Playing with the Dead: Dead Pools and the case of Fantamorto

by Stefano GualeniAbstract

Dead people can take part in gameplay. These playful possibilities reflect two broad trends in the social perception of human finitude: death acceptance and death denial. Some of the playful practices discussed in this article align with perspectives that regard mortality as a foundational -- and even affirmative -- aspect of human existence. These are games and videogames designed to sustain a sense of continuity and familiarity with the departed. Other games adopt a more antagonistic stance toward the dead, trivializing and commodifying their personal and historical significance. Among the latter, this article devotes particular attention to a family of playful practices known as “dead pool games,” playful folk phenomena that have thus far been overlooked within game studies.

Foregrounding the representational and ethical stakes of playing with the dead, the second half of the article traces the historical development of dead pool games and examines the ethically contentious design decisions that shape this genre. The inquiry culminates in an ethics-oriented analysis of the gameplay and design of Fantamorto -- a popular contemporary Italian instantiation of the dead pool game formula, with particular attention to how its rules frame death and human suffering as ludic resources within a competitive game economy.

Keywords: death, death studies, dead pool, dead pool games, existentialism, Fantamorto, Fantapapa, game design, chatbots, grief, mimetic models

1. Introduction

Across cultures and traditions, human beings relate to the themes of mortality and death in ambiguous ways (Mellor & Shilling, 1993). This ambivalence is particularly evident in how social groups have historically both revered and lampooned the dead. On the one hand, rituals such as funerals and memorials invite us to conceive of the deceased as inhabiting a sacred or spiritual realm, clearly separated from the deeds and concerns of the living. On the other hand, cross-cultural traditions continue to portray the dead as active participants in the social world, often in friendly and mischievous roles. Examples of this can be found in the late-medieval European allegory of the Danse Macabre and in the playful celebrations of Día de los Muertos in Mexico.

This article explores the possibility of establishing ludic relationships with people who are actually dead. In tackling this apparently paradoxical (and potentially contentious) topic, I will make use of conceptual perspectives developed in scholarly fields such as death studies, philosophical anthropology and existential philosophy. Discussing the roles and involvement of the deceased in playful activities, this introduction presents the cultural ambivalence surrounding death as an aspect of our relationship with our own finitude.

In a 2019 book chapter titled “Facing Death: A Sartrean Perspective on the Contemporary Tendency to Over-Humanize Death,” comparative literature scholar Adriana Teodorescu identifies two opposing tendencies in the social perception of death: one advocating for its demystification and social acceptance, and the other bent on resisting and defying death. According to Teodorescu, most contemporary publications in death studies focus on rediscovering death as an ordinary (and even positive) phenomenon, after centuries in which the dominant approach to mortality was one of denial and cultural interdiction (cf. the concept of the “forbidden death” in Ariés 1974). This contemporary death-embracing perspective has, for Teodorescu, obvious roots in existential philosophy (e.g., Heidegger 1927; Levinas 1992), and it acknowledges the awareness of our own mortality as a central, defining aspect of what it is to be human. According to this approach, our finitude is not only understood as something perfectly natural, but also as a necessary source of existential meaning. Acknowledging death should not, then, be regarded as something untactful or be sequestered from public discourse under taboo-like interdictions. It should, instead, be celebrated as the ultimate foundation for every human activity. In a similar fashion, philosophical anthropologists like Arnold Gehlen and Helmuth Plessner famously regarded humankind as the species who is conscious of the finitude of its existence, and identified in this awareness the ultimate reason behind our inherent (and inexhaustible) aspiration towards meaning and fulfilment [1].

In Teodorescu’s text, the perspective outlined above is countered by a de-humanizing and anti-celebratory pattern of conceptualizing death: a neo-Epicurean perspective according to which life and death are mutually exclusive, and existential meaning can only emerge while being alive (i.e., not after one’s death). We owe the contemporary formulation of this approach to the work of Jean-Paul Sartre. In the parts of his texts that deal with the theme of mortality, Sartre presents the relationship between human beings and death as irredeemably conflictual. For the French philosopher, we do not shape our existence around the awareness of our own mortality (i.e., what Heidegger labelled as our being-towards-death [1962, pp. 279-281]), but rather in opposition to it. In other words, for Sartre our mode of existence is better characterized as being-against-death (Teodorescu, 2019, p. 99). The French philosopher argues, in fact, that there is nothing we can learn from death, and no way to benefit from it. All death can do, he wrote, is “remove all meaning from life” (Sartre, 1943, p. 539). From his standpoint, rather than being viable strategies for dealing with the idea of our finitude, our attempts to humanize death and cast a positive light on it are akin to symptoms of Stockholm syndrome (1962, p. 542). Consequently, and as an alternative to this paradigm, Sartre encourages us to take a deliberately indifferent perspective towards death, and to even ridicule it (ibid.).

In line with these two opposing attitudes towards death -- one embracing death as a source of existential meaning and the other rejecting it -- the following section of this article discusses the idea and possibility of “playing with the dead” along two approaches. In the context of play, the dead can either

- participate as players (as subjects in play, 2.1), or

- serve as elements of the game (as objects of play, 2.2).

The first approach treats the dead as subjects in play and aligns with an embracing and humanizing perspective on finitude. This kind of ludic engagement with the dead typically aims at fostering a continuing sense of familiarity and relatedness with the departed and aligns with what Krueger and Osler described as practices of “communing with the dead” (2022).

The second way of “playing with the dead” proposes a different perspective, one that will take center stage in this article, one that makes use of the dead -- or, rather, their fictional representations -- as playthings. This second approach objectifies the departed and treats dying as a mere cultural fact without inherent emotional or existential significance. As already outlined, this second approach resonates with Sartre’s conviction that life draws its meaning from being lived, and that one has the right to remain indifferent to the topic of death and uninterested in trying to manage it or humanize it (Teodorescu, 2019, p. 102).

