Gravity = Culture: Trans Liberatory Potentials and Limitations in Heaven Will Be Mine

by Niamh TimmonsAbstract

This article expands on the current game studies scholarship on transgender representation in games via a narrative analysis of the game Heaven Will Be Mine. Heaven Will Be Mine complicates and rejects problematic elements of transhumanism and also centers queer and trans desire. The game’s three endings map out different trajectories for queer and trans liberation. I locate the framing of settlement in space in the game’s narrative, and the lack of interrogating the dynamics of settlement, as a reification of settler colonial logics. As such, the trans liberation narrative of Heaven Will Be Mine, continues to maintain settler colonialism. Despite the game’s flaws, Heaven Will Be Mine is still an important game to think about the dynamics of trans liberatory potentials and limitations. In this article, I examine Heaven Will Be Mine as a form of trans liberatory potential and limitations while grounding the project in current landscape of game studies scholarship on trans representations.

Keywords: transgender, visual novel, settler colonialism, queer and trans desire, transhumanism

Introduction

Heaven Will Be Mine (Worst Girl Games, 2018) is a visual novel game, created by Aevee Bee and Mia Schwartz (both white trans women) that imagines the possibilities for queer and trans futures in space [1]. Heaven Will Be Mine aesthetically draws upon mecha anime, such as the Gundam franchise, and emphasizes queer and trans women’s desires in the midst of liberation for humanity in space. The game’s target audience is predominantly queer and trans women in the ways that it taps into queer and trans subcultures in internet spaces such X (formerly Twitter). The game makes space for queer and trans liberation through its refusal of traditional transhumanism and celebrates queer and trans desire. Yet, there are limitations in how the game’s narrative reifies settler colonial logics. Despite its flaws, the game’s narrative deserves attention and how it speaks to broader trends in game studies scholarship on how queer video games can serve as a form of potential liberation (Ruberg and Phillips, 2018). Given the genre of Heaven Will Be Mine, this article utilizes a narrative analysis but also focuses on the dynamics of play and player choice in the game. My analysis builds upon a foundation of discussing transgender representation in game studies and considers how readings of smaller budget games such as Heaven Will Be Mine may complicate the current landscape of this scholarship.

Heaven Will Be Mine is set in an alternate 1981 in which humanity is split between Earth and space colonies in the solar system. The colonies have terraformed multiple planets (and our Moon) into living environments. These colonies were initially set up to deter an alien threat outside the solar system called the Existential Threat. Now that the Existential Threat has been defeated, Earth cancels its space programs and calls for humans in space to return “home.” However, three conflicting factions differ on the next steps for humans to take. Each faction is represented by one of the game’s protagonists. Memorial Foundation, represented by Luna-Terra in the narrative, has established a base agreement with Earth to have humans return home. Cradle’s Graces, represented by Pluto, wants to pull all humans into space so as not to split humanity in two. Celestial Mechanics, represented by Saturn, wants to stay in space, as the human presence in Space has already made them into aliens and already not human. While the three characters represent these factions, none of the faction ideals are present in any of the multiple endings. For all factions, “Gravity” is the means in which their potential future can be actualized, via the manipulation of a Gravity Well on the Moon. The game repeatedly espouses the idea that “Gravity = Culture,” in this case they cannot be separated from one another. Gravity becomes the means in which reality is determined.

Heaven Will Be Mine takes a great deal of inspiration in many of its narrative tropes from the Mobile Suit Gundam anime franchise (MixedUpZombies, 2017). The developers borrowed narrative tropes from Gundam including human experimentation, military conflict between Earth and space colonies and mechas. It also invokes Gundam fan cultures via the attraction between the typically male mecha pilots through the game’s promotion from the game developers as “lesbian yaoi” -- a label that emphasizes both the game’s queer narrative and the fan culture of Gundam [2].

In this article, I consider how queer and trans liberation are possible and exist in the medium of video games, particularly visual novels. Bo Ruberg notes on current trends in queer game studies and scholarship, “Chief among them is an interest in the transformative experience of play and play itself as an expression of queerness” (2018, p. 549). Further, Ruberg writes that, “Considered through queer game studies, queerness emerges a set of desires and a way of being that are fundamentally linked to playfulness” (Ibid., p. 552). I want to keep Ruberg’s points here as a reminder about the connectivity they make between “play” and “queerness.” It is important to analyze the limitations the player has in Heaven Will Be Mine and how the player interacts with the narrative. I consider, what does it mean to read/play queer and trans liberation? Further, I utilize Ruberg’s framing of desire in terms of the game’s narrative themes of desire. I am aware of the gaps of Ruberg’s engagement with queerness and play, specifically that Ruberg’s framework does not account for trans people. While Ruberg does mentions trans people in their work, it remains unclear in their scholarship if and how transness and trans people factor into the queerness of video games. Despite these gaps in Ruberg’s frameworks, I believe it’s still useful as a foundation for my analysis here as they emphasize the intrinsic dynamics of desire and playfulness that underpins much of my engagements with Heaven Will Be Mine. At the same time, I’m reminded not only of the genealogical connections between trans studies and queer studies but the reductionism of “trans” that often occurs in queer theory. It cannot be divorced from what Gabby Benavente and Jules Gill-Peterson point out, “The critique of queer theory’s allegorization of trans people as the exceptional locus of gender trouble, with its attendant separation of queer and trans categories, still feels as relevant to us today as it was over a decade ago” (2019, p. 25). There needs to conversational space to think about the relationship between “queer” and “trans” with video games that accounts for the uniqueness, but also the intrinsic entanglement between the two categories, of both. Yet, an engagement with Ruberg’s work on play is still necessary [3]. I want to honor this critique and think about what it actually means to engage queer and trans narratives in a non-tokenizing manner. In my engagement with Heaven Will Be Mine I deliberately try to center trans people and trans- aspects of the game’s storytelling.

Further, I focus on how the experience of playing narratives of queer and trans liberation, in the context of Heaven Will Be Mine, also means being complicit in the expansion of settler colonial logics and structures. I join game studies scholars such as Yoel Villahermoso Serrano (2023) and game developers such as Elizabeth LaPensée in shifting attention to Indigenity, Indigenous issues and narratives, and settler colonialism in games. While a growing number of game studies scholars explicitly engage settler colonialism in their scholarship, there are few deep dives into the intersections between video games and settler colonialism. In this article, I am supplementing and complicating Ruberg’s scholarship on queerness and video games by emphasizing that queer and trans video games can be complicit in settler and racial violence and thus demand critical attention beyond their liberatory potential.

The game presents two notions of thinking about trans- as a category. First, there are multiple transgender characters (including Pluto and Luna-Terra) and their gender identities are largely understood, and respected (with some notable exceptions), in a way that mostly parallels our reality. Second, the game is rife with transhumanist themes and the ways those themes intersect with potential future(s) of humanity in space. Here, I am not interested in using “trans-” as a project similar to “queering,” however I do believe it is important to think about the linkages that Heaven Will Be Mine frames between transgender and transhumanism. For now, I am using transhumanist philosopher Max More’s definition of transhumanism, “Transhumanism is a class of philosophies of life that seek the continuation and acceleration of the evolution of intelligent life beyond its currently human form and human limitations by means of science and technology, guided by life-promoting principles and values” (Pilsch, 2017, p. 1). He expanded this definition years later to include that transhumanism “seeks ‘a rational philosophy and values system’ to recognize and anticipate ‘the radical alterations in the nature and possibilities of our lives resulting from various sciences and technologies such as neuroscience and neuropharmacology, life extension, nanotechnology, artificial ultraintelligence, and space habitation’” (Pilsch 2017, p. 1). This definition of transhumanism seeks to develop a rational and able-bodied human -- transforming them into an ideal orderly subject. Heaven Will Be Mine’s narrative largely rejects this framing, as I discuss later. However, the context of mainstream transhumanist thought is essential as it then provides a theoretical foundation which then the game avoids and moves past.

I begin with a conversation on trans representation in game studies scholarship then shift to consider the dynamics of visual novels as a particular genre. After this conversation on game studies scholarship and game genre, I divide this article into two sections to consider the possibilities and limitations in the game’s narrative. It is useful to frame both the value of the narrative and also its weaknesses. I want to interrogate what the fictional narrative(s) of liberation offers for queer and trans liberation and what that means for game studies. It is impossible, in the scale of this argument, to entirely break down the implications the game’s narrative has. Instead, I focus on an overview of aspects of the narrative that deserve to be investigated in relation to the potential of trans politics and futures. I focus on Heaven Will Be Mine as a means for game studies scholars to similarly pick up this work and further consider the use of play for liberatory potential. While I do not believe Heaven Will Be Mine’s narrative and its implications should blanket over all trans creative thought and politics, it provides opportunities to evaluate on what the potentials of trans creative thought offers trans politics. Further, this analysis provides space for thinking about trans liberation in game studies.

Trans scholarship in Games Studies

Counting studies (Shaw et al., 2019) and representational analysis (Thach, 2021) of trans representation in video games has placed the emphasis has largely been on releases from video game studios and publishers from prominent and major companies. Elsewhere, Jeremy Chow reads trans animalized ecologies in the representation of the Northern Red Cardinal in the board game Wingspan and the reception to the fan-made character Bowsette (2023). He proposes that these representations and fan-made cultures signal that video games, and games broadly, have always been trans. While I appreciate Chow’s reading of Wingspan and Bowsette, I don’t believe that he provides enough evidence to justify the claim that games have always been trans. In fact, Adrienne Shaw et al (2019) and Hibby Thach’s (2021) scholarship point toward only a recent emergence of trans representations. A reading that “transes,” a project that I remain dubious about, fails to consider lived experiences, even in readings of fictional representations of trans people and how that creates a trans representational politic (Thach, 2021) that has consequences for trans communities and individuals.

Aiden Kosciesza maps out the ways that transgender NPCs (non-player characters) are often used as a form of “moral service” for protagonist narratives. Kosciesza describes this as “magical transness,” which he derives from the “magical negro” trope, in that both “exhibit primordial folk wisdom rather than intellect and exist in the liminal space between rejection and acceptance” (2020, p. 199). Although he does mention that “racial, gender, and anti-LGBTQ+ discrimination are distinct and should not be conflated” (Kosciesza, 2020, p. 204) the development of “magical transness” from the problematic trope of Black characters does risk a conflation that he says he wants to avoid. Furthermore, Kosciesza’s analysis only focuses on trans NPCs and doesn’t account for the differences in representation for transgender protagonists.

Such emphasis throughout this scholarship misses out on analysis of lower budget studios and single person developers. By focusing on Heaven Will Be Mine and published by smaller companies, I hope to open up space in game studies analysis of games with lesser distribution. My reading of Heaven Will Be Mine not only looks at the particular dynamics located in the game’s narrative but also how that’s entangled with trans communities and thought broadly.

Visual Novel as Genre

Visual novels are a type of video game with minimal interaction from the player. Gameplay in the genre is primarily limited to the player scrolling through text accompanied with visuals of the characters and setting, and often accompanied by music. Beyond this, player choice is limited to choosing different pathways for the narrative [4]. Despite these gameplay limitations, visual novels offer the possibility for marginalized game creators and players to create or find themselves in narratives that isn’t as possible in games created by a major game studio or developer. Aimee Hart, writing in Rock, Paper, Shotgun, describes the importance of visual novels as a genre, “LGBT+ visual novels, along with LGBT+ developers who put in a huge amount of work to deliver unique, respectful and interesting stories, are challenging my old mindset completely. Instead of settling for the next best thing of having a gay character who is there but later killed off, or is sad and alone, these VNs allow queer sexuality and love to play a role of importance” (2019). Hart continues by pointing out that visual novel software such as Ren’py and Twine enable queer and trans individuals to develop games without the training and labor compared to that of larger game studios and developers. By working at this level, game creators are able to craft the stories and games they wish to create without the barriers that larger budget games might have.

