What is the Form of Play? Ludic Form and the Development of Movement in Virtual Space

by Christopher LukmanAbstract

In this essay, I explore the form of play through a comparison with the form of music. Drawing on Eduard Hanslick’s concept of “sonically moved form,” I argue that the structure of action games functions similarly to musical form, in that it requires performance to come to life and that it involves the unfolding of affective ideas. More specifically, I define the form of action gameplay as the development of movement within virtual space. Through a case study of the platformer OlliOlli World, I demonstrate how insights from musical form analysis can enrich our understanding of ludic form. This study aims to present an alternative approach to game analysis, one that challenges the hermeneutic mode known from literary studies, which often focuses on semantic meanings, narrative interpretation and cultural analysis.

Keywords: form, aesthetics, music, rhythm, affect

Introduction

Every humanist discipline has more or less stable notions of form and standardized approaches for its analysis. Even if the term “form” remains usefully ambiguous, a literary scholar, a film scholar and a musicologist will have an idea of what “form” designates in their discipline and approach it analytically. Among these disciplines, musicology serves as a fruitful case for comparison in the endeavor to derive a notion and analysis of ludic form. Music is the chief representative of what art philosopher Susanne K. Langer (1953, p. 121) calls “temporal” or “occurrent arts” insofar as its works are instantiated in every performance, its forms are immaterial, and its representations are manifold. In this essay, I want to argue that it makes sense to think the ludic form analogous to the form of music. In doing so, I want to establish an alternative to existing approaches of ludic form, which were usually inspired by critical theory (Kirkpatrick 2011, 2018) or the literary tradition of Russian formalism (Pötzsch (2017), Mitchell and van Vught (2024), Myers (2010)). My central argument is that musical and ludic form both hinge on the performance of movement -- sonic in the case of music, and virtual in the case of the videogame.

A short explanation may clarify the analogy. Western classical music’s most studied form is the sonata form, which consists of exposition, development, and recapitulation. A quick look into the score of the first movement of Beethoven’s piano sonata in F-minor, op. 2/1, suffices for a musicologist to know the beginning and end of these structural parts. Musical scores are also called sheet music -- a paradoxical designation as music lives in sound, not in haptic sheets of paper nor the visual representations printed on them. As music aesthete Eduard Hanslick (2018 [1854]) famously claimed, music is “sonically moved form,” and sheet music, while a useful tool for performance and analysis, is only a means to a sonic realization, and the aesthetic appreciation through a listener’s ear.

Musical form analysis lends itself to the Greek origin of form as morphē -- it traces the morphology, that is, the development of motivic-thematic units within a piece. This morphology marks the hallmark of the classical-romantic repertoire, though it can illuminate other musical styles as well. Music, being ephemeral, unfolds as duration and must be rendered visible to be studied synchronically. The sheet music provides the instructions for producing a sequence of rhythmical tones, but it is due to the performer to bring musical form into audible presence. Musicologists, in turn, usually study the same or similar notation that guide the performer, grounding their analyses in a shared object of reference.

For composers and performers, principles of form are ways of expressing and thinking within the musical medium and its inherent laws. Likewise, I want to suggest that game designers and players inhabit formal principles within certain genre traditions, which we have only begun to uncover. After visiting some concepts of musical form analysis, I will argue that the form of action-based videogames is the development of movement in virtual space -- a development that an analysis can trace in its motivic-thematic material. Furthermore, I will argue that describing this development necessitates an affective sensibility attuned to the level design of a game sequence. I will make my ideas concrete by analyzing a level in the 2D platformer OlliOlli World (Roll7, 2022) and conclude by suggesting how this approach may be expanded to other genres and forms of play.

Musical Form, Central Concepts

The analysis of musical form presupposes certain premises in music philosophy, which were most clearly articulated by Eduard Hanslick (2018 [1854]). Laying the philosophical foundation of the so-called idea of “absolute music,” [1] Hanslick insisted that music could not function akin to language by signifying extra-musical contents. The point was heavily contested in his time, which was also the time of Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner, composers who firmly believed that music should convey literary subject matters like Goethe’s Faust of the myth of Tristan and Isolde. Hanslick, however, formulated the opposing view by positing that the musical medium exists solely in the immanence of “sonically moved form.” Although the poetic word could be added to a musical form, the verbal and the musical would then supplement each other rather than being autonomous modes of expression. Following Saussurian semiotics, linguistic signs exist in a dyad of signifier (the word “tree”) and signified (the mental idea of a tree), but what could be the musical expression? Hanslick argues that musical forms are inextricably tied to what we call affect:

By contrast, with its distinctive means, music can most richly represent a certain circle of ideas. According to the organ that receives them, these are, to begin with, all those ideas that relate to audible changes in force, motion, and proportion, that is, the idea of intensification, attenuation, of hastening, hesitation, of contrived complexities, of straightforward progressions, and the like. (Hanslick 2018 [1854], p. 17)

In the most general sense, affects of tension and release figure as the immanent ideas of music. Words that capture these figurations are abstract by necessity, referring to experiential categories with a temporal index like intensification, attenuation, or hastening. Because music consists of vibrations in the air, produced by an instrument, and traveling to the ear of a perceiver, its foundations are to be found in acoustics. For the classic-romantic epoch, musical sounds are normalized and conventionalized frequencies making up a whole tonal system in which musical elements like scales, dissonance, consonance, major and minor chords are rationally defined by a mathematical measurement of intervals. Writers of the nineteenth century are no different from writers from earlier epochs, who found in their tonal system an inner truth. For Hanslick, each musical sound possesses inner tendencies (“elective affinities”), due to its embeddedness in the tonal system:

All musical elements have among themselves secret alliances and elective affinities grounded in natural laws. Those elective affinities invisibly governing rhythm, melody, and harmony, demand compliance in human music, and they stamp every contradictory connection as arbitrary and unattractive. (Hanslick 2018 [1854], p. 45)

It would become the task for modernist composers to liberate themselves from the system of majors and minors and explore the tendencies of new musical material in things like atonality, microtonality, sounds from everyday life, sounds created in electronic synthesis, and so on. While contemporary Western music distanced itself from the classic-romantic style to yield numerous experimental practices, I would argue that musical composition remains the act of arranging musical material by virtue of their affinities and tendencies. For Hanslick and his contemporaries, the tendencies of the tonal system implied how tones could be played together (harmony) or following one another (melody) in temporal measures (rhythm). As harmony, melody and rhythm form tight interrelations, composers need to become as natural within the tonal system as in the syntax of their mother tongue. The goal is to compose freely and intuitively instead of feeling constrained within these musical laws.

Until today, the study of musical form revolves around the compositional techniques of the three Viennese classics Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. In the classical style, motives are subject to manifold developments, and musical form seems to grow organically out of a thematic germ. The challenge to compose within such a style is immense, just like the challenge that the composed piece poses to a listener’s ear. In direct continuation of the quote given above, Hanslick writes:

Although not in the form of scientific awareness, they [the elective affinities between the musical elements; CL] reside instinctively in every cultivated ear, which by pure contemplation perceives, accordingly, the organic quality, the rationality, or the nonsensical, unnatural quality of a tone group, without a logical concept providing the criterion or tertium comparationis. (Hanslick 2018 [1854], p. 45; emphasis in original)

A musically educated ear perceives a tone sequence intuitively without engaging a rational faculty of mind. This is to say that the judgment of a good or bad-sounding musical sequence does not have to pass through a logical concept. A musician apprehends the beauty of a musical sequence without an act of analysis -- though analysis can help make explicit what we have encountered in the musical experience. Hanslick’s notion of musical beauty as formal organization implies that such organization cannot be seen in the score alone. Musical beauty exists only in the temporal flow of sound.

