Let’s not be Cultural Pessimists: The Social Construction of Nintendo’s Game Boy and the Need for Console-Specific Game Studies

by Jesper VerhoefAbstract

In the 1990s, handheld game consoles, Nintendo’s Game Boy in particular, took the world by storm. By means of a grounded theory informed discourse analysis, this article examines the social construction of handhelds in Dutch media. After briefly sketching the immense popularity of Game Boys, particularly with children, it demonstrates that depictions of handhelds differed markedly from concurrent popular discourses about video games abroad as well as from Dutch discussions about the Walkman. Handhelds, and in their wake video gaming, did not cause moral panic in the Netherlands. To the contrary, they were met with a surprisingly moderate, unperturbed response. These findings, it is argued, call for a different approach to study popular discourses. Game histories should not presuppose that there was one public opinion about video games and gaming. Instead, we should be open to the possibility that different consoles elicited different reactions, which might have spilled over into the evaluation of gaming.

Keywords: handheld game consoles, Game Boy, Game Gear, popular discourse, public debate

Introduction

When Nintendo introduced the Game Boy in 1989, it was an instant hit. The handheld was “a juggernaut” (Kent, 2001, p. 416), which had video games become “part of mainstream culture” (Wesley & Barczak, 2010, p. 79). In the 1990s, it became the most popular game system of all time up to that point: Nintendo sold over 110 million units and more than 450 million cartridges (Kent, 2001, p. 590). The Game Boy is part and parcel of our recent cultural heritage (cf. Zeiler & Thomas, 2021).

Given its impact, the dearth of research into the Game Boy and other 1990s handhelds is startling. This likely owes to the US-centeredness of many game histories. It is for instance acknowledged that compared to the United States, the Game Boy “was huge in Europe, much bigger than the NES” (Ryan, 2012, p. 105; cf. Sheff, 1993, p. 414). Yet since most studies focus squarely on the United States, handhelds are usually the cursory side dish to the main course: the history of home consoles.

There are some exceptions to the lack of scholarly attention. One study shows how the human body played a key role in the development of the Game Boy (Reynolds, 2016). Additionally, in a recent volume of the MIT book series Platform Studies, Alex Custodio scrutinizes the Game Boy Advance (GBA), shedding light on how the GBA functioned as both a computational system and a cultural artifact. Welcome as this is, it is remarkable that the series does not yet include a volume on its iconic predecessor, the Game Boy -- all the more since Custodio stresses that the GBA was a legacy medium which, unlike the Game Boy, “wasn’t groundbreaking” (Custodio, 2020, p. 7). A recent Game Boy monograph is not available in English (Gorges, 2019).

This article helps fill this research lacuna. Using a grounded theory informed discourse analysis of print and broadcast media, I analyze media coverage of handhelds in the Netherlands from 1990 through 2000. In 1990 the first handhelds (Atari’s Lynx and the Game Boy) entered the Dutch market; 2000 marks the final year before the Game Boy Advance was introduced, the first “true upgrade” (Ryan, 2012, p. 207) of the Game Boy. In essence, the Game Boy remained the same throughout the 1990s.

My analysis of the popular image of handhelds adds to the small body of literature that shows how video games and gaming were constructed and evaluated in the press. Its objective is to expand this strain of research. My focus on the Netherlands is a response to the compelling plea to bring location into game history. To date, this history has chiefly focused on the United States, as remarked above, Japan and the UK (Kirkpatrick, 2012; Wade & Webber, 2016, p. 2). However, as Melanie Swalwell rightly notes:

Game history did not unfold uniformly and the particularities of space and place matter. Given the great historic diversity of games and contexts for their play, an appreciation of socio-cultural and geographic specificity is important to develop, particularly if other histories are to be told, for instance, from the ‘periphery’ rather than the ‘centre.’ (Swalwell, 2021b, p. 3)

Consonant with Swalwell’s plea, my article goes beyond offering a history from the periphery. Moreover, it also helps “the field of game history get out from under the weight of received wisdom” (Swalwell, 2021a, p. 231). In short, I oppose the idea -- prevalent in extant studies, based on press coverage in other countries -- that in the 1990s the popular press predominantly cast video gaming in an extreme light, either celebrating its utopian potential, or, more frequently, disparaging it in dystopian fashion. My article arrives at the opposite conclusion. In the Netherlands during the 1990s, the Game Boy was not perceived as a social or cultural threat, nor was video gaming. Rather, both were conceived of as non-problematic.

This divergent representation, I argue, should be cause for more specific research into the social construction of gaming. Extant studies tend to document media coverage of video games and gaming in toto. This approach obscures that different consoles -- be they home consoles or handhelds -- targeted different audiences, were used differently and had different libraries of games. Consequently, they likely were constructed differently, which might have spilled over into depictions of video gaming. Hence, game histories should not merely do the idiosyncrasies of different localities justice; they should also do justice to specific consoles.

In so doing, this article meets the objection that research into new technologies, including that into popular discourses about video games, usually ignores “the previous research on the previous medium of popular consumption” (Wartella & Reeves, 1983, p. 8) and studies them in isolation. I will compare Dutch media discourses on handhelds to those on another popular contemporary, portable technology: the Walkman. After all, both journalists and scholars (e.g. Custodio, 2020, pp. 121-123; Herman, 2008, p. 145; Wesley & Barczak, 2010, p. 83) have used the Walkman to frame the Game Boy, for both were popular private portable technologies. Between its introduction in 1980 and the mid-1990s, the Walkman in the Netherlands was met with strong cultural pessimism (Verhoef, 2022). The device was thought to emblematize and promote contemptible individualization. The press scolded Walkman users, predominantly comprising teenagers, for indulging in consumerism, inconsiderateness and escapism in the form of insulation. Contrasting media imaginaries of handhelds with those of the Walkman helps to foreground my aforementioned conclusion.

Since scholars have shown that representations of video gaming reveal preexisting “powerful cultural codes and worldviews” (McKernan, 2013, p. 309), in the discussion I will relate my findings to the wider socio-cultural history of the Netherlands and try to account for the prevailing, unruffled response of handhelds and video gaming.

Literature Review

To put public discourse about handhelds in perspective, this literature review first discusses extant studies regarding the construction of gaming in the popular press, and subsequently outlines the position that video gaming occupied in the Netherlands in the 1990s.

Social Construction of Video Games

Scholars have abundantly shown that new technologies offer an apt means to study the desires, anxieties and preoccupations of societies (Sturken et al., 2004; regarding the Netherlands, see Verhoef, 2016; 2017). A small body of literature demonstrates that video games and consoles, too, can be conceived of as “the bellwether” of cultural transitions (Egenfeldt-Nielsen et al., 2016, p. 2). My article adds to studies that analyze how consoles and games were represented in popular discourses.

