Assessing Toxic Behaviour in Dead by Daylight : Perceptions and Factors of Toxicity According to the Game’s Official Subreddit Contributors

by Patrick Deslauriers, Laura Iseut Lafrance St-Martin, Maude BonenfantAbstract

Toxicity is a relatively new concept when it comes to describing behaviour and communication practices. It is now widely accepted as a denominator for aggressive and abusive interactions or relationships, both online and offline. However, toxic behaviour in videogames remains an elusive topic. Despite many research initiatives, and the implementation of numerous new features in games to discourage disruptive behaviour, toxicity continues being a part of players’ everyday experience with many online games. The goal of this article is thus to identify key causes and factors that may lead to toxic in-game interactions according to players’ perception. We studied the Dead by Daylight (DbD) (Behaviour Interactive, 2016) community, using a content analysis of players’ conversations on the game’s official subreddit to help us better understand how they perceive potentially toxic behaviour inside of the game. More specifically, we analyzed how and why players intensify or counter behaviour they view as toxic. We were able to identify five key aggravating factors for toxicity in DbD : 1) Role identification, 2) Ambiguity in objective setting, 3) Individual gaming experience, 4) Task repetition, 5) Rigidity of norms. These factors are interrelated, in that they may echo and amplify each other. Nonetheless, categorizing toxic behaviours remains difficult because the process depends on consensus-building within each videogame’s community (or communities).

Keywords: toxicity, online gaming communities, Dead by Daylight, player’s perception, content analysis

1.0 Introduction

Toxicity is a relatively new concept when it comes to describing behaviour and communication practices. It originated in masculinity theories (Connell, 1983; Connell, Ashenden, & Kessler, 1982) as a tool to explain various social mechanisms constituting the reproduction of hegemonic masculinity in the Western world. It is now widely accepted as a denominator for aggressive and abusive interactions or relationships, both online and offline. The "toxicity problem" has become a major concern for many videogame companies and online communities, as the 2018 launch of the Fair Play Alliance shows, the mission of which is "to share research and best practices that drive lasting change in fostering fair play in online games" (Fair Play Alliance, 2018). However, toxic behaviour in videogames remains an elusive topic: what is toxicity? Does it manifest itself in a similar manner in all games? What can we do to counter toxic interactions? Despite many research initiatives, and the implementation of numerous new features in games to discourage disruptive behaviour, toxicity remains a part of players’ everyday experience with many online games.

Dead by Daylight (DbD) (Behaviour Interactive, 2016) can illustrate a general confusion about the nature, causes and effects of toxicity. Indeed, the DbD community is not commonly perceived as toxic, even if toxic behaviour can manifest itself in certain situations. Dead by Daylight is an asymmetrical game opposing survivors and killers that can be played on PC, PlayStation 4, Switch and Xbox One. DbD proposes a "horror" setting that is mainly conveyed by the barren and gloomy maps and environments, as well as through the brutal and gory nature of the killers’ attacks on survivors. Killers play alone, and their main objective is to kill survivors. Survivors form four-player teams to complete a series of tasks in order to escape and win. Survivors may win individually or as a team. Throughout the course of a match, which lasts on average between 10 and 20 minutes, players of each role collect "bloodpoints" while completing different micro-objectives (mainly individual). These are important resources that help players unlock powers and items in the long run. Also, players have ranks that are reset every month, which indicates that more and less experienced players will often play with/against each other. This context, in which survivors can also be in opposition with each other, creates a competitive and antagonistic dynamic of play, where many players from each role try to win at all costs.

Within the framework of a research partnership between our research team and Behaviour Interactive, we studied DbD and its community through the lens of toxicity. Our goal was to identify key causes and factors for the development of toxic in-game interactions between players. Our research methods included a content analysis of players’ conversations to help us better understand how they perceive potentially toxic behaviour inside of the game. To do so, we studied players’ exchanges on the game’s official subreddit.

More specifically, we analyzed the perceptions and intentions (through arguments and discussions on DbD’s subreddit) that encourage players to intensify or counter behaviour they view as toxic while playing DbD. In this sense, our research does not focus on the "real" causes and factors of toxicity in the game, but rather on the players’ opinions of these causes and factors, whether their perceptions match or not with the "objective" in-game behaviour [1]. Thus, before studying the prevalence of toxic behaviour inside of a game, we deem it necessary to understand what the game’s community considers as toxic behaviour. Moreover, the goal of this article is not to study toxicity as it may take form in exchanges on the subreddit (for example, if a user insults another one during a heated conversation in the subreddit); instead, we are interested in the perception of in-game toxicity, as it is discussed by certain players on DbD’s subreddit.

In order to showcase our results, the article will be organized as followed. First, informed by current research on this phenomenon in videogames, we will problematize toxicity to elaborate its stakes for videogame companies. Then, we will introduce our research methodology, which we used in order to investigate in-game toxic behaviour as it is perceived by DbD players who express their views on Reddit. Third, we will give specific examples of perceived toxic behaviour and summarize our research results. Lastly, we will briefly discuss these results, their limitations and next steps for research on the topic.

2.0 Toxicity in Videogames

Understood as a mode of social interaction and communication, toxicity has been a topic of interest in game studies from the outset of the discipline in the early 2000s. However, recent public controversies have heightened its relevance to the industry, intensified discussions in the media and increased gamers’ awareness of the problem. As concerns about toxicity in online games grows, it is being scrutinized by an increasing number of scholars.

From the Ancient Greek τοξικόνpharmakon (toxikón) signifying "poison for use on arrows" and then, only "poison," the concept of toxicity came to be used to describe human behaviour in the 1980s; henceforth, several game studies scholars sought to describe toxicity. To understand the phenomenon as broadly as possible, Kwak and Blackburn (2014) define toxic behaviour as "bad behaviour that violates social norms, inflicts misery, continues to cause harm after it occurs, and affects an entire community." Other scholars such as Shores, He, Swanenburg, Kraut and Riedl define toxicity as a set of deviant attitudes:

Toxic behavior is a subset of deviant behaviour and is often considered "unsportsmanlike." It includes a large range of behaviours, such as sending offensive messages or intentionally helping the opposing team. However, specific definitions of toxic behaviour may be situational to subsections of the community (2014, p.1357).

These definitions highlight the difficulty of elaborating a precise definition of toxicity, which is a set of behaviours that one categorizes as toxic in relation to constantly renegotiated and evolving social norms.

Therefore, scholars have sought to further study toxic behaviour. For example, griefing is most frequently studied because game mechanics themselves enable it. Mulligan and Patrovsky (2003) first proposed a definition of griefing. According to them, a griefer is "a player who derives his/ her enjoyment not from playing the game, but from performing actions that detract from the enjoyment of the game by other players" (Mulligan & Patrovsky, 2003, p.475). Similarly, Bartle (2007) put forward the importance of intentionality in his own definition of a griefer as "someone who deliberately did something for the pleasure in knowing it caused others pain." More broadly, "griefing is used to describe when a player within a multiplayer online environment intentionally disrupts another player’s game experience for his/ her own personal enjoyment or material gain" (Achterbosch, Miller, & Vamplew, 2013, p.1).