This article will pay particular attention to the second group of playful activities -- that is, forms of play that objectify the dead and take a cynical, and often even flippant, approach to the very notion of death. Belonging to this second category is Fantamorto, a popular (online, Italian) variant of dead pool games that will be examined and discussed as a particularly salient case study in the concluding sections of this article. A detailed analysis of how dead pool games generally frame the themes of human suffering and human mortality is supplemented with ethical considerations concerning the unique design of Fantamorto.

2. Playing with the Dead

2.1 The Dead as Players

In an anecdote that circulated on gaming websites in 2014, a player claimed to have met the ghost of his father in an unlikely place: a videogame for the original Xbox. Under the nickname 00WARTHERAPY00, this player shared his story in the comments section of a PBS video essay about whether video games can qualify as spiritual experiences (PBS Game/Show, 2014). I present his original comment below, preserving its formatting:

Well, when i was 4, my dad bought a trusty XBox. you know, the first, ruggedy, blocky one from 2001. we had tons and tons and tons of fun playing all kinds of games together - until he died, when i was just 6. i couldnt touch that console for 10 years. but once i did, i noticed something. we used to play a racing game, Rally Sports Challenge. actually pretty awesome for the time it came. and once i started meddling around... i found a GHOST. literaly. you know, when a time race happens, that the fastest lap so far gets recorded as a ghost driver? yep, you guessed it - his ghost still rolls around the track today. and so i played and played, and played, untill i was almost able to beat the ghost. until one day i got ahead of it, i surpassed it, and...~ i stopped right in front of the finish line, just to ensure i wouldnt delete it. Bliss

A large portion of Davide Sisto’s 2020 book, Online Afterlives: Immortality, Memory, and Grief in Digital Culture, examines how computers can serve as tools to support us in the grieving process. In his monograph, Sisto examines new forms of “haunting” that are exemplified by everyday encounters with digital traces of the deceased (e.g., social media accounts that remain active after their owner’s death, or automated birthday reminders that continue to appear in online calendars after someone’s passing).

Building on Sisto’s work, the aforementioned essay by Krueger and Osler specifically focuses on the idea that computer-mediated grieving does not necessarily need to be a passive experience. As exemplified in the story of 00WARTHERAPY00, establishing and cultivating digital relationships with the dead can also take forms that are active and interactive [2]. In their essay, Krueger and Osler find it revelatory that, in December 2020, Microsoft was granted a patent for a method of creating conversational AI chatbots that are trained to speak and sound like specific people, “such as a friend, a relative, an acquaintance, a celebrity, a fictional character, a historical figure” (United States Patent and Trademark Office, Patent US-010853717-B2).

Whether personal data and digital traces are used to construct “digital ghosts” or for analytical purposes, their deployment raises persistent ethical concerns -- especially when such records are collected or processed without the full and explicit consent of those involved. These concerns have been widely discussed in techno-ethics and the philosophy of technology (cf. Floridi, 2015; Nguyen et al., 2022). More specific death-related anxieties about training artificially intelligent chatbots on personal data are articulated in the closing chapter of the already-mentioned Online Afterlives: Immortality, Memory, and Grief in Digital Culture (Sisto, 2020) and in Patrick Stokes’s Digital Souls: A Philosophy of Online Death (2021). Even more to the point, Reid McIlroy-Young et al. examined the possibilities and challenges of modeling artificial agents (referred to as “mimetic models” [3]) based on digital records of individuals (2022a). Related studies by the same team (2021; 2022b) specifically focus on chess as a context of application for mimetic modeling, investigating how the recorded games of a particular player can be used to procedurally replicate that player’s playstyle. This research implies the possibility of (metaphorically) reviving chess players such as legendary grandmasters Bobby Fischer or Vera Menchik from the “ashes” of their recorded chess games. The ethical viability and the legal implications of this way of training mimetic models are, however, not addressed in the work of Reid McIlroy-Young et al. [4].

The possibility of modelling artificial players on the dead raises obvious questions concerning the ownership of one’s digital traces, and about how we currently conceptualize personhood and its duration. These questions have become even more pressing in recent years, with the technological opportunity to interact with artificially resurrected people that we can not only play with but also converse with (as chatbots trained on interviews and public appearances of the deceased). Before the advent of mimetic models and AI chatbots, similar anxieties and concerns were highlighted in works of science fiction. Novels such as David Brin’s Kiln People (2002), Vernor Vinge’s The Cookie Monster (2003) and Greg Egan’s Zendegi (2010) specifically grapple with the social and ethical implications of generating high-fidelity models of dead individuals. What We Owe the Dead (2025), a speculative sci-fi novel by the author of this article, similarly describes a dystopian future where playful relationships with people can be artificially extended beyond their biological limits, and playing with (and against) dead players is a relatively common occurrence. In that narrative world, ranked players of a popular (fictional) game are resuscitated as cyborgs -- mechanical arthropods whose artificial intelligences interface with (and sustain) the deceased players’ organic brains.

In these fictions, the revival of the dead (as artificially intelligent models or eerie combinations of organic and digital) is presented a way to keep our ancestors actively involved in social processes. In What We Owe the Dead, playing with the dead is explicitly presented as a way to honor specific human players and keep the game alive in the face of an ecological catastrophe and the resulting dwindling human population. As noted earlier, however, not all kinds of ludic interactions with the dead see the deceased as active subjects in play, nor are all those forms of play intended to foster a meaningful personal connection with the dead or to celebrate their accomplishments. The next section of this article examines modes of play that, conversely, desecrate death and treat the departed as mere objects in play.

