Playing with Gender: Women in Assassin's Creed Odyssey

by Lina Eklund, Anna Foka, Johan VekseliusAbstract

When video games have historical settings, what is known of the past and how this is interpreted with eyes of the present time shapes our gameplay experience. As the past is always reinterpreted and reshaped -- informed by contemporary concerns -- playing historical games becomes a two-way dialogue between history and the now. In this study we explore this dialogue through the lens of Ubisoft’s (2018) Assassin’s Creed Odyssey (ACO), focusing on the doing of gender and sexuality as constructs which vary through place and time. Through close playing, we examine how gender comes to be ergodically through playing with gender by combining the scholarly perspectives of game studies and ancient history.

We argue that the position of modern video game players, with their contemporary values and experiences of doing gender, combine with ‘player choice’ as a core value in modern game development to impact what kinds of historical reconstructions are available for game developers. Our main case study, ACO, avoids making players perform gender practices of the past that clash with modern values. This concerns the characterisation of the female protagonist, representation of other women in the game and representations of sexuality through the game's narrative, aesthetics and game mechanics. Finally, we argue that games like the Assassin's Creed series are leveraging history to tell exciting stories. Yet, the gendered story ACO tells could have been made considerably more interesting by drawing on the ways that gender has been done in history, rather than, as is now, erasing the historical power positions women have inhabited.

Keywords: video games, computer games, gender, sexuality, history, Classical Greece, ergodic, close playing

Introduction

Gender, its performance and representation, is central and contested in contemporary game culture (Cassell & Jenkins, 1998; Kafai et al., 2008; Kafai et al., 2016). Video games represent, perform, or even play gender in complex processes where game context, genre conventions, fan cultures and other social processes are involved through the design (Ibid.). When video games play out in history, complexity is added by what is known of that past and how that is interpreted with contemporary eyes (Chapman et al., 2017). Playing with history through engaging with games that draw on historical settings may act as a learning process and a connecting tissue between otherwise geographically and chronologically disparate cultures and times. It can offer alternative perspectives on historical practices such as gender -- perspectives by which to understand and interpret contemporary societies and experiences. The past is always reinterpreted, reshaped and informed by contemporary concerns. We explore this two-way dialogue between history and contemporaneity through the lens of Ubisoft’s (2018) Assassin’s Creed Odyssey (hereafter ACO), by focusing on the representation of the female protagonist Kassandra. We ask: how is historical gender and sexuality played, performed and portrayed within ACO as a contemporary commercial medium? What are the complexities that surround female historical gender and sexuality in contemporary play?

Ubisoft’s action roleplaying game Assassin’s Creed is one of the more famous history-inspired video game series. In it, players visit various eras, exploring and playing in historical milieus such as Renaissance Italy or Revolutionary Paris. In 2014, Assassin’s Creed Unity had an infamously poor release, with deficient gameplay balance and graphical errors that rendered it nearly unplayable. However, what stuck in the minds of many fans at the time were comments made by Unity’s creative director Alex Amancio’s and level designer Bruno St-André defending against criticisms that none of the game’s four playable characters were women. They claimed that women characters are too hard to animate, suggesting that the game’s production timeline could not accommodate playable female characters. Ubisoft attempted to mend the damage this caused the franchise by providing the option of a female playable character in Assassin’s Creed Odyssey (2018) and declaring her to be the canonical main character.

ACO takes place in the classical period of ancient Greek history during the Peloponnesian War, roughly 431-422 BC. This period in history has fascinated scholars and enthusiasts and is a common setting for popular culture endeavours. When it comes to representations of ancient Greek culture and society in contemporary popular culture, these are typically open to speculation and imagination. Literary sources and archaeology provide only partial images of antiquity and are in need of interpretation and reconstruction (Schaps, 2010). Literary texts from the ancient world constitute fragmentary evidence; of special relevance to this study is the fact that ancient texts about women were written by wealthy, educated men and were later appropriated to fit antiquarian and scholarly narratives and contexts (Beard, 2017). In short, we know more about male Greek (and especially Athenian) citizens and their worldviews, and less about the lives, appearance and behaviours of other groups.

This article builds from a Butlerian theory of gender and sexuality as intertwined and performed by variously coded bodies (1990), and we apply Espen Aarseth’s “ergodic” concept (1997) to ACO as we explore the doing of female characters in the game’s ancient world. The term “ergodic” comes from ergo (from Greek: deed, act) and hôdos, route or road. Aarseth applies this notion of a “working path” to describe the ontology of configurative texts like hypertext fiction and videogames. Looking at ACO as an ergodic text, we focus on what T. L. Taylor calls “assemblages of play,” the view that games are constituted through the intertwining acts of players, software, design, as well as cultural and historical contexts (Taylor, 2009). Our method includes exploring the game through close playing (Bizzocchi & Tanenbaum, 2011) as Odyssey’s female main character Kassandra of Sparta, an approach we detail below.

This article offers a novel, twofold examination of how women and historicity are represented in video games. Moving beyond the study of games and gender, we apply ergodicity and historical inquiry to examine how historical gender comes to be through playing contemporary video games. ACO is a particularly good case study due to the criticism levied against Ubisoft mentioned above and because Kassandra is the first canonically female character in a main series Assassin’s Creed game.

In this article, we argue that video game players are positioned through playable characters like Kassandra to bring their contemporary cultural values and expressive choices to bear on genders of the past. The contemporary values of video game design foregrounding player choice are in tension with attempts at virtual historical reconstructions. How we today look at free choice is complicated in a historical seeing where players embody people who’s agency is limited by social structures; such as women in this period. In our case, player choice thus forecloses players from any meaningful or authentic performance of historicized gender. This concerns how ACO’s female protagonist is rendered, the portrayal of other women- non-player characters in the game and representations of some queer sexualities through narrative, aesthetics and game mechanics. We argue that the gendered story ACO tells could have been significantly more complex and fair to the era it represent by drawing on the ways that gender has been done in history. Now, ACO obscures the historical power that women inhabited in favour of a contemporary and idealised view of gender.

Background

Classical Greece, Women and Scholarly Reconstructions

Antiquity, loosely understood here as ancient Greece and Rome, occupies a central position in contemporary culture. Time magazine asked in 2023 why we cannot get over the Roman Empire (Holland, 2023). Part of the answer is to be found in how masculinity, power and military process are all attractive components of an ancient past that anglophone countries have been studying and reproducing for centuries. Antiquity is similarly reproduced in video games (see Rollinger, 2020) for both educational and academic purposes. Classical scholarship often studies these games as vehicles of classical reception, or the “two-way relationship between the source text or culture and the new work and receiving culture” (Hardwick, 2003, p. 4).

ACO is set in ancient Greece during the Classical period, commonly defined as the period between the Persian wars (early 5th C. BC) and the death of Alexander the Great (323 BC). In contemporary popular awareness, this period is usually associated with canonical cultural achievements and conflicts, such as the advent of the polis, democracy, the Peloponnesian War and more. Typically, literary sources from ancient Greek society were written by elite men and therefore correspond to their perspectives, something which complicates contemporary understanding of underrepresented groups. Textual sources reflect and reproduce the concerns, anxieties and ideologies of privileged strata. Most of these authors were active in Athens, providing an Athenocentric representation of the Greek world (Porter, 2009), and it remains debatable to what extent that polis is representative of other city-states. Despite its fame, contemporary understandings of Sparta, the city-state, have often been likened to a mirage, a term coined by François Ollier in 1933 but is still in use in scholarly work today (1943).

The validation of a Panhellenic, and especially Classical, culture as “the cradle to Western civilisation” has increasingly been criticised by scholars as Western-centric and falsely exceptionalist (Porter, 2009). Inequalities marked the classical culture; political rights were enjoyed only by male citizens, not slaves, non-citizens or women. Vast differences can, however, be seen across the civilisation. For example, Spartan women appear relatively independent in Sparta’s militaristic society, where women were esteemed as mothers to soldier offspring and had responsibilities when the men were on campaign (Scott, 2017, pp. 34-40). Still, ancient Greeks seem to have variably valued citizenship, culture, athleticism and military prowess. Yet, any reading of a representation of Classical Greece, be it in video games or other media, must engage with its status as a controversial cultural symbol about which knowledge is imperfect and biased.

Greek women appear to us as fragmented and distorted (Hornblower et al., 2012; Oxford Classical Dictionary sv. Greek women, 2012). Scholars draw on and combine literary genres, literary criticism, archaeology, numismatics, demography, epigraphy and iconography when trying to reach a more comprehensive understanding of Greek women (for a turning point in this discourse, see Pomeroy, 1975). However, the resulting picture remains fragmentary. Ancient “Greek women” were not a monolith; women’s lived experience and conditions differed between social groups, between thousands of city-states, across centuries and between social contexts. However, only male citizens enjoyed formal political rights, acted in the law court and served in the army. Women were valued as child-bearers, and their sexuality was controlled in the male interest of legitimate heirs. Gender research has elucidated women’s activities in the domestic sphere and participation in economic life, agriculture, trade and crafts (e.g., Brock, 1994). Additional research has highlighted women’s role in rituals as a context in which they wielded agency (Connelly, 2007). Female participation in these spheres contradicts the claims of ancient authors who portray norms and ideals that limit women to a secluded domestic sphere. In the same way, sexuality in ancient Greece has only rather recently been examined in light of the contemporary LGBTQ movement, with research focusing on male-to-male passion as played out in myths and Athenian politics, the sexual practises of Sparta and Crete, and the relationship between Greek athletics and sexuality (Davidson, 2009).

Present reconstructions of antiquity in popular culture are typically filtered through the lens of contemporaneity. They are informed by producers’ and scriptwriters’ understanding of Greek and Roman culture and they aim to correspond to audiences’ expectations. Stories of the classical era offer a rather overt environment for discussions on ancient and contemporary issues (Cyrino, 2013), while creative and artistic interpretations often correspond to contemporary tastes. The fragmentary evidence about ancient women’s lives offers both scholarly and pop-cultural freedom when creating interpretations and popular representations of ancient women, which should be kept in mind while analysing ACO.

Doing Gender in Video Games

We start from an understanding of games as ergodic systems (Aarseth, 1997), or texts that require effort from the player to traverse, and where meaning is produced as players interact with the game. There are various ways of subdividing the facets of a game that players interact with, one of the most common distinctions being between a game’s mechanics, dynamics and aesthetics constituting Hunicke et al.’s “MDA” framework (2004). In it: Mechanics are game components, Dynamics are the behaviour of mechanics acting on input and output, and Aesthetics are the emotional responses of players. Another model is Schell’s distinctions between “mechanics,” “narrative,” “story,” “technology” and “aesthetics” (Schell, 2019). Technology in Schell’s framework refers to the material the game is made out of, aesthetics the appearance of the game, story the sequence of events that unfolds and mechanics the procedures and rules -- or what players can and cannot do that guide how the game reacts to player action. For our study, we draw inspiration from such frameworks when studying the ergodic experience of playing ACO. We focus on available in-game actions players can take toward women in the gameworld, looking at how female characters react on different layers of the game (their mechanics, aesthetics, etc.). We consider visual representations in such responses, as well as how story context motivates such actions and reactions. All the while, we consider how contemporary values and expectations of gender and sexuality shape how players experience the game. Players are always located within a cultural frame and make sense of play as it emerges through the ergodic experience. Players thus make choices and put in effort to play.

Complementing our ergodic perspective, we draw on Judith Butler’s view of performative gender (1990): the view that gender is not an essence of identity or the body, but is created when acted out. Gender is not, it becomes in a series of repeated and stylised acts. Butler sees something radical and productive in resisting gender norms by doing gender “wrong,” which is to say when individuals challenge notions of femininity and masculinity through diverse bodily acts. The dominant view of a gender binary necessitates distinguishing between genders through difference -- being one is only recognizable to the extent that it is not the other -- making heterosexuality the grounding factor for the binary division of gender (Butler, 1990). The foundational notion of “player choice” in video games has opened a space for the design of queer and feminist experiences in an otherwise often traditional cultural sector. That players should be allowed to choose for themselves is an important cultural norm for understanding how games and gameplay experiences come to be. For example, player-avatar customization: players choosing a player-character’s visual representation, gender, abilities and even sexuality allows for gender exploration and queer practices through what Butler might call doing wrong (Eklund, 2013). Thus, gender can be understood as performed through repeated game acts; drawing on cultural resources both within and outside of the game.

