“Deathloop”: the Meta(modern) Immersive Simulation Game

by Hans-Joachim BackeAbstract

"Deathloop" (Arkane Studios, 2021) was upon its release critiqued by both professional reviewers and fans for not adhering to the genre conventions of “immersive simulation games” found in all previous games of its developer, Arkane Studios (i.e., an emphasis on choices and consequences, divergent play-styles and emergent gameplay resulting from interconnected systems). The article argues that Deathloop embodies the aesthetic sensibilities of metamodernism (Vermeulen and van den Akker, 2010), which are a continuation and reaction to modernist and postmodernist aesthetics. Metamodernism emphasizes indeterminacy, truthfulness and hopefulness, striving for more ethical and less cynical art in all media. The article analyzes the construction principles of the genre of immersive sim, and how Deathloop departs from its conventions, before introducing metamodernism as a theoretical backdrop for a hermeneutic analysis. The analysis correlates game structure, mechanics and narrative of Deathloop to illustrate how the game overcomes both the genre restrictions of immersive sims and the modern and postmodern sensibilities found in earlier games of a similar style.

Keywords: Genre, criticism, FPS, RPG, immersive sim, metamodernism, metareferentiality

Introduction

"Deathloop" (Arkane Studios, 2021) was one of the most talked about digital games of 2021 -- yet not in exclusively positive ways. An enormous success with critics and recipient of several game of the year awards, the game was met with mixed reactions from fans and (at best) moderate sales success (Tassi, 2021). The game is quite unusual in both its gameplay, with first-person shooter mechanics in a puzzle-like structure, and in terms of representation, featuring a Black man and a Black woman as its only playable characters. Much of the debate about the game can be attributed to its defiance of genre conventions. Prima facie, it is undoubtedly an FPS, yet within this by-now venerable and highly diversified genre, it stands out not by adding to the existing genre formula, but by removing or withholding elements. Compared with other contemporary shooters, it has fewer weapons, fewer multiplayer options and a shorter campaign. Compared with its immediate predecessors -- developer Arkane Studio’s previous games Dishonored 2 (Arkane Studios, 2016) and Prey (Arkane Studios, 2017) -- it appears as simplified in every way, vastly cutting back on the studio’s trademark non-lethal, stealthy, diverse gameplay. Arkane’s games are generally characterized as belonging to the immersive simulation game genre, yet both professional reviewers and fans have debated whether Deathloop can be considered an “immersive sim.” As a player review on Steam puts it: “there's practically nothing new that Deathloop has to offer if you're a fan of Arkane. I would even argue that it takes a lot of familiar Arkane-features away from you” (Seselj, 2022).

Leaving for the moment aside the question of how "Deathloop" adheres to the conventions of an ill-defined genre, there can be no doubt that it is a very high concept game. Its central design principle is, in the words of game director Dinga Bakaba, a “murder puzzle,” like “Cluedo in reverse” (van Aken, 2021). In the single-player campaign, the player controls Colt Vahn, a former military pilot who wakes up on the beach of a subarctic island without a clear memory of his past. Colt finds out that the island, Blackreef, has been settled by a group of visitors who call themselves “Eternalists,” led by a group of eight self-proclaimed “Visionaries.” Blackreef possesses unique properties that the Visionaries harness to control time, promising the Eternalists a carefree, playful and above all eternal life on the island. But the experiment has gone wrong, and everybody is trapped in the perpetually repeating first day on the island without control of the timeloop, unable to ever stop it.

Colt learns that he used to belong to the Eternalists, and that only two of them, he and Archivist Juliana Blake, are aware of the nature of the timeloop and retain their memory of previous iterations of the day. Juliana wants to preserve the timeloop, not the least for fear of what returning to reality might mean after dozens, if not hundreds of years in the loop. Colt, however, wants to break free from the loop, and the only way to do that is to kill all eight other Visionaries. This makes Juliana both Colt’s adversary and his confidante, and the game builds towards their final confrontation and the decision about the future of the timeloop. Before that can happen, Colt needs to locate and kill the Visionaries within the same day; all of whom are spread across the island, often protected by the Eternalists while locked away in their labs and manors.

Gameplay revolves around exploration of the environment, understanding the mechanics of time on Blackreef, and ultimately preparing one perfect day on which all Visionaries can be killed. The central shooter mechanics are enriched by a system of modular weapon modifications and quasi-magical character abilities such as short-term invisibility and short-range teleportation, as well as many interconnected simulation systems that allow the player to set traps or use the opponents’ defenses against them. Instead of manual saving, the game gives the player three “lives” per mission, and instead of a multiplayer mode there is an invasion mechanic; mixing venerable (or, depending on one’s taste, old-fashioned) and trendy mechanics. And despite the superficial importance of time for the game, time-manipulation is kept simple and out of the player’s hands.

How do we make sense of a game such as "Deathloop" at the time of its launch, without the benefit of hindsight and a stable historical context to situate it in? In this article, I will propose a reading of Deathloop before the background of metamodernist aesthetic theory. As I will show in a close reading of the game in the second half of this article, Arkane Studios tap into contemporary aesthetic sensibilities of resistance, sincerity, reconstruction and ethics, which have been identified as typical of metamodernism (Vermeulen & van den Akker, 2010). This theoretical context is not meant to suggest an unambiguous periodization, but to serve as a lens for a hermeneutic analysis approach. As will be discussed below, postmodern aesthetic models and their successors aim to identify sensibilities, mindsets and creative contexts before which art can be interpreted. They are hermeneutic lenses that have a tentative relationship with periods of time, not proclamations of dominant or exclusive aesthetics that govern the production of art of one or several decades.

The article takes its departure from the confusion of players and reviewers about Deathloop’s relationship to the genre of immersive sim. The genre (and game genre theory more generally) are introduced and critiqued, before outlining theories of the postmodern and metamodern as they pertain to digital games. These frames of reference are then used to discuss "Deathloop"’s more confounding features and less obvious metaphors. Two dimensions of the game will be highlighted in particular: first, how the game constructs equivalencies of ludic and narrative structures, creating a world that not only gives meaning to illogical game conventions like respawning, but reflects on them; and second, how the characters of the game and the construction of its ending form a subtle metaphor for the player’s relationship to the game. In sum, the analysis will show that "Deathloop" creates ludonarrative harmony, as opposed to dissonance (Hocking, 2009), between its narrative, its mechanics and the overall game structure, and in the course of this does not strive for a wholesale abandonment or overcoming of its genre legacy, but a consequential refinement, which metamodernism helps foreground and contextualize.

Immersive Simulation and the Challenge of Game Genres

To a casual observer, immersive sims often appear as First Person Shooters -- and not only to them. Carl Therrien’s etymology of the term First Person Shooter mentions System Shock (Looking Glass, 1994) as one of the historically important and influential examples (Therrien, 2015), Andreas Gregersen calls Bioshock (2K Boston, 2007) a shooter with leveling mechanics and a “lock-hacking game as a small puzzlegame on its own” (Gregersen, 2014, p. 167) and Dominic Arsenault describes Deus Ex (Ion Storm 2000) as “not a run-of-the-mill FPS but a complex RPG/FPS hybrid” (Arsenault, 2009, p. 167). That three of the main examples for immersive sims are considered First Person Shooters of a kind makes sense, but so does considering them hybrids (Call, 2012, 138) or a genre of their own (Pinchbeck 2013, 154) [1].

