The New Lara Phenomenon: A Postfeminist Analysis of Rise of the Tomb Raider

by Janine EngelbrechtAbstract

Lara Croft, the heroine of the popular Tomb Raider videogame franchise, is a representative of femininity in contemporary popular culture. The rebooted Tomb Raider game trilogy, released from 2013-2018, presents a new version of Lara Croft, who is a departure from the postfeminist action heroine archetype that Lara Croft exemplified before the character’s reboot in 2013. Some aspects of Lara Croft’s characterisation that have changed are her wardrobe, her body shape, and the character’s emotional complexity. Moreover, Lara Croft’s narrative now includes a particular focus on her relationship with her deceased mother, and ludological elements of the game change the way in which Lara Croft navigates her environment. This paper argues, through an analysis of the Tomb Raider reboot (Square Enix, 2013) and Rise of the Tomb Raider (Square Enix, 2015), that the new version of Lara Croft, who appears in the three most recent Tomb Raider games, presents a different version of female heroism than that of the older version of Lara Croft, and that this new heroine archetype is replicated in representations of other contemporary heroines in AAA videogames.

Keywords: Postfeminism, videogames, ludology, narratology, Lara Croft, Tomb Raider, action heroine.

Introduction

The representation of women in the media is recently under more scrutiny than ever, as the industry is starting to acknowledge that women have been portrayed in negative ways fueled by patriarchal and misogynistic ideals for decades (Curtis, 2017). Although sexist representations of women in the media remain ever-present, some efforts are being made to challenge these portrayals of women and they yield positive (although still limited) results (Curtis, 2017). For example, recently even the age-old Disney princess narratives, that have deeply embedded patriarchal narratives, have been rewritten: a kiss from the female villain replaces the princesses’ kiss from a male ‘knight in shining armour’ in Maleficent (Stromberg, 2014), and Beauty and the Beast (Condon, 2017) features a rebooted Belle, played by self-proclaimed feminist activist, Emma Watson.

Moreover, women’s absence in key positions in the entertainment industry is also being questioned. The #MeToo movement has recently put a new spotlight on women’s rights in the entertainment industry, and more films with female directors, such as the celebrated Wonder Woman (2017) film directed by Patty Jenkins, are being released on the big screen. In the videogame industry, the pay gap between male and female developers, and the lack of female developers in senior positions, for example, have also become central issues (Makuch, 2018). Many of these debates are manifested in discussions surrounding videogame heroines, and in particular, Lara Croft, who is the heroine of the long-standing Tomb Raider videogame series.

Since the game’s creation in 1996, Tomb Raider, including its sequels and various spin-offs, has sold at least 58 million copies worldwide (Videogame Sales Wiki, n.d). Its main protagonist, Lara Croft, has become a significant popular culture icon who has had a powerful influence on gaming and popular culture since her creation. In addition to videogames, Lara Croft has starred in three feature films, and she is more popular than any super model in the world, having appeared on the covers of over 1200 magazines by 2016 (Arrojas, 2016).

Lara Croft has been in 20 Tomb Raider games to date, including the game’s spin-offs. In the three most recent games starring Lara Croft, namely Tomb Raider reboot (TR reboot) (Square Enix, 2013), Rise of the Tomb Raider (ROTTR) (Square Enix, 2015) and Shadow of the Tomb Raider (SOTTR) (Square Enix, 2018), Lara Croft’s signification has changed significantly from her former incarnations, to which I refer as “old Lara”. I argue that the new version of Lara Croft (to which I refer as “new Lara”), who appears in the three most recent Tomb Raider games (and in the 2018 Tomb Raider film), presents a different version of female heroism than that of old Lara, and that this new heroine archetype, exemplified by new Lara, is replicated in representations of other contemporary heroines in videogames.

This paper aims to examine new Lara as an action heroine based on her appearances in mainly TR reboot (Square Enix, 2013) and ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015). First, I provide a brief overview of postfeminism and review predominant theorisations of old Lara in order to illustrate the ways in which she exemplifies the postfeminist ‘supergirl’ archetype outlined by Stephanie Genz (2009). I then show through an analysis of the ludological and narratological elements of TR reboot (Square Enix, 2013) and ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015) in what ways the representation of new Lara moves away from the postfeminist ‘supergirl’ ideal. Finally, I briefly indicate that other videogame heroines that resemble the representation of new Lara are also starting to emerge, especially after 2013 -- what I term “the new Lara phenomenon.”

Postfeminism and Old Lara

A branch of feminism that is useful for theorising a character such as (old) Lara Croft is postfeminism. Although “postfeminism has [not] been [formally] defined,” a characteristic it shares with postmodernism (Coppock, Haydon & Richter, 1995 in Gamble, 2001, p.43), it provides a useful theoretical framework for the study of the early version of Lara Croft, who, herself, embodies the ambiguities and contradictions inherent in the postfeminist identity. Although a thorough investigation of feminism is beyond the scope of this paper, in this section I briefly explore the various (and at times, conflicting) positions on postfeminism and its relation to other feminisms.

For Sarah Gamble (2001), with its emphasis on individualism and choice, postfeminism is a backlash against the ground gained by second wave feminism, which was primarily concerned with the collective feminist struggle for equality. In retrospect, the ‘second wave’ feminist consciousness can be considered to have begun in the late 1960s and early 1970s, after approximately five decades of dormancy for feminism (Bailey, 1997, p.19). As a continuation of first wave sentiments, second wave feminism became concerned with issues such as rape and sexuality, as well as race and class (Bailey, 1997, p.20). At the turn of the century, however, young feminists felt that second wave feminism’s emphasis on collective histories and political correctness was not relevant to the late-capitalist context of the latter part of the twentieth century (Bailey, 1997), and some branches feminism, rather disconcertingly, took a turn towards an embrace of individualism and consumerism as a means of female emancipation (Stasia, 2007).

To the extent that both are concerned with popular culture and the contradictions that women faced at the end of the twentieth century, postfeminism can thus be viewed as a branch of third wave feminism (Stasia, 2007). Postfeminism is simultaneously though, according to Stephanie Genz and Benjamin Brabon (2009), in direct antithesis to the third wave, as it is often found criticising and undermining second wave feminist theory and activism, which is understood to nevertheless have strong affiliations with that of the third wave, even though it often claims not to. In the same vein, Christina Stasia (2007, p.239) acknowledges that “unlike third wave feminism...postfeminism rejects the institutional critique made by second wave feminism.” Although this is a limited account of the complexity regarding postfeminism’s relationship with feminism, it is evident from these discussions that there is in fact no singular definition for postfeminism and that it has a complicated relationship with its feminist ancestors.

For Angela McRobbie (2004, p.255), while “engaging in a well-informed and well-intended response to feminism,” postfeminism can simultaneously be considered an attempt to undo feminism. As I show in the discussion of old Lara and postfeminism, the fact that postfeminism rejects institutionalised critique, reinscribes sexualised images of women in the media with notions of female emancipation, and ultimately fails to break free from the narrow confines of individualistic self-optimisation and market relations, leads me to question its validity as a feminist enterprise. While claiming to be a critical stance, in my estimation, postfeminism rather fuels the manifestation of a particular, and what I deem a problematic, view of what it means to be an ‘emancipated’ woman in twenty-first century post-industrial society in popular culture.