From this perspective, women in ACO come to be via the game’s mechanics or rules, its narrative and aesthetics, as well as the situated player’s interpretation of these during play. In arguing this, we build on contemporary notions of how to study representation in game studies. For example, in the introduction to Malkowski and Russworm’s anthology on gaming representation (2017), the editors argue that representation is connected to both the computational and representational. Chang (2017) further makes a distinction between “flat” versus “informed” representation. Flat representation is only visual, whereas representation that is informed and deepened by mechanics becomes more worthwhile. Building on these previous works we argue that what ancient Greek women are in the game is not only determined by what they say or how they are described, but also by what they can do in the game world, what actions are possible and not and how the game responds to the action of female game characters. In this sense, both flat and informed representations of women are seen here in a twofold way, incorporating the ancient context of the game and contemporary understandings of it. As Butler states, gender is about performing acts and the association of these acts to certain bodies (1990). As players traverse the game world through non-trivial effort, play is created in interactions. Thus, the game medium differs significantly from other mediums of so-called “classical reception” precisely because it is interactive and based upon the gamer’s interaction and individual choices. It is therefore not a static representation, but made by players, the game’s script and technology -- and also with an understanding of the past and how gender was constructed then.

Research on gender representation in Assassin's Creed

For at least three decades, scholars have discussed how women are stereotypically represented in games and the male gaze upon female characters represented as rewards or tropes (Cassell & Jenkins, 1998; Kafai et al., 2008). Research has shown how contemporary ideas about women as passive and men as active tend to shape game characters, and these gendered structures intersect with other identity categories in complex ways (Kafai et al., 2016). However, the early hypersexualisation of female protagonists started to decrease in the 2000s, and more and more player characters became female. Scholars have argued that behind this was the entry of identity politics and critical theory into game culture and game making which spread from mainstream society. This, in combination with the rise of the indie game industry with new game makers and types of games further diversified the medium (Bruin‐Molé, 2020). For example, one side-effect of the 2016 #Gamergate movement addressing the harassment of women in games was that it made the presence of female gamers obvious.

The Assassin’s Creed series has seen scrutiny when it comes to its representation of main characters. Soraya Murray was the first, to our knowledge, to study gender in the AC franchise in 2017. Murray studied the main-character Aveline in the side-game Liberation (2012), exploring how the game engages with orientalism and gender. Murray sees both problems and opportunities within the game, which is mirrored by Steenbakker (2021) that further studies the representation of gender and race in the same game.

One well-researched AC game is Assassin's Creed Origins (2017), which features a female playable side-character, Aya. A 2019 study explored the representation of Aya and the historical figure Cleopatra, who also features in the game. In particular, it concluded that Aya’s agency was more contemporary than historical (Texeira-Bastos et al., 2019). In another study, Jane Draycott argues that Cleopatra is exoticized as Egyptian while Aya is more positively portrayed (2022). Marcie Gwen Persyn (2022) looks at the broader demographic division of gender in Origins (and similar games) and shows the strong over-representation of men as enemies, NPCs and characters.

ACO has received its share of research. Tuplin (2022) studies the representation of sacral sex-workers heterae in the game, concluding that (though trope-laden) such representations are increasingly complex and positive. Cole (2022) examines how ACO frames Kassandra as the protagonist within the promotional material leading up to the game’s release -- particularly her voice. Cole explains that Kassandra is depicted as “empowering […] but this empowerment appears to come not from her character, but from the way in which she embodies the masculine” (p. 195). Ultimately, Cole holds that the game’s emancipatory potential is undercut by Kassandra’s enforced “slide from mercenary to mother and housewife” (p. 204) which occurs in the game’s optional downloadable content.

Despite the number of studies on the topic, several gaps are visible in research concerning gender in Assassin's Creed. Most of the above studies tend to focus on gender portrayal and historical context but tend to neglect gameplay and the interplay between these. Lara Croft is a good example of the difference between fictional entities and virtual entities that have a real-world significance that moves beyond the virtual world, what can be called ontological reproductions (Brey, 2003, p. 277). In other words, a character’s sex is fictionally depicted in a video game as it relies on fictional signifiers, where players authentically produce gender in the act of play. For us, we focus on how gender is ontologically reproduced in a historical video game context.

Method

This work is an interdisciplinary collaboration between game studies scholars and ancient history scholars. The method is based on close playing, a qualitative method similar to close readings in literature studies (Bizzocchi & Tanenbaum, 2011). This means that the first author, an experienced video game player and game studies scholar, played the standard game on a PC in 2020 and 2021. As the close playing methodology implies, we choose a starting point for the researcher/player playing the game as the female main character Kassandra, engaging in the game in the same spirit described by Chess’ 2020 book Playing Like a Feminist. The researcher-player kept a journal over the play together with screenshots and written reflections on events which happened in the game. These journal notes and screenshots were then compiled into analytical categories created in a mixed deductive and inductive approach through discussions between all authors, which implied an analytical framework developed from Aarseth’s (1997) concept of games as ergodic, discussed above. This was operationalised as game mechanics (e.g., the map, the quest system, travelling), narrative (e.g. romance storylines, narrative presentation of the main character), visual representations/aesthetics, and the interaction of these levels of information (e.g. the action opportunities in the game structure of a female main character). These categories were discussed between all authors, reviewed and defined in light of previous research. Consequently, we developed the four analytical categories presented below.

Results

Playing with History: The Ancient World as a Playground

Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed series uses the motto “history is our playground,” and the games explore different locations and periods. In ACO, players have access to a range of activities: fighting (melee, ranged, etc.); exploration and movement (walking, riding, sailing, stealth, “parkour”, etc.); interaction (talk, recruit, romance, etc.).

