Same but Different: A Comparative Content Analysis of Trolling in Russian and Brazilian Gaming Imageboards

by Ahmed Elmezeny, Jeffrey Wimmer, Manoella Oliveira dos Santos, Ekaterina Orlova, Irina Tribusean, Anna AntonovaAbstract

In this study we explore how perceived out-of-game trolling differs within online gaming imageboards in Brazil and Russia. The two samples consist of 1443 posts from two Brazilians message boards (/jo/ and /lan) on 55chan and 1439 posts from the /v/ message board on the Russian 2ch. Both imageboards are local adaptations of 4chan. We analyzed the material from a comparative transcultural perspective. For the content analysis of message boards, we utilized a codebook based on trolling strategies developed by Hardaker (2013), which we supplemented with inductive categories derived during the coding process. Our research shows that there are similarities in the methods of trolling in Brazil and Russian imageboards, as well as in the topics which trigger attacks. Our findings suggest that trolling in both communities does not differ much and tends to be more homogeneous; adhering to a seemingly transcultural standard.

Keywords: 4chan, antisocial behavior, game culture, online gaming community, transcultural communication, trolling strategies

Introduction

Digital gaming is no longer considered an activity geared for children and young adults. According to the data provided in a commercial study by Newzoo (2016), as of June 2016 there were approximately 1.9 billion video gamers worldwide, constituting more than 26% of the overall world's population. The vast majority of digital games today are played online: in 2013, it was reported that 72% of US gamers played online (NPD Group). Looking at the world's population as a whole, according to a report by the online games developer and publisher Spil Games (Driessen & Diele, 2013, p. 4), 44% of the world's Internet population is playing online games. While these commercial reports should always be taken with a grain of salt, the number of reported online gamers indicates them as a major part of the internet community.

Another increasing feature of the online environment, for both gamers and non-gamers, is trolling. Bargh, et. al (2002, p. 34) claim that "anonymity on the Internet enables people the opportunity to take on various personas," and Griffiths adds that this anonymity "facilitates disinhibition, resulting in flaming and harassment" (2014, p. 86). Jane (2014 p. 531f.) claims that a wide range of antisocial behaviors such as flaming, trolling and cyber-bullying are typical of the online world. This is especially evident in the online gaming environment, which is described by Consalvo (2005, p. 6) as a space where players "break or bend rules", and thereby, provoke trolling. In a research carried out by YouGov in 2014, 28% of Americans admitted malicious online activity directed at somebody they did not know (Gammon, 2014). Among Internet spheres where respondents saw trolling, gaming constituted 17%. Online chat rooms and forums appeared to be areas with the most frequent trolling manifestations, with a sizable 45% (Gammon, 2014). While there is plentiful research on general aggression, impoliteness and conflict online, comparative research regarding trolling and cyber-bullying is still lacking. New research on trolling usually assumes that it is a global phenomenon with no national differences (Coleman, 2014; McDonald, 2015, 973; Mäyrä, 2016, 14). Furthermore, current research attempts to explore and explain the phenomenon, not address cultural differences between trolls. Philips (2015), for example, finds that trolling behavior is driven by culturally permitted impulses, but does not address transcultural aspects. We address this gap by looking at the cultural context of trolling, through analyzing gaming imageboards from different countries utilizing different languages.

There has been extensive research conducted on international game cultures and industries, however, rarely is such research comparative (Wolf, 2015). Mäyrä (2008a) emphasizes the need for "international, academic comparative study of players and game cultures" (p. 253). He notes that "there is much room for more targeted studies that look into specific areas in detail, comparing different game cultures" (2008b: 255). Trolling is a common occurrence in gaming, however, we still do not know how this anti-social behavior differs across game genres, cultures and countries. Sometimes called 'griefing', trolling as play through annoying others, has been well documented (Bakioglu, 2009; McDonald, 2015). Still, the cultural differences between this sort of play have yet to be explored. We attempt to explore a specific aspect of game cultures (trolling) through observing how it differs in online gaming imageboards in Russia and Brazil.

Theoretical framework

Games and Transculturality

In the following paper, we present a comparative study of online trolling in two different gaming imageboards. Comparative transcultural research in media and communication has become more important due the global dimension of media itself, as aptly put by Livingstone (2003, p. 2), "in a time of globalization, one might even argue that the choice not to conduct a piece of research cross-nationally requires as much justification as the choice to conduct cross-national research". Research that compares various national game cultures is beneficial in its ability to highlight similarities and differences between two geographically distinct manifestations. Through this transcultural comparison, researchers are able to make assumptions about globalization, or a global game culture (Elmezeny & Wimmer, 2018), as well as critically compare different hierarchal articulations in these cultures (Hepp, 2015).

