Invitation to Party: MMORPG Heroism and the Metafictional Horrors of Social Interaction in Final Fantasy XIV

by Kevin WongAbstract

MMORPGs offer a live environment for perceiving how the passage of time, oral history, fan discourse and paratext are interwoven into the narrative fabric of their persistent social worlds. Beyond seeking to expand the methodological scope of “narrative” to encompass these emergent, player-driven forms of storytelling, this article critically reflects on the point of narrative within MMORPGs. It engages the question: how might the genre transcend its well-entrenched formulaic narrative scaffold -- one fixated on heroic individualism -- to facilitate new models and possibilities for social play? To this end, this article takes Final Fantasy XIV (Square Enix, 2013) as a case study for analyzing the critical and narrative possibilities unique to MMORPGs, given the genre’s extended time frame and distinctive focus on player-to-player sociality. It does so by tracing the diegetic arc, development history and player reception of the Tam-Tara Deepcroft questline -- the game’s most distinctive horror story. Even over a decade after its release, this low-level questline manages to maintain a hauntological relevance, preserved as it is within a live communal discourse.

Keywords: MMORPG, Final Fantasy, heroism, horror, NPCs, metafiction, time, genre, oral history, social engineering

Introduction

The critically acclaimed MMORPG Final Fantasy XIV confronts players early on with a multi-part narrative about the Tam-Tara Deepcroft, an underground crypt and one of the first dungeons that players encounter as they progress through the game’s main story quest. Every new player is led to witness a series of accidents and unsettling developments that befall an adventuring party of NPCs at the site of this dungeon -- the beginnings of an inset horror story which gestures knowingly at the sociality of its MMORPG frame. The tale’s premise, a woman driven to madness and forbidden magic following the untimely death of her lover, is hardly groundbreaking in itself. Yet, this timeworn trope of necromantic experimentation finds new life as the scaffold for the game’s more intriguing experiments: with genre, temporality, metafiction, heroism, oral history and social engineering. The questline’s unexpected incorporation of traditional horror elements into the world of Final Fantasy XIV has rightfully earned it the status of the game’s most distinctive horror story, and with it, some degree of hauntological continuity.

In this article, I trace the diegetic arc, development history and player reception of this tale -- elements that intertwine to produce a complex, evolving narrative. Even over a decade after its release, the relevance of this low-level questline is preserved within the cultural memory of the game’s community via a live ongoing discourse. The horror and lasting notoriety of this narrative arc further works to amplify its deconstruction of the genre’s deeply entrenched conventionalism and heroic ideological foundations, which the game articulates by subverting core gameplay concepts like death, time, victory and reputation. By integrating its manifold objectives into a single arc, the Tam-Tara Deepcroft questline represents a truly multi-pronged tutorial to the MMORPG. On its surface, it appears to merely teach new players to battle their way through your standard MMORPG dungeon, but it also encodes more subliminal instructions: namely, how to interact meaningfully with other players in the world, and even how to question the genre’s own mechanistic formulations of what it means to play as a hero.

Through detailed coverage of a single storyline and its reception across the life of a prominent MMORPG, I observe how moments of narrative subversion are processed at the level of the collective. By emphasizing this shared processing, this article strives to unpack the rich but underexplored potential of narrative in MMORPGs: fixated as it tends to be on establishing the player’s heroic individualism, narrative often appears incidental to the genre’s core of player-to-player interaction. Instead, by taking a longer temporal view to what narrative can accomplish as it is collectively interpreted, discussed, debated, streamed and shared over time, developers may be able to test its bounds as a device for framing and facilitating new possibilities for social play.

A Retrospective on MMORPG Scholarship

Some time has passed since the considerable wave of MMORPG research that saw entire edited volumes dedicated to individual MMORPGs like World of Warcraft (Blizzard Entertainment, 2004) and Lord of the Rings Online (Standing Stone Games, 2007) (Corneliussen and Rettberg, 2008; Cuddy and Nordlinger, 2009; Krzywinska et al., 2011). While the MMORPG is hardly as prominent a genre today as it once was -- and might even be considered “stagnant” since its most popular titles have remained largely unchanged for the past decade -- the genre remains very much alive in demographic, cultural and commercial terms (Square Enix, 2024) [1]. At this belated juncture, a fresh look at what is now a fully matured gaming genre might offer new insights into how its specific modes of play and narrative exposition have transformed over its extended development history.

Back in 2011, the editors of Ringbearers were already observing the undeniable entrenchment of the genre’s many quirks and design patterns: “We started wanting to know what conventions are becoming established in the context of the MMORPG, asking where these conventions come from and what divergences arise” (Krzywinska et al., 2011, p. 4). Final Fantasy XIV, a relative latecomer to the MMORPG genre owing to the Japanese game industry’s delayed entry into MMO development (Huber, 2022, p. 256), offers a prominent site for examining the further crystallization of the genre’s conventions. Following a disastrous initial launch in 2010, the game has, since its major overhaul and relaunch in 2013 as Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn, grown steadily in population. Today, it now consistently ranks high among the most popular MMORPGs in the world. This late debut, at a moment when a distinct MMORPG genre identity had already formed, has afforded the game ample opportunity for experimenting with generic self-awareness -- the very sort which, as Bradley Fest puts it, marks the growth of video games as an artistic medium:

If anything, the increasing presence of self-reflexivity in video games should be read as a sign of their aesthetic maturation. Creators are asking important questions about what video games can do and about what they can do with video games, and this has resulted in a flourishing of compelling and successful experimentation. (2016, p. 5)

From this perspective of “aesthetic maturation,” there are new prospects in following the development of MMORPGs, especially latecomers to the genre like Final Fantasy XIV as well as the many other games that have since been released and those still being developed today.

In recent years, Final Fantasy XIV has seen growing amounts of scholarly interest on wide-ranging topics that include localization (Vichot, 2024), allegory (Huber, 2022), roleplaying (Tate, 2019), hauntology (Appignani et al., 2015), copyright (Ritthamel, 2022) and more. Among these, William Huber’s macroscopic, structuralist reading of Final Fantasy XIV’s sprawling decade-long narrative has honed in on the game’s rhetorical and allegorical elements, which it manages to produce even from within the tight generic bounds of an MMORPG:

The MMORPG as a format produces a structured experience to its players that conditions its rhetorical and textual elements. At the same time, that format is itself a rhetoric: the activities of playing any MMORPG are such that they resemble each other to a greater extent than they vary from each other, constraining the polemical force of the content. (2022, p. 260)

Huber’s reading has argued for the game’s self-awareness at the broader level of its metanarrative. This article presents a complementary close reading that studies the game’s metafictive engagements through detailed examination of a single narrative arc.

Locating Narrative across Game, Paratext and Fan Discourse

Earlier scholarship on MMORPGs emphasized the emergent sociality that lay at the heart of MMORPGs (Taylor, 2006, p. 38-52; Corneliussen and Rettberg, 2008, p. 6). In the years since, the omnipresence of communication platforms like Discord, the growth of live streaming on Twitch and YouTube, and the rise of player communities around MMORPG streamers have extended and dispersed the in-world sociality of MMORPGs across these other social platforms (Jackson, 2024; Morris, 2023). The changing nature of sociality has likewise altered the way players engage with MMORPG narratives, which have always been read, discussed and debated as part of the genre’s social praxis (Calleja, 2011; Klastrup and Tosca, 2011). Accordingly, an up-to-date analysis of an MMORPG’s narrative cannot be restricted solely to how it unfolds in-game.

In this regard, transmedia and worldbuilding approaches offer a productive methodological foothold. They address the multi-sited quality to MMORPG storytelling, which seeks every so often to exceed the bounds of their in-game narration (Boni, 2017; Calleja, 2011). Scholars like Rhea Vichot have found this transmedia approach generative in understanding Final Fantasy XIV’s extensive lore and the dispersed articulation of its worldbuilding across “paratexts such as official websites, published books, forums, live streams, and live appearances” (2024, p. 49). Taking the game’s narrative in this more expansive sense, my analysis of the Tam-Tara Deepcroft arc attends also to its player reception as captured through live streams, forum posts, content creation, blog reflections, wiki pages and uploaded playthroughs. By locating narrative across a wide range of fan-produced sources, I simultaneously build upon what Mortensen and Jørgensen have coined a “player-response approach” (2020, p. 98), which advocates moving beyond the researcher’s own subjective experiences with a game and attaching analytical value to the experiences and interpretations of other players. Going further, I take the reception of this episode not simply as a collection of discrete reflections and experiences by individual players, but as instantiations of a wider cultural discourse that circulates and haunts the game’s community [2].