Players can choose between Kassandra and her brother Alexios. Kassandra is presented by the game developer Ubisoft in official communication as the canonical main character. The characters have no significant differences and the game plays out the same, irrespective of who you play. Kassandra is however almost completely absent from the game’s marketing materials. In response to this, Ubisoft responded to the magazine PCGamesN:

As metadata had to be sent some time before the official reveal, some retail pages will not showcase the full selection of assets. Store pages will, however, be updated throughout the course of the campaign to include new assets that reflect both our leading characters, as featured at the announce of Assassin’s Creed Odyssey across all our asset packs. (Jones)

While the answer claims that there were no (explicit) ideological reasons behind this choice, to this day Kassandra takes second place to Alexios in marketing and on online retail pages.

Kassandra is a Spartan who grows up separated from her family on the island of Cephalonia, which lies in proximity to Homeric Ithaca. The story revolves around her meeting members of her family while fighting a secret order, which is trying to continue exacerbating the Peloponnesian war between Athens and Sparta to further its nefarious interests. The title, Odyssey, references the epic poem by Homer, and indeed, the game make repeated nods to the travelling Greek hero Odysseus. The game thus mixes Greek stories and characters with actual historical events and figures. As the loading screen states, it is a work of fiction, inspired by historical events and characters.

Figure 1. Screenshot by authors of loading screen with aspects of the Athenian Golden Age. Click image to enlarge.

The player can move freely around the entire vast Hellenic area. Travel is often done with the player’s ship, the Ἀδρήστεια, Adrestia, meaning inescapable (“our home,” the game calls it). Within the Greek setting, the player can go anywhere, do almost anything and talk to anyone. Players explore a rendition of ancient Greece, playing with and exploring the historical era and its locations. The game mechanics reinforce this: after the player has visited somewhere, they can instantly travel there again, without the hassle of having to walk, run or ride the entire distance. The world, initially immense, soon grows smaller: the map, a standard game mechanic, at first encased in a fog of war, slowly offers up details as we travel around, making the world smaller, easier to manage. The history mode available in the game, where the player simply walks around and experiences the historical locations, further enforces that the player is a spectator, not belonging to history but playing with it.

Figure 2. Screenshot by authors of the Adrestia at sea.

ACO draws on several roleplaying game mechanics such as player character levels, skill trees and (minor) alternative paths in the narrative. Roleplaying games are often characterized by player choices. ACO is scripted; some options do exist, and others do not, i.e. a player cannot simply walk away or stop the killing and keep being a player. ACO presents us with predefined options to choose between, allowing players to exercise choice. For example, players can choose between killing Kassandra’s father or sparing his life -- a binary, fixed choice which nonetheless takes player effort and engagement, as players must win a skirmish between Athens and Sparta to be able to reach Kassandra’s father in the first place. The choice has little impact; it does not change the game in any fundamental way. Choices in ACO tend to be superficial, which affects the opportunities for gender and sexuality representations.

Playing Kassandra: Historical Gender as only Skin-deep

Kassandra, also called the Eagle bearer, is (within ACO) the granddaughter of the Spartan king Leonidas I (540-480 BC). To some extent, playing her simulates playing a Greek mythical hero. In a conversation with her travel companion Barnabas, she complains about being like Theseus, the mythical hero who slayed the minotaur and united Attica under Athenian rule, having to carry: “All that responsibility.” The narrative context around Kassandra advances our understanding of gender in the ancient world by providing terminology that is strictly masculine or used to describe men in Greek. She is described as a μίσθιος, or misthios, in the game, which is implied to be a mercenary. This position allows her to move around the world unhindered choosing her missions day-to-day, as she is not affiliated with either Sparta or Athens and is therefore able to cross contested battle lines. Misthios is the male version of the word; for a woman, the feminine ending should be μίσθια, or misthia. A normative masculine spelling is the standard in the English language game, itself a notable fact.

Figure 3. Screenshot by authors of Kassandra in Athens, Parthenon in the background.

Turning to the gameplay, the game’s mechanics center normative masculine values, such as violence and physical prowess, which the game mechanics ascribed to Kassandra’s female playing body. When interacting with male NPCs in cut-scences players can see the contemporary backslap interaction as a marker for male intimacy and friendship. This is both queered by Kassandra being the one performing it and at the same time reinforces a sense that the intended player is, indeed, a man. This results in two somewhat contractionary experiences: on the one hand a sense of liberating the close connection between masculine behaviours with masculine bodies, on the other, the creeping feeling that the female character being played is pandering to an enraged fanbase, many of whom may very well still remembers Ubisoft’s designers claiming women are too hard to design.

In the game, Kassandra is Spartan. Historical Spartan culture emphasized a visual aesthetic of physical fitness for both men and women. According to legend, the Spartan king Lycurgus decided that women and men should train equally, for women so that they might give birth to strong and fit offspring to continue guarding the integrity of the city (Plutarch ca. 46-112 AD). Fifth-century Athenian-based authors reveal a fascination with Spartan women, who are seen as independent, promiscuous, as well as economically and politically powerful (Millender, 2017). Indeed, Kassandra is strong and powerful both physically and mentally, and in this sense, she embodies what contemporary historians now think of as Spartan beauty standards (Christesen, 2012).

In ACO, Kassandra’s Spartan heritage is used to explain her battle prowess, and the game contains flashbacks to Kassandra training with the spear at a very young age. Spartan identity allows Kassandra to be a powerful, fighting woman from this period. Thus, the game draws on contemporary and historical ideas of gender to make Kassandra somewhat believable within the game and its historical settings. At the same time, the distinct masculine behaviour and action space that Kassandra enjoys is inspired by and modelled on Greek hero mythology. Kassandra is female in appearance, adhering to Spartan beauty ideals, and yet she is masculine in actions and interactions with in-game characters. She leads soldiers, captains a ship and takes part in the Olympics; all actions and opportunities that were historically limited to men. As Cole (2022) has argued, her power comes not from herself, but from her embodiment of masculinity. We further argue that in ACO, the historical representation of Kassandra’s female gender positions is only skin deep. The playability, context, narrative and even historical terminology describing the character, are, in terms of historical research, essentially male. Kassandra operates within a historical male context and her role is conventionally historically assimilated to a maleness.

