Experiential Play as an Analytical Framework: Empathetic and Grating Queerness in The Last of Us Part II

by Kimberly Dennin, Adrianna BurtonAbstract

2020’s The Last of Us Part II (TLOU2) is a novel site to explicate queer ways of playing and understanding games. We use TLOU2 as a case study to demonstrate how to utilize experiential play in game analysis by adapting methods from other fields, including close play and duoethnography, to explicate and critique resistive queerness. We define experiential play as the embodied experience of a player as a result of the overlapping intersections of a game’s narrative, formal elements, and affective intentions. Resistive queerness is that which resists the dominance of normative understandings of video games. We expose how TLOU2 leverages queerness in its representational, mechanical, and narrative elements and center our analysis of these queer elements in our experience. It is through our experience that we demonstrate how queer representation in TLOU2 serves to make it an empathy machine meant for non-queer players. We suggest that future games studies attuned to questions of diversity must examine AAA games holistically and pay particular attention to nuanced experiences of play, including that of the researcher.

Keywords: video games, queerness, queer game studies, subjectivity, role-playing games, fandom, Naughty Dog, narrative

Introduction

The Last of Us Part II (Naughty Dog, 2020; henceforth TLOU2), created by AAA game development studio Naughty Dog, was widely considered a landmark in diversity and representation because of its lesbian main playable character (PC), Ellie, and her romance with non-playable character Dina. Developers have spoken to the intentional diversity in their stories in several interviews with popular media outlets like Game Informer, BBC and IndieWire (Ehrlich, 2020; Juba, 2020; Takahashi, 2021), concluding that “we need to start telling stories that include everyone” (Powell, 2020). Creative director and narrative lead Neil Druckmann expressed an investment in taking the first dive into diverse casting as a AAA production: “Naughty Dog has had a series of commercial successes, so it allows us to take chances” (Powell, 2020). In an interview with co-narrative lead Halley Gross, Duckmann pinpointed diversity, framing it as a risk they can take:

Our goal is, as a studio, we’re a pretty diverse studio. That’s important. Representation is important to us. We wanted to reflect the diversity of the world we see around us. For us it was about finding ways to have different characters in the game that will have different opinions that can debate, that can stand on different sides of the point. (Takahashi, 2020)

TLOU2 wants to center diversity: they feature many people of color, people with differing ability, people with mental health struggles, and queer and trans people.

As two queer game scholars, we are invested in how AAA games are starting to include and represent more queer characters, and in how prominent dialogues around diversity can oversimplify queerness. We intervened in this process by bringing a duoethnographic approach to our close play. In doing so, we were better able to center our experiences in our analysis. This allowed us to acknowledge that meaningful scholarship is not an affect-less, impersonal endeavor -- and, certainly, neither are games. With our method of experiential play, we better understand the resistive power of the queer representation in TLOU2 in a different way than we would have, had we just focused on close play. While we found that TLOU2 contains queer elements in its representation, mechanics and narrative structure, these elements lack resistive power. Instead, they serve to make TLOU2 an empathetic experience oriented towards a non-queer audience. As such, the game becomes an “empathy machine,” a term used to describe games that allow “players to better empathize with others because they feel like they are ‘really there’” (Ruberg, 2020b, p. 59). Queer representation in TLOU2 loses its resistive power in service of empathy; while the game offers a central lesbian romance and several nuanced queer characters, we find that the game more so acts in the service of non-queer players.

Queer Representations in Video Games

Queerness in video games can be understood as both the representation of queer identities and experiences and also the ways in which they resist the dominance of normative understandings in the industry, which we refer to as resistive power in this article. When examining representations of queerness in games it is important to also analyze their resistive power; often, queer representation in AAA games is a re-skinning of heterosexuality in which there is “no acknowledgement of difference between heterosexual and queer lives, perceived or actual” (Lauteria, 2011, p. 2). For example, Ruberg (2022) shows how Donut County presents hunger that can be sated and straightens things up, which ultimately re-straightens the queer mechanics of the game, thus taking away its resistive power. Similarly, while we found moments of queer representation through the characters, moments of no fun, moments of ludonarrative dissonance and narrative structure in TLOU2, we argue that, rather than holding resistive power, the queer elements instead serve to create an empathy machine.

While there is more inclusion of marginalized people, especially in indie games, games research has long shown a lack of representation of marginalized people in video games (Gardner & Tanenbaum, 2018; Kang & Yang, 2018; Williams et al., 2009). When queer characters are included, their representation tends to mirror queer representation in other forms of media, relying on stereotypes such as Othering, presenting queer characters as villains, removing queer characters’ agency, and sidelining or killing queer characters (Battles & Hilton-Morrow, 2002; Dhaenens, 2013; Kosciesza, 2022; Marshall, 2009; McInroy, 2015). This is especially true for AAA games. For example, Shaw and Friesem (2016) have found that explicitly queer player characters are rare in AAA games; representations of transgender, non-binary, genderqueer, and intersex characters are less common than homosexual or bisexual characters; same-sex relationships are often optional and operate within a heteronormative narrative arc; explicitly queer narratives are the rarest and more often occur in indie games; and, generally, queer content is rooted in homophobia and transphobia. Shaw (2014) also demonstrates that players have complex desires when it comes to queer representation. In her interviews with queer players, she reveals that while most felt that the inclusion of queer representation was important, many were apathetic about whether or not they wanted it, due to either “resignation over never being portrayed” or the fact that “the rare occasions in which they were represented did not resonate” (Shaw, 2014, p. 168). As a response to the frustrating representation of queer characters, research has also identified structural queerness that pushes against hegemonic structures (Lauteria, 2011; Pozo, 2018; Ruberg, 2019).

Moments of structural queerness often reside in the game’s mechanics “that resonate with non-heteronormative experiences of sexuality or gender” (Ruberg, 2022, p. 108). One way that game mechanics are queer is when they offer a form of play that runs counter to normative expectations of play. Examples of this include what Ruberg has called “no fun” (Ruberg, 2015) and instances of ludonarrative dissonance. “No fun” moments are queer in how they resist the normative expectation that, above all else, games should offer a fun experience, as opposed to a reflective or learning experience where players question their motivations in playing the game or broader societal issues (Ruberg, 2015; Ruberg, 2019). “Games are supposed to be fun” is a common response to attempts at addressing complex issues in games, such as the toxicity within the industry and the call for more diversity and representation (Ruberg, 2015). This assumes that there is a universal and “right” way to play games and it involves games being fun. Fun, however, is not universal; it is “cultural, structural, gendered, and commonly hegemonic” (Ruberg, 2015, p. 112). Embracing play and games that are no fun opens the door for more diversity and uniqueness in games (Ruberg, 2015).