The Social Frame of MMORPG Metafiction

Much like having a favorite flavor of ice cream, players tend to develop preferences for specific game genres. Long-term enjoyers of the genre are therefore likely to have experienced several different MMORPGs over time, while growing familiar with the patterns that emerge between these games (Taylor, 2006, p. 77). The same can be said of developers as well: given their particularly time-consuming format and distinctiveness within the gaming market, MMORPGs are often designed for -- and, in fact, by -- long-term enthusiasts of the genre [3]. With both players and developers fluent in the established generic conventions of MMORPG (Bartle, 2011, p. 165) -- thereby sharing a common language -- the opportunity arises for developers to toy with players’ expectations as they pertain to the genre’s conventions. These moments of generic subversion can embed themselves within the gameplay, systems or narrative of an MMORPG as forms of coded speech and inside jokes between players and developers.

My reading therefore leans on the potential that MMORPGs have for metafiction -- which I take as an instance where a work exhibits self-awareness about the contexts of its own production, distribution and consumption. Metafiction, however, is hardly a new concept and has already been extensively applied to the analysis of game narratives (Fest, 2016, p. 3) and the act of gaming more broadly (Boluk and Lemieux, 2017, p. 2). In the context of analyzing MMORPG narratives, however, scholars have only rarely touched upon the topic (Huber, 2022, p. 270-271). Developing and maintaining an MMORPG (as opposed to a single-player title) comes with a set of unique technical and design challenges, which tends to limit the possible scope for narrative metafictionality -- or, at the very least, relegates it far down the developers’ list of priorities. After all, for a moment to count as metafictional within the distinct context of an MMORPG and not just any video game, it should be self-referential about the player-to-player sociality that defines the genre.

Although complicated to pull off, metafiction, when deployed thoughtfully and sparingly, can enable MMORPGs to realize their potential for social criticism. Game scholars have long argued against conceptions of a real/virtual divide, demanding that an accurate ontology of video games must recognize them as a continuous, mediating interface between fiction and reality (Taylor, 2006; Lehdonvirta, 2010; Welsh, 2016). Given that the social premise of the genre inherently grounds whatever happens within the game’s fictional world in the realities of player-to-player interaction, metafictional moments in MMORPGs are especially well-positioned to comment critically on our social gaming practices and the perils (and prospects) of online sociality. The Tam-Tara Deepcroft questline, as I seek to demonstrate, offers an exemplary instance of this, causing it to stand out even within Final Fantasy XIV’s own internal worldbuilding as it subverts the genre’s social frame.

Tam-Tara Deepcroft: When NPCs take on a Dungeon

Final Fantasy XIV’s main story begins, as many games do, with the player-character working to establish their reputation as a capable adventurer. When the Adventurers’ Guild experiences a sudden boom in commissions, players find themselves in a race against other NPC adventurers to clear various dungeons of whatever threats lurk within. In the open world, in front of the game’s first explorable dungeon (a grotto called Sastasha), players come across a band of four NPCs -- a young cleric named Edda, the archer Liavinne, the mage Paiyo Reiyo and the warrior Avere who also happens to be Edda’s fiancé. Interacting with them reveals their intention of taking on the dungeon, even though Edda is shown to be flustered, panting and ill-prepared as the group’s healer (see Figure 1):

Figure 1. The party from left to right: Avere, Liavinne, Paiyo Reiyo, Edda.

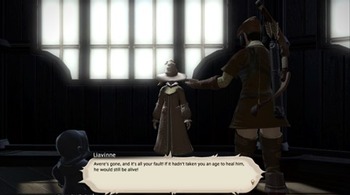

These adventurers next appear as players are fresh off their own victorious expedition through the Tam-Tara Deepcroft (the game’s second explorable dungeon), having defeated the demonic cult that resided within. As players return to deliver the news to their liaison in the Adventurer’s Guild, this cutscene ensues:

Mother Miounne: Sadly, death has become an ever more common occurrence within our fraternity of late. Times being what they are, the guild is constantly inundated with petitions, and we are hard-pressed to find enough hands to deal with them all. While this means no shortage of work for able souls such as yourself, it also provides ample opportunity for the inexperienced to overreach themselves -- with predictable consequences. Ah... as if to illustrate the point...

[Cutscene pans to a group of adventurers arguing]

Liavinne: Avere’s gone, and it’s all your fault! If it hadn’t taken you an age to heal him, he would still be alive!

Edda:B-But I tried! He bolted out of range before I could finish the spell! He shouldn’t have been so hard-pressed in the first place… We should’ve done more to lighten his burden…

Paiyo Reiyo: Bah! To the hells with this pathetic excuse for a party! I’m leaving, and it’d be too soon if I never see your faces again! Good-bye, and good riddance!

Liavinne: I’m leaving as well. I doubt this comes as any surprise, but I never liked you [Edda]. I only suffered you for your healing, but you couldn’t even do that one thing right. Cruel though this may sound, you brought this upon yourself.

Oh, and by way of some parting advice… get rid of Avere’s head! Bury it, cremate it, do whatever the hells you like with it -- but for gods’ sakes, stop carrying it around! It’s… it’s just… just get rid of it, all right!?

Edda: W-Wait! Don’t leave me alone! Please!I’m so sorry, Avere… Please forgive me…

Figure 2. Edda is blamed in the aftermath.

Witnessing only the aftermath of the group’s failed offscreen expedition, players are positioned as silent bystanders to this argument between its surviving members. Visually, the cutscene hones in on the tragedy (Figure 2): Avere is nowhere to be seen, Edda is griefstricken, while Liavinne and Paiyo Reiyo heap abuse on her. Blamed for her slow healing, poor Edda faces what Lisbeth Klastrup observes as “the social death penalty” that MMORPG players should they mistakes cause their death or those of others (2008, p. 158). Klastrup’s survey of the most common categories of player-submitted death stories involve “unsuccessful group play or personal blunders” (2008, p. 162) -- an archetypal MMORPG type-situation that the game reenacts here with Edda’s party.

The NPCs’ dialogue is peppered with explicitly self-referential gaming language, organically inserted into conversation in coherence with the world’s diegetic logic and spoken jargon. “Healing,” a mechanic especially relevant in MMORPG dungeon, is the topic of contention, while the group’s dynamics conform to what is often referred to as the MMO “holy trinity” -- a game design philosophy that structures and balances combat around three main roles: tanking, healing and dealing damage. The ubiquity of the holy trinity within MMORPGs has been tied to developers’ attempts to foster sociality and co-dependence between players at the core level of gameplay (Brown and Krzywinska, 2011, p. 39-41; Klastrup, 2008, p. 148). In the cutscene, Edda’s protestations evoke the MMORPG holy trinity as well as the internal specificity of Final Fantasy XIV’s combat mechanics, which requires the target of a spell to remain within its range until the spell is fully cast for it to work. Players of the game are expected to be intimately familiar with the frustration of having a target leave the range of their spell just as it is about to be cast and therefore be clued in on the joke. Such references take on an overtly metafictional valence by gesturing to the embodied knowledge which players are meant to accrue organically from existing and participating in the world. Metafiction works here by collapsing the game’s two narrative layers -- its scripted narrative, and the emergent narrative of users’ live play experiences (Calleja, 2011, p. 96, 106; Appignani et al., 2015, p. 42).

The trend continues with a reference to the MMORPG genre’s structured social gameplay: Paiyo Reiyo’s denunciation and subsequent decision to leave the “party” -- the term used in-game for player-constituted groups sized appropriately to take on dungeons and other expeditions. The language of in-game social systems -- which players learn and encounter while navigating the game’s user interface -- bleeds over into NPC dialogue, blurring the boundaries between the quest’s scripted NPC-to-NPC sociality and the structured player-to-player interaction that takes place outside of this narrative arc.

Beyond referencing internal gameplay structures, the party’s dialogue evokes a plethora of implied and encoded references to the broader social discourses surrounding Final Fantasy XIV’s dungeon gameplay (and which apply to the MMORPG genre at large) (Boluk & Lemieux, 2017). These often take the form of relatable gameplay experiences or observations that circulate on social platforms like Twitch, Discord, Reddit, the official forums or in-game when discussing the game with members of one’s “Free Company” (the game’s equivalent of a guild). For instance, Edda’s description of Avere conjures for players the widely-maligned archetype of the reckless tank who foolishly charges ahead, drawing the attention of more enemies than the party can manage. Liavinne’s accusations cast Edda as an archetypal incompetent healer, slow with her healing and protection spells, while evoking also the larger social tendency of blaming healers when things go south. Paiyo Reiyo’s spiteful departure likewise brings to mind the familiar notion of “rage-quitting” after a failed attempt at progressing through a dungeon. The constant barrage of metafictional MMORPG language and discourses tethers the player into a network of situational recognition -- connecting them simultaneously to their own character, to the NPCs placed into the circumstances that players likewise face during their gameplay sessions, and to their fellow players for whom these NPCs serve as allegorical stand-ins.

