The Digital Game Analysis Protocol (DiGAP): Introducing a Guide for Reflexive and Transparent Game Analyses

by Rowan Daneels, Maarten Denoo, Alexander Vandewalle, Bruno Dupont, Steven MallietAbstract

The analysis of digital games is a widely used method in the field of game studies and an important instrument to study games and game-related topics. However, existing methodological work showcases a divergency of perspectives on game analyses, hindering the development of clear guidelines on how to actually conduct them. This lack of methodological consensus is fueled further by several complexities when analyzing games, such as the active participation that is required on the part of the researchers. Therefore, the current paper proposes the Digital Game Analysis Protocol (DiGAP), a methodological toolkit that, compared to existing methodological frameworks, provides researchers with sufficient flexibility and adaptability in order to cater to a game analysis’ specific focus and needs. DiGAP’s goal is twofold: to make researchers reflect on the potential impact of their methodological choices on the analysis and interpretation of game content, and to promote the transparent reporting of game analyses in academic manuscripts. Based on previous methodological scholarship, the authors’ prior game analysis experience and brainstorm meetings between members of our interdisciplinary author team, DiGAP consists of 31 items categorized in seven sections: (1) Rationale & objectives, (2) Researcher background, (3) Game selection, (4) Boundaries, (5) Analysis approach, (6) Coding techniques & data extraction and (7) Reporting & transparency. Due to its comprehensive setup and its reflexive nature, DiGAP may be used as a (didactic) checklist to make insights from the field of game studies regarding game analyses accessible to a broader range of research fields (e.g., communication and human-computer interaction). This, in turn, makes it equally valuable for (student) researchers unfamiliar with the method of game analysis as well as more experienced game scholars.

Keywords: DiGAP, game analysis, Guidelines, Methodology, Protocol, Reporting, Transparency

Authors' Note

Maarten Denoo (author 2) and Alexander Vandewalle (author 3) contributed equally to the realization of this paper, and are therefore shared second author.

Introduction

Researchers employ a variety of methods to study games and game-related aspects. The analysis of games and game content, especially, serves as an important methodological approach to understand, for example, the structure of and representations within games (Egenfeldt-Nielsen et al., 2019), the available game experiences for players (Burridge et al., 2019), or the effects that playing games might have on specific players (Slater, 2013). While game analysis is not a commonly used approach in all fields of communication research, such as human-computer interaction (Barr, 2008), it is widely used in the field of game studies to examine a broad range of topics, including narrative aspects in military first-person shooter games (Breuer et al., 2011), quests in role-playing games (Karlsen, 2008) and characters in games set in classical antiquity (Vandewalle & Malliet, 2020), or to investigate specific titles such as Super Mario Galaxy (Nintendo, 2007; analysis by Linares, 2009) or Spec Ops: The Line (Yager Development, 2012; analysis by Keogh, 2013) in-depth.

In sharp contrast with how frequently the method of game analysis is applied stands the lack of methodological consensus and standardization on how to conduct a game analysis and subsequently report on the analysis in a transparent manner. Moreover, such a common ground for game analyses is hindered by several difficulties when analyzing games. First, games as such are conceptualized in various ways -- for example, as media (e.g., Daneels et al., 2021), texts (e.g., Consalvo & Dutton, 2006) or cultural objects (e.g., Cayatte, 2017). Consequently, despite a seemingly common humanities and cultural studies foundation for many game analysis frameworks (cf. Mäyrä, 2008), a great ontological and epistemological variety can be found in existing analytical frameworks, which hinders the development of clear guidelines on how to actually conduct a game analysis. Second, the participatory nature of digital games affects the analyzed content, not only due to researchers’ own input during play as the content is being produced in real-time (Malliet, 2007; Schmierbach, 2009), but also by the different decisions researchers make, such as the level difficulty they select to play the game or specific in-game choices that create different narrative branches. Third, a substantial amount of fundamental methodological work on game analyses dates from the early days of the game studies research field (e.g., Aarseth, 2003; Consalvo & Dutton, 2006; Hunicke et al., 2004; Malliet, 2007). While more recent sources have provided valuable methodological updates on game analyses, often linked to a specific perspective or analytical approach (e.g., Carr, 2019; Fernández-Vara, 2019), work that systematically offers a cross-historical overview of game analysis methodology is seemingly lacking.

The aim of the current paper is to overcome the aforementioned challenges by introducing and elaborating on the Digital Game Analysis Protocol (or DiGAP), a methodological tool similar to the PRISMA approach for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Moher et al., 2015). DiGAP allows researchers to not only reflect on their influence on and choices during the game analysis, but also to report on their analysis in a systematic and transparent way. Instead of proposing a “one size fits all” rigid analytical approach, DiGAP offers researchers a flexible and comprehensive checklist that allows for sufficient adaptability to accommodate a study’s focus. The next paragraphs provide an overview of existing methodological work on game analyses, a brief description of how DiGAP was developed and an elaboration of each item within the protocol.

Existing Methodological Work on Game Analyses

Together with the birth of game studies as a research field (i.e., around 2000, cf. Aarseth, 2021), methodological interest in the analysis of digital games started to grow. Initial work by Konzack (2002) and Aarseth (2003) stressed the importance of awareness concerning the influence of researchers on the analyzed content (e.g., researchers’ own play motivations and prior experiences). They also argued that the selection of games for the analysis needs to be “well-argued and thoroughly defensible” (Aarseth, 2003, p.6) and named several different data collection techniques. Primarily, however, these authors focused on (1) various aspects that may impact the version and actualization of the game during the analysis, such as the used hardware or platform (Konzack, 2002) or how extensively the game has been played in the analysis (Aarseth, 2003) and (2) how researchers approach the aspects that need to be included in the analysis, from Konzack’s (2002) primarily ludology-based focus to Aarseth’s (2003) broader attention to the combination of gameplay, game rules and the gameworld.

Several authors built on this early work, making methodological contributions that can be grouped into five points of interest: how researchers’ backgrounds influence the analysis, how a game sample is selected, which boundaries of the analyzed content need to be set, which analytical approach is chosen and how data may be coded or processed reliably and transparently to lead to insights on the analyzed game(s). We will briefly discuss each of these questions.

First, Schmierbach (2009) repeated Aarseth’s (2003) argument regarding play motivations and prior experiences influencing a game analysis, calling for awareness of researcher bias during a game analysis (cf. Fernández-Vara, 2019). Similarly, several authors advocated for the explicit mentioning of researcher bias by reporting in a self-reflexive manner (Cuttell, 2015) and the elaboration of aspects such as researchers’ socio-cultural background and game-related preferences (Barr, 2008; Fernández-Vara, 2019; Lankoski & Björk, 2015).

Second, increasing attention has been devoted to the configuration of a game sample. For example, Masso (2009) selected games the researcher had not yet played in order to limit researcher bias. Conversely, other scholars argued for different selection criteria, including: relevance to the research topic; diversity in terms of genre, narrative and/or mechanics; representativity of games in general; and accessibility and familiarity to the researchers (Barr, 2008; Malliet, 2007; Schmierbach, 2009).

Third, both Masso (2009) and Schmierbach (2009) emphasized the necessity of setting clear limits regarding the game content in terms of unitizing (i.e., dividing the analyzed content into separate units). Furthermore, Fernández-Vara (2019) proposed specific boundaries and called for transparency regarding, for instance, the difficulty level and version of the game, such as the game’s hardware or platform (cf. Konzack, 2002), or localization (i.e., possible changes that were made when the game was adapted for foreign markets). Furthermore, Aarseth’s (2003) insights on different levels of engagement and the use of secondary sources (cf. below) have left traces in recent work, as some scholars suggested that a game analysis should consist of “repeated” or “multiple” play sessions (Carr, 2019; Lankoski & Björk, 2015; Malliet, 2007), while other game analyses have engaged in “light” play as a consequence of the research topic or the size of the game sample (e.g., Blom, 2020; Hitchens, 2011). Additionally, Masso (2009) and Fernández-Vara (2019) have recommended adding “meta-ludic texts” or “paratexts” such as game reviews, walkthroughs, official websites or fan community websites to the game analysis.