These definitions highlight three key elements constituting a definition of toxicity based on the observation of griefing: (1) intent, (2) decreased pleasure for the victim and (3) increased pleasure for the instigator. Interestingly, Gray (2013) notes that griefing behavior like spawn killing and sit-in gaming are also used by marginalized communities, such as black and latina women, to collectively resist sexist and racist practices.

Indeed, another frequently studied theme regarding toxicity in videogames is sexual harassment and the many forms of sexism. Gaming culture has been known to be an unwelcoming place for women, as exemplified by public events like the Gamergate (2014). Since sexism is widely recognized as a relevant problem in gaming culture (Fox & Tang, 2017), many scholars tried to find factors influencing the prevalence of such behavior. Some of these factors are: gaming culture (Consalvo, 2012), geek and gamer identity (Salter and Blodgett, 2017, Tang et al., 2020), evolutionary factors such as dominance status and (in-game) performance (Kasumovic & Kuznekoff, 2015), social dominance orientation (Tang & Fox, 2016), as well as personality factors such as machiavellianism and psychopathy (Tang et al., 2020).

Besides research on griefing and sexism, game studies scholars have addressed toxicity from other perspectives. Some have developed ways to identify and quantify toxic behaviour in online environments (Chesney, et al., 2009; Balci & Salah, 2015; Märtens, et al., 2015). Other scholars have tried shedding light on toxic players’ motivations (Foo & Koivisto, 2004; Achterbosch, Miller, & Vamplew, 2008; Achterbosch, et al., 2014; Blackburn & Kwak, 2014). Among those, scholars like Przybylski and his colleagues (2014) tested the frustration-aggression theory (based, among other, on the Self-Determination Theory of Deci and Ryan (2012)). Their results support the hypothesis that frustration in the three basic psychological needs of mastery, autonomy and relatedness leads to increased short-term aggression signs.

Other studies have found that many toxic players, also called "trolls," understand their behaviour as a sort of game in itself, or justify it as such (Donath, 1999; Hardaker, 2010; Condis, 2018). Another topic of interest is toxic behaviour’s impact on other players, specifically with regards to player retention (Kwak & Blackburn, 2014; Shores, et al., 2014; de Mesquita Neto & Becker, 2018). Even though many of these researchers explore qualitative data, there has been a surge in recent studies where quantitative data (mainly behavioral data and surveys) is analyzed to understand toxicity in a new light (Fox & Tang, 2016; McClean, et al., 2020; Shen, et al., 2020).

Finally, research concerning the classification of toxic behaviour in videogames is most relevant to our paper. Foo and Koivisto (2004) introduce four categories, which they differentiate based on toxic players’ intent, namely: harassment, power imposition, scamming and greed play. According to this model, toxic behaviour usually violates the rules of online gaming on one of three levels: software and code-dependent rules, the company’s explicit guidelines (usually introduced in a document upon signing up), or the community’s implicit rules that define fair play. Kwak, Blackburn and Han (2015) identify toxic behaviour as either cyberbullying (verbal abuse or offensive language) or domain specific toxicity (abuse enabled by and defined within the context of specific game features and mechanics). Synthesizing preceding typologies developed in game studies, Saarinen (2017) proposes a broad typology: (1) flaming or harassment (verbal abuse), (2) griefing (power imposition), (3) cheating (unfair advantage), (4) scamming (for money or goods) and (5) cyberbullying (repetitive verbal abuse).

If research has allowed better understanding of toxic players’ motives, categorizing their behaviour, and qualifying the seriousness of toxicity’s impact within online communities, studying specific communities’ practices remains important because the perception of toxicity varies according to game mechanics and within a community’s social norms, if not between one game’s subcommunities. Following Hardaker’s (2010) study of trolls, our research seeks to understand and categorize toxicity in DbD on the basis of players’ perceptions shared within the community on Reddit. Specifically, we aim to understand how in-game toxicity is perceived (i.e. what are its perceived causes and factors) by certain players discussing this topic on DbD’s subreddit.

3.0 Methods

As a case study designed to test research tools and methods, this research project is exploratory first and foremost. In short, we performed a content analysis of textual data collected manually from an out-game online platform in order to study perceptions and intentions that push players to intensify or counter behaviours perceived as toxic while playing DbD. Using quantitative data can limit one’s interpretation of complex phenomena, especially when it comes to players’ perception and intentionality. Therefore, we opted for a qualitative approach, which seemed necessary in order to grasp how and why toxicity comes to be accepted and integrated within a community’s common practices. Moreover, out-of-game discussions are important to study since they are "an essential part of gamer culture" (Milner, 2011, p.163) and can thus help contextualize in-game behaviour. In other words, although toxicity is experienced during play, discussions about this phenomenon happen mainly on social media platforms.

In order to delineate our subject matter, we chose to collect data produced from 18 September 2018 to 11 December 2018. This timeframe matches the release of the chapter Shattered Bloodline on PC, PS4 and Xbox One, which introduces a new killer (The Spirit), a new survivor (Adam Francis) and a new map (Family Residence). In addition to these new characters and map, that chapter also introduced the 2.2.0 update in September 2018. Choosing this timeframe allows a closer look into a specific moment in the history and development of DbD.

We chose to study the game’s official subreddit (r/deadbydaylight) on Reddit because it is one of the most popular meeting places for the community to talk about the game. On a larger scale, Reddit has been closely associated with "geek" and gaming culture for many years (Massanari, 2017), as many members from various communities converge daily on this platform to discuss their favorite games. Thus, Reddit can help us understand how players collectively assess and define what is toxic behaviour inside of the game. This article’s results therefore refer to DbD’s subreddit only, on the basis of which we selected our data according to specific criteria. First, after reviewing the literature, exploring various networks the community uses to communicate, interviewing two of its moderators (Behaviour Interactive employees) and mobilizing our own knowledge of the game, we listed behaviours that may potentially be viewed as toxic.

Second, before manually encoding our data, we aimed to select around a hundred comments for each theme related to toxicity [2]. Eligible threads were to contain at least ten posts, representing an actual conversation between users [3]. We ensured that comments contained in each one of these threads described, in some way, a user’s perception of the toxic in-game behaviour under discussion. We did not select comments based on their popularity [4]; on the contrary, observing how discussions came to polarize opinions about behaviour was necessary. All in all, we encoded and analyzed 1,848 posts.

Third, encoding [5] was performed using Nvivo, which allows categorizing textual data and cross-tabulation analysis. We classified the textual data using various tags; for the purposes of this article, we will refer to the following broad categories: (1) sentiment [6] about behaviour (from very positive to very negative), (2) perception of behaviour, (3) reaction to behaviour and (4) assessment of responsibility for behaviour.

Subcategories in each main category were created before the encoding phase, even if they could change during that phase. Such changes were made iteratively and following the inductive approach mentioned above. These subcategories allow looking into important topics in order to understand both general sentiments regarding potentially toxic in-game behaviour and explanations for these sentiments and behaviours. Lastly, compiling and indexing results helped build the figure included in the following sections of this article. In total, we manually attributed 11 164 tags.

