“The Mythical Mass Market”: Design, Habit and the Invention of the American Mobile Gamer

by Logan BrownAbstract

Mobile gaming is quite literally everywhere. People all over the world play mobile games while waiting for buses, sitting in traffic and lounging at home. Since the 2000s, scholars have worked tirelessly to diagnose what mobile gaming’s increasing ubiquity will mean for the game industry and for the future of 21st century culture. Yet few of those scholars to date have turned their attention backward to understand how this new medium gained such profound cultural purchase in the first place. This article rectifies the historical amnesia around mobile games by telling the story of how the early, pre-iPhone American mobile game industry invented what I term the “mobile habitué,” a new kind of mobile gamer. Drawing from historical interviews, contemporary market reports and trade magazines like GDC and Game Developer Magazine, I argue that the new figure of the mobile habitué is defined not by the genre loyalties that associated with terms like “hardcore” and “casual,” but rather by their highly habitual, richly affective relationship with the cell phone as a device for personal and social management. The industry’s understanding of the mobile user as habitué led the industry to innovate new design strategies aimed at habituating cell phone use through repetition, social pressure, accumulation and variable reward, strategies which continue to haunt and habituate users in the hyper-mobilized present.

Keywords: game history, mobile gaming, player subjectivity, habit, affect, identity, addiction

Introduction

“Habits are strange, contradictory things: they are human-made nature, or, more broadly, culture become (second) nature. They are practices acquired through time that are seemingly forgotten as they move from the voluntary to the involuntary, the conscious to the automatic. As they do so, they penetrate and define a person, a body, and a grouping of bodies.” - Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Updating to Remain the Same

Americans today are thoroughly invested in mobile gaming. Indeed, if the USA circa 2024 has a mobile games problem, it’s that Americans might like mobile games too much. In a recent New York Times op-ed, mobile developer William Siu (2022) confessed that he will not let his children play his own games, for fear that the games’ addictive designs could have deleterious effects on his children’s social aptitudes, attention spans and self-control. The World Health Organization’s formal 2019 recognition of “gaming disorder” (i.e. addiction) supercharged concerns about mobile games and pushed conversations about mobile game regulation into the mainstream; that same year, Republican senator Josh Hawley introduced the Protecting Children from Abusive Games Act, a piece of bipartisan legislation aimed at stopping “Social media and video games [that] prey on user addiction, siphoning our kids' attention from the real world and extracting profits from fostering compulsive habits” (Sinclair, 2019). Naturally, Hawley chose as his poster child for addictive malfeasance was not a console title, but the ever-popular mobile game Candy Crush, which he called a “‘notorious’ example of an exploitative game.” Nor are these concerns particular to attention-seeking politicians and histrionic helicopter parents; veteran games journalist Stephanie Sterling has spent years inveighing against the predatory, addictive monetization practices that keep players glued to their iPhones for hours or days at a time.

Concerns about mobile gaming addiction have led to a degree of ghettoization for mobile games, which do not often appear in august cultural venues like Geoff Keighley’s Game Awards or the Strong Museum of Play’s much-discussed Hall of Fame [1]. Often, journalists and games influencers justify mobile’s dismissal by pointing either to mobile’s aesthetic conservativism, its aesthetic simplicity, or both. Mobile games, “core” players often assert, are today almost synonymous with free-to-play monetization and hypercasual design, which favor exploitative pricing models and simplistic gameplay over challenging, skill-based design or complex, sprawling narratives (Davis, 2013). In the most extreme cases, critics of mobile games will even dismiss mobile games as being so simple and “casual” that they cease to be “real” games at all (Consalvo & Paul, 2019). For these detractors, mobile gaming’s popularity is damning, its success a product of its bland addictiveness.

More recently, however, scholars have grown suspicious of the backlash against mobile and free-to-play games, which they claim has more to do with the toxicity of gaming culture than with mobile games themselves. Christopher Paul (2020) has persuasively demonstrated that much of mainstream gaming culture’s continued dismissal of mobile games is really just “a bit of snobbery and gate-keeping” from the gaming’s “old guard,” as mobile games “are often played by children, the middle-ages, women and people in distant countries like Russia and Korea” (p. xxv). For Paul, mobile’s second-class status stems directly from gaming’s relationship with a particular demographic (the young straight white male “gamer”) and with a set of values that that demographic has helped to naturalize both within the industry and within gaming culture more broadly (Paul, 2018). These values are familiar, if only implicitly, to anybody who has spent time around games and gaming: skill, commitment, persistence, competitiveness and complexity are all highly valued. Casual gaming and casual players, by contrast, are typically understood as privileging simple gameplay loops, accessible themes, mild punishments for failure and flexible play patterns which make for more approachable experiences (Juul, 2010).

This supposedly simply hardcore/casual binary breaks down almost immediately in practice, however. Firstly, casual players have never played casually; they often play as much as or more than their console-playing peers and often with comparable strategic savvy (see Juul, 2013, p. 8). Secondly, self-proclaimed “hardcore gamers” often do play the kinds of mobile games they would normally deride -- they just don’t necessarily admit to it. Paul (2020) points out that the same games journalists who deride the free-to-play model will often write articles on the F2P games they’ve been playing; they just have to “explain, justify, or rationalize” that play through a “confessional” mode (p. 43). He also notes that gamers have no trouble with casual and “pay-to-win” games that are marketed toward the hardcore market, popular mobile games like Magic the Gathering Arena and Hearthstone that reward player spending with more and better cards, putting high-spending players at a distinct advantage

The breakdown of the hardcore/casual binary leaves mobile gaming scholarship with a number of pressing, unanswered questions. If everybody plays mobile games, what is a mobile player? How is “mobile” different from other forms of gaming? And in a media environment as saturated with smartphone use and abuse as the United States in the 21st century, what broader social consequences might result from the almost total normalization of new kinds of mobilized digital play?

This paper seeks to answer these questions by arguing that the “mobile player” represents an entirely new kind of technological and ludic subjectivity that I call the mobile habitué. Where hardcore and casual players are traditionally defined by gameplay values and genre preferences and play values, the habitué is instead defined by a set of embodied habitual bonds that the mobile habitué forms with their cell phone. Unlike portable consoles like the Game Boy, the cell phone boasted two important features: always-on network access and mobility. As people across the world began adopting and domesticating their cell phones, they quickly found that access combined with mobility made games time- and space-independent, meaning they could be available at anytime, anywhere. The early industry, as we will see shortly, recognized that if users could be trained to incorporate this new entertainment form into their day-to-day routines, the inertia of habit and the temptation of endless entertainment would keep them coming back indefinitely.

This article describes and analyzes the habitué historically, following its historical formation from 1999’s release of NTT DoCoMo’s i-mode platform to 2008’s rollout of the Apple App Store. The historical perspective offers two advantages. First, the habitué is easiest to discern in an era before habituation to mobile media was so total as to be functionally invisible. Almost everybody who owns a smartphone today is habituated to it; one need only look to the present discourse around phone use and addiction to see how thoroughly the mobile phone has woven itself into the fabric of our everyday lives. Yet this was not always the case. Through the early 2000s, Americans actually lagged behind Asian and European users in the social and playful uses of cell phones; they had to be instructed through marketing and design to treat the phone as the object of their habitual attention. The historical perspective reveals how contingent -- and yet how deliberate -- the social process of mobile habituation really was.