For our study, the concept of transcultural communication is important since we are dealing with communication from two different countries. According to Hepp (2015), looking at transcultural communication helps to analyze the mediated forms of communication and how they are connected with the metaprocesses of mediatization and globalization. The link with mediatization is that "transculturality is closely related to the way in which Internet-based media mold our communication today" (p. 4), and with globalization because "the globalization of media communication is a central element of globalization itself" (p. 5). Hepp's approach does not only compare national cultural patterns of communication, but also involves patterns that illustrate differences beyond traditional cultures. As Hepp (2015, p. 3) clarifies, developing a concept of transcultural communication involves specifying particular national cultures but also examining how these particularities are taken up in communication processes that transcend cultures. His framework serves as the starting point, since the communication process in the message boards is embedded in national cultures, while still influenced by global tendencies, topics and practices related to games; such as brand loyalty to certain game developers or consoles.

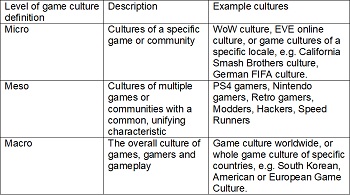

An analysis of communication from two country-specific gaming communities can shed light on the characteristics of digital game cultures and their relation to processes such as commercialization, mediatization and of course, globalization. While two small gaming communities may not be representative of the entire game culture from a specific country, defining the game culture on this micro level (see Table 1) allows us to compare two manageably sized samples and make assumptions about the larger surrounding game culture (Elmezeny & Wimmer, 2018). Additionally, it is suggested to use mediatized worlds as micro cases to study large metaprocesses like mediatization and globalization (Hepp, 2011).

Still, it is important to note that defining these gaming communities as micro game cultures does not free them from cultural overlap. We are aware that even though these nationally distinct gaming imageboards can be micro representations of a specific game culture, they still include aspects of several other cultures that revolve around a variety of games (macro game culture), as well as overlapping with an assumed meso level: online trolling culture (Elmezeny & Wimmer, 2018).

Table 1. Defining game cultures on various levels as stated in Elmezeny & Wimmer (2018)(click to expand).

Game Culture

The popularity of games is reflected clearly in academia, with a considerable amount of research conducted on the topic. As Shaw (2010, p. 403) mentions, video game culture is one of the aspects that draw the attention of researchers. At the same time, it is complicated to agree on a definition of video game culture; because culture itself is a diverse and complex concept (Shaw, 2010 p. 405). Among various definitions, games can be found as having independent cultures, separate from mainstream culture (Shaw, 2010 p. 404), or as a part of popular culture (Dovey & Kennedy, 2006, p. 2), or even as a collection of several subcultures (Mäyrä, 2008b, p. 25; Williams et al., 2006, p. 141; Crawford & Rutter, 2006).

According to Mäyrä (2008b), members of these subcultures share a common language (specific terminology), rituals, and interest for artifacts that can function as memorabilia. Overall, gamers and other participants of the game industry share a "sense of identity" that characterizes the gaming culture and creates solidarity among them (Williams et al., 2006, p. 150). It does not mean, though, that there are no conflicts or debates among gamers; "tastes and preferences vary among gamers," which can create competitive conflicts among players (Williams et al., 2006: 150). An observable side effect of these conflicts is online trolling, described more thoroughly below.

Mäyrä (2008b: 25) also mentions common space as a characteristic of game cultures. Today, most spaces shared by members of game cultures are virtual, whether in game or created by players themselves on websites or message boards. Hence, online gaming communities are one of the obvious manifestations of game culture, where gamers communicate and share similar identities or values. Bishop (2014, p.172) defines an online community as "a type of virtual community that is enabled through Internet technologies". Virtual is used by Bishop to indicate "a community where those that form part of it exist in different localities" (ibid.). This is an important consideration for our study, noting that members of our observed online communities may originate from the same country but do not necessarily physically co-exist. As observed by Taylor (2006), locality and language play an important role in online gaming communities. In her look at the World of Warcraft, she found that in addition to age, a person's national identity and language can be used to create sometime harmful social categories and stereotypes (Taylor, 2006).

Mitgutsch et. al (2012), building on Hepp (2008), explain the genesis of digital game culture using the model of du Gay et al. (1997). The articulation of game culture can be understood as a circuit and is composed of five contexts: (re)production, representation, regulation, appropriation and identification. In the study of games, context is of extreme importance and should be "foregrounded" (Taylor, 2006, p.318). For our research we are mostly concerned with the contexts of appropriation and identification. This is because our research analyzes trolling in online communities, which can be considered as appropriated behavior, or specific communication norms associated with participation in a certain game culture. Furthermore, the context of identification is considered because knowledge and adherence to these rules can signify membership within certain gamer cultures. According to Wimmer (2012, p. 529), appropriation refers to "the process of actively embracing the culture in everyday life," while identification denotes "the process of constituting identity based on communicated patterns and discourse." In digital games, these processes can be observed through in-game social norms, habits, rules and the use of specific language or actions to distinguish themselves as members of a certain community.