The archetypical study of this kind is Williams’s analysis of US news magazines’ coverage of gaming between 1970 and 2000. He concludes: “Consistent with prior new media technologies video games passed through marked phases of vilification followed by partial redemption.” (Williams, 2003, p. 543). In the 1990s, dystopian frames -- spurred by the 1993-1994 Mortal Kombat congressional hearings, in which game violence was chastised, as well as by high school shootings -- “highlighted fears of video games’ [detrimental] effects on values, attitudes and behaviour and a rise in the language of addiction” (Williams, 2003, p. 541). At the same time, utopian frames concurrently held that video games would build intelligence and familiarity with computers -- that is, foster techno-literacy.

Discourse analyses conducted since William’s study have reiterated that the popular press tends to (re)produce extreme viewpoints and moral panic. Evaluative New York Times’ articles published in the 1990s, for example, predominantly denounced video games as a major social threat, especially to children, for they allegedly promoted violent behavior. At the same time, a smaller number praised them, as they were believed to “foster athletic prowess, promote technological literacy, and offer an educational supplement” (McKernan, 2013, p. 325). More recent publications highlight that the “moral panic zeitgeist that marks the media blame game” (Maclean, 2016, p. 33) was neither specific to the late-twentieth century press coverage of video games, nor to the United States (Cao & He, 2021). Moreover, moral panic over video games and gaming surfaced in media other than the written press, too, such as in newscasts (Bigl & Schlegelmilch, 2021) and Hollywood films and television advertisements (Narine & Grimes, 2009) -- sometimes offset by equally extreme utopian visions.

As indicated in the introduction, I propose to expand this strain of research, addressing three current deficiencies. First, most studies rely on English-language sources (see also Parrott et al., 2020; Wirman, 2016). However, as gaming is always “imbued in a variety of ideological and cultural contexts” (Nicoll, 2017, p. 204), it is imperative to analyze popular discourses outside the Anglophone world, too, and compare findings (Swalwell, 2021a, p. 227).

Second, most scholars referenced in this section comprise their corpora by means of generic keyword searches, using terms such as “video games” and “computer games.” It is implied or flatly asserted that such queries yield “all the game-related reports” (Cao & He, 2021, p. 447). This is questionable, as some news items do mention the name of a console, yet do not use generic terms. Focusing on representations of a particular (type of) console does not make good on the promise of an all-encompassing overview, either. Rather, I argue that such promises should not be made in the first place. The referenced works presuppose that there was one public debate about video games, gaming or “video game culture” (Shaw, 2010). They preclude the possibility that different consoles were met with divergent responses, which, in turn, might have affected opinions about gaming per se. After all, a “substantial portion of the context for discourse about video games is shaped by the devices we use and how they are conceived of as technical, cultural, and social objects” (Paul, 2012, p. 82) A more limited scope, then, might enrich game studies, as it does justice to the specificity of (discourses about) each console.

Third, even though some scholars acknowledge that the reception of video games bears resemblance to that of other media, they fail to take the next step: to contextualize their findings by explicitly contrasting them with popular discourses about other contemporary media. As mentioned in the introduction, I will use the public debate about the Walkman as a reference point in this study.

Gaming in the Netherlands

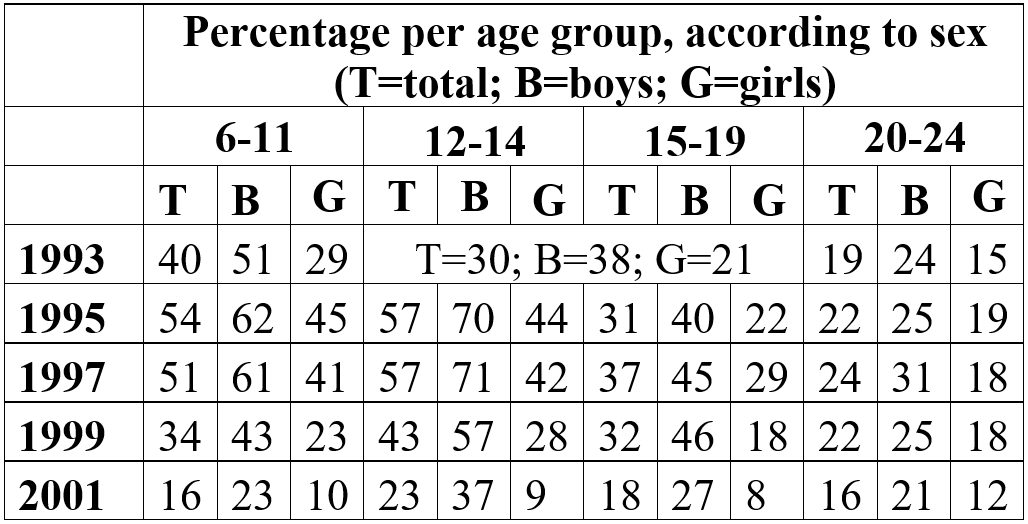

There is little data on gaming in the Netherlands in the 1990s. A representative biennial survey presented ownership of game consoles among youth from 1993 onwards (Jongeren, 1993; 1995; 1997; 1999; 2001), though it did not distinguish between different consoles. Table 1 shows that gaming was particularly popular with boys; declining percentages in the second half of the decade were caused by the rise of personal computers.

Table 1. Percentage of Youth that owned a Game Console, broken down by Age and Sex, 1993-2001.

No comparable figures are available for the entire population.

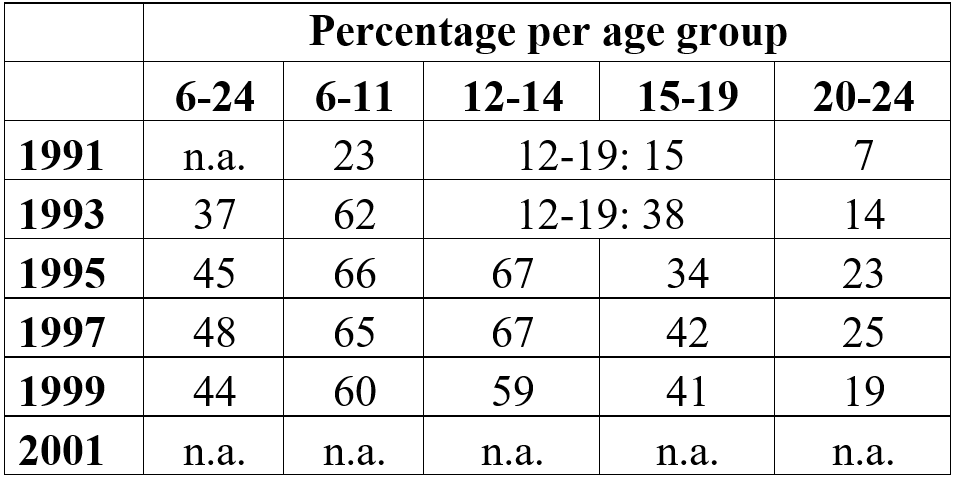

The Youth survey also recorded the percentage of youth that played computer games. Consistent with table 1, table 2 indicates that games were especially popular with children up to 14, unlike the Walkman, whose prime audience consisted of 15- to 19-year-olds.

