“Honestly, I Would Stick with the Books”: Young Adults’ Ideas About a Videogame as a Source of Historical Knowledge

by Kevin O’Neill, Bill FeenstraAbstract

Decades of research have examined the trust people place in various sources of knowledge about the past, such as documentary films and historic sites. However, despite their popularity, peoples’ thinking about videogames as sources of historical knowledge has not yet been examined empirically. Twelve Canadian university students with varying exposure to history instruction and varying gameplay habits were asked to play the D-Day level of Medal of Honor: Frontline under observation. They were interviewed about how “realistic” they thought the game was, and how they made this judgement. When they lacked the historical knowledge to critique the game’s specific depiction of events and situations, participants judged its trustworthiness as a source in two ways: by identifying game features that appeared unrealistic, and taking these as indicative of the developers’ approach to historical realism; or by trying to imagine the motives that commercial game developers might have for working to achieve historical realism.

Keywords

videogames, history, youth, sources, trustworthiness

Introduction

Since the late 1990s, researchers have repeatedly examined the general public’s engagement with history outside of school. Surveys have taken place in Europe (Angvik & von Borries, 1997), the United States (Rosenzweig & Thelen, 1998), Australia (Ashton & Hamilton, 2003) and Canada (Conrad et al., 2013); examining what history matters to people, and what sources (e.g. historic sites, museums, teachers, books, documentary films, etc.) they trust to inform them about it. Recently, empirical research has begun to document how the changing media landscape is altering how people engage with the past (Conrad et al., 2013).

The extracurricular interests that youth display in history have been of special concern to researchers, since formal history teaching often does not capture the types of interest that youth have in the past (Levstik & Barton, 1997; Barton & Levstik, 2003). In a nationally-representative survey, for example, Canadian students rated history and social studies the least interesting of all subjects in school (Statistics Canada, 2004). The reasons for young peoples’ lack of interest in school history continue to be a subject of debate. However, of relevance to the present study, Prensky (Prensky, 2001) and others have argued that people who have been raised with omnipresent rich media simply learn differently. According to Prensky, “digital natives…thrive on instant gratification and frequent rewards. They prefer games to ‘serious’ work” (Prensky, 2001, p. 2).

Though Prensky’s ideas about digital natives have been critiqued by scholars (Bennett, Maton & Kervin, 2008; Helsper & Eynon, 2010), games researchers have continued to argue that videogames exemplify a powerful new pedagogy that has evolved in the marketplace to maximize engagement and learning because without doing so, a game will not sell (Gee, 2003; Shaffer, Squire, Halverson & Gee, 2005). The most recent of the national surveys of public engagement with history discussed above (Conrad et al., 2013) provided evidence that videogames are indeed one way in which Canadians believe they engage with the past -- though the authors did not address the subject in detail.

Videogames set in the past have certainly sold well. Some particularly successful game franchises, such as Battlefield, Call of Duty and Medal of Honor, have been based on events from World War II. New editions of the Civilization games, in which play stretches from prehistory into the future, continue to be released. As scholars have observed (e.g. Schut, 2007), the mechanics of these games are not much different from other videogames of the same genres, and have potentially problematic biases built in. However, considering the unpopularity of school history, it is impressive that young people choose to use their free time playing videogames set in the past. In fact, the Medal of Honor franchise, which is addressed in the present study, was named the best-selling game franchise of all time in 2008 (Guinness World Records Limited, 2008).

Scholars have suggested that the popularity of history games like Medal of Honor may reflect an existential longing for a time when “life was more real” (Kingsepp, 2007), and involved life-and-death struggles (Hong, 2015). At the same time however, immersing oneself in playing a game like Medal of Honor does not necessarily imply either understanding of or belief in its representations of the past (Hong, 2015). Scholars have argued that the concept of “realism” in games is a complex matter (Galloway, 2006), and scholarly analysis of games has shown that their representation of military conflict is not only selective, but political (Pötzsch, 2015; Šisler, 2008, 2009).

As scholars interested in the potential of learning history with games, we wondered about the ability of young adults to critique representations of the historical past in a commercial game without explicit coaching. Further, in what ways would they carry out such critique?

Related Literature

Two bodies of empirical research are particularly relevant to our study: the literature on public trust in various sources of knowledge about the past, and the literature on videogames and history learning.

Videogames set in the past can be considered alongside television documentaries and nonfiction books as a kind of historical source that people may encounter in daily life. One of best known nationally-representative surveys of public engagement with the past found that Americans placed less trust in books, films and television as sources of historical knowledge than they did in museum exhibits, family members, professors and teachers (Rosenzweig & Thelen, 1998). The study provided evidence of a “trust hierarchy” of sources of knowledge about the past. However, a lot has changed since the time that Rosenzweig and Thelen collected their data. Among other things, in 1998 the Internet was less a part of most peoples’ daily lives, and the genre of history games was less well developed than it is today.

In recent years, a national telephone survey conducted in Canada found that when asked which sources of knowledge about the past they found “very trustworthy”, respondents between the ages of 18 and 29 most often chose museums, followed by nonfiction books, historic sites, family stories, teachers, and, finally, web sites (Conrad et al., 2013). Historical videogames were mentioned by some participants, but were not routinely asked about in the survey; so they were left as a matter of speculation. How might a commercial history game fit into young adults’ current hierarchy of trust?

The small but growing literature on the classroom use of videogames in history teaching also furnishes some useful insights to frame our study. For a number of years, scholars have made forceful arguments about the opportunities that commercial videogames may offer for history learning. One advocate, McCall, argues that:

At their best, simulation games are powerful learning tools [for history] because they enable students to make meaningful choices within the problem spaces of the past…. [The] capacity for simulation games to provide navigable historical problem spaces is their greatest contribution to a 21st-century history education at any level of instruction (McCall, 2011, pp. 11--12).

