“Take That, Bitches!” Refiguring Lara Croft in Feminist Game Narratives

by Esther MacCallum-StewartAbstract:

Since Lara first “bust” onto our screens in 1996 in Tomb Raider (Edios Interactive), she has been a focal point for critical debate surrounding the representation of the female protagonist and the gendered body in games. Nearly twenty years after her first appearance, the 2013 version of Tomb Raider (Crystal Dynamics) remakes Lara with a new body, a new author, and has sent her out towards a new generation of fans. In line with attempts by the games industry to provide a more appealing female protagonist, Lara has been significantly altered physically and in terms of her attitude, but what is perhaps most striking is the way that her narrative has also been redefined by a female writer, and then taken even further by a more gender-savvy fanbase willing to give Lara a second chance. This paper examines the 2013 iteration of Tomb Raider in the light of previous scholarship, arguing that despite, as Kirkland argues “The meaning of the controllable figure ‘Lara Croft’ within the Tomb Raider series is inseparable from the paratexts that surround it” (Kirkland, 2014), that critics have often used Lara’s sexualised appearance to unfairly dismiss the players who see her as an icon or those that have simply enjoyed playing with and through her for nearly 20 years. Critically, her body and her gender have been seen as indistinguishable, and this is used in turn to disenfranchise the experience of the player who controls her. I will also consider how new ways of consuming games -- most notably through webcasting playthroughs -- are working to change the ways in which gender is formulated in digital games. Here, games are reframed by the fan producers who overlay narratives on top of the existing text, reinterpreting it in ways that provide interesting new readings of how Lara is understood by her own players.

Keywords:

Game Studies, Players, Webcasting, YouTube, Tomb Raider, Feminism

Introduction: Growing up with Lara.

It was a checkered history, I guess. I loved the first game, I played the second, the Tomb Raider 3 launch was my first ever industry event but I sort of lost interest in the franchise.

(Pratchett in Kuchera, 2013)

Lara Croft has been a contentious figure since her first appearance in Tomb Raider in 1996. Although she is by no means the only female protagonist in digital games, having been superseded by characters like Metroid’s Samus (Nintendo, 1986) and appearing at the same time as Resident Evil’s Jill Valentine (Capcom, 1996), her appearance as the lead character of a blockbuster (AAA) game has always been noteworthy, and despite a long list of predecessors, she is often treated as virtually unique in the field of gaming. Analysis from both the media and academic perspectives has been applied heavily to Lara, and she is often the postergirl -- sometimes quite literally -- of a number of debates within gaming, again both formal and informal. The result of this is that Lara has remained a critically visible figure for nearly 20 years.

In From Barbie to Mortal Combat, edited by Cassell and Jenkins (2000), recognised as one of the first feminist texts about gaming, Lara is a frequently mentioned example. The responses of the authors towards her demonstrate an alarming bias, which seems to have gone unnoticed. Lara is bad; a negative role model played primarily by boys (not men), whose physical appearance outweighs any productive representations or her appropriation by female gamers. The complexities of playing and understanding Lara are largely ignored, despite specific examples within the text where female gamers express their affection for her. Lara is variously called “Female Enemy Number One” (Jones in Cassell and Jenkins, 2000, 338), “aggressive” (Subrahmnyam and Greenfield in Cassell and Jenkins, 2000, 59) and a dangerous role-model (Jones, in Cassell and Jenkins, 2000, 339). Tomb Raider is described as a “boy game” (Cassell and Jenkins, 2000, 35), and Jenkins admits at one point that he hates Lara (Jenkins in Cassell and Jenkins, 2000, 330). These comments are placed in the text despite contradictory examples of a female player who “loves” the game (interviews with Theresa Duncan and Monica Gesue, in Cassell and Jenkins, 2000, 190), a female player who uses Tomb Raider as an example of a “the best game” in order to browbeat a group of male players, (Jenkins, 2000, 329), and the continuing acknowledgement throughout of Lara’s commercial success (attributed, without corroboration, “almost entirely in terms of her erotic appeal to young male players”) (Cassell and Jenkins, 2000, 30). Helen Kennedy also quotes one of the authors as praising Lara as an empowering figure:

There was something refreshing about looking at the screen and seeing myself as a woman. Even if I was performing tasks that were a bit unrealistic… I still felt like, Hey, this is a representation of me, as myself, as a woman. In a game. How long have we waited for that?

(Douglas in Kennedy, 2002)i

What is so striking about these responses are the ways in which the authors directly refute Lara’s potential as a feminist icon because of her body. Throughout the book, the authors ignore or are ashamed of their responses to Lara, and work hard to negate any impact she might potentially have on the female player. Her appearance is used as a weapon against any meaningful influence her insertion in gaming culture might represent, and her huge popularity amongst gamers is dismissed as ultimately futile:

Croft’s popularity may represent the success of a female protagonist (albeit one conceived in terms of male visual pleasure), but she would seem to have done little to alter relations between girl gamers and the game industry.

(Cassell and Jenkins, 2000, 30).

Lara is constructed as a problem; even female players who identify with her are seen as somehow traitorous or too young to appreciate her negative positioning; upholding a barbarised representation of falsified femininity. The writers in From Barbie to Mortal Kombat laid the foundations for important feminist debates in gaming, but they also construct Lara as standing in opposition to it.

In 2002, two papers took up this debate and developed it. Helen Kennedy’s paper “Lara Croft: Feminist Icon or Cyberbimbo? On the Limits of Textual Analysis”, argues for more complex readings of Lara as a figure of sexual desire and as a playable entity. Kennedy argues that by adopting Lara as a figure largely played by males, her body transforms into a transgendered space, whilst also keeping her within the realms of male desire. Kennedy argues that Lara’s hypersexuality is negated by the male player, and although she intends to provide a rounded discussion of Lara, this inevitably dwells on the debates that have problematized her (because, as Kennedy points out, these are the ones that rested within predominant critical perspectives at the time). Kennedy’s examination of various feminist readings of Lara concludes that Tomb Raider provides too masculine a perspective, with Lara continuing to represent male desires; both sexually and those of the gamer “himself”:

If we are going to encourage more girls into the gaming culture then we need to encourage the production of a broader range of representations of femininity than those currently being offered. (Kennedy, 2002)

