A Concise Introduction to the Study of Analepses in Video Games: Approaches and Possibilities through The Last of Us: Part II

by Alexis F. ViegasAbstract

Since its inception in the late 1990s, researchers have explored a wide array of interdisciplinary concepts in game studies. However, analepses have received very little attention in this field, despite being a prominent feature of so many video games. In contrast, this topic has found considerable traction in literary and film studies. The present essay aims to highlight this gap while providing a brief introduction to the study of analepses in video games. Its goal is to address the few studies conducted thus far, and explore the ways they may or may not be useful in approaching games as cultural and artistic objects. Lastly, the paper proposes a potential starting point for future research by analyzing The Last of Us: Part II as a case study.

Keywords: analepsis, flashback, narrative, time paradox, The Last of Us: Part II

Introduction

Narrative, interactivity and time are a few of the most well studied topics in game studies. Despite being closely related to these subjects, and an integral part of many well-known games for decades, analepses have received relatively limited attention in the field. While psychologists have researched the relationship between video games and flashbacks extensively (Granat, 2021; Holmes, James, Coode-Bate and Deeprose, 2009), these studies explore flashbacks as psychological phenomena experienced by human beings in response to trauma and triggers, and not as narrative devices. Meanwhile, narrative analyses of analepsis can be found abundantly in literature and film scholarship. Gérard Genette’s study and definition of analepsis in his book Figures III (1972) is one of the most important in twentieth century literary theory, having influenced later critical approaches to film. It was a decisive theoretical structure for how David Bordwell framed the flashback in Narration in the Fiction Film (1985), a monograph in which he attempts to build a concise foundation for approaching film theory, specifically where narrative and narration are concerned. It similarly influenced Maureen Turim’s influential book Flashbacks in Film: Memory and History (2014), originally published in 1989. More recently, Adriana Gordejuela expanded on Turim’s earlier research through a cognitive approach to flashback theory in Flashbacks in Film: A Multimodal and Cognitive Analysis (2021), which also takes Genette’s analepsis as a foundational point.

The kind of in-depth research listed above is severely lacking in relation to video games. The present article aims to provide an overview of the few studies available on analepsis in game studies. It will explore the ways this subject has been approached and highlight how these works may or may not be useful to the study of video games as artistic and cultural objects. From there, I will address a few concerns put forth by Jesper Juul (2005) and Lluís Anyó (2015), regarding time paradoxes provoked by analepsis. Lastly, the paper proposes an approach to analepsis analysis through a critical reading of key analeptic sequences in The Last of Us: Part II (Naughty Dog, 2020). As detailed later in the article, Part II showcases a host of narrative design strategies that are particularly compelling for analyzing the topic.

The (Brief) Study of Analepsis in Game Studies

Temporal order, and temporality more generally, are not new concepts in and of themselves for game studies. Marie-Laure Ryan, for instance, has discussed these topics at length, particularly in relation to concepts such as “hypertext,” “virtual narratives,” and “virtual narration” (2002; 2001; 1995). In each of the works cited here, Ryan briefly addresses flashbacks and flashforwards, mentioning in passing how their presence could be relevant for temporality and narration in digital media. Similarly, Huaxin Wei has argued in favor of implementing flashbacks as part of a game’s “embedded narrative,” describing them as: “[S]cripted narrative elements that are embedded throughout a game to form the background story” (2010, p. 247). Byung-Chull Bae and R. Michael Young (2013) also mention flashbacks alongside foreshadowing as tools for a computational model that could be applied in games to elicit surprise in the player. This is to say that while analepses/flashbacks seem to be a well-established part of game studies’ vocabulary, there is a notable lack of in-depth discussion and problematization of the concept.

The main explorations of the topic are relegated to a few essays published in the early-to-mid-2010’s. David Mould and Gail Carmichael’s “Chronologically Nonlinear Techniques in Traditional Media and Games” (2014) provides a few short paragraphs on the role and implementation of flashbacks in games, as their aim is to deliver an overview of many non-linear narrative techniques. Olivier Guy and Ronan Champagnat’s “Flashbacks in Interactive Storytelling” (2012) offers a much more detailed account, as it aims to be “a blueprint for an outline of a stylistic grammar in IS [Interactive Storytelling], starting with the device of flashback” (2012, p. 246). The authors’ goal is ambitious and mostly accomplished, but it is not particularly useful for critically approaching games from a narrative or artistic perspective. In fairness, the goal of Guy and Champagnat’s essay is to make the flashback a more accessible device to game developers and designers working on interactive storytelling, not to establish any sort of critical framework akin to Genette’s or Turim’s: “We would like to provide what we know from other means of expression to support designers who would like to create analepsis in their systems” (Ibid.). Nonetheless, Guy and Champagnat’s research is still valuable in different ways. It compiles examples from film and literature which detail different aspects of flashback integration, as well as its various emotional and dramatic effects. They have effectively produced a “technical manual” of sorts.

The last essay I want to highlight in this section is Lluís Anyó’s “Narrative time in video games and films: From loop to travel in time” (2015). Anyó explores temporality in and of video games, and how it may influence narrative elements such as order or duration. Flashbacks are only referenced in relation to (narrative and plot) temporal order, particularly regarding the potential issue of time paradoxes. This is a concern shared by Jesper Juul (2005) in his brief mention of flashbacks, which is discussed later in this article.

These three essays each represent the most in-depth approaches to analepsis in game research. Additionally, they showcase how the topic is commonly featured in the scholarship; that is, subjugated to the wider context and purposes of other subjects. Other examples include Marissa Hoek, Mariët Theune and Jeroen Linssen’s research on the role of focalization and flashbacks in training the social skills of police officers (2014, p.13). Josiah Lebowitz and Chris Klug (2011) also offer a sort of “manual,” akin to Guy and Champagnat’s, which features a few explanatory paragraphs and practical examples of flashback implementation in film and video games. Analepses are often mentioned while exploring temporal structures (Figueiredo, 2013; Zagal and Mateas, 2010) and more technical approaches to storytelling, plot outlines and overall narrative building (Crowley, 2017; Chen, 2014).

Such studies only discuss analepsis in passing. Guy and Champagnat point to a possible reason for this gap in research, claiming that analepses/flashbacks are underexplored partially due to video games themselves rarely featuring analeptic sequences, particularly playable ones:

[W]e have not heard of any serious commercial game that would have made a serious experiment of a playable flashback. Therefore, we barely know the grammar of this stylistic interactive device, as an aesthetic device or a psychological device to an audience. (2012, p. 246)

It is true that the knowledge of analepses as “stylistic interactive device[s]” (Ibid.) is generally lacking in the scholarship. That said, I contend that the lack of games with analepsis is particularly true for interactive storytelling (which their essay focuses on), if by “interactive storytelling” the authors are referring to games where players can either alter or influence the storyline and/or its characters. They suggest as much when stating that: “Interactive storytelling is by definition not fixed […]” (Guy and Champagnat, 2012, p. 249), though since “interactive storytelling” is notoriously difficult to define [1], it is hard to argue either way. Nonetheless, I want to propose a hypothesis about why this perspective might give an incomplete overview of the implementation of playable and unplayable analepsis in video games. Firstly, it is unclear what is meant by a “serious commercial game” (Ibid., p. 246). Guy and Champagnat appear to be alluding to “Triple-A” products, which have often set the standard for the stylistic grammar of many gaming elements due to their overwhelming dominance over the gaming industry. However, both playable and unplayable analepses have been implemented across different genres of “Triple-A” videogames since the 1990s. Final Fantasy VII (Square, 1997), for instance, hosts one of the most recognizable, playable analeptic sequences in gaming: Cloud’s retelling of how he met Sephiroth. During the sequence, players witness certain events through cutscenes while playing others, either through environmental exploration or combat encounters. The narrative value of this sequence cannot be undermined either, as it presents a crucial piece of context. This is how players learn why Sephiroth became an antagonistic entity: “This important event, shown as a playable flashback through Cloud’s eyes, does an excellent job of demonstrating Sephiroth’s power and his rapid descent into madness” (Lebowitz and Klug, 2011, p. 143). Heavy Rain (Quantic Dream, 2010) is another example of a game where a playable flashback is central to the narrative -- this is how players learn the identity of the Origami Killer, a serial killer and the game’s main antagonist. This sequence has players controlling the Killer as a young child, trying to find help for his drowning brother. More recently, The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt (CD Projekt Red, 2015) [2], also features playable analepses that are filled with narrative moments, combat encounters and exploration.

Such examples aside, analepses remain mostly as unplayable, cutscene sequences. Thus, while I partially disagree with Guy and Champagnat’s argument, they are right to suggest that more often than not, “there are [almost] no specific differences between a […] flashback from a video game and one from a movie” (Guy and Champagnat, 2012, p. 247). In fact, if a flashback is merely relaying information about a character, event, or setting, there is little reason for it to appear as anything other than a cutscene -- as cutscenes are devices most commonly used to show character and plot information. Nonetheless several games, such as the examples listed above, have implemented interactive flashbacks that deserve closer attention. To begin, I would like to turn to the concerns put forth by both Juul (2005) and Anyó (2015) regarding paradoxes.

Both Juul (2005) and Anyó (2015) have argued that interactive past sequences in video games could lead to time paradoxes. Juul states:

Using cut-scenes or in-game artifacts, it is possible to describe events that led to the current fictional time, but an interactive flashback leads to the time machine problem: The player’s actions in the past may suddenly render the present impossible. This is the reason why time in games is almost always chronological. (Juul, 2005, p. 159)

Anyó raises similar concerns, providing the following example: “If, during an analepsis, the character who is the avatar of the player dies, this creates a contradiction in the present time in which they are still alive” (2015, p. 67). Time paradoxes are a legitimate issue when it comes to games that use interactive storytelling and incorporate states of failure within their (potentially) branching narrative structure. If the player’s actions in the past can significantly change the present, the continuity and coherence of the story needs to be maintained by either limiting the impact of those actions, or by introducing new story paths that align with the choices available to the player. In either case, such maintenance involves carefully planning and structuring a game’s narrative throughout development, and is not an inherent issue for flashbacks whether they be interactive or not. Adam W. Ruch’s temporal theory (2013) is a useful framework for understanding how the issue of branching and non-branching narrative paths may be addressed. If the game’s “fictional time” represents an “ideal timeline” (Ruch, 2013, p. 3), completely or conditionally independent of acts and decisions made by players during the “action time” (Ibid.), then the player-character’s death becomes inconsequential to the histoire [3] (Genette, 1972) itself -- as it tends to be in most games, regardless of whether the state of failure happens in the present or past. Furthermore, if the player is unable to overcome the challenges presented, their failure will hinder the story’s progression regardless of whether said failure occurs in the present or the past. After all, it is arguably necessary in games that challenges must be surmounted for narrative and ludic progression to take place. Aarseth (1997) corroborates this notion, stating that the relation between progression and event -- two discursive planes -- is mediated in games by a third plane: negotiation. Players must confront a game’s challenges “to achieve a desirable unfolding of events” (Aarseth, 1997, p. 125). Time passes during an analeptic sequence the same way it does in the present, insomuch as the “final, successful attempt is the only one that figures into fictional time” (Ruch, 2013, p. 3) and triggers the “unfolding of events” (Aarseth, 1997, p. 125).

Approaching Analepsis in Video Games

As early film theory showcases, Genette’s literary and narratological framework for analepsis can be a useful tool transcending any specific medium. By relying on Genette’s work, my argument aligns with the previously mentioned research in game studies that use narratological concepts, including analepsis (Crowley, 2017; Anyó, 2015; Figueiredo, 2013). Markku Eskelinen’s seminal work Cybertext Poetics: The Critical Landscape of New Media Literary Theory (2012) is another important example of applying Genette’s theories in video game scholarship, as the author explores temporality extensively, building upon Genette’s work related to tense and temporal order. This paper similarly proposes that Genette’s study of analepses is a legitimate starting point for applying the topic to video games.

In Figures III (1972), Genette delineates variations in the chronological order of narrative, of which analepsis is the focal point. The author defines analepsis as “any posterior evocation of an event prior to the point in the story where we find ourselves” [4] (Genette 1972, p. 82; my translation). Maureen Turim also offers a similar understanding of the flashback in film:

[…] [A] flashback is simply an image or a filmic segment that is understood as representing temporal occurrences anterior to those in the images that preceded it. The flashback concerns a representation of the past that intervenes within the present flow of film narrative. (2014, p. 2)

Regarding video games, Mould and Carmichael’s position aligns with the previous definitions: “A flashback occurs when the advancement of a story pauses to portray a relevant event that happened in the past relative to the character’s linear story” (2014, p. 3). Genette further defines analepsis as internal, exterior and/or mixed temporality [5]. Regarding mixed analepses, film theorist Adriana Gordejuela states that “they begin as external retrospections but end as internal ones” (2021, pp. 14-15). As for external and internal sequences, Maureen Turim explains that “an interior analepse is one that returns to a past of the fiction that remains within the temporal period of the rest of the narration” while “[e]xterior analepses jump back to a time period prior to and disjunct from the moment of the narrative’s beginning” (2014, p. 8). The levels of intricacy extend even further as Genette introduces distinctions between complete and partial instances to determine analepsis’ scope. If an analeptic sequence concludes before reaching the current present time in the narrative (creating an ellipsis), it is considered partial. Conversely, if the analepsis extends up to the current present time, it is classified as complete. When combined with the internal/external typologies, analepsis yields four potential categories: internal complete, internal partial, external complete and external partial (Genette, 1972, p. 101). Table 1 summarizes these categories and their definitions.

|

Type of Analepsis |

Brief Definition |

|

Internal Complete |

Past sequence that remains within the same temporal period of the main (present) timeline. It retells events, within that period, that end immediately where the current timeline (re)starts. |

|

Internal Partial |

Past sequence that remains within the same temporal period of the main (present) timeline. The events narrated within that period have already concluded in a time prior to where the current timeline (re)starts. |

|

External Complete |

Past sequence belonging to a temporal period before the main (present) timeline ever starts. It retells events, within that period, that end immediately where the current timeline begins. |

|

External Partial |

Past sequence belonging to a temporal period before the main (present) timeline ever starts. The events narrated within that period have already concluded in a time prior to where the current timeline begins. |

Table 1. Gerard Genette’s analeptic categories.

