the text. System Shock 2 is set within an experimental space ship which has been taken over by alien forces far from home. The game provides a detailed three-dimensional soundscape for the diegetic environment, in which you can typically hear enemies before seeing them. The key to situated immersion lies in the fact that the reverse is also true, which provides concrete consequences to any actions the player takes in exploring the environment. The result of this soundscape for the experience of the text is that every action is taken in the certain knowledge that you are being hunted8. In turn, this knowledge leads to two generalised responses within the world-of-concern, each informing two different "styles of play," possessed of their own affective register. If the player runs through the diegetic environment with their guns blazing, the noise will attract enemies from across the level; the dread fuelled by this style of play arises from the uncertainty of whether the player will run out of ammunition before they run out of enemies, within a context of constant threat. The alternative is to use stealth, and thus minimise the amount of noise produced in exploring the diegetic environment within the world-of-concern; the tension in this approach is drawn from the ongoing attempts to avoid detection and slip past the opposition, and bursts of frenetic conflict when those attempts fail. Both approaches are entirely appropriate for the science fiction/ horror genre of System Shock 2, but the experiences are affectively distinct.

Videogames present contextual worlds-of-concern which the player actively invests in, and the economies of cathexis and immersion at work mean that the person playing the game has a fundamentally different experience of the text than someone else who is watching the same game being played: someone who is an audience to gameplay has no agency, and no responsibility for how events unfold. There is less affective mediation inherent to the experience of videogame texts than would otherwise be provided by a protagonist within textual prose or filmic diegesis: feeling a character feeling is different than feeling yourself (Veale, 2011). It is the player who responds affectively to the awareness of being hunted within the diegesis of System Shock 2, not the character he/ she occupies, and not the protagonist of a novel or film whom the audience is expected to sympathise with.

Videogames also allow for the experience of what Christy Dena refers to as "eureka discourse" in the context of Alternate Reality Games (Dena, 2008, p. 53)—the aporias and epiphanies felt and experienced by the person negotiating the text, since it is his/ her choices which are directly relevant to overcoming obstacles.

As a result of the comparative absence of affective mediation involved with gameplay, the experience of games is distinct from the experience of either prose literature or film9. It is important to note that I am not arguing that games are better or more affectively powerful than film or literature, but certainly different, and with different experiential qualities as a result.

The texts which have historically been referred to as "interactive cinema" have alternated between the processes of engagement—and thus the affective experiences—of videogames and cinema, but are not experientially hybrids of the two10. Recently, I have encountered a series of texts which are not defined by their ludic qualities. These texts present focused, linear experiences which lack variation in what Gordon Calleja refers to as the alterbiography: the unscripted narrative generated during interaction with a game environment (Calleja, 2011, p. 124). The alterbiography includes all of the minute differences to the play experiences that can be found even in otherwise linear games (Calleja, 2011, p. 121), such as the variation in approaches to levels in Doom (id Software, 1993)—or the more significant experiential differences already discussed in terms of System Shock 2. In the case of the texts which arguably qualify as "interactive cinema," the alterbiography lacks much of this possible variation, producing experiences which are more likely to be consistent between different players, and thus a step closer to step closer to cinematic experience: despite the wide variety of cinematic: despite the wide variety of interpretations possible for a given film, it is commonly agreed that different members of the audience have at least watched the same film, where Calleja's concept of the alterbiography demonstrates the same is not reliably true of games.

However, unlike cinema, what makes the experiences of these texts distinctive is the player's lack of affective mediation, and the fact that s/ he is responsible for the outcomes of his/ her decisions within the text's world-of-concern. I argue that although "interactive cinema" as a term is not a perfect fit for these texts now, it is certainly more accurate than the term has been applied historically, and at the moment there is not a better alternative to describe what sets them apart11.

Experiential Storytelling

All of the texts which I argue qualify as legitimate "interactive cinema" are affectively distinct from each other, but they present variations on a theme regarding how the processes required to negotiate them shape the experience of each text. As such, the simplest approach to engaging with them is as case-studies12. (Be warned: spoilers are inevitable.)

Today I Die13 by Daniel Benmergui (Benmergui, 2009)

Figure 1 The game confronts you with this image, and challenges you to change it.

The experience of Today I Die does not depend on ludic engagement or reflexes, but on exploration and Dena's "eureka discourse" (Dena, 2008, p. 53), and there is no direct threat or possibility of "losing": the small area comprising the playable space provides players with a poem with places where words can be replaced, and any other objects on screen can be moved with the mouse. Replacing words in the poem changes the environment. This is a disarmingly simple concept, and from a purely functional perspective Today I Die is a puzzle that requires a set series of "moves" before providing an ending with two options to it. The power comes from seeing the world and the poem change each other, and the affective epiphanies that happen when you discover a way of introducing a new word into the diegesis. It is the affective dimension which provides depth for the experience: the player is personally responsible for the changes to the world and the poem, and his/ her frustration, exploration and delighted discovery matches that of the character in the game.

Today I Die begins in a meditative space while a girl sinks through dark water, seemingly tied to a rock; the poem at the top of the screen reads "dead world / full of shades / today I die." There is no urgency for either the character or the player, which allows for experimentation in moving the girl, the words, the predatory fish, and the jellyfish that drift across the screen. Switching the words in the poem changes the environment, but not in a way that provides new options. When the player introduces a new word into the equation by experimentation, the sinking girl opens her eyes to look at it, and the predatory fish attack. The excitement that something new has happened mixes instantly with the sudden threat that there are enemies seeking to thwart you, and the tension of figuring out exactly how to stop them happens at the same time as they attack. This pattern continues throughout Today I Die: when the poem begins to turn more hopeful, the attempts to thwart the change and the music become more intense; both the player and the girl are framed so that affectively, they have more to lose. Essentially, the person playing the game is placed in the same affective position as the central character, which shapes the experience of play. This is a trait shared by almost all of the texts under discussion, and as a result, someone watching the game being played would have a fundamentally different experience of the text than the person playing it—unlike what would happen if these texts were presented as films.

Small Worlds14 by David Schute (Shute, 2009)

Figure 2 Gradual Revelations

Small Worlds is a text of revelation rather than reflexes or threat. The graphics seem simple, but for each movement the player makes through the world with the tiny stick-figure protagonist, the overall viewpoint expands as if zooming proportionally outward—granting more perspective. The darkness falls away, giving the player more and more contextual information as s/ he explores, and meaning that the course of the experience of one of gradually putting the pieces together in unfamiliar environments. The game is verbally sparse, beginning with the phrase "There is too much noise," without any context. As the player explores the first environment, details of some form of ruined facility become clear, including four doors of different colours at the bottom of the structure, each of which takes you to a different world.

Each environment is very different, and there is nothing to threaten the player's explorations. The initial movements in each world—all of which begin essentially in darkness—are intended to give an impression of the environment. However, the experience rapidly evolves from the question of "What is this place?" to "What happened here?". The affective movement toward comprehension is elegant and melancholic, marked by music intended to counterpoint each environment. In particular, the music often sets up a particular tone and impression during the "What is this place?" stage, specifically so it can be undercut when comprehension of each world is reached15. As more of the worlds are completed and understood—generally a significant portion of each world needs to be covered to reach the exit—then the game becomes about comprehending the situation of the protagonist. Small Worlds is an affectively powerful experience precisely because it gives those exploring it time and space to put the pieces together on their own, and does not seek to hurry or to spell things out.

Norrland16 by Jonatan "Cactus" Söderström (Söderström, 2010)

Figure 3 The Colour Palette of Childhood Innocence

Where Small Worlds is delicate and melancholy, Norrland is existentially bleak. It presents a grey/ green world without variation or interest. The core character of the game is alone, and goes hunting in the wilderness with nothing but guns, booze and porn for company. The central action of the game is moving relentlessly towards the right of the screen, occasionally jumping obstacles, and reading translations of the character talking to himself. Any wildlife visible can be shot—sprays of gore being the only colour to the landscape. An interesting mechanic is that there is infinite ammunition, but you must reload the rifle, and do so manually: a methodical sequence of button presses works the gun's action until it is ready to fire. Doing so feels grounded in the game's world: rather than hitting "R" and delegating the details to the character on screen, you reload the rifle.

Quite deliberately, the only moments of excitement in the game's waking world is where an animal such as a bear or a deer attacks, providing a split second of life or death action. However, it is over all too quickly, and victory returns the player to the ongoing grind of trudging onward.

However, there are regular breaks where the central character shifts attention to pressing needs: annoying mosquitoes, bodily functions, urgent bouts of masturbation and sleep. All of these take the form of (often bizarre) minigames which are frequently unwinnable—or when the player is successful, winning achieves nothing. It is during sleep that Norrland begins to branch out, because the dreams that the protagonist has to deal with are entirely strange and very thematic: they are vivid, difficult and ultimately pointless.

None of Norrland's affective positioning is accidental. The game's waking world is grey and uninteresting, with nothing to do but brighten the world through murdering animals and risking death in doing so. This places the player in the affective context of someone for whom going drunkenly hunting by himself is the highlight of his life. Aside from killing things, the most joy they/ we get out of the world lies in satisfying primitive bodily needs. However, the implications of this affective framework are subtle. It is not immediately obvious that Norrland's "gag" is not simply creating a twisted and boring semi-game: it is in the dream sequences that the game's theme becomes more liminal, such as placing the player as a bird above a highway: flap too slowly, and you get run over; flap too fast and you get burned by the sun. There is no way out of each dream—at least, not until you die. The final dream takes the form of a conversation with a vast, shouting face, and you cannot proceed until you admit that you hate yourself, and that you want to die. Then the game finishes with an image of the protagonist hanging from a tree:

This ending turns Norrland on its head. You spend the game laughing and fumbling your way through the forest and the man's private urges, enduring disturbing dreams and listening to him talk to himself ("Beer is good!" "Time for a piss!" "Fucking mosquitos!"), but you never think of him as a person. How could you? The aim of the game seems to be blowing the heads off animals. But that's just it. If someone asked you what the game was while you were 75% of the way through Norrland, you'd probably say "Oh, it's just a funny game about a hunting trip." You, like the character, aren't aware of the extent of self-loathing and insecurity that's buried here, and when you discover it and the end it's like finding a shard of glass in your breakfast cereal (Smith, 2010).

Quintin Smith's point that players do not take the protagonist seriously is important: Norrland places us in an affectively coterminous position with a man who gets little joy out of life, who wanders out into the wilds to seek the fun he knows how to find, and who is presumably entertaining suicidal thoughts even before he leaves. However, although players share the same affective context because of how the experience is shaped, we are encouraged to be complacent and assume we do not have to take it seriously, and that everything is, at heart, fine. Then, after a series of increasingly disturbing dreams, the facade cracks so that both the protagonist and the player cannot help but confront what had been hidden—and then the protagonist kills himself in response to experiences that the player shared. Like Small Worlds, the experience would lack a great deal of its potency if the player were not in control of the pacing, and was not able to entertain the gradually growing realisation that all is not right with the game's protagonist. Norrland shares the cinematic trait of being entirely linear, to such an extent that there is no way to avoid the fate of the protagonist should we as players anticipate it, and yet it requires the lack of affective mediation in order to have the power it does.

But That Was [Yesterday]17 by Michael Molinari (Molinari, 2010)

Figure 4 Using Confusion and Eventual Comprehension as Storytelling Tools

In comparison to Norrland, But That Was [Yesterday] has equal affective power, yet is more uplifting. In this case, the affective experience of gradually learning how to negotiate the text is the whole experience: tutorial as comprehension. It begins with a stylised figure of a young man confronted by a bubbling black wall. From the wall comes a "speech bubble" with an arrow to the right, which happens to be the keyboard command to move in that direction. However, if you run into the wall, the protagonist is knocked to the ground amid a flurry of images that fade too fast to be fully understood. The game then presents a sequence of the same young man trudging through snow with a dog, confronted by the same wall. Following the wall's instruction to walk into it gets the protagonist knocked down again. The dog barks at you, providing a speech bubble with an "up" arrow—encouraging you to get up, at the same time as telling you how to do so. Whenever the player runs into the wall, s/ he is knocked down again. Turning away from the wall to focus on the dog drives the wall away.

But That Was [Yesterday] both frames the player as occupying an affectively coterminous position as the protagonist, and encourages us to identify with them—unlike Norrland. This is a text I have presented students with, and they have often written or spoken about the game's affectively powerful eureka moments: one student in particular said that she was finding the whole experience really frustrating, throwing herself against the wall again and again and it was not doing anything, so she looked at the dog and oh! The entire point is about learning how to work past obstacles, so what initially seems to be a tutorial is the affective core of the experience.

The rest of the game follows the same pattern, introducing new abilities at the same time as an affective context for the player to learn them in—which in turn provides clues to what the flashes of imagery associated with the black and threatening wall are. The point of the experience of dawning comprehension in But That Was [Yesterday] is that it is about learning to move past grief and inertia, with the player and protagonist reaching revelations and eureka moments at exactly the same time. Without the personal investment and lack of affective mediation presented by the textual context of playing But That Was [Yesterday], the experience would lose its power: the entire point is how we as players feel as we learn to negotiate the text, since that mirrors the affective movement of the protagonist.

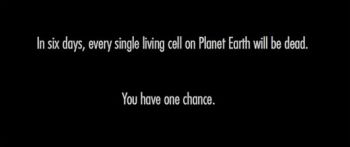

One Chance18 by Dean Moynihan (Moynihan, 2010)

Figure 5 The iconic opening screen...

Figure 6 ...and some of what you get to deal with.

An exception to the linear frameworks of other games being considered, One Chance is built around branching decisions, and as a result is more structurally ergodic than the other case studies (Aarseth, 1997, pp. 1-2), and will present a bigger variation in alterbiography19. The core premise of the experience is that the player takes the part of a scientist responsible for accidentally destroying all life on Earth, and who has six days to save the world. The player is repeatedly confronted with the question "What will you do?" and the game emphasises the consequences of every decision, again making the player and the protagonist affectively coterminous: I remember moments where a new option the game presented to me meant pangs of unwillingness to decide between trying to save the world for one more day, or taking my dying daughter to the park. In a move intended to emphasise the decisions the player made in negotiating the text—and by extension, their consequences—the game can only be played once: players who try to reload will be presented with the scene they reached at the game's conclusion, still reflecting the final outcome of the decisions he/ she made20.

The fact that One Chance is intended to be experienced once, as a stable series of decisions in one consistent alterbiography that the player remains responsible for, aligns it with an attempt to create an experience which—once established—is unchanging. In some ways, the experience is the process of creating something closer to a cinematic text, in that it is viewed in retrospect and cannot be easily altered. However, what is affectively central to the experience is the responsibility the player possesses for the outcome of the decisions they make—and his/her awareness of that responsibility when confronted with the next decision. The attempt to stabilise that experience—as opposed to the trial-and-error tendency to try remapping branching experiences within game culture—is primarily to emphasise the existing consequence of what the player chose to do, rather than allowing them the easy out of trying again.

Something New?

The traits that all of the texts in these case studies share are that their control systems are simple and make no assumptions about the skill-level of the person playing them; they are experientially linear (barring noted exceptions), meaning that multiple players are likely to have shared the same experience in negotiating the text; and they are experienced in a context of reduced affective mediation, so that the 'eureka moments,' triumphs and failures of negotiating the text are felt directly by the player.

Their linearity and the lack of variation to their alterbiography aligns them with cinematic texts in terms of how they are experienced, but a point of interest for me in writing this article is that I do not know how to refer to the people who are engaging with these case-study "interactive cinema" if not as players. Player involvement is a fundamental necessity to the affective experience of the texts, and in that context they can be memorably powerful. Certainly, these texts would have a very different affective tenor if they were "watched" rather than "played," since the audience would not be or feel responsible for the outcomes of decisions made in negotiating the text. As such, these texts qualify as being far closer to the processes of engagement which shape the experience of games than they are to that of cinema, and yet they are still distinctive enough to qualify as a subcategory of game experience.

Although it may be that "interactive cinema" is not the most appropriate term to describe these case studies and what they represent, I argue that at the very least, they represent an experientially distinctive form of storytelling that is not adequately described by either videogame or cinematic engagement in isolation. They are texts of nuance through responsibility, and yet they are uncomplicated to the point where there are no/few skills to be practiced, as would occur in a more ludic and game-like framework: they are powerful because of what is experienced, and how it is experienced, rather than the skill required to overcome the challenges involved in the journey.

Endnotes:

1 The shared traits associated with 'casual games' are that they are designed around being simple to learn, make no assumptions about the skill level of the people playing them, and present "shorter term rewards of beauty and distraction," (Scott Kim, quoted in Juul, 2010, pp. 25-26).

2 It's important to note here that there are two strands of scholarly enquiry which both apply 'interactive cinema' as a concept. The cinematic strand of criticism considers examples such as Kinoautomat (Činčera, Roháč and Svitáček, 1967), and Labyrinthe (Kroitor, Low and O'Connor, 1967), along with DVD-based films and experiments such as Soft Cinema (Manovich and Kratky, 2005) within film studies and film history discourses (Davenport, 2003 ; Hales, 2005 ; Lunenfeld, 2004 ; Marchessault, 2007). However, this article is primarily focused on engaging with the strand of criticism which develops through videogame discourses and theory, and where 'interactive cinema' as a term is used in a different sense than is applied in the cinematic strand of criticism. I consider the relationship between both the cinematic and videogame strands of criticism in my PhD and work which develops from it (Veale, 2012). For example, there are many productive analytical links that can be made between Kinoautomat—a film in which the collective responses of the audience on a pair of buttons selects between different outcomes for events—and games like Fahrenheit (Quantic Dream, 2005) or Heavy Rain (Quantic Dream, 2010). However, these discussions are beyond the scope of this article.

3 Day of the Tentacle used the opportunity for a clever marketing ploy, releasing the CD-ROM edition in unique Toblerone-style triangular boxes to emphasise that they held something new and intriguing.

4 Interestingly, Mizuko Ito raises a similar point in the context of videogames as part of her response to Juul's "Introduction to Game Time," (Ito, 2004). She comments that event-time and play-time can both be frozen by pausing single-player games if there's an interruption, but in many multiplayer or MMO games there is no such luxury—the game will carry on regardless (Ito, 2004, p. 132).

5 Marie-Laure Ryan argues that novels, films and games all exemplify different narrative 'modes' based on their structures of engagement, and arguably the shift as film moves from the context of cinema to that of a DVD would also qualify (Ryan, 2007, pp. 12-13).

6 Richard Rouse III argues that one of the core affective complexions of videogame experience is pride, as a result of having personal responsibility for the outcomes of your actions in horror games:

When someone asks you directly for help and you are able to solve their problem while saving them from certain death, a very real sense of accomplishment follows. Certainly, no other media provides that sort of direct satisfaction to the audience (Rouse III, 2009, p. 20).

7 Bernard Weiner argues that the assignment of responsibility requires the perception of human or personal agency (Weiner, 1995, pp. 7, 18, 257). Weiner also argues that anger communicates that someone 'should have' done or not done something, and that guilt and shame follow from a self-perception of responsibility. In comparison, sympathy is generated when others are not responsible for their unfortunate condition. Additionally, the more important or personally relevant the context, the greater the affective intensity. So, videogames interpellate players into positions of responsibility due to the agency they possess within contextual worlds-of-concern, and the players themselves invest in both their capacity to act upon the world of the game, and in the other characters sharing that context. As a result, players are also invested in how their actions affect other characters within the world-of-concern. Videogame players are situationally queued to be critical of the outcomes of their own actions: guilt for self-perceptions of responsibility when a negative outcome occurs as a result of something they felt could be avoided; anger for occasions where the blame is directed outwards, such as where failure occurs due to something seen as beyond the player's control, like a glitch in the game; sympathy for characters who suffer negative outcomes and are not responsible for causing them, since by definition it's the player who has agency.

8 I argue that the relationships we form with fictional characters are personally powerful because they matter and are of consequence within a Heideggerian world-of-concern: the affect and emotions prompted within the relationship are real, even if the subjects of the relationship themselves are not. The feelings produced by our engagement with fiction are not contained by our awareness that the characters we are attached to are fictional, and can inform our day-to-day awareness as much as any other investment or relationship we have, yet remain distinctive because of the hybridity of the experience. The relationship between the 'virtual-I' and the 'actual-I' is that they are coterminous: the 'actual-I' is your self, whereas the 'virtual-I' is a hybrid of your self and the text you are engaging with. The 'virtual-I' is distinct because the context of engaging with a world-of-concern modifies both your capacity to act and the feel of the experience, arguably modifying both your agency and your affect. However, nothing erases your awareness that what you are engaging with is fictional: in fact, the way in which the experience feels different because you are aware it is fictional highlights this contextual awareness, rather than eroding it. Along with this, the experiences of the 'virtual-I' are not compartmentalised: there is significant affective permeability between the 'actual-I' and the 'virtual-I' due to their coterminous existence, meaning that the experience does not spontaneously cease to be personally relevant and affectively potent when you stop reading the text, watching the movie, or playing the game. This dynamic is considered in greater depth than can be covered within the scope of this article in my PhD and work developed from it (Veale, 2012, pp. 39, 68-72).

9 Film and prose present textual experiences which are themselves affectively distinct as a result of the processes required to engage with them, but this is an issue beyond the scope of this article.

10 A great deal of strong critical work exists which engages with how cut-scenes impact the experience of game play, with some examples being: (Juul, 2001 ; Howells, 2002 ; King and Krzywinska, 2002 ; Klevjer, 2002 ; Perron, 2003 ; Juul, 2004 ; Pearce, 2004 ; King and Krzywinska, 2006 ; Ryan, 2007 ; Kirkland, 2009).

11 Enrique Dryere has suggested 'Interactive Digital Experience' as a term which should replace 'game,' (Dryere, 2009) but I am not certain it provides a useful point of distinction between what we know as games and other textual storytelling forms like Alternate Reality Games, or hypertext fictions. Since the examples I currently argue qualify closest fits for 'interactive cinema' lack the ludic element which distinguishes 'games,' perhaps 'Interactive Digital Experience' is a better fit for them—except that again, 'Interactive Digital Experience' is broad enough to include categories of text which are experientially distinct from them.

12 I'd like to thank the writers of Rock, Paper, Shotgun (rockpapershotgun.com), since it is their site that introduced me to every game under discussion in this article.

13 Available at: www.ludomancy.com/games/today.php

14 Available at: lackofbanjos.com/games/small-worlds/

15 The exception is the red world, which begins and ends in tender mourning.

16 Available at: cactusquid.blogspot.com/2010/08/norrland-gamma4-separate-downloads.html

17 Downloadable version available at: www.onemrbean.com/?p=190 Online version available at: www.onemrbean.com/?p=114

18 Available at: www.awkwardsilence.co.uk/OneChance.html

19 The central traits that Espen Aarseth associates with the 'nontrivial effort' of engaging with ergodic literature are processes of choice, discernment and decision-making. All videogames require ergodic engagement since the player is invariably deciding how to approach the situations they are confronted with, even if the decision is as simple as what gun to use. However, there are some game texts that present a higher level of structural ergodicity by including branching outcomes as a result of decisions made in negotiating the experience.

20 At least, played once per iteration of the game, since travelling to a different instance where it is hosted online or deleting the relevant save file will provide new opportunities. The affective impact remains significant, and certainly the emphasis on that outcome is clear even if players do migrate elsewhere to try again, since it presents an opportunity to create a new alterbiography rather than modifying the previous incarnation.

References

Aarseth, Espen J. (1997). Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Benmergui, Daniel. (2009). Today I Die. [Online Game]

Bernstein, Mark. (2004) "A Riposte to Celia Pearce." First Person: New Media As Story, Performance, and Game. Retrieved February 5, 2012 from

http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/firstperson/possible

Black Isle Studios. (1999). Planescape: Torment. Interplay Entertainment.

Calleja, Gordon. (2011). In-Game: From Immersion to Incorporation. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Činčera, Radúz, Ján Roháč, and Vladimír Svitáček. (1967). Kinoautomat. Czechoslovakia.

Davenport, Glorianna. (2003). "Putting the I in Idtv." in Manuel José Damásio (Ed.), Interactive Television Authoring and Production: Content Drives Technology, Technology Drives Content (pp. 143-54). COFAC.

Dena, Christy. (2008). "Emerging Participatory Culture Practices." Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 14/1, pp. 41-57.

Dryere, Enrique. (2009) "Gimme Five: The Branching Path of Future Games." Gamasutra. Retrieved February 5, 2012 from http://gamasutra.com/blogs/EnriqueDryere/20090917/3064/Gimme_Five_The_Branching_Path_of_Future_Games.php

Ebert, Roger. (2010a). "Okay, Kids, Play on My Lawn." Retrieved February 5, 2012 from http://blogs.suntimes.com/ebert/2010/07/okay_kids_play_on_my_lawn.html

__________. (2010b). "Video Games Can Never Be Art." Retrieved February 5, 2012 from http://blogs.suntimes.com/ebert/2010/04/video_games_can_never_be_art.html

Giovetti, Al. (1995). "Live the Ultimate Space Opera." Pulse, p. 44.

Hales, Chris. (2005). "Cinematic Interaction: From Kinoautomat to Cause and Effect." Digital Creativity 16/1, pp. 54-64.

Howells, Sacha A. (2002). "Watching a Game, Playing a Movie: When Media Collide." in Geoff King and Tanya Krzywinska (Eds.) Screenplay: Cinema/Videogames/Interfaces (pp. 110-21). London: Wallflower.

id Software. (1993). Doom. id Software & GT Interactive.

Ito, Mizuko. (2004). "Response." in Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Pat Harrigan (Eds.), First Person: New Media as Story, Performance, and Game (pp. 131-33). Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Juul, Jesper. (2001) "Games Telling Stories?" Game Studies 1/1. Retrieved February 5, 2012 from http://www.gamestudies.org/0101/juul-gts/

_________. (2004). "Introduction to Game Time." in Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Pat Harrigan (Eds.), First Person: New Media as Story, Performance, and Game (pp. 131-142). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

_________. (2005). Half-Real: Videogames between Real Rules and Fictional Worlds. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

_________. (2010). A Casual Revolution: Reinventing Video Games and Their Players. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Kavka, Misha. (2008). Reality Television, Affect and Intimacy Basingstoke [England] ; New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

King, Geoff, and Tanya Krzywinska. (2002a). "Computer Games/Cinema/Interfaces." in Frans Mäyrä (Ed.), Computer Games and Digital Cultures Conference. Tampere University Press.

________. (2002b). Screenplay: Cinema/Videogames/Interfaces. London: Wallflower.

________. (2006). "Film Studies and Digital Games." in Jason Rutter and Jo Bryce (Eds.) Understanding Digital Games (pp. 112-28). London ; Thousand Oaks ; New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Kirkland, Ewan. (2009). "Storytelling in Survival Horror Gaming." in Bernard Perron (Ed.) Horror Video Games: Essays on the Fusion of Fear and Play (pp. 62-78). Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co.

Klevjer, Rune. (2002). "In Defense of Cutscenes." in Frans Mäyrä (Ed.) Computer Game and Digital Cultures. Tampere University Press.

Kroitor, Roman, Colin Low, and Hugh O'Connor. (1967). Labyrinthe. Expo 67: National Film Board of Canada.

Krzywinska, Tanya. (2009). "Reanimating H.P. Lovecraft: The Ludic Paradox of Call of Cthulhu: Dark Corners of the Earth." in Bernard Perron (Ed.), Horror Video Games: Essays on the Fusion of Fear and Play (pp. 267-268). N.C.: McFarland & Co.

Looking Glass Studios. (1994). System Shock. Origin Systems.

Looking Glass Studios, and Irrational Games. (1999). System Shock 2. Electronic Arts.

LucasArts. (1993a). Day of the Tentacle. LucasArts.

________. (1993b). Star Wars: Rebel Assault. LucasArts.

Lunenfeld, Peter. "The Myths of Interactive Cinema." in Marie-Laure Ryan (Ed.) Narrative across Media: The Languages of Storytelling (pp. 377-89). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Manovich, Lev, and Andreas Kratky. (2005). Soft Cinema: Navigating the Database. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Marchessault, Janine. (2007). "Multi-Screens and Future Cinema: The Labyrinth Project at Expo 67." in Janine Marchessault and Susan Lord (Eds.) Fluid Screens, Expanded Cinema (pp. 29-51). Toronto ; Buffalo: University of Toronto Press.

Molinari, Michael. (2010). But That Was [Yesterday]. One Mr Bean.

Moynihan, Dean. (2010). One Chance. Awkward Silence.

Murray, Janet. (1998). Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Nyre, Lars. (2007). "What Happens When I Turn on the TV Set?" Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture 4/2 (pp. 24-35). Retrived February 5, 2012 from http://www.wmin.ac.uk/mad/pdf/WPCC-Vol4-No2-Lars_Nyre.pdf

Origin Systems. (1994). Wing Commander 3: Heart of the Tiger. Origin Systems.

Pearce, Celia. (2004a). "Celia Pearce Responds in Turn." in Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Pat Harrigan (Eds.), First Person: New Media as Story, Performance, and Game. Retrieved February 5 2012 from http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/firstperson/metric

___________. (2004b). "Toward a Game Theory of Game." in Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Pat Harrigan (Eds.), First Person: New Media as Story, Performance, and Game (pp.143-153). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Perron, Bernard. (2003). "From Gamers to Players and Gameplayers: The Example of Interactive Movies." in Bernard Perron and Mark J. P. Wolf (Eds.), The Video Game Theory Reader (pp. 237-258). New York: Routledge.

Philips POV Entertainment Group. (1993). Voyeur. Philips Interactive Media.

Poole, Steven. (2000). Trigger Happy: Videogames and the Entertainment Revolution. New York: Arcade Publishing.

Pulsipher, Lewis. (2009). "Are Games Too Much Like Work?" Gamasutra. Retrieved February 5, 2012 from http://www.gamasutra.com/php-bin/news_index.php?story=25122

Quantic Dream. (2005). Fahrenheit. Atari.

____________. (2010). Heavy Rain. [PlayStation 3]. Sony Computer Entertainment.

Rouse III, Richard. (2009). "Match Made in Hell: The Inevitable Success of the Horror Genre in Video Games." in Bernard Perron (Ed.), Horror Video Games: Essays on the Fusion of Fear and Play (pp. 15-25). Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co.

Ryan, Marie-Laure. (2007). "Beyond Ludus: Narrative, Videogames, and the Split Condition of Digital Textuality." in Barry Atkins and Tanya Krzywinska (Eds.), Videogame, Player, Text (pp. 8-28). Manchester, UK ; New York: Manchester University Press ; Palgrave.

Shute, David. (2009). Small Worlds. Lack of Banjos.

Smith, Quintin. (2010). "At the Steps of the Bone Hut: Norrland." Rock, Paper, Shotgun. Retrieved February 5, 2012 from http://www.rockpapershotgun.com/2010/11/30/at-the-steps-of-the-bone-hut-norrland/

Söderström, Jonatan "Cactus". (2010). Norrland. Cactusquid.

Taylor, Laurie N. (2002). "Videogames: Perspective, Point-of-View, and Immersion." Retrieved February 5, 2012 from http://etd.fcla.edu/UF/UFE1000166/taylor_l.pdf

Veale, Kevin. (2011). "Making Science-Fiction Personal: Videogames and Inter-Affective Storytelling." in Jordan J. Copeland (Ed.), The Projected and the Prophetic: Humanity in Cyberculture, Cyberspace & Science Fiction (pp. 41-48). Retrieved February 5, 2012 from https://www.interdisciplinarypress.net/my-cart/ebooks/ethos-and-modern-life/the-projected-and-prophetic

____________. (2012). "Comparing Stories: How Textual Structure Shapes Affective Experience in New Media." PhD, University of Auckland, Auckland. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2292/10347

Weiner, Bernard. (1995). Judgments of Responsibility: A Foundation for a Theory of Social Conduct. New York: Guilford Press.

Williams, Roberta. (1995). Phantasmagoria. Sierra Online.