Postfeminism is arguably located within a specific time and place in history: the late twentieth century and early twenty-first century in Europe and America in which consumer, middle-class aspirations play a key role (Genz, 2006; McRobbie, 2004). Postfeminism is in this way directly linked to the increasing importance of the media and consumer culture in the late 1990s, where second wave feminism’s collective activist struggle was being replaced with “individualistic assertions of (consumer) choice and self-rule” (Genz, 2009, p.85). Michelle Lazar (2009, p.372) succinctly terms postfeminism’s emphasis on choice and self-rule an “entitled femininity,” where (white, middle-class) women are supposedly and unproblematically “entitled to be pampered and pleasured, and to unapologetically embrace feminine practices and stereotypes” as a feminist endeavour.

Postfeminist choice, therefore, perplexingly involves the adoption of consumerism and capitalism as a feminist strategy, and the postfeminist woman is encouraged to use her sexuality and femininity as “both active and passive forms of recognition and motivation” and agency, and her consumer capacity as a form of self-expression (Genz 2006, p.337-339; Genz & Brabon 2009, p.24). Moreover, Stasia (2007, p.238) importantly observes that postfeminist women are convinced that “they live in a post-patriarchy” society where feminism is no longer relevant, which in my view results in postfeminism embracing the very patriarchal ideologies that it aims to dismantle.

Swinging nude on a wrecking ball in her music video for Wrecking Ball as symbolic of her control over her own sexuality, popular culture icon Miley Cyrus is a prime example of postfeminist female ‘empowerment’ and its ultimate failure to address structural issues that constitute ‘free choice’. Cyrus’s antics in the media -- the various nude images of her available on the Internet, and the ways in which she endlessly presents herself in sexualised terms -- perfectly exemplify Angela McRobbie’s (2004, p.258-259) critical assessment of the paradoxical premises on which postfeminist empowerment is based. To elaborate, postfeminism claims that women such as Cyrus are active subjects and their provocative display, as is seen in Wrecking Ball, which undeniably frames them as the object of the “male gaze” (famously theorised by Laura Mulvey (1975)), should not be interpreted as “[enacted] sexism” (McRobbie’s 2004, p.258-259), even though it openly invites the (male) viewer to objectify them. Instead, postfeminism argues that as long as she is doing it “out of choice,” a ‘sexually liberated’ and financially independent woman such as Cyrus, even though swinging on a phallic symbol in the nude, is an active and ‘empowered’, and therefore feminist, subject (McRobbie’s 2004, p.258-259). This is perhaps one of postfeminism’s greatest discrepancies, and one of the prime reasons why I agree that it can even be considered ‘anti-feminist’, as it appears to justify almost anything that women do, as long as they do it out of their own choice.

Genz (2009) further identifies different types of twenty-first century postfeminist representations of women in popular culture. One such postfeminist femininity that Genz (2009) describes is ‘the supergirl’, who is the modern-day action heroine that problematises “passive femininity and active masculinity in terms of diametrical opposition and mutual exclusivity” (Genz, 2009, p.152). Significantly, the late twentieth century, in which postfeminism gained prominence, is also the era in which Lara Croft first appeared, along with other young, ‘girly’ heroines in videogames, film and television. Stasia (2007, p.237) lists a number of action heroines in film that could be considered ‘supergirls’, namely Charlie’s Angels (McG, 2000), Miss Congeniality (Petrie, 2000), Elektra (Bowman, 2005), and Aeon Flux (Kusama, 2006), to name only a few. In videogames, Cereza from Bayonetta (2009) and Rayne from BloodRayne (2002) could also be read as ‘supergirls’.

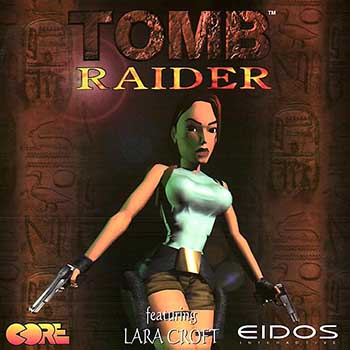

Lara Croft -- in her old manifestation -- is another popular ‘supergirl’. In an interview with Face magazine in 1997, Toby Gard, Lara Croft’s creator, claimed that Lara is neither a feminist icon nor a sexist fantasy, but is more accurately a bit of both: “strong independent women are always the perfect fantasy girls -- the untouchable is always the most desirable” (Mikula 2003, p.79). Gard’s description of old Lara perfectly exemplifies the flaws inherent in the postfeminist identity, as women consume images of themselves that blatantly perpetuate sexist stereotypes; as is also seen in the discussion of Miley Cyrus, and re-inscribe these images with concepts of female empowerment. Figure 1 shows the earliest incarnation of old Lara, who is an iconic postfeminist ‘supergirl’.

Figure 1. Tomb Raider box art, 1996. (Stella’s Tomb Raider Site).

According to Genz (2009), the postfeminist ‘supergirl’ adopts certain characteristics traditionally associated with masculinity as a means of empowerment, such as strength and action, yet, as is seen in Figure 1, not only maintains, but displays exaggerated physical ‘feminine’ attributes. The ‘supergirl’ therefore “performs a paradoxical cultural function as she both contests and reaffirms normative absolutes and stereotypes,” being both a feminist icon and a patriarchal token (Genz, 2009, p.154). For some feminists, on the one hand, Lara Croft is nothing more than a male fantasy, as she was created by a man (arguably to appeal to the predominantly male gamer demographic at the time), her body is idealised and sexualised, and the third person camera angle allows the (male) player to constantly see Lara’s body in full view from behind (Mikula, 2003; 2004). Lara’s violence also appeals mainly to male players who are invited to simultaneously identify with her and objectify her (Mikula, 2003; 2004).

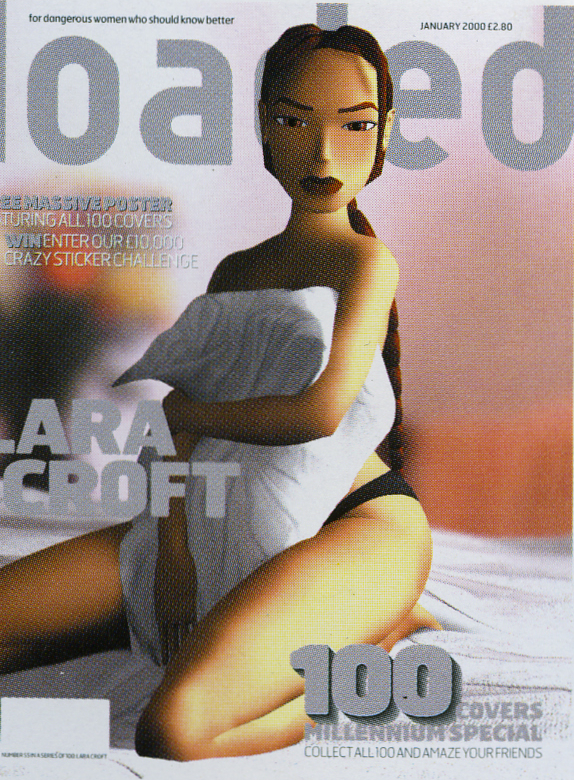

On the other hand, some (post)feminists celebrate old Lara as a feminist icon and instead view her idealised body as a symbol of power and self-control, as she uses it to fight (Mikula 2004). Moreover, there is no indication of Lara’s hetero- or homosexuality, which allows fans to reconstruct her identity indefinitely on various fan forums and blogs (Mikula, 2004). Old Lara’s primary subversive potential therefore lies in the fact that she is an empty signifier, which can be(come) anything that consumers want her to be (Mikula, 2004), and thus opens up the possibility of ‘feminist’ appropriation of the character. This aspect of old Lara is, however, not as subversive as (post)feminist readings of her assume it to be. The combination of Lara’s translatability and her sexualised body has undeniably made her easier to objectify instead of subverting the objectification of the digital female body; as is seen in Figure 2 which shows only one instance of how old Lara is often appropriated to satisfy of the male gaze. In this way, as it is with Miley Cyrus, old Lara’s (and by extension, postfeminism’s) use of sexuality and femininity as a strategy for emancipation proves to be counter-productive.

Figure 2. Lara Croft on the cover of Loaded magazine, 2000. (Flickr, 2011).

Stasia (2007, p.244) identifies more characteristics of the postfeminist ‘supergirl’ based on Lara’s portrayal in the 2001 Tomb Raider film. In the film, Lara is hyperfeminised and shots focus on Angelina Jolie’s (fake) breasts, thighs and hips. Lara is “young and girlish,” and she sells “traditional notions of women’s power” as she always returns to the private sphere even though she has mobility in the public sphere (Stasia, 2007, p.244). Despite this, Helen Kennedy (2002) affirms though that the transgressive stunting body described by Mary Russo (1994), where female figures “undermine conventional understandings of the female body” by performing extraordinary deeds, is also replicated in the figure of Lara. In both the Tomb Raider films, and the Tomb Raider videogames, Lara Croft inhabits a hostile, masculine environment not traditionally associated with the feminine private or domestic space and she rejects patriarchal norms (Kennedy, 2002).

In this way, Lara, as a postfeminist ‘supergirl’ is a liminal character who exists between extremes. She is simultaneously masculine and feminine, human and monster, good and evil, and feminine and feminist (perhaps viewing ‘feminine’ and ‘feminist’ as binary opposites is symptomatic of postfeminism’s disavowal of second wave feminism) (Genz, 2009). Importantly, as a ‘supergirl’, old Lara is both beautiful and strong, claiming her femininity as a source of strength, which is a tactic that postfeminism uses to infuse “old signifiers of ... helpless femininity with new meanings of strength and agency” (Genz, 2009, p.157). Consequently, sexualisation and feminisation (along with supposed empowerment and agency) are important ingredients of the potent cocktail that is the postfeminist ‘supergirl’ and old Lara (Genz, 2009), who is ultimately unthreatening because she is the impossible ideal (Stasia, 2007).

Lara has also been discussed alongside 1990s femme fatales in film (also see Kennedy, 2002). In summary, the femme fatale is sexually attractive and dangerous to the male hero as she is unknowable, mysterious and self-centred (Waltonen, 2004). According to Amanda Du Preez (2000, p.21), Lara shares characteristics of the archetypal femme fatale, who subverted gender norms in the 1940s, in the sense that “[Lara] is beautiful, but out of reach” and “she seduces without giving herself.” Old Lara’s untouchability and aloofness is reminiscent of the femme fatale, as well as the fatale’s indifference to the male gaze, as Lara is “oblivious to obnoxious perverted behaviour” by male players (Du Preez, 2000, p.23).

Formal analyses of Lara as a representative of the postfeminist ‘supergirl’ have mostly been done on the Tomb Raider films released in 2001 and 2003, but Kim Walden (2004) provides an account of videogame heroines’ influences on film heroines. Walden (2004, p.81) observes that ‘film Lara’ mimics ‘videogame Lara’, so she is thoroughly “a representation of a representation” who has no immediate real-world referent. In other words, old Lara is a heroine who is created from a combination of media “vernaculars” (Walden, 2004, p.87). Interestingly, after the release of the two Tomb Raider movies that starred Angeline Jolie as Lara, Lara’s representation in the Tomb Raider games started adopting Jolie’s appearance.

Bob Rehak (2003) elaborates on the complicated relationship between Lara and real-life Lara Croft models: Rhona Mitra was fired as a Lara Croft model when Mitra claimed in an interview that she is Lara. Thereafter, Eidos (the developer from 1996 to 2003) attempted to maintain Lara’s multiplicity -- which is her simultaneous existence on various platforms -- by instructing Lara Croft models after Mitra to always refer to Lara in the third person (Polsky 2001 in Rehak 2003). Ironically, after the release of the Tomb Raider films, this relationship became inverted as Lara in Tomb Raider and the Angel of Darkness (2003) up to Tomb Raider Underworld (2008) adopted the appearance of Jolie (Rehak 2003).

What this illustrates is Lara’s translatability (Walden, 2004). According to Rehak (2003), Lara’s celebrity status and vast fandom subversively blur the lines between producers, texts, audiences and technologies as Lara is capable of “cloning herself from one media environment to another and maintaining simultaneous existences in each” (Rehak, 2003, p.481). Angelina Jolie, to some extent, made Lara more ‘real’ for fans, especially since Lara Croft started to resemble Jolie in subsequent Tomb Raider games, but this ironically did not significantly hinder old Lara from migrating between different media environments. For Mary Flanagan (1999), these characteristics, amongst others, contribute to Lara Croft’s status as the first digital star in history. According to Flanagan (1999) the digital star system (as opposed to the cinematic star system) questions signifiers, identities and the bodies themselves; as these bodies are not only looked at, but also controlled by the player. The representation of this body addresses “the particular place of gender in these embodiment relationships” and provides the potential for the subversion of traditional notions of gender (Flanagan, 1999, p.84).

Clearly, old Lara is a multi-faceted character and her status as a feminist character is highly ambiguous. Old Lara’s representation is, like postfeminism, simultaneously problematic and subversive. In my estimation, most of the definitions of postfeminism that have been discussed can be applied to old Lara, but I argue are not to new Lara. Since new Lara is not overtly sexualised and feminised, which are central aspects of the postfeminist ‘supergirl’, few of the characteristics of the postfeminist sexual agent apply to her. Next I elaborate on postfeminism in relation to new Lara and through a close analysis of TR reboot (Square Enix, 2013) and ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015) I attempt to determine where new Lara is situated on the postfeminist continuum.

New Lara and Rise of the Tomb Raider

In 2013, Lara Croft underwent a major representation makeover in TR reboot (Square Enix, 2013) (Figure 3), which she has maintained in the subsequent games, ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015) and SOTTR (Square Enix, 2018). To my knowledge, only two academic articles that address ‘new Lara’ exist, which I first review as a foundation for the analysis of ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015). Hye-Won Han and Se-Jin Song’s (2014) analysis of TR reboot (Square Enix, 2013) focuses specifically on Lara Croft’s narrative as a female hero. Han and Song (2014) acknowledge that Lara’s superficial appearance is an improvement on earlier versions, however, they contend that emphasis is still not placed on Lara’s unique features as a female hero. Instead, Han and Song (2014) argue, Lara still models characteristics stereotypical of all heroes. Han and Song (2014) further argue that in male-hero narratives, other female characters often act as damsels-in-distress. In the TR reboot (Square Enix, 2013), Lara’s mother and her friend, Sam, take on such roles, as Lara displays her heroism through searching for her missing mother and rescuing Sam from a violent cult on the island of Yamatai (Han & Song, 2014).

Figure 3. Lara Croft in Tomb Raider reboot (2013), 2015. (Lincoln, R.A.).

Han and Song (2014) thus conclude that new Lara possesses a dual identity, simultaneously acting as a hero and as a damsel-in-distress. Han and Song (2014) attribute new Lara’s dual identity to her relationship with her mentor, Roth, who guides her throughout the game, and her relationships with Alex and Angus, who sacrifice themselves for her survival. Han and Song (2014) briefly allude to the trailer of ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015), where Lara is seen in a (male) psychologist’s office following her traumatic experience on Yamatai in TR reboot (Square Enix, 2013). The authors use this trailer to substantiate their claim that new Lara is a damsel-in-distress, as she cannot cope psychologically after Yamatai (Han & Song, 2014). Quite evidently, Han and Song (2014) sketch a negative picture of new Lara. New Lara no doubt fits the archetype of the male hero, but Han and Song (2014) never mention what the female hero archetype that new Lara should model looks like.

In defense of new Lara, Esther MacCallum-Stewart (2014) provides a more convincing analysis of TR reboot (Square Enix, 2013). One critical aspect of the game that MacCallum-Stewart (2014) highlights, which Han and Song (2014) fail to acknowledge, is the significance of Rhianna Pratchett’s involvement in the creation of new Lara. TR reboot (Square Enix, 2013) was released at a time when players and developers (both men and women) were becoming increasingly aware of sexism in the videogame industry, and Pratchett’s role as head scriptwriter of TR reboot (Square Enix, 2013) became a focal point of these issues (MacCallum-Stewart, 2014). For MacCallum-Stewart (2014), Pratchett’s pivotal role in the creation of the new Lara is an indication from Crystal Dynamics’ side that Tomb Raider has undergone an “ideological” and “ludic” transformation, where the female player is now also a significant target audience (female players now comprise almost half of players in the US (ESA, 2019)). According to MacCallum-Stewart (2014), Pratchett’s role in the creation of TR reboot (Square Enix, 2013) suggests that women should be involved in all levels of game production and that the industry should produce games for all genders. For MacCallum-Stewart (2014), Pratchett has undeniably rebranded Lara Croft as a “feminist icon.”

To add to MacCallum-Stewart’s (2014) analysis, I also point out that Han and Song (2014) fail to mention that Lara’s male mentor, Roth, dies halfway through TR reboot (Square Enix, 2013); meaning that Lara does not rely on any male character for guidance from that point on (even into ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015) and SOTTR (Square Enix, 2018)). Furthermore, Han and Song (2014) do not conduct an analysis of the full ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015) game, merely substantiating their claim that Lara is a damsel-in-distress by referring to the game trailer that has no relation to the actual gameplay and narrative. They also fail to recognise Rhianna Pratchett’s significant involvement in the creation of TR reboot (Square Enix, 2013), which undeniably had a great impact on Lara’s representation and narrative (see Nutt, 2012).

It is clear from these discussions surrounding new Lara that, in the rebooted Tomb Raider trilogy (2013-2018), Lara is characterised differently from the Tomb Raider games released between 1996 and 2008, and that her recent representation has sparked similar debates as that of old Lara. I hope to contribute to these discussions in the analysis of ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015) that follows by further indicating the ludological and narratological changes made to Lara and examining them in relation to Han and Song’s (2014) and MacCallum-Stewart’s (2014) arguments.

As MacCallum-Stewart (2014) points out, one of the most apparent transformations that Lara Croft has undergone since 1996 is her physical appearance. In ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015), just as in TR reboot (Square Enix, 2013), Lara’s body is slim and athletic “without overstepping current ideals of athletic womanhood,” instead of being hyperfeminised as old Lara is (MacCallum-Stewart, 2014). According to various fan forums, old Lara’s vital statistics are a height is 180cm, a weight of 59kg and her breast-waist-hip ratio is 34D-24-35, which are extreme proportions similar to Barbie’s body.

In contrast, new Lara’s vital statistics are a height of 168cm and a weight of 56kg, which are similar to Alicia Vikander’s vitals (166 cm height and 53kg weight), who is the actress that portrays young Lara in the 2018 Tomb Raider film. Although even Vikander’s and new Lara’s bodies are arguably still difficult to obtain by most women -- especially if one takes not only their height and weight, but also their protruding muscles and physical strength into consideration (Vikander went through vigorous training in order to resemble virtual new Lara) -- it is at least not beyond the reach of a human being as old Lara’s figure is. Even Angelina Jolie had to wear fake breasts and hair extensions in addition to doing intensive training in order to vaguely resemble old Lara in Lara Croft, Tomb Raider (West, 2001) and Lara Croft, Tomb Raider: The Cradle of Life (De Bont, 2003) (Stasia, 2007). Based on the above, it could be argued that the restructuring of Lara’s body eliminates the extremes that are manifested in the figure of the postfeminist ‘supergirl’. As I argue further, although new Lara still often wears body-hugging clothing, she is not as hypersexualised as old Lara, nor as most of the postfeminist ‘supergirls’ in videogames are.

Lara’s wardrobe is perhaps one of the biggest appeals in the Tomb Raider games. In every Tomb Raider game up to 2008, Lara has the ability to choose from a variety of outfits, ranging from explorer clothing, to evening wear, to wetsuits and bikinis. As the game progresses, the player unlocks these outfits and Lara can wear them as she pleases. For example, should the player choose, old Lara can raid a tomb in her infamous golden bikini, which has no impact on the gameplay and is merely cosmetic. In addition, most of old Lara’s outfits are skintight and revealing (see Figure 1), placing emphasis on her hyperfeminine figure.

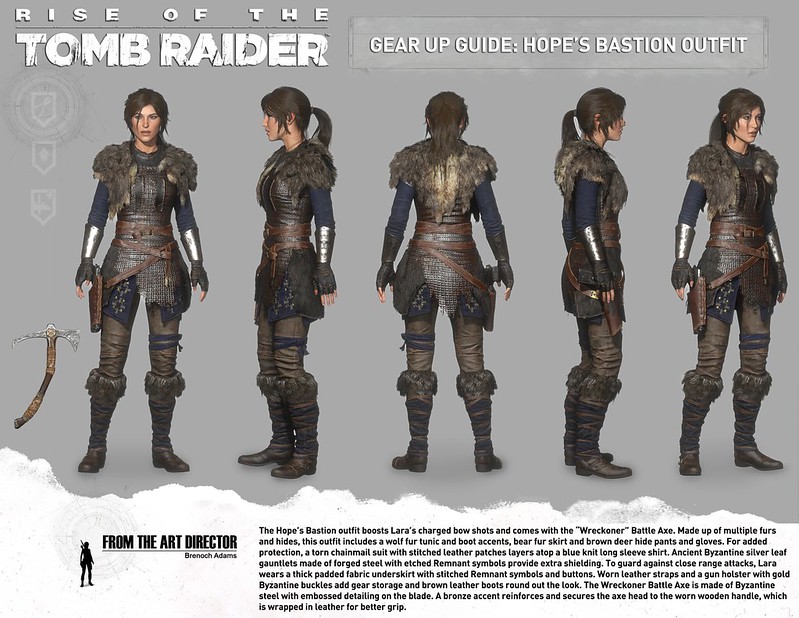

In ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015) Lara can similarly access a variety of outfits. The most notable change employed in Lara’s ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015) attire though is that 18 of the outfits that new Lara can access provide her with tactical advantages. For example, the Hope’s Bastion outfit (Figure 4) boosts bow shots, where the Siberian Ranger outfit increases Lara’s carrying capacity for special ammunition. In effect, the player does not choose Lara’s outfits for cosmetic purposes (as some players chose to have old Lara climb cliffs in her golden bikini as a means to openly objectify her), but rather, the player chooses her outfits based on the environment that she is in as this is a determining factor in Lara’s survival.