Tam-Tara Deepcroft (Hard): “Horror in my Fantasy MMORPG!?”

The Tam-Tara Deepcroft was initially released with the Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn relaunch on 27 August 2013. Almost a full year later, on 8 July 2014, the release of Patch 2.3 continued the story of this unfortunate band of adventurers. In town, players bump into an old acquaintance, Paiyo Reiyo, who has been adventuring solo since that fateful day. He is troubled by a wedding invitation from Edda, which he would have found heartening if not for the deceased Avere being listed as the groom, and the Tam-Tara Deepcroft the venue. The invitation also promises Liavinne’s attendance, who met her unfortunate demise elsewhere during the game’s main storyline. Accompanying Paiyo Reiyo, players find Liavinne’s grave disturbed and body missing. With this confirmation that something sinister is afoot, Paiyo Reiyo requests that players accompany him to the Tam-Tara Deepcroft to investigate these haunting developments -- this time, by venturing through dungeon on “Hard” difficulty.

Throughout the revamped dungeon, players find Edda’s scattered journal entries that detail her gradual descent into madness. The hostile monsters that populate the dungeon include a variety of demons clad in wedding attire, as well as mutilated body parts and headless abominations -- the unnatural results of Edda’s necromantic experimentation. The first boss battle has players confronting a reanimated Liavinne forced to usher for the wedding, while the second has us rescuing Paiyo Reiyo from a disturbing sacrificial ritual. At the end of the dungeon, a cutscene plays and the camera pans to Edda in the center of a ceremonial circle, caressing the giant floating disembodied head of Avere. With crazed eyes, she reveals that -- given our heroic stature -- we are her intended nuptial gift to Avere, meant to serve as his bodily host. In a bid for survival and not to have our bodies defiled, players are forced to confront the abomination in battle, as well as the once-innocent Edda who, far from her early days as a white mage, now wields potent dark magic against us (see Figure 3):

Figure 3. Edda and the reanimated head of “Avere.”

Across its transmedia iterations in oral folklore, literary fiction, cinema, or video games, what is now recognized as “horror” can be understood expansively, as James Twitchell suggests, as “a collection of motifs in a usually predictable sequence that gives us a specific physiological effect” (1985, p. 8). Responding to the interactive potential that games have in bringing horror closer than ever to audiences, game scholars have adapted the principles from film studies and visual studies to the rich corpus of (primarily) survival horror video games, in dedicated volumes (Perron, 2009) and articles (Krzywinska, 2002; Perron, 2018; Christopher and Leusler, 2023).

On this second visit to the Tam-Tara Deepcroft, players are confronted with the game’s attempt at body horror, a subgenre of horror that is “not content to leave [the viewer] with vague, disembodied imaginings, but excitedly seek[s] to incise those imaginings in their very flesh” (Shaviro, 1993, p. 101). Players are forced to battle their way through a swarm of animate mutilated viscera, as the depths of Edda’s descent into madness and necromancy are gradually unveiled. Even closer to home, the player-character (and by extension, players themselves) gets personally implicated in this body horror, for it is their body that Edda intends to despoil and make the host for Avere’s reanimated head. While MMORPG players frequently confront death at the hands of in-game enemies -- and often with a corporeal focus in the staging of their avatar’s death (Klastrup, 2008, p. 156) -- bodily defilement is another matter entirely. Imagining the vivid mutilation of one’s character, the virtual avatar that players presumably have some investment in, is meant to be somewhat disturbing (see Figure 4):

Figure 4. Dungeon enemies comprise mutilated body parts -- the results of Edda’s necromantic experimentation.

Integrated into this overarching frame of body horror are distinct elements of Gothic horror, which delights in the overturning of normative structures and institutions like family, society, law and love (Taylor, 2009, p. 49). The revelation of Edda’s fall from grace with the “twisted wedding” trope exemplifies the transgressiveness that defines the Gothic. At this wedding, various human institutions -- marriage, mortality and bodily sanctity -- all undergo desecration. Rather than bury Avere’s head in the aftermath of his death, despair drives Edda to reanimate and marry it. The wedding ceremony is transformed into a convenient occasion for ritual sacrifice, with attendees like Paiyo Reiyo and the player-character intended as sacrificial offerings. The presence of demons and monsters as wedding celebrants likewise serves to “explore and dramatise the borderlines between various fundamental categories that are commonly used to produce identity and order in our cultures and societies” (Mäyrä, 2011, p. 118). And in place of a wedding dress, Edda dons the iconic white cleric robes (a subversive occasion for showing off the staple outfit of the MMORPG healer and the Final Fantasy franchise’s playable “White Mage” class).

Edda’s narrative transformation from innocent cleric to unhinged practitioner of dark magic conveys itself also through gameplay. During the boss battle against “Avere” and Edda, a doll-like voice -- a blend of laughter and crying; a standard Gothic motif (van Elferen, 2015, p. 234) -- resounds throughout the dungeon as an auditory preamble to a crucial combat mechanic. Edda charges up a spell titled “Red Wedding” to unleash an explosive nova of blood against players. As she channels the spell, a swarm of reanimated corpses named “Grooms-to-be” crawl toward her in a grotesque consummation ritual -- if players fail to defeat them before they reach Edda, her spell is amplified to lethal levels (Figure 5). Additionally, the in-game cutscene that plays after the dungeon incorporates borrowings from horror cinema such as jump scares and close-ups, bringing the horror closer toward the real player behind the screen (Figure 6):

Figure 5. Reanimated corpses called “Grooms-to-be” crawl toward Edda as she channels a destructive spell titled “Red Wedding” (screenshot taken from The Scrub, 2023).

Figure 6. A haunting moment in the quest’s closing cutscene after defeating Edda and Avere: a terrified Paiyo Reiyo glimpses a silhouette of Edda, as the camera zooms in on her [4].

Perhaps the most jarring element of this horror story is its unexpectedness [5], set as it is within the predominantly cheerful world of Final Fantasy XIV where players could theoretically spend all their game time just socializing, crafting, role-playing or decorating their homes. While there is certainly plenty of dark fantasy to be found -- with heavier themes of war, death, empire, religion, loss and sacrifice all being central to the game’s main storyline -- the game never ventures full-on into horror territory as it does with the Tam-Tara Deepcroft. Even so, this questline is careful to avoid going overboard with its use of gore or horror, nor does it strive to produce the same sort of fear we might expect from survival horror games. After all, unlike horror enjoyers who specifically seek out those thrills, MMORPG players do not often sign up to be frightened out of their seats.

As a result, making horror effective within the limits of an MMORPG can be tricky business. Analyzing Requiem: Memento Mori (Gravity Interactive, 2008), a rare horror-themed MMORPG, Geraci, Recine and Fox articulate how a delicate nuance can be achieved: “A horror becomes merely action adventure once the monsters are visible and present; it is their presence offscreen, the threat of their appearance, and the dangers they imply that produce a true sense of horror” (2016, p. 225). Generating horror through implication, as suggested, is something the Tam-Tara Deepcroft arc does rather well. Leaning into a unique brand of metafictional MMORPG horror, the narrative depicts grotesque consequences as a form of undivine retribution for antisocial behavior within the context of a dungeon party. Avere, Liavinne and Paiyo Reiyo -- the former members of Edda’s crew -- are all subjected to varying degrees of bodily defilement (Figure 7). Given the situational overlay that constructs this band of NPCs as a metafictional gloss on player-formed parties, the narrative invites players to identify themselves as the implied recipients of these haunting consequences should they misbehave online.

Figure 7. Disembodied corpses -- “Best Men” and “Bridesmaids” -- swarm the players as they are forced to defeat the reanimated Liavinne as a mini-boss in the dungeon (screenshot taken from 4 Player Squad Gaming, 2021).

Gaming has always had to confront the widely-covered issue of toxicity and transgressive play (Paul, 2018; Boudreau, 2018; Mortensen and Jørgensen, 2020). Christopher Paul attributes toxicity in gaming culture to an insidious rhetoric of meritocracy, even singling out MMORPGs like World of Warcraft as prime sites for observing this rhetoric in action. He argues that the genre’s efficiency-obsessed systems are to blame, as they encourage players to adopt dehumanizing metrics for evaluating other players, fixated as they are on power levels and risk of time wasted in the event of failure (Paul, 2018, p. 111-114). In the depicted social breakdown of Edda’s party, we find a narrativized engagement with player toxicity which can supplement more heavy-handed forms of social regulation (a topic to be discussed in greater detail in the penultimate section).

The later quests have us journeying with Paiyo Reiyo, the party’s only surviving member, left haunted by the fate of his companions. Taken as instructive allegory, the Tam-Tara Deepcroft questline ultimately follows his journey of reflection, closure and maturation:

Paiyo Reiyo: “I will try to explain. To the rest of us, our little party of four was but a means to riches and glory -- such things as adventurers seek. But to Edda, it was her life… She blamed herself for Avere’s death, and to our shame, we agreed with her -- though we knew full well we were all to blame. And then we left her where she stood with her fiance’s head for company… Ack! How could we have been so heartless!? Small wonder if the poor girl has been driven from her wits!But what’s done is done. All we can do is admit to our mistakes and make amends as best we can.

Regretting the part he played in these developments, Paiyo Reiyo comes around to the idea that Edda’s ex-party members, himself included, were not simply passive victims of horror, but collectively complicit in the party’s tragedy. His remorse teases the open question of what might have been, if only he and Liavinne had been better companions to Edda and responded instead with more empathy. By journey’s end, Paiyo Reiyo has taken these haunting lessons to heart. Even at the microcosmic level of a fictional inset MMORPG narrative, his growth speaks to the possibilities of rehabilitation.

Using Horror to Play Critically with the Heroic Fantasy

Generally, MMORPGs tend to insert players into the very center of a persistent universe to take on the part of its infallible and steadfast hero -- an unashamed embrace of “the chosen one” trope. This heroic situatedness of the player-character is usually taken for granted by both players and developers. It now represents the genre’s go-to strategy for connecting the player-character to larger events in the world’s evolving narrative. Within game studies, however, heroism has been a steady topic of critical examination -- and its entrenchment as the default paradigm in games has been tied to hegemonic masculinity, imperialism, settler-colonialism, authoritarianism and other “savior fantasies” (Jennings, 2022, p. 320-321; Bond & Christensen, 2021). I argue that the Tam-Tara Deepcroft arc subverts the heroic premise of its MMORPG frame by exploiting its horror and metafictional elements to enact a form of “critical play,” which is when

… [designers] manipulate elements common to games -- representation systems and styles, rules of progress, codes of conduct, context of reception, winning and losing paradigms, ways of interacting in a game -- for they are the material properties of games, much like marble and chisel or pen and ink bring with them their own intended possibilities, limitations, and conventions. (Flanagan, 2009, p. 4)

This section examines how the recounted narrative critically interacts with the game’s systems, mechanics and conventions to destabilize the genre’s construction of heroism, one pillar at a time. I aim to show how foundational concepts like death, victory, achievement and time are turned on their head as the story deploys pointed breaks from the game’s internal conventions to render uncomfortable its traditional boss-battling, victorious-hero model of conflict resolution. At the same time, the narrative integrates the passage of embodied time as a gesture toward the player-character’s negligence and passive complicity in the tragedy.

Boss Down. Duty Complete?

Games work in accordance with recognizable patterns and clear objectives. Like most games, Final Fantasy XIV has its own conventions that it internally subscribes to, thus generating a set of player expectations as they navigate within the world. One prime example is the catchy victory fanfare that plays upon the completion of a dungeon (Soken, 2014) as player avatars cheer happily -- a nifty little audiovisual reward for successful gameplay. As players vanquish the dungeon’s final boss, the demonic reanimated head of Avere, a victory cutscene plays: Edda screams in agony, reliving once more the trauma of watching him die in front of her. In shock, she trips backward off the ledge of the ceremonial circle, falling into the abyss. Congratulations! -- You have defeated the dungeon’s final boss, and the game’s victory fanfare plays as usual; as it must. But for the first time in the game, it is not accompanied by the hero’s joyful cheer which players have been hardwired to expect [6]. Instead, the player’s avatar bows their head and shuts their eyes, an expression of pain at the unhappy culmination of a tragic story (Figure 8). As the victory jingle plays, “Duty Complete” flashes in gold across the screen (Figure 9), but your character knows better. In their true heroic duty, they had failed: not in vanquishing the final boss, but in saving a grieving maiden at the height of her anguish -- by perhaps forgetting about her when she needed them most. In choosing this one calculated moment to subvert player expectations, the game exposes the victory as pyrrhic, the fanfare hollow.

Figure 8. Camera closes in on player-character’s pained expression, a stark departure from the joyous cheer that the player-character otherwise gives at the end of dungeons.

Figure 9. “Duty Complete?”

The disjunct generated between these cheerful established conventions and the sombre gravity of the situation captures the episode’s critical play with heroism. Final Fantasy XIV’s systems prime players to anticipate the gameplay conventions that signal yet another heroic victory -- “Duty Complete” sign, jingle and joyous cheer. The game only partially delivers, quite literally robbing players of their character’s joy. During this moment, as the game bends inward on its own established systems, players are made to linger on the haunting events that just transpired and their complicity in it. We are invited to question the numbing apathy encoded into an MMORPG’s systems, and search within ourselves for the emotional nuance that has been swept under by the genre’s structured heroism.

Immortal Heroes and their Fragile NPC Stunt Doubles

Within MMORPGs, players tend to be keenly aware that their characters are never at any real risk of being killed off, since they can be revived as often as needed [7]. This capacity for infinite revival is largely a practical function of the genre: MMORPGs are games in which players are expected to invest significant amounts of time, emotion, and even money into empowering and personalizing their characters. The concept of permanent death goes against the logic of this intended continuity.

Yet, since death is “part of the potential narrative architecture of the world” (Klastrup, 2008, p. 153), this de facto immortality has crucial implications for narrative construction. Designers tend to rely on players’ suspension of disbelief, purposefully overlooking how their immortality factors into an MMORPG’s game’s narrative. Otherwise, acknowledging it bears the risk of trivializing any danger that the player might face throughout the game (Appignani et al., 2015, p. 44). Final Fantasy XIV, however, has attempted to account for the player-character’s capacity for infinite revival through a revelation early in the game’s main story. Having chosen the player-character as her champion, the goddess Hydaelyn expends her energy specifically to revive them whenever they die. As her power is limited, she cannot offer the same privilege to everyone else. While intriguing, this narrativized explanation for player immortality nonetheless remains a thin façade for the power fantasy that has been entrenched as a non-negotiable premise of the genre. Players expect to be set up as the ever-present, heroic deus ex machina to every problem, big or small, faced by the scripted inhabitants of the game’s world.

Since players are effectively precluded from meaningfully experiencing the death of their characters, narrative construction within the genre is therefore forced to refocus players’ anxieties around death away from their own to those of others -- NPC friends, allies or strangers that players encounter in-game. Within existing scholarship on MMORPGs, player-centered perspectives on avatar death have drawn their fair share of attention (Castronova, 2005, p. 114; Appignani et al., 2015; Klastrup, 2008, p. 143-144; 163). My analysis redirects some of this attention toward the technical and narrative affordances of MMORPGs by situating player immortality (i.e. non-death) in dialogue with the relative conspicuity of NPC mortality. René Glas, studying the numerous henchmen and goons that seemingly exist solely for players to defeat en masse in the action-adventure genre, has shed some light on the importance of NPCs and the “generic adversaries” that populate our game worlds (2015). The conventions that have formed around how players are expected to interact with NPCs, Glas argues, have the potential to lead players “to moments of potential ludonarrative dissonance, problematic from an aesthetic and/or questionable from an ethical point of view” (2015, p. 46). Accordingly, we might consider how a similar reliance on NPCs to set up meaningful deaths within an MMORPG can lend itself to possible modes of critical play.

The Tam-Tara Deepcroft arc finds a clever workaround to its conundrum of player immortality: namely, by deploying a band of NPCs as unfortunate stunt doubles who, in lieu of the immortal hero, are cast as the required victims of horror and tragedy. In so doing, the narrative offers a pointed departure from the genre’s epic-heroic framework by exploring the grim parallel possibility of non-heroic individuals forced to confront a dangerous world structured around the abilities of immortal heroes (i.e. players). This move finds resonance with Marcus Schulzke’s postulation that, although MMORPGs may convincingly simulate utopias, they reach greater heights of aesthetic and critical potential when they lean into the dystopian -- especially when they manage to successfully “force players to become participants in the causal processes responsible for producing dystopia” (2014, p. 320, 331). As if on cue, the Tam-Tara Deepcroft arc goes out of its way to implicate us in its chain of events, with the genre’s critical play at its most explicit when Avere’s hero worship of the player-character is revealed to have inspired the party’s fateful undertaking:

Edda: His name was Avere, and he and I were to be wed in the spring. You may not remember him, but to say that he remembered you would be an understatement. He would sing your praises from dawn to dusk. He saw you for what you are, you see -- an adventurer’s adventurer -- and swore that he would be like you one day.

