Player customization, competence and team discourse: exploring player identity (co)construction in Counter-Strike: Global Offensive

by Matilda Ståhl, Fredrik RuskAbstract

The growing esports scene brings a level of professionalism to gaming. Games that, previously, used to be a spare time activity have now become professional and educational contexts, as exemplified in this study. In these contexts, player identities in online games are actively, and contextually, (co)constructed in and through the in-game interaction with both the game itself, as well as with co-players.

In this ethno-case study (a qualitative case study informed by ethnographic methods), a player centred approach offered a participant’s perspective on local player identity (co)construction in the multiplayer first person shooter (FPS) Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (henceforth, “CS:GO”). This paper sought to answer two research questions: What tools for (co)constructing player identity in CS:GO did participants employ? and: What player identities are (co)constructed using these tools?

The data was collected in collaboration with a vocational school with an esports programme in Finland in 2017-2018. Seven students (aged 17-18, all white and identifying as male) playing CS:GO took part in the study by sharing screen recordings of their in-game matches (ten matches and almost six hours in total) and by taking part in interviews (seven in total). The participants were part of two teams and the in-game data was analyzed from two students’ perspectives, one from each team.

Based on the participants’ in-game discussions and interviews, relevant situations in relation to identity (co)construction were transcribed and analyzed inductively. The participants employed the following tools for identity (co)construction in CS:GO; choice of weapon, weapon skill, weapon customization, stats/rank and language use. These tools were employed to (co)construct identities connected to player customization, competence and team discourse. Although there are individual variances, the identities (co)constructed orient towards a perceived competent player identity shaped by technomasculine norms in online game culture, where traits that connote femininity and queerness are seen as signs of incompetence.

Keywords: Identity construction, videogames, first person shooter, ethno-case study, technomasculinity

1 Introduction

The first-person shooter (FPS) game genre is popular (Kinnunen, Taskinen & Mäyrä, 2020), and continues to be one of the main genres within esports (T. L. Taylor, 2015). By studying participants online, in-game interactions through the lens of identity construction, research can further our understanding of online cultures in contemporary society. Although identity construction in videogames has been researched since Turkle's (1995) study on online identities, it can be considered fragmented (Ecenbarger, 2014). Games with customizable avatars and/or narratives, such as RPGs and MMORPGS, have been studied extensively in relation to identity (e.g. Gee, 2003), whereas research on identity construction within FPSs is limited with a few exceptions (Kiourti, 2018; Rambusch, Jakobsson & Pargman, 2007; N Taylor, 2011; Voorhees & Orlando, 2018; Wright, Boria & Breidenbach, 2002). Nevertheless, the first-person perspective offers high player immersion (Gray, 2018) and possibilities for constructing in-game identities; not through an avatar, but through the players’ “own eyes” (Mukherjee, 2012). In FPSs, identities, roles and competencies are typically (co)constructed through in-game communication; predominantly performed through voice and text chat. Similar to most games, FPSs simulate warfare. However, our focus is not on players simulating war, but on in-game communication in a context shaped by competitive gaming and education.

In-game communication can be a complex network of online and offline life where the player is socialized into the norms and hierarchies of multiplayer games (T.L. Taylor, 2009). In-and-through this socialization process, players have shown to rely on guidance from more experienced players (Rambusch et al, 2007; N. Taylor, 2016; T. L. Taylor, 2015; Rusk, Ståhl & Silseth, 2020; Wright et al, 2002). Videogames are seen as ‘new’ public spheres where learning is social and distributed (Gee, 2007) with the potential to develop competencies such as communication and adaptability (Barr, 2018). However, there is little educational research on cultivating and employing competencies within the competitive gaming scene (N. Taylor, 2016).

This study contributes to the limited research on identity construction within FPSs and furthers the empirical understanding of how players interact with each other and the game to (co)construct identities. In multiplayer FPSs, identity (co)construction is primarily done in the interaction with other players in the competitive gaming scene with its in-game norms and hierarchies. We argue that the identities (co)constructed by players within FPSs are worthy of researching not only to better understand the communities in FPSs, but esports in general -- especially as they here intersect with education. The overarching aim is to explore in-game identity (co)construction in the online FPS, CS:GO (Valve Corporation & Hidden Path Entertainment, 2012), within an esports and educational context. We employ ethnographic methods from game studies within a case study framework; a player centred approach on identity construction and engagement with a game within a professional and educational context. This paper seeks to answer two research questions: What tools for (co)constructing player identity in CS:GO did our participants employ? and: What player identities are (co)constructed using these tools? Finally, these identities are discussed in relation to the game context, the norms of online game culture and the educational context.

2 Theoretical frameworks

This study employs a participant’s perspective on identity (co)construction in interaction. Identities are simultaneously ascribed to oneself and to others. Without a certain amount of stability, identities tend to lose their social function, yet they are not constant but ever-changing (Chilton, 2014). Identities are not seen as static, but rather as fluid, multiple and emergent in social interaction (Kopytowska & Kalyango Jr, 2014). They are continually (re)negotiated and (co)constructed in social contexts (Banjeree & German, 2014). Accordingly, we use identity (co)construction as the key concept in order to include two parallel processes of identity construction; the individual and the group identity construction.

In order for communication to work, each individual interprets the information that co-participants provide about themselves when communicating. This communication is done through appearance and interaction (Shulman, 2017). Visually, appearance in video games is primarily expressed through an avatar (e.g. Gee, 2003) or player customization; in CS:GO, some tools are free and others are available for purchase. Selling virtual goods, such as skins in CS:GO, has become an integral part of the business model for games with a free game core (Hamari et al, 2017). Emotional and social values appear to be the two major reasons for purchasing in-game goods for customization (Hamari et al, 2017) and are therefore connected to constructing in-game identities.

Videogames are traditionally white male arenas with limited access and representation for female identifying players, players of colour as well as queer identifying players (Corneliussen, 2008; Gray, 2018; Nakamura, 2009; N. Taylor, 2011; N. Taylor & Voorhees, 2018; T. L. Taylor, 2015). However, the dominant stereotype of the online gamer as an antisocial male teenager is not supported by empirical research on player demography (Kowert, Festl & Quandt, 2014). Current gender norms limit the association between “tech savvy, digital play, and femininity,” (Harvey, 2015, p.137) where acquiring competence can be limited by discourses of gaming or technology being portrayed as a masculine form of expertize; or technomasculinity. As the hegemonic gender structure in game contexts, traits aligning with technomasculinity are promoted, while conflicting traits that connotates with, for example, femininity and queerness are not (Johnson, 2018).

Female access to gaming arenas tends to be more generous in low-stakes contexts and decreasingly in more competitive contexts (Sveningsson, 2012). There appears to be a prevailing idea of competent esport players as competitive young men, sporting traits that align with “antagonistic competitiveness and heterosexual virility” (Witkowski, 2018, p. 188). Further, female online players tend to rate their skills as inferior to those of their male co-players, although it is commitment and not gender that mainly determines player competence (Ratan, Taylor, Hogan, Kennedy & Williams, 2015). Preconceptions from everyday life can affect online games as some players use derogatory words for sexual minorities as slander and thereby reinforce a negative view of the LGBTQ community. This practice reinforces the norm of heteronormativity and is used frequently enough to be considered standard “gamer lingo” (Pulos, 2013) or even a game within the game (Vossen, 2018). Nevertheless, the ideal of a male player is pervasive in online games; even in explicitly LGBTQ inclusive groups, the player is presumed to be a (gay) man (Sundén, 2012).

In some games, such as FPSs, the lack of characterisation might lead to less identification with a character and rather with a role (Fine, 1983). In CS (2000), skill development was connected to player identity and prominent players considered their play as more serious (Rambusch et al, 2007). Voorhees and Orlando (2018) analyzed how militarized masculinities were performed in a professional team and their roles. The roles were; the entry fragger: the first player into the fight trying to secure a kill, the AWPer: the player wielding the sniper rifle for longer distance kills, the lurker: the player that collects information about the opponent’s movements, the support: the player supporting the other players (usually the entry fragger) and finally the strat caller: the team leader. Performing militarized masculinity tend to correspond with the in-game role. For example, the AWPer has “constructed the persona of a cold, hard killer, a guy who is too tough for words,” (Voorhees & Orlando, 2018, p.218) indicating that not only gender but in-game role are connected to players’ identities. Furthermore, Voorhees and Orlando (2018) noted that same-sex relationships between the, allegedly, heterosexual team members were hinted at to create excitement among the fans. Accordingly, in the competitive gaming scene formed by militarized (techno)masculinity, homosexuality can be regarded a marketing ploy rather than a person’s sexual orientation and part of their identity.

In summary, we see identities as changing and part of social interaction, and player identity (co)construction as shaped by factors such as in-game customization and role, as well as gender and sexual orientation. This theoretical framework shapes our approach to identity (co)construction in CS:GO within an esports and educational context. However, here the focus is on activities within the in-game social context and not all social contexts (and thereby identities) that the participants engaged with.

3. Method and methodology

The data was collected in collaboration with a vocational school in Finland that the participants (17-18 years old) attended. The participants studied esports as a minor subject but did not play videogames together during lessons. As school representatives, they were encouraged to play together as a team in their spare time on a weekly basis. The teammates and the game, in particular, might not be their primary choice otherwise. Activity during the entire program was required to get course credits. Here, the program functioned as access point to active players with a serious interest in videogames. The matches recorded were played in competitive mode, however, not as part of organized events.

