Separation Anxiety: Plotting and Visualising the Tensions Between Poetry and Videogames

by Jon StoneAbstract

‘Poetry games’ are a hybrid form characterized as intrinsically paradoxical by Astrid Ensslin in her 2014 book Literary Gaming. Digital poet Jim Andrews likewise asserts that poetry and videogames go together like “oil and water.” In this article, I argue that by examining in more detail the phenomenological tensions between the two, we can better understand the ways in which poem-game hybrids are able to negotiate this apparent incompatibility. I propose three continuums that enable us to visualize those tensions that exist, consider what limitations are suggested by them, and discuss how the developers of what Ensslin terms ‘poetry games’ are able to work within these limitations.

Keywords: poetry, poem-game hybrids, literature, poetry games, deep attention, hyper attention, cybertext, gameplay

Introduction

Gregory Weir’s Silent Conversation makes for an intriguing case study in poem-videogame hybridity. Originally browser-based and now free to download through the itch.io website, its levels are made entirely of poems and short stories; that is, the text itself is used as the solid ground that the player traverses, with an i-beam pointer serving as player avatar. Poems by William Carlos Williams and Bashō are among those that feature. To complete a stage, the player’s i-beam must move atop and around the text, while avoiding the crimson emanations of certain ‘powerful words,’ which reset their progress when touched. In theory, this system accentuates the physical dimension of poetry in a way that augments the experience of those consuming it. It answers the demand made by Los Pequeño Glazier in his Digital Poetics: The Making of E-Poetries for an electronic poetry that “extends the physicality of reading” (2002, p.37) through cybernetic integration of the reader. In practice, however, the poems used in Silent Conversation are more difficult to read and understand in the context of the game than they are when set out on a static page. The ability to focus on the content of the text is impeded by the platformer physics, since the i-beam cannot pass across individual lines as the eye does, but must go around and over the top. The expectation imposed by the game’s scoring system, whereby the player must touch as many words as possible to earn a higher grade, overwrites the diverse semantic properties of each component of the text with a more pressing ludic function; they are words only secondarily, being primarily items for collection. The world of the game is separate, functionally and representationally, from the world of whatever poem or piece of writing is being employed as its building bricks.

This example serves to highlight a conflict between the poetic and the ludic that remains relatively unexamined. Despite poets such as Apollinaire and Raymond Queneau being recognized as early practitioners of ergodic literature, it is the relationship between stories and games that has occupied scholars over the last two decades, with poetry only receiving secondary consideration. But poem-game hybrids -- as represented by some of Silent Conversation’s levels, as well as by the poetic-ludic vignettes produced using Adam LeDoux’s Bitsy and various poetry text adventures written in Twine -- are beginning to take up full-time residence in the videogaming landscape. It is necessary, therefore, to contend with the particular ways in which poetry and videogames do and do not mix if we are to understand how these hybrids can succeed and fail.

My starting point in this exercise is Astrid Ensslin’s Literary Gaming, the first major text to designate and define a category called ‘poetry games.’ Poetry games, according to Ensslin, are videogames which replace one or more traditional features of games with poetic language -- language that draws attention to its own structure and aesthetics. In the case of Silent Conversation, what is replaced is the ‘solid’ component of the game’s levels. Where the entire interface is text-based (as in most Twine games), Ensslin would categorize the artefact as ludic hypertext literature or hypermedia, rather than as a videogame, but where the underlying structure is audiovisual rather than verbal (as in games made in Bitsy), the presence of poetry produces an incompatibility, in Ensslin’s analysis.

Two examples I would like to keep in mind for the duration of this paper are ‘her body unswept by laughter’ by nurbrun -- a Twine game which is also a poem, in which the player proceeds by examining the parts of a rose -- and Cecile Richard’s Novena, also advanced as a poem, in which the player controls an avatar, encountering successive, iterated stanzas of poetry as they move through the game. Both are simple artefacts by the standard of most videogames, but useful as templates for how we might imagine more advanced poetry games to work. Referring to these, then, but working mostly from theory, I will examine whether it is necessarily the case that there is a clash in the combination of videogame and poem.

Oil and Water

Digital poet Jim Andrews has documented his own struggles with poem-game hybridity, which lead him to conclude that “the relationship between poetry and videogames is mostly of the oil and water variety” (Andrews, 2007, p.6). Andrews’ poetry game, Arteroids, is described on its website as “a literary shoot-em-up computer game -- the battle of poetry against itself and the forces of dullness” (Andrews, 2015), and of his experiences developing it he writes:

Poetry is not a game somebody wins. Just as art is not a game somebody wins. It wasn’t long before I realized that there was no resolving this conflict. But exploring the conflict and also exploring the meeting points is interesting to me. There is great energy in their collision. (2007, p.6)

The poem-game hybrids Andrews goes on to discuss are ones he conceives of as offering immersion in the literary dimension, rather than the videogame dimension -- that is, they are works of literature where gameplay features are subordinated to literary meaning, games as literary devices. Implicitly, the alternative is videogames where literary content is subordinated to gameplay. Arteroids itself has been designed by Andrews so that the velocity of the game can be increased or decreased; at a low velocity, it is said to be a poetic text which uses gameplay as a device, while at a high velocity it is said to be a game which uses text as a component.

This apparent irreconcilability is the basis for Ensslin’s approach to poetry games, the starting point of which is that “literature and computer games are two entirely different interactive, productive, aesthetic, phenomenological, social, and discursive phenomena” (Ensslin, 2014, p.38), which in close proximity create a “phenomenological and receptive clash” (p.124), such that poetry games are, fundamentally, a paradox. The player must learn to switch between reading and playing, between intellectual and extranoematic engagement, between thinking of the poetry and thinking of the game. Just as Andrews perceives a great energy in such a clash, however, Ensslin argues that the result may be meaningfully deployed as a challenge or critique of contemporary trends in the videogame industry in particular. Her key example is Jason Nelson’s 2009 poetry game evidence of everything exploding, which Ensslin dubs a “meta- and antigame” (p.134), a game that forces players out of their playing habits by making them read and interpret poetic text in order to progress, and in doing so reflect critically on the very play activity in which they are engaged.

For Ensslin, reading and playing are two different modes of person-to-text interface. When we are doing one, we are not doing the other. The analytical tool she develops to understand the broader category of hybrid literary games is called the literary-ludic continuum, and it visualizes literariness and ludicity as traits that can be separately quantified, with literariness generally receding as ludicity increases. But when she comes to place evidence of everything exploding on this spectrum, she finds that the combination of gameplay with constant flurries of text makes its location ambivalent (p.139). It is both highly literary and highly ludic, and it is the relationship between the text and gameplay that facilitates the critique of gaming conventions.