Alice Bell writes on Aevee Bee’s, one of Heaven Will Be Mine’s creators, framing of visual novels, “she said that she thinks there’s nothing that happens in narrative design in all other games that doesn’t happen in a small way in VNs, citing all the different types of conversations and UIs that are present in HWBM. But Bee also said that we talk a lot about visual novels as a low cost way of making a game, but forget that it’s also a low cost way of making a novel -- easier than going through a big publisher, or trying to self publish somewhere like Amazon. And that makes it easier to reach an audience” (Bell, 2019). As such, this enabled Heaven Will Be Mine to more easily reach its desired queer and trans audiences.

While visual novels do enable possibilities for queer and trans storytelling with audience engagement in a way that’s not possible elsewhere, it remains a genre confined by limitation. In Heaven Will Be Mine, this is limited to choosing one of two options in the game’s multiple encounters between the three protagonists that serves the purpose of “combat.” “Combat” between the different factions largely happens in fights between Ship Selves, giant mechas that cannot be destroyed. Each encounter has the possibility for two scenarios that differ but do not affect the game’s ending. Instead, the choices count towards an alignment system that changes the possible endings for the game. Throughout this article, I describe the dynamics of choice in the game, what they entail, and the implications for trans liberatory possibilities but also limitations.

Trans Possibilities

She is constantly moving away from you the only way she can.

She never turns her face from you because of what you might do.

She will outlive everything you know.

-Jennifer Espinoza, “The Moon is Trans” (2016)

I argue that Heaven Will Be Mine imagines alternative trans futures, as well as our present moment. To do so, I look at the common themes throughout the game’s narrative and the three character’s endings. The major themes that emerge are the ways in which the game engaged transhumanism, which I approach from a disability perspective, and queer/trans desire. Each narrative produces a similar, yet distinct take on the existence of humanity in space, that offer important possibilities for trans politics. I also look at the three possible endings and unpack the implications of each.

Whereas most theoretical conceptualizations of transhumanism center around ideas of improving the human body, Heaven Will be Mine’s narrative suggests a more organic version of transhumanism. As noted earlier, via Max More’s definition, transhumanism is concerned with a forced effort to surpass the “limitations” of humanity. As Melinda Hall states, “Transhumanists pursue extended autonomy, multiplied choice, and enhanced moral acumen…In an amplification of the effects of bioethics more generally, transhumanism is tied up in the task of defining who counts and, therefore, who gets to live” (2017, p. xii). For many theoretical transhumanists, humanity can only be surpassed through the direct intervention of technology. It is technology that remakes the human into the post-human subject. Heaven Will Be Mine rejects this notion of transhumanism on two fronts. First, humanity in space is “organically” thought of as transhuman in that they became “alien” by no longer living on Earth. In an encounter between Luna-Terra and Pluto, Luna-Terra says, “I wonder how they expected they could unite humanity against aliens when they found us so alien. We will always become our own Existential Threat. Every human understood that but them. No wonder Earth rejected us” (Worst Girl Games, 2018). Humanity in space then is already post-human. In other words, being a non-normative body is what makes someone un-human or alien. It opens up a space to think about the human-ness of queer and trans bodyminds [5]. Second, the “deviance” of subjects that transhumanists wish to correct and the lack of desire to become technologically transhuman suggests a more complicated approach to the topic. Both Pluto and Saturn were un-consensually tested and experimented on to become “better humans” in order to combat the Existential Threat. Using traditional transhumanist frameworks, this makes sense in accordance with the theoretical doctrines of transhumanism. However, the game offers two complications to this. First, the modification of Pluto and Saturn, and other unnamed pilots, was forcibly done. There is no explicit desire mentioned for these modifications; rather, they were thought of as “necessary” by someone else for the “betterment” of humanity. Second, Saturn is aloof and consistently disobeying orders, behavior outside the expected norms of the transhumanist subject. Her entrance in the narrative comes when she hacks a new experimental Ship-Self that was intended for another pilot. The unruly Saturn then becomes a “flaw” in the design of the transhuman subject to be orderly. Instead, she is spontaneous and chaotic. On the other hand, Pluto is cast as the ideal, until she rejects the goals of Cradle’s Graces in her ending or allies with the other protagonists in their endings.

Lastly, the creators refuse to indulge the ableist tendencies of transhumanist theory. Hall argues that transhumanist rhetoric deliberately tries to erase disabled bodies: “Disability is a matter of chance that must be brought to heel. Being open to chance is characterized as risky and imagined to hold us back from new achievements” (2017, p. xix). The Ship-Selves that are piloted can be thought of as a bodily extension that erase the “defects” of the body. After all, they are supposed to be invincible against one another and can heal themselves. The game begins to unravel this via Luna-Terra’s Ship-Self which features a prominent scar. This scar should be able to heal, yet, remains. The scar is a visible reminder of the wounds of conflict and Luna-Terra’s refusal to heal the scar embodies a refusal of curative politics (Clare, 2017; Kim, 2017). The Ship-Self, and thus Luna-Terra by extension, are thus maimed bodies (Puar, 2017). Saturn struggles with being a survivor of being someone experimented on, implying the psychological effects of non-consensual transhumanist practices. While these experiments were done with the intent of creating transhumanist ideal subjects, the forced technological experimentation on Pluto and Saturn itself is disabling via its production of trauma.

Heaven Will Be Mine’s approach to transhumanism offers us important points and questions to ponder in relation to transhumanist rhetoric, ethics, and practices. What does it mean then to “make” transhumanist bodies? How is the trans- body situated in relation to a potential “ideal body?” What violence does that carry with us? How do we create non-ideal bodies? Moreover, what do these bodyminds do for our resistance(s)?

