Wasting Time: Human Idleness and Durational Mechanics in Idle Games

by Liam MullallyAbstract

Idleness has often been cast as a dangerous habit, risking moral corruption to the individual and economic ruin to society. Against this, Marxist accounts of free time position non-productive free time totally distinct from accumulation as a utopian horizon. Idle games, often characterised as a “waste of time,” intervene interestingly in this political terrain. On the one hand, such games make claims on idle time, on the other, they operate durational mechanics which extend beyond game interfaces into a play with other temporalities (free time, labour time, etc.).

Within real-time media infrastructure, idleness offers an alternative critical lens to “slow media” for examining these games, which intervene upon non-productive time. I find two such games in-particular -- AdVenture Capitalist (2014) and The Longing (2020) -- mobilise idle mechanics to radically different ends: the first seeks to render idle time economically productive via monetization as a compressed form of consumption time; the other luxuriates in idle time, expanding the duration of consumption beyond its expected limits.

To clarify these strategies, I suggest drawing a distinction between the duration and operations of consumption. Duration (following Henri Bergson) describes the indeterminable time of consumption, while operations represent consumption rationalised into technical executions and transactions -- consumption as it might appear in a ledger, in statistics or in real-time analytics software. Monetized idle games, I suggest, embody the maximisation of operations alongside an attempt to minimise the duration of consumption -- and in this way capture an emerging tendency in digital culture. The Longing is by contrast radical in the inefficiency of its operations and the indeterminacy of its duration.

Keywords: idle games, mobile games, compression, duration, operation, automation, free time, productivity

Introduction

“Idleness… destroys wealth and corrupts men” (Beveridge, 1942, p. 170). Historically, idleness has often been portrayed as a moral failure that endangered the individual and society, as a malign counterpart to productive working time. The basis by which time spent not working might be characterised as unproductive is perhaps less clear today: more and more, our leisure activities find ways of rendering us productive. Much of our “free time” is occupied by the consumption of cultural products, which -- recalling the critique of culture industries (Adorno and Horkheimer, 2002) -- render granular engagements and idle cognition into units of consumption within a complex apparatus of interface, advertisement and micro-transaction. The granularity of mobile gaming, further troubles binaries between labour and “free” time. As Brendan Keogh and Ingrid Richardson have observed, a key affordance of mobile gaming is the capacity to play “while doing other things” (Keogh and Richardson, 2017). It is not only that time is occupied more and more by consumption, but that the very notion of idle, unproductive time has become hard to locate: few spare moments (in or out of work) escape co-option into some part of the cycle of accumulation.

Idle (or incremental) games are a relatively young videogame genre (now ubiquitous in the field of “free” mobile games) that explicitly play with the idea of idle time. Via a genealogy of the genre, I intend to clarify idle game mechanics and suggest that they facilitate a play with players’ (not only the games’) idle time. Two games offer distinct mobilisations of the idle: (1) Adventure Capitalist (2014), one of the most widely played idle games, which has innovated monetization and retention techniques now used widely by “free” mobile games; and (2) The Longing (2020), an idiosyncratic game (and highly inefficient commodity) that inverts the basic mechanics of the idle game towards an expansion of idle time. They demonstrate broader shifts in the technical constraints and aesthetic possibilities of real-time digital media, as well as the shifting economic and cultural status of idle time.

Idle time offers a critical alternative to notions of media slowness, recently appropriated into game studies but more broadly explored in film (Jaffe, 2014; Luca & Jorge, 2016; Vanderhoef and Payne, 2022; Fizek, 2022); on the one hand idle games like AdVenture Capitalist demonstrate techniques for rendering unproductive time productive (and consequently undermine the radical character of slow forms), on the other, The Longing -- even as it works against an intensification of time -- offers a more complex play with duration than simple slowness. A second intention of this article is, therefore, to contribute to recent literature on slow games.

Idle Time and Human Idleness

Before offering a genealogy of idle games themselves, I want to begin with an exploration of the apparent opposite of machine idleness: human idleness. Though this may seem like a detour, I intend to show that the mechanics of idle games concern our idle time as much as our machines’ idle cycles.

This concept of human idleness -- and of idle time -- has historically been entangled with notions of productivity or defined explicitly against productive working time. At the foundation of the British Welfare State, for instance, William Beveridge condemned idleness as one of five great societal evils. Idleness, he suggested, accustomed productive workers to inactivity and hence “destroys wealth and corrupts men” (Beveridge, 1942). A similar sentiment survives today in the tabloid figure of the “benefits scrounger,” or in political declarations of being “tough on benefits” (such as Kerr, 2017; Helm, 2013). In both cases, time spent unproductive is cast in moral terms, but Beveridge offers clarity over the contemporary discourse: his idle are those unemployed, not seeking work, and not either single mothers or widows -- in other words those not available to the market as labour or engaged in social reproduction -- and idleness is malign, to him, precisely because it entails a negation of productivity in pursuit of accumulation. When he attacks idle time, he does so specifically in the name of productivity.

A curious mirror of this treatment of idle time can be found in moral panics which broke out around 1980s video game arcades, which were characterised at the time as “wasteful” (Giddings, 2018, p. 772). Arcades, Seth Giddings has argued, entailed a “temporal economics,” in which payment and play were tightly intertwined, and as such were subject to scrutiny as a form of accelerated consumerism (Giddings, 2018, p. 772). This play resembled labour but was conspicuously unproductive (not work), instead oriented towards novel modes of consumption: an early innovation in highly granular monetization. The example suggests an ambiguous relationship between notions of idle, wasted and unproductive time, which do not always align as neatly as we might expect. Playing in arcades was characterised as wasteful in part because it rendered labour unproductive, but it was not physically idle -- in fact, the specific character of its activity (which resembled work) was integral to its characterisation as waste. All this time and activity -- we can imagine the concerned thinking -- would be better spent on something productive.

Conventionally, the opposite of labour time is not idle but “free time” -- that portion of the week not spent working. Indeed, expanding free time has frequently appeared as a demand of labour movements and socialist politics: Andre Gorz, for instance, places a shortening of the work week strategically as both a liberation from and within work (Gorz, 1989, pp. 22-3). Critical accounts challenge the autonomy of this time, which in Adorno’s words “is shackled to its opposite,” spent either recovering from the working day (in social reproduction) or consuming of culture industry products (Adorno, 1991, p. 187). Indeed, both Gorz and Adorno’s accounts contain conceptions of autonomous free time which somewhat resemble idle time, as time not directed by capital accumulation. In this tradition, the French politician Jean-Luc Mélenchon has advocated for the time “to live, to love, to do nothing if we like, to attend to loved ones; to read poetry, to do painting, to sing, or do nothing” (Mélenchon, 2023). In part, the arcade example highlights a tension between labour and consumption time. As coins are dropped into machines, the value of the labour behind them is realised, completing Marx’s basic formula for capital accumulation, M-C-M’ (the transformation of money into commodities and back into more money) (Marx, 1976). This formula requires labour, but it also requires consumption, and -- since both labour and consumption time draw from a single pool -- there is necessarily a tension between how these are parcelled out. Classifications of time as idle or wasteful can be understood through this paradigm as time that fails to meet economic notions of productivity one way or the other. Idle time is not strictly either consumption or labour -- but that which falls outside rationalisations of time entirely.

Giddings’ example of the arcade is an illustrative episode in the cultural history of videogames in which playing is viewed as wasteful. Of course, today’s gaming media look quite different. In the smartphone, we have a gaming device which remains on most of us all day (perhaps excluding sleep). Among other things, this very much broadens the scope of when, where and how long videogames can be played -- and entails a qualitative transformation to idle time.

Jonathan Crary’s 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep (2013), argues that non-productive time is continually under attack -- centrally in Crary’s case focused on the erosion of sleep. Sleep, Crary suggests, is characterised by its “uselessness and intrinsic passivity, with the incalculable losses it causes in production time, circulation and consumption” (Crary, 2013, pp. 10, 29). Most usefully for our case, Crary suggests the basis of this attack is a technological infrastructure -- of which the smartphone is a central part -- which allows time to become homogenous: an unending 24/7 periodicity -- composed of “incessant, frictionless operations” -- in which consumption is always possible (Crary, 2013, p. 29-30). Primarily, for Crary, this is an expansion (and intensification) of consumption time into as much of the day which is not spent working as possible: the total exclusion of idle time -- though this is not a term he uses.

Though Crary does not remark on it, 24/7 media infrastructures also efface work -- with smartphones in our pockets it is now easier than ever to procrastinate on shift. Consumption time leaks into labour time. And, since we can receive messages wherever we are, labour leaks into our free time. Discrete 20th century temporalities are therefore in crisis -- which is precisely the terrain into which idle games enter.

Though it remains underexplored in the critical literature (important exceptions include Sterne, 2012 and Steyerl, 2009), compression ought to be understood as a central technical, economic and cultural thread constituting this situation. (It is also -- incidentally -- a concept with some mechanical importance to idle games). Compression here refers to data compression, which has prefigured the media abundance which defines our present, as well as to the contraction of non-productive time as described by Crary (particularly apparent, perhaps, in the logic of “crunch” game development), but most of all to the economic concept, Marxist geographer David Harvey calls “time space compression” (Cote and Harris, 2021; Harvey, 1989, p. 147).

Time space compression describes an economic arrangement, a technical apparatus and a spatial regime in which circulation (via logistics or media) must accelerate to match production and consumption. The resulting acceleration is felt as a crush -- in Marx’s words, “die Vernichtung des Raums durch die Zeit [the annihilation of space through time]” (Marx, 1973, p. 539). The expansion of the railway across Britain, for example, functionally brought once distant localities close, erasing the cultural space between them (Schivelbusch, 2014). Harvey extends Marx’s analysis to (then) contemporary logistics and communication technologies: freight, planes, computing and especially satellite communication, which he describes as having “rendered the unit cost and time of communication invariant with respect to distance” (Harvey, 1989, p. 293) [1].

Time-space compression is spatial -- once impassable distances can be traversed (virtually, at least) trivially -- but it is also temporal. The expansion of the railway in the 19th century, for instance, not only erased localities but also displaced complex local time variations with “railway time” -- synchronized to that of London (Schivelbusch, 2014, pp. 48-50). If 20th century communications reached an endpoint of spatial convergence, time-space compression continued through the realm of duration. Contemporary compressions bring their own temporalities, compressed from the discrete, serial time of the 19th and 20th centuries. This compression plays out across the week: in work time, in free time and in the idle durations between.

Ostensibly, the idleness of idle games is machine idleness: the time in which the application is idle, and the player is away. But idle time -- during which they are played -- is also their terrain. Despite a superficial simplicity, the primary mechanics of idle games, as I will argue, are temporal: experienced in a play of duration, in Henri Bergson’s sense of the experience of time as it passes (Bergson, 1950) that extends beyond the game application to encompass its players’ idle time: time spent not somehow invested in the processes of capital accumulation or social reproduction. A central question for idle games, in my view, is what they do to idle time -- if they entail its destruction or expansion.

Idle Games and Durational Mechanics

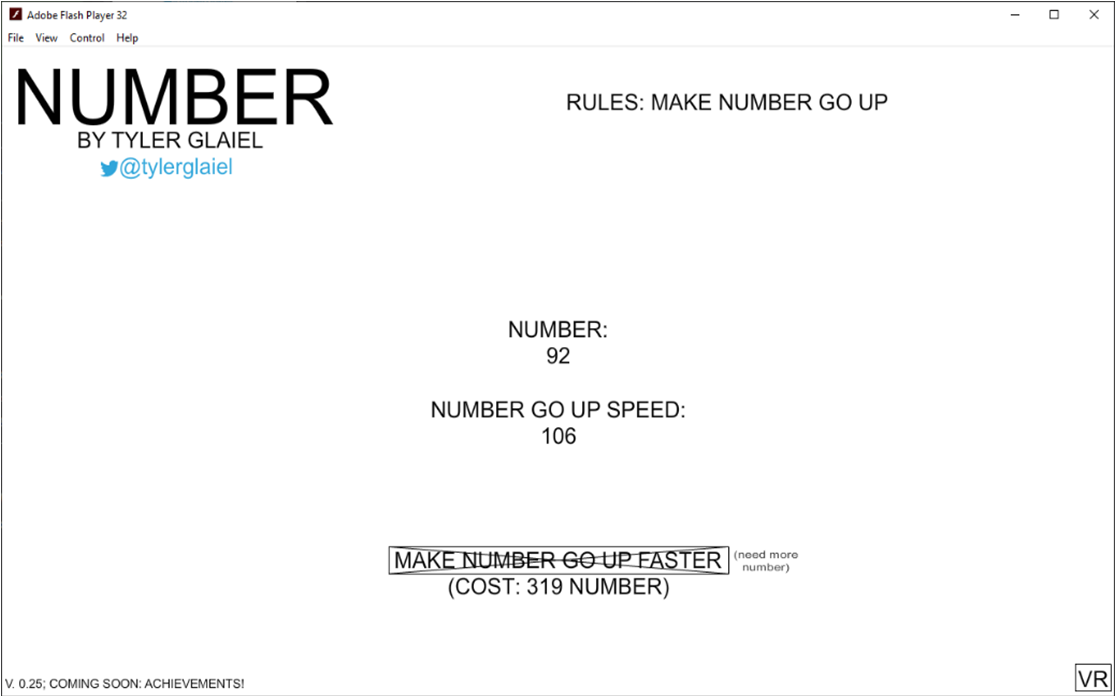

Mechanically, idle games seem quite simple. Number (2013), a barebones example of the genre, distils its core mechanics well. In the centre of the screen there is a number which ticks up slowly -- very slowly at first, by just 0.1 each second (figure 1). Soon, though, that number has reached 1 and a choice is offered: spend 1 to “make the number go up faster.” The number goes back down to 0 but climbs back up at a faster rate, reaching 1 in less time than it did before. Soon after the player is again given the choice to exchange the number they have gathered and make the number go up more quickly, but this time it costs slightly more. Before long the number is going up by 1 each second, then by 5, 10, 100, 1000, 10,000, 1*10^n, etc., but the cost of upgrading the “number go up speed” is also increasing, and it does so at a slightly faster rate, leading to increasingly long waits between upgrades. This core gameplay loop repeats indefinitely; for as long as a player keeps the game running in their browser.

Number is idle in the sense it continues in the player’s absence -- the number keeps going up regardless of the player’s interest, attention or interaction -- and it is incremental since the rate of growth is incremented -- each milestone offers an increase in scale but gives way to another greater horizon. In the simplicity of its core gameplay loop, Number distils the idle genre down to its most basic elements, but all idle games contain these mechanics to some extent.

Figure 1. Number (Tyler Glaiel, 2013). Click image to enlarge.

Interactivity in Number is limited to the click. The choice of whether or not to click this button -- especially when the apparent goal is to make the number climb higher, faster -- isn’t an especially good one. The obvious action is always to press the button as soon as it becomes available. The logic is inflationary: if there is a joy here, it is that of growth: watch the number go up, then watch it go up faster than it did before. Player interaction -- limited to the click -- completes the engine behind this growth. Without it the acceleration stops, and in this sense it is productive. Within the confines of a pure abstracted accumulation such a formulation is coherent, even if its banality appears self-evident. It offers the joy of accumulation for its own sake; a vision of the commodity finally removed from accumulation, “M-M', ‘money which begets money’” (Marx, 1976). But this offering is ultimately hollow and tends to give way to an impression that Number is, in fact, pointless. A waste of time.

Similar conclusions are borne out sooner or later in most of these games. Since gameplay is technically endless and structurally unvaried, players must disentangle themselves and make their own justifications for its ending. Paolo Ruffino has built an ethnography of these responses on discussion forums -- often characterised as “getting it done,” relinquishing players of the guilt of their sunk time (Ruffino, 2019, p. 218-9). The common impression Ruffino identifies, even among fans of the genre, that idle games are a waste of time recalls the 1980s reception to arcade gaming (Ruffino, 2019, p. 222). As Ruffino identifies, there is a clear case for the idle game as a kind of capitalist realist fiction, turning inflationary acceleration towards endless inertia (Fisher, 2009): AdVenture Capitalist simulates the productive engine of M-C-M’ but also seeks to literally render time productive via monetization. But they also appear to play in some interesting and novel ways with the time of their players.

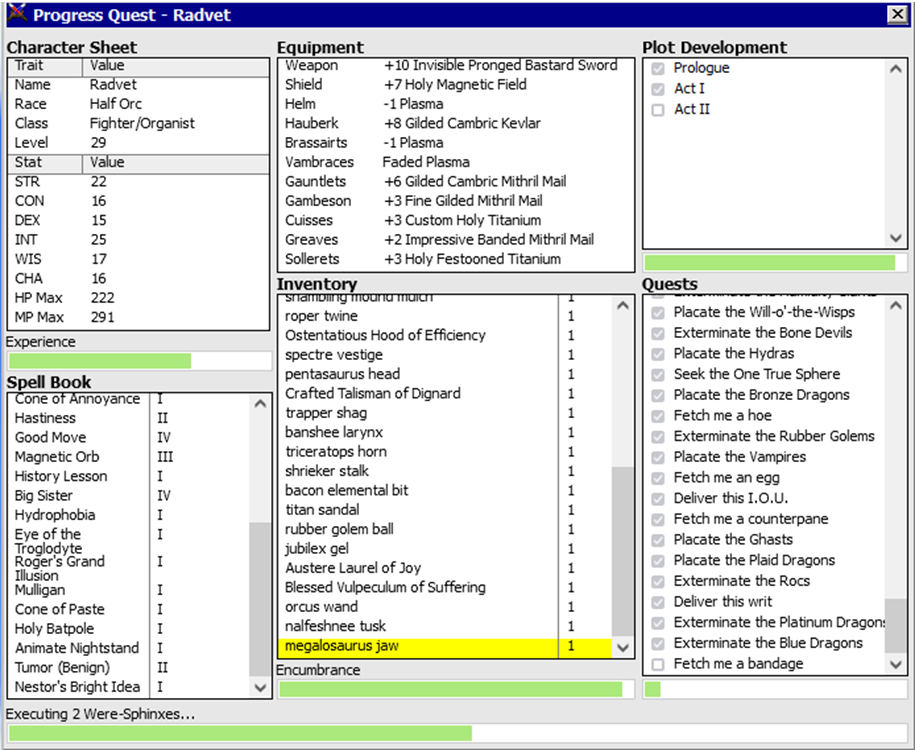

Examining these games in more detail will demonstrate that much of their gameplay operates outside of explicit play sessions: in the investment, arrangement and manipulation of time, in the meeting of the games’ internal clocks and in the players’ own sense of duration. In this, they hold some illuminating predecessors. Three games in particular help sketch this history out: Progress Quest (2002), a browser game developed by Eric Fredricksen as a parody of EverQuest, Cow Clicker (2010), a “playable theorization” of Facebook games by Ian Bogost, and Cookie Clicker (2013), a “non-game” created by Orteil drawing directly from both these games, and one of the first games to be identified as “idle” (Cecente, 2013).

The first of these games is Progress Quest, a parody of Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games (MMORPGs), which it reimagines as an endless series of loading bars. There is no user input in the game beyond an initial character creation screen, and in this sense the game plays itself, indefinitely (figure 2). Game mechanics -- combat, items, experience points, levelling up, act progression -- are all represented by randomly generated text and loading bars which scale endlessly. Some players claim online to have left Progress Quest running for years, with act numbers climbing indefinitely (like Number, at an increasingly slow rate) [2]. Having looked at the game’s source code, others discuss what would come first: the point at which levelling up would exceed the player’s life, or (more likely) when the game’s internal numbers exceed its engine’s capacity, causing crashes (Fredley, 2014). Even more than those that have followed it, Progress Quest eliminates interactive gameplay, adopting the form of an RPG without any of its narrative depth, or mechanical complexity. These are the costs, it suggests, of making an RPG like EverQuest into massively multiplayer online subscription service.

Figure 2. Progress Quest (Eric Fredricksen, 2002). Click image to enlarge.

The closest media analogy for Progress Quest, both visually and functionally, is an unreliable download progress bar (cited by Fredrickson as an influence on development) -- scaling up and down indeterminately, and never quite finishing (Klepek, 2021). But there is a pleasure to loading bars and to Progress Quest; Sonia Fizek has sought to explain the appeal of automated gameplay via Robert Pfaller and Slavoj Žižek’s concept of “interpassivity” (Fizek, 2018, p. 141). Idle games, Fizek argues, delegate much of their gameplay to the computer, leaving their player a passive spectator. In this psychoanalytic reading, the videogame’s passivity is transferred onto the player, who adopts it even as they still imagine themselves to be active -- effectively an automation of consumption (Fizek, 2018, p. 148). She therefore sees these games as exposing a false utopianism in interactivity:

The click seems to have lost its empowering dimension, if it ever had one... Interpassivity deconstructs interactivity-centred discourse and lays bare the illusory nature of interactivity. (Fizek, 2018, p. 152)

Having outsourced the labour of gameplay to their computer, the interpassive player exchanges agency for efficiency.

Released eight years later, Ian Bogost’s Cow Clicker is a “playable theory” (Bogost, 2012) of a different, albeit similarly exploitative, genre: social Facebook games (most notably FarmVille) [3]. No longer playable even in archival form (as a social game, it is intimately connected to Facebook, and not easily replicable elsewhere), Cow Clicker gave players a cow and allowed them to click on it (and the cows of their friends) once every six hours. Bogost included a premium currency, “mooney,” which players could buy with real money and exchange for new cow designs or to skip the click cooldown. Unlike contemporary idle games, the social network is integral to the game’s mechanics: a wider, more active network is the primary means to increment the rate of progress. Facebook games, as Bogost describes them, colonise networked relations as a resource for extraction. The player extracts value (cows, clicks) from previously unexploited social structures, while developer extracts higher order values: virality -- what Hito Steyerl has called a “value defined by velocity, intensity and spread” -- and monetization via adverts or microtransactions (Steyerl, 2009, p. 43).

Cow Clicker is punctuated by waiting. Even as players accumulate their friends’ cows, they must wait six hours before interacting with or profiting from them. The consequence is a continually deferred interaction, always on the other side of a six hour wait (conveniently close to the six and a half hours of sleep Crary has identified as the average for an adult in the US) (Crary, 2013, p. 11). As much as this deferment might encourage players to buy time, it also works as a call to action: your cow is ready to click -- time to open the game. Through this trick we let the game outside its browser, occupying idle brain capacity which is now spent in anticipation. Indeed, Bogost has noted distinctions between time spent playing and not playing the game degrade: “social games… destroy the time we spend away from them” (Bogost, 2012). That Bogost’s words so closely recall Marx’s (“destruction of time through space”) is neither purposeful nor incidental. Accumulation, of both in-game clicks and developer revenue, exists in circuit with player attention/ retention. Since the return of the player is the barrier to accumulation, their attention must be pulverized, worked into material that is amenable to accumulation (though this is not -- yet -- a compression as such, since Cow Clicker involves no logics of incrementation).

If they bill themselves as “parodies,” games like Progress Quest and Cow Clicker also function as schematics. Even in the histories offered by companies like Kongregate that focus on their monetization, idle games are described as a “parody” genre (Pecorella, 2015). Number is an excellent example of this tendency: popularized in industry and academic explanations of idle mechanics, it too functions as a playable theorization (in Bogost’s sense).

The mechanics of Progress Quest and Cow Clicker come together in Cookie Clicker (2013), the most widely played of several games to adopt the name “idle game” at this time, and an example in which the key mechanics of the genre were consolidated. In its basic gameplay loop, Cookie Clicker is much the same as Number, albeit with a different conceit: “baking” cookies, then reinvesting them to buy grandmas who will automatically bake cookies, and so on. Cookie Clicker expands upon this basic formula via a “prestige” mechanic, where the game can be started over with a fixed productivity boost. Just like Number, incrementation leads to a gradual slowdown: new thresholds take longer to reach as the game continues. This steady expansion is a consequence of the mathematical construction of gameplay, where the cost of upgrades increases exponentially but income rate only increases linearly. The “prestige” shifts the core gameplay loop into a pattern of reiteration of rapid acceleration, with each acceleration going further than the previous before the process can be repeated again.

The question of when to totally reset via a prestige is more complex than the one of when to invest: greater accumulations result in greater multipliers to the rate of future accumulation, but trading progress in too late comes at the cost of delaying this multiplier, and waiting too long or too briefly can cost the player time in the long run. Time is therefore invested into a future compression, which will be experienced as a release from the slowness they are currently enduring. This drive towards compression in duration is the primary (perhaps only) source of pleasure after the game’s initial cycles. More than either Progress Quest or Cow Clicker, Cookie Clicker’s idle mechanics demand player engagement: if a player does not return, in time to re-invest, the acceleration will be less spectacular, and accumulation depressed. And, since the game is always running, this dynamic extends beyond the game itself into players’ lives and passive cognition, occupying other idle and even labour time; as an engine of accumulation, Cookie Clicker is incomplete without its player, who must return to keep the engine running, and therefore directly implicated in its inflationary mechanics.