How do these different categories work when implemented as interactive and non-interactive sequences? What purpose do they serve? How are they presented? What kind of gameplay features have been introduced, if any? Do they work in tandem with the overall narrative goals and gameplay loop? All of these are foundational questions to address both playable and unplayable analepses. The Last of Us: Part II (Naughty Dog, 2020) presents itself as a great case study in this regard, due to the way it structures its narrative almost entirely around analeptic sequences (interactive and not) -- each of which offer a different dramatic tempo, heightening the stakes by constantly (re)contextualizing events and character motivations. As such, I offer a brief overview of key analeptic sequences in the game.

The Case of The Last of Us: Part II

The Last of Us (2013) is a two-part game series set in a post-apocalyptic USA ravaged by a fungal infection that turns humans into zombie-like creatures called “infected.” The first game follows Joel Miller, a hardened yet dejected survivor, who forms a paternal bond with Ellie Williams, a 14-year-old girl immune to the infection. The story is centered around their journey to find a group called the Fireflies, who believe Ellie’s immunity could lead to a cure. However, when they reach their destination, Joel quickly discovers that the surgical procedure to extract a potential cure would kill Ellie. Unwilling to lose her, Joel murders his way through the Fireflies’ hospital/headquarters to rescue a still unconscious Ellie from surgery, killing the lead surgeon in the process. At the end of the game, Joel lies to Ellie about what happened, claiming the Fireflies had given up on making a cure.

The sequel, The Last of Us: Part II, explores the aftermath of the first game’s ending, particularly Joel’s decision to save Ellie. The story starts with a confessional tone, in a scene in which Joel explains these events to Tommy, his brother. This scene establishes the gravitas of Joel’s decision, including his awareness of how it could shatter his relationship with Ellie if she were to uncover the truth. Five years later, the player is introduced to Joel and Ellie’s life in Jackson, a community they encountered in the first game. In this introduction, the player is made aware that their relationship has become significantly estranged, but the reasons for that estrangement are not revealed until much later. The game’s mostly peaceful introduction is abruptly disrupted by Joel’s brutal death at the hands of a group of ex-Fireflies led by a character named Abby. This event catalyzes a relentless quest for revenge that Ellie undertakes, propelling players through a three-day journey fraught with emotional and physical challenges as Ellie hunts down Abby. The most notable twist occurs when players are suddenly forced to take control of Abby half-way through the game and reexperience the same three days from her perspective, via a series of playable and unplayable flashbacks. The story resumes the narrative present at the moment of their first confrontation, in which Abby ultimately decides to spare Ellie. The characters’ last encounter occurs a few months later, after Ellie decides to hunt Abby once more. In the end, Ellie mirrors Abby’s decision and spares her, ending the cycle of violence, thus concluding the game’s story.

Returning to the previous point about time paradoxes in playable flashbacks, Juul argues that a “player’s actions in the past may suddenly render the present impossible” (2005, p. 159), but this can only be true if the choices afforded to the player are not properly accounted for by the game. Nonetheless, interactivity does not have to be limited to player choice (in dialogue scenarios, for instance), nor does it have to equate to combat encounters. The analeptic sequences in Part II, while playable, rarely feature any combat. When they do, only the “final, successful attempt” (Ruch, 2013, p. 3) is considered for the game’s “unfolding of events” (Aarseth, 1997, p. 125). The analeptic sequence “Finding Strings” is an example of how combat is integrated into the past without fail states affecting the narrative present. In Part II’s analepses, gameplay consists mostly of environmental exploration, in which the player can use interactable objects to either trigger conversations between characters, or solo commentary from them. These sequences do not have any “challenges” per se, but they are constructed with interactive elements that help players embody these characters in contrasting past and present circumstances.

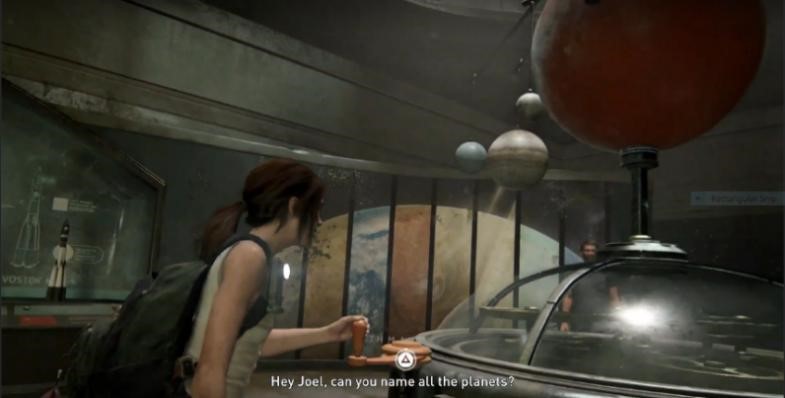

The chapter titled “The Birthday Gift” (external partial analepsis), for instance, can better illustrate the kind of past explorations being described. This sequence starts three years prior to the game’s main timeline, on Ellie’s sixteenth birthday. Joel takes her to the Wyoming Museum of Science and History as a surprise, since Ellie loves to read about dinosaurs and astronomy. The entire sequence has the player controlling Ellie as she excitedly moves through the museum accompanied by Joel: she climbs dinosaur statues, interacts with dinosaur skeletons in the exhibit, pretends to be the museum’s receptionist, comments on the scaled models of space rockets and tries on spacesuit helmets, among other activities. All these interactions with the environment either trigger brief cutscenes or in-gameplay dialogue between Ellie and Joel. For instance, when they reach the astronomy exhibition, the player is first prompted to tap the triangle button, which triggers a sequence where Ellie approaches an interactive solar system model (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Ellie interacting with the exhibit. Click image to enlarge.

Notably, players maintain control of Ellie throughout this sequence. These prompts are mechanically simple and can often be ignored if players wish, but they all nonetheless contribute to a sense of intimacy and closeness between Ellie and Joel that the player can experience through an embodied spectatorship. This flashback comes midway through the game, after players have already witnessed Joel’s death. It serves to heighten the pathos of Ellie’s loss by highlighting how estranged her and Joel seem to have become in the narrative present. It also develops the mystery around why and when they became estranged in the first place, although players may suspect at this point that Ellie has learned the truth about Joel’s lie from the first game. This is especially important in the context of Part II’s revenge plot, since both Ellie and Abby have deep rooted reasons for embarking on vengeance-fueled journeys. These motivations would lose their impact if past sequences such as the one described here were not present. This flashback also doubly serves to introduce players who did not play the first game to each characters’ relationships and the plot’s emotional stakes.

External partial sequences are the most common type of analepses in the game. These are scenes that happen prior to Part II’s inciting scenes set in Jackson. As flashbacks, these scenes convey that their events do not necessarily have urgent or immediate plot consequences as far as the game’s narrative present is concerned. Nonetheless, these events have long-lasting effects in the present, regarding character emotions and motivations. For instance, “The Birthday Gift” is a scene from the distant past that precedes all present events of the narrative, but it nonetheless brings to the forefront Joel’s parental role in Ellie’s life, as well as their close friendship. This information does not bear any consequence to the unfolding present events, but it is crucial for understanding Ellie’s inner struggles with loss. It is precisely because intimacy and calmness are central to this sequence that the scene contrasts so heavily with the bloodshed, violence and grief dominating the present time. This is how external partial analepses bring a sense of gravitas and pathos to the narrative. They create a contrast between the present and the past that shows players what has changed, become lost, or is still affecting the present. Joel and Ellie’s estrangement is given the proper development, tension and impact because players get to experience happy and positive moments before their relationship is strained. This prompts players to wonder what could have happened to cause tension between Joel and Ellie, and this lingering question will remain unanswered until the end of the third in-game day while playing as Ellie.

The chapters titled “St. Mary’s Hospital” and “Tracking Lesson” are two other examples of external partial analepses. In the former, the player controls Ellie as she searches through the Firefly hospital for answers about what happened during the final events of the first game. She eventually uncovers the truth and confronts Joel about it, resulting in a tearful argument between the two from which they never recover. The strong bond between Joel and Ellie portrayed in “The Birthday Gift” intensifies the emotional impact of the irreparable loss seen in “St. Mary’s Hospital.” In turn, both analepses heighten the emotional stakes of Ellie’s journey in the present time by revealing the layers of emotional struggle she has endured, which have been intensified by the events in the present. Furthermore, “St. Mary’s Hospital” is preceded by one of the most brutal sequences in the game, in which Ellie tortures another character. In this sequence, both the player and Ellie learn that Joel’s death came as a consequence of his actions from the first game. However, as the torture sequence plays out, the player remains unsure whether Ellie knows the truth. During “St. Mary’s Hospital,” players realize that Ellie has at some point in the years between games learned about Joel’s rampage against the Fireflies at the end of the first game, and now understands that she effectively lost Joel twice because of them. First through their estrangement, then with his murder.

The chapter titled “Tracking Lesson” provides crucial backstory for Abby. In this sequence, the player learns that Abby’s father is Jerry Anderson, the surgeon who was going to operate on Ellie and whom Joel murdered at the end of the first game. Once players learn Joel murdered Abby’s father, Abby’s actions are more fully contextualized for the player -- Joel did not die at the hands of a random act of violence; he died as a direct consequence of his own actions. The flashback scene starts with a player-controlled younger Abby searching through the woods for her father. When she finds him, the player sees their close relationship first-hand and learns more about them. Jerry’s relaxed attitude and humorous dialogue contrasts with Abby’s more uptight demeanor. The dialogue seems mundane: Abby has an adolescent romance brewing with a boy, which Jerry finds amusing; Jerry has a coin collection to which Abby contributes with a gift; Jerry comments on how he taught Abby wilderness survival skills. Similar to “The Birthday Gift,” the sequence contrasts the past’s intimacy and calmness with the violent present. It underscores Abby’s emotional motivation for murdering Joel. The scene illustrates Mould and Carmichael’s view of flashbacks: “The information revealed in a flashback might […] provide relevant backstory, or explain the motive behind a particular event” (Mould and Carmichael, 2014, p. 3). This sequence also allows players to draw parallels between Ellie and Abby’s journeys, effectively humanizing both characters and establishing their actions beyond mere judgments of good or bad. These are flawed human beings struggling to come to terms with the loss of their parental figures. These examples not only illustrate the long-lasting effects of past events, showcasing how an external partial analepsis can bring a plot’s unknown factors to the forefront, but they also provide clear parallels between both characters. This approximation between playable protagonists is part of the intricate, complex dynamics of the game.

There is only one instance of internal complete analepsis in Part II: Abby’s main timeline throughout the chapters “Seattle Day 1,” “Seattle Day 2,” and “Seattle Day 3.” The events presented here belong to the same temporality of the main fictional time, i.e., the same three days from Ellie’s perspective. The past sequence concludes by circling back to the present time of the narrative, at Ellie and Abby’s confrontation with one another. The deaths of some of Abby’s friends occur near the end of the analepsis, prompting Abby to eventually find Ellie. The emotional stakes of the confrontation are heightened because these deaths are freshly present, indicating the urgency of their motivational purpose for the narrative present. Until this moment, the player did not know Abby’s reason for going after Ellie. Furthermore, the external partial analepses contained within this internal complete analepsis are also presented as relevant for this confrontation -- not because they are needed for the plot to progress coherently, but because they alter the way players perceive Abby and thus the confrontation itself. Abby is no longer a simple villain and Ellie a simple victim -- these analeptic sequences expand on the interactions, motivations and experiences of these characters, and flesh out their deeper motivations.

The contrast between present and past events position players in what Peter Brooks calls “states of being beyond the immediate context of the narrative,” which “charge it with intenser [sic] significances” (Brooks, 1995, p. 2). That is, this sort of contrast allows the player to understand both minor and greater factors affecting character decisions and actions: “Manipulations of order may serve retardation and may also answer to requirements of narrational knowledgeability” (Bordwell, 1985, p. 78). This is also how “[t]he information revealed in a flashback might heighten the tension or sense of conflict felt by the audience” (Mould and Carmichael, 2014, p. 3). In the case of Part II, analepses arm the player with enough knowledge to perceive the ethical greater picture behind each character’s motivations, but does not provide them the means to influence any outcome. The player can see and play through contrasting past and present moments, absorbing the ways in which they impact and afflict the characters.

Playable analepses allow players to partake in a meaning-making process, where character emotions and actions are not only accessible but also a part of the gaming experience itself. These past segments are pivotal in bringing the necessary complexity to present events, and interactivity adds another layer of research potential. The interactive possibilities in such segments could, as exemplified in the case of Part II, provide an embodied spectatorship that integrates these experiences with the gameplay. This raises potential questions about the player-character relationship, as well as questions regarding how the playable characters are characterized beyond cutscenes. Playable analepses also present an opportunity to immerse players in different types of narration, potentially creating impactful twists through strategies like unreliable narration, which Naughty Dog has already experimented with in Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End (Naughty Dog, 2016). This game features an unreliable external partial analepsis that plays with unreliable narration in the character Sam Drake, the protagonist’s brother. In the chapter “Hector Alcázar,” the player gets to experience what seems to be a flashback of Sam’s as he retells a story about how he escaped prison. This analeptic sequence kickstarts the game’s plot with an action-packed prison break where Sam supposedly acquired a debt to a drug lord, propelling the protagonist, Nathan Drake, to help Sam find the lost treasure of the 17th century pirate, Henry Avery. Later in the game, both the player and Nathan discover that this story is a lie. While players may have picked up on Sam’s elusive, vague and mostly avoidant responses to any questions regarding his time in prison, on a first playthrough these clues could be easily missed. The player controls Sam during the flashback, allowing them to experience the events, and this helps cement the supposed veracity of the account. Thus, interactivity opens the door to expand the possibilities of analeptic sequences in many ways, but interaction’s ability to reconfigure the player’s sense of narrative stability represents a major topic to be explored in future scholarship.