As musicology developed into an academic discipline, the study of musical form became a training ground for the musical ear. Form was no longer merely an object of study for composers seeking to learn from the classical canon. Connecting theoretical and historical study, musicology started to engage in formal analysis to study composers, styles and historical periods. Austrian music theorist Erwin Ratz (1951a) helped establish “Formenlehre” through the publication of Einführung in die musikalische Formenlehre (Engl. Introduction to the Study of Musical Form). As the title suggests, one of Ratz’s many endeavors in this book was pedagogical. The detailed study of musical form fulfilled the purpose of “activating the musician’s capacity for experience and thereby deepening it” (Ratz 1951b, p. 8; translation added) and so he regarded every act of listening as a learning process. While a first listener might already be taken by Beethoven Sonata's formal development, formal analysis should help the student become sensible of every nuance of a piece. Only then can musical form unfold the full scope of its aesthetic potential in the perception of an ideal listener (Ratz 1951b, p. 3).

It was not until around the turn of the millennium that Ratz’s analytical ideas found further systematization in William E. Caplin’s Classical Form (1998), today a widely read textbook in many musicologist curricula. Caplin built a coherent terminology of formal concepts to fully analyze the large, but still limited corpus of the classical style. In doing so, Caplin carried over many of the philosophical points made by Hanslick into a stable framework for formal analysis, one that we still lack in game studies. Fruitful for our later attempt to describe ludic form is his distinction between formal processes and formal functions.

A formal process speaks of how a certain structure adopts a preceding structure. A formal function speaks of how a structure relates to the entire organization of the piece.

As we will see, formal processes (e.g., repetition, fragmentation, extension, expansion) are the compounds that make up formal functions (e.g., presentation, continuation, cadential function, closing function, etc.). Caplin lists them numerously in a glossary, defining them in abstract terms useful for further adaptations (1998, pp. 254-258). To give an example of a formal description, let me paraphrase part of his discussion of the first eight bars of the following Beethoven Sonata, hopefully keeping things understandable for non-musically trained readers.

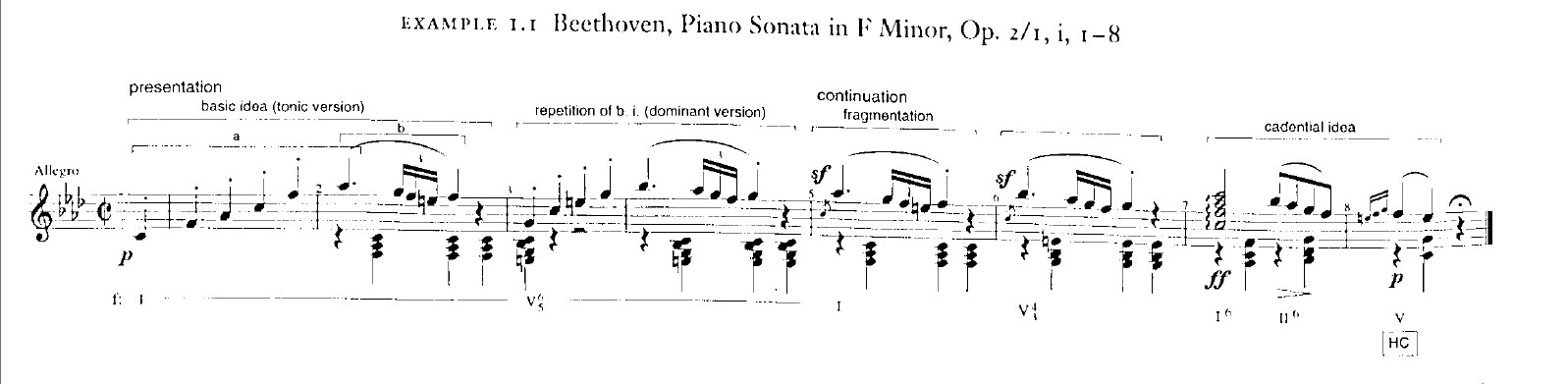

Figure 1: Excerpt taken from Caplin (1998, p. 9). Click image to enlarge.

The piece begins with a two-measure grouping, in which the basic idea is presented in a single gesture. Two melodic blocks constitute the basic idea, here labeled “a” and “b,” two motives, which will later in the piece play separate roles. Measures 3 and 4 repeat the basic idea, although now in the dominant harmony C major. A repetition is a formal process that makes the listener grow accustomed to the motivic material and confirms the unity of the basic idea. Caplin calls this a statement-response-repetition, as the basic idea is first presented in the F minor key -- the basic key of the entire composition -- and then repeated in the dominant key, which will resolve again in measure 5 into the F minor. Note how the pause in measure 2 marks the end of the basic idea, confirming its unity. Four measures suffice for the formal function of the “presentation” to conclude as the piece is now committed to a specific grouping of tones.

After this presentation, the piece proceeds with the formal function of continuation from measures 5 to 8, which starts with isolating the “b” block of the basic idea and repeating it in the same harmony. This fragmentation accelerates the piece considerably by shortening the “b” block from two measures to one. The fragmentation quickens the pace and intensifies the piece’s rhythmic flow. Measures 7 and 8 initiate the cadential idea, which brings the whole section to a close. In this cadential idea, Caplin constates the liquidation of the “b” block because it abandons a characteristic rhythmic element, signaling that the section is coming to a close.

This paraphrase makes it seem like the analysis could be done without an audio recording of the Beethoven sonata. But this is not the case: When things get tricky, Caplin chooses to stick to what he hears rather than what he reads from the score (e.g., “But this level of harmonic activity does not necessarily conform to our listening experience” (Caplin 1998, p. 12)). What might look like a harmonic acceleration might not sound like one at all, making formal analysis a school of musical listening even in the twenty-first century.

A complexity ignored by most musicologists is that no professional recording of a Beethoven sonata is the same. Finding a personal style is the strenuous effort of a professional pianist’s education. Consequently, in every new recording, a pianist will consciously or unconsciously mark differences from other existing recordings of the same piece. These will only occasionally influence analytical results -- the presentation of our Beethoven sonata will perhaps always be identified as a presentation. This allows us to understand, however, that the only way to experience and analyze musical form truthfully is by listening to its instantiations -- which are, in principle, all different.

Before connecting these findings to videogames, let me anticipate two possible objections, especially from trained musicologists. First: Why privilege Caplin’s framework over other theories of form? Is it not a problem that we import Western classical aesthetics to videogame analysis? The decisive criterion is that Caplin’s approach proceeds from the small to the large -- it builds form through motivic development -- whereas other models, such as those of James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy (2006) or Charles Rosen (1980), operate primarily on a large-scale, top-down level. Jazz, of course, offers an intricate example of a style that likewise constructs larger forms from small motivic cells. But as a classically trained musicologist, I know neither if a coherent morphological theory of jazz form exists, nor if I could deploy it with sufficient expertise. In any case, the Western classical lineage should not be seen as an obstacle. Caplin’s terminology is abstract enough to be detached from its historical context and adapted to other domains, such as the analysis of a 2D platformer.

A second objection is that I am relying on an overly conservative ontology of music, one that recent scholarship has called into question. Nina Sun Eidsheim (2015), for instance, argues that music lies in the bodily responsiveness of listeners to vibrations and voice, while Fred Moten (2003) roots the form of Black music in racialized collective experience. These approaches move beyond the classical hermeneutic tradition of musicology, which, as many would argue, has been exhausted. Game studies, however, finds itself in a different situation. As Marc Ouellette and Steve Conway (2020) put it, ours is still a pre-paradigmatic field: we lack an agreed-upon repertoire of concepts, and interdisciplinarity remains an unfulfilled promise. Musicology’s long history of formal analysis meant that students could quickly acquire a feel for discipline, and innovators like Eidsheim and Moten formulate their challenge to Hanslick’s model in ways that were immediately recognizable within the field.

So, while I offer the following thoughts with excitement to see how future researchers may adopt, refine, or contest them, I will continue to defend the position that musical and ludic form should essentially be recognized as distinct ways of thinking. Only then does it make sense to trace their connections to the social, the political, or the existential. Aesthetic media possess their own internal logic -- a logic that both constrains and enables lively experience. It is this affective, lively form that I seek to uncover in the videogame. In doing so, I hope to affirm that games, like music, do not merely reflect the world but articulate a mode of thought that is uniquely their own [2].

From Musical Form to Ludic Form

Having established how musical form depends on performance and motivic patterning, I now turn to the question of how these ideas might add something to the young, but existing discourse of form in game studies. My goal is not to impose a musical metaphor onto games, but to draw conceptual parallels between two occurrent art forms that depend on the performance of patterned movement. Comparing games to music helps to make clear that formal developments do not have to coincide with semantic content.

The non-semantic characteristic of the videogame form was also well argued by Veli-Matti Karhulahti (2013, n.p.). He writes that the form of play consists of challenges that posit “no claims, arguments, or extractable thematic meaning.” Responding to one of the most dominant theories of representation in games, Ian Bogost’s procedural rhetoric (2007), Karhulahti holds that if the form of videogames has a rhetoric, it is, in fact, empty of meaning. In his mind, videogames manifest either through kinesthetic or non-kinesthetic (cognitive) challenges, which can both be tied to time-critical input windows. While the cognitive challenge might be home in puzzle games, adventure games, the kinesthetic challenge finds its preferred genres in platformers, fighting games, and other action games [3].

The non-semantic notion of form goes against many approaches inspired by literary studies, like Russian formalism. While Russian formalism in game studies often goes beyond the analysis of narrative, the idea is usually that games estrange whatever they adopt from the real-life world in order to convey cognitive insights to the player. Formalists believe that a game’s poetic principles points toward the game’s cultural embeddings, like sociopolitical or economic realities (Pötzsch 2017; Mitchell and van Vught (2024)). While this notion of form skips the holistic appearance of play in favor of social commentary, perhaps the bigger problem with the formalist school is that it holds on to Viktor Shklovsky’s modernist bias, which usually looks for a game’s critical positioning. The modernist bias is problematic because it allows the critic to disregard games in which such critical positioning is absent, overlooking their proper aesthetic qualities.

Another modernist game aesthete, Graeme Kirkpatrick (2011; 2018) points toward a similar notion of form as the one I will unfold in this essay, revolving around movement patterns, their motivic development, and the player gesture on the controller: “The form […] is a pattern present in the relation between the kineme and the other elements of the game apparatus” (2011, p. 104). But like the literary formalists, his interest in social embeddings seems to overshadow a deeper investigation into the inner logics of form. I agree with him that “Videogames are not communications media in any standard sense” (2011, p. 1), but would argue that he fails to see the deeper sense in their non-representative nature: “Games often leave us with a feeling of guilt, of having wasted too much time on something meaningless and empty” (2011, p. 8). Elsewhere, on the topic of repetition in games, he fully embraces the Frankfurt school jargon and goes as far as to say that “In the seriousness of play we mourn our inability to advance from infantilized consumers to free citizens” (2011, p. 190).

I find more helpful points of connection in domains of game studies, independent from the discourse of ludic form. Peter McDonald (2024) has recently provided a helpful way to think about performative aspects of the platformer genre by emphasizing movement arcs, artificial gravity, hazards within the level design, and collectibles as attraction points of movement -- elements which I will base the following analysis on. McDonald’s interest in the pleasure and feeling of games can be meaningfully extended with Aubrey Anable’s (2018) perspective that feelings in games emerge from an interplay with the videogame screen, configuring a zone of contact, which puts the player’s body, interfaces, and visual arrangements into negotiation, allowing movement to flow across heterogenous materialities.

This points to my main ontological claim in this essay. Videogames and music resemble each other because they both rely on movement -- or better yet -- because they are movement. If music is sonically moved form, I argue that the form of bodily play in videogames is the development of movement in a virtual space. Following Lambert Wiesing (2005, pp. 107-124), I define the virtual as a spatial category of the videogame image where players get to explore artificial physics by controlling objects within the screen through their input devices. In this vein, the virtual is not something wholly disconnected from physical reality, rather, players explore the material characteristics of virtual image objects through their embodied gestures. OlliOlli World gathers its playthings in a skate setting, where they appear through the felt dynamics of weight, impact, force, speed and so on. The playable character is a moving entity exploring its movement potential in the virtual space of a two-dimensional platform level, represented as a skate challenge.

Ludic Form in OlliOlli World

So how does ludic form play out concretely? I now turn to a level of OlliOlli World, drawing on Caplin’s formal processes -- presentation, repetition, fragmentation and extension -- to show how a level’s design structure adapts them through gameplay challenges. Firmly situated within the 2D platformer genre, OlliOlli World features a playable character who moves from left to right, jumping across platforms. The game quickly frees itself from the expectation of simulating real skateboarding as it cares little for physical realism or the actual mechanics of skate motion. In what follows, I analyze “Epic Falls,” a level designed around the wallriding mechanic, which can only be executed when skating along billboards. While real-world skaters seek to master improbable feats, skating billboards like in OlliOlli World will remain an impossibility. In reality, a wallride lasts only a brief moment: the skater throws their board against the wall so that all four wheels make contact, then pushes off again almost immediately.

In OlliOlli World, the longest wallride in Epic Falls takes around six seconds. It is performed not against a wall of concrete but against objects within the image. In the fictional world of OlliOlli World, billboards are held up by “friendly billboard bees,” as we learn from an NPC. Other than billboards, there are two other terrains in this level. First, we have the normal ground terrain in which the playable character must push the skateboard with their feet to gain speed, and second, the rails marked in light beige for the playable character to slide on (“grinding”).