Playing with Aspasia: Female Non-playable characters

In ACO, Athens is a vast, sprawling city, markedly larger than any other city in the game. It is filled with NPCs of famous historical persons such as the central figures in Athenian philosophy like Aristotle. The story takes the player to the leading Athenian statesman Pericles’ (495-429 BC) symposium, hosted by his partner Aspasia (ca.470-ca.400 BC). She is represented by a young and beautiful character model, with her head and arms bare. She makes sure that Pericles interacts with his guests, and serves as a supporting character who helps and supports the player through the game’s story. She is something of a spider in a web, knowing what is going on, pulling strings and making things happen.

Figure 4. Screenshot by authors of Kassandra interacting with Aspasia on board the Adrestia.

Historically, women lacked official political power in Athens, and they could not hold property, which had to be passed to a male heir. Women were thus constantly under the control of their husbands or fathers (McClure, 2019). In the game, Pericles enjoys open political power, while Aspasia has an informal, more hidden form of power. However, as the game progresses, the power that Aspasia has carved out as a woman is turned on its head. The player eventually discovers that she is the disposed, and perhaps repentant, leader of the fictional evil cult that Kassandra is hunting; a cult that started the war and kidnapped Kassandra’s young brother.

What could have been a comment on the way historical women found agency (even in restrictive patriarchal structures) instead becomes a common trope of women as intriguers, and a powerful comment on how the types of power women wielded historically were often not as virtuous as those of men. Pericles is portrayed as a tired and righteous hero and Aspasia a manipulative schemer. In this sense, the NPC Aspasia conforms to some stereotypes that see women characters as vital, yet in the gameplay, her presence is not authentic; she is often sexualised and follows common tropes. Aspasia’s historical significance pales in comparison to her male counterparts -- an equally common paradigm within the study of classics.

Playing with gender in the daughters of Lalaia questline

Figure 5. Banner for the questline The Daughters of Lalaia, image from Ubisoft official X profile (Assassin's Creed, 2019).

As detailed above, doing gender as Kassandra is mostly skin deep and, for many named non-playable characters, any historical commentary on gender roles is lost in the story. However, the Daughters of Lalaia series of side quests offers a new way of playing with gender. When the player arrives in the town of Lalaia all the local men are away at war. The few hunters who stayed have recently been killed by a rogue group known as the Sons of Xerxes, Persians left behind after a previous war. The Sons are looking to take over the village and, in a series of quests, the player can assist in preparing Lalaia for the impending battle. Several of these quests make gender a key feature.

Periktione is the acting leader of the town. She is married to the magistrate, who has left for war. An ongoing conflict for power takes place between her and her unmarried sister who believes herself better able to lead. The player must make several choices in which they can side with either sister in the quest to defend the town. In the quests, gender comes to the fore. One example is how the player is tasked with boosting the self-confidence of the blacksmith’s daughter. She refuses to make any weapons or armour for the village due to a lack of confidence, even though she has assisted her father with blacksmithing since she was a child. There is plenty of evidence today about how internalised gender expectations can teach women to doubt their abilities and even perform worse due to this (e.g. Steele et al., 2002). A parallel could be made here regarding how women are often discouraged from participating in the masculine-coded field of gaming.

The Lalaia questline exemplifies how women defend themselves as a group against men as a group, thus locating gender not only in individual behaviour but in societal structures. Through the conflict between older, married Periktione and her younger sister, the game lifts historical gendered structures such as marital status to be concretely played with. The example of the blacksmith's daughter, further allows players to examine internalised sexism. ACO mostly does not deal with gender -- historical or contemporary -- in any depth, yet the Lalaia questline shows that the game is capable of it, as it lets the player explore gender in more complex and nuanced ways.

Playing with Historical Sex and Sexuality

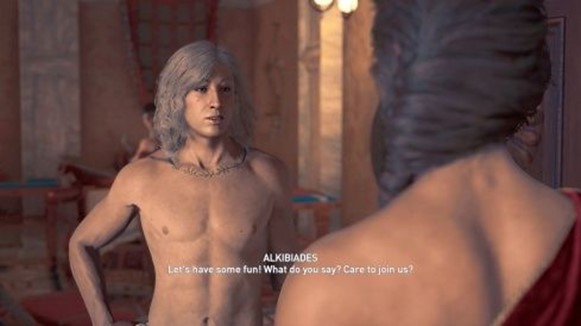

Over the last decade, sexuality and gender have become more rooted as key subjects in the study of video games (Shaw and Ruberg, 2017). Queer games and queer game scholarship suggest that queerness has emerged as a focal point in the push to diversify games and society (Sundén and Sveningsson, 2012; Ruberg and Shaw, 2017; Evans, 2018; Ruberg, 2019). Like many games that claim to center player choice, love and sex are playable experiences in ACO -- a first for the Assassin’s Creed franchise. As the player traverses the game world as either Kassandra or her brother Alexios, many NPCs can be temporary sexual and romantic partners depending on player choice. The first romance options are all female characters.

Once the player reaches Athens, they are introduced to a central NPC and historical character Alcibiades (450-404 BC). Historian P. J. Rhodes’ (2011) recently wrote a bibliography about Alcibiades, with a title befitting his ancient reputation and modern reception: Alcibiades: Athenian Playboy, General and Traitor. Handsome, rich and well-educated yet profoundly opportunistic, volatile and unreliable, this Athenian aristocrat, politician and commander was arguably the bad boy of his time. Alcibiades -- obviously an interesting character for the game -- is encountered in the orgy room at Pericles’ symposium (a historical accuracy), which the player can visit as either Kassandra or Alexios. In general, sex in the game is disconnected from the player’s choice of gender, which represents perhaps a more accurate depiction of antiquity. James Davidson in The Greeks and Greek Love suggests that there was no concept of hetero- or homosexuality during the Classical period (2009). Yet, Davidson also illustrates the clear power hierarchies of the era, in which male Athenian citizens had more sexual freedom than women and clear norms existed on who could have sex with whom, and who penetrated/satisfied whom.

Figure 6. Screenshot by authors of Alcibiades inviting the player to the orgy room at Pericles’s symposium.

The further the player progresses in the game, the more romance options open. Non-heterosexual relationships are plentiful and given the same status as heterosexual ones; the game makes no distinction. In the game, characters are not bound by modern definitions of sexuality and it is very much up to the player to make decisions whether to act on sexual opportunities or not. For example, once the player finds and meets the player-character’s mother, Myrrine, they learn that she has a female lover, whereas she had previously been happily partnered with the player-character’s father.