It is well documented that “first-person shooter” is a term that only gains traction around 1998 -- maybe not accidentally around the time of Half-Life’s (Valve, 1998) publication (Arsenault, 2009; Therrien, 2015). Until then, the more common category was “Doom clone.” This puts both System Shock’s early innovation in a different light -- demonstrating what an FPS/RPG hybrid could be at a time when the genre was still conceived of as epigonal of the (assumed) Ur-game of Doom (id Software, 1993) -- as well as Deus Ex’s and System Shock 2s (Irrational Games and Looking Glass Studios, 1999), when FPS had just become a recognized label. The historical distance of 20 years shows quite clearly that the inception of the “different FPS” in System Shock as well as its perfection in System Shock 2 and Deus Ex came at pivotal moments in the genre history of the FPS. By the 2020s, the situation is almost completely reversed: Now, simple, straightforward shooters are the exception, with even the new entries in the foundational series offering distinct, complex genre blends, be it the inclusion of stealth in Wolfenstein: The New Order (Machine Games, 2014) or puzzle platforming in Doom Eternal (id Software 2020). This has made the genre of immersive sim even more tenuous in the 2010s than it was before. The games still being produced become increasingly more complex and self-reflexive (Backe, 2018). At the same time, Arkane Studios co-founder Raphaël Colantonio, one of the innovators of the genre, declared that immersive sims had become obsolete because their values were being adopted by all kinds of games (Colantonio, 2018).

Whether one considers immersive sim a genre in its own right or a sub-genre of FPS, the term is found in frequent use among players, journalists and developers. There is little agreement about the exact parameters of the genre, or which games count towards it, though (Spencer, 2021). This might at first seem surprising, considering that the genre designation originates in a specific text, Warren Spector’s Post-Mortem for Deus Ex (Spector, 2000). However, Spector does not use the formulation “immersive simulation” to propose a genre -- on the contrary, he describes Deus Ex as “a genre-busting game […] -- part immersive simulation, part role-playing game, part first-person shooter, part adventure game” (Spector, 2000). The widespread perception of Deus Ex as a paradigm-changer, coupled with Spector’s prominence as a game designer, led to the term’s adoption not just as a description for the sequels of Deus Ex, but for similar games, particularly ones Spector and his team were involved in [2]. While fans and journalists sometimes expand the genre to a questionable degree -- gaming website Giant Bomb includes e.g. the Elder Scrolls series of RPGs (Giant Bomb, 2021) -- there seems to at least be a consensus that the design ethos of immersive sims can be traced to developer Looking Glass Games and has been embraced by a small number of other studios, particularly Ion Storm, Irrational Games and most recently Arkane Studios (Mahardy, 2015; Tavinor, 2009, p. 188).

Most problems surrounding the term immersive sim are common to all game genre classifications -- and to the concept of genre in general. To Dominic Arsenault, “the very notion of genre is controversial and, quite bluntly, a mess” (Arsenault, 2009, p. 149); to him, “the idea is that the word genre is an umbrella word, and that the bundling of disparate concepts under a single name gives them a false impression of unity” (Arsenault, 2009, p. 157). The sense of unity evoked by genres might be false, but it is appealing, making genre a widespread and naturalized concept that is “often taken for granted” (Gregersen, 2014, p. 163). Even among scholars, it is a relatively new (and not completely uncontroversial) position to accept that genre is “more fluid than stable” (Gregersen, 2014, p. 166), a construct that emerges from factors such as “development studios; the relationships between such developers and publishers; the heavy emphasis on formulas and sequels” (Gregersen, 2014, p. 164). For the games discussed here, this completely applies: the dominance of a few developers was already mentioned, and the same can be observed when it comes to publishers (Bethesda, Eidos, and 2K Games). An emphasis on sequels is equally obvious, with System Shock, Deus Ex, Bioshock (2K Boston, 2007), Dishonored (Arkane Studios, 2012) and their sequels being counted as the core examples of the genre. Game genres are, according to Andreas Gregersen, defined by “player agency: Video game genres imply a clearly identifiable set of typified actions on the part of players” (Gregersen, 2014, p. 164). In most cases, “genre works offer finite provinces of meaning where a particular set of meaningful experiences can be had” (Gregersen, 2014, p. 165).

Although one of the oldest theories of ludic agency was formulated by Doug Church, the game director of System Shock, the kind of agency Church, Spector and other proponents of the genre envision is not that of a singular meaningful experience, but a multiplicity: It is about choice of approach, possible only by blending different concepts (or genres). In a recent interview, Spector credits his frustration with the stealth-only approach of Thief: The Dark Project (Looking Glass Studios 1998) as a central motivator for the genre-mix of Deus Ex (Ars Technica, 2021). Similarly, Arkane Studios’ founder Raphaël Colantonio lists “choices, consequences, play-styles, simulation, layered systems, emergence, non intrusive narration...” (Colantonio, 2018) as the central traits of immersive sims. They therefore exemplify rather clearly a more holistic view of genre as “rooted in game aesthetics, not game mechanics” (Arsenault, 2009, p. 171).

Ultimately, genre classification is based on “presupposed collective knowledge [which] is crucially connected to the way works themselves signal their genre(s)” (Gregersen, 2014, p. 163). In immersive sims, one singular element often considered a tell-tale identifier is the recurrence of “451” or “0451” as a code for doors or safes in games. “451 Games” is therefore an alternative and arguably more clearly defined genre designation based on a shared element, a sort of “secret handshake,” a nod towards the tradition that’s quite obvious to the initiated player. Approaching the genre from this angle introduces a quite clear notion of intentionality: Including the code is a conscious choice of the design team that expresses a feeling of connectedness to the tradition. One can even find a well-established protocol for the use of the code. Mere allusions to the genre are usually hidden as Easter Eggs, e.g. in Fallout 4 (Bethesda, 2015) [3], while games that situate themselves in the tradition usually feature the code prominently in their first number puzzle, following the precedent set by System Shock (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. 451 as the first door code in System Shock. Click image to enlarge.

The way in which Deathloop uses the 0451 reference is symptomatic for its positioning towards the immersive sim genre. When player character Colt Vahn encounters the first door with a number lock on Blackreef, it is strongly suggested that he should know the combination. Players who approach the game with genre-preconceptions may easily assume that it is them who should know the code already, and enter the customary number “0451.” While this does not unlock the door, it prompts Colt to comment that old habits die hard, and unlocks an achievement (see Figure 2). At the time of playing, about two months after launch, only 9.3% of players on PC had unlocked this achievement in Steam. (However, this number comes into perspective when considering that at the same time, only 25% of players had finished the game.) With this simple gesture, Deathloop positions itself in a unique position: The prominent use of the iconic door code in the position traditionally only employed by self-identified immersive sims leaves no doubt that Arkane acknowledge the significance that the genre has for Deathloop. Yet the code does not work as intended. It is not the key to the gameworld, no shortcut that admits veterans of the genre without the need for clues. Instead, it acknowledges the player’s experience and expectations with an achievement that attests their cultural capital as a gamer (Sotamaa, 2010), while simultaneously disavowing itself as an immersive sim. The prominent, historical position at the opening of the game turns what otherwise might be regarded as a mere Easter Egg into a significant statement: If this is an immersive sim, it is one that does not play by the rules.

Figure 2. Deathloop's peculiar reference to 451 games. Click image to enlarge.

