Mindspacing and Play -- Indie Games in the Context of Mental Health Depiction

by Moritz Wischert-ZielkeAbstract

Previous research has shown that AAA video games tend to exploit and marginalize themes of mental illness. Indie games, however, have not been adequately discussed in this context. Hence, the present essay examines how indie games practice de/marginalization by strategically thematizing the mind, mental health, and mental illness. To move beyond the field’s question of supposedly better or more authentic representation, a specific focus of the analysis is the question of mindspacing, i.e. how the titles examined co-position and relate the elements of mind and space in their production of playful worlds. The recent titles Shrinking Pains (2018), The Longest Walk (2022) and The Psychotic Bathtub (2024), dealing with anorectic, depressive and psychotic experiences respectively, reveal the counterhegemonic potential of indie games not just to present different stories about mental health but to reimagine culturally dominant forms of play.

Keywords: indie games, play, mental health, de/marginalization, mindspace, care of the self

1. Introduction: Mental Health, De/Marginalization, and the Role of Indie Games

There is mounting evidence that visual mass media frequently depict themes of mental illness. For the greater part, researchers describe these depictions as stereotypical, stigmatizing and inaccurately associated with violence and danger (Eisenhauer, 2008; Gilman, 1982; Hyler et al., 1991; Pirkis et al., 2006; Riles et al., 2021; Stuart, 2006; Wahl, 1995). In contrast, studies examining how video games represent mental health and mental illness form a small but growing body of research.

Large-scale quantitative studies consistently show that AAA games tend to marginalize and discriminate against mental health topics (Buday et al., 2022; Ferrari et al., 2019; Kasdorf, 2023; Mittmann et al., 2024; Shapiro & Rotter, 2016). Meanwhile, qualitative research has begun to highlight more nuanced and positive depictions and the potential of the medium to foster different types of portrayals (Anderson, 2020; Austin, 2021; Dunlap & Kowert, 2025; Morris & Forrest, 2013; Schlote & Major, 2021). In light of these results, the questions arise whether indie games [1] can be described as sites of demarginalization for mental health topics and what strategies they may use to achieve this.

Indie games were only gradually incorporated as a focus of game studies in the latter half of the 2000s (Parker, 2014). Clarke and Wang (2020) regard them “not simply [as] an experiment in artistic creation but also one of social and economic experimentation in which its participants actively interrogate their internal cultural and economic motivations, their relations to the larger community of makers and users, the sociocultural function of their texts, and their attitude toward the technological affordances available to them” (p. 2). As “a cultural phenomenon that reflects ideological tensions of our time, frictions between hegemonic culture and counter-culture, progressivism and conservatism, capitalism and anti-capitalism” (Latorre, 2016, p. 28), indie games can be questioned as sites of discursive struggle. Previous research emphasizes their demarginalizing potential through their capacity to “alter [...] typical gaming formats in terms of mechanics, gameplay, visual style, and theme” (Clarke & Wang, 2020, p. 9).

Indie games should therefore be regarded in the context of mental health depictions. The present essay contributes to this discussion by examining how indie games function as carriers of practices of demarginalization regarding mental health phenomena. To my knowledge, only one study has directly assessed this role: King and colleagues’ (2021) analysis of seven games concludes that “[i]ndie games provide a rich and diverse example of the use of narrative, mechanics, and aesthetics to tell emotional stories about mental illness, trauma, grief, LGBTQ+ experiences and neurodiversity” (p. 149). Like most previous studies, their contribution calls for what is perceived as a more authentic kind of representation of mental health experiences.

To better understand the distinct doings of indie games, the present essay poses three questions to guide the following analysis and add to a more qualitative and in-depth view of the role of indie games. First, this article questions how indie games deploy specific strategies of demarginalization in the context of mental health depictions. Second, as video games offer and afford specific practices of play, how do their imaginaries of play challenge the implicit, hegemonic norms governing what games are and how they should be played? In particular, this essay addresses the notion of a tyranny of fun, or the dominant expectation that games must always entertain. This concept will be unpacked along with the general approach and methodology before the essay proceeds to the analysis. Third, drawing on Meinel’s idea of games as “a medium inherently characterized by its various modes of spatial production” (2022, p. 1), this essay examines how the elements of mind and space mutually co-position each other. This practice, termed mindspacing, is outlined as a new interpretative framework for mental health research in an intermediary step. By exploring these questions, this essay not only presents a series of indie game case studies but also illustrates how such games challenge dominant, stigmatizing portrayals of mental illness and reimagine the very forms that play can take, offering alternative ways of engaging with mental health phenomena.

2. A Perspective of Mindspacing

Discursive analyses of the mind and mental health lack conceptual tools that account for the complex narratives offered by visual media. Cultural studies frequently relies on representational frameworks, using clinical diagnoses as benchmarks to judge the “authenticity” or “adequacy” of visual portrayals (Hyler, 1988; Nordahl-Hansen et al., 2018). These approaches tend to reduce the aesthetic, experiential, and formal complexity of visual media to checklist-style validations. The work by Dunlap and Kowert (2021) has attempted to add depth to the categorial perspectives of the field, which often sort media into positive or negative portrayals. The authors advocate assessing portrayals on a continuum model from decorative, those of “minimal significance” (p. 127), to defining, in which “psychopathological features are essential to [...] a character, story, or setting” (p. 128), and dimensional representations, which view mental health “from multiple perspectives” (p. 128). While their approach allows for an assessment of the depth and role of a portrayal, there remains a problematic question in how far dimensional representations “reflect authentic experiences” (p. 128), as the authors claim. Non-representational approaches, which aim at the very matrix of portrayal and intelligibilization, remain underexplored.

One recent intervention is Anh-Thu Nguyen’s adaptation of the literary and film studies concept of mindspace to the medium of video games. In Nguyen’s work, the concept refers to visual spaces in games and films that “express the cognitive process of a character” (2022, p. 51). Consider, for example, the fantasy world of Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), which depicts the mind as an inner refuge from fascist violence. As Nguyen convincingly argues, mindspaces often present “a visual experience [...] linked to mental and emotional trauma” (p. 54). In her reading of Persona 5, she argues that in-game locations “specifically [address] themes such as trauma and depression as a manifestation of [a character’s] mental state” (p. 59).

Building on and departing from Nguyen, I propose the concept of mindspacing as a praxeological and non-representational lens for studying the entanglement of space and mind in visual media, particularly games. As a ubiquitous everyday practice of how visual media are understood and navigated, mindspacing points to the mutual intelligibilization and co-constitution of space and mind. When a viewer watches a film or a player plays a game dealing with the mind, mental health, or mental illness, implicit and explicit understandings of both elements, the mental and the spatial, are constantly cued and accomplished. Whereas Nguyen’s use of the concept holds that mindscapes “give internal states -- feelings and memories -- a shape in landscape form” (p. 52), the perspective of mindspacing that I suggest does not presuppose a framing of the mind as an inner space for which an external container-space serves as a canvas (this is only one possible, albeit dominant outcome of mindspacing). Rather, mindspacing refers to an ongoing discursive and experiential configuration through which both mind and space are related, made meaningful, and imag(in)ed together. Beyond representing mental health, mindspacing emphasizes that narratives must both place the mind and allow space to engage with the mental dimensions of social life in order to ensure intelligibility. In Lefebvrian terms, mindspacing concerns how the “perceived” and the “conceived” (1991, p. 38), i.e., the physical and the mental, are related rather than separated, as “[i]n actuality each of these two kinds of space involves, underpins and presupposes the other” (p. 14), as Lefebvre reminds us. Questioning mind as internal and space as external, mindspacing foregrounds this mutual implication and invites inquiry into how the specific contributions of a medium render spatio-mental phenomena intelligible within its formal and cultural logics.

Figure 1. Emotional baggage in Psychonauts 2 (2021). Click image to enlarge.