Table 2. Percentage of Youth that played Computer Games, broken down by Age, 1991-2001.

Other contemporary publications attested to the importance of the Game Boy in children’s lives. Unlike Nintendo’s other consoles, researchers explicitly singled out the Game Boy in their questionnaires (e.g. Beentjes et al., 1999). The “lightning fast” increase of video games’ popularity was even directly attributed to its introduction (Nikken et al., 1999, p. 1). Interviews conducted in 1997 with a representative group of 6- to 17-year-olds indicated that a little over one out of three children, slightly more boys than girls, had a Game Boy (Beentjes et al., 1999). As my analysis will suggest, it arguably had been even more popular in the first half of the decade, when no research into ownership and usage was carried out.

Interestingly, in the 1990s some Dutch scholars justified research into gaming by referring to public discourse. They contended that “in the news, video games are more frequently ascribed an alleged negative influence than a positive influence” (Nikken et al., 1999, p. 29). Such claims, however, were not substantiated. Later studies, too, only alluded to Dutch public debates about gaming in the 1990s (e.g. Veraart, 2011, p. 62). To date, these have not been mapped.

Material and Method

I have studied popular discourses about handhelds through three types of sources. Newspapers comprise the most important source. The years 1990 through 1994 are covered by the digitized Dutch newspaper archive Delpher (Delpher.nl), which shows articles as they were printed. As Delpher offers scant information concerning the years thereafter, Nexis Uni -- which does not include visual information -- is consulted for the years 1995 through 2000. There are only minor differences in the composition of both corpora; both represent the vast majority of newspapers that were read. A search query containing the specific names of available handhelds (Lynx, Game Boy, Game Gear, Supervision, Neo Geo Pocket) in combination with generic references such as “handhelds” or “pocket computers” was composed and iteratively refined. Subsequently, false positives were removed. This resulted in 183 articles regarding 1990 through 1994, and 340 articles regarding 1995 through 2000 [1]. Table 3 shows the distribution.

|

Year |

Articles |

|

1990 |

8 |

|

1991 |

19 |

|

1992 |

33 |

|

1993 |

61 |

|

1994 |

62 |

|

1995 |

34 |

|

1996 |

27 |

|

1997 |

31 |

|

1998 |

39 |

|

1999 |

64 |

|

2000 |

145 |

Table 3. Number of Newspaper Articles about Handhelds, 1990-2000.

The peak in 1999 and 2000 stems from the Pokémon craze. The vast majority of these articles glossed over the Game Boy, thematizing the general fad -- which also comprised Pokémon television shows, cards, t-shirts and other paraphernalia -- instead, a topic which falls outside the scope of this article. In general, articles in the second half of the 1990s more frequently than those in the first half mentioned handhelds in mere passing. The Results section will reflect this focal point.

The largest national news magazine, Elsevier, forms the second source. It published seven articles mentioning handheld consoles.

Radio and television shows constitute the third source. The audiovisual archive of The Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision offers access to the majority of broadcasts [2]. The above query results in twenty news items.

To analyze this data, I applied a grounded theory informed discourse analysis. A discourse analysis “is a careful, close reading that moves between text and context to examine the content, organization and functions of discourse,” which acknowledges that the result is “an interpretation, warranted by detailed argument and attention to the material being studied (Gill, 2000, p. 188). I close read the articles in newspapers and magazines and “close listened/viewed” and transcribed radio and television broadcasts. I first coded as inclusively as possible. Subsequently, I scrutinized the data an additional three times to establish patterns and refine and integrate categories. Finally, I interpreted the findings.

These steps bear close resemblance to the three phases of a grounded theory approach. Since discourse analysis and grounded theory are complementary methods, I combined them (cf. Shaw, 2010). The result is a constructivist grounded theory approach, which examines how and why meanings are constructed. Though it concedes “that the resulting theory is an interpretation” (Charmaz, 2006, p. 130), it tries to explain findings, which I will do in the discussion.

Results

Coverage of handhelds did not differ per outlet: there was a clear public opinion. The following subsections discuss dominant themes, which means they do not offer an exhaustive overview. As media barely documented, much less discussed, technical details of handhelds (cf Arsenault, 2017, p. 49; for Game Boy specifications, see Reynolds, 2016), this topic for example will not feature in my analysis. Consistent with Dutch market shares and public discourse, the analysis will focus on the Game Boy rather than other handhelds. Additionally, since Dutch media conceived of the various types of Game Boys, such as the Game Boy Pocket and Color, as one-and-the-same, this article will not differentiate between its various incarnations.

The first subsection sketches the immense popularity of handhelds. The second subsection outlines how handhelds were mostly used by children and were discursively constructed as a toy. These subsections serve as a necessary backdrop for the final one, which shows that the evaluation of handhelds was remarkably moderate and acceptive, especially when compared to 1990s popular discourses about video gaming abroad and concurrent Dutch debates about the Walkman.

Popularity

“Dear editors,” wrote three boys in 1991, “a burglar has taken 80 guilders and the Game Boy (worth 200 guilders). Please return the Game Boy, you can keep the money” (“G&G,” 1991). This letter to the editors indicates the important position the handheld quickly came to occupy in the lives of many. The Game Boy, the press noted, spread like an oil spill.

Though Nintendo did not disclose specific numbers per country, Dutch Game Boy sales can be surmised from press coverage. On average, well over 100,000 devices were sold per annum. Sales peaked in the years following the device’s release and later, due to the Pokémon craze, in 1999 and 2000. In 1998 one million Game Boys had been sold, a figure that amounted to more than twice as many NES consoles and thrice as many Super NES consoles that Nintendo sold along comparable timelines. Though Walkmans were in considerably higher demand, this number is still impressive given that the Netherlands in the 1990s had about fifteen million inhabitants, of which about 1.7 million fell in the main target group (see next sections) of 6- to 14-year-olds [3].