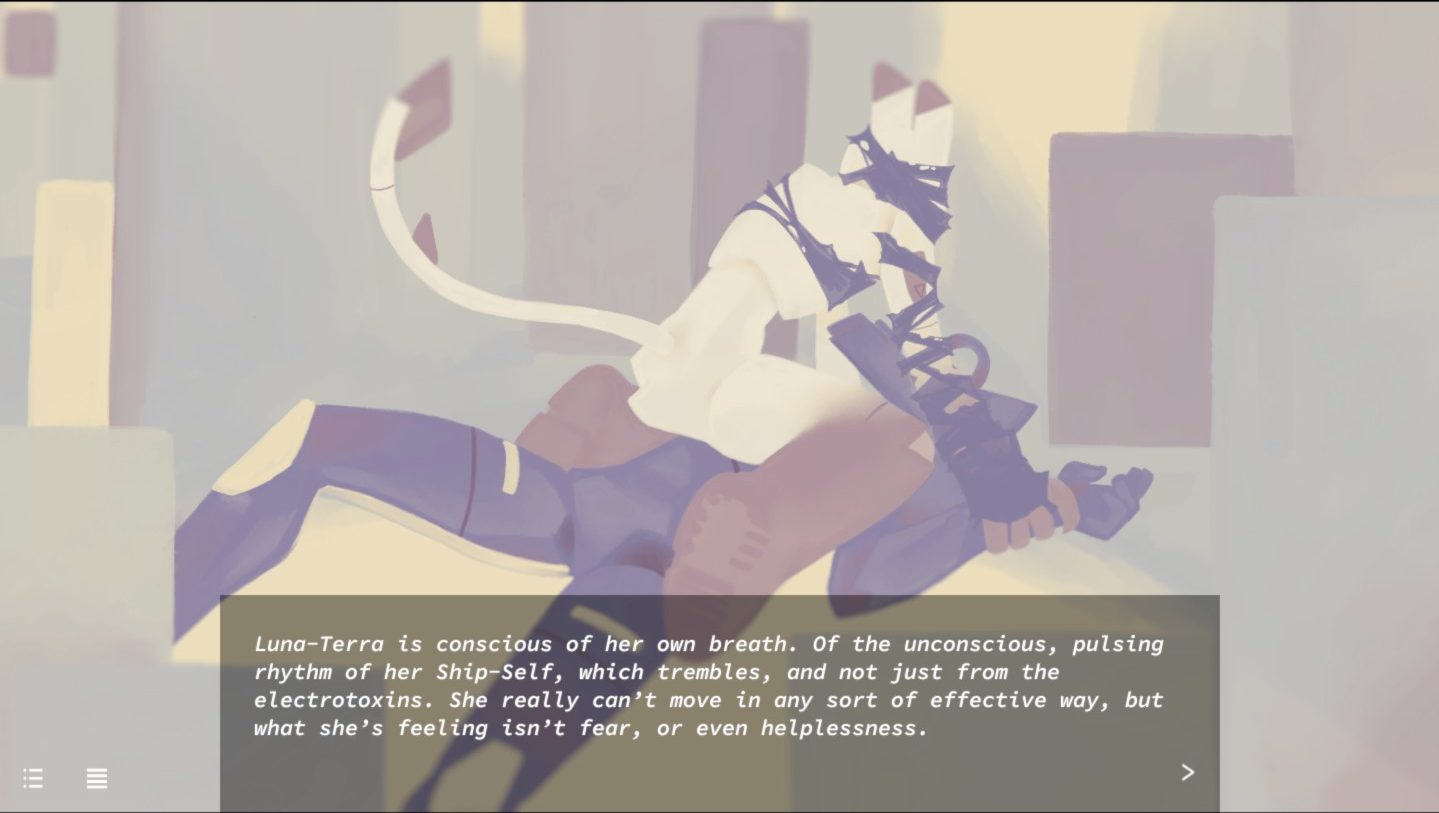

Instead of dwelling on the violence of transhumanism, the game’s narrative is centrally interested in exploring the dynamics of queer and trans desire. During a “combat encounter” with one of the other playable characters, the player is given two choices that impact their alignment with the factions. Each choice also has a unique scenario between the two pilots. One scenario might produce a reality where the two characters make-out and are implied to have sex (this part is not shown or controlled by the player), while another might be rife with sexual tension but where no physical intimacy occurs. Several “fights” between the Ship-Selves serve as metaphors for sex. For example, in one encounter between Saturn and Luna-Terra, Saturn uses a toxin on Luna-Terra’s Ship-Self in order to dominate her (Figure 1). In the end, these encounters do little to change the three possible endings (instead, mostly determining which ending happens). However, it is impossible to play the game and not either see a make-out session or metaphorical sex battle. As such, the narrative centrally pivots around desire. Pillowfight Games, a co-producer of the game, promoted the game in a way that directly acknowledges this, “Your choices determine which of three factions will emerge victorious and determine the fate of space -- but if you just pick based on who you wanna kiss, we won’t get mad” (n.d.). As such, desire can be centered in both the way the game is meant to be played and the narrative centrality of desire.

Figure 1. A Ship-Self "fight" between Saturn (top) and Luna-Terra (bottom) (Worst Girl Games, 2018). Click image to enlarge.

So far, I have been discussing the overall themes of the game’s narrative. I want to shift focus and consider the separate divergent realities that the creators imagine via the game’s endings [6]. All of the endings consider how Gravity, and thus culture and reality, can be altered to create new conditions for humanity in space.

Pluto (Cradle’s Graces ending)

Pluto’s ending is the only scenario in which reality is not transformed. Instead, of Cradle’s Graces attempt to pull all of humanity into space, Pluto keeps humanity separate between Earth and space. Humans in space inhabit Venus, given its ideal conditions for Ship-Selves, and the war that was imagined by Celestial Mechanics happens here. However, humans from Earth are forced into space and Ship-Selves in order to fight the rebelling humans. As Luna-Terra points out about Ship-Selves, “Death defeats the purpose of conflict, which is how humans communicate and change. Death and war end conflict. The Ship-Self signals the fundamental transformation of human conflict from suffering into love” (Worst Girl Games, 2018). The war that Pluto has begun is not one then of suffering, rather one where humans can grow via conflict that does not have physical consequences like traditional warfare does. People can fight in their Ship-Selves and learn to grow with one another. And often this growth happens through conflict and combat as described in the endings narration, “Earth isn’t ready to accept us, and we’re not ready to forgive Earth. That’s okay. We don’t have to be. Let’s just fight about it. Let’s fuck over it. Let’s break up and get back together again over it. If we lose, we lose on the terms we set, and that proves our point, so haha, we win. If you hate that logic, and think it’s stupid, come over here and mess me up about it. Come here and make out with me about it” (Worst Girl Games, 2018). Not only does the ending tie into the game’s overarching themes of indulging queer and trans desire but it highlights that change and growth happens with conflict not despite conflict. This model parallels moves toward community and self-accountability within intimate and activist spaces, where harm can be addressed, healed, and to transform our communities and worlds.