In fact, for new Lara, the option of a golden bikini does not exist at all. In all instances, as seen in Figure 4, Lara’s outfits in ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015) are unrevealing and elaborate. According to the criteria of sexualisation of female characters put forward by Lynch et al. (2016) [1], old Lara would be considered sexualised whereas new Lara’s appearance puts far less emphasis on her body as a sexual object. In this way, in terms of her physical representation, new Lara is moving away from the postfeminist ideal, as a critical characteristic of the postfeminist ‘supergirl’ is her hyperfeminised, sexualised and exposed body.

Figure 4. Hope’s Bastion Outfit, Rise of the Tomb Raider, 2015. (Flickr, 2016).

Lara Croft has furthermore transformed from a flat, two-dimensional character, to a complex, emotive character. New Lara is created with Morphology facial technology, which means that Lara’s emotions are performed by an actress and then imported into a computer system where developers build the character upon that foundation (Campbell, 2015) [2]. Old Lara, like almost all postfeminist ‘supergirls’ in videogames, also does not have a real-life referent; essentially making her an empty signifier as Mikula (2004) identified her.

It is exactly because old Lara is two-dimensional in her characterisation, facial and bodily expressions, and movements that she so easily invites players to objectify her, or identify with her, or do both, as Poole (2000, p.153) states: “[Old Lara’s] very blankness encourages the (male or female) player’s psychological projection.” In the case of new Lara though, because she has more substance as a character and as a videogame entity, she has the potential to move beyond being an empty signifier. Instead, even though players can simply use her as a mere avatar, new Lara has the potential become a character rather than acting simply as a vehicle with which the player can navigate the game world.

As Rehak (2003, p.481) also argues, owing to old Lara’s “lack of individuating detail,” she is being continually reinvented across media platforms. Old Lara often appeared on billboards and magazine covers, sometimes acting as a model, sometimes as an action heroine, and sometimes as a pin-up girl (as seen in Figure 2). Because new Lara is not so much an empty signifier due to her more complex characterisation (and as I point out later, her detailed narrative), she can only be Lara Croft, the action heroine. To my knowledge, new Lara has not appeared on different media platforms as anything other than Lara Croft the action heroine with her characterisation established in the series reboot (2013-2018) intact. As is reflected in the ludological changes made to ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015) that also work to individuate new Lara, she is less likely to be objectified as her postfeminist predecessor so easily was.

Tomb Raider is categorised as an action-adventure game. The ludological structure of adventure games demands that they are progressive, rather than emergent, and they rely heavily on narrative (Juul, 2002). In all Tomb Raider games, therefore, there is a predetermined story and Lara has to complete a number of quests in order to progress to the next part of the story and ultimately complete the game. In the reboot trilogy, developers have introduced new game modes as DLC (downloadable content) that change the ludological structure of the game in order to provide players more variety and explore additional aspects of new Lara’s characterisation and narrative. Four new game modes have been introduced in ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015), namely Remnant Resistance, Cold Darkness Awakened, Endurance Mode and Lara’s Nightmare. I focus only on Endurance Mode and Lara’s Nightmare, as these game modes have a more direct relation to the characterisation of new Lara.

The primary goal in Endurance Mode is to survive for as long as possible. Secondary goals include capturing enemy bases, discovering artifacts and raiding crypts. In Endurance Mode, Lara has a hunger meter and a cold meter; she has to hunt animals (as well as protect herself against predators) and harvest fruits in order to keep her hunger meter in the green, and she has to make campfires or stand close to fires in order to keep her warmth meter up. At night, Lara’s warmth decreases significantly faster unless she enters shelters or tombs. Should Lara’s hunger or warmth reach zero, she dies and the expedition is over. Lara also has to gather resources, such as wood and animal skins, in order to craft and upgrade weapons, or to make campfires or extraction signals. In Endurance mode, it is evident that instead of dominating her landscape and being completely in control, like (postfeminist) old Lara is, new Lara is simply just trying to survive. New Lara is subsequently physically increasingly vulnerable.

Lara’s Nightmare is an additional game mode only introduced in 2016 with the twentieth anniversary celebration of Tomb Raider. Lara’s Nightmare is based in Croft Manor where she reads a mysterious letter that threatens her removal from the Manor. Lara then enters the horrifying game world in which she repeatedly reminds herself that she is having a nightmare and that “None of this is real.” In Lara’s Nightmare, the only objective is to destroy ‘Skulls of Rage’, which are presumably the source of her nightmare, and perhaps a metaphor for her troubled psyche. Moreover, Lara has to defend herself against reincarnations of enemies that she killed in the past until she manages to destroy all the Skulls, and should Lara die, she does not respawn and the game is over.

The introduction of Endurance Mode and Lara’s Nightmare evidently has a considerable impact on the characterisation of new Lara. Joel Anderson (2014, p.135) defines vulnerability as the degree to which a person is not able to control the forces that influence her/him. Vulnerability can furthermore “be increased by those forces becoming more powerful [and]…the person becoming less able to counter these forces” (Anderson, 2014, p.135). First, Endurance Mode emphasises new Lara’s vulnerability as the forces that threaten Lara become more pervasive and uncontrollable as the game progresses, and the player is forced to experience a Lara Croft who is not invincible, but who also needs to eat and stay warm while experiencing the fear of being pitted against a hostile environment.

Second, Lara’s Nightmare allows the player to enter Lara’s troubled psyche filled with trauma from killing many enemies, and from losing her parents at a young age. In contrast to old Lara, new Lara struggles psychologically with traumas from her youth and from her recent past, and these are manifested in Lara’s Nightmare. New Lara’s mental complexity is a move away from the postfeminist ‘supergirl’ described earlier, as vulnerability and remorse are certainly not characteristics that have been displayed in previous postfeminist heroines, such as Rayne and Cereza, and certainly not in old Lara.

Moreover, in the main story, new Lara operates in an open-world map. This inevitably means that even though the game world is created for Lara, she does not have control over the forces that influence her (such as her environment) to the extent that she used to. There are some distances that new Lara cannot jump, for example, and there are some areas of the game that she cannot access until she has acquired the appropriate gear to do so. In contrast, old Lara always has the gear to do the job from the start. If the distance for new Lara to jump is too far, she will grab onto a ledge with only one hand and the player needs to act fast to prevent her from falling to her death. This further increases new Lara’s sense of vulnerability; even though Lara has many skills, the player still feels that Lara might not survive in the vast and hostile landscape (Campbell, 2015).

New Lara’s vulnerability certainly makes her more realistic in terms of Alexander Galloway’s (2004) definition that realism in videogames should not merely strive for “realistic representation,” but should “reflect critically on the minutia of everyday life, replete as it is with struggle, personal drama and injustice.” In this way, new Lara’s sense of vulnerability may offer a representation of femininity that is not far removed from many women’s lived experiences in twenty-first century society despite the gains that feminism had made over the past century. However, an emphasis on vulnerability may simultaneously simply re-invite male players to care for and protect the female character, as Mikula (2003, p.81) also writes about old Lara. Perhaps more problematically, new Lara’s mental ‘vulnerability’ may also perpetuate archaic and essentialist notions of women and hysteria. Although I do not entirely agree with Han and Song’s (2014) reading of new Lara, an emphasis on her vulnerability, perhaps pre-empted by her visit to the psychologist in the ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015) trailer, may indeed situate her as a damsel-in-distress.