Crucially, this perspective regards mindspacing as an embodied and materially mediated practice [2]. Therefore, it is intricately linked to the routinized and skilled bodies of cinema audiences, viewers of streaming services, or game players. Together with the visual media texts in question (films, paintings, video games, etc.), the living bodies of viewers and players who actively receive and posit these texts as intelligible need to be regarded as “carriers[s]” (Reckwitz, 2002, p. 250) of the practice. While the forms of embodiment strongly depend on the medium in question, the mindspacing body is always active: when playing a video game like Psychonauts 1 or 2, I am not only actively (though implicitly) negotiating the meaning of scattered pieces of “emotional baggage” (fig. 1) as mental and spatial entities. I am also moving the perspective and game states onward via unconscious circles of interactional embodiment (based on controls and visual/sonic/haptic feedback). For this proprioceptive kind of embodiment, it is also crucial, whether the location of a puzzle in the game world is understood as part of the usual game world or one of the characters’ minds, which the player gets to travel in the two titles. But even regarding the fixed visual sequencing of film, the mindspacing body cannot be described as passive. Take for example the ending of the film Inception (2010), which is often interpreted differently by different viewers: the shared accomplishment of whether a scene is understood as a dream or not always requires the mutual negotiation of a text and its activated body. Mindspacing is also ubiquitous in film, but it takes on a distinct quality in games, where the player is not only an active perceiver but a co-producer of the text’s meaning and spatiality. The element of interaction makes games unusually explicit sites of this otherwise habitual and often invisible practice.

By shifting attention from representational accuracy to the spatial-discursive practices that implicitly underpin and uphold how space and mind are conceived, mindspacing offers a novel, more dynamic and nuanced framework for understanding games and visual media. In the context of video game research, its processual perspective on meaning-making works towards a fuller recognition of embodiment and player (co-)agency. Generally, mindspacing allows for broader explorations of how cultural portrayals relate the spatial and the mental. At the same time, its double focus enables perspectives on mental health to move further toward the denaturalization of the Western metaphysics of the mind as an inner realm. This is particularly relevant where previous approaches have tended to reinforce static and internalizing (i.e., privatizing) views of the mind and mental illness.

3. Approach and Method: Games as Play Partners and the Tyranny of Fun

Game studies has an impulse to revitalize processual and relational approaches to games and play. Highlighting the specific, appropriative mediality of play and gameplay, Miguel Sicart’s work (2011; 2014; 2022) has criticized some of the dominant game studies perspectives on play as formalistic and reductive. His article “Against Procedurality” argues that proceduralism “often disregards the importance of play and players as activities that have creative, performative properties.” Procedurality, which can be linked to influential works on games (see e.g., Bogost 2006, 2007; Janet H. Murray, 2016 [1997]) and game design (e.g., Flanagan, 2009), can be criticized for its often-implicit epistemic assumption that meaning in gameplay arises primarily from rules, mechanics, and digital procedures. In Sicart’s reading, proceduralism “argues that it is in the formal properties of the rules where the meaning of a game can be found. And what players do is actively complete the meaning suggested and guided by the rules. For proceduralists [...] the game is the rules” (2011). The resulting critique targets perspectives that reduce play to a type of conditioned, normative, or “instrumental play, as the process of playing for other means, as play subordinated to the goals and rules and systems of the game.”

The ways digital games favor specific types of interactions remain crucial for the mediality of gameplay. This article, therefore, draws from a second critical impulse to rethink the concept of form. The discourse of new formalism in American literary studies arose from a movement in the 2000s revolving around the role of form [3]. Caroline Levine is one of the voices calling for a renewed and activist interest in form. Her book Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network broadens the use of the term form to encompass any patterns of sociocultural experience: form entails an “arrangement of elements -- an ordering, patterning, or shaping,” it relates to “all shapes and configurations, all ordering principles, all patterns of repetition and difference” (2015, p. 3). Whereas forms have been traditionally thought of as containing, plural, overlapping, portable and situated, Levine links them to the concept of affordance and thus “potential uses or actions latent in materials and designs” (p. 6). Returning to the discourse on play, Levine’s emphasis on the way games afford particular practices of play may reinforce and specify some of the critique of subjectivity in ludologist approaches, as advocated by Sicart. Aubrey Anable’s critique of the blind spots of play-centered approaches, on that note, concerns the “overestimation of interactivity and the power of players to invest video games with whatever meanings they choose” (p. xiv).

To tie together these impulses -- both the focus on play as a rule-challenging and appropriative socio-cultural practice in which games participate, and the critique of a ludologist overemphasis on the supposedly free and detached, political player-subject -- the present article regards games as play partners in the following. Gadamer’s work (2004) frames the players “not [as] the subjects of play;” rather, he argues, play merely “reaches presentation” (p. 103) through them. Along similar lines, my previous work regards games, along with living bodies, other things, and ideas, as “play partners” (Wischert-Zielke, 2024, p. 94). This approach foregrounds the shared roles of player and game that mutually co-position and en- or disable each other to play in ways specific to the processual and non-innocent unfolding of the ensemble of partners in question. Speaking with Haraway, play is a form of “becoming-with,” which describes “how partners are [. . .] rendered capable” (2016, p. 12). At the same time, specific forms of play are afforded and others disabled, which is why playful unfolding is never innocent, and mutual corruption is inevitable.

According to this perspective on games as play partners, the meaning of games cannot be deduced in an inventory of rules, since form-meaning relations only come into being through mutual processual entanglement. Rather than associating playful agency with a detached political player-subject, the afforded practices of play direct the present analysis toward wider socio-cultural processes of formalization carried by games. The fault of proceduralism is, from this perspective, not merely a reductive reading of play (which could be discarded in favor of a more accurate reading) but the sedimentation of contingent types of play, which makes hegemonic forms of play unquestionable. Thus, Sicart’s anti-proceduralist critique of essentializing game formalism can be linked to a wider interest in how games take part in (re)formalizations of play as accomplishments of their mediality as play partners.

Methodologically, the present essay, therefore, pursues a double interest: the form of games and their formalizing tendencies in and of play. Both interests are considered in a postphenomenological game analysis that draws from Brendan Keogh’s work on “embodied textuality” (2014, p. 21). According to Keogh’s perspective, “the synthesized embodied experience of audiovisual design, videogame hardware, and the player’s physical body constitute the site of meaningful engagement with the videogame” (p. 21). Together with a procedural attention to the form of games (which both shapes the form of play and is negotiated within it), postphenomenology is particularly promising for its attention to the contingent player experience. Though non-universal, it offers an attuned perspective to the everyday lived world, and, most importantly, is mediated and positioned through the material-technological individuations of a game as play partner and the socio-cultural formalization of play practices. Hence, the following analysis relies on “the player-and-game as the object of study, as one textual machine” (p. 17).

Finally, the approach toward indie games as play partners situates these games in the context of imaginaries of play. Following previous research on AAA games, hegemonic forms of play often indulge in (neoliberal) capitalist, (neo-)colonialist, racist, sexist, and extractivist concepts and practices of play (Chang, 2011; Dyer-Witheford & de Peuter, 2009; Goggin, 2011; Harrer, 2018; Leonard, 2003; Murray, 2018). In the following analysis, it is hypothesized that indie games (need to) respond to what could be described as the tyranny of fun in the context of mental health. Through this term, I aim to render addressable and hold accountable one particular complex of relations of what Sicart calls the “ecology of play” (2014, p. 43), or the sum of contexts made and required for play to take place. The tyranny of fun describes the exclusive emphasis on positive emotions as a disciplinary, cultural and commercial regime. Tying into the colonial impulse to dominate and control, as well as the neoliberal-capitalist focus on the individual, the tyranny of fun normalizes the production and consumption of positive affects and emotions. As mainstream game studios are driven by commercial imperatives and risk-averse publishing strategies, they often prioritize marketable genres and fantasies of power, thus reproducing familiar tropes found in successful game titles and series. The tyranny of fun, therefore, prioritizes narratives of individual, telic progression and self-reliant growth, while simultaneously rejecting and marginalizing other experiences and narratives as allegedly not playful or playable.

Many scholars have noted the transgressive elements of play. Stenros, for instance, describes “parapathic” play as involving negative emotions or topics “considered too sensitive for games and play to handle” (2018, p. 19). Etymologically, however, the term parapathic designates deviating or abnormal emotional reactions or relations, thus reaffirming and naturalizing particular forms of play, which should be regarded as hegemonic and contingent instead. The tyranny of fun flattens embodied affectivity into a cultural-economic doing. This flattening is less frequently discussed in game research. Psychoanalyst Winnicott is among the few to suggest that “playing is always liable to become frightening. Games and their organization must be looked at as part of an attempt to forestall the frightening aspect of playing” (2006, p. 59, emphasis added).

