Play Your Own Way: Ludic Habitus and the Subfields of Digital Gaming Practice

by Milan JaćevićAbstract

Existing research on players of digital games has shed light on general player attributes, such as preference or skills, that differentiate one player from another. However, there is currently a lack of models comprehensively accounting for the manifestation of these attributes in the moment of play of a given game. This paper takes steps towards addressing this research gap. It combines Bourdieusian practice theory with an exploratory qualitative study of two groups of players and their behavior in two custom digital games. The paper empirically develops the concepts of ludic habitus and generic subfields of practice. These concepts account for how past player experiences manifest in the act of gaming practice in response to minute design variations. In this way, the paper lays the foundation for a theory of digital gaming practice, which aims to connect a player’s previous play experience and history with their moment-to-moment gameplay interactions.

Keywords: player studies, practice theory, ludic habitus, generic subfields of practice, exploratory study

Introduction

A player, controller in hand, is looking at a computer screen, showing a two-dimensional scene consisting of only a few elements. On the left: a small, white block that they control, with black dots for eyes. On the right: several tiny, yellow circles floating high in the air. In the middle: hovering platforms are placed just a bit higher than the white block, and quite close to the yellow circles. A red, bug-like creature enters, stage right. It is moving to the left, directly towards the white block… How does our player interpret the scene? What do they do? Perhaps most importantly -- what do the answers to questions like these depend on?

Previous research on digital game players has often highlighted and categorized differences between players in terms of their approaches to playing games. Examples include typologies of player behavior, often in relation to specific games or game types (e.g., Bartle, 1996; Drachen et al., 2009, Kallio et al., 2011), and more general psychometric models of motivations and aims of playing (e.g., Yee, 2006; Zackariasson et al., 2010). Researchers of gaming culture have also frequently examined differences between players and their relationship to games and gaming, often with a critical look on social constructions of gamer identities and the values attached to particular ways of playing. Such research has offered important insights on gameplay activities in light of issues like gender (Carr, 2011), race (Gray, 2014), age (De Schutter & Vanden Abeele, 2008), and identity construction (Shaw, 2011), among others.

We now know much about individual attributes which mark one player as different from another. However, we still lack holistic models of players to understand how individual differences -- in playstyle, motivation, preferences, broad-cultural and game-domain-specific knowledge, experience, and skills, among others -- converge and manifest when particular players sit down to play a particular game. Without such a model, we may never have more than partial answers to the questions about our player mentioned earlier.

How do differences between players materialize in the act of gaming practice, as a response to particular elements of game design? This paper is the first part of a larger research project seeking to explore this question by combining social scientific theories with prototype creation and experimental playtesting. The research in this paper draws on practice theory, specifically Pierre Bourdieu’s concepts of habitus and field, which it extends to the domain of digital games. In order to examine the moment-to-moment interactions between player attributes and game design elements, the research presented here takes the form of an exploratory qualitative study, which sought to explore how players with different degrees and types of gaming experience perceive and practically navigate small differences in game design. Observations from the study serve as empirical grounds for the identification of a game-related or ludichabitus: a personal set of perceptual, evaluative, and performative patterns that guide both a player’s concrete engagement with digital games and their identification of game types. These game types are understood as specialized generic subfields of practice requiring specific modes of play. By empirically developing these two concepts, this research seeks to connect psychological and sociological attributes of players of digital games to players’ practical gameplay interactions with specific game design choices.

The paper is structured in four parts. The first part presents the tenets of practice theory and Bourdieu’s concepts of habitus and field alongside examples of prior habitus (and similar, related) research in the domain of digital games and gaming. The second part presents the methodology and results of a qualitative player study, which serves as means of generating empirical data for the development of the concepts of ludic habitus and generic subfields of practice. This development is presented in part three. The paper ends by reflecting on the limitations and challenges of the conducted exploratory study, and by sketching out future steps in the larger research project of developing a Bourdieusian theory of digital gaming practice.

Literature review

Bourdieusian practice theory

Practice theory looks at examples of enduring, mutually constituting relationships between agents on the one hand, and global systemic entities on the other (Ortner, 1984, p. 148). According to Davide Nicolini, practice theory can be said to present a view of the social world as “a vast array or assemblage of performances made durable by being inscribed in skilled human bodies and minds, objects and texts and knotted together in such a way that the results of one performance become the resource for another” (2017, p. 20). This performance-centric worldview makes practice theory a fitting lens for examining digital games, due to their fundamentally processual nature (see e.g., Galloway, 2006 and Malaby, 2007, for more on this discussion).

One of the scholars most frequently associated with practice theory is Pierre Bourdieu, whose conceptual framework is particularly pertinent for examining how players categorize and navigate digital games in the act of play. For Bourdieu, participation in a given practice over time results in the development of habitus -- a set of relatively durable, transposable dispositions which guide our understanding of the practice in question and facilitate sensible, intuitive performance (1972/2013, p. 72). The dispositions which make up habitus operate as “a matrix of perceptions, appreciations, and actions” (p. 83), and emerge from one’s involvement in a particular field of practice -- a social setting which imposes certain constraints and demands on the agents that operate within it (Bourdieu, 1990, p. 63). As such, every habitus is distinctly corporeal, both acquired and deployed through active bodily participation in a particular field. Appropriately, Bourdieu illustrates this by recourse to a sports metaphor. A practitioner in any field is like a tennis player in the middle of a match, possessing a set of knowledges and skills acquired through experience and training, and which are able to be translated into a sensible, intuitive, logical performance (Bourdieu, 1990, pp. 11; 61). Later authors, such as Omar Lizardo, have referred to habitus as “a socially produced cognitive structure” (2004, p. 393), highlighting the constructivist and cognitive aspects of the concept.