The enthusiasm of McCall is not unusual. The small number of empirical studies that have addressed history learning with videogames seem to have been based on an a priori assumption that young people would not only be motivated to engage with the past through games, but would view them as legitimate (i.e., trustworthy) sources of knowledge about the past. However, this expectation has been repeatedly frustrated.

In one of the earliest studies involving the use of a commercial videogame for learning history, Squire and Barab used Civilization III as part of a design for teaching world history at the high school level (Squire & Barab, 2004). In their study, the researchers examined the process through which a group of secondary students who had previously failed a World History course appropriated Civilization III as a tool for learning history in a formal school context. This process of appropriation turned out to be time-intensive and challenging, both for the students and their teacher. According to the researchers’ account, it took four class days before students began to take the game seriously as a tool for learning history. This is a long time in the working life of a teacher.

Other scholars built upon Squire and Barab’s work (e.g. Lee & Probert, 2010; McCall, 2011; Pagnotti & Russell, 2012), placing particular focus on ways to maximize students’ engagement with commercial history games. Watson, Mong and Harris (2010), for instance, examined the use of a World War II strategy game called Making History: The Calm and the Storm to teach a sophomore history class in the midwestern United States. In this study, the researchers examined the details of the teacher’s craft in supporting students’ work with the game, and the influence of the game on the student-centredness of the learning environment. The researchers do not appear to have directly examined how students understood their engagement with the game as a means to acquire trustworthy knowledge about the past.

Postsecondary students have not often been the focus of published research on history learning with videogames, however McMichael (2007) provided a detailed account of his redesign of a college-level course on “Western Civilizations Through 1648” around several commercial history games, including Civilization III. His course design involved both specific gameplay assignments and regular essays asking students to evaluate specific theses about the games, for example, “The video game Civilization III is accurate in its portrayal of gender roles across different civilizations.” (McMichael 2007, p. 212) In his reflection on the experience, McMichael offered an intriguing informal description of a trust hierarchy discussed in class by his students:

There was…a kind of hierarchy in students’ minds regarding how accurate different presentations of history had to be. History in the classroom had to be the most accurate…. Next came media such as public television, followed closely by the cable channels such as Discovery or the History Channel, which my students viewed as a kind of surrogate classroom…. Last in their hierarchy came movies and video games, which only had to be accurate enough, in their minds, to be recognizable and not to be so historically bizarre as to affect playing the game (McMichael, 2007, p. 213).

The central focus of our study is to examine this trust hierarchy, and the thinking process behind it, more formally.

Framing the Study

Unlike the studies described in the previous section, ours took place in an extracurricular context, addressed a more popular genre of game (first-person shooter, rather than strategy), and focused directly on participants’ understanding of the learning opportunities provided by the game itself, rather than formal instruction that might be designed around it. It is important to explain our rationale for this set of choices.

While educators’ interest in commercial games as teaching tools is increasing, for most young people, leisure gameplay involves far more total time than gameplay in school contexts. The ideas that young people develop in leisure gameplay are important in themselves, but are also likely to influence their reception of teachers’ use of history games in the classroom. We chose the game Medal of Honor: Frontline (EA Games, 2002) for our study partly because this franchise (and the first-person shooter genre more generally) has been very popular, and thus likely to exert influence on young peoples’ thinking about the trustworthiness of games as sources of historical knowledge. Further, Medal of Honor: Frontline (hereafter referred to as MoHF) has a lower learning curve than a typical strategy game (such as Civilization), meaning that it was practical to use in a study of short duration because participants did not need to invest much time before they could play it with enjoyment. Finally, both authors had played the game years earlier, and therefore felt well equipped to observe and analyze study participants’ play and discussion of the learning opportunities provided by this game.

As discussed by other authors (e.g. Kingsepp, 2007), gameplay in MoHF is clearly intended to seem authentic to a historical past that players might recognize from popular culture and classroom instruction (see the section “Medal of Honor: Frontline” below). This was important to consider in the design of our study, because it seemed likely that young adults’ understanding of the trustworthiness of a videogame as a source of knowledge about the past would be related to how the game experience connected with what they already knew about the events and situations depicted in the game. Notably however, commercial first-person war shooter games are selectively authentic to the events they refer to (Salvati & Bullinger, 2013). While, as Galloway states, games like MoHF have as their “central conceit the mimetic reconstruction of real life”, “realisticness and realism are most certainly not the same thing” (Galloway 2006, pp. 72--73). A game can have such a high polygon count that it is visually photorealistic, yet “photorealist…games provide privileged attention to easily accessible and largely unproblematic surface phenomena [of war] such as object physics, weapons, equipment, avatar movements, and team interaction, and discourage engagements with the challenging, ambiguous, and contingent sides of violence and suffering...” (Pötzsch, 2015, p. 6). The design of war games like MoHF effectively filters out many aspects of war, such as civilian casualties, post-traumatic stress disorder, and political blowback (Pötzsch, 2015).

Part of what makes the nature of realism in a game like MoHF crucially different from realism in film (Ball & Smith, 2011) is that the player must constantly act. Thus, “…the player has a more intimate relationship with the apparatus itself, and therefore with the deployment of realism. The player is significantly more than a mere audience member, but significantly less than a diegetic character. It is the act of doing, of manipulating the controller, that imbricates the player with the game” (Galloway 2006, p. 84). In some scholarship it is implied that the immersive and interactive nature of the game medium (as compared to film and textual narrative) may itself lead the player into historical empathy (e.g. Schulzke, 2013). Our study provided an opportunity to examine this optimistic view. In the sections that follow, we will examine how our study participants understood the particular ways in which the opportunities for action provided by MoHF did and did not provide opportunities for understanding the lived reality of the past.

Research Questions

In the following sections, we address three main questions:

Question 1: How did participants view MoHF as a source of historical knowledge?

Question 2: How trustworthy did participants consider MoHF as a source of knowledge about the past?

Question 3: How did participants make their judgements about the trustworthiness of MoHF as a source?