The complexity of such mechanics complicates Fizek’s account of interpassivity: it suggests that automated gameplay might relocate sites of interactivity, not only eliminate them; that interactivity and interpassivity can be intertwined, with pleasure not neatly derived from either. Moreover, there is an interesting parallel to be drawn between the automation of consumption -- as described by Zizek and Fizek -- and the automation of labour. For both Marx and Gorz automation compresses the working day and generates surplus time, which might be recuperated by capital or won by labour as free time; one question for the concept of interactivity is where exactly the time freed up by the automation of consumption gets spent. In factory games like Factorio (2013) or Satisfactory (2019), for instance, the automation of gameplay makes space for new kinds of interactivity, rather than simply eliminating it. Cookie Clicker’s idle mechanics similarly give way to an interplay between the game time and duration (as experienced by its players). This manifests in the tensions of waiting, counting; in the passing of time; in the gradually slowing of progress, followed by rapid compression. Meanwhile, achievements pile up to absurd and incomprehensible volumes.

But interpassivity remains useful for understanding idle games most of all in its inversion of the expected relationship between game and player. Cookie Clicker entails two distinct durations. First, in the game window itself players click to accumulate cookies, and spend these cookies to improve the rate of accumulation. Second, there are intervals between play sessions, in which the game continues to accumulate without the player present. Fizek notes that in idle games “gameplay is reversed, as if the ‘load’ screen was the actual game and the gameplay a moment to ‘wind up’ or ‘load’ the game” (Fizek, 2018, p. 152). The formulation neatly surmises the absurd pleasure of “completing” part of an idle game, just to reveal a scaled iteration, but also suggests that the game’s intervals might entail activity for the player as much as the game. Waiting in Cookie Clicker is more sophisticated than the six-hour timer of Cow Clicker, but it too is a retention tool, which compels players to return on their own, without notifications.

The Monetization of Idle Time

Following Cookie Clicker’s success, AdVenture Capitalist (2014), was first released on the website Kongregate, appropriating Cookie Clicker’s core mechanics and presenting itself as a satire of laissez-faire capitalism. Like Cookie Clicker before it, AdVenture Capitalist is an inflationary engine, in which early parochial ventures (lemonade stands) are continually displaced by new tiers of production (movie studios, bank and oil rigs), which bring with them accelerations in accumulation. AdVenture Capitalist’s main conceptual innovation over Cookie Clicker is to present this explicitly as a microcosm of capital accumulation.

AdVenture Capitalist’s mascot (figure 3) alludes to the monopoly man, and gestures towards a tradition of games satirising capitalism -- though Monopoly (originally The Landlord’s Game) offers a Georgist, not strictly anti-capitalist critique (Mueller, 2021). But while the tone of AdVenture Capitalist is ostensibly humorous, the form here is of pastiche, not parody.

Figure 3. AdVenture Capitalist’s Monopoly Man-esque mascot (Hyper Hippo Productions, 2014). Click image to enlarge.

Unlike monopoly, which critiques the imaginaries of liberal capitalism by making total monopolization its core win condition, there is no suggestion in AdVenture Capitalist that the promises of inflationary capital and boundless growth might be illusory. As Ruffino argues, the game “overidentifies with frictionless capitalism,” causing attempts at satire to fall short (Ruffino, 2019, p. 216).

Across multiple platforms, AdVenture Capitalist has been a site of repeat (largely non-gameplay) innovations to the genre: the introduction of advertisements, microtransactions and, in 2016, mobile release. Most of all, AdVenture Capitalist has demonstrated (and continues to demonstrate) the viability of Cookie Clicker’s durational mechanics for monetization. That this is done with some irony does little to impede its extraction; rather, AdVenture Capitalist engenders its players to spend money and attention with a smile and a wink (quite literally, from its cartoon mascot) [4].

Idle games are relatively cheap to build, maintain and expand; they do not need much labour (artwork, programming, sound design, etc.) to be viable, a fact well evidenced by the fact that the genre’s earliest examples were all developed by individuals as genuinely free-to-play side-projects. But this does not, on its own, explain the ubiquity of idle mechanics, which have been integrated into more complex and expensive games, and hybridized with a number of genres (RPGs, puzzle games, city managers among many others). Understanding the appeal of these mechanics to mobile game developers requires some attention to their mutation in free to download, but nonetheless monetized, idle games -- of which AdVenture Capitalist is the earliest example.

Player retention is seen by the mobile game industry, especially in “freemium” mobile game monetization models, as integral to maintaining long-term reliable revenue from microtransactions or advertisement (“Exploring Motivation,” 2017). A large body of academic work, primarily from behavioural psychology and computer science, has been dedicated to trying to understand and respond to this commercial imperative, formulated as a “retention problem” (Yee, 2006; Drachen, et al., 2016). Idle games encourage their players to exit the application for a period of time and return regularly to realise in-game accelerations in accumulation that will have accrued in their absence. If Cookie Clicker’s mechanisation of durational compelled players to return, AdVenture Capitalist renders this return productive by conceptualising it as user retention. Speaking at the 2015 Game Developers Conference, Anthony Pecorella, the game’s mobile producer, describes retention as a utility of idle mechanics: “time loses value without interaction,” he argues, and users are compelled to return to realise the value accrued in their absence (Pecorella, 2015). There is a window of time in which returning to the game is most-productive for in-game accumulation, aligning conveniently with the accumulative desire of the game’s developers for regular retention and engagement. When players return to the game, Pecorella suggests, they experience a “celebratory moment,” shifting the rate of accumulation upwards (Pecorella, 2015). “Retention,” which Pecorella invokes as the key indicator of the game’s success, “is off the charts” (Pecorella, 2015).

AdVenture Capitalist builds upon a model of mobile game design centred on “whales” -- individual users (often vulnerable people) who can be coerced into spending hundreds or thousands of dollars on in-game microtransactions (as recounted in an infamous industry talk: Jernström, 2016). Conventionally, such a model focuses on selling convenience to users, especially in the form of in-game progress, but AdVenture Capitalist instead sells time, either in the form a straightforward “time warp” (skipping e.g. 30 minutes into the future) or via a “speed multiplier,” which allows users to pay for a temporary acceleration to accumulation (Jernström, 2016; Pecorella, 2015). This is a subtle but important shift which entails a more complex logic of engagement. Pecorella notes it is much more palatable to players, especially those who would consider themselves “gamers,” who he notes “rebel against the social games and the Facebook games” (the notion of “paying to win”) (Pecorella, 2015). Instead, he suggests, players feel “ownership” over the decision to return to the game, and even to pay for acceleration, rendering them more compliant (Pecorella, 2015). These accelerations are offered either microtransactions or advertisements (though advertisements offer smaller accelerations), instantiating a strange situation where players invest attention time (watching ads) to achieve the fastest acceleration and reclaim the time it would have taken to reach some accumulative threshold (though of course this will always give way to another threshold). In the case of microtransactions, they are effectively buying back their own time, with money accumulated via time spent working. Via microtransactions or advertisement, the game leverages players into buying time -- something which is had been made scarce by both the compressions of precarious labour conditions and the data compression which already offers them a mass reserve of media with which to occupy inactive time.