Habitus in game and player studies

The concept of habitus has previously been used in the field of game studies, predominately in one of two ways. On the one hand, habitus has been used to investigate gaming as a cultural domain. For example, as part of his exploration of the formation of gaming culture in the United Kingdom in the 1980s, Graeme Kirkpatrick has focused on the role of gaming discourses (principally those constituted by game magazines) in the early constitution of gamer identity (2015, p. 23). For Kirkpatrick, this identity is enshrined in what he refers to as gamer habitus, “the socially acquired, embodied dispositions that ensure someone knows how to respond to a computer game” (p. 19). Along similar lines, Feng Zhu used habitus to discuss Foucauldian practices of the self in relation to computer games (Zhu, 2018). Mia Consalvo has also touched upon the concept of habitus in her work on gaming capital, a reworking of Bourdieu’s notion of cultural capital, which she uses to refer to games-related knowledge and resources utilized as part of social interactions within the gaming field (2007, p. 18). Chris Walsh and Tom Apperley have drawn on Consalvo’s work in their further elaboration of gaming capital as an alternative to the concept of game literacy; in their work, the authors link gaming capital to habitus, but stop short of elaborating the latter concept within the domain of gaming (Walsh & Apperley, 2009).

On the other hand, habitus has also been utilized in empirical research involving specific games and/or players. Examples of this kind of approach to habitus include the work by Wallace McNeish and Stefano De Paoli, who have investigated socialization processes among students at a university in Scotland, resulting in the students’ development of a game-related habitus (2016). Another notable example of empirical habitus research in the domain of games is the work of David Dietrich on avatar creation possibilities in MMORPGs and offline RPGs (2013). Dietrich has analyzed capabilities for avatar creation in eighty different games, finding that a vast majority did not facilitate non-white racial appearance and implicating these limitations in the reinforcement of a racialized “white habitus” (2013, p. 97).

Related concepts and theories

In research on games and gaming, aspects covered by Bourdieu’s concept of habitus have also previously been researched under different framings. One example of this is the concept of technicity, present in the work of Jon Dovey and Helen Kennedy (2006). Drawing on Donna Harraway’s (1985/1991) cyborg theory and expanding on previous work (e.g., by Tomas, 2000), Dovey and Kennedy use the concept of technicity to refer to “identities that are formed around and through […] technological differentiation” (2006, p. 16, italics original). The authors use technicity alongside Bourdieu’s idea of cultural capital to discuss hegemonic dominance of certain taste groups and identities (e.g., white males, frequently associated with digital games) at the expense of others (e.g., women game designers and developers, frequently excluded from mainstream discourses on digital games) within the broad sociocultural field of gaming. Another aspect of Bourdieu’s understanding of habitus, corporeality, has previously been explored in games research in relation to various topics -- embodiment or incorporation (Calleja, 2011; Farrow & Iacovides, 2014), kinesthetics of play (Giddings & Kennedy, 2010; De Castell et al., 2014), affective pleasures (Lahti, 2013), and, more broadly, phenomenology of play (Crick, 2011; Keogh, 2018) to name but a few. Scholars have also previously offered holistic frameworks for approaching and researching experiences of digital gameplay, highlighting their multifaceted, situational, and contextual aspects (see e.g., Taylor, 2009, and the notion of assemblage; or Barr, 2008, and Nardi, 2010, for examples of applying activity theory to digital games).

Habitus in the act of play

The present research differs from previous related work in game and player studies in its examination of habitus as a productive force in the act of playing digital games. While previous research on habitus has focused more broadly on gamer identity and gaming culture, it is important to keep in mind that habitus is here approached in different fashion -- as a matrix of player attributes which, when deployed in gaming practice, help the player understand and play particular digital games in a particular, player-specific manner. This approach is in line with Bourdieu’s framing of habitus as the core component of practical activities, acting as a principle behind their generation and organization (Bourdieu, 1980/2014, p. 53). The holistic, generative nature of habitus is what makes it a particularly useful concept for analyzing digital gameplay, both at specific moments during play of specific games and as a long-term practical activity that shapes the players’ minds and bodies in unique ways.

It is important to note that the approach to game-related (or, ludic) habitus in this paper does not dispute its sociocultural aspects and functioning. Rather, the paper simply explores how this form of habitus aids players in navigating the moment-to-moment act of gaming practice. In doing so, it is meant to act as complement to previous sociological research on this concept within the field of gaming, as well as to similar, related concepts mentioned in the previous section. The paper’s examination of the practical aspects of one’s ludic habitus provides the basis for the understanding of the player as a historically developed practitioner of gaming, thus providing answers to the questions about our hypothetical player from the introduction concerning their views on and experience of a given digital game.

Methodology

This research took on an exploratory, pragmatic approach to investigating ludic habitus in the act of gaming practice. Specifically, this approach consisted of a small-scale, qualitative player study using custom-made digital game prototypes. Rather than attempting to establish a definitive understanding of ludic habitus and its role in the act of playing digital games, the study seeks to explain the logic of lucid habitus in operation. It does so, specifically, by investigating how players with different degrees and types of gaming experience understand and respond to minute game design differences. This research question motivated the study design and its methodology, which included game design practice and prototype creation, qualitative research as a general strategy, grounded theory as an approach to theory development, and the particular methods of data collection and analysis; all of which will be further discussed below.

The player study should be understood in light of its preliminary, exploratory character: it empirically establishes ludic habitus and generic subfields of practice as concepts, and sets the foundation for their further research and expansion with the goal of deepening our understanding of the player-game relationship.