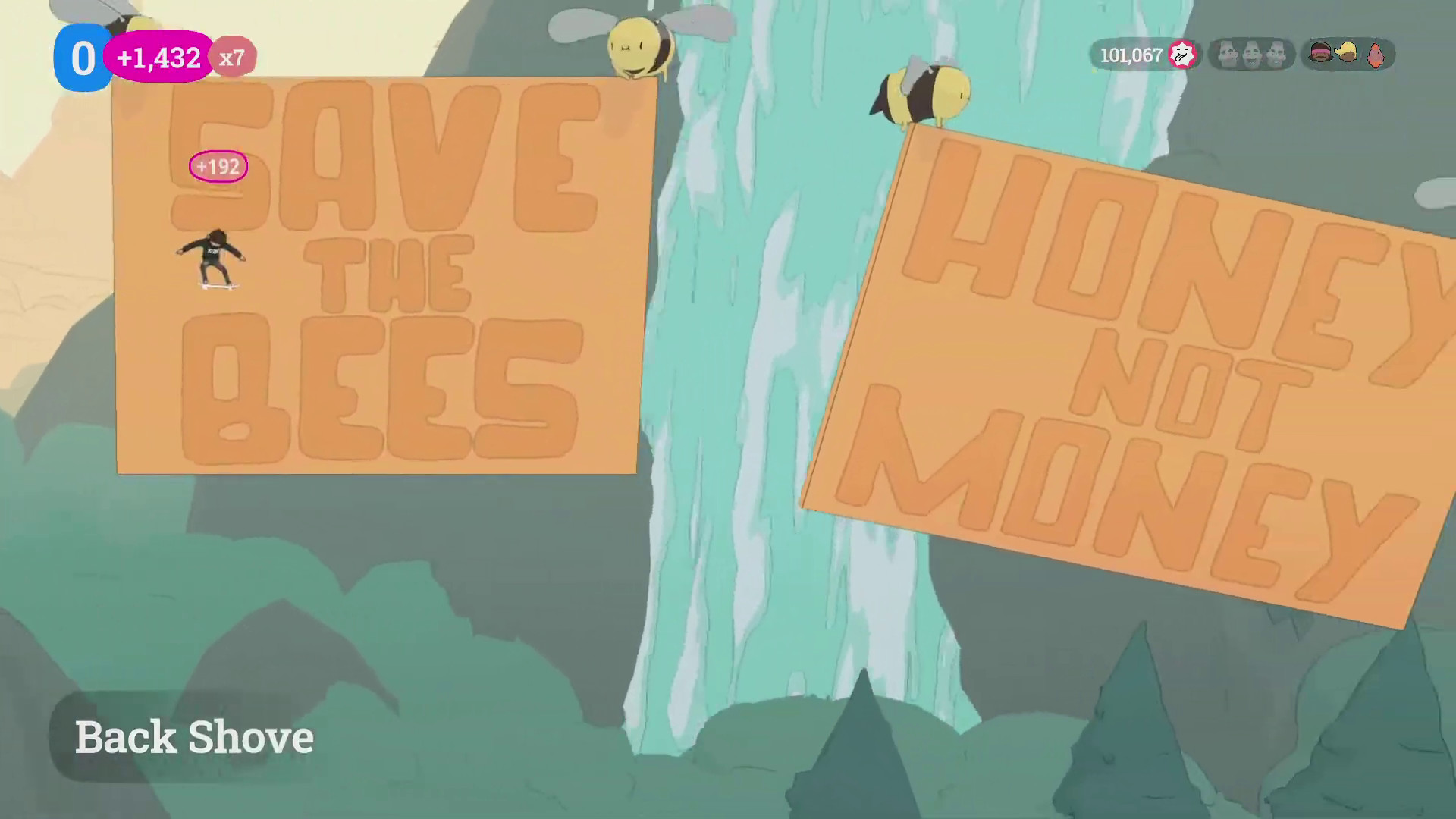

Figure 2: Jumping from a grind into a billboard for wallriding (0:15 in the video referred). Click image to enlarge.

In OlliOlli World, the change of terrains, like having to jump from a rail to a billboard, confronts the player with time-critical challenges, prompting the player ‘to make a move’ using a suitable input combination. As the smallest units of form, challenges hold special significance for game studies. Karhulahti (2013, n.p.) rightfully elevates the challenge to the form-generating aspect of the videogame, providing the term of “kinesthetic challenges with time pressure” to what we encounter here. All three terrains define a distinct way of movement: pushing (ground), grinding (rail), and wallriding (billboard), though tricks (like an ollie) are necessary to jump between the terrains. Failing to jump into or out of a wallride -- often due to insufficient speed, or a bad arc of motion -- is the only way to die in this level, offering the player an immediate chance to retry, true to classic arcade tradition. Distributed within the level, the four save points allow players to resume play without having to restart from the very beginning.

Although the player gains more points the more skillful tricks they incorporate into their run, a successful run does not require a high score, only a certain arc of movement. One could always graze death by wallriding the billboards as low as possible, or one could create particularly high arcs of movement, allowing the player succeed the side quest “Air over nine bees!” [4]. Since bees usually fly around the middle or lower ends of the billboards, jumping (“airing”) over them, provides style points for particularly nicely shaped arcs. A particularly skillful run of this side quest by YouTuber AlexWontCook (2022a) will serve here as a reference, demonstrating a remarkable fluidity of play.

A thankful case for formal analysis, OlliOlli World’s movement options exist only in strict relation to the terrain. In that way, OlliOlli World defines the form-generating notion of a challenge as the transition of one terrain to another, a time-critical jump. This means we can transcribe our model run simply by writing out the terrains in sequence.

|

Section |

Sequence of challenges |

|

1 |

ground + grind + wallride + grind + wallride + wallride + grind wallride + wallride + ground, checkpoint reached |

|

2 |

ground + grind + wallride + grind + wallride + wallride + grind + wallride + wallride + wallride + grind + ground, second checkpoint reached |

|

3 |

ground + grind into intersection If player grinds into intersection go to 3a, if they use the flat ground go to 3b |

|

3a (backside path) |

grind + wallride + grind + wallride + grind + wallride + ground + third checkpoint reached |

|

3b (frontside path) |

grind + wallride + wallride + ground + NPC reached + ground |

|

4 |

ground + wallride + ground + wall ride + grind + wallride + ground |

Table 1: Sequence of Challenges.

By turning the level into a list, we can immediately deduce certain patterns.

- A checkpoint NPC marks the end of every section.

- Every new section begins and ends with ground terrain.

- Sections one and two are almost identical. Section two simply adds one wallride and one grind to the first section’s string of movements.

More importantly, we discern a combinatory logic, the “elective affinities” Hanslick pointed out between formal elements. Wallriding can be combined up to three times (see section 2) but must be couched between two grinds -- or two ground terrains in the last section. We can suspect the level’s basic idea in the pattern “grind-wallrind-grind,” from which only the last section deviates.

A look into the play run and the shape of the terrain confirms this belief and surfaces the efficacy of this pattern. Rails are not only an elevated terrain (compared to the ground terrain that one rides when missing the rail) but provide a second opportunity to gain elevation and acceleration for the coming wallride. Grinds thus serve a preparatory or anticipatory function: grinds often follow wallrides, leaving the player guessing whether it leads into another wallride or a ground terrain, marking the end of a section.

Figure 3: 0:28 in referred video. Click images to enlarge.

All terrains before wallrides are usually wave-shaped, as shown in figure 3. They start with an even part where the player lands after exiting a wallride to then transition into a steep incline and end with a slight upward bend to shoot the player upwards. After landing on the even part, the incline accelerates the player, allowing them to anticipate the trick at the upward bend. This is how grinds fulfill two functions. They let us enter into a wallride and exit from one. Grinds are both initiation and ending to the basic pattern. This dual function lends this level its fast pace -- the end of one pattern transitions into the start of another. In music, something similar is called the “interlacement of phrases” [5] [Phrasenverschränkung], commonly employed to interlace subsections in order to retain a certain energy of movement. This new knowledge lets us further flesh out our table.

|

Section |

Sequence of challenges |

|

1 |

ground + [grind + wallride + grind] + [grind + short wallride + short wallride + grind] + [grind + short wallride + short wallride + ground] + ground, checkpoint reached |

|

2 |

ground + [grind + short wallride + grind] + [grind + short wallride + short wallride + grind] + [grind + short wallride + short wallride + short wallride + grind] + [grind + … + ground] + ground, second checkpoint reached |

|

3 |

ground + grind into intersection IF player grinds into intersection go to 3a, if they use the flat ground go to 3b |

|

3a (backside path) |

[grind + short wallride + grind] + [grind + short wallride + grind] + [grind + long wallride+ ground] + ground + third checkpoint reached |

|

3b (frontside path) |

[grind + wallride + wallride + ground] + NPC reached + ground |

|

4 |

[ground + wallride + ground] + [ground + wall ride + grind] + [grind + long wallride + ground] + ground + finish line |

Table 2: Sequence of Challenges with Pattern Indications.

In this second table, we could be even more precise and mark the anticipatory function as well as the landing function at the beginning and end of each pattern, but too many markings would destroy the clarity of the table. Every subsection works out the basic pattern three times with varying lengths of wallrides. An exception is the second section, in which the third occurrence of the basic pattern is followed by a somewhat humorous jump that I will detail later. As the basic version of this pattern morphs into different variations, the level realizes a specific rhythm embedding the player’s actions. To analyze these formal schemes, we can apply Caplin’s terminology of formal processes, although in free adaptation.