Whilst this is undoubtedly true, and this statement is still a keystone of feminist debate in Games Studies, Lara is constructed as an indicative sexual metonym for what is assumed to be a predominantly masculine arena of gaming. Attempts to assert her power as an archetypal “strong female character” are occluded by her positioning as solely a tool for the male gaze. She is stolen from the realms of female play, and her increasingly overt sexualisation is presented antithetically to that of the female gamer, who seems to be invisibly idealised -- a feminist who rejects Lara’s disproportionate frame out of principle and therefore refuses to play her. This representation is implicit in much writing about Lara; for example, Jen Bosler begins her review of Tomb Raider in 2013 by stating that “Chances are, when you think of negative, objectifying portrayals of women in video games, Lara Croft is the first image which pops into your mind” (Bosler, 2013), and Archie Bland argues that even with the rebooted Lara “her feminist credentials are as inflated as her chest used to be”

For Eidos, this became a self-fulfilling prophecy. As the game continued to produce sequels, the cyborg sexuality that Kennedy identifies so clearly in Lara increasingly removed her from realism, and Eidos used the “male player, male gaze” argument to justify distorting her body to extremes. The exclusion of the female player is endorsed throughout, via the assumption that women players are few and far between, and that Lara’s sexualisation is not for them. Later incarnations of Lara moved steadily towards this trait, privileging the male gaze / heteronormative player, and the rejection of her by gaming academics became more easily mapped onto Lara’s body, mannerisms and speech.

In the same year as Kennedy’s paper, Diane Carr also attempted to position Lara away from simply seeing her as a tool of anti-feminist representation. She engages with this discussion in her paper about the pleasures of playing Lara (2002), and also argues playfully that “Lara’s objectification jars against her role as a homicidal archaeologist” (Carr, 171). However, despite Carr’s vicarious enjoyment of adopting Lara as an avatar of self, her appreciation of Lara moves into more familiar cyborg territory when she situates her body alongside that of Ellen Ripley in the Alien films. Here, Lara becomes a site of gendered anxiety as she embodies multiple readings at once, as well as drawing attention to our own troubling visions of sexuality. Carr is clear that:

It would be deceptive and reductive to dismiss Lara as a figment of hyper-sexualised objectification. Perhaps the cycles suggested by Mulvey as being an inevitable aspect of gendered looking are being evoked, mobilised and exploited, only to be rendered ironic or subsequently compromised by Lara’s construction and expendability… Lara is watched, whilst she is being driven. Her physicality and gender invite objectification, yet she operates as perpetrating and penetrative subject within the narrative. This duality involves a certain delegation of agency between on- and off-screen positions. (175).

Despite this more favourable reading, Lara remains a problem. Now categorized as a site of gendered tension, Carr discusses the problematic nature of identifying her own status as a “girl-on-girl” inhabitant of this space (178). Carr is explicit that most of Lara’s issues arise from that fact that she is situated within a masculine space, and recognised in terms of her desirability for, and towards men.

“Look upwards and you will see a hole” The Invisible Woman.

Whenever anybody talks about a need for more female protagonists I say: “There’s a need for more female protagonists, but there’s a need for characters of different ethnicities, ages, sexual orientation, ability, et cetera.” We are very narrow when it comes to our characters.

But also you’ve got a situation where female characters do get scrutinized more than male characters do, and in some ways can be seen as holding a banner up for female characters. A lot gets heaped on their shoulders. Lara Croft gets a lot more scrutiny than Nathan Drake does, as a female. Nobody talks about how well Nathan Drake is representing men, or male characters in games.

(Pratchett in Lejacq, 2013)

Whilst feminists argued that Lara’s body and sexual positioning placed her in uncomfortable territory, gendering of Lara continues in papers that seek to disavow her body entirely. Espen Aarseth (2004) argues for a ludological approach that sees the gamer playing with Lara (sic) “despite” her appearance. His argument that she does not matter is not so much a statement that the gentlemen doth protest too much, but more an acknowledgement that looking at Lara and becoming aware of her as an atypical figure in gaming is inescapable. Aarseth argues that “when I play, I don’t even see her body, but see through it and past it” (Aarseth, 2004, 48), and yet this statement inescapably “notices” Lara. Here, it is the seeing in order to unsee that is important, as Aarseth chooses Lara to make this point, rather than a masculine or gender-neutral target. Aarseth’s argument would not have the same impact were it to contain the name of Max Payne, Bioshock Infinite’s Booker (Irrational Games 2013), or Trevor Philips from GTAV (Rockstar, 2013) (who spends a vast percentage of the game without a shirt on, often resetting to this default despite previous scenes where the player has chosen to clothe him) inserted instead. Drawing attention to Lara as immaterial simultaneously points to her irrefutable position as a woman already considered out of place. This is supported by the continuing attention given to female protagonists, who are still usually introduced in a fanfare of novelty, and often highly scrutinised for their suitability within the games industry. For example, it is common to read articles citing resistance to the idea of female leads (often alluding to a shadowy organisation of “higher-ups” who refute the commercial viability of such figures), and it has not been until recently that their numbers have significantly increased in characterisation as well as diversity (for example, Chell from Portal (Valve Corporation, 2007), Jodie in Beyond: Two Souls (Quantic Dream, 2013), Ellie from The Last of Us (Naughty Dog, 2013) and the forthcoming sequel to Mirror’s Edge (EA, 2014)). As an aside, the violent response to feminists in 2014 by members of the #gamergate hate group demonstrate just how discomforting the female body, or attempts to reclaim it, are seen by some gamers.

Although Aarseth argues that Lara does not matter, to many, she does. Since these early papers, much has been written on Lara that continues to problematize her, across a wide spread of media; both academic and journalistic (for example, Schleiner, 2001; Edge, 2008). As previously mentioned, Lara Croft is used as a case study in many Game Studies primers (King & Krzywinska, 2006; Dovey & Kennedy, 2006; Rutter & Bryce, 2006; Egenfeldt Nielsen et al., 2008), in order to encourage debates about gender and sexuality in gaming.

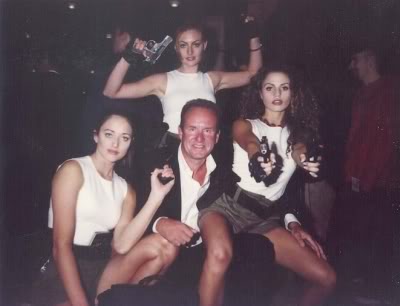

These largely negative discussions of Lara have been supported by her continuing dysmorphia in games until 2013, as well as other paratexts that present Lara throughout different media. The casting of Angelina Jolie in the two movie adaptations of Tomb Raider (2001, 2003) meant that each film focussed overtly on the male gaze (for example, via cinematic shots of Jolie climbing out of water, wearing skintight clothing or showering), and Jolie herself is a media figure with a highly sexualised profile. Rather like Lara, Jolie’s breasts and body were artificially altered for the audience; and it is obvious in some scenes that her tattoos have been airbrushed away. Her body in the film becomes as pixelated as that in the games, encouraging the idea that Lara is a false [sic] icon of male desire. Similarly, the appearance of Lara in booth babe form at many Eidos gatherings, often played by models such as Jordan (a UK model and D celebrity famous for her breast enhancements and appearance in various soft porn photography shoots), as well as Lara’s front cover appearance in Men’s Magazine GQ in 1997, encouraged the idea that Lara should be seen as an object of desire, rather than a pioneering avatar of games culture. Finally, gaming journalism has also contributed to this portrayal of Lara -- Bernstein’s article “Two Decades of Breathtakingly Sexist Writing About Tomb Raider” recaps some of the mysognyist writing about her which includes describing her as “Indiana Jones with breasts” (Zydrko, 1999), and again, stressing her oppositional position “Tomb Raider is bound to stir up lots of trouble with the feminists” (IGN, 1996).

Fig 1. Ian Livingstone (CEO of Eidos Interactive) poses with several Lara Crofts (including the actress Jordan), circa 2000.

Going a Bit Lara.

Despite my never having played any of the games, I became eternally interested in sexism and the female presence in the video game industry specifically because of Lara’s disproportionate physique. She was the one I pointed to whenever I argued that video game creators didn’t present women as anything more than sex objects.

(Brouwer, 2013)

Whilst the critical and feminist readings of Lara are undeniable, they have always disturbed me. As a long term scholar and player of games, I have seen many discussions of Lara Croft. She is a common example in the “gender and games” section of any undergraduate course, and yet these classes lack nuanced debate. There is a conspicuous absence of unpicking or developing of the complex, conflicted positions that Kennedy, Carr, Aarseth and Cassell and Jenkins present. Lara remains bad, forced to enact a binary representation of sex and gender politics within gaming that has little sophistication. Arguments of causality and the ghost of Andrea Dworkin hover close to the surface -- does playing Lara make you a bad feminist for liking her, and are all male players raping her by assuming her identity? It is not only not cool to like Lara, it is politically offensive to do so. Rather like Brouwer, it is better not to watch Lara, in order to keep her within the confines of nothing more than a “sex object”. The reductive nature of this argument seems so obvious, and yet it never arises. Is it so bad to transgender her, as Kennedy suggests (particularly since our discussions of transgendering have become more complex in the years since Lara has appeared)? Surely players have more intelligence and confidence in their sexuality, and an ability to see Lara as simply a ludic avatar, as Jenkins and Aarseth suggest? Are there some pleasures to playing with Lara that are not transgressive, or which allow players to appropriate gendered play for their own ends? How do LGBTQ players respond to her, if at all? Positioning Lara as our enemy -- all genders, all sexualities -- seems disturbingly like placing her as a moral and sexual compass that refutes sexuality, conflates it with gender, and denies the potential nuances of a truly gendered investigative response.

There is a second point, close to this one. I have an abiding affection for Lara, both as a subject of critical debate and a gaming icon. Lara is an irrefutable part of my gaming life and has been since her inception in 1999, and when I play her, I revel in her strength and abilities, her wisecracks and her cheesy lines, as well as appreciating that she is not particularly realistic. In this respect, she is much the same as every other gaming character I have ever adopted. I frequently see through her (as Aarseth suggests I do), in order to get on with the serious business of playing Tomb Raider itself, and sometimes simply revel in her disproportionate and often amusing behaviour (for example, the dreadful “international woman of mystery” introductory scene for the first game, the moment when she tanks her irritating butler into the larder and shuts him in during Tomb Raider II (Core Design, 1997)), or more embarrassingly, the walkthrough that once told me to “look up, and you will see a hole”, only to find myself staring between her legs instead of looking at the platform above. Crucially, I am not alone.

Examining early accounts of playing Lara, as well as those recounted by existing gamers, reveals that despite her appearance, Lara was seen in a much more positive light by players themselves. Players revelled in her difference, including her femininity and sometimes, but not always, her sexuality. Their writing shows an appreciation of the tensions she exhibits, but it also celebrates her as a proactive member of the gaming canon:

There’s no getting around it: Lara Croft, the star of the Tomb Raider series, is a genuine action hero with ginormous breasts, which has made her both a symbol of female self-empowerment and an object of sexual desire. … Since her inception in 1996, Lara has been an action heroine who explores, solves puzzles, and yes, even kills. But she’s done so with over-endowed mammary glands and no hint of a good support bra. As I said in my intro, although she has been recognized as a symbol of female power -- after all, she gets the job done -- she has also been viewed as an object of male pleasure.

(Pinchefsky, 2013)

Before Tomb Raider, I had absolutely no interest in archaeology or history whatsoever. I was 17 back then. History was always a bore for me back in school. … But after playing Tomb Raider: Legend, Anniversary and Underworld, it made me want to study a bit more. Somehow, this made-up girl made me want to know about history a little bit more.

(Shanthini, 2013)

As one of the only consistent female characters in gaming history, Lara was, and remains, a popular and iconic figure. These accounts also suggest that affection for her is an enduring element of Tomb Raider’s play experience. As Becky Chambers argues, Lara often appeared to them at a key point in their gaming lives; “no game had given me such a visceral sense of adventure and danger. And no story I had seen -- movies, books, or otherwise -- had ever told me that a woman was allowed to be cast in such a role” (Chambers, 2013). Denying the part that Lara has played in the experience of female gamers by resisting her appeal is therefore a contrary and troubling moment in gaming academia.

2013: Crystal Dynamics.

Tomb Raider, the 2013 version of the game, is a reboot depicting Lara Croft’s first adventure. In previous tellings, Lara’s original backstory has remained relatively blank, subject to inference by the player via a few brief cut-scenes or tutorials. We know Lara is rich (a peer of the realm who rather curiously lives in Wimbledon, London), and that she is an orphan. The introduction to the first game suggests that she is famous for her exploratory powers and possibly also greedy for more. She has a bad relationship with a mentor called Werner Von Croy, but we know this because it leads to him becoming the villain of Tomb Raider II. Lara lives in a palatial English mansion, where she practises aerobics on an alarmingly complex assault course and terrorises her butler. Otherwise, she travels the globe and explores tombs, especially ones containing vicious dogs, occult monsters and rooms that can only be exited by pushing blocks around.