Prototype design

Rather than utilizing commercially developed digital games, the study opted for custom-made digital game prototypes. Several reasons motivated this decision, principal of which was the study’s focus on player perception and navigation of minute design differences. This focus spoke in favor of developing custom games, which could be specifically designed so that they differed as little as possible from one another. What’s more, developing specific games for the study enabled their design differences to be fine-tuned to the point where they could be specifically accounted for by the designer/researcher behind the study during the processes of data collection and analysis. Finally, the act of designing the game prototypes also enabled the researcher to get practically acquainted with their gameplay experience and design differences in a manner of observant participation; similar to how certain scholars have researched habitus in the past (see e.g., Wacquant, 2011, for one example of this). This participation informed the latter processes of participant observation and interviewing, and thus contributed to greater depth and a unique perspective on the research topic.

The two digital game prototypes used in the study were developed in the tradition of A/B testing (Hanington & Martin, 2012). The first served as the control game (Figure 1), featuring design patterns and gameplay mechanics conventionalized under a specific genre label -- 2D side-scrolling platformers, of which Super Mario Bros. (SMB; Nintendo Creative Department, 1985) may be considered the prime example. The game consisted of three levels, replete with spatial obstacles and AI enemies, which the participants needed to navigate and complete utilizing basic movement mechanics (walking, running, jumping) whilst collecting pickups in the form of coins.

Figure 1. The control game. Click image to enlarge.

The second prototype served as the experimental game (Figure 2), and was developed with the goal of testing a deviation from the conventional challenges found in platform games. The experimental game retained the visual elements, assets, and basic navigational challenges of the control game, but with different platform layout and enemy placement due to the removal of one particular movement mechanic -- jumping. Consequently, the levels (four in total) were laid out in such a way that the player needed to use ladders and entice enemies to move so that they could circumvent them and make progress.

Figure 2. The experimental game. Click image to enlarge.

The prototypes were developed to create two rudimentary gaming experiences that differed as little as possible, and only on the level of gameplay mechanics (i.e., actions available for the player to perform) and level design (i.e., the layout and positioning of assets, pickups, and enemies). The decision to work with 2D side-scrolling platformer conventions was made for several reasons. This category of digital games has been perennially popular: from the original SMB to more modern games such as VVVVVV (Cavanagh, 2010) and Super Meat Boy (Team Meat, 2010). Games belonging to this category have been played by generations of players and represent important influences on our collective understanding of digital games and gaming. Furthermore, 2D side-scrolling platformers are characterized by a set of (specifically mechanical and level) design conventions, which have remained relatively stable (though also subject to experimentation) and present in most examples of games belonging to this genre since SMB; such as the existence of a jump mechanic or some other form of vertical movement.

The prototype games were developed in the Unity3D game engine, utilizing the Corgi Engine pack, consisting of custom character and AI controllers, camera and inventory systems, as well as rudimentary visual assets. Visually, both games had a minimalist, geometric aesthetic, and featured monochromatic assets and simple backgrounds in shades of pastel colors. These aesthetic choices were made with the aim of minimizing the number and range of visual components, thus leading to a greater focus of the participants on the gameplay activity in the two games. Prior to their use in the study, both prototype games were tested for usability to ensure no bugs or glitches, which could affect the participants’ gameplay experiences.

Qualitative research

The exploratory study adopted a qualitative research design. According to Creswell, qualitative research is recommended for inductive theory building, as well as for non-reductionist analysis of complex phenomena (2009, p. 4). This view is further echoed by Hennink and colleagues, who recommend qualitative research approaches for developing contextualized understandings of how and why certain processes happen and are experienced by those taking part in them (Hennink et al., 2020). Since the goal of the study was to construct theory, qualitative data collection based on observations and interviews was the most appropriate approach. Further reasons for adopting a qualitative approach included the preliminary, exploratory character of the research, as well as scarcity of prior empirical data on habitus as deployed during gameplay. Lastly, the specific topic -- the functioning of habitus in understanding and navigating small design differences -- was deemed to be subject-dependent and difficult to pinpoint a priori to a single factor or set of factors, requiring flexible data collection instruments and procedures, including more time spent with each individual participant (and the data they provided) in order to capture said complexity in greater detail.

Grounded theory

The study employed grounded theory as its method of theory development (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). This approach to theory construction is predicated on empirical data: though grounded theory does not preclude a researcher from bringing in a specific theoretical frame into the research, it argues that theory should emerge from the iterative processes of data analysis. Grounded theory advocates for the use of multiple methods of data collection to ensure validity of results, and an iterative process of data analysis through three successive stages of data coding (open -- axial -- selective). Both data collection and analysis methods will be further described in their individual sections later in the paper.

Grounded theory was utilized due to its flexibility as a research approach. It allowed for freedom in the choice of data collection and analysis methods, as well as for the crucial integration of game design practice as a research method with an empirical, laboratory playtesting setup. As described earlier when discussing prototype design, this integration was seen as important for exploring the research topic of the study.

Participant recruitment

The number of participants involved in the study was kept relatively small due to its qualitative and exploratory character. Eight participants in total (four female, three male, one non-binary, ages 21-29) took part, and were recruited using the method of purposive sampling (Maxwell, 1997; Teddlie & Yu, 2007). This method was used in order to secure two specific groups of participants: those with an overall high and varied level of digital gaming experience, including 2D side-scrolling platformer games (from here on out referred to as Group One), and those who had limited experience with platformer games and otherwise rarely played digital games in general (from here on out referred to as Group Two). To that end, the first group was comprised of four bachelor students of game design: Mark, Wendy, Ernest, and Logan [1]. They were first to be recruited, and were purposefully chosen for their high degree of familiarity and experience with different games and design conventions; both as players and as game-makers, as well as with elements of gaming culture. The second group was comprised of four infrequent game players: Nick, Eve, Amy, and Julia. They mostly stuck to a handful of game genres or played games on rare occasions.

