The Achievement Machine: Understanding Xbox 360 Achievements in Gaming Practices

by Mikael JakobssonAbstract

Xbox Live achievements and gamerscores have become an integral part of Xbox 360 gaming. Based on the framework provided by Microsoft, the community has developed intriguing gaming practices where the individual games become pieces of a larger whole. This paper, based on a two year community study, explores how players have reacted and adapted to the system. To get at this shift in console gaming, the achievement system is seen as a massively multiplayer online game (MMO) where separate achievements are the functional equivalent of quests. By conceptualizing the achievement system as an MMO, the paper questions the dichotomy between PC/MMO and console gaming. The paper also goes into detailed descriptions of gaming habits and strategies that have emerged as gamers appropriate the achievement system, in particular looking at three player types: achievement casuals, hunters and completists. My conclusions are that the Xbox Live achievement system only partially functions as a reward system. More importantly, in terms of impact on player practices, it is an invisible MMO that all Xbox Live members participate in, whether they like it or not. On one hand, the different strategies and ways of conceptualizing the system shows how players have appropriated the technology and rules provided by Microsoft, and socially constructed systems that fit their play styles. On the other hand, many players are deeply conflicted over these gaming habits and feel trapped in a deterministic system that dictates ways of playing the games that they do not enjoy. Both sides can ultimately be connected to distinguishable characteristics of gamers. As a group, they are known to take pleasure in fighting, circumventing and subverting rigid rule systems, but also to be ready to take on completely arbitrary challenges without questioning their validity.

Keywords: achievements, Xbox 360, gamerscore, reward systems, gamer culture, massively multiplayer online games, podcasts

Introduction

Systems where players collect virtual rewards that in some sense are separated from the rest of the game have seen a dramatic rise in popularity during the last few years. These systems that connect different games that share for instance the same technological platform or publisher are often called achievements. An important reason for the proliferation of these systems is the success of the achievements for Microsoft's Xbox 360. Collecting achievements has become an integral part of Xbox 360 gaming. The system has divided gamers in camps for and against achievements, and changed the way many people play games.

Based on an ethnographic study of different participants in the Xbox 360 community of practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991) such as game writers, critics and gamers; this paper attempts to provide a rich picture of the phenomenon. I will show how gamers appropriate achievements into their gaming activities, and explore the different attitudes that players have developed towards achievements. By conceptualizing the achievement system as a massively multiplayer online game (MMO) played in parallel to all games on the Xbox 360 that include achievements, I provide a perspective that uncover new aspects of the phenomenon. Conceiving of the achievement system as a MMO also creates a link between studies of MMO games and console games, and shows that these gaming practices have interesting similarities.

Methodology

This paper is based on a two year study of Xbox 360 achievements stakeholders such as gamers, the enthusiast press and Microsoft employees. The empirical material is collected from blogs, news sites, forums, video clips, podcasts, reviews from enthusiast and mainstream press, face-to-face and online interviews and participatory observation during Xbox Live gaming sessions and at gamer meet-ups.

When I first started participating in a Swedish gaming community that had emerged around a gaming podcast, my approach was exploratory in nature. This type of community formation was different to those I have previously studied. I have studies PC gamers online (Jakobsson and Taylor, 2003; Jakobsson, 2006) and console gamers that meet in person to play together (Jakobsson, 2007). These participants, however, mainly played console games together online. This is new since earlier generations of console hardware only had limited support for online gaming. I had also for some time been interested in the so called enthusiast gaming press and how they negotiate and mitigate ideas of what games are and should be. In both of these empirical sources, Xbox 360 achievements emerged as a resonant theme. Once I had decided to focus on the interplay between the Xbox 360 achievement system as a technological system designed by Microsoft, and as a s cultural system socially constructed by the Xbox 360 community of practice, I changed my method of collecting empirical material to focus on achievements, gamerscore, gamertag and other related keywords.

I have lived with the people I have studied on a daily basis for over two years, but since this is a highly distributed community, most of the interaction and collection of material has been done through the net. Much of the time has been spent on listening to podcasts. I have found the numerous podcasts dealing with video games in general or Xbox games in particular [1] especially interesting since they are used as spaces for reflection and discussion. Achievements have been a recurring topic for the duration of the study and these discussions often overlap with the questions I would have asked if I had been interviewing the participants. The problem with linear, uncategorized media such as podcasts is that there is an immense amount of material to go through to get to the interesting bits. But on the other hand, listening to podcasts for up to eight hours a day provides a strong sense of immersion in the studied culture. This media format, characterized by its very loosely structured recorded conversations, opens up for a new way for ethnographers to, if not participate, at least listen in on the participants in an interesting way.

It is, however, important to recognize that at least part of the reason for recording these podcasts is to entertain the listeners, which sometimes leads the participants to be more argumentative and colorful than their actual views warrant. When I compare different sources to each other, a pattern emerges where the tone differs between, face-to-face interviews, casual comments during gaming sessions, forum posts and podcasts. All empirical materials are colored by their form of mediation. Podcasts are a challenging but interesting empirical source that should be explored further by virtual ethnographers.

The Xbox Live Achievement System

Most readers are probably somewhat familiar with Xbox Live achievements. This section will provide the details of the system together with the terminology used by Microsoft.

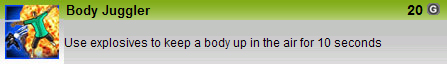

Figure 1. Description of the Body Juggler achievement from Crackdown (Realtime Worlds, 2007) including title, task, icon and gamerscore value. (Source: Xbox 360 Achievements, www.xbox360achievements.org)

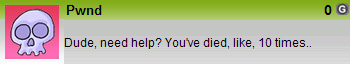

Every retail game [2] for the Xbox 360 must have 1000 gamerscore points. These are divided between up to fifty achievements (Figure 1). There are no guidelines for how many points each achievement should give. Some, usually "booby prize" achievements (Figure 2), are not worth any gamerscore points. Xbox Live Arcade games [3] have 200 points usually split between twelve achievements. The developer may save some of the gamerscore points for downloadable content released after the release of the main game, but that content must then be made available free of charge. Downloadable content may give extra gamerscore points and achievements, usually 250 points for retail games and 50 points for Xbox Live Arcade games (Bland, 2009; Greenberg, 2007). The rules were less well defined when the Xbox 360 was released which led to some titles diverging from the standard, for instance having less than 1000 gamerscore points. Microsoft has also, on occasion, allowed for some exceptions, such as Fallout 3 (Bethesda, 2008) where it is possible to get a total of 1750 points by getting all the achievements in all the expansions ("Achievements," 2010). While the achievement system was started with the release of the Xbox 360 and is closely linked to this platform, some PC and Windows 7 Phone games also offer achievements in the same system (McElroy, 2010). Apart from these quantitative guidelines, the developers are free to design the achievements for their games as they see fit.

Figure 2. Zero point achievement from The Simpsons Game (EA Games, 2007). (Source: Xbox 360 Achievements, www.xbox360achievements.org)

Anyone can look up the achievement information of other players on Xbox.com (Figure 3) as long as they know the player’s gamertag (the person’s username on Xbox Live), or directly on the Xbox 360 if they have the person in their friends list or in the recent players list. It is also possible to compare achievements with people on a friend's friend list, as well as friends of recent players. Players can turn off other people's access to their friends, and restrict the access to their gaming history to friends only or completely block it.

Figure 3. Gamer information on the web. (Source: Xbox.com)

The information given about a gamer's achievements includes detailed information about when each separate achievement was unlocked (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Achievement history for Puzzle Quest . (Infinite Interactive, 2007) (Source: Xbox.com)

Players actively promote the awareness of their identity and gaming history by customizing gamercards for use on websites, blogs, forums and in automated signatures (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Gamercard terminology ("Description of Xbox 360 gamer profiles," 2010). (Source: Illustration based on image from Mygamercard.net)

When a player receives an achievement, a notification pops up on the screen informing the player of the gamerscore value and name of the unlocked achievement. There is also a sound cue. The notification can be disabled together with all other notifications, but the player still receives the achievement.

The History and Impact of Achievements

Since the introduction of achievements on the Xbox 360, the concept has spread to a number of different platforms such as Steam, Playstation 3 [4] and Battle.net. Achievements are, however, nothing new. The Atari 2600 had a similar system in place almost 30 years ago. For some of the Activision games, the manual listed challenges, for instance to score ten thousand points. If the player managed to do this, took a picture of the TV screen, and sent the photo to Activision, they would in return send a decorative patch made of fabric (Figure 6) to the player. There were also patches for some of the Atari 5200, Intellivision and Colecovision games but the system was eventually phased out ("Activision Patch Gallery," n.d.). There are many similarities between the Activision patches and Xbox Live achievements, but there are also some significant differences. Atari gamers could only display their accomplishments locally and the analogue nature of that system made it less pervasive.

Figure 6. Activision patch awarded for scoring 10.000 points in Chopper Command (Activision, 1982).

A closer predecessor to the achievement system is the MSN Games [5] website. It was acquired by Microsoft in 1996. It offers both free and paid single player and multiplayer games. It has a number of community enhancing features including badges that players can acquire in some of the games (Wikipedia, 2010). The MSN Games studio was involved in developing Xbox Live, so it is reasonable to believe that the badge system worked as a template for the Xbox 360 achievements ("Microsoft Online - From The Zone to Xbox Live," 2004).

At least from the outside, it seems that the achievement system initially was not considered a major part of the Xbox 360 platform. Microsoft’s guiding principle when developing the Xbox 360 was to put the player in the centre. In the design documents, aspects like Xbox Live support [6], cooperative play modes in both single- and multiplayer games and content downloads were identified as key issues together with some that turned out to have less impact on the final system such as procedural synthesis, and community participation in content creation [7] (Takahashi, 2006).

When the Xbox 360 was revealed at the Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3) 2005, Robbie Bach, Senior Vice President of the Home and Entertainment Division of Microsoft only mentioned achievements briefly after all the other components that make up the gamer card. The gamerscore was only mentioned as a part of what is displayed on the gamercard and never explained: "We've also a new concept called achievements. Now, these are sort of a record of everything you've accomplished across your library of games. Let's say you haven't figured out that final achievement in PGR 3? [(Bizarre Creations, 2006)] Just ask a friend online" (Bach et al., 2005).

Aaron Greenberg, the group product manager for Xbox 360 and Xbox Live, was surprised to see the reception of achievements within the gaming community: "You never quite know how people are going to react to these sorts of things… But we were very pleasantly surprised when it took off like wildfire" (Hyman, 2007). Greenberg also noted that achievements have had a commercial impact. In an interview with The Hollywood Reporter he said: "We see gamers coming back to us because we give points, other platforms don't" (Hyman, 2007). But not all games available for the Xbox 360 give achievements. The exceptions are Xbox 360 Indie Games and the digital re-releases of original Xbox games. Daemon Hatfield from IGN.com feels that they also should be part of the achievement system:

Daemon Hatfield: There are a couple of them but… They shot themselves in the foot, because I can’t get into anything that doesn’t have achievements.

Jeremy Dunham: Yeah, it’s sort of a mental barrier... You have to think of it as not an Xbox game, just another outlet to play indie games on, like a computer or something else. But I know what you mean. (Game Scoop!, 2009)

It seems that it is not just games with achievements that are favored over games that do not have them. A study by Electronic Entertainment Design and Research (EEDAR) suggests that many and diverse achievements lead to higher review scores and more units sold (EEDAR, 2007). The Xbox 360 achievement system has had a significant impact on the gaming industry, which makes it an interesting socio-technical object of study. There are many possible ways to conceptualize this system. I will now present a perspective for understanding the achievement system that emerged from my study.

The Xbox Live Massively Multiplayer Online Game

Much of the recent debate within the games industry has revolved around achievements as extrinsic rewards, that is, signs of recognition that work as external motivations. (Hecker 2010; Schell, 2010) The alternative would be intrinsic motivation which emerges from interest and enjoyment in the task itself. This perspective on achievements is problematic in several ways. To begin with, there is no consensus within social psychology regarding where to draw the line between intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. There is also disagreement as to whether it even makes any sense to make this distinction. Reiss (2004), for instance, instead advocates a theory of 16 basic desires. One of these is interestingly enough the desire to collect, which Sotamaa (2010) identifies as an important part of achievement hunting. In the division between extrinsic and intrinsic rewards, this would belong to the latter.

Social psychology aside, many game studies scholars have pointed out that achievements in some sense exist outside of the game they belong to. Järvinen describes them as "extraneous goals [that] seldom are tied to the theme/fiction of the game" (2009) and Bogost calls the Xbox 360 achievement system a "loyalty program" (2010).

This has been raised as a potential problem because it is seen as interfering with the intended (or pure) experience of the game (Hecker, 2010). I agree that achievements in some significant ways exist outside of the experience of the game they come bundled with. But if we move the focus from what impact achievements have to playing the game, to what gaming experiences the achievements themselves provide, we will see that they are central to a second game that all Xbox Live members play at the same time as they play the separate retail and downloadable games. This second game has no official name, but I will refer to it as the Xbox Live Massively Multiplayer Online Game (XLMMO).

When we look at achievements as parts of the XLMMO, we see that they are more than just rewards. An achievement actually consists of a task, a task description and a reward, just like a quest in World of Warcraft (Blizzard, 2004) (Figure 7) [8].

Figure 7. Quest description in World of Warcraft. (Source: Blizzard Entertainment)

The gamerscore can be compared to experience points, games become quest lines, and the gamertag is the character name. Another interesting similarity is the scale of these systems. The XLMMO has been played since the release of the Xbox 360 in 2005 and is played by all Xbox Live members [9] which as of January 1, 2009 amounted to 17 million players (Thorsen, 2009). World of Warcraft, by comparison, was released one year earlier in 2004 and had 11.5 million users as of November, 2008 (Cavalli, 2008).

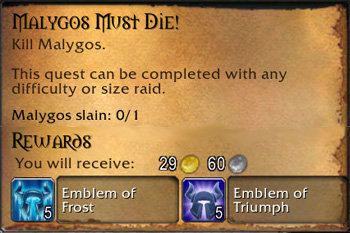

All MMO's seem to have one phenomenon in common: people that grind resources such as in-game currency or experience points and sell these to other players, so called "gold farmers" (cf. Dibbell, 2006). When I started looking for the equivalent for the XLMMO, I had no problems finding sites like Level My 360 (Figure 8). Their tagline was "Powerleveling for your xb360 gamerscore," and they offered gamerscore boosting by their "gaming professionals" for fees of approximately US$100 for a thousand gamerscore points (Cole, 2006).