Tomb Raider (2013) provides the gamer with a detailed origin story. After funding an expedition to the lost city of Yamatai, Lara and the crew of The Endurance are shipwrecked on a mysterious island in the Dragon’s Triangle, east of Japan. Lara is separated from everyone, including her friend Sam. She awakes on the island and is almost immediately knocked out. When she comes round, she is upside down and trussed up. Her escape takes her past an underground site of ritual sacrifice and a series of dead bodies. Once outside, and now quite badly wounded, she must start to learn to survive on her own. This includes a gradual escalation in violent behaviour -- first Lara kills a deer, then a person, and then a lot of people -- as well as her realisation that the island is in the grip of occult forces (in which she does not initially believe). As the story develops, Lara’s character also changes from the girl pleading for help on her radio (“Sam? Roth? Can anyone hear me?”), to a woman fully in charge of her team (all of whom have needed saving from hostile forces at least once) who heads into the final tomb alone in order to rescue Sam, who she has discovered is a distant relation and surrogate sacrifice for the ancient ruler of Yamatai; Queen Himiko.

The new game allowed Crystal Dynamics / Square Enix to rework Lara in a number of ways. She is introduced to the player as a more complex, emotive character, rather than a gun-toting action heroine. Her emotional and physical learning takes place throughout the game, rather than simply during the early tutorial stages. Extensive dialogue and a supporting cast of other characters provide a rich narrative, in which short cut scenes, personal meditations and discoveries by Lara and the environment itself link the action to a complex plot. Finally, Lara’s body has significantly changed. Whereas prior Lara was pneumatic and unrealistic, the new Lara is modelled on actresses Camilla Luddington (body and voice), and Megan Farquhar (face). Her body is now slim and athletic, easily damaged or dirtied by the actions she performs. She does not do handstands on the edge of precipices, or swallow dive into waterfalls; instead she scrambles over ridges and screams in alarm as she plummets through the water feet first. Her breasts have deflated to a normal size and have accurate gravitational abilities. Her face is emotive and often distressed, frequently accompanied by dialogue where she expresses self-doubt, encourages herself through short monologues, “come on, you can do this!” or is relieved to be out of danger. The arrogant action-heroine with biologically impossible proportions has been replaced by a young, fit twenty-something with a lot of money and grand aspirations, but not very much knowledge.

There is also a considerable difference in gameplay within the new Tomb Raider. New Lara is very much a product of her gaming time, and as such, occupies a substantively different world than her predecessor. Most notably, tombs are almost treated as asides in the larger, more open space that is Yamatai, which is a varied location dominated by locations situated outside: cliffs and mountaintops; villages and shanty towns. The geography is coordinated with more cinematic movement through it; at one point Lara scales a radio mast in order to send a signal and gets a bird’s-eye view of the island as the (game) camera swoops around her; in another she has to flee a crashing aeroplane by leaping across collapsing buildings. Puzzles where she pushes blocks together or activates switches to open secret areas and change the landscape are scarce; instead she traverses spaces using rope ladders and scales walls with her ice pick. On the same note, Lara has a variety of weapons, eschewing the two pistols in thigh holsters. Her primary weapon is a bow, and she can use the ice pick in conflict in some particularly gristly ways. Depending on the players’ choices, these weapons and other abilities like sneaking, are upgraded via a talent tree; so they player can considerably vary what type of Lara they play -- violent and hands on, or more wary and elusive. This combines to give the player more of a sense of Lara as a physical entity; her deaths, in particular, lack the rather comedic note of earlier, and are instead visceral and unpleasant. This combines to give the player a sense of Lara as a person within a more real landscape -- whereas early games often had a rather ethereal sense to each level; here Lara crosses and recrosses a much more tangible space.

Playing with Lara.

At this point a slight digression is required. This paper is not an apologist for Lara’s body. Lara is to-be-looked-at, and early versions of her avatar were specifically designed to appeal to young male audiences. Her new avatar has pert breasts and wears a tight t-shirt. She is still a sexualised character; albeit with a slightly broader sexual appeal. However, it seems hugely counterproductive to continue with this critique. Lara is, after all, one of many central protagonists in the AAA domain who are created in an idealised form. Despite her early incarnation on paper as a Hispanic Laura Cruz, she is white and of average height. After various re-imaginings where she had become disproportionately formed, Lara’s 2013 body is slender but athletic. She has a dusting of freckles and smears of dirt, but she is still attractive in a very normative manner. Her face is symmetrical and she does not have any cellulite. She is fit and muscular without overstepping current ideals of athletic womanhood. Yet it seems horribly unfair, not to mention counterproductive, to on-going analysis of gaming bodies, sexuality and gendered representation, to still hold this physicality against her. Gaming is a genre where dysmorphia is rife across all genders, and where vastly overinflated male bodies contend with offensive stereotypes of perceived Otherness, including race, gender, ableism, mental ability and sexuality.

Whilst the representation of the body in games is vastly complex, Lara’s position within this argument has hitherto disempowered both her and the players who engage with her. The critics who have examined her seem unable to look past this physicality, and despite Aarseth’s famous statement that Lara’s appearance is immaterial, it seems that critical work has not only failed to move beyond this, but has deliberately obfuscated the accounts and testimony of fans who have grown up and appreciated her.

In Tomb Raider, Lara Croft is the only avatar that the player controls. This is not uncommon -- we are used to adventure games having one central protagonist. Arguably, then, the players’ lack of choice takes any gendering out of their hands -- they have no option but to play Lara, and thus her gender is not an optional decision (rather like Aarseth suggests, her body does not matter, but for a slightly different reason). Players are used to this lack of choice and it has only recently become an option in adventure games, where graphical capability is limited. We do not expect an alternative to Joel in The Last of Us (Naughty Dog, 2013), or Batman in Batman: Arkham Asylum (Warner Brothers, 2011), and thus it is somewhat pleasing when we become Ellie or Catwoman. Of course, we are aware of the gender disparity, but to many players, being Lara as a default choice is no more different or aberrant than turning on a game and deciding to play as the Orc rather than the Night Elf. As a corollary to this, considerable evidence suggests that players (especially male ones) will happily cross-gender, and do so for a variety of reasons that have little to do with sexuality, appropriation or gender preference (Yee, 2006; MacCallum-Stewart, 2008; Lou et al., 2013).

Critically, then, regarding Lara’s body as a site of tension provides a disservice to gamers and their perception of self as other/avatar. In engaging with this debate we seem to be straying alarmingly close to those of causality. Playing Lara does not “make” me anything; including a bad feminist. I do not reject players who might wish to use her body as exploration, but to conceptualise all of them as doing so (especially when the player has no choice) is to refuse them both more and less complex readings. It assumes that players fixate on Lara’s body, and that alone, as well as disallowing the avatar its own multiple readings at different points in the game. To assume Lara has only one significant meaning in the game is to detract from her multiplicity. Lara can be tool, icon and avatar; moving through a series of different ludic and paidic stances as she is played; yet this is the role that any avatar must maintain in order to provide a satisfying play experience. As Kirkland argues when discussing the adoption of an avatar in the game Haunting Ground (Capcom, 2005):

The avatar’s nature is multiple rather than singular, and varied rather than uniform. This produces different subjective positions, and different experiences of embodiment, according to the body of the avatar and the body of the user. When playing Haunting Ground I am neither the cinema spectator of Mulvey’s paradigm, nor the dispassionate gamer of the ludological model, nor the immersed and re-embodied player described by Dovey and Kennedy, nor the fusion of machine and man implicit in Haraway’s cyborg. And yet playing the game involves moving between a partial and combined engagement with all these modes of participation and interaction.