With respect to research ethics, it is important to note that all data was collected on a public online platform (Reddit). Additionally, we did not collect or use sensitive data, as their content addresses game mechanics and in-game behaviour, nor could one link collected data to specific users’ DbD account, considering that individuals use different pseudonyms on each platform. Lastly, while we did collect pseudonyms used on Reddit, these do not allow personal identification. Moreover, no pseudonyms are exposed in this article.

4.0 Results

4.1 Perception of Behaviour

In order to identify perceptions and intentions that encourage players to intensify or counter behaviour we may consider as toxic, it was crucial to understand what kind of community DbD’s subreddit fosters. Mainly, with regards to posts’ content, that is, characterizing how in-game behaviour is perceived, we notice that the DbD community [7] is divided about several key practices in the game. Players use a variety of arguments to justify their views, either defending themselves or calling out behaviours in question. Indeed, we observe that most types of behaviour under study can be both criticized and upheld by different groups within the community. As explained later on in this paper, diverging interpretations of the "correct" rules, and variations in the institutionalization of metagaming practices among different subcommunities, can explain such polarization: killers versus survivors, players focusing on resource accumulation versus those seeking to achieve the game’s "official" objectives, etc. In other words, differences in opinion highlight the coexistence of several groups and subcommunities with diverging, if not contradictory views on the game.

Some of these subcommunities are linked with players’ experience levels. According to our interpretation of the results, perception of toxicity levels inside of the game increases according to players’ levels. PC players, however, are confronted with toxicity from the outset through text chatting [8]: words may easily be interpreted as toxic, whereas the meaning of behaviour becomes clearer with practice. Playing on a console requires learning to recognize toxic behaviour in-game, that is to say that new players who cannot identify the meaning of certain behaviours may not think of them as toxic. As they gain experience and understand the game and its rules better, players come to identify the community’s level of toxicity.

4.2 Toxicity Gradation

Based on our analysis of posts collected on the subreddit under study, it appears that behaviours judged as most toxic inside of the game are, in alphabetical order: blinding, body blocking, face camping, hatch camping, lobby dodging, rush unhooking, sandbagging, slugging, text chatting and tea bagging.

Table 1. Definitions of behaviours viewed as toxic by DbD players on r/deadbydaylight

|

Behaviour |

Definition |

|

Blinding |

Refers to a survivor’s use of their flashlight to temporarily and repeatedly blind a killer by flashing light in their eyes. Jitter clicking on the flashlight’s ON button also counts as blinding. |

|

Body blocking |

Killers are said to bodyblock when they intentionally stand in the staircase to block access to and from the basement; hence preventing survivors stuck in the basement from escaping. Killers can also block a player when the latter hangs from a hook (face camping) or access to the lever that opens a door. Survivors are said to engage in bodyblocking when they prevent a killer from hooking a survivor. They stand in between the killer and the hook, in such a way that the killer cannot trigger the hooking cinematic. The term also refers to the practice of taking hits for a teammate to help them escape. |

|

Face camping |

Killers face camp when they stand in front of a hooked survivor ("in their face") for some time. |

|

Hatch camping |

Hatch camping means either 1. waiting at the hatch while other teammates repair the generators or escape the killer, or 2. a "hatch standoff," when the killer and last survivor both stand close to the hatch for a long time without moving. In the second instance, hatch camping is a patience test, as players wait until one of them logs off or makes a mistake. |

|

Lobby dodging |

When a player leaves the lobby before the game starts. This applies to both killers and survivors. If the killer leaves the lobby, the game is over for everyone because the killer hosts the game. |

|

Rush unhooking |

Rush unhooking refers to three distinct behaviours. First, a new player can start trying to unhook a teammate even if the killer is close by. Second, it can happen when survivors engage in sandbagging, that is, when they try to make a killer change targets. Third, if a survivor "farms" to accumulate resources, they can rush unhook even if the killer is close by. |

|

Sandbagging |

Refers to a player’s behaviour when they intentionally move towards a teammate in the hope that the killer will target that teammate instead of them. |

|

Slugging |

Slugging is a strategy by which killers leave a survivor laying on the floor. The survivor then crawls, slowly loosing life points, until the killer lifts them up again to hook them, until a teammate comes to help them out, or until they die (a few minutes later). |

|

Text chatting |

Refers to the text communication tool available in the game’s PC version. Survivors can chat in the lobby before the game starts; everyone can chat in the lobby after the game ends. |

|

Teabagging |

Refers to the act of repeatedly crouching |

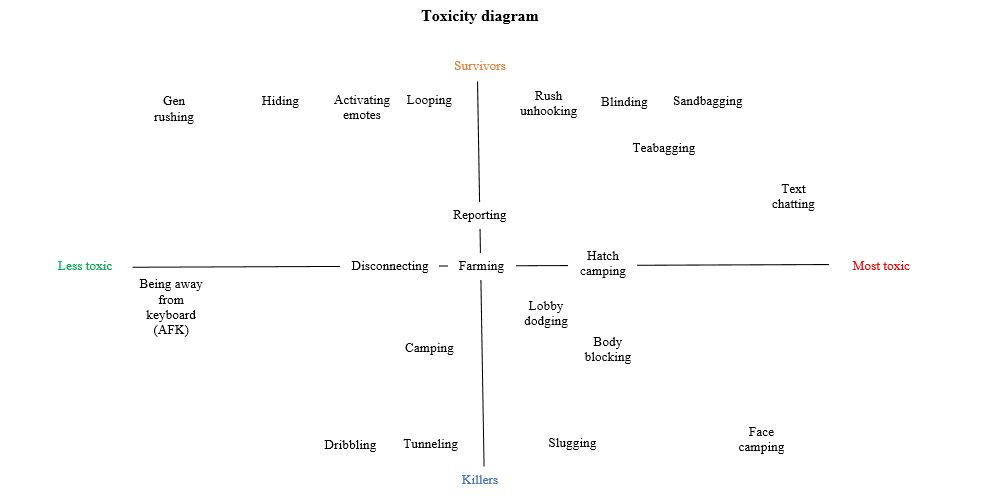

Whereas the perception of the degree of general toxicity evolves through time as players gain experience, toxicity rankings for each type of in-game behaviour is quite consensual on the subreddit within our chosen timeframe. Indeed, Figure 1 shows a diagram representing the classification of the study’s results based on the community’s views of different types of behaviour. Behaviours are arranged from less to most toxic (horizontally) according to a player’s role as survivor or killer (vertically). More specifically, the vertical axis indicates which role behaviours are usually associated with. Terms displayed towards the top of Figure 1 refer mostly to survivors’ behaviour, while those appearing towards the bottom qualify killers’ behaviour. Terms positioned in the middle refer to behaviour that is equally manifested in both roles.

Figure 1. Diagram representing our classification of the less and most toxic behaviours associated to each role according to players’ perceptions (click image to enlarge).

We notice that both survivors and killers can display allegedly toxic behaviour. Killers’ toxic behaviour is mostly "passive": it is considered toxic when they stop moving, or when they immobilize a survivor. In acting in this way, killers seem to seek revenge for actions they deem illegitimate on survivors’ part, which can feed the toxicity loop.