To address these questions, we interviewed twelve young adults at length after they had played the D-Day level of MoHF for 30 to 45 minutes. We were open to any kind of knowledge that participants suggested they had gained from the game, but probed specifically for evidence that they understood and appreciated two kinds of opportunities that the game presented for better understanding the past. The first was empathetic understanding -- the understanding of historical actors in their particular circumstances -- which is often considered an important facet of historical thinking (Davis, Yeager & Foster, 2001; Peck & Seixas, 2008; National Center for History in the Schools, 1996). The second opportunity we probed for was incidental learning outside the game environment itself, such as when a game introduces the player to people, places and events from the past, and kindles curiosity about them. Finally, we directly probed participants’ ability to critique the limitations of the game as a representation of the past, as such limitations are substantial in any game (Kingsepp, 2007; Schut, 2007; McCall, 2011).

Medal of Honor: Frontline

For those unfamiliar with the game used in our study, MoHF is a first-person-shooter game that places the player in the role of a fictional U.S. Army intelligence officer named Jimmy Patterson during World War II. The game’s design could appropriately be described as “antiquarian”(Metzger & Paxton, 2014) in that it aims to support an experience of period warfare using features such as weapons that look, sound and function in a way that is recognizably authentic to those familiar with the period, though the representation of the historical situations and events is undeniably simplified and distorted to suit the purposes of game play. Hong (2015) fittingly describes such antiquarian games as involving “a pragmatic pillaging of historical, mythical and ritual elements” (p. 36).

In MoHF, the player participates in a variety of missions, including the D-Day landing at Omaha Beach. The D-Day level was chosen as the focus of the observed gameplay portion of our study for two reasons. First, young adults might be expected to appreciate the attempts at historical authenticity made by the game designers in this level, because D-Day is covered in history curricula throughout the Western world (including Canada), and because there have been vivid depictions of the D-Day landing in popular culture, such as in the 1998 film Saving Private Ryan (Spielberg, 1998) which the game’s depiction closely resembles (Kingsepp, 2006). Second, the D-Day level seemed to hold promise for developing empathetic understanding, for reasons we will discuss below.

As suggested above, many of the details and scenarios in MoHF appear to have been designed with attention to historical authenticity. A review of the game by Rivers (2002) for the web site GameSpot praised the game for its apparent historical detail:

The attention to detail in all of [the levels] is outstanding, with city levels that look like they were taken straight from the pages of history…. The attention to historical details further augments the experience... (Rivers, 2002).

Another reviewer remarked:

…[E]verything looks and feels like vintage material from the 1940s wartime era. Missions are preceded with segments of black-and-white war footage, as well as a manilla dossier that outlines mission objectives (Johnson, 2004).

Despite its patina of historical authenticity and the incorporation of authentic names, places and details that can be studied outside the game environment, the game world of MoHF is in many respects as simplified as those of other commercial videogames. For example, in MoHF few of the computer-controlled characters speak. When they do, they deliver only short, pre-recorded lines of dialogue. The player’s own character is mute, and his range of actions is limited by the design of the game maps and mission objectives. Further, while the player has control of the fictional historical character of Jimmy Patterson, s/he progresses through a predetermined game narrative in the sense that all missions follow one another in a linear path. Unlike in Civilization, there is only one route to victory. In this and other respects that will be discussed later, the game’s depiction of historical events and situations presents a host of opportunities for player critique. Yet, would our study participants see these?

The D-Day level of MoHF played by the participants in our study begins with an in-game scene of soldiers on an infantry carrier boat, being attacked as they approach the French coast. Once the boat lands, gameplay commences and the player is given the objective to find a Captain, amid a hail of gunfire and explosions. The player must immediately find cover to avoid being killed on the spot. If the player dies, the level begins again [1].

If the player finds the Captain, a new objective is provided: to rescue four squad members who are pinned down by enemy fire. When the squad is rescued they proceed to the base of a sand dune, which is impassable due to barbed wire. The Captain then orders the player to find an engineer (also pinned down by enemy fire) and bring him back to blow up the barbed wire barrier. The player must then proceed through a live minefield, and use a turret gun to take out other German turret guns located on a ridge above the beach. If the player completes all these objectives (despite constant threat from enemy soldiers), the squad is able to cross the minefield and meet the player at the door to a German bunker.

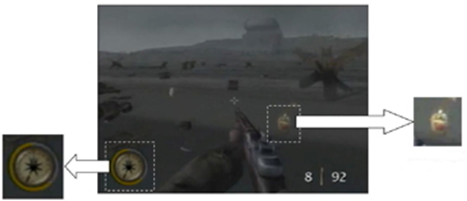

As gameplay progresses, the player’s character will be injured by enemy fire and other hazards. This reduces the player’s health meter, which is a prominent feature of the game’s Heads Up Display (or HUD). As the level begins, the health meter is a full green circle surrounding the compass in the lower-left corner of the screen. As the player is injured, the meter becomes a semi-circle that turns yellow (see Figure 1), then red to indicate imminent death.

Figure 1: Heads Up Display with low health meter and medicinal canteen marked.

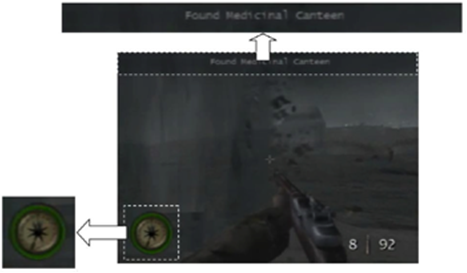

If the health meter reaches zero, the player dies and returns to the start of the level, or the last completed checkpoint in the level. However, to keep the game going, MoHF allows the player’s health to be replenished instantaneously by picking up canteens and first aid supplies (also called medkits), which are scattered around most levels. A canteen is magnified at the right of Figure 1. Figure 2 shows the player’s health meter being restored by picking up a canteen. As our analysis below will show, this mechanism of the health system had important implications for our participants’ views of the historical realism of MoHF.

Figure 2: Player’s health can be restored by a medicinal canteen.

In line with the arguments by McCall (2011) and Schulzke (2013) referred to earlier, an optimistic enthusiast of game-based learning might expect that through immersion in this simulated battlefield experience, players would learn to empathize with the allied soldiers who faced the D-Day landing. By virtually “living through” the landing, they might appreciate the difficult strategic position of facing an enemy who was fortified on high ground. By being repeatedly killed and watching non-player characters be killed, players might appreciate the danger involved in the real-life historical situation better than if they merely read about it as reported by an impersonal “voice of history” (Wineburg, 1991). Players might also, in a fuller way than would be possible with textual materials or even documentary films, develop a sense of how difficult it was for soldiers to make quick life-or-death decisions in a situation filled with noise, confusion and danger. The findings reported below provide an evidence-based assessment of this optimistic view.

Participant Recruitment

Participants for the study were recruited on the campus of a public university in Canada. These young adults (unlike high school students) had free choice about both playing videogames and studying history; thus this recruitment focus made it possible to construct a cross-section of experience of both gameplay and formal history instruction -- variables likely to influence young peoples’ ideas about videogames as sources of historical knowledge.

A purposive sample of twelve participants was recruited in two stages. After seeing an advertisement posted around the university campus, students responded to an online screening survey that asked about the number of history courses they had completed at university and how often they played videogames (this included PC, console, and mobile games). Thirty-eight students completed the screening survey. Twelve of these students were invited to take part in gameplay and interview sessions. Our aim in selecting participants was to maximize variation in both gameplay experience and exposure to history as a formal subject of study. Participants included seven female and five male students, ranging from 18 to 30 years in age, with a mean age of 23.

Table 1 describes participants’ exposure to gaming and formal study of history. For the purposes of our analysis, participants were divided into categories of “gamers” and “players” by their self-described frequency of game play. Participants who played games several times per week (n=9) were categorized as “gamers”, while students were categorized as “players” (n=3) if they played games a few times per month or less. Because the study was advertised as involving gameplay, game avoiders self-selected out; however industry data suggest that a substantial majority of American youth now play videogames -- 60% playing some kind of game on a typical day (Rideout, Foehr & Roberts, 2010).

Half the participants (n=6) had completed only high school history at the time of the study. Two participants had completed only one postsecondary course in history, while the remaining four had taken more than one postsecondary course in history. Among the four students who had taken more than one postsecondary course in history was one student completing a history minor. As Table 1 shows, we were able to recruit only one player without any exposure to postsecondary history from among our 38 screening survey respondents.

|

Player |

Gamer |

|

|

Some postsecondary history |

2 |

4 |

|

Only high school history |

1 |

5 |

Table 1: Breakdown of participants by exposure to gaming and historical study.

Data Collection

Participants were invited one at a time to a research lab, where they played MoHF under observation, and were interviewed afterwards. Each session took between 1 and 1.5 hours.

The intent of having each session consist of observed gameplay followed by an in-depth interview was primarily to ensure that interview questions regarding what might be learned about history from a videogame would not be viewed as purely conceptual or hypothetical from the participants’ perspective. MoHF was not the only game referred to by participants in their interviews; however the gameplay portion of the lab session established a common frame of reference for the participants despite the differences in their previous game play habits and exposure to history as a subject of study.

The purpose of the interview portion of the lab sessions is more self-evident. Soliciting participants’ responses to research questions 2 and 3 seemed to demand an individualized, dialogical approach that included spontaneous follow-up questions.

Though we considered pre-testing participants’ knowledge of D-Day at the start of the data collection, in the final analysis we judged this to be unnecessary and overly intrusive. Participants’ level of knowledge became evident in the postgame interviews, during which participants either explicitly (in direct response to an interviewer’s question) or implicitly (through an explanation or elaboration) demonstrated their knowledge or ignorance of D-Day and its historical significance.

At the start of each session, the participant was briefly introduced to MoHF by a researcher, and asked to play the D-Day level described in the previous section. The recorded gameplay session lasted between 30 and 45 minutes, with the more skilled players taking less time. Gameplay was immediately followed by a semi-structured interview, which also lasted between 30 and 45 minutes, depending on how expansive participants were in their answers to prepared questions and follow-ups. The questions for the post game interview focused on participants’ interest in the game and the events it depicts, their understanding of what was realistic and unrealistic about the game (and how they made these judgments), and how they viewed the game as an opportunity to learn history.

Data Analysis

The recorded gameplay data were useful primarily for evaluating participants’ success in playing the game. This varied widely, with most participants failing to complete the D-Day level in the allotted time, while one participant finished four whole levels. While participants were encouraged to think aloud while playing, little verbal protocol data were produced due to absorbsion in the gameplay task. Thus, our analysis focused on the postgame interviews. Verbatim transcripts were created for all of these interviews, which were then imported into Maxqda (a qualitative data analysis software package) for analysis (verbi Software, 2011).

An initial open coding (Corbin, 2008) was carried out by the second author, with the intent of capturing the variety in participants’ responses to the interview questions. Over one hundred fine-grained codes were initially generated. Examples of open codes included “Electronic Arts [the game publisher] is an American company, so main character is American,” and “Germans just attack and yell; a very limited representation.” These codes were later consolidated and refined in consultation with the first author, and a formal codebook developed. The findings presented below are based on this codebook, which contains six codes tightly focused on the questions discussed above (see Table 2).

|

Code description |

Number of occurrences (out of 12 participants) |

Inter-coder agreement (Cohen’s Kappa) |

|

Participant knows about D-Day: Participant makes detailed, accurate statements about D-Day and its significance. |

6 |

1 |

|

MoHF is consistent with player’s existing (though perhaps limited) knowledge of WWII: Participant declares that the content of MoHF is consistent with his or her existing knowledge of WWII. |

10 |

1 |

|

MoHF promotes empathetic understanding: Participant describes MoHF as providing a sense of what battle would be like for a soldier. |

7 |

1 |

|

Focus of MoHF is entertainment: Participant declares entertainment to be the focus of MoHF, with other considerations, esp. historical accuracy, being subordinate. |

6 |

.33 |

|

Participant observes trade-offs between historical realism and the playability of the game: Participant expresses detailed understanding of trade-offs between realism and fun in the design of the game. |

11 |

1 |

|

Games less trustworthy than books or documentaries: Participant declares historical videogames less trustworthy than other media, such as nonfiction books and documentaries. |

6 |

1 |

Table 2: Coding categories for postgame interviews.

To test the explicitness of the codes in the codebook, several complete transcripts were coded independently by the two authors. The codebook was treated like a scorecard, with each code being applied in a binary fashion to the entire transcript. All discrepancies between the two sets of codes were discussed by the coders, and the code definitions refined to remove ambiguities. A reliability check was conducted with a subset of three transcripts. For five codes, the two coders achieved a Kappa of 1. For one code, Kappa was .33.

Results

Question 1: How Did Participants View MoHF as a Source of Historical Knowledge?

One might expect participants’ appreciation of MoHF as a source of historical knowledge to be shaped by their prior knowledge of the events depicted in the D-Day level. Of the 12 participants (all high school graduates), 6 demonstrated knowledge of D-Day in their interviews, and 6 did not. It is worth mentioning that in the Playstation 2 version of MoHF that our participants played, the opening “cut scene” (introductory video) for the D-Day level does not explicitly declare that the battle is D-Day; however the date of the battle (June 6, 1944) is presented on screen, and the beach landing by infantry carrier vessels (highly similar to a scene from the film Saving Private Ryan) is depicted before the gameplay starts.

One may have expected students who recognized the D-Day scenario to express an improved understanding of the strategic disadvantages and dangers the allied soldiers faced in this vital battle of World War II. However, when asked if MoHF “taught you anything about history”, all participants initially responded “no” or “not really”. Participant 8 immediately generalized this to all videogames:

Interviewer: Does it [the game] teach you anything about history?

Participant 8 (“gamer”, “only high school history”): I don’t think games really teach you anything about history.

When probed, two participants suggested that MoHF essentially taught that the war involved “Americans” fighting “Nazis”. Participant 2 provides an example:

Interviewer: Does it [the game] teach you anything about history?

Participant 2 (“gamer”, “only high school history”): So far as what I have extracted from the game…I did not actually get any history from the game itself other than the Americans fought the Nazis….

Learning experiences can produce tacit knowledge that is as valuable as explicit knowledge (Polanyi, 1962), so it is possible that participants gained knowledge from MoHF that they were not able to explain. However what concerns us here is that young adults’ understanding of videogames as sources of historical knowledge (either in or out of school) may be shaped in important ways by what they consciously believe they can learn from them.

Despite believing that MoHF had not taught them anything about history, a quarter of our participants suggested that this was because they had not progressed far enough in the game. Participant 3 felt that if she had gotten further, she probably could have learned more:

Interviewer: Does playing this [the game] teach you anything about World War II?

Participant 3 (“player”, “only high school history”): I am sure it will, if I can pass the task. [Then] I will learn more. The more I play, the more I can learn about the war.

Participants 1 (“gamer”, “only high school history”), 7 (“player”, “some postsecondary history”) and 9 (“gamer”, “some postsecondary history”) expressed similar ideas, and there is some justification for them. As the levels of MoHF advance, the player is assigned further missions based on historical events. In level 2.2, the player’s mission is to steal an Enigma code book, a document that was used by the German forces (together with an Enigma machine) to encrypt and decrypt secret messages. In level 6.1, the player must steal plans for the Horten IX, which was an advanced German jet fighter/bomber produced late in the war. However, despite integrating such factual details, MoHF’s level designs also include activities that are either not historically accurate, or are unrealistic. Thus, while it is possible for a player to gain some valid knowledge about World War II from more advanced levels, he or she would need to carry out research outside the game environment to differentiate factual elements from invented ones. Participants’ interest in doing such research was meaningful, but limited. For example during his postgame interview, Participant 2 volunteered a story about how he had pursued an interest based on a similar game:

Interviewer: Does playing this game make you more interested in history at all?

Participant 2 (“gamer”, “only high school history”): It does…. A similar game to Medal of Honor is Battlefield, and there is a character named “General Rommel” and [I found out that] he was a general in the actual war as well.

Passages similar to this were rare in our interviews, suggesting that for most participants, playing MoHF did not encourage them to study historical events outside the context of the game itself.

Question 2: How Trustworthy Did Participants Consider MoHF as a Source of Knowledge about the Past?

The ideas expressed by participants about gameplay as a source of historical knowledge appeared closely tied to their appreciation for the historical realism of MoHF. Generally speaking, participants were suspicious of the game’s historical realism if they knew little about the events depicted in the game. Participant 4 presents a view that was typical of those with only high school history:

Interviewer: So what does this [the game] teach you about history?

Participant 4 (“gamer”, “only high school history”): I guess the basic...the basic things of history. [The game designers] try to go for the most known basic history for the game….

Interviewer: How deep do you think they get into it?

Participant 4: Probably not that deep. They try to work on the entertainment more than the history because...you hear that history is boring but you have to learn it as part of the [school] curriculum. A lot of the game designers probably felt that way...it is like, “we should add in more special effects, more entertainment to make it more fun.” Then more people buy it.

Note the speculative tone of this passage. This tone was echoed by 5 other participants, who could not decisively claim that the game was unrealistic (given their own limited knowledge of the relevant past events), but could not see a clear reason to believe otherwise. Only Participant 12 was enthusiastic about the realism of the game. Despite recognizing trade-offs between historical realism and the playability of the game, he viewed MoHF as akin to a historical reenactment:

Participant 12 (“gamer”, “some postsecondary history”): Well I think it allows you to connect with this historical event. Even in a very shallow way you can relive what happened, and get maybe the closest sense that you’re ever going to really get about what it [was] like to be there. It is kind of like how people do historical reenactments. There is no threat, there is nothing at risk, but you still get a slight glimpse of what this may have been like.

Participant 12 was alone in his enthusiasm for MoHF’s depiction of D-Day, but six other participants stated in a more general way that MoHF provided them with a sense of “what war was like”. Thus, there was evidence that some participants believed the experience of playing MoHF helped them to develop empathetic understanding, even if the game design filtered out important elements of real war, as discussed by Pötzsch (2015) and others.

Question 3: How Did Participants Make their Judgements about the Trustworthiness of MoHF as a Source?

Why did participants with little historical knowledge to gauge the design of the game against nonetheless dismiss it as a trustworthy source? Two possible explanations appealed to us based on our analysis of the full dataset. The first was that participants’ judgements were shaped by the assumed influence of the profit motive on the game maker’s representation of the past. Six of the twelve participants explicitly linked their speculations about the historical accuracy of MoHF’s representations with the maker’s commercial interest. Take Participant 9 for example:

Participant 9 (“gamer”, “some postsecondary history”): I would imagine that the historical accuracy of a video game is not as important to [potential buyers] as the entertainment value, so the selling point...that’s why I am guessing it’s...that’s why I imagine [the game] is less historically accurate [than other sources].

Other reasons why participants were suspicious about the historical realism of MoHF related to the game’s obviously unrealistic health system (ie., the health meter and medkits), and the percieved lack of gore in the game. Participant 11, for example, did not feel that the game realistically depicted war, because the graphical depiction of violence had been unrealistically limited to obtain a particular Entertainment Software Ratings Board (ESRB) rating. By not including a more realistic level of gore that would require a “Mature” rating, MoHF could reach a larger market:

Participant 11 (“gamer”, “some postsecondary history”): Of course the game is rated “Teen”, so it is kind of a cleaned up.... There is not a lot of…violence in terms of blood and gore and that kind of thing.

It was clear to every participant that their character, Jimmy Patterson, had a superhuman tolerance for bullets and a magical ability to be instantly healed with medkits. Four of the twelve participants remarked on the fact that the unrealistic health system extended gameplay at the expense of realism. For example, Participant 8 described the medkits as “expected” and explained what the consequences would be if the health system was more realistic:

Interviewer: In what ways are [the medkits] expected?

Participant 8 (“gamer”, “only high school history”): You know you are hurt and about to die. I am expecting that somewhere along the way I’m going to find something or somebody that is going to be able to heal me.

Interviewer: Why?

Participant 8: Because I hardly got through the first part of the game even with finding the [medicinal] canteens. I think it would make the game really unplayable and insanely difficult [if the medkits were not there].

The lack of realism in such visible aspects of the game’s design made some participants skeptical about the realism of any part of it. Six participants expressed the view that for these and other reasons, nonfiction books or documentary films were better sources of historical knowledge than games, because nonfiction books and documentaries are designed more exclusively to inform. Take Participant 12 for example:

Interviewer: How would you compare the historical accuracy of a book, a documentary and a videogame?

Participant 12 (“gamer”, “some postsecondary history”): Well a book and a documentary, depending on the sophistication...I think you can be pretty close [to accurate]. A book is probably the best because you can say so much more in a book than you can in a documentary. I think a documentary would get weighed down if it had all the facts of a book. A game I would say is definitely at the lowest level.

Interviewer: Why?

Participant 12: Well beneath those two, you can’t relate...a game is a game. A game is meant for...not that history isn’t entertaining, but again [the game] is more visceral I think. You are supposed to be accomplishing more [in a video game] whereas a documentary or book can strictly be about facts.

We note that in this passage, Participant 12 ignores entirely the fact that book authors and filmmakers also have commercial interests. This surprised and puzzled us as researchers, but Participant 12’s views were shared by others with less formal study of history. Participant 4, who had only studied history at the high school level, expressed similar ideas, arguing that nonfiction books would be more historically accurate than videogames because videogames twist history to suit the priorities of gameplay:

Participant 4: Honestly, I would stick with the books. The games can alter anything, but you cannot alter history (sic).

In relation to prior findings on the trustworthiness of various sources of knowledge about the past (Conrad et al., 2013; Rosenzweig & Thelen, 1998), it is clear that for our participants, video games represented the bottom rung of the trustworthiness ladder, after documentary films and nonfiction books.

Limitations of the Study

This study has several important limitations. Firstly, due to the way in which our study was advertised, participants self-selected who were interested in videogames. As a result, our sample did not include any participants who typically avoid games.

Secondly, by carefully constructing our participant group based on a screening survey, we strove to include as wide a range of gaming experience and formal history background as possible. By virtue of this method, our study cannot claim to represent the prevalence of the various ideas we discuss among the population of young adults as a whole. The screening survey and advertisements for the study also made participants aware that history would be an important theme of our study. This awareness might have colored participants’ engagement with MoHF and their responses to our interview questions.

Relatedly, because our study relied heavily on pre-scheduled observation and interviews, it is possible that Hawthorne effects (Merrett, 2006) were at play in our findings. Due to the methods we employed, we have no way of determining whether participants were consciously or unconsciously performing to what they believed were our expectations.

The genre of game that our participants played also presents a limitation. Each genre of game has different mechanics, and though the first-person-shooter game we chose (MoHF) had advantages for our brief study, it is not comparable in every way to the lengthier and more complex strategy games (such as Civilization) that other studies have focused on. Further, our participants played MoHF for a short time compared to players who purchase it (perhaps hundreds of hours). It is certainly possible that participants would have seen more potential in MoHF as a source of historical knowledge if they had been permitted to play it for a longer time. Practical limitations prevented this.