Ludonarrative dissonance furthers the concept of no fun by purposefully breaking the player’s immersion in the game. Ludonarrative is the intersection of ludic elements (gameplay) and narrative elements. Ludonarrative dissonance occurs when the ludic and narrative structures of a game do not match, and the player no longer feels immersed (Hocking, 2009). This lack of immersion is queer because it runs counter to the desire to keep players engaged and satisfied. Seraphine (2016) demonstrates how traversal can lead to ludonarrative dissonance. Traversal is when a game becomes a personal experience, thus causing players to have their own expectations of how the narrative is going to play out (Cardoso & Carvalhais, 2013). When the expectations of the player do not match the narrative of the game, the player experiences ludonarrative dissonance. This can lead to the player rejecting the established narrative. Ludonarrative dissonance can be seen as a failure of the game or the player, which leads to feelings of frustration and anger because the game is no longer “fun,” in that expectations do not meet the reality of gameplay. The jarring shift from immersion to ludonarrative dissonance, much like no fun, is queer in that it subverts typical structures and experiences in games. Most AAA titles aim for immersion alone, or for fun alone (Cardoso & Carvalhais, 2013); when experiencing no fun and ludonarrative dissonance, the player is experiencing an out of the norm, queer style of play.

In addition to a queer style of play, games can use resistive power: the potentiality of the representation, mechanics and experience of play combine to push back against the cis- and hetero-normativity pervasive in gaming culture (Burrill, 2008; Downling et al., 2019; Newman & Vanderhoef, 2016). We, the authors, view resistive power in this context to mean the ability of a game to challenge traditional understandings of games as a medium, community and art form. Queer representation is non-normative and meaningful, but the context of it must be examined. For example, queer representation in video games that places diverse characters and mechanics into hegemonic systems serves to reinforce norms that are rooted in cisheteropatriarchy. Queer representation with resistive power resides outside these norms and works against domination. This type of queer representation then becomes a form of queer resistance. Queer resistance refuses to reinscribe problematic politics and norms within a system, or in this case, a game; and instead causes trouble and elicits deviance (Cohen, 2004). Here we highlight trouble and deviance, which we discuss later -- we value the difficult chaos of being marginalized, in gender, race and many other ways of being.

Most queer representation that is also resistive occurs in indie games. Ruberg (2020a) uses the term “queer games avant-garde” to describe a movement of queer game makers that are “creating digital (and analog) games inspired by their own queer experiences” (p. 1). Queer indie games “disrupt the status quo, enact resistance, and use play to explore new ways of inhabiting difference” (Ruberg, 2020a, p. 3). Queer indie game developers are “reimagining video game development itself as a tool for exploring identity, performing cultural critique, and enacting distinctly queer ways of making meaning from the world” (Ruberg, 2018, p. 417). While these types of moves are generally not seen in AAA games, the ways in which these moves approach the inclusion of queer content are complex. Shaw (2009) reveals that “specific concerns of this industry make including GLBT content difficult and shape how the content that does get into games ultimately looks and plays” (p. 248). Given the history of that inclusion and the adherence of the video game industry (intentional or not) to cisheteronormative standards, when a AAA game does include queerness, we must critically examine how the game does so and the degree to which it offers any resistive power.

Games with queer representation can end up not having resistive power because of an emphasis on empathy. Scholars and game designers have called out the problematic ways in which empathy is commonly used to talk about games (Pozo, 2018; Ruberg, 2015; Ruberg, 2020a; Ruberg, 2020b). By asking a player to metaphorically walk a mile in a minority group’s shoes, games oversimplify the complexity of struggle faced by those who are marginalized by the mainstream gaming community. Empathy often is used as a tool to validate games as worthwhile but results in the appropriation and consumption of marginalized experiences while maintaining the underlying assumption that games are for non-queer players to use to make themselves better people (Ruberg, 2020b). Queer games as empathy machines privilege cisgender heterosexual players’ experiences of queerness, instead of the experiences of the game’s queer players and creators (Pozo, 2018; Ruberg, 2020b).

The Last of Us and The Last of Us: Part II in Context

The Last of Us (Naughty Dog, 2013; henceforth TLOU) is an action-adventure game developed by Naughty Dog and published by Sony Computer Entertainment. The game is set in a post-zombie-apocalypse in the United States. We play Joel, a gruff smuggler, who escorts a teenage girl, Ellie, to a group of researchers. Across their journey, Joel and Ellie form a father-daughter relationship. Ellie reveals she is immune to the zombie virus. The researchers she is being delivered to want to study her immunity and develop a possible cure or vaccine. Upon arrival, the scientists inform Joel that the only way to create a vaccine for the zombie virus would likely kill Ellie. The scientists decide to proceed without Joel or Ellie’s consent. The game ends as Joel slaughters a hospital worth of people and takes Ellie out of the hospital, alive.

In 2020’s The Last of Us Part II, players resume as Joel. Joel is quickly killed by the game’s second protagonist Abby, whose father was one of the hospital doctors killed by Joel five years previously. Overcome by grief, Ellie sets out to kill Abby. The game ultimately follows both protagonists’ experiences of loss and revenge. They clash twice in near-death combat, but part ways at the end of the game. In the last scenes of TLOU2, Ellie returns to the home she shared with her girlfriend, Dina, and Dina’s months-old son, JJ. Missing two fingers, Ellie finds the home empty, ambiguously leaves the house, and walks away into the woods.

Throughout the game, Ellie’s identity as a lesbian is marginalized in the context of the broader world. The game begins the morning after a dance where Ellie and Dina share their first kiss. When they kissed, a man at the dance made a homophobic comment toward them, leading Joel to punch him in retaliation. Queerness peripherally occupies a marginalized, othered space in the world of TLOU2. Even in a zombie apocalypse, being queer is different, dangerous and significant.

Recent scholarship on TLOU2 has focused on the construction of femaleness and femininity (Schubert, 2021), moral agency (Anderson, 2022), the importance of paratexts in the series (Banfi, 2022), the response of players to the PC switch (Erb et al., 2021), reactions to Abby’s muscular build (Tomkinson, 2022), players’ understandings of trauma and empathy (Johnson, 2022) and the narrative roles afforded to transgender characters like Lev (Kosciesza, 2022). We are adding to this collection of work by focusing on resistive queer representation using a method that centers our experience as the lens of analysis: experiential play. Within popular sources, game journalist and editor Maddy Myers (2020) has called out TLOU2 for its focus on simple ethical messages, like the cyclical nature of revenge. Myers argues that “the game’s new heroine may give the impression of some larger progressive message, but it’s just a way to change the instruments, if you will. The song itself remains the same” (2020). Despite Druckmann and Gross’ previous statements about wanting to promote diversity, not much has actually changed -- for some of us, at least. We, the authors, are interested in exploring for whom, under what circumstances, and how TLOU2 felt grating, instead of philosophically, morally intriguing, as the designers intended.

Close Play With a Twist

Central to this article is an argument for a focus on affect and experience, particularly that of the researcher. We are expanding a methodological approach to games studies that demonstrates the importance of individuality and nuance in academic investigations of games: experiential play.