Nintendo dominated the Dutch market. Going by the press, the Game Boy decimated its competitors. Atari’s Lynx was only mentioned a couple of times. Sega’s Game Gear held up slightly better after it hit Dutch stores in 1992, yet was barely mentioned after 1993. Newspapers acknowledged Nintendo’s dominance using words such as “absolute ruler,” “lord and master,” and “monopolist.” The Game Boy was Nintendo’s “flagship” and “milk cow.” Trying to push its CD-i, even Nintendo’s short-lived competitor Philips acknowledged the Game Boy’s supremacy: “The PC is for the study, the Game Boy for the bedroom of the kids and the cd-i for family entertainment in the living room” (Van Gruijthuijsen, 1993).

Media also allowed Nintendo to consistently stress the Game Boy’s market dominance. In 1992, Nintendo claimed to have a market share of 81 percent. Six years later, the head of Nintendo Netherlands overstated that “almost every family has one” (Escher, 1998).

Scholars disagree as to why the black-and-white, backlight-less Game Boy outperformed its full-color competitors in the marketplace. Energy efficiency, a more competitive price, marketing, children’s familiarity with Nintendo and the quality of games, Tetris (Bullet-Proof Software and Nintendo, 1989) in particular, probably all factored into its success (Custodio, 2020, pp. 34-37; Kent, 2001, pp. 415-419; Ryan, 2012, pp. 103-106; Sutherland, 2012, p. 19; Wesley & Barczak, 2010, pp. 80-81). The Dutch press, however, was not interested in this issue. Only a handful of articles briefly offered possible explanations. In the late 1990s, when Nintendo had long outperformed its competitors, one article had the head of Nintendo Netherlands recall: “Our competitor Sega introduced its Game Gear before us, but that went wrong. The device consumed so much energy that kids in the car on the way to France already faced dead batteries in Antwerp” (Escher, 1998). Though bad-mouthing each other’s products was common among Nintendo and Sega executives in the 1990s, the Nintendo representative was right in the sense that the Game Boy, like the Walkman, was popular among Dutch parents for the very reason he offered. Without these portable devices to keep their offspring busy, many articles noted, car rides to popular holiday destinations such as France were “hell” (Botman, 2000). The lion’s share of articles perceived Nintendo’s dominance on the handheld market as a given.

As with the Walkman, newspapers reported that the success of handhelds did not merely show in sales, but also made its mark on society and culture at large. Both Nintendo and Sega established customer service telephone lines to help players out, most notably those who were stuck on a particular level (cf. Sheff, 1993, pp. 181-186). Though questions could concern any console, the number of calls soared after handhelds were introduced. So did the number of members of Club Nintendo Netherlands. The club could be joined for free after purchasing a Nintendo product. From about 50,000 in 1991, membership ballooned to 470,000 in 1994. Popular culture picked up handhelds, too. Television series and films such as Police Academy featured the device. Candidates of the first season of the Dutch version of the television show Survivor (Expeditie Robinson) were allowed to bring one indispensable item; one of them brought a Game Boy (Gerritse, 2000). Whereas Walkmans affected haircuts, handhelds impacted fashion: shirts and pants were equipped with extra pockets to store them (“Lekker stoer,” 1998). Additionally, a new Dutch airline rented out Game Boys during flights to cater to young families - a service which, according to its manager, “was very well received” (“‘Eelde’ blij,” 2001). Hotels in England and the United States even substituted the bible on nightstands with a Game Boy. The Anglican church felt obliged to respond: “The bible has survived television, has conquered video and will survive this as well. Because God’s word is for everyone, Nintendo isn’t” (Helmink, 1993).

Handhelds likely would have been even more popular, had retail prices not put a brake on purchases. Whereas the portable cassette player market was flooded with cheap devices and cassette tapes, handheld hardware and software were expensive. In 1990, Atari’s Lynx retailed for 569 guilders. This was incrementally dropped to 349 guilders in 1991, the same price Sega charged for its Game Gear. The Game Boy was considerably cheaper. It cost 199 guilders (reduced to 99 in 1993) and cartridges originally started at 69 guilders. Still, this was too expensive for its prime audience, children aged 6 to 14, who had to have their parents buy the device for them.

Over a dozen articles lamented high prices. Spending this much on a present for your children, a journalist wrote, “isn’t peanuts for the generation which used to be satisfied with a Dinky Toy” (Rozendaal, 1992). Still, a great many parents fulfilled their offspring’s wish -- in part, some suggested, to keep up with Joneses (see the next subsection). Alternatively, Game Boys and cartridges could be rented from video stores. Other consumers resorted to cheaper illegal cartridges. Nintendo estimated that illegal copies comprised ten to twenty percent of total Game Boy cartridges sales and “in the Netherlands alone, Nintendo spends about a million per year on lawyers and detective agencies to fight this” (Van de Vijver, 1993; cf. Sheff, 1993, pp. 284-287). A cheaper handheld was available (Supervision), yet never became popular and was barely discussed. The Neo Geo Pocket was similarly barely mentioned.

Users and the Discursive Construction of Users

Game histories assert that the Game Boy brought gaming to adults. Sheff (1993, p. 295) writes that in the United States “Game Boys were frequently seen in first-class compartments on cross-country flights, in corporate lunchrooms, and in desk drawers and briefcases.” Two out of five (Wesley & Barczak, 2010, p. 82) or close to half of the Game Boy players “in the West” (Sheff, 1993, p. 339) were over 18 years old. Not in the Netherlands, however. This section shows that, even though adults used the device, too, handhelds were predominantly used by children. This section also highlights how the press chiefly represented handhelds as toys for kids.

Only about two dozen articles explicitly mentioned that adults used handhelds. A 1994 article held that next to the largest group of Game Boy players, children between 6 and 14 years old (43 percent), a significant group (28 percent) was between 25 and 45 years old (Schöndorff, 1994). Other articles stressed that celebrities such as professional athletes, movie stars and artists -- particularly those who were young and traveled a lot -- took a liking to the Game Boy. For example, 20-year-old singer Dannii Minogue was quoted: “Many of my friends have Game Boys and, wherever on the planet, we call each other to see who has the high score” (“De nationale,” 1992). Tennis professional Wayne Ferreira (then 24) claimed that the device had significantly improved his dexterity and responsiveness -- after which he was dubbed “Game Boy Ferreira” (Salomon, 1995). Additionally, Nintendo repeatedly stressed that its info lines were consulted by adults as well. It stressed that executives had their secretaries make inquiries when they struggled with their Game Boy: “If you explain something to them, all of a sudden the executive jumps in with many questions” (Kuijt, 1992). The military comprised another adult user group. If the Gulf War was, as General Schwarzkopf put it, the first “Nintendo war” (Rozendaal, 1992; cf. Sheff 1993, p. 284), it was then followed by a “Game Boy war”. A Dutch officer of the United Nations’ Peacekeeping mission in former Yugoslavia maintained that for most soldiers, “it is long live the Game Boy…. When the war will be over, a Dutch veteran will win the world championships on that console” (Thomassen, 1992).