3.1 Ethno-case study

This study is positioned as a qualitative case study informed by ethnography or ethno-case study (Parker-Jenkins, 2018). Case study as a methodology focuses on an immersed understanding of a phenomenon trough a specific case (Scwandt & Gates, 2018). By researching the activities conducted by an individual or a group, case studies can offer insight into how previous research and empirical data are connected (Cohen et al, 2005). The distinction between ethnography and case study as methodologies can be somewhat blurry, since they are somewhat overlapping. Both focus on a participant’s perspective of a phenomenon and use varied forms of data collection. However, in ethnography, more emphasis is put on extended periods of time in the field and gaining insight into this phenomenon from multiple contexts, whereas a case study can be more limited in terms of time and researcher immersion into the field (Parker-Jenkins, 2018). Access to the field might further be limited due to, for example, the researcher's age and gender. This “otherness” can limit researcher immersion into the phenomenon, as was the case in TL Taylor's (2015) work on esports and therefore that study was, unlike her previous work, not reported as an ethnography. Accordingly, as this study is positioned on the borderline between these methodologies, we consider it an ethno-case study and continue to situate our work alongside ethnographic research on the topic.

Ethnography as a methodology is evolving and contemporary ethnographies show that technology can offer new ways to comprehend online contexts (see e.g. Boellstorff et al, 2012; Pink et al, 2016). While there are variations in terms of approach, the core remains the same; that the social interaction taking place online is meaningful and worthy as a focus of an ethnographic study. In order to gain insight into these cultures, the ethnographer might need to adapt traditional methods or to employ new ones. Participant observation in a relevant context remains one of the core foundations of ethnography, however, observation is somewhat differently organised in a virtual field (Boellstorff et al, 2012). Doing ethnography online includes new demands on the researcher as the definition of fieldwork becomes blurry when the field is online and the researchers have access to it from their own devices (Beaulieu, 2007; Shumar & Madison, 2013). Fieldwork is no longer necessarily physically traveling to the context one wishes to explore, but a switching of roles. Furthermore, there is a need for new practices to achieve an insider perspective without necessarily having face-to-face interaction access to/with the participants.

Bennerstedt (2013) noted a tendency for normative approaches to game research where the results reflected what the researchers set out to find; as such, we endeavoured to apply a descriptive approach. Therefore, we approached identity construction from an ethnographic participant's perspective. In other words, the identity (co)construction in diverse virtual environments was understood as situated interactional negotiations and processes that needed to be recorded for later analysis, as they were done (Hall & Du Gay, 1996). First-hand experiences in relevant settings, often in combination with interviews, informs the ethnographer to access an insider’s perspective (Hammersley, 2006; Pole & Morrison, 2003), including online contexts (Parker-Jenkins, 2018).

Here, researcher immersion was obtained through the in-game screen recordings and corresponding interviews. Through the recordings, conducted by the participants on their own devices, the researcher could observe and re-observe in-game situations. During a number of interviews (see table 1), relevant recordings were discussed with the participants in order to confirm an insider’s perspective. The design was informed by the autonomy principle within ethnographic research (Murphy & Dingwall, 2001), as well as insights into ethnographic research design where participants take an active role (Ståhl & Kaihovirta, 2019; Rusk, 2019; Sahlström, Tanner & Olin-Scheller, 2019). The research approach was player centred (e.g. Kiuorti, 2019; Ratan et al, 2015; T. L. Taylor, 2009), which aligns with both ethnography and case-study. The focus remained on accessing a participant’s perspective of the game in question. This was emphasized by participants being in charge of the screen recordings. Playing in a setting of the participants’ own choice and on their own computers was considered a naturally occurring setting and was crucial from an ethnographic perspective (Hammersley, 2018).

Due to the visual complexity of the data, this study was further influenced by visual ethnography. Visuality is informed by cultural practices and visual ethnography focuses on images, video material and research online (Pink, 2013), with all three levels present in this study. Using visual material in interviews can facilitate an emic perspective (Barley and Russell, 2018) by video stimulated recall (Nguyen, McFadden, Tangen & Beutel, 2013). Visual material is further worthy of analysing in itself (Pink, 2013), here primarily in terms of weapon customization (see 4.1).

3.2 Context of the study

CS:GO is based on Counter-Strike (or “CS”) (Valve Corporation, 2000); a game that was originally a mod for Half-Life (Sierra Entertainment & Valve Corporation, 1998). The organized competitive culture that emerged around the original CS game (2000) transformed an individual pastime activity into something professional with a focus on teamplay (Rambusch et al, 2007). The game series Counter-Strike remains popular in Finland; listed seventh among the most popular digital games in the Finnish Player Barometer in 2018 and fifth in 2020 (Kinnunen et al, 2018; Kinnunen et al, 2020). The same survey noted that while playing games is as common among Finnish men as women, more men were defined as active players. The interest for esports is growing; in 2018, only 1.8 percent claimed to play in an esports setting and the corresponding number in 2020 was 2.8 percent. Further, there is a statistically significant increase in those who view esports occasionally: from 15.3 percent in 2018 to 19.6 percent in 2020.

There were three levels of communication in the data and two of these were provided by CS:GO. The game offered a text-based chat (TBC) with two modes: all chat (notifying all players) and team chat (notifying team only) as well as an internal voice chat (IVC) that was only available to the team. The IVC could be considered a bit impractical as the players had to press a key each time they wish to speak. Therefore, most players used an external voice chat (EVC) to speak with their in-game friends. In the data, both teams used a Discord channel to speak freely without the need to press a key. During matches when not all team members were present, they got assigned a temporary co-player, often referred to as a “random,” and these co-players are as a rule not invited to the Discord channel.

The EVC was used for most in-game communication within the team, with a few exceptions where the IVC and the TBC were used. Henceforth, only the players that were officially part of the team are referred to as team members and players that join them for one match are referred to as co-players.

3.3 Data selection

The focus students volunteered to participate in the study through a teacher. The data consisted of seven matches and four scheduled interviews per team, see table 1. Initially there were six focus students, however as part of team 1, John became part of the study in the last months of the data collection. The focus students recorded and shared their matches regularly with the researchers through a secure file sharing service. The design of the study was dependent on the students’ engagement due to the physical distance between the researchers and participants. Regular meetings, held at their school, functioned as interviews and were recorded; however, one interview was cancelled due to seasonal flu (see table 1). Stimulated recall (Nguyen et al, 2013) on relevant sequences from the screen recordings was employed during all interviews apart from the first, thereby providing the researcher with the participants’ thoughts and comments on certain in-game situations. Further, as these interviews took place in the participants' school, this provided further researcher immersion into the participants' everyday lives.

Table 1.

|

Team 1 (T1) |

Team 2 (T2) |

||||||

|

Martin |

John |

Joni |

William |

Jesper |

Emil |

Sebastian |

|

|

Match 1 |

x |

- |

x |

o |

o |

x |

x |

|

Match 2 |

x |

o |

x |

o |

o |

x |

o |

|

Match 3 |

x |

- |

x |

x |

o |

x |

x |

|

Match 4 |

x |

o |

x |

x |

o |

x |

x |

|

Match 5 |

x |

x |

x |

o |

x |

x |

x |

|

Match 6 |

x |

x |

x |

o |

x |

x |

x |

|

Match 7 |

x |

x |

x |

- |

x |

x |

x |

|

Interview 1 |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Interview 2 |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

|

Interview 3 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

* |

* |

* |

|

Interview 4 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

X = participated in the match, submitted a screen recording to the researchers

0 = participated in the match, did not submit a screen recording/issues with participant file

+ = participated in interview

- = did not participate

* = cancelled due to seasonal flu

The analysis focused on one member from both teams (see bolded participants in Table 1); allowing different perspectives on CS:GO. The other participants’ points of views functioned as secondary data in situations where the focused upon screen recordings were unclear. The other participants were present in the analyzed in-game data and all participants took part in at least two interviews, ensuring that their voices were also heard.

Choosing which participants’ perspectives to focus on was, largely, influenced by their presence during the interviews as these were the only face-to-face interactions between researcher and participant. The focus student on team 1 (T1), Martin (pseudonym), was the sole participant to submit videos of all matches and participate in all interviews, he was also considered the most experienced CS:GO player on T1 (see 4.2). The focus student on team 2 (T2) Jesper (pseudonym) took part in all seven matches yet there are only three recordings from his point of view due to technical issues. He was the only participant from T2 to take part in all three interviews.

With this selection in mind, a total of ten matches and almost six hours of data (05:44:09), with matches ranging from 27-44 minutes, were analyzed for this study. Both teams have submitted wins and losses, resulting in five wins and five losses in total. Seven matches were played on the map called Mirage and the remaining three were played on Dust II, Cache and Overpass. Both teams have submitted recordings from various maps.

3.4 Ethical perspectives

Ethically conducted research should avoid causing harm to participants and be beneficial for them when possible. Additionally, the participants should be treated equally and their decisions should be respected (Murphy & Dingwall, 2001). Several steps were taken to avoid that the research was perceived as an intrusion on the students’ privacy. These included standard research procedures in educational science; using pseudonyms instead of the students’ real names, and informing students, parents and teachers of the study’s aim and what participation entailed.

Due to online visibility connecting the participant's names, photos and gamertags, we could not, as ethically responsible researchers, publish the original gamertags. When discussing alternative pseudonyms, we noticed different interpretations of the original gamertags, for example, if it was interpreted as an adjective or as a noun. If we analysed an edited version of gamertags, then edited words would affect the results, since we as researchers might (intentionally or unintentionally) change the gamertags to align with certain results. Additionally, analyzing the original version but reporting the edited version, would result in a lack of transparency. As the usernames are chosen by the participants, an edited version might result in loss of meaning as the changed name does not address the same joke or association. However, as the importance of usernames/gamertags have been noted elsewhere (see e.g. Sveningsson, 2003; Wright et al, 2002) and gamertags have a similar function in CS:GO as other online games, we decided to prioritize participant integrity. Therefore, gamertags are not analysed as a tool for identity construction and the methodological implications of this decision are extensively discussed in a subsequent paper (Ståhl & Rusk, 2020).

Further, the participants were given as much control of the data as possible (Murphy & Dingwall, 2001). Apart from volunteering, the students handled the screen recording software and thereby decided which matches to send to the researchers. They were instructed to send both wins and losses and preferably varying maps, otherwise the decision on which match to send was theirs. The screen recordings were sent over an encrypted and secure file sharing service. Additionally, before showing any in-game material to an audience outside the research project, the specific material was sent to the participants and only material with their consent is shown, including this paper. The researchers had prior experience of this (Rusk, 2019; Sahlström,Tanner & Olin-Scheller, 2019; Ståhl & Kaihovirta, 2019). Comments on the research design, such as Excerpt 9 where the participants discuss whether they are allowed to swear, made it possible for the researchers to clarify their intentions during the interviews.

For most part, the excerpts have been translated into English by the researchers, except for statements originally in English. The interview excerpts have been translated with a focus on content and readability, and efforts were made to convey the same points stressed by the participants.

4 Results

The overarching aim of the study is to explore local player identity (co)construction in the multiplayer FPS CS:GO within an esports and educational context. The in-game screen recordings and the interviews were analyzed in parallel, however, in hindsight we see three major phases in our understanding of the phenomenon. Firstly, all participants’ in-game activity was observed trough the screen recordings and the interviews transcribed as they took place. Secondly, based upon the researchers’ initial observations, relevant in-game and interview situations were identified. Three categories of tools for identity (co)construction emerged: skins, choice of weapon and competence/rank. Thirdly, screen recordings and interviews were re-observed and relevant situations were identified. The categories needed clarification and all sequences of the collections were re-analyzed until the final categories emerged.

The research questions build on each other. The first research question focuses on what tools for in-game identity (co)construction the players employed. These tools included choice of weapon, weapon skill, weapon customization, stats/rank and language used. The second research question discuss how these tools were employed by the participants. The employment of the aforementioned tools were analyzed, and resulted in three categories of identity (co)construction: player customization, player competence and team discourse (see 4.1 - 4.3).

4.1 Identity and player customization

In-game, players decide what weapon to wield each round. The decision was locally and contextually situated, since it was in part based on in-game currency available, on the map, the side they are currently playing (terrorists or counter-terrorists) and partly on personal preference and customization. In CS:GO, weapon customization does not affect the effectiveness of the weapon, it only changes the appearance. There were three forms of weapon customization present in the data: weapon skins, stickers and renaming weapons. Skins affected the weapons' in-game visual representation (Figures 1-4) whereas stickers functioned as decals on a weapon (Figure 5). If renamed, the weapon would not appear with the standardized name, but perhaps as “Pistol of Doom” for all players.

While weapon customization such as weapon skins, stickers and renaming weapons have no direct impact on weapon effectiveness, some of the participants engaged with such customization. Weapon customization offers the player different ways to modify their in-game experience and thereby (co)construct identities. For example, while on the topic of skins in group interview 3 (2018), Martin said that skins can boost player confidence as some “get more confident if it’s looking better when they have nicer looking weapons.”

While he did not claim to be one of these players, Martin's actions in-game suggest that he does value weapons with skins. During match seven (2018, Figure 1) Martin noticed an AK-47 (equipped with the Redline skin and decorated with several FaZe clan stickers) lying on the ground next to an opponent. Martin swapped the AK-47 he was wielding (another opponent’s weapon with the Elite Build skin, see Figure 1) for the one lying on the ground (Figure 2). The weapons differed only in visual appearance and as the round was finished there was no need for him to swap weapons to get more ammunition, hence the choice to swap weapons was based on visual appearance. In match 2 (2017), however, the tables were turned and Martin got frustrated when an opponent did the same thing to him. Martin, wielding an AK-47 with a Frontside Misty skin, was killed and once the round ended, he exclaimed “Seriously! Of course he had to. He took one with a skin. He’s already got an AK….” Due to their customized nature, weapons with skins can be considered more meaningful for the owner, and as such, picking up an opponent’s weapon with a skin can be considered taking a trophy. Accordingly, skins appear to be meaningful for the participants even though they do not impact weapon effectiveness.

Figure 1. T1: match 7, Mirage. Screenshots: Martin’s point of view (POV). Click to enlarge.

Figure 2. T1: match 7, Mirage. Screenshots: Martin’s point of view (POV). Click to enlarge.

During interview 3 (T1, 2018) when asked if they preferred a specific type of skin and the researcher so far had provided them with the descriptions “colourful and elegant,” Joni claimed that “it should be more colourful” and Martin agreed. The participants might prefer to be associated with colourful rather than elegant skins as these were the descriptions provided so far. However, as visible in Figure 3, Joni’s stated preference for colourful skins appeared to match the skins he owned.

Figure 3. T1: match 2, Mirage. Screenshot: Martin spectating Joni. Click to enlarge.

Martin’s skins included military and technological designs (Figures 1 and 2) and some reflected his preference for colour (Figure 4). Martin did not, in comparison to John and Jesper (see below), appear to have a specific vision for his weapon customization. However, on several weapons (five in the data), he had the StatTrakTM function that tracks all the owner’s actions. These stats could be considered part of Martin’s identity as a competitive player for whom skins mainly functioned as confidence boosters. Jesper stated that he usually sold any skins he owned to buy games on Steam instead. He further claimed that he had very few skins since he “couldn’t be bothered to spend money on them” (interview 4, 2018), which is supported by the data. Apart from using one weapon skin, Urban DDPAT on an UMP-45, he only used weapons with skins when wielding someone else's weapon. Several weapons that Jesper used in the data (Glock 18, USP-S and M4A4) were decorated with various stickers. The weapon with most stickers, an AK47, was renamed “Instant eye cancer” (Figure 5) probably as a humorous comment on the visual expression as he tried to make the weapon “as ugly as possible.”

Figure 4. T1: match 7, Mirage. Screenshot: Martin’s POV. StatTrakTM MP9 - Bioleak. Click to enlarge.

Figure 5. T2: match 6, Overpass. Screenshot: Jesper’s POV. AK47 decorated with stickers and renamed. Click to enlarge.

Apart from being visual customizations, skins also had monetary value. John based skin purchases on value and whether he can resell them: ”I can have a knife for just an hour before it is gone” (T1, Interview 3, 2018). Martin identified John as the team member to spend the most on skins. John agreed and informed Martin that his most expensive skin was worth 1300 euros. Both teams appeared to be aware of skin value and what skins their team members owned.

Excerpt 1. EVC. T1: match 2, Mirage. Click to enlarge.

In the gameplay data, skins tended to be discussed in general terms, and specific skins were rarely mentioned. However, in Excerpt 1, John noted that Aster had a new skin which Aster confirmed. Martin remained focused on gameplay and noted the two present opponents. Their focus on visuals versus gameplay also became apparent during interview 4 (2018) when the researcher asked about time spent on their Steam profile. Although the researcher intended to ask about visual aspects of the profile, the vaguely asked question invoked different interpretations reflecting the player’s own interests. Martin replied: “On CS I have about 900 hours but that’s just one account. I also have my oldest one with about 2000 or 3000 hours of gameplay.” To him, visual customization appeared to be secondary in constructing his player identity and he mainly used customization to emphasize skill and effort. John on the other hand replied in terms of visual aspects: “I put a lot of effort into what the profile looks like since I was doing trading until they messed that up. So that it would look more like a store I guess” upon which Joni commented that John “had styled his [profile] more than the rest of us.”

The majority of player customization in the data aligned with individual and social aspects as motivation for buying in-game content, with few exceptions of economic rationale (Hamari et al, 2017). In contrast to Martin, for John, visual customization was highly relevant and connected to his player identity; a connoisseur of skins who knew their worth and was able to use that knowledge for trading. As previously discussed, Jesper seldom spent time and money on visual customization, yet when he did, it tended to focus on expressing his humour. While the different types of customization have no direct impact on weapon effectiveness, it does appear to have an impact on the participants' in-game experience. As discussed, player customization can take various forms; whether expressing taste, competence or sense of humour, and thereby (co)construct various player identities. However, identity (co)construction trough player customization further appears to be influenced by techno masculine ideals as skins with masculine connotations appear to be the norm. All weapon skins used in the data were either masculine or gender-neutral in terms of colour and pattern, with mainly military and technological influences. In fact, the only visual female representation in the data is a female pin-up sticker on the otherwise gender-neutral skin Point Disarray (see Figure 3).

4.2 Player identity and competence

In the following section, we discuss constructing what is perceived as a competent player identity based on three different tools: choice of weapon, weapon skill (see 4.2.1) and stats and rank (4.2.2). Do note that the focus here is on player effort to be perceived as competent and not necessarily to discuss the characteristics a competent player has.

4.2.1 Choice of weapon and weapon skill

Choice of weapon was one tool for player identity (co)construction and appears to be a highly conscious choice as the players repeatedly discussed benefits and drawbacks of specific weapons. Apart from buying weapons, it is also possible to pick up weapons dropped by co-players or (currently) dead players (Figure 1). The choice of buying weapon and gear was further influenced by player competence; their own, the co-players’ and that of their opponents, as well as their own preferences for specific weapons. Hence, choice of weapon and weapon skill appeared to be important tools for player identity (co)construction.

In CS:GO, all participants can simultaneously wield a main weapon, a pistol, a knife, two pieces of armour as well as different grenades. However, exactly what weapon to wield is based on certain factors, such as available in-game currency (dollars) and personal preferences. Here, choice of weapon was of great contextual and situated importance. During interview 4 (T2, 2018), Jesper discussed different options for the choice of pistol: CZ75 and Desert Eagle, and noted that both had their merits. Not only was he aware of the relative price of the CZ75 (500 dollars in relation to 2700 dollars for an AK-47), he also stressed its effectiveness at that specific time: “It’s a full auto pistol it’s kind of meta [1] right now, a little broken. They should fix it, it's sick good.” He thereby constructed an identity as an informed player with awareness of the latest patch. John, however, stated (interview 4, 2018) that “If things are going well with one I think that this is probably better than the others.” A specific pistol was not as essential a part of John’s player identity. His approach to the game appeared to not be as calculated as, for example, Jesper’s.

The choice of weapon includes different grenades. In match 7, Martin threw a smoke grenade followed by a HE grenade (usually referred to as a “nade”) and commented “oh my god what a good nade, oh my god what a good smoke” as they failed to hit the intended area, see circle in Figure 6. Although Martin failed in the execution of covering the entrance, the attempt to do so was a calculated choice as he explained in interview 4 (2018). Had he succeeded in placing the smoke it would have given his team the benefit of seeing the opponents when “They’d come out from ramp. If they are smart, then they won’t, and we have time to regroup. But if they do, we have the benefit of seeing them before they see us.” When he was asked whether he was being sarcastic or not; Martin replied: “I usually don’t say ‘good smoke’ [and mean it], so I guess it was sarcasm.”

Accordingly, Martin is competent enough to make an informed decision to place a smoke, however, he failed in the execution. To showcase that he is aware of his failure and, hence, maintain a competent player identity, he cracks a sarcastic joke about it. In general, humour, sarcasm and pranks are highly present in the data and appear to be an integral part of the participants' in-game experience.

Figure 6. T1: match 7, Mirage. Screenshot: Martin’s POV. Click to enlarge.

The most discussed weapon, the AWP, a sniper rifle available to both sides with, according to the Counter-Strike Wiki (n.d), “high risk and high reward.” In interview 4 (T2, 2018) Jesper stated that only one team member buys it and Martin argued a similar point (T1, interview 1, 2017): “If someone in the team is good with the AWP, then he’s the one to take it and we get a benefit from that.” Strategically, it is considered preferable to have one AWP on the team wielded by the player most proficient in using it. This role (the AWPer) was connected to the player's skill with a certain weapon; this functioned as a tool for constructing player identity as well.

Excerpt 2. T1: match 6, Mirage. Click to enlarge.

In Excerpt 2, Martin got shot wielding the AWP. As T1 were spectating William’s play, they negotiated who should be wielding the AWP and Martin was repeatedly stressing his current frustration as he considered himself competent wielding it. This claim is supported by John’s statement in interview 4 (T1, 2018): “the AWP is sort of a critical weapon … so you Martin usually get to have it.” As established by Voorhees & Orlando (2018) and noted by the participants as well, having the AWP is not simply a question of what weapon to wield, it is also an in-game role. Here, Martin's frustration was due to his situated weapon skill level not aligning with the role of the AWPer. He currently risks losing that role to Aster, since the role is connected to a specific weapon competence that Martin currently does not demonstrate. With in-game roles (and thereby team hierarchy) potentially being re-negotiated, it becomes clear that Martin considers the role of AWPer and the associated competence and status part of his player identity.

Both the in-game objective and the weapons available to the players vary depending on whether they are currently playing as T or CT. During the second interview with T2 (2017) Jesper concluded a discussion on the difficulty level of playing either side by stating: “I like being the first one to jump onto the bombsite and get the first kill. But I’m not bad at CT either.” By stating to prefer the supposedly more difficult option, he constructed a player identity that is competent and informed with awareness of strategic variations and his own preferences. In their final interview (2018) Jesper used the term “entry fragger,” the role he previously stated to prefer. As the only participant to use the correct terminology, he constructed a player identity that was competent and informed.

4.2.2 Stats and rank

Both player stats and rank functioned as tools for identity (co)construction. Each player is ranked based on performance in each match in competitive mode (including all matches here). There were 18 ranks in total and each was presented by a number, a title and an icon: the lowest rank, Silver I is number 1 and so on. Stats (match statistics) ar based on several variables, such as kills, assists and deaths.

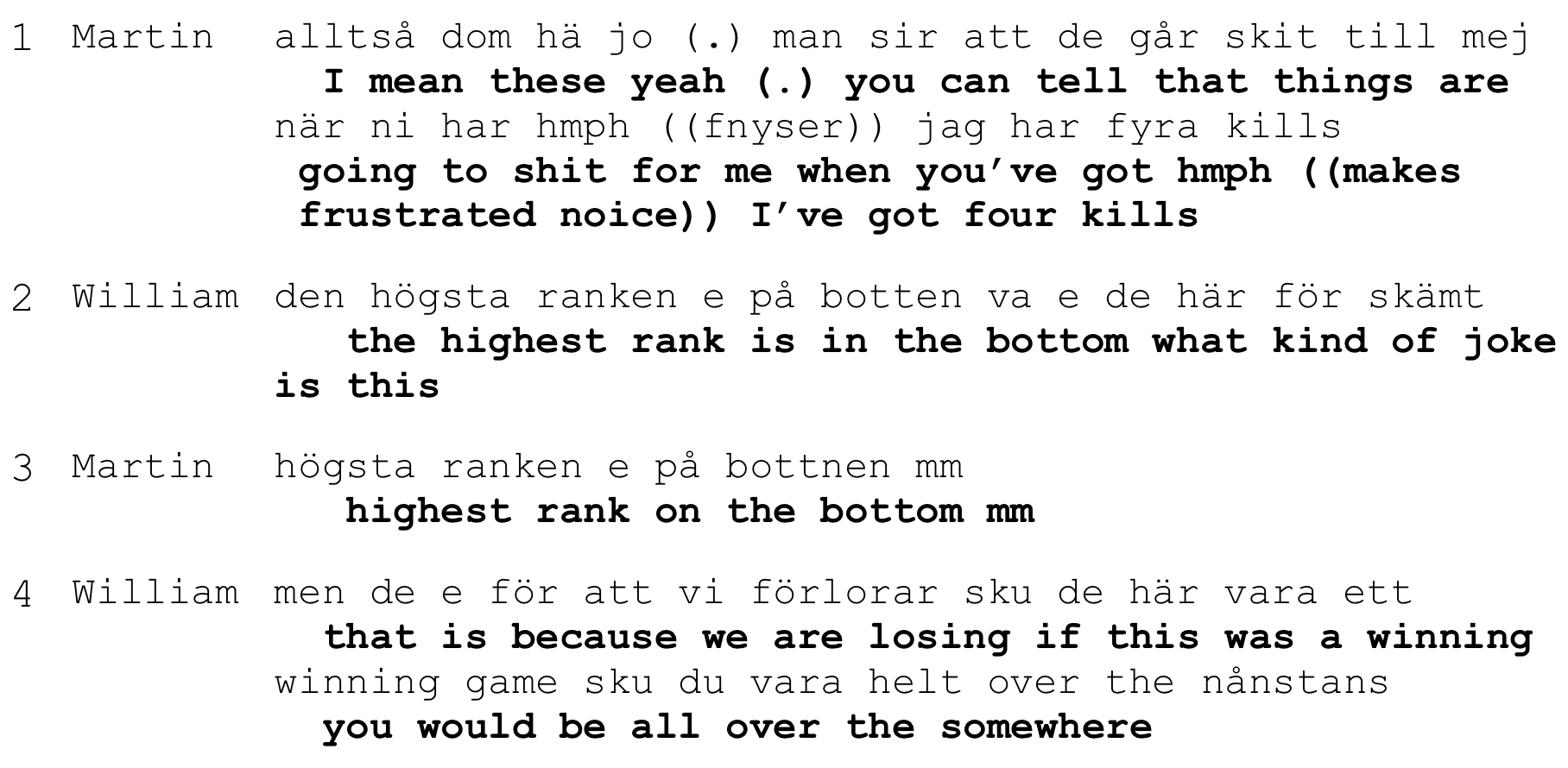

Player performance, defined by rank and stats, were made relevant by the players in-game and these indicators can therefore be considered part of player identity (co)construction. Not only did the players show awareness of their own ranking, but also team members’ ranks. During interview 3 (2018), when asked if they play CS:GO with people outside of T1, Martin’s response was “I play a fair amount with my other friends, my rank is kind of high, not to diss you guys,” upon which William replied “we will catch up with you, you have played longer than us.” In Excerpt 3, William noted that although Martin had the highest rank in T1, he was currently at the bottom of the table of stats in that match. Based upon rank, Martin was considered T1s best player, and therefore William found it peculiar that Martin had the worst performance in the match so far.