For example, let us consider the practice of face camping. Hooking a survivor to cause them to lose all of their life points is killers’ most frequent killing technique. Face camping refers to a killer’s standing next to a hooked survivor for a long period of time. While this behaviour is a legitimate strategy to make sure that no survivor may come and unhook their teammate, several survivors criticize it. According to them, it goes against the unwritten rule that killers should attack other survivors instead of "wasting" their time guarding the ones they have hooked. In the case of killers, face camping often becomes a punishment or a way to retaliate for unjust behaviour. Face camping also secures a kill, which meets their primary objective (killing survivors), even though it is not the best strategy to win the game, given that speed and time management are a determining factor for success. Standing next to a survivor instead of aiming to kill the other three, or otherwise prevent them from escaping, is not an efficient strategy.

As for survivors, toxicity is witnessed in their "active" behaviour, such as attacking or mocking instead of hiding or fleeing away from the killer. While we would expect survivors to run away from the killer because they are vulnerable and because the context of the game says so (DbD is a horror game, and survivors should fear the killer), survivors may be perceived as toxic when they harass or run after the killer. Such behaviour is most often witnessed in expert players, who set new objectives for themselves that go against DbD developers’ intentions.

For instance, teabagging -- which refers to the act of repeatedly pressing "crouch" -- by survivors is often seen as toxic behaviour and a lack of respect for adversaries. Indeed, while crouching usually helps one hide from killers, it can be subverted to troll or anger killers, to try and make them lose patience or to push them or a teammate to react in a certain way. Survivors often teabag while they are protected by a window or pallet: obstacles give them time to engage in this behaviour, as killers must break or go around the window or pallet before they can reach toxic players.

Also, behaviour deemed to be most toxic is associated with survivors. While there are more survivors than killers in DbD, our analysis shows that their behaviour is considered to be more toxic than killers’ behaviour. This observation is supported by the fact that a majority of active users on the subreddit state that they mostly play as killers.

Lastly, it appears that some types of behaviour are widely accepted within the community, even if some players judge them to be toxic. In other words, players legitimize seemingly toxic behaviour in the game. Thus, our choice to study reportedly toxic yet ultimately acceptable behaviour suggests that some minorities are more vocal than others about their disagreement with gaming practices. Their interpretation of criteria for toxicity may have influenced the selection process of our dataset.

4.3 Enabling Factors

In addition to analyzing players’ understanding of in-game behaviour, we also identified five key aggravating factors for toxicity in DbD. These factors are interrelated, in that they may echo and amplify each other. Yet, their relationship does not follow the linear progression that we propose in all cases. Empirical analysis should confirm or infirm the results of this content analysis. Nevertheless, we think that showing the progression of these five factors for perceived toxicity helps gain a better understanding of how the community perceives the causes of in-game toxicity, and what factors increase the likelihood of toxic behaviour. This presentation will be followed by a broader discussion about these five factors in light of other games and the work of scholars identified at the beginning of the article.

4.3.1 Role Identification

First of all, the players’ comments analyzed suggest that the game’s design encourages players to identify with one of two roles: killer or survivor. This asymmetrical characteristic of DbD means that players must choose a role and keep playing it in order to master techniques and improve. First-person (for killers) or third-person view (for survivors), skins, actions and identity in each role both strengthen a sense of belonging to one role and reinforce distance from the other. Consistently playing as only one role results in a decreasing ability to understand adversaries’ tactics and issues, as well as a tendency to strongly identify with one’s own role in the game. Players are, thus, unable to put themselves in others’ shoes, which drives players apart and undermines empathy and understanding in some situations. The following quote, appearing in a post on the subreddit, adequately summarizes this point:

One thing I am going to recommend to survivor mains and killer mains alike: play some games on the other side of the aisle every once in a while. If you main survivor, play some killer. If you main killer, play some survivor. Looking at both sides of the spectrum is going to make you a more open minded player (User 1, 2018) [9].

Confinement to one of two roles contributes to the trivialization of toxicity, which is perceived as self-defence against one’s opponent, especially when one believes that their actions are harmless because they cannot see how they may negatively impact others. In other words, lack of gaming experience in the other role and a strong sense of belonging to one’s preferred role can encourage and normalize toxic behaviour, as players do not identify opponents’ negative experiences.

4.3.2 Ambiguity in Objective Setting

Second, our results reveal that players may define victory in different and ambiguous ways. Whichever role they decide to play, players have their own idea of what counts as victory. As far as killers are concerned, kills would define victory. Survivors would be said to win when they successfully escape. Yet, the situation is more complex than it seems, and the community distinguishes between a range of ‘good’ victories and playing styles. For instance, some killers consider winning to mean killing all survivors (four kills), while others consider two kills and resource collection enough to win. Some survivors consider themselves to have won only if the whole team escapes, while others want to complete certain tasks beyond their main goal in order to improve their avatar’s stats.

Victory criteria shape players’ expectations and playing styles. For example, a killer whose aim is to perform four kills will play much more strategically and aggressively than another who will be happy with two. This affects the overall dynamic and impacts opponents’ experience and enjoyment of the game. Survivors who play the game in their own interest will not always seek to help their teammates, which means that others will be less likely to enjoy the game or win as well. In addition to objectives that each role dictates, players may act according to victory criteria defined on a metagaming level. For instance, both killers and survivors engage in farming. Opponents may even help each other in doing so, which further obscures victory criteria.

Such changeability necessarily affects relationships between players during games, and often unexpectedly so, as all five players may simultaneously hold conflicting views. This is compounded by the fact that even Behaviour Interactive’s definition of official objectives in DbD remains ambiguous. Moreover, collective and consensual understanding of the "correct" objectives and playing styles becomes all the more blurry, as in-game communication tools are scarce. In other words, achieving harmonious objectives and agreeing on a team’s main goals before the game starts is difficult: farming, killing/ escaping, testing out a new avatar, etc. This challenge affects console players the most, as they do not have access to a chat box during the game [10].

Few actions are available to players who wish to communicate their intentions during a game (emotes, crouch, etc.), and metacommunication codes vary from one player to the next. Learning metacommunication tools thus becomes necessary to ensure mutual understanding during the game. However, the meaning of these codes is unstable within the community, which generates confusion and frustration upon attempting to determine objectives. For instance, survivors sometimes repurpose certain mechanics to "hook flap," quickly and repeatedly pressing the "self-unhook" key. This message to teammates may be interpreted in contradictory ways: the killer is approaching, or the killer is not here.

Similarly, repeatedly crouching can mean several things: disrespect (teabagging), gratitude (signifying "thank you"), salutations, etc. This ambiguity is summed up in the following quote from a subreddit post:

Teabagging as a survivor is basically your only way of communication that is easily noticeable to other survivors nearby besides the 2 hand motions. It means a lot of things. When you load in, you gotta teabag as a greeting to other survivors. If you randomly encounter a survivor, you gotta teabag. Or if you point a direction to point something out, you teabag and wait for the other survivor to teabag back to "affirm" they understand. Like pointing at a trap--point, teabag a bunch, maybe some head nodding, then an affirmative teabag back from the other survivor(s). Teabag as thanks for a heal. Teabag as thanks for a hook save (User 2, 2018) [11].