This suggests that the image of oil and water is not quite right; the rhetorical agenda of a poem-game hybrid may be bound up in the combination of these two elements, such that there is no subordination of gameplay to literary meaning, nor literary meaning to gameplay. There is an excess of essentialism in the Ensslin-Andrews formulation that assumes, to use Andrews’ own words, that a game is something somebody wins, so something existing at the ludus end of Roger Caillois’ continuum of play (games as sets of rules), not at the paidic end (improvisation, fantasy, turbulence). Brendan Keogh has argued convincingly, in his recent A Play of Bodies, that this more traditional understanding of videogames falls short of accounting for the breadth of videogames as “corporeal, embodied, audiovisual-haptic experiences” (2018, p. 170). Rather than thinking of the gameplay experience in terms of winning, losing or accumulating, we can comprehend it as a space in which the player becomes enmeshed with various layers and dimensions of the virtual, potentially with other players as well. In theory, then, could the text of a poem not serve as one element of this enmeshment?

If that is the case, and if we can still perceive a clash, as Andrews can in Arteroids and we can in Silent Conversation, then it is caused by something more specific -- and perhaps more negotiable -- than the essential character of the poem and the videogame. What I propose to do, therefore, is to examine three of the ways the literary and the ludic are counterpointed in Ensslin and elsewhere, and in each case demonstrate that the binary is better rendered as a continuum. These perspectives can then be used as an aid in visualising where and how certain traditional traits of poetry and videogames fail to meet one another, and in considering how hybrid artefacts can avoid or meaningfully incorporate such a failure.

Text versus Cybertext

When Ensslin paraphrases Espen Aarseth’s definition of cybertext, she says that cybertexts are “ergodic digital texts that are programmed in particular ways” (my italics) (p.85). In fact, Aarseth is clear that cybertext, as a theoretical perspective, groups certain digital texts with other non-digital texts, that there is “no obvious unity of aesthetics, thematics, literary history, or even material technology” (Aarseth, 1997, p.5). Aarseth’s own distinction between the merely textual and the cybertextual depends upon the element of live computation, but even that is vexed by the various states and stages of a work. If an iteration of a text is generated through a computational process and then read back, does its cybertextuality ebb away? If so, does this mean that the videogame shown in pre-recorded footage is an altogether different kind of text to the same videogame viewed or played live? And what of the poem or other literary work which, when read for the first time, perhaps even for the second or third time, bears the trace of the processes of thought and chance that produced it -- that is to say, convinces the reader, if only temporarily, that something is being enacted before their eyes?

Aarseth spends a great deal of the first chapter of Cybertext trying to wrest his category of ergodic literature (of which cybertext is a subset) from under the disciplinary umbrella of literary criticism. He recounts his difficulty in convincing literary theorists that cybertexts exist, at last concluding that they (and his readers) must experience these texts themselves in order to properly understand how they constitute a unique phenomenon. In fact, at the time Cybertext was published, the fields of computer technology and poststructuralist literary theory were arguably already converging, as George Landau posited in his 1992 book Hypertext. Landau regarded this convergence as a major paradigm shift, where parallel critical and technological concepts based around hierarchy and linearity gave way to ones envisaging “multilinearity, nodes, links, and networks” (p.1). Since Aarseth describes ergodic literature with the model of the multicursal labyrinth, this would seem to be neatly absorbed within that paradigm shift, wherein all texts are to be understood as both labyrinths and interlocking pieces of some greater labyrinth.

What we find through Landau, particularly when he comes to engage with Aarseth directly in later editions of Hypertext, is evidence of family resemblance in the organisational characteristics of poetry, hypertext and cybertext. He answers Aarseth’s account of digital simulation as “the hermeneutic Other of narratives … bottom-up and emergent where stories are top-down and pre-planned” (Aarseth, 2004, para 52) by agreeing that there is a fundamental difference between simulation and narrative, even hypertext narrative, but adding that “the most useful point of comparison is instead to hypertext as a medium” (p.250), meaning that simulation software and hypertext networks are structurally similar. That structure is one Landau traces back to Vannevar Bush’s 1945 concept of a “mechanically linked information-retrieval machine” or ‘memex’ (p.9) that would permit scholars to move among and between articles swiftly and easily according to the associative connections between them, adding notes and comments as they go. Landau calls Bush’s vision a ‘poetic machine,’ a machine that works “by analogy and association” (p.13), imitating the logic of poetry and poetry-reading in the way it enables its users to assemble information paratactically.

Glazier, meanwhile, argues that the blurring together of author and reader in hypertext (and, by extension, cybertext) is a myth, that “the fact is, you can no more change most of the files you encounter than, as a film viewer, you can influence the father’s fate in Life is Beautiful” (p.27). This wears down Aarseth’s distinction at the other end: in any text, the content is pre-planned and largely immoveable. The illusion of emergence is created by the way technology and the actions of the user combine to cause that information to be revealed in different combinations. As Aarseth’s own example of the I-Ching demonstrates, the option is open to users of pre-digital technology to use randomising or computational methods to derive emergent experiences from a fixed linear order. At the same time, videogames are very often designed in such a way that one player’s version of the text will follow another’s almost exactly, such is the degree to which every stage of the game is designed to produce a particular result. What appears to be a labyrinth may be, in fact, a very well camouflaged corridor, while still convincing as a gameplay experience. The problem for both ergodic literature and cybertext -- as an account of videogames at least -- is that between poetry, the internet and other hypertext constructions, they appear to be surrounded by similar, if not identical structures that offer similar, if not identical, and certainly overlapping experiences.

Let us return, then, to the experience of a cybertext, and try to pin it down. Certainly if the term is designed to describe a kind of text that has proliferated greatly with the expansion of digital technology, then the figure of the videogame player, or gamer, is a direct reflection of that proliferation. So what is it that a videogame player experiences, or possesses, during play? Bernard Suits coined the term ‘lusory attitude,’ meaning a state where one “attempt[s] to achieve a specific state of affairs [prelusory goal], using only means permitted by rules [lusory means], where the rules prohibit use of more efficient in favour of less efficient means [constitutive rules], and where the rules are accepted just because they make possible such activity” (Suits, 2005, pp.54-55). In other words, the player is one who accepts an unnecessary burden in order to bring a text into a particular state of existence.