Trolling

The study of trolling, as a form of negative (antisocial) behavior, began in the 1980s. Due to the anonymity offered by computer-mediated communication, trolling became more common in this specific medium (Hardaker, 2013). In this paper, we refer to online trolling, which is "a specific example of deviant and antisocial online behavior" (Fichman and Sanfilippo, 2014, p. 163). It is strongly related to anonymity, a distinctive feature of the online environment as a whole, and of online communities and message boards in particular. Suler (2004, p. 322-325) elaborates on the "online disinhibition effect", which emerges as a result of online anonymity, physical invisibility and asynchronicity, or the absence of having to cope with a person's immediate reaction. This effect can be expressed both in positive and negative ways. We are primarily interested in "toxic" disinhibition, evoking usage of "rude language, harsh criticisms, anger, hatred and threats" (p. 321). Several academics have noted that this form of antisocial behavior is characteristic of gamers (Thaker & Griffiths, 2012; Downing, 2009; Anderson et al., 2012).

Hardaker (2010, 2013) and Morrissey (2010) identify various types, aspects and interpretations of trolling, resulting in diverse definitions. Still, most of these definitions generally agree that trolling is "diverting the topic of a discussion, causing it to descend into a heated argument" (Morrissey, 2010, p. 77). From a communicational perspective, trolling can be analyzed from two approaches, the intention of the troll, and the perception of trolling, which focuses on interpretation of the message. There is a fair amount of studies about intended trolling (Bishop, 2014; Morrissey, 2010; Downing, 2009; Phillips, 2015), but not that much on perceived trolling. Current research on trolling continues to study behaviors and motivations of trolling ethnographically through case studies (Fichman, Pnina and Sanfillippo, 2016). For our research, as we were interested in the perception of trolling. Hence, we have adopted Hardaker's strategies of trolling into a codebook since it provides the most inclusive spectrum of perceived trolling. Hardarker's (2013, p. 80) model for the analysis of perceived trolling includes six strategies, ranging from covert to overt antagonism:

"(1) (D)igressing from the topic at hand, especially onto sensitive topics; (2) criticizing, especially for a fault that the critic then displays herself; (3) antipathising, by taking up an alienating position, asking pseudo-naïve questions, etc.; (4) endangering others by giving dangerous advice, encouraging risky behavior, etc.; (5) shocking others by being insensitive about sensitive topics, explicit about taboo topics; (6) aggressing others by insulting, threatening, or otherwise plainly attacking them without (adequate) provocation" (ibid).

Trolling occurs very commonly on 4chan, a message board actively used by gamers. Users of 4chan can post images and textual messages on threads, and each board of the forum deals with a specific topic (e.g. /v/ is video games, /b/ is random). According to Philips (2012, p 497), all actions user can perform on the website are carried out anonymously, hence, it is "disconnected from any identity" (Bernstein et al., 2011, p. 3). On 4chan, threads appear and disappear quickly, and once gone cannot be accessed again. Even with anonymous interaction, identity plays a central role in 4chan interactions. Ludemann (2018) finds that participants on 4chan are crafting new understandings of identity, due the features of the website itself, as well as content. Moreover, Sparby (2017) notes that aggressive behaviors on these boards are reflective of a collective identity.

Manivannan's (2012) states that trolling in 4chan is "an ontological consequence of anonymity and ephemerality" (p. 8) and these exact reasons are what contribute to 4chan having its own culture, characterized as a culture of automatic dissent (Knutila, 2011, p. 8), and a culture of trolling (Nissenbaum & Shifman, 2015: p. 11). According to Philips (2012), 4chan is a pillar and epicenter of online trolling activity, making it ideal for our analysis. In order to look at trolling from a transcultural perspective, the selected online imageboards are localized versions of 4chan in Brazil and Russia.

Trolling in Brazilian and Russian Game Communities

Fragoso (2015, p. 138-140) claims that a very common approach of Brazilian trolls in games is to ridicule someone or a group of people. However, it is their peculiarity to go beyond: to represent themselves as ugly, pretend to be fools and to ridicule themselves (self-trolling). It is part of their identity to speak Portuguese where the official language is English, to bastardize foreign languages, to share memes and to annoy other players rather than getting something from them. Fragoso finds that Brazilian trolling is seen by Brazilians as funny, rather than offensive. Despite the lack of similar research on game trolling in Russia, a look at linguