Neoliberal Space and Deleuzian Perception: The Schizophrenic Gaze of Cruelty Squad

by Maxim Tvorun-DunnAbstract

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus envisioned the enigmatic and conceptual character of the schizophrenic; a figure whose gaze offers a rejection of the unconscious structures of social perception and the social productions of space which have conditioned us to the world of contemporary capitalism. Recognizing the potential for interactive video games to simulate the uncoded pure expression of Deleuze and Guattari’s idealistic hero, this article reads Ville Kallio’s 2021 game Cruelty Squad as a ludic exploration of this liberatory perception. Utilizing Deleuze and Guattari’s precursor, Georges Bataille, this essay discusses the ways in which Cruelty Squad’s schizophrenic perception envisions a deterritorialized, non-dualist world underneath capitalism’s desire-producing spaces.

Keywords: Anti-Oedipus; Gilles Deleuze, Georges Bataille; video games; Silicon Valley

Introduction

Anti-Oedipus (Deleuze and Guattarai, 1983), is a complex and controversial treatise of psychoanalysis, rejecting all unconscious structures through which we posit, perceive, categorize and repress the world around us. It is a polysemous and polyamorous text, flirted with by both revolutionaries and reactionaries. Recognizing the productive force of desire, the manuscript’s enigmatic hero lies in the conceptual character of the schizophrenic. Although fundamentally misrepresentative of real-world persons on the schizoaffective spectrum (see Woods, 2011), Deleuze and Guattari position their conceptual figure as one who “scrambles the codes” which seek to contain and organize our desires, and who lets loose their uncoded desires in such force as to rupture the limits of capitalism’s desire-producing machinery.

Capitalist space abounds with desire-producing machines. Today, advanced psychological research is operationalized to methodically calculate levels of colors, sounds, smiling faces, sex appeal and likeness to food or cute animals to tap directly into human perception and longings, such that we redirect our quest for fulfilling desires through means which syphon exchange value towards the bourgeoisie. Perhaps more effective than all other forms, the digital spaces of video games represent the production of desire at its most totalitarian, with a history of game design and commodification built directly from the behaviorist research of B.F. Skinner (Yee, 2006). Yet video games may also prove the most subversive medium, whose direct interface with the player allows the immediate engagement with geographies, which would otherwise be relegated to vicarious observation or still contemplation in literature, film and painting.

Recognizing the potential for playable experiences which may realize the uncoded pure expression of Deleuze and Guattari’s “schizo” hero, this article turns to Ville Kallio’s title Cruelty Squad (Consumer Softproducts, 2021) as simulation of a Deleuzian perception which seeks to unbind encounters with space from capitalism’s repressive codes. Set amongst shopping malls, cruise ships, startup offices, casinos, hotels and suburbia, Kallio’s work critically engages with digital media’s role in reproducing capitalist relations to space and offers an alternative oppositional perception seeking to liberate space from enclosure and exchange. Utilizing Deleuze and Guattari’s precursor, Georges Bataille, I discuss the ways which Cruelty Squad’s schizophrenic gaze decodes desire from capitalism’s spaces of production before finally articulating how Kallio positions Cruelty Squad as a warning against the “neurotic” consumer-player.

Bodies without Organs, Stores without Products

As articulated by Henri Lefebvre (1991), the contemporary spaces of consumer capitalism are a product of collective social production, occurring at all stages of development, construction, use and representation. Through these acts of social production, natural environment becomes territorialized into unconsciously presupposed locations. Through the language of Anti-Oedipus, we can think of spaces as bodies without organs; as undefined environments which are socially formed into arrangements which appear to us a “natural or divine presupposition” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1983, p. 10). The shopping center does not become a shopping center only because designers constructed it but is instead the result of collective production and maintenance of social relations and design motifs (Gottdiener, 1995, p. 86), which form the perception of a space over the material presence.

Images of consumer locations socialize us, provide maintenance for the expected interactions with a location and its contents, and affirm the desirability of what is displayed within the image. The proliferations of images of consumer spaces are fully in keeping with the social production of these spaces. Observation through the medium of film appears analogous to the encouraged act of window shopping (Friedberg, 1993; 2006), and fictional recreations of shopping centers in La Dolce Vita’s (Fellini, 1960) studio-built Via Veneto appear as naturally to us as any real-world commercial street -- perhaps even more so, with the filmic space lacking any messy human interaction that may sever us from the hyperreal.

However, representations of consumption come into friction when their appearance moves beyond the medium of visibility and enters interactability. While games have included representations of shopping spaces for decades, there has typically been a degree of separation between the physical presence of their 3D spaces and player’s ludic engagement with these spaces. Shopping as a game mechanic has primarily persisted as a function of abstracted 2D menus rather than haptic interaction. Interaction with three-dimensional space is dictated through what possibilities are afforded by gameplay mechanics. The player of a shooter game is encouraged to actively engage with the spaces of combat in complex manners, utilizing level verticality, ammunition placement and enemy interactions. Research on videogame neuroscience has demonstrated players of 3D shooters show increased development in brain areas related to spatial memory (Momi et al., 2018). Yet, while videogame violence regularly takes place in shopping centers, shopping as an activity remains much less complexly tied to these spaces, which are often divorced from the immersive 3D spaces of games and relegated to extradiegetic 2D menus.

In Lehdonvirta’s (2012) history of digital consumption, he notes the origin of computer-based shopping simply adapted previous models of on-paper retailing, digitally recreating 2D catalogues rather than visualizing inventories within three-dimensional environments. This format of digital-paper shopping seems to have remained intuitively the de-facto mode of engagement with consumption in gameworlds decades on, even when detailed recreations of shopping spaces are constructed. Even in the Yakuza (Ryu Ga Gotoku Studio, 2005-present) and NBA2K franchises (Visual Concepts, 2005-present) which mold shopping into the urban fabric of their worlds through sponsorship tie-ins with real-world retailers, the navigation of these spaces exists only with respect to their placement within cities, and not between items on shelves, serving simply as locations to display catalogue menus. As Featherstone observes, in electronic media, “instantaneous connections are possible which render physical and spacial differences irrelevant” (cited in Denegri-Knott and Molesworth, 2010, p. 119). Thus, with rare exception, there is no need to relate purchasable objects with physical spaces, and the player has no need to find an item in a store, bring it to a counter, and purchase it with a medium of physical currency. Instead, shopping exists within an extradiegetic space displayed to the game player rather than the character inhabiting a virtual space.

Despite this disconnect, virtual consumer spaces persist. Some developers, seeking verisimilitude with daily living spaces, proliferate their games with shops full of products with varying degrees of functionality in the game world: from attribute-effecting armor and weapons in the town centers of fantasy worlds to social cosmetics serving only role-playing functions to mere placeholders of shopping spaces meant to cement a location as visually believable, even when devoid of interactivity. Virtual advertisements for fake products fill landscapes, reproducing capitalism’s desire-producing machinery, cleft of any means of exchange or fulfilment.

Perhaps most frequently, shopping centers serve as spaces of transgression in the power fantasy provided by games. In Grand Theft Auto V (Rockstar North, 2013) and the Payday franchise (Overkill Software and Starbreeze Studios, 2011-2023), players are invited to rob commercial spaces for objects and currency. In post-apocalyptic series like Fallout (Interplay Entertainment and Bethesda Softworks, 1997-present) or Dead Rising (Capcom, 2006-2017), players can delight in engaging with these spaces divorced from the social pressures that condition real participation, with the lack of living population allowing players to take goods as they please or misuse the space in spectacular fashions. This transgressive jouissance, however, only serves to reinforce the real-world rules of exchange in consumer spaces, articulating that the desires manufactured by shopping malls are in fact attractive even when their only in-game function is to be abstracted into currency to purchase further tools of simulated robbery.