2.2 The Dead as Playthings

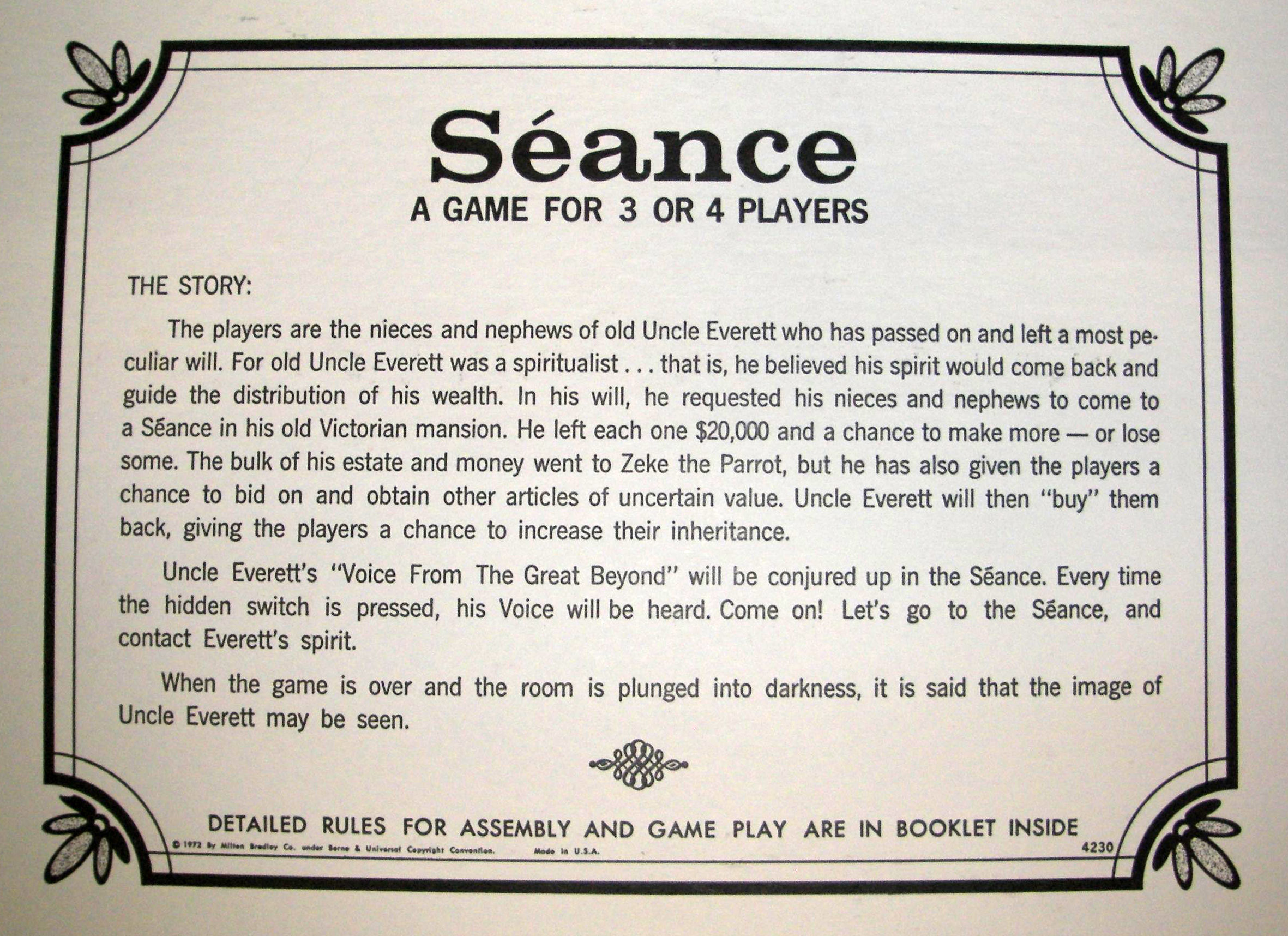

In discussing this second category of ludic relationships with the dead, I will not address the fictional deaths of in-game characters. To clarify, I will not consider cases such as Morris, the recently deceased protagonist of I Am Dead (Hollow Ponds, 2021), or Joel Miller, an NPC who is brutally killed in the opening scenes of The Last of Us Part II (Naughty Dog, 2022), or even Uncle Everett, the fictional dead relative that players are in contact with in the narrative world of the board game Séance (Milton Bradley, 1972; see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The synopsis for the 1972 board game Séance printed on a dedicated card found inside the original box. It offers details and information concerning the peculiar, fictional will left behind by Uncle Everett. Click image to enlarge.

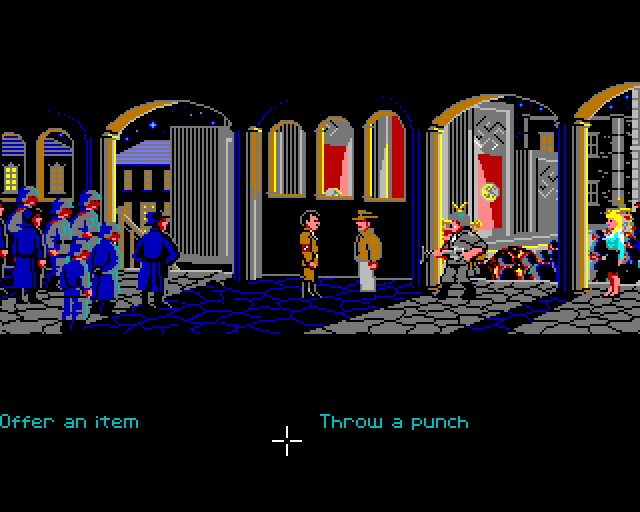

Instead, I will focus on the ludic uses of representations of actual deceased individuals, and on the underlying conceptualization of death that these uses imply. The types of ludic encounters discussed in this section are especially prevalent in videogames set within actual historical contexts. In these games, the dead feature as in-game characters that are modeled on the records of notable real-world figures. As salient examples, one can think of ludic interactions like chatting with the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates as an NPC in the action-adventure videogame Assassin’s Creed Odyssey (Ubisoft Quebec, 2018), or opting to play Scipio Africanus as one of the Roman Generals available in the card game Hannibal: Rome vs. Carthage (Simonitch, 1996), or meeting Adolf Hitler as the main antagonist in the point-and-click classic Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (LucasArts, 1989; see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Indiana Jones meets the Führer in a memorable scene in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (Lucasfilm Games, 1989). Should the player decide to punch Hitler, Jones will be killed by the Nazi soldier standing behind him with a gun. Click image to enlarge.

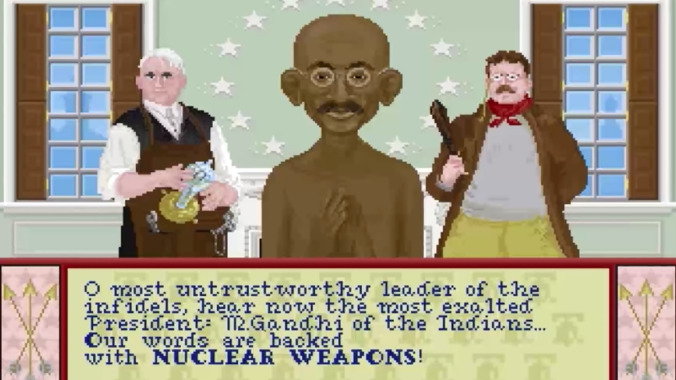

In these games, the actions of the dead -- whether they come from NPCs or player-controlled avatars -- can either take a historically accurate trajectory or give rise to counterfactual scenarios (e.g., there are no historical records of Adolf Hitler actually meeting Indiana Jones). The latter often arise due to narrative necessities or from NPCs responding dynamically to evolving in-game situations. For instance, although Mohandas K. Gandhi supported peaceful conflict resolution and never used nuclear weapons in his role as leader of the Indian National Congress (1921-1948), his counterpart in Civilization (Meier, 1991) can become aggressive and resort to atomic warfare (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: In the turn-based strategy game Civilization (Meier, 1991), each and every leader has the capability to escalate a conflict and trigger a war scenario. In the words of the designer of the game, “Gandhi firing nukes is, and always has been, inherently funny, no matter how rarely it occurs” (Meier, 2020, p. 265). Click image to enlarge.

The discrepancies between the actual lives of historical figures and their (pseudo-historical) in-game representations have already been discussed as opportunities for in-game humor by Jayemanne and Kunzelman (2022). The irony inherent in these untruthful portrayals, exhilarating as it might be, threatens to trivialize the struggles of the real people behind the characters and the historical meaning of their actions. Game scholar Gonzalo Frasca was particularly vocal about the questionable morality of such games. In his essay “Videogames of the Oppressed: critical thinking, education, tolerance and other trivial issues,” he invites his readers to imagine a hypothetical game where players control Anne Frank, the diarist and Holocaust victim. Frasca argues that if players were allowed to help Frank escape the Nazis and survive, the ensuing playful, historical scenario would undermine the significance of Anne Frank’s actual life and tragedy (Frasca in Wardrip-Fruin & Harrigan, 2004, p. 86). Reasoning on a less hypothetical scenario, one could argue the same point in relation to a chatbot of Anne Frank that was recently created by a Utah-based tech startup called SchoolAI. This conversational AI was allegedly trained on Anne’s famous diary, though it appears to be programmed to avoid pinning blame for Frank’s death on the actual Nazis responsible for her death, and instead attempts to redirect the conversation in a “more positive light” (Wilkins, 2025).

To summarize this point, games with historical settings often depict the dead in ways that are neither accurate nor commemorative of their actions and suffering. Accordingly, these kinds of playful activities could be accused of irreverence towards the significance of historical events and of the actual lives and struggles of our ancestors. Games and videogames that represent actual events and have verisimilar settings are, however, not the sole opportunities where one can establish interactive and potentially irreverent relationships with people who are actually dead.

Another example worthy of scholarly attention is the game genre of dead pools (also known as “deadpools” or “death lists”). In these kinds of games, players compete in predicting when a certain public figure will die. Unlike historical games, where players interact with fictionalized representations of dead people, dead pool games feature the deaths of actual people as elements of gameplay. Dead pool games are better understood as a loose family of folk games, rather than a specific codified set of rules and scoring criteria. In other words, multiple variations of dead pool games exist across socio-historical contexts without an original version, a formalized and documented ludic structure or a single author onto which their creation can be ascribed.

The origin of dead pool games is unknown, but their history can be traced back at least to 1591, when Pope Gregory XIV issued the papal bull Cogit nos depravata. In it, the Pope explicitly prohibited Catholics from placing bets concerning the creation of cardinals and the canonization of saints, games that -- as stated in the bull itself -- were common at the time. This ban extends a previous one that was limited to papal elections (Manzi, 2018, p. 115) [5]. Historical records also testify that wagers on the deaths of public figures and nobles were popular in British gentlemen’s clubs in the eighteenth century (Bourke, 1892, pp. 101-103).

Present-day versions of dead pool games typically consist of players selecting a set number of notable living people that they predict will die within the year (usually submitting their picks on January 1st, as is the case with many of the kind of dead pool games hosted on https://deathlist.net). In this category of games, individual player performance depends on the number of demises that they manage to guess, where extra points might be awarded -- depending on the variant -- for suicides and murders (and not due to, say, sickness or accidents). As a testament to the contemporary popularity of this type of games, one of Marvel Comics’ characters owes his superhero name, Deadpool, to the billboard stuck on the wall of the fictional bar where -- in the narrative -- patrons placed bets on who would die first among the mercenaries visiting the establishment. Even before Marvel Comics, the fifth (and last) Dirty Harry movie titled The Dead Pool (1988) centers upon a dead pool game connected to a series of murders that Detective Inspector Harry Callaghan is investigating.

Dead pool games evidently commodify human death and suffering, reducing loss and violence to in-game scoring conditions as well as inviting dispassionate and often cynical attitudes towards the deceased. Unsurprisingly, the flippant approach to mortality and grief that characterizes this family of games has occasionally been the target of social criticism, with accusations ranging from poor taste and tactlessness to outright immorality (cf. Di Santo, 2021).

To better understand how dead pool games position themselves in relation to themes of death and human suffering, the section that follows concentrates on a single case study: a popular online version of a dead pool game that has attracted significant media attention because of its quirky design and the social controversy it sparked. The game is titled Fantamorto -- a portmanteau of fantasy (as in “fantasy football”) and “morto,” the Italian word for “dead person.”