Luna-Terra (Memorial Foundation ending)

Luna-Terra’s ending is the least philosophical of all the endings. Instead, of bringing humanity back to Earth, she makes the Moon a counterpart to the Earth. A mirror image of sorts. As most of humanity in space is implied to be queer and trans, the Moon is then transformed into a queer trans counterpoint to the heterosexual cisgender Earth. This echoes Jay Prosser’s argument regarding trans literary narratives, “Mirror scenes in transsexual autobiographies do not merely initiate the plot of transsexuality…mirror scenes also draw attention to the narrative form [of] the plot” (2004, p. 100). In this sense, the establishment of the Moon as the mirroring of Earth is also then one of trans- becoming. It is a new world that queer and trans people can be their “authentic” selves without having to fundamentally challenge their notions of humanity. Further, in this ending, the Moon is pulled closer to the Earth establishing a greater relation between queerness and transness of those in space and those on Earth. Luna-Terra’s ending focuses on the connectivity with one another in the configurations of a more recognizable reality. As described in the ending narration, “Whether it’s a good universe, or a terrible one, Luna-Terra doesn’t intend to find out. She’s hopelessly attached to this universe. What we do want, is to get a little closer” (Worst Girl Games, 2018). It is the only ending that does not include the Ship-Selves. Instead, the three protagonists share an apartment, living out their days as a polycule instead of spectacular pilots or something more.

Saturn (Celestial Mechanics ending)

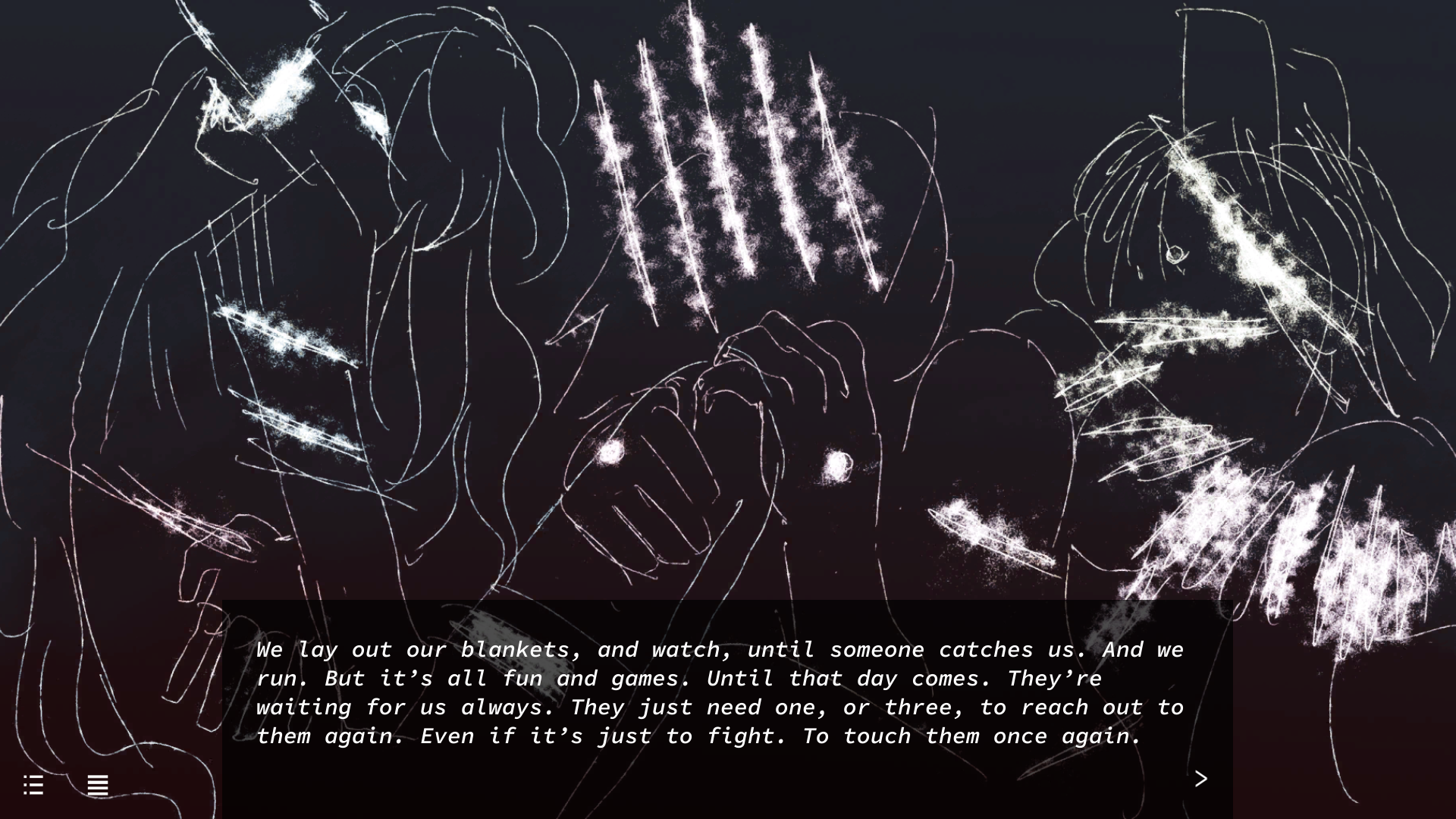

Saturn’s ending is the most radical of the three endings. While Celestial Mechanics wanted to have humans in space transcend their humanity and become alien to the humans on Earth. The rationale for removing oneself from humanity is the notion that humanity already ostracized those in space and so Celestial Mechanics wanted to take that removal from humanity one step further. Saturn, like most things she does in the narrative, rejects this removal and instead changes Gravity in such a way that all humans can be themselves and one with reality simultaneously. For example, the three protagonists then become a series of constellations that signify this change and the bond between Saturn, Pluto, and Luna-Terra (Figure 2). The narration suggests that touching one another happens through them and further, “Lazy sex in a morning bed, except the bed is curvature of space-time and sex is something so obscene it would make your mind implode to consider it” (Worst Girl Games, 2018). This kind of restructuring of humanity and bodies suggests an entwinement with the natural “bodies” of the universe itself. This parallels a point made by Camille Nurka regarding the connections between trans- and animals. “The trans project reenvisions animal embodiment anew and provides a critique that is critical to any philosophy which seeks to interrogate the ontological status of organic bodies living in relation to one another in technologically mediated environments” (2015, p. 216). As such, Saturn’s alteration of reality is itself a new transhumanist project that further destabilizes the category of “human” while simultaneously tapping into the connections we build with one another -- not through technology but through how we imagine and center ourselves as human.

Figure 2. Still from Saturn's ending where the three protagonists become constellations (Worst Girl Games, 2018). Click image to enlarge.

Given the nature of these three endings, I do not posit that we should think about them literally in relation to contemporary trans politics. Rather, they do signal how trans creative work can fundamentally question how we liberate ourselves, the futures we produce, how we relate to one another, and we stay/disrupt our human-ness.

Trans Limitations

As much as I want to focus on what I believe Heaven Will Be Mine does that pushes trans- narratives forward, other parts make me wonder about how the white trans imaginary is stuck elsewhere. In this case, specifically, with regard to race and settler colonialism. This is rooted initially with me wondering how the world of the game understood race in its alternate timeline. There are no hints to the racial history of Earth, humanity, space and no context for possible racial structures. Pluto is racially coded, via her illustrations, but it’s not explicitly mentioned or factored into the game’s narrative. Instead of focusing on how race is represented or imagined in this alternate history, I want to think about how the concept of settlement in space and how queer and trans liberation in the game’s narrative is linked to settler colonialism. I use anti-settler colonial and Indigenous critiques to think about how the notion of “settlement” in the game echoes settler colonial frameworks.

In 1962, President Kennedy described the “New Frontiers” as located in space exploration and new scientific development. This borrows from Vannevur Bush’s earlier claim that science is “the endless frontier” (Messeri, 2017). As Lisa Messeri points out, “Of all these new frontiers, outer space was the most literal: It was the final frontier, as Star Trek’s Captain Kirk intoned in 1966. Astronauts became the new cowboys, training for trips to the moon in the deserts of American West. Space was their dueling ground, where NASA sought to outshoot Soviet communism with American democracy” (Ibid.). Messeri’s analysis puts the space as frontier metaphor in conversation with Frederick Jackson Turner’s “Frontier Thesis,” where the frontier becomes the space that fosters Euro-American settler democracy. This stems from the genocide of Indigenous peoples and the loss of many Indigenous nation’s traditional territories to settler occupation. The “frontier” metaphor in outer space then remaps settler violence into space. While space exploration does not duplicate the same sort of physical violence deployed against Indigenous peoples, the legacy of that violence is stuck in space via the usage of these metaphors. It should be noted that space in Heaven Will Be Mine is also a defensive realm against the Existential Threat, paralleling the politics of space exploration as Messeri mentions between the U.S. and the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

As discussed earlier, Heaven Will Be Mine’s narrative centers around how humanity will exist in relation to settlement in space. Planets and the Moon are terraformed to become habitable for humans, just as Indigenous peoples’ lands have been altered for settler farming, towns, and cities. All three factions goals, and the endings of the three protagonists, all point to continued human settlement in space without considering what the act of settlement entails. As I have suggested, the act of settlement in space, fictional or real, is an act of remapping settler violence. So, while the game presents a narrative of human liberation in space, it does so without questioning what the act of settlement means in the first place. Even though the game is entirely speculative, and thus would exist in a separate form of reality, as Sami Schalk (2018) would suggest of speculative fiction, its inability to question settlement broadly and its effects only contributes more to our reality and the inability of addressing non-Native settler status. What does it mean to frame the sort of narrative the game wants to use without reifying settler colonialism?

Returning to the notion of play as discussed at the beginning of this argument, it is important to consider how the act of “play” also factors into settling logics prevalent in Heaven Will Be Mine. In his study on Americans “playing Indian” throughout U.S. history to enact an American identity, Philip Deloria writes, “Americans have returned to the Indian, reinterpretating the intuitive dilemmas surrounding Indian-ness to meet the circumstances of their times” (1998, p. 7). While Heaven Will Be Mine’s narrative nor do the player’s actions enact a playing of “Indian” in the way that Deloria describes, there should be a conscious effort to think about what it means to remain playing as a settler. Earlier I pointed out how the player’s choices inform the ending of each playthrough, and thus how humanity remains in space. Regardless of the player’s choices, humanity will remain as settlers in space. The player remains complicit in the imaginings of how space will remain settled. This reading departs from the engagement of play and queerness that Bo Ruberg offers. As I have suggested earlier, there is a capacity for the player to participate in the potentials for queer and trans liberation. However, this also comes with the violence and complicity of play as suggested by Deloria and my reading of Heaven Will Be Mine here. In an engagement with the play of video games and the play of kink, Mattie Brice notes, “The things you consent is its own context, and it allows play to be both affective and expressive. Video games tend to obfuscate the effect they will have on the player because they place importance on content and entertainment value” (2017, p. 80). If Brice’s points are considered in relation to the minimal amount of choice present in Heaven Will Be Mine and its settler-in-space endings, the player could be seen as not only as complicit in settler logics but are also denied being anything else that might challenge that.