All of the participants were volunteers, taking part in the study for no compensation, monetary or otherwise, and had no prior knowledge of the research project. All of them also consented, in writing and verbally during the interview, to having the data they provided be used for research purposes. The study design and methodology were also approved by the ethics committee at the researcher’s institution.

Data collection instruments

Three data collection instruments were used in the study: a profiling questionnaire, gameplay observation and recording, and a post-play-session, semi-structured interview.

The profiling questionnaire was created in Google Forms. It employed three question formats: Likert scale questions, checkbox questions, and open-ended questions. Questions were divided into multiple groups, covering topics such as gaming habits, player familiarity with input methods, hardware systems, game genres, game titles, player attitudes (i.e., preferences) towards these, as well as their self-perceived degree of competence with different gaming titles. The aim of the questionnaire was to cast light on the participants’ previous, individual experiences with games. For this reason, the questionnaire featured purposefully broad questions and avoided gaming jargon so as to enable the participants to describe in their own words how they understand and relate to digital games. This was also the reason why open-ended questions featured as the most frequent question type.

The participants’ game playing was logged as audiovisual recordings of their physical selves in tandem with video capture of their in-game activities. The recordings were captured using the camera and microphone of the laptop participants used to play the two game prototypes, with the final feed consisting of both gameplay footage and footage of the participants during play. The participants were told they were free to comment during their gameplay, but there was no requirement for them to do so if they instead wished to focus on the gameplay. During the sessions, the researcher also took observational notes about the participants’ play, highlighting points of interest (e.g., a repeated error, ease of navigation in certain areas, etc.), which would later be referenced in the interview when need be.

Lastly, the participants took part in a post-play-session semi-structured interview, conducted immediately after their play session. The interview was used to gain insight into their experiences with the game prototypes, as well as ascertain how they perceived the similarities and/or differences between the two. The interviews also enabled the participants to provide more information about specific moments that the researcher observed and noted during their play sessions. In a similar manner to the questionnaire, interview questions were framed in such a way as to avoid genre labels and suggestions of categorizations. The aim was to have a neutral, open tone, allowing for more freedom in generating responses and describing the differences between the two games. In situations when participants used a particular genre label themselves, that label was then also part of the interviewer’s vocabulary, at times featuring in subsequent questions. After each of these sessions, the interviews were transcribed into text.

Experimental procedure

Each participant took part in the study individually, leading to eight separate testing sessions. Upon arrival to the university game lab, where the study took place, the participants were presented with a general overview of the activities. Afterwards, they were asked to fill out the questionnaire, during which they were able to ask the researcher about specific points, unclear phrasings, or other difficulties. Following the questionnaire, each of the participants played the games (the order of which was randomized) on a laptop and utilizing the Xbox 360 wireless controller. All of the participants in the study had prior history of controller use, though they were not directly informed about the controls in the games they played in the study. The participants were given a soft time limit of around ten minutes for each of the games, and encouraged to play as they would under normal conditions. The last stage of the test consisted of the semi-structured interview with the researcher, which was recorded using a voice recorder.

Data analysis

Interview transcripts were analyzed using the three-level process of coding characteristic of grounded theory. The available data was imported into the MAXQDA 2018 software package (used to ease and speed up analysis) and then initially examined, which resulted in the extrapolation of a number of concepts related to game categories, perception and classification, prior gaming experiences and game associations, overall impressions, and more. The concepts developed through this open coding were later grouped and refined in a second round of axial coding for easier examination and cross-reference. The final code system included 25 different codes, grouped under specific headings, and a total of 260 coded interview segments across the eight transcripts.

Interview data formed the focal point of analysis, complemented by gameplay logs of the participants’ performances, which were reviewed multiple times and considered in tandem with the interview responses. The questionnaire data was mostly used for providing background information on the participants, and is referenced in the results when needed.

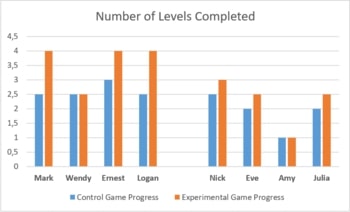

Results

As illustrated in Table 1, all eight participants successfully completed at least one level in each of the games. The degree of progress varied from player to player: overall, Group One participants did better in both the control and the experimental games, with all four players nearly completing all three levels of the former before their time was out, and three out of four completing all four levels of the latter. In contrast, only one player in Group Two, Nick -- who also had the most overall gaming experience in the group -- managed to complete the experimental game and reach the final level in the control game.

Table 1. Number of levels completed by the study participants. Half-values indicate partial completion of the subsequent level -- i.e., the play session ending before the player had a chance to finish the level. Click image to enlarge.

In general, the control game elicited a clear goal-oriented playstyle from most of the participants, in particular from Mark, Ernest, and Nick, the three players who also frequently made mistakes due to their fast playing style. Amy and Julia, on the other hand, played more tentatively and methodically, with their mistakes during gameplay arising from a seeming lack of experience in navigating virtual spaces and jumping between platforms. Similar playstyles were observed in case of the experimental game, with Group One and Nick displaying quicker reflexes and taking less time to figure out the challenges on each level, while Eve, Amy, and Julia generally took a slower, more careful approach.