All in all, personal objectives affect ways of playing: while possible objectives are many, players’ expectations vary greatly. While the killer’s and the four survivors’ expectations can align, they can also clash. The ambiguity of the conditions for victory and the fact that it is difficult to reach a consensus prior to the start of a game can lead to contrary play, that is "playing the game outside of what is intended by most players" (Cook, et al., 2018, p.3329), confusion, tension and potentially toxic behaviour.

4.3.3 Individual Gaming Experience

According to our study of the players’s perceptions, the third aggravating factor is the fact that the gaming experience is mostly individual. Indeed, the game prioritizes an individual understanding of the rules and objectives, as well as an "everyone for themselves" approach. This individualistic view of the game’s goal -- that is to say, where the individual is more preoccupied with their own experience of the game than others’ (teammates or opponents) -- certainly originates in the polarization of interests within the community, in heated discussions outside of the game and in the limitations of communication tools. It also results from design choices made by Behaviour Interactive such as the fact that players are left to their own devices before and after the game.

When a game ends, players earn points and win or lose individually. They are not encouraged to remain longer and watch others play, as this may be considered a waste of time (except for friends playing in "survive with friends" mode). Consequently, players cannot bond for any significant length of time; they are reinforced in an individualistic logic of loot and bloodpoints accumulation. The absence or scarcity of communication tools exacerbates this situation.

Therefore, teammates and opponents become catalysts for individual pleasure, which may expedite the acceptability and normalization of toxicity. This may explain why text chatting in the lobby after a game gives way to some of the most toxic interactions. Not only do players already negatively perceive their opponents and lack an adequate understanding of others’ objectives in the game (whether they play the same role or a different one), but if players do not play as one "expects" them to, thus failing to satisfy other individuals, then the chat box becomes the perfect place to express one’s discontentment after the game. Players -- according to our dataset, mostly survivors -- will shower their target (their opponent(s) or teammate(s)) with accusations, leaving little room for responses or dialogue. Among these accusations, problematic behaviour will often be addressed from an individualistic perspective.

4.3.4 Task Repetition

From the comments analyzed for our research, we identified another potential intensifying factor for toxicity: the fact that tasks are repetitive. After spending many hours playing the game, players come to master its main dynamics, and subvert their meaning in order to develop new tactics that may become toxic. The fact that popular streamers encourage such practices confirms our observation.

Dead by Daylight becomes repetitive for those who play a lot, regardless of roles played, which can lead to boredom. Following Csikszentmihalyi’s flow approach (1990), challenges and actions must balance out; too few challenges leads to boredom. Players thus start seeking pleasure and increased interaction with their opponents or partners in other ways, while setting new challenges, for instance. In such cases, nagging the killer or a survivor is a new experience that may be more exciting and satisfying than repairing generators (survivors have to repair generators in order to escape) or running after other players (killers’ main goal). Players thus reinvent their own ways of playing or even create role reversal situations: survivors start "running after" killers, for instance, or killers stop moving. This becomes a "game inside of the game," as experienced gamers refine what they deem too simple and add new objectives that may lead to toxic behaviour.

4.3.5 Rigidity of Norms

Finally, our data analysis revealed that toxicity worsens as norms become more rigid. On top of confining and identifying themselves to one of two groups, both subcommunities (killers and survivors) fashion diverging, if not contradictory rules, norms and ideas about the game. These norms reflect each subcommunity’s values and offer criteria for toxicity. As players learn these norms, they also achieve a sense of belonging to the group that most identifies with them.

The more experience a player gains, the more knowledge they acquire, and the more their expectations increase regarding social norms and codes. Players thus expect their adversary and teammates to be "good" killers and survivors according to these implicit rules. Otherwise, players failing to respect now-rigid norms, especially according to expert players, may be penalized, often through toxic retaliation.

However, there is more than one consensual and applicable code. Roles, main objectives, experience and willingness to respect ‘official’ mechanics rather than subverting them, among other factors, can explain such variability. Therefore, there may be as many codes and norms as there are subcommunities. This is supported by the amount of accusatory conversations observed on the subreddit. For example, players from one subcommunity may criticize a certain kind of in-game behaviour (e.g. slugging) while others, from another subcommunity, may criticize this criticism, which shows diametrically opposing ways of interpreting behaviour during play.

In short, considering our interpretation of the community’s perceptions of in-game behaviour, we suggest that there is a potential gradation of aggravating factors for behavioural toxicity among players, relative to their level of experience with DbD: 1) Role identification; 2) Ambiguity in objective setting; 3) Individual gaming experience, 4) Task repetition 5) Rigidity of norms. Indeed, the more a player is experienced in DbD, the more susceptible he is of being affected by these five aggravating factors and, thus, of displaying toxic behaviour.

5.0 Discussion

Several of our findings echo the work of other scholars. First, as several researchers have noted (Foo & Koivisto, 2004; Warner & Raiter, 2005; Achterbosch, et al., 2013), categorizing toxic behaviours is difficult because that process depends on consensus-building within each videogame’s community (or communities). For example, being away from keyboard (AFK) is generally considered as toxic, but our study shows that this is not the case in DbD. This characteristic of gaming toxicity is particularly visible in researchers’ struggle to establish a precise list of toxic behaviours that would apply to all games. If behaviours like flaming and harassment are more commonly seen as unacceptable across gaming communities, it would be dangerous to ignore the power that communities have to negotiate new norms of socially acceptable behaviour. In this paper, our premise was that absolute categorization is impossible: we are concerned, rather, with exploring how communities set their own criteria for social acceptability.

Second, all enabling factors for toxicity are consistent with observations previously made by other scholars. (1) Identification with one role or another (survivor or killer) can be linked to the lack of empathy implicit in most definitions of toxicity in game studies (Mulligan & Patrovsky, 2003; Lin & Sun, 2005; Chesney, et al., 2009; Achterbosch, et al., 2013). Similarly, researchers studying virtual worlds (e.g. Second Life (Linden Lab, 2003)) and MMORPGs (e.g. World of Warcraft (Blizzard, 2004)) also found role identification to be a defining element of toxic behavior. In the first section of this paper, we summarized these definitions using three main concepts: intentionality, decreased pleasure for the victim and increased pleasure for the toxic player. If, for example, someone only plays as a survivor (and, therefore, only knows one side of the game), it is possible that they will not know how their behaviour affects the killer. In lacking empathy for their opponents, players may act in ways that ruin the game for the other side.

(2) The ambiguity of the goals can be discussed using the three types of rules: game mechanics, company guidelines and implicit rules as defined by players (Foo & Koivisto, 2004). Salen and Zimmerman also define the rules of a game on three levels, the last being "the 'unwritten rules' of etiquette and behaviour that usually go unstated when a game is played" (2004, p.179). These rules, while essential to the game, are difficult to clearly understand because they are "unstated… contested and emergent, continuously shifting and evolving" (Suzor & Woodford, 2013, p.3).

In DbD, Behaviour Interactive does not give clear indications as to what constitutes victory or defeat (second type of rules). Therefore, players must define objectives by themselves. Since these are based upon the interpretation of explicit rules (second type), the implicit rules are also ambiguous. Therefore, DbD players cannot be sure that they all have the same understanding. Because community members cannot explicitly agree on common goals, confusion may arise about each party’s expectations, which can trigger accusations of disruption. These socially implicit rules (third type) are similar to seasonal meta (the "optimal" style of play established by the community) in competitive games such as League of Legends (Riot, 2009), which creates debates in the player community.

(3) The fact that victories and defeats are individual in nature can amplify the first factor (lack of empathy). As previously mentioned, in DbD, bloodpoints are the most important currency because players use them to unlock powers and items. Players obtain them on an individual basis: (1) if a survivor manages to flee, but the others dies, the player still wins bloodpoints for surviving; (2) if a survivor unhooks another survivor in front of the killer, thus leading the unhooked survivor to a quicker death, they still win bloodpoints for unhooking an ally. While the game offers bloodpoints for teamwork, it is possible to simultaneously use these mechanics to farm bloodpoints and undermine teammates’ efforts. These features encourage players to act selfishly, which can lead to a lack of empathy for other players. These types of game mechanics are seen in other games, like in World of Warcraft where mechanics of loot repartition allow (and encourage) players to act selfishly by stealing rewards from others.

(4) Repetitiveness during games can lead bored and/ or experienced players to seek new challenges, such as creating a game within the game. Players can create new implicit rules (Foo & Koivisto, 2004; Salen & Zimmerman, 2004) that inform their gameplay. In this case, they are not playing the same game as the other players, which can result in contrary and disruptive play. This can, over time, be linked to the idea of trolling (a term with strong associations with toxicity in videogames) as a game (Donath, 1999; Hardaker, 2010; Condis, 2018). Researchers have argued that, to a certain extent, trolling is a type of game in which the troll tries to make their victim react or lose control. Some toxic behaviours manifested in DbD, such as directly engaging the killer instead of running away from them, is an example of a game within a game for expert (and possibly bored) players, which is perceived as toxic. While increase in mastery of the game (Deci & Ryan, 2012) should decrease toxic behavior (Kasumovic & Kuznekoff, 2015), boredom also leads to research of challenging experiences (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990), in the specific form of additional rules or toxic behavior such as running toward (instead of from) the killer.

(5) The rigidity of expectations from other players can be linked with intolerance for other styles of play or for players deviating from established "meta." The more experienced a player becomes, the more they will have a clear understanding of social norms (Foo & Koivisto, 2004; Suzor & Woodford, 2013) concerning their main role. They will know exactly what their role entails and their possible scope of action, as well as other players’ expectations towards the role. Their expertise in "official" social etiquette can render their practice more rigid, and potentially make them intolerant of "deviant" ways of playing, which may result in discriminatory comments and actions aimed at other players. Similarly, many online game communities (e.g. EVE Online (CCP Games, 2003) and Overwatch (Blizzard, 2016)) are difficult to enter precisely because the players are expected to already know what they are supposed to do, without anyone telling them. Experienced players are intolerant to "newbies" (or "noobs") because they do not behave like they are supposed to. This point is compounded by the fact that ranks are reset once a month, which means that experienced and possibly more rigid players will often play with new players.

It is also interesting to note that, contrary to many games, the toxicity of DbD’s community seems to increase as a player becomes more experienced. According to players, the most toxic ranks in a competitive game are usually the lowest ones due to the learning curve (LeJacq, 2015), but the opposite is true in Dead by Daylight. The fourth and fifth aggravating factors for toxicity in DbD explain this, which shows that some gaming communities have their own specificities. This also calls for further examination.

6.0 Limitations and Avenues for Further Research

While our research produced useful insights into causes and factors for toxicity, in examining perceptions and intentions that encourage DbD players to either intensify or counter toxic behaviour, it is not without limitations. First of all, we only examined one online platform (a subreddit), which restricts our understanding of toxicity within the DbD community. Indeed, leaving aside players who do not engage in discussions (lurkers), the community is active on several other subreddits and platforms (the official forum, Steam, YouTube, etc.), the study of which would paint a more comprehensive picture of how toxicity is perceived. Besides, the active subcommunity on this specific subreddit may display some characteristics of the medium (Mills, 2017; Glenski, et al., 2018).

Indeed, Reddit has been studied as an inherently toxic platform. Many scholars have said that Reddit informs behavior and aggravates the prevalence of toxic behaviors by its design choices (Bergstrom, 2011; Massanari, 2017; Buyukozturk, et al., 2018). Moreover, Reddit’s ranking system may encourage an "echo chamber" effect (Mills, 2017; Glenski, Pennycuff, & Weninger, 2018). This ranking system (with upvotes and downvotes) implies that minority opinions are less visible, which means they will be consulted less often. This may discourage players from expressing marginal opinions. Despite our attempt to limit this bias by studying both the most and the less popular comments within selected discussions, it is possible that our results were influenced by these echo chambers and by the negativity of Reddit.

Further, our dataset is limited to the release of one chapter, which does not allow exploring how sentiments may evolve over time with regards to different types of behaviour, or how new content affects, promotes, or decreases perceptions of toxicity. Moreover, Behaviour Interactive organized two events [12] within the timeframe under study, which may very well have affected players’ behaviour and their perception of others’ behaviour.

Additionally, as we studied comments made out of the game setting, results reflect players’ perceptions of in-game behaviour rather than behaviour itself. This paper does not confirm or infirm the prevalence of toxic behaviour using in-game behavioural data. This means that accounts of toxic behaviour may not match actual occurrences, or adequately reflect their importance and the circumstances in which behaviour was witnessed during a game. We only considered players’ perceptions, and we did not verify assertions using other sources of information.

Lastly, we have our own bias and ways to approach and study the subject matter as scholars. Our understanding of toxicity and community dynamics follows previous research on these topics. This influenced the way in which we encoded data and analyzed results, and especially the list of behaviour we would consider as toxic before beginning the targeted data collection process on the subreddit.

Both the results and the limitations of our research actually reiterate the vagueness of the definition of toxicity. We can, indeed, address and study it in various, sometimes uneven, if not incompatible ways. Research fields, goals (whether scholarly or set by the industry) and methods, as well as the community and datasets under study all contribute to our particular understanding of toxicity as a phenomenon.

Indeed, the findings of the research show that qualitative content analysis of social media posts is a valid method to study online gaming communities. To expand the findings, quantitative content analysis would also be interesting. For instance, quantitative content analysis of social media posts is used by many scholars (e.g. Schatto-Eckrodt et al., 2020 ; Unkel & Kümpel, 2020) to study public and community debates about various subjects, therefore deepening the understanding of these issues. Comparing our results, for example, with an automated content analysis of out-of-game data (which we have begun to experiment by training an automated encoding program) will offer a better understanding of the community’s perception of toxic behaviour inside of the game.

