“Why do I have to make a choice? Maybe the three of us could, uh...”: Non-Monogamy in Videogame Narratives

by Meghan Blythe Adams, Nathan RambukkanaAbstract

This paper investigates non-monogamy in videogames. As with LGBQT* issues, open non-monogamies are slowly making their way into multiple media forms (Rambukkana, 2015b). As the world of gaming becomes more layered and complex, non-monogamies gain in prominence both in game narratives, and in game cultures—from guilds and blog communities, to using in-game characters to cheat on RL relationships. These shifts in the texture of digital intimacy reflect and affect cognate shifts both in other mediascapes and in culture as a whole. Building on previous work on fringe and anti-normative sexuality in games (e.g., Consalvo, 2003; Shaw, 2013, 2015), this paper examines tropes of non-monogamy as an element of game and story design in AAA games and series (or similar) such as The Witcher, Catherine, Mass Effect, Dragon Age and Jade Empire. Do representations of non-monogamies in game narratives break with or reinforce mononormative and heteronormative tropes? How might challenging the normative dynamics of compulsory monogamy open up new and more complex game dynamics and narratives? We conclude that while representation of non-monogamy is growing, it is still largely along normative lines, but also that some alternative portrayals do exist and have the potential to add more complex and diverse narratives to mainstream games.

Keywords: non-monogamy, videogames, normative sexuality, narrative, cheating, polyamory, transgressive play, queer play, Mass Effect, The Witcher 3

Introduction: Non-Monogamy in Digital Media

It is an open secret that non-monogamy is gaining in societal prominence. From mundane adultery; to problematic polygamy; to iconoclastic polyamory; to swinging, swapping, experiments, and hook-up culture generally; both open and closed non-monogamies are making a place for themselves in the contemporary world (Rambukkana, 2015b)[1]. And a huge part of that place is a growing presence across a diversity of media forms, in ways similar to the earlier slow but paradigm-shifting integrations of LGBQT* issues into the public sphere. In fact, one might be hard-pressed to find a form of media untouched in some way by non-monogamous intimacies. This is particularly the case for digital media.

Non-monogamies have a fraught relationship with digital culture. On the one hand, digital culture is a vector along which alternative and intentional sexual cultures propagate, and a way that novices and the curious alike can explore such cultures without steep initial identity commitments (Rambukkana, 2007). This is certainly the case with open non-monogamous sexual subcultures online, with online dating cultures—in particular LGBQT* ones—opening the door to more flexible relationships with monogamy (e.g., Brady, Iantaffi, Galos & Rosser, 2012; Race, 2015). This flexibility of relationships and openness to experimentation also extend to the growing "hookup culture" enabled, in part, by casual dating apps such as Tinder (2012) and Grindr (2009). Meanwhile, polyamory culture is all over the web, from online magazines such as Loving More (1994) and podcasts such as Polyamory Weekly (1999), to websites and forums of all types. Even more traditional open non-monogamies such as conventional polygamy [2] and swinging have digitally mediated aspects. For example, there are extensive online message boards and chat sites for those in both Christian (e.g., Sweet-McFarling, 2014) and Islamic (e.g., Bati & Atici, 2011) polygamies, as well as fora where polygamy is hotly debated by Muslim women (Piela, 2012, p. 66). Swinging (or "Lifestyle" culture) also has an extensive network of websites (Kreston, 2014). Yet such spaces might not be safe for many to occupy, due to family networks, careers, immigration status, etc., or otherwise might seem inaccessible due to gender, class, and race barriers (Rambukkana, 2015b).

For secretive non-monogamies such as adultery, digital culture is equally fraught. In India, for example, social media is cited as a contributing factor in as many as two thirds of all infidelity cases (Mehra, 2014)—from social media enabling windows into our exes' and crushes' everyday lives (Mehra, 2014), to pro-adultery websites such as Ashley Madison (Rambukkana, 2015b). But the converse is also present, with websites and apps that allow those with worries or paranoia to surveil their potentially dallying partners (Mehra, 2014; Gregg, 2013) or to "out" those who have previously cheated, as with the site CheaterVille.com (PR Newswire, 2011).

Together, the evidence for the growing digital mediation of non-monogamies is extensive, but one field that has yet to fully investigate this emergence is videogame studies[3]. Just as the backdrop of the increasing digital mediation of non-monogamies is important for understanding why we are starting to see it in games, understanding the ways it appears in games so far addresses a gap in the study of digital non-monogamy. This cross-disciplinary paper takes a more specific look at the digital mediation of non-monogamies as it surfaces in the world of videogames[4]. As both game narratives and game cultures become more layered and complex, non-monogamies within them gain in prominence. These shifts in the texture of digital intimacy reflect and affect cognate shifts both in other mediascapes and in culture as a whole.

Building on previous work on fringe and anti-normative sexuality in games (e.g., Consalvo, 2003; Shaw, 2013, 2015; Adams, 2015), this paper examines tropes of non-monogamy in videogames, focusing on non-monogamy as an element of game and story design in AAA games and series, or similar, such as The Witcher, Catherine, Mass Effect, Dragon Age and Jade Empire[5]. Queer indie and alternative games (such as Christine Love's Ladykiller in a Bind and Anna Anthropy and Leon Arnott's Triad) have been a rich site of representations of non-monogamy, and player associations (such as the bipolypagangeek guild in World of Warcraft (Blizzard, 2004)) have brought attention to non-monogamy in broader gaming cultures. However, AAA and other large-studio game narratives arguably have the greatest social currency and the broadest impact and reach. As such, when alternative sexualties appear in them, as with Hollywood movies such as Fifty Shades of Grey (Brody & Taylor Johnson, 2015), they are of especial note and worthy of deeper consideration—regardless of the quality of the representation. Two key questions we will address are:

- Do representations of non-monogamies in game narratives break with or reinforce mononormative and heteronormative tropes?; and

- How might challenging the normative dynamics of compulsory monogamy open up new and more complex game dynamics and narratives?