And while it might seem innocuous, AdVenture Capitalist’s migration to mobile has accelerated the penetration of idle gameplay into time beyond the game -- inserting it into the waiting time between productive labour or consumption (Keogh and Richardson, 2017). On mobile devices, the game can be more present, more of the time, able to insinuate itself into spare, unproductive moments. This is compounded by the fact that, unlike for example Cookie Clicker which needs a browser tab to continue idling, AdVenture Capitalist calculates idle progress via elapsed time when you return to the game. As such, the game cannot functionally be paused and is always waiting to reward its player for returning. The move to mobile also has a modifying effect on such games’ “freeness.” Free browser games might often be accompanied by advertisements, in the form of banner or pop-up ads which surround the game window; free mobile games, on the other hand, offer opportunities for new kinds of monetization (hence a renewed popularity in the aphorism that: “if you aren’t paying, you’re the product”).

Pecorella characterises AdVenture Capitalist as distinct from Facebook games like Cow Clicker, but it is clear that it differs most profoundly for him in its ability to incorporate different kinds of players into its revenue stream. As in Cow Clicker, player time -- the wait between interactions -- is conceived as a resource with a real-life monetary value, but AdVenture Capitalist complicates this by rendering that time mechanical. As in Cookie Clicker, the play of waiting is integral to the game’s accumulative engine; by encouraging the player to game waiting the return becomes a lever at the players disposal, and one they activate willingly. The game spills into this intermediate duration, but unlike Cookie Clicker this time is not wasted, at least not for those seeking to exploit mobile games for profit or in terms of capital accumulation.

Like other idle games, AdVenture Capitalist is not just idle because it runs idly, in the phone's background, but also because it inserts itself into the idle, wasted time of its player. In doing so, it reopens this time to the possibility of productivite use -- primarily as consumption time, or as “attention,” itself a commodity which can be sold to advertisers (Citton, 2017). From the perspective of its developers, publisher and prospective advertising clients, AdVenture Capitalist is therefore not a waste of time at all. Rather, it is a incredibly effective monetization machine (realising consumption via microtransactions and attention as labour). All this is sold via an imaginary of frictionless accumulation in which there is no resistance to progress, no countermeasures or balancing: AdVenture Capitalist is mechanically impossible to fail, but equally impossible to win. Either end-state would be equally threatening to this illusion of continuity, as well as to the game’s consequent ability to generate revenue for its developers.

Unlike the long durations of work and free time presumed in 20th century critiques of free time, idle games operate with an intense granularity that allows them to enter even momentary idle durations and rid them of their dangerous anti-productiveness. In AdVenture Capitalist, this is a key affordance of interpassivity, as automation, which compresses consumption, allowing the game to be inserted into tiny parcels of unproductive time.

The Defence of Idleness

What hope is there for autonomous idle time when it is now so readily appropriated towards accumulation? AdVenture Capitalist offers a deeply cynical deployment of idle mechanics towards extraction and accumulation. A very different appropriation of the genre can be found in The Longing. Whereas other playable critiques and satires of the idle genre pick up on their mechanical simplicity -- as in Number -- or on the ecological impossibility of their limits -- as in Universal Paperclips (2017) -- The Longing departs from mainstream examples of the genre through its mechanical inversion of their compressive mechanical engine. The Longing works against the instrumentalization of free time and towards an abundance -- not of values -- but of idle time.

Whereas most idle games draw their players in with acceleration, The Longing (figure 4) instead confronts them with slowness. The game depicts the 400-day wait of its subterranean imp-like protagonist, “a shade,” who is instructed to awake an ancient king after this time, which elapses in real-time whether or not the game is active. There is no running, and the shade takes minutes to cross a single screen: a glacial place which stands as an affront to mainstream game design’s fast walking speeds, endless running, flying, vehicles and fast-travel mechanics. Mechanically, the game inverts idle acceleration: early on the player will come across a closed door, which takes five minutes to open; such waits get longer, incrementing towards extreme degrees of slowness. If the player seeks to rush the shade, they will respond plainly: “luckily I have plenty of time, so I’ll gladly wait.” Rather than getting faster, the game begins by incrementing towards more extreme degrees of slowness; waits grow from minutes to hours to days. You cannot really play the game compulsively -- since sooner or later it will tell you to go away for a week. And so, quite early on, The Longing confronts both the shade and its player with the task of enduring these waits, and it poses a question: what to do with this time?

Figure 4. The Longing (Studio Seufz, 2020). Click image to enlarge.

This question is central to the The Longing (which serendipitously was released shortly before COVID-19 lockdowns began). Waiting is neither innately joyous nor necessarily fun, and “the longing” of the game’s title is most obviously that of the shade: for company (of the king or others), for escape, for affection, for purpose -- all things they lack in their empty underground ruins. It is also somewhat seriously that of the player, longing for the time-crush of a more conventional game. The player could simply close the game and reopen it in 400 days, but there is also a lot to be found in the shade’s underground caverns if the player is patient: secret rooms, trinkets, coloured rocks and sheets of paper for drawing. The Longing hands its player a copy of Moby Dick and gives them more than enough time to actually read it. Many games deploy reading materials as one among many textual layers: narrative depth, exploration or visual fascination. In The Longing they are instead deployed as one among many ways of being idle, of passing time, of doing nothing at all. These things are not obviously productive -- in-game or in real life.

In the terms of automation, the interpassive mechanics in The Longing are different to those in other idle games, and quite strange: interpassive automation obstructs, rather than accelerate progress. What results is an abundance of ostensibly useless waiting time. Strictly, The Longing is a quite conventional commodity: it is purchased as a discrete unit of software for a one-off fee. Unlike AdVenture Capitalist it makes no attempt to innovate in the realm of accumulation: there are no real-time transaction mechanisms or data extraction (beyond those baked into platforms like Steam). But at the very least The Longing is a markedly inefficient commodity, in which the operation of consumption (the purchase) is stretched out into long durations of banal gameplay.

In this it resembles self-consciously “slow” forms that can be traced to the mid-20th century avant-garde, such as the structural films of the 1960s and 70s. “Slow,” as a genre or movement, has been deployed across a number of forms including television, literature, food, music and videogames, frequently as an attempt to resist the commodification and incessant operations of capital accumulation [5]. Strategies of course vary between forms, but -- to take just one example -- slow film is generally characterised by long, unpunctuated durations, relatively free of narrative or other trappings of mainstream cultural commodities (Jaffe, 2014; Luca & Jorge, 2016). It is seen to therefore be both formally difficult to appropriate into commodity circulation (a record can only accommodate around 50 minutes of sound, a CD 80 minutes, a standard DVD around two hours of video, etc.) and innately counterposed to the temporalities of consumption and to the rhythms of work and leisure time (24 Hour Psycho (1993) runs a full day in duration, to take an extreme example). Critics such as Ira Jaffe stress the “space” slow films generate for contemplation (of the film or reflexively, for the viewer) against the “haste” that characterises contemporary capitalism or the “distractions… characteristic of modernity” (Jaffe, 2014, pp. 5, 8). Accounts of slow games have tended to focus similarly on expansive and narratively uneventful game environments which refuse to “refuse to fill every moment with dramatic and quantifiable feedback” (Vanderhoef and Payne, 2022).

Unlike AdVenture Capitalist, waiting in The Longing is not just a moment before gameplay, but itself a space for departure, opportunities to read, to get distracted, to explore, to think or to do nothing -- much like conventional slow media. This situation is mechanically complicated, however, by a second mechanic, which players are left to discover on their own: when the shade is fulfilled -- busy enjoying themself -- times moves faster. Here the game enacts a more conventional temporal compression and departs from the temporality of slow media. If this slightly undermines The Longing’s slowness, it offers something altogether more interesting and novel. It enables a more complex play with duration: acceleration is conditional, and the player isn’t only given the power to accelerate (as in AdVenture Capitalist) but also to put the brakes on. The relationship between system and user is again inverted: play occurs in the trading off of interpassivity and interactivity. The Longing’s active slowness stops being an imposition and becomes a break: waiting is reconciliatory and purposeful, a necessary reprieve from a clock accelerating towards zero.

The Longing is therefore not, simply understood, a “slow” game, and involves a different set of aesthetic strategies than other examples. This might be understood, in part, as a response to broader changes in media infrastructures. Games are no longer circulated via discrete formats like CD and were never subject to pre-determined run-times. Likewise, distinctions between work and free time have become increasingly vague. Contemporary real-time media therefore bring presumed oppositions between slowness and commodity consumption into question. Mainstream idle games are just one example which upsets the aesthetic strategies conventionally associated with counter-cultural anti-commodity art such as slow media. AdVenture Capitalist, for instance, is expansive in length, non-narrative and ultimately entails long periods of waiting, but is nonetheless obviously and incessantly monetized. Indeed, there is a long history of games occupying extreme durations, even and especially on the cutting edge of real-time accumulation, most obviously in the endless expansion of MMORPGs like World of Warcraft (2004) (Castronova, 2005, p. 129-131) -- an early experiment in real-time monetization via subscription. One could characterize this genealogy, of which idle games are part, as an ongoing attempt to render slow media productive.

And so, if The Longing is suggesting an alternative to cheap-to-develop extraction-machines like AdVenture Capitalist, this must necessarily unfold in different terms to slow media: through inefficiency. The Longing appropriates mechanical engine of idle incrementation towards this: waiting as departure and duration as play, the proliferation of anti-productive idleness.

Operations and Durations in Digital Consumption

It may be worth returning to Crary’s characterisation of 24/7 media as composed of “incessant, frictionless operations” (Crary, 2013, p. 29). The different mechanical strategies of The Longing and AdVenture Capitalism reveal a tension between what might be characterised as the duration and the operations of consumption.

Durations, following Bergson, are indeterminate lengths of time as it is experienced. Operations, by contrast, describe the technical and momentary execution of consumption: the transfer of money, the extraction of user-data (including records of consumption) or parcelling out of advertisements. In the circuit of capital accumulation, consumption requires both an operation (the moment of transaction) and duration (time spent consuming). Technically, both duration and operation are transformed by digital media: duration can be massively expanded -- through substantial increases in storage capacity, through real-time media and through the affordances of interactivity -- while operations are no longer technically limited to a moment of exchange before consumption, or to sampled consumption statistics after the fact. Digital media allow for an ongoing, real-time rationalisation of consumption into operations. As such, in AdVenture Capitalist we see an attempt compress consumption as far as possible down to its operations -- into a granular form which might be parcelled out into idle moments, rationalising each as an instance of consumption (a watched advert, or a paid microtransaction). And, in doing, so, eliminating idleness.

The Longing is a far more conventional commodity than AdVenture Capitalist: it plays no role in pushing forward experimentation in real-time extraction -- once bought it is owned. What makes it an interesting example is precisely its inversion of idle mechanics towards a play of extended durations, which it promotes above the operation. The durations of The Longing are highly irrational, possibly expansive and frequently empty -- useless to accumulation. And so, in its wastefulness, The Longing attempts to preserve only the time to live, to love, to read poetry, to do painting, to sing, or to do nothing at all.

Endnotes

[1] Lisa Parks’ Cultures in Orbit mirrors Harvey’s position: in a “dialectic between distance and proximity,” she suggests, viewers experience an intimate and alienating transformation of space (Parks, 2005, p. 174).

[2] Several examples of player discussion of limits (or absence thereof) to the game can be found on forums like Reddit. For instance: https://www.reddit.com/r/ProgressQuest/comments/44bdci/im_ running_progress_quest_on_my_aw2_server_and/.

[3] Farmville has itself has been situated as a testing ground for data mining and early forms of surveillance capitalism (Wilson & Leaver, 2015).

[4] Yves Citton has described the conditions -- especially an overabundance of supply of conventional commodities -- in which attention has come to prominence as a key commodity of exchange (Citton, 2017, pp. 15-7).

[5] Though some “slow” movements, such as slow food (Petrini, 2004), only articulate an opposition to the global, highly processed character of accumulation, and are not oriented against capitalism as such.

References

Adorno, T. (1991). Free Time. In The Culture Industry (pp. 187-197). Routledge.

Adorno, T. and Horkheimer M. (2002). The Culture Industry: Enlightenment and Mass Deception. In Dialectic of Enlightenment (pp. 94-136). Stanford University Press.

Bergson, H. (1950). Time and Free Will. George Allen & Unwin.

Beveridge, W. (1942). Social Insurance and Allied Services. H.M. Stationary Office.

Blizzard Entertainment. (2004). World of Warcraft [Windows]. Digital game directed by Mark Kern and Chris Metzen, published by Blizzard Entertainment.

Bogost, I. (2010). Cow Clicker [Facebook]. Digital game directed by Ian Bogost.

Bogost, I. (2012). Cow Clicker: The Making of an Obsession. Ian Bogost. Available at: https://bogost.com/writing/blog/cow_clicker_1/

Broder, D. [@brodely]. (2023, March 31). Beautiful speech by @JLMelenchon on free time, explaining what the fight in France is really about [Video attached] [Post]. X. https://x.com/broderly/status/1641910171914891264?lang=en-GB

Castronova, E. (2005). Synthetic Worlds: The Business and Culture of Online Games. University of Chicago Press.

Citton, Y. (2017). The Ecology of Attention. Massachusetts: Polity Press.

Coffee Stain Studios. (v1.0, 2024). Satisfactory [Windows]. Digital game directed by Oscar Jilsén, published by Coffee Stain Publishers.

Cote, A. and Harris, B. (2021). ‘Weekends became something other people did’: Understanding and intervening in the habitus of video game crunch. New Media Technologies, 27, 161-176.

Crary, J. (2013). 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. Verso.

Crecente, B. (2013, September 30). The cult of cookie clicker: When is a game not a game? Polygon. Available at: https://www.polygon.com/2013/9/30/4786780/the-cult-of-the-cookie-clicker-when-is-a-game-not-a-game

Drachen, A. et al. (2016). Rapid prediction of player retention in free-to-play mobile games. Proceedings, Twelfth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Entertainment, 23-29

Everybody House. (2017). Universal Paperclips [Online Game]. Digital game directed by Frank Lantz, published by Decision Problem. Accessed January 30th, 2026. https://www.decisionproblem.com/paperclips/index2.html

Exploring motivation: why people play games for years. (2017, August 10) Kongregate Developers Blog. Available at: https://blog.kongregate.com/exploring-motivation-why-people-play-games-for-years/

Fisher, M. (2009) Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Zero Books.

Fizek, S. (2018). Interpassivity and the joy of delegated play in idle games. Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association, 3, 137-163.

Fizek, S. (2022). Introduction: Slow Play. In New Directions in Game Research II (pp. 129-146). Columbia University Press.

Fredley. (2014, October 14). Does Progress Quest end? StackExchange. Available at: https://gaming.stackexchange.com/questions/186642/does-progress-quest-end/186708

Fredricksen, E. (2002). Progress Quest [Windows]. Digital game directed Eric Fredricksen, published by Eric Fredricksen.

Giddings, S. (2018). Accursed play: The economic imaginary of early game studies. Games and Culture, 13, 765-783.

Glaiel, T. (2013). Number [Online Game]. Digital game directed by Tyler Glaiel, published by glaielgames. Accessed January 30th, 2026. https://www.glaielgames.com/number/

Gordon, D. (1993). 24 Hour Psycho. Glasgow, Tramway Art Centre.

Gorz, A. (1989). Critique of Economic Reason. Verso.

Harvey, D. (1989). The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change. Blackwell.

Helm, T. (2013, October 12). Labour will be tougher than Tories on benefits, promises new welfare chief. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2013/oct/12/labour-benefits-tories-labour-rachel-reeves-welfare

Hyper Hippo Productions. (2014). AdVenture Capitalist [Android, Web]. Digital game directed by Cody Vigue and published by Hyper Hippo Productions.

Jaffe, I. (2014). Slow Movies. Columbia.

Jernström, T. (2016). Let’s go whaling: tricks for monetising mobile game players with free-to-play [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xNjI03CGkb4

Keogh, B. and Richardson, I. (2017). Waiting to play: the labour of background games. Games and Culture 21(1), 13-35.

Kerr, C. (2017, August 20). Ignoring the Naysayers. The Sun. Available at: https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/4279364/marie-buchan-octomum-benefits-buys-horse-depression/

Klepek, P. (2021, September 1). Cookie Clicker’ wasn’t meant to be fun. Why is it so popular 8 years later? Vice. Available at: https://www.vice.com/en/article/n7bypk/cookie-clicker-wasnt-meant-to-be-fun-why-is-it-so-popular-8-years-later

Luca, T. and Jorge, N. (2016). From Slow Cinema to Slow Cinemas. In Slow Cinema (pp. 1-20). Edinburgh University Press.

Marx, K. (1973). Grundrisse. Penguin.

Marx, K. (1976). Money, or the circulation of commodities. Capital Vol. 1. Penguin Books (pp. 188-244).

Mueller, T. (2021). Rescuing Henry George: Optimization, Welfare, and the Monopoly Game in Harold Hotelling’s Economic Thought. History of Political Economy, 53, 927-947.

Orteil. (Classic, 2013). Cookie Clicker [Online Game]. Digital game directed by Julien Thiennot, published by Ortiel.net. Accessed January 30th 2026. https://orteil.dashnet.org/cookieclicker/

Parks, L. (2005). Cultures in Orbit: Satellites and the Televisual. Duke University Press.

Pecorella, A. (2015). Idle Games: The Mechanics and Monetization of Self Playing Games [Video]. GDCVault. Available at: https://www.gdcvault.com/play/1022065/Idle-Games-The-Mechanics-and

Petrini, C. (2008). Slow Food Manifesto. Available at: https://www.slowfood.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/slow-food-manifesto.pdf

Ruffino, P. (2019). The End of Capitalism: Disengaging from the Economic Imaginary of Incremental Games. Games and Culture, 16, 208-227.

Schivelbusch, W. (2014). Railway Journey: The Industrialization and Perception of Time and Space. University of California Press.

Steigler, B. (1998). Technics and Time, 1: The Fault of Epimetheus. Stanford University Press.

Sterne, J. (2012). MP3: The Meaning of a Format. Duke University Press.

Steyerl, H. (2009). In Defense of the Poor Image. e-flux Journal, 10. Available at: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/

Vanderhoef, J. and Payne, M.T. (2022) Press X to Wait: The Cultural Politics of Slow Game Time in Red Dead Redemption 2. Game Studies, 22(3) https://gamestudies.org/2203/articles/vanderhoef_payne

Wilson, M. and Leaver, T. (2015). Zynga’s FarmVille, social games, and the ethics of big data mining. Communication Research and Practice, 1, 147-159.

Wube Software. (1.0, 2020). Factorio [Windows, macOS, Linux]. Digital game directed by Michal Kovařík, published by Wube Software.

Yee, N. (2006). Motivations for play in online games. Cyberpsychology, Behaviour and Social Networking, 9, 72-775.