This we can contrast with the position of the reader, who expects a text to arrange itself in front of them without the need for them to submit to any constraint or responsibility, their role then being to receive, interpret or dance across it. But two things are very apparent when we state it in this way: firstly, that there are multiple ways a player might be convinced to accept their burden. These include but are not limited to: explicitly stated rules and goals, technologically implemented resistances to ease of navigation, multilinearity, the presence of input devices, elements that are generative or aleatory and modes of address that presume the existence of a player or participant. And secondly, since all of the above can exist in different combinations and to different degrees, it follows that the extent to which a lusory attitude may be possessed is also a matter of degree. A person may recognize that they are participating in a ‘sort of’ game, or that a text has a ‘game-like’ aspect to it, or that one game involves more passivity than another. The reader of a murder mystery novel may decide there is an implicit expectation that they deduce the identity of the killer alongside the detective, rather than merely awaiting the solution, and reread parts of the text in order to hunt for clues. On the other hand, a player engaged in a supposedly decision-based narrative videogame may realize, in reading about other player’s experiences, that their choices have little to no effect on the way the game unfolds, and feel less responsible for the text that emerges as a result.

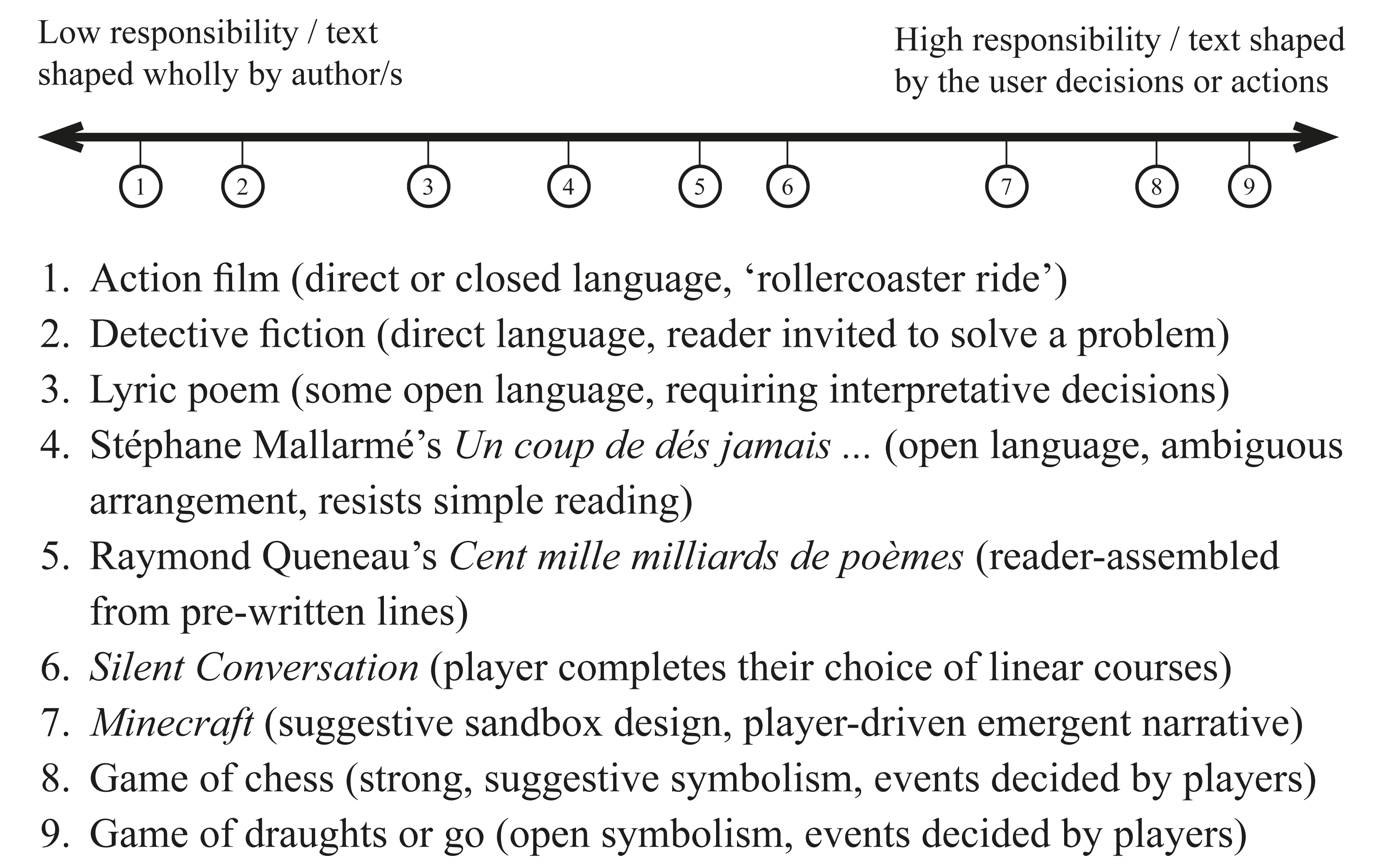

Cybertextuality, accordingly, has an ambiguous fringe; there is no clean break between what Ensslin terms ‘games proper’ and other forms of ludic text, but a hinterland of resemblances. When we come to think of cybertextuality as the basis for a distinction between poem and videogame, therefore, we ought to think in terms of a scale on which we would normally place poems quite apart from videogames. That scale, I suggest, is properly characterized by the degree to which the participating reader or player accepts the burden of responsibility for bringing the text fully into existence and maintaining it:

Figure 1. Responsibility continuum. Click to enlarge.

‘Responsibility’ does not mean the same thing as ‘agency’; it implicates the player, rather than empowering them. This is an important distinction for our purposes, since a player can be implicated even when direct control is taken away from them. This is the basis on which the videogame which is a corridor disguised as a labyrinth operates: by affording the player minimal influence while nevertheless placing them at the centre of events. Responsibility better accounts for the way a game can be stressful or infuriating, and also implies a more complex and co-dependent relationship between player and game than one where the game is an enabler or facilitator.