In Daniel Heath Justice’s critique of Avatar, he points that, “In distancing the audience from any complicity with these evils on our world, the film actually fails to take seriously what would really be required of the audience to effect real and lasting change” (2010). Thus, the viewer of Avatar is treated as an objective party to the colonization and resistance of the fictional Indigenous Na’vi. Heaven Will Be Mine is also guilty of distancing the player via the limitation of gameplay interaction. It is impossible for the player to change the way that one of the characters thinks and talks about humanity being in space. Instead, the game idealizes space, as Pluto tells Luna-Terra in one encounter: “First, we never would have been allowed to grow up like we here back on Earth, second, space is cool, third, giant robots are impossibly cool and nothing you can possibly say will change that fact” (Worst Girl Games 2018). The reference to growing up in space versus Earth suggests that space offered a possibility for queer and trans life to proliferate. In Heaven Will Be Mine, queer and trans life, resilience, and liberation is made possible via the settlement of space. As mentioned in Pluto’s quote, space is objective in its meaning making and is “cool” rather than considering the practice of settlement being deeply rooted in settler colonialism. Because Heaven Will Be Mine dodges the question of settlement, the narrative of queer and trans liberation should be read as being engaged in the larger settler colonial structure.

I point to the work by Indigenous scholars in how they imagine speculative fiction and potential ways that non-Natives can learn from Native queers and Two-Spirit peoples. Lindsey Catherine Cornum points out that “Indigenous Futurism is in part about imagining and cultivating relationships to land/space and each other. These texts, artworks, ideas are attempts at learning to live together within the entanglement of suffering, resilience, and creation. Indigenous Futurism illuminates the vast network of complex connections that link everything in this world, and then further on out, to everything in other worlds” (n.d.). This echoes similar ideas that Daniel Heath Justice proposes for a form of critical kinship for Indigenous peoples. He frames four questions of critical kinship, “How do we learn to be human? How do we become good relatives? How do we become good ancestors? How do we learn to live together?” (2018, p. 28). It is striking how much Heaven Will Be Mine strives to answer these questions, or at least questions parallel to these particularly on what it means to be human. However, the game does not reach a point where it can address the politics of settlement in relation to forms of settler colonialism. Thus, while the game does offer significant parallels to consider unpacking settler-ness, it never reaches a point where it does so.

I do not believe that Heaven Will Be Mine’s inability to address settler colonialism is an isolated issue, rather one rooted in much of trans and queer liberatory politics. I do not want to end this section without addressing the potentials for settlers to work towards unpacking and resisting settler colonialism. As Scott Lauria Morgensen argues, “Non-Native queers responding to Two-Spirit critiques must shift our work from narrowly defending our own gendered or sexual lives, to challenging colonial heteropatriarchy and our power as settlers as central to any work we do” (2011, p. 148). The available scholarship points to queers in general, but I think it is also important to consider that non-Indigenous trans people are interconnected with this as they are not exempt from participation in settler structures. Trans studies and communities, given the theoretical connections between the field and queer studies, that Gabby Denavente and Jules Gill-Peterson (2019) describe, also have responsibilities to Indigenous communities. Thus, non-Indigenous trans people are just as responsible as queers to settler colonialism. Elizabeth Carlson (2016), in an examination of the relationship of Indigenous methodologies and settler anti-colonialism, argues that for reading such scholarship in relation to Indigenous sovereignty. Together we can think of centering Indigenous peoples and their struggles as central to our politics of liberation. It requires self-reflexivity and a willingness to grow and change.

“Because All We Have Are Human Things:” Conclusion

Because Heaven Will Be Mine is a visual novel that gives the player few opportunities to decide on how they might engage with the game’s narrative implications it denies players the chance to resist problematic elements while also reveling in its themes of desire and potential liberation. This means that queer and trans players, the targeted audience for the game, are not active participants in scenes where there is flirting and sexual tension between Luna-Terra, Pluto and Saturn. Rather, they are relegated more akin to a voyeuristic role. One that denies player agency but still enables potential player desire. At the same time, this same gameplay dynamic inhibits players changing narrative elements of Heaven Will Be Mine’s narrative that a player might not want to participate in, such as the settler colonial implications that I’ve discussed.

My reading and discussion of Heaven Will Be Mine has several potential implications for game studies scholarship. It places emphasis on lower budget and/or do it yourself (DIY) creators of games and the dynamics of representation of minoritized groups and how they design narratives in their games. Further, my reading complicates discussions on queer and trans games that necessitates nuanced readings by also focusing on potential harmful implications within these games. Lastly, it builds on a growing trend in game studies scholarship that interrogates how games contribute to the structure of settler colonialism. In this article, I have woven these threads together in order to think about the dynamics of possibilities and limitations within the narrative of Heaven Will Be Mine.

Despite my critiques of Heaven Will Be Mine, I don’t believe in dismissing the game entirely. Rather, I want to embrace the potentially liberatory dynamics of the game’s narrative while also challenging the ways it perpetuates problematic and harmful constructions of space in relation to settler colonialism. I came to this project because I am endlessly excited about the potentials of trans creative imaginaries and what kind of potential they offer us. This stems from a worry I have about the reliance of trans women’s narratives on realism or potential realism. What I find worrying is that, while these narratives do have importance, they fundamentally ground our futures in struggles and tensions of existing within a cisheterosexual dominated society. My interest in trans (women’s) speculative fiction and science fiction is the opening up and imaginations of new worlds that are not contingent upon the structures of our own. The imaginaries are not always going to be perfect, and they are certainly going to have limitations, but taking these steps is critical to building new worlds. We can work through the limitations of our imaginaries and work to unhinge them from their problematic elements. I don’t want to treat Heaven Will Be Mine as disposable. I hold its problems with its potentials for this reason. Trans imaginaries are a crucial part in taking steps towards the futures that we want and need.

Endnotes

[1] Heaven Will Be Mine fits into their larger oeuvre of queer and trans storytelling. Their prior visual novel We Know the Devil (Worst Girl Games, 2015) explored queerness with teens at a summer camp, utilizing a horror genre, and emphasized the potentials of queer/non-normative expression.