There are many more subtle (as well as obvious) signals of an intense struggle with the conventions of immersive sims scattered throughout the game, some of which will be discussed in detail later. One however is so exposed, yet oblique, that it easily goes unnoticed: Within the game and all its promotional material, its title is stylized as “DEATHLOOP”. The quotation marks are usually omitted and ignored, and remain unexplained in the game, opening their strange redundancy to interpretation. While certainly not the only possible reading, the quotation marks suggest a degree of unoriginality, a self-awareness of an unusually pronounced indebtedness to predecessors that the developers feel the need to subtly acknowledge. In many regards, though, Deathloop is quite original, especially compared to similar AAA titles -- it is, at least, no sequel, no reboot, no adaptation. The indebtedness to other sources that the title’s quotation marks suggest has to be more profound, more philosophical, more general.

I want to demonstrate in the following that Deathloop’s complicated relation to its predecessor texts is in line with metamodernist aesthetics, and that reading the game through the lens of this contemporary poetic approach reconciles its apparent idiosyncrasies. Metamodernism is one of several concepts proposed as successors to postmodernism, building on and extending this dominant cultural model of the 20th century. The next section will provide a brief introduction into both postmodern and metamodern thought, as a basis for an in-depth engagement with Deathloop.

Postmodernist and Metamodernist Aesthetic Principles

In the most general terms, postmodernism is the dominant aesthetic principle of the late 20th Century. The term has been applied to architecture, visual art, literature, music, sometimes signifying a period (“post-modern”), sometimes a style (“postmodern”), with many medium-specific approaches describing “a complex of anti-modernist artistic strategies which emerged in the 1950s and developed momentum in the course of the 1960s” (Bertens, 1995, p. 3). The aesthetic innovations were often diametrically opposed, when e.g. postmodern architecture abandons minimalism, while postmodern dance embraces it (Rudrum & Stavris, 2015). The common denominator is a shared aesthetic that operates with “fragments, pastiche, an ironic, sophistical stance, an ethos bordering on kitsch and camp” (Hassan, 2003, p. 4), and is ideologically “linked to an epochal crisis of identity” (Hassan, 2003, p. 5), explaining its affinity towards poststructuralism. Terry Eagleton distinguishes between postmodernity as “a style of thought which is suspicious of classical notions of truth, reason, identity and objectivity” (Eagleton, 1996, p. vii), and postmodernism as “a style of culture which reflects something of this epochal change, in a depthless, decentred, ungrounded, self-reflexive, playful, derivative, eclectic, pluralistic art which blurs the boundaries between ‘high’ and ‘popular’ culture, as well as between art and everyday experience” (Eagleton, 1996, p. vii). In an earlier, influential definition of postmodernism, Ihab Hassan operates with an even longer list of explicit juxtapositions that equate modernism -- among other things -- with metaphysics, determinacy, purpose and form, to which postmodernism reacts with irony, indeterminacy, play and antiform (Hassan, 1987, p. 6). The oft-quoted affinity of postmodernism to play has been commented on frequently, and has been explored early on in game studies (Aarseth, 1997).

One of the central theoretical tenets of postmodernism is Jacques Derrida’s différance, “the disappearance of any originary presence” (Derrida, 1981, p. 168). The basic idea builds on the linguistic realization that all language signs are arbitrary. Words do not originate in things or have immanent connections to them. They only refer to objects or concepts by convention. Derrida takes this realization and radicalizes it to the point where all language is always differential: Saying “chair” is less about identifying a concrete concept and more about excluding all the concepts this word does not refer to (such as “table” or “door”). From this perspective, concepts always exist in “a relational system, a network of actual and possible things and experiences” (Bogost, 2006, p. 105). Différance embraces the uncertainty and vagueness of language, its “irreducibly differentiating and disseminating contradictions” (Derrida, 1981, p. 6), as a productive cultural force.

What makes the idea that all culture exists only in differentiation from other culture so radical is its implication that originality is impossible. Every new work of art is always a reaction to what came before and what is perceived or expected to be around at the time of publication -- an idea that goes a long way to explain Deathloop’s unusual title-typography and 451-reference.

Already at the turn of the 21st Century, however, theorists considered postmodernism to lose its relevance, and started to develop new models that reflected emerging artistic sensibilities more precisely: “Beyond postmodernism, beyond the evasions of poststructuralist theories and pieties of postcolonial studies, we need to discover new relations between selves and others, margins and centers, fragments and wholes -- indeed, new relations between selves and selves, margins and margins, centers and centers” (Hassan, 2003, p. 6).

In their search for new models, critics have proposed (beyond the awkward post-postmodernism) terms like hypermodern, digimodern, pseudomodern, automodern and altermodern, “new cultural paradigms taking the place of the postmodern” (Rudrum & Stavris, 2015, p. xviii). Where the term postmodern contained disparate disciplines and fundamentally different approaches, many of its various successor-concepts are more sharply defined. Altermodernity, for example, is rooted in art criticism and postulates a new international, multicultural modernism, while media studies has produced both automodernism, the value-neutral observation of a paradox of autonomy and automation, as well as the decidedly technology-critical digimodernism (Rudrum & Stavris, 2015). Not all concepts have such a clear profile, though: the philosophy (Josephson-Storm, 2021) and political theory (Freinacht et al., 2017) identified as metamodern have very little, if any, overlap.

The introduction of many particular concepts competing to supplant the broad idea of the postmodern could somewhat cynically “be ascribed to [theorists’] tendency to overrate the importance of the cultural changes of the recent past” (Bertens, 1995, p. 237). Reviewing the programs and manifestoes of the many new -isms side-by-side, one might perceive them less as radical new departures than gradual developments: “The old paradigm is not so much completely discarded as it is rethought, refined, and much improved. […] we would seem to be moving towards a new consensus” (Bertens, 1995, p. 238). This potential ‘new consensus’ was surmised by Ihab Hassan to be “an aesthetic of trust” (Hassan, 2003), less of a concrete theory or period, than an emerging changed attitude and sensibility (Bertens, 1995, p. 5). Of all the successor-concepts to the postmodern, the one most aligned with this understanding of the postmodern legacy is the cultural studies interpretation of metamodernism.

This version of metamodernism, proposed by Dutch scholars Vermeulen and van den Akker, wants “to radicalize the postmodern rather than restructure it” (Vermeulen & van den Akker, 2010, p. 3). Their take on metamodernism identifies elements already present in postmodernism, which through socio-political and technological changes have become excessive: “cultural and (inter) textual hybridity, ‘coincidentality’, consumer (enabled) identities, hedonism, and generally speaking a focus on spatiality rather than temporality” (Vermeulen & van den Akker, 2010, p. 3). Metamodern artists [4] abandon “the aesthetic precepts of deconstruction, parataxis, and pastiche in favor of aesth-ethical notions of reconstruction, myth, and metaxis” and “express a (often guarded) hopefulness and (at times feigned) sincerity that hint at another structure of feeling, intimating another discourse” (Vermeulen & van den Akker, 2010, p. 2). The increased ethical sensibilities result from the integration of “diverging models of identity politics, ranging from global postcolonialism to queer theory” (Vermeulen & van den Akker, 2010, p. 3), and thus address exactly the need for rethinking selfhood and human relations that Hassan felt was missing from postmodernism.