When we start to populate the continuum with examples, we see that videogames are fairly spread out. There is a difference between the degree of responsibility conferred upon the player of a relatively linear videogame like Silent Conversation and that conferred upon the player of a sandbox game like Minecraft. While one player proceeds from the start to the end of each level, the other is given no direction to follow, must decide on their own short-term goals, and spends much of their time in the game making creative and tactical decisions about the infinite variety of structures they can build and destroy. As for poetry, we would avoid placing it on the far left of the continuum, since there is a responsibility in the interpretative act, and more of it the more puzzling or syntactically novel a text is. A game of chess, assuming it is played by humans, would contain very little trace of external authorship at all, outside of its symbolism -- what happens and what it means is up to the players.

Figure 2. Placement of various types of text and artefact on the responsibility continuum. Click to enlarge.

What we are measuring is not, strictly speaking, a quality of the text itself, but of the reader’s relationship with it, something which the reader is able to shape themselves to some extent. This accounts for Aarseth’s difficulty in persuading poststructuralists of the existence of cybertexts; these are theorists who regard all texts from a certain perspective, with what we might call a sustained lusory attitude, even if many of those same texts would be regarded by a casual reader as offering a passive experience.

Also, if we are being entirely accurate, different parts of poems and videogames may be placed at different locations on the continuum. When a videogame employs a cinematic cut scene or screed of explanatory text, a player is likely to feel their sense of responsibility temporarily diminishing. James Newman’s ‘On-line’ and ‘Off-line’ modes of player engagement describe this in terms of a binary (2002, para 9 of 37) but there are various examples of awkward mixtures of the two, such as quick time events (QTEs), where the player must respond to button prompts in order to keep a pre-animated scene moving along. Similarly, Dick Higgins, in documenting examples of multiple-option poetry going back to 30-15 BC, observes that “what one finds most frequently is a few leonine stanzas within a long poem … following one of the principles of good rhetoric that calls for occasional variation” (1987, p.174). These stanzas, which are minor puzzles made of lines that can be read in two different ways, would be situated further to the right of the continuum than the rest of the poem, since they represent a point where a reader must make extra effort to navigate the multiple options.

We can, however, choose to nominate a position for a text based on a rough average. Indeed, we can only really regard this continuum as a way of expressing an estimation, of visualising a qualitative and malleable property. That being the case, it nevertheless gives us a good indication of how our two example poetry games work. Where the text is the interface system (as in ‘her body unswept by laughter’), a higher degree of responsibility is conferred upon the reader/player than by a static text because the player is placed at the centre of the text (via the second person address) and because they are invited to choose different paths through it. At the same time, most of the telling is left to the developer-author, freeing the player to read and interpret, as with a conventional poem. Novena, our example Bitsy game, confers responsibility through its moveable avatar, but sits at about the same place on the continuum, since it affords the player less control over the order in which they read the parts of the poem; that is, there is nothing magical about a primarily graphical interface that makes an artefact especially ludic. The difficulty with Silent Conversation is therefore not simply the result of it being a graphical videogame with a lot of poetry in it.

Deep Attention versus Hyper Attention

In Ensslin’s literary-ludic continuum, literature and videogames are mapped to N. Katherine Hayles’ concepts of ‘deep attention’ and ‘hyper attention’ respectively: competing cognitive modes which we adopt in order to engage with a textual or media artefact. Deep attention is characterized by Hayles as “concentrating on a single object for long periods … ignoring outside stimuli while so engaged, preferring a single information stream, and having a high tolerance for long focus times” (Hayles, 2007, p.187). Hayles associates this chiefly with the study of the humanities. Hyper attention, in contrast, is characterized by “switching focus rapidly among different tasks, preferring multiple information streams, seeking a high level of stimulation” and associated with the use of computers and digital media, including social media. In Ensslin’s analysis, the player of a poetry game is confronted by the need to change between these different modes -- deep to hyper, then hyper to deep, and back again -- in order to fully comprehend the text, perhaps even having to play the whole of it through twice, their mind tuned differently on the second occasion.

But the distinction between modes is murky. Hayles’ original illustration appears turn on broad stereotypes, particularly of videogame play:

The contrast in the two cognitive modes may be captured in an image: picture a college sophomore, deep in Pride and Prejudice, with her legs draped over an easy chair, oblivious to her ten-year-old brother sitting in front of a console, jamming on a joystick while he plays Grand Theft Auto. (p.188)

Ensslin argues that the distinguishing feature of hyper attention is its relationship to addiction and, rather confusingly, that it means being drawn in more deeply to the point of ignoring basic needs. Videogames induce this cognitive state through multisensory stimulation and by representing information through combinations of image, text, sound and occasional haptic feedback, as well as through the structure of the challenges they set, which tend to increase in difficulty and variety by stages. What is not clear is why this should act as a barrier to attentive reading when text is embedded in a videogame. In contrast to Hayles’ image of the college sophomore absorbed in Pride and Prejudice, Ensslin appears to treat deep attention as a kind of detached critical scrutiny. Poetry games -- and, more broadly, what she calls ‘art games’ -- achieve the effect, she says, of forcing the player to see the game as a text to be studied and interpreted, something which is not normally possible while taking part in gameplay.

There are problems with this formulation. It dismisses far too readily the ability of the player to deploy critical thinking while playing -- either during less busy sections of a game, or by deliberate holding back, or even because their level of ability is such that playing the game requires minimal mental resources. Popular streamers of videogame content routinely demonstrate both the capability and the inclination to assess and interrogate videogames while they are navigating them, albeit with little regard to any literary dimension. Ensslin also ignores the extent to which reading poetry and other literary texts involves both periods of absorption and periods of reflection, which can also be understood as distinct cognitive modes. Her version of hyper attention seems to correspond to Mihály Csíkszentmihály’s concept of flow -- the state of being fully and enjoyably immersed in a task to the point of a loss of sense of space and time (Csíkszentmihály, 1975). Certainly, this concept has been used by both game scholars and games industry professionals to explain one of the core experiences at the heart of the most successful videogames (Madigan, 2010), but it is neither the preserve of videogames nor an easy state for them to induce. The actual experience of both playing a videogame and reading a work of literature is too messy and too variable to be captured by a pair of oppositional states.

It is the case, however, that videogames are equipped, technologically and phenomenologically, to absorb players more deeply over a longer period; the question is whether these powers can be used in conjunction with the kind of attention poetry commands, or whether the two are irreconcilable. When we look at the sheer variety of ways information streams are combined in videogames and the subtle variations in the styles of engagement they solicit, it is difficult to see why literary content should stand out as presenting a unique problem. The Grand Theft Auto series may call for fast reflexes and fine motor control, but also enables the player to tune into radio stations and listen to music or conversation -- either while driving or parked up at the side of the road. In The Talos Principle (Croteam, 2014), three-dimensional kinetic puzzles are interspersed with an evolving narrative told through emails and audio recordings, and the player is routinely directed to reflect on philosophical questions of selfhood and purpose. The Talos Principle shares with a number of other games -- including The Stanley Parable (Kevan Brighting, 2011), Portal (Valve, 2007) and Inside (Playdead, 2016) -- a concern with digital embodiment and relationships of control among player, avatar and videogame, foregrounding these issues both narratively and mechanically.