Fourth, recent work has updated Aarseth’s (2003) efforts regarding the clarification of the analytical approach. Whereas some scholars implemented an analytical framework without mentioning the specific categories (Barr, 2008; Egenfeldt-Nielsen et al., 2019), others suggested specific frameworks or toolkits, which included one or more of the following game aspects: in-game objects or components, controls, formal mechanics, interface and representation, game actions and goals, the narrative, audiovisual aspects and the broader design/social/economic context (Cayatte, 2017; Consalvo & Dutton, 2006; Fernández-Vara, 2019; Lankoski & Björk, 2015; Malliet, 2007; Mäyrä, 2008). Although nearly all of these sources described frameworks that can be considered as textual or formal analyses, they represent the existing variety of frameworks that makes it difficult for researchers to select the appropriate analytical approach for their specific game analysis.

Fifth, some academic attention has revolved around specific techniques to extract insights from a game analysis. Malliet (2007) and Schmierbach (2009) stated that coder training for multiple researchers conducting the same game analysis is essential to gain comparable and reliable data. Scholars have also mentioned several sources of data that can be used during a game analysis: (field) notes, recorded game sessions, transcriptions of audio material and screenshots to name but a few (Barr, 2008; Malliet, 2007; Masso, 2009; Schmierbach, 2009).

To summarize, existing methodological scholarship on game analyses provides sufficient, although scattered and often overlapping information, resources and analytical perspectives for researchers intending to conduct a game analysis. Instead of providing yet another narrow analytical framework, the Digital Game Analysis Protocol (DiGAP) produces a checklist based on this previous methodological scholarship so researchers can conduct a comprehensive game analysis while being aware of their own impact on the analysis, transparent about their methodological choices and flexible towards their specific research topic.

Developing DiGAP

DiGAP was developed throughout a range of virtual meetings between 2020 and 2022 by an interdisciplinary group of game researchers from multiple institutions in Belgium. Since these researchers come from various academic backgrounds (social sciences, communication sciences, human-computer interaction and literary studies), are working on different projects at different levels (PhD research, post-doctoral research and research at the level of professor) and are well-versed in both qualitative and quantitative approaches, a scholarly and institutional diversity that was deemed a practical and valid foundation for this protocol was created. In addition, some of the involved scholars already have experience presenting methodological discussions of game content analysis at renowned academic conferences (e.g., Daneels et al., 2019). All of them have long-standing experience with games before starting their academic work.

While early meetings consisted of sharing experiences with game (content) analyses across the aforementioned fields and discussing how common problems could be resolved, these conversations gradually evolved into gathering and theorizing common game research aspects (the items mentioned below) in structured brainstorming documents. Through repeated discussion among the authors of this paper, a synthesis of key research publications that touched upon methodological issues in game analysis (see draft documents on OSF) as well as one joint-authored conference submission (Daneels et al., 2022) of which the reviews allowed for expert feedback on a first iteration of the protocol, these insights were eventually gathered into DiGAP, which can be consulted in schematic form on OSF.

Elaboration of the DiGAP Items

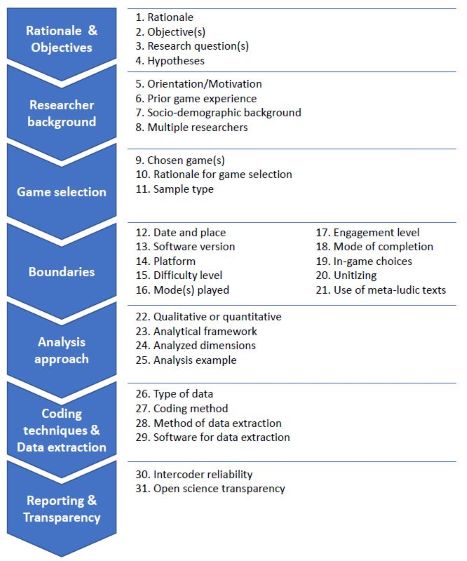

DiGAP consists of seven sections, adding two general sections on proper research conduct to the above five points of interest identified in previous game methodological research (see Figure 1), with 31 specific items in total. The next paragraphs will elaborate on each item. It is important to stress that, since this protocol intends to provide a flexible framework aimed at reflection and awareness among researchers conducting a game analysis, not all of the following items will be applicable to each specific analysis or required to report in every game analysis manuscript.

Figure 1. Visualization of the DiGAP sections and items. Click image to enlarge.

Section 1: Rationale & Objectives

This section addresses the reasoning why researchers conducted a game analysis and what they hoped to achieve with the analysis, which should provide readers with an initial understanding of the game analysis itself. Items one through four consist of the broad rationale why researchers employed game analyses instead of a different research method (item 1), their specific goal(s) (item 2), which particular research questions they hoped to answer (item 3) and what hypotheses they might have formulated (item 4).

Rationale (item 1)

As with all academic work, it is imperative for researchers to clearly state the rationale behind their game analysis, so readers can comprehend the decision to conduct a game analysis as well as how the results of the analysis contribute to existing work. With this item, researchers can discuss the main reason for or driving force of the game analysis: for example, to provide an in-depth analysis of one specific game or game franchise (e.g., Keogh, 2013), to give an (historical) overview of a broader range of games within a specific genre or type of game (e.g., Gilbert et al., 2021), or to support existing work on players’ motivations, experiences and effects with in-depth game content insights.

Objective(s) (item 2)

While the previous item includes the broader intentions of the researchers to conduct a game analysis, this item consists of the specific objective(s) directing researchers in their analysis. Providing the explicit aim(s) or goal(s) of the analysis aids readers to fully understand the overarching topic of the game analysis. Presenting the analysis’ objective(s) can be very brief and concise. For example, Ford’s (2021) qualitative analysis on the haunting aspect of ancient societies in both the Mass Effect trilogy and The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (Nintendo, 2017) explicitly stated its objective in a separate paragraph, and mentioned some guiding research questions (although they are not explicitly presented as such):

“I explore how these confrontations with the ghosts of the gameworlds in the ME trilogy and BotW shape the player's experience of those gameworlds. What role does spectrality play in these worlds? How is nostalgia evoked for a gameworld's own fictional past?” (para. 5)

Research Question(s) (item 3)

The specific goal(s) of the game analysis can also be formulated as concrete questions the researchers want to examine. Formulating research questions can help accentuate the aim of the game analysis in a more explicit way. For instance, Lynch et al.’s (2016) quantitative work on female game characters posed several specific research questions, including “RQ1: Does the sexualization of playable female characters change over time?,” “RQ2: Does sexualization of female characters differ between games of different genres?” and “RQ4a: Do games feature more primary than secondary female characters over time?” (p. 568).

Hypotheses (item 4)

The final item within the first section deals with formulating specific expectations or hypotheses researchers might have for the game analysis. Mentioning hypotheses is not a common practice within game analyses (compared to survey or experimental research, for instance), and if included, hypotheses are far more common to appear in quantitative analyses. One example of hypotheses in game analysis is that of Gilbert et al. (2021), who analyzed the formidability of male game characters across a broad range of games: “[...], we expect that male characters portrayed with greater physicality (i.e., intense physical action) will appear more formidable than those with lesser physicality (H1)” (p.3).

Section 2: Researcher Background

This section handles all personal researcher characteristics that may impact the game analysis. Items within this section deal with researchers’ styles of playing games and specific game motivations (item 5), researchers’ prior game experiences and mastery of the analyzed games (item 6), their specific socio-demographic background (item 7) and using multiple researchers and coders (item 8).

Orientation/Motivation (item 5)

Previous research showed that player characteristics (e.g., orientations and motivations) can significantly influence players’ preference for certain games and playstyles, some of which are aimed towards very different goals such as achievement, sociability, competition, exploration or immersion (Bartle, 1996; Tondello & Nacke, 2019; Yee, 2006), and offer very different gameplay experiences. For instance, researchers may be drawn towards a certain focus (e.g., aesthetic, cultural, ethical) or playstyle that may not match that of a non-scholarly player (cf. Juul, 2005; Leino, 2012). Hence, researchers ought to be mindful of and report on their personal engagement with a game in order to clarify potential biases (cf. Fernández-Vara’s (2019) exercise/questionnaire entitled “What type of player are you?” (p. 31-33)).