In isolation, these metrics are perhaps unsurprising. It seems logical that the more experienced group would complete more levels than the other group -- comprised of infrequent players of the platformer genre -- as well as that greater gaming experience overall in members of either group seems correlated with better performance. However, level completion data and playstyle differences only tell one side of the story of how these two groups related to these two games. Further findings and observations are presented below, for each of the two groups.

Group One: The game design students

The four participants in Group One exhibited similarities when it came to interpreting, playing, and classifying the two game prototypes. One notable example was in their use of terminology and methods of classification: all four of them identified the control game quickly, and in the same manner, as a (side-scrolling) platformer. Some variants of the label were observed (such as “platform side-scroller” or simply “platform game”), but the consensus seemed to be that the game in question is a fairly standard, prototypical case of a platformer. When asked to elaborate on their reason behind the use of this label, participants in this group stated that they did so due to the format of spatial navigation (left to right), and, in particular, the jump mechanic present in the game. Several of the participants also noted strong similarities between the control game and other platforming games. The most common associative link was with SMB, a game whose first level (World 1-1) directly inspired the first level in the control game, but there was also mention of games which also feature platforming elements and a jumping mechanic, like Alice: Madness Returns (Spicy Horse, 2011), Crash Bandicoot (Naughty Dog, 1996), or Kao the Kangaroo (X-Ray Interactive, 2000). On their own, these links were perhaps not quite surprising: after all, all four participants in this group mentioned having playing many platformers in the past, and, as game design students, were familiar with a landmark game such as SMB. More interesting was the degree to which these associative links influenced the players’ performance and gameplay activities by placing them in a specific state of mind and method of behaving derived from their experiences with SMB. In some cases, as illustrated by Mark’s comment below, this influence resulted in incorrect inferences about the control game and subsequent mistakes during play:

Mark: You have your jump and you’re moving pretty quickly and then there’s enemies […] I guess I’m thinking of Mario very quickly when it’s like that. Even the first two platforms and the first enemy were almost placed, like, the very first one in the first level of Mario. Which is also why I tried to jump on it, but apparently I failed and didn’t… Like, I hit it slightly on the side and I didn’t think I could, actually. Yeah, and it just felt, like, very, very familiar, and that’s, I guess, also why I didn’t check for other buttons, because I was like “Oh yeah, this is Mario, I’m just gonna move around and jump.” Logan: The moment I got in and found out “OK, this is how I control, this is how I jump, there is a little guy coming towards me” -- I was thinking: Mario, immediately. And I just went by Mario rules. […] I can definitely see how, because of other games I have in my library of games I’ve played, I went by another game that was very identical in its way of playing.

The experimental game also garnered the same consistent and quick categorization in the case of Group One, with all participants using either the term “puzzle game” or “puzzle platformer” to describe it. When asked to explain their reasoning, the participants mentioned that the experimental game had mechanical twists on the genre -- namely, the absence of the jumping mechanic -- which, when coupled with alterations in level design, required a different kind of thinking to complete the levels.

Wendy: This one, I would say it was more of a puzzle game, because you didn’t have, like, this jump thing that you have on the platformers, that you jump from one platform to another. There, you need actually to think how to defeat the opponents, by just dragging them down from the platforms. So I feel like it was more of a puzzle game than a platformer. Logan: The feel to the game was also different, because I went in having this feeling of “This is basically the same game, cause it’s all the same elements” […] But when I figured out that “Oh, you cannot jump!” -- then my brain just very fast went “Oh, this is [a] puzzle” (laughs). So I started doing puzzle game and puzzle thinking instead of action game, I-need-to-get-from-point-A-to-B-not-getting-killed…

After describing and classifying the games individually, the participants were asked to categorically compare the two games. The question was purposefully open-ended, and no genre designators were provided to the players unless they first mentioned some themselves. They were simply asked “Would you say that these two games are of the same kind or type?” This question elicited a range of responses; in general, the participants in both groups took longer to answer it, and gave much more complex answers, than when asked about the individual games. Nevertheless, some commonalities could be noticed. In the case of Group One, all four participants discriminated between the games to a much higher degree, classifying them as different types of games due to differences in mechanics and challenge types, despite remarking on their visual similarities. At times when a genre label of “platformer” was specifically mentioned, the participants were asked whether one of the games was a more prototypical example of the category than the other. In such situations, all of the participants in the group confirmed that the jump mechanic made the control game seem more prototypical, e.g.:

Researcher: Which game would you say is more of a platformer? Ernest: The second one. R: Okay. Any reason for that, again? You may have mentioned it in the past, but… E: Because it follows more closely the conventional platformer. R: In what way? E: Jumping, primarily.

All four participants in Group One also expressed greater preference for the experimental game. Among the reasons cited were its insistence on logical thinking, its twist on platformer conventions, as well as the greater feeling of accomplishment experienced during play. In contrast, the consensus around the control game was that it represented a short, fun, but ultimately highly derivative gameplay experience of the kind they had encountered many times before. As such, the participants in Group One did not consider it a game which they would play of their own accord in their everyday lives.

Group Two: The infrequent players

In contrast to Group One, participants in Group Two were not unanimous in how they perceived and described the control game, generally giving longer, more discursive and diverse answers. Eve, who in the questionnaire expressed having some familiarity and proficiency with platformers, did use the term “platform” to describe the game, associating, specifically, the form of movement and the presence of platforms with the label. The three other participants offered such labels as “mechanical game,” “older game,” “running game,” “typical game,” and, curiously, “adventure game” to describe the control game. Nick and Amy also had associations to SMB, specifically in terms of gameplay, although both professed having last played such games a long time ago. When Nick was pressed for a genre label to describe SMB., he used the terms “adventure game” and “running game,” the same terms he had used earlier to classify the control game.