In this sense, cross-referencing the results with other types of data and new sources of information as part of subsequent research will be necessary in order to address some shortcomings inherent to our research methods. Other research avenues, such as studying in-game behavioural data collected by the game's developer, would allow assessing which groups are toxic or collaborative: players with more or less than X hours of playtime, killers or survivors, PC or console players, etc. Moreover, cross-referencing will determine whether players’ perceptions and in-game practices match. For example, we could calculate the prevalence of teabagging from survivors towards killers (number of "crouch" inputs near the end of a match) and compare these numbers with our analysis of the behaviour’s interpretation on the subreddit. Also, contrasting the interpretation of behaviour out-game with the prevalence of behaviour in-game will allow evaluating the echo chamber effect, which will contextualize our results within the framework of this subreddit’s characteristics (as a subcommunity).

More broadly, studying other steps in the development of the game, and other chapters, would also help gather pertinent information because modifying game mechanics and features can affect research results. We could then consider presenting longitudinal results and examine how players’ perception of toxic behaviour changes. A semiotic analysis of the game’s features, interviews with players, streamers and game developers, additional content analysis on other popular social media and discussion platforms, or an analysis of Behaviour Interactive’s marketing discourse would also give us a comprehensive toolset to better understand the phenomenon of toxicity in DbD.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our translator, Lucile Crémier (Semiotics, UQAM) as well as the reviewers and editors of this journal for their helpful comments. We also thank the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and research organization MITACS for their support.

Endnotes

[1] Identifying the "objective" causes and factors inside of the game (through players’ behaviour for example) requires a research on its own. The results, similarities and discrepancies could then be compared with the players’ perceptions of in-game toxicity.

[2] Behaviour perceived as most toxic is defined and discussed in section 3.2.

[3] We used https://redditsearch.io/ to identify pertinent topics, using keywords and our search criteria. However, once we had gathered these entries, we still had to read them to ensure they fit our objectives and criteria.

[4] Reddit allows upvoting (+1) and downvoting (-1). Thus, some comment or content’s score may be positive or negative, and change over time.

[5] While the encoding was led by one researcher, the main questions, methods, and coding grid stem from two previous research (Bonenfant, et al., 2017; Bonenfant, et al., 2019) involving a team of four people (which includes the researcher that conducted the encoding for this article). The encoding process for this research was thus validated and improved over several years.

[6] "Sentiment" refers to computerized "sentiment analysis." Hutto and Gilbert (2014) explain that "sentiment analysis, or opinion mining, is an active area of study in the field of natural language processing that analyzes people's opinions, sentiments, evaluations, attitudes, and emotions via the computational treatment of subjectivity in text."

[7] Herein, the word "community" is used in reference to the users participating in the DbD subreddit. These are users that feed and maintain their community by communicating with each other on a specific social media about their mutual object of interest (Dead by Daylight). Therefore, our results do not aim to account for the perceptions of the community as a whole since different members participate in different digital platforms beyond Reddit: YouTube, Twitch, DbD's official forum, Twitter, etc.

[8] This behaviour, as well as other potentially toxic attitudes, are described in section 3.2, following established definitions (Table 1).

[9] www.reddit.com/r/deadbydaylight/comments/9n2a85/heck_you_campers/ (last accessed on 13 March 2019).

[10] Some of these players send private messages (on PlayStation Network, for instance) in order to communicate that information before or during the game.

[11] www.reddit.com/r/deadbydaylight/comments/9ow8ev/psa_if_a_fellow_survivor_teabags_at_you_you_have/ (last accessed on 13 March 2019).

[12] The Hallowed Blight (from 19 October 2018 to 2 November 2018) and Blood Rush (from 5 November 2018 to 12 November 2018) set new objectives, including resource accumulation.

References

Achterbosch, L., Miller, C., Turville, C., & Vamplew, P. (2014). Griefers Versus the Griefed -- What Motivates Them to Play Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games? The Computer Games Journal, 3(1), 5-18.

Achterbosch, L., Miller, C., & Vamplew, P. (2008). A Taxonomy of Griefer Type by Motivation in Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games. Behaviour & Information Technology, 36(8), 846-860.

Achterbosch, L., Miller, C., & Vamplew, P. (2013). Ganking, Corpse Camping and Ninja Looting from the Perception of the MMORPG Community: Acceptable Behaviour or Unacceptable Griefing? Proceedings of The 9th Australasian Conference on Interactive Entertainment: Matters of Life and Death19, 1-8. doi: 10.1145/2513002.2513007

Balci, K. & Salah, A. A. (2015). Automatic Analysis and Identification of Verbal Aggression and Abusive Behaviours for Online Social Games. Computers in Human Behaviour, 53, 517-526.

Bartle, R. A. (2007). What to Call a Griefer. Terra Nova. Retrieved from https://terranova.blogs.com/terra_nova/2007/10/what-to-call-a-.html

Behaviour Interactive. (2016). Dead by Daylight [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Ashley Pannell, Dave Richard, Mathieu Coté, published by Behaviour Interactive.

Bergstrom, K. (2011). "Don’t feed the troll": Shutting down debate about community expectations on Reddit.com. First Monday, 16(8).

Blackburn, J. & Kwak, H. (2014). STFU NOOB: Predicting Crowdsourced Decisions on Toxic Behaviour in Online Games. Proceedings of The 23rd International Conference on World Wide Web, 877-888. doi: 10.1145/2566486.2567987

Blizzard Entertainment. (2004). World of Warcraft [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Rob Pardo, Jeff Kaplan, and Tom Chilton, published by Blizzard Entertainment.

Blizzard Entertainment. (2016). Overwatch [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Jeff Kaplan, Chris Metzen, Aaron Keller, published by Blizzard Entertainment.

Bonenfant, M., Richert, F., & Deslauriers, P. (2017). Using Big Data tools and techniques to study a gamer community: Technical, epistemological, and ethical problems. Loading... The Journal of the Canadian Game Studies Association, 10(16), 87-108.

Bonenfant, M., Deslauriers, P., & Heddad, I. (2019). Methodological and Epistemological Reflections on the Use of Game Analytics toward Understanding the Social Relationships of a Video Game Community. In G. Wallner (ed.), Data Analytics Applications in Gaming and Entertainment. New York: Auerbach Publications.

Braithwaite, A. (2016). It’s About Ethics in Games Journalism? Gamergaters and Geek Masculinity. Social Media + Society, 2(4).

Buyukozturk, B., Gaulden, S., & Dowd-Arrow, B. (2018). Contestation on Reddit Gamergate and Movement Barriers. Social Movement Studies.

CCP Games. (2003). EVE Online [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game published by Simon & Schuster.

Chesney, T., Coyne, I., Logan, B., & Madden, N. (2009). Griefing in Virtual Worlds: Causes, Casualties and Coping Strategies. Information Systems Journal, 19(6), 525-548.

Condis, M. (2018). Gaming Masculinity: Trolls, Fake Geeks, and the Gendered Battle for Online Culture. Iowa City: University Of Iowa Press.