Prior Game Experience (item 6)

While researchers do not have to excel at every game they play in order to obtain valid results (cf. Aarseth, 2003), one could argue for the necessity of experience with the game being analyzed, the genre it is a part of and the medium of digital gaming as a whole. It should be noted that experience goes beyond pure technical skill and mechanical competence, and may also include understanding the game’s aesthetic conventions and principles (e.g., FIFA Ultimate Team (FUT) Packs in the FIFA series that resemble sports trading cards), reception (e.g., FUT Packs’ randomized nature and mechanical affordances met criticism in both media and player communities) and production context (e.g., the inclusion of FUT Packs can be seen as part of publisher EA’s live-service business model) (cf. Kringiel, 2012).

Socio-demographic Background (item 7)

Due to the participatory nature of digital games, researchers cannot avoid influencing the content under analysis (Schmierbach, 2009). For instance, the experience of play may be shaped by researchers’ socio-demographic background, including their ethnicity, gender, nationality, cultural values, academic background and researcher status among others (Barr, 2008). The importance of reflexivity regarding these characteristics is evidenced in the work of El-Nasr et al. (2008), who conducted a multicultural read of Assassin’s Creed (Ubisoft Montreal, 2007) and discovered that different cultural viewpoints and disciplinary backgrounds led to a diversity of readings of the historical blockbuster game: whereas to some researchers with Middle-Eastern origins “the game aroused many nostalgic feelings,” others with a Western background relished its “beautiful architectural detail and environment layout” that allowed for fast parkour gameplay (p.1).

Multiple Researchers (item 8)

To account for a variety of readings and playstyles or to make generalizable claims across different contexts, a game may be played by multiple researchers and/or coders. Given the above-mentioned criteria (i.e., items 5-7), however, special attention should go towards ensuring the validity of findings by establishing iterative discussion within research teams. In addition, quantitative analyses may include measures to maintain intercoder reliability (cf. item 30). According to Schmierbach (2009), researchers may even choose to record gameplay sessions “rather than trying to have players code as they play” (p. 165), which eliminates variance by interactivity, but does not nullify the motivations, orientations, experiences and personal characteristics of the coders themselves. Therefore, it is recommended to describe such background details when working with multiple coders (e.g., Malliet, 2007, who worked with 19 students as part of a seminar to analyze 22 games).

Section 3: Game selection

The current section tackles the matter of how researchers select which digital games to include in their analysis. The section consists of items dealing with describing the chosen game(s) in detail (item 9), clarifying why the chosen game(s) was/were included in the analysis (item 10) and which type of sample the game analysis used (item 11).

Chosen Game(s) (item 9)

As part of standard procedure, the most important information on the game(s) being analyzed should be summarized. This includes the full title(s) of the game(s) (a game may be named differently depending on the region it was released in; cf. item 12), the release dates (if there are multiple, the platform the game is played on may serve as a guideline; cf. item 14), the developer(s), the publisher(s), the genre(s) (when analyzing multiple games, a common source of genre descriptions may be useful; e.g., the MobyGames database), as well as a brief description of the game(s) (e.g., in terms of mechanics, narrative, characters or other aspects that are relevant to the study’s focus). As proposed by Fernández-Vara (2019), researchers may also choose to expand on the game’s technological, socio-historical or economic context, audience and relations to other media.

Rationale for Game Selection (item 10)

When applying a purposive sample (cf. item 11), researchers should describe the rationale for game selection: why is it important to analyze said game(s) with regard to the research objective(s) (cf. item 2) and/or question(s) (cf. item 3)? For instance, in their study on eudaimonic game experiences, Daneels et al. (2021) detailed the criteria that were used to analyze Assassin’s Creed Odyssey (Ubisoft Quebec, 2018), Detroit: Become Human (Quantic Dream, 2018) and God of War (Santa Monica Studio, 2018), being their common possession of “strong emotional narratives, characters and choices,” their “recent, popular and critically acclaimed” nature and shared “diversity of narrative structures and mechanic systems” (p.53).

Sample Type (item 11)

There exists a wide range of sampling approaches ranging from multi-stage cluster sampling to snowball and convenience sampling (e.g., Krippendorff, 2004). In games research, two types of sampling are commonly used: random sampling (e.g., to investigate the prevalence of loot boxes on the Google Play Store, Apple App Store and Steam; Zendle et al., 2020) and purposive sampling (e.g., to investigate how eudaimonic experiences are elicited through narrative and mechanics in a limited number of cases; Daneels et al., 2021). As Schmierbach (2009) remarked, most quantitative game analyses do not draw from truly randomly selected samples, but rather focus on best-selling or most popular games expected to have a wide societal impact. Purposive sampling, then, is conducted on the basis of theoretical relevance and can be inspired by various strategies (e.g., Rapley, 2014): homogeneity (when looking for similar games to find detailed common traits), maximum variation (when looking for communality in vastly different games), deviancy (when looking for rare or unusual games that challenge an idea) and criticality (when looking for games that are likely to yield the most information).

Section 4: Boundaries

The section of boundaries revolves around transparency concerning the exact shape and limits of the analyzed content. The following items each concern a specific aspect about the game and the way in which it was played that may be useful to report in a game content analysis: the date during which and place where the analysis was executed (item 12), the game’s software version (item 13), platform (item 14) and difficulty level (item 15), the mode(s) that was/were played (item 16), the level of engagement with which the game was played (item 17), the degree with which the game was completed (item 18), the in-game choices made by researchers (item 19) and possible forms of unitizing (item 20). Finally, this section discusses whether so-called “meta-ludic texts” (Masso, 2009) were used during the analysis (item 21).

Date and Place (item 12)

The date the analysis was conducted may be relevant to report. Especially in the case of persistent gameworlds (i.e., gameworlds that exist independently from their players on dedicated servers), mentioning the date is important. For instance, the ethnographic analysis of users in Second Life (Linden Lab, 2003) by Boellstorff (2008) was conducted between June 3, 2004 and January 30, 2007, which he described as “the formative years” of the game (p.7). Conducting the same analysis in the current state of the game could produce different research results compared to 2007. Similarly, the place where the game was conducted may impact the analysis: in Belgium, for instance, it is impossible for players to purchase loot boxes with real money (Belgian Gaming Commission, 2018). Regional versions of specific games may, therefore, consist of different content due to foreign censorship policies or changes due to localization (Fernández-Vara, 2019). Malliet (2007), therefore, explicitly mentioned using the Flemish releases of the analyzed games.

Software Version (item 13)

Since games very often receive updates, patches or tweaks after their release, it is important to be aware of the specific software version that researchers engage with (Fernández-Vara, 2019; Malliet, 2007). As Fernández-Vara (2019) noted, knowledge of the game’s software version becomes crucial if the study revolves around persistent virtual environments such as World of Warcraft (Blizzard Entertainment, 2004). In an analysis of the MMORPG The Secret World (Funcom, 2012), Nolden (2020) explicitly recognized that the analysis took place in “the game era before the introduction of the new cultural area of Tokyo” (p.162), referring to the version of the investigated software. Also, if researchers used any modifications or cheats, it is important that these are mentioned to inform readers of the modified state of the game (Fernández-Vara, 2019; Malliet, 2007).

Platform (item 14)

The specific version of a game may change from platform to platform (Fernández-Vara, 2019; Malliet, 2007). Malliet (2007), for instance, recognized that the 2001 PlayStation 2 version of Half-Life (Valve, 1998) adds “a few extra maps, missions and weapons” (para. 27), illustrating the importance of acknowledging the specific platform the game was played on to provide transparency into the specific content that was analyzed. Similarly, Willumsen & Jaćević (2018) discussed the PlayStation 4 controller vibrations of Horizon Zero Dawn (Guerilla Games, 2017) as possible haptic indicators of the protagonist Aloy’s character. This element of meaning is removed when the game is played with mouse and keyboard on PC (for which it was released in 2020).

Difficulty Level (item 15)

The way the difficulty of the game is configured may impact the shape of the text, and therefore influence the object under analysis (Malliet, 2007). For example, Lankoski et al. (2003) wrote how the characterization of Garrett in Thief II: The Metal Age (Looking Glass Studios, 2000) may change depending on the difficulty level, since the expert difficulty level introduces an extra challenge by forcing players to not kill anyone. This means that Garrett will be a different, less violent character when experienced at this level of difficulty, which influences and/or changes the potential results of a characterization study of Garrett.