Conclusion

Analepses are an understudied motif in game studies, despite their significant and widespread presence across the medium. They have received limited attention, especially when compared to related concepts like narrative or time in video games. This paper highlights this gap in research by exploring the few existing studies on the topic and their possible usefulness for understanding video games as cultural and artistic objects. It also provides a possible path for future research. Guy and Champagnat (2012), Mould and Carmichael (2014) and Anyó (2015) were mentioned and briefly discussed for these purposes, and, while their work is informative, helpful and valuable in different ways, it is unable to provide a comprehensive, critical and in-depth framework for approaching analepses in video games. The most notable and useful aspect brought to light from these essays, for the purposes of this study, is the potential for time paradoxes when writing analepsis into a game’s story, whether or not the analeptic scene is interactive. As I pointed out, this could be a legitimate concern in games with branching narratives and/or if the scene has significant impacts on player choices. However, this is an issue of narrative planning and design; that is, the integration or restriction of gameplay consequences into the narrative is applicable to present, past and/or future timelines within the game’s story. In the end, time paradoxes are not an inherent obstacle of analepses, but they might be an obstacle for their implementation, which could be overcome with proper planning and game design.

Gérard Genette’s formulation of “analepsis” in Figures III offers a valuable foundation to both literary and film studies (Bordwell, 1985; Turim, 2014; Gordejuela, 2021), and this essay argues that it can be just as useful in the context of video games. By applying such an approach, this article contextualizes the research within the same historic framework that served prior media. This methodology also provides a suitable basis for researchers to examine different categories and implementations of past sequences. Such work involves analyzing the interplay between playable and non-playable analepses, and their narrative significance. In this context, The Last of Us: Part II is offered here as a compelling example to illustrate the study of analeptic sequences in video games, since its narrative relies heavily on the juxtaposition of past and present sequences -- both interactive and non-interactive -- to provide gravitas and pathos to its story. By allowing players to experience and participate in these contrasting moments, the game underscores how the participatory nature of gameplay can involve players in the meaning-making processes associated with conveying characters’ emotions, actions and motivations. The brief analysis of Part II’s analeptic sequences demonstrates the importance of these devices -- especially of external partial analepses -- in shaping a game’s dramatic tempo and, consequently, bringing a character’s emotional journey to the forefront of the gaming experience.

Further research is needed to fully account for the significance and implementation of analepses across video games. There are many instances of analeptic sequences not covered in this essay which are just as worthy of analysis. As briefly mentioned, Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End not only features an unreliable external partial analepsis, but due to its story starting in medias res it features several other noteworthy analeptic instances. As analepses are intrinsically linked to temporality and order, researchers might also consider how games that implement time mechanics relate to analepses. For instance, a game such as Life is Strange (Dontnod Entertainment, 2015), which features playable flashbacks and the ability to rewind time in both the present and the past, raises interesting possibilities, especially concerning the matter of time paradoxes. By referring to established methodology from other media and analyzing specific past sequences across a variety of games, researchers may provide much needed insight into the artistic, cultural and narrative possibilities of analepsis in the field. Such an endeavor would contribute to the ongoing development of game studies, but also of video games’ capabilities as a unique medium.

Endnotes

[1] The definition and characterization of interactive storytelling as a concept is far from reaching a consensus (Crawford, 2013). It is sometimes utilized to generally describe narratives in videogames, since these tend to have stories and interactivity within them. However, the debate continues as to whether all narratives in a videogame are interactive just by virtue of being embedded in an interactive medium. For the purposes of this essay, I rely on Barbaros Bostan and Tim Marsh’s definition as a general guideline: “[…] [I]nteractive storytelling is a gaming experience where the form and content of the game is modified in real time and tailored to the preferences and needs of the player to provide a sense of control over the mutual discourse of play” (2012, p. 27). Thus, whenever the concept is mentioned henceforth, it will refer to games where the player can alter or influence the game world, the story’s path and/or its characters.

[2] While The Witcher released after the authors’ paper, it illustrates a contemporary example of analepses in Triple A productions that have been present since the 1990s.

[3] Genette’s concept of histoire (story) pertains to the contents of the story recounted in the narrative (récit) -- its plot, characters, temporality, etc. (1972).

[4] The original French reads: “[…] toute évocation après coup d’un événement antérieur au point de l’histoire où l’on se trouve.”

[5] Guy and Champagnat (2012) also rely extensively on these categories in their “manual” of the flashback.

References

Anyó, L. (2015). Narrative time in video games and films: From loop to travel in time. Game:The Italian Journal of Game Studies, 1(4), 63-74. https://www.gamejournal.it/anyo_narrative_time/

Bae, B. C., & Young, R. M. (2013). A Computational Model of Narrative Generation for Surprise Arousal. IEEE Transactions on Computational Intelligence and AI in Games, 6(2), 131-143. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCIAIG.2013.2290330

Bordwell, D. (1985). Narration in The Fiction Film. The University of Wisconsin Press.