Figure 8. The now closed point farming website Level My 360. (Source: Levelmy360.com)

Many of the console gamers I have studied exhibit negative attitudes towards PC gamers in general and World of Warcraft players in particular. They frequently say that people who play World of Warcraft have an addiction problem and that they are wasting their lives, not realizing that their own grinding for achievements at times bear a striking resemblance to this type of gameplay . On the other hand, some console gamers display similar attitudes towards both MMO players and achievement hunters using derogatory terms like "achievement whores." Before examining different attitudes towards achievements any further, I will outline some of the properties that the XLMMO shares with other MMOs.

Persistence

The XLMMO has been played for five years, and will likely continue as long as Xbox Live is around. Some achievements are theoretically impossible to get because the servers have shut down, or they were tied to a certain event that never will be repeated. Some achievements are simply quite hard or impossible to attain. For example, while it is perfectly natural to assume that people eventually will move on from particular games when they have been out for a long time, the need to get those achievements never goes away for some players. We therefore see initiatives like the "1,000 People Online Event" organized by the Achieve360points.com website and other similar initiatives. This event was organized so people could get the otherwise unattainable "Online with 1,000 people" achievement from NBA Live 07 (EA Sports, 2006). As the title implies, you do not actually have to play the game to get the achievement. As long as enough people are online and have the game running at the same time, they will all get the achievement. This was originally accomplished without any effort when the game was newly released, however, once players had moved on to other titles it became very hard [10].

"Boosting" - the act of playing games specifically for achievements often requires co-operation between players. It is reminiscent of grouping in MMO's. In a forum posting entitled "A Beginner's Guide to Boosting," a forum member at the Xbox 360 Achievements website lists tips for boosting etiquette that will sound very familiar to any MMO player. The first example corresponds to communicating to other players which quest you are working on: "Announce Yourself - either when entering a new game lobby or when a new player joins, let others know that you are boosting for achievements and chances are a lot of people will offer to help out, allowing you to get the points all the faster" (Osaka Jim, 2008). The second example is a general etiquette rule:

Know When To Stop - unless you know your boosting partners 110% then always assume that they have a job to go to or a family to spend time with. Three hundred more kills may seem like no time at all for yourself but for someone who has to get up early or has an angry spouse waiting for them (the worst punishment known to mankind) it equals a near lifetime of hassle. If someone has to go then show some courtesy and arrange another time to meet up, no one likes a whining little bitch, especially when they’re nagging to help them win fifty ranked matches at three in the morning. (Osaka Jim, 2008)

Boosting can mean everything from playing the game as intended but making sure that as many achievements as possible get unlocked to intentionally subverting the system to get achievements. I participated in a Halo 3 (Bungie, 2007) boosting event of the latter kind where all participants first changed the language preference settings to a particular type of Chinese and then on a given command (over Skype) pushed the "search for game" button. The result (after a number of attempts) was that we all ended up in the same game, despite playing in a mode were the system is supposed to match players randomly. The result was that we could take turns doing things (read out from a list by the organizer) that unlock achievements with the other participants acting as voluntary victims. The activities included taking turns shooting two other players with one shot, something that is very hard to perform in a regular game. Although we were engaging in a very instrumental activity, participants seemed to enjoy the event for the social aspect of it (cf. Jakobsson & Taylor, 2003).

Finally, the gamertag fills a similar function as the character in an MMO. Through this unique identifier, the accumulated experience points and items in an MMO and gamerscore points and achievements in the XLMMO are woven together into a coherent whole, the often rich gaming history of a player. This development of a game identity over time is more meaningful to the player than just the points it consists of, it is also the key to the social (gaming) capital that the player has built within the community (Consalvo, 2007; Jakobsson & Taylor, 2003).

Coveillance

A core property of the achievement system is the possibility to look at other player’s profiles and see detailed information of their achievements, and in return providing everybody else access to detailed information about your gaming activities. Taylor (2006:1) discusses coveillance, the lateral observation between community members, in relation to game modifications in World of Warcraft. She notes how the playful and fun aspects of these systems are intricately intertwined with more troubling issues of observation and control. In my study I have come across countless examples of people engaging in friendly competition using the gamerscore as a kind of high score list. Sometimes the competition is for a limited time and may involve some kind of prize, other times it is an ongoing battle within a group of friends or colleagues. The achievement sites also run gamerscore leagues and tournaments for individuals and teams.

There are also ways other than competition to make use of the shared achievement information. Player often look at their friends lists when they log on to their systems just to gauge what others are up to - and which game titles that are popular at the moment. The achievement list of friends can also be used when game help and information is needed. Greg Sewart, former writer for Electronic Gaming Monthly, put it like this:

[Dead Rising, Capcom 2006] was one of the first games I remember you talking about achievements, and that was one where I was actually comparing my achievements to other people just to get advice on how to do things. You know, I’d look at people’s achievement list, and it was like: "Oh wow, they got this!" And I’d go like. I don’t even, I can’t even begin to guess how to get this achievement. Like the one where you kill the population of the town... So it was kind of, that was one of those great early Xbox 360 community games, where you turned on your system and everyone was playing the same game. And everyone was talking to everyone about it... It seems like the information was flowing more virally, than anything else. (Player One Podcast, 2010)

On the other hand, the way the XLMMO has affected game critics offers some insight into the potential problems connected to coveillance. Game critics are often required to make their gamertags publically available and when readers are unhappy with the review of a game, it is commonly called into question if the reviewer has played enough of the game to be trusted. This is problematic for the reviewers since they often use so called "debug systems" that are special consoles that play unsigned code. Playing a game on a debug unit does not unlock any achievements or give any gamerscore points on Xbox Live. It is therefore common for reviewers to replay games once the final version has been released to get the gamerscore points, partly because they pride themselves on having high gamerscores and partly to avoid doubt from readers as to whether they have actually finished the game.

Anthony Gallegos (reviewer at IGN): If I play a retail game for review I make sure I get all the achievement to show I completed it. Aaron Thomas (former reviewer at Game Spot): I always got excited when I got handed a review copy and I’d look, and I’d go: "This is the green disc. This can play on retail." (Mobcast, 2010)

In the following discussion it becomes clear that they have tried different methods to circumvent the issue including moving profiles to debug machines, bringing profiles on memory cards to preview events and asking Microsoft to transfer gamerscore points. Yet none of these approaches work. The lengths they have gone to are understandable when considering what is at stake. When reviewer Jeff Gerstmann was fired from Gamespot shortly after reviewing Kane and Lynch: Dead Men (Io Interactive, 2007), his colleague addressed the audience of their podcast regarding Gerstmann's achievements for the game:

Ryan Davis: There was also, Jeff addressed this but I think it’s good for us to address it as well, you know people being suspicious because the, you know, the gamertag that this game was played on only had like three achievements unlocked so it looked like he hadn’t played through the game but, you know, no! Not true. You know, as is the case very often, we’re playing these games on pre-release systems, on debug consoles, that aren’t part of the same network, that don’t operate on the same system as retail Xbox 360s and that is where Jeff did the majority of his work on that game, so that’s why that looks that way. (The Hotspot, 2007)

It is not only reviewers' achievements that undergo close scrutiny. Any kind of public person who chooses to reveal their gamertag can expect to have their gaming habits investigated and commented upon. An example is the professional basketball player Gilbert Arena who was featured on the cover of NBA Live 08 (EA Canada, 2007) but mentioned in an interview that he preferred the rivaling series of basketball games from 2K Sports (Sliwinski, 2007). This led to close scrutiny of his Xbox 360 achievement history which showed that he indeed did not play EA's basketball game. People also noticed that he had been cheating in Halo 3 to boost his online ranking which was reported by The Washington Post (Steinberg, 2007). These issues might seem trivial, but being picked as the cover athlete for a game is both lucrative and prestigious, and a controversy like this can significantly reduce the chance of being picked again in the future. Gilbert Arena now has three separate gamertags.