Edda’s slew of second-person references makes it exceedingly clear that we, the players, have been unknowingly complicit in the tragedy all along. The tales of our heroic exploits -- the ideologically-assumed foundations of the MMORPG power fantasy -- have driven others to follow recklessly in our footsteps. But without a crystal goddess of their own on retainer (as we have) and thus denied access to our privilege of infinite revival, these NPCs must confront mortality and its traumatic implications on our behalf. The resulting tragedy that befalls Edda and her party tackles the problem of player exceptionalism head on, and provides a bleak answer to the existential question: what would it be like to be ordinary in a world made for heroes? When an actual player tasked with healing performs poorly, their party dies, revives and tries again. The well-documented consequences of player failure are inconvenience, annoyance and potential toxicity (Castronova, 2005, p. 114; Appignani et al., 2015, p. 44; Klastrup, 2008, p. 146-147). When Edda fails in that same duty, her fiancé is gruesomely decapitated. She loses her lover, gets abandoned by her companions, goes mad and begins to bargain with death. By mirroring the dungeon-based gameplay experience of players, while imagining its tragic narrative possibilities, the Tam-Tara Deepcroft becomes a space of speculative fiction that forces players to check their immortal privilege.

Heroic Negligence and the Passage of MMORPG Time

MMORPGs are temporally complex creatures, designed as ongoing virtual worlds into which players may invest their time, emotion and money under an expectation of its continued existence. Having adopted this “games as a service” model, MMORPGs portion out their long-form narratives, delivering it piecemeal in the form of content updates. Guild Wars 2 (ArenaNet, 2012), for example, uses the descriptive phrase “Living World” to market its story updates, while Final Fantasy XIV communicates its content pipeline to players far in advance during regular developer livestreams titled “Letters from the Producer LIVE.” Those who study MMORPGs often find themselves having to confront the genre’s peculiar relationship to time. Laurent Di Filippo, analyzing the dynamic game systems that capture the passage of time -- character levels, the introduction of new areas and quests, seasonal events -- has construed MMORPGs as “locally realized worlds” that emerge in response to temporally situated gameplay (2017, p. 235-236). Huber has observed how an MMORPG’s “slow drip” of content “elongates the horizon of reading” (2022, p. 261), with some narrative threads finding their resolution only years later.

The Tam-Tara Deepcroft questline engages the unique temporality of its MMORPG frame to further immerse players in its metafictional horror, enacting the passage of embodied time through the gradual delivery of its narrative over three years of game development. As Perron observes, time has a particularly important function in the construction of ludic horror, especially when the player’s gameplay time and diegetic time fall into alignment (2018, p. 105). The dungeon initially released on 27 August 2013, concluding with the disbanding of Edda’s party. A year later, on 8 July 2014, Patch 2.3 brought players back to the Tam-Tara Deepcroft to crash Edda’s wedding. Two years later, on 7 Jun 2016, Patch 3.35 provide an ending to Edda’s tale with the release of a “Deep Dungeon” (a new gameplay mode where players fight their way through a hundred-floor dungeon) called Palace of the Dead. Edda, now clad entirely in black with a miniature version of Avere’s disembodied head perched on her shoulder, has fully embraced the necromantic life and appears as a boss on the dungeon’s 50th floor. Defeating her here commences a quest to release her spirit, allowing her to finally find peace. For those who played the game during those years, Edda’s disappearances and offscreen transformations align themselves with years of game development. As players waited for developers to deliver the next arc in her story, Edda was presumably living out her despair in solitude.

On another level -- particularly for those who played through the quests after 2016 -- the narrative enacts a secondary form of time lapse through the embodied gameplay of levelling. The narrative’s opening sequence takes place at level 15, but the player only revisits this story upon reaching level 50 and bumps into Paiyo Reiyo. In between, the player is kept busy elsewhere in the world, completing the main story quest, rescuing friends, exploring new lands or even just gathering herbs. Gaining 35 levels can take a significant amount of time: an organic and variable time lapse that can range anywhere from days to months depending on how active the player is. The quest’s level requirement makes this discursion non-optional, while representing the passage of diegetic time in which Edda is likely to have slipped entirely from the player-character’s mind. It is only much later, as the mystery unravels, that the player-character realizes, with horror, the gravity of Edda’s offscreen descent into madness that has taken place without their knowledge. Madness, after all, takes time. Enacted on two levels through the gradual nature of MMORPG development as well as the gameplay of levelling, the passage of embodied time draws the player into the horror by suggesting, almost, their fault as a negligent hero. As Edda wasted away in her grief, why did the player never think to check up on her? Perhaps more accurately, why weren’t they given an option to? MMORPG columnist Victor Barreiro addresses this quandary:

The question that comes to me, contrived as it may seem, is simple: if her connections with people and her mind were so fragile, would my interference long before completing Tam-Tara Deepcroft have helped to ease her pain?

The answer in the game is simple: they don’t want you to ask that question. You’re a silent protagonist, and even then, your actions are bound by the need to complete a storyline. There is no scenario, among the millions of people playing Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn, where Edda receives a thoughtful word or concern from others.

In the real world, however, I have that luxury to care. I’m lucky enough that a Reddit post, and a compelling, albeit a twisted, J-horror-like storyline could make me care about human beings more. (Barreiro, 2014)

As he points out, the game effectively leaves the player no alternative to being a negligent hero who leaves an evidently grieving soul to her own devices. The indignation that this lack of agency might generate for some players, as it does with Barreiro, offers one instance of the story’s metafictional and allegorical force, inviting players to reflect on what they would have done differently if they were in their character’s shoes. Reading Edda’s tale as an avoidable tragedy stemming from heroic negligence -- and therefore an instance of critical generic self-reflexivity -- aligns also with Roy’s call for greater attention to the quotidian aspects of MMORPG temporality and its tendency to be subsumed by our preoccupation with the heroic. Whether we help villagers douse fires or recover their lost sheep, these “everyday quests… allow us to develop a definition of the heroic that is independent of the gendered and violent cultural narrative of hypermasculinity” (Roy, 2015, p. 179). Through its steady current of generic subversion, the Tam-Tara Deepcroft questline invites players to consider alternative formulations of heroism which prioritize forms of care, nurture and maintenance -- and in so doing, assign value to the emotional, in addition to physical, wellbeing of those we rescue. Yet, it simultaneously highlights how the conventions of the MMORPG medium are what restrict our ability to act upon these alternative forms of heroism. Or perhaps even more provocatively, those same conventions demand our heroic negligence to feed the cyclical creation of new dungeon bosses, which players can then put down through more familiar, violent forms of resolution.

Fan interpretations like Barreiro’s help to actualize and uncover the narrative’s critical, self-reflexive meaning, which requires players to transcend its diegetic frame by roping in, for instance, their own embodied sense of time. To borrow an adage from my home discipline in the reception of Greco-Roman literature: “Meaning is always realized at the point of reception” (Martindale, 1993, p. 3). Charles Martindale’s oft-cited phrase is one of many discipline-specific articulations of the reader-response turn in literary criticism, which game studies scholars, too, have readily adapted (Mortensen and Jørgensen, 2020, p. 98). Other scholars working on MMORPGs have likewise observed the importance of active player and fan engagement with the game’s narrative. Klastrup and Tosca, studying Lord of the Rings Online, explains: “In an MMOG, fans not only revisit and recognise; they act, negotiate, collaborate with others and are even forced to argue for the value of their own interpretation of the transmedial world” (2011, p. 65). Fan interpretations have the potential to circulate widely, creating a paratextual ecosystem that supports, supplements and, in some sense, completes an MMORPG’s in-game lore. In addition to Barreiro’s, there have been countless other instances of community reflection and discourse specifically on Final Fantasy XIV’s Tam-Tara Deepcroft story -- emerging in varied forms such as playthroughs, video essays, reflection pieces and discussions on Reddit or the game’s official forums (MMOGames.com, 2016; Coldrun Gaming, 2018; Firestorm, 2019; ELHC, 2020; Albsterz Too, 2021; Audioshaman, 2021; JetStrim, 2021; 4 Player Squad Gaming, 2021; Nobbel87, 2022; Witchybop, 2022; OhJoSama, 2023; The Scrub, 2023; Oograth-in-the-Hat, 2023; Vaynshteyn, 2024). Some of these examples involve players sharing their unusual observations or affective experiences with the story, while others show fans debating the questline’s underlying messaging. Taken altogether, these myriad forms of social engagement demonstrate how narrative meaning within an MMORPG is realized through a collective process of interpretation, documentation, speculation and commiseration.