Lastly, MoHF was clearly a dated game at the time the study was conducted. It is possible that participants did not find it as captivating as they would have found a more recent game title, and that in ways they did not articulate during the interviews, our participants viewed MoHF as less capable of realistically capturing a complex historical situation than a more modern title would have been. Acknowledging these issues, we observed that all of our participants appeared to have played MoHF with enjoyment. More importantly, given that part of our participants’ scepticism of MoHF’s historical accuracy was based on the developer’s commercial interest, it seems plausible that a more current, more actively-promoted game title would have been greeted with even greater scepticism as a potential source of historical knowledge.

Discussion

For decades scholars have examined the general public’s engagement with history, placing particular focus on the relative degrees of trust we place in various sources of knowledge about the past, such as museums, historic sites, documentary films and nonfiction books (Rosenzweig & Thelen, 1998; Conrad et al., 2013). Despite the popularity of videogames set in the past, their place in the public’s “trust hierarchy” has not been directly investigated. Further, while the relationship between players’ experiences in history games and the “real” past has been considered theoretically (Kingsepp, 2006, 2007; Hong, 2015; Schut, 2007), the field is overdue for an empirical examination of how people who have not been trained to critique a history game’s representation of the past actually think about it.

Our study is a first step in building an empirical knowledge base about both where the public situates history games in their trust hierarchy relative to other sources, and how people reason about the trustworthiness of a particular history game. In this last connection, the findings shared above may hold unpleasant surprises for some researchers. Educational research on history games, in particular, has largely been driven by the hope that they would be motivational for youth; but it has also revealed the difficulty of getting young people to take games seriously as learning resources. McMichael, for instance, remarked that “[m]any of my students complained about having to play PC games as coursework…. This was an interesting and totally unexpected phenomenon” (McMichael, 2007, p. 214). Our findings suggest that such reactions may be due partly to the fact that while they find historical games engaging, players are not necessarily able to understand them as potential sources of knowledge about the past. Indeed, several of our participants seemed stridently against the possibility that a videogame could be a legitimate source of such knowledge.

As scholars, we value experiential learning enough to recognize how little our participants appeared to value it. For most, their understanding of what it meant to learn about the past appeared to have been completley colonized by their experience of learning history in school. Indeed, it seemed as though most of our participants didn’t believe they could be learning about the past unless the computer was directly telling them verifiable “facts”. Yet while they were overtly dismissive of MoHF as a source of knowledge about the past, our participants did seem to care about its historical realism -- counter to what other scholars have implied (e.g. Hong, 2015). Rather than considering our questions about the realism of the game to be absurd, pointless or naïve, they took the questions at face value.

Even when our participants dismissed the historical realism of MoHF (as most did), this did not imply that they felt well informed about the historical situations or events depicted in it. The opposite was true for half of our research participants. When they lacked the historical knowledge required to critique MoHF’s representation of the past, our participants did not suspend judgement, but reasoned about the game’s trustworthiness in two main ways. The first way was to identify specific game features that appeared unrealistic, and take these as indicative of the developers’ approach to historical realism. For example, the presence of medkits and absence of gore were taken as evidence that MoHF did not realistically depict war. The other way in which participants reasoned about the trustworthiness of MoHF as a representation of the past was to try to imagine the motives that commercial game developers would have for working hard (and spending money) to achieve historical realism. If they could not readily imagine such motives, participants felt justified in assuming that the game characters, scenarios, and settings were fabricated. This reasoning assumed that fabrication would be less expensive than historical research. While those familiar with game development might argue this assumption to be false, the important point is that our participants’ thinking was driven by their keen awareness of the videogame as a money-making product. In comparative terms, they placed greater trust in documentary films and nonfiction books as sources of knowledge of the past, perhaps because they were less aware of the influence of the profit motive in the production and marketing of these media, assumed profits to be lower in these industries, or reasoned that publicly-financed media were more trustworthy on historical matters than privately-financed ones.

We see two possible sets of implications from these findings -- one for educators, the other for developers and enthusiasts of history games as sources of historical knowledge outside of school settings. Firstly, in order to work successfully with commercial history games as teaching resources, it seems likely that instructors will need to address the ways in which specific features of each game (for example, MoHF’s health system) should be understood with regard to what they do and do not suggest about its historical realism. The fact that young people play a history game well and with enjoyment does not imply that they understand or respect it as a potential historical source -- regardless of the informed respect that scholars may have for it as such. Substantial guidance may be necessary to help students appreciate any game as a source, and this may necessitate rehabilitating the very idea of experiential learning in students’ minds.

Secondly, our study suggests that the appreciation of commercial games as potential sources of historical knowledge may be strongly limited by the public’s level of awareness that they are commercial products. For some enthusiasts, commercial history games are attractive as a way of informing the public about the past precisely because these games have attracted a high level of investment, and have high production values. Yet these very qualities appeared to make our participants suspicious of the trustworthiness of a game as a source of knowledge about the past. If our findings are reinforced by future research, it will prove a disappointment to enthusiasts of games for history learning. If a dated game like MoHF is dismissed as a source on the grounds of the developers’ profit motive, it is possible that more current and actively-promoted history games may be the most likely to be dismissed.

Endnotes

[1] As a player, the first author recalls being killed at least ten times before discovering which objects provided safe cover.

References

Angvik, M. & von Borries, B. (1997). Youth and History: A Comparative European Survey on Historical Consciousness and Political Attitudes among Adolescents. Hamburg: Körber-Stiftung.

Ashton, P. & Hamilton, P. (2003). At Home with the Past: Background and Initial Findings from the National Survey. Australian Cultural History, 22:1, pp. 5--30.

Ball, M. & Smith, G. (2011). Technologies of Realism? Ethnographic Uses of Photography and Film. In P. Atkinson, A. Coffey, S. Delamont, J. Lofland, & L. Lofland (Eds.), Handbook of Ethnography (pp. 302--319). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Barton, K.C. & Levstik, L. (2003). Why Don’t More History Teachers Engage Students in Interpretation? Social Education, 76:7, pp. 358--361.