Like metamodern political theory (Freinacht et al., 2017), Vermeulen and van den Akker understand metamodern thinking not as an abandonment or overcoming of the enthusiasm of modernity and the irony of postmodernity, but as their continuation and synthesis. In the 21st Century, the world “can no longer be characterized by either the modern discourse of the universal gaze of the white, western male or its postmodern deconstruction along the heterogeneous lines of race, gender, class, and locality […] instead, it is exemplified by globalized perception, cultural nomadism, and creolization” (Vermeulen & van den Akker, 2010, pp. 3-4). This unifying perspective is made possible by accepting that irony has become ubiquitous: if the shared ironic distance is acknowledged, it can be the basis for the goodwill and trust envisioned by Hassan.

These features of postmodernism and metamodernism (which are, of course, only the tip of the discursive iceberg) are relevant here as, applied to digital games, I would argue that these aesthetic considerations translate to a rough equivalence of FPSs to modernism, immersive sims to postmodernism and Deathloop to metamodernism.

The dominant paradigm of mainstream FPS games is a well-calculated, intricately crafted experience, propagated by the utopian promise of techological progress and never-before seen fidelity, and characterized by a reactionary political stance, in a “world of good and evil, of domination and annihilation, where whiteness and American manhood characterize protectors and heroes” (Gray & Leonard, 2018, p. 6). This affirmative and conservative aesthetic “revolves around limiting risk and giving players what they already know they like, which means limiting the role of luck and building our of ways for them to prove their merit. […] The story lines of many video games teach players that if they work hard enough, if they try long enough, if they are good enough, they will be victorious” (Paul, 2018, p. 92).

Immersive sims with their design ethos of undermining or at least combining genre conventions inevitably depart from this formula to some degree. They are, of course, not alone in this; especially philosophically ambitious, self-reflective digital games like Spec Ops: The Line (Yager, 2012) similarly distance themselves from calcified conventions. Still, they often sit uncomfortably at the intersection of modernist and postmodernist sensibilities, because they try to combine the mass appeal of the straightforward mainstream game with their critical message. The success of this approach has often been called into question, maybe most influentially by Clint Hocking. Writing on Bioshock, he observes that it “seems to suffer from a powerful dissonance between what it is about as a game, and what it is about as a story. By throwing the narrative and ludic elements of the work into opposition, the game seems to openly mock the player for having believed in the fiction of the game at all” (Hocking, 2009, p. 256). Smaller independent games have, by virtue of not having to recoup enormous budgets, been more successful in adapting postmodernist principles, including, however, postmodernism’s negative traits of nihilism and apathy. In the next section, I will detail how modern naivete and postmodern cynicism are overcome in Deathloop through an adoption of metamodern aesthetic principles.

A Game Structure of Perfect Ludonarrative Harmony

The most obvious and potentially most important characteristic of Deathloop is its unusual structure, based on the narrative of Colt being trapped in a timeloop. It would be intuitive to discuss the game based on theories of game time (Juul, 2005; Nitsche, 2007; Tychsen & Hitchens, 2009; Zagal & Mateas, 2010); however, as I will detail below, Deathloop seems much less interested in time than structure. While superficially a time-travel narrative, it is creating spatio-temporal arrangements that defy conventional approaches. Repetition and timeloops are a primarily used topically in Deathloop, reflecting on loops as a game design principle (Sicart, 2015). As game director Dinga Bakaba explains, integrating smaller loops into a greater whole was a design pillar during development: “The entire structure of the game, and how unique it is, is actually the most interesting thing in it. It’s weird, because at some point … actually, in one discussion, I remember saying that it almost feels that we are taking one mission of something like Dishonored 2 and making an entire game out of it […] trying to go as deep and as crazy and expand on it […] … you have to see the whole thing to really appreciate it” (van Aken, 2021).

The game uses neither a labyrinthine arrangement of environments nor a consistent arena, no linear succession of spaces frozen in time nor an open world running on a constant clock. Instead, it breaks its location, the island of Blackreef, into four regions, and divides every day into four phases. As in most games, the possibilities for exploration are gradually unlocked, but relatively soon Colt can visit all locations in any order. The result is a spatio-temporal matrix of a theoretical total of 44=256 paths through a day on Blackreef. In practice, some locations will not be available under certain conditions, yet that does not reduce the number of possible combinations, but rather the opposite: Players can make changes in the morning or noon that affect the rest of a day, which changes the environment and/or the population of a region in a significant way. As a part of the main quest, players need to read a message to the local fireworks maker which discloses the weakness of one of Colt’s assassination targets. If left unattended, though, the fireworks lab will burn down before the message is delivered (see Figure 3). If players visit the fireworks lab in the morning, they will find the likely cause of the fire -- a dangerously unsafe electrical installation -- and can prevent it by disconnecting the place from the power grid. Only after this intervention, the fireworks lab will still be intact and accessible at later times (see Figure 4). There are numerous such interventions players can make, resulting ultimately in a significantly higher number of distinct spatio-temporal paths through a day on Blackreef, and in an incentive to explore all possible causes and effects.

Figure 3. The burnt-out Fireworks Workshop at Noon. Click image to enlarge.

Figure 4. The preserved Fireworks Workshop at Noon. Click image to enlarge.

The larger part of the game’s single-player campaign is spent in this fashion, visiting the four regions in different orders to gather information and equipment, to finally be able to attempt a “golden run” and eliminate all targets in one day. This short description of the game’s main structure shows, if only very briefly, that despite its narrative’s emphasis on time, Deathloop as a whole is not about time -- or at least not in the sense usually discussed in game studies. In the terms of Zagal & Mateas (2010), coordination time appears to be dominant for the segmentation of gameplay into the four daytime-phases which are little else than rounds that the player cycles through. Gameworld time progresses linearly within each space-time-bubble constituted by discrete locations at fixed points in fictive time; the latter is experienced as circular for the visionaries and eternalists, while Colt, Juliana and the player perceive it linearly, or rather as a sequence of never identically repeating loops. The temporal frames of Deathloop are intriguing and would deserve a thorough analysis, but for this analysis, the macro-structure in which they are situated is more relevant.

The game design considerations behind Deathloop’s unconventional structure stem, according to Bakaba, from a dissatisfaction with linearly structured single-player campaigns: “let’s try to have replayability not being a meta-thing, you know, but part of the experience. How can you build familiarity before it’s the last 5 minutes of the game and you feel awesome, and then the game wraps up?” (O'Dwyer, 2021). One recent strategy for avoiding this problem has been the adaptation of elements of the roguelike genre. The combination of randomized level generation, permadeath (the inability to reload after making mistakes) and a “ruleset for physical interactions that is shared by the player, non-player characters (NPCs), and items” (Yu, 2016, p. 6) typical of roguelikes leads to shorter coherent units of play, where success or failure is negotiated in 30-60 minute runs rather than several hour long campaigns. This design principle resembles Deathloop’s structure, and was employed by Arkane in the preceding Prey: Mooncrash (Arkane, 2018). Fans and reviewers often assume a direct connection between both games, and it would be easy to consider Mooncrash a prototype for the later game. However, Arkane operates with two rather independent studios in the USA and France; not only was the Deathloop team not involved with the development of Mooncrash, Bakaba stated that he did not even play the game -- because it was too much of a roguelike [5]. Just like Deathloop simultaneously is and is not an immersive sim, it is and is not a continuation of Arkane’s formal experiments with roguelike elements.