In Planescape: Torment (Black Isle Studios, 1999) and its successor, Torment: Tides of Numenera (inXile Entertainment, 2017), players are able to choose whether to settle conflicts through negotiation -- a route that involves reading and assessing dialogue options -- or by strategic combat, which takes the form of micro-managing the actions and abilities of a team of combatants. The graphics in both titles are supplemented by substantial amounts of textual description in order to convey a more detailed account of the world, with Planescape: Torment’s script comprising roughly 950,000 words. The player reads, reflects and reacts, and this in itself constitutes the gameplay; the positioning of the characters on the screen is important, but not so much that it must be studied or adjusted continuously. For much of the game, in fact, these characters remain rooted to the spot while conversing.

One thing we might suppose, however, is that some styles of attention diverge from one another more dramatically than others, and that some combinations are therefore more harmonious than others. Disharmonious combinations can be utilized both critically and creatively, and it is this that Ensslin has in mind when she contrasts deep and hyper attention. Hayles’ illustration of the distinction is compelling because it is difficult to imagine the reader of Pride and Prejudice being able to vault from her couch and switch seamlessly to driving at speed through a busy city in Grand Theft Auto, or for the changeover to occur in the opposite direction, even if the narratives of these texts were interwoven. But why is this exactly?

When analysing evidence of everything exploding, Ensslin argues that “players in the hyper-attentive mode are likely to find the superimpositions [of explanatory text] distractive and annoying because they impede fast-paced, successive gameplay” (p.132). The key words here are ‘fast-paced’ and ‘successive.’ Where a videogame is made up of rapid concatenations of events, with the player drawn into a constant cycle of action and reaction, it is not surprising that switching to a slower, more cerebral type of engagement might be jarring. But the sense of an interruption is nowhere near as evident, if it is evident at all, where gameplay already centres on information-gathering, cautious exploration and testing of processes, as in Planescape: Torment or The Talos Principle. In that context, stopping to read explanatory text does not bring to a halt any rapid forward momentum, and the player is unlikely to perceive that they are being jolted out of their pilot’s seat.

I propose, therefore, a second continuum that runs from ‘negotiation’ as the dominant form of reader/player interaction -- meaning the demand that a conscious effort be made to examine the components of a text so as to make sense of them -- to, at the other extreme, continuous emphasis on achieving ‘flow,’ where a reader/player is able to lose themselves in the fast-moving current of events . There is a healthy middle ground to be filled with complex examples; the levels of early Tomb Raider games, for instance, are giant puzzle cubes that must be negotiated carefully, but they are also dotted with sections where the player must transition to action mode in order to fight enemies. In oral poetry there is a mixture of a negotiative element, whereby the audience listens closely in order to pick out linguistic patterns and subtleties of meaning, and striving to achieve a rhythmic pulse, the latter usually dominating. Epic poetry, with its emphasis on narrative and regularity of line, is to be found somewhere near the middle of any negotiation-flow continuum. Poetry on the whole, though -- certainly lyric poetry -- predominantly resides on the left-hand side, making it liable to serve as interruption to any gameplay activity that builds toward flow.

Figure 3. The negotiation-flow continuum. Click to enlarge.

What I would suggest is that as one travels right on this continuum, it becomes increasingly difficult for both the player and the designer of an artefact to manage transitions from one kind of activity to another, in the same way it is difficult to leap from one moving car to another. A pace must be maintained, and the dramatic events of a plot that one is following through the pages of a book or a cinematic rendering do not prepare one for being placed at the controls of a vehicle or avatar. Flow means being caught up in one particular mode of interaction, and transitioning usually means becoming aware of oneself again. The same is not true on the left-hand side of the continuum, since the player/reader involved in a negotiation-type activity is more conscious of themselves and their attention as an adjustable component.

Videogames span the entirety of this continuum; their popular image, however, tends towards intense action, while the popular image of poetry tends toward the most cerebral forms. This, perhaps, is the crux of the Ensslin-Andrews formulation that conceptualizes the two as phenomenologically incompatible. Ensslin’s category of literary videogames, which includes poetry games, is conceived as a literary interruption of those mechanisms in videogames which are designed to facilitate flow, while her category of ludic digital literature is derived from focussing on negotiation-type activities within multilinear digital fiction.

Again, when we look at our two example poetry games, we find that the simple explanation for their coherence is an aversion to game mechanics based around fast movement and reaction time. Or rather, the limitations of Twine and Bitsy as tools force developers to think in terms of the left-hand side of the continuum, where the kind of attention demanded of the player is closer to that demanded by poetry. In Bitsy’s case, the games produced are tile-based and made from a series of static (ie. non-scrolling) rooms. The player controls a simple avatar with a fixed movement speed, either with the arrow keys or by swiping on a touch-screen device. They can interact with some objects, prompting text boxes to appear, but they cannot die or use weapons. There is limited, if any, capacity to gate player progress with complex mechanics. All sprites, tiles and objects within the game are limited to two colours and an area of 8x8 pixels.

In Novena, the player returns to the same shore every day over nine days, taking to the water to converse with a mysterious, monk-like figure. There is no pressure to perform this routine quickly. The lineated stanzas and iterative repetition which take up a good proportion of the game’s short length require, therefore, only a slight adjustment in playerly attitude. In contrast, Silent Conversation, being modelled on a conventional platformer, subjects the player to a timer and forces them to react to projectiles in order to avoid punishment. We would place it toward the right of the negotiation-flow continuum, where both self-reflection and consideration of literary meaning on the part of the player is that much more difficult.

Rules versus Irresolution

A third way in which the literary and the ludic are counterposed is by reference to Caillois’ concepts of ludus and paidia. Although the Latin word ‘ludus,’ from which the term ‘ludic’ is derived, means ‘play’ or ‘fun’ in general, in Caillois’ scale it refers specifically to play arising from arbitrary rules and boundaries, and when Ensslin talks of ‘games proper’ she means games that are bound by rules. While she concedes that there are rules governing language, she characterizes the play of literature as playing with the rules, rather than by them, thereby placing poetry at the paidic end of Caillois’ scale: play as turbulence, subversion, unpredictability.