Deleuze and Guattari envision social space freed from the desire-producing machines which constrain it; articulating how human capacities for creativity, expression and enjoyment naturally extend beyond the systems of imposed scarcity, manufactured dreams and fetishized commodities which abrasively form and limit it. The social production of space is a process contingent not only on representation within art and architecture but further composed within the individual experience of spaces. As a medium uniquely capable of producing ludic experiences (Cremin, 2016), games offer productions and transgressions of spaces as they socially exist and can realize relationships with the world unrestrained by the presupposed axioms of exchange (if only developers seek aspirations beyond verisimilitude).

Cruelty Squad, Bataille, and Immanent Experience

Seemingly continuing this trend, Cruelty Squad’s levels are set in a variety of consumer locations, from suburbia to the shopping mall, cruise ship and casino. While a store and even a day-trading stock market exist within the extradiegetic space of the game’s main menu, the abundance of 3D shopping spaces offers almost no interaction or products for the player to purchase. However, as I will argue, these representations of nonfunctional consumer spaces in Cruelty Squad do not simply perpetuate the social construction of spaces as other games have done but instead serve to actively decode paradigms of consumption and exchange from space.

Cruelty Squad was released in 2021 by Finnish artist Ville Kallio, under the tongue-in-cheek studio name Consumer Softproducts. Set in a heightened version of our contemporary dystopia, the society of Cruelty Squad is a hypercapitalist wasteland of exploitation and waste in honor of the market with power relegated to venture-capital funded tech firms. As diseases and ecological collapses abound, mass shooters run casually in the streets. The game’s visuals are an aggressively ugly aesthetic of jarring contrasts in color and patterns, which forcibly defamiliarize and abstract the geometries and textures of conventional spaces, as abstract bulbous mounds of flesh uneasily fill large portions of the player’s UI. Conventional game mechanics are reinvented, forcing players to relearn basic interactions of games. Where most games allow players to reload weapons by pressing the “R” key on a keyboard, Cruelty Squad makes players hold right-click and rapidly lurch the mouse downwards, as though they were pulling a lawnmower ripcord. Despite these purposeful idiosyncrasies, the gameplay draws inspiration from previous stealth-action games like Deux Ex (Ion Storm, 2000), Hitman (IO Interactive, 2000-2022) and System Shock 2 (Irrational Games and Looking Glass Studios, 1999). Once the player adjusts to Cruelty Squad’s oddities, the game becomes quickly enjoyable with its oversized UI elements seemingly fading from perception.

In Cruelty Squad, the player embodies a gig-economy corporate hitman, tasked primarily with assassinating tech CEOs who have squandered funds or whose deaths are financially useful to competing organizations -- as well as other inconveniences like politicians who support taxing the rich and environmental activists. Completing missions rewards players with further levels and in-game currency to purchase tools within the game’s main menu. As the narrative progresses, these hits become increasingly untied from corporate contracts, until in the final levels the player is rebelliously attacking financial institutions and abstract representations of capitalism itself.

At the heart of Cruelty Squad’s critique of capitalism, the game invokes a ludic discourse with capitalism’s role in socially constructing relationships to nature and space -- engaging with the perceptual filter separating the real from the hyperreal. Kallio positions capitalism as a barrier separating the player from a material immanence with the world. This is depicted through multiple references to Gnosticism within the game, whose cosmology posits that our perception of the universe was obscured by malevolent illusions. For instance, upon the player’s first fail-state the game announces: “DIVINE LIGHT SEVERED / YOU ARE A FLESH AUTOMOTON ANIMATED BY NEUROTRANSMITTERS,” invoking a division from the player’s experience and encounters with the immanent Real. The game features an intrusive screen-border emphasizing the limits between the player-character and the environment beyond them. Characters in the gameworld regularly transgress these limits and become environment, such as one target whose body has mutated into a bouncy castle. The player’s toolset abounds with grotesque biological extensions into the world around them, such as a grappling hook fashioned from the protagonist’s mutated appendix, and a double-jump mechanic rendered diegetically through the evacuation of shit and nondescript biological matter out of the player-character’s feet. As a means to restore in-game health, the player is offered a cannibalization mechanic to consume killed characters, violently transgressing boundaries of human flesh. In such transgressions of biology, the game openly invokes the works of philosopher Georges Bataille, and indeed an extended quote from The Accursed Share (1988a) is displayed at the game’s conclusion.

Throughout Bataille’s art and essays, but most visibly in Theory of Religion (1989) and Inner Experience (1988b), Bataille argues that the world exists in a state of nonduality, that all matter and energy exist in continuous flows, where “every animal is in the world like water in water” (1989, p. 19). Bataille alleges that the differentiation between objects, defined as “positing,” is an illusion derived from humans’ use of tools. He states that by subordinating material towards particular ends, “consciousness posits them as objects, as interruptions in the indistinct continuity,” and that, “the developed tool is the nascent form of the non-I” (1989, p. 27). From this perceptive separation of objects from immanent “base material,” Bataille argues that all further objectification emerged (Bataille, 1985). Proceeding from the objectification of material, humans come to objectify other living beings, and ultimately even concepts and ideas become objects in themselves. Bataille’s thesis in Theory of Religion claims that by recognizing that humanity has transcended from a mode of perception of the continuous world, which it cannot return to, this continuity has itself become objectified, subsumed under the categorizing label of “the divine.” Bataille positions that religion’s erroneous objective is the return to immanence through further structures of positing and transcendence through knowledge. In contrast, Bataille champions a rejection of transcendence, a call for “non-knowledge” reached in moments of preconscious “limit-experiences” of anguish or ecstasy, found in binges of drugs, alcohol, sex, laughter, or pain. Bataille positions these experiences as our only mode of perception into the nondual nature of the world and are therefore more human than the coveting of objects and knowledge which, according to him, serve only to alienate us from reality.

Where Bataille urged for a vision of reality clear of the structuring distinctions between subjects and objects, Anti-Oedipus called for seeing language, discourse and signs without the repressive structuring codes typified by the Freudian Oedipus complex. Bataille’s argument that the world exists in a nondual state “like water in water” appears similarly within Deleuze and Guattari’s texts. In A Thousand Plateaus, it is discussed that “the Earth -- the Deterritorialized, the Glacial, the giant Molecule -- is a body without organs. This body without organs is permeated by unformed, unstable matters, by flows in all directions, by free intensities or nomadic singularities, by mad or transitory particles” (1987, p. 40). They warn however that “there simultaneously occurs upon the earth a very important, inevitable phenomenon that is beneficial in many respects and unfortunate in many others: stratification,” in which the free-flowing material of the earth is separated and codified by human cognition and social practice. In Bataille’s promotion of immanent inner experiences -- a devotion to experiencing this “natural” world without the misleading transcendence of thought -- we might envision a radical interpretation of Deleuze and Guattari’s post-structural perception, as one where the mere positing of objects distinct from their environment serves as a repressive structure through which desiring flows may be misdirected. Just as Deleuze and Guattari find the experience of schizophrenics to be decoded from socially-produced perception, Bataille claims that “madness itself gives a rarified idea of the free ‘subject’ unsubordinated to the [socially constructed] ‘real’ order and occupied only with the present” (1988a, p. 58). In the remainder of this essay, I will articulate Cruelty Squad as a ludic exploration of this schizophrenic perception, in order to discuss how this vision reveals the faults and irrationalities in our social production of space -- the warped and perverted desiring organs embedded within the body of consumer culture.

The Liberatory Schizo

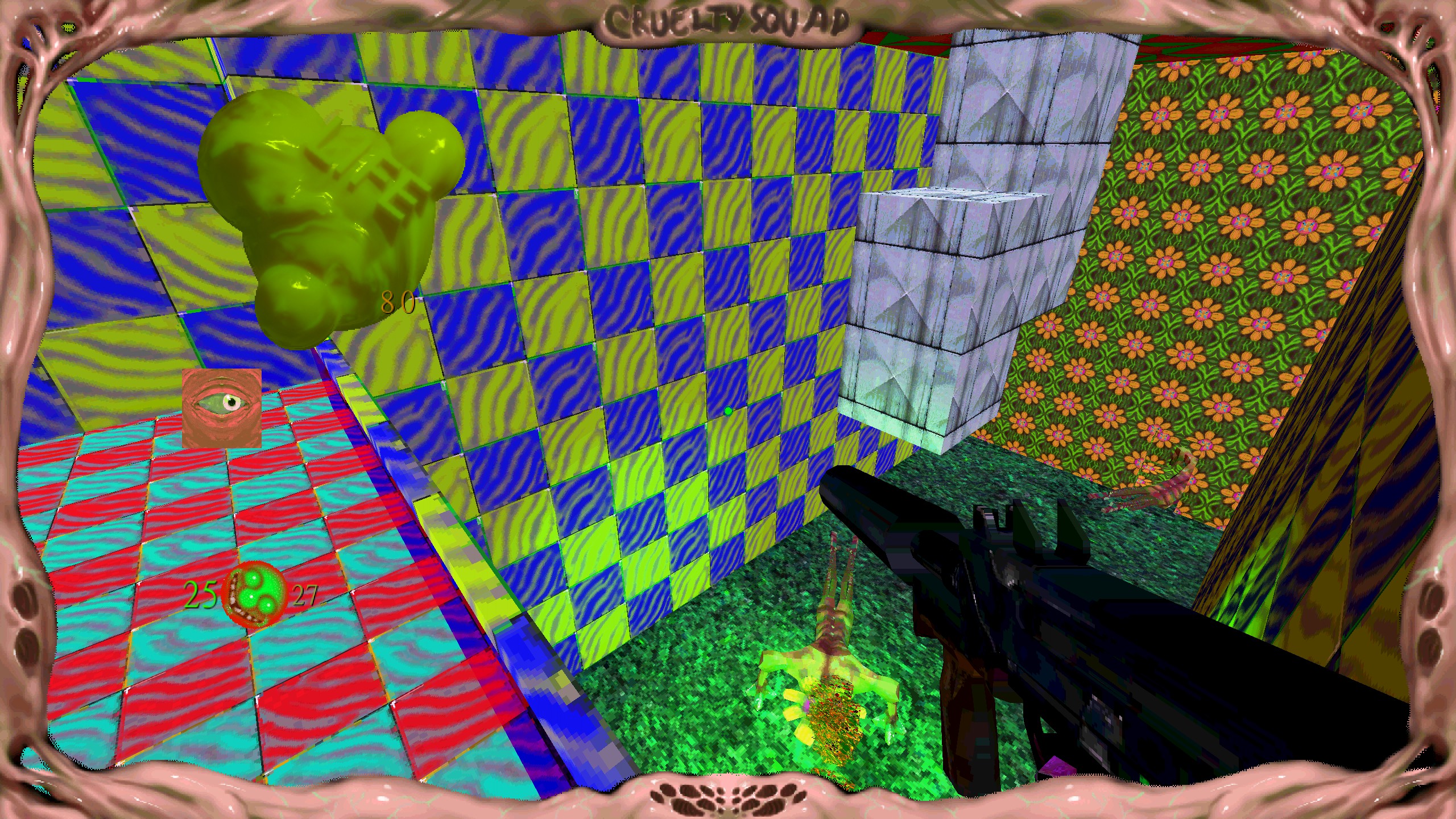

Cruelty Squad offers a visualization of this schizophrenic gaze, defamiliarizing spaces overcoded by capitalism into novel scrambled forms. Traversing the world of Cruelty Squad, spaces of consumption flow from quotidian locations into impossible non-Euclidean geographies and surrealist spaces of flesh and machinery. The gameworld abounds with faces integrated into walls and textures (the designs adorning in-game polygons), offering a heightened pareidolia where inanimate matter takes on organic qualities. The art style is a maximalist assault on the senses, with such constant contrasts and juxtapositions of color and design as to be all but unapproachable when viewed disconnected from physical play, yet through gameplay these abstract visuals become reorganized into a strange coherency. In the language of Anti-Oedipus, Cruelty Squad’s defamiliarization “deterritorializes” the social relations which overcode consumer spaces and “reterritorializes” these locations into new assemblages unbound by existing social codes.

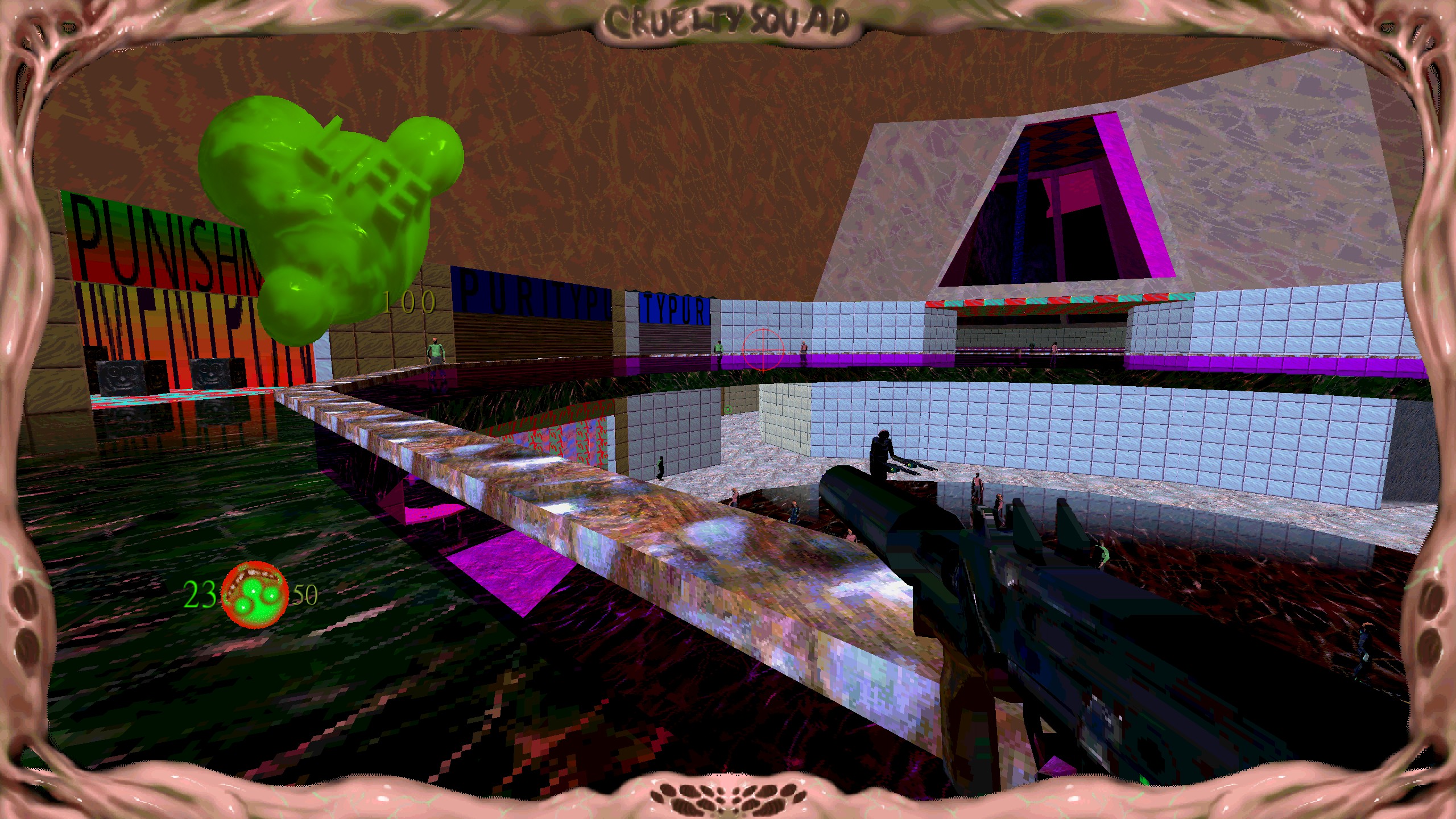

Figure 1: “Mall Madness.” Click image to enlarge.