Scaring Players into Playing Nice: MMORPG Narrative as Social Engineering

Having discussed the diffusion of this questline into the broader cultural discourse throughout the game’s community, this seems a fitting juncture for examining the potential of narrative in effecting actionable social change within its MMORPG frame. Using the player reception of the Tam-Tara Deepcroft questline as a case study, this section directs our attention to how narrative construction can operate as part of a broader strategy for behavioral instruction, community building and, indeed, social engineering.

Intended or otherwise, developers of online worlds inevitably find themselves in the role of social engineers. Thomas Apperley has suggested that the digitization of RPGs has seen them move beyond their tabletop and pen-and-paper roots, transforming from “a collectively produced fantasy” towards “an official fantasy world with strictly defined parameters” (2006, p. 17). MMORPGs, he argues, go even further, with the role of dungeon master, the DM, “replaced by the programmed environment and augmented by company employees who monitor the interactions between players” (2006, p. 18). As developers tinker with their social vision for the world, the game’s in-built systems and affordances represent their primary tools of choice. Scholars have extensively analyzed how an MMORPG’s wide array of game systems (combat, parties, guilds, chat, trading, PvP, inns, roleplay, itemization, etc.) function as forms of “structured social complexity” (Castronova, 2005, p. 105), curated “possibility spaces for emotionally meaningful social interaction” (Isbister, 2016, p. 53), and signposts that “direct players towards an understanding of what community means within the framework of the game and what is expected of more engaged players” (MacCallum-Stewart, 2014, p. 47). An MMORPG’s social environment both emerges from and develops around a game’s systems, requiring that we pay attention to the affordances encoded within them.

Quests are no exception -- they belong to this toolkit for social engineering and can be used to actualize developers’ visions for their game’s community. Focused on the perspective of the individual player, Jill Rettberg has analyzed how quests in World of Warcraft function as “rhetorical figures of deferral and repetition” -- designed to gesture ever towards their promise of endless content (2008, p. 182). She ends her chapter with the speculative question: “[W]ill we find that repetition and deferral are the primary rhetorical figures for all MMOGs?” (Rettberg, 2008, p. 182). In the more narrative-focused world of Final Fantasy XIV, the Tam-Tara Deepcroft arc experiments with some of the other rhetorical possibilities that quests can represent -- transcending the ritualized patterns of play suggested by Rettberg to serve as allegorical frameworks for the genre’s player-to-player interaction.

Given the questline’s early placement in the game (from level 15), situated within its narrativized introduction of dungeons as a core gameplay system, Edda’s cautionary tale functions as a programmatic introduction to both dungeons and player interaction. By depicting the tragic misadventures of a party of NPCs at the site of this dungeon -- a metafictional gloss on player-formed dungeon groups -- the narrative engages its audience on the player-to-player sociality that extends just beyond the game’s diegetic universe. Horror, in turn, wraps itself around this metafictional premise by constructing a dark tale that imagines visceral consequences for antisocial online behavior. Read as social allegory, the disharmony that characterizes Edda’s party becomes deeply instructive -- a demonstration of how exactly not to behave in game. In this way, the narrative subtly shores up an internal code of conduct for the game’s online community, straddling fictional storytelling in a virtual world and the realities of social gameplay. For the players who find themselves in alignment with its message, the story reaffirms the role of patience, kindness and empathy in online interaction. For those who do not, Paiyo Reiyo’s character development suggests that it is never too late to change your mind:

Paiyo Reiyo: Words cannot express my gratitude, [player-character]. You’ve seen me through much, and shown me what it means to be an adventurer. Our party lacked unity, and paid dearly for it. No one should suffer as they did, and I will do all I can to see other would-be heroes do not succumb to such a fate.

Given this didactic quality to the questline, we might consider how the moral messaging of in-game narratives can dovetail with more concrete and heavy-handed approaches to managing player sociality. Scholars have observed how some developers “take an active ethical stance toward cultivating certain kinds of social situations and desired outcomes for players that reflect their values” (Isbister, 2016, p. 64), and “project a certain ethos which helps to keep players in their delineated play types and encourage an idea of community as encompassing them” (MacCallum-Stewart, 2014, p. 48). Unlike games PvP-centered MMORPGS where a competitive ethos and forms of “dark play” are considered part and parcel of the game (Carter, 2015), the developers of Final Fantasy XIV are intentional about cultivating a social and collaborative environment for its players. Accordingly, Square Enix takes a top-down stance against player toxicity, which they substantivize with a diligently enforced user agreement and express prohibitions on antisocial behavior (Square Enix, 2019; 2021).

The efficacy of these approaches, however, does not depend solely on the developers’ will and the elaborate finetuning of their game’s in-built social systems. It is also necessary to win over some degree of buy-in from players, as T. L. Taylor has observed:

… [T]here is an emerging tendency to try to retrofit complex social systems into tidy mechanical models, which leads to a preoccupation with creating worlds that can be constantly monitored, tuned, regulated, and controlled… Even without a formal ‘heavy hand,’ player communities still construct ideas about what is normal and what warrants stigma, they still deploy status and hierarchies, and they often self-regulate based on a kind of internal imagined dialogue with designers and corporations. [emphasis added] (2006, p. 158; 161)

This gradual seepage of an MMORPG’s official scripted ideology into forms of player self-regulation is a strategy that Square Enix works hard to enact in Final Fantasy XIV. There exists the general sentiment that the studio has managed to cultivate a positive relationship with its players (Ritthamel, 2022, p. 203; Hassall, 2022). This relationship is fostered by the developers’ attempts at maintaining open lines of communication through regular announcements on the official website and “Letters from the Producer LIVE” -- livestreams which run from anywhere between three and six hours long. Through these channels, the game’s producer Naoki Yoshida not only shares information about upcoming patches and updates, but vocally addresses issues around emergent player behavior, social trends and contentious issues like cheating (Naoki, 2023). In this sense, the studio’s approach to sociality blends elements from both a paternalistic, top-down model of behavioral policing and a more co-constructive and consultative process whereby players have a stake in designing the online world they wish to inhabit.

As this discussion has shown, attempting to situate the allegorical potential of narrative within the wider matrix of social policing and community building can be especially complex. Nonetheless, the Tam-Tara Deepcroft arc represents a fascinating point of convergence, with the game’s terms of service effectively written into a cautionary tale that self-reflexively gestures toward its own officially sanctioned model for online interaction.

Hauntingly Ever After: Ghost Sightings, Phasing and the Making of an Urban Legend

Despite having been wrapped up for quite some time, the Tam-Tara Deepcroft horror story continues to haunt the world of Final Fantasy XIV, inscribing itself into the oral history and collective memory of its players. To conceptualize the mechanics of this continuity, some guidance may perhaps be found in Derrida’s notion of hauntology. Describing how the past persists and shapes the social, cultural and political discourses of the present and future (Derrida, 1994), it has been used by scholars to understand the transhistorical aspects of ludic horror (Krobová et al. 2022, p. 2). Others have even brought the concept to bear on Final Fantasy XIV itself, applying it to the philosophical and experiential perspective of the individual player: namely, how players’ MMORPG avatars function as “digital repositories for the embodied self” (Appignani et al., 2015, p. 29). My invocation of the concept here operates in a somewhat more traditional sense, with the cultural memory of Edda’s tragedy taking on a sociospatial hauntology -- lingering on simultaneously across the game’s playable environment and within its live community discourse.

As players stroll through one of three main cities -- the game’s designated player hubs and safe havens -- there is an off-chance that they may find themselves face-to-face with a ghostly apparition of Edda (Figure 10):

Figure 10. There is a tiny chance, at night, for Edda’s ghost may appear in the game’s three main cities. Even when players catch a glimpse, the spirit fades hauntingly in and out of view.