Given the expectation that games and play should be entertaining, pleasurable and light-hearted, indie games may challenge the tyranny of fun by making space for alternative imaginaries and forms of play. Less bound by genre conventions or mass-market expectations, these games are often well-positioned to explore emotions and experiences that fall outside the dominant emphasis on positivity, progression and personal optimization. In the context of mental health, some indie games appear to experiment with discomfort, failure, ambiguity and emotional vulnerability in ways that complicate mainstream expectations of playability and contrast how AAA games portray the mind and mental illness. Rather than centering fun as the primary goal, these games may instead invoke experiences of unresolvable struggle, empathy or reflection. As such, indie games hold the potential to reimagine play as a site for more diverse, complicated and unexpected emotional encounters.

4. Analysis: Indie Games, Mindspacing, and Demarginalization in the Context of Mental Health

To examine indie games for their 1) strategies for demarginalization, 2) imaginaries of play and 3) practices of mindspacing, I have selected three recent titles for the analysis: Shrinking Pains (2018), The Longest Walk (2022) and The Psychotic Bathtub (2024), which thematize anorexia, depression and psychotic experiences, respectively [4]. In the following sub-sections, each game will be examined consecutively and in chronological order.

4.1. Shrinking Pains (2018)

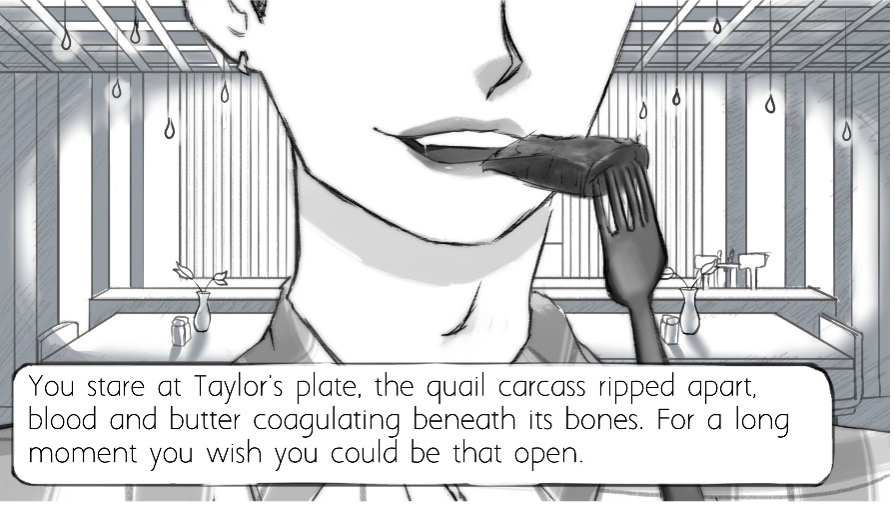

Figure 2. A POV-image in Shrinking Pains. Click image to enlarge.

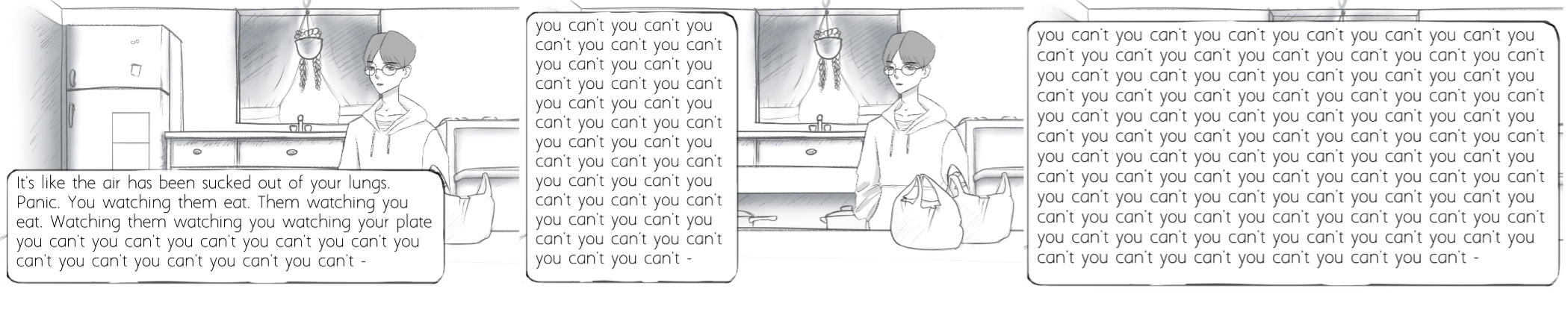

With a total playtime of about 15 to 20 minutes, Shrinking Pains (SP) is a short, free, autobiographical and narrative-driven game that explores experiences of living and struggling with anorexia. The game’s visual novel approach aims to depict anorexia through a composite spatiality resembling point-of-view shots (fig. 2). The images presented are tied to the (first person) perspective of the main character, who thus remains invisible but indirectly focalizes all layers of the narrative, from sound effects to moments of close-up style impressions [5]. As in the graphic novel medium, the surrounding physical world is combined with speech and thought bubbles, relating everyday conversations and the thoughts of the protagonist. The game explicitly identifies the unnamed protagonist with the (implied) player: the many speech bubbles directly frame the protagonist’s thoughts as the player’s, addressing her in the second person singular. The title varies the gender of the protagonist’s partner according to player preference to further push this coupling between player and character.

Through these strategies of strong focalization and player positioning, SP creates a personal narrative that draws the player into the character’s individual web of feelings, affects and thoughts, as well as interpersonal relations and expectations as they come together in daily situations, all of which borders heavily on existential themes. The player-character wakes up next to her partner, stares at the ceiling, hardly gets out of bed, and is challenged by the conflicting emotions of feeling both cared for and heavily pressured by the offer of a cup of coffee. As the couple later celebrates their anniversary over dinner, the player-character

Figure 3. Phenomenological reflections on the anorectic body. Click image to enlarge.

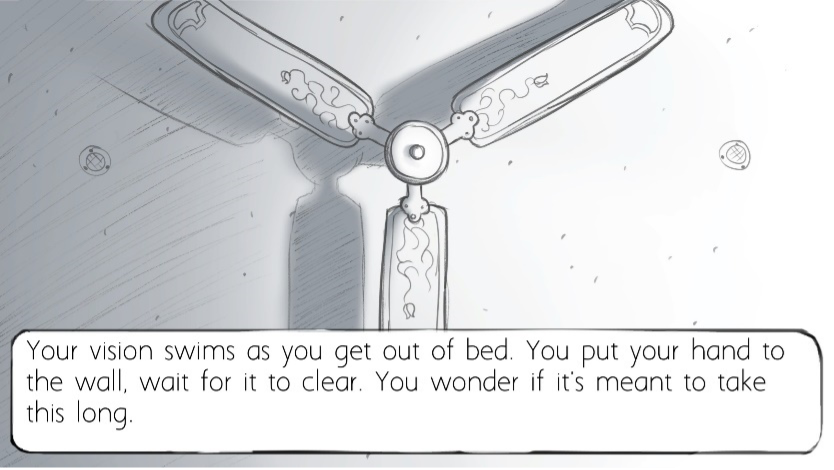

struggles not just with eating but also with watching their partner eat. In scenes like this, SP strategically utilizes the semantic register of the body and the senses, relating to the smell and texture of meat, which are perceived as revolting and nauseating, or the feeling of their own body perceived as an absurd object: “the feel of the fat of your thighs pressing together when you sit down, the fold where your stomach meets your legs.” The anorectic experience’s controlling, objectifying self-reference is echoed in the stream-of-consciousness through almost clinical language, with terms like “vertebrae” and “collarbone.” As the bodily/mental well-being of the main character deteriorates, the game offers these bodily sensations as situated knowledges (Haraway, 1988) to the player, who is confronted with an attentive and small-scale phenomenology of the anorectic body, its drives and affective reactions towards the world (fig. 3). In situated perceptions and reflections upon them -- such as when the player-character watches the ceiling and realizes how their perception has changed because of malnutrition -- the player is directly approached by this phenomenology, which suggests itself as an intimate and honest reflection of experience.