Excerpt 3. EVC. T1: match 2, Mirage. Click to enlarge.

The first three variables of stats; kills, assists and deaths, are presented in that specific order in CS:GO. The number of assists -- the number of times a player has assisted their co-players by damaging the opponent in question prior to them dying -- were seldom mentioned by the participants. Both teams appeared to, most often, discuss player performance solely based on the number of kills.

Excerpt 4. EVC. T2: match 6, Overpass. Click to enlarge.

In Excerpt 4, Jesper, Sebastian and Emil were playing with a teammate and a random player. In this situation, the others were spectating when the random player killed the remaining opponents and defused the bomb. Jesper was vocal in his admiration of the player's skills and stated that the player is hardcore (line 8). They noted (lines 4 and 8) that ‘he’ (assumed by the participants to be identifying as male due to his low voice) had 19 and later 20 kills and only 5 deaths. Sebastian (line 4) did not specify which variables he was referring to as stats and neither Emil nor Jesper asked him to clarify. Here, there appeared to be a collective understanding that kills and deaths were the relevant stats. As the random player's competence was discussed mainly through these stats, they can be considered part of the competent player identity (co)constructed with the participants.

Martin had the highest rank on T1, and it supposedly provided him some authority within the team. During interview 3 (2017), Martin agreed to being the team leader and stressed that he coached John so that he could become part of T1. In the final interview (T1, 2018), as the other team members were asked about Martin as leader, Joni claimed that “sometimes when things are going well, he says that “you did good.” Martin once more brought up his efforts to get John into the team: “Back then you (John) were kind of, and when you got to silver I got a new account to get you out of there.” When asked about the type of support Martin had provided, John replied “It was more like, here is a semi high ranked account, go ahead and play... You learn how to swim if you are thrown into the water.” The authority provided by having the highest rank and often having the highest number of kills per match (Excerpt 3 being the exception), Martin constructed a competent player identity. By allowing him to take on the role as team leader, Martin's competent player identity was co-constructed within the team and Martin considered coaching John part of that role, resulting in a mentor-apprentice relationship between them (Rusk, Ståhl & Silseth, 2020). Hence, (co)constructing a player identity is connected to instrumental tools such as rank and stats, and it is also formed by the context.

4.3 Player identity and team discourse

Language use in general, and offensive language in particular, was a form of identity (co)construction present in the data. Language used varied in terms of content and language; Swedish, Finnish, English and Russian. Offensive language is used in all communication channels. CS:GO does not censor certain words in the TBC.

In this section, the focus is on the team discourse and language use; especially the use of offensive language as part of (co)constructing player identities. Most participants had at some point in the data used offensive language in-game but using offensive language was not exclusive to the participants. Random co-players and opponents also tended to use offensive language. It appeared to be fairly common in the data and a part of how participants orient towards various in-game events, co-players and opponents. The discussion that T2 had during their first recorded match indicates that using offensive language was conscious and part of the game experience. They discussed if they were allowed to swear while recording for research (Excerpt 5). They concluded with the answer that they were allowed to swear but intended to keep it to a minimum. Underlying this negotiation was an understanding that using offensive language was part of their game experience and can therefore be considered a tool for their player identity (co)construction.

Excerpt 5. EVC. T2: match 1, Mirage. Click to enlarge.

Offensive language was primarily used when talking about co-players and opponents that the participants found provocative, based on various behaviours; playing in what the participants perceived as a cowardly fashion or using strategies perceived as signs of incompetence. For example, using the P90 weapon was perceived as cowardly and incompetent. When asked (interview 4, T1, 2018) about what weapons they preferred not to use, the discussion focused on Martin’s distaste for certain weapons. Martin disliked “if you can shoot multiple bullets on the same time instead of shooting one bullet and miss” whereupon the discussion turned to the P90 that Martin, according to John, “had some issues with.” Martin referred to these low-risk weapons as “noob weapons,” indicating that these require limited weapon skill. His distaste for the P90, and the players using it, was clear as he (match 7, Mirage), in-game, when killed by an opponent wielding a P90 stated “He has a fucking P90. What am I going to do? P90 is so gay ass.” Martin had repeatedly referred to players wielding the P90 as having low weapon skill and here he referred to the weapon itself as “gay ass.”

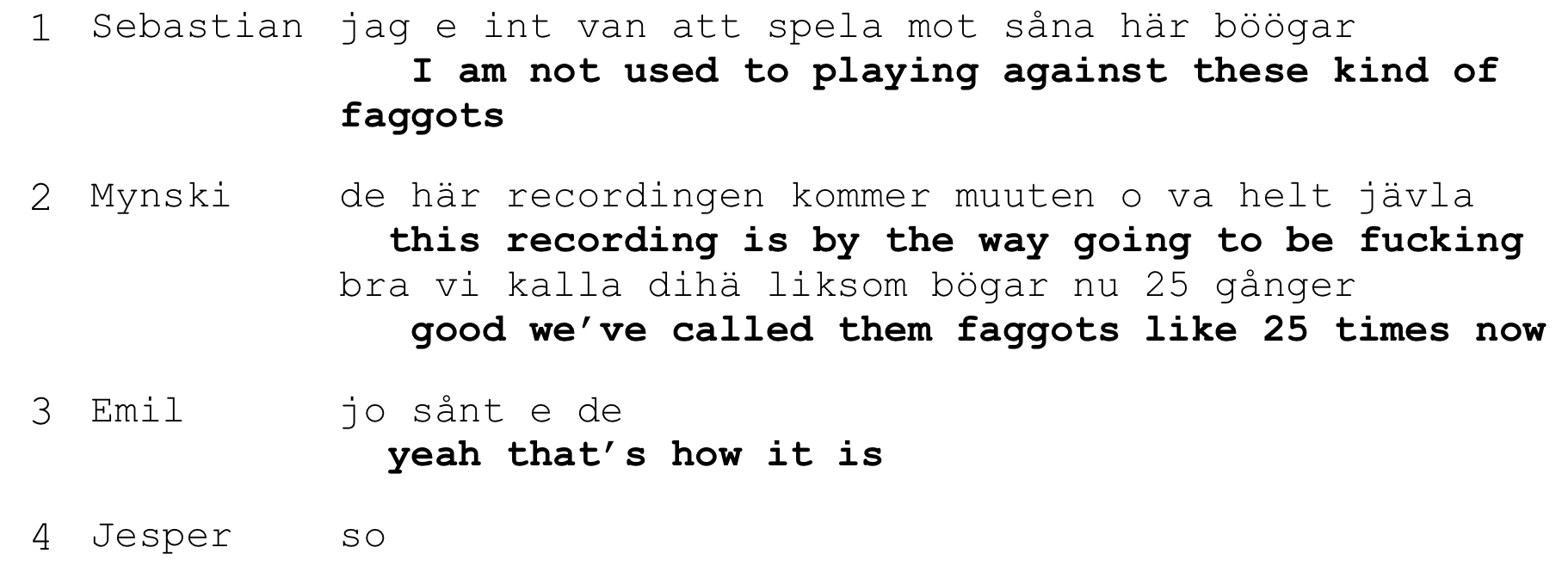

In their 6th match, T2 played against a team they considered to be playing in a cowardly fashion as the opponents’ tendency to hide slowed down the pace of the game. The context and the duration of hiding in the smoke determined if the move was considered a cowardly or smart one. The players expressed their frustration in various ways; Jesper commented that “they are kind of chicken; they don’t dare to do anything” (T2, match 6) whereas Sebastian described them as both “losers” and “faggots” when camping in the smoke.

Excerpt 6. EVC. T2: match 6, Overpass. Click to enlarge.

In the data, the use of offensive language is seldom commented upon. However, later, in the same match, Sebastian uses “bög” (Swedish equivalent to faggot) to describe the opponents and Mynski noted that they had been using that terminology quite frequently that match (see Excerpt 6). Neither Emil nor Jesper participated in the use mentioned by Mynski, but Emil agreed that that was the case. Jesper replied with a “so?” presumably in relation to the fact that they were using offensive language in a recorded match. As previously mentioned, Jesper and Emil were part of negotiating to what extent it was suitable to swear in recorded matches (Excerpt 5). Excerpt 6 strengthens the understanding that using offensive language was part of the in-game experience and a tool for identity (co)construction.

There were situations in the data where opponents and co-players were referred to as homosexual men as an insult, sometimes to their knowledge, in at least three different languages. Martin used the word “pidaras” (Russian derogatory word for homosexual man) to supposedly insult a Russian player through the TBC. He had presumably learned this word through playing CS:GO as he did not otherwise speak Russian. It is worth mentioning that all examples, with the exception of “pidaras,” mentioned thus far in relation to in-game offensive language are from the team only chat (EVC). Hence, the offensive language has not reached anyone outside the team, and the opponents mentioned above (T2, match 6) have not heard these conversations. Most communication was done in the EVC, and to a smaller degree on the IVC and the TBC.

Although not as common as referring to provoking players as homosexual men, there were also examples of offensive language with female connotations in the data. For example, non-participants insulted each other with “cyka” (Russian for “bitch,” T1, match 2, Mirage). The word “vittu” also occurs in various forms (Excerpt 4) as it is in usage the Finnish equivalent to “fuck,” although the literal translation refers to female genitalia. Accordingly, it appears that part of constructing a player identity can be stressing a perceived incompetence of other players, especially in terms of low weapon skill, and describe them using derogatory words for women or homosexual men. It is however important to note that some of the players did not participate in this practice. Further, offensive language was recurrently used in the opposite fashion as well. For example, using “vittu” (Finnish for female genitalia) in order to give effect when describing high player competence in Excerpt 4. Hence, the offensive language is here used in order to emphasize negative as well as positive statements.