The developer’s addition of Edda’s ghost into the game’s live environment is a clever touch, demonstrating a willingness to allow the narrative’s horror to step beyond the overly tidy frame of the standard MMORPG quest and its clearly delineated zones of impact. Almost contemporaneous with the release of the Tam-Tara Deepcroft (Hard), Runescape (Jagex, 2001) introduced a quest titled “Broken Home,” an isolated horror story of a somewhat similar vein, as part of the game’s 2014 Halloween update. Tackling the same challenge of incorporating traditional horror elements into an MMORPG space, “Broken Home” took the alternative approach of containing its horror: the quest, from acceptance to completion, takes place entirely within a purpose-built haunted mansion. Edda’s tale, although intertwined with the game’s narrativized introduction to three distinct playable dungeons, is designed to encroach upon the world beyond its designated spaces. The lingering presence of Edda’s ghost in the game’s communal spaces is a declaration of the arc’s refusal to become “just another quest” that players to complete before moving on with their lives. Instead, it seeks to animate discussion long into the MMORPG’s life.

The remarkable discursive afterlife of the Tam-Tara Deepcroft horror story can be traced, in part, to its clever use of phasing -- the game design practice of “editing the world according to the quest progression of a player-character” (Brown and Krzywinska, 2011, p. 33). Phasing is done primarily to maintain temporal and narrative coherence for each individual player, but it can be tricky to navigate within an MMORPG, since its many players progress through the game’s story and complete quests at vastly different paces. Often, developers resort to shuffling players into separate instanced zones where the NPCs relevant to their quests exist, alongside other awkward solutions that risk “unravel[ing] the temporal dimension of the epic” (Brown and Krzywinska, 2011, p. 33).

The developers of Final Fantasy XIV found a way to turn this potential problem of phasing into a valuable opportunity. Edda’s ghost is coded to appear only to players who have defeated her and Avere in the Tam-Tara Deepcroft on “Hard” difficulty, but who have not reached the final resolution of her story by defeating her once again in the Palace of the Dead, whereupon players receive a final quest to lay her spirit to rest once and for all. In other words, her ghost appears only to players with whom she still has unfinished business with. With players’ ability to see the ghost contingent on which of three distinct categories of quest progression they fall into, there is great irregularity in these ghost sightings across the player base and the world’s spatial environment. The resulting mystery around these sightings has fueled a timeless and emergent social discourse around the Tam-Tara Deepcroft questline. Every now and then, the subject is brought up once more as players, coming across Edda’s ghost for the first time or in a different unexpected location, report their respective ghost sightings on one of many available social channels like Reddit, blogs, official forums or livestreams (Grimmel, 2015; Najla, 2015; ShadowWolf8224, 2015; MMOGames.com, 2016; witchybop, 2022; OhJoSama, 2023; NicOTacos_, 2024; Vaynshteyn, 2024). Each time this happens, discussion around the game’s most distinctive horror story is reanimated once more, haunting the game’s community as an ongoing urban legend.

Conclusion

Much like Edda’s ghost, the encoded aspirations of both players and developers to cultivate spaces for meaningful social connection looms as an ever-present specter over the genre. From the way MMORPGs narratively and mechanically encode specific visions of heroism, to the way they design in-game systems with their imagined communities in mind, the complex foundations that make up their persistent online worlds boil down to the simple fact of our social drive -- the yearning for meaningful connection; the desire to perceive and be perceived in turn; and the opportunity to redefine ourselves, through a new digital guise, in the eyes of others.

This extensive foray into the narrative, history and ongoing reception of a single questline has sought to demonstrate that the social online worlds of MMORPGs remain not only alive, but rich and active sites for testing the bounds of narrative experimentation. The persistence and sociality of these worlds allows us to perceive the passage of time, oral history, fan discourse and paratext as interwoven into the narrative fabric of these games rather than incidental to it. It is my hope that, beyond discussions of methodology, this article might prompt further reexaminations of the MMORPG’s narrative potential. Perhaps then, might the genre move beyond its well-entrenched formulaic scaffold of heroic individualism to facilitate new models and possibilities for social play.

Endnotes

All screenshots in this article are copyright of © SQUARE ENIX, reproduced in accordance with the Final Fantasy XIV Materials Usage License: https://support.na.square-enix.com/rule.php?id=5382&tag=authc.

[1] Square Enix’s financial report shows that Final Fantasy XIV, the biggest title within the company’s MMO sector, as by far their biggest earner with an operating income of ¥6.6 billion (USD 42 million).

[2] Player response and fan studies approaches have been productively used to study the reception of other titles in the franchise, such as Square Enix’s influential Final Fantasy VII (1997) and its recent remakes -- Final Fantasy VII Remake (2020); Final Fantasy VII Rebirth (2024) -- with significant attention given to fans’ nostalgia and affective connections to the franchise (Bukač and Katić, 2024; van Ommen, 2018). Final Fantasy XIV, Square Enix’s main MMORPG project and most lucrative title (Square Enix, 2024), is designed, in part, as a “theme park” evocative of all the Final Fantasy games, and likewise taps into players’ emotional investments in the franchise.

[3] In an interview, Naoki Yoshida, producer of Final Fantasy XIV, declares a deep respect and admiration for World of Warcraft, which served as a model for what he hoped Final Fantasy XIV would be (blluist, 2021).

[4] For those keen in viewing the cutscene in motion and with audio, Kintarros (2014) offers a playthrough without commentary.

[5] Explicit instances of horror, which appear frequently in single-player video games, are comparatively uncommon in MMORPGs. Horror is generally experienced in single player format, as seen in franchises like Resident Evil and Silent Hill, or in small group cooperative games like Phasmophobia (Kinetic Games, 2020) and Lethal Company (Zeekerss, 2023). Without getting into a long exegesis on horror as a video game genre (for an extended discussion, see Perron, 2018, pp. 9-30), I propose that there are a number of MMORPGs, such as New World (Amazon Game Studios, 2021), that sufficiently incorporate horror motifs to be readily classed as “dark fantasy,” but the genre’s engagement with horror remains limited and inconsistent. Therrien even singles out MMORPGs as a general exception to the widespread incorporation of horror-themed gameplay into a variety of game genres (2009, p. 32).

[6] Tam-Tara Deepcroft (Hard) arrived with the 2.3 patch update, a year after the game’s A Realm Reborn relaunch. Exemplifying the experimental spirit of this questline, it was with this dungeon that the game began to play with alternative, “non-cheering” player-character responses upon completing a dungeon. These began to appear with much more regularity moving forward, especially during more “serious” moments of the game’s main story quest.

[7] One exception might be the “hardcore” modes available in some MMORPGs, like World of Warcraft and Runescape, where players risk losing their characters upon death. Even then, death here refers more a loss of status or reputation, since these games offer you the option to transfer your characters to a non-hardcore server or to continue -- albeit as a regular non-hardcore character.

References

4 Player Squad Gaming. (2021). Final Fantasy 14 -- A Realm Reborn -- Tam Tara Deepcroft Hard -- Dungeon Guide [YouTube Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M89uMiPBPjg

Albsterz Too. (2021). FIRST TIME REACTION TO EDDA PUREHEART STORY - (Tam-Tara Deepcroft -- Hard) [YouTube Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XqgPkqlnhU8

Amazon Games. (v. 1.14, 2024) [2021]. New World [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game developed and published by Amazon Games.

Apperley, T. H. (2006). Genre and Game Studies: Toward a Critical Approach to Video Game Genres. Simulation & Gaming, 37(1), 6-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878105282278

Appignani, T., Kruzan, K., & Hoch, I. N. (2015). Spirits in the Aether: Digital Ghosts in Final Fantasy XIV. Gamevironments, 2, 25-60.

ArenaNet. (v. 172,493, 2024) [2012]. Guild Wars 2 [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game developed by ArenaNet, published by NCSoft.

audioshaman. (2021). The Tam-Tara Deepcroft (Hard) story is pretty messed up [Reddit Post]. R/Ffxiv. www.reddit.com/r/ffxiv/comments/p049zb/the_tamtara_deepcroft_hard_story_is_pretty_messed/

Barreiro, V. (2014). When Two Lives Intersect [Blog Post]. MMORPG.Com. https://www.mmorpg.com/columns/when-two-lives-intersect-2000103390

Bartle, R. A. (2011). Unrealistic Expectations. In T. Krzywinska, E. MacCallum-Stewart, & J. Parsler (Eds.), Ringbearers: The Lord of the Rings Online as Intertextual Narrative (pp. 155-174). Manchester University Press.

Blizzard Entertainment. (v. 11.0.7, 2024) [2004]. World of Warcraft [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game designed by Rob Pardo, Jeff Kaplan, and Tom Chilton, published by Blizzard Entertainment.

blluist. (2021). Yoshida (FFXIV) on World of Warcraft (eng) [YouTube Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MgwliOmjHHE

Boluk, S., & Lemieux, P. (2017). Metagaming: Playing, Competing, Spectating, Cheating, Trading, Making, and Breaking Videogames - Intro. University of Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctt1n2ttjx

Boni, M. (Ed.). (2017). World Building: Transmedia, Fans, Industries. Amsterdam University Press.