Mode(s) Played (item 16)

Games may consist of various game modes, and not all modes might be played or needed for the analysis (Fernández-Vara, 2019; Malliet, 2007). Games from the Call of Duty series, for instance, traditionally consist of a single-player story mode/“campaign,” an online and local multiplayer mode (further subdivided in specific match types such as Team Deathmatch, Capture the Flag, etc.) and, since Call of Duty: World at War (Treyarch, 2008), an often-recurring survival zombie mode. Evidently, the analyses by Backe and Aarseth (2013) on zombieism in games and Chapman (2019) on the representation of zombies in historical video games only mentioned the game’s zombie mode.

Engagement Level (item 17)

Aarseth (2003) listed several “strata of engagement” (p.6), ranging from a spectrum between superficial play (the game is only played for a few minutes in order to get an idea of how it works) to innovative play (researchers deliberately adopt varying strategies to test different possibilities in the game system). While it was previously mentioned that researchers have attributed importance to repeated (i.e., the game is played multiple times with potentially different strategies) and innovative play, not every analysis necessarily requires multiple playthroughs to reach the envisioned results, nor does every researcher have the time to do so. In Hitchens’ (2011) quantitative analysis of avatars in 550 first-person shooter games released between 1991 and 2009, the large sample prevented the analyst from playing all of these games to completion. Therefore, “63 games were played in whole, while a further 15 in part” (para. 13), and for others relevant information was acquired through the use of online websites and encyclopedias such as MobyGames.

Mode of Completion (item 18)

Fernández-Vara (2019) rightfully asked when a game is finished, and what it means when researchers declare they have “played the game to completion.” Completion of a game’s main story does not mean that side-quests (which may contain information that is important for the analysis) have been completed too. Similarly, in-game completion milestones (e.g., platinum trophies on PlayStation consoles) do not always require all of the game’s content to have been played. As already explained in item 16, finishing the narrative campaign in games such as Call of Duty does not also mean that the other modes were finished (cf. Fernández-Vara, 2019): Chapman (2019) remarked that the zombie modes generally cannot be finished “in the traditional sense” (p.99), as there is no way for players to triumph over the zombies. Similarly, many games exist without clear, defined endings: in these cases, different methods are necessary to gain a comprehensive view of the game’s content, such as playing the game until a specific level is reached or playing the game for a specific amount of time.

In-game Choices (item 19)

From the moment players participate in a game, they (consciously or otherwise) make choices about what they do and how they behave in the gameworld. Specific in-game choices (e.g., dialogue options that lead to distinct actions) may present different versions of the game without explicit clarification as to what other possible versions look like. Therefore, it is important that researchers are aware of the possible impact of their own choices and/or playstyle upon the actualization of the game (cf. section 2). Researchers should recognize their own individual status as players, not consider themselves as “ideal players” (Fernández-Vara, 2019), and be aware of potential other “implied players” of a certain game (Aarseth, 2007; Zhu, 2015). This awareness may be reached through repeated play (cf. item 17) or through the use of meta-ludic texts (cf. item 21). Aarseth’s (2003) experience with The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind (Bethesda Game Studios, 2002) is a good example of this: unaware of the game’s main storyline, Aarseth reached the final boss of the game but was unable to beat it. Only after looking for solutions online did Aarseth become aware of the missed content due to certain in-game choices, which would have heavily impacted the game analysis.

Unitizing (item 20)

Researchers may subdivide the content of their research object into smaller units for analysis (Krippendorff, 2004). Schmierbach (2009) distinguished three methods of unitizing game content: physical or temporal (i.e., a division of the game without taking into account the game’s structure, such as a fixed time limit), syntactical (i.e., a division into meaningful segments of the game, such as specific game levels) and categorical (i.e., a division into units with specific shared characteristics, such as game characters). For example, Machado’s (2020) analysis of Total War: Rome II (Creative Assembly, 2013) was preoccupied exclusively with its cutscenes and examines the opening and closing cutscenes for the in-game “Battle of Teutoburg Forest” as a case study. This study combined syntactical unitizing (i.e., the analysis of one specific battle) with further categorical unitizing (i.e., the cutscenes within that level). Masso (2009), on the other hand, considered 60 hours per game series a sufficient temporal boundary to analyze World of Warcraft and several games from the Diablo series.

Use of Meta-ludic Texts (item 21)

Masso (2009) conceptualized the term meta-ludic texts as “texts about or in reference to the game but found in other media outside the magic circle of the game” (p. 151-153). Meta-ludic texts or paratexts can be created by the game’s audience (e.g., reviews, game criticism, walkthroughs, wikis, livestreams or blog posts) or its developers (e.g., press releases, developer diaries, app descriptions or update notes). These paratexts become crucial resources to not only gain knowledge of the game’s production context and reception, but also to reveal content, play strategies or gameplay possibilities that researchers may have been unaware of during their own analysis (Fernández-Vara, 2019). In the case of recently released games, meta-ludic texts may even serve as the only textual discussions when academic literature is not yet available. The example of Aarseth (2003) and The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind (cf. item 19) can also be applied here: the researcher consulted online texts on the game to gain awareness of unfamiliar game content. Aarseth said that the best results of game analyses are obtained when this form of “non-playing research” is combined with actual “playing research,” and it is therefore important that researchers give insight into the meta-ludic texts they have used and how these were selected (Fernández-Vara, 2019).

Section 5: Analysis Approach

The current section discusses the elements related to the specific analytical procedure researchers follow. Items within this section deal with whether the analysis was reported as a qualitative or quantitative analysis (item 22), which particular framework or existing methodological approach has been followed, the rationale behind this choice and any deviations from the framework (item 23), which specific dimensions or components were analyzed as part of the chosen framework (item 24) and a single example of a data collection session, such as notes or a recording (item 25).

Qualitative or Quantitative (item 22)

The first step is to indicate whether the data collection followed a quantitative or qualitative methodological rationale. Many analyses do not mention this or use synonyms for “qualitative” and “quantitative”: a qualitative-oriented game analysis is often phrased as a textual or a formal analysis (e.g., de Wildt & Aupers, 2020), while a content analysis is frequently understood as a quantitative-oriented game analysis (e.g., Hartmann et al., 2014). However, textual or formal analyses are specific analytical frameworks to conduct a game analysis (cf. item 23), and a content analysis can be both qualitative and quantitative in nature (cf. Croucher & Cronn-Mills, 2018a, 2018b). The added value of explicitly stating the methodological nature of the analysis is that it immediately indicates which type of data researchers intend to collect with the game analysis.

Analytical Framework (item 23)

An essential aspect of a game analysis is the specific analytical framework used to conduct the analysis in an organized and comprehensible manner. An analytical framework describes the overall approach towards the analysis, and is strongly connected to the specific dimensions or game-related aspects which researchers collect data on (cf. item 24). Some analytical frameworks consist of a specific set of dimensions or game aspects, such as Consalvo and Dutton’s (2006) toolkit focused on four areas (object inventory, interface study, interaction map and gameplay log), Malliet’s (2007) framework incorporating both representational (audiovisual style, narration) and simulational dimensions (e.g., control complexity, game goals and character and object structure), or Hunicke et al.’s (2004) often-used MDA framework (i.e., mechanics, dynamics and aesthetics). Other analytical frameworks provide concrete perspectives on a game analysis. For instance, Cayatte (2017) used a triple framing approach (i.e., narrative, audiovisual and ludic) to study ideological and cultural aspects of digital games. Carr (2019) argued for structural, textual and intertextual overlapping lenses, used specifically for the textual analysis of representations in games. Lankoski and Björk (2015) proposed three important features (i.e., game components, game actions and game goals) as part of the widely employed formal game analysis approach. Finally, analytical frameworks may include more theoretical or philosophical perspectives on digital games. For instance, Bogost (2007) established the notion of “procedural rhetoric” to identify and understand how rule-based representations and interactive images in games are used persuasively. Other examples of such perspectives used in game analyses are Kenneth Burke’s rhetorical pentad situated in dramatism (Bourgonjon et al., 2011), Deleuze’s philosophical concepts as applied to the game Super Mario Galaxy (Cremin, 2012), and Deleuze’s and Guattari’s philosophical notions on rhythm in games (Dupont, 2015) applied to the game Second Sight (Free Radical Design, 2004).