Cheating and Non-Monogamy (not the same)

There is much popular discussion of non-monogamy in the context of games, but this seems almost exclusively with respect to "avatar cheating," or people using game characters or personas to cheat on RL relationships (e.g., Alter, 2007; Hartley, 2009). Given the easy elision of the concepts of "cheating" and "non-monogamy" in society as a whole, it is perhaps useful to consider non-monogamy's appearance in the videogame world with respect to Mia Consalvo's reflections on cheating in videogames generally. In Cheating (2007), Consalvo explores the notion of whether "there is one 'correct' way to play" games (p. 2). She discusses game manuals and other paratexts that give you further information about how one plays a particular game, but notes that the one thing they don't tell you, at least fully, is the rules:

The rules of a videogame are contained within the game itself, in the game code. The game engine contains the rules that state what characters (and thus players) can and cannot do: they can go through certain doors, but not others; they can't walk through walls or step over a boulder (except maybe a special one); they can kill their enemies, but not their friends and they must engage in certain activities to trigger the advancement of the story and the game. All of these things are structured in the code of the game itself, and thus the game embodies the rules, is the rules, that the player must confront. (Consalvo, 2007, p. 85)

The rules of video game spaces define those spaces and their affordances. The code is also the law (p. 85). However, this has two provisos. The first is that the law, rules, or code could be altered or subverted: by hacking, by modding, or through discovering loopholes or glitches that allow you to cheat the system in some way. The other proviso is that in some games and game spaces the social aspects of the rules might be subverted in other ways, or else not be hard-coded in the first place.

We can consider non-monogamy in game spaces a form of "rule breaking" which, depending on the particular game space, might run against the grain of the code itself, and therefore be disallowed; might be possible in the experience of play, either through attempting to subvert the actual gameplay, or through hacking/ modding; or might be an aspect of play either governed more by convention than code or not governed at all, allowing such non-monogamies to proliferate undisturbed by the affordances of the game itself. Like Consalvo, Huizinga suggests we consider games as special places in the world where specific rules hold sway:

All play moves and has its being within a play-ground marked off beforehand either materially or ideally, deliberately or as a matter of course. Just as there is no formal difference between play and ritual, so the "consecrated spot" cannot be formally distinguished from the play-ground. The arena, the card-table, the magic circle, the temple, the stage, the screen, the tennis court, the court of justice, etc., are all in form and function play-grounds, i.e. forbidden spots, isolated, hedged round, hallowed, within which special rules obtain. All are temporary worlds within the ordinary world, dedicated to the performance of an act apart. (1950/2014, p. 10)

This "magic circle" theory, as it has become popularly known, posits that the space of game play is a space set apart, a heterotopia of sorts (or, other space) (Foucault, 1986) which plays by its own rules, as it were, ones players qua players are subject to (Aarseth, 2007, p. 130). Complicating this framing, Shaw builds off of Rubin's classic concept of a "charmed circle" of privileged sexualities, in which those practices at the centre (for example, heterosexuality, marriage, monogamy) are considered normal and natural and those at the fringes (for example, homosexuality, pornography, sex work) troubling or suspect (2015, p. 80)[6]. She investigates how certain forms of gaming might, similarly, be considered normative or fringe by both the mainstream and among gamers. Within the latter list is playing by the rules versus cheating (p. 83). In playing against the grain of assumed monogamous game dynamics, player choices could be seen as running afoul of both Shaw's and Rubin's charmed circles both—which could explain why (as discussed below) at times games will be especially pointed in rebuffing such attempts, even going so far as to punish players for attempting to subvert normative game play.

As Huizinga notes (1950/2014, p. 11) and Shaw amplifies (2015, p. 84), while the cheat acknowledges the rules of the game, but might act within them in bad faith to gain advantage (e.g., hiding an ace up their sleeve, counting cards), they are sometimes tolerated more than the "spoil-sport" who actively disregards the rules and therefore breaks the magic circle, shattering the covenant that creates "the temporary world circumscribed by play" (Huizinga, 1950/2014, p. 11). In contrast to the "cheat" and the "spoil-sport," we bring in the possibility of a player who pursues the "queer phenomenology" proposed by Sarah Ahmed (2004, 2006). Sundén (2012, p. 172) and Youngblood (2015, p. 240) apply Ahmed's queer spatiality to queer Aarseth's (2007) notion of transgressive play. Instead of pursuing "straight lines" of movement which, as Ahmed writes "might be a way of becoming straight, by not deviating at any point" (2006, p. 14), the player-as-transgressor queers that straight progression. We, however, examine the possibility of queer transgressive play that seeks to pursue multiple lines of romantic progression through the game-space simultaneously: their progression aims to be plural where it is supposed to be singular. Read solely in terms of the encoded rules of most games, this would be cheating; and read solely in terms of a mononormative (read: monogamy-privileging[7]) worldview, it would be cheating of a different kind. However, our transgressive player seeks not to cheat the rules (or their in-game love interests), but rather to challenge mononormative play.

In this paper we focus on how normative sexualities and expectations are at play in how non-monogamies surface in scripted game narratives, and how the rules of the narrative play out ludically in both the game design and user experience.

Contextualizing Monogamy and Non-Monogamy in Videogame Narratives

Monogamous heterosexual pairings are one of the core tenets of videogame history and culture. The plot device of the stolen princess in need of rescue by her male hero is, alone, a hugely long-lasting and influential one in gaming. Mia Consalvo notes in "Hot Dates and Fairy Tale Romances: Studying Sexuality in Video Games" (2003) that in the case of early arcade game Donkey Kong (Nintendo, 1981) "It was presumed that a 'rescue the princess' theme was sufficient back-story to explain why someone would want to dodge barrels and climb ladders and it worked" (2003, p. 172). In the case of Donkey Kong and many games since (Sarkeesian, 2013), this delay in the hero and princess's union is what enables the plot and much of the gameplay. This plot has sustained innumerable games and its valorization of the monogamous heterosexual pairing is a standard trope in the medium.

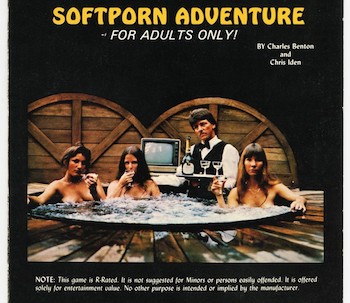

Figure 1. The racy cover art of Softporn Adventure, implying the possibility of a non-monogamous scene (Blue Sky Software, 1981). Image from Nooney, L. (2014, December 2). The odd history of the first erotic computer game. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2014/12/the-odd-history-of-the-first-erotic-computer-game/383114/.

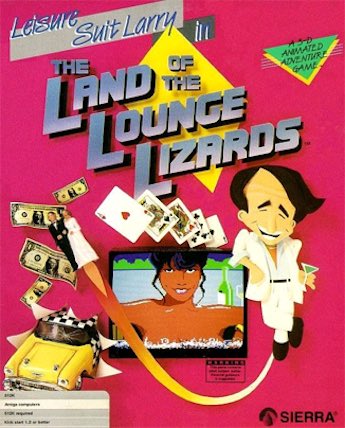

The prevalence of this standard union contrasts with the scarcity of mainstream games that explore alternative relationship models. Within a North American context, these rare exceptions were largely limited to the adult market. The first known commercial "erotic" title was the text-based "computer fantasy game" Softporn Adventure (Blue Sky Software, 1981; see Figure 1). This gawky but earnest game, despite "exhausting chauvinism and wearied sexism" (Nooney, 2014), broke ground for the commercial release of adult titles (Nooney, 2014). And when its distributor On-Line Systems moved from text-based to graphical games and rebranded itself as Sierra On-Line, Softporn Adventure was used as the inspiration for Sierra's and Codemaster's Leisure Suit Larry series, perhaps some of the most famous early adult games[8]. Beginning with Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards (Sierra, 1987), entries in the series feature Larry Laffer (or later, his nephew Larry Lovage) seeking sexual partners (see Figure 2). However, the series typically still has Larry finish the game with one romantic partner—who often breaks up with him to necessitate the next installment.