Coveillance is a double edged sword. We like these systems because people can see when we have done something that we are proud of, and it can be interesting to observe the activities of others, but consistently performing at a level we can feel good about easily turns the most fun filled activities into chores. Although we can choose to divulge less information to counteract the negative effects, the absence of data also sends signals to others. A restricted access can for instance be read as an attempt to hide something embarrassing.

All Xbox Live members get gamerscore points and achievements, regardless of whether they themselves acknowledge this or share this information with anyone. Participation in the XLMMO as a user of the Xbox Live service is not a choice. Even if there had been a way of opting out completely, the fact that the system is there means something, also to those that see no value in it. Achievements have become hot discussion topics on boards, blogs, podcasts and when gamers meet face to face. They have changed the discourse within the community of practice. It is understandable if the slogan used on the Swedish Xbox website: "You are what you play" (Microsoft, 2008) was perceived as more ominous than appealing to some of the players.

Open-endedness

Taylor (2006:2) points out regarding Everquest (Sony Online Entertainment, 1999): "the game never ends, so players must be self-directed in how they progress." (p.75). Likewise, the XLMMO does not have an end or any stated goals. It is up to the participants to decide what they want to achieve. This leads to a situation where a MMO can work as many different types of games even to a single player (Jakobsson, 2006; Simon, Boudreau and Silverman, 2009). In the second part of this paper I will attempt to give a rich picture of how gamers make sense of the achievement system.

Three Ways of Approaching Achievements

I have structured this section into three different approaches to the achievement system among Xbox 360 gamers that emerged as themes in the analysis of the empirical material: Casuals, hunters and completists. It is important to note that these three categories are fuzzy and unstable. Players may inhabit traits from several categories at the same time and their attitudes and play styles often change over time. The players' own perception of which category they belong to often is inconsistent with their actual gaming behavior, and as we will see, they are often ambivalent to their play styles, noting that they wish they could act differently or that they do not understand their own behavior.

Achievement Casuals

Many gamers, me included, only relate to achievements in what we could call a casual manner where the achievement system adds value by providing mental scaffolding utilized in the process of shaping the gaming experience. When I play games on the Xbox 360, I usually do not think of achievements until, by chance, one is unlocked. It is not until I have finished a game but want to continue playing it the achievements come into play in a significant way. Developers have always provided different ways of prolonging the gaming experience, like so-called "new game plus" options where the player can start over from the beginning with abilities or items carried over from the first playthrough, but achievements provide a stronger sense of optional unfinishedness. I can convince myself that further engagement with the game is reasonable and worthwhile although I have reached the formal end, because the achievement scaffolding stretches further and provides a direction. Before it became apparent to developers that achievements could provide this function, there were some games, like King Kong (Ubisoft Montpellier, 2005), where all the achievements were unlocked simply by playing through the game once. The coveillance effect also plays a role here. The fact that every effort I make beyond a barebones play through is recorded and visible to others further legitimizes additional efforts. The backside to the optional unfinishedness is that in order to provide scaffoldings that reach far enough to contain extended stays, it becomes hard to completely finish the game. The achievements need to matter enough that we can use them as motivations to continue as long as we enjoy playing a game, but not so much that we feel forced to continue playing when the pleasure is gone. The achievement casuals thus have to move the focus between the regular game and the XLMMO in order to tailor a gaming experience that fits their individual needs.

I have already discussed how achievements can facilitate interaction and communication between gamers, but they can also simply serve as a record of a player's history. A gamer with the alias Shipwreck says, "I’m not comparing my score against other people’s... It’s just a way to track what I’ve played. Like, that’s the best part about the whole achievement system" (CAGcast, 2010). When related to in this manner, the system unobtrusively augments the gaming experience without changing it in any significant way.

Part of the criteria for being an achievement casual is that achievements reside in the background of the gaming experience, only surfacing occasionally. This separates the casuals from the hunters who engage in often fiercely competitive behavior related to achievements. The achievement casuals will, however, at times also compete. This is often done without the opponent knowing that there is a competition happening. The achievement system is constructed in a way that makes it easy to compare the achievements in a particular game between you and someone else. Players often report that they try to get at least as many achievements as a friend in a game they both are playing before moving on, or to catch up to a friend's gamerscore total. This adds a competitive multiplayer layer also to single player games similar to what high score lists do.

When I gave a movie trivia game (Screenlife Games, 2007) to my girlfriend as a Christmas gift it turned out that she was much better than me at it and consequently unlocked more achievements. When she then went away on a business trip, I saw my chance to catch up. Since I had an imprint of her playing of the game in the form of her achievement list, I could continue to asynchronously compete against her while she was gone. Similar episodes have happened before, when I have had to "reclaim" high score lists in other games. What was new was that I found myself pausing the game after the question had been asked and looking up the correct answer on The Internet Movie Database in order to get long streaks of correct answers. In a moment of clarity, I suddenly realized what I was doing and how far from my image of myself as a gamer this behavior was.

In contrast to the optional characteristic of achievements as scaffolding, this experience showed a glimpse into the force of the system leading gamers to engage with games in ways that they never thought they would. I did not realize it at the time, but I had ceased playing the trivia game and was at this point only playing the XLMMO.

Achievement Hunters

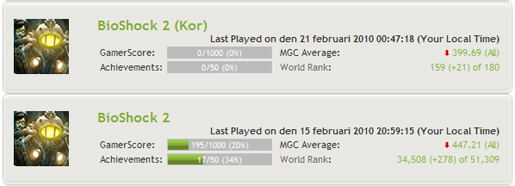

To achievement hunters, the XLMMO has become more important than the separate game titles. For these gamers, it is perfectly natural to play games outside of their preferred genres just to get the gamerscore points. Old sports games and games aimed at children are, for instance, known for giving easy gamerscore points while not always providing the most exciting gaming experience. Sometimes they go through the achievement unlocking process several times for the same game title (a process known as "doubling"), since copies from different regions sometimes give separate achievements (Figure 9).

Figure 9. The Korean and US version of the same game in an achievement hunter's game list. (Source: MyGamerCard.net)

The way achievement hunters approach these games is best described as grinding and is very similar to grinding in other MMOs. Achievement hunters typically care more about the accumulated gamerscore than getting all the achievements in any given game. Their approach is to deplete a game of all its time efficient achievements as quickly as possible and then move on. In this regard, they are closely linked to MMO power gamers as described by Taylor (2006:2) in Play Between Worlds. Her statement that "[t]o outsiders it can look as if they are not playing for 'fun' at all," (p.71) fits achievement hunters as well. Many of the top achievement hunters know each other and while there is a strong rivalry, they often collaborate as boosting partners and by circulating games between each other. (Good, 2009; "High on Live!," 2006)

While there are several pleasures associated with achievement hunting, like the social pleasure of being included in a select group of elite gamers, the main drive is to exhibit skill and dedication to others. These quotes from achievement hunters imply a strong kinship to athletes: "It's very much a personal pride thing, being ranked in the top five in the world in something" (Good, 2009), "I'm never going to be in the Olympics, so I'll be a great gamer" (Good, 2009), “They call me the Game Ruiner. I can completely beat any game in one day" ("High on Live!," 2006).