Figure 4: First wallride in first section (0:06 in video referred). Click image to enlarge.

The first presentation of the grind-wallride-grind pattern features a wallride (see figure 4), which will reappear in shorter versions. These shorter wallrides appear in the first section as chains of two (see figure 5). Resembling Caplin’s formal process fragmentation, the length of the first wallride is split into two, adding a challenge. The adaptation of Caplin’s term is not clean. For Caplin, a fragmentation means a “reduction in length of units in relation to the prevailing grouping structure” (1998, p. 255). Here, the duration of the wallrides may be reduced, but the entire grouping structure keeps its total length. Since the wallride poses the central challenge of this level, I choose to relate fragmentation only to the wallride rather than the entire grouping pattern. These fragmented wallrides become the model for the subsequent sequences, finding a repetition at the end of the first section.

Figure 5: first wallride-wallride sequence in the first section (0:10). Click image to enlarge.

The second section starts with a basic “grind-wallride-grind” pattern, echoing the first pattern of section one, this time adopting the fragmented wallride (see figure 6, top image). This modified presentation of the basic pattern turns the fragmented wallride into the new reference and lends the following sequences a predictable rhythm. The second and third sequences extend the pattern each by inserting one or two short wallrides into the pattern. If this happened in music, Caplin would call these “extensions” of the modified basic pattern through subsequent repetitions. The essential difference between the musical form and the ludic form transpires here: while an extension in the musical form is an increase in temporal duration, an extension in the ludic form means an increase in the virtual distance established by the pattern.

The extensions make the rhythm so predictable that the level designers decide to conclude the section with a humorous comment. Ready to extend the rhythm one more time, the player need not do anything to succeed in the jump. The pattern is broken by a liquidation (“systemic elimination of characteristic motives” (Caplin 1998, p. 255)) of the wallride (figure 6, bottom image).

Figure 6: first grind-wallride-grind sequence in second section (0:22) and last jump (grind-ground) of the second section. Click images to enlarge.

After the emergence of such a predictable pattern, the third section adds a novelty to the level through an intersection. After reaching the second checkpoint, the player either enters section 3a with a grind or into 3b when staying on ground terrain. In section 3b, an NPC greets us by unlocking a hidden level on the world map. But because our reference video takes the grind into section 3a, the more interesting formal section, we will discuss it here. 3a repeats the modified basic pattern of the second section twice to then present an expansion in the third pattern by stretching the wallride in length, amounting to almost five times the length of the fragmented one. The expanded wallride serves as a side quest as sudden sound effects signal a crowd demanding a special trick. “Ohhh!” eventually dissolves into a somewhat disappointed “Auh…” in our reference video (TC 0:50-0:53). To succeed in this sidequest, the player must land an advanced trick, as shown in a video by YouTuber Jud Cad (2022).

The expansion will return in the fourth and last section. The fourth section begins with the basic pattern, where the wallride is yet again fragmented, although this time it is longer than the modified version of section 2 and almost identical in length to the original in section 1. The fragmented patterns invoke a staccato rhythm of short inputs until an unusually steep wave-shaped rail prepares another expanded wallride. This expansion parallels the end of section three and brings the whole level to a conclusion in a relaxed way. Since expanded wallrides pose no challenge, the player can just enjoy the ride, exit the wallride whenever they please, and roll towards the finishing line. The following table accounts for all the challenges and formal processes at this level.

Figure 7: top: long wallride in section 3; bottom: long wallride in section 4. Click images to enlarge.

|

Section |

Sequence of challenges in first row, sequence of formal processes in second row |

|

1 |

ground + [grind + wallride + grind] + [grind + short wallride + short wallride + grind] + [grind + short wallride + short wallride + ground] + ground, checkpoint reached |

|

framing + presentation of basic pattern + fragmentation + fragmentation + framing |

|

|

2 |

ground + [grind + short wallride + grind] + [grind + short wallride + short wallride + grind] + [grind + short wallride + short wallride + short wallride + grind] + [grind + … + ground] + ground, second checkpoint reached |

|

framing + modified presentation with fragmentation + twofold extension of modified pattern + threefold extension of modified pattern + liquidation of pattern + framing |

|

|

3 |

ground + grind into intersection IF player grinds into intersection go to 3a, if they use the flat ground go to 3b |

|

framing |

|

|

3a (backside path) |

[grind + short wallride + grind] + [grind + short wallride + grind] + [grind + long wallride + ground] + ground + third checkpoint reached |

|

Modified presentation + repetition + expansion |

|

|

3b (frontside path) |

[grind + wallride + wallride + ground] + NPC reached + ground |

|

4 |

[ground + wallride + ground] + [ground + wallride + grind] + [grind + long wallride + ground] + ground + finish line |

|

Presentation with new fragmentation + repetition + expansion + framing |

Table 3: Sequence of Challenges with Indications of Formal Processes.

Figure 8: expanded wallride, end of section 3. Click image to enlarge.

Between Structure and Feeling

Let us pause to reflect on our intermediary results. Where does this path in musical thinking lead us? Regarding our table, structuralists from the school of Roman Jakobson could say that the level operates in terms of paradigms (selections) and syntagms (combinations). It selects one out of three kinetic actions in order to combine them into a varied syntax. “Epic Falls” would then be a textual structure that creates non-semantical meaning by selecting out of a pre-given repertoire of possible elements and combining them while adhering to certain syntactical rules (here: patterns). Such inherent rules in every structure remind us of the “elective affinities” underlying every musical composition. Consequently, a structuralist could say that we are describing the game’s language, and our analysis remains well within a literary paradigm of analysis, even if we choose to phrase it slightly differently. This contention is appropriate, but it tells us that we must go beyond the description of structure.

The table abstracts from the experience of play, so it resembles a musical score with indications of the formal processes. Until now, we ignored the fact that every musical structure correlates with “affective ideas” [6]. What we gained in our comprehensible structure is a notation; what we have to strive for, however, is a description of the affective process. Consider first the task of the musical performer who strives to bring out a piece’s affective ideas. The English language calls subsections of symphonies and sonatas “movements,” indicating that larger-scale musical works take their listeners, without physically displacing them, through a veritable journey of musical sounds. The performer strives to color every station of this musical journey to the best of their abilities. We often see in their facial expressions how pianists seem to be taken away by the vivacity of their performance as they try to realize the different movement qualities of a sonata. Embedded within the piece that they are actively trying to produce, the pianist cannot assume a standpoint outside of it because they must follow the musical force that they are invoking. In the same spirit, psychologist Daniel Stern studied experiential temporal intensities of any kind as “dynamic forms of vitality” by describing them as “felt experience of force -- in movement -- with a temporal contour, and a sense of aliveness, of going somewhere” (Stern 2010, p. 8). Similarly, Jan-Hendrik Bakels called the experience of digital games, an ongoing auto-affectivity, a self-affection, “a reflexive experience of one’s own affectivity that, while unfolding, is shaped by the very subject that experiences it” (2020, p. 91).

In our context, the challenge for an analysis of affective ideas is to intertwine the analysis of formal structures with the description of their experiential nature. Like in musicology, the scholar can be educated by the musical score but must learn to listen independently from it. In our case, the structural table can show us the way, but it can never replace the description of play’s affective process.