Kallio’s deterritorialization of space is exemplified within the fifth level, “Mall Madness.” The level design parodies the layout of a suburban shopping mall, featuring several interconnected rotunda beneath skylight atriums. As Douglas Spencer critiques such spaces symbolic of neoliberalism, the circular environment appears designed to perpetually guide flows of desire towards sites of exchange:

In the atrial spaces of the public interior… vision is rendered confluent with the circuits marked by the exposed walkways, the strips of lighting, the panels and grilles ribboned around its interior surfaces. The eye is trained in conformity with a condition of elegantly modelled and perpetual mobility. There is no goal or destination for it to fix on. Vanishing points are difficult to discern… The neoliberal eye does not apprehend, calculate or gauge, it is enjoined to project itself into the play of movement presented to it, to surf the field of vision, reveling in the sensuous freedoms offered up to it. (2016, p. 158)

Yet vision in Kallio’s mall is interrupted. The player’s target on all levels in Cruelty Squad is perpetually seen as a red crosshair visible through walls, breaking through space as an always clear destination through which the player must gauge their location in relationship to. If guided by the mall’s circular walkway, the player will find there are no sites of exchange to be drawn to. Where one shop should be is instead a bright red space adorned with the label “PUNISHMENT,” stacked with giant cubes decorated in repeating textures of a smiling face. Following the rotunda in the other direction the player can enter a doorway leading to a lengthy straight hallway, unclear if this is a backroom or extension of the consumer space, the hallway floor eventually gives way to a groaning underside of the facility built in stone -- elsewhere behind the walls of the mall mounds of flesh grow out of the floor. Where some spaces are textured with the marble floors of a commercial center others feature abstract patterns or dirt and grass, with textures utilized so haphazardly across the space that it becomes impossible to visually delineate a dividing line between the mall’s public and private areas. As the player’s presence is policed (shot at) in all spaces, there exists no mechanical separations between spaces either.

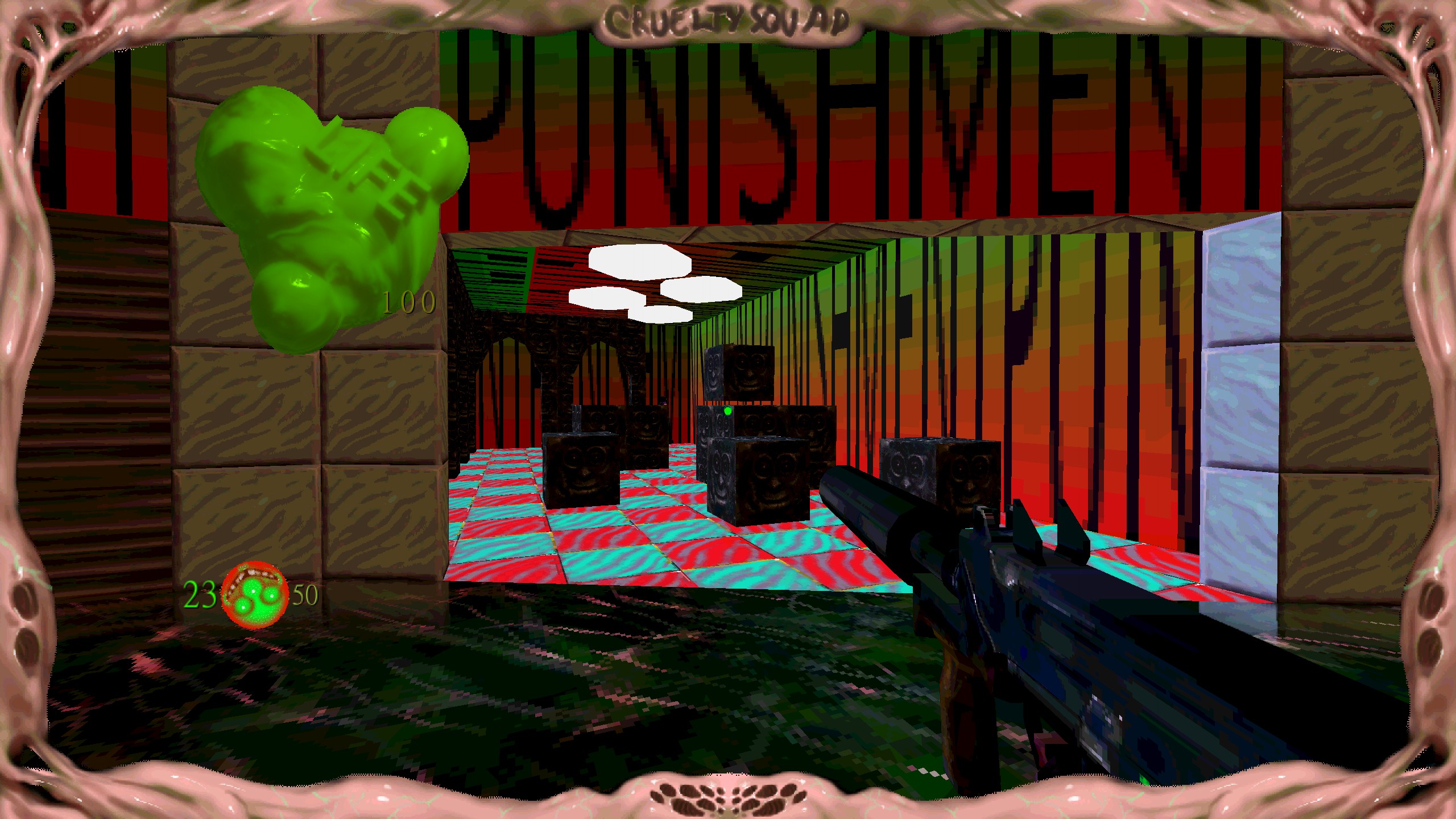

Figure 2: Intensities of mall. Click images to enlarge.

This impossibility to delineate public and private separates Cruelty Squad from the spatial relations of other games. In works like Hitman, players regularly transgress the line between public and private spaces, trespassing backrooms and service corridors to accomplish their goals. Yet, like with Grand Theft Auto’s aforementioned transgression of consumerism that paradoxically strengthened consumerism, Hitman’s transgressions are a similar power fantasy. Hitman visually delineates the line between public and private spaces and allows players jouissance in breaking these taboos. By acknowledging this spatial transgression as a taboo, however, Hitman reinforces the social distinction between public and private. In contrast, through Cruelty Squad’s wonton texturing, the distinction between public and private are made imperceptible. While the structure of the game’s shopping mall implies that some small corridors or shafts are a part of the private infrastructure of the location, there is little in visual design or game mechanics that differentiates these spaces from anywhere else inside or outside of the mall. There are thus no boundaries, only varying intensities of likeness to a mall, a state of becoming-mall that more often than not deterritorializes the space into abstraction.

Drawn by the bright red crosshairs of the target, applying a destination to interrupt the circuitous neoliberal space, the act of traversing the mall atriums becomes derailed from its circuits. The advanced traversal devices given to the player, such as the aforementioned appendix-based grappling hook or biohazardous double-jump, allows for casual and high-speed flow cutting straight through the circular space in a secant line. The player deterritorializes the rigid space driven by the desires set upon them by the game designer; shitting and shooting across an indistinct continuity of mall space. Through their traversal of space, the player comes to rapidly parse the sensory overload put in place by Kallio, entering a flow state. In this state, the game’s intrusive UI features, like the bulbous pulsing health indicator, perceptually fade away and a strange cohesion overtakes the messy visuals. The bright contrasting colors and wonton texturing of the world decodes the features of capitalist space, which are then recoded through gameplay as the player comes to parse the space not through access to points of exchange, but as a smooth space which the player is liberated to cut across towards their own ends.

Built in the Godot development engine, Cruelty Squad makes a distinction between usable objects, which are subject to the game’s physics (e.g. they can be moved, and are subject to gravity) and the static environment. Physics-objects are visually distinguished from the environment by their small size and increased polygon count, making them pop out from the gameworld, whose textures consist only of large flat shapes without contour or bump-mapping (a technique used to simulate 3D surfaces upon a 2D texture). While physics-objects are visually distinguishable, with textures matching the object which they represent (pizza appears as pizza, firearms appear like firearms), the textures of the environment are deployed in an ad-hoc soup of bright contrasts, smiling faces, abstract patterns and grotesque flesh.

Despite an abundance of consumer spaces in the game, no shops within it contain purchasable physics-objects. The unseen consumer goods, supposedly sold in these shopping spaces, appear simply as low-resolution textures embedded into the non-interactable environmental surface of the world. One store’s walls are textured in blocky images of Funko Pops, small plastic collectable toys of commodified pop culture. Another store holds textured squares of fabrics, or repeating smiling faces. Another store is devoid of any images of objects whatsoever but is plastered with black on red strings of text spelling “HAPPINESS” in wonton and nonsensical directions.

The visual distinction between usable objects and nondescript environment is not unique to Cruelty Squad. Within game development, it is a common strategy to save processing resources and better guide players towards useful objects. For example, Capcom’s 1996 horror game Resident Evil used prerendered flat images for its environmental visuals, with real-time rendered 3D characters and objects strategically placed upon these backgrounds to give an illusion of depth. What sets Cruelty Squad’s distinction of object and environment apart is the self-referentiality of its consumerist setting, creating a visual distinction between where objects should be but are not, and what objects remain perceptible to players’ desires. Thus, Cruelty Squad’s world positions the player within an absence of posited objects, an environment of variating intensities deterritorialized from axioms of exchange and reterritorialized through the flow-state of the gameplay and the player’s desires.

If the capitalist production of space is one which redirects flows of desires towards commodities alien to our interests, then Cruelty Squad’s image of consumer space is a rejection of this. From the perspective of Cruelty Squad’s protagonist, objects only exist where they are tied directly to base desires. For the player, the only perceptible objects are those which have a functional use. By depicting the shopping center’s commodities as environmental textures, the player is habituated to visually scan for objects which are useful toward accomplishing the game’s objectives. In the process, non-functional consumer commodities of the shopping center are blurred into the environment and become imperceptible -- part of the indistinct continuity of mall-space.

The Limits of Desire

Among the consumer objects which remain perceptible to Cruelty Squad’s protagonist, the player’s arsenal of weapons brings attention to how capitalism fosters desires for violence. Kallio positions the military-industrial complex, and its consumer arms counterpart, as systems built not solely on the strengthening of national interests, but on flows of desire within a libidinal economy. As he stated in an interview, “as for military or state violence, I feel like that’s the purest crystallization of a type of legalized murderlust. It’s so completely farcical in the way the stated purposes (defense, security, etc.) differ from the actual outcomes. It’s a libidinal death cult with a serious bureaucratic veneer” (Good and Kallio, 2021). Under the desire-producing machines of capitalist marketing, the expression of power through weapons becomes just another desire accessible through axioms of exchange, and there is no penalty for using the game’s arsenal against non-targets. As an analogue to the player, Cruelty Squad’s opening cutscene positions the image of mass shooters as a natural phenomenon of capitalism’s cultivated desires, what Deleuze and Guattari phrase as the “pervert… who takes the artifice [of capitalism’s codes] seriously and plays the game to the hilt” (1988, p. 35). One of the ironies presented in Cruelty Squad’s violence is the implicit question of what differentiates the player from the other mass shooters running rampant in its world.

The resolution of this question, however, is Deleuze and Guattari’s argument that the schizophrenic is one who is always at the limits of capitalism. They claim that capitalism depends on the absurd production of desires ad-infinitum, which would destroy capitalism itself if not for the guiding structures of exchange. They argue, “desire is revolutionary in its essence… and no society can tolerate a position of real desire without its structures of exploitation, servitude, and hierarchy being compromised” (1988, p. 116). At its most extreme, the vast arsenal of nuclear and conventional weapons produced for the libidinal desires of the defense industry would resolutely end capitalism if ever released. The desires for consumption that are cultivated in shopping centers and their advertisements encourage interactions with the world which would, in turn, destroy these spaces -- along with their owners’ potential for profits -- if only consumers bypassed the axioms of currency and exchange that filter desire through acceptable pathways.

Deleuze and Guattari argue that for capitalist systems “it is therefore of vital importance for a society to repress desire, and even to find something more effective than repression, so that repression, hierarchy, exploitation, and servitude are themselves desired” (1988, p. 116). In Cruelty Squad, Kallio positions the act of consumerism as a repression-desiring structure, where the advertising and branding of retailers are replaced with their true social messages (à la They Live), advertisements reading simply: “PUNISHMENT.” Through a perception which divides desire from the desire-producing machinery of society, the heroic schizo, “has crossed over the limit, the schiz, which maintained production of desire always at the margins of social production, tangential and always repelled… a desire lacking nothing, a flux that overcomes barriers and codes, a name that no longer designates any ego whatever” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1988, p. 131).

Through Cruelty Squad’s eclectic design, and abrasive idiosyncrasies, Kallio visualizes desires largely separated from the machines which produce them, revealing the absurd dangling tumors on the body without organs which reterritorialize spaces into centers where desire is ever-rerouted from their true fulfilment. The large open rotunda of the shopping center seeks to continually bounce attractions cyclically from one store to the next, but through the body of the schizo hero, this space is severed from this cycle as the player transgresses its barriers and bodies.

The Capitalist Neurotic

The mass shooter, in contrast to the player, is a schizo who has not passed the schiz-limit, whose articulations of libidinal desire are filtered through the power fantasies and profit of the arms industry. Deleuze and Guattari argue that, through the endless expansion of uncoded desires available on the market, capitalism has turned all of society into schizophrenics -- but, through the axioms of exchange, we schizos are transformed into “neurotics.” For Bataille, these neurotics are analogous to those who have lost all intimate contact with the world, in the mistaken transcendence into the accumulation of distinct, intelligible things (1988b; 1989). The neurotic is the schizophrenic who, in following the desires laid out to them by advertising, comes to desire their own repression, as well as the modes of exchange through which this repression-desire is manifested. Through this desiring for exchange beyond substance, desire “ceases to be tied to enjoyment or to… excess consumption,” rather, exchange “makes luxury itself into a means of investment, and reduces all the decoded flows to production, in a ‘production for production’s sake’” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1988, p. 224). Quoting Marx, Deleuze and Guattari observe that, unlike food, tools, or even specie, which each carry a nearly one-to-one relationship with desire and satisfaction, “capital… value… suddenly presents itself as an independent [posited or stratified] substance… instead of simply representing the relations of commodities, it enters now, so to say, into relations with itself” (1988, p. 227).

Beyond the mass shooter, whom Cruelty Squad only makes passing reference to, lie the financial barons of Silicon Valley, defense industry stooges and the vampiric consulting class who make up the majority of Kallio’s critique. The gameworld is populated and shaped entirely by those profiting from cruelty, and those complicit in their own subjugation by the former. Cruelty Squad’s levels are each modeled on the geographies of the tech industry, such as a cruise ship owned by libertarian cryptocurrency enthusiasts, a gentrified nightclub filled with tech executives and a privatized space travel startup. Players are able to interact with characters in the gameworld to receive lines of dialogue, with characters often identifying the player as a fellow or subservient employee. Character dialogue is inspired by the absurd Twitter posts of Silicon Valley billionaires, the village perverts for whom all desire has been rerouted into what can be exchanged through capital accumulation. Party-going executives will say to the player, “I need to come here and really let go so I can work on my creative investment portfolio. I have an artistic take on finance.” Figures regularly tout banal material successes as signs of physical power: “I could snap you like a twig. I have a home gym.”