While there are many more analytical frameworks used to study digital games than mentioned in this section, the most important elements to report in a game analysis manuscript are which analytical framework is being followed, the underlying rationale why this framework is used instead of any other approach and any deviations that were made from this framework (for instance, in terms of the included dimensions (cf. item 24) to adapt the framework to the specific needs of a particular game analysis). An example of reporting the analytical framework can be found in de Wildt’s (2020) PhD dissertation on religion in digital games:

I also performed content analyses of several videogames. My way of performing this method would in the Humanities be called a “close reading” or a formal analysis of videogames. Similar to books, film and other intensively analyzed cultural “texts”, this includes a repeated re-reading of the artifact, aided by annotation and supporting research on paratexts [...] and intertexts [...]. (p. 57)

Analyzed Dimensions (item 24)

Related to the specific analytical framework, a transparent game analysis also summarizes the specific dimensions, game-related aspects or components that are being analyzed in the game(s), and clarifies how each dimension is understood in the analysis. Some often-included analyzed elements include the game’s narrative and characters, the audiovisual style (i.e., graphics and soundtrack), controls, interface, objects and specific mechanics unique to a certain game or game genre; most of these are connected to a certain analytical framework (Consalvo & Dutton, 2006; Lankoski & Björk, 2015; Malliet, 2007; Mäyrä, 2008). However, many game analyses add or remove one or more dimension(s) of a specific framework to tailor to the specific needs of the analysis topic as well as the studied digital game(s). For example, Daneels et al. (2021), which used Malliet’s (2007) dimensions, added the component of “in-game choices,” as this was found to be an important aspect for both eudaimonic experiences (i.e., the studied topic in the analysis) and the selected games.

Analysis Example (item 25)

Within this item, an elaborate data collection example could be included in the manuscript to make the game analysis transparent for readers as well as repeatable for fellow interested game analysis researchers. This example could include, among others, a single note-taking session, one codebook entry of a quantitative analysis session, or a recording of a gameplay session. While such an example may be hard to include in a manuscript due to word count restrictions, it can be added as an appendix, as supplementary material (depending on the conference or journal), or can be made available on an open science platform (cf. item 31).

Section 6: Coding Techniques & Data Extraction

The penultimate section of the protocol provides an overview of how researchers process the insights gained from the game analysis. Specifically, it includes the type of data collected (item 26), how the data were coded or structured to reach specific insights (item 27), how the data were extracted after coding or processing (item 28) and potential software that was used to code or process the data (item 29).

Type of Data (item 26)

To identify how researchers approached their game analysis, it is important to mention the gathered type of data. For example, the recording of gameplay is a type of data suggested by various researchers (e.g., Aarseth, 2003; Fernández-Vara, 2019). The advantage of gameplay recordings (over, for example, screenshots or written notes) is that the data obtained closely resemble the game as it was experienced by researchers. For an analysis on the presentation of Socrates in Assassin’s Creed Odyssey, for instance, Vandewalle (2021) compiled a so-called “video game corpus” of relevant game(play) scenes that were recorded while playing the game. Nolden (2020), who recorded gameplay for an analysis of The Secret World, draws attention to the problem with recording game data in terms of researcher influence (cf. section 2): “in documenting my play, I myself am constructing the source material which I will later investigate, thus reducing the degree of freedom inherent in gaming experiences and approximating this medium to that of film” (p.162). An alternative to making one’s own recordings is to analyze gameplay recordings or playthroughs already available online (e.g., videos on YouTube or review websites). Lynch et al. (2016) used this method “to avoid bias in the capturing of the content” (p.569).

Despite these recommendations to use video recordings, other researchers have adopted the practice of coding game content and using numerical data (in the case of quantitative enquiry; e.g., Gilbert et al., 2021) or written notes (in the case of qualitative enquiry; e.g., Daneels et al., 2021) as primary material for analysis. Furthermore, paratexts (cf. item 21) such as messages on discussion boards (Pulos, 2013), game reviews (Ribbens & Steegen, 2012), walkthroughs (Consalvo, 2017) and livestreams (Švelch & Švelch, 2020) have also been proposed as relevant source material. Finally, a combination of the above-mentioned types of data collected for a game analysis is also possible.

Coding Method (item 27)

After obtaining data, it is important to structure the data systematically. In quantitative analyses, a code book is often constructed based on a predefined set of descriptors. Depending on the research goals, this can result in comprehensive information on a game's narrative and mechanics (e.g., Breuer et al., 2012), or in specific information on isolated game components such as characters (e.g., Lynch et al., 2016). In qualitative analyses, several systems for structuring notes have been forwarded, often identifying different components of game analysis frameworks (e.g., Consalvo & Dutton, 2006; Malliet, 2007; Pérez-Latorre et al., 2017) or on conceptual models borrowed from other disciplines (e.g., Bourgonjon et al., 2011). The diary method, which has proved valuable in player-centered research (e.g., Fox et al., 2018), has been suggested as a useful tool to capture researchers’ experience over different moments in time in game analysis research as well (e.g., Daneels et al., 2021). However, mainly in qualitative analyses, this item of structuring data might coincide with extracting information from the data (cf. item 28).

Method of Data Extraction (item 28)

To procure concrete insights as a result of the game analysis, researchers usually apply general research methods that are commonly used in social scientific, psychological or semiotic inquiry. Examples of such manners of data extraction include, among others, quantitative content analysis (e.g., Lynch et al, 2016), discourse analysis (e.g., Ruberg, 2020), rhetorical analysis (e.g., Bourgonjon et al., 2011), critical analysis (e.g., Pérez-Latorre & Oliva, 2019) or narrative analysis (e.g., Perreault et al., 2018).

Software for Data Extraction (item 29)

Some researchers use specific software to convert raw data into structured (cf. item 27) and analyzed data (cf. item 28). For instance, NVivo (or a free, open-source alternative such as QualCoder) can be used for qualitative coding of game notes, while SPSS (or free, open-source software such as JASP or JAMOVI) can be employed to statistically analyze numerical data from more quantitative analyses. It is therefore advisable that authors specify the software package used for data extraction.

Section 7: Reporting & Transparency

Reporting the results of a study is crucial for precisely stating its contribution to scientific knowledge, allowing further developments on this ground and opening the way to verification, replication or comparison and critical improvement of the methodology. Two moments are crucial to these endeavors: first, data coding by multiple researchers raises the question of intercoder reliability (item 30). The second moment involves sharing data and results within the scientific community and society as a whole, which brings up the transparency of the research process, especially in terms of open science (item 31).

Intercoder Reliability (item 30)

Cases where multiple researchers (cf. item 8) participate in the structuration of the data (cf. item 27) by means of a coding scheme raise the question of the intersubjective concordance of their coding process. Intercoder reliability (ICR), in its narrow sense, is “a numerical measure of the agreement between different coders regarding how the same data should be coded” (O’Connor & Joffe, 2020, p.2). As such, it can be used in game analyses by means of a list of features, for which coders decide whether or not they appear (and, in some cases, how many times) in a given sequence or analysis unit (cf. item 20).

ICR calculation is mostly used in quantitative game analysis: examples can be found in Hartmann et al. (2014) or Gilbert et al. (2021). Most game-related studies calculate ICR through Krippendorff’s alpha, although other methods are possible. In reporting ICR, it is advisable to mention at which stage(s) of the analysis ICR occurred, how many codes were used, which portion of the total sample was ICR-checked, which calculation method was used, which result it yielded and which assessment regarding the agreement between coders was made on this basis (cf. Lynch et al. (2016) for an example). If some categories are discarded from the final sample because of low reliability, it should be discussed as well (e.g., Hartmann et al., 2014).

As ICR testing is still a contentious matter in qualitative research (O’Connor & Joffe, 2020), we do not consider ICR as a best practice for qualitative game analyses. However, instead of a numerical confidence measurement, qualitative researchers can interpret ICR and report on it in a broader sense. By following cross-disciplinary recommendations regarding ICR for qualitative content analysis (MacPhail et al., 2015; O’Connor & Joffe, 2020), qualitative game analysis researchers can implement ICR as a process of strengthening agreement within the research team through a collective setup of the methodology, coder training and/or discussion of the coding scheme.