3. Fantamorto

The distinctive and particularly successful design of Fantamorto emerged from the aspiration -- explicitly voiced by the designer presently in charge of the game -- to adapt a common variant of a locally played dead pool game into an online platform capable of reaching and engaging a larger player base. At the time of writing, the website of Fantamorto boasts over fifty thousand registered users (over ten thousand of which are active players; www.fantamorto.org [the website is in Italian]).

Given their behind-the-scenes administrative role in the way the game currently runs, the designer in charge of the game goes by il segretario -- the secretary. In my interview with them, the elusive segretario explained that the transition from a traditional dead pool game to an online game happened in 2009 [6]. As a key aspect of this transformation, they decided to restructure and extend the specific variant of dead pool game that they were playing locally, hybridizing the original game with rules and methods of engagement that are typical of online fantasy sports. In the resulting ludic crossbreed, players no longer simply bet on a list of public figures that they guess will soon die, but take the role of sport-managers overseeing a team of morituri (a term that -- in both Latin and Italian -- refers to “those about to die”).

Fantamorto’s borrows its ludic structures and parts of its specific lexicon from fantasy sports, a choice that constitutes one of the game’s most distinctive tonal elements. On the one hand, this design strategy is clearly meant to captivate players with a familiar and readily engaging format. On the other hand, framing the game as a fantasy sport can be perceived as comically incongruous. Fantamorto (like Fantapapa, cf. endnote 5) does in fact juxtapose themes that are serious -- and even sacred to some -- with the mundanity and playful competitiveness of sports and fantasy sports. This humorous clash of sacro e profano, I argue, has been instrumental in establishing the social resonance and popular appeal of these games.

In Fantamorto, players compose and financially manage their team (or teams) through a web interface. Each team has a chosen captain, a yearly budget and various avenues to score victory points and secure additional funds to spend on more morituri. The game’s currency is the lira, a playful nod to Italy’s former national currency (its “dead currency,” supplanted by the euro in 2002) which symbolically links the game to notions like death and obsolescence. The yearly season of Fantamorto begins on November 2nd, the Day of the Dead. By this date, players must assemble a roster of public figures that they predict will soon die and select a captain from among them. Like other fantasy-sport games, the same public figure (the same morituro) can “play” for multiple teams. The initial size of a team is set at thirteen members, with thirteen being a number traditionally associated with bad luck in Italy. In Fantamorto, unlike most dead pool games, team size and composition can change throughout the game season. Once members of one’s team die, the player is supposed to substitute them with fresh morituri. For each deceased team member, the player is allowed to use their outstanding budget to acquire two additional celebrities that they predict will soon pass away to further boost the team’s score. The cost of new additions to a team of morituri is influenced by various factors, such as their age, health conditions and their popularity within the community: public figures added to various teams become progressively more expensive on the global market. Additionally, in the current version of Fantamorto, two transfer windows are available in each season; that is, two periods in which players have the opportunity to refine their rosters by replacing a number of team members. A key restriction applies to all kinds of team modification: to maintain the game’s element of uncertainty, public figures who are already sentenced to death cannot be added to the roster of morituri.

Each member of a player’s team who kicks the bucket scores 10 points, and their monetary value is transferred back to the players (plus a fixed sum of 15 lire per dead, facilitating the acquisition of new team members). Bonus points are awarded for younger deaths: +7 points for a team member who dies before the age of 30, and +5 points for those who die before reaching 50. Additional scoring modifiers apply to this general rule, however: the death of the captain of a team, for example, is awarded 10 additional points; dying on live TV (or web streaming, radio shows, etc.) grants a player 5 additional points; passing away on a Sunday or during a national holiday rakes in 2 extra points. For a complete list of scoring modifiers for the death of a team member, check https://www.fantamorto.org/regolamento/bonus-mortem.

The design of Fantamorto further showcases its irreverent attitude toward human suffering by including scoring opportunities that do not necessarily require a death to occur. Some of the most salient and notable among these scoring rules are listed below (my translation):

Sentenced for murder: +9 pts if the morituro is sentenced for murder (including multiple homicides). This bonus covers voluntary murder as well as cases of manslaughter, even those due to negligence. This bonus is also awarded for voluntary and spontaneous abortions. Guilty of massacre: +4 pts if the morituro is found guilty of murder as described above, with the number of victims exceeding three. In a coma: +8 pts if the morituro falls into a coma, including a vegetative coma, but excluding alcoholic, glycemic, or medically induced comas. Attempted suicide: +6 pts if the morituro attempts to voluntarily end their life without succeeding (bonus points not awarded for merely threatening to commit suicide). Victim of rape: +6 pts if the morituro is a victim of rape, sexual assault, or similar acts, provided that the crime was reported to the authorities within the timeframe of the current Fantamorto season. Victim of kidnapping: +7 pts if the morituro is abducted or kidnapped. Death of close relatives: +5 pts for the death of a relative of the morituro, up to the second degree. Pandemic: +5 pts if the morituro contracts a virus recognized as a pandemic by the WHO.

The game’s distinctive anti-life and anti-natal ideology is further emphasized by a special set of additional rules that penalize players when their team members engage in life-affirming actions. I present four examples below here (a complete list of penalties can be found at https://www.fantamorto.org/regolamento/malus-vitae):

Pro-life: -5 pts for each life saved by the morituro either through active or passive involvement. In remission: -4 pts if the morituro recovers from a serious or debilitating illness. Offspring: -3 pts for each child born to the morituro or their partner during the current Fantamorto season. This penalty also applies in cases of adoption or surrogacy. Lineage: -2 pts for each child born to the descendants of the morituro.

These rules, modifiers, and design decisions are publicly accessible on the game’s website, and have occasionally been the target of social criticism on Italian mainstream media. In response, the disclaimer on the game’s website now specifies that “Fantamorto is a humorous game, and the A.I.F.M. [Italian Fantamorto Association] does not endorse violence […].” In addition, the eighth item of the game’s ruleset (Part I) prudently states that:

8. Participants in the game must not take an active role in earning points [i.e. harming or killing public figures or relatives thereof], either directly or through third parties.