In defining experiential play, we draw from Brendan Keogh’s A Play of Bodies (2018). Keogh defines player experience as when the game’s elements (visuals, sounds, input devices, context of play, the player’s ability, etc.) are incorporated into the player’s lived, embodied experience, which has been built from their interaction with “the social world and its constructions of gender, ethnicity, class, and sexuality” (Keogh, 2018, p. 26). Instead of surveying or investigating fans’ reactions and contextual aspects surrounding games, we investigate our own experience with the game as a springboard for future studies in experiential play.

We rely on the concept of close play (articulated by Edmond Chang) -- a methodology, like close reading, that unravels how diegetic and nondiegetic elements in games “are also connected and dependent on the logics, narratives, and histories of the real world” (Chang, 2008; Chang, 2010). As he calls for, we seek to know games beyond their content, narrative, mechanics and graphics; in this article, we “put into practice a kind of interdisciplinarity that is hard” (Chang, 2008; Chang, 2010). To do so, we more concretely meld close reading and ethnography. We utilize Bizzocchi & Tanenbaum’s (2011) method of close reading to identify queer elements of the game and combine it with observational research to ground our analysis of these queer elements in our experience of playing the game. Successfully using close reading methods requires the scholar to oscillate between play as a naive game player and play as a scholar (Bizzocchi & Tanenbaum, 2011). Instead of maintaining those roles in one person, we utilize a duoethnographic approach to split the roles. Duoethnography is “a qualitative methodological approach in which two or more researchers experience and give distinct meaning to a shared phenomenon” (Cifor & Garcia, 2019, p. 2). Kimberly played the game for the first time (play as a naive game player) while Adrianna documented observation notes (play as a scholar), as they had played the game before. The purpose of the observation notes was twofold: to track moments of significance to us during play -- which were vital in identifying moments of queerness during our post-play review of the notes -- and to record each researcher’s experiences during the game, including direct quotes. Drawing on these notes enables us to analyze our experience, which is central to our proposed experiential play framework.

We argue that individual, unique experiences from people with diverse identities are worthy of consideration especially when diverse identities, such as queerness in this case study, are traditionally overlooked, ignored and pushed aside. Other scholars have demonstrated the utility of close readings/play and the importance of utilizing experience in analysis (Harper, 2017; Jennings, 2018; Phillips, 2017). The minutiae of the complex lived experiences of those from marginalized communities, often with a multiplicity of identities, must be explored, considered and critically discussed as games studies expands as a field itself.

What follows is what we, as queer scholars, identified queer elements, such as narrative moments and procedural tools, and an investigation of how our experiences informed our interpretation of these elements in TLOU2. Looking at games holistically and understanding the player’s positionality allows scholars to understand where and how queerness is operating in a game, and how that queerness pushes against heteronormativity. We are particularly attuned to how experiential play creates a unique tension between our lived and our personal experiences. These tensions stretch across our experiences as queer games players and scholars and our positionality within a larger games culture. The usefulness of this framework can be seen in Kimberly’s experience with the project. They came in expecting to use close play to identify queer elements of the game beyond representation, thus supporting the argument that TLOU2 is a queer game. But analyzing the queer elements based on our experience instead revealed that we experienced the game as an empathy machine more than anything else. While it was meaningful to see a lesbian sex scene in a mainstream title, queerness in the game was more often far away -- a feeling that these moments were intended to give non-queer players an understanding of queerness. Instead of centering resistive power, TLOU2 adheres to the cisheteronormative standards embedded in the games industry.

Representation in Play

The revelation of Ellie’s identity as a lesbian in the DLC was a groundbreaking moment for games. The same is true for two other representationally queer characters introduced in TLOU2: Abby and Lev. Sian Tomkinson (2022) critically considers players’ misogynistic reactions to Abby in relation to her genderqueerness. Aiden Kosciesza (2022) interrogates trans representation in three role-playing games, which includes Lev. Even NBC News (2020) showcased the studio’s trans representation in the game and with Lev’s voice actor. However, we are more interested in the resistive power of the game writ large, outside of representational queerness and transness. We both experienced the importance of representation with our coming out journeys, looking to characters like Ellie for a sense of normalcy. However, there is more to queer representation than just being able to count the number of queer people. Ellie being an explicitly queer woman in gaming was important to both of us -- but the continued complexity of queerness as she became an adult in TLOU2 faltered.

TLOU2’s lack of complexity in part stems from the lack of consideration for Ellie’s own coming out journey, as depicted in the DLC. Left Behind has two main settings: several weeks before the events of TLOU, and during a wintertime skip featured in TLOU. Left Behind centers around Ellie’s relationship with Riley, a Black girl she grew up with in an orphanage. Ellie and Riley become romantically involved during Left Behind. Riley and Ellie are infected by zombies; Riley dies, while Ellie learns that she is immune to whatever virus has caused the zombie apocalypse. In the section of the game that explores the time skip in TLOU, Ellie deals with her grief over Riley while tending to an ill Joel.

We also find it vital to think critically about Riley’s positionality as a Black girl in The Last of Us. We turn to TreaAndrea Russworm’s consideration of the DLC. Russworm (2017) reveals how “Ellie needs her black friend, Riley, to teach her how to be more confident, exploratory, and politically subversive. The empathetic relationship between these two characters is constructed as essential for Ellie and as one that has uneven consequences for Riley” (p. 112). Russworm concludes that, overall, the game includes representation, but not what we are terming resistance: “blackness nonetheless functions unimaginatively and unprogressively in this dystopian narrative frame that is so primed for social and political commentary” (Russworm, 2017, p. 113). Russworm makes this lack of resistance clear for race, while we are making a similar argument for the representation of queerness. Although outside the scope of this article, there is also a need to consider queer people of color in AAA titles like TLOU2.

In TLOU2, Riley is notably not alluded to or mentioned. TLOU2 references a previous girlfriend of Ellie’s, Cat, but makes no mention of Riley. Through Riley’s absence, we find it unlikely that the game is attempting to obscure Ellie’s queerness, given the explicitness of her relationship with Dina. Whether simply a small oversight, or a purposeful decision made to separate the DLC from the main series entirely, the omission of Riley in TLOU2 takes away this pivotal relationship, a moment of coming out and bravery. We felt this omission because of the influence that our own coming out journeys have had on our lives. After coming out, Kimberly spent years coming to terms with her identity which involved battling internalized homophobia and discovering who she wanted to be. Adrianna had a strong internal sense of self, but faced pushback and harm from her family and friends at the time. Coming out is a flash point that influences many queer peoples’ lives and yet it is something that was noticeably omitted in Ellie’s story. For a game centered around Ellie’s journey with loss and guilt, why is the first person she lost left behind?