Boudreau, K. (2018). Beyond Fun: Transgressive Gameplay -- Toxic and Problematic Player Behavior as Boundary Keeping. In K. Jørgensen & F. Karlsen (Eds.), Transgression in Games and Play (pp. 257-271). MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11550.001.0001

Brown, D., & Krzywinska, T. (2011). Following in the Footsteps of Fellowship: A Tale of There and Back Again -- Text/Translation/Tolkienisation. In T. Krzywinska, E. MacCallum-Stewart, & J. Parsler (Eds.), Ringbearers: The Lord of the Rings Online as Intertextual Narrative (pp. 13-45). Manchester University Press.

Bukač, Z., & Katić, M. (2024). “A Legend From Before You Were Born”: Final Fantasy VII, Folklore, and Popular Culture. Games and Culture, 19(8), 1055-1070. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120231187753

Calleja, G. (2011). Narrative Generation in The Lord of the Rings Online. In T. Krzywinska, E. MacCallum-Stewart, & J. Parsler (Eds.), Ringbearers: The Lord of the Rings Online as Intertextual Narrative (pp. 93-110). Manchester University Press.

Carter, M. (2015). Massively Multiplayer Dark Play: Treacherous Play in EVE Online. In T. E. Mortensen, J. Linderoth, & A. M. L. Brown (Eds.), The Dark Side of Game Play: Controversial Issues in Playful Environments (pp. 191-209). Routledge.

Castronova, E. (2005). Synthetic Worlds: The Business and Culture of Online Games. University of Chicago Press.

Christopher, D., & Leuszler, A. (2023). Horror Video Games and the “Active-Passive” Debate. Games and Culture, 18(2), 209-228. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120221088115

Coldrun Gaming. (2018). FFXIV - Part 66: The Hazards of Love [Blog Post]. Coldrun Gaming. http://coldrungaming.blogspot.com/2018/06/ffxiv-part-66-hazards-of-love.html

Corneliussen, H., & Rettberg, J. W. (Eds.). (2008). Digital Culture, Play, and Identity: A World of Warcraft Reader. MIT Press.

Cuddy, L., & Nordlinger, J. (Eds.). (2009). World of Warcraft and Philosophy: Wrath of the Philosopher King (First printing). Open Court.

Derrida, J. (1994). Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International. Routledge.

ELHC. (2020). After doing the Edda quest, this group outside Sastasha (Hard) really freaks me out... [Reddit Post]. R/Ffxiv. www.reddit.com/r/ffxiv/comments/kbxzg0/after_doing_the_edda_quest_this_group_outside/

Fest, B. J. (2016). Metaproceduralism: The Stanley Parable and the Legacies of Postmodern Metafiction. Wide Screen, 6(1).

Firestorm. (2019). Firestorm plays Final Fantasy 14 [Blog Post]. Clubs That Suck. https://clubsthatsuck.jcink.net/index.php?showtopic=2887&st=20

Flanagan, M. (2009). Critical Play: Radical Game Design. MIT Press.

Geraci, R. M., Recine, N., & Fox, S. (2016). Grotesque Gaming: The Monstrous in Online Worlds. Preternature: Critical and Historical Studies on the Preternatural, 5(2), 213-236. https://doi.org/10.5325/preternature.5.2.0213

Glas, R. (2015). Of Heroes and Henchmen: The Conventions of Killing Generic Expendables in Digital Games. In T. E. Mortensen, J. Linderoth, & A. M. L. Brown (Eds.), The Dark Side of Game Play: Controversial Issues in Playful Environments (pp. 33-49). Routledge.

Gravity Interactive. (2008). Requiem: Memento Mori [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game developed and published by Gravity Interactive.

Grimmel. (2015). 1% Chance of Ghost Spawn [Online post]. https://forum.square-enix.com/ffxiv/threads/231798-1-Chance-of-Ghost-Spawn

Hassall, M. (2022). Final Fantasy XIV wins Best Game Community at Golden Joystick Awards [Magazine Article]. Pro Game Guides. https://progameguides.com/final-fantasy/final-fantasy-xiv-wins-best-game-community-at-golden-joystick-awards/

Huber, W. (2022). The Pseudo-allegory of Final Fantasy XIV. In R. Hutchinson & J. Pelletier-Gagnon (Eds.), Japanese Role-Playing Games: Genre, Representation, and Liminality in the JRPG (pp. 255-276). Lexington Books/Fortress Academic.

Isbister, K. (2016). How Games Move Us: Emotion by Design. MIT Press.

Jackson, S. C. (2024). Don’t Stand in the Fire!: Effective Collaboration, Communication, Interaction, and Strategy in Mediated Environments -- A Discourse Analytic Approach to MMORPG Streaming on Twitch. Pennsylvania State University.

Jagex. (v. 939.1, 2024) [2001]. Runescape [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game designed by Andrew Gower and Paul Gower, published by Jagex.

Jennings, S. C. (2022). Only You Can Save the World (of Videogames): Authoritarian Agencies in the Heroism of Videogame Design, Play, and Culture. Convergence, 28(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565221079157

JetStrim. (2021). Not gonna lie, the end of Tam Tara Deepcroft (Hard) quest line scared me [Reddit Post]. R/Ffxiv. www.reddit.com/r/ffxiv/comments/pgez90/not_gonna_lie_the_end_of_tam_tara_deepcroft_hard/

Kinetic Games. (2020). Phasmophobia [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game developed and published by Kinetic Games.

Kintarros. (2014). FFXIV ARR - Tam-Tara Deepcroft (Hard) -- All Cutscenes [YouTube Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bRRUzPTkGzo

Klastrup, L. (2008). What Makes World of Warcraft a World? A Note on Death and Dying. In H. Corneliussen & J. W. Rettberg (Eds.), Digital Culture, Play, and Identity: A World of Warcraft Reader (pp. 143-166). MIT Press.

Klastrup, L., & Tosca, S. (2011). When Fans Become Players: LOTRO in a Transmedial World. In T. Krzywinska, E. MacCallum-Stewart, & J. Parsler (Eds.), Ringbearers: The Lord of the Rings Online as Intertextual Narrative (pp. 46-69). Manchester University Press.

Krobová, T. F., Janik, J., & Švelch, J. (2022). Summoning Ghosts of Post-Soviet Spaces: A Comparative Study of the Horror Games Someday You’ll Return and the Medium. Studies in Eastern European Cinema, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/2040350X.2022.2071520

Krzywinska, T. (2002). Hands-On Horror. Spectator, 22(2), 12-23.

Krzywinska, T., MacCallum-Stewart, E., & Parsler, J. (Eds.). (2011). Ringbearers: The Lord of the Rings Online as Intertextual Narrative. Manchester University Press.

Lehdonvirta, V. (2010). Game Studies -- Virtual Worlds Don’t Exist: Questioning the Dichotomous Approach in MMO Studies. Game Studies, 10(1). http://www.gamestudies.org/1001/articles/lehdonvirta/

MacCallum-Stewart, E. (2014). Online Games, Social Narratives. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315763750

Martindale, C. (1993). Redeeming the Text: Latin Poetry and the Hermeneutics of Reception. Cambridge University Press.

Mäyrä, F. (2011). From the Demonic Tradition to Art-Evil in Digital Games: Monstrous Pleasures in The Lord of the Rings Online. In T. Krzywinska, E. MacCallum-Stewart, & J. Parsler (Eds.), Ringbearers: The Lord of the Rings Online as Intertextual Narrative (pp. 111-135). Manchester University Press.

MindflayerFlayer. (2021). Sightings of Edda Pureheart’s group [Forum Post]. https://forum.square-enix.com/ffxiv/threads/432282

MMOGames.com. (2016). FFXIV’s Horror Story, Edda’s Creepshow and the Palace of the Dead [Blog Post]. MMOGames.com. https://www.mmogames.com/articles/archives/ffxivs-horror-story-eddas-creepshow-palace-dead/

Morris, L. (2023). On the Preservation of the Experience of Play in an MMORPG Environment: Livestreams and the Game Preservation Conundrum. Abstract Proceedings of DiGRA 2023 Conference: Limits and Margins of Games. DiGRA 2023 Conference, Guadalajara.

Mortensen, T. E., & Jørgensen, K. (2020). The Paradox of Transgression in Games (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367816476

Najla. (2015). Edda’s ghost sightings [Forum Post]. FFXIV Realm. http://ffxivrealm.com/threads/eddas-ghost-sightings.14272/