[2] “Yaoi” is a Japanese term and genre of manga/anime of love between male characters. By calling the game “lesbian yaoi” it’s also suggesting the trans nature of the game’s protagonists.

[3] I believe that queer critiques are still relevant to trans studies and scholarship as the two are genealogically related. Trans scholarship doesn’t need to reinvent conversations that have already occurred in related disciplines and claim them as their own.

[4] There are other visual novel games such as the Ace Attorney franchise where there isn’t multiple pathways but there are correct interactions made by the player in order to progress the narrative.

[5] The term “bodyminds” comes from Disability Justice organizers and writers who refuse the Cartesian split of “bodies” and “minds.” Bodyminds highlights the intrinsic relationship between the two.

[6] Regardless of the ending, all three characters act in unison with one another despite their factions and different endings.

References

Bell, A. (2019). “The writer of Heaven Will Be Mine on how she made 2018’s most interesting game.” Rock, Paper, Shotgun. https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/the-writer-of-heaven-will-be-mine-on-how-she-made-2018s-most-interesting-game

Brice, M. (2017). “Play and Be Real About It: What Video Games Could Learn From Kink.” In B. Ruberg and A. Shaw (eds.) Queer Game Studies, edited by Bonnie Ruberg and Adrienne Shaw. University of Minnesota Press.

Carlson, E. (2016). “Anti-Colonial Methodologies and Practices for Settler Colonial Studies.” Settler Colonial Studies, 7(4), 496-517. DOI 10.1080/2201473X.2016.1241213.

Clare, E. (2017). Brilliant Imperfections: Grappling With Cure. Duke University Press.

Chow, J. (2023). “Games Have Always Been Trans.” TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 10(3-4), 388-409. DOI 10.1215/23289252-10900914.

Cornum, L. C. (n.d). “The Creation Story is a Spaceship: Indigenous Futurism and Deep Colonial Space.” Voz-À-Voz. http://www.vozavoz.ca/feature/lindsay-catherine-cornum

Deloria, P. (1998). Playing Indian. Yale University Press.

Denavente, G. and J. Gill-Peterson. (2019). “The Promise of Trans Critique: Susan Stryker’s Queer Theory.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 25(1), 23-28. DOI 10.1215/10642684-7275222.

Espinoza, J. J. (2016). “Five Poems by Joshua Jennifer Espinoza.” Pen America. https://pen.org/five-poems-by-joshua-jennifer-espinoza/

Hall, M. (2017). The Bioethics of Enhancement: Transhumanism, Disability, and Biopolitics. Lexington Books.

Hart, A. (2019). “Why visual novels are a haven for LGBT+ stories.” Rock, Paper, Shotgun. https://rockpapershotgun.com/why-visual-novels-are-a-haven-for-lgbt-stories

Justice, D. H. (2010). “James Cameron’s Avatar: Missed Opportunities.” Indianz. http://www.indianz.com/boardx/topic.asp?ARCHIVE=true&TOPIC_ID=39583

Justice, D. H. (2018). Why Indigenous Literatures Matter. Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Kim, E. (2017). Curative Violence: Rehabilitating Disability, Gender, and Sexuality in Modern Korea. Duke University Press.

Kosciesza, A. (2020). “The Moral Service of Trans NPCs: Examining the Roles of Transgender Non-Player Characters in Role-Playing Games.” Games and Culture 18(2), 189-208. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120221088118

Messeri, L. (2017). “Why we need to stop talking about space as a ‘frontier.’” Slate. http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2017/03/

why_we_need_to_stop_talking_about_space_as_a_frontier.html

MixedUpZombies. (2017). “Heaven Will Be Mine-Worst Girl Games Interview (PAX East 2017).” MixedUpZombies. https://www.mixedupzombies.com/interviews/2017/4/18/heaven-will-be-mine-worst-girls-interview-pax-east-2017

Morgensen, S. L. (2011). “Unsettling Queer Politics: What Can Non-Natives Learn from Two-Spirit Organizing.” In Q. Driskill, C. Finley, B. J. Gilley, and S. L. Morgensen (eds.), Queer Indigenous Studies: Critical Interventions in Theory, Politics, and Literature. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Pillowfight Games. (n.d). “Heaven Will Be Mine.” Itch.io. https://pillowfight.itch.io/heaven-will-be-mine

Nurka, C. (2015). “Animal Techne: Transing Posthumanism.” Transgender Studies Quarterly, 2(2), 209-226. DOI 10.1215/23289252-2867455.

Pilsch, A. (2017). Transhumanism: Evolutionary Futurism and the Human Technologies of Utopia. University of Minnesota Press.

Puar, J. (2017). The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability. Duke University Press.

Prosser, J. (2004). Second Skins: The Body Narratives of Transsexuality. Columbia University Press.

Ruberg, B. (2018). “Queerness and Video Games: Queer Game Studies and New Perspectives through Play.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 24(4), 543-555. DOI 10.1215/10642684-6957940.

Ruberg, B. and A. Phillips. (2018). “Not Gay as in Happy: Queer Resistance and Video Games (Introduction).” Game Studies 18(3). https://gamestudies.org/1803/articles/phillips_ruberg

Serrano, Y. V. (2023). “Imagining Latin America: Indigeneity, Erasure and Tropicalist Neocolonialism in Shadow of the Tomb Raider.” Game Studies 23(2). https://gamestudies.org/2303/articles/villahermosaserrano

Schalk, S. (2018). Bodyminds Reimagined: (Dis)ability, Race and Gender in Black Women’s Speculative Fiction. Duke University Press.

Shaw, A., E. Lauteria, H. Yang, C. Persaud, and A. Cole. (2019). “Counting Queerness in Games: Trends in LGBTQ Digital Game Representation, 1985-2005.” International Journal of Communication 13. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/9754

Thach, H. (2021). “A Cross-Game Look at Transgender Representation in Video Games.” Press Start 7(1), 19-44. https://press-start.gla.ac.uk/index.php/press-start/article/view/187

Worst Girl Games. 2018. Heaven Will Be Mine [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game, published by Pillowfight Games.