This ambivalent relationship to its predecessors is one of the ways in which Deathloop exemplifies metamodern principles: “the metamodern epistemology (as if) and its ontology (between) should thus be conceived of as a ‘both-neither’ dynamic” (Vermeulen & van den Akker, 2010, p. 6). Writing on games with strong randomization, Mark R. Johnson has recently proposed to use Gilles Deleuze’s version of différance to describe similar processes (Johnson, 2018, pp. 13-20). To Deleuze, difference and repetition are not limited to the level of concepts and words, but equally apply to practices and objects. Every repetition of an act or concept introduces variances, meaning both that any concept only comes into profile through repetition (and the many accumulating small or large differences), and that everything is always relational: No activity or concept is without precedent, because anything either strives to repeat something that came before it, or avoid this repetition through innovation, thus in any case creating a “repetition of difference” (Johnson, 2018, p. 14, original emphasis).

That “repetition of difference” is also what Deathloop constructs: the player has to repeat the same day on Blackreef over and over, yet can do so in ever-permutating fashion. Visiting the four regions at different times in different order already creates repetition and difference, which is further amplified by the ability to change locations through actions at earlier times and set chains of events in action (like with the example of the fireworks lab). As the game progresses, the player discovers more and more options for enacting permanent changes that carry over to the following days, from which point on these differences over the previously repeated experiences can be explored. And ultimately, the game will signal to the player when they have discovered a possibility for a “breaking the loop” by killing all Visionaries in the same day, at which point the previously open, explorative structure becomes flattened into one linear path with a pre-planned order of actions that need to be enacted at the right places and times. This might take the player several attempts, again creating repetition of another different spatio-temporal arrangement, ameliorating the ludonarrative dissonance observed by Hocking in Bioshock.

Hocking’s original proposal of the concept of ludonarrative dissonance is relevant here for another reason: Hocking not only juxtaposes rules and fiction or procedures and semiotics, but much more concretely (albeit implicitly) Bioshock to Far Cry 2 (Ubisoft, 2008), the game he spearheaded at the time (Hocking, 2009). There is a major structural difference between the two games that adds to the different impact he observes: The moments of choice (or, in his view, non-choice) between harvesting and freeing the Little Sisters in Bioshock occur in a relatively linear sequence. The player will face the same choice time and again, and in temporal succession, which emphasizes that this dilemma is one that pertains through time. Every choice is made only once, and the outcome of each choice can thus not be verified or validated. Far Cry 2, on the other hand, represents through its mechanic of respawning enemies at guard posts that the civil war raging in the gameworld cannot be won by the player character. Their threat is immutable and omnipresent, distributed throughout the whole gameworld, as the player can verify by trying (without success) to permanently pacify individual places. Far Cry 2 thus resists a grand narrative of white male individual success, and does so through a ludonarrative construct that emphasizes spatial disorder. These different strategies again align with a modern and postmodern aesthetic, to which Deathloop’s model forms a metamodern synthesis: “Thus, if the modern suggests a temporal ordering, and the postmodern implies a spatial disordering, then the metamodern should be understood as a spacetime that is both -- neither ordered and disordered. Metamodernism displaces the parameters of the present with those of a future presence that is futureless; and it displaces the boundaries of our place with those of a surreal place that is placeless” (Vermeulen & van den Akker, 2010, p. 12).

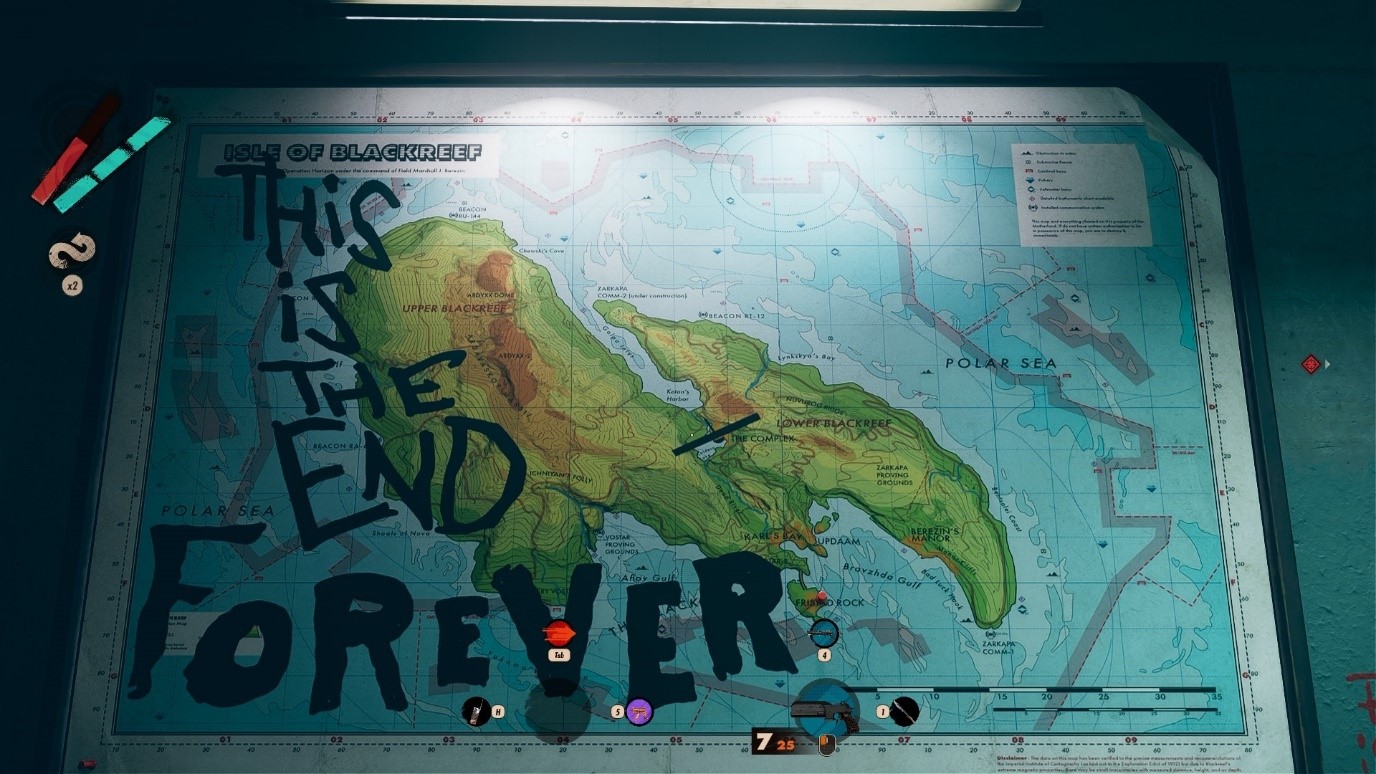

The island of Blackreef is exactly that: A surreal place that is both placeless and timeless. While situated in a Polar Sea, Blackreef does not seem to be on (our) Earth, but on a different planet or in a parallel universe with different sociopolitical entities. Names on maps refer to no real places or persons, and even the conventions of mapping are not quite identical to ours (see Figure 5). Nationalities are suggested, yet never quite confirmed -- the apparently African-American pilot Colt appears to have been part of an army of the Great Russian Motherland. And while set in the 1960s, technology is far more advanced than in reality -- communication on Blackreef uses a microcomputer system akin to the Minitel popular in 1980s France.

Figure 5. An in-game map of Blackreef. Click image to enlarge.

None of this is unusual for fictional worlds encountered in digital games, but the overall structure of Deathloop amplifies this spatio-temporal surrealism, also through the calculated irony and the multi-layered metaphors of its narrative.