The press noted, however, that most Game Boy users were children. Next to “the Nintendo Generation” (cf. Arsenault, 2017; Kline et al., 2003; Sheff, 1993), youth were occasionally referred to as “the Game Boy generation.” Especially in the early 1990s, children craved a Game Boy. The device and cartridges featured prominently on many children’s wish lists. An article in a newspaper for Dutch Jews illustrated how precious the Game Boy was. It had children discuss Anne Frank’s life story. When asked what they would bring if they were forced into hiding, one child said: “In any case my diary and Game Boy” (Pels, 1992). To be cool and fit in, other articles added, children had to have a Game Boy; it became a status symbol. This is epitomized by an article about fashion-forward kids that featured a picture of a boy, who demanded: “I must have Nike’s, Levi’s, a mountain bike and a Nintendo Game Boy!” [sic] (Hering, 1991).

The fact that such articles, which explicitly linked the Game Boy to consumerism, were few and far between, underlines how normal it had become for parents -- and most journalists were parents -- to give into children’s desires and buy them such expensive equipment. What’s more, journalists did not criticize this trend, which they had done regarding the Walkman from 1980 onwards. This suggests that consumerism had gotten hold of Dutch people (see discussion).

The press not only covered the popularity of Game Boys among children. In concert with Nintendo, retailers and experts, journalists also coded the device as a toy for children. Video games in general, and handhelds in particular, were referred to as “toys” hundreds of times. Nintendo’s Dutch director in 1991 proclaimed: “The Game Boy is a logical product, which, next to the Walkman, is part of the standard gear of school-going youth” (Goddijn, 1991). The association was also established by an accolade. In 1991 the leading trade organization Good Toys (Goed Speelgoed) crowned the Game Boy Toy of the Year in the category school-age children (e.g., Goddijn, 1991). Additionally, some specialized electronic stores refused to sell Game Boys and other consoles, as they feared that “hordes of children” would scare off their core clientele (“Super Mario,” 1994). Dictionaries, too, framed the Game Boy as a product for kids. Newspapers noted that leading dictionary publisher Van Dale included the word “gameboy” [sic] in the first, 1994 edition of its junior dictionary, which was aimed at kids over eight years old. (Incidentally, the fact that “gameboy” was included and “gamen” [gaming] was not, underscores the need to look into consoles). The 1999 edition of Van Dale's dictionary for adults, on the other hand, included neither “gameboy” nor “gaming,” much like the previous, 1992 edition.

Evaluation

As discussed in the literature review, most research in the field of game studies highlights how video games and gaming have predominantly been cast in extreme light and have mainly been problematized: dystopian ideas permeate media imaginaries. My analysis arrives at the opposite conclusion: in media items on the Game Boy, video gaming was met with a moderate, unperturbed response. Admittedly, this section will argue, a small portion of news items mentioned potential dangers of the Game Boy or gaming in general (as consequences of gaming were not always related to a specific console), particularly between 1990 and 1994. Yet most of these news items did so in a perfunctory way, presented potential dangers ironically, disproved of them, or mitigated them. This also stands in sharp contrast to the Dutch response to the Walkman, which -- as mentioned before -- was castigated as a manifestation of reprehensible individualism because it isolated users and was believed to spur escapism and inconsiderateness.

Media items that mentioned potential positive effects of gaming were very rare. On the other hand, about one out of five newspaper articles in the period 1990-1994 mentioned possible downsides or dangers of gaming. These 36 articles plus one newscast touched upon a variety of topics, some of which were consistent with those raised in the United States. Many pointed at the addictiveness of gaming (cf. Williams, 2003, p. 542), a qualification which was also ascribed to the Walkman. On a couple of occasions, players were referred to as “Nintendo junkies.” Among the other recurring topics were the alleged association of gaming with health issues, such as obesity and joint inflammation, and the presumption that gaming replaced activities that were deemed more worthwhile or vital, such as reading or learning to play an instrument (cf. Williams, 2003, p. 540).

These items can be divided into three subgroups based on how negative they were. The smallest group, containing six articles, cast video gaming in an outright negative light. One article had parents warn others: “The day I will throw out the Game Boy is nearing,” one complained, “it drives me crazy” (Van Weerdenburg, 1991). It isolated children who were intoxicated by their handheld, and monopolized children’s attention at the expense of other activities. Other articles discussed potential health problems.

The second group, comprising ten articles and one television newscast, mentioned (potential) negative consequences in passing, without extensively problematizing them. A couple of sources implied that gaming impeded communication. The majority referred to the addictive nature of gaming, without dwelling on it. One article led with: “‘It is child’s cocaine!’ quips American comedian Robin Williams about the Nintendo game computer… Kidding” (Van Weerdenburg, 1992). The remainder of the article sidestepped this topic completely. Another long article, which was very favorable to Nintendo, had a 16-year-old boy sing the praises of gaming. In a mere couple of sentences, the article dryly reported that gaming was additive, too, and had led Hessel to neglect his homework: “The school holding him back a year… was his reward” (De Jong, 1993).

Twenty articles in the third and largest group, too, mentioned or discussed potential or supposed detrimental effects of video gaming. However, they either rebutted or nuanced these consequences, or offset them by highlighting positive effects. The latter happened when the Game Boy was crowned Toy of the Year in 1991, the first time an electronic video game won this prize. Newspaper articles indicated that society had overcome long-standing objections vis-à-vis electronic games. One read: “The jury for the first time jettisoned old norms which held that video games are bad for children and merely constitute fads” (Van Ooyik, 1991). Since handhelds could be connected to each other via a cord, experts now submitted they fostered social interaction. Though one jury member, a remedial educationalist, urged parents to guard against addiction, she also offered additional advantages of portable consoles: they could be played on the road and, “most importantly, have children at a young age come in contact with the indispensable phenomenon that is the computer” (Roosendaal, 1991).