Second, I hope to carve out a space for more histories of mobile games within the rapidly growing field of game history. Game history has made great strides since its early “chronicle” days, when uncritical fan histories dominated the space (Guins, 2017; Huhtamo, 2005; Suominen, 2017). The formation of an academic game history has since expanded the field’s concerns and historiographies to include game histories of industrial design (Guins, 2020), gender (Kocurek, 2015; Nooney, 2013), regional fan practices (Švelch, 2018; Swalwell, 2021) and many more besides (see Suominen, 2017). But to date mobile history has been overlooked by game historians in the west. Beyond simply “gap-filling” by providing a historical account of mobile gaming, this essay hopes to demonstrate that mobile game history has wider implications for 21st century cultural and social change around mobile digital devices.

Finally, this article also intervenes in discussions of habituation and addiction in mobile gaming by correcting the dominant, Apple-centric narrative of mobile media history. When game and media scholars diagnose mobile media’s addictive qualities, they tend to do so by looking at the present. These critiques have (rightfully) pointed to everything from the iPhone’s touchable form factor (Cooley, 2014) to modern mobile apps’ push notifications and UX designs (Vaidhyanathan, 2018) to a modern epidemic of loneliness and isolation (Ekbia & Nardi, 2017). All of these claims are, in some way or another, attached to Apple as either the implicit or explicit author of our mobile present and to the iPhone as the “revolutionary innovation” that made all of these sociotechnical changes possible. If mobile media is everywhere today, the standard mobile narrative goes, it is because the iPhone proved so simple that even luddites eventually found themselves compelled to adopt it. There is some truth to this, but it is a partial truth. As I will show, the habit and addiction-focused design choices that fueled the iPhone’s rise were originally developed by the early mobile industry as short-term survival strategies for a rapidly changing media landscape. Faced with an apathetic American consumer base and punishingly underpowered handsets, the early industry bet its very future on its ability to keep Americans hooked to small but irresistible mobile experiences.

As a final note, this article exclusively addresses the early American context, by which I mean businesses and users located in the United States. Focusing on a single national context does necessarily simplify what was from the beginning a fully global business; a game at this time might be developed by a Korean developer for a US publisher and then distributed by a French telecom in Belgium. However, at the present state of mobile game history, the international angle would necessitate overlooking the meso-level design decisions that were so central to the formalization of habit-forming games.

From Department Store to Konbini -- i-mode and Defining the Mobile Habitué

If the mobile games market and its attendant subjectivity, the mobile habitué, has a single origin, it is the launch of the i-mode mobile internet platform in 1999. Rolled out in February of that year, i-mode was designed and released by NTT DoCoMo, Japan’s largest wireless carrier. Designed to add a new stream of lucrative data revenues to the company’s portfolio, i-mode gave DoCoMo subscribers access to a curated version of the World Wide Web accessible from anywhere and everywhere (Steinberg, 2019). Though i-mode’s initial offerings focused on staid business applications like access to flight schedules and stock data, entertainment quickly became the service’s primary driver; within six months of i-mode’s launch, the “entertainment” category grew from representing about nine percent of i-mode’s library to over fifty percent (Funk, 2003, p. 28). Thanks largely to the popularity of these entertainment applications, and particularly games, i-Mode was a massive domestic success. By 2001 DoCoMo had exceeded its parent, NTT, in size and enjoyed a rate of return second only to Toyota in its home country of Japan (Peltokorpi, Nonaka, & Kodama, 2007). And it showed no signs of stopping: as one pair of contemporary analysts noted, i-mode put “the infamous hockey stick of growth … to shame” (Beck & Wade, 2003).

Key to DoCoMo’s success was the recognition that mobile players represent a fundamentally new, qualitatively different kind of media consumer. As Jussi Parikka and Jaakko Suominen (2006) have argued in one of the few mobile game histories written to date, mobile gaming does not merely consist of a new set of mobile technologies upon which human players act. Rather, drawing from Foucault, Parikka and Suominen point out that all technologies are also “cultural techniques” insofar as they necessarily incorporate “non-technological acts such as memory, thought, experience, affects” and other subjective qualities, which always “participate in technological assemblages” (n.p.). In the case of DoCoMo’s subscribers, these “non-technological acts” included everything their cultural investments in entertainment, the social bonds inscribed in their contacts lists and the technological knowledge required to operate the devices’ basic functions. Most importantly in the mobile context, however, were the learned habits surrounding mobile phone use. These users had not yet developed the preconscious habit of “checking” their phones on a regular basis, or of thinking of their phone as go-to device for information. I-mode, DoCoMo hoped, could change that.

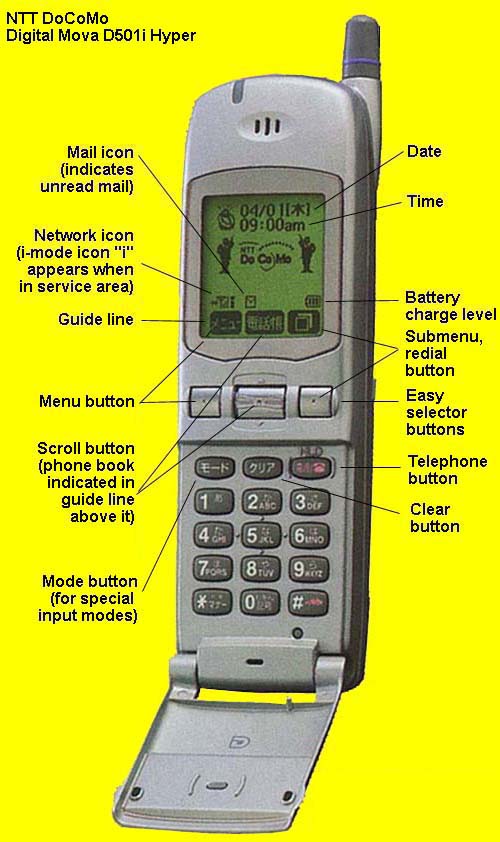

The i-mode game had to be small by both social and technical necessity. Early i-mode-ready phones had almost no processing power by today’s standards, typically topping out in 2002 around 500k of RAM [2]. On-board memory came even later; the phones that supported i-mode’s successor -- called i-appli -- only supported games up to about 50k in size, significantly smaller than even some Nintendo Entertainment System titles. On top of that, mobile users were expected to mostly interact with their devices on the go, in small bursts while waiting for a bus or standing in line at the supermarket. Even if it were feasible to fit a classic action game onto mobile phones, the public context meant that users’ attention would be split between the game and their surroundings, leaving inadequate cognitive resources for serious immersion in a game. As a result, DoCoMo characterized its service as being a kind of “konbini” (or convenience store) for software and information. DoCoMo VP Enoki Kei’ichi explained that the desktop internet resembled department stores” in that “You don’t go there very often. But when you go, you spend a lot of money” (qtd. in Gawer and Cusumano, 2002, p. 224). The convenience store, Enoki writes, is “just the opposite …You don’t buy lots of things. The variety is limited. But you go there every day” (ibid.). Mobile content might be “inferior to other media in terms of speed and screen size” but makes up for that “in terms of ease of use and convenience” (ibid.). Staying true to this “konbini” model, i-mode’s entertainment offerings traded large, robust experiences for small, simple ones. Like the snacks found at Tokyo’s ubiquitous convenience stores, i-mode’s games needed to be small, cheap and eminently bingeable.