Within this discourse, Kallio parodies the biopolitics of the tech industry, Silicon Valley’s increasing engagement with human biology and neuropsychology to provide market solutions to capitalism’s increasing hostility towards life. The game includes references to meditation apps, designer drugs, and increasingly anatomically analogous sex toys, heightened in game as artificially produced “bioslaves.” Bataille’s critique of religion had rested on what he accused to be religion’s futile quest to bind ineffable experience within discourse and dramatization, alienating the immediacy of open experience, untranslatable into reasoned thought, and in-turn transforming humans and experiences both into objects. Cruelty Squad turns this critique towards capitalism, highlighting Silicon Valley’s dalliance with limit-experiences of drugs, space tourism and Titanic voyages., In doing so, it reveals the absurdity that these experiences are constantly folded back onto the axioms of capitalism -- where real-world firms offer programs of “Psychedelic Assisted Executive Coaching for Business Leaders” (Entrepreneurs Awakening, cited in Tvorun-Dunn, 2022) or where biology is something to be optimized or “biohacked” for labor performance, or where art production is reduced to a financialized device of cryptocurrency investment. In representing capitalists’ constant encounters with the limits of social-production, Kallio reveals the neuroticism of society’s most powerful men. Their desires forever perverted into the axioms of capital generation such that all luxury, enjoyment and human experience are repurposed into further capitalist production. The game highlights these figures as the pathetic class for whom all our surveillance, exploitation and exclusion serve.

Deleuze and Guattari’s perverts are those whose obsession with the codes of capitalism produced “territorialities infinitely more artificial than the ones that society offers us, totally artificial new families, secret lunar societies” (1988, p. 35). The characters of Cruelty Squad are figures for whom financial success is a sign of cosmological insight. A CEO parodying Theranos’ founder Elizabeth Holmes declares “Business isn't just numbers on a screen. It's blood and guts. It's primal violence,” and asserts that all her decisions “are based on the heat signature of the sun. The algorithm is proprietary.” A device in the game titled The Eyes of Corporate Insight promises to allow users to “melt into the power of the markets.” An HR executive states, “Human resources... Simple material to be formed as I please, into my own image. That's how it goes around here. My dream, a large ball of human bodies rolling across vast plains, flattening everything it comes across.” In such instances Kallio parodies the eschatological rhetoric of Silicon Valley (see Geiger, 2020), where buggy product releases are marketed and discussed as revolutionary social changes, an evolutionary step above our biology -- where entrepreneurs like MirrorAI founder Serge Faguet can claim that their goal is “to help make us immortal posthuman gods that cast off the limits of our biology, and spread across the Universe. To have limitless abundance” (cited in Tvorun-Dunn, 2022). In Silicon Valley’s eschatology, the coded flows of established social life become continually deterritorialized, “disrupted” through interventions of technological development and a schizophrenic remapping of experience onto higher cosmologies of secular-spirituality. And yet, such disruption is ever-destined to be recoded and reterritorialized onto axioms of capitalism, such that the market itself becomes coded onto metaphysics.