Sexuality in the game, by not being defined or put into binary identities, mirrors the era that the game is representing. The game revolves around player choice, yet the options available to players happen to align well with interpretations of the historical era being represented. However, the power hierarchies and regulations of the historical era in question of sexuality are absent in the game, leaving the player with a more modern, but limited view of ancient sexuality. A view where how sex acts where limited depending on a person's gender is not acknowledged. ACO ended up in the public spotlight when a game expansion, Assassin’s Creed Odyssey: Legacy of the First Blade (Ubisoft, 2018), forced the player-character into a heterosexual relationship resulting in the birth of the player-character’s child. In the Assassin's Creed world, players follow bloodlines back in history, implying that the series' main characters have children. However, this has often taken place outside of the games. In the expansion, the player’s freedom to define and choose their sexuality was taken away, to the dismay of many players. The company later issued an apology to players, specifically about taking away this freedom (Loveridge, 2019).

Discussion

We have analysed how gender is rendered in the ancient world of ACO, and what it means for historical gender exploration and the representation of gender in video games. Playing ACO, players are constantly empowered, making choices, levelling up, gaining more power and obtaining stronger weapons and armour. Kassandra gains followers as the game progresses, and she can draw on their strength in battle, together with ever-better gear and skills. The increase of these various resources increases steadily over the course of the game, not linked to the era, but more representative of a “hero’s journey.” In contrast to the playable character Aya in AC Origins whose agency is more in line with contemporary female positions (Texeira-Bastos et al., 2019), Kassandra’s is mythical. She is a unique character to the game yet constructed like a hero, taking traits from mythical figures. Many of the game skills borrow their names from other mythical figures such as the Greek gods -- for example, “Ghost Arrows of Artemis.” The historical era is often subordinated to mechanics, something many developers argue is frequently the case in large productions (see Linderoth, 2015). The ergodic experience of ACO concerns traversing the ancient world and playing in it, using it as a setting for player empowerment and displays of game mastery. A player can do anything while risking very little. This core game mechanic works well with idealistic ideas of Western hegemonic masculinity, and less so with the roles of opportunity for women in the historical period of ACO. Female power and agency in ancient Greece, as far as we understand it today, was carved out within social structures that by legal and social means limited formal power. Kassandra represents a stereotypical video game hero, a power fantasy, and as such she becomes distinctly masculine. Kassandra represents what has been called the gender-agnostic approach to designing game characters, where only the skin of the character signifies gender and the game will be the same no matter which gender players choose (Back & Waern, 2013). However, what is under Kassandra’s skin is distinctly male. This can of course be empowering and liberating for players, given the disconnection between female bodies, subordination and sexual oppression. Yet the default often becomes a masculine-coded character (Ibid.). In the present case, it reinforces a long-standing historical pattern wherein historical female gender positions have been defined as powerless by men in power (Beard, 2017).

Women in this historical context did have power, however far from equal power to male citizens, yet they did exercise power in certain sectors and spheres of society; for example as priestesses and in religious rituals, in the economy through trade and crafts or as de facto decision-makers. This meant that women wielded power and influence by subverting, manipulating, or ignoring expectations and social structures. The character of Aspasia, which could have been an opportunity for a relevant and interesting take on the roles women have played in history, is instead demonised and corrupted, with her power shown to have been unjustly gained. The priestesses of Artemis, a religious order with which the player can ally, do not wield any power as priestesses in society, but instead exist as female brigands in the woods, living separate from the game world of ancient Greece. Thus, the game squashes yet another way women carved out power niches in this era. In the words of Chang (2017), contemporary audiences see flat rather than informed representations of these historical women.

Player choices have a significant effect on how women are made in the game, leveraging visual design, narrative and action. Importantly, ACO does not force choices that go contrary to contemporary norms and values. Research has shown that people often act in games in ways that mirror their ethical frameworks (Consalvo et al., 2019). Only on perhaps a second or third playthrough do most feel comfortable playing with divergent moral or ethical choices. In a game that takes around 100 hours to complete, more than one playthrough is not realistic for most players. ACO is not trying to make modern gamers perform gender as it would have been performed in the Classical period. Gender, inasmuch as it is an iterative performance constituted by repeated acts (Butler, 1990) in the game, is chiefly made according to a 21st-century masculine ideal, in which women, like men, are free agents (and citizens) who can come and go as they choose.

Kassandra travels all over the ancient world, sleeping with men and/or women as the player fancies. The openness of the role-playing game lends itself well to fluid sexuality choices, choices that align with certain aspects, but not others, of how sexuality operated in antiquity. The ergodic experience becomes less fractious, and the integration of mechanics and narrative less conflicted. Through supporting player choice, the game offers players a way to explore aspects of sexuality from this era. However, the relationships involving sex are fleeting and temporary, clearly set outside of the main experience. Romance comes in side-quests that do not affect the player's character or the game overall.

In the side-quest Daughters of Lalaia, gender becomes a key game feature in the game’s aesthetics, narrative and gameplay. As elsewhere in history, women in Ancient Greece rose to official positions of power and authority when men were away at war. The questline makes gender visible by dealing with imbalance in power between men and women as social groups. Moreover, this line of sidequests makes the player play out this conflict as a war with lives at stake. By lifting issues of gendered expectations and confidence, the game allows players to explore the consequences such conflict might have and through play engage with gender in a personal way. The questline allows players to glimpse what a more nuanced play with historical gender could look like, as historical and contemporary gender issues become blended.

The comment from Assassin’s Creed Unity’s creative directors and level designers about how women are too hard to animate could be interpreted as the difficulty in game production to create completely different sets of animations, working with different actors for motion capture, etc. Yet, previous Assassin's Creed games have solved this by letting female characters reuse animations made for male bodies, with only very few specific animations made (Eklund and Zanescu, 2024). The result in ACO is that players can choose to play as a woman or a man, yet the choice is a choice without effect, a choice only of visual representation. The consequence is a Kassandra, who combines a male Athenian power position with a “Spartan” visual aesthetic.