Figure 1: The Anatomy of an i-mode handset. (Image by Ken Sakamura, accessed here on June 22, 2023).

A peak example of the kind of snackable game that i-mode incentivized was Bandai’s Mail de Koi Shite, or Love by Mail. In Love by Mail, players exchange flirtatious text messages with a virtual girl (or, after an early update, a boy) in the hopes of seducing their virtual sweethearts. The player begins by choosing from one of several “types” -- such as nurse, airline hostess, or several “Dutch wives” of famous idols -- to begin romancing. Once the game starts, players work to curry favor with the virtual partner of their choice by messaging them the appropriate messages at the appropriate rhythm. Rhythm is key to succeeding in Love by Mail, as neglecting the virtual love interest will invariably upset them and lower the player’s “score.” To succeed in Love by Mail, then, the player must internalize not only the kinds of messages that their new partner might enjoy, but also the very rhythm of the game itself. Unlike a console game that the player turns off and steps away from, a mobile game like Love by Mail “blends the real and the virtual” to give the impression that players’ AI partners “live in real time, in the same time as the player” (News24, n.d.). The game may not have challenged the players’ twitch reflexes like a shooter would, but it did require “constant dedication” (BBC News, 2001) on the part of the player, a genuine commitment to working the game into one’s everyday life and even to shaping one’s life around the game.

It is this new kind of imagined mobile player that am calling the mobile habitué. I define the mobile habitué as an ideal player type whose habitual, affectively charged relationship to their mobile device structures their relationship to the lifeworld. I use this term, “lifeworld,” in the phenomenological sense, i.e. to describe the way that the world is only ever accessible to the subject through experience. As the mobile phone becomes more and more central to users’ everyday lives, they increasingly experience the world as and through their phones. Unlike the terms hardcore and casual, which are best understood as design values that privilege one genre of games over another according to a set of cultural investments, the habitué is instead defined by a set of embodied, habitual relations to the cell phone as a platform. The habitué is presumed to have their cell phone on their person and powered on almost constantly, and is expected to have a learned, preconscious relationship with that device through which they find themselves reading messages, scanning the mobile web, or simply checking the time periodically through the day. As a central coordinating platform for modern social life, the habitué’s device also becomes freighted with a great deal of personal and emotional meaning, defined by then-innovative personalization features such as ringtones and wallpapers, to say nothing of the contacts and personal photos that fill the average cell phone memory (Gopinath, 2013). The centrality of things like wallpapers and contact lists also show us that the habitué is also a necessarily collective phenomenon; there is no habitué in isolation. Rather, the habitué finds themselves glued to their device precisely because they know that most of their friends and family members are also likely to own and use mobile phones as habitually as they do. After all, what’s the point of writing a text if its author is the only person who can expect to read it?

Of particular importance is the ostensible universality of the habitué. Unlike the highly gendered assumptions that inhere to the imagined hardcore or casual gamer, the imagined player of mobile games was -- and is -- anybody and everybody. Numerous contemporary studies found, for instance, that American women played mobile games at least as often as American men did (Dobson, 2006; Duffy, 2004; Koivisto, 2007). Analysts also found that while teens played the most mobile games of any age group, mobile games enjoyed broad appeal among older players as well, particularly compared with contemporary console titles. (Gamesindustry.biz, 2005). At least one study found that African Americans were twice as likely as other American ethnic demographics to play mobile games (Cifaldi, 2006). Perhaps most surprisingly (to the industry at least), study after study also found that while many gamers played mobile games on the go, plenty of mobile gamers also reported playing for hours on end at home, often in front of the television [3].

The mobile habitué cuts across just about every demographic and ludic category. After all, even self-avowed hardcore players turn to mobile games when nothing else is to hand. The authors of Mobile Game Development articulate this nicely:

Mobile gamers represent a class onto [sic] themselves; whatever other types of systems or consoles they may use, they become mobile gamers once they leave their homes -- restricted to short play sessions while waiting to pick up the kids, riding the bus, or handing out between classes … Regardless of gameplay habits while at home with a console or computer, the nature of mobile gaming instill similar play patterns across the board.” (Unger & Novak, 2011)

Naturally, the young American mobile industry struggled to understand exactly who this new kind of player was or what designs this player favored. The industry itself, it must be noted, did not label this new kind of player “the habitué” or much else; rather, how this new consumer class would act and why was up for intense debate within the early industry. This was particularly true once the mobile game industry came to the United States, where tech firms and telecom companies would expect concrete results from their new game industry partners.

Beyond Casual and Hardcore: Understanding the American Mobile Player

American wireless carriers quickly moved to emulate DoCoMo’s success. While some analysts cautioned that i-mode might not translate to the American context, their concerns were drowned out by a flurry of increasingly optimistic market forecasts. These reports promised extravagant returns on even minimal investments, touting that mobile games -- which did not yet even exist in the United States -- would grow into a $6 or even $7 billion global market by the end of 2005 (qtd. In Borzo, 2002; Halpern, 2003). Inspired by these tantalizing reiches, telcos like Sprint and newly formed Verizon [4] moved quickly to help fund a new class of American mobile games publishers, starting with JAMDAT Mobile, the first American mobile publisher, followed closely by publishers and developers like Sorrent (later Glu Mobile), THQ Mobile and Mforma (later Hands-On Mobile). This may seem curious to readers familiar with telcos’ infamous conservatism, but it was premised on the solid argument that the mass-market mobile phone was becoming so cheap, so popular, and so richly featured that it would become as integral to day-to-day life as the television, the Sony Walkman, or the home telephone [5]. The mobile phone’s ubiquity ensured a huge potential market for mobile contents, as it meant that games for mobile phones would enjoy an install base previously unknown in the history of digital games. As the editorial to the first issue of Game Developer Magazine devoted to mobile gaming pointed out, “Nokia sold 128 million mobile phones last year alone; it took Nintendo more than 10 years to sell 100 million Game Boys” (Olsen, 2001). The sheer size of a potential mobile games market was staggering, and the mobile game industry’s ideal user was anybody and everybody in the market -- or everybody with flush toilets, as Glu Mobile’s CEO once put it (Wisniewski, Ballard, Estanislao, & Miao, 2005).

The sheer scale of the mobile industry’s forecasts obscured a fundamental difference, however, between the carriers on one side and the game publishers and developers on the other. Where publishers and developers saw their games as ends to themselves, the American carriers, led by Sprint and Verizon, viewed mobile gaming as merely a driver of cell phone adoption and data plan revenues. The carriers had good reason to prioritize data revenues by 2001; that year, as JAMDAT was securing its first toe-hold as a publisher in the American market, the worldwide telecommunications industry suffered what would come to be known as the “telecoms crash.” Upwards of $1 trillion disappeared practically overnight in what The Economist (2002) called “the largest bubble in history,” estimated to be roughly “ten times bigger than the better-known dotcom crash” (p. 11). What was worse, voice telephony had plateaued among users, and a rapidly saturating mobile market meant that telcos increasingly had to resort to poaching subscribers from one another (Guy, 2003). As a result, the carriers found themselves “in a real bind without the data side of wireless,” as AT&T’s Jim Grams admitted that same year (Bellows, 2002).