The Neurotic Player

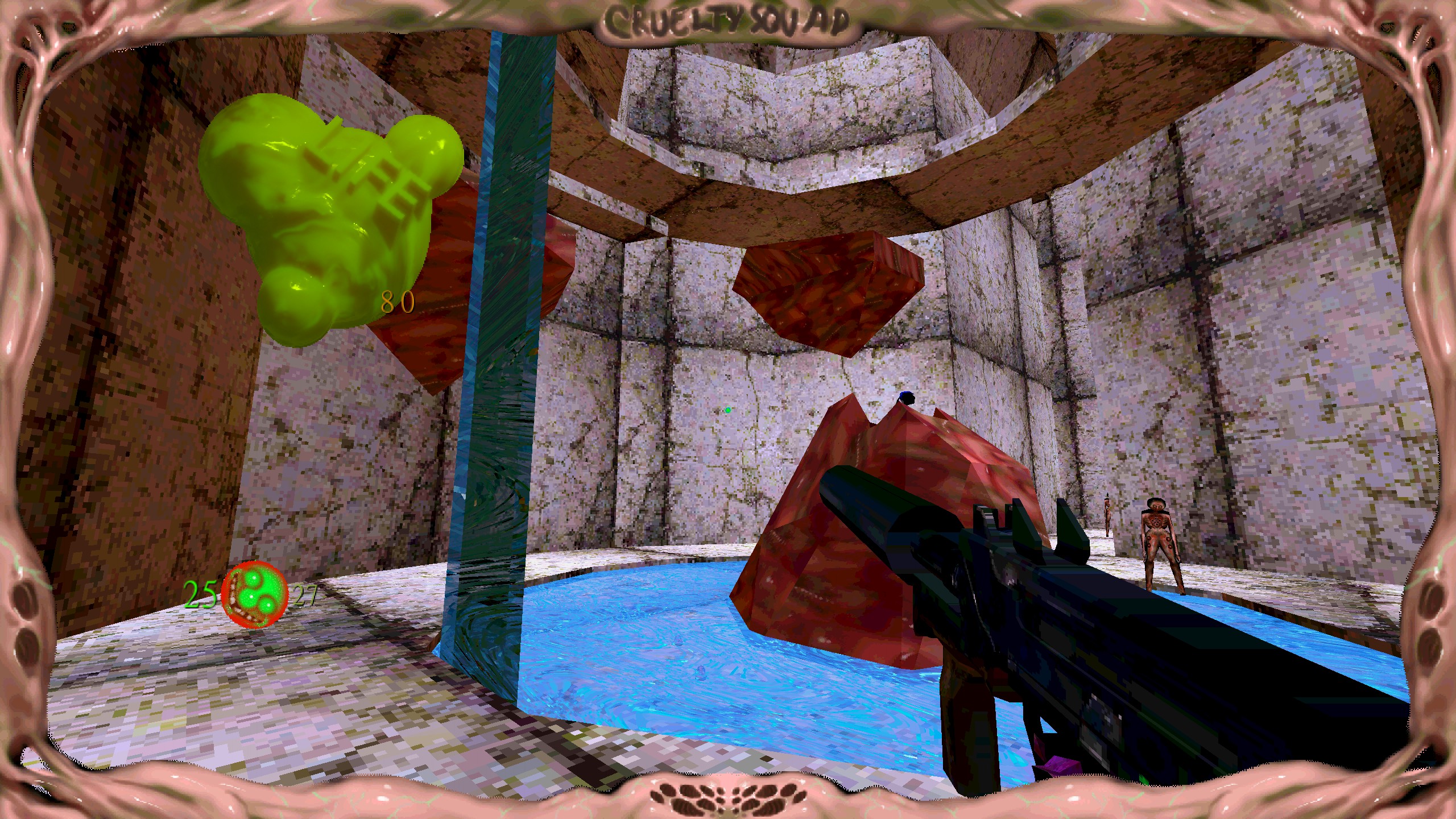

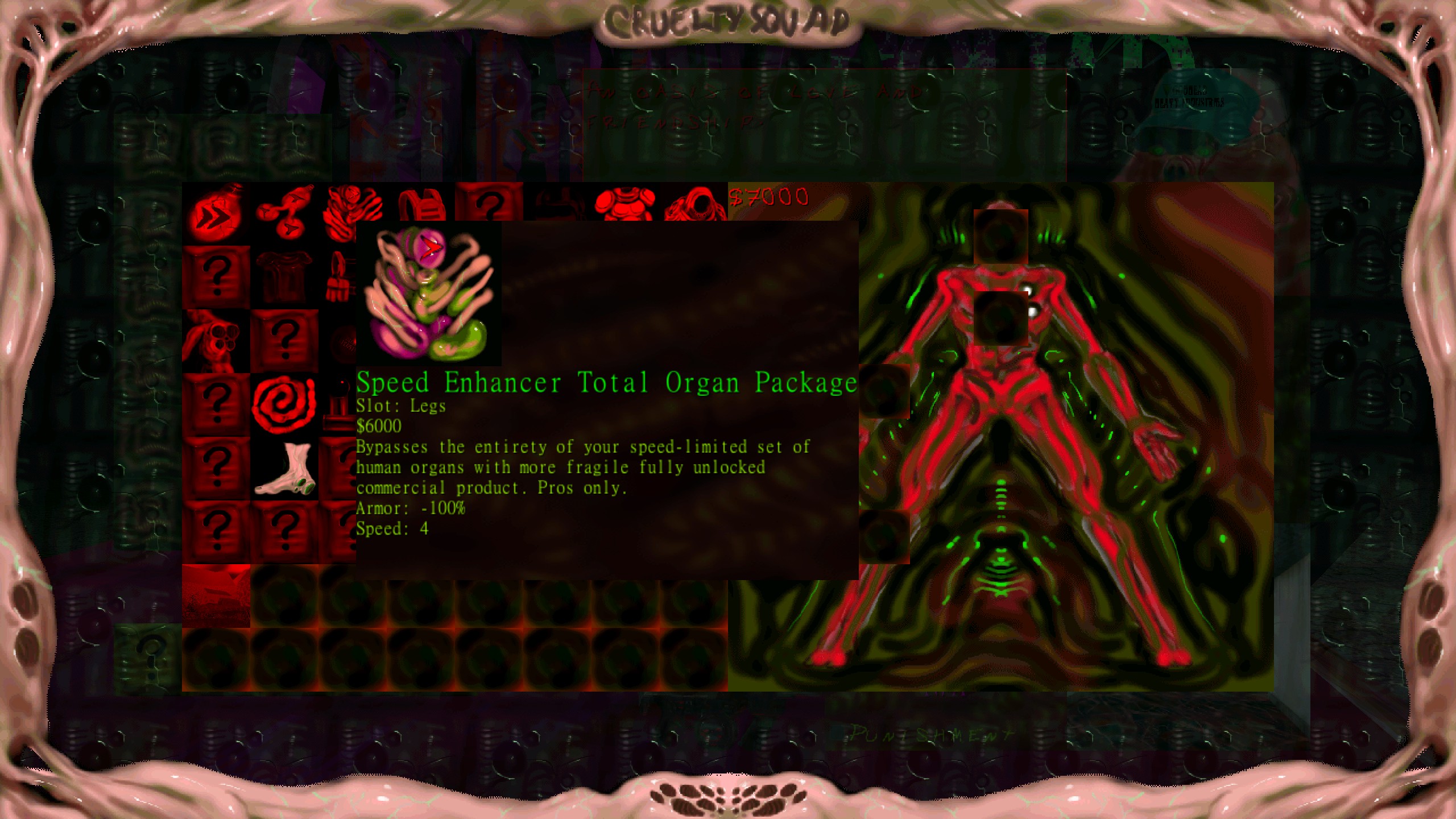

Figure 3: Fill your body with organs at the in-game store. Click image to enlarge.

Through game design, Cruelty Squad’s protagonist is driven by desires -- guided by mechanics to complete objectives, maintain health and expend power -- and in following these desires he is dependent on positing and utilizing tools generated within social production. However, in his scrambled vision, these desires are expressed through base material in an indistinct continuous reality, free to utilize without the redirected channels of social-spacial production, which the neurotic is trapped by. It is the mode of perception of Bataille’s “nascent” or “archaic” humanity, in-between the fully uncoded flows of reality and the totalized hyperreality of socially constructed perception; where only matter which can be mechanically utilized by the player may be posited. The protagonist rests uneasily at the limits of both humanity and capitalism, biological matter overflowing from their pores, just as their corporate violence threatens to pour back into the systems which produced them.

As made visible by the ever-present screen border, there exists a disconnect between the player existing in the real, neurotic world, and the liberatory schizophrenic gaze of the character. While the character is largely free of consumption in 3D space, with the only items to purchase within levels being vending machine dispensers of consumable food, the extradiegetic UI of the main menu offers the player a variety of items to purchase, and even a stock market to day-trade on. Placed on the two-dimensional space of the screen and relegated to the game’s menus outside of active gameplay, these screens of consumption are positioned specifically to the player without necessarily implicating the player-character in their engagement.

As the plot progresses, the player-character turns their violence against financial institutions and abstract representations of capitalism itself, though the game does not end at this point. In the default ending, the player-character defeats the Gnostic archon “Abraxis,” who in Gnostic scripture prevents humanity from seeing the true nature of reality, and returns to a Bataillian state of non-knowledge, with a message announcing that “The world appears as a large flat plane of opportunity. The sky is boundless and blue,” but that in lacking knowledge, the player is trapped in a state of ever-present past, as “the sun smiles at you with eternal malice.” The reticence toward the character’s worldliness displayed here is a common tension within Bataille’s works, as despite his desired states of non-knowledge, he shares a constant awareness that “if man surrendered unreservedly to immanence, he would fall short of humanity; he would achieve it only to lose it and eventually life would return to the unconscious intimacy of animals” (1989b, p. 53).

In order to play beyond this ending and access hidden “post-game” content, the player must scour levels for fine details, finding hints and secret entrances to new maps. Using the tools for advanced traversal acquired throughout the game, they may come to see locations from afar with the boundaries of the level design visible such that the entire environment becomes posited as an object. The final hidden level is unlocked through purchase in the extradiegetic in-game store which requires the player to have amassed one million in capital. Earning this magnitude of in-game currency nearly demands that players become intimately familiar with the 2D UI of the stock market, whose “aesthetics of the screen turn the market into a knowledge-based object” (Zwick and Dholakia, 2006, p. 52). Success in one secret level encourages the player “SET GOALS. HAVE A TEN YEAR PLAN. INVEST. WAKE UP EARLY. CEO MINDSET.” The player, now following the path of the executives that they had previously been targeting, attains a fundamentally different relationship with capitalist space, money and consumption -- no longer making measly specie functional in attaining desires, but a diversified portfolio of assets. As stated in Anti-Oedipus:

It is not the same money that goes into the pocket of the wage earner and is entered on the balance sheet of a commercial enterprise. In the one case, there are impotent money signs of exchange value, a flow of means of payment relative to consumer goods and use values, and a one-to-one relation between money and an imposed range of products… in the other case, signs of the power of capital, flows of financing, a system of differential quotients of production that bear witness to a prospective force or to a long-term evaluation, not realizable hic et nunc, and functioning as an axiomatic of abstract quantities. (Deleuze & Guattari, 1983, p. 228)

Matter, which the player had an immanent relation to, has by this conclusion become abstracted and transformed into financialized value -- immaterialized into “fictitious capital” (Marx, 1995).

In the final ending of the game, unlockable only after finding all other hidden objectives, the player-character has transcended from an immanence of base materiality to a neurotic ascesis of finance. Unlike the schizophrenic gaze devoid of objects produced by play through the base game, post-game play produces entire spaces as objects to be manipulated for capital accumulation. What had been deterritorialized becomes recoded onto accumulation for accumulation’s sake, whether for capital or hidden objects and levels, the search for further content in the game becomes a coveting of matter. As Bataille argues, fear of committing to the immanence of non-knowledge leads to the rejection of the world: “instead of embracing this unleashing of oneself, a being stops in himself a torrent which gives him over to life, and devotes himself, in hope of avoiding ruin… to the possession of things… What dies is the possibility for celebration, for free communication among beings, the Golden Age” (1988b, p. 129). Marx offers a similar sentiment: “the less you are, the less you express your life, the more you have, the greater is your alienated life and the greater is the saving of your alienated being” (1959, p. 51). The accumulation of resources, which to Bataille must be ever expended in accordance with base desire, becomes likened to a death drive: a repression sold by the structures of consumerism to lose ourselves through the possession of objects and capital.

Cruelty Squad’s ending message, the text for which can be found in the endnotes below [1], articulates this narrative trajectory. The text describes a movement from immanent communion with the world toward a neurotic transcendence into wealth and accumulation, ultimately manifesting in the death drive of military, industry and hyperconsumption. The first of four passages presents the player beginning within a childhood immanence, a “drift towards nothing.” Yet, in time the player has transitioned into an ascesis of financialized abstract wealth, made a “high net worth individual.” Where “fleshy” others are doomed by their non-knowledge (described as a “fog of Life”), the player’s “pristine idiocy” as a tech-investing executive “reveals a safe path,” through which the mess of life and biology can be controlled and avoided. In the third passage this avoidance of being reaches its conclusion, the full immaterialization of matter as the player-character “terminate[s] the worldlife.”