Figure 2. Cover art of Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards, showing Larry literally "sending up" a symbol of monogamy (Sierra, 1987). Image from Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards. (2017, May 12). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21:29, June 27, 2017, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Leisure_Suit_Larry_in_the_Land_of_the_Lounge_Lizards &oldid=780071029.

The Leisure Suit Larry series was largely focused on risqué humour, rather than a great deal of explicit content. In comparison, games with varying degrees of explicit content, called erogēs, have been popular in Japan since the 1980s (Eroge, 2017). Also popular in Japan are visual novel dating simulations, which also have varying degrees of explicit content. Typically, however, both Eastern and Western visual novel dating sims typically have one chief romantic partner per ending, much like the Larry series.

Because the Japanese erogē has a complex history and context of its own (e.g., see Galbraith, 2011), this paper focuses on representations of non-monogamous romantic content in mainstream Western adventure role-playing games. More recently, and particularly since 2000, some adventure role-playing games have featured romantic side-quests and other opportunities for player-characters to pursue romantic relationships in-game with non-player characters (NPCs). These opportunities differ from romance in massively-multiplayer online games (MMOs) such as World of Warcraft (Blizzard, 2004) and Second Life (Linden Labs, 2003) not only because potential partners in these cases are NPCs rather than other human players, but also because these romantic options must be scripted ahead of time and coded into the game. In order to exist, these relationships must be designed and implemented by the games' developers. As a result, the opportunities to pursue relationships are limited to what is included in the games' scripts, in contrast to the person-to-person relationships that find ways to exist in MMOs. In other words, while an MMO player may spontaneously decide to romantically pursue another player independent of the game's code, an NPC's availability for sex and romance is limited to what has been explicitly written into the game.

Typically, characters in these games can pursue flirtations with multiple NPCs but only romance one (see Catherine, Dragon Age, The Witcher). Notably in the Fable series (Lionhead, 2004, 2008, 2010) and The Witcher series (CD Projekt RED, 2007, 2012, 2015), the player-character can have sex with particular NPCs if certain conditions are met (usually raising the NPC's favour towards you in Fable 1, 2, and 3 and giving specific gifts or dialogue choices in The Witcher series). However, the ability of player-characters to pursue sex throughout a game is still limited. As noted by Hart, Fable's NPCs have very little personality and romantic and sexual engagement with them is rudimentary (2015, p. 155). In The Witcher, the player-character has a wide range of potential sexual partners in the first and second installments of the game, but a maximum of two primary romantic options in each game in the series (as discussed below). More commonly, player-characters pursue one chief romance that culminates in a sexual experience near the end of the game. This arc is particularly associated with Canadian game development team BioWare: their games Jade Empire (2007a), Dragon Age: Origins (2009), and Mass Effect (2007b) all feature this plot progression.

Opportunities for consensual non-monogamy in games are rare. Much more commonly, games depict adultery or romantic rivalry. Typically if the player-character is caught attempting to pursue multiple official relationships (marriages in Fable, "locked-in" romances in Mass Effect), the player is either punished (e.g., with divorce in Fable) or chided to choose one to pursue (as in Mass Effect). Consensual non-monogamy is virtually unheard-of in these games, save in the relatively rare case of a player-character pursuing one romantic interest and having implied sexual relations with additional partners within the context of that relationship.

For example in Jade Empire, upon passing a difficult persuasion check in dialogue, a male player-character can romance the princess Silk Fox and have unseen sex with her and another romantic interest named Dawn Star. However, this depends on achieving both the persuasion check and "hardening" Dawn Star's personality through earlier dialogue choices. The achievement still counts as a romance with Silk Fox. This arrangement depends on Dawn Star becoming a less empathic person for her to be able to take part in the unseen threesome, suggesting that the ability to take part in group sex requires a harsher personality. The player-character achieves this threesome by confusing means, which indicate the tensions inherent in the presentation of the romance. He must consistently refuse to choose between the two women, even as they repeatedly insist he must. However, in the final conversation on the topic, choosing one of them ends both romances: to progress, the player must continue to refuse to choose. Yet the epilogue treats the romance as if it solely included Silk Fox. The insistence on the part of the two women that the player must choose is mononormative but their refusal to be chosen (and acceptance of the threesome) at a late stage suggests a willingness to challenge mononormativity. The resulting achievement "Two out of three ain't bad" tacitly endorses (and sensationalizes) the threesome as a sex act, while the framing of Dawn Star as having not been romanced suggests that the act was only sexual. This contrasts to each woman's refusal to let the other be "hurt" by the player's late stage choice. The game's treatment of the threesome and its romantic potential is thus contradictory. It is less an incident of queer spatiality in multiple lines of romantic progression (as discussed earlier) than it is an expression of deep ambivalence regarding non-monogamy.

In the further example of Catherine (Atlus, 2011), if the player-character Victor successfully romances and marries succubus Catherine and earns her True ending, the player-character becomes King of the Netherworld and appears to have a harem of succubi in addition to his wife. However, in both of these cases, the primary partner is the official one, and the implied non-monogamous sex has no other bearing on the story. Both achievements function much more like player rewards than extended depictions of consensual non-monogamy in general, or polyamory in particular: this functions similarly to how Fable 3 rewards the player with improved weapons for having multiple sexual partners (Hart 2015, p.155). Both the more-standard trope of one sexual and romantic love interest per player-character and the rarer incidences described in Jade Empire and Catherine presume that romance is inherently monogamous. Efforts to circumvent this are treated as running counter to both a) societal mores in the game, and b) the rules of the game—making both ludic impasses. Since, as Consalvo puts it above "the game embodies the rules, is the rules" (2007, p. 85), playing against the grain and attempting to pursue queered or alternative narrative paths threatens to break the magic circle and must be corrected—sometimes with major in-game consequences. Two case studies in particular depict this combination of trespasses.

Mass Effect: "I'm Aware of the Concept of Jealousy"

Ironically described as featuring "graphic digital nudity" by Fox anchor Martha MacCallum and as a gateway to "virtual orgasmic rape" by conservative commentator Kevin McCullough, BioWare's Mass Effect series in reality evidences a fairly conservative philosophy of relationships (Fox News, 2008; McCullough, 2008). However, the outcry in response to the game's perceived content did not refer to its queer content or even the game's brief reference to the possibility of consensual non-monogamy: instead, commentators focused on the notional presence of graphic sex and sexual assault, showing a fundamental misunderstanding of what actually took place in the game. Substantial research on the romantic and sexual possibilities allowed in the series exists (Adams 2015; Hart 2015; Glassie 2015), but the actual content of the game is less diverse. In the first three entries in the series[9], player-character Commander Shepard has multiple potential romantic partners, but can seriously pursue only one at a time. Hart notes a significant numerical imbalance among the relationships: a male Shepard can pursue only two queer relationship routes and nine heterosexual relationships across the series, while a female Shepard has seven queer romances and four heterosexual ones (2015, p. 153). In addition to the clear slanting of a male Shepard toward heterosexual relationships and a female Shepard toward queer ones, Shepard cannot pursue consensual non-monogamy. If the player-character attempts to pursue multiple relationships, NPCs will typically inform Shepard to end their previous romance first before pursuing them further: barring bugs in the game's code, Mass Effect's relationships are only intended to progress in a singular, straight line.

One important exception to this pattern is the result of Shepard's attempts to pursue non-monogamy in the first Mass Effect (BioWare, 2007b). If a male Shepard attempts to romance both human crewmember Ashley Williams and alien scientist Liara T'Soni, or a female Shepard attempts to romance human crewmember Kaiden Alenko and Liara, the two characters will confront Shepard and indicate that Shepard must choose between them. However, in both cases, Liara notes her differing perspective from the other potential romantic interest when she says, "I'm not familiar with human relationships, but I'm aware of the concept of jealousy" (BioWare, 2007b). At this point, Liara is more concerned with the potential interpersonal conflict than a particular relationship model. Her openness toward alternative relationship models is underlined by the result of Shepard's attempt to continue romancing both characters by smirking and saying, rather opaquely, "Why do I have to make a choice? Maybe the three of us could, uh..."; the human crewmember will always cut Shepard off at that point in the dialogue to end the relationship and Liara will always remain romanced (see Video 1). This indicates that Liara is the only romantic interest not upset by this dialogue choice. The reaction differs between the two human crewmembers, however: while Kaiden politely, if stiffly, refuses, Ashley will respond disdainfully, saying "In your dreams, Commander. I hope you two—or however many you end up with—will be happy together" (BioWare, 2007b). The severity of each response fits the character's personality: interestingly, Ashley's xenophobia (and subsequent dislike of Liara) is placed in close proximity to her slut-shaming comments. However, even the more tolerant Kaiden also responds negatively, placing Shepard's suggestion, along with Liara's openness, beyond the outer limits of the acceptable in the game. The possibility of simultaneous pursuit of multiple partners is raised specifically in order to be rejected.

Video 1. Threesome confrontation cutscene from Mass Effect, 2007 with male Shepard. Video source: CmdrPwn. (2012, January 23). Mass Effect - trying to choose both Liara and Ashley. YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c06ow9Qe5b8.

Liara's implication that she herself does not feel jealousy, along with her willingness to remain in a relationship with Shepard after the suggestion that gives this paper its title, suggests that the game endorses the assumption that a lack of jealousy is needed for partners to be interested in non-monogamous relationships. This mononormative perspective flies in the face of most of the literature surrounding how to pursue consensual non-monogamy, perhaps the most popularly known of which is Hardy and Easton's The Ethical Slut (2009). Guides like The Ethical Slut often focus on proactive strategies for addressing jealousy within non-monogamous relationships. This literature takes as a given that jealousy is a natural response that partners should discuss. In Mass Effect, however, Liara's implied lack of jealousy is hinted to be a sign of her immaturity in relationships. As she matures, she becomes more possessive. If she is romanced in Mass Effect and Shepard pursues another love interest in Mass Effect 2 (BioWare, 2010a), and the player-character then meets with Liara in the Lair of the Shadowbroker DLC (BioWare, 2010b), she will express sharp jealousy. Though Liara is still relatively young for a member of her race, the Liara met with here is an older, more experienced character, who has pursued her first relationship (with Shepard) at this point. Her anger and jealousy contrast with her relative calmness in the confrontation scene in the first Mass Effect. Her increased experience and maturity (particularly from the traumatic experience of thinking Shepard was dead) seem to have increased her capacity for jealousy. This pairing of maturity and the capacity for jealousy suggests that the younger Liara's lack of jealousy was a result of her inexperience in relationships. As noted by Deri, the privileging of jealousy as a sign of love suggests that "real" love is incompatible with consensual non-monogamy (2015, p. 1). After the confrontation, the player can reconcile with Liara, but doing so ends the other relationship. Again, Shepard is not given the chance to enter into consensual non-monogamy: the relationship with another character in Mass Effect 2 is treated as an affair.

Fundamentally, all of the relationships in Mass Effect 2 are adulterous if a save from Mass Effect in which Shepard romanced Ashley, Kaiden, or Liara is carried over into the second game. If Shepard pursues any relationships, they take place without the consent of Shepard's partner from the first game, making the adultery a singular line of progression while the other romance is effectively on hold. Despite the partner's absence for substantial sections of the game, there remains an ethical responsibility to remain "true" to that partner. The game visualizes this context through the use of a picture of the previous love interest in Shepard's quarters. If Shepard remains celibate, thus remaining "loyal" to the original interest, the picture remains on the desk. If Shepard pursues another interest, the picture frame will be turned over. This visualization of Shepard's romantic situation through the picture being turned over (rather than simply removed) seems to indicate that if Shepard pursues another relationship, they have rejected the first one and may even feel shame for doing so—if the player assumes it was Shepard who turned the picture over. The game element of the picture reinforces that Shepard's choice to pursue a relationship in Mass Effect 2 is, with respect to the narrative, a rejection of the old one, rather than a celebration of the new. Again, the ability to negotiate choices with Shepard's first partner is not coded into the game mechanics, making Shepard choose between monogamy or cheating with no potential ludic alternatives.

In the third installment of the series, Shepard can reconnect with a previous partner or find a new one, but can still pursue only one serious relationship at a time. Much like in Mass Effect 2, Shepard is barred from pursuing a "locked-in" romance with one character until ending any other relationships and is told to do so by potential interests. Romance is strictly "one-per-customer," as it has been throughout the series. This idiom is appropriate particularly because the Mass Effect series is a product and the player is a consumer of both its games and its underlying ideologies and definitions of relationships. Ultimately, what the players buys from BioWare here is a slightly wider scope of relationship models than the one offered by the princess-rescue narrative, but nevertheless one with a mononormative core. Relationships in Mass Effect are serially monogamous and the only alternatives to this framework are framed as acts of cheating and rule-breaking which are called out by the game's characters and corrected by its mechanics.