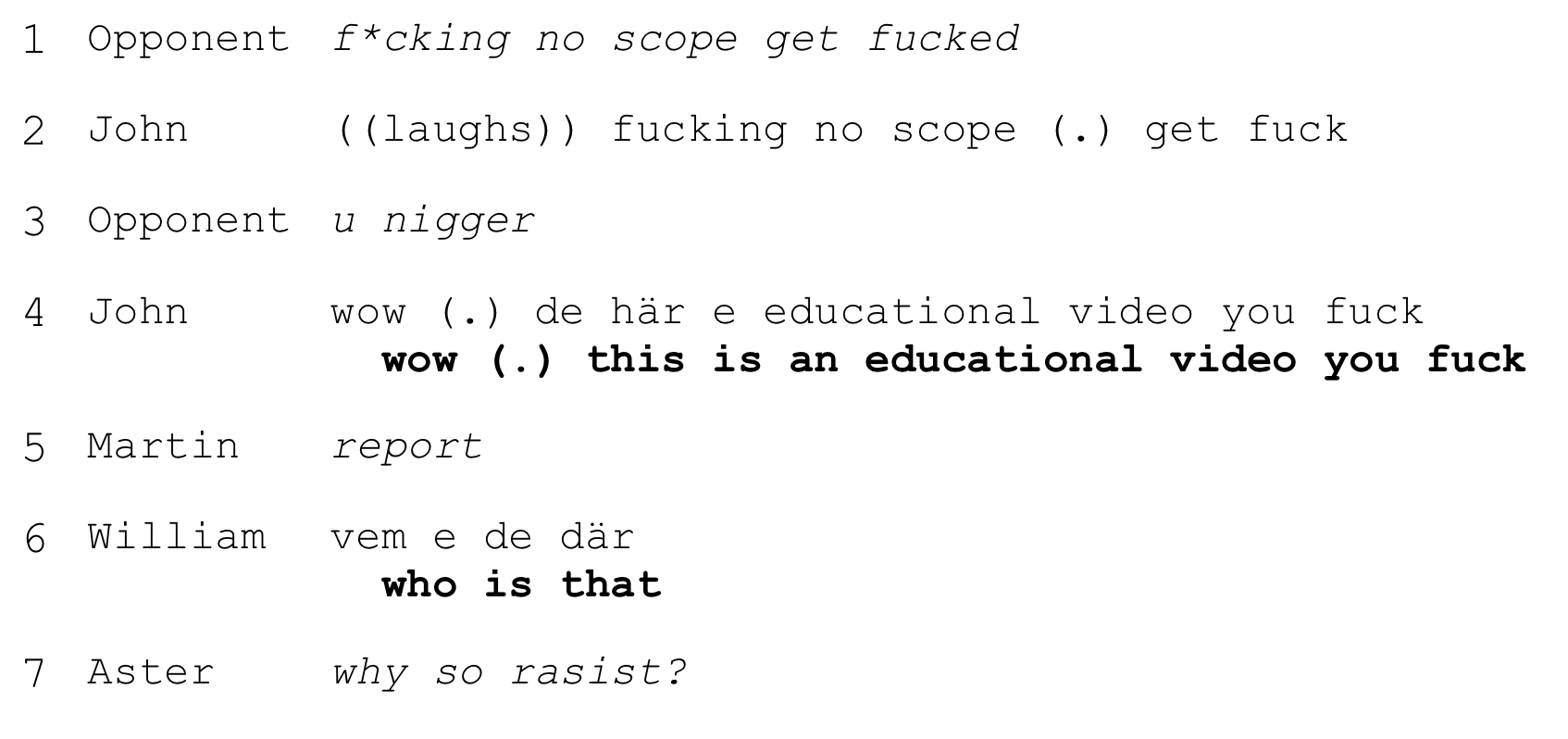

Excerpt 7. EVC/TBC. T1: match 4, Cache. Click to enlarge.

In Excerpt 7, John was reading out loud what the opponent was writing in the all chat version of the TBC, yet he stopped mid word as he noticed what the player had written. There was a short silence and then the players reacted in various ways. John and William (lines 4 and 6) stated their shock through the EVC, whereas Martin and Aster (lines 5 and 7) directed their response directly at the random player through the TBC. Although the responses varied, there appeared to be a common understanding that the opponent had crossed the line of what is appropriate to say or write in-game. More than a minute later, at the end of the round, the opponent in question types in the TBC “sry I was hyped.” The participants read this out loud several times, laughed and Martin said “hyped enough to write nigger” and scoffs. Their reactions suggest that they do not perceive being hyped as a valid excuse for such language. Whether the opponent is genuinely sorry for their actions or if they simply wish to avoid being reported (and potentially banned from playing), they still take the time to address the situation afterwards. This indicates that the opponent also orients to the language use as inappropriate, on some level.

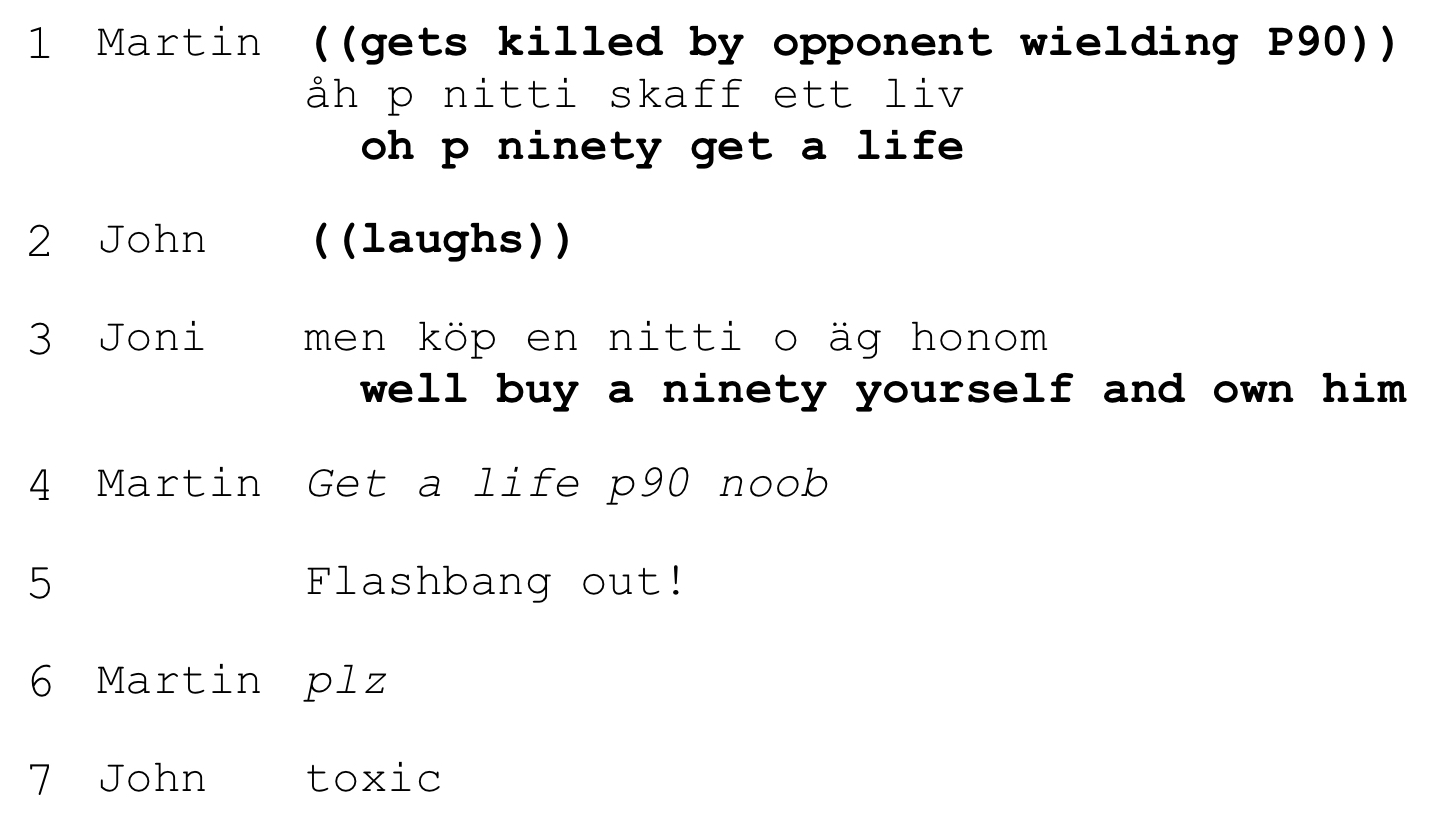

Excerpt 8. EVC/TBC. T1: match 7, Mirage. Click to enlarge.