Mechanics of Play

As a zombie apocalypse game focused on exploring Ellie and Abby’s trauma and grief, TLOU2 does not shy away from situations that are meant to cause feelings of discomfort and no fun. These moments are impossible to avoid unless the player chooses to stop playing. TLOU2 invokes feelings of no fun in a variety of ways, including cutscenes, background elements and gameplay. For example, the player and Ellie are forced to watch as Abby murders Joel. A less direct example of no fun is when playing as Abby, Kimberly came across her dog Alice. Earlier in the gameplay when playing as Ellie, she had killed Alice. Temporally, this moment of Abby is set before Ellie kills the dog. In response to seeing Alice, Kimberly sadly noted “That’s my dog I killed.” This was an extreme juxtaposition to Kimberly’s earlier feelings in the game when she expressed a sense of joy and accomplishment at successfully killing the dogs as Ellie. In our case, these feelings of sadness and no fun did not make us want to stop playing the game, and to some degree, are simply important to the genre of the game, and is not inherently queer.

Still, experiencing no fun forced us to think critically about what we were seeing and the actions we were forced to take as players. These examples demonstrate how TLOU2 puts players in situations where they are supposed to feel a mess of feelings that have nothing to do with “fun,” which in turn offers players opportunities to reflect on their gameplay. We experienced these moments as queer because, instead of just accepting the norms of the game, they made us think critically about the actions that we had been taking. There is, however, something to be said about the mobilization of no fun in TLOU2. Ultimately, these queer moments are still just moments and, like Shaw (2009) found in her examination of GLBT content in games, these moments still operate within a game that mostly adheres to normative notions of AAA games. Where the game diverges from normative design are in the experiences of ludonarrative dissonance.

Moments of ludonarrative dissonance most often emerge in instances where agency is taken away from the player. Ludonarrative dissonance goes beyond no fun in that the player is deeply unsettled by what is occurring in the game and no longer wishes to continue playing. As the following examples will show, this line between dissatisfaction (no fun) and wanting to quit playing (ludonarrative dissonance) is a key distinction for ludonarrative dissonance. One of our first encounters with ludonarrative dissonance did not have much to do with the narrative of the game. Playing as Ellie, we were looting an apartment when a group of people attacked. After killing most of them, there is one person left who stops attacking and begins to beg with Ellie, saying “please, you don’t have to do this!” Both of us were very intrigued by this statement and decided to back off and let the character live. Once we did this, however, the non-playable character (NPC) immediately returned to attacking Ellie and we were forced to kill him to progress in the game. Both of us expressed displeasure at this turn of events, finding it frustrating that our actions clearly did not matter. However, discovering this within the game was still fun -- we enjoyed learning something odd about the development of the game, although we disagreed with our lack of meaningful choice. It was not a very strong moment of ludonarrative dissonance, but it drew us out of the immersion of the game.

Another, more important experience of ludonarrative dissonance occurs when we (as Abby) caught up in time to where we had left off playing Ellie. As Abby, we had to chase down and attack Ellie, in an attempt to kill her. When Kimberly realized that she had to fight Ellie, she stopped playing as Abby. She instead stated that she could not attack Ellie, so what was she supposed to do in this part? Even after accepting that she had to attack Ellie to progress through the game, Kimberly died multiple times (as Abby) and expressed intense dissatisfaction with having to play through this part. Given that Kimberly went so far as to stop playing to grapple with what the game was asking, we found this to be a striking moment of ludonarrative dissonance.

The game uses moments of ludonarrative dissonance to challenge prioritizing immersion. But what happens when we linger varies by person -- hence the need for an experiential play framework. Together, we took a break from the game to process what was happening. Kimberly attested they would have taken a break anyways. Yet when Adrianna first played the game, they powered through the whole thing in one or two sittings and then rage-screamed with a friend.

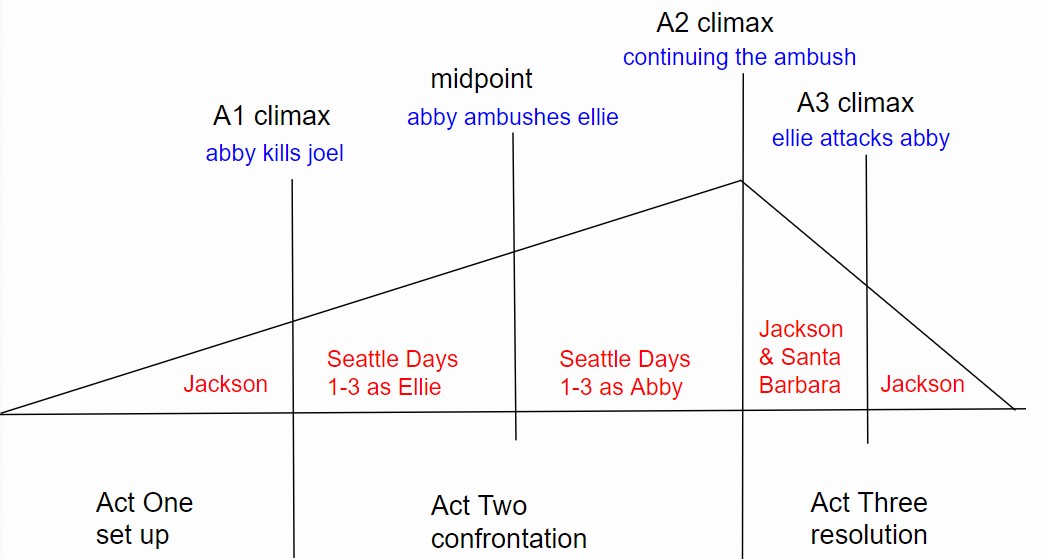

The last mechanical element of the game that we examined as a potential for queerness was its narrative. TLOU2 may appear to push back against traditional storytelling structures in its use of time skips and multiple PCs, but we found that it still closely follows the traditional three act structure, as seen in Figure 1. The following paragraphs break down the narrative moments that denote changes between acts, often in the style of cutscenes where either the PC or temporal setting changes.

Figure 1. Three Act Structure in TLOU2. After playing TLOU2 and completing coding of observation notes, Adrianna aligned key moments from the game onto a standard map of the three-act structure. In black text are standard elements found in all three-act structures. In blue text is the description of the climaxes or midpoint. In red text are descriptions of the content occurring during each act, up to the signified climax or midpoint. Click image to enlarge.

While Act 1 was certainly sad, as we experienced the death of Joel, the overall experience fits within the ludic structure of the game. Act 2 as a whole rapidly increased in dissatisfaction experienced by us. It is also in Act 2 where our experiences of the game differed the most, specifically in regard to switching from playing as Ellie to Abby. Initially, we were distraught by Joel’s murder, in love with Dina, and excited to jaunt through the wilderness like seasoned zombie killers. When the player’s control switched to Abby, however, we experienced different levels of ludonarrative dissonance. Despite having played the game over a year ago, Adrianna still felt very strong feelings towards Abby and her actions in game and asked Kimberly to throw Abby off a cliff a few times to reconcile her feelings of ludonarrative dissonance. Contrastingly, Kimberly was excited to learn Abby’s backstory and get to know her character, saying that she could not “quite hate her as much as I want to.” Kimberly did eventually experience moments where she was upset about playing Abby, making statements like “What did she think was gonna happen? Joel killed Abby’s dad, and Abby tracked him down for how many years? And she literally heard Ellie begging and screaming like Abby literally was.”