Flick and Hold

The structural breakdown of Epic Falls reveals patterned transformations of play -- but structure alone cannot account for affective experience. To grasp the full scope of ludic form, we must also attend to the dynamics that emerge through player gesture and perception. We have gathered that a basic pattern exists in this level, which is framed, fragmented, extended, repeated, liquidated and expanded throughout the level correlating with a rhythm emerging through the inputs. Intrinsically connected to this pattern and rhythm are two player gestures -- flick and hold. Player gestures are the actual player’s motions on the controller, not the movement of the virtual character. Both belong to the form of virtual movement insofar as the finger gesture modulates the flow of movement. Not to be mistaken for an “input,” the player gesture is more than a mere transmission of a signal to the game hardware. The player gesture is the physical means through which the player comes to act in the virtual space; it is a point of cumulation in the perceptual process. A simple flick with the left analog stick commands an ollie (a jump). Holding the left analog stick downwards when on a rail or a billboard commands a basic grind (called backsmith grind) or a basic wallride (called backside wallride). More skilled players can rotate the left analog stick before flicking to perform advanced and special tricks. The principle of time-critical flicking and holding thus holds true even in the higher-skilled behaviors of play.

How can we characterize flick and hold? The flick on the controller resembles the pop of a real skateboard which is one of the sub-movements of an ollie [7]. Like a skateboard that shoots upward when it is correctly tapped on its tail, the analog stick automatically goes upward, resetting back to the neutral position after a downward impulse. In OlliOlli World, the jump happens exactly at the point of release, no matter how long the preceding downward input. Flicks are afforded whenever the playable character must change between terrains. In the fragmentations of the basic pattern, repeated flicking creates a staccato rhythm. The hold, by contrast, is a particularly interesting input mechanic because, somewhere between action and non-action, it extends an action through a continuous yet non-challenging effort. Holding also speaks to the feeling of being carried away in this level -- carried away from the shape of the rail that propels oneself forward, yielding a strong advancing surge. The level’s affective rhythm is defined by accelerating while grinding (holding), which recurs at the start of most patterns. Grinding in real skateboarding is a finely-grained feat of bodily balance. By contrast, grinding in this level resembles riding a rollercoaster in which acceleration and deceleration relate mostly to the shape of the ramp. The thrill of being shot upward like a cannonball produces a faint, visceral nausea, an effect that players prone to motion sickness will feel deep in their guts.

It is an elegance of OlliOlli World’s game design that flick and hold usually combine into a single gesture. Letting go of a hold means to flick. In other words, holds prepare flicks, and the flick becomes nothing more than the release of a hold. In grinding, for example, the hold builds up tension while the flick releases it -- quite literally, bringing the analogue stick back to neutral and sending the virtual skater into the air. A minimalist action scheme, the combination of these two gestures makes it possible for the player to focus primarily on the left thumb while the virtual avatar shoots away at high speed.

The relation between hold and flick correlates with the relation between hold and release, tension and relaxation. Interestingly, the developers employed an image effect to accentuate this affective experience. Whenever we enter a rail, the virtual camera dollies out, making the character smaller and a larger portion of the environment visible, only to dolly in again when the character approaches the upward bend. Here, the image itself accentuates the critical location calling for a flick. Likewise, the time-critical release to exit wallrides causes the virtual camera to dolly out slightly, paralleling the release with the widening of the perspective. Most clearly articulated in the expanded wallrides, the camera dollies out to a maximum, diminishing the skater into a small figure, while opening a panoramic view of the mountain chain in the background (see figure 7).

Here, the hold is at its most restful like a slow breath-out from the bottom of one’s lungs. Ironically, restfulness happens not in the ground sections but in the highly elevated expanded billboard sections. The expansion of the wallride converges with the expansion of one’s perception, stretching into wideness rather than focusing on the narrow point of an upward bend rail. Suspended is the time-critical thrill in favor of a continuous release. At the concluding ground section, the camera returns to its original position, suspending the dolly-in and dolly-out. After crossing the finish line, motion comes to a halt and so does the visceral sense of movedness in the player. The impression of movement persists for some time until after the virtual movement has come to a stop, similar to how the body feels after a long train ride.

Our structural analysis showed how the level shaped an ongoing stream of movement, whereas our affective analysis showed how the level realizes an organic flow tension and release that Hanslick described as “affective ideas.” As mentioned, both go together and so I believe that our affective description gives us a new perspective on the structural forms within the level. A rhythmic modulation inheres this level: Accelerations prepare anticipations (whenever holds prepare flicks), intensifications (at flick-demanding passages), and releases (at the more restful passages of the expanding wallrides). As we have said, the basic pattern is introduced and habituated in the first section. Intensification marks the second section, while sections 3b and four are characterized by the release of the expanded wallrides. This rhythmic-affective modulation characterizes the player’s accommodation toward the level. In this fantastic vision of skateboarding, we realize an affective form that allows us to enact our vitality in the coming-together of playthings.

The Spectacle of the Ludic Form

In OlliOlli World, the form of digital play is the form of movement in the virtual. It has transpired, however, that virtual movement cannot be decoupled from the player gesture serving as its actual, bodily and human correlate. The ludic form would not be if it were not for the dexterity of the thumb in which the perceptual act culminates. When Brendan Keogh writes that the “videogame text” runs across “the player’s physical body, the videogame hardware, and the virtual bodies and worlds of the videogame’s audiovisuality,” (Keogh 2018, p. 47) he claims that meaning-making in the image always adheres to the embodied individual in front of the image. Indeed, the hardware and the player gesture must be considered indispensable parts of the simulation image. Rather than invoking a notion of text, however, I consider the concept of form far more suitable to capture the meaning-making process of digital play. The form of digital play is only conceivable in the particular dyad between body and image; it is this emerging in-between of an affective process that testifies how the real and virtual exist in direct relation to each other. In the focused act of play, when we successfully appropriate a game’s control schemes, the intentional experience belongs to the unfolding of the spectacle. In this view, the virtual represents a particular modality of image perception that is grounded in the physical body.