Through Cruelty Squad, Kallio presents accumulation as folly, that as claimed by Bataille’s Accursed Share, wealth must be expended rather than hoarded or else one risks a total rejection of living. Through a critique of the tech industry, Kallio relates the redistribution of resources to the wealthy under financialization as intimately related to tech executives’ obsessions with the immaterialization of society. Tech industry projects such as the rerouting of social experiences through digital apps, neural upload computing, the eugenic optimization of “biohacking,” or of the production of virtual spaces of consumption are presented in Cruelty Squad as revealing of a fear of human experience -- one which is destroying the lives of everyone else in the world in the process, whether through environmental destruction, expansion of the military industrial complex, or the financialization of every basic necessity.

Neoliberalism is a system dependent on endless expansion of the market. Ever more desires, or middle-managing systems necessary to contain and redirect these desires, must be brought to market, while natural resources are deterritorialized and exploited into commodities. It is a system that carefully manufactures corporate spaces and reifies them as primordial, metaphysical, higher powers -- a socially constructed presupposition that tells us that this is the only reality which exists, the only structures which have ever truly existed. The growth of the market furnishes a perpetual reduction of reality, as its excess pours filth back into those parts of the globe which it has already finished syphoning materials and labor from. Cruelty Squad’s schizophrenic aesthetic of flesh and bile reveals the biopolitics beneath consumerism, the production of systems of control which contain society’s messy human matter and seek a transcendence into things.

Videogames, through the production of experience, carry the potential to both enforce, and reveal the limits of our bodies without organs, offering capacities typically repressed by capitalist society’s desire-producing machinery and revealing structures within space invisible to our hyperreal perception. In decoding the spaces of social repression which we regularly encounter, Cruelty Squad defamiliarizes us from consumerism, reminding players of the material relations between nature and object, and between laborer and capitalist. It is an articulation of the death drive which has taken hold of global economics in its willingness to accommodate unlimited resources to a few technocrats.

Endnotes

[1] “A point in the horizon, a melting scene from your childhood. Your mortality is showing. A frantic drift towards nothing, biology doomed to an infinite recursive loop. Teeth with teeth with teeth. Take a bite. Serene scent of a coastal town, warmth of the sun. Bitter tears. Lust for power. This is where you abandoned your dreams. You are a high net worth individual, an expanding vortex of pathetic trauma. Finally a beautiful fucking nerve ape. A pure soul is born, its neurotransactions stutter into being. 30583750937509353 operations per nanosecond. Beauty eludes your porous mind.

The value of Life is negative. The balance of being is rotated by 38 degrees. The surface is full of cracks, a turgid light shines through. Fleshy primordial bodies sluggishly roll down the slope. Only you slide upwards, with a celestial step. You become beautified, a saintly figure. Your pristine idiocy reveals a safe path through the impenetrable fog of Life. Your dull sword cuts through the weak tendons and membranes of the garden of corruption. Sit on the throne of contentment and ferment. Inspect the eternal blue skies of your kingdom. You come to a realization. You pick up an onion and begin peeling.

Onion layer one. Onion layer two. Onion layer three. Onion layer n^n. Aeons have passed and the onion is fully peeled. Nothing remains. It's perfect. You get lost in the point that remains where the onion used to be. Synaptic cascade, neurological catastrophe. The point becomes infinitely dense, the universe condenses into a unicellular being. It screams sin. It craves happiness. It's done with this world. It tries to commit suicide but fails. Sad pathetic mess. You feel pity and disgust but in a way only a being of pure grace can. In your violent mercy you terminate the worldlife.

‘The living organism, in a situation determined by the play of energy on the surface of the globe, ordinarily receives more energy than is necessary for maintaining life; the excess energy (wealth) can be used for the growth of a system (e.g., an organism); if the system can no longer grow, or if the excess cannot be completely absorbed in its growth, it must necessarily be lost without profit; it must be spent, willingly or not, gloriously or catastrophically.’ - Georges Bataille” (Consumer Softproducts, 2021).

References

Visual Concepts. (2005-present). NBA2K. Digital game franchise, published by 2K.

Bataille, G (1985). Base materialism and Gnosticism. In A. Stoekl Visions of Excess: Selected Writings. University of Minnesota Press.

Bataille, G. (1988a). The Accursed Share: An Essay on General Economy. Vol. 1. Zone Books.

Bataille, G. (1988b). Inner Experience. State University of New York Press.

Bataille, G. (1989). Theory of Religion. Zone Books.

Capcom. (1996). Resident Evil [Sony PlayStation]. Digital game directed by Shinji Mikami, published by Capcom.

Capcom. (2006-2017). Dead Rising [Various platforms]. Digital game franchise, published by Capcom.

Cremin, C. (2016). Exploring Videogames with Deleuze and Guattari: Towards an Affective Theory of Form. Routledge.

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1983). Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press.

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1987). A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press.

Denegri-Knott, J. and Molesworth, M. (2010). Concepts and practices of digital virtual consumption. Consumer Markets & Culture, 13(10). 10.1080/10253860903562130

Fellini, F. (1960) La Dolce Vita. Cineriz.

Friedberg, A. (1993). Window Shopping: Cinema and the Postmodern. University of California Press.

Friedberg, A. (2006). The Virtual Window: From Alberti to Microsoft. MIT Press.

Geiger, S. (2020). Silicon Valley, disruption, and the end of uncertainty. Journal of Cultural Economy, 13(2). 10.1080/17530350.2019.1684337

Good, C. and Kallio, V. (2021) Artist of the week: Ville Kallio. Lvl3. https://lvl3official.com/ville-kallio/

Gottdiener, M. (1995). Postmodern Semiotics: Material Culture and the Forms of Postmodern Life. Blackwell.

Interplay Entertainment and Bethesda Softworks. (1997-present). Fallout [Various platforms]. Digital game franchise, published by Bethesda.

IO Interactive. (2000-2022). Hitman [Various platforms]. Digital game franchise, published by IO Interactive, Eidos Interactive, Square Enix and Warner Bros. Games.

Ion Storm. (2000). Dues Ex [Various platforms]. Digital game directed by Warren Spector, published by Eidos Interactive.

Irrational Games and Looking Glass Studios. (1999). System Shock 2 [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game franchise directed by Ken Levine, published by Electronic Arts.

Consumer Softproducts. (2021). Cruelty Squad [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Ville Kallio, published by Consumer Softproducts.

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The Production of Space. Blackwell Publishing.

Lehdonvirta, L. (2012). A history of the digitization of consumer culture. In M. Molesworth and J. Denegri-Knott Digital Virtual Consumption. Taylor & Francis.

Marx, K. (1959). Economic & Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. Progress Publishers.

Marx, K. (1995). Capital Volume III: The Process of Capitalist Production as a Whole. International Publishers.

Momi, D. et al. (2018). Acute and long-lasting cortical thickness changes following intensive first-person action videogame practice. Behavioral Brain Research, 353. 10.1016/j.bbr.2018.06.013

Overkill Software and Starbreeze Studios. (2011-2023). Payday. Digital game franchise, produced by Sony Online Entertainment, 505 Games, and Deep Silver.

Rockstar North. (2013). Grand Theft Auto V. Digital game directed by Leslie Benzies, produced by Rockstar Games.

Ryu Ga Gotoku Studio. (2005-present). Yakuza [Ryu ga Gotoku] [Various platforms]. Digital game franchise, published by Sega.

Spencer, D. (2016). The Architecture of Neoliberalism: How Contemporary Architecture Became an Instrument of Control and Compliance. Bloomsbury.

Tvorun-Dunn, M. (2022) Acid liberalism: Silicon Valley’s enlightened technocrats, and the legalization of psychedelics. International Journal of Drug Policy, 110. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103890

Woods, A. (2011). The Sublime Object of Psychiatry: Schizophrenia in Clinical and Cultural Theory. Oxford University Press.

Yee, N. (2006). The labor of fun: how video games blur the boundaries of work and play. Games and Culture, 1(1). 10.1177/1555412005281819

Zwick, D. and Dholakia, N. (2006). Bringing the market to life: screen aesthetics and the epistemic consumption object. Marketing Theory, 6(1). 10.1177/1470593106061262