There is, however, a strong discrepancy between how athletes and achievement hunters are perceived. While athletes are rarely asked why they do what they do, or if they think they are addicted to their sport, these questions always seem to come up when successful achievement hunters are interviewed. If the gamer also happens to be a mother, she can expect questions about how her dedication might affect her family and whether she thinks she should quit [11].

The surrounding community also tends to react negatively to achievement hunters. As an example, in a commenter on a high profile achievement hunter's blog writes: "Your a f**king queer c**t and you need to get out more f**k sake man sort your sh*tty f**king life out you smelly fat american b*****d sad c**t. You have no f**king social life that doesnt involve your f**king xbox 360 now that is f**king sad" (xTBM TaLeNTzZx , 2009, asterisk substitution by the blog tool). There are many potential reasons to the negativity surrounding achievement hunters. The rhetoric often, like in the quote above, focus on how time is spent in an unproductive manner and that having a high gamerscore does not equate to any admirable skills, only to the person "not having a life." This line of argumentation echoes the attitude that the surrounding society often exhibits towards gaming as a whole. To understand why gamers are turning on each other like this, we need to understand console gamers as a community of practice that over time have developed strong internal ethics for what gaming is and should be. Not just the XLMMO, but all MMOs challenge these norms.

Achievement Completists

The concept of completists is used among collectors of everything from records (Plasketes, 2008; Stump, 1997) to memorabilia (Henderson, 2007). Robb describes them as "systematic in his or her approach, collecting everything, or an example of everything, that falls within a certain category" (2009, p.249). Video game completists are different in that they are not collecting games, but rather items and rewards in games such as unlockable character models (MacCallum-Stewart, 2008). They consider games to be unfinished until they have everything, including all achievements, that can be collected in a game. They often self-identify as completists [12] and their approach to gaming leaves a distinctive trace in their achievement records. To these players, achievements make the type of work they always have put into their games more concrete and visible. The way the achievement system puts focus on the aggregate gamerscore is, however, not ideal. A Swedish completist explains:

I like to collect them in certain games (as you know hehe). While in others, I don't care. And I don't care if I have 20.000 or 200.000 gamerscore, if you know what I mean. To me it is worth more to have 1000 p in guitar hero than 10.000 in crap games... At least PSN [Playstation Network] has gold and platinum [trophies], which is good. Then if I have 1000 bronze, it's not as impressive as 10 platinum. (eatem, 2009, author's translation)

Since completists tend to focus on fewer titles than achievement hunters, and instead spend more time on these, they often prefer the Playstation 3 trophy system over the Xbox 360 achievements since the platinum trophies of the former highlights completed games.

Similar to achievement hunting, the struggle to collect everything in a game cannot always be described as fun, but the overall experience can still be very valuable to the player (cf. Taylor, 2006:2, pp.88-92). A 30-year-old dedicated gamer from Sweden described his best achievement memory like this in a forum post:

[It] was when I five stared all songs on expert in Guitar Hero 2 [(Harmonix and Red Octane, 2007)] and 3 [(Neversoft and Red Octane, 2007)].When I nailed those five stars on Raining Blood and Psychobilly Freakout (which were the last songs I had left) the feeling was darned epic. Then when I took Jordan and Through the Fire and Flames [bonus songs giving the "Kick the Bucket" and "Inhuman" achievements], I stood screaming in front of the TV, wonderful. [big smile smiley] Pure happiness, don’t think I felt like that [from playing] any other game ever. [smiley] (eatem, 2008, author’s translation)

Later, he further expanded on the topic of the post and mentioned that getting these achievements were the best gaming experiences he had ever had, and that struggling for months before finally managing to do it was an important factor. He also drew an analogy to World of Warcraft saying: "I spent more time five staring [Raining Blood] than I’ve spent on taking down any boss in WoW. Just like you have to study strategies for the bosses in WoW, I studied strategies and movies to get the optimal 'star power' path" (eatem, 2010, author's translation).

While achievements reinforce already existing structures in games that trigger the need to collect and complete sets of virtual items, they also create new tasks for the completists by introducing another set to complete - the achievements. In the example above, this ended in satisfaction for the gamer, but that is not always the case. In the following podcast extract, games writer Dan Hsu discusses his problems with finishing Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare (Infinity Ward, 2007).

Dan Hsu: I’ve played through Call of Duty 4 on veteran. I have 980 achievement points. I’ve beaten the main game. I think it’s awesome. I want to kill whoever put a one minute time limit on the last airplane level.

Garnett Lee: Oh my god! It’s insane. It’s insane.

DH: Cause I want the achievement. I don’t want to just beat it, but I want the achievement, so I had to play the last airplane level on veteran, the hardest difficulty, I had to do it in a minute. Basically, you don’t even have time to aim your gun. You just have to run

Shane Bettenhausen: Shoe was talking about this earlier, and he has played this one minute level for two hours.

DH: No, no. That's per session. I’ve done that five or six times now.

SB: So you've played this for like ten hours?

DH: I’ve probably put eight hours into this, and I cannot beat it.

GL: Ok.

DH: But I gotta get that last 20 points.

DH: [whispering] I have a sickness.

GL: Yes you do.

SB: Seek help!

DH: But the thing, that’s like the bad thing about achievements. I don’t feel like I’ve completed… (1UP Yours, 2008)

Hsu still has not unlocked the last achievement in Call of Duty 4 and most probably never will. The completists raise the bar for the possible impact of achievements on the overall gaming experience. When it works out, like in the example with eatem, the payoff can be substantial. If it does not work out, the system becomes a powerful source for frustration. The emotional outcomes of the achievement system for completists are, however, not as clear cut as that. After managing to unlock all the achievements in the sequel Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 (Infinity Ward, 2009), Hsu (in another podcast) still seems frustrated with the experience:

Dan Hsu: My problem is I’m quite addicted to all facets of the game. It’s like, I just got a hundred percent. Beat it through on veteran. And…

Anthony Gallegos: Wow!

Arthur Gies: Why would you do that to yourself?

DH: I know, I know, I, like I just tortured myself for however many hours it took but…

AG: How about that Favela? [a level in the game]

DH: Pfheh. Yeah, that sucks. It very much sucks in so many different parts, but… achievements. That’s all I can say. (Rebel FM, 2009)

Hsu is clearly conflicted over the way achievements have changed his gaming habits. In another podcast, he summed it up by saying, "I love them but they’re a curse" (Mobcast, 2010).

Ambiguity

Across all categories of gamers, the ambiguity towards achievements is the strongest theme to emerge from my empirical data. Gamers often only reluctantly admit to caring about achievements and that they allow them to affect the way they play games:

Fruit Brute: [Rez HD (HexaDrive and Q Entertainment, 2008)] is great. I’m really, I’m just so excited that it came out. I played the other day and just, like, played most of the way through it. And it’s got, you know, it’s got some achievements on there so…

Tiny Dancer: Hehehehehe

FB: I know, I talk about achievements a lot, but I’ve turned into a complete achievement whore. It’s really bad. I crave them. Hahahaha. I don’t know why.

TD: That’s what they’re built for.

FB: Hehehe, exactly.

TD: They’re finally working on you.