Such acclaim from professionals likely worked as a stamp of approval that prevented or mitigated criticism in the ensuing years. Referring to the Toy of the Year accolade, one journalist for example wrote how he had changed his opinion. After criticizing the Game Boy for causing children to be “completely out of it,” he became intrigued by “intelligence game Tetris,” and it appears the aforementioned jury report helped him come around completely (Hovius, 1991).

In short, most journalists seem to have had a hard time buying into the alleged dire consequences of gaming and were quick to discard them. This is best illustrated by a cover article of news weekly Elsevier (Rozendaal, 1992), with the headline: “Super Mario… The addictive video game. What is to become of our children?” This last line reflects the ironic tone of the long read. Although the “musings of a worried father” did extensively discuss a plethora of potential perils, it was a tongue-in-cheek article that will have left few parents anxious. For instance, it hyperbolically stated that “the Netherlands is annexed by the Mushroom Kingdom:” “It was already known that Japan manufactures our means of transportation and sound equipment [a.o. hinting at Walkmans], yet now the country of the Rising Sun rules between our kids’ ears. The hand that rocks the cradle, governs [sic] the world.” Yet right after presenting such arguments, the article downplayed them. In this case: Nintendo was an international company, most video games were produced in the United States, and Bandai, the company in charge of Nintendo’s Dutch business in the early 1990s, was at liberty to not import certain games.

The press reckoned that the problems supposedly caused by gaming were not only smaller than what some naysayers made them out to be, but also nothing new. Yes, the Elsevier article and a couple others conceded, video games immersed children in a one-sided universe where females are powerless and a clear divide exists between right and wrong, which had little to do with the real world (cf. Williams, 2003, p. 542). But, the Elsevier journalist continued lightheartedly, “that concern, too, can be relativized. Was the world view of Jip and Janneke [iconic Dutch child literature characters] that much better?”

Journalists could reasonably take this “not to worry”-stance because little to no research pointed to games being a hazard. “It takes some getting used to the new child culture, yet according to professional pedagogues video games do not really harm,” one typical article read (Jansen, 1992). Experts actively resisted “pending doom”-stories. In response to British tabloids that claimed that Nintendo kills, two newspapers had doctors disprove that games cause epileptic seizures. In reference to discussions about a rating system in the United States in response to violent games, another newspaper interviewed a Dutch professor of mass communication. He deemed the possibility that players wanted to emulate video game violence slim and concluded: “Let’s not be culturally pessimistic, as if all evil stems from new media” (Van Dam, 1993). Most academics who had their say in the press concurred. Based on a literature review, a professor of social psychology in 1993 emphatically debunked the idea that video games “threaten the mental and physical health of children.” He believed that such anxieties “emanate from a fear of technology” on the part of older people (Bloemkolk, 1993). He stressed instead that games could be conducive, as they trained one’s memory, furthered techno-literacy and promoted playing together (cf. McKernan, 2013, p. 321; Williams, 2003, pp. 537-539).

Nintendo used this research to its advantage. In anticipation of critical journalists, it summarized these outcomes in a folder designed for the press. This was dispersed during the 1993 Dutch Nintendo championships, which also included a Game Boy competition. One of the event’s goals was to fight existing prejudices about gaming. It appears this strategy paid dividends. One journalist for example criticized gaming’s negative status aparte: “No one questions the national championships of Monopoly (a guerilla training in capitalism in disguise) or Risk (an extensive exercise in imperialism and militarism). Yet when it comes to video games, educators raise the question whether it is pedagogically and socially sound” (Jansen, 1993).

In conclusion, between 1990 and 1994, most journalists who discussed the potential detrimental effects of video games were unexcited and unconcerned. A far greater number were probably indifferent to these consequences altogether, as they did not address them. In light of the press’ tendency to cover and reinforce moral panic, this can be read as a sign that they did not buy into dystopian visions, either.

As the 1990s evolved, this remained the dominant outlook among journalists. In the period 1995 through 2000, the number of news items that discussed potential harmful effects of gaming dropped to under five percent (17 out of 347); most of these items lamented that gaming substituted other activities. None of them, however, extensively cast gaming in an outright negative light, save for a radio documentary. Aired two months after “Columbine,” Help, he wants a Game Boy (Batenburg, 1999) asserted that video games spelled trouble. One interviewee, a professor of psychology, claimed that it would only be a matter of time before violent games result in “American scenes,” meaning public violence. Tellingly, even this exception is indicative of the process of normalization and naturalization of the Game Boy that I sketched in this article. Despite discussing detrimental consequences, the producer of the documentary still bought his 7-year-old son a Game Boy. In short, in the 1990s it was accepted that handhelds and video gaming were a part of life which barely warranted discussion.

Conclusion and Discussion

This article has highlighted how handheld game consoles, the Game Boy in particular, were extremely popular in the Netherlands in the 1990s, predominantly with children. The Dutch response to handhelds and video gaming was a far cry from responses abroad. Whereas utopian and, primarily, dystopian views dominated the cultural debate over gaming in the US, Dutch handheld discourse was remarkably moderate. In the first half of the 1990s, potential dangers of video gaming were routinely raised, yet this mostly happened in a cursory, unperturbed manner. Backed by an absence of scientific literature substantiating dire views, the vast majority of journalists and experts shrugged their shoulders and covered video gaming as a non-problematic practice. This would remain the prevailing stance throughout the 1990s.

These findings underline that future research would be well-advised to, first, examine popular reactions to video gaming in understudied areas, so as to paint a more complete picture of the historical thoughts and feelings surrounding this phenomenon and thereby counter the implication that these reactions “were the same everywhere” (Swalwell, 2021b, p. 1). Second, research should be open to the possibility that different consoles elicited different reactions. The Game Boy for example carried fewer violent and more puzzle games, its “bread and butter” (Ryan, 2012, p. 104), than other consoles, which likely factored into a more favorable response. Third, this article has made the case that future research should contrast cultural debates on gaming and consoles with public discourse about other contemporary media. This approach in my case underlines that there was nothing in the Dutch water that had contemporaries respond to handhelds the way they did. The Netherlands, too, has a history of moral panic prompted by the introduction of new media, which in the 1990s was evinced by Walkman discourse. Handhelds, then, were an exception to a historical rule.

Alas, discourse analyses cannot wholly and definitively account for such divergent portrayals, which is a first shortcoming of this article. There are provisional explanations, however.