Knowing that they needed to incentivize consumers to costly wireless data, the carriers pushed the new publishers and developers to maximize network usage in their game designs from the beginning. Yet by 2003, data revenues only made up about two percent to three percent of American carriers’ total revenues at a time when fifteen percent of European carriers’ annual earnings came from data (Brooks, 2003). While they might dictate design terms, the carriers also typically refused to furnish publishers with marketing resources, essentially dictating that publishers and developers market their own games or go without.

In the absence of serious marketing budgets but with the carriers pressuring them to develop highly profitable titles immediately, publishers doubled down on habituation strategies to create and then retain this new class of mobile player. In his bestselling (and morally ambivalent) Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products, Nir Eyal (2014) points out that “habit-forming companies,” of which he considers mobile gaming a leader, often turn to habit precisely because of this lack of funding for traditional advertising (p. 35). Instead, these companies “link their services to the user’s daily routines and emotions” in order to build their own habituation strategies on top of users’ existing practices. Early mobile ad companies might, for instance, exploit users’ learned aptitude for texting by messaging users about upcoming promotions rather than depending upon pricier, more passive TV commercials. As Eyal points out, “habits are not created, they are built upon.” Recognizing this, the early industry tied its marketing strategies to the mobile habitué’s rapidly reifying, embodied habits related to the mobile phone.

Winning Over Users: Marketing to the Habitué

With no marketing budgets and high pressures coming down from the carriers, companies like JAMDAT devised clever strategies for appealing to nascent habitués through the channels they had to hand. First among these marketing strategies was “embedding,” an arrangement by which publishers would contract with handset manufacturers like Nokia and Motorola to pre-load their games onto handsets at the point of manufacture. Potential players then had only to stumble upon the embedded game, boot it up (presumably out of curiosity) and then let the game’s accessible, habituation-focused design do its work. Austin Murray, one of JAMDAT’s founders and the key architect of its business model, explained the advantages of embedding for the entire mobile ecosystem:

Embedded games were probably the best advertising for us because a lot of people when onto their phone, and were looking for Snake, right? And oh, what is this thing next to Snake? This was when there were still folders on phones. People would get a new phone, going into the folders, “oh what’s here,” … “Oh I can go to this wireless, downloadable thing” (it was all new) and it would sit somewhere … on the phone … [embeds were] really an excellent place to be because [players would] play the game, get to level 2 or whatever, and they couldn’t play it and they’d have to click. “You want to play more? Click here!” And then it would take them to whatever the game or downloadable service was. (Murray, 2022)

At this time, carrier decks were low-information environments that often only included a game’s name by which to make a purchase; by getting the game in front of players, publishers hoped players would begin developing habitual pathways by clicking prior to understanding.

JAMDAT experimented with a number of other habit-focused strategies as well. In 2004, for instance, the company teamed with McDonalds to include JAMDAT games as prizes in the fast-food giant’s regular Monopoly Best Chance promotion (Staff, 2004). In 2005, JAMDAT arranged to have electronics retailer Radio Shack sell their games in Radio Shack stores in the hopes that consumers’ habitual relationship with retail experiences might encourage new users to try mobile gaming in a more comfortable, familiar environment (PR Newswire, 2005). In both cases, JAMDAT and its legacy partners understood that it could bootstrap consumer interest by simply exposing them to mobile games within the context of their existing shopping habits.

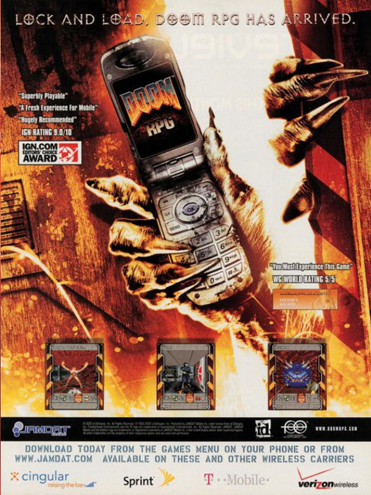

Though rare, JAMDAT and its competitors did also turn to conventional marketing at times to speak to specific audiences. Radio Shack and McDonalds could tap into a general audience, but the lucrative “core” gaming audience -- the only one to date with a proven track record of spending on games -- had its own habits that needed to be addressed. To reach this lucrative segment, JAMDAT and others took out glossy full-page ads in gaming magazines like Computer Gaming World and Electronic Gaming Monthly in order to tap into what Graeme Kirkpatrick has called the “gamer habitus” (2016, p. 1448) the system of normalized images, symbols and subjective norms that govern “acceptable” behavior in gaming circles. Consider for example the following ad for DOOM RPG (Fig. 2). As Kirkpatrick has it, this habitus has historically consisted of a set of cultural norms that transform the “uncool” act of computing into a “cool” act of media consumption by re-characterizing gamers into edgy, even countercultural figures who valued addiction as a form of dedication (ibid.). The DOOM RPG ad reinscribes these norms by contextualizing mobile games and mobile habit within this existing gamer framework. The words “Lock and Load… DOOM RPG has arrived” acknowledge that the reader already knows what DOOM and RPG games are and can be expected to desire them. Brightly colored images sit next to a demon smashing through the page, recontextualizing the potentially feminized subjectivity of the mobile habitué into the explicitly masculine form of the mobile gamer. Like the Radio Shack and McDonalds ads, however, the DOOM ad does ultimately conclude (at the bottom of the page) with information on where mobile games can be purchased, thus again presuming that new players will be carried away by the game’s habitual design once they’ve made the initial plunge.

Figure 2. A magazine ad for the JAMDAT-published DOOM RPG, designed by id’s John Carmack. (Source: Electronic Gaming monthly, accessed here on August 29, 2023).

Underpinning these strategies were some of gaming’s first forays into always-on data surveillance systems, designed to make the poorly understood habitué controllable and trackable through behavioral traces. The publishers led the way in this domain, as the wireless carriers proved predictably tight-lipped about their proprietary data, leaving JAMDAT and its ilk to develop data analytics systems in-house or to buy them from a middleware vendor (Calica, 2003a). These systems gave mobile publishers unprecedented access to players’ behaviors at a micro-level, opening up huge potential to A/B test their products into their most habit-friendly forms. Nanea Reeves (2023), the primary architect behind JAMDAT’s system, explained to me in an interview that “Data analytics is a way to have a conversation with your consumer directly, just through the way they move through your product.” At JAMDAT, Reeves and her team “did a lot of analysis on click data,” that is, data on what links users click within the game, how often and in what order. Using this method, Reeves found that “almost 30% of our revenue came from those demos with the links to buy” and another 12-15% “from those in-game links where we were cross-selling, you know, so it was kind of like a little mini-store within the store” without having to return to the carrier’s deck. This data had real implications for design and marketing. When at one point another faction within JAMDAT wanted to remove the cross-selling links to reduce testing overhead, Reeves had data to show the effectiveness of their strategy: “I was able to show up with the data in the meeting and say to [JAMDAT CEO] Mitch [Lasky]: look how much this is generating! It’s not okay to take that link out … it was more testing overhead but you couldn’t argue once you saw the data, like look how many people are clicking on that!” Naturally, the cross-selling links stayed.

Through the 2000s, then, publishers realized that mobile players represented a new kind of player that needed to be addressed and appealed to through the habituated design of the games themselves. By offering players embedded games, multi-brand marketing campaigns and campaigns keyed into existing gamer habits, the industry hoped that it could impel consumers to overcome their apathy by simply trying mobile games. Once the players were inside the mobile game ecosystem, it was hoped, they would find the experiences offered there so compelling -- so addicting -- that they would become permanent mobile gamers.