The people running Fantamorto thus appear to consider the game and its humor as divorced from the social conventions that apply to everyday life. This attitude was apparent in the informal interviews I conducted with three leading figures of the game’s community. In my individual consultations with il segretario and with two current members of the game’s steering committee (Fantamorto users Etta and Aethelfirth), all of them considered the game to be impervious to serious moral considerations. Each interviewee emphasized, in their own terms, that Fantamorto is an unserious pursuit, something entertaining they do in their spare time that has nothing to do with how they actually feel about the death of other people -- famous as they might be. To them, in other words, the game is essentially an interactive form of dark humor. My interviewees also claimed that the vast majority of Fantamorto players feel the same way they do. Their conviction, my interviewees argue, emerges from their daily interactions with the game’s community on the Fantamorto website, its online forum, and its social media channels [7]. They explained that for a regular player, deaths and illnesses befalling notable people are mere facts, information that they receive impersonally and dispassionately. Playing Fantamorto, they argue, is not an immoral activity, but one which is amoral (in the sense that it is obviously lighthearted, and that its paradoxically anti-life stance falls beyond serious ethical concerns).

One could argue that the way the Fantamorto community engages with the theme of death is neither an expression of rampant neo-Epicureanism nor an indication of their interest in Sartre’s existentialism. Instead, their cavalier attitude toward human mortality and suffering could be understood as a reflection of the broader spectacle surrounding celebrities’ lives and deaths in contemporary culture (cf. Jacobsen, 2016; Teodorescu, 2019, p. 90). Through media, social media and games like Fantamorto, the personal tragedies of public figures are mediated as spectacles. This process removes death from the players’ immediate lifeworld and reframes it as a set of “sanitized” cultural facts. Consistent with the tradition of dead pool games, the present discussion centers on notable figures (famous or infamous), a choice that is itself analytically significant. Public figures occupy a distinctive moral position in contemporary culture, one in which -- even while alive -- they are rendered legitimate objects of gossip and ridicule (cf. Schauer, 2009; Williamson, 2013). Their deaths, accordingly, are readily assimilated into entertainment and transformed into material for play. In that sense, Fantamorto could be understood less as a provocation about death than as a commentary on the cultural commodification of celebrity.

To be sure, I believe that adopting an indifferent or even irreverent attitude toward dying and the dead (like the one proposed by Sartre) is not in itself immoral or ethically problematic. I am also convinced, however, that there is an important distinction to be made between making light of death as an abstract concept and commodifying the passing of specific individuals [8]. Within the porous boundaries of its (so-called) “magic circle,” Fantamorto frames death as a resource within a playful economy -- one in which ethical implications would become painfully evident if players could earn points or in-game currency from the deaths of people within their own families.

Unlike a detached stance on death in general, Fantamorto -- like other dead pool games -- objectifies concrete, personal losses, likely causing unnecessary distress to those who are personally and emotionally affected by those deaths. Unlike common, traditional variants of dead pool games, however, Fantamorto takes an additional risky step, in terms of ethics. The game’s ludic range includes misfortunes experienced by still-living people. For example, Fantamorto awards points for celebrities who survive a suicide attempt or become victims of sexual assault. These scoring rules arguably carry a more direct risk of emotional harm than those found in classical dead pool games and might therefore be even less ethically justifiable. It is not a far cry to speculate that one of the reasons for the reticence of il segretario to use their real name is fear of being accused of unethical game design or that they are running a depraved website, and that those accusations might affect their life outside of the game (both personally and professionally).

In what could be deemed as yet another example of morally questionable game design (and an extreme one at that), Fantamorto’s current ruleset allows players to include minors in their teams. This means that players could not only earn points for the actual death of a child, but also score points when minors become victims of physical or sexual violence. My interviewees for this article did acknowledge that these are valid ethical concerns and explained that the possibility of modifying the rules to prohibit listing minors in one’s teams (or to prohibit minors from scoring any points in the game) are ongoing topics of discussion among the game’s steering committee members.

One final -- and particularly interesting -- aspect concerning the game’s problematic ethical orientation is the fact that Fantamorto does not currently reward violent or murderous acts against animals. Although this probably sounds like good news to the readers, I believe that this design choice requires further elaboration. The omission of non-human animals in the rules of Fantamorto can also be taken as an indication that the game designers did not consider the lives of non-human animals to be ethically relevant. To be sure, two of my interviewees rectified this objection of mine, and clarified that cases of animal abuse are still eligible for points under the following bonus category:

Honoris causa: +1 to 10 pts for objective merits earned in the field by the morituro, and in general for all relevant cases not covered by the game’s ruleset, but for which participants believe they should be awarded Fantamorto points. The final decision to grant this bonus is taken by il segretario, who will evaluate each case individually.

4. Conclusions

Reflections on how mortality and death are represented and experienced within interactive, digital worlds are relatively common in game studies. Such reflections typically address the consequences of the player-character’s death and emphasize how rarely that event carries any sense of finality or serious, lasting consequence for players (Mukherjee, 2009; Kirkpatrick, 2011, pp. 179-186; Gualeni & Vella, 2020, pp. 51-52).

A more ethically oriented interest in in-game death has recently begun to emerge within this disciplinary field, particularly in relation to the phenomenon of permadeath. The 2017 special issue of the Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds (Vol. 9, No. 2) was specifically dedicated to examining the emotional impact of permanently losing one’s character and progress in games, as well as to ethical reflections on the irreversibility of certain in-game events and their relation to actual experiences of death and loss. A noteworthy and more recent contribution to this discussion is West et al.’s (2021) article, “It’s All Fun and Games Until Somebody Dies: Permadeath Appreciation as a Function of Grief and Mortality Salience.”