Open Science Transparency (item 31)

Since the 2000s, the push towards transparency in science has largely been embodied in the idea of an “open science,” which promotes the “process of making the content and process of producing evidence and claims transparent and accessible to others” (Munafò et al. 2017, p.5). For our purposes, we understand transparency through open science as the aim of making data, study design and other methodological materials, analysis files and results of each study freely available to readers (Bowman & Spence, 2020) in order to foster easy verification, re-use and improvement of scientific work all along its phases. For game analyses specifically, based on Bowman and Keene’s (2018) layered model of open science, this could mean giving access to prior hypotheses and research design (i.e., pre-registering game analyses), sharing data such as field notes or gameplay recordings as a game corpus (respectful of copyright and editor guidelines; cf. for instance, Ubisoft’s policy on sharing copyrighted material) similar to Vandewalle’s (2021) corpus available on YouTube, providing the analytical framework or specific dimensions (i.e., shared materials) or specific analysis and coding files (i.e., shared analysis). Furthermore, when ethical considerations are necessary, the appropriate documents (informed consent forms, information sheet distributed to participants, etc.) should be added to the report (Barr, 2008). Depending on space constraints, editorial guidelines and publication type, this documentation of the research process can be included in the report itself (e.g., through appendices), in supplementary files, sent upon request by the researchers or made accessible through a link on an external platform such as Open Science Framework (OSF).

While this movement towards open science seems to be mainly focused on quantitative research, open science can also be applied to qualitative research or game analyses to improve transparency, traceability, consistency and comparability instead of replicability (Dienlin et al., 2021). Therefore, common open science practices mentioned before (e.g., sharing materials, data and code, as well as pre-registering analyses) are also appropriate for qualitative research (Haven & Van Grootel, 2019).

Conclusion

While commonly used in the field of game studies, game analysis has proven to be an intricate methodological practice due to the complex nature of digital games as well as the broad range of existing approaches to conduct a game analysis. The Digital Game Analysis Protocol (DiGAP), consisting of 31 items divided into seven categories, proposes a coherent and comprehensive methodological toolkit that (1) guides researchers when conducting a game analysis by raising awareness regarding their own impact on and methodological choices during the analysis as well as (2) facilitates transparent reporting of analysis results. Contrary to prior prescriptive frameworks that dictate a step-by-step method (e.g., Malliet, 2007) or analytical approaches that were developed with a single underlying perspective in mind (e.g., a social-semiotic approach; Pérez-Latorre et al., 2017), the development of DiGAP resulted in a checklist that offers researchers adequate flexibility in terms of their own analysis’ focus.

In the pursuit of flexibility, however, we want to emphasize again that not every item within the protocol needs to be followed or reported in a manuscript, and that the inclusion of a specific item is often dependent on the nature and objective of the analysis at hand. Additionally, the items included are by no means to be treated as conclusive or indisputable, as we do not believe that following this protocol guarantees “objective” quality or certainty of research results. Rather, we welcome scholars to build upon -- or challenge -- this work so that it may yield more insight into the method of game analysis.

The creation of DiGAP has several practical applications. First, as game analyses are more common in game studies compared to other fields that study digital games (such as human-computer interaction or social sciences), DiGAP allows to transfer game analysis methods across disciplinary borders. This means that the protocol may help promote methodological innovations in a wide range of research fields outside of game studies. Second, since DiGAP addresses aspects crucial to game analyses, it might also serve an educational function towards (non-)game scholars intending to analyze digital games (cf. Fernández-Vara, 2019). As such, and in line with Waern’s (2013) view on game analysis as a signature pedagogy for teaching game studies, DiGAP could serve to structure game analysis seminars and to draft larger education programs (e.g., at the entry-level in higher education) with different courses covering different aspects of DiGAP. Similar to Kringiel’s (2012) idea of a “toolbox” consisting of “analytical questions” (p.640) that originated from the scientific research on games, the protocol would thus be able to turn into a didactical toolbox for teaching game analysis; offering a reflexive overview on different research methods rather than an approach rooted in one of them. However, we also want to emphasize that DiGAP can be useful for more experienced game analysis scholars, as it offers them a way to position themselves and their game analysis in a broad range of existing scholarship, and to make their work more accessible to researchers from neighboring fields (e.g., communication and human-computer interaction). Furthermore, it enables researchers to be more mindful of certain strengths and weaknesses of their proven approach to game analysis as well as report on their work in a more transparent manner.

Since DiGAP has been developed only recently, there is no published research yet that has implemented the current guidelines and that could serve as examples of DiGAP in practice. However, several aspects of DiGAP have been used in and are inspired by a broad range of existing game analyses, including work on meaningful and emotional game experiences (Daneels et al., 2021) and dark game design patterns related to monetization and gambling mechanics (Denoo et al., 2021). Finally, the first game analyses using DiGAP are in the works, including for example a master’s thesis on predatory monetization schemes in digital games (Pacek, forthcoming) supervised by the second author of the current paper, which also serves as a prime example of DiGAP’s educational application for scholars new to game analysis. These current and future operationalizations of DiGAP indicate its wide applicability across research topics, fields and methods.

In its current form, DiGAP provides researchers with a comprehensive and flexible methodological toolkit for game analyses that cross-historically synthesizes important previous developments and insights regarding game analysis and methodology. However, since games (and game studies) are continuously evolving, the protocol does not claim to be beyond future modifications. Instead, we want to present DiGAP as a living document, susceptible to updates or new future versions, similar to the PRISMA approach (Moher et al., 2015) from which DiGAP draws inspiration. It is partly due to the flexibility of DiGAP that such future updates may be incorporated into the protocol quite easily, and that the protocol may evolve in ways that run parallel to the developments of the medium it analyzes and the academic field it is a part of.

References

Aarseth, E. (2003). Playing research: Methodological approaches to game analysis. Proceedings of the 5th International Digital Arts and Culture Conference (pp. 1-7).

Aarseth, E. (2007). I fought the law: Transgressive play and the implied player. Proceedings of the 2007 DiGRA International Conference: Situated Play (pp. 130-133). http://www.digra.org/digital-library/publications/i-fought-the-law-transgressive-play-and-the-implied-player/

Aarseth, E. (2021). Two decades of Game Studies. Game Studies, 21(1). http://gamestudies.org/2101/articles/aarseth_anniversary

Backe, H.-J., & Aarseth, E. (2013). Ludic Zombies: An Examination of Zombieism in Games. Proceedings of the 2013 DiGRA International Conference: DeFragging Game Studies (pp. 1-16). http://www.digra.org/digital-library/publications/ludic-zombies-an-examination-of-zombieism-in-games/

Barr, P. (2008). Video game values: Play as human-computer interaction. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Victoria University of Wellington.

Bartle, R. (1996). Hearts, clubs, diamonds, spades: Players who suit MUDs. Retrieved from https://mud.co.uk/richard/hcds.htm

Belgian Gaming Commission. (2018). Research report on loot boxes. Retrieved from https://gamingcommission.paddlecms.net/sites/default/files/2021-08/onderzoeksrapport-loot-boxen-Engels-publicatie.pdf

Bethesda Game Studios. (2002). The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Todd Howard, published by Bethesda Softworks.

Blizzard Entertainment. (2004). World of Warcraft [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Ion Hazzikostas, published by Blizzard Entertainment.

Blom, J. (2020). The dynamic game character: Definition, construction, and challenges in character ecology [Doctoral dissertation, IT University of Copenhagen]. https://pure.itu.dk/portal/files/85357319/PhD_Thesis_Final_Version_Joleen_Blom.pdf

Boellstorff, T. (2008). Coming of age in Second Life: An anthropologist explores the virtually human. Princeton University Press.

Bogost, I. (2007). Persuasive games: The expressive power of videogames. MIT Press.