These outbursts were more common and did not stop after a brief period of adjustment for Adrianna, which was an experience shared by a non-negligible portion of the game’s fan base. At the time of this writing, there are close to a million views on a 10-minute compilation of Abby dying (Calloftreyarch, 2020; OmarAH1, 2020). Adrianna is likely responsible for at least 10 of those views. At the time of the game’s release, the compilation had around 400,000 views. Players were upset about Abby for many reasons. A significant portion of fans expressed misogynistic views towards Abby’s gender presentation, including her body shape and lack of typical femininity. Fans also blindly aligned against Abby in defense of Joel, refusing to engage further with complexity. When trailers of the game were first airing, Adrianna was very excited about Abby because the character was voiced by one of their favorite actors and Abby did not fit into gender normative standards. Adrianna aligned their disdain for Abby to their intense sense of identification with Ellie, who is Abby’s foil in many ways. This intense emotion remained a year later. After completing the game, Adrianna said that they disliked both Abby and Ellie to the same degree -- a significant blow to her considering Ellie was a queer and empowering character she loved.

In our experience, as detailed by the counting of moments of no fun and ludonarrative dissonance in Table 1, we were more impacted by the game’s fixed narrative for Ellie than for Abby. Playing Abby was not fun, while playing Ellie was traumatizing and high in dissonance.

|

Ellie |

Act 1 |

Act 2 |

Act 3 |

|

No Fun |

1 |

3 |

5 |

|

Ludonarrative Dissonance |

0 |

5 |

7 |

|

Abby |

Act 1 |

Act 2 |

Act 3 |

|

No Fun |

0 |

5 |

0 |

|

Ludonarrative Dissonance |

0 |

3 |

0 |

Table 1. No Fun and Ludonarrative Dissonance by Character and Acts. Here we tally moments of no fun and ludonarrative dissonance as detailed by our duoethnography.

Many AAA titles fit within a three-act story structure, which often aligns with other storytelling structures like the hero’s journey. Players know what to expect, particularly from a highly narrativized, stylized and mainstream series such as TLOU. Storytelling mechanics in TLOU2 overall follow normative structures, falling into step with conventions typical of other AAA action games. By applying experiential play to this game, however, we found non-negligible queerness at play because of our application of no fun and ludonarrative dissonance to explain moments of discomfort.

By noting what moments felt bad, weird, anger-inducing and/or meta-critical, we were able to identify what about those moments felt uncomfortable and why -- which did not always fit into the categories of no fun or ludonarrative dissonance. These moments were accompanied by externally directed emotion from the players, such as statements like “we’re going home now, right???” by Kimberly, which were tracked in the field study notes by Adrianna and coded jointly by both researchers. These also include moments when Kimberly paused the game to express frustration, ask questions, or take a deep breath. Instances when Kimberly expressed general frustration were not coded as no fun. For example, Kimberly remarked: “I can’t believe Jesse’s dead. Why, he was so good. And nice. He’s not gonna meet his kid. Dina never got to tell him that she’s pregnant. Ugh.” These types of expressions were noted as no fun or ludonarrative dissonance, depending on their context. In a more personal moment with Jesse stemming from Kimberly’s relationship with her dad, she exclaimed: “See, this is very rude of the game because I like him a lot and he’s a funny dad.” In this moment, Kimberly was both actively critiquing the game and engaging with a deeper personal experience, the Researcher’s relationship with their dad, whereas the first example statement was a general frustration. The moments in Table 1 denote places of immense frustration, where we wanted to stop playing the game -- seriously stop, beyond that of a regular rage quit.

These moments of no fun and ludonarrative dissonance are extremely subjective and dependent upon the players’ individual experiences. By centering these individual experiences, we show the potential of experiential play to reveal unexpected engagements with an experience that were not necessarily intended by developers. This framework can broaden the type of experiences and stories that are reflected back into the mainstream production of games.

Experience of Play

Up to this point we have been examining the elements of TLOU2 where there is queer representation and analyzing its effectiveness individually. Resistive power is not just about effective queer representation, though; to dig into the potential resistive power of the game, we find it vital to analyze our experience in context with the queer elements of the game. These queer elements -- no fun, ludonarrative dissonance, queer characters -- are generally not experienced separately as unique, discernible moments outside of the larger context of the game. Using our field notes and observations, we were able to separate out particular moments that contributed to what we were feeling. In order to understand the resistive power of queer representation in the game, we present our analysis by binding together the queer tools present in representation and mechanics with our experience of the game’s third act. In playing through and reflecting upon the third act of the game, we were able to more clearly understand the complicated mesh of queer representation up to that point. We found that the queer elements of the game lack resistive power, and are therefore not a form of queer resistance, because our experience of these elements emphasized mostly the pain and trauma of being queer. It instead served as an empathy machine, offering a way for a non-queer audience to claim an understanding of traumatic queer experiences.

When closely playing, reading, and experiencing TLOU2, we wanted to find moments of resistance and empowerment as queer players, even within a tragic, post-apocalyptic setting. We kept in mind Cathy Cohen’s (2004) suggestion that resistance by Black and marginalized people may not have been “attempts at resistance at all, but instead the struggle of those most marginal to maintain or regain some agency in their lives as they try to secure such human rewards as pleasure, fun, and autonomy” (p. 38). Ellie’s sexual orientation pushes back against many of the ways queer people have been historically represented. Ellie does not experience victimization because of her queerness and is certainly not sidelined. She also does demonstrate a certain amount of agency by making vital decisions for herself, like when she decides to leave Dina and JJ to hunt down Abby at the end of the game. This agency resides within the character, not the player. The player is, as Cohen suggests, not experiencing resistance facilitated by the game; they are left behind, left without autonomy. There is debate as to how much agency games afford players (Cardoso & Carvalhais, 2013; Ruberg, 2019; Shaw, 2014), but in highly structuring the game and Ellie’s story, TLOU2 takes away all sense of player agency in a way that proves more harmful than helpful for some players. The representation of Ellie as a queer character, supposedly full of agency, and our experiences as queer players lacking any form of agency created the most significant moments of ludonarrative dissonance in Act 3.