Bennett, S., Maton, K., & Kervin, L. (2008). The ‘Digital Natives’ Debate: A Critical Review of the Evidence. British Journal of Educational Technology, 39:5, pp. 775--786.

Conrad, M., Ercikan, K., Friesen, G., Létourneau, J., Muise, D., Northrup, D., & Seixas, P. (2013). Canadians and Their Pasts. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Corbin, J. (2008). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

Davis, O.L., Yeager, E.A., & Foster, S.J. (2001). Historical Empathy and Perspective Taking in the Social Studies. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

EA Games (2002). Medal of Honor: Frontline [Playstation 2]. Redwood City.

Gee, J.P. (2003). What Video Games Have to Teach Us about Learning and Literacy. New York: Palgrave Macmillian.

Galloway, A.R. (2006). Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Guinness World Records Limited (Ed.). (2008). Guinness World Records Gamer’s Edition 2008. London: Guinness World Records Limited.

Helsper, E.J. & Eynon, R. (2010). Digital Natives: Where Is the Evidence? British Educational Research Journal, 36:3, pp. 503--520.

Hong, S. (2015). When Life Mattered: The Politics of the Real in Video Games’ Reappropriation of History, Myth, and Ritual. Games and Culture, 10:1, pp. 35--56.

Johnson, M. (2004, March 13). Medal of Honor: Frontline [Game Review] Retrieved January 31, 2014 from http://games.monstersatplay.com/review/playstation2/medal_of_honor_frontline.php.

Kingsepp, E. (2006). Immersive Historicity in World War II Digital Games. Human It, 8:2, pp. 60--89.

--------- (2007). Fighting Hyperreality with Hyperreality History and Death in World War II Digital Games. Games and Society, 2:4, pp. 366--375.

Lee, J.K. & Probert, J. (2010). Civilization III and Whole-Class Play in High School Social Studies. The Journal of Social Studies Research, 34:1, pp. 1--28.

Levstik, L.S. & Barton, K.C. (1997). Doing History: Investigating with Children in Elementary and Middle Schools. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

McCall, J. (2011). Gaming the Past: Using Video Games to Teach Secondary History. New York: Routledge.

McMichael, A. (2007). PC Games and the Teaching of History. The History Teacher, 40:2, pp. 203--218.

Merrett, F. (2006). Reflections on the Hawthorne Effect. Educational Psychology, 26:1, pp. 143--146.

Metzger, S.A. & Paxton, R.J. (2014). Playing in the Past: A Framework for History-Oriented Video Games. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Philadelphia, PA.

National Center for History in the Schools (Ed.). (1996). National Standards for History. Los Angeles: National Center for History in the Schools.

Pagnotti, J. & Russell, W.B.I. (2012). Using Civilization IV to Engage Students in World History Content. The Social Studies, 103:1, pp. 39--48.

Peck, C. & Seixas, P. (2008). Benchmarks of Historical Thinking: First Steps. Canadian Journal of Education, 31:4, pp. 1015--1038.

Polanyi, M. (1962). Tacit Knowing: Its Bearing on Some Problems of Philosophy. Reviews of Modern Physics, 34:4, pp. 601--616.

Pötzsch, H. (2015). Selective Realism: Filtering Experiences of War and Violence in First- and Third-Person Shooters. Games and Culture, pp. 1--23. doi: 10.1177/1555412015587802

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. On the Horizon, 9:5, pp. 1--6.

Rideout, V.J., Foehr, U.G., & Roberts, D.F. (2010). Generation M2: Media in the Lives of 8- to 18-Year-Olds. Menlo Park, CA: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved Nov. 23, 2016 from http://kff.org/other/event/generation-m2-media-in-the-lives-of/

Rivers, T. (2002). Medal of Honor Frontline Video Review. [Game Review] Retrieved January 31, 2014 from http://www.gamespot.com/ps2/action/medalofhonorfrontline/video/2868770.

Rosenzweig, R. & Thelen, D. (1998). The Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life. New York: Columbia University Press.

Schulzke, M. (2013). Refighting the Cold War: Video Games and Speculative History. In A.B.R. Elliott & M.W. Kapell (Eds.), Playing with the Past: Digital Games and the Simulation of History (pp. 261--275). New York, NY: Bloomsbury.

Schut, K. (2007). Strategic Simulations and Our Past: The Bias of Computer Games in the Presentation of History. Games and Society, 2:3, pp. 213--235.

Shaffer, D.W., Squire, K.R., Halverson, R., & Gee, J.P. (2005). Video Games and the Future of Learning. Phi Delta Kappan, 87:2, pp. 104--111.

Šisler, V. (2008). Digital Arabs: Representation in Video Games. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 11:2, pp. 203--220.

------. (2009). Palestine in Pixels: The Holy Land, Arab-Israeli Conflict, and Reality Construction in Video Games. Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication, 2:1, pp. 275--292.

Spielberg, S. (Director). (1998). Saving Private Ryan. Universal City, CA: DreamWorks Distribution.

Squire, K. & Barab, S.A. (2004). Replaying History: Engaging Urban Underserved Students in Learning World History Through Computer Simulation Games. Paper presented at the International Conference of the Learning Sciences, Los Angeles, CA.

Statistics Canada. (2004). Census at School. Retrieved from www19.statcan.ca.

verbi Software. (2011). Maxqda. Marburg: verbi Software. Retrieved February 2, 2012 from www.maxqda.com.

Watson, W.R., Mong, C.J., & Harris, C.A. (2010). A Case Study of the In-Class Use of a Video Game for Teaching High School History. Computers & Education, 56:1, pp. 466--474.

Wineburg, S. (1991). On the Reading of Historical Texts: Notes on the Breach between School and the Academy. American Educational Research Journal, 28:3, pp. 495--519.