Although offensive language can be considered part of the game experience, there were subtle comments to the team jargon as well, see John’s comment on team toxicity in Excerpt 8. All players were assumed to be male and referred to as “he” or “him.” See for example Excerpt 8 (line 3) where the player is assumed to be male, although the participants have not heard the opponent's voice and neither gamer tag nor player icon had any gender connotations. In match 3, T1 was uncertain whether their co-player was male or female based upon their voice and was referred to as both him and her (apart from this instance, any “she” or “her” referred to was usually one of the researchers, see Excerpt 5). This instance was later discussed during interview 3 (T1, 2017) and followed by a discussion regarding female players in general. Martin mentioned the negative attitude against players clearly stating to be female, for example by gamertags such as “grl gamer” as “they usually get a lot of crap.” He remembered an instance where a co-player commented that the match was as good as lost as they had a female player on the team: “Someone immediately wrote ‘gg there is a girl in our team’.” He further said that: “I don’t give a damn if you’re a girl. If you are good at the game, there should be nothing stopping you. That [female players are not as good as male] is just a stereotype.” Despite the general attitude towards female players, Martin stated that in his opinion, gender should not matter in CS:GO.

As previously discussed, constructing a competent player identity included orienting towards in-game events, co-players and opponents and how these players were addressed is a co-construction within the team. Offensive language was often used to describe provocative players and in-game events. However, in the data, such language use was also employed to emphasize positive traits. The team discourse dictated to what level offensive language was suitable and this discourse was actively negotiated as individual players commented on the language used by themselves (except 6) or their teammates (Excerpt 8).

5 Discussion

The aim of the study was to explore local player identity (co)construction in CS:GO within an esports and educational context. The categories of tools made relevant by the participants were choice of weapon, weapon skill, weapon customization, stats/rank and language use. With limited previous research on identity construction within FPSs (Kiourti, 2018; Rambusch et al, 2007 and Orlando & Voorhees, 2018, among the few exceptions), the descriptive tools discussed in this paper can be used as starting point for future research on the topic. Additionally, as previously discussed, the participants used these tools for (co)constructing identities in relation to player customization, competence and team discourse.

The research design relied upon the involvement of the participants and their willingness to document their gameplay. It resulted in data within a naturally occurring setting (Hammersley, 2018) and multiple insider perspectives of the same situation proved invaluable to the analysis. The screen recordings did in fact not only capture what happened in-game, but also the team internal interaction through the EVC and the identity (co)construction that happened on both platforms, often in parallel. Through video-stimulated recall during the interviews (Nguyen et al, 2013) discussion on certain gameplay sequences provided further insiders' comments on the events. As identity affects and is affected by a social context and need to be analyzed as such (Banjeree & German, 2014), these discussions informed the analysis of a participant’s perspective on player identity (co)construction. Here, player identity (co)construction was primarily analysed within the situated social context, and not all social contexts (and thereby identities) the participants engaged with. Next, we will discuss these findings in relation to three broader contextual factors that appeared central in shaping the situated identity (co)construction: the game context, the norms of online game culture and the educational context.

Although customization is limited within CS:GO, especially in comparison to games such as MMORPGS (e.g. Corneliussen, 2008), the participants used the tools within the game context for constructing various player identities. Rank was oriented to as an indicator for player competence and the in-game status that was associated with a high player rank created mentor-apprentice relationships (Rusk, Ståhl & Silseth, 2020). Such arrangements have been part of the game culture since the first version of CS (Wright et al, 2002) and while not explicitly arranged by the esports programme, the focus on teamwork does encourage peer support (Ögland, 2017). Likewise, match statistics were perceived as an instrument for situated player performance. In particular, the number of kills, defined how well a player was performing. In the educational context, further emphasis could be made on the relevance on all players' efforts and teamwork as assists appeared be of little value for the participants. These instrumental ranking systems, part of the game design, were continuously oriented to as relevant by the participants and gave a certain status to those rated as high performing by these systems. Thereby, these in-game features became tools for (co)constructing competent (or incompetent) player identities reaching beyond the in-game context.

While the game context, with possibilities and limitations, shape the in-game experience, so does the online game culture and the norms associated with it. As previously discussed, technomasculinity shapes not only player culture (N. Taylor & Voorhees, 2018; Sveningsson, 2012; Witkowski, 2018) but also the game industry (Johnson, 2018). The ideal esports player appears to be male, white, heterosexual and competitive (Witkowski, 2013), traits that align with the ideals visible in technomasculinity. While this norm does not reflect actual player demography (Kowert et al , 2014), it does limit which players feel included in a culture highly shaped by competitiveness. Prominent players tend to take their play more seriously (Rambusch et al, 2007) and, in this study, especially weapon skill was connected to player competence. The two in-game roles that appeared to be particularly desirable were the AWPer and the entry fragger, although neither team stated to have allocated these roles. Although the roles differ in terms of game play, both reflect technomasculine ideals (Voorhees & Orlando, 2018), whether that is playing in a highly aggressive or strategic manner. In order to obtain either role, certain weapon skill is required. Taking on either of these roles is associated with a high status, both in-game and out, and were thereby part of constructing competent and competitive player identities.

The all-male group of participants was not a choice made by the researchers, but supposedly a result of the predominantly male online game culture resulting in few female students in the esports programme. In the data, participants presumed all players to be male unless a gamer tag or their voice hinted that the participants needed to re-evaluate such an assumption. While the participants stated to welcome female players, they did note that the online game culture in CS:GO might not be supporting of female identifying players; echoing the works of for example Witkowski (2018). In terms of visuality, all characters in CS:GO are male and skins with masculine connotations appear to be the norm. Therefore, using gender-neutral skins can be seen as taking a stance against the norm of technomasculinity within online game culture. In fact, the only visual representation of femininity in the game is visible in Figure 3, where a weapon is decorated with a pin-up sticker. This sticker can be seen as a visualisation of how women are perceived to have a mere decorative value in the online game culture.

We noted offensive language as part of the (co)constructed player identities impacting the team discourse, a finding supported by previous research (Kiuorti, 2018). Using multilingual slurs against women and homosexual men was a practice shared by participants as well as random co-players and opponents, supporting that such “gamer lingo” currently function as a norm within online game culture (Pulos, 2013). However, we also noted individual tendencies to use, and not use, certain words. Thereby, while offensive language can be considered “a game within the game” (Vossen, 2018), not all participants took part in such a practice. Some players even took a stance against this norm by pointing out toxicity within the team. While there was a prominent tendency to use words with either queer or female connotations in order to describe the players one considered provoking, and despite racism being an issue in online gaming (Nakamura, 2009; Gray, 2018), here racial slurs were few. In fact, when an opponent uttered a racial slur, the participants were quick to react by pointing out the language as racist.

While the participants appeared to agree that being agitated in-game does not condone racism, they were not as critical towards language use potentially reflecting misogyny and/or homophobia. Employing games as CS:GO in an educational context may be challenging, since such values are in stark contrast to educational values such as democracy and inclusion. However, excluding commercial games from an educational setting is to refrain from improving skills such as communication and collaboration in a social learning platform that students find authentic and motivating (Gee, 2007; Barr, 2018). Further, what would be a better place to address these issues with the in-game culture than in education and an esports programme? The educators have made efforts in this regard, but changing norms is a slow process.

In conclusion, while we noted multiple tools for identity (co)construction, the employment of these tools is limited. It is worth mentioning our own, possible, bias as researchers on a gamer context. While neither researcher is actively playing CS:GO, however, both identify as gamers and have previous experience of the norms in online gaming contexts. However, by researching the norms that currently shape online game culture, we indirectly question them and challenge heteronormativity’s and technomasculinity’s grasp on online game culture. While a FPS such as CS:GO has less options for player customizations than other genres, that is not the main constraining factor. In fact, player identity construction is to a higher degree limited by the online game culture shaped by esports and competitiveness. It appears that, since the norm dictates that the ideal esports player is male, white, heterosexual and competitive, player identity (co)construction needs to reflect these values in order not to break the norm. Constructing identities outside of this ideal is currently met with resistance and access to online game culture remains limited for those that do not fit these criteria. While competitiveness is to a certain degree to be expected in an esports setting, we argue that all esports organisations have a responsibility to support and encourage sportsmanship. This study supports the need for further non-normative research on online game culture, especially in relation to representation, education and esports.

Acknowledgements

Initially, we wish to thank the participants that willingly shared highly personal data with us so that we as researchers better could understand what online gaming was to them! We wish to thank the Swedish Cultural Foundation in Finland, Viktoriastiftelsen, Stiftelsen för Åbo Akademi and Högskolestiftelsen i Österbotten for research funding and travel expenses on behalf of Ståhl during the process of this paper. We also wish to thank Inga, Valdemar, Anna-Lisa och Inga-Brita Westbergsfond for covering travel expenses during the data collection phase. We further wish to thank the anonymous reviewers as their response was highly helpful in the revision of this paper!

Endnotes

[1] Meta is according to Urban Dictionary a term used in online gaming “meaning the Most Effective Tactic Available. It's basically what works in a game regardless of what you wish would work.”

References

Beaulieu, A. (2004) Mediating ethnography: objectivity and the making of ethnographies of the internet. Social Epistemology, 18(2-3), 139-163, DOI: 10.1080/0269172042000249264

Banjeree, P., & German, M. (2014). Religious-Ethnic Identities in Multicultural Societies: Identity in the Global Age. In Y. Kalyango & M. W. Kopytowska (Eds.), Why Discourse Matters: Negotiating Identity in the Mediatized world (pp. 256-286). New York: Peter Lang Publishing

Barr, M. (2018). Student attitudes to games-based skills development: Learning from video games in higher education. Computers in Human Behavior, 80(2018), 283-294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.11.030

Boellstorff, T., Nardi, B., Pearce, C., & Taylor, T. L. (2012). Ethnography and virtual worlds: A handbook of method. Princeton University Press.