Consalvo, M. (2012). Confronting toxic gamer culture: A challenge for feminist game studies scholars. Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology, 1.

Connell, R. (1983). Which Way is Up? Essays on Sex, Class, and Culture. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin.

Connell, R., Ashenden, D., & Kessler, S. (1982). Making the Difference: Schools, Families and Social Division. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin.

Cook, C., Schaafsma, J., & Antheunis, M. (2018). Under the bridge: An in-depth examination of online trolling in the gaming context. New Media & Society, 20(9), 3323-3340.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience (Vol. 1990). New York: Harper & Row.

de Mesquita Neto, J. A. & Becker, K. (2018). Relating Conversational Topics and Toxic Behaviour Effects in a MOBA game. Entertainment Computing, 26, 10-29.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Self-determination theory. In Handbook of theories of social psychology, Vol. 1 (pp. 416-436). Sage Publications Ltd.

Donath, J. S. (1999). Identity and Deception in the Virtual Community. In M. A. Smith & P. Kollock (Eds.), Communities in Cyberspace (pp. 37-68). London: Routledge.

Fair Play Alliance. (2018). Frequently Asked Questions. Fair Play Alliance. Retrieved from http://www.fairplayalliance.org/#faq.

Foo, C. Y. & Koivisto, E. M. I. (2004). Defining grief play in MMORPGs: Player and developer perceptions. Proceedings of the 2004 ACM SIGCHI International Conference on Advances in Computer Entertainment Technology, 245-250. doi: 10.1145/1067343.1067375

Fox, J., & Tang, W. Y. (2017). Sexism in video games and the gaming community. New

Perspectives on the Social Aspects of Digital Gaming: Multiplayer, 2, 115-135.

Fox, J. & Tang, W. Y. (2016). Women’s experiences with general and sexual harassment in online video games: Rumination, organizational responsiveness, withdrawal, and coping strategies. New Media & Society, 19(8), 1290-1307.

Gray, K. (2013). Collective Organizing, Individual Resistance, or Asshole Griefers? An

Ethnographic Analysis of Women of Color In Xbox Live. Ada New Media.

Hardaker, C. (2010). Trolling in Asynchronous Computer-Mediated Communication: From User Discussions to Academic Definitions. Journal of Politeness Research, 6(2), 215-242.

Kasumovic, M. M., & Kuznekoff, J. H. (2015). Insights into Sexism: Male Status and

Performance Moderates Female-Directed Hostile and Amicable Behaviour. PLOS ONE, 10(7), e0131613.

Kwak, H. & Blackburn, J. (2014). Linguistic Analysis of Toxic Behaviour in an Online Video Game. Proceedings of the SocInfo 2014 Workshops: International Conference on Social Informatics, 209-217. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-15168-7_26

Kwak, H., Blackburn, J., & Han, S. (2015). Exploring Cyberbullying and Other Toxic Behaviour in Team Competition Online Games. Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 3739-3748. doi: 10.1145/2702123.2702529

LeJacq, Y. (2015, March 25). How League of Legends Enables Toxicity. Kotaku. Retrieved from https://kotaku.com/how-league-of-legends-enables-toxicity-1693572469.

Lin, H. & Sun, C.-T. (2005). "White-Eyed" and "Griefer" Player Culture: Deviance Construction in MMORPGs. Proceedings of the Digital Games Research Conference 2005, Changing Views: Worlds in Play.

Linden Lab. (2003). Second Life [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game published by Linden Lab.

Märtens, M., Shen, S., Iosup, A., & Kuipers, F. (2015). Toxicity Detection in Multiplayer Online Games. Proceedings of The 2015 International Workshop on Network and Systems Support for Games (NetGames), 1-6. doi: 10.1109/NetGames.2015.7382991

Massanari, A. (2017). #Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s Algorithm, Governance, and Culture Support Toxic Technocultures. New Media & Society, 19(3), 329-346.

McClean, D., Waddell, F., & Ivory, J. (2020). Toxic Teammates or Obscene Opponents? Influences of Cooperation and Competition on Hostility between Teammates and Opponents in an Online Game. Journal of Virtual Worlds Research, 13(1), 1-15.

Milner, R. M. (2011). Discourses on Text Integrity: Information and Interpretation in the Contested Fall out Knowledge Community. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 17(2), 159-175.

Mulligan, J. & Patrovsky, B. (2003). Developing Online Games: An Insider’s Guide. San Francisco: New Riders.

Przybylski, A. K., Deci, E. L., Rigby, C. S., & Ryan, R. M. (2014). Competence-impeding electronic games and players’ aggressive feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(3), 441-457.

Riot Games. (2009). League of Legends [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Andrei van Roon, Steven Snow, Travis George, published by Riot Games.

Saarinen, T. (2017). Toxic Behaviour in Online Games (Master’s Thesis). Retrieved from Jultika.

Salen, K. & Zimmerman, E. (2004). Rules of Play. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Salter, A., & Blodgett, B. (2017). Toxic Geek Masculinity in Media: Sexism, Trolling, and

Identity Policing (1st ed. 2017 édition). Palgrave Macmillan.

Salter, M. (2017). From Geek Masculinity to Gamergate: The Technological Rationality of Online Abuse. Crime, Media, Culture, 14(2), 247-264.

Schatto-Eckrodt, T., Janzik, R., Reer, F., Boberg, S., & Quandt, T. (2020). A Computational

Approach to Analyzing the Twitter Debate on Gaming Disorder. Media and Communication, 8(3),

205-218.

Shen, C., Sun, Q., Kim, T., Wolff, G., Ratan, R., & Williams, D. (2020). Viral vitriol: Predictors and contagion of online toxicity in World of Tanks. Computers in Human Behavior, 108(2020), 106343.

Shores, K. B., He, Y., Swanenburg, K. L., Kraut, R., & Riedl, J. (2014). The Identification of Deviance and its Impact on Retention in a Multiplayer Game. Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, 1356-1365. doi: 0.1145/2531602.2531724

Suzor, N. & Woodford, D. (2013). Evaluating Consent and Legitimacy Amongst Shifting Community Norms: An EVE Online Case Study. Journal of Virtual Worlds Research, 6(3), 1-14.

Tang, W. Y., & Fox, J. (2016). Men’s harassment behavior in online video games: Personality traits and game factors. Aggressive Behavior, 42(6), 513-521.

Tang, W. Y., Reer, F., & Quandt, T. (2020). Investigating sexual harassment in online video games: How personality and context factors are related to toxic sexual behaviors against fellow players. Aggressive Behavior, 46(1), 127-135.

Unkel, J., & Kümpel, A. S. (2020). (A)synchronous Communication about TV Series on Social

Media: A Multi-Method Investigation of Reddit Discussions. Media and Communication, 8(3), 180-190.

Todd, C. (2015). Commentary: GamerGate and Resistance to the Diversification of Gaming Culture. Women’s Studies Journal, 29(1), 64-67.

Warner, D. E. & Raiter, M. (2005). Social Context in Massively-Multiplayer Online Games (MMOGs): Ethical Questions in Shared Space. International Review of Information Ethics, 4(7), 46-52.