Bostan, B., & Marsh, T. (2012). Fundamentals of Interactive Storytelling. AJIT‐e: Online Academic Journal of Information Technology, 3(8), 20-42. https://doi.org/10.5824/1309-1581.2012.3.002.x

Brooks, P. (1995). The Melodramatic Imagination: Balzac, Henry James, Melodrama, and the Mode of Excess. Yale University Press.

CD Projekt RED. (2015). The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt [Sony PlayStation 4]. Digital game directed by Konrad Tomaszkiewicz, Mateusz Kanik, and Sebastian Stępień, published by Published by CD Projekt.

Crawford, C. (2013). Chris Crawford on Interactive Storytelling. New Riders.

Eskelinen, M. (2012). Cybertext Poetics: The Critical Landscape of New Media Literary Theory. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Figueiredo, S. (2013). Space and Time in Ergodic Works. In xCoAx: Proceedings of the conference on Computation, Communication, Aesthetics and X (pp. 61-70). University of Porto. http://2013.xcoax.org/

Genette, G. (1972). Figures III. Editions du Seuil.

Gordejuela, A. (2021). Flashbacks in Film: A Cognitive and Multimodal Analysis. Routledge.

Granat, M. (2021). Video games as a supportive tool in the therapeutic process. Homo Ludens, 1(14), 65-82. https://www.ptbg.org.pl/vol-14/

Guy, O., & Champagnat, R. (2012). Flashbacks in Interactive Storytelling. In A. Nijholt, T. Romão, and D. Reidsma (eds.), Advances in Computer Entertainment. ACE 2012. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (pp. 246-261). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-34292-9_17

Hoek, M., Theune, M., & Linssen, J. (2014). Generating Game Narratives with Focalization and Flashbacks. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Entertainment,10(4), 9-14. https://doi.org/10.1609/aiide.v10i4.12758

Holmes, E. A., James, E. L., Coode-Bate, T., & Deeprose, C. (2009). Can Playing the Computer Game “Tetris” Reduce the Build-Up of Flashbacks for Trauma? A Proposal from Cognitive Science. PLoS ONE, 4(1), n.p. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0004153

Juul, J. (2005). Half-Real: Videogames Between Real Rules and Fictional Worlds. The MIT Press.

Lebowitz, J., & Klug, C. (2011). Interactive Storytelling for Video Games: A Player-Centered Approach to Creating Memorable Characters and Stories. Focal Press, Elsevier.

Mould, D., & Carmichael, G. 2014. Chronologically Nonlinear Techniques in Traditional Media and Games [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games, Florida, United States of America. http://www.fdg2014.org/proceedings.html

Naughty Dog. (2016). Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End [Sony PlayStation 4]. Digital game directed by Neil Druckmann and Bruce Straley, published by Sony Computer Entertainment.

Naughty Dog. (2020). The Last of Us: Part II [Sony PlayStation 4]. Digital game directed by Neil Druckmann, Anthony Newman, and Kurt Margenau, published by Sony Interactive Entertainment.

Quantic Dream. (2010). Heavy Rain [Sony PlayStation 3]. Digital game directed by David Cage and Steve Kniebihly, published by Sony Computer Entertainment.

Ruch, A. W. (2013, September). This isn’t happening: Time in Videogames [Paper presentation]. IE ‘13: Proceedings of The 9th Australasian Conference on Interactive Entertainment: Matters of Life and Death, Melbourne, Australia. https://doi.org/10.1145/2513002.2513569

Ryan, M. L. (1995). Allegories of Immersion: Virtual Narration in Postmodern Fiction. Style, 29(2), 262-286. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42946281

Ryan, M. L. (2001). Narrative as Virtual Reality: Immersion and Interactivity in Literature and Electronic Media. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Ryan, M. L. (2002). Beyond Myth and Metaphor: Narrative in Digital Media. Poetics Today, 23(4), 581-609. https://doi.org/10.1215/03335372-23-4-581

Square. (1997). Final Fantasy VII [Sony PlayStation]. Digital game directed by Yoshinori Kitase, published by Sony Computer Entertainment.

Turim, M. (2014). Flashbacks in Film: Memory and History. Routledge.

Wei, H. (2010, May). Embedded narrative in game design [Paper presentation]. Futureplay ‘10: Proceedings of the International Academic Conference on the Future of Game Design and Technology, Vancouver, Canada. https://doi.org/10.1145/1920778.1920818

Zagal, J. P., & Mateas, M. (2010). Time in Video Games: A Survey and Analysis. Simulation and Gaming, 46(1), 844-868. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878110375594