The Witcher: Sex and Sorceresses

At first glance, CD Projekt RED's The Witcher series appears much more open-minded towards consensual non-monogamy than most games, the Mass Effect series included. In all three games in the series, protagonist player-character Geralt has multiple potential sexual partners in a variety of situations. The series' association with available sexual content extends to the point that mainstream games publications such as Kotaku featured articles like "Every Sex Scene in The Witcher 3" (2015). Despite this openness toward sexual non-monogamy, the series rests firmly on the side of romantic monogamy. While Geralt is free to pursue multiple sexual partners, efforts to pursue serious romantic relationships must be aimed at one potential partner.

In the first game in the series, The Witcher (CD Projekt RED, 2007), the player can actually collect cards to commemorate each of Geralt's sexual conquests. Framing Geralt's sexual activity as an effort to collect each woman's card makes the pursuit of sex in The Witcher a completionist effort. But as noted in "Binders Full of Women: Collecting all the Ladycards in The Witcher - Part Six" (2014a), designer efforts to wring further replayability out of this mechanic mean that only one of a pair of cards can be collected per play-through. Geralt can collect a card for both of the game's chief romantic interests, the sorceress Triss and the medic Shani. However, only one of these two characters can be Geralt's chosen romantic interest, and feature on a second card. Three other cards are mutually exclusive depending on political maneuvering ("Binders," 2014b). Rather than exhibiting a kind of sexual anarchy, Geralt's conquests are carefully parcelled out for replay value; the lines they follow may be multiple but they are relentlessly straight, broken rather than bent at key, mutually exclusive points of decision. Similarly, the paths his romantic attentions can pursue are controlled by his child-rearing decisions: his decisions as the surrogate father of the child Alvin will please one woman and displease the other, orienting him towards one partner and alienating him from the second. This zero-sum game reinforces the game's heteronormative characterization of love as heterosexual, monogamous, and aimed at producing a family unit (in contrast to Geralt's sterility, which makes any sexual activity completely divorced from procreation). Sundén writes of queer spatiality that "[n]ew lines of direction are formed when bodies make contact with objects that are not supposed be there—such as (other) queer bodies" (2012, p. 173). In The Witcher series, the player cannot make this fruitful transgression into queer discovery. At one level, this inability is a result of the designed nature of the game-world, but at another, the game's array of sexual partners acts as a kind of buffer against queer possibility.

This juxtaposition of sexual abundance and romantic scarcity, characterized by a relentless heterosexuality on Geralt's part, continues throughout the series: the game echoes the sentiments expressed by and for Triss in The Witcher and The Witcher 2: Assassins of Kings (CD Projekt RED, 2012). In the first game, Triss tells Geralt that she does not care who he sleeps with, but Geralt has a clear choice to make between pursuing her or rival Shani romantically. In the second game, the end-game narration by minstrel character Dandelion regarding Triss always includes the sentence, "The sorceress's greatest desire was to be the only woman in Geralt's life, and to forget about all the troubles and dangers they had recently experienced" (CD Projekt RED, 2012). Despite Triss's substantial abilities and accomplishments, a relationship—or at least romantic monogamy—with Geralt remains her "greatest desire." Dandelion's phrasing does not necessarily indicate that Triss desires sexual monogamy from Geralt, but she clearly desires to be his only romantic partner. Read alongside Triss's disinterest in Geralt's sexual activity outside their relationship in The Witcher, this narration seems to indicate that according to the mores of the game, and despite some casual sexual departures from mononormativity, romantic monogamy remains normative.

This standard is further reinforced in The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt (CD Projekt RED, 2015). Though Geralt once again has a range of potential sexual partners, he has two primary romantic options: the perennial candidate Triss or Yennefer, a sorceress Geralt loved prior to his bout of amnesia at the beginning of the first game. Geralt can have casual sex with a number of potential partners, but he is clearly punished if he attempts to seriously romance both Triss and Yennefer.

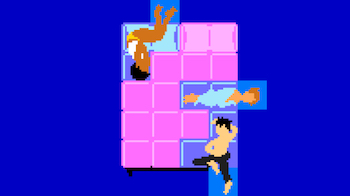

If Geralt pursues both women, Triss and Yennefer will eventually suggest a ménage-à-trois: Triss says "We've always loved each other, you're in love with us" and Yennefer responds "There's no point in fighting it. We must enjoy what we have." They strongly imply that they are putting aside their romantic rivalry in the interest of sexual pleasure and their shared interest in him—but the offer is a trap. If Geralt accepts their invitation, he is cuffed to the bed and left there while Triss and Yennefer toast each other with wine (see Figure 3). When Geralt, still deceived, asks, "What about me? Don't I get any?" they respond, "You just got exactly what you deserved." Both women leave the room and Geralt spends the night shackled to the bed. He is eventually discovered by narrator Dandelion, to whom Geralt can echo Yennefer's sentiments, saying "Got what I deserved. Should have known it was too good to be true." Yennefer and Geralt's converging sentiments seem to indicate that the possibility of getting to romantically and sexually pursue both women is foolish, selfish, or both and that Geralt's treatment is a just punishment for his transgression. Dandelion confirms this, saying "You certainly should have. Oh, Geralt... how little you know about women. Did you really think you could have them both?" In line with previous observations (Rambukkana, 2015b, p. 77) that representations of non-monogamy often centre the man's role in more complicated relationship forms regardless of other possible dynamics, Dandelion's phrasing quashes the possibility that Yennefer and Triss might engage in a threesome with Geralt and each other for their own satisfaction—hinted at by their oddly off-screen kiss before they abandon Geralt. Dandelion, backed by his authority as series narrator, posits Triss and Yennefer's offer not as a potential mutually satisfying sexual experience or romantic triad, but rather as a foolish dream of male access to multiple female romantic partners, in addition to the sexual abundance he has enjoyed throughout the series. This puts Geralt in the role of foolish, rapacious male, unable to appreciate the difference between what is sexually permissible and what is romantically possible. The player has similarly misunderstood the rules in this case and the scene is a kind of anti-achievement, punishing the player for attempting to transgress the rules by loving more than one interest. Triss and Yennefer are framed as scheming women whose pleasure and sexual agency are much less relevant than their shared anger at Geralt. Ultimately, if Geralt follows through with this quest, he loses both romantic interests and ends up alone.