A more generous interpretation could be of ACO as alternative history, a genre which has lately started to gain traction. In an era where people are broadly aware that all historical representations are only partial, informed by dominant and grand narratives and never complete, the act of picking and choosing some historical elements becomes a way of empowerment. Netflix’s recent TV success Bridgerton (Van Dusen, 2020), creates an Edwardian England where skin colour is not a structuring social factor -- where the queen or a duke is as likely to be black as white. Removing historical gender inequalities in ACO can be seen as liberating and corresponding to contemporary ideals of equality and diversity. However, ACO has always portrayed itself as being accurate to the historical milieus it portrays, while Bridgerton is clear in where it diverges from the ways people tend to view history, making it a point of the series. Selective representation of history is to be expected, yet when dated elements are overlooked, it says more about our contemporary lifeworld than about history (Lowenthal, 2015). A more interesting story of historical gender could draw on and allow contemporary players to explore other facets of gender, not only the nice and unproblematic. One way would be by scripting alternative forms of agency, as seen in our examples above.

Conclusion

Gaming as a sexual and power fantasy has significant consequences on how women can be portrayed in video games. In ACO, historical representations are affected by contemporary norms about gender and sexuality. Historial games like ACO represents a negotiation between historical knowledge and contemporary values and ideals, by giving players the opportunity to play with history. In ACO, players act out a masculine hero’s journey of increased empowerment, despite the game’s narrative revolving around a female character in a historical era where women were, socially and legally, under the control of men. The resulting ergodic experience of playing a woman is one of cognitive dissonance that in some ways undermines the feelings of empowerment. Kassandra is a woman only on the outside. While this could allow for queer play and disconnection of masculine behaviour from masculine bodies, it precludes exploration of women’s positions through history and the specific character of the power and agency that women did have in antiquity. In turn, this reduces the potential for comparison, critique, nuanced game experiences and ultimately knowledge.

The gendered story of ACO obscures and erases the historical power that women inhabited in favour of contemporary and idealised views on gender. By not drawing on the multitude of complex ways that people in history navigated gender in and against social structures opportunities for exploration and understanding are lost. ACO’s approach to gender and premiering of a certain type of player choice based on contemporary gender norms forecloses other ways of imagining and exploring historical gender.

References

Aarseth, E.J. (1997). Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Assassin’s Creed [@assassinscreed]. (2019, January 8). The Daughters of Lalaia is now available in #AssassinsCreedOdyssey and is free for all players! In this new Lost Tales. [Image attached] [Post]. X. https://x.com/assassinscreed/status/1082649633871020041?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm% 5E1082649633871020041%7Ctwgr%5E95da82449649c01a6e1d3 bd4673c1fbc4502e814%7Ctwcon%5Es1_&ref_url=https%3A%2 F%2Fwww.gamewatcher.com%2Fnews%2Fassassins-creed-odyssey-daughters-of-lalaia

Back, J., & Waern, A. (2013). “'We are Two Strong Women' -- Designing Empowerment in a Pervasive Game.” Proceedings of DiGRA 2013: DeFragging Game Studies, 126-135.

Beard, M. (2017). Women & Power: A Manifesto (Illustrated edition). Liveright.

Bizzocchi, J., & Tanenbaum, T. (2011). “Well read: Applying close reading techniques to gameplay experiences.” In D. Davidson (ed.), Well Played 3.0: Video Games, Value and Meaning 3 (pp. 289-315). ETC Press.

Brock, R. (1994). The Labour of Women in Classical Athens. The Classical Quarterly, 44(2), 336-346.

Brown, F. (2018 June 22). Kassandra is Assassin's Creed Odyssey's main hero, but only in the book. Rock, Paper, Shotgun. https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/assassins-creed-odyssey-main-character

Bruin‐Molé, M. (2020). “Women Heroes in Video Games.” In K. Ross, I. Bachmann, V. Cardo, S. Moorti, & M. Scarcelli (Eds.), The International Encyclopedia of Gender, Media, and Communication (pp. 1-5). John Wiley & Sons.

Butler, J. (1990). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (1st edition). Routledge.

Cassell, J., & Jenkins, H. (Eds.). (1998). From Barbie® to Mortal Kombat: Gender and Computer Games. MIT Press.

Chang, E.Y. (2017). Queergaming. In Ruberg and Shaw (Eds.) Queer game studies, pp. 15-24. University of Minnesota Press.

Chapman, A., Foka, A., & Westin, J. (2017). Introduction: What is historical game studies? Rethinking History, 21(3), 358-371.

Chess S. (2020). Play like a Feminist. MIT Press.

Christesen, P. (2012). “Athletics and Social Order in Sparta in the Classical Period.” Classical Antiquity, 31(2),193-255.

Cole, R. (2022). “Kassandra’s Odyssey.” In J. Draycott & K. Cook (Eds.), Women in Classical Video Games (pp. 191-207). Bloomsbury.

Connelly, J.B. (2007). Portrait of a priestess: Women and ritual in ancient Greece. Princeton University Press.

Consalvo, M., Busch, T., and Jong, C. (2019). 2Playing a Better Me: How Players Rehearse Their Ethos via Moral Choices.” Games and Culture, 14(3), 216-235.

Cyrino, M.S. (2013). “Ancient sexuality on screen.” In Hubbard, Thomas K., (ed.) A Companion to Greek and Roman Sexualities pages 613-628. John Wiley & Sons.

Davidson, J. (2009). The Greeks and Greek Love: A Bold New Exploration of the Ancient World. Random House.

Draycott, J. (2022) “Playing Cleopatra in Assassin’s Creed Origins.” In J. Draycott & K. Cook (Eds.), Women in Classical Video Games (pp. 162-174). Bloomsbury.

Eklund, L. (2013). Doing gender in cyberspace: The performance of gender by female World of Warcraft players. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 17(3), 323-342.

Eklund, L., & Zanescu, A. (2024). Times They Are A-Changin’? Evolving Representations of Women in the Assassin’s Creed Franchise. Games and Culture, online first.