FB: They make you want them. (GayGamer.net Podcast, 2008)

Fruit Brute seems slightly ashamed and confused about caring about achievements and calls himself an achievement whore, a term commonly used to denote someone who shows too much interest in achievements, but the discussion is lighthearted. The two podcast hosts seem to share an understanding of the appeal of achievements despite not being able to rationalize it. In the next example, Dustin Burg is called out for having played Yaris (Backbone, 2007), a free game on Xbox Live Arcade best known for its low review scores, and tries to explain why he was playing it:

Dustin Burg: I saw somebody on my friends list who had an achievement in Yaris. So then I suddenly was like, well, I want an achievement too. I don’t know why.

David Dreger: Are we a budding achievement whore there Dustin? Are you just like a late bloomer?

Dustin Burg: I just don’t like Yaris but I played it and I should at least have one achievement I figure, because it’s... stupid. God I hate that game. (Xbox 360 Fancast, 2007)

To Burg, it seemed unfair that someone else was getting "free points" so he decided to get some as well. Since the game itself did not provide any enjoyment, he felt that he was at least entitled to an achievement. He seems to feel that he somehow was tricked into playing the game and is looking for someone or something to blame. In the next example, Chris Johnston and Greg Sewart (both former Electronic Gaming Monthly writers) try to blame each other for playing Avatar - The Last Airbender: The Burning Earth (THQ, 2007):

Greg Sewart [to Johnston]: You threw down the gauntlet. Listen. When you booted up Avatar: The Burning Earth. Ok, first… You knew what you were doing, cause I was watching you, and the best part about this was, and I don’t know if I ever told this story on the show…

Chris Johnston: You would have done it even if I hadn’t.

GS: Listen to me, listen to me now. The best part about this is that I was on Live when you did that.

CJ: Yea.

Phil Theobald: Hehehe.

GS: And you totally ignored me.

CJ: That’s right.

GS: You did not have the balls to even admit what you were doing.

CJ: You sent me a message.

GS: And I’m sitting…

CJ: And you sent me a chat request, but I just didn’t bother.

GS: [chuckles] You just kept ignoring me, and I’m sitting there and I saw: Oh CJ’s online cool, so I sent him a chat request and he doesn’t answer.

PT: hehe

GS: And then I’m, you know, I’m playing something else, and I check my list and I see CJ, and he’s playing Avatar - the burning earth, and I’m like: You are fucking kidding me.

PT: hehe

GS: So I click on his name again, and I like, try to chat request. Nothing! And then I send a message like: "I can’t believe you’re doing this. Are you really playing this game just for the easy achievement points you whore."

PT: hehe

GS: Nothing! And then he disconnected. (Player One Podcast, 2007)

The transparency of the system becomes a problem for Johnston when he tries to "get away" with getting some easy achievements. The discussions between gamers regarding achievements often become paradoxical. Sewart and Johnston are clearly engaged in a competition for the highest gamerscore, but at the same time they accuse each other for collecting points. Two Swedish game writers took it one step further when one accused the other of being addicted to achievements. The second writer responded that this was wrong, and to prove it, he suggested a fifty days long competition in achievement hunting. They ended up collecting approximately twenty thousand gamerscore points each and the loser had to retire his gamertag (Spelradion, 2008).

Achievements go against an internalized ideal of gaming that exists within this community of practice. Just as gambling is seen as a violation of these unwritten rules, caring about achievements also goes against what Sutton-Smith (1997) describes as a romantic notion of pure play. But at the same time, the XLMMO is a game, and it provides both competition and a sense of progression. Since they do not accept the XLMMO as a game in its own right, it becomes hard to rationalize the sense of accomplishment that achievements provide. This ambiguity is perfectly summarized by former Electronic Gaming Monthly writer Greg Ford after describing the hardships and distress he went through in getting a notoriously difficult achievement called "Little Rocket Man" (Valve, 2007): "I don't know why I did it. But I did it!" (Player One Podcast, 2009).

Conclusions

Usually when I find a phenomenon so intriguing that I choose to study it, it is because I do not understand the behavior of a group of people. In the case of the achievements, it was the investment some gamers made in the achievement system that I had a hard time understanding. As the study went on, however, I found myself engaging with the XLMMO, and what emerged as more mysterious was the widely spread aversion to achievements within the community.

Much of the outright disgust that some player exhibit against achievements and players who enjoy them appears to spring from the combination of mandatory participation and the coveillant properties of the system. Poster’s (1990) suggestion that the perfection of means of surveillance through new technologies creates a "superpanoptic moment" in which we are not only disciplined to surveillance but to "participating in the process" feels uncomfortably relevant. We could see the use of terms like "achievement whores" as a sign of unease with the system itself which gets directed towards those who have embraced the system and therefore are seen as traitors.

The socially shared aspect of achievements echoes old high score lists in gaming magazines and arcades, but takes it to a completely new level. In this sense, achievements aim at giving gamers something we know is an important factor in many other types of gaming activities; an audience (Medler, 2009). But where professional gaming tries to accomplish this by effectively becoming spectator sports, the achievement system turns everybody into potential audience for everyone else.

It seems that the combination of persistence, coveillance and open-endedness could only lead to a widely appropriated MMO-like engagement with the system by its participants. By linking MMO research to the exploration of achievement systems, we better can understand the way achievements impact gaming habits and at the same time question the way console gaming and MMO gaming is seen as worlds apart.

In hindsight, it is hard to imagine the achievement system to have had any other results on how people play and engage with Xbox Live. It would seem that we are watching technological determinism at work here. But as Winner points out: "What matters is not technology itself, but the social or economic system in which it is embedded... [This maxim] serves as a needed corrective to those who focus uncritically upon such things as 'the computer and its social impacts' but who fail to look behind technical devices to see the social circumstances of their development, deployment, and use" (1980, p.122). In this case, it is important to note that both the drive to take on completely arbitrary challenges without questioning their validity, and the enjoyment derived from fighting, circumventing and subverting rigid rule systems are fundamentally connected to gaming culture and the pleasures of play (Consalvo, 2007; Salen and Zimmerman, 2003). The different strategies and ways of conceptualizing the system shows how players have appropriated the technology and socially reconstructed it to fit their gaming pleasures, while at the same time, many players remain deeply conflicted over these gaming habits and feel trapped in a deterministic system dictating to them what to do.

To me, the perfect image for this duality is the xBot (Figure 10), or as I prefer to think of it, the achievement machine. When car mechanic David Harr from Seattle, realized he needed to add another 40 hours to the 50 he had already spent playing Perfect Dark Zero (Rare, 2005), to earn the last achievements in the game, he decided he needed an alternate solution. "I reverse engineered the problem and came up with the xBot," ("Gamer builds ‘auto-play machine'," 2007) he said.

Figure 10. The xBot. (Source: Official Xbox Magazine)

The machine starts a multiplayer game (with bots as opponents) only to exit the game again once it has been running long enough to register for the achievement. The machine can go through around 40 games in an hour which meant that he got the two last achievements (Figure 11) in a day or so. But the best part was that he did not have to do it himself ("The xBot," 2007).

Figure 11. Grind-heavy achievements in Perfect Dark Zero. (Source: Xbox360Achivements.com)

To Mr. Harr, skipping the last two achievements because they were stupid was apparently not an option; instead he played the XLMMO in the way that granted him the most satisfaction. I find it simply poetic that his rage against the machine manifested itself in the form of a machine.