Act 3 starts with the player as Ellie experiencing domestic farm life with her girlfriend Dina and Dina’s son, JJ. After some gameplay, Ellie’s uncle reveals that he has found Abby. He encourages Ellie to go after Abby again and does not offer to join, since he is injured from their last fight. Initially, Ellie refuses to go. That night, Ellie sneaks out of bed and reflects on her loss. Kimberly assumed that Ellie was about to leave to hunt down Abby, so she yelled “back to bed!” and brought Ellie back to the room in an attempt to get her to go back to bed, in an outright refusal to follow the game’s narrative. Realizing this was not an option if she wanted to keep playing the game, Kimberly then delayed as much as possible. She wandered around the house, expressing her disapproval of the decision Ellie was going to make and saying she wanted the game to end at this moment before anything else could happen. This was the moment we felt the most significant lack of agency and the most significant amount of ludonarrative dissonance.

When Ellie does find Abby, she ultimately decides to let her live. And when Ellie returns to the farm, Dina and JJ are gone. The game then switches to a flashback cutscene: a memory from Ellie’s perspective on the night before Joel is killed. Ellie, for the first time in years, tells Joel that she cannot forgive him for his actions from the first game, but that she is willing to try. This is a tender moment, but we experienced it as a moment that glosses over the queer tragedy that Ellie is currently experiencing.

By continuing the story after Ellie’s life on the farm, after Act 3, the queer narrative becomes one of queer suffering and pain as opposed to queer joy and a representation of queer family. Then, by focusing the narrative back on Joel, the queer narrative is lost. Queer people’s lived experiences often do include suffering and pain, but in this moment, the only experience we received was a very familiar tragic ending. There were many moments when Kimberly tried to prevent Ellie from doing something that was written into the narrative or just put down the controller to try to delay the inevitable. We spent time investigating every (empty) corner of the theater before being forced to leave Dina alone, pregnant, and maybe-protected. Moments like these are when we found the game sour.

Yet Ellie’s journey with trauma and grief are powerful storylines. Her agency to make choices, even choices that further her own trauma, is a vibrant representation of the complicated lives of queer peoples. However, the queer experience of play in TLOU2 is one that replicates forms of trauma that queer people already experience. This comes from the ludonarrative dissonance which emerges from the disconnect between the character’s agency and lack of player agency in making decisions that result in tragic outcomes they do not feel they have control over. In thinking through agency and trauma, we turn to Hill Malatino (2022):

It’s alright that we’ll be processing trauma for the rest of our lives; it’s to be expected, and it’s from and through that collective processing that we’ll be most able to approximate anything close to radical transformation, anything that remotely resembles healing. The only way around it is straight through. (p. 197)

Here we put emphasis on collective processing -- the frustration, screaming and crying we experienced as a duo playing TLOU2 that was strikingly, harmfully lacking for Adrianna’s first playthrough. After our experience with the game, we began to question Ellie’s agency. To see a queer person have the capability to make a bad choice is immensely powerful, and representative of lived experience. As someone with invisible mental health disabilities, Adrianna began to reflect on her experience with coming out and depression. Developers’ interviews with VentureBeat spoke to this tension. Narrative lead Halley Gross talked more directly about Ellie’s agency:

Ellie doesn’t have a choice. Whatever’s going on internally, whether or not she has hesitation, she is compelled to continue forward, even as she might know that she should stop, or even as she might know she should stay home with Dina, or even as she might know this will hurt. She has lost herself to this addiction. (Takahashi, 2020)

This lack of choice -- this addiction to revenge, the overwhelm of her PTSD -- undermines their goal to represent queer characters on the world stage, in a AAA capacity. Stephen Johnson (2022) considers PTSD and the player-character relationship, concluding that the game confronts players with their own understandings of trauma. We are all for complex characters with more than one axis of marginalization going on in their lives, but was this the space for that kind of complexity, confrontation and re-traumatization? We are not suggesting a clear-cut answer to this question, or even the simple addition of content warnings at the beginning of the game; instead, we call on others to use experiential play and center their voices, their experiences and to give themselves a little more agency.

Framing TLOU2 as providing an empathetic experience only serves to reinforce the assumption that the game is not made for queer people. In playing the game, we did not want to have our agency as players taken away -- as agency so often is outside of video games for queer and marginalized people -- and we did not want to feel empathy for Ellie’s tragic story. Our experience emphasized that in Ellie’s story, there is no pushing back against anything that is heteronormative -- we experienced the exact opposite, falling into familiar beats and patterns of tragic queerness. In our play, we found empathy grating and redundant. We are empathetic towards queer struggle -- we live queer struggle. For Adrianna, there was anger towards any inclination of empathy for Ellie; instead of feeling for Ellie, they were feeling as Ellie, given their pre-existing identification with the character. We wanted to see her settle down with her girlfriend Dina and live a happy, queer life. Whenever the game became stressful, and engaged with other emotions linked to no fun, Kimberly would monologue about how Ellie needed to forget about Abby and go start a farm with Dina. What we received, however, was a game that ultimately provided an empathetic experience meant to put a non-queer audience into queer people’s shoes. TLOU2 can appear as a game that encourages empathy in a general sense through its surface-level representation, but doing so does not encourage queer resistance. We are not calling for oversimplified games with happy endings; instead, we prioritize a critical focus on what happens when queer narratives are only tragic and encourage empathy in spaces where they are already minorities.

We are also interested in new questions and goals for game development. What if TLOU2 were made for queer people alone, without providing an empathetic experience for a heteronormative audience? What other experiences of play do queer people have in playing TLOU2, besides ours? What would it mean for different experiences to be ones of queer resistance? For us, queer resistance in play would invoke an experience that embodies the complexities of queerness instead of using queerness as a lesson for heteronormative audiences. While queer resistance has been embraced by many queer indie game developers, TLOU2 demonstrates how the developers of AAA games include queer representation and diversity, to echo Druckmann’s interviews, which ultimately do not contain resistive power.

The Last of Us Part II: Left Behind

The story and mechanics in TLOU2 gives its players an overall sense of queerness: queer people are people with complicated and unique lives. While developed by queer designers and artists, TLOU2 played like a game made for straight players who could benefit from simple queer representation. The game felt, from our perspective, more akin to tragedy porn -- meaning a spectacle of suffering meant to be consumed by an outside audience for enjoyment. Ultimately, for us, the game proved disappointing and retraumatizing. We left the game feeling lost, instead of hopeful. Just as in the case of Riley, we felt that our experiences were used as an empathy machine -- to deliver a message we had already learned by just being queer.

Our decision to introduce experiential play significantly changed how we understood queerness in the game, and in our debriefing of our experience in play we were very resistant in a way that we had not been while playing; we flung ourselves against the game and the larger hegemonic structures at work in gaming. By lingering to think critically about our experience, we found some generative push-and-pull. Ellie’s ‘father’ accepts and defends her, and we experienced joyful moments with her partner. We find that TLOU2 attempts to, overall, present a hopeful version of being queer. While we appreciated this message, our experience of queer resistance in the game ended with the end of Act 2.