Ubiquity and Mobility: Designing Games for the Habitué

The mobile game industry felt confident that they could develop compelling, habit-forming games. The obvious next question is: how? What strategies did they apply to the games themselves to encourage and maintain habituation? And how did they go about discussing and theorizing this new kind of design?

At first, the American mobile game industry argued, as we saw above, that habitual design meant casual design. JAMDAT, unsurprisingly, championed this approach. The company had been co-founded by a man named Scott Lahman, who had previously served as head of Activision’s casual games division, and he had seen how casual games had grown into a highly profitable market by the end of the 1990s (Lahman, 2011). For companies like JAMDAT, casual games’ approachable designs and short, satisfying gameplay loops seemed like the perfect fit for mobile. Most of JAMDAT’s early successes are uncomplicatedly “casual” in their design, like Gladiator (a simple rock-paper-scissors game), JAMDAT Bowling, the Hasbro tie-in Yahtzee Deluxe, lifestyle games in the vein of Tamogatchi, and an endless parade of virtually identical solitaire and poker games.

Some companies felt that the casual route was too risky. Sorrent founder Scott Orr, for instance, argued that the industry needed to appeal first to the early adopters associated with the hardcore market. Orr unequivocally rejected casual design as too risky a consumer base, saying “We build for people who grew up with Game Boy, not some mythical mass market that may or may not buy games” (Calica, 2003b). These firms prioritized the focus on challenge and skill associated with the traditional console and PC markets. For the hardcore crowd, developers rereleased old arcade titles like Space Invaders and Pac-Man, brought popular console franchises like Splinter Cell to the mobile phone, and adapted traditional genres like the turn-based strategy and the RPG to the mobile context [6].

The tidy hardcore/casual binary began to break down almost immediately. Developers found that their ideal user -- the mobile habitué -- refused to conform to either category. Despite its commitment to casual games, JAMDAT also moved to include more traditionally hardcore offerings in its catalog soon after its launch. Such selections included its Lord of the Rings movie tie-in games, which designer Ralph Barbagallo modeled off the popular Shining Force series of strategy RPGs (Barbagallo, 2022). JAMDAT also produced the aforementioned DOOM RPG, whose play and advertising could not be any more “hardcore” in its identity. Sorrent went just the opposite direction. In 2003, Sorrent’s board ousted Scott Orr and brought in a new CEO in Greg Ballard, whose first major decision was to pivot more toward casual design in explicit contradiction to Orr’s entire market strategy (Ballard, 2022).

As the 2000s wore on, however, analysts began pushing developers to expand their horizons by thinking above and beyond the casual/hardcore binary for the reasons listed above: that the mobile gamer was both casual and hardcore in its demographics and gameplay preferences. Dan Orum, CEO of IDG Entertainment, the publisher of Gamepro Magazine, liked to call this new blended gaming subjectivity the “social gamer.” This social gamer could be understood as “like the typical ‘hardcore gamer,’ but with social lives,” as Orum put it (Cifaldi, 2006). That is, this new player could be expected to play as often and as intensely as a “hardcore gamer” but in new, less solitary ways.

This new player, with all its contradictions, required new kinds of games. The design norms often associated with habituation today -- from energy systems to push notifications and beyond -- first appeared in this moment, as the industry began to mix and blend strategies that had been associated with either hardcore or casual gaming in novel ways. From the hardcore industry came a long history of gameplay mechanics, techniques for encouraging competition (such as the evergreen high score board) and a rapidly maturing body of social design for online games. The casual side furnished a number of broadly useful strategies as well, including more flexible gameplay mechanics that made mobile games easier to pick up and put down, mechanics that prioritized time and attention over skill and challenge (again inspired by Tamogatchi) and entirely new genres that were particularly well-suited to the feature phone’s fiddly inputs. Companies like the Korean Gamevil, for instance, produced a series of “single-button” games that married the difficult timing challenges of more hardcore games with the accessibility of casual by reducing all interaction to a single key-press [7].

I want to emphasize that these strategies represented a blend of what might be called gameplay designs and metagame designs. The metagame designs gamified the game itself in order to, as then-mobile-developer Greg Costikyan (2002) claimed, “lead to obsessive, repeat play” by rewarding that repeat play with some sort of benefit. The high score board that we associate with arcades is a textbook example. The inclusion of high score boards in arcade titles did not affect the gameplay itself -- one cannot fly through blowing up competitors names and scores, satisfying as that might be -- but instead serves to structure the meaning and practices associated with gameplay by placing them in a broader sociotechnical context. Simply by allowing players to advertise their virtuosity, high score boards encouraged intra-arcade rivalries, gave rise to culturally specific naming conventions, helped establish gaming’s long association with professional sports [8]. The early industry hoped that metagame strategies like the leader board, transplanted from the arcade to the phone, would help drive habituation by encouraging social investment. Mobile developers, for instance, often included leader boards in their games that consisted only of a player’s immediate mobile network, allowing them to send exceptional scores to their real-life friends and rivals (Kivikangus, 2006).

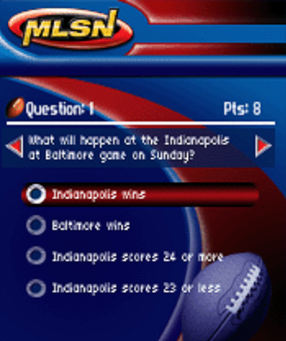

As I see it, four habituation strategies prevailed in this era: repetition, variable reward, social pressure and accumulation. Repetition forms the core of all habit and all habit-formation; as Wendy Hui Kyong Chun (2016) points out, habits themselves are little more than “creative anticipations based on past repetitions” (p. 3). Games of this era encouraged repetition in myriad ways. Some, like Love by Mail, addressed the player regularly in real time, encouraging players to internalize the rhythms of the games. Others, like Digital Chocolate’s MLSN Sports Book, tasked players with predicting upcoming sports results every week, laying their game’s rhythms over the sports fan’s regular interactions with sports schedules. Variable rewards, the soul of gambling’s pleasures, “create a focused state, which suppresses the areas of the brain associated with judgment and reason while activating the parts associated with wanting and desire” (Eyal, 2014, p. 9). In the business plan for Digital Chocolate, founder Trip Hawkins (2003) argued that mobile content should resemble Magic the Gathering and The Pokémon Trading Card Game in their combination of random lottery elements and personal investment reinforced by what he calls, after Wizards of the Coast (owners of Magic), “intermittent reinforcement” (p. 18). The key, he writes, is “combining the slot machine model with low impulse price,” which all but guarantees “a sense of community, emotional attachment to the characters or objects, impulse purchasing, and compulsive behavior” among users. The third category, social pressure, leverages networked sociality to encourage consumption. Eyal (2014) labels these social drivers of habituation “the rewards of the tribe,” gameplay experiences “that make us feel accepted, attractive, important, and included” (p. 100). The actual design implementations of these pleasures might entail anything from a high score board to track competition to in-game messaging to real-time multiplayer and beyond. Accumulation, finally, feeds into what Hawkins calls “the investment thesis” and what Eyal calls simply “investment.” In the latter’s terms, investment involves giving users the power to “[improve] the service for the next go-around” (p. 10). In early mobile, this might for instance include asynchronous game events that respond to player actions between play sessions, mobile games featuring linear progress through leveling or gold, as well as persistent social guilds inspired by the MMORPGs of the 2000s.