References

1UP Yours. (2008). January 25. Podcast. Retrieved July 11, 2010 from "http://www.1up.com/do/minisite?cId=3149993

"Achievements." (2010). Giant Bomb. Retrieved March 8, 2010 from http://www.giantbomb.com/achievements/92-29/

Activision. (1982). Chopper Command. [Atari 2600], Activision.

"Activision Patch Gallery." (n.d.). Atari Age. Retrieved August 28, 2010 from http://www.atariage.com/2600/archives/activision_patches.html

Bach, Robbie, Allard, J, & Moore, Peter. (2005). Microsoft Press Conference at Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3) 2005. Retrieved August 31, 2010 from http://www.microsoft.com/presspass/exec/rbach/05-16-05e3.mspx

Backbone. (2007). Yaris. [Xbox 360]. Microsoft.

Bethesda. (2008) Fallout 3. [Xbox 360], Bethesda.

Bizarre Creations. (2006). Project Gotham Racing 3. [Xbox 360], Microsoft.

Bland, Seth. (2009). Achievements: Blessing or Curse? Darkzero. Retrieved March 8, 2010 from http://darkzero.co.uk/blog/achievements-blessing-or-curse/

Blizzard Entertainment. (2004). World of Warcraft. [PC], Blizzard Entertainment.

Bogost, Ian. (2010). Persuasive Games: Check-Ins Check Out. Gamasutra. Retrieved January 30, 2011 from http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/4269/persuasive_games_checkins_check_.php

Bungie. (2007). Halo 3. [Xbox 360], Microsoft.

CAGcast. (2010). Episode 209: Calling All Farts! August 19. Podcast. Retrieved August 22, 2010 from http://podcast.com/show/4388/

Cavalli, Earnest. (2008). World of Warcraft Hits 11.5 Million Users. Wired. Retrieved August 22, 2010 from http://www.wired.com/gamelife/2008/12/world-of-warc-1/

Cole, Vladimir. (2006). $300 for 3,000 XBL gamer points?!. Joystiq. Retrieved November 21, 2007 from http://www.joystiq.com/2006/10/03/300-for-3-000-xbl-gamer-points

Consalvo, Mia (2007). Cheating. Gaining Advantage in Videogames. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

"Description of Xbox 360 gamer profiles." (2010). Xbox.com. Retrieved August 22, 2010 from https://support.xbox.com/support/en/us/nxe/kb.aspx?ID=905882

Dibbell, Julian. (2006). Play Money. Or, How I Quit My Day Job and Made Millions Trading Virtual Loot. New York: Basic Books.

EA Canada. (2007) NBA Live 08. [Xbox 360], Electronic Arts.

EA Games. (2007). The Simpsons Game. [Xbox 360], Electronic Arts.

EA Sports. (2006). NBA Live 07. [Xbox 360], Electronic Arts.

eatem. (2008). Spelradion. November 4. Forum post. Retrieved November 6, 2008 from http://spelradion.forum24.se/viewtopic.php?p=17671#17671

eatem. (2009). Windows Messenger conversation. September, 25.

eatem. (2010). Quoted in blog post. April 12. Retrieved April 13, 2010 from http://www.emmyz.net/2010/04/12/vinnaren-i-borderlandstavlingen/

Electronic Entertainment Design and Research. (2007). EEDAR Study Shows More Achievements in Games Leads To Higher Review Scores. Press release. Retrieved August 22, 2010 from http://www.eedar.com/News/Article.aspx?id=9

Game Scoop! (2009) Episode 104. January 9. Podcast. Retrieved July 12, 2010 from http://games.ign.com/articles/943/943631p1.html

"Gamer builds ‘auto-play machine." (2007). BBC News. Retrieved November 21, 2007 from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/6396925.stm

GayGamer.net Podcast. (2008). Episode 16. February 6. Podcast. Retrieved July 12, 2010 http://gaygamer.net/podcast/GG_Podcast_16.mp3

Good, Owen. (2009). Achievement Chore: She Plays For Gamerscore, Whether It's Fun Or Not. Kotaku. Retrieved March 9, 2010 from http://kotaku.com/5422154/achievement-chore-she-plays-for-gamerscore-whether-its-fun-or-not

Greenberg, Aaron. (2007). Addicted to Achievements? Gamerscore Blog. Retrieved August 25, 2010 from http://gamerscoreblog.com/team/archive/2007/02/01/540575.aspx

Harmonix & Red Octane. (2007). Guitar Hero 2. [Xbox 360], Activision.

Hecker, Chris. (2010). Achievements Considered Harmful? Game Developer Conference 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2010 from http://chrishecker.com/Achievements_Considered_Harmful%3F

Henderson, Stephen. (2007). Fan behaviour. A World of Difference. EuroCHRIE Conference 2007, October 25th -27th. Leeds.

HexaDrive & Q Entertainment. (2008). Rez HD. [Xbox 360], Q Entertainment.

"High on Live!" (2006). Official Xbox Magazine. Retrieved November 21, 2007 from http://www.computerandvideogames.com/article.php?id=147693

The Hotspot. (2007). December 4, 2007. Podcast. Retrieved August 10, 2010 from http://www.gamespot.com/video/0/6183660/the-hotspot-12-04-07

Hyman, Paul. (2007). Microsoft has gamers playing for points. The Hollywood Reporter. 4 Jan 2007.

Infinite Interactive. (2007) Puzzle Quest: Challenge of the Warlords. [Xbox 360], D3.

Infinity Ward. (2007). Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare. [Xbox 360], Activision.

Infinity Ward. (2009). Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2. [Xbox 360], Activision.

Io Interactive. (2007). Kane & Lynch: Dead Men. [Xbox 360], Eidos.

Jakobsson, Mikael. (2006). The Quest for Knowledge. The importance of time in socio-cultural studies of online environments. In Schroeder, Ralph & Axelsson, Ann-Sofie (eds.) Avatars at work and play: Collaboration and interaction in shared virtual environments. London: Springer.

Jakobsson, Mikael. (2007). Playing with the Rules. Social and Cultural Aspects of Game Rules in a Console Game Club. In Akira, Baba (ed.) Proceedings of the Digital Games Research Association Conference: Situated Play. Tokyo: University of Tokyo.

Jakobsson, Mikael & Taylor, T.L. (2003). The Sopranos Meets Everquest. Social networking in massively multiuser networking games. Fine Art Forum. 17:8.

Järvinen, Aki. (2009). Psychology of Achievements & Trophies. Gamasutra. Retrieved August 24, 2010 from http://www.gamasutra.com/blogs/AkiJarvinen/20090305/709/Psychology_of_Achievements__Trophies.php

Lave, Jean; Wenger, Etienne. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McCallum-Stewart, Esther. (2008) Real Boys Carry Girly Epics: Normalising Gender Bending in Online Games. Eludamos. Journal for Computer Game Culture. 2:1. pp.27-40

McElroy, Griffin (2010) Windows Phone 7 Achievements to feature up to 200 Gamerscore points per game. Joystiq. Retrieved August 25, 2010 from http://www.joystiq.com/2010/03/10/windows-phone-7-achievements-to-feature-up-to-200-gamerscore/

Medler, Ben. (2009). Generations of Game Analytics, Achievements and High Scores. Eludamos. Journal for Computer Game Culture. 3:2. p. 177-194.