One of the reasons Walkman users were consistently rebuked, is that they introduced what was considered deviant behavior in public. They isolated themselves and apparently did not care whether this, or the sound of their device, bothered others. Custodio argues that the Game Boy caused a similar transgression of the private-public boundary, “slotting into empty moments and public spaces” (Custodio, 2020, p. 122; cf. Sheff, 1993, p. 295). This does not seem to have happened in the Netherlands, though. Only a couple of articles described how handhelds were used in public, for example on public transit. User patterns factored into this. Whereas the Walkman in the Netherlands and handhelds abroad had a considerable percentage of adolescent and adult users, handhelds in the Netherlands were mainly popular with young children from about six to fourteen, who do not travel as much. At the same time, no news items point to handhelds having been used during classes. In France, such usage led to a ban (Sheff, 1993, p. 414), much like the prohibition of the Walkman in some Dutch schools. Based on public discourse and secondary research (Beentjes et al., 1999; cf. Custodio, 2020, p. 136), handhelds seem to have mainly been used in the domestic sphere and on family car rides. The resultant relative public invisibility helps explain why the Dutch responses to Walkmans and handhelds were as different as night and day.

It can be theorized that cultural trends played into the moderate assessment of handhelds as well. Though the cultural history of the Netherlands in the 1990s is understudied, existing accounts stress that the decade saw “great, decadent prosperity” (Jürgens, 2014, p. 112). As the country turned into one big middle class, a hedonistic-consumeristic lifestyle became the standard. Reflecting on this decade, a historian in 1998 remarked: “Hedonism is the new conformism. Who doesn’t enjoy life is [deemed] a fool” (Schoonhoven, 1999, p. 254).The success of handhelds, it can be argued, emblematized and helped naturalize this lifestyle. Going by the non-judgmental response handhelds prompted, consumerism was no longer deemed problematic -- as it had been up to at least the 1980s.

Tying in with this, grown-ups in the 1990s increasingly satisfied their soaring consumptive desires outdoors, whereas children “more than ever before spent time at home, in their room” (“cocooning”), enjoying their electronics (Schoonhoven, 1999, p. 39). Paired with the fact that Dutch parents had never worked such long hours, it is likely that parents bought their offspring a Game Boy out of guilt (cf. Schoonhoven, 1999, p. 146). This, in turn, will have made it harder for parents, journalists included, to criticize (potential) consequences of this decision. It might also have precluded the reproach that handhelds symbolized consumerist entitlement, which was leveled at Walkman users.

A final relevant factor is that most Dutch experts, such as doctors, pedagogues and scholars, rejected the idea of gaming as a hazard. This position likely affected Dutch journalists in the opposite way it affected journalists overseas. In the US, both journalists and scholars were invested in identifying potential negative effects of gaming, which likely caused their agendas to align and reinforce one another (Williams, 2003, p. 544; cf. Shaw, 2010).

Resuming the discussion of shortcomings, two additional limitations stand out. The article’s focus on popular discourses about one specific console, or console type, is deliberately bounded. Even though these discourses always also touch upon video gaming in general, it should be acknowledged that they do not offer an exhaustive overview of the public image of video gaming. It might for example be the case that video gaming in the Netherlands during the 1990s was perceived (somewhat) negatively, too, yet this criticism was projected onto other consoles. This could be tested by scrutinizing public debates about other devices and video gaming in general.

Finally, the article solely discusses media representations. Additionally, a “wider suite of authentic voices” (Wade & Webber, 2016, p. 5) could be interrogated, for example those who at the time were involved with video games, such as parents, players, and game industry representatives. Future research could also look into marketing discourse (cf. Kline et al., 2003; Verhoef, 2015 ) of the Game Boy and other consoles. Both options would help paint a more complete picture of the social construction of particular consoles and do the console-specificity justice.

Endnotes

[1] Owing to optical Character Recognition and Optical Layout Recognition flaws, the exact number for 1990-1994 cannot be established. The same goes for the audiovisual archive.

[2] https://mediasuitedata.clariah.nl/dataset/audiovisual-collection-daan (accessed May 4 2022).

[3] The overall number of people who at some point between 1990 and 2000 fell in this group was much higher.

References

Arsenault, D. (2017). Super Power, Spoony Bards, and Silverware: The Super Nintendo Entertainment System. MIT Press.

Batenburg, J. (1999, June 25). Help, hij wil een gameboy! [Radio broadcast] Radio 5.

Beentjes, H., d’Haenens, L., Voort, T. H. A. van der, & Koolstra, C. M. (1999). Dutch and Flemish Children and Adolescents as Users of Interactive Media. Communications, 24(2), 145-166.

Bigl, B., & Schlegelmilch, C. (2021). Are Video Games Still a Boys’ Club? How German Public Television Covers Video Games. Games and Culture, 16(7), 798-819.

Bloemkolk, J. (1993, April 11). Bange ouders, wees gerust. Parool.

Botman, A. (2000, July 1). Pedagogie voor de achterbank. Trouw.

Cao, S. & He, W. (2021). From electronic heroin to created in China: Game reports and gaming discourse in China 1981-2017. International Communication of Chinese Culture, 8(4), 443-464.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. SAGE.

Custodio, A. (2020). Who are you? Nintendo’s Game Boy Advance Platform. MIT Press.

Dam van, N. (1993, December 4). Discussie over videospelletjes. Trouw.

De Nationale Top-100. (1992, January 29). Telegraaf.

Egenfeldt-Nielsen, S., Smith, J. H., & Tosca, S. P. (2016). Understanding Video Games: The Essential Introduction (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Escher, E. (1998, April 1). In een kinderkamer is altijd plaats. Parool.

G&G. (1999, December 21). Leeuwarder Courant.

Gerritse, T. (2000, September 6). Expeditie Robinson met Game Boy. Algemeen Dagblad.

Gill, R. (2000). Discourse Analysis. In M. Bauer & G. Gaskell (Eds.), Qualitative Researching with Text, Image and Sound (pp. 173-190). SAGE.

Goddijn, H. (1991, November 30). De opkomst van Super Mario. Algemeen Dagblad.

Gorges, F. (2019). L’histoire de Nintendo. Volume 4, 1989-1999, l’incroyable histoire de la Game Boy. Omaké Books.

Gruijthuisen van, E. (1993, March 18). Philips ziet grote geld in cd-i-plaatjes. Parool.

Herman, L. (2008). Handheld video game systems. In M. J. P. Wolf (Ed.), The Video Game Explosion: A History from PONG to Playstation and Beyond (pp. 143-148). Greenwood Press.

Helmink, F. (1993, September 7). Kerk is niet bang. Volkskrant.

Hering, F. (1991, August 21). "Zonder Levi's geen leven!" Telegraaf.

Hovius, P. (1991, October 30). In de ban van Game Boy. Algemeen Dagblad.

Jansen, W. (1992, December 19). Nieuwe kindercultuur kwestie van wennen. Trouw.

Jansen, W. (1993, September 18). Oorlog in het Land van Ooit. Trouw.

Jong de, M. (1993, February 6). Nintendo-gekte maakt van jeugd 'dealers'. Leeuwarder Courant.

Jürgens, H. (2014). Na de val. Nederland na 1989. Vantilt.

Kent, S. L. (2001). The ultimate history of video games: From Pong to Pokémon and beyond. Crown.

Kirkpatrick, G. (2012). Constitutive Tensions of Gaming’s Field: UK gaming magazines and the formation of gaming culture 1981-1995. Game Studies, 12(1). https://gamestudies.org/1201/articles/kirkpatrick

Kline, S., Dyer-Witheford, N. & De Peuter, G. (2003). Digital play: The interaction of technology, culture, and marketing. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Kuijt, P. (1992, 25 November). Hulplijnen voor Nintendo-spelers. Limburgsch Dagblad.

Lekker stoer. (1998, October 17). Dordtenaar.

Maclean, E. (2016). Girls, Guys and Games: How News Media Perpetuate Stereotypes of Male and Female Gamers. Press Start, 3(1), 17-45.

McKernan, B. (2013). The morality of play: Video game coverage in The New York Times from 1980 to 2010. Games and Culture, 8(5), 307-329.

Narine, N. & Grimes, S. M. (2009). The Turbulent Rise of the “Child Gamer”: Public Fears and Corporate Promises in Cinematic and Promotional Depictions of Children’s Digital Play. Communication, Culture & Critique, 2(3), 319-338.

Nicoll, B. (2017). Bridging the gap: The Neo Geo, the media imaginary, and the domestication of arcade games. Games and Culture, 12(2), 200-221.

Nikken, P., Leede, N. de, & Rijkse, C. (1999). Game-boys en game-girls: Opvattingen van jongens en meisjes over computerspelletjes. SJN.

Ooyik van, D. (1991, September 14). Computerspelletje mag, slopen ook. Dagblad van het Noorden.

Parrott, S., Rogers, R., Towery, N. A. & Hakim, S. D. (2020). Gaming Disorder: News Media Framing of Video Game Addiction as a Mental Illness. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 64(5), 815-835.

Paul, C. A. (2012). Wordplay and the Discourse of Video Games: Analyzing Words, Design, and Play. Taylor & Francis.

Pels, B. (1992, May 1). Drie jongeren spreken met elkaar over Anne Frank. Nieuw Israelitisch Weekblad.

Reynolds, D. (2016). The Vitruvian Thumb: Embodied Branding and Lateral Thinking with the Nintendo Game Boy. Game Studies, 16(1). https://gamestudies.org/1601/articles/reynolds

Roosendaal, M. (1991, September 9). Orthopedagoge gaat toch overstag voor elektronisch spelletje. Telegraaf.

Rozendaal, S. (1992, November 21). Mario verovert de wereld. Elsevier (47).

Ryan, J. (2012). Super Mario: How Nintendo Conquered America. Portfolio.

Salomon, R. (1995, November 15). Game-Boy Ferreira wil nog twee keer verliezen. Algemeen Dagblad.

Schoonhoven, G. van (Ed.). (1999). De nieuwe kaaskop. Nederland en de Nederlanders in de jaren negentig. Prometheus/Elsevier.

Shaw, A. (2010). What is video game culture? Cultural studies and game studies. Games and Culture, 5(4), 403-424.

Sheff, D. (1993). Game Over: How Nintendo Zapped an American Industry, Captured Your Dollars, and Enslaved Your Children. Random House.

Sturken, M., Thomas, D. & Ball-Rokeach, S. (Eds.). (2004). Technological Visions: Hopes and Fears That Shape New Technologies. Temple University Press.

Super Mario en Sonic niet welkom bij speciaalzaak. (1994, May 30). Volkskrant.

Sutherland, A. (2012). Nintendo. The story behind the iconic business. Wayland.

Swalwell, M. (2021a). Heterodoxy in Game History: Towards more ‘Connected Histories’. In M. Swalwell (Ed.), Game History and the Local (pp. 221-233). Palgrave Macmillan.

Swalwell, M. (2021b). Introduction: Game History and the Local. In M. Swalwell (Ed.), Game History and the Local (pp. 1-15). Palgrave Macmillan.

Thomassen, M. (1992, November 14). Comfortabel tussen vele vuren. Algemeen Dagblad.

Veraart, F. (2011). Losing Meanings: Computer Games in Dutch Domestic Use, 1975-2000. IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, 33(1), 52-65.

Verhoef, J. (2015). The Cultural-historical Value of and Problems with Digitized Advertisements. Historical Newspapers and the Portable Radio, 1950-1969. Tijdschrift voor Tijdschriftstudies, 38, 51-60. https://doi.org/10.18352/ts.344

Verhoef, J. (2016). Lawaai als modern onheil. De draagbare radio en beheerste modernisering, 1955-1969. Tijdschrift voor Geschiedenis, 129(2), 219-240. https://doi.org/10.5117/TVGESCH2016.2.VERH

Verhoef, J. (2017). Opzien tegen modernisering. Denkbeelden over Amerika en Nederlandse identiteit in het publieke debat over media, 1919-1989. Eburon.

Verhoef, J. (2022). The Epitome of Reprehensible Individualism: The Dutch Response to the Walkman, 1980-1995. Convergence, 28(5), 1303-1319. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565211060297

Wade, A. & Webber, N. (2016). A future for game histories? Cogent Arts & Humanities, 3(1), 1212635.

Wartella, E. & Reeves, B. (1983). Recurring Issues in Research on Children and Media. Educational Technology, 23, 5-9.

Weerdenburg van, P. (1991, August 24). Verslaving aan Nintendo-computerspelletjes neemt vreemde vormen aan. Telegraaf.

Weerdenburg van, P. (1992, December 19). Loodgieter contra stekelvarken. Telegraaf.

Wesley, D. & Barczak, G. (2010). Innovation and Marketing in the Video Game Industry: Avoiding the Performance Trap. Gower.

Williams, D. (2003). The video game lightning rod: Constructions of a New Media Technology, 1970-2000. Information Communication & Society, 6(4), 523-550.

Wirman, H. (2016). Sinological-orientalism in Western News Media: Caricatures of Games Culture and Business. Games and Culture, 11(3), 298-315.

Zeiler, X. & Thomas, S. (2021). The relevance of researching video games and cultural heritage. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 27(3), 265-267.