Chilton, P. (2014) Preface. In Y. Kalyango & M. W. Kopytowska (Eds.), Why Discourse Matters: Negotiating Identity in the Mediatized world. New York: Peter Lang Publishing

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2005). Research Methods in Education (Fifth Edition). London and New York: Routledge/Falmer.

Corneliussen, H.G. (2008). World of Warcraft as a playground for feminism. In H.G. Corneliussen & J. Walker Rettberg. (Eds.). (2008). Digital culture, play, and identity. A World of Warcraft® Reader (pp. 63-86). Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Counter-Strike Wiki. (n.d.). AWP. Retrieved 13.8.2019 from https://counterstrike.fandom.com/wiki/AWP

Ecenbarger, C. (2014). The Impact of Video Games on Identity Construction. Pennsylvania Communication Annual, 70(3), 34-50.

Fine, G. A. (1983). Shared Fantasy. Role-Playing Games as Social Worlds. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Gee, J. P. (2007) What Video Games have to Teach us about Learning and Literacy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gray, K. L. (2018) Gaming out online: Black lesbian identity development and community building in Xbox Live. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 22(3), 282-296, DOI: 10.1080/10894160.2018.1384293

Hall, S. du Gay, P. (1996). Questions of Cultural Identity. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Hamari, J., Alha, K., Järvelä, S., Kivikangas, M., Koivisto, J., & Paavilainen, J. (2017) Who do players buy in-game content? An empirical study on concrete purchase motivations. Computers in Human Behaviour, 68, 538-546. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.045

Hammersley, M. (2018). What is ethnography? Can it survive? Should it? Ethnography and Education, 13(1), 1-17, DOI: 10.1080/17457823.2017.1298458

Harvey, A. (2015). Gender, Age, and Digital Games in the Domestic Context. New York: Routledge.

Johnson, R. (2018). Technomasculinity and its influence in video game production. In N. Taylor & G, Voorhees (Eds.) (2018) Masculinities at play (pp. 249-262). Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland.

Kinnunen, J. Lilja, P. Mäyrä, K. (2018). Pelaajabarometri 2018. Monimuotoistuva mobiilipelaaminen. TRIM research reports, 28.

Kinnunen, J. Taskinen, K. Mäyrä, K. (2020). Pelaajabarometri 2020. Pelaamista koronan aikaan. TRIM research reports, 29.

Kiuorti, E. (2019). “Shut the Fuck up Re! 1 Plant the Bomb Fast!” Reconstructing Language and Identity in First-person Shooter Games. In A. Ensslin and I. Balteiro (Eds.). Approaches to Videogame Discourse: Lexis, Interaction, Textuality (pp.157-177). New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Kopytowska, M. W. Kalyango Jr, Y. (2014). Introduction: Discourse, Identity, and the Public Sphere. In Y. Kalyango & M. W. Kopytowska (Eds.), Why Discourse Matters: Negotiating Identity in the Mediatized world (pp. 1-16). New York: Peter Lang Publishing

Kowert, R. Festl, R. Quandt, T. (2014). Unpopular, Overweight, and Socially Inept: Reconsidering the Stereotype of Online Gamers. Cyberpsychology, behavior and social networking, 17(3). DOI: 10.1089/cyber.2013.0118

Meyrowitz, J. (1986). No sense of place. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Mukherjee, S. (2012). Egoshooting in Chernobyl: Identity and subject(s) in the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. games. In J. Fromme & A. Unger. (Eds.) Computer games and new media cultures: A handbook of digital games studies (pp. 219-231). Dordrecht, Germany: Springer.

Murphy, E., & Dingwall, R. (2001). The ethics of ethnography. In P. Atkinson, A. Coffey, S. Delamont, J. Lofland & L. Lofland. (2001). Handbook of ethnography (pp. 339-351).

Nakamura, L. (2009) Don't Hate the Player, Hate the Game: The Racialization of Labor in World of Warcraft. Critical Studies in Media Communication. 26(2), 128-144, DOI: 10.1080/15295030902860252

Nguyen, N. T., McFadden, A., Tangen, & D. Beutel, D. (2013). Video-stimulated recall interviews in qualitative research. Proceedings of the Australian Association for Research in Education Annual Conference (pp. 1-10). Adelaide, South Australia.

Parker-Jenkins, M. (2018). Problematising ethnography and case study: reflections on using ethnographic techniques and researcher positioning. Ethnography and Education, 13(1), 18-33, DOI: 10.1080/17457823.2016.1253028

Pink, S. (2013). Doing visual ethnography. Sage.

Pink, S., Horst, H., Postill, J., Hjorth, L. & Tacchi, J. (2016). Digital ethnography. Principles and practice. Los Angeles: Sage.

Pulos, A. (2013). Confronting Heteronormativity in Online Games: A Critical Discourse Analysis of LGBTQ Sexuality in World of Warcraft. Games and Culture, 8(2), 77-97. DOI: 10.1177/1555412013478688

Rambusch, J., Jakobsson, P., & Pargman, D. (2007). Exploring E-sports: A case study of gameplay in Counter-strike. Situated Play. Proceedings of the 3rdDigital Games Research Association International Conference (pp.157-164). Tokyo, Japan.

Ratan, R. A., Taylor, N., Hogan, J., Kennedy, T., & Williams, D. (2015). Stand by Your Man: An Examination of Gender Disparity in League of Legends. Games and Culture, 10(5) 438-462. DOI: 10.1177/1555412014567228

Rusk, F., Ståhl, M., & Silseth, K. (2020). Exploring peer mentoring and learning among experts and novices in online in-game interactions. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Game Based Learning, ed. P. Fotaris, 461-468. Academic Conferences International Limited.

Rusk, F. (2019). Digitally mediated interaction as a resource for co-constructing multilingual identities in classrooms. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 21, 179-193

Sahlström, F., Tanner, M., & Olin-Scheller, C. (2019). Smartphones in Classrooms: Reading, Writing and Talking in Rapidly Changing Educational Spaces. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2019.100319

Scwandt, T. A., & Gates, E. F. Case Study methodology. In N. K. Denzin, N. K. & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds). (2018). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (pp. 341-358). (Fifth edition.). Los Angeles: SAGE.

Shulman, D. (2017). The Presentation of Self in Contemporary Social Life. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Shumar, W., & Madison, N. (2013). Ethnography in a virtual world, Ethnography and Education, 8(2), 255-272, DOI: 10.1080/17457823.2013.792513

Sierra Entertainment & Valve Corporation. (1998). Half-Life [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game published by Valve Corporation.

Ståhl, M., & Kaihovirta, H. (2019). Exploring visual communication and competencies through interaction with images in social media. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 21, 250-266.

Ståhl, M., & Rusk, F. (2020). Maintaining participant integrity - ethics and fieldwork in online video games. Manuscript under review.

Sundén, J. A queer eye on transgressive play. In J. Sundén & M, Sveningsson (ed.) (2012). Gender and Sexuality in Online Game Cultures (pp. 171-190). New York: Routledge.

Sveningsson, M. (2012). ‘Pity there’s so few girls!’ Attitudes to female participation in a swedish gaming context. In J. Fromme & A. Unger (Eds.) Computer games and new media cultures: A handbook of digital games studies (pp. 425-441). Dordrecht, Germany: Springer.

Taylor, N. (2016). Play to the camera: Video ethnography, spectatorship, and e-sports. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 22(2) 115-130

Taylor, N. (2011). Play globally, act locally: The standardization of pro Halo 3 gaming. International Journal of Gender, Science and Technology, 3(1).

Taylor, N., Voorhees, G. (2018). Introduction: Masculinity and gaming: Mediated Masculinities at play. In N. Taylor & G, Voorhees (Eds.) (2018) Masculinities at play (pp. 1-19). Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland.

Taylor, T. L. (2009). Play Between Worlds. Exploring Online Game Culture. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Turkle, S. (1995). Life on the screen. Identity in the age of the internet. New York: Touchston.

Witkowski, E. (2013) Eventful Masculinities. Negotiations of Hegemonic Sporting Masculinities at LANs. In M. Consalvo, K. Mitgutsch & A. Stein (Eds.) Sports Videogames (pp.217-235). New York and London: Routledge.

Witkowski, E. (2018). Doing/Undoing Gender with the Girl Gamer in High-Performance Play. In K. L. Gray, G. Voorhees., & E. Vossen. (Eds.) Feminism in Play (pp. 185-203). Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland.

Wright, T., Boria, E., & Breidenbach, P. (2002). Creative player actions in FPS online video games: Playing Counter-Strike. Game studies, 2(2), 103-123.

Valve Corporation. (2000). Counter-Strike [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game published by Valve Corporation.

Valve Corporation & Hidden Path Entertainment. (2012). Counter-Strike: Global Offensive [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game published by Valve Corporation.

Voorhees, G., & Orlando, A. (2018). Performing Neoliberal Masculinity: Reconfiguring Hegemonic Masculinity in Professional Gaming. In N. Taylor & G, Voorhees (Eds.) (2018) Masculinities at play (p.211-227). Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland.

Vossen, E. (2018). The Magic Circle and Consent in Gaming Practices. In K. L. Gray, G. Voorhees., & E. Vossen. (Eds.) Feminism in Play (pp. 205-220). Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland.

Ögland, K. (2017). Esports. The educators handbook. Yrkesinstitutet Prakticum.