Evans, S. (2018). Queer(ing) Game Studies: Reviewing Research on Digital Play and Non-normativity. I T. Harper, M. B. Adams, & N. Taylor (Red.), Queerness in Play (s. 17-33). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90542-6_2

Farokhmanesh, M. (2014 June 10). Ubisoft Abandoned Women Assassins in Co-op Because of the Additional Work. Polygon. https://www.polygon.com/e3-2014/2014/6/10/5798592/assassins-creed-unity-female-assassins

Jones A. (2018, June 28). Here’s why Kassandra barely features on the Assassin's Creed Odyssey store pages. PCGamesN. https://www.pcgamesn.com/assassins-creed-odyssey/assassins-creed-odyssey-kassandra-alexios

Hardwick, L. (2003). Reception Studies: Greece and Rome: New Surveys in the Classics. Cambridge University Press.

Holland, T (2023, September 21) Why We Can’t Get Over the Roman Empire. Time. https://time.com/6316386/tom-holland-roman-empire-obsession-essay/

Hornblower, S, Spawforth, A., & Eidinow, E. (2012). The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Fourth edition. Oxford University Press.

Hunicke, R., LeBlanc, M., & Zubek, R. (2004). “MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research.” Proceedings of the AAAI Workshop on Challenges in Game AI, 4, 1722-1727.

Kafai, Y. B., Heeter, C., Denner, J., & Sun, J.Y. (2008). Beyond Barbie[R] and Mortal Kombat: New Perspectives on Gender and Gaming. MIT Press.

Kafai, Y. B., Richard, G. T., & Tynes, B. M. (2016). Diversifying Barbie and Mortal Kombat: Intersectional Perspectives and Inclusive Designs in Gaming. ETC-Press

Loveridge, S. (2019 January 17). Ubisoft Responds (again) About the Forced Assassin’s Creed Odyssey DLC Romance. Gamesradar. https://www.gamesradar.com/assassins-creed-odysseys-dlc-forces-you-to-fall-in-love-and-fans-arent-happy/

Lowenthal, D. (2015). The Past Is a Foreign Country -- Revisited (2nd Revised edition edition). Cambridge University Press.

Malkowski J. & Russworm, T. M. (2017). Gaming Representation: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in Video Games. Indiana University Press.

McClure, L. (2019). Women in Classical Antiquity: From birth to death. Wiley.

Murray, S. (2017). The poetics of form and the politics of identity in Assassin’s Creed III: Liberation. Kinephanos: Journal of Media Studies and Popular Culture, July Special Issue, 77-102.

Ollier, F. (1943) Les Belles Lettres, Le mirage spartiate : étude sur l'idéalisation de Sparte dans l'antiquité grecque. Boccard. Original work published in 1933

Persyn, M. G. (2022). “Dangerous Defaults: Demographics and Identities Within and Without Video Games.” In J. Draycott & K. Cook (Eds.), Women in Classical Video Games (pp. 44-58). Bloomsbury Publishing.

Plutarch (1914). Lives, Volume I: Theseus and Romulus. Lycurgus and Numa. Solon and Publicola.). (P. Bernadotte, Trans.). Loeb Classical Library 46 . (Orighinal work published ca. 46-112 A.D.)

Pomeroy, S. (1975). Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity. The Bodley Head Ltd.

Porter, J. I. (2009). “Hellenism and Modernity.” In B. Graziosi (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Hellenic Studies (pp. 7-18). Oxford Academic.

Rhodes, P. J. (2011). Alcibiades: Athenian Playboy, General and Traitor. Pen and Sword Military Books.

Ruberg, B., & Shaw, A. (2017). Queer Game Studies. U of Minnesota Press.

Ruberg, B. (2019). Video Games Have Always Been Queer. NYU Press.

Schaps, D. (2010). Handbook for Classical Research. Routledge.

Schell, J. (2019). The Art of Game Design: A book of lenses (3rd ed.). CRC Press.

Scott, A.G. (2017). Spartan Courage and the Social Function of Plutarch’s Laconian Apophthegms. Museum Helveticum, 74(1), 34-53.

Shaw, A., & Ruberg, B. (2017). Introduction: Imagining Queer Game Studies. In A. Shaw & B. Ruberg (Eds.), Queer Game Studies (pp. ix-xxxiv). University of Minnesota Press.

Steele C. M., Spencer S. J. & Aronson J. (2002). Contending with Group Image: The Psychology of Stereotype and Social Identity Threat. In M. Zanna (ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (V. 34, pp. 379-440). Academic Press.

Steenbakker, M. (2021). “A Power Shrouded in Petticoats and Lace: The Representation of Gender Roles in Assassin’s Creed III: Liberation.” New Horizons in English Studies, 6(1), 92-110.

Sundén, J., & Sveningsson, M. (2012). Gender and Sexuality in Online Game Cultures: Passionate Play. Routledge.

Taylor, T.L. (2009). “The Assemblage of Play.” Games and Culture, 4(4), 331-339.

Texeira-Bastos M., Carneiro L.C.& Bondioli N. (2019). “History, design and archaeology: the reception of Julius Caesar and the representation of gender and agency in Assassin’s Creed Origins.” In die Skriflig, 53(2).

Tuplin, R. (2022). “We do what we must to survive”: female sex workers in Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey. In J. Draycott & K. Cook (Eds.), Women in Classical Video Games (pp. 208-222). Bloomsbury Publishing.

Ubisoft Sofia. (2012). Assassin’s Creed Liberation [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Julian Gollop, published by Ubisoft.

Ubisoft Montreal. (2014). Assassin’s Creed Unity [Microsoft Windows]. Directed by Alexandre Amancio and Marc Albinet, published by Ubisoft.

Ubisoft Montreal. (2017). Assassin’s Creed Origins [Microsoft Windows]. Directed by Jean Guesdon and Ashraf Ismail, published by Ubisoft.

Ubisoft Quebec. (2018) Assassin's Creed Odyssey: Legacy of the First Blade [Microsoft Windows]. Published by Ubisoft.

Ubisoft Quebec. (2018). Assassin’s Creeds’ Odyssey [Microsoft Windows]. Directed by Jonathan Dumont Scott Phillips, published by Ubisoft.

Van Dusen, C. (2020). Bridgerton, season 1 [TV-series]. Executive producers Shonda Rhimes, Betsy Beers, Chris Van Dusen and Julie Anne Robinson, published by Netflix.