The Subtext of Characters and Ending

The undoubtedly and unambiguously self-referential character of the game is Charlie Montague, the game designer. Several of Deathloop’s locations contain his creations, posters indicate a number of earlier and planned games, and his home is littered with notes and sketches for new scenarios and mechanics. Engaging with Charlie’s games is inevitable, because the only location where players can initially encounter him is an isolated mansion that serves as the locale for his game “Condition Detachment”. The game-within-the-game is a mixture of LARP and laser tag, yet in a form only possible in the world of Deathloop: Participants role-play at being space travelers on a foreign planet who are attacked by an interloper -- a role defined by the rules as the last player to arrive, which happens to always be player-character Colt. Because the players know that they live in a timeloop and that death will thus be without consequence, they use live ammunition, poison gas and explosives to hunt one another. The essential reality of these play actions -- where killing someone in game means actually killing them, yet in the knowledge of their certain resurrection -- stands in stark contrast to the environment. The decoration and apparatus of Charlie’s game is impressive, occupying a whole building, yet all of it is unabashedly fake and cheap. Crudely painted cardboard and plywood barely obscure the machinery behind them, forcing the players -- both intradiegetic and empirical ones -- to reconcile the artificiality of the environment with the immediacy of the actions happening within it (see Figure 6).

It is not much of a stretch to interpret “Condition Detachment” as a microcosmic representation of Deathloop and, by extension, FPS or even digital games in general. The allusion to specifically digital games is reinforced by Charlie using a computer as a game master to organize and regulate play. The computer is, within the context of Deathloop’s 1960s setting, a technological marvel, with its ability to receive voice commands and synthesize its own verbal replies. Still, every single sentence it utters exposes the limitations and artificiality of artificial intelligence, which is already foreshadowed in the computer’s name, 2-B.I.T. Primitive and rudimentary as the name suggests, the computer still is a tremendous piece of technology, only made possible by Charlie transplanting half his brain into the machine. The half-brained game designer and his equally half-brained thinking machine that struggles endlessly with natural language are an unsubtle piece of self-irony that might easily be dismissed as a quirky, humoristic aside. To a more benevolent eye, it might appear as an adequately tongue-in-cheek admission of the persistent human and technical limitations of game design through a clever mise-en-abyme construction of not only a game-within-a-game, but a game designer’s reflections on the process of developing and running a game.

Figure 6. The Entrance to Charlie Montague's "Condition Detachment." Click image to enlarge.

Deathloop’s meta-referentiality of digital game production is, however, not limited to Charlie Montague and the games he has created on the island of Blackreef. On the contrary, the whole artificial environment of Blackreef forms a game environment, and the visionaries are a more or less thinly veiled allusion to the typical roles in game development. Frank Spicer, the musician, and Fia Zborowska, the artist, stand for game audio and visuals. Wenjie Evans and Egor Serling, the two scientists, explore what is possible on the island with its temporal anomaly, and how the behavior of people on it can be measured and controlled. Their roles correlate with the technical domains of engine programming and live operations. Aleksis Dorsey, the financial backer of the project with his penchant for lavish parties and the conviction to know everything better than his peers, appears as a stand-in for publishing and marketing, while Harriet Morse, the sociologist-turned-cult leader, could be seen as community management. Juliana’s role as archivist and interim head of security translates to project management -- she documents development and keeps everybody on track, while identifying potential problems along the way. That the final visionary, Colt, is easily overlooked, is even a plot point in the ending of the game, where Colt needs to remind himself (and the player) that he is one of the visionaries and that killing them all means killing himself. This is only fitting, as Colt’s function in the overarching game development metaphor is that of the player and play-tester: He is thrown into the carefully balanced system to find its breaking points, to beat the challenges in potentially unforeseen ways, thus unraveling the work the other actors in the process have done before him. Given the violent conceit of the narrative -- Colt has to kill everyone, even himself -- this might initially appear as overly combative and antagonistic, but it actually is not. Colt plays as much with the other visionaries as he plays against them, and every time he plays again, he brings both them and their creation back to life. By casting the empirical player as a player-figure in the metaphor of the game-as-game-development, Deathloop sidesteps Freudian connotations of oedipal struggles between artists. Where games with similar metaphors, like The Beginner’s Guide (Everything Unlimited, 2015), construct engagement with game development through the eyes of fellow game designers and thus engage with issues of dominance, plagiarism and a Harold-Bloomian anxiety of influence, Deathloop puts the players in their place, for better or worse. They are not equals of the developers, and do not have to struggle for control or authorship. They are something more important and precious, the other half of a relationship in which both sides depend upon one another.

The combination of fully embracing First-Person-Shooter logic instead of explaining it away -- of course everybody on Blackreef is there to shoot you, or get shot -- and the multilayered characters and overarching metaphors is undoubtably ironic. Everything about the game is tongue-in-cheek, but nothing is naïve or nihilistic. The 1960s setting creates a productive distance to world and characters: when they discuss their epiphanies and revolutionary thoughts, they are speaking out of the perspective of a different generation, suggesting to the player that none of this is meant to be original and groundbreaking, yet rarely completely disavowing their ideas. One of the strengths of Deathloop’s character writing is that even proper villains like Aleksis Dorsey have endearing quirks, engendering some degree of sympathy for the fate of these flawed human being trapped in a nightmare of their own making. This type of irony found in Deathloop is unlike the cynical jadedness of e.g. The Stanley Parable (Galactic Café, 2011), which constructs an antagonistic relationship between player and developer (Backe & Thon, 2019).

Deathloop expresses a more hopeful view. The game has three endings, which -- somewhat predictably -- end the loop by killing everyone (including Colt and Juliana), preserve the status quo as it is, or preserve the loop with Colt and Juliana working together. These options translate -- as also noted by a player on Reddit (teh_stev3, 2022) -- to the three options after finishing the main quest: The player can leave the game (break the loop), can keep playing the game (preserve the loop), or can play with Juliana -- which rather is playing as Juliana: By finishing the campaign, players unlock the limited multiplayer functionality, where a player can (as Juliana) invade another player’s game to hunt them.

With these endings, the development team acknowledges the realities of digital game lifecycles. Ending one, the breaking of the loop, acknowledges that Deathloop will stop being played one day; ending two, the continuation of play, stands for the hope that players will enjoy and explore the game after finishing it for the first time; and ending three symbolizes the extended leave of life single-player games receive from their multiplayer modes. This construction is hopeful in that it addresses the options and perspectives for the individual player years ahead. The invading Juliana will, if a player chooses to play offline or if there are not enough human-controlled Julianas available, be controlled by an AI. Even if there is a perceptible qualitative difference between a human and an AI controlled Juliana, Deathloop is constructed in a way that ensures it will not become completely unplayable or lose its significance, while still allowing the originally envisioned ideal game to shine through. Playing against and with Juliana personifies playing with and against Deathloop as a whole.