The distinct visual style of the artwork carries a further strategy to relate the protagonist’s experience to the player. Beyond the verbal reflections presented in the speech and thought bubbles, which remain abstract despite their intimate and honest sense of embodiment, the stencil-style drawings more directly convey some of the game’s themes. Dominant white patches, reminiscent of an indifferent void, seem to threaten the already fading lines and shapes of bodies and words. This visual tension adds to the non-verbal portrayal of a personal struggle against death, where the will to power and the will to live coexist within a shifting, conflicted self. The color red appears in a handful of single images (and is immediately blended with black), suggesting a drive or impulse beneath the surface: an existential hunger, a reaching toward the other, charged with the force through which life asserts itself into the world. It is telling that this patch of red Eros emerges only in the scene where the player-character has a one-night stand, a moment in which pain and pleasure (perhaps precisely because they are detached from love and affection) converge into a momentary unity.

Besides sharing the situated knowledges and inviting the player to progress the story, how does the game enable playful interaction? The linearity of the procedural montage is shot through with small choices that confront the player, introducing forks in the road and asking her to position herself further as the main protagonist, thus combining non-linearity with playful experimentation. She imagines the potential consequences of each option for the situation and further narrative, but may, however, only pick one option, which encourages several playthroughs. Given that the game is short, it is highly replayable due to its capacity to respond differently to different player choices.

Figure 4. The first choice in Shrinking Pains. Click image to enlarge.

Mundane choices lie at the heart of the game, echoing across the parallel experiences of player and character: what feels like routine interaction for the player becomes, for the character, a struggle between life and death -- and in that dissonance, everyday play turns tragic. The first choice in the game, for instance, involves the decision of what to eat for dinner (fig. 4). Besides eating, choices involve how to respond to friends on social media and whether the player-character reaches out to others or allows them to care for them. Overall, SP refuses to restrict itself to light-hearted or happy themes to appeal to an audience. It engages in a self-aware framing of its choices and plays against the implied player’s hegemonic expectation of total self-efficacy. Sometimes, the choices disappear when the player chooses to eat. Other times, the bubble communicating an alternative course of action gets smaller and smaller when the player clicks on it, until it becomes a mere pixel: technically still there, but fundamentally out of reach for the player-character. Here, disabling the player is a strong strategy to involve her in a different mode of being, operating under a different regime of agency afforded to a mutually-imagined anorectic experience. However, in clicking again and again on the option that she considers to be right, the player can attempt to counter the anorectic pattern. Through disabling the player, the game also enables her to position herself, take care of the player-character, and develop a sense of struggle, responsibility and agency. Ultimately, the game allows the player’s choices to matter and influence the ending of the game, in which the main character will either pass out (and is indicated to die) alone and isolated at home, or wake up at the hospital after having reached out to a friend often enough throughout the course of the game.

Figure 5. The image’s spatial composition shift expresses a panic attack. Click image to enlarge.

Regarding its practices of mindspacing, SP’s spatial composition successfully integrates expressions of the physical, the mental and, via interpersonal dialogues, the social within a unified plain of visuality. Ambient sounds ranging from monotonous low humming to piercing tinnitus-like whistling further affect these levels and integrate them. While the use of color links the physical to the mental, the semantics of language used for phenomenalizing experiences of anorexia do not separate the body and the mind. There is frequent interaction of the spatial elements, for instance, when the protagonist expresses an inner struggle, but, in the very next moment, another character sees it in their eyes, and the mental side becomes a topic of social exchange and negotiation. A further example is the taking over of the expressive surface of the image by a single element, which shows the intrusive and inescapable force of a rising panic attack signified by the growing thought bubble that conquers the socio-physical portions of the screen (fig. 5). Thus, the mental and the spatial are not separated but rather mutually express each other, allowing for a constellation of subjectivity in which strong focalization and mental processes are immediately tied to the physical and the social.

The strategic framing of anorexia as a personal experience thus succeeds in placing the condition in a social world where the themes of personal borders, the responsibility of friends, and the viability of interpersonal (and, particularly, romantic) relationships can be questioned and explored. The drawback of immediately individuating the player-character in this way is that it severs anorexia from some of the socio-cultural processes from which it originates. As a result, the title, despite its otherwise balanced approach, does not engage with questions about the role of the media (e.g., the visual normalization of ageist, sexist, racist body ideals) or the internalizing and privatizing tendencies of psychological and psychiatric discourses on anorexia.

4.2. The Longest Walk (2022)

The Longest Walk (LW) is a short experimental game that is advertised as a “deeply personal” and “biographical” take on the experience of living with depression (Tarvet, 2024). Designed as a walking simulator, it features a three-dimensional traversable world that is combined with sonic footage from an interview with the designer’s father about the latter’s depressive episodes. While, as in SP, a personal micro-narrative is thus employed to portray mental illness, the documentary character of the design goes in a different direction.

The game opens in an endless dark void, with a black cloud hovering in the distance. By pressing “W,” the player moves the floating perspective forward and turns it around on a 360-degree axis. White footsteps on the ground appear, leading into the black smoke ahead. As the screen turns black, a man’s voice begins speaking in a Scottish accent: “I felt, um… anxious. So anxious that I, eh… I was burning. I was, em… My heart was beating really fast. I couldn’t sleep. I got tireder and tireder because I couldn’t sleep because I was worrying…” Next, the image of a human body appears on a rug, floating in the black void. The voice conjures the memory of breaking down howling with self-hatred. Then, the scene fades and the game relocates the player within a grey-white emptiness. The voice speaks about realizing something was wrong when driving back home crying. A blur of color in the distance: a fragmented version of a car. As the voice pulls the player further into the distance, more detached patches of scenery appear: pieces of pavement, grass, road signs and later, an underpass, glistening sand and stripes of the ocean.

LW differs from SP in that it does not incorporate choices in its mechanics of movement and progression: the player navigates along the traversable and linear path, triggering the narrative instances consecutively. While its concept of play is thus rudimentary, the three-dimensional world to be explored combines a documentary claim to realism with estranging but expressive fragmentation.

In terms of visual style, the game’s all-encompassing white nothingness prevents the perception of a coherent world: only stripes and patches, fragments and pieces, interrupted and surrounded by more nothingness (fig. 6). From a distance, the shapes presented appear photorealistic and identifiable, but once the player moves in closer, these shapes cease to communicate stable identities, and it becomes clear that they are made up of further single squares of colors. Every tiny fragment thus remains isolated, disconnected and lost. As with the strategic use of visuality in SP, the presentation of LW’s world expresses and connects to its themes of fragmentation, loss of meaning and collapse, which also surface in the spoken narrative elements.

Figure 6. Example of the game’s visually fragmented space. Click image to enlarge.

The auditory recording that forms the basis of the soundscape is a personal testimony: a retrospective account of living with depression. As it speaks and moves, the voice is laden with emotion, affected by memories and feelings that are not mere recollections of the past but animations of the voice itself; it hastens, struggles, stutters, pauses, falls silent, or becomes stuck in repetitions, gains sudden speed, and leaps ahead as it gathers itself and finds the right words. It recounts bodily sensations, vivid memories and suicidal thoughts. It focuses on the emotional qualities of anxiety and self-doubt, and places depression within the social contexts of work, friends and family. The soundscape testifies to a distinct and situated recording: the voice’s rhythm, pitch, accent and idiosyncrasies (e.g., spontaneous laughter) individuate the narrative account, creating an atmosphere of giving testimony -- intimate, personal and affectively resonant. The material conditions of the recording further contribute to this atmosphere. The microphone’s reactions (crackling, uneven volume, unintended background noises, a noticeable noise floor) suggest an amateur setup. These imperfections paradoxically lend the recording both artificiality and a heightened sense of authenticity, as if the medium’s rawness testifies to its unfiltered relation to reality. Because the voice of the interviewer is removed, the recording becomes a monologic stream. This creates a unique experience of addressability for the player: the speaker is disembodied yet affectively present, and their testimony invites a response without immediately demanding one.

Figure 7. A color patch universe in the interior of an in-game car. Click image to enlarge.

The game’s two expressive channels (fragmented visuality and documentative sound) are combined in the processual and embodied interaction with the player. Though the player may find her body engaged in navigation, perception and movement, in a way resembling the (more telic) genre of the guided walking tour, she is also able to playfully relate to the game through these activities. While playing the title, one may notice a contrast between intimate attention to the scripted visual-auditory narrative and playful probing of the limits and features of the game as a space of possibility. Meddling with the fragmented frame of the car at the beginning of the walk, for instance, may turn into the creative act of exploring novel sights/sites of play with the game’s materiality. For example, when I recursively position and rotate the camera perspective within the interior of the car during my own playthrough, I become fascinated by the emerging constellations of color patches, which evoke the genesis of new (pixel) universes (fig. 7).