Figure 3. Geralt tied to the bed during the ill-fated ménage-à-trois with Triss and Yennefer in The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt (CD Projekt RED, 2015)

The Witcher series is more sexually open-minded, but simultaneously even less forgiving of romantic philandering than Mass Effect. Unlike Mass Effect, The Witcher's third installment allows the player-character to completely follow through the "error" of attempting to circumvent in-game romantic norms, leading to a significant punishment. While Shepard can offend former partners and damage friendships beyond repair, the player-character is not immediately rendered alone by these choices. Despite sharp differences in their treatment of sexuality, both games reinforce romantic monogamy as a standard which either simply cannot be deviated from at all (as in the first Mass Effect) or from which one deviates at their peril (as in later installments of both Mass Effect and The Witcher). The greater each game's capacity for transgressive play, the greater the punishment for attempting to pursue it. This raises the question of whether the truly transgressive play described by Sundén—or as she terms it, "queer play" (2012, p. 172)—which exists typically in a player-to-player context, is possible in a single-player context. For Sundén, "[q]ueer play is a symbolic act of rebellion, of disobedience, of deviance from dominating ways of inscribing 'the player'" (p. 188), but might not meet its full disruptive potential if if remains solely in the realm of tactical transgression rather than strategic transformation (p. 89). Since in these games both the transgression and punishment are enacted according to the games' scripts, rules, code, perhaps the "cheat" involved is not the player, but the game.

Some Open Conclusions

In the case of pre-rendered romantic relationships in mainstream adventure role-playing games, monogamy remains the normative standard in both the space opera of Mass Effect and the gritty fantasy of The Witcher. Romance has one primary rule-set and neither series offers much capacity for romantic partners to creatively engage with, or renegotiate, the rules of their relationships—as has become a mainstay of open non-monogamies (e.g., see Barker, 2018; Harviainen & Frank, 2018; Hardy & Easton, 2009). Because of the designed nature of romantic content in single-player games, decisions about what to include/exclude are hugely influential. By excluding relationship negotiation and representations of consensual romantic non-monogamy, both series (arguably, as in mainstream gaming broadly) erase the reality of non-monogamous lived experiences, but moreover and for all foreshorten the role of personal agency in structuring relationships. These narratives force players to be either monogamous, cheaters, or creeps because they deny them alternative choices.

An additional aspect to consider is the role of the player as consumer: excluding non-monogamy may build replay value for these games; for example, the player can pursue Triss in one play-through of The Witcher 3 and Yennefer in another. However, being more inclusive of relationship negotiation and non-monogamy may actually increase the potential variability (and replayability) of play-throughs. Fallout 4 (Bethesda Game Studios, 2015), for example, while falling short of including realistic polyamory dynamics in its romance options, has been praised for its more open relationship structure, where non-judgmental multiple partnerships are possible (Cross, 2015). Katherine Cross notes that while some commenters see these kinds of laissez-faire relationship options as "excis[ing] crucial conflicts and challenges" from games, making them "too easy and robbed... of frisson," designers could draw from polyamorous narratives to imbue future games with both more realistic non-monogamy narratives and diverse, realistic forms of resulting conflict and drama:

As any of us who are actually polyamorous know, you do not need the confines of monogamous fidelity in order to have conflict, passion, or drama. But it is up to game designers to truly prove people like this wrong. Bringing in polyamory means more than giving into the facile assumption that it merely means to sleep around willy nilly (never has that silly term been more apt). Bethesda did a good job by allowing romantic devotion as well as merely lust [in Fallout 4], of course; you can fall in love with multiple partners in-game. But there's ample room to grow from this rich seedbed. (Cross, 2015)

To do so could tap the transgressive energy of non-monogamy, its off-book, off-script approach to romance, to at-least trouble—and possibly queer—the mononormative standard romance script. Such radical energy could go beyond Aarseth's "wondrous acts of transgression" (2007, p. 133) in which moments that escape "the prison house of regulated play" (p. 133) are significant but singular moments, to come more in line with Flanagan's (2009) notion of "critical play," in which "games designed for artistic, political, and social critique or intervention" can give us new ways to understand both cultural issues and games simultaneously (p. 2). While non-monogamy might or might not (depending on one's perspective) be considered a queer practice (Mint, 2007), the active and nuanced exploration of non-monogamy in games holds a lot of potential for Sunden's (2012) "queer play." But in large, mainstream games, that remains a distant horizon.

Figure 4. Anna Anthropy and Leon Arnott's Triad (2013). Image from Brice, M. (2014, August 19). Triad. Mattie Brice: Alternate Ending [blog post]. Retrieved from https://i0.wp.com/www.mattiebrice.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/triad.png?fit=770%2C433&w=640.

While representation is growing, as this paper explores it seems to still be largely along normative lines. The magic circle of games' encoded rules and narratives (Huizinga, 1950, p. 10) remains also a charmed and at-times exclusive one (Shaw, 2015) that privileges monogamy—at least with respect to romance. And while games with alternative formulations and narratives do exist, they either still have a distance to go in representing the complexity of consensual non-monogamy, or dwell on the fringes of videogame culture in the work of independent and alternative game designers—for example Anna Anthropy and Leon Arnott's Triad (2013) (see Figure 4). Further work could fruitfully examine such games in which queer play with monogamy is the rule rather than the exception, as well as how the uneven possibility for active, open, and intentional non-monogamies are received among actual as opposed to the implied players of games (Aarseth, 2007), as well as how such might surface in multiplayer game spaces. But just as mainstream television and film have begun to bridge the gap between extant non-monogamous realities and the types of narratives we see in the mainstream as writers become more diverse and/or draw their stories and inspirations from a broader pool of cultural material, we are likely to see further complexity work its way into mainstream scripted videogame narratives. Until then, however, non-monogamy will likely continue to be rendered as an attempt to cheat the code.

Endnotes

[1]Open non-monogamies are ones where the non-monogamous nature of the relationship is known to all parties, while in closed non-monogamies this knowledge is not shared by all parties (for example, cheating). Polyamory is one of the most popular subcultures of open non-monogamy, and can be understood as an orientation in which partners of all genders consent to and are free to pursue additional sexual or romantic relationships (Hardy & Easton, 2009). In this article, when we refer to non-monogamy we mean open non-monogamy broadly rather that closed or more rarefied forms such as polyamory unless otherwise noted. For more on open non-monogamies see Rambukkana (2015a).

[2]While by definition "polygamy" denotes being multiply married, regardless of gender, historically it has come to connote polygyny, or one man being married to multiple women. We therefore refer to this as "conventional polygamy" (Rambukkana, 2015b).