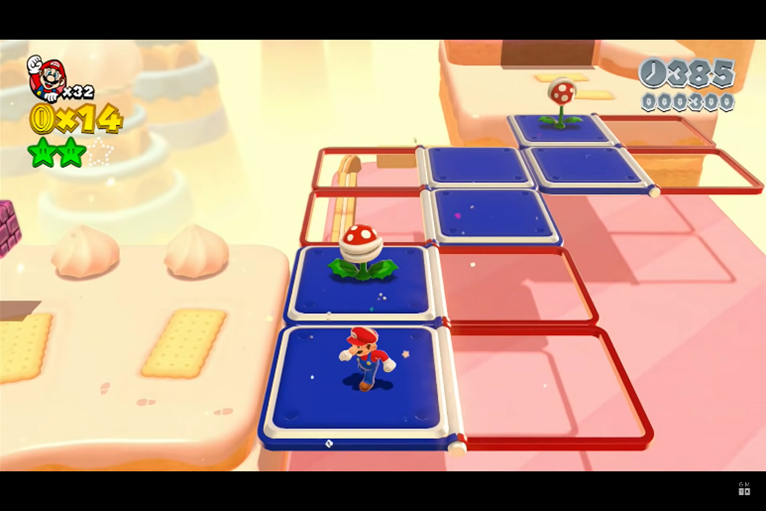

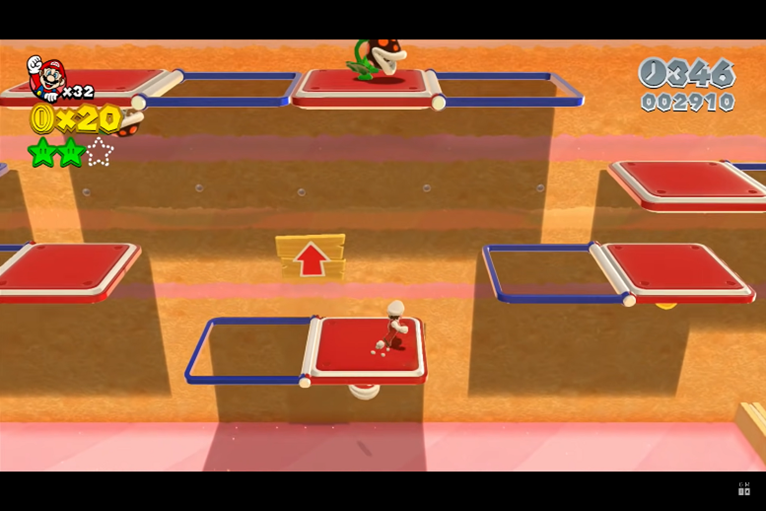

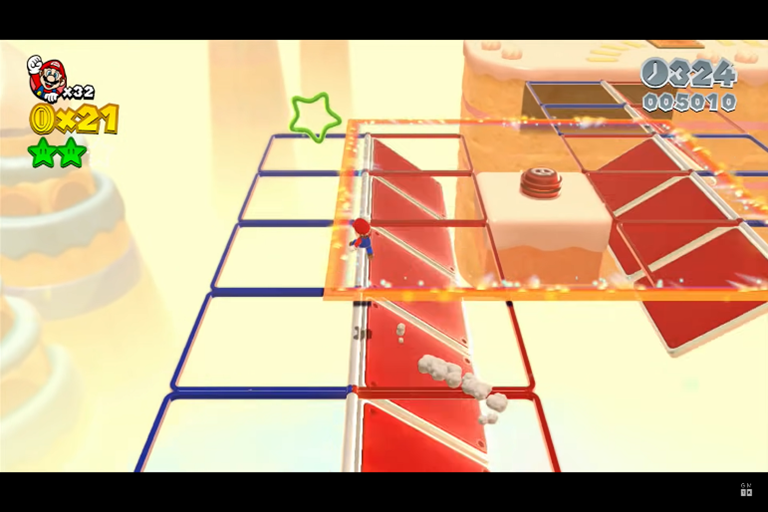

Beyond these media theoretical reflections, it remains interesting to ask how far we may go in the study of ludic form. I selected OlliOlli World’s level because of the 2-dimensional mode of representation, the linearity of level structure, and the stationary nature of challenges. How would we go about if we tried to transpose ludic form analysis to three-dimensional games, non-linear level structures, and games with mobile challenges? We can first refer to a video essay of YouTuber Mark Brown (2015), also known as Game Maker’s Toolkit, to see how form analysis can work in a 3D Mario game. He finds that every level in Super Mario 3D World (Nintendo, 2013), and most other Mario games, follows a formula similar to the one of the sonata form: “introduction (of a game mechanic) + development + twist + conclusion” (see figure 9). The level Cakewalk Flip has the player learn to jump on a set of flipping platforms. In the introduction, the challenge refrains from punishing the player so that they may safely explore the introduction of this game object. In the two-part development, however, the level makes the challenge fatal by sending the player down a pit whenever they miss a platform. Afterward, a more difficult challenge awaits where the player climbs a wall using the flipping platforms. The twist further increases the difficulty by introducing a bumper enemy, sending out damaging sound waves for the player to jump over. In the conclusion, the player is given a last go at the flipping platforms to showcase their skill through a flagpole jump, a common motive in Mario games where the player tries to hit the top of the pole. These structural descriptions could easily be supplemented with descriptions of affect.

Figure 9: introduction, development, twist, conclusion arranged in order from top to bottom; from Game Maker’s Toolkit (2015). Click images to enlarge.

But Super Mario 3D World gives us yet another example where movement is relatively linear, and challenges rest at a specific virtual place. Depart from this example, then, and consider action games like Dark Souls (FromSoftware, 2011). In these games, it happens frequently that enemies with their own offensive and defensive patterns come charging in masses toward the player. Movement clashes with movement as each gesture calls for time-critical countermovement. Not only does the place of the combat challenge vary, but so does its temporal frame. As Souls players know, fighting enemies means essentially learning rhythmical patterns. My heavy swing might be countered by their fast swing, and my fast swing might be countered by their well-timed parry. The difficulty of knowing when to act converges with the difficulty of knowing which action to take. Such combats of moving entities become exciting forms of “virtual dance” [8]. What matters here is the matching of gestures: each attack pattern of the enemy leaves a time window for a quick punishment and a subsequent defensive maneuver. From this angle, we regard the action game not as a fight between adversaries but as the active co-creation of aesthetic form between playthings-in-motion. Aesthetic questions gain relevance as describing the morphology of a fight’s form centers around the occurrence, variation, and development of movement patterns. The videogame image, in this sense, is not a reservoir of symbols, allegories, or signifiers but the place where the lively co-production of movement happens.

Lastly, the analysis of ludic form might bring us to appreciate e-sport performances in a new way. Focusing on the emergence of offensive and defensive patterns and their respective affective developments may make the thrill of the highest level of competitive play graspable in aesthetic terminology. Such an attempt was recently made by Frederik Rusk, Matilda Ståhl, and Sofia Jusslin (2022), who devoted a qualitative study to competitive team matches in Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (Valve, 2014), conceiving them as “emergent choreography.” My approach differs from such ethnographic methods (also found in Witkowski 2012) by bracketing the social dimensions of team interaction, along with verbal discourse and paratextual evidence. When I think of esports games with regards to my project, I think of the wonderfully orchestrated team fights in a high-level game of Dota 2 (Valve, 2013) in which players in teams of five each control a hero with four abilities. As each ability must be used in temporal and spatial precision, the move combinations emerging in a fight can become very sophisticated. A duo may battle a trio while the damaged characters flee from the scene, hunted by their opponents, detaching themselves from the fight, only to find that the presumed prey reconnected with their team and strikes back in full force. Team fights in Dota 2 bring forth manifold surprises as new offensive and defensive patterns emerge depending on the constellation of the heroes. In the most exciting team fights, delightful, polyrhythmic chaos ensues, requiring the players to improvise mindfully in the heat of the moment.

Clearly, working out a method of ludic form analysis in precision and cohesion would transcend this essay’s scope. Though the methodological challenges are considerable, perhaps demanding that we invent a method for every subgenre of the action game separately, I hope to have clarified that the study of ludic form deserves further academic pursuit, inviting comparative work that may one day yield a shared vocabulary for the kinetic and affective structures of play.

Conclusion

In this essay, I have argued that the form of digital play is best conceived as the development of movement in virtual space. By drawing on the tradition of musical analysis of form, I proposed that the videogame, like music, is an occurrent art -- it comes into being only through performance, it emphasizes a non-semantic sense, and it unfolds affective ideas through patterned intensities of tension and release. My analysis of OlliOlli World demonstrates how concepts such as presentation, fragmentation, extension, and liquidation can be adapted to describe the formal processes of gameplay. At the same time, it shows that the level’s form is grounded in an affective development structured by tension and relaxation, emerging from the tight interdependence between player gesture, virtual movement and the videogame image.

Thinking about games in terms of ludic form contributes a new vocabulary to game studies -- one that centers around performance, rhythm, and embodiment. It invites us to treat play as an aesthetic process in its own right, not merely as a vehicle for narrative or cultural meaning. In this sense, ludic form offers game scholars and designers what theories of musical form have long offered musicians: a framework for cultivating a more conscious perception of the medium. To analyze form is not only to describe how games are played and designed, but also to articulate how they think in movement, how they generate aesthetic experience, and how they open new ways of inhabiting the virtual.

Acknowledgements

I must thank Hans-Joachim Backe, Jan-Hendrik Bakels and Sonia Fizek for invaluable feedback on this essay.

Endnotes

[1] On the idea of absolute music, see Dahlhaus (1978), Pederson (2009), Bonds (2014).

[2] Readers might wonder why I left out ludomusicology in this essay. Even the most methodically creative ludomusicologists (Moseley 2016; van Elferen 2019) target the relation between gameplay and music, so it would have obfuscated the topic of my essay. Clearly, my pursuit is not a description of music, but a description of movement within videogames through the vocabulary of musical form analysis. In this regard, the method outlined here does not fall within the scope of ludomusicology.