This distinction has implications for the expressive coherency of poem-game hybrids. Ian Bogost’s concept of ‘procedural rhetoric’ (Bogost, 2007), widely accepted as an account of how games say and mean, locates videogame expressivity in rules and process. The values and the philosophy of a videogame, according to this theory, are manifested in the outcome of the player’s interactions; that is, the player learns by doing rather than seeing, not only in the sense that they learn how to win the game but in the sense that they comprehend through it a model of cause and effect. If, for example, in a team-based videogame, the game kills any player who strays too far from the rest of the group, an argument (however weak) is being made in favour of teamwork and against individual impulsivity. Bogost, along with many other theorists, is eager to see this form of rhetoric tuned to much more nuanced and productive ends than teaching players to shoot first and ask questions later, but its power undoubtedly rests in clarity of rule and resolution. A simulation should consistently produce the same results, given the same input, if it is to have demonstrative force.

In contrast, the expressive potency of poetic language rests in its semantic instability. As Umberto Eco puts it, the poetic effect of a text is the capacity it displays to go on generating new readings, to resist being ‘solved’ once and for all or reduced to a lesson (1984, p.545). This would seem to be antithetical to the workings of procedural rhetoric. Poetry ‘means’ by leaving doors open; a game ‘means’ by showing how they may be shut.

Caillois, however, envisages a kind of see-saw effect over successive generations, with rules emerging to govern and constrain paidic rituals while ludic systems are disrupted and subverted by the instinct toward free play. We must, again, avoid essentialism; there are readings of even complex poems that achieve a comfortable dominance over other interpretations, and poetic language may be mostly straightforward in the way it arranges its internal problems and solutions. Similarly, videogames are capable of retaining a degree of irresolution and ambivalence alongside systems that are designed to lead the player to a particular end. Miguel Sicart delineates between “instrumental play” (Sicart, 2010, para 76 of 84), the designed experience of the game, and what he argues constitutes the actual locus of videogame experience, “the performative, expressive act of engaging with a game” (para 82 of 84). Sicart attacks Bogost’s proceduralism as “a determinist, perhaps even totalitarian approach to play; an approach that defines the action prior to its existence, and denies the importance of anything that was not determined before the act of play, in the system design of the game” (para 45 of 84). He prefers to think of videogame play as messy and personal -- paidic, in fact. Any message, he says, ought to emerge from a conversation between player and designer mediated by the videogame’s interface. Mary Flanagan similarly prescribes “the shifting of authority and power relations toward a nonhierarchical, participatory exchange” (Flanagan, p.256) in her own argument toward critical game design.

Accordingly, some videogame developers actively pursue a level of non-didactic mechanical complexity that makes it impossible for them to predict all the ways a game can be played, hoping to encourage what they call ‘emergent gameplay’ -- that is, gameplay driven by the imagination of the player. The principle behind this thinking is not dissimilar to the principle behind the poem’s (ideally) boundless capacity for reinterpretation: that there is joy to be found in a text with no ending or ultimate resolution, a text that retains a mysterious charge for as long as there are minds willing to creatively engage with it.

In their paper “Ambiguity as Resource for Design,” Gaver, Beaver and Benford list three categories of ambiguity which may be implemented in rule-driven systems -- ambiguity of information, ambiguity of context and ambiguity of relationship -- and explore how, far from interfering with those systems, each category can be used to “encourage close personal engagement” (2003, p.233). Ambiguity of information is the most obvious of these, pertaining to all the information represented in the system, visually, sonically, textually. Their example is a mixed-reality game called Bystander, in which two players are supplied with incomplete and sometimes inaccurate information as to their target’s whereabouts:

The traditional response to ambiguity of information in interactive systems … is to improve the technology, use statistical methods to set certainty thresholds, or ignore it and hope for the best … Rather than seeing uncertain GPS information as a flaw, Bystander treats this ambiguous information as a challenge to users, forcing them to join their knowledge of people and cities to the clues in order to play the game. (p.236)

Provoking the user of a system to look beyond that system for solutions causes them to consider its relationship to the wider world. A similar effect can be achieved by inviting scepticism through overstatement, inconsistency or betrayal. Probably the most famous example of the latter in a videogame is found in BioShock (2K, 2007), which waits until its final act before revealing that the player is a pawn of one of the game’s major villains, and that the actions they have taken throughout the game are not, in fact, in service of a moral good. As procedural rhetoric, the game’s message is therefore deeply ambivalent.

The second category, ambiguity of context, refers to the intended purpose of a tool or piece of information within a system. Subverting or removing expected functionality, or adding incongruous extra functions are ways of prompting users to rethink an object conceptually, to probe beyond its relationship to goal completion. Gaver et al use the example of a mobile phone designed by Sarah Pennington which lacks ‘call’ and ‘receive’ keys. To pick up on one of our earlier examples, The Talos Principle directs players toward philosophical problems by repeatedly asking them questions to which there appear to be no right or wrong answers -- at least, not in terms of where the game itself accords value. The player can even choose to disengage entirely from the questions without negative consequence, and must use their own judgement in weighing the importance of these interactions to the overall game experience.

The final category, ambiguity of relationship, concerns the relationship of user to system: what role the user is expected to play, how the system is designed to serve them, whether it is designed with them in mind at all. This kind of ambiguity, skilfully deployed, prompts self-reflection, and reconsideration of the meaning of the system. It is here where poetry and commercial videogames most frequently part company, since videogames are proffered by their distributors as toys and leisure devices, intended for the provision of amusement, empowerment, pleasurable stimulation. Ambiguity in this area risks the user judging the artefact to have failed its purpose, or else declining to engage in the first place, since they may fail to understand what they are to ‘do’ with the game. The struggle contemporary poetry faces in building and sustaining a mass audience is largely accounted for by its ambiguous relationship to the reader. It is alternately suggested as entertainment, nourishment, medicine and cultural exhibit, but its practitioners openly rebel against these labels, finding them reductive. Individual poems may evince the character of an anecdote, a confession, a sermon, a riddle, a story, advice, an examination or stream of consciousness. This restlessness is tied to poetry’s mystique, its reputation for philosophical depth. There is no practical or technological reason why a system (and therefore a videogame) cannot follow suit, except that to do so is to flirt with commercial failure.