Bourgonjon, J., Rutten, K., Soetaert, R., & Valcke, M. (2011). From Counter-Strike to Counter-Statement: Using Burke's pentad as a tool for analysing video games. Digital Creativity, 22(2), 91-102. https://doi.org/10.1080/14626268.2011.578577

Bowman, N.D., & Keene, J.R. (2018). A layered framework for considering open science practices. Communication Research Reports, 35(4), 363-372. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2018.1513273

Bowman, N.D., & Spence, P.R. (2020). Challenges and best practices associated with sharing research materials and research data for communication scholars. Communication Studies, 71(4), 708-716. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2020.1799488

Breuer, J., Festl, R., & Quandt, T. (2011). In the army now - Narrative elements and realism in military first-person shooters. Proceedings of the 2011 DiGRA International Conference: Think Design Play (pp. 1-19). http://www.digra.org/digital-library/publications/in-the-army-now-narrative-elements-and-realism-in-military-first-person-shooters/

Breuer, J., Festl, R., & Quandt, T. (2012). Digital war: An empirical analysis of narrative elements in military first-person shooters. Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds, 4(3), 215-237. https://doi.org/10.1386/jgvw.4.3.215_1

Burridge, S., Gilbert, M., & Fox, J. (2019, May 24). On analyzing game content [Conference presentation]. 69th Annual International Communication Association (ICA) pre-conference ‘Games + Communication Ante-Conference’, Washington D.C., USA.

Carr, D. (2019). Methodology, representation, and games. Games and Culture, 14(7-8), 707-723. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412017728641

Cayatte, R. (2017). Idéologie et jeux vidéo: Enquête et méthode. Les cahiers de la SFSIC, 13, 173-182.

Chapman, A. (2019). Playing the historical fantastic: Zombies, mecha-Nazis and making meaning about the past through metaphor. In P. Hammond & H. Pötzsch (Eds.), War games: Memory, militarism and the subject of play (pp. 91-111). Bloomsbury.

Consalvo, M. (2017). When paratexts become texts: De-centering the game-as-text. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 34(2), 177-183. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2017.1304648

Consalvo, M., & Dutton, N. (2006). Game analysis: Developing a methodological toolkit for the qualitative study of games. Game Studies, 6(1). http://gamestudies.org/06010601/articles/consalvo_dutton

Creative Assembly. (2013). Total War: Rome II [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game published by Sega.

Cremin, C. (2012). The formal qualities of the video game: An exploration of Super Mario Galaxy with Gilles Deleuze. Games and Culture, 7(1), 72-86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412012440309

Croucher, S.M., & Cronn-Mills, D. (2018a). Content analysis - Qualitative. In S.M. Croucher & D. Cronn-Mills (Eds.), Understanding communication research methods: A theoretical and practical approach (pp. 161-174). Routledge.

Croucher, S.M., & Cronn-Mills, D. (2018b). Content analysis - Quantitative. In S.M. Croucher & D. Cronn-Mills (Eds.), Understanding communication research methods: A theoretical and practical approach (pp. 175-185). Routledge.

Cuttell, J. (2015). Arguing for an immersive method: Reflexive meaning-making, the visible researcher, and moral responses to gameplay. Journal of Comparative Research in Anthropology and Sociology, 6(1), 55-75. https://doaj.org/article/77796a63d0a249929665770fcdef32e3

Daneels, R., Denoo, M., Vandewalle, A., & Malliet, S. (2022). The Digital Game Analysis Protocol (DiGAP): Facilitating transparency in games research. Proceedings of the 2022 DiGRA International Conference: Bringing Worlds Together (pp. 1-4).

Daneels, R., Malliet, S., Geerts, L., Denayer, N., Walrave, M., & Vandebosch, H. (2021). Assassins, gods, and androids: How narratives and game mechanics shape eudaimonic game experiences. Media and Communication, 9(1), 49-61. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v9i1.3205

Daneels, R., Malliet, S., Walrave, M., & Vandebosch, H. (2019, May 24). Playing the Analysis: Qualitative Game Content Analysis [Conference presentation]. 69th Annual International Communication Association (ICA) pre-conference ‘Games + Communication Ante-Conference’, Washington D.C., USA.

Denoo, M., Malliet, S., Grosemans, E., & Zaman, B. (2021, February 4-5). Dark design patterns in video games: A content analysis of monetization and gambling-like mechanics in pay-to-play, free-to-play and social casino games [Conference presentation]. Etmaal van de Communicatiewetenschap, virtual conference.

de Wildt, L. (2020). Playing at religion: Encoding/decoding religion in videogames [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. KU Leuven.

de Wildt, L., & Aupers, S.D. (2020). Eclectic religion: The flattening of religious cultural heritage in videogames. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 27(3), 312-330. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2020.1746920

Dienlin, T., Johannes, N., Bowman, N.D., Masur, P.K., Engesser, S., Kümpel, A.S., Lukito, J., Bier, L.M., Zhang, R., Johnson, B.K., Huskey, R., Schneider, F.M., Breuer, J., Parry, D.A., Vermeulen, I., Fisher, J.T., Banks, J., Weber, R., Ellis, D.A., … de Vreese, C. (2021). An agenda for open science in communication. Journal of Communication, 71(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqz052

Dupont, B. (2015). Le rythme vidéoludique comme movement: Second Sight et la ritournelle. Interval(le)s, 7, 142-160. http://www.cipa.ulg.ac.be/intervalles7/dupont.pdf

Egenfeldt-Nielsen, S., Smith, J. H., & Tosca, S. P. (2019). Understanding video games: The essential introduction. Routledge.

El-Nasr, M.S., Al-Saati, M., Niedenthal, S., & Milam, D. (2008). Assassin’s Creed: A multi-cultural read. Loading… The Journal of the Canadian Game Studies Association, 2(3), 1-32. https://journals.sfu.ca/loading/index.php/loading/article/view/51

Fernández-Vara, C. (2019). Introduction to game analysis, second edition. Routledge.

Ford, D. (2021). The haunting of ancient societies in the Mass Effect trilogy and The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. Game Studies, 21(4). http://gamestudies.org/2104/articles/dom_ford

Fox, J., Gilbert, M., & Tang, W.Y. (2018). Player experiences in a massively multiplayer online game: A diary study of performance, motivation, and social interaction. New Media & Society, 20(11), 4056-4073. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818767102

Free Radical Design. (2004). Second Sight [PlayStation 2]. Digital game directed by Rob Letts, published by Codemasters.

Funcom. (2012). The Secret World [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Ragnar Tørnquist, published by Electronic Arts.

Gilbert, M., Lynch, T., Burridge, S., & Archipley, L. (2021). Formidability of male video game characters over 45 years. Information, Communication & Society. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.2013921

Guerilla Games. (2017). Horizon Zero Dawn [PlayStation 4]. Digital game directed by Mathijs de Jonge, published by Sony Interactive Entertainment.

Hartmann, T., Krakowiak, K.M., & Tsay-Vogel, M. (2014). How violent video games communicate violence: A literature review and content analysis of moral disengagement factors. Communication Monographs, 81(3), 310-332. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2014.922206

Haven, T.L., & Van Grootel, L. (2019). Preregistering qualitative research. Accountability in Research, 26(3), 229-244. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2019.1580147

Hitchens, M. (2011). A survey of first-person shooters and their avatars. Game Studies, 11(3). http://gamestudies.org/1103/articles/michael_hitchens

Hunicke, R., LeBlanc, M., & Zubek, R. (2004). MDA: A formal approach to game design and game research. In Proceedings of the AAAI Workshop on Challenges in Game AI (pp. 1-5). https://users.cs.northwestern.edu/~hunicke/MDA.pdf

Juul. (2005). Half-real: Video games between real rules and fictional worlds. MIT press.

Karlsen, F. (2008). Quests in context: A comparative analysis of Discworld and World of Warcraft. Game Studies, 8(1). http://gamestudies.org/0801/articles/karlsen

Keogh, B. (2013). Spec Ops: The Line’s conventional subversion of the military shooter. Proceedings of the 2013 DiGRA International Conference: DeFragging Game Studies (pp. 1-17). http://www.digra.org/digital-library/publications/spec-ops-the-lines-conventional-subversion-of-the-military-shooter/

Konzack, L. (2002). Computer game criticism: A method for computer game analysis. Computer Games and Digital Cultures Conference Proceedings (pp. 89-100). http://www.digra.org/digital-library/publications/computer-game-criticism-a-method-for-computer-game-analysis/

Kringiel, D. (2012). Learning to play: Video game literacy in the classroom. In J. Fromme & A. Unger (Eds.), Computer games and new media cultures: A handbook of digital game studies (pp. 633-646). Springer, Dordrecht.