Microsoft. (2008). Xbox.com. Retrieved March 1, 2008 from http://www.xbox.com/sv-SE/myxbox/myprofile.htm

"Microsoft Online - From The Zone to Xbox Live." (2004). Mega Games. Retrieved August 29, 2010 from http://www.megagames.com/news/microsoft-online-zone-xbox-live

Mobcast. (2010). Episode 40. February 8. Podcast Retrieved June 9, 2010 form http://feeds2.feedburner.com/Mobcast

Neversoft & Red Octane. (2007). Guitar Hero 3. [Xbox 360], Activision.

Oasaka Jim. (2008). A Beginner's Guide to Boosting. Xbox 360 Achievements. Retrieved February 16, 2008 from http://www.xbox360achievements.org/forum/showthread.php?t=51558

Plasketes, George. (2008). Pimp My Records: The deluxe dilemma and edition condition: Bonus, betrayal, or download backlash? Popular Music & Society. 31:3. pp. 289-393.

Player One Podcast. (2007). Episode 61: A Holly, Jolly Mega Man X-Mas. December 23. Podcast. Retrieved July 11, 2010 from http://traffic.libsyn.com/playerone/12_24_07-Episode61.mp3

Player One Podcast. (2009). Episode 118. Teased By Spoilers. January 26. Podcast. Retrieved July 12, 2010 from http://playerone.libsyn.com/index.php?post_id=426289#

Player One Podcast. (2010). Episode 167: Best of the Aughts. January 4. Podcast. Retrieved July 9, 2010 from http://traffic.libsyn.com/playerone/01_04_10-Episode167.mp3

Poster, Mark. (1990). The mode of information. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ransom-Wiley, James. (2007). Join 1,000 NBA Live players, boost your Gamerscore. Joystiq. Retrieved November 21, 2007 from http://www.joystiq.com/2007/02/05/join-1-000-nba-live-players-boost-your-gamerscore/

Rare. (2005). Perfect Dark Zero. [Xbox 360], Microsoft.

Realtime Worlds. (2007). Crackdown. [Xbox 360], Microsoft.

Rebel FM. (2009). Episode 43. September 9. Podcast. Retrieved July 12, 2010 from http://traffic.libsyn.com/rebelfm/Rebel_FM_Episode_43_-_120909.mp3

Reiss, Steven. (2004). Multifaceted Nature of Intrinsic Motivation: The Theory of 16 Basic Desires. Review of General Psychology, 8:3, 179-193.

Robb, Jenny. (2009). Bill Blackbeard: The collector who rescued the comics. Journal of American Culture. September. 32:3. pp. 244-256.

Salen, Katie & Zimmerman, Eric. (2003). Rules of Play. Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Schell, Jesse. (2010). Design Outside the Box. Design Innovate Communicate Summit 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2010 from http://g4tv.com/videos/44277/dice-2010-design-outside-the-box-presentation/

Screenlife Games. (2007). Scene It? Lights, Camera, Action. [Xbox 360], Microsoft.

Simon, Bart, Boudreau, Kelly & Silverman, Mark. (2009). Two Players: Biography and ‘Played Sociality’ in EverQuest. Game Studies. 9:1.

Sliwinski, Alexander. (2007). EA's NBA Live cover Gilbert Arenas prefers NBA 2K series. Joystiq. Retrieved October 3, 2008 from http://www.joystiq.com/2007/05/16/eas-nba-live-cover-gilbert-arenas-prefers-nba-2k-series/

Sony Online Entertainment. (1999). Everquest. [PC], Sony Online Entertainment.

Sotamaa, Olli. (2010). Game Achievements, Collecting and Gaming Capital. In Mitgutsch, K., Klimmt, C. & Rosenstingl, H. (Eds.), Exploring the Edges of Gaming: Proceedings of The Vienna Games Conference 2008-2009. Vienna: Braumüller.

Spelradion. (2008). Spelradions achievement-special. June 4. Podcast. Retrieved September 1, 2010 from http://media.libsyn.com/media/spelradion/Spelradions_achievement-special.mp3

Steinberg, Dan. (2007). Is Gilbert Cheating at Halo? The Washington Post. Retrieved October 15, 2009 from http://blog.washingtonpost.com/dcsportsbog/2007/10/is_gilbert_cheating_at_halo.html

Stump, Paul. (1997). Digital Gothic: a critical discography of Tangerine Dream. Wembley: SAF Publishing.

Sutton-Smith, Brian. (1997). The Ambiguity of Play. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Takahashi, Dean. (2006). The Xbox 360 Uncloaked. The real story behind Microsoft’s next-generation video game console. [S.l.]: Spiderworks.

Taylor, T. L. (2006:1). Does WoW Change Everything? Games and Culture. 4:1.

Taylor, T. L. (2006:2). Play Between Worlds: Exploring Online Gaming Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Thorsen, Tor. (2009) 28 million Xbox 260s sold, 17 million on Xbox Live. Gamespot. Retrieved August 1, 2009 from http://www.gamespot.com/news/6202733.html

THQ. (2007). Avatar - The Last Airbender: The Burning Earth. [Xbox 360], THQ.

Ubisoft Montpellier. (2005). Peter Jackson's King Kong: The Official Game of the Movie. [Xbox 360], Ubisoft.

Valve. (2007). The Orange Box. [Xbox 360], EA Games.

Wikipedia. (2010). MSN Games. Retrieved August 29, 2010 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MSN_Games

"The xBot." (2007, November 28). Official Xbox Magazine Online. Retrieved August 31, 2009 from http://www.oxmonline.com/article/features/xbox-365/xbox-nerd-corps/xbot

Xbox 360 Fancast. (2007). Episode 41. Organized Sports. November 5. Podcast. Retrieved February 27, 2008 from http://www.joystiq.com/2007/11/05/xbox-360-fancast-041-organized-sports/

xTBM TaLeNTzZx. (2009). 1 Million Gamerscore. Retrieved August 29, 2009 from http://www.1milliongamerscore.com/

Endnotes

[1] There are even podcasts exclusively dedicated to Xbox 360 achievements.

[2] Games stored on DVDs in plastic boxes sold by brick and mortar retailers such as GameStop, Game and Wal-Mart.

[3] Smaller downloadable games usually priced between US$5 and US$15.

[4] The Playstation 3 equivalent to achievements is called trophies.

[5] The site has changed names many times. Some of the other names include The Village, Internet Gaming Zone, MSN Gaming Zone and Zone.com.

[6] Xbox Live had been introduced for the original Xbox, three years before the launch of the Xbox 360.

[7] At the Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3) 2005. Robbie Bach, Senior Vice President and Chief Xbox Officer, Home and Entertainment Division, Microsoft, talked about "VelocityGirl," a persona representing the creative non-gamer that would be drawn to the system because it would provide an audience for her creativity. She would be able to design and sell stickers, t-shirts and soundtracks to other gamers. (Bach et al., 2005) That was, however, the last time Microsoft mentioned her or the possibility for Xbox Live member to sell content to each other.

[8] World of Warcraft also has achievements, which makes it a MMO within a MMO.

[9] To become an Xbox Live member you have to sign up online. It is enough to have a silver membership to earn achievements, but the lack of online play makes some of the achievements unattainable.

[10] This kind of initiatives crop up from time to time and tend to lead to considerable bitterness if they fail (Ransom-Wiley, 2007).

[11] This may be true for athlete mothers as well.

[12] The term completionist is also commonly used. In Sweden they are known as hundred per centers.