Movement thus becomes an important site for the negotiation of meaning in the game, in which straight walking and queer meandering emerge as rivaling forms (Ruberg, 2020). LW, however, fosters a linear and straight movement in which straying and strolling, the movements of the flaneur, are possible but not rewarded. Branching and non-linear paths are not part of the design, which blocks the side sections between narrative triggers with invisible walls. However, the two channels of sound and visuality constantly animate each other even when they vie for attention. As the game places its walk on the Tay Road Bridge, Scotland, “which is an infamous local landmark for those seeking to take their life” (Tarvet, 2024), the fragmented patches do not merely add a setting for the sound file but also site it as an account of depression and mental health and open it up to larger socio-historical dimensions [6].

Combining movement, sound and visuals, LW engages in ethnographic practices, which, at the intersection of objectivity and subjectivity, participation and distance, pleasure and truth, involve “[t]he ethnographer's personal experiences, especially those of participation and empathy, [which] are recognized as central to the research process, but [...] are firmly restrained by the impersonal standards of observation and ‘objective’ distance” (Clifford, 1986, p. 13). In this sense, the game is an ethnography of depression as much as a site for ethnographic writing in that the participation of the player is required and thematized itself. In conjunction with the game, a skilled ethnographic player-body is produced together with the field that confronts and challenges it. Scrutinizing ethnography as a kind of writing rather than a one-to-one representation of reality, Clifford holds that “[e]ven the best ethnographic texts -- serious, true fictions -- are systems, or economies, of truth. Power and history work through them, in ways their authors cannot fully control” (p. 7). A “serious, true fiction” is negotiated in gameplay, whereas writer/text/meaning relations continuously come into being in the unfolding power relations. Even the narrative voice, though monolithic, is a shifting source when confronted with the narrative visuality of the site and the mediated agency of its real place. Together with the player, the game thus processually allows for, refuses, directs, distributes, re/places, displaces, bridges and collapses attention and meaning. It makes spaces for becoming-self-aware and distracted slipping elsewhere, all as the ensemble player/game performatively engages in ethnographic writing on its digital walk.

In relation to the interplay of space and mind, the game’s visual-spatial composition links depression to two distinct instances of mindspacing. The first occurs in the opening scene, where external space is almost entirely erased. Depression is rendered as a direct, affective image: a collapsed human body enveloped in a black cloud. It is only through the presence of orienting white footprints that space preserves a rudimentary character: no longer containing or extending, space establishes an initial experiential relation between the player and the phenomenon of depression. Space appears neither as a container nor an extension but relation; via the image of depression, the mind appears as the affective matrix of space, beyond metaphoric distinctions between inside and outside. In the second, longer presentation of its world, LW explores the oscillation between documenting and fragmenting socio-mental space. Its presentation of an actual geographic place affected by suicide, as well as the visual fragmentation of the graphics, thus intimately links, rather than subjugates, the spatial to the mental.

The sonic mindspacing of the ethnographic interview frames depression as an “invisible illness,” problematizing its observability in an attempt to raise awareness: the voice says “if I had a broken leg and it was in a plaster, it’s obvious… But because I’ve got a broken head, it’s not obvious to see that I’m ill.” The account thus strategically maps an inside-outside dichotomy of observability onto the register of the body. Furthermore, the recorded footage links depression to the social world by referring to “a build-up of stress and work, and expectations at work” as well as the self-perception of not being good enough.

Finally, visuality and sound together produce resonances that speak to the mental aspects of space as well as the spatial aspects of mind. For instance, the game visualizes a broken-down car at the moment when the voice recounts breaking down while driving and then shows the curled-up body that the voice pictures. At another moment, the game overlays the sound of crashing waves while the interviewee describes a walk by the beach. The most obvious combination of sound and visuals for the sake of mindspacing is the central theme of walking, mirroring the therapeutic effects of taking time for oneself, which the interviewee advocates. Whereas the other two titles examined in this article place the player in the roles of their protagonists, the ethnographic approach to mindspacing in LW gives space to a single micro-narrative of a person’s experience of living with depression, and the player is enabled to relate to and move with it.

4.3. The Psychotic Bathtub (2024)

The Psychotic Bathtub (PB) is an indie project dealing with psychosis [7], bath time, self-care, guilt, loss and rubber ducks. Although the game has not yet been released, its playable demo features extended gameplay and multiple endings. Like SP, it situates its themes amidst the eventful details and surprising depths of mundane and daily life: Ophelia, the main character, lives through a plethora of memories, fantasies and psychotic experiences and explores the vastness of her mind -- all while taking a bath.

Figure 8. Ophelia, the main character of The Psychotic Bathtub, taking her bath. Click image to enlarge.

The first moment of gameplay confronts the player with two closed eyes. The player-character can either dwell in darkness or open these eyes, which reveals Ophelia sitting in her bathtub (fig. 8). PB chooses an everyday situation and a heavily focalized main character (who is closely coupled with the player) to thematize her mind, its idiosyncrasies and challenges. As with SP, the player is positioned through choices and addressed through a combination of images and text. The textual elements address the player in the second person singular and via the register of the body: when the eyes are opened in the first choice, the screen says, “there is a scratching at the inside of your skull.”

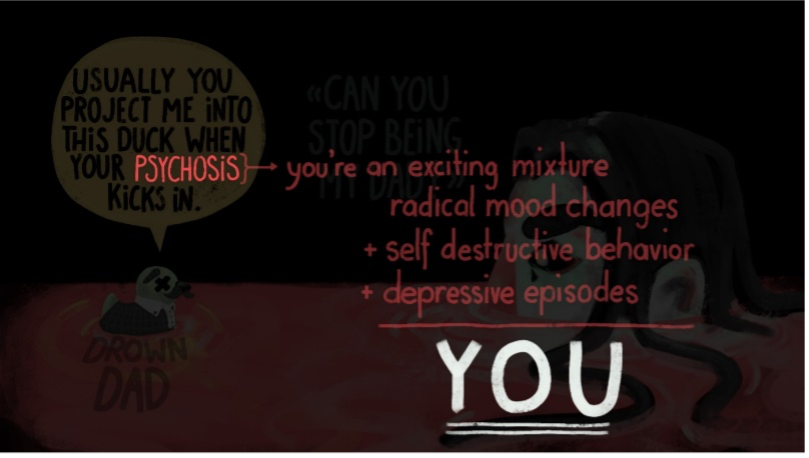

Figure 9. The game links Ophelia’s self-concept to clinical terminology. Click image to enlarge.

The game communicates to the player that the player-character is living with particular mental conditions. In a particularly striking moment, Ophelia speaks to her rubber duck, which suddenly turns into her father. Here, the game draws a direct link between what is happening, the term “psychosis,” and the player-character (fig. 9). This explicit reference to clinical discourse is combined with affective color, language and images that involve the player in a surreal phenomenology of Ophelia’s experiences. Frequent sensory-related language affords the embodiment and identification of the player: when the player-character drinks from her glass, they feel how “desperation rushes through every fiber of you. Something freezing covers the inside of your ribcage.” The game’s sound design accentuates its visual elements, adding details like a pouring sound of water when a new game is started or gulping sounds indicating when the player-character is drinking. Additionally, subjective ambient sounds affect the mood of play, such as in one situation when fear and danger are signaled by a menacing buzzing that escalates into the shrieking sounds of a distorted guitar.

The positioning of the player in the midst of the affective, perceptive and associative web of relations that make up Ophelia’s experience is closely tied to the game’s imaginary of play. The former is asked and allowed to explore rather than conquer, to be open to surprise rather than see my hypotheses and expectations realized to reap rewards, and to relate to the main character in a myriad of ways, from wanting to get to know her, to communicating with her, caring for her, turning away from her or even harming her. The player may be as mischievous or supportive as the prepared paths of the game allow. In one ending, Ophelia gets swallowed by the darkness of her mind. In another, she falls in love with death. In a third, she floods the bathroom, creating a red sea (with a bubble bath rather than blood causing the red color). In most playthroughs, however, the player-character’s actions crystallize to the “peace of mind” ending, in which a “long desired silence” is achieved. The game’s invitation to play multiple times foregrounds the unknowable and the unexpected as experiential forces that register on the body in play. The myriad options are a direct analogy for the multiplicity of the main character’s mind. Some twists, turns and themes are particularly dark: Ophelia finds opportunities to face her thoughts on death, disability, her recently passed-away father, childhood memories and anxieties all in the very here-and-now of the bath itself. While the game usually gives alternative options and sympathetically foreshadows these darker and sometimes downright scary themes (by asking the player to insist on a given line of choice), PB also does not shy away from them. Through this meta-communication, the game allows a negotiation of the limits of play, offering a site to counter or reinstall the normative expectation that games ought to be entertaining and fun.