When it came to identifying the experimental game, participants in Group Two gave much more elaborate answers than Group One and mostly applied the same labels as those used to describe the first game -- namely, terms such as “running game” and “adventure game,” among others. A notable exception was Julia, by far the least experienced with digital games and gaming culture, who made the following observation in which she noted the differences between the two games:

Julia: The [control game] is a mechanical game. But the second one is not. It requires you to use your brain a lot, rather than the first one, where you have to be quick and use buttons. In the second one, you have to use logic.

In contrast to Group One, three out of four members of Group Two answered that they thought the two games were essentially similar, or of the same kind. In explaining their reasoning, they cited not only the visual or asset similarities, but also those on the level of the gameplay experience, which did not play nearly as important a role as for Group One:

Nick: Yeah, I would say so, yeah […] Because the basic elements are the same. I don’t know; the graphics and the gameplay don’t change dramatically. One is just kind of simpler, that’s it. Eve: … Yes, I guess so. As I told you, it could be the same game, but with the second one could be just the part when you level up a bit […] I associate certain genres to games and even though a person doesn’t play them… I think even more if a person hasn’t played games before, these would seem similar […] Both are platforms, I guess. Amy: Yes, same type […] I mean, I think they are of the same type, same category, but I think that, for the second game, you need to think a little bit more, I don’t know.

As stated earlier, the outlier in Group Two was Julia, who strongly insisted that the two games were of a different kind. When asked for a reason why, she stated that she perceived the control game as a typical game she played when she was younger (which, judging by her questionnaire response, was likely SMB), and the experimental game as a more complex, unorthodox kind of game that was unlike anything she had played before.

In terms of preferences, Amy and Julia stated that they preferred the experimental game, mostly due to its perceived complexity and innovation, as well as its focus on logical thinking. Nick and Eve, meanwhile, opted for the control, claiming they enjoyed the greater range of mechanical complexity, which fostered their desire to replay the game.

Discussion: Ludic habitus & generic subfields of practice

How can we best conceptualize the differences between these two groups of players? In order to answer this question, we turn to practice theory. In most fundamental terms, prolonged practical engagement with digital games and the cultures which surround results in the development of a game-specific version of Bourdieu’s notion of habitus -- in other words, in ludic habitus. In the context of digital games, and with a focus on gameplay activities, we can understand ludic habitus as acquired patterns of perception, appreciation, and action built up over the course of prolonged experience with games and gaming culture, and subsequently structuring our practical gameplay engagements. Ludic habitus represents particular, practically acquired ways of perceiving, interpreting, appreciating, and performing tied to the domain of games. In simple terms, it is one’s own personalized way of understanding and relating to games and, more broadly, gaming culture.

Because the corresponding field involved in its creation (that of digital games) contains an incredibly diverse set of designed artefacts, it is reasonable to think that ludic habitus can take on many forms. However, digital games are characterized by substrata of operational and experiential similarities in the form of conventionalized hardware and software implementations and solutions, which are basic and necessary prerequisites for category formation. From this perspective, genre groupings of digital games can be said to constitute practical categories -- conventionalized, often overlapping genericsubfields of practice, subsumed under the more general practical umbrella of the digital gaming field. Our conceptualization and categorization of digital games and gaming develop on the basis of personal experience with these subfields and the games and subcultures which belong to them. In turn, possessing ludic habitus familiar with a particular generic subfield and its design conventions -- for example, those characterizing platforming games -- works to facilitate gameplay performance and recognition of said patterns in games belonging to the same subfield.

Participants in Group One -- seasoned players who were also students of game design -- turned out to possess quite similar ludic habitus, familiar with the established generic subfield of platformer games. This is evidenced by similarities in their interpretation, labeling, and to an extent gameplay prowess in both games. Familiar with the conventions of 2D side-scrolling platformers both as players and as designers, participants in Group One distinguished more strongly between the two prototypes in experiential terms, often assigning them different genre labels when prompted (typical/conventional platformer vs. puzzle platformer) and strongly correlating the jumping mechanic with the platformer genre. This correlation was enough for all four members of Group One to describe the experimental game as a departure from their idea of a traditional platformer experience. The platformer domain knowledge that Group One possessed as part of their ludic habitus came in handy during testing, insofar as it enabled them to quickly interpret the mechanics and spatial layout of the two games, and then infer and implement particular methods of play which they previously acquired and refined in encounters with similar games. Lastly, these players also displayed the same pattern of preference, with all of them stating they appreciated the experimental game more because they saw it as somewhat innovative and therefore more interesting than the control game.

Conversely, Group Two featured participants whose ludic habitus were more rudimentary, varied, and restricted to other game types. Due to their limited practical experience with games belonging to the platformer genre and unfamiliarity with the relevant discourse and terminology, they did not possess a firm concept of a platformer game, or associated only the properties recurring in the two games (like the presence of platforms) with the genre. In a notable departure from Group One, the members of Group Two, for the most part, saw the two games as essentiallysimilar, even when it came to the kind of gameplay experience the games provided. With the exception of Julia (who, as noted before, distinguished between the games quite strongly on the level of skills required by them), the less strict understanding of platformers as a delineated game category enabled most participants in Group Two to focus more on the similarities between the two games, rather than to discriminate between them on the basis of their differences.