In the case of Nelson’s evidence of everything exploding, the tendency to interrupt fast-paced, stimulating gameplay with lengthy sections of poetic text disrupts an apparently familiar user-system relationship, rendering it ambiguous. But the option is open to designers of poem-game hybrids, as well as other kinds of experimental or ambitious videogame, to make such interruptions less jarring, and to make the user-system relationship ambiguous from the start. The Talos Principle again serves as an example: its puzzles are immediately contextualised within the narrative as having been conceived for a mysterious purpose. Its sections of text-only content are accessed from computer terminals set up throughout the three-dimensional environment, and the player reads through them voluntarily in order to better understand what is achieved, in the world of the game, by solving the puzzles. While there is sufficient consistency in the rules for it to function as a game of steadily increasing difficulty, and sufficient narrative structure for its ending to provide a satisfying resolution, there is also a lasting ambiguity as to whether the game is a piece of entertainment, a kind of treatise or an interactive experiment. Thus, ludic and paidic play can exist alongside one another.

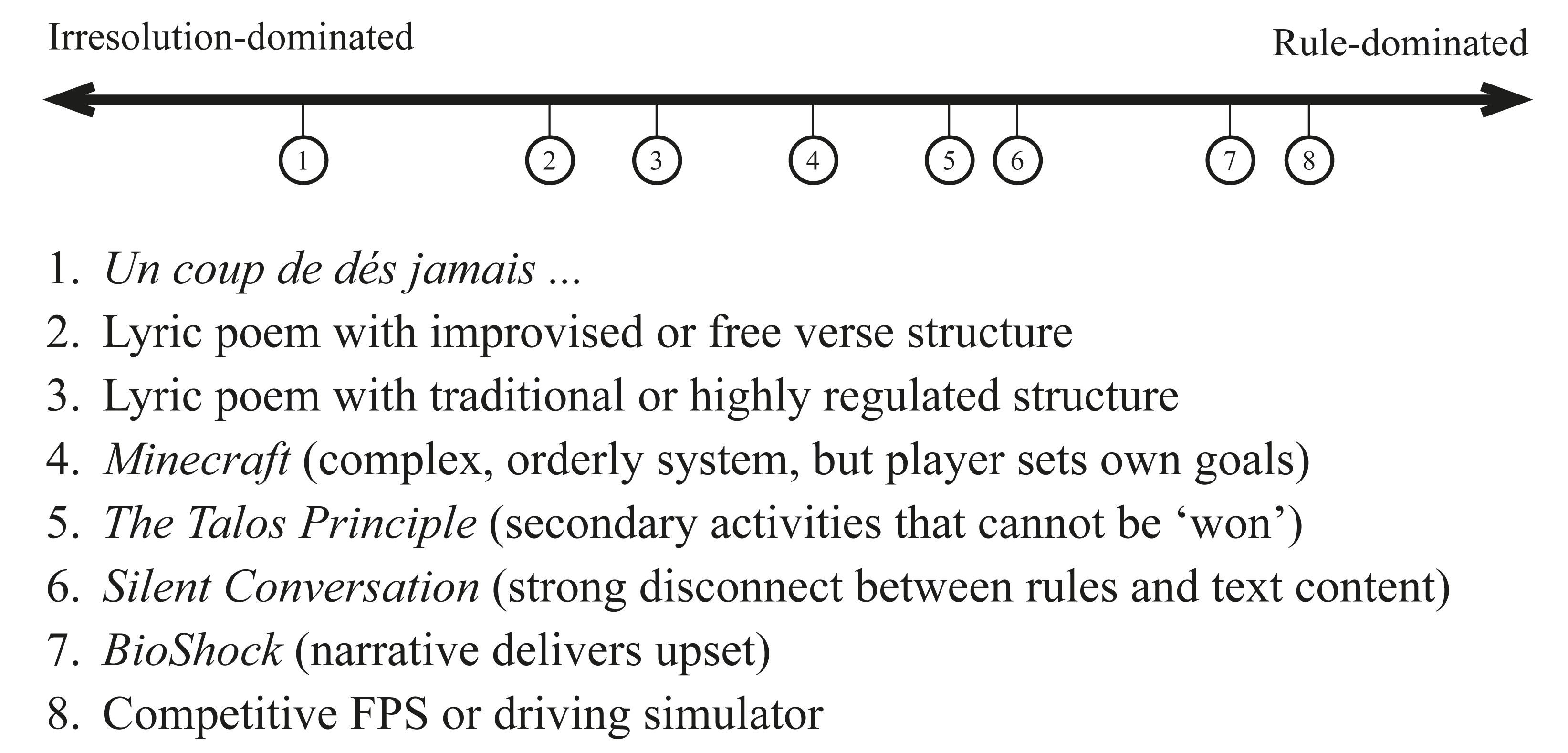

The third continuum I want to propose, then, is in essence Caillois’ paidic-ludic continuum, except that I label the extremes as ‘irresolution-dominated’ and ‘rule-dominated.’ Texts and artefacts that lie toward the right end of this continuum tend to resolve themselves completely through application of rules (be they rules of narrative or poetic logic or ones that envisage the participation of a player), while texts and artefacts that lie toward the left end remain open-ended, in a kind of turmoil.

Figure 4. The irresolution-rules continuum. Click to enlarge.

It is difficult to place broad categories of media on this line, or to confidently place anything toward the extreme ends, because there is so much flexibility in the way ambiguity can be combined with resolution. But by approximately positioning genres and individual texts, we can easily understand why poem-game hybrids like Arteroids and Silent Conversation struggle to combine poetry and gameplay mechanics in a way that allows the powers of each to work harmoniously. In the standard version of Andrews’ Arteroids, the player pilots a single word or phrase and must shoot flying fragments of poetry and text in order to stop them reaching the player avatar and destroying it. No matter how much the game is slowed down, the conditions for failure are clear, and the player’s score and accuracy are measured numerically. It is a rule-dominated system that teaches the player to destroy as much as possible, for as long as possible. The deeply cryptic fragments of poetry do little in themselves to subvert this system, and nothing in the game’s design directs the player to accord them any relevance beyond what they represent as targets and enemies. The oil-and-water effect is felt because there is a little-to-no resonance between what can be read and what is procedurally learned.