(Kirkland, 2014)

With this in mind, it is also important to realise that many gamers today have grown up with Lara as an integral part of their gaming iconography. She is a familiar and relatively stable figure within gaming culture. New games are released on a regular basis, and there are high expectations for a Tomb Raider game. Despite this, both Tomb Raider: Underworld (Crystal Dynamics, 2008) and Tomb Raider: The Guardian of Light (Crystal Dynamics, 2010) were seen as rather tired, contrived re-imaginings of the franchise, as well as lacking in good core gameplay and style. Christian Schmidt called Tomb Raider: Underworld “depressing” and (2008) and Tomb Raider: The Guardian of Light had several issues with the controls (Metacritic, 2010). It is perhaps because of their established reputation that Crystal Dynamics were able to revive the franchise after such a series of commercial failures -- without the popularity of Lara herself, the series would potentially have been confined to gaming history.

Gaming history itself has worked against Lara. In the 1990s, gaming did indeed comprise a majority corpus of male players. By extension, this means that all games were predominantly played by males, so using this detail in order to reject Lara’s use by them is somewhat disingenuous. However, to portray all of these men as heteronormative, misogynist neanderthals, slobbering for the next shot of a breast, is incredibly offensive, not to mention sexist and disrespectful. It is unfair and almost certainly incorrect to claim that all of them lacked sufficient liberation to see Lara as anything other than a cyber bimbo, or that they all intentionally appropriated her gender when playing. For many, being able to play as a woman was as refreshing as it was for the many invisible members of Lara’s female audience.

Furthermore, the prevalence of male players at this point in gaming history does not mean that female players were not present or that they rejected Lara. The authors of From Barbie to Mortal Kombat find these women -- women who say it is a pleasure to play Lara and that she is a real heroine -- and then they reject them. Players like Hannah Rutherford of the Yogscast (see below) grew up with Lara. She was not only a relative constant in their gaming lives, but, as critics are at pains to point out, she was a female protagonist in a male world. Being able to look beyond Lara’s superficial gratuity, and see her as a relatively under-represented element of gaming culture was an essential part of recognising her role in gaming culture and development.

The Reinvention of Tomb Raider.

I’ve had an up-and-down relationship with Lara over the years. I played the first game, in fact [my] dad did and spoilt the bit with the T-Rex but it was still awesome. Then I felt she’d become reduced to a pair of boobs, a pair of pistols and a hair plait.

She became bigger than the games and was over-sexualised. I’m fairly used to that in games but it gave the impression that “ladies, this isn’t for you” and yet she was very popular with female gamers.

The chance to get my hands on her, so to speak, gave me the chance to make a difference.

(Pratchett in Polo, 2013)

When the Tomb Raider reboot was announced, publicity of the game was at pains to point out that Lara was new and improved in terms of gameplay as well as updated for a modern gamer. Core to virtually every press release by Crystal Dynamics was the news that Tomb Raider was going to be written by Rhianna Pratchett. Pratchett’s reputation for troubleshooting game scripts, as well as her prior work on Mirror’s Edge (EA, 2008) and Bioshock Infinite meant that she was a well respected member of the gaming community, as well as, of course, a woman. By inference, therefore, Crystal Dynamics strongly suggested to their players that Tomb Raider had undergone an ideological change as well as a ludic one.

Tomb Raider was released during a period when gender in gaming was becoming an increasingly high profile issue. The demographic of players has changed significantly in the last few years, with studies showing that gender parity in gaming is becoming increasingly common (ESA, 2013). More women were becoming visible or entering the developmental side of gaming, with gaming companies undertaking an almost universal push to end some of the more distasteful or misogynist elements of what had been a traditionally male-orientated industry. On both counts, tensions had arisen; the first questioning the authenticity of the female gamer, and the second largely related to continued inequality and sexism within the games industry itself. Tomb Raider and Pratchett appeared to be a focal point for these issues, suggesting as they did that the AAA segment of the industry should be producing games for all genders, and involve women at all levels of production. Rebranding Lara as a feminist icon also meant that the lucrative area of the female gamer was directly addressed as a target audience.

Pratchett herself was interviewed multiple times about Tomb Raider; at conventions, award ceremonies and in both the gaming and mainstream press. Throughout, she is keen to frame herself as a scriptwriter rather than drawing attention to her gender.

Pratchett’s work is interesting in itself. When Tomb Raider was initially announced, the decision to show a male avatar apparently molesting Croft in the first trailer led to considerable protests about the potential contents of the game narrative from a community already sensitive to frequent inappropriate representations of women in games. Complaints that Lara was being reconstructed as a weak victim seemed to be supported by a trailer apparently demonstrating that Lara could only become proactive after the threat of rape. Pratchett, who was unable to disclose her role in the game’s writing at that point due to contractual requirements, was understandably frustrated by this misreading of both the situation and the ways that Lara was marketed (Pratchett in Gibson, 2012), and this moment remains an unsettling moment within the script. The incident underscored the sensitive nature of reimagining Lara. Giving her a sexualised motivation for becoming the “homicidal archaeologist” that Carr imagines her as, seemed both in incredibly poor taste and hugely excusative. Lara became a vengeful victim rather than a world-famous treasure hunter, and the debate that arose around this incident is also testimony to the increasing sophistication of players and gaming communities. Players cared about Lara, and wanted her to retain the role of “strong female character” without the caveats that would be unnecessary for a male counterpart.

Tomb Raider was released in a year notable for games with strong narratives based around a female protagonist (or perhaps, one hopes, a year in which female protagonists finally started to become commonplace) As such, the impact of the game is somewhat lessened by games such as The Last of Us and Beyond: Two Souls. Although Tomb Raider is fairly straightforward in terms of plot, it still manages to provide an immersive experience and shows a considerable maturity when compared to its predecessors. The game charts Lara’s discovery of self, emphasising her growing reliance on herself rather than others (specifically, men). Over the course of the game she is betrayed by a peer as well as losing a protector, a mentor and a would-be lover. Her self-sufficiency is apparent when, from the middle of the game onwards, the remaining members of The Endurance look to her for help, leadership, and rescue. As narratives go, this is a fairly standard Hero’s Journey (Campbell, 1949), but it makes a very clear point -- the complacent reliance on others that Lara possesses at the start of the game is ultimately replaced by the singularly driven Tomb Raider that we recognise from the previous games. Whether this would have happened without the insertion of a female writer is a moot point, but the game certainly provides the player with a deliberately proactive Lara who learns self-sufficiency from those around her.

“Take That, Bitches!” Enter the Reframed Narrative.

Oh Man. SO Excited. I hope you’re ready, cos we’re gonna…we’re gonna play this; play the HECK out of this. It’s gonna be great.

(Rutherford: opening lines to her playthrough of the Tomb Raider game, 2013)

Hannah Rutherford is the most prominent female member of The Yogscast, the largest YouTube channel in the UK. Her daily programmes predominantly feature playthroughs of adventure and AAA games, which involve Rutherford recording her own play of each game, overlaid by her in-game commentary. YouTube channels such as The Yogscast have been instrumental in changing the ways that gamers consume games -- it is estimated that 95% of gamers watch YouTube gaming videos, for example -- meaning that these shows not only have large audiences, but that these audiences translate directly into revenue for the games companies whose works are featured (Getomer et al., 2013). For many viewers, these short recordings are more popular than terrestrial television and webcasts of this nature are consumed regularly across a broad spectrum of the gaming community. The Yogscast’s core demographic hits both older players between 30 and 40, as well as younger players in their teens, thus crossing both the traditional target audience (young, heterosexual white males), and the much championed new group of second generation players who now make up the “average gamer” (Yogscast, 2012; ESA, 2013). This demographic is also that most likely to have grown up with Lara Croft.

As an extremely popular YouTube channel with millions of subscribers, The Yogscast have considerable influence over game sales and revenue, as well being perceived by their viewers as spokespeople for gamers on an international level. (I have discussed the importance of webcasting and YouTube gaming elsewhere; see MacCallum-Stewart, 2013, 2014). They are rapidly approaching 5 billion hits across all of their channels and have a huge, dedicated following. Authentic discussion of a game’s merits is a feature of their work, and was instrumental in their initial elevation to such a position of importance by other gaming fans. If they play a game that they think is bad or broken in some way, this will become apparent during each video, where the presenters talk over their own playthroughs of each game. Rutherford’s playthrough of Tomb Raider consists of 28 videos between 20 and 40 minutes long, in which she plays through the game and records her responses. The viewer sees the game as played through Rutherford’s “Lara”, hearing both the diegetic sounds of the game and the non-diegetic intrusion of her overlying narrative. Each episode has minimal editing -- Rutherford is a skilled player and rarely needs more than two or three tries to succeed in a task (although we often see her repeatedly failing to do something for comic effect or to illustrate a ludic weakness) -- and present the viewer with an archetypal playthrough, complete with failures, confusions and mistakes. The videos therefore comprise a useful appraisal of the game, as well as containing discussions of core game dynamics, weak spots and emotional responses to moments of tension, excitement or shock. It is this honesty -- the viewer is seeing a warts and all recounting of the game, which is so popular with viewers. The members of The Yogscast are celebrities in their own right, but their work allows others to judge whether or not they might like a game, and to gain some idea on a personal level of whether or not it contains elements that they might enjoy. Hannah Rutherford’s Tomb Raider playthrough (which aired 4 March 2013 - 26 April 2013) was one of the most popular shows on Rutherford’s channel in 2012. The series gained over 10 million views in total.

Recorded playthroughs of this nature reinscribe the core text with new narratives, superimposing the story of the narrator playing the game over the game itself. Throughout the Tomb Raider playthroughs, Rutherford compares the game to other moments in gaming history, as well as locating it within her own understanding of Tomb Raider and Lara Croft -- as a person, as a franchise and as a part of gaming history. The viewer therefore witnesses Lara through three frames: the first being Pratchett’s underlying story; the second, Lara’s actual actions in the game; and the third, Rutherford’s interpretation of them through play (which may not always follow the linear path intended). Therefore the viewer of these videos not only consumes multiple perspectives of the game, but sees it contextualised within a female experience of play and gaming. Rutherford’s dialogue frequently references other games as well as various cultural references to events that are taking place elsewhere. For example, in one episode she discusses how she and her partner “won” a popular quiz show they were watching on television by identifying The Endurance as a name which is not currently in use by the British Navy, and in others she compares her play experience to a survivalist promotional event in which she was invited to experience the “reality” of Tomb Raider. The playthroughs are also punctuated by comparisons with other Tomb Raider games, where it is clear that Rutherford has played the series since its inception. Her responses to Lara herself are semantically interesting. As a presenter known for excessive spill cries (Conway, 2010) during play, especially rather foul-mouthed ones, Rutherford’s language is moderated towards care in her treatment of Lara. While she tends to use extremely pejorative language towards female avatars in other games (including calling a Catwoman avatar she was playing a “whore” in one episode of her Batman; Arkham Asylum playthrough), there is a notable softening of this when dealing with Lara (and later, Jodie in the Beyond: Two Souls series of videos). Lara is a “silly sausage” and a “broad”, with Rutherford instead directing more excessive words towards the male enemy, who are almost unanimously described as “bitches” throughout the episodes. The gendered language appears to suggest a scale of response, in which Lara is protected and gently chastised when she does something wrong, whereas male avatars in different games have a more extreme fate. Batman is frequently called a “fucking idiot” when his avatar responds poorly to Rutherford’s direction in the Arkham games, for example.

Rutherford’s playthrough is interesting on several levels. It is indicative of the growing presence of women in gaming culture, yet Rutherford rarely draws attention to this. For her, identifying as a gamer takes precedence over self-identification as a “girl gamer”, and her playthroughs are seemingly not predicated by explicitly gendered responses (this is discussed both in the playthroughs, on her Twitter stream and via an interview with the author). Like Pratchett, Rutherford wants to be identified as a player first, and not by her gender, situating herself as a lover and critic of games rather than a woman. Her behaviour towards Lara might be read as maternalistic, but on viewing the episodes, her possessiveness and care seems more to have been born out of a longstanding relationship with Lara that has been going on since both were in their formative years. Rutherford is one of the players ignored by the critics (she is barely older than Lara herself), and her experience of play is repeatedly iterated in the playthroughs as one of affection. Rutherford is well aware of Lara as sexualised “get a good look, because that’s the last shot of her tits you’re going to see” she says gleefully, as Lara falls off the side of The Endurance into the sea during episode one of her playthough (Rutherford, 2013), but her discussions are more about Lara’s playability, or previous narratives in earlier games. She is fond of Lara, and frequently comments on how the avatar has been improved from previous series, but seems relatively unbothered by her prior status as a sex object.