[3] I have elsewhere supported Karhulahti’s typology by analyzing adventure games (Lukman, forthcoming).

[4] Quite clearly, this side quest implicates a shape of movement, one that is instantiated by this particular player. One could think about seeing the imprint of an “implied designer,” see van Mosselear and Gualeni (2020).

[5] Caplin’s term is elision, “a moment of time that simultaneously marks the end of one unit and the beginning of the next” (1998, p. 254). This is not exactly what happens here because the landing zone and next jump do not coincide directly, but the similarity shall suffice.

[6] The affective dimension of videogame play has been explored by many previous scholars, for example, Väliaho (2014), Keogh (2018), Crick (2011), Steur (2022), Anable (2018), Bakels (2022). What I want to emphasize, however, is how movement unfolds in formal patterns and that this kinetic-formal enactment cannot be decoupled from affect.

[7] Semioticians may say that the flick becomes an iconic sign referring to the pop of a real skateboard. For a semiotics of the game controller, see Blomberg (2018).

[8] See also Kirkpatrick (2011, pp. 119-158).

References

AlexWontCook. (2022). OlliOlli World: Air Over Nine Bees (Epic Falls). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DO-mGBDr71U. Accessed 18 December 2023.

Anable, A. (2018). Playing with Feelings: Video Games and Affect. University of Minnesota Press.

Bakels, J.-H. (2020). Steps toward a Phenomenology of Video Games: Some Thoughts on Analyzing Aesthetics and Experience. Eludamos. Journal for Computer Game Culture, 11(1), 71-97. https://septentrio.uit.no/index.php/eludamos/article/view/vol11no1-5

Blomberg, J. (2018). The Semiotics of the Game Controller. Game Studies, 18(2), n.p. https://gamestudies.org/1802/articles/blomberg

Bogost, I. (2007). Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. MIT Press.

Bonds, M. E. (2014). Absolute Music: The History of an Idea. Oxford University Press.

Caplin, W. E. (1998). Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Crick, T. (2011). The Game Body: Toward a Phenomenology of Contemporary Video Gaming. Games and Culture, 6, 259-269. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1555412010364980

Dahlhaus, C. (1978). Die Idee der absoluten Musik. Bärenreiter.

Eidsheim, N.-S. (2015). Sensing Sound: Singing and Listening as Vibrational Practice. Duke University Press.

FromSoftware. (2011). Dark Souls [Sony PlayStation 3]. Digital game directed by Hidetaka Miyazaki, published by Bandai Namco.

Game Maker’s Toolkit. (2015). Super Mario 3D World’s 4 Step Level Design. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dBmIkEvEBtA. Accessed 19 December 2023.

Hanslick, E. (2018 [1854]). On the Musically Beautiful. Oxford University Press.

Hepokoski, J., & Darcy, W. (2006). Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata. Oxford University Press.

Jud Cad. (2022). Epic Falls - All Mike’s Challenges of Cloverbrook (OlliOlli World 100% Walkthrough). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qisPJBzxKNM&t=67s. Accessed 18 December 2023.

Karhulahti, V.-M. (2013). A Kinesthetic Theory of Videogames: Time-Critical Challenge and Aporetic Rhematic. Game Studies, 13(1). https://gamestudies.org/1301/articles/karhulahti_kinesthetic_theory _of_the_videogame

Keogh, B. (2018). A Play of Bodies: How We Perceive Videogames. MIT Press.

Kirkpatrick, G. (2011). Aesthetic Theory and the Video Game. Manchester University Press.

Kirkpatrick, G. (2018). Ludic form and contemporary performance arts. Journal for Cultural Research, 22(3), 325-341. https://doi.org/10.1080/14797585.2018.1553673

Langer, S. K. (1953). Feeling and Form. MacMillan Pub Co.

Lukman, C. (2026). Configuring = Deciding! The Effort of the Strategy Game. Or: A Reconsideration of Pias’s Genre Distinctions. In Lars Grabbe, Patrick Rupert-Kruse, Norbert Schmitz (eds.), Ludic Images. The Moving Image between Game, Play and Interaction. Yearbook of Moving Image Studies. Büchner, 33-53. https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/106586

McDonald, P. D. (2024). Run and Jump. The Meaning of the 2D Platformer. MIT Press.

Moseley, R. (2016). Keys to Play. Music as a Ludic Medium from Apollo to Nintendo. California University Press.

Moten, F. (2003). In the Break. The Aesthetics of the Black Racial Tradition. Minnesota University Press.

Myers, D. (2010). Play Redux. The Form of Computer Games. digitalculturebooks.

Nintendo. (2013). Super Mario 3D World [Nintendo WiiU]. Digital game directed by Koichi Hayashida and Kenta Motokura, published by Nintendo.

Pederson, S. (2009). Defining the Term ‘Absolute Music’ Historically. Music and Letters, 90, 240-262. doi:10.1093/ml/gcp009

Pötzsch, H. (2017). Playing Games with Shklovsky, Brecht and Boal: Ostranenie, V-Effect, and Spect-Actors as Analytical Tools for Game Studies. Game Studies, 17(2). https://gamestudies.org/1702/articles/potzsch

Ratz, E. (1951a). Einführung in die musikalische Formenlehre: Über Formprinzipien in den Inventionen J.S. Bachs und ihre Bedeutung für die Kompositionstechnik Beethovens. Österreichischer Bundesverlag.

Ratz, E. (1951b). Erkenntnis und Erlebnis des musikalischen Kunstwerks. Österreichische Musikzeitschrift.

Roll7. (2022). OlliOlli World [Nintendo Switch]. Digital Game directed by John Ribbins, published by Private Division.

Rosen, C. (1980). Sonata Forms. W. W. Norton.

Rusk, F., Ståhl, M., & Jusslin, S. (2022). Understanding Esports Teamplay as an Emergent Choreography: An Ethnomethodological Analysis. Eludamos. Journal for Computer Game Culture, 13(1), 49-80. https://septentrio.uit.no/index.php/eludamos/article/view/6629

Stern, D. N. (2010). Forms of Vitality. Exploring Dynamic Experience in Psychology, the Arts, Psychotherapy, and Development. Oxford University Press.

Steur, D. (2022). Cinesthetic Play, or Gaming in the Flesh: Grasping Celeste by Adapting the Cinesthetic Subject Into a Phenomenology of Videogaming. Press Start, 8(2), 88-105. https://press-start.gla.ac.uk/index.php/press-start/article/view/216

Väliaho, P. (2014). Biopolitical Screens: Image, Power, and the Neoliberal Brain. MIT Press.

Valve. (2013). Dota 2 [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by IceFrog, published by Valve.

Valve, & Hidden Path Entertainment. (2014). Counter-Strike: Global Offensive [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game, published by Valve.

van Mosselear, N. and Gualeni, S. (2020). The Implied Designer and the Experience of Gameworlds. In Proceedings of the 2020 DiGRA International Conference: Play Everywhere, 1-16. http://www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/DiGRA_2020_paper_36.pdf

van Elferen, I. (2020). Ludomusicology and the New Drastic. Journal of Sound and Music in Games (2020) 1 (1): 103-112. https://doi.org/10.1525/jsmg.2020.1.1.103

Mitchell, A. and van Vught, J. (2024). Videogame Formalism: On Form, Aesthetic Experience and Methodology. Amsterdam University Press.

Wiesing, L. (2005). Artifizielle Präsenz: Studien zur Philosophie des Bildes. Suhrkamp.

Witkowski, E. (2012). Inside the huddle: The phenomenology and sociology of team play in networked computer games. https://pure.itu.dk/ws/files/109063661/Inside_the_ HuddleWITKOWSKIDissertationApril2012pdf.pdf