But the endings are also hopeful in the sense that they are reconciliatory and forgiving: where other games are driven by the impetus to retain customers as long as anyway possible, by releasing all sorts of downloadable content and addons, Deathloop embraces the inevitability that at some point, the player will move on -- and tells them that this is okay. It is a very small gesture of goodwill, honesty and empathy on the part of the developers, but one that is exceedingly rare in an ecosystem dominated by metrics of daily active players and return-on-investment. Just like Colt and Julianna establish their relationship at the end of the game, and can then decide how to take it further and when to let go of the status quo without hard feelings, the players and developers know where they stand at the end of the campaign, what each side has brought to the table, and that leaving the game behind will not mean that either of them stops cherishing the game and the experience with it. And it does not rule out the possibility of returning. As Bakaba puts it in an interview: Deathloop is about “moving on” (van Aken, 2021) -- not as a threat or a solution, but as a fact of life. That is then, finally, how Deathloop fully embraces metamodern sensibilities, by constructing an ending to the campaign that fully aligns with the narrative as well as the game-modes and the players relation to them. The ending creates an atemporality that complements the diffuse and surreal spatiality of Blackreef; a ludonarrative space-time that is both harmonious without falling into the trap of a totalizing modern grand narrative, and ironic without the postmodern cynicism of most other meta-games.

Conclusion

In this article, I have presented the argument that Deathloop has challenged players and reviewers because they try to understand the game as a part of the genre of immersive sim. I argue that while awareness of the genre is crucial for an informed interpretation of the game -- with the caveats that apply to all game genres -- Deathloop cannot be understood as a part of the genre. Through signals like the “Old habits die hard” achievement, the game signals clearly its uneasy relation to the genre, depending on it while not unambiguously belonging there. The concept of metamodernism offers a framework to understand this uneasy, tense aesthetic relation, and through an analysis of Deathloop’s structure and narrative I have shown how closely the game adheres to metamodernist values of aesth-ethics, hopefulness and truthfulness, as well as its particular spatio-temporal and referential ambiguity.

The presented argument demonstrates that Deathloop, a cultural product which has baffled its critics and consumers alike, emerges largely explicable when seen through the lens of metamodernism. Just like the game it deals with, this article omits many elements and perspectives one might expect from it, yet in both cases there are good reasons for these omissions. I have offered no critique of metamodernism, for example, because it serves primarily as an intellectual backdrop for the reading of Deathloop. I make no claims about the truth-value or stringency of Vermeulen and van den Akker’s postulates; their diagnosis of changed cultural sensibilities and the resulting shifting aesthetics contextualize traits of Deathloop that otherwise would seem as mere oddities, even if one should disagree with their take on post-postmodernism. Neither do I discuss future application or limitations of the method used here, because the method -- game hermeneutics -- is malleable and universal, and its limitations are the same as that of the hermeneutic method used for centuries. The specifics of the analysis here, the recourse to metamodernism and the foregrounding of game structure and ludo-narrative harmony, emerge from the properties observed in the example and cannot be generalized as such -- which does not mean that it would not be productive to reconsider other digital games in the context of metamodernism, or compare unusual game structures that blend features of linear progression and roguelike recursion.

Finally, I do not proclaim a new period here, do not champion metamodernism as a dominant paradigm for the 2020s, nor propose a new analysis method. More modestly, but not less importantly (or proudly), I have shown that the venerable tool of hermeneutics is powerful, even indispensable, when approaching contemporary examples that challenges conventions. I have not made an explicit argument for why games in general, or Deathloop in particular, should be considered art -- others have made that argument a while ago quite successfully (Smuts, 2005) -- not the least because from a metamodern perspective, the distinction between art and mass culture is no longer relevant, if it even can still be maintained. Neither do I claim that the aesthetic principles I have observed in Deathloop are in themselves innovative or unique. On the contrary, it rather has a universal quality, in that it’s implicit emphasis of what it does not do is typical of play: “human play, regardless of the objects being played with, embodies a reference to what is not -- or to something other than what it is” (Myers, 2009, pp. 46-47).

What ultimately sets Deathloop apart is that it is constructed purposefully to reflect on its own preconditions, its genre, its player and to do all this so playfully and unobtrusively as to be criticized for being simplistic instead of aloof or pretentious. It manages to be meta -- metamodern and meta-immersive sim -- without even a whiff of an art-game, which in itself is an achievement that might very well be a paradigm shift towards metamodern games. Only time will tell if Deathloop has broken out of its own loop -- and if it ever was meant to do so in the first place.

Endnotes

[1] Immersive Sim is sometimes treated as a design philosophy, style, or school rather than a genre. While these approaches might be more productive, the point of this article is not primarily to explore the commonality between Immersive Sims, but rather the interesting ways in which Deathloop deviates from common denominators. For that purpose, the use of genre (theory) is adequate and sufficient.

[2] The recategorization of a hybrid of genres as a new genre and even a norm is a common development. “We can also note that games which stand out in experience as hybrid probably do so because of their historical background, i.e., they are combining generic resources in novel ways: Over time, novelty may fade into the new norm” (Gregersen 2014, p. 167).

[3] Fallout 4 uses 0451 as the code to a room containing a powerful weapon. The location, the Vitale Pump Station, is not marked on the in-game map and can only be found by accident, in a rather remote part of the gameworld’s east coast. Lead Level Designer Joel Burgess calls the 451 reference explicitly an Easter Egg (Burgess, 2019).

[4] It is important to note that the concept of Metamodern is not directly tied to contemporary or recent art. The authors discuss at some length the films of David Lynch, particularly Blue Velvet (1995) as metamodern. (Vermeulen and van den Akker 2010, p. 10).

[5] “I asked him if Prey’s terrific DLC Mooncrash was an inspiration at all in the creation of Deathloop, and he said that while he played a couple of hours, he then suddenly realized it was as much a time-loop game as it was a roguelike, and immediately put it down” (O'Dwyer, 2021).

References

2K Boston. (2007). Bioshock [Windows PC]. Digital game directed by Ken Levine, published by 2K Games.

Aarseth, E. J. (1997). Cybertext: Perspectives on ergodic literature. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Arkane Studios. (2012). Dishonored [Windows PC]. Digital game directed by Harvey Smith and Raphaël Colantonio, published by Bethesda Softworks.

Arkane Studios Austin. (2017). Prey [Windows PC]. Digital game directed by Raphaël Colantonio, published by Bethesda Softworks.

Arkane Studios Austin. (2018). Prey: Mooncrash [Windows PC]. Digital game directed by Ricardo Bare, published by Bethesda Softworks.

Arkane Studios Lyon. (2016). Dishonored 2 [Windows PC]. Digital game directed by Harvey Smith, published by Bethesda Softworks.

Arkane Studios Lyon. (2021). “Deathloop” [Windows PC]. Digital game directed by Dinga Bakaba, published by Bethesda Softworks.

Ars Technica. (2021, December 16). How Deus Ex Blended Genres To Change Shooters Forever | War Stories [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bb98qIZfwgc

Arsenault, D. (2009). Video Game Genre, Evolution and Innovation. Eludamos. Journal for Computer Game Culture, 3(2), 149-176. https://septentrio.uit.no/index.php/eludamos/article/view/vol3no2-3

Backe, H.-J. (2018). Metareferentiality through in-game images in immersive simulation game. In S. Dahlskog, S. Deterding, J. Font, M. Khandaker, C. M. Olsson, S. Risi, & C. Salge (Eds.), Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games (pp. 1-10). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3235765.3235799

Backe, H.-J., & Thon, J.-N. (2019). Playing with Identity Authors, Narrators, Avatars, and Players in The Stanley Parable and The Beginner’s Guide. Diegesis, 8(2). https://www.diegesis.uni-wuppertal.de/index.php/diegesis/article/view/357

Bertens, J. W. (1995). The idea of the postmodern: A history (1st ed.). Routledge.

Bethesda Game Studios. (2015). Fallout 4 [Windows PC]. Digital game directed by Todd Howard, distributed by Bethesda Softworks.