Figure 10. Grape Juice or poison? Choosing between two realities? Click image to enlarge.

As the framing of the main “peace of mind” ending discloses, the concept of the mind is played with just as much as much as Ophelia’s personality -- a shifting sum of embodied memories, thoughts, feelings, perceptions, actions and ways of relating. Hence, mindspacing takes center stage in the unfolding of play in PB. Regarding the procedural genesis of the game’s spatiality, there is a constant chaotic interweaving of linguistic and visual material, a ruptured metamorphogenesis that leaps from one moment to the next via wild associations, which creates rather than discovers reality: what is in Ophelia’s cup? Grape juice or poison (fig. 10) -- the player may follow either thought as it becomes the next building block of reality. Depending on the procedural paths the player follows, the rubber duck in the bathtub may turn into Ophelia’s dead father, a mix of her father and the duck, or Jesus. The three versions of the duck, however, are not just shown as temporary distortions but as three lasting versions of reality; they do not change again during a playthrough.

Hence, the game prepares the ongoing processual genesis of space in play in a manner akin to what Jameson (2002) describes as “schizophrenic writing” (p. 33). Schizophrenic art and experiences, he argues via Lacan, involve a “breakdown in the signifying chain” (p. 33). Lacan’s account of meaning points to the movement from signifier to signifier rather than a direct one-to-one relationship between signifier and signified; meaning, according to Jameson’s reading, is generated as a “meaning-effect” (p. 33). “When that relationship breaks down,” he argues, “when the links of the signifying chain snap, then we have schizophrenia in the form of a rubble of distinct and unrelated signifiers”:

The connection between this [...] linguistic malfunction and the psyche of the schizophrenic may then be grasped by way of a two-fold proposition: first, that personal identity is itself the effect of a certain temporal unification of past and future with one’s present; and second, that such active temporal unification is itself a function of language, or better still of the sentence [. . .]. If we are unable to unify the past, present and future of the sentence, then we are similarly unable to unify the past, present, and future of our own biographical experience or psychic life. With the breakdown of the signifying chain, therefore, the schizophrenic is reduced to an experience of pure material signifiers [...]. (p. 33)

In the game, what is usually distinguished as material/semiotic, physical/mental, form/meaning, signifier/signified or thing/word exists on the same plane as a kind of flat materiality, co-positioning image and text without establishing a relation of depth between them. The player thus witnesses and practices a materiality without anchors, floating and adrift. In this “experience of pure material signifiers,” the player/game couple does not just trace but also exerts the narrative and territorializing function of the mind (at play with) itself. The player/game negotiates between a becoming-schizophrenic and a becoming-unschizophrenic, i.e. creative disintegration and therapeutic attempts to re-link the floating signifiers/experiences: does Ophelia face the death of her father, or drown the father-duck in the red floods of her bath? Does she deny death or fall in love with it? Does she reconcile her guilt or claim to be Jesus?

How then do the game’s practices of mindspacing position the mental and the spatial? The task of opening the closed eyes conveys a first aspect. Through Ophelia’s exchange with her inner voice, the game considers the possibility of the mind as an inner realm, secluded but whole. If the player pursues the option of separating the inside from the outside (keeping one’s eyes closed), the game ends the playthrough: Ophelia’s mind becomes impossible and she dies. When the player-character chooses to open the eyes and see the world, however, the experience of schizophrenic chains of meaning cannot be mapped onto a matrix that would distinguish the interior from the exterior. While the game initially appears to present an objective world through the static image of Ophelia in the bathtub, which is the player’s point of departure for interacting with the surroundings, the player’s interactions change this reality in lasting ways. The playful negotiation of spatiality is a negotiation of the physical and the mental, the exterior and the interior. What is explored in the various metamorphoses is the mind as the very place through which the shifting sum of logics of association, emotional-cognitive preoccupations, passing sensations, impressions and their libidinous occupations, attracting and repelling forces, their rhythms and affective powers, links, breaks, alliances and oppositions, come to be.

In this way, PB does not portray the psyche as a container (the place in which psychic spatiality would reflect the outside) but rather as an ongoing formation of psychic spatiality in which the body is pre-individually caught up in power dynamics, meaning and micro-forces that precede the psyche or mind itself. In short, the psyche is not a container in which life is reflected but (via the creation of psychic spatiality) an effect and expression of life (and lived play) itself -- very much in contrast to the subtitle of the game, “a story of an escalating mind.” Hence, the closed eyes signify the death of the psyche, as no psychic life is possible without a world to animate it.

5. Conclusion: Indie Games as Discursive Counterspaces and Play as Care of the Self

There is a severe gap in the literature on indie games and their potential role in mental health depiction and demarginalization. Drawing up a widely applicable and yet specific perspective of mindspacing, this article has offered a series of qualitative case studies that illuminate how indie games can reshape dominant narratives around mental illness.

In response to the first guiding question, I argue that a common strategy between these selected games is narrative individualization -- that is, making mental health phenomena intelligible via characterization in specific historico-social situations. However, different strategies of narrative individualization are deployed. They all offer strong focalization through their protagonists, who often directly verbalize and reflect upon their own experience (SP, PB). Beyond this, documentary practices (LW) offer an alternative. Further recurring strategies include the direct addressing of the player (via phenomenologically embodied and situated knowledges) and the depiction of everyday situations (SP, PB), which make mental health phenomena tangible by placing them amid personal and private spaces.

Secondly, the games’ imaginaries of play range from the reduction of game mechanics (LW) and the disabling of the player (SP) for expressive effects, to affording her the agency to profoundly shape the game world (PB). A recurring element is the presence of choice segments that, while seemingly trivial, vitally contribute to the games’ endings (SP, PB). Moreover, all three titles share a capacity to enable and afford new, intimate modes of relating through and in play. In this regard, their ludic design pointedly resists the tyranny of fun, or the normative expectation that discourages games from addressing mental health topics. Challenging hegemonic notions of player agency, narrations of progress and the overrepresentation of positive emotions, the titles analyzed reimagine play as painful, scary and dark (PB), existential (SP), or as a struggle for balance, healing and growth (LW, PB).

The final question of mindspacing finds a compelling answer in how games link mental experience to spatial configuration. Most notably, the games move beyond inside-outside dualisms, either to make tangible the shared responsibility emerging from the socio-mental complex (SP), give micronarratives of mental illness an expressive space (LW), or to creatively reimagine our means of presentation as required by the depicted phenomenon (PB). The analyzed titles thus present the mind/psyche as something more than a mere container or medium of reflection of an outside world. Rather, they afford moments of mindspacing that problematize the privatization of mental health and the objectification of space, both of which mask the embodied and positioned intimacy that emerges from the sharedness of lived social spaces and places. The resulting non-demarcation and linkage of the spatial and the mental can happen in creative modes of expression (PB) or to raise awareness and give presence (SP, LW). While the games analyzed here focus on psychic spatiality, they feature psychological terminology -- for example, clinical diagnoses in PB or the therapeutic vocabulary used in LW. The titles are thus somewhat shaped by institutional discourse, but it is notable that they largely avoid thematizing (and with it, commenting on) the institutional side of mental health. This choice could well be part of a more general and deliberate attempt to bypass narratives of accuracy and institutional legitimacy in times of increasing psychiatrization (Beeker et al., 2021).

A final remark on the concept of mindspacing: whereas current research on games is primarily interested in “how mental health and illness [are] articulated in these media spaces” (Dunlap & Kowert, 2025, p. 123), the present work has developed a less representational perspective on the spatiality of games in the context of mental health. Together with the rich and multi-faceted portrayals by games like PB, the present perspective may contribute to an understanding of space not just as an expressive container but as a matrix of the mental (and vice versa). In the context of the Western opposition between outer space and inner mind, mindspacing pushes back against the naturalizing and internalizing tendencies of mental health discourse, which also permeate the discourse on games and representation.