[3]There is, however, some promising work in game studies broadly. For example, Harviainen and Frank (2018) discuss group sex as play, and the important function of subcultural rules and their role in safely transgressing normative boundaries in RL open non-monogamous sexual spaces.

[4]This argument for an increasing crossdiciplinary richness in studying non-monogamy in games is similar to (and, some might argue an extension of) Adrienne Shaw's argument that game studies could benefit from an increasing attention to queerness in games and, simultaneously, that queer studies broadly should take games seriously as cultural artifacts (2015). While non-monogamous arrangements do not necessarily comprise same-sex arrangements, the overlap of LGBQT* and non-monogamous subcultures is substantial and, moreover, some even consider non-monogamy iself to be a form of "queered" sexuality, in that it troubles and potentially disrupts normative sexuality—though there is much debate surrounding this issue (e.g., see Mint, 2007). Indeed, some even see more specific forms of non-monogamy such as polyamory as sexual orientations (Tweedy, 2010). As Shaw notes though, as important as studying queer representations in games is, it is in queering games and game studies broadly where we might find the most fruitful engagements (2015, p. 65, 74), and studying how monogamous relationship options are often the default is a strand of this work.

[5]While most of the games we focus on can be considered triple-A, as a puzzle platformer, Catherine might not typically be considered in this category. While our object focus is large-studio, fairly mainstream games, the understood borders and boundaries of triple-A as a designation are not particularly germane to our argument.

[6]While Rubin's work is both classic and useful, as Ho (2006, p. 548) points out in her discussion of non-monogamous or polyamorous individuals in Hong Kong, it needs to be complicated with an intersectional lens. In particular, Ho notes that race, class, and gender are key co-determinants for gauging a person's place within social and sexual hierarchies, and that monogamous or non-monogamous partnering alone is insufficient to ascertain if someone is within a "charmed circle" or not—and in fact a person might be multiply within and without a normative range on different axes of privilege/oppression (p. 548). Elsewhere one of us has discussed this resulting positioning in terms of an emergent "intimate privilege" (Rambukkana, 2015b) that must be considered more broadly than just with respect to "mononormativity" alone.

[7]"Mononormativity" is based on the pattern of "heteronormativity" and refers to the undue privileging of monogamy in society. For a detailed unpacking of this concept, see Kean (2015).

[8]While programmed by a different team, Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards (Sierra, 1987) "is, almost puzzle for puzzle Softporn [Adventure]" (Nooney, 2014).

[9]This paper does not address the newest installment, Mass Effect: Andromeda (BioWare, 2017).

Abbreviations

LGBQT* – Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Queer, Trans*

NPC – Non-player character

RL – Real life

RPG – Role-playing game

References

Aarseth, E. (2007). I fought the law: Transgressive play and the implied player. Proceedings of the 2007 Digital Games Research Association International Conference: Situated Play, 4, 130–133. Retrieved from http://www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/07313.03489.pdf

Adams, M. B. (2015). Renegade sex: Compulsory sexuality and charmed magic circles in the Mass Effect series. Loading..., 9(14), 40–54.

Ahmed, S. (2004). The cultural politics of emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP.

Ahmed, S. (2006). Queer phenomenology: Objects, orientations, others. Durham: Duke UP.

Alter, A. (2007, August 10). Is this man cheating on his wife? Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB118670164592393622

Barker, M.-J. (2018). Rewriting the rules: An anti self-help guide to love, sex and relationships (2nd Ed.). New York: Routledge.

Barker, M., & Langdridge, D. (Eds.). (2010). Understanding non-monogamies. New York: Routledge.

Bati, U., & Atici, B. (2011). Online polygamy or virtual bride: Cyber-etnographic research [sic]. Social Science Computer Review, 29(4), 499–507.

Binders full of women: Collecting all the ladycards in The Witcher - part six. (2014a, September 11). Falling awkwardly [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://fallingawkwardly.wordpress.com/2014/09/11/binders-full-of-women-collecting-all-the-ladycards-in-the-witcher-part-6/

Binders full of women: Collecting all the ladycards in The Witcher - part eight. (2014b, September 17). Falling awkwardly [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://fallingawkwardly.wordpress.com/2014/09/17/binders-full-of-women-collecting-all-the-ladycards-in-the-witcher-part-8/

Brady, S. S., Iantaffi, A., Galos, D. L., Rosser, B. R. S. (2013, September). Open, closed, or in between: Relationship configuration and condom use among men who use the internet to seek sex with men. AIDS Behav, 17, 1499–1514. DOI: 10.1007/s10461-012-0316-9

Brody, J. (Producer), & Taylor-Johnson, S. (Director). (2015). Fifty shades of grey [Motion picture]. USA: Focus.

Consalvo, M. (2007). Cheating: Gaining advantage in video games. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Consalvo, M. (2003). Hot dates and fairy tale romances: Studying sexuality in games. In M. Wolf & B. Perron (Eds.), The video game theory reader (pp. 171–195). New York: Routledge.

Cross, K. (2015, December 7). What Fallout 4 does with polyamory is just the beginning. Gamasutra: The Art & Business of Making Games. Retrieved from http://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/261034/What_Fallout_4_does_ with_polyamory_is_just_the_beginning.php

Deri, J. (2015). Love's refraction: Jealousy and compersion in queer women's polyamorous relationships. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Eroge. (2017, June 25). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 13:42, June 29, 2017, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Eroge&oldid=787397018

Flanagan, M. (2009). Critical play: Radical game design. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Fox News. (2008) Fox News Mass Effect sex debate. YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PKzF173GqTU

Foucault, M. (1986). Of other spaces (J. Miskowiec, Trans.). Diacritics, 16(1), 22–27.

Galbraith, P. W. (2011). Bishōjo games: 'Techno-intimacy' and the virtually human in Japan. Game Studies, 11(2). Retrieved from http://gamestudies.org/1102/articles/galbraith

Glassie, S. "Embraced eternity lately?": Mislabeling and subversion of sexuality labels through the Asari in Mass Effect. In M. Wysocki and E. W. Lauteria (Eds.), Rated m for mature: Sex and sexuality in video games (pp. 161–173). New York: Bloomsbury.

Gregg, M. (2013). Spouse-busting: Intimacy, adultery, and surveillance technology. Surveillance & Society, 11(3), 301–310.

Grindr LLC. (2009). Grindr [Application].

Hardy, J., & Easton, D. (2009). The ethical slut: A practical guide to polyamory, open relationships, and other adventures (2nd ed.). Berkeley, CA: Celestial Arts.

Harviainen, J. T, & Frank, K. (2018). Group sex as play: Rules and transgression in shared non-monogamy. Games and Culture, 13(3), 220–239.

Hart, C. (2015). Sexual favors: Using casual sex as currency within video games. In M. Wysocki and E. W. Lauteria (Eds.), Rated m for mature: Sex and sexuality in video games (pp. 147–160). New York: Bloomsbury.

Hartley, M. (2009, January 3). The age of avatars. Globe and Mail, pp. A10.

Ho, P. S. Y. (2006). The (charmed) circle game: Reflections on sexual hierarchy through multiple sexual relationships. Sexualities, 9(5), 547–564.

Huizinga, J. (2014). Homo ludens: A study of the play-element in culture. Mansfield Centre, CT: Martino Publishing. (Original work published 1950)

Kean, J. (2015). A stunning plurality: Unravelling hetero- and mononormativities through HBO's Big Love. Sexualities, 18(5-6), 698–713.

Klesse, C. (2006). Polyamory and its 'Others': Contesting the terms of non-monogamy. Sexualities, 9(5), 565–583.

Kreston, B. (2014). Refusing a spoiled identity: How the swinger community represents on the web [Doctoral dissertation]. Retrieved from ProQuest (3581673).

Loving More. (1994). Retrieved from http://www.lovemore.com/magazine/

McCullough, K. (2008, January 13). The sex-box race for president. Free Republic. Retrieved from http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/news/1952968/posts

M2 Presswire. (2014, July 11). Married but Lonely launched to provide online guide for those looking for an affair. Retrieved from https://www.m2.com/m2/web/story.php/20143983928

Mehra, A. (2014, February 20). Social media, anonymity on the web help married have a fling. The Economic Times [New Delhi]. Retrieved from http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2014-02-19/news/47490036_1_social-media-infidelity-10-cases

Mint, P. (2007, March 13). Polyamory is not necessarily queer [Weblog post]. Retrieved from https://freaksexual.com/2007/03/13/polyamory-is-not-necessarily-queer/

Minx, C. (1999). Polyamory Weekly [Podcast]. http://polyweekly.com/

Nooney, L. (2014, December 2). The odd history of the first erotic computer game. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2014/12/the-odd-history-of-the-first-erotic-computer-game/383114/

Piela, A. (2012). Muslim women online: Faith and identity in virtual space. New York: Routledge.

PR Newswire. (2011, August 4). CheaterVille.com new subscribers top 100,000!: CheaterVille adds 100,000 new users within 6 months of initial launch. Retrieved from http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/cheatervillecom-new-subscribers-top-100000-126759418.html

Race, K. (2015). Speculative pragmatism and intimate arrangements: Online hook-up devices in gay life. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 17(4), 496–511.

Rambukkana, N. (2015a). Open non-monogamies. In C. Richards & M. J. Barker (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of the psychology of sexuality and gender (pp. 236–260). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rambukkana, N. (2015b). Fraught intimacies: Non/monogamy in the public sphere. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

Rambukkana, N. (2007). Taking the leather out of leathersex: The internet, identity, and the sadomasochistic public sphere. In K. O'Riordan & D. Phillips (Eds.), Queer online: Media technology and sexuality (pp. 67–80). New York: Peter Lang.

Sarkeesian, A. (2013). Damsel in distress: Part 1 – Tropes vs. women in video games. YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X6p5AZp7r_Q

Shaw, A. (2015). Circles, charmed and magic: Queering game studies. QED: A Journal in GLBTQ Worldmaking, 2(2), 64–97.

Shaw, A. (2013, October 16). The lost queer potential of Fable. Culture Digitally [Blog]. Retrieved from http://culturedigitally.org/2013/10/the-lost-queer-potential-of-fable/

Sundén, J. (2012). A queer eye on transgressive play. In J. Sundén and M. Sveningsson (Eds.), Gender and sexuality in online game cultures: Passionate play (pp. 171–190). New York: Routledge.

Sweet-McFarling, K. (2014). Polygamy on the web: An online community for an unconventional practice [Doctoral dissertation]. Retrieved from ProQuest (1564522).

Tinder Inc. (2012). Tinder [Application].

Tweedy, A. E. (2010). Polyamory as a sexual orientation. University of Cincinnati Law Review, 79, 1461, 2011.

Youngblood, J. (2015). Climbing the heterosexual maze: Catherine and queering spatiality in gaming. In M. Wysocki and E. W. Lauteria (Eds.), Rated m for mature: Sex and sexuality in video games (pp. 240–252). New York: Bloomsbury.

Ludography

Anthropy, A., and Arnott, L. (2013). Triad [PC]. Retrieved from http://auntiepixelante.com/triad/

Atlus. (2011). Catherine [PS3]. Tokyo, Japan: Atlus USA.

Bethesda Game Studios. (2015). Fallout IV [XBox One]. Rockville, USA: Bethesda Softworks.

BioWare. (2017). Mass Effect: Andromeda [Xbox One]. Redwood City, USA: Electronic Arts.

BioWare. (2012). Mass Effect 3 [Xbox 360]. Redwood City, USA: Electronic Arts.

BioWare. (2010a). Mass Effect 2 [Xbox 360]. Redwood City, USA: Electronic Arts.

BioWare. (2010b). Mass Effect 2: Lair of the Shadow Broker [Xbox 360]. Redwood City, USA: Electronic Arts.

BioWare. (2009). Dragon Age: Origins [Xbox 360]. Redwood City, USA: Electronic Arts.

BioWare. (2007a). Jade Empire [Xbox 360]. Redwood City, USA: Microsoft Game Studios.

BioWare. (2007b). Mass Effect [Xbox 360]. Redmond, USA: Microsoft Game Studios.

Blizzard. (2004). World of Warcraft [PC]. Irvine, USA.

Blue Sky Software. (1981). Softporn Adventure [Apple II]. Los Angeles, USA: On-Line Systems.

CD Projekt RED. (2007). The Witcher [PC]. Paris, France: Atari.

CD Projekt RED. (2012). The Witcher 2: Assassins of Kings [Xbox 360]. Paris, France: Atari.

CD Projekt RED. (2015). The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt [Xbox 360]. Paris, France: Atari.

Linden Labs. (2003) Second Life [PC]. Retrieved from http://secondlife.com

Lionhead Studios. (2010). Fable 3 [Xbox 360]. Redmond, USA: Microsoft Game Studios.

Lionhead Studios. (2008). Fable 2 [Xbox 360]. Redmond, USA: Microsoft Game Studios.

Lionhead Studios. (2004). Fable [Xbox]. Redmond, USA: Microsoft Game Studios.

Love, C. (2016). Ladykiller in a Bind [PC]. Toronto, Canada: Love Conquers All Games.

Nintendo. (1981). Donkey Kong [Arcade]. Tokyo, Japan: Nintendo.

Sierra. (1987). Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards [MS-DOS]. Oakhurst, USA: Sierra.