Moral concerns and philosophical perspectives on establishing ludic relationships with the dead have arguably not been at the forefront of attention within game studies. Aside from Frasca’s pioneering insights (2000; 2004) as well as ongoing debates about historical fidelity in historical and pseudo-historical games (see Caselli et al. [2023] for an overview), reflections on the playful objectification of real deaths and the trivialization of actual people’s memory through gameplay remain rare in our scholarly community. Drawing from existential philosophy, anthropology and death studies, this article has sought to foreground these themes and concerns. In pursuing this objective, this article highlights how cultural trends and philosophical perspectives on mortality are mirrored in playful engagements with the deceased. From forms of interaction that are meant to sustain a sense of continuity and familiarity with the dead, to those that trivialize or commodify the lives and historical significance of the dead, how we play with the departed reflects broad cultural attitudes towards death, grief and memory.

The ethical implications of all of these practices clearly remain open questions, particularly in light of the progressively more technologically enmeshed lives we live in the Western world. As I hope I have shown in this article, media technologies -- including games -- can invite us to distance ourselves from mortality (objectifying and spectacularizing other people’s deaths). At the same time, they can be used to maintain some sort of relationship with the dead or, rather, with their “digital ghosts.”

If moral reflections on representing or playing with the dead are not entirely new within the field, the focus on dead pool games certainly is. As argued throughout, this category of folk games has not yet been examined within game studies -- neither in terms of their historical trajectory nor with regard to potential moral issues with their design. By examining Fantamorto, an Italian variant of the dead pool genre, I have aimed to illustrate how even the most seemingly flippant forms of play can disclose complex cultural negotiations with mortality, raising questions about the ethics of play, human suffering and the boundaries of the ludic.

Endnotes

[1] In a way that resonates with the philosophical perspectives outlined in this section, sociologist Zygmunt Bauman argued that “[…] the necessity to live with the constant awareness of [human mortality] go a long way towards accounting for many a crucial aspect of social and cultural organization of all known societies; and that most, perhaps all, known cultures can be better understood […] as alternative ways in which that primary trait of human existence -- the fact of mortality and the knowledge of it -- is dealt with and processed” (Bauman, 1992, p. 9).

[2] The notion that videogame worlds can serve as technologies for preserving and actively accessing the actions of past players -- allowing us to read notes about their thoughts and progress or witness re-enactments of their in-game deaths -- is also central to the emerging field of in-game archaeology (cf. Dodd, 2021; Smith-Nicolls & Cook, 2022).

[3] McIlroy-Young et al. (2022) define mimetic models as algorithms trained on data from a specific individual within a given domain that are designed to accurately predict and simulate that individual's behavior in novel situations within the same domain (p. 479). These mimetic models are developed, therefore, to have the potential to act as substitutes for the person they represent. As such, they can be employed in two types of scenarios: (i) situations where an event that could have involved the actual person instead occurs with the mimetic model as a stand-in, and (ii) counterfactual scenarios that could not be tested without the existence of a “digital substitute.”

[4] The awareness of this possibility and its associated ethical challenges were, however, clearly demonstrated by Dr. Siddhartha Sen, one of the authors of the cited papers on the mimetic modelling of chess players. In a personal exchange that followed his keynote presentation at the 2022 Foundations of Digital Games international conference in Athens, Greece, Sen expressed a clear awareness of these issues and underscored the pressing need for regulatory measures. Our discussion eventually led to a broader speculation about whether chess games -- akin to recordings of artistic performances -- might one day enter the public domain and, as such, be possible to be used as training data for artificial agents without requiring the explicit consent of the players in question.

[5] Contravening Pope Gregory XIV’s historical interdiction, Mauro Vanetti and Pietro Pace adapted the format of online fantasy football to a satirical prediction game about the papal election (https://fantapapa.org/ [website in Italian]). Fantapapa was designed and developed in February 2025, during Pope Francis’ hospitalization, and officially launched on the 22nd of April of the same year. Combining elements from both fantasy football and Catholic rituals, Fantapapa requires players to draft a team of eleven cardinals, including a captain (considered most likely to become pope) and a goalkeeper (deemed least likely). The game concluded with the appointment of Pope Leo XIV in May 2025. Due to its flippant game design, and with over 60,000 active players, Fantapapa gained international media attention.

[6] I contacted il segretario through personal connections and conducted an informal interview with them online in December 2024. They requested to remain anonymous. During the same period, I also individually interviewed two prominent members of the online community of Fantamorto. Although they did not explicitly ask for anonymity, I choose to refer to them by their in-game handles to respect their privacy and for consistency with how I addressed il segretario -- a choice they both approved.

[7] It is worth nothing that, according to my interviewees, cases of public display of joy for the death of a public figure have been reported in the past (say that of a convicted child murderer or a politician of the party on the opposite end of the ideological spectrum of a particular player). Those cases were, however, presented as rare occurrences and not indicative of typical Fantamorto player behavior.

[8] A further distinction could (and probably should) be drawn between the long deceased -- like historical figures -- and individuals who have either recently died or are approaching death. Making light of the former is arguably less problematic from a moral standpoint, as temporal distance reduces the likelihood of causing living people emotional harm. In such cases, death is typically integrated into cultural memory rather than experienced as a personal loss. By contrast, when the objects of play remain embedded in contemporary networks of care and mourning, the claim that playing Fantamorto is effectively amoral becomes difficult to sustain.

References

Ariès, P. (1975). Western attitudes toward death: from the Middle Ages to the present. John Hopkins University Press.

Bauman, Z. (1992). Mortality, Immortality, and Other Life Strategies. Polity Press.

Bourke A. H. (1892). The history of White's [with the Betting Book from 1743 to 1878 and a list of members from 1736 to 1892]. Waterlow and Sons. Available online at https://archive.org/details/historyofwhits01bouruoft/page/159/mode/2up (accessed on January the 10th)

Brin, D. (2002). Kiln People. Tor Science Fiction.

Caselli, S., Bonello Rutter Giappone, K., & Majkowski, T. Z. (2023). Ten years of historical game studies: towards the intersection with memory studies. GAME, The Italian Journal of Game Studies, 10(1).

Dodd, K. (2021). Narrative archaeology: Excavating object encounter in Lovecraftian video games. Studies in Gothic Fiction, 7, pp. 9-19.