As players, we are two queer people who have struggled with coming out. In our lives, queerness has not always been normalized, empathized, or accepted. In taking our experiences into our analysis, we understood how queerness operates in TLOU2 in a way that we would not have, had we just focused on representation and mechanics. To us, meaningful scholarship is not an affect-less, impersonal endeavor -- and, certainly, neither are games. In both spaces, experientiality should be central. However, we are not providing the one and only queer experience of TLOU2. Our work is limited in the ways that we are limited; there are perspectives, identities and experiences we will never have. Other scholars, players and creators can and should add their voices to this conversation.

Even within our similar lived experiences, there were moments where we differed in how we experienced the same parts of the game. There is value in showing a personalized experience of a game and in acknowledging differences -- it is in difference that diversity thrives. Future works should center the experiences of a game’s wide array of players and introduce an experience-focused methodology, whether or not that utilizes duoethnography like this article does. Experiential play should be messy, much like queerness. As queer people who have experienced the types of marginalization and trauma Ellie experiences, we call for a fight against the media and industry’s pacifying attempts at representation. We are here -- we have always been here, and queer -- and it is past time for those traditionally marginalized in games to carve out and reshape the mainstream space. Ellie is queer, but it is time for a wider variety of queer stories. Where are queer characters thriving in games? Because TLOU2 fails to offer these experiences to queer players, we do not consider our queer experience of play to be one of queer resistance. We are not calling for a buttoned-up, happy ending for all queer characters; we are yearning for better -- for developers, players and researchers to think about all types of diversity by first centering their and others’ unique experiences.

Acknowledgements

Both authors share co-first authorship and acknowledge that they have contributed equally to this research. Kimberly Dennin https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5081-0824 Adrianna Burton https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5635-177X We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

We would also like to thank Bo Ruberg, PS Berge, and Evin Groundwater for their tremendous help in proofing this manuscript before submission. This research was supported by the Tabletop Researchers in Practice (TRiP) collective and the Critical Approaches to the Technological and Social (CATS) Lab at the University of California, Irvine and, both of which provided formative feedback and support during the research and writing process. We are grateful to the wonderful editorial team at Game Studies.

References

Anderson, K. (2022). Moral distress in The Last of Us: Moral agency, character realism, and navigating fixed gaming narratives. Computers in Human Behavior Reports 5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100163

Banfi, R. (2022). Ellie’s journal: Para-Narratives in The Last of Us Part II. Game Studies, 22(3). http://gamestudies.org/2203/articles/banfi

Battles K., & Hilton-Morrow W. (2002). Gay characters in conventional spaces: Will and Grace and the situation comedy genre. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 19(1), 87-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/07393180216553

Bizzocchi, J., & Tanenbaum, T.J. (2011). Well read: Applying close reading techniques to gameplay experiences. In D. Davidson (Eds.), Well played 3.0: Video games, value and meaning, pp. 289-313.

Burrill, D. A. (2008). Die tryin’: Video games, masculinity, culture. Peter Lang.

Calloftreyarch. (2020, June 20). The Last Of Us Part II - Abby Death Montage [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Scf1ebr4qc

Cardoso, P., & Carvalhais, M. (2013). Breaking the game: The traversal of the emergent narrative in video games. Journal of Science and Technology of the Arts, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.7559/citarj.v5i1.87

Chang, E. (2010, November 11). Close playing, a meditation on teaching (with) video games. ED(MOND)CHANG(ED)AGOGY. http://www.edmondchang.com/2010/11/11/close-playing-a-meditation/

Chang, E. (2008). Gaming as writing, or, World of Warcraft as World of Wordcraft. Computers and Composition, Special Issue: Reading Games. http://cconlinejournal.org/gaming_issue_2008/Chang_Gaming_as_writing/index.html

Christou, G. (2014). The interplay between immersion and appeal in video games. Computers in Human Behavior 32, pp. 92-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.11.018

Cifor, M., & Garcia, P. (2019). Gendered by Design: A Duoethnographic Study of Personal Fitness Tracking Systems. ACM Transactions on Social Computing, 2(4), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1145/3364685

Cohen, C. (2004). DEVIANCE AS RESISTANCE: A new research agenda for the study of Black politics. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 1(1), 27-45. doi:10.1017/S1742058X04040044

Dhaenens, F. (2013). The fantastic queer: Reading gay representations in Torchwood and True Blood as articulations of queer resistance. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 30(2), 102-116. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2012.755055

Dowling, D. O., Goetz, C., & Lathrop, D. (2019). One year of #GamerGate: The shared Twitter link as emblem of masculinist gamer identity. Games and Culture, 15(8), pp. 982-1003. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412019864857

Erb, V., Lee, S., Doh, Y.Y. (2021). Player-character relationship and game satisfaction in narrative game: Focus on player experience of character switch in The Last of Us Part II. Front Psychol, 12(709926). doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.709926

Ehrlich, D. (2020, June 22). Neil Druckmann and Halley Gross open up about the biggest twists of ‘The Last of Us Part II’. IndieWire. https://www.indiewire.com/2020/06/the-last-of-us-part-ii-interview-neil-druckmann-halley-gross-spoilers-1234568597/

Gardner, D. L., & Tanenbaum, T. J. (2018). Dynamic Demographics: Lessons from a Large-Scale Census of Performative Possibilities in Games. Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3173667

Gautam, P. (2021, July 16). How to use the three act structure for game design. Game Dev Academy. https://gamedevacademy.org/three-act-structure-game-design-tutorial/

Harper, T. (2017). Role-play as queer lens: How “ClosetShep” changed my vision of Mass Effect. In B. Ruberg & A. Shaw (Eds.), Queer Game Studies. University of Minnesota Press.

Hocking, C. (2009). Ludonarrative dissonance in bioshock: The problem of what the game is about. In D. Davidson (Eds.), Well played 1.0: Video games, value and meaning, pp. 255-262.

Jennings, S. C. (2018). The horrors of transcendent knowledge: A feminist-epistemological approach to video games. In K. L. Gray & D. J. Leonard (Eds.), Woke gaming: Digital challenges to oppression and social injustice. University of Washington Press.

Johnson, S. M. (2022). “Go. Just take him.”: PTSD and the Player-Character Relationship in The Last of Us Part II. Games and Culture, forthcoming, OnlineFirst. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120221139216

Juba, J. (2020, June 1). The Last of Us Part II interview - Adding depth, staying grounded, and the cost of revenge. Game Informer. https://www.gameinformer.com/preview/2020/06/01/the-last-of-us-part-ii-interview-adding-depth-staying-grounded-and-the-cost-of

Kang, Y., & Yang, K. C. C. (2018). The Representation (or the Lack of It) of Same-Sex Relationships in Digital Games. In T. Harper, M. B. Adams, & N. Taylor (Eds.), Queerness in Play. Palgrave Macmillan.

Keogh, B. (2018). A play of bodies: How we perceive videogames. The MIT Press.

Kerner, A., & Hoxter, J. (2019). Theorizing stupid media: De-naturalizing story structures in the cinematic, televisual, and videogames. Springer Nature.