Finally, new Lara’s deaths are unpleasant and gruesome in all three games from the rebooted trilogy (2013-2018). In older Tomb Raider games, Lara’s deaths were comical and not a threat to the player (or even to Lara); Lara’s ability to reincarnate infinitely eliminated the threat of death. In ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015), however, even though Lara reincarnates after dying, her deaths are gratuitous and the player might try to avoid allowing her to die. On the one hand, Lara’s gruesome deaths increase her sense of vulnerability and her realism as a character, which is a transformation from the invincible postfeminist ‘supergirl’.

On the other hand, the mutilation of the female body displayed in new Lara might encourage pervading misogynistic views towards women and should be read critically despite the positive changes made to the character. Creating a more realistic version of Lara may not necessarily produce a “feminist icon” as MacCallum-Stewart (2014) suggests the representation of new Lara aims to achieve. As Mikula (2003, p.80-81) notes about old Lara, the violence in Tomb Raider is “understood to be desirable for men” and “the idea that violence could appeal to women is unthinkable in the logic of computer game marketing.” In this way, new Lara could be understood to simply cater for a hegemonic male audience once more as old Lara did. The narratological discussion of the game I embark on below further reveals how new Lara is different from the postfeminist ‘supergirl’ archetype.

Lara’s narrative has for the most part of her history remained ambiguous. Her story differs in each Tomb Raider game, but there are some consistencies regarding her background: Lara is an orphan, she is affluent, and she is famous for exploring tombs (McCallum-Stewart, 2014). Furthermore, Lara lives alone in Croft Manor, she is unmarried and she is in her twenties. Older Tomb Raider games reveal snippets of Lara’s background through brief cut-scenes, but the biographical content of these snippets is inconsistent across the games. In 2013, however, when Tomb Raider was rebooted, Lara was given a detailed origin story for the first time in the series’ history (MacCallum-Stewart, 2014).

Old Lara’s origin and narrative was continually being reinvented by fans and thus there exists as many versions of old Lara as the number fans she has (Rehak, 2003, p.482). According to Kennedy (2002), “providing [old] Lara with a (fairly) plausible history gives her some ontological coherence and helps to enhance the immersion of the player in the Tomb Raider world, and abets the identification with Lara” (my emphasis). New Lara’s detailed origin story is not only significant because it was written by a female writer, but the existence of a completely plausible origin story inevitably lessens the number of reinventions of the character. In addition to the ludological changes that give Lara substance as a character, these changes to Lara allow players to identify with her more than objectify her.

Throughout ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015), and in previous Tomb Raider games, Richard Croft’s presence is strongly felt. Lara’s journey to Kitezh is a continuation of her father’s quest; she very often expresses that “this was in dad’s notes” or “if only dad could see this,” for example. Lara is also frequently encouraged by other characters that her father would be proud of her or that “he would have done the same.” At times, Lara experiences vivid flashbacks of her father and she repeatedly listens to his voice notes that he left behind. In TR reboot (Square Enix, 2013), Lara’s other male mentors (Grimm and Roth) are eliminated, so in ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015) only Lara’s deceased father acts as a motivating force behind her. In a study of fatherhood in videogames, Sarah Stang (2017, p.163) notes how father figures that protect female protagonists in games (perhaps not so indirectly as Lara’s father ‘protects’ her though) perpetuate “the familiar trope of a heroic man rescuing a damsel-in-distress.” As mentioned earlier, Han and Song (2014) also assert that the focus on new Lara’s father causes her to simply mimic the narrative of male heroes who often re-affirm patriarchal narratives by following in their fathers’ footsteps.

Han and Song (2014) are justified in their observation, but although Richard Croft is a dominant figure in new Lara’s past, in the “Blood Ties” expansion for ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015) Lara’s late mother is central to the story. The “Blood Ties” plot begins with Lara receiving a letter threatening her removal from Croft Manor, as she has no legal claim to the estate. Lara has to find the will in order to prove that she owns the estate. Lara discovers a crypt beneath the Manor where her mother is buried, and this acts as proof that the Manor belongs to her. In the crypt, Lara also finds her mother’s final note to her -- Amelia Croft says: “…My energy, my love [is] within you [Lara]. It will always be.” It thus becomes apparent that new Lara inherited many of her heroic qualities from her mother and not only from her father. It is true that Lara’s will to redeem her father’s name drove her to embark on her main quest, as Han and Song (2014) postulate, but it is because of her mother that she can claim back the estate and reaffirm herself as a Croft. Through resituating Amelia Croft within new Lara’s narrative, the “centralization and valorization” of the heroine’s father is subverted and it potentially allows new Lara to move beyond being a damsel-in-distress (Stang, 2017, p163).

The New Lara Phenomenon

For the reasons discussed above, new Lara does not fit the trope of the postfeminist ‘supergirl’ that has circulated in popular culture over the last two decades. Instead, she marks a transformation of the postfeminist ‘supergirl’ into a new type of heroine. As has been argued throughout, Lara Croft was one of the first notable female heroes in videogames and remains “a leading model and mythical signifier for female protagonists” (Han & Song, 2014, p.27). After 2013, other female protagonists that closely resemble the characteristics of new Lara discussed above have gradually started emerging, just as the postfeminist heroine archetype emerged twenty years ago with the birth of old Lara.

Of course, not all aspects of every heroine in every game released after 2013 models new Lara, but female characters in AAA videogames have nevertheless undergone a dramatic change compared to female protagonists before 2013. This new type of heroine and ludological structure of the games seems to be becoming a new genre for female-fronted role-playing games. In 2018, over thirty AAA titles that feature notable female heroes were released (Henry, 2018); some of these games following the portrayal and ludological and narratological structure of ‘the new Lara phenomenon’ more closely than others.

Although this is an inadequate list of titles, the trend of desexualisation is, for example, displayed in characters such as: Ellie from The Last of Us (Naughty Dog, 2013), Cassandra Pentaghast and other female characters from Dragon Age Inquisition (Bioware, 2014), Lyris from TheElder Scrolls Online (Zenimax Online Studios, 2014), Evie Frye from Assassin’s Creed Syndicate (Ubisoft, 2015), Joule from ReCore (Armature Studio, 2016), Zarya and Brigitte from Overwatch (Blizzard, 2016), Emily from Dishonored (Arkane Studios, 2012) and Dishonored 2 (Arkane Studios, 2016) and Iden Versio from Star Wars: Battlefront II (EA DICE, 2017). Games such as Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice (Ninja Theory, 2017), Celeste (Matt Makes Games, 2018) and Her Story (Sam Barlow, 2015), all with female protagonists who are similarly desexualised, further focus on complex mental issues and vulnerability. In another vein, games such as Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey (Ubisoft, 2018) and Her Story (Sam Barlow, 2015) also emphasise the main protagonists’ relationships with their mothers and they do not have male mentors.

I do not have the liberty to discuss the reasons for these transformations in detail, and this is perhaps an avenue for future study, but one fundamental reason may be because gaming technology now allows for more detailed programming, which inevitably has an impact on the appearances and narratives of these women and the worlds that they occupy (Kuo et al., 2017, p.102). Another reason is that some big gaming companies acknowledge that white males (used to) occupy most positions in the creation of videogames, and they’ve made efforts to change that. In the beginning of Assassin’s Creed Syndicate (Ubisoft, 2015) and Assassin’s Creed Odyssey (Ubisoft, 2018), for example, the player is notified that the game was created by a team of programmers that consists of people with different genders, races, religions and sexual orientations.