Di Santo, C. (2021). ‘Fantamorto’ spopola online: vince anche chi indovina vip che prenderà il Covid. Available online at https://www.dire.it/25-01-2021/597265-fantamorto-spopola-online-vince-chi-indovina-il-vip-che-prendera-il-covid/ (accessed on January 21st, 2025)

Egan, G. (2010). Zendegi. Gollancz.

Floridi, L. (2015). “The right to be forgotten”: a philosophical view. Annual Review of Law and Ethics, 23, pp. 163-179.

Frasca, G. (2000). Ephemeral games: Is it barbaric to design videogames after Auschwitz. Cybertext Yearbook, 2, pp. 172-180.

Frasca, G. (2004). Videogames of the Oppressed: critical thinking, education, tolerance and other trivial issues. In Noah Wardrip-Fruin & Pat Harrigan (eds.), First Person -- New Media as Story, Performance and Game. The MIT Press, pp. 85-94.

Gualeni, S. & Vella, D. (2020). Virtual Existentialism: Meaning and Subjectivity in Virtual Worlds. Palgrave.

Gualeni, S. (2025). What We Owe the Dead. Set Margins’.

Heidegger, M. (1962) [1927]. Being and Time (trans. John Macquarrie & Edward Robinson). Blackwell Publishing.

Jacobsen, M. H. (2016). ‘Spectacular Death’ -- Proposing a New Fifth Phase to Philippe Ariès's Admirable History of Death. Humanities, 5(2), p. 19.

Jayemanne, D., & Kunzelman, C. (2022). Cybernetic irony: racial humour from mecha-Hitler to nuclear Gandhi. Video Games and Comedy. Springer International Publishing, pp. 253-270.

Kirkpatrick, G. (2011). Aesthetic Theory and the Video Game. Manchester University Press.

Krueger, J. & Osler, L. (2022). Communing with the Dead Online: Chatbots, Grief, and Continuing Bonds. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 29(9-10), pp. 222-252.

Levinas, E. (1992). La mort et le Temps. Le Livre de Poche.

Lucasfilm Games. (1989). Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Ron Gilbert, Noah Falstein and David Fox, published by Lucasfilm Games.

Manzi, S. (2018). Le lingue della Chiesa: latino e volgare nella normativa ecclesiastica in Italia tra Cinque e Seicento. Firenze University Press.

McIlroy-Young, R., Wang, Y., Sen, S., Kleinberg, J., & Anderson, A. (2021). Detecting individual decision-making style: Exploring behavioral stylometry in chess. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 34, pp. 24482-24497.

McIlroy-Young, R., Kleinberg, J., Sen, S., Barocas, S., & Anderson, A. (2022a). Mimetic models: Ethical implications of ai that acts like you. In Proceedings of the 2022 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, July 2022, pp. 479-490.

McIlroy-Young, R., Wang, R., Sen, S., Kleinberg, J., & Anderson, A. (2022b). Learning models of individual behavior in chess. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, August 2022, pp. 1253-1263.

Meier, S. (1991). Civilization [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game developed by Microprose and published by Microprose.

Meier, S. (2020). Sid Meier's Memoir!: A Life in Computer Games. WW Norton & Company.

Milton Bradley (1972). Séance. Board game with an uncredited designer published by Milton Bradley.

Mellor, P. A. & Shilling, C. (1993). Modernity, self-identity and the sequestration of death. Sociology, 27(3), pp. 411-431.

Mukherjee, S. (2009). ‘Remembering How You Died’: Memory, Death and Temporality in Videogames. Proceedings of the DiGRA 2009 International Conference in London (UK).

Nguyen, T. T., Huynh, T. T., Ren, Z., Nguyen, P. L., Liew, A. W. C., Yin, H., & Nguyen, Q. V. H. (2022). A survey of machine unlearning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.02299.

PBS Game/Show (2015). Can Video Games Be a Spiritual Experience? Online video essay available online at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vK91LAiMOio (accessed on January 1st, 2025).

Plessner, H. (2006) [1928]. I gradi dell’organico e l'uomo: Introduzione all’antropologia filosofica (trans. Ugo Fadini). Bollati Boringhieri.

Sartre, J.-P. (1957) [1943]. Being and Nothingness (trans. Hazel E. Barnes). Methuen & Co Ltd.

Schauer, F. (2000). Can public figures have private lives?. Social Philosophy and Policy, 17(2), pp. 293-309.

Simonitch, M. (1996). Hannibal: Rome vs. Carthage. Card game published by The Avalon Hill Game Co.

Sisto, D. (2020). Online Afterlives: Immortality, Memory, and Grief in Digital Culture. MIT Press.

Smith Nicholls, F., & Cook, M. (2022). The Dark Souls of Archaeology: Recording Elden Ring. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games in Athens, Greece, pp. 1-10.

Stokes, P. (2021). Digital Souls: A Philosophy of Online Death. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Teodorescu, A. (2019). Facing Death: A Sartrean Perspective on the Contemporary Tendency to Over-Humanize Death. In A. Teodorescu (Ed.) Death within the Text: Social, Philosophical and Aesthetic Approaches to Literature, Cambridge Scholar Publishing, pp. 84-108.

Ubisoft Quebec. (2018). Assassin’s Creed Odyssey [Sony PlayStation 4]. Digital Game directed by Jonathan Dumont and Scott Phillips, and published by Ubisoft.

Vinge, V. (2003). The Cookie Monster. In Analog Science Fiction and Fact, October 2003.

West, M. S., Cohen, E. L., Banks, J., & Goodboy, A. K. (2022). It’s all fun and games until somebody dies: Permadeath appreciation as a function of grief and mortality salience. Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds, 14(2), pp. 181-206.

Wilkins, J. (2025). Schools Using AI Emulation of Anne Frank That Urges Kids Not to Blame Anyone for Holocaust. Available online at https://futurism.com/the-byte/ai-anne-frank-blame-holocaust (accessed on January 20th, 2025).

Williamson, M. (2013). Celebrity, gossip, privacy, and scandal. The Routledge Companion to Media & Gender, Routledge, pp. 311-320.