Figure 3. A screenshot of MLSN Sports Picks’ simple, menu-based gameplay. (Source: IGN, accessed here on September 27, 2023).

Figure 4. A virtual trophy awarded to a player. (Source: IGN, accessed here on September 27, 2023).

All four of these strategies are elegantly combined in Digital Chocolate’s 2007 game, DChoc Café. In the words of Digital Chocolate founder Trip Hawkins (2007), players of DChoc Café “personalize their own virtual cafe shops as well as avatars representing themselves and their friends, all while playing high-quality casual games like DChoc Café Solitaire, DChoch Café Sudoku, DChoc Café Kakuro and DChoc Café Mahjong. They can play games together or play different games while competing to win and unlock the same treasured and rare shirt for their avatar to display.” In a rarity for a time of high data rates and low network dependability, Hawkins saw DChoc Café less as a “game” than a social experience. The social pressure element here should be obvious. A contemporary review also reveals how Digital Chocolate reinforced the social habituation with the logics of repetition and accumulation/investment. Levi Buchanan (2007) writes: “I logged in this morning to discover my tiny, quaint one-star rated starter cafe was suddenly a two-tier coffee house with a three-star rating because two friends had joined in, played games, and participated in activities such as exchanging greetings with my avatar. That, dear reader, is very cool and surprisingly addictive.” Repetition is also baked in, since the player’s friends’ activities will continue to reshape the game in the player’s absence, incentivizing the player’s return multiple times a day.

Figure 5: Customized avatars socializing in a player’s customized café in DChoc Café. (Source: IGN, accessed here on September 27, 2023).

The early industry’s deployment of these innovative strategies brought mixed results. On the one hand, the industry struggled mightily through the late 2000s to “hook” new users despite their best efforts. By 2005, analysts were growing increasingly anxious about the industry’s struggle to overcome user apathy. In a country with well over 200 million cell phone subscribers (Taylor, 2013), only about fifteen million had played a mobile game and a paltry 3.9 million had actually paid for a mobile game by the last quarter of 2006 (Diamante, 2006). The news was not all doom and gloom, though, particularly for JAMDAT. In 2004 IGN ran the simple headline “JAMDAT Makes Money” to celebrate the company’s first profitable quarter in 2004 (SEC, 2004). That same year, JAMDAT successfully went public, raised 40% over its initial valuation (Jenkins, 2004) and used those funds to acquire Blue Lava Wireless, the holder of the Tetris license (Jenkins, 2005). With the exclusive rights to the evergreen Tetris, JAMDAT became enormously valuable, and by the end of 2005 Electronic Arts had purchased the company for an eye-watering $680 million (Maragos and Carless, 2005). A 2006 study by Sprint found that over half of mobile phone subscribers expressed a strong interest in mobile gaming (Loughrey, 2006). The future was looking bright for mobile games.

The JAMDAT acquisition signaled to the rest of the industry that the wild west days of early mobile were ending, and that the giants of the console and PC worlds would soon move in to capture the market. Mitch Lasky, CEO of JAMDAT, joined EA as Senior Vice President of EA Mobile in 2006, and gave a keynote speech at that year’s Game Developer Conference provocatively titled “The Future of Mobile Gaming and Its Enemies.” In his speech, Lasky declared that the problem with the industry was the glut of backwards distribution models and “bad games” that could only be burned away by a truly monolithic central authority -- that is, by a now hegemonically powerful EA Mobile.

2007 marked two significant turning points for the young industry. First, the Apple iPhone was released. Second, the industry hit its tenth anniversary, the ten-year mark from the release of Snake in 1997. The industry took this as an opportunity to reflect on its progress, and generally found that its habituation strategy and its targeting of the amorphous figure of the habitué had paid off. For one industry veteran, Chris Wright, the iPhone even marked the moment at which the technology caught up with the habitué. For Wright (2009), the previous ten years had proven the idea “that mobile games can be fun,” and with the iPhone “we seeing are devices that give users what they want.” A study funded by Nokia, then at the height of its powers as a manufacturer, endeavored to normalize the unspoken focus on habituation by predicting that “snack gaming,” as they referred to the lightweight mobile games of the era, “will be there and they may even drive the industry” (Koivisto, 2007, p. 6). For Nokia’s researchers, the reason was clear: in the future, “more people than today [will] have been using a mobile phone for their entire life,” and these mobile natives could be expected to have “a different, more pervasive relationship with the mobile phone,” in which they see “the mobile phone as a tool in everyday playing” (p. 5). The true victory of the mobile phone was to be its complete fusion with the body of its users, producing a set of increasingly “natural” habits mediating between user and world.

Conclusion

On January 9, 2007, a hushed MacWorld crowd watched as Steve Jobs, the very face of tech sector success, took the stage to announce Apple Computer’s new product: a smartphone that Jobs called the “iPhone.” The scale of Apple’s ambitions became clear by the end of Jobs’ presentation, when he announced that Apple Computer would now simply be called “Apple” to reflect the centrality of mobile computing to Apple’s business going forward. . The tech world raced to announce that the future had once again arrived and proclaimed the iPhone “the biggest launch since the Apollo program” (Wired, 2007). This ostensibly revolutionary moment continues to define thinking about mobile today; everything that came before was mere prelude.

Despite the revolutionary discourse around the iPhone, however, the same strategies that defined early mobile continued to define the earliest success stories in the smartphone era, typically by employing the same habituation strategies for the same, habituated users. The smartphone’s first real success story, the Finnish Rovio’s Angry Birds, was strongly inspired by another Finnish game called Johnny Crash, developed by Sumea, in which players launch a hapless stunt man through and at various obstacles. Though many forces shaped Angry Birds and its surprise success, many of these same habitual designs can be seen at play in it. The game awards players up to three stars based on their performance, while a later update added hidden golden eggs to existing stages, encouraging repetition through replayability. The game’s unlockable content encouraged players to accumulate the games’ variable rewards. Other platform-defining games like Candy Crush Saga attest to early mobile’s relevance with equal force, as Candy Crush essentially cloned JAMDAT’s earlier Bejeweled Multiplayer while adding the network elements of Zynga’s other social network titles like Farmville. And above all, mobile games continued to primarily offer small, snackable games in the same way that i-mode had over twenty years ago.

Figure 6. Johnny Crash launches out of his canon. (Source: Digitalchocolate.com, accessed here on September 13, 2023).

Today we are nearly all mobile habitués. Our smartphones accompany us wherever we go. We stage our entire lives through them. We suddenly find ourselves scrolling through Facebook or Instagram with no memory of opening the app. App developers increasingly incorporate new mechanisms like icon badges, push notifications and the like not to habituate, but to reinforce the habits we have already internalized. Naturally, the intensification of mobile phone use and fifteen years of smartphone adoption have produced a corresponding intensification of habituation strategies. The randomization of early game rewards so central to Hawkins’ thinking has reached a kind of apotheosis in today’s lootboxes. Network improvements have led to more robust social components in games, particularly as mobile ports of major franchises like League of Legends and Fortnite have made the jump to mobile phones, with the result that children in all online games are finding themselves the targets of harassment for not having the latest skins (Zwiezen, 2024). Whole genres of mobile games offer players the fun of accumulation as well, from lifestyle games like Nintendo’s Animal Crossing: Pocket Camp to collection-focused games like Magic the Gathering: Arena and Hearthstone. And repetition is challenging to exemplify because of its sheer ubiquity, but we can nevertheless point to the recent popularity of idle and clicker games as compelling evidence of repetition’s continued relevance for mobile gaming.