Interestingly, there is a variation of the standard game where the player avatar can be replaced with the word self-worth, while the flying fragments read discouraged, invisible, afraid, neglected and so on. Here there is a crude semantic logic to the act of destroying the fragments. The open-endedness of the linguistic component has been turned down, not just in the sense that there is a clear theme expressed in the words on the screen, but also in the sense that the mechanics of the game are now a factor in how that message is conveyed: negative feelings need to be shot down, as it were, in order for self-worth to survive. With this adjustment, we can more confidently place Arteroids toward the right of the rules-irresolution continuum. In the process, however, its poetry has become entirely trite.

Silent Conversation, similarly, teaches the player to regard the words that make up its levels as identical units. Each contributes equally to the overall level completion, and the player is awarded a higher grade the faster they collect them. There is correspondingly little effort to direct the player toward any ambiguity of information, context or relationship. It functions very neatly, in fact, as a series of totally abstract challenges to be won. In contrast, the examples of poetry games made in Twine and Bitsy avoid grading, scoring or failing the player. Their procedural logic is only lightly imposed, guiding the player toward an ending of sorts. This affords much more room for an open rhetoric, as embodied in their poetry, which means they would be placed somewhere in the centre-left of the continuum.

Conclusions

Taken together, these three continuums not only articulate precise tensions between poetry and videogames that developers of poetry games need to negotiate, but also explain why tools like Twine and Bitsy have become popular as a means of experimenting in this area, beyond their ease of use. Rule-dominated systems that articulate their values in the form of procedural rhetoric, especially those that enforce speedy decision-making and which are designed to induce a state of flow, make it difficult for the player to enter an interpretative, critical or reflective state and therefore to meet the intellectual demands of poetry. Complex feats of programming that enable emergent gameplay and nonhierarchical, participatory exchange between player and developer risk running afoul of the responsibility continuum in terms of their capacity for poetic expression on the part of the developer. Simple interactive systems allow a balanced approach to the designation of responsibility -- the player implicated in proceedings but the developer still directing them -- without imposing scores or goals that overwrite semantic nuance.

Poem-game hybrids remain a nascent genre in both literary and gaming culture, and it is likely that developers and authors alike will go on finding other, innovative methods for addressing the tensions described in these continuums. I have not addressed in this article, for instance, examples of videogames that attempt to embody the poetic not through integration of poetic language but through paratactically expressive visual and mechanical design. Such artefacts may not be ‘poetry games’ according to the definition we have been using, but they do represent another meeting point between poetry and ludicity. What is demonstrable, however, is that the inclusion of poetry as an integral component of a videogame or other ludic artefact does not automatically lead to it behaving as a separate, alien substance, and therefore those elements of poetry and ludicity that are attractively compatible may be given room to operate alongside and through one another across further generations of poem-game hybrid.

References

2K Games. (2007). BioShock [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game developed and published by 2K Games.

Aarseth, E. J. (1997) Cybertext. Baltimore, Maryland: The John Hopkins University Press.

Andrews, J. (v. 3.1) [2003-2017]. Arteroids [Online Game]. Digital game published by Jim Andrews. Accessed May, 2018. http://vispo.com/arteroids/arteroids312.zip.

Andrews, J. (2007) Videogames as Literary Devices. Available from: www.vispo.com/writings/essays/VideogamesAsLiteraryDevices.pdf [accessed 26 May 2018].

Andrews, J. (2015) Arteroids Homepage. Available from: www.vispo.com/arteroids/indexenglish.htm [accessed 26 May 2018].

Black Isle Studios. (1999). Planescape: Torment [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game developed by Black Isle Studios, published by Interplay Entertainment.

Bogost, I. (2010) Persuasive Games. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Caillois, R. (1958) Man, Play and Games. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Croteam. (2014). The Talos Principle [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game developed by Croteam, published by Devolver Digital.

Csíkszentmihály, M. (1975) Beyond Boredom and Anxiety: Experiencing Flow in Work and Play. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Eco, Umberto (1984) The Name of the Rose: including Postscript to the Name of the Rose. Translated from the Italian by William Weaver. New York: First Mariner Books.

Ensslin, A. (2014) Literary Gaming. Cambridge, Massachusetts, The MIT Press.

Flanagan, M. (2009) Critical Play: Radical Game Design. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Galactic Cafe. (2011). The Stanley Parable [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game published by Galactic Café.

Gaver, W.W., Beaver, J. and Benford. S. (2003) Ambiguity as a Resource for Design. Available from: www.academia.edu/868863/Ambiguity_as_a_resource_for_design [accessed 15 June 2020].

Glazier, L.P. (2002) Digital Poetics: The Making of E-Poetries. Tuscaloosa and London: University of Alabama Press.

Hayles, N. K. (2007) Hyper and Deep Attention: The Generational Divide in Cognitive Modes. In: Profession, pp. 187-199.

Higgins, D. (1987) Pattern Poetry: Guide to an Unknown Literature. New York: State University of New York Press.

inXile Entertainment. (2017). Torment: Tides of Numenera [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game developed by inXile Entertainment, published by Techland Publishing.

Keogh, B. (2018) A Play of Bodies: How We Perceive Videogames, Cambridge, Massachusetts, The MIT Press.

Landow, G. P. (1992) Hypertext: The Convergence of Contemporary Critical Theory and Technology. Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press.

Mojang Studios. (2011). Minecraft [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game developed by Mojang Studios, published by Mojang Studios, Microsoft Studios, Sony Interactive Entertainment.

Newman, J. (2002) The Myth of the Ergodic Video Game. Available from: www.gamestudies.org/0102/newman/ [accessed 15 June 2020].

Nurbrun. (2020). her body unswept by laughter [Online Game]. Digital game published by Nurbrun. Accessed February 2021. https://nurbrun.itch.io/her-body-unswept-by-laughter.

Playdead. (2016). Inside [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game developed and published by Playdead.

Richard, Cecile. (2020). Novena [Online Game]. Digital game published by Cecile Richard. Accessed February 2021. https://haraiva.itch.io/novena.

Rockstar North, Digital Eclipse, Rockstar Leeds. (1997-2013). Grand Theft Auto [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game series developed by Rockstar North, Digital Eclipse, Rockstar Leeds, Rockstar Canada, published by Rockstar Games.

Sicart, M. (2010) Against Procedurality. Available from: www.gamestudies.org/1103/articles/sicart_ap [accessed 8 August 2018].

Suits, Bernard (2005), The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia, Broadview Press.

Valve. (2007). Portal [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game developed and published by Valve Corporation.

Weir, Gregory. (2009). Silent Conversation [Online Game]. Digital game published by Gregory Weir. Accessed June 2020. https://futureproofgames.itch.io/silent-conversation.