On the level of performance, the overall greater practical familiarity with games of Group One participants did translate into better results, in both game prototypes, compared to Group Two. However, there were moments when previous experience with similar design patterns and genre gameplay conventions seemed to hinder, rather than aid, performance. One example of this was Mark, who, as was mentioned earlier, attributed his initial difficulties when playing the first level of the control game, modeled on World 1-1 in SMB to his overreliance on patterns of action established by the latter game. In these cases, knowledge and skills linked to a particular game led to misinterpretations and errors when playing a game which contained similar design elements, essentially forcing the players to stop and adapt their play styles. While these challenges were temporary and overall minor for the players who experienced them, they still showcase how one’s ludic habitus, emerging from experience with specific games or gaming conventions that characterize a specific generic subfields of gaming practice, influences how we perceive and approach similarly designed games. This influence is, counterintuitively, not always positive and beneficial to performance.

Limitations

The present research took the form of an exploratory study and offered a preliminary understanding of ludic habitus and generic subfields of practice. As such, the research comes with some limitations which need to be made explicit. From a methodological standpoint, the study relied on purposive sampling to recruit participants. While this form of sampling did result in two groups of players which differed in terms of their level of gaming experience, one of these groups was comprised exclusively of players who are also game design practitioners, who potentially approach games in a more outwardly analytical fashion than other experienced players. Similarly, the study relied on qualitative methodology; while this approach is commonly used for theory building, more research with different populations of players is needed to further elaborate on the theoretical concepts presented here. Ideally, such research would expand on the number and types of participants, potentially incorporating quantitative data as part of a mixed-methods approach already advocated as a paradigm in social research (see e.g., Denscombe, 2008).

It is also important to reflect on the absence of consideration for sociocultural aspects traditionally associated with the notion of habitus. In this study, ludic habitus was viewed in a limited and specific fashion; i.e., purely in terms of one’s interactions with (a specific category of) digital game artefacts. Such an approach has not directly addressed the interplay between one’s cultural and social background and experiences with said practice. The reason for this was primarily pragmatic and related to issues of scope and the study’s focus on habitus deployment in the act of gaming practice. In light of limited work to act as precedent in game studies, the specific perspective on ludic habitus offered in this study was necessary as an early, focused step into further empirical investigations of this concept, which would take more general sociocultural matters into account.

Conclusion

The research presented in this paper was conducted to more closely account for the manifestation of the personal attributes which govern how players play, understand, and relate to games. As an initial step in this exploration, the research adopted the perspective of Bourdieusian practice theory, and featured an exploratory empirical study conducted with the aim of establishing the concepts of ludic habitus and generic subfields of practice within the domain of digital gaming. In tandem, these two concepts help us to better discuss and understand how individual player attributes (such as preference, knowledge, and skills) converge and present in the practical act of playing digital games in response to specific game design elements of a given game.

How players interpret a particular gaming situation, and how they act in it, depends on their ludic habitus: their acquired patterns of perception, appreciation, and action, which are tied to the broader field of digital games. As evidenced by the findings of the study, these patterns may be specialized for a given subdomain of games and gaming that features conventionalized design configurations -- a generic subfield of practice, such as the genre of platforming games. Ludic habitus familiar with a generic subfield of practice functions as an interpretative, evaluative, and performative framework when encountering games which register as belonging to that subfield. This familiarization seems to result in a greater degree of discrimination on the basis of conventional features, but also in more rigid schemas of classification and occasional errors in performance.

The analytical strength of the concept of ludic habitus lies in its holism. It represents a novel, complex perspective on players, one which takes into account the various attributes that characterize our experience with games and gaming. It is meant to serve as an alternative to the more individualized examinations of differences between players, such as typological classifications on the basis of a single parameter like motivation, preference, or ability. While the conducted exploratory study has illustrated how we can use ludic habitus to frame and examine the practical act of gameplay, more empirical research is needed to further elaborate the aspects of ludic habitus not covered in the study -- such as socio-cultural background. As part of a larger research project, a follow-up study that will address these considerations to a greater degree is being planned, and will investigate how specific deployments of ludic habitus (e.g., methods of playing or understanding) are triggered by particular game design solutions within a given subfield of practice. The ultimate goal of this larger research project is to create a detailed Bourdieusian model of digital gaming as a form of human practice, and, in doing so, contribute towards a richer, more nuanced understanding of the relationship between players and digital games.

Endnotes

[1] The names of the participants have been altered for the sake of anonymity.

References

Apperley, T., & Walsh, C. (2012). What digital games and literacy have in common: a heuristic for understanding pupils' gaming literacy. Literacy, 46(3), 115-122.

Barr, P. (2008). Video game values: Play as human-computer interaction [Doctoral dissertation, Victoria University of Wellington]. Te Puna Rangahau Research Archive. http://hdl.handle.net/10063/371

Bartle, R. (1996). Hearts, clubs, diamonds, spades: Players who suit MUDs. Journal of MUD research, 1(1), 19.

Bourdieu, P. (1990). In other words: Essays towards a reflexive sociology. Stanford University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (2013). Outline of a theory of practice (R. Nice, Trans.). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1972)

Bourdieu, P. (2014). The logic of practice (R. Nice, Trans.). Stanford University Press. (Original work published 1980)

Calleja, G. (2011). In-Game: From Immersion to Incorporation. MIT Press.

Carr, D. (2005). Contexts, gaming pleasures, and gendered preferences. Simulation & Gaming, 36(4), 464-482.

Consalvo, M. (2007). Cheating: Gaining Advantage in Videogames. MIT Press.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Crick, T. (2011). The game body: Toward a phenomenology of contemporary video gaming. Games and Culture, 6(3), 259-269.