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage.

Lankoski, P., & Björk, S. (2015). Formal analysis of gameplay. In P. Lankoski and S. Björk (Eds.), Game research methods (pp. 23-35). ETC Press.

Lankoski, P., Heliö, S., & Ekman, I. (2003). Character in computer games: Toward understanding interpretation and design. Proceedings of the 2003 DiGRA International Conference: Level Up (pp. 1-12). http://www.digra.org/digital-library/publications/characters-in-computer-games-toward-understanding-interpretation-and-design/

Leino, O.T. (2012). Death loop as a feature. Game Studies, 12(2). http://gamestudies.org/1202/articles/death_loop_as_a_feature

Linares, K. (2009). Discovering Super Mario Galaxy: A textual analysis. Proceedings of the 2009 DiGRA International Conference: Breaking New Ground: Innovation in Games, Play, Practice and Theory (pp.1-2). http://www.digra.org/digital-library/publications/discovering-super-mario-galaxy-a-textual-analysis/

Linden Lab. (2003). Second Life [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game published by Linden Lab. https://secondlife.com/

Looking Glass Studios. (2000). Thief II: The Metal Age [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Steve Pearsall, published by Eidos Interactive.

Lynch, T., Tompkins, J.E., van Driel, I.I., & Fritz, N. (2016). Sexy, strong, and secondary: A content analysis of female characters in video games across 31 years. Journal of Communication, 66, 564-584. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12237

Machado, D. (2020). Battle narratives from ancient historiography to Total War: Rome II. In C. Rollinger (Ed.), Classical antiquity in video games: Playing with the ancient world (pp. 93-105). Bloomsbury Academic.

MacPhail, C., Khoza, N., Abler, L., & Ranganathan, M. (2016). Process guidelines for establishing intercoder reliability in qualitative studies. Qualitative research, 16(2), 198-212. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794115577012

Malliet, S. (2007). Adapting the principles of ludology to the method of video game content analysis. Game Studies, 7(1). http://www.gamestudies.org/0701/articles/malliet

Masso, I. C. (2009). Developing a methodology for corpus-based computer game studies. Journal of Gaming and Virtual Worlds, 1(2), 143-169. https://doi.org/10.1386/jgvw.1.2.143/7

Mäyrä, F. (2008). An introduction to game studies. SAGE Publications.

Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., Stewart, L.A., & PRISMA-P Group (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

Munafò, M.R., Nosek, B.A., Bishop, D.V.M, Button, K.S., Chambers, C.D., Percie du Sert, N., Simonsohn, U., Wagenmakers, E-J., Ware, J.J., & Ioannidis, J.P.A. (2017). A manifesto for reproducible science. Nature Human Behaviour, 1, Article number 0021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-016-0021

Nintendo. (2007). Super Mario Galaxy [Nintendo Wii]. Digital game directed by Yoshiaki Koizumi, published by Nintendo.

Nintendo. (2017). The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild [Nintendo Switch]. Digital game directed by Hidemaro Fujibayashi, published by Nintendo.

Nolden, N. (2020). Playing with an ancient veil: Commemorative culture and the staging of ancient history within the playful experience of the MMORPG, The Secret World. In C. Rollinger (Ed.), Classical antiquity in video games: Playing with the ancient world (pp. 157-175). Bloomsbury Academic.

O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919899220

Pacek, T. (forthcoming). A qualitative content analysis of predatory video game monetization [Unpublished master’s thesis]. KU Leuven.

Pérez-Latorre, O. & Oliva, M. (2019). Video games, dystopia, and neoliberalism: The case of BioShock Infinite. Games & Culture, 14(7-8), 781-800. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412017727226

Pérez-Latorre, O., Oliva, M., & Besalú, R. (2017). Videogame analysis: A social-semiotic approach. Social Semiotics, 27(5), 586-603. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2016.1191146

Perreault, M.F., Perreault, G.P., Jenkins, J. & Morrison, A. (2018). Depictions of female protagonists in digital games: A narrative analysis of 2013 DICE award-winning digital games. Games & Culture, 13(8), 843-860. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412016679584

Pulos, A. (2013). Confronting heteronormativity in online games: A critical discourse analysis of LGBTQ sexuality in World of Warcraft. Games and Culture, 8(2), 77-97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412013478688

Quantic Dream. (2018). Detroit: Become Human [PlayStation 4]. Digital game directed by David Cage, published by Sony Interactive Entertainment.

Rapley, T. (2014). Sampling strategies in qualitative research. In U. Flick (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis (pp. 49-63). SAGE Publications.

Ribbens, W., & Steegen, R. (2012). A qualitative inquiry and a quantitative exploration into the meaning of game reviews. Journal of Applied Journalism & Media Studies, 1(2), 209-229. https://doi.org/10.1386/ajms.1.2.209_1

Ruberg, B. (2020). Empathy and its alternatives: Deconstructing the rhetoric of “empathy” in video games. Communication, Culture and Critique, 13(1), 54-71. https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcz044

Santa Monica Studios. (2018). God of War [PlayStation 4]. Digital game directed by Cory Barlog, published by Sony Interactive Entertainment.

Schmierbach, M. (2009). Content analysis of video games: Challenges and potential solutions. Communication Methods and Measures, 3(3), 147-172. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312450802458950

Slater, M.D. (2013). Content analysis as a foundation for programmatic research in communication. Communication Methods & Measures, 7(2), 85-93. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2013.789836

Švelch, J., & Švelch, J. (2020). “Definitive playthrough”: Behind-the-scenes narratives in let’s plays and streaming content by video game voice actors. New Media & Society. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820971778

Tondello, G.F., & Nacke, L.E. (2019). Player characteristics and video game preferences. Proceedings of the 2019 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play (pp. 365-378). https://doi.org/10.1145/3311350.3347185

Treyarch. (2008). Call of Duty: World at War [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Corky Lehmkuhl and Cesar Stastny, published by Activision.

Ubisoft Montreal. (2007). Assassin’s Creed [PlayStation 3]. Digital game directed by Patrice Désilets, published by Ubisoft.

Ubisoft Quebec. (2018). Assassin’s Creed Odyssey [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Jonathan Dumont and Scott Phillips, published by Ubisoft.

Valve. (1998). Half-Life [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game published by Valve.

Vandewalle, A. (2021, March 5-6). Playing with Plato: The presentation of Socrates in Assassin's Creed Odyssey [Conference presentation]. IMAGINES VII - Playful Classics Conference, Online.

Vandewalle, A. & Malliet, S. (2020). Ergodic characterization: A methodological framework for analyzing games set in classical antiquity. Proceedings of the 2020 DiGRA International Conference: Play Everywhere (pp. 1-4). http://www.digra.org/digital-library/publications/ergodic-characterization-a-methodological-framework-for-analyzing-games-set-in-classical-antiquity/

Waern, A. (2013). Game analysis as a signature pedagogy of game studies. Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games (pp. 275-282). http://www.fdg2013.org/program/papers/paper36_waern.pdf

Willumsen, E.C., & Jaćević, M. (2018). Avatar-kinaesthetics as characterisation statements in Horizon: Zero Dawn. Proceedings of the 2018 DiGRA International Conference: The Game is the Message (pp. 1-4).. http://www.digra.org/digital-library/publications/avatar-kinaesthetics-as-characterisation-statements-in-horizon-zero-dawn/

Yager Development. (2012). Spec Ops: The Line [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Cory Davis and Francois Coulon, published by 2K Games.

Yee, N. (2006). Motivations for play in online games. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 9(6), 772-775. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9.772

Zendle, D., Meyer, R., Cairns, P., Waters, S., & Ballou, N. (2020). The prevalence of loot boxes in mobile and desktop games. Addiction, 115(9), 1768-1772. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14973

Zhu, F. (2015). The implied player: Between the structural and the fragmentary. Proceedings of the 2015 DiGRA International Conference: Diversity of Play: Games - Cultures - Identities (pp. 1-3).