Drawing the findings together, the indie games discussed here can be described as discursive “counterspaces” (Cruz, 2022, p. 316) in the context of de/marginalization and mental health. Their imaginaries of play are marked by the struggle to both address marginalized groups, positions and experiences. They creatively reimagine hegemonic forms of play, which ongoingly contribute to said marginalization in other contemporary games but also wider socio-cultural discourses of play (including the academy). In this regard, the titles convincingly challenge Sicart’s notion that “it is in play, and not in games, where politics resides” (2014, p. 73). Their depictions are certainly negotiated in play, but the way the titles reimagine, sometimes tease and frustrate hegemonic notions of play (such as a game being winnable or the apotheosis of player agency and telic progress) is as profoundly critical as it is political, and testifies to the capabilities of indie games’ discursive intertextuality. Instead of these tropes, these games negotiate Bateson’s question “Is this play?” (1972, p. 141) with the player in an attempt to enable her to reimagine the shape and character of play.

The indie games examined here use differing paths to shift the focus from entertainment and reproduction to cultivating new modes of relating. Involving the player in unexpected and uneasy entanglements, they resist the tyranny of fun and move away from the common patronization of the player to instead give space to a fuller range of emotions and themes. The manner in which they enable the player to experience new insights, pains and experiences of being baffled, challenged and disabled, they can be described as moving play closer to what can be called practices of the care of the self or the arts of existence per Foucault (1988) [8]. The games discussed foster play as an art of existence through a care of the self, which is a care for the Other. They enact entanglements that are shaped by Lugones’s close coupling of play with a “loving attitude in travelling across worlds” (1987, pp. 14-15). Demarginalization, as the games practice it, is impossible without a change in one’s own existence. Together with these titles, the player may affirm play as a mutual enabling to be and a shared search for novel ways of relating. The titles thus foreground play as a lived and embodied site of cultural negotiation that can change the very categories through which our minds grasp our existence and participate in the spatialization and mentalization of our shared modes of being in the world. By participating in such counterspaces in play, we may activate the games’ capacities not to subject but to subjectify, to enable us to cultivate our ways and willingness to reach out, and, thus, to share and foster novel demarginalizing and empowering impulses beyond play.

Acknowledgements

Note that this essay reworks material first developed in my doctoral dissertation, later published as Playing Place.

Endnotes

[1] Garda and Grabarczyk (2016) regard today’s category of the indie game as a subset of a larger category of independent games, which are marked by financial, creative and publishing independence. The more specific and yet also more prominent term indie game, according to the authors, relates to a combination of several features of a game and its creation: digital distribution, experimental nature, small budget and low price, its retro style, small size, small developing team, indie mindset (marked by an alleged independence from practices and ideologies from the game industry and an idea of the designer as closer to the player), the indie scene, and the role of middleware (i.e., accessible game engines and design tools).

[2] Following Reckwitz’s take on an “ideal type of practice theory” (2002, p. 244), we can think of a practice as “a routinized type of behaviour which consists of several elements, interconnected to one other: forms of bodily activities, forms of mental activities, ‘things’ and their use, a background knowledge in the form of understanding, know-how, states of emotion and motivational knowledge” (p. 249). Since practice theory questions mentalism’s theory of “mind as an ontological realm of the ‘inner’ which is distinct from outward behaviour and is at the same time its cause” (p. 252), it is a particularly fruitful conceptual framework to question visual discourses of the mind and mental health.

[3] Within the discourse of new formalism, Marjorie Levinson distinguishes between an ongoing commitment to form, which she describes as “activist,” and a second type of “normative formalism” that advocates a “sharp demarcation between history and art” (2007, p. 559). For the latter, form determines the literary status and can be regarded as an integral property of the work itself. Activist formalism, on the other hand, holds that form matters -- in relation to literary works but also wider discourses -- because it constitutes what may count as real in the first place.

[4] All three titles selected can be described as indie games according to Garda and Grabarczyk (2016). Following their set of contingent features, the titles are digitally distributed, of experimental nature, feature a small budget, low price and a small developing team, are of small size, express a certain indie mindset, bear ties to the indie scene and use middleware. Besides qualifying as indie games, the titles were selected since they specifically address topics of mental health and mental illness. Furthermore, games were preferred that gave a fuller account of the phenomena at hand and have not yet been examined closely by previous research.

[5] Note that the invisibility of the player-character also strategically refuses to describe them via a particular constellation of sex/gender, which is significant because eating disorders (including anorexia nervosa) are often framed as female illnesses, whereas a fourth of people affected are men (Murnen and Smolak, 2015).

[6] In line with this, the creator of the game wrote in a description on Steam: “Whilst my father's experience and the locations depicted in the game are specific to him, the thoughts, feelings, and message conveyed through his recollection of lived experience are universal” (Tarvet, 2020).

[7] Generally, the term psychosis denotes difficulties in determining what is real and what is not, and thus refers to phenomena such as delusions and hallucinations as well as disorganized behavior, speech, and thought. Note that in a clinical context, the term is no longer used to designate a distinct diagnosis in DSM-5 and ICD-11. Rather, psychosis can be part of the symptom clusters of several diagnoses such as schizophrenia, bipolar and affective disorders, substance misuse, and others, with many different possible underlying factors (from mental illness and medical conditions to trauma, sleep deprivation, drugs and others).

[8] See: “[A] group of practices that have been of unquestionable importance in our societies: I am referring to what might be called the “arts of existence.” [...] [T]hose intentional and voluntary actions by which men not only set themselves rules of conduct, but also seek to transform themselves, to change themselves in their singular being, and to make their life into an oeuvre that carries certain aesthetic values and meets certain stylistic criteria” (Foucault, 1988, pp. 10-11).

References

Anable, A. (2018). Playing with Feelings. Video Games and Affect. University of Minnesota Press.

Anderson, S. L. (2020). Portraying Mental Illness in Video Games: Exploratory Case Studies for Improving Interactive Depictions. Loading, 13(21), 20-33. https://doi.org/10.7202/1071449ar

Austin, J. (2021). “The hardest battles are fought in the mind”: Representations of Mental Illness in Ninja Theory’s Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice. Game Studies, 21(4). https://gamestudies.org/2104/articles/austin

Bateson, G. (1972). A Theory of Game and Fantasy. In Steps to an Ecology of the Mind (pp. 138-148). Chandler Publishing.

Bedtime Phobias (v.2018.1.0.20514, 2018). Shrinking Pains [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game published by Bedtime Phobias.

Beeker, T., Mills, C., Bhugra, D., te Meerman, S., Thoma, S., Heinze, M., & von Peter, S. (2021). Psychiatrization of Society: A Conceptual Framework and Call for Transdisciplinary Research. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.645556

Bogost, I. (2006). Unit Operations: An Approach to Videogame Criticism. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/6997.001.0001

Bogost, I. (2007). Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. MIT Press.

Buday, J., Neumann, M., Heidingerová, J., Michalec, J., Podgorná, G., Mareš, T., Pol, M., Mahrík, J., Vranková, S., Kališová, L., & Anders, M. (2022). Depiction of mental illness and psychiatry in popular video games over the last 20 years. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13.

Chang, A. Y. (2011). Games as Environmental Texts. Qui Parle, 19(2), 56-84. https://doi.org/10.5250/quiparle.19.2.0057

Clarke, M. J., & Wang, C. (2020). Indie Games in the Digital Age. Bloomsbury.

Clifford, J. (1986). Introduction: Partial Truths. In J. Clifford & G. E. Marcus (Eds.), Writing Culture. The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography (pp. 1-26). California UP.

Cruz, E. P. (2022). Counterspace Game Elements for This Pansexual Pilipina American Player’s Joy, Rest, and Healing: An Autoethnographic Case Study of Playing Stardew Valley. Gamevironments, 17, Article 17. https://doi.org/10.48783/gameviron.v17i17.193

Double Fine Productions (v.1087071, 2021). Psychonauts 2 [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game designed by Seth Marinello and Zak McClendon, published by Xbox Game Studios.

Dunlap, K., & Kowert, R. (2021). Mental Health in 3D: A Dimensional Model of Mental Illness Representation in Digital Games. Loading: The Journal of the Canadian Game Studies Association, 14(24), 122-133. https://doi.org/10.7202/1084842ar

Dunlap, K., & Kowert, R. (2025). The Monstrosity of Stigma: Mental Health Representation in Video Games. In S. Stang, M. Meriläinen, J. Blom, & L. Hassan (Eds.), Monstrosity in Games and Play: A Multidisciplinary Examination of the Monstrous in Contemporary Cultures (pp. 121-140). Amsterdam University Press. doi.org/10.1515/9789048556632-007

Dyer-Witheford, N., & de Peuter, G. (2009). Games of Empire. Global Capitalism and Video Games. Minnesota UP.

Eisenhauer, J. (2008). A Visual Culture of Stigma: Critically Examining Representations of Mental Illness. Art Education, 61(5), 13-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043125.2008.11518991

Ferrari, M., McIlwaine, S. V., Jordan, G., Shah, J. L., Lal, S., & Iyer, S. N. (2019). Gaming With Stigma: Analysis of Messages About Mental Illnesses in Video Games. JMIR Mental Health, 6(5), e12418. https://doi.org/10.2196/12418

Flanagan, M. (2009). Critical Play: Radical Game Design. The MIT Press.

Foucault, M. (1988). The Use of Pleausure. Volume 2 of the History of Sexuality. (R. Hurley, Trans.). Vintage Books.

Gadamer, H.-G. (2004). Truth and Method (J. Weinsheimer & D. G. Marshall, Trans.; 2nd, rev. ed.). Continuum.

Garda, M. B., & Grabarczyk, P. (2016). Is Every Indie Game Independent? Towards the Concept of Independent Game. Game Studies, 16(1). https://gamestudies.org/1601/articles/gardagrabarczyk

Gilman, S. L. (1982). Seeing the Insane: A Cultural History of Madness and Art in the Western World. Nebraska UP.

Goggin, J. (2011). Playbour, farming and leisure. Ephemera, 11(4), 357-368.

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575-599.

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

Harrer, S. (2018). Casual Empire: Video Games as Neocolonial Praxis. Open Library of Humanities, 4(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.16995/olh.210

Hyler, S. E. (1988). DSM-III at the cinema: Madness in the movies. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 29(2), 195-206. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-440X(88)90014-4

Hyler, S. E., Gabbard, G. O., & Schneider, I. (1991). Homicidal Maniacs and Narcissistic Parasites: Stigmatization of Mentally Ill Persons in the Movies. Psychiatric Services, 42(10), 1044-1048. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.42.10.1044

Jameson, F. (2002). The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. In B. Nicol (Ed.), Postmodernism and the Contemporary Novel (pp. 20-39). Edinburgh UP.

Kasdorf, R. (2023). Representation of mental illness in video games beyond stigmatization. Frontiers in Human Dynamics, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2023.1155821

Keogh, B. (2014). Across Worlds and Bodies: Criticism in the Age of Video Games. Journal of Games Criticism, 1(1), 1-26.

King, M., Marsh, T., & Akcay, Z. (2021). A Review of Indie Games for Serious Mental Health Game Design. Joint International Conference on Serious Games, 138-152. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-88272-3_11

Latorre, Ô. P. (2016). Indie or Mainstream? Tensions and Nuances between the Alternative and the Mainstream in Indie Games. Anàlisi, 15-30. https://doi.org/10.7238/a.v0i54.2818

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The Production of Space. Wiley-Blackwell.

Leonard, D. (2003). “Live in Your World, Play in Ours”: Race, Video Games, and Consuming the Other. Simile: Studies in Media & Information Literacy Education, 3, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.3138/sim.3.4.002

Levine, C. (2015). Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Network, Hierarchy. Princeton University Press.

Levinson, M. (2007). What Is New Formalism? PMLA, 122(2), 558-569.

Lugones, M. (1987). Playfulness, “World”-Travelling, and Loving Perception. Hypatia, 2(2), 3-19.

Meinel, D. (2022). Video Games and Spatiality in American Studies: An Introduction. In D. Meinel (Ed.), Video Games and Spatiality in American Studies (pp. 1-32). De Gruyter.

Mittmann, G., Steiner-Hofbauer, V., Dorczok, M. C., & Schrank, B. (2024). A scoping review about the portrayal of mental illness in commercial video games. Current Psychology, 43(39), 30873-30881. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06679-x

Morris, G., & Forrest, R. (2013). Wham, sock, kapow! Can Batman defeat his biggest foe yet and combat mental health discrimination? An exploration of the video games industry and its potential for health promotion. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 20(8), 752-760. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12055

Murray, J. H. (2016). Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. The Free Press.

Murray, S. (2018). On Video Games: The Visual Politics of Race, Gender and Space. I.B. Tauris.

Natsha (demo v. 2021.3.18.10726, 2024). Psychotic Bathtub [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game published by Natsha.

Nguyen, A.-T. (2022). Mindspaces: The Mind as a Visual and Ludic Artifact. In J. Aguilar Rodríguez, F. Alvarez Igarzábal, M. S. Debus, C. L. Maughan, S.-J. Song, M. Vozaru, & F. Zimmermann (Eds.), Bild und Bit. Studien zur digitalen Medienkultur (1st ed., Vol. 15, pp. 51-62). transcript Verlag.

Nordahl-Hansen, A., Tøndevold, M., & Fletcher-Watson, S. (2018). Mental health on screen: A DSM-5 dissection of portrayals of autism spectrum disorders in film and TV. Psychiatry Research, 262, 351-353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.08.050

Parker, F. (2014). Indie Game Studies Year Eleven. Proceedings of the 2013 DiGRA International Conference: Defragging Game Studies, Vol. 7. http://www.digra.org/digital-library/publications/indie-game-studies-year-eleven/

Pirkis, J., Blood, R. W., Francis, C., & McCallum, K. (2006). On-Screen Portrayals of Mental Illness: Extent, Nature, and Impacts. Journal of Health Communication, 11(5), 523-541. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730600755889

Reckwitz, A. (2002). Toward a Theory of Social Practices: A Development in Culturalist Theorizing. European Journal of Social Theory, 5(2), 243-263. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684310222225432

Riles, J. M., Miller, B., Funk, M., & Morrow, E. (2021). The Modern Character of Mental Health Stigma: A 30-Year Examination of Popular Film. Communication Studies, 72(4), 668-683. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2021.1953098

Ruberg, B. (2020). Straight Paths Through Queer Walking Simulators: Wandering on Rails and Speedrunning in Gone Home. Games and Culture, 15(6), 632-652. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412019826746

Schlote, E., & Major, A. (2021). Playing with Mental Issues -- Entertaining Video Games as a Means for Mental Health Education? Digital Culture & Education, 13(2), 94-110.

Shapiro, S., & Rotter, M. (2016). Graphic Depictions: Portrayals of Mental Illness in Video Games. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 61(6), 1592-1595. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.13214

Sicart, M. (2011). Against Procedurality. Game Studies, 11(3). http://gamestudies.org/1103/articles/sicart_ap

Sicart, M. (2014). Play Matters. The MIT Press.

Sicart, M. (2022). Playthings. Games and Culture, 17(1), 140-155. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120211020380

Stenros, J. (2018). Guided by Transgression: Defying Norms as an Integral Part of Play. In K. Jørgensen & F. Karlsen (Eds.), Transgression in games and play (pp. 13-25). The MIT Press.

Stuart, H. (2006). Media Portrayal of Mental Illness and its Treatments. CNS Drugs, 20(2), 99-106. https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200620020-00002

Tarvet, A. (v.4.24.3.0, 2022). The Longest Walk [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Alexander Tarvet, published by Somewhat Unsettling / Abertay Game Lab.

Tarvet, A. (2024, February 2). The Longest Walk on Steam. Steam Store. https://store.steampowered.com/app/2111060/The_Longest_Walk/

Wahl, O. F. (1995). Media Madness: Public Images of Mental Illness. Rutgers UP.

Winnicott, D. W. (2005). Playing and Reality. Routledge Classics.

Wischert-Zielke, M. (2024). Rethinking playfulness: Things, bodies, and ideas as play partners and their agency in mediated sex, kink, and BDSM spaces. International Journal of Play, 13(1), 90-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2024.2323418

Wischert-Zielke, M. (2025). Playing Place -- On Digital Games, Spatiality, and Hegemonic Play [Dissertation, Katholische Universität Eichstätt-Ingolstadt]. https://doi.org/10.17904/ku.opus-987