Kosciesza, A. J. (2022). The moral service of trans non-player characters: Examining the roles of transgender non-player characters in role-playing video games. Games and Culture, 18(2), pp. 189-208. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120221088118

Lauteria, E.W. (2011). “Procedurally and fictively relevant”: Exploring the potential for queer content in video games. Berfrois, pp. 1-13.

Malatino, H. (2022). Side affects: On being trans and feeling bad. University of Minnesota Press.

Marshall, D. (2009). Popular culture, the ‘victim’ trope and queer youth analytics. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 23(1), pp. 65-85. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518390903447176

McInroy, L.B. (2015). Perspectives of LGBTQ emerging adults on the depiction and impact of LGBTQ media representation. Journal of Youth Studies, 20(1), 32-46. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2016.1184243

Myers, M. (2020, June 12). “The Last of Us Part 2 review: We’re better than this.” Polygon. https://www.polygon.com/reviews/2020/6/12/21288535/the-last-of-us-part-2-review-ps4-naughty-dog-ellie-joel-violence

Naughty Dog. (2013). The Last of Us [Sony PlayStation 3]. Digital game directed by Neil Druckmann & Bruce Straley, published by Sony Computer Entertainment.

Naughty Dog. (2020) The Last of Us: Part II [Sony PlayStation 4]. Digital game directed by Neil Druckmann, Anthony Newman & Kurt Margenau, published by Sony Interactive Entertainment.

Newman, M. Z., Vanderhoef, J. (2016). Masculinity. In Wolf, M. P., Perron, B. (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Video Game Studies, pp. 380-387. Routledge.

OmarAH1. (2020). You know your story is a big fail when one of the most important plot points is to get people on Abby’s side and yet videos like this exist on YouTube [Online forum post]. Reddit. Accessed May 1, 2022. https://www.reddit.com/r/TheLastOfUs2/comments/ho41ki/you_ know_your_story_is_a_big_fail_when_one_of_the/

Phillips, A. (2017). Welcome to my fantasy zone: Bayonetta and queer femme disturbance. In B. Ruberg & A. Shaw (Eds.), Queer Game Studies. University of Minnesota Press.

Powell, S. (2020). The Last of Us Part 2: Creators say diversity in games ‘essential’. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/newsbeat-53080982

Pozo, T. (2018). Queer games after empathy: Feminism and haptic game design aesthetics from consent to cuteness to the radically soft. Game Studies, 18(3). http://gamestudies.org/1803/articles/pozo

Rosenblatt, K. (2020, July 8). “‘The Last of Us Part II’ brings queer stories to a pandemic-ravaged dystopia.” NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/last-us-part-ii-brings-queer-stories-pandemic-ravaged-dystopia-n1233073

Ruberg, B. (2015). No fun: The queer potential of video games that annoy, anger, disappoint, sadden, and hurt. QED: A Journal in GLBTQ Worldmaking, 2(2), pp. 108-124. https://doi.org/10.14321/qed.2.2.0108

Ruberg, B. (2017). The arts of failure: Jack Halberstam in conversation with Jesper Juul moderated by Bonnie Ruberg. In A. Shaw & B. Ruberg (Eds.), Queer Game Studies, pp. 201-210.

Ruberg, B. (2018). Queer indie video games as an alternative digital humanities: Counterstrategies for cultural critique through interactive media. American Quarterly 70(3), 417-438. doi:10.1353/aq.2018.0029.

Ruberg, B. (2019). Video games have always been queer. New York University Press.

Ruberg, B. (2020a). The queer games avant-garde: How LGBTQ game makers are reimagining the medium of video games. Duke University Press.

Ruberg, B. (2020b). Empathy and its alternatives: Deconstructing the rhetoric of “empathy” in video games. Communication, Culture and Critique, 13(1), 54-71. https://doi.org/10.1093/CCC/TCZ044

Ruberg, B. (2022). Hungry Holes and Insatiable Balls: Video Games, Queer Mechanics, and the Limits of Design. JCMS: Journal of Cinema and Media Studies, 61(3), 107-128. https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2022.0026

Ruberg, B., & Phillips, A. (2018). Not gay as in happy: Queer resistance and video games (Introduction). Game Studies: Special Issue -- Queerness and Video Games, 18(3). http://gamestudies.org/1803/articles/phillips_ruberg

Russworm, T.M. (2017). Dystopian blackness and the limits of racial empathy in The Walking Dead and The Last of Us. In: Nakamura, L. et al. (Eds.) (2017). Gaming Representation (pp. 109-128). Indiana University Press. muse.jhu.edu/book/55233

Schubert, S. (2021). Playing as/against violent women: Imagining gender in the postapocalyptic landscape of The Last of Us Part II. Gender Forum, 80, 30-54.

Seraphine, F. (2016). Ludonarrative dissonance: Is storytelling about reaching harmony? Frederic Seraphine. https://www.fredericseraphine.com/index.php/2016/09/02/ludonarrative-dissonance-is-storytelling-about-reaching-harmony/

Shaw, A. (2014). Gaming at the edge: Sexuality and gender at the margins of gamer culture. University of Minnesota Press.

Shaw, A. (2009). Putting the Gay in Games: Cultural Production and GLBT Content in Video Games. Games and Culture, 4(3), 228-253. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412009339729

Shaw, A., & Friesem, E. (2016). Where is the queerness in games?: Types of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer content in digital games. International Journal of Communication, 10, 3877-3889.

Shaw, A., & Ruberg, B. (2017). Imagining queer game studies. In A. Shaw & B. Ruberg (Eds.), Queer game studies, (pp. ix-xxxiii). University of Minnesota Press.

Shepard, M. (2014, April 29). Interactive storytelling - Narrative techniques and methods in video games. University of Southern California. https://scalar.usc.edu/works/interactive-storytelling-narrative-techniques-and-methods-in-video-games/the-three-act-structure

Sipocz, D. (2018). Affliction or affection: The inclusion of a same-sex relationship in The Last of Us. In Harper, T., Adams, M., Taylor, N. (Eds.) Queerness in Play. Palgrave Games in Context. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90542-6_5

Takahashi, D. (2020, April 28). Naughty Dog’s narrative lead explains the story of The Last of Us Part II. GamesBeat. https://venturebeat.com/games/how-naughty-dog-wove-diversity-into-so-much-of-the-last-of-us-part-ii/

Tanenbaum, T. (2021). INF 190 / ICS 80 Storytelling for Interactive Media. The Transformative Play Lab at the University of California, Irvine. https://transformativeplay.ics.uci.edu/storytelling-for-interactive-media/

Tomkinson, S. (2022). “She’s built like a tank”: Player reaction to Abby Anderson in The Last of Us: Part II. Games and Culture, 18(5), pp. 684-701. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120221123210

Williams, D., Martins, N., Consalvo, M., & Ivory, J. D. (2009). The virtual census: Representations of gender, race and age in video games. New Media & Society, 11(5), 815-834. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444809105354