Bogost, I. (2006). Unit operations: An approach to videogame criticism. MIT.

Burgess, J. (2019). Stumbled across an old easter egg I put in Fallout 4 [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/joelburgess/status/1151812661472124928

Call, J. (2012). Bigger, Better, Stronger, Faster: Disposable Bodies and Cyborg Construction. In J. Call, K. Whitlock, & G. Voorhees (Eds.), Guns, grenades, and grunts: First-person shooter games (pp. 133-152). Continuum.

Colantonio, R. (2018). As a fan of Immersive Sims [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/rafcolantonio/status/992864422245920768

Derrida, J. (1981). Dissemination. University of Chicago Press.

Eagleton, T. (1996). The Illusions of Postmodernism. John Wiley & Sons.

Everything Unlimited. (2015). The Beginner’s Guide [Windows PC]. Digital game directed by Davey Wreden, published by Everything Unlimited Ltd.

Freinacht, H., Görtz, D., & Friis, E. E. (2017). The Listening Society: A Metamodern Guide to Politics. Book One. Metamoderna.

Galactic Café. (2011). The Stanley Parable [Windows PC]. Digital game designed by Davey Wreden and William Pugh, published by Galactic Café.

Giant Bomb. (2021, December 29). Immersive Sim. Giant Bomb. https://www.giantbomb.com/immersive-sim/3015-5700/

Gray, K. L., & Leonard, D. J. (2018). Woke gaming: Digital challenges to oppression and social injustice. University of Washington Press.

Gregersen, A. (2014). Generic Structures, Generic Experiences: A Cognitive Experientialist Approach to Video Game Analysis. Philosophy & Technology, 27(2), 159-175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-013-0125-8

Hassan, I. (1987). The Postmodern Turn: Essays in Postmodern Theory and Culture.

Hassan, I. (2003). Beyond Postmodernism. Angelaki, 8(1), 3-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/09697250301198

Hocking, C. (2009). Ludonarrative dissonance in Bioshock: The problem of what the game is about. In D. Davidson (Ed.), Well played 1.0: Video games, value and meaning. ETC Press. https://kilthub.cmu.edu/ndownloader/files/12212909#page=265

id Software. (1993). Doom [Windows PC]. Digital game designed by John Romero, Tom Hall, and Sandy Petersen, distributed by id Software.

id Software. (2020). Doom Eternal [Windows PC]. Digital game directed by Hugo Martin, distributed by Bethesda Softworks.

Ion Storm. (2000). Deus Ex [Windows PC]. Digital Game directed by Warren Spector, published by Eidos Interactive.

Irrational Games and Looking Glass Studios. (1999). System Shock 2 [Windows PC]. Digital game designed by Ken Levine, published by Electronic Arts.

Johnson, M. R. (2018). The unpredictability of gameplay. Bloomsbury Academic.

Josephson-Storm, J. Ā. (2021). Metamodernism: The future of theory. The University of Chicago Press.

Juul, J. (2005). Half-Real: Video Games between Real Rules and Fictional Worlds. MIT Press.

Looking Glass Studios. (1998). Thief: The Dark Project [Windows PC]. Digital Game directed by Greg LoPiccolo, published by Eidos Interactive.

Looking Glass Technologies. (1994). System Shock [Windows PC]. Digital Game directed by Doug Church, published by Origin Systems.

Machine Games. (2014). Wolfenstein: The New Order [Windows PC]. Digital game directed by Jens Matthies, distributed by Bethesda Softworks.

Mahardy, M. (2015). Ahead of its Time: The History of Looking Glass. Polygon. https://www.polygon.com/2015/4/6/8285529/looking-glass-history

Myers, D. (2009). The Video Game Aesthetic. Play as Form. In B. Perron & M. J. P. Wolf (Eds.), The video game theory reader 2 (pp. 45-63). Routledge.

Nitsche, M. (2007). Mapping Time in Video Games. In DiGRA. Symposium conducted at the meeting of DiGRA. http://www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/07313.10131.pdf

O'Dwyer, D. (2021). Deathloop’s Design Explained by Creative Director Dinga Bakaba. Noclip. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3ra-jkrurR4

Paul, C. A. (2018). The toxic meritocracy of video games: Why gaming culture is the worst. University of Minnesota Press.

Rudrum, D., & Stavris, N. (2015). Supplanting the Postmodern: An Anthology of Writings on the Arts and Culture of the Early 21st Century. Bloomsbury Academic.

Seselj, D. (2022). Review: Deathloop. Steam. https://steamcommunity.com/profiles/76561198051270780/recommended/1252330/

Sicart, M. (2015). Loops and Metagames: Understanding Game Design Structures. In B. Li & M. Nelson (Chairs), Foundations of Digital Games, Pacific Grove, CA. https://www.miguelsicart.net/publications/Loops%20and%20Metagames.pdf

Smuts, A. (2005). Are video games art? Contemporary Aesthetics, 3(1), Article 6. https://digitalcommons.risd.edu/liberalarts_contempaesthetics/vol3/iss1/6/

Sotamaa, O. (2010). Achievement Unlocked: Rethinking Gaming Capital. In O. Sotamaa & T. Karppi (Eds.), Games as Services: Final Report (pp. 73-81).

Spector, W. (2000). Postmortem: Ion Storm's Deus Ex. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/design/postmortem-ion-storm-s-i-deus-ex-i-

Spencer, A. (2021, October 19). Does Deathloop prove that 'immersive sim' is an outdated term? Edge. https://www.gamesradar.com/does-deathloop-prove-that-immersive-sim-is-an-outdated-term/

Tassi, P. (2021, September 18). Deathloop is a critical hit, but how are the sales? Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/paultassi/2021/09/18/deathloop-is-a-critical-hit-but-how-are-sales/

Tavinor, G. (2009). The art of videogames. New directions in aesthetics. Wiley-Blackwell.

teh_stev3. (2022). The meta-narrative of "Protect the loop" [Online forum post]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/Deathloop/comments/rxdqnh/the_metanarrative_of_protect_the_loop/

Therrien, C. (2015). Inspecting Video Game Historiography Through Critical Lens: Etymology of the First-Person Shooter Genre. Game Studies. The International Journal of Computer Game Research, 15(2). http://gamestudies.org/1502/articles/therrien

Tychsen, A., & Hitchens, M. (2009). Game Time: Modeling and Analyzing Time in Multiplayer and Massively Multiplayer Games. Games and Culture, 4(2), 170-201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412008325479

Ubisoft Montréal. (2008). Far Cry 2 [Windows PC]. Digital game directed by Clint Hocking, distributed by Ubisoft.

Valve. (1998). Half-Life [Windows PC]. Digital game directed by Gabe Newell, distributed by Sierra Entertainment.

van Aken, A. (2021, March 10). 80 Rapid Fire Questions About Deathloop. Game Informer. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zLsYSWIJUS4

Vermeulen, T., & van den Akker, R. (2010). Notes on metamodernism. Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, 2(1), 5677. https://doi.org/10.3402/jac.v2i0.5677

Yager. (2012). Spec Ops: The Line [Windows PC]. Digital game directed by Cory Davis, distributed by 2K Games.

Yu, D. (2016). Spelunky. Boss Fight Books.

Zagal, J. P., & Mateas, M. (2010). Time in Video Games: A Survey and Analysis. Simulation & Gaming, 41(6), 844-868. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878110375594