De Castell, S., Jenson, J., & Thumlert, K. (2014). From simulation to imitation: Controllers, corporeality, and mimetic play. Simulation & Gaming, 45(3), 332-355.

De Schutter, B., & Vanden Abeele, V. (2010, September). Designing meaningful play within the psycho-social context of older adults. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Fun and Games (pp. 84-93). ACM.

Denscombe, M. (2008). Communities of Practice: A Research Paradigm for the Mixed Methods Approach. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 2(3), 270-283.

Dietrich, D. R. (2013). Avatars of whiteness: Racial expression in video game characters. Sociological Inquiry, 83(1), 82-105.

Dovey, J., & Kennedy, H. (2006). Game cultures: Computer games as new media. McGraw-Hill Education.

Drachen, A., Canossa, A., & Yannakakis, G. N. (2009, September). Player modeling using self-organization in Tomb Raider: Underworld. In 2009 IEEE symposium on computational intelligence and games (pp. 1-8). IEEE.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of management journal, 50(1), 25-32.

Farrow, R., & Iacovides, I. (2014). Gaming and the limits of digital embodiment. Philosophy & Technology, 27(2), 221-233.

Galloway, A. R. (2006). Gaming: Essays on algorithmic culture. University of Minnesota Press.

Giddings, S., & Kennedy, H. W. (2010). “Incremental speed increases excitement”: bodies, space, movement, and televisual change. Television & New Media, 11(3), 163-179.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. De Gruyter.

Gray, K. L. (2014). Race, gender, and deviance in Xbox live: Theoretical perspectives from the virtual margins. Routledge.

Hanington, B. M., & Martin, B. (2012). Universal methods of design: 125 ways to research complex problems, develop innovative ideas, and design effective solutions. Rockport Publishers.

Haraway, D. (1991). A Cyborg Manifesto: Science Technology and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century. In Haraway, D., Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. Free Association Books.

Hennink, M., Hutter, I., & Bailey, A. (2020). Qualitative research methods. Sage.

Kallio, K. P., Mäyrä, F., & Kaipainen, K. (2011). At least nine ways to play: Approaching gamer mentalities. Games and Culture, 6(4), 327-353.

Keogh, B. (2018). A play of bodies: How we perceive videogames. MIT Press.

Kirkpatrick, G. (2015). The formation of gaming culture: UK gaming magazines, 1981-1995. Palgrave Macmillan.

Lahti, M. (2013). As we become machines: Corporealized pleasures in video games. In B. Perron & M. J. P. Wolf (Eds.) The video game theory reader (pp. 179-192). Routledge.

Lizardo, O. (2004). The cognitive origins of Bourdieu's habitus. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 34(4), 375-401.

Malaby, T. M. (2007). Beyond play: A new approach to games. Games and culture, 2(2), 95-113.

Maxwell, J. (1997). Designing a qualitative study. In L. Bickman & D. J. Rog (Eds.) Handbook of applied social research methods (pp. 69-100). Sage.

McNeish, W., & De Paoli, S. (2016). Developing the Developers: Education, Creativity and the Gaming Habitus. In Proceedings of the 1st International Joint Conference of DiGRA and FDG.

Nardi, B. (2010). My life as a night elf priest: An anthropological account of World of Warcraft. University of Michigan Press.

Naughty Dog. (1996). Crash Bandicoot [PlayStation]. Digital game published by Sony Computer Entertainment.

Nicolini, D. (2017). Practice theory as a package of theory, method and vocabulary: Affordances and limitations. In Methodological reflections on practice oriented theories (pp. 19-34). Springer, Cham.

Nintendo Creative Department. (1985). Super Mario Bros. [Nintendo Entertainment System]. Digital game directed by Shigeru Miyamoto, published by Nintendo.

Ortner, S. B. (1984). Theory in Anthropology since the Sixties. Comparative studies in society and history, 26(1), 126-166.

Shaw, A. (2011). He could be a bunny rabbit for all I care”: Exploring identification in digital games. In Proceedings of DiGRA 2011 Conference: Think Design Play.

Spicy Horse. (2011). Alice: Madness Returns [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by American McGee, published by Electronic Arts.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage.

Taylor, T. L. (2009). The assemblage of play. Games and culture, 4(4), 331-339.

Team Meat. (2010). Super Meat Boy [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game designed by Edmund McMillen and Tommy Refenes, published by Team Meat.

Teddlie, C., & Yu, F. (2007). Mixed methods sampling: A typology with examples. Journal of mixed methods research, 1(1), 77-100.

Terry Cavanagh. (2010). VVVVVV [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game designed by Terry Cavanagh, published by Nicalis, Inc.

Tomas, D. (2000). The Technophilic Body: On Technicity in William Gibson’s Cyborg Culture. In Bell, D. and Kennedy, B. (Eds.) The Cybercultures Reader (pp. 175-89). Routledge.

Wacquant, L. (2011). Habitus as topic and tool: Reflections on becoming a prizefighter. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 8(1), 81-92.

X-Ray Interactive. (2000). Kao the Kangaroo [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game published by Titus Interactive.

Yee, N. (2006). The demographics, motivations, and derived experiences of users of massively multi-user online graphical environments. Presence: Teleoperators and virtual environments, 15(3), 309-329.

Zackariasson, P., Wåhlin, N., & Wilson, T. L. (2010). Virtual identities and market segmentation in marketing in and through massively multiplayer online games (MMOGs). Services Marketing Quarterly, 31(3), 275-295.

Zhu, F. (2018). Computer gameplay and the aesthetic practices of the self: Game studies and the late work of Michel Foucault. Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association, 3(3).