Mobile game companies, in the 2000s and today, have shaped the way the public thinks about technology in order to present commercial products as natural and inevitable, and to naturalize these habituation strategies as the straightforward realization of users’ desires. This is an old trick, and one that allows these companies to hoard technological agency in the hands of a few powerful firms whose interests may diverge from those of their customers. But those firms also struggle to enact their agenda; it is they who must convince the “mythical masses” that their future is THE future, not the other way around. The appearance of technology as a self-identical “thing” is only the product of marketing rhetoric, which, like Marx’s commodity fetishism, obscures the social relations underlying a given technology’s social existence. As the philosopher of technology Andrew Feenberg (1991) has so eloquently argued, technology “is not a destiny but a scene of struggle … a social battlefield … on which civilizational alternatives are debated and decided” (p. 14). The mobile phone is itself a battlefield, one on which radically divergent visions for our technological and cultural futures compete to define the future every day. It can seem like tech companies hold all the power, but that too is an illusion sustained with great effort and at great expense by those self-same companies. Our mobile lives can be otherwise. We have only to look back to the industry’s own history to articulate a better, healthier future for the future.

Endnotes

[1] The current inductees can be seen here: https://www.museumofplay.org/exhibits/world-video-game-hall-of-fame/inducted-games/.

[2] The presentation this is taken from can be found archived on Costikyan’s personal website: http://www.costik.com/presentations/wrlsdes.ppt

[3] This is corroborated by Juul’s research into other domains of casual video game play (Juul, 2010, p. 8).

[4] Verizon was formed in 2000 by the merger of several of the post-monopoly “baby Bells” and the British Vodafone.

[5] Nokia was one of the earliest companies to recognize the shift in the cell phone from a utilitarian device to a “cultural good” defined by the cell phone’s social capacities and cultural meanings rather than its technical specifications. See (Doz & Keeley, 2018, p. 83).

[6] Turn-based design of the sort that predominated in RPGs and strategy games was ideal for the mobile phone, as underpowered handsets did not have to struggle to render real-time action. This was particularly true for multiplayer titles, where high latency essentially restricted titles to turn-based gameplay (see Palm, 2003).

[7] It bears noting that Gamevil’s single button titles are an obvious forebear to contemporary single tap games like Flappy Bird, Super Mario Run and Alto’s Adventure.

[8] For this history, see (Kocurek, 2015).

References

Ballard, G. (2022). Personal Interview. February 9, 2022.

Barbagallo, R. (2022). Personal Interview. December 15, 2022.

BBC News. (2001, February 13). Virtual Love seduces Japan. BBC. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/1168315.stm

Beck, J. C., & Wade, M. (2003). DoCoMo: Japan's Wireless Tsunami: how One Mobile Telecom Created a New Market and Became a Global Force. Amacom Books.

Bellows, M. (2002, April 11). AT&T Wireless -- Talking the Wireless Gaming Talk. Wireless Gaming Review. https://web.archive.org/web/20050405090929/http://wgamer.com/articles/att041102

Borzo, J. (2002, March 5). Phone Fun: Mobile Entertainment, Wherever You Are. Wall Street Journal.

Brooks, D. (2003). VZW Analyst Day: Data Revenues On The Rise. Mobile Entertainment Analyst, 2(12), 1-4.

Buchanan, L. (2007, August 10). Digital Chocolate Cafe Games Review. IGN. https://www.ign.com/articles/2007/08/10/digital-chocolate-cafe-games-review

Calica, B. (2003a, April). On handset data. Game Developer Mobile.

Calica, B. (2003b, April). Sorrent Profile. Game Developer Mobile.

Chun, W. H. (2016). Updating to remain the same: Habitual new media. MIT press.

Cifaldi, F. (2006, January 27). The Future of Mobile Games - CES panelists on mobile opportunities. Game Developer. Retrieved February 14, 2023, from https://www.gamedeveloper.com/business/the-future-of-mobile-games---ces-panelists-on-mobile-opportunities

Consalvo, M., & Paul, C. A. (2019). Real Games: What's Legitimate and What's Not in Contemporary Videogames. MIT Press.

Cooley, Heidi Rae. (2014). Finding Augusta: Habits of mobility and governance in the digital era. Dartmouth College Press.

Costikyan, G. (2002). Wireless Game Design. Retrieved March 8, 2024, from http://www.costik.com/presentations/index.html

Davis, J. (2013, July 29). “Why Core Gamers Hate Free-to-Play.” IGN, www.ign.com/articles/2013/07/29/why-core-gamers-hate-free-to-play

Diamante, V. (2006, September 13). Mecca: “optimists” and “pessimists” talk mobile. Game Developer. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/game-platforms/mecca-optimists-and-pessimists-talk-mobile

Dobson, J. (2006, August). Women Driving Mobile Market. Game Developer Magazine, 13(7), 7.

Donovan, T. (2010). Replay: The history of video games. Yellow Ant.

Doz, Y., & Wilson, K. (2017). Ringtone: Exploring the rise and fall of Nokia in mobile phones. Oxford University Press.

Duffy, J. (2004, July 1). Mobile Games Demographics. Game Developer. Retrieved February 14, 2023, from https://www.gamedeveloper.com/pc/mobile-games-demographics

The Economist. (2002, July 20). The great telecoms crash. The Economist.

Ekbia, H. R., & Nardi, B. A. (2017). Heteromation, and other stories of computing and capitalism. MIT Press.

Epic Games. (2017). Fortnite [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game published by Epic Games.

Eyal, N. (2014). Hooked: How to build habit-forming products. Penguin.

Feenberg, A. (1991). Critical theory of technology (Vol. 5). Oxford University Press.

Funk, J. L. (2003). Mobile disruption: the technologies and applications driving the mobile Internet. John Wiley & Sons.

Gamesindustry.biz. (2005, September 14). M:metrics' industry analysis. GamesIndustry.biz. Retrieved February 14, 2023, from https://www.gamesindustry.biz/m-metrics-industry-analysis

Gawer, A., & Cusumano, M. A. (2002). Platform leadership: How Intel, Microsoft, and Cisco drive industry innovation. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Gopinath, S. (2013). The ringtone dialectic: Economy and cultural form. MIT Press.

Guins, R. (2017). New… Now?: Or Why a Design History of Coin-Op Video Game Machines. American Journal of Play, 10(1), 20-51.

Guins, R. (2020). Atari Design: Impressions on Coin-Operated Video Game Machines. Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

Guy, A. (2003). Handsets are Selling but Net Additions are Crawling. Mobile Entertainment Analyst, 2(2), 7-13.

Halpern, J. J. (2003). Advertisers Exploring the Mobile Medium. Mobile Entertainment Analyst, 2(10), 1-7.

Hawkins, T. (2003, October 17). Digital Chocolate Business Plan.

Hawkins, T. (2007, August 13). Editorial: Looking for the next Mobile Gaming Killer App. Game Developer. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/mobile/editorial-looking-for-the-next-mobile-gaming-killer-app

Huhtamo, E. (2005). Slots of Fun, Slots of Trouble: An Archaeology of Arcade Gaming. In J. Raessens & J. Goldstein (Eds.), Handbook of Computer Game Studies (pp. 1-21), MIT Press.

JAMDAT. (2001). Gladiator [WAP]. Digital game published by JAMDAT Mobile.

Jenkins, D. (2004, September 29). Jamdat IPO exceeds expectations. Game Developer. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/game-platforms/jamdat-ipo-exceeds-expectations

Jenkins, D. (2005, April 20). Jamdat acquires Blue Lava, Tetris Wireless License. Game Developer. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/game-platforms/jamdat-acquires-blue-lava-i-tetris-i-wireless-license

Juul, J. (2010). A casual revolution: Reinventing video games and their players. MIT press.

Kivikangus, T. (2006). Creating Original Character-Based Brands and IP: A Postmortem on Johnny Crash. In GDC Vault. Retrieved March 8, 2024, from https://www.gdcvault.com/play/1013263/Creating-Original-Character-Based-Brands

Kocurek, C. A. (2015). Coin-operated Americans: Rebooting boyhood at the video game arcade. U of Minnesota Press.

Koivisto, E. (2007). (rep.). Mobile Games 2010 (pp. 3-21). Nokia.

Kuperczko, D., Kenyeres, P., Darnai, G., Kovacs, N., & Janszky, J. (2022). Sudden gamer death: non-violent death cases linked to playing video games. BMC psychiatry, 22(1), 824. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04373-5

Lahman, S. (2011). GOGII, JAMDAT And The Unknown Heavyweight. Mixergy. other. Retrieved from https://mixergy.com/interviews/scott-lahman-gogii-interview/

Loughrey, P. (2006, January 19). Sprint releases wireless consumer usage report. mobileindustry.biz. https://web.archive.org/web/20060219091015/http://www.mobileindustry.biz/article.php?article_id=1015

Maragos, N., & Carless, S. (2005, December 7). Electronic Arts buys Jamdat Mobile. Game Developer. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/game-platforms/electronic-arts-buys-jamdat-mobile

Marley, P. (2005, May 4). Feature: Mobile Postmortem: Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure. Game Developer. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/game-platforms/feature-mobile-postmortem-i-bill-ted-s-excellent-adventure-i-

Murray, A. (2022). Personal Interview. September 20, 2022.

Newtoy. (2008). Words with Friends [Apple iOS]. McKinney, Texas.

News24. (n.d.). Virtual love for lonely men. https://www.news24.com/news24/virtual-love-for-lonely-men-20010213

Niantic. (2016). Pokémon Go [Apple iOS,]. Digital game published by Niantic.

Nooney, L. (2013). A pedestal, a table, a love letter: Archaeologies of gender in videogame history. Game Studies, 13(2). https://gamestudies.org/1302/articles/nooney

Olsen, J. (2001, November). Brave small world. Game Developer Magazine, 5-5.

Palm, T. (2003). The Birth of the Mobile MMOG. In GDC Vault. Retrieved March 8, 2024, from https://www.gamedeveloper.com/design/the-birth-of-the-mobile-mmog

Parikka, J., & Suominen, J. (2006). Victorian snakes? Towards a cultural history of mobile games and the experience of movement. Game Studies, 6(1). https://gamestudies.org/0601/articles/parikka_suominen

Paul, C. A. (2018). The toxic meritocracy of video games: Why gaming culture is the worst. U of Minnesota Press.

Paul, C. A. (2020). Free-to-Play. MIT Press.

Peltokorpi, V., Nonaka, I., & Kodama, M. (2007). NTT DoCoMo's launch of I‐mode in the Japanese mobile phone market: A knowledge creation perspective. Journal of Management Studies, 44(1), 50-72.

PR Newswire. (2005, August 1). Game On! RadioShack, JAMDAT Mobile Team Up to Bring Mobile Gaming to Neighborhoods Across the United States. Forbes. https://web.archive.org/web/20050803234057/http://www.forbes.com/ prnewswire/feeds/prnewswire/2005/08/01/prnewswire200508011932PR_ NEWS_B_SWT_DA_DAM055.html

Reeves, N. (2023). Personal Interview. May 30, 2023.

Riot Games. (2009). League of Legends [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game published by Riot Games.

SEC. (2004). “Jamdat Mobile Inc IPO Investment Prospectus S-1.” SEC.report. https://sec.report/Document/0001047469-04-022471/

Sennari Interactive. (2002). JAMDAT Bowling [BREW, J2ME]. Digital game published by JAMDAT Mobile.

Sinclair, B. (2019, May 8). US legislator proposes Loot Box Ban. GamesIndustry.biz. https://www.gamesindustry.biz/us-legislator-proposes-loot-box-ban

Siu, W. (2022, October 2). I make video games. i won’t let my daughters play them. The New York Times.

Staff. (2004, October 29). Jamdat Mobile to provide prizes for Monopoly best chance game 2.0 at McDonald’s. GamesIndustry.biz. https://www.gamesindustry.biz/jamdat-mobile-to-provide-prizes-for-monopolytm-best-chance-game-20-at-mcdonaldstm

Steinberg, M. (2019). The platform economy: How Japan transformed the consumer internet. U of Minnesota Press.

Suominen, J. (2017). How to present the history of digital games: Enthusiast, emancipatory, genealogical, and pathological approaches. Games and Culture, 12(6), 544-562.

Supercell. (2012). Clash of Clans [Apple iOS,]. Digital game published by Supercell.

Švelch, J. (2018). Gaming the iron curtain: How teenagers and amateurs in communist Czechoslovakia claimed the medium of computer games. MIT Press.

Swalwell, M. (2021). Homebrew Gaming and the Beginnings of Vernacular Digitality. MIT Press.

Taylor, P. (2013, March 21). Mobile wireless penetration rate in the U.S. 2001-2011. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/184946/estimated-mobile-wireless-penetration-rate-in-the-us-since-2001-nruf/

Unger, K., & Novak, J. (2011). Game development essentials: Mobile game development. Delmar Learning.

Vaidhyanathan, S. (2018). Antisocial media: How Facebook disconnects us and undermines democracy. Oxford University Press.

Waugh, E.-J. (2006, March 30). GDC Mobile: The Future of Mobile Gaming and its enemies. Game Developer. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/business/gdc-mobile-the-future-of-mobile-gaming-and-its-enemies

Wijman, Tom. (2022, January 13). The Games Market and beyond in 2021: The Year in Numbers. Newzoo. https://newzoo.com/insights/articles/the-games-market-in-2021-the-year-in-numbers-esports-cloud-gaming

Wired. (2007, September 10). iPhone. Wired Geekipedia. https://web.archive.org/web/20081013225735/wired.com/culture/ geekipedia/magazine/geekipedia/iphone

Wisniewski, D., Ballard, G., Estanislao, J., & Miao, O. (2005). The State of the Mobile Game Industry. In GDC Vault. Retrieved February 1, 2023, from https://www.gdcvault.com/play/1020320/The-State-of-the-Mobile

Wright, C. (2009, January 2). A brief history of mobile games: 2007/8 - thank god for Steve Jobs. pocketgamer.biz. https://www.pocketgamer.biz/feature/10723/a-brief-history-of-mobile-games-20078-thank-god-for-steve-jobs/

Zwiezen, Z. (2024, February 27). New study shows kids are bullied for not spending money in free-to-play games. Kotaku. https://kotaku.com/study-fortnite-free-to-play-games-kids-bullied-f2p-1851291618