Furthermore, even though these are isolated cases, some women have recently occupied chief positions in the videogame industry [3]. Where women are involved in higher positions in the creation of videogames, the games also tend to be more progressive in their portrayals of women or more representative of female subjectivity. As I showed throughout this paper, for example, Rhianna Pratchett’s involvement as head writer of TR reboot (Square Enix, 2013) and ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015) possibly had a substantial impact on the characterisation of new Lara. That being said, more women are playing games and they are good at it too. In 2019, 65 percent of households in the United States own a gaming device, and 46 percent of them are women (ESA, 2019). The emergence of esports, which is competitive gaming at a professional level, and is predicted to be a $1.5 billion enterprise by 2020, is also providing platforms for female players to compete and subvert negative stereotypes about women and gaming (Dwan, 2017).

These are only a handful of examples of initiatives employed to reduce the gender gap in gaming. These statistics and examples also show that the increasing awareness surrounding women in gaming may be a contributing factor to ‘the new Lara phenomenon’. As women’s status in gaming is improving, so is the representation of female videogame characters, and where women are more involved in the creation of games, the female protagonists tend to be more in line with new Lara. In turn, the more progressive representation of popular female heroes also affects perceptions of women in general society.

Conclusion

As has been argued in this paper, the representation of Lara Croft has recently undergone a dramatic transformation. From the 1990s onward ‘powerful’ women were mostly portrayed in the mass media as what Stephanie Genz (2009) identified as the postfeminist ‘supergirl’, and old Lara, who was created in the 1990s, presents an epitome of the postfeminist ‘supergirl’ in videogames. In line with the contradictions inherent in the politics of postfeminism and postmodernism, old Lara displayed both a positive and a negative role model for early twenty-first century women.

The new type of female hero that Lara now exemplifies clearly moves away from the postfeminist ‘supergirl’ ideal, but does not necessarily present a better version of femininity per se. New Lara is simply a different version of femininity. As Du Preez (2000, p.5) terms it, new Lara is another “archetype” that exists among still, at times, pervasive postfeminist portrayals of women, as well as other versions of femininity not articulated in this paper. In my view at least, new Lara is a more progressive and representative version of femininity in the twenty-first century and the type of female hero that she exemplifies is more representative of women’s real-lived experiences in a patriarchal society due to the emphasis placed on her vulnerability. I also contend that new Lara is a more attainable version of femininity compared to the impossible ideal that is the postfeminist ‘supergirl’.

Lara Croft’s popularity, her status as the first significant videogame heroine, and her long history has made her one of the leading signifiers for the representation of women in videogames -- and many other recent videogame heroines follow the representation of new Lara. Most of the videogame heroines that follow the portrayal of new Lara also only started emerging after 2013, when Lara changed, in a zeitgeist where women’s roles as consumers and producers of videogames were being reevaluated.

Videogames might therefore see even more types of games that are similar in the ludological and narratological structure of TR reboot (Square Enix, 2013) and ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015) emerging in the near future. If one looks at the gradual move from the postfeminist ‘supergirl’ to a new and different type of heroine in videogames as a trend, perhaps in another decade or two videogamers might even see another new type of heroine emerge. Depending, of course, on how the videogame industry evolves and what role women are yet to play in the industry.

Endnotes

[1] In their study, the sexualisation of female characters was measured by the proportions and amount of skin revealed in four areas of the character’s body (waist, buttocks, chest and leg regions) and sexualised movements, for example unnecessary undulation or jiggling. Characters were also considered as sexualised if their breasts were disproportionate to their body size.

[2] In ROTTR (Square Enix, 2015), Camilla Luddington is the voice of Lara Croft.

[3] See Johnson (2017) and Gaudiosi (2013; 2014) for comprehensive lists of high-ranking women in the gaming industry.

References

Anderson, J. (2014). Autonomy and Vulnerability Entwined. In C. Mackenzie, W. Rogers & S. Dodds (Eds.) Vulnerability: New Essays in Ethics and Feminist Philosophy (pp.134-161). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Arkane Studios. (2016). Dishonored 2 [Console and PC]. Digital game directed by Harvey Smith, published by Bethesda.

Arkane Studios. (2012). Dishonored [Console and PC]. Digital game directed by Raphaël Colantonio and Harvey Smith, published by Bethesda.

Armature Studio. (2016). ReCore [Console and PC]. Digital game directed by Mark Pacini and David Dedeine, published by Microsoft Studios.

Arrojas, M. (2016). Lara Croft Adds Two New World Records to Her Collection. Retrieved April 10, 2018 from https://techraptor.net/content/lara-croft-adding-two-new-world-records-collection.

Bailey, C. (1997). Making Waves and Drawing Lines: The Politics of Defining the Vicissitudes of Feminism. Hypatia, 12(3), 17-28.

Bioware. (2014). Dragon Age Inquisition [Console and PC]. Digital game directed by Mike Laidlaw, published by Electronic Arts.

Blizzard Entertainment. (2016). Overwatch [Console and PC]. Digital game directed by Jeff Kaplan, Chris Metzen and Aaron Keller, published by Blizzard Entertainment.

Bowman, R (Director). (2005). Elektra. [Film]. 20th Century Fox.

Campbell, C. (2015). The Reconstruction of Lara Croft. Retrieved September 27, 2017 from https://www.polygon.com/features/2015/7/10/8925285/the-reconstruction-of-lara-croft-rise-of-the-tomb-raider.

Condon, B (Director). (2017). Beauty and the Beast. [Film]. Walt Disney Pictures.

Crystal Dynamics. (2015). Rise of the Tomb Raider [Console and PC]. Digital game directed by Noah Hughes, Brian Horton and Daniel Neuburger, published by Square Enix.

Crystal Dynamics. (2013). Tomb Raider [Console and PC]. Digital game directed by Noah Hughes, Daniel Chayer and Daniel Neuburger, published by Square Enix.

Curtis, N. (2017). Wonder Woman’s Symbolic Death: On Kinship and the Politics of Origins. Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, 8(4), 307-320.

De Bont, J (Director). (2003). Lara Croft, Tomb Raider: The Cradle of Life. [Film]. Paramount Pictures.

Du Preez, A. (2000). Virtual Babes: gender, archetypes and computer games. Communicatio, 26(2), 18-27.

Dwan, H. (2017). What are esports? A beginner’s guide. Retrieved March 14, 2018 from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/gaming/guides/esports-beginners-guide/.

EA DICE. (2017). Star Wars: Battlefront II [Console and PC]. Digital game directed by Bernd Diemer, published by Electronic Arts.

Eidos Montreal. (2018). Shadow of the Tomb Raider [Console and PC]. Digital game directed by Daniel Chayer, published by Square Enix.

Electronic Software Association. (2019). Essential Facts about the Computer and Videogame Industry. Retrieved June 11, 2020 from https://www.theesa.com/esa-research/2019-essential-facts-about-the-computer-and-video-game-industry/.

Flanagan, M. (1999). Mobile Identities, Digital Stars, and Post Cinematic

Selves. Wide Angle, 21(1), 77-93.

Flickr. (2016). Gear Up Guide: Hope’s Bastion Outfit. Retrieved June 11, 2020 from https://www.flickr.com/photos/tombraiderofficialflickr/26919833955/in/album-72157661430292439/.

Flickr. (2011). Lara Croft Loaded Cover. Retrieved March 15, 2020 from https://www.flickr.com/photos/jeffmaysh/6393115793.

Galloway, A.R. (2004). Social realism in gaming. Game Studies, 4(1). http://gamestudies.org/0401/galloway/.

Gamble, S. (2001 [1999]). Postfeminism. In S Gamble (Ed), The Routledge Companion to Feminism and Postfeminism (pp.43-54). London: Routledge.

Gaudiosi, J. (2014). 10 Powerful Women in Videogames. Retrieved March 14, 2018 from http://fortune.com/2014/09/23/10-powerful-women-video-games/.

Gaudiosi, J. (2013). The 10 Most Powerful Women in Gaming. Retrieved March 14, 2018 from http://fortune.com/2013/10/24/the-10-most-powerful-women-in-gaming/.

Genz, S. (2009). Postfemininities in Popular Culture. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Genz, S. (2006). Third Way/ve: The politics of postfeminism. Feminist Theory, 7(2), 333-353.

Genz, S. & Brabon, B.A. (2009). Postfeminism: Cultural Texts and Theories. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Guerrilla Games. (2016). Horizon Zero Dawn [Console and PC]. Digital game directed by Mathijs de Jonge, published by Sony Interactive Entertainment.

Han, H. & Song, S. (2014). Characterisation of Female Protagonists in Videogames: A Focus on Lara Croft. Asian Journal of Women’s Studies, 20(3), 27-49.

Henry, J. (2018). 30 Games with Female Protagonists in 2018 You Should Be Excited For. Retrieved March 10, 2018 from http://jstationx.com/2018/01/02/30-games-with-female-protagonists-2018/.

Jenkins, P (Director). (2017). Wonder Woman. [Film]. Warner Bros. Pictures.

Johnson, P. (2017). 21 Powerful Women in Gaming. Retrieved March 14, 2018 from https://www.bigfishgames.com/blog/21-powerful-women-in-gaming/.

Juul, J. (2002). The Open and the Closed: Games of Emergence and Games of Progression. Proceedings of Computer Games and Digital Cultures Conference, Tampere University.

Kennedy, H. W. (2002). Lara Croft: Feminist Icon or Cyberbimbo? On the limits of Textual Analysis. Game Studies, 2(2). http://gamestudies.org/0202/kennedy/.

Kuo, A., Hiler, J.L. & Lutz, R.J. (2017). From Super Mario to Skyrim: A framework for the evolution of videogame consumption. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 16,101-120.

Kusana, K (Director). (2005). Aeon Flux. [Film]. Paramount Pictures.

Lazar, M.M. 2009. Entitled to consume: postfeminist femininity and a culture of post-critique. Discourse & Communication 3(4): 371-400.

Lincoln, R.A. (2015). ‘The Wave’ Director Roar Uthaug to Helm ‘Tomb Raider’ Reboot. Retrieved July 9, 2017 from http://deadline.com/2015/11/director-behind-norways-oscar-submission-wave-to-helm-tomb-raider-reboot-1201627252/.

MacCallum-Stewart, E. (2014). “Take That, Bitches!” Refiguring Lara Croft in Feminist Game Narratives. Game Studies, 14(2). http://gamestudies.org/1402/articles/maccallumstewart.

Makuch, E. (2018). Report Shows Women Earn Less Than Men at GTA 5 Studios, Rockstar Promises to do Better. Retrieved April 10, 2018 https://www.gamespot.com/articles/report-shows-women-earn-less-than-men-at-gta-5-stu/1100-6458010/.

Matt Makes Games. (2018). Celeste [Console and PC]. Digital game directed by Matt Thorson, published by Matt Makes Games.

McG (Director). (2000). Charlie’s Angels. [Film]. Columbia Pictures.

McRobbie, A. (2004). Post-feminism and Popular Culture. Feminist Media Studies, 4(3), 255-264.

Mikula, M. (2004). Lara Croft, Between a Feminist Icon and Male Fantasy. In R. Schubart & A. Gjelsvik (Eds.), Femme Fatalities: Representations of Strong Women in the Media, (pp.57-70) Goteborg: Nordicom.

Mikula, M. (2003). Gender and Videogames: The political valency of Lara Croft. Continuum, 17(1), 79-87.

Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Screen, 16(3), 6-18.

Naughty Dog. (2013). The Last of Us [Console]. Digital game directed by, published by Sony Computer Entertainment.

Ninja Theory. (2017). Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice [Console and PC]. Digital game directed by Bruce Straley and Neil Druckmann, published by Ninja Theory.

Nutt, C. 2012. Rebooting Lara: Rhianna Pratchett on Writing for Tomb Raider. Retrieved June 11, 2020 from https://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/181813/rebooting_lara_rhianna_pratchett_.php.

Petrie, D (Director). (2000). Miss Congeniality. [Film]. Warner Bros. Pictures.

PlatinumGames. (2009). Bayonetta [Console and PC]. Digital game directed by Hideki Kamiya, published by Sega.

Poole, S. (2000). Trigger Happy: Videogames and the Entertainment Revolution. New York: Arcade.

Rehak, B. (2003). Mapping the Bit Girl Lara Croft and new media fandom. Information, Communication & Society, 6(4), 477-496.

Russo, M. (1994). The Female Grotesque. New York: Routledge.

Sam Barlow. (2016). Her Story. [PC and Mobile], UK: Sam Barlow.

Schleiner, A. (2001). Does Lara Croft Wear Fake Polygons? Gender and Gender-Role Subversion in Computer Adventure Games. Leonardo, 34(3), 221-226.

Stang, S. (2017). Big Daddies and Broken Men: Father-Daughter Relationships in Videogames. Loading…, 10(16), 162-174.

Stasia, C. L. (2007). ‘My Guns Are in the Fendi!’: The Postfeminist Female Action Hero. In S. Gillis, G. Howie & R. Munford (Eds.), Third Wave Feminism: A Critical Exploration (pp. 237-249). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Stella’s Tomb Raider Site. (2017). Tomb Raider Timeline. Retrieved September 27, 2017 from http://tombraiders.net/stella/timeline.html.

Stromberg, R (Director). (2014). Maleficent. [Film]. Abbey Road Studios.

Terminal Reality. (2002). BloodRayne [Console and PC]. Digital game directed by Joe Wampole, published by Majesco Entertainment.

Ubisoft Quebec. (2018). Assassin’s Creed Odyssey [Console and PC]. Digital game directed by Jonathan Dumont and Scott Phillips, published by Ubisoft.

Ubisoft Quebec. (2015). Assassin’s Creed Syndicate [Console and PC]. Digital game directed by Marc-Alexis Côté, Scott Phillips and Wesley Pincombe, published by Ubisoft.

Videogame Sales Wiki. (n.d). Tomb Raider. Retrieved April 10, 2018 from http://vgsales.wikia.com/wiki/Tomb_Raider.

Walden, K. (2004). Run Lara Run! The Impact of Computer Games on Cinema’s Action Heroine. In R. Schubart & A. Gjelsvic (Eds.), Femme Fatalities: Representations of Strong Women in the Media (pp.71-88). Goteborg: Nordicom.

Waltonen, K. (2004). Dark Comedies and Dark Ladies: The New Femme Fatale. In R. Schubart & A. Gjelsvic (Eds.), Femme Fatalities: Representations of Strong Women in the Media (pp.127-144). Goteborg: Nordicom.

West, S (Director). (2001). Lara Croft, Tomb Raider. [Film]. Paramount Pictures.

ZeniMax Online Studios. (2014). The Elder Scrolls Online [Console and PC]. Digital game directed by Matt Firor, published by Bethesda.

List of Abbreviations

TR reboot -- Tomb Raider reboot

ROTTR -- Rise of the Tomb Raider

SOTTR -- Shadow of the Tomb Raider