Both Pratchett and Rutherford refuse to act as apologists for Lara. Acknowledging her dubious past does not, for them, intervene in their affection for her as a gaming icon and a fundamental part of their early gaming experiences. For Pratchett, she is a powerful character with substantial narrative potential. Her script reflects an affection and understanding of Lara, bringing her up to date with a very clear knowledge of the games that have preceded her iteration. For Rutherford, Lara is a reimagined heroine from her childhood, one with whom she shares a great deal of pleasurable memories. Both are fully aware of her problematic status, but choose to represent and remember her as a powerful, engaging character who appealed to them as young women players, rather than a derogatory representation of feminine subjugation.

Conclusion.

By demonising Lara we have, I believe, pushed ourselves into a corner that only allows us to apply binary sexual readings to her, as well as refusing to acknowledge Lara as a peer amongst other gaming avatars. Continually regarding Lara’s sexualisation as a negative quality will forever keep her apart, and will by default, other players who never even considered her a problem. Lara is rather like the debates that surround the authenticity of the gaming woman: like the “fake gamer girl”, she is decried for her looks, and yet they are a fundamental part of who she is and are unrelated to her central identity as a gaming woman. Lara’s new avatar presents her as a more average figure, making her somewhat more emancipated than the lumbering, ape-like form of Connor in Assassin’s Creed III (Ubisoft, 2012), or the irritatingly servile nature of wasp-waisted Elizabeth in Bioshock Infinite. It also, rather surprisingly, throws into sharp contrast some of the more offensive stereotypes in the recent game -- the bearlike Jonah and Alec Wiess, the drippy, lovelorn male geek whose physical representation is so archetypal that the same body actor plays an identical character called Marc in Telltale Games’ The Walking Dead (2012).

Lara’s new iteration has also allowed the old fans to emerge, most of them somewhat surprised at the harsh treatment Lara has had to endure. When writing this paper, friends and sometimes colleagues expressed alarm at her maltreatment at the hands of critics. “But, it’s Lara!” was a frequent, surprised comment, as if the Tomb Raider spoke for herself as an icon of liberated independence. Several of these peers found it baffling that anyone see her as anything other than a heroine, and were often rather aggrieved to hear how she had been maligned.

Lara is to-be-looked-at, and always has been, but she is also to-be-played. Her femininity is ignored, in so much as that it is an unmistakable element of the game, and cannot be avoided, but at the same time, as Aarseth suggests, it is impossible to constantly be mindful of this whilst playing. When recent shots of a male avatar dressed as Lara and drawn in some of the same poses as her attracted attention and comment, there was no suggestion that this nameless, somewhat androgynous young man should replace her in any way. Lara is an icon, and complete with this is the understanding that she represents various aspects of gaming. Attempts to change these are laudable, as is the realisation that many of Lara’s prior faults are clearly understood by her players.

The position that Lara has been given is unfair, therefore, but somewhat inevitable. Despite her new incarnation, it is unlikely that her gender will ever disappear entirely from the text; nor should it. Crystal Dynamics tried, and to some extent (but not entirely) succeeded in returning Lara to her fundamental state -- she is once again a female adventurer in a world of peril. She is still troubling in terms of gender, but so are many of the other representations that surround her. It seems that her recent incarnation has managed to highlight this, and the re-mergence of the Tomb Raider franchise has also prompted welcome discussions, and some changes within the games industry. After nearly twenty years breaking into crypts and being chased by dogs, it will be interesting to see whether the re-imagining can continue to challenge gendered representations within games, and the subsequent debate that should take part around this.

Lara’s neglected appropriation by fans and players also argues that critics need to move beyond her body. The changing game dynamics and mechanisms of the game, by which Lara emerges from the tomb and becomes a more active, social participant in a more complex game world, also argue that looking forwards to different critical angles is important. Lara is frequently compared to her male counterparts, but as Pratchett argues, this is a false equivalency; in fact these male bodies are not considered in such depth or through such a narrow lens of sexualisation. Perhaps future studies should move beyond this binary construction. Refiguring Lara as simply another gaming icon has important ramifications for the ways in which gender, and feminist argument, are consumed and produced within gaming discussion, and whilst she remains an important figure of debate, it is time to truly look beyond her and towards the more nuanced discussions that she has enabled.

Bibliography.

Aarseth, Espen. (2004). “Genre Trouble, Narrativism and the Art of Simulation” in Wardrip-Fruin, Noah, and Harrigan, Pat Eds. First Person. New Media as Story, Performance and Game. Massachusetts: MIT Press. 45-55.

Bernstein, Joseph. (2013). “Two Decades of Breathtakingly Sexist Writing about Tomb Raider”. http://www.buzzfeed.com/josephbernstein/two-decades-of-breathtakingly-sexist-writing-about-tomb-raid 25 February 2013

Bland, Archie. (2013). “Why Lara Croft’s Feminist Credentials are as Inflated as her Chest used to be”. The Independent. http://www.independent.co.uk/voices/comment/tomb-raider-why-lara-crofts-feminist-credentials-are-as-inflated-as-her-chest-used-to-be-8521099.html 5 March 2013.

Bolser, Jen. (2013). “How Crystal Dynamics Tomb Raider Empowered Lara Croft” http://www.forbes.com/sites/jenniferbosier/2013/03/11/how-crystal-dynamics-tomb-raider-empowered-lara-croft/ 11 March 2013.

Brouwer, Bree. (2013). “How Tomb Raider (2013), Convinces Me To Take Lara Croft Seriously”. http://geekmylife.net/tomb-raider-lara-croft 7 March 2013.

Campbell, Joseph. (1949). The Hero with A Thousand Faces. Princeton: Bollingen Foundation.

Carr, Diane. (2002). “Playing with Lara” in Krzywinska, Tanya and King, Geoff eds. Cinema/Videogame Interfaces. London: Wallflower Press.

Cassell, Justine and Jenkins, Henry. (2000). From Barbie to Mortal Kombat: Gender and Computer Games. Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Chambers, Becky. (2013). “Lara Croft is Dead: Long Live Lara Croft”. The Mary Sue. http://www.themarysue.com/tomb-raider-review/ 8 March 2013.

Conway, Steven. (2010). “Argh! An Analysis of the Response Cries of Digital Game Players”, paper given at Under the Mask 2010: Perspectives on the Gamer. 2 June 2010.

Dovey, Jon and Kennedy, Helen. 2006. Game Cultures: Computer Games as New Media. Reading: The Open University Press.

Edge (staff writer). 2008. “Is Lara Croft Sexist?”. Edge Online. http://www.edge-online.com/features/lara-croft-sexist/ 1 September 2008.

Egenfeldt Nielsen, Simon; Heide Smith, Jonas and Tosca, Susana Pajares. (2008). Understanding Video Games: The Essential Introduction. New York: Routledge.

ESA (Entertainment Software Association). (2013). “Game Player Data”. http://www.theesa.com/facts/gameplayer.asp 1 November 2013.

Getomer, James; Okimoto, Michael and Johnsmeyer, Brad. (2013). “Gamers on YouTube: Evolving Video Consumption”. Google. https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/articles/youtube-marketing-to-gamers.html July 2013.

IGN (staff writer). (1996). “Tomb Raider”. IGN. http://uk.ign.com/articles/1996/12/14/tomb-raider-5. 13 December 1996.

Jenkins, Henry. (2006). The WoW Climax. Tracing the Emotional Impact of Popular Culture. New York: New York University Press.

Kennedy, Helen. (2002). “Lara Croft: Feminist Icon or Cyberbimbo: On the Limits of Textual Analysis”. Game Studies Vol2 #2. http://gamestudies.org/0202/kennedy/

King, Geoff, and Krzywinska, Tanya. (2006). Tomb Raiders and Space Invaders: Videogame Forms & Contexts. London: I.B.Tauris.

Kirkland, Ewan. (2014). “Experiences of Embodiment and Subjectivity in Haunting Ground” in Visions of the Human in Cyberculture, Cyberspace and Science Fiction, Rodopi Press.

Kuchera, Ben. (2013). “Tomb Raider’s Writer Discusses the Press, Gender, and Lara Croft’s Body Count. Penny Arcade. http://www.penny-arcade.com/report/article/tomb-raiders-writer-discusses-the-press-gender-and-lara-crofts-body-count5 March 2013

Lejacq, Yannick. (2013). “Tomb Raider writer Rhianna Pratchett on why every kill can't be the first and why she hoped to make Lara Croft gay“. Kill Screen. http://killscreendaily.com/articles/interviews/tomb-raider-writer-rhianna-pratchett-why-every-kill-cant-be-first-and-why-she-wanted-make-lara-croft-gay/ 13 March 2013.

Lou, et al. (2013). “Gender Swapping and User Behaviors in Online Social Games” Paper given at the International World Wide Web Conference Committee (IW3C2). May 13-17 2013, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. http://www2013.wwwconference.org/proceedings/p827.pdf

MacCallum-Stewart, Esther. (2008). “Real Men Carry Girly Epics - Normalising Gender Bending in Online Games”. Eludamos, Vol 1 #2. http://www.eludamos.org/index.php/eludamos/article/view/35/54

MacCallum-Stewart, Esther. (2013). “Diggy Holes and Jaffa Cakes: The rise of the elite fan-producer in Videogaming culture”. Journal of Gaming and Virtual Worlds. Vol.5 #2, October 2013. 165-184.

MacCallum-Stewart, Esther. 2014. Online Communities, Virtual Narratives. New York: Routledge.

Metacritic. 2010. “Lara Croft and The Guardian of Light”. Metacritic. http://www2013.wwwconference.org/proceedings/p827.pdf

Pinchefsky, C. (2013). “A Feminist Reviews Tomb Raider’s Lara Croft.” Forbes.com. http://www.forbes.com/sites/carolpinchefsky/2013/03/12/a-feminist-reviews-tomb-raiders-lara-croft/ 12 March 2013.

Polo, Susana. (2013). “Tomb Raider: A chance to make a difference”. The Mary Sue. http://www.themarysue.com/tomb-raider-rhianna-pratchett/ 4 March 2013.

Gibson, Ellie (2012). “Rewriting Tomb Raider”. Eurogamer. http://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2012-11-01-rewriting-tomb-raider-a-conversation-with-rhianna-pratchett. 2 November 2012.

Rutherford, Hannah. Yogscast Hannah. http://www.youtube.com/user/yogscast2

(2013). “Tomb Raider - 1. Endurance”. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ivWz9yic71k 4 March 2013.

Rutter, Jason and Bryce, Jo. Understanding Digital Games. London: Sage.

Schmidt, Christian. (2008). “Emotional Rollercoaster with Lara”. GameStar. http://www.gamestar.de/test/action/adventure/1951239/tomb_raider_underworld.html 21 November 2008.

Schleiner, Anne-Marie. (2001). “Does Lara Croft Wear Fake Polygons: gender and Gender-Role Subversion in computer Adventure Games” Leonardo. June 2001, Vol. 34, #3, pp. 221-226.

Shanthini, M. (2013). “Why I love Lara Croft the Tomb Raider”. The Archaeology of Tomb Raider. http://archaeologyoftombraider.wordpress.com/2013/08/31/guest-blog-why-i-love-lara-croft-the-tomb-raider/ 31 August 2013.

Yee, Nick. (2006). The Demographics, Motivations and Derived Experiences of Users of Massively-Multiuser Online Graphical Environments. in PRESENCE: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 15, 309-329. http://www.nickyee.com/pubs/Yee%20-%20MMORPG%20Demographics%202006.pdf

Yogscast. (2013). “Viewer Demographics 2012”. These statistics were provided by Mark Turpin of the Yogscast and were derived from Google Analytics.

Zydrko, David. (1999). “Tomb Raider: The Last Revelation”. IGN. http://uk.ign.com/articles/1999/12/04/tomb-raider-the-last-revelation-3 4 December 1999.

Filmography.

Tomb Raider. (2001). Paramount Pictures.

Tomb Raider: The Cradle of Life. (2003) Paramount Pictures.

Ludography.

Batman, Arkham City. (Rocksteady Studios, 2011)

Beyond Two Souls. (Quantic Dream, 2013)

Bioshock Infinite. (2K Games, 2013)

Grand Theft Auto 5. (Rockstar, 2013)

Haunting Ground. (Capcom, 2005)

The Last of Us. (Naughty Dog, 2013)

Metroid. (Nintendo, 1986)

Mirror’s Edge. (Electronic Arts, 2008)

Mirror’s Edge 2. (Electronic Arts, tbr 2014)

Portal. (Valve Entertainment, 2007)

Resident Evil. (Capcom, 1996)

Tomb Raider. (Core Design, 1996)

Tomb Raider II. (Core Design, 1997)

Tomb Raider: Underworld. (Core Design, 2008)

Tomb Raider: Guardian of Light. (Core Design, 2010)

Tomb Raider. (Crystal Dynamics, 2013)

The Walking Dead. (Telltale Games, 2012)

[1] This quotation has been used extensively in subsequent articles to Kennedy’s; however, I have been unable to trace this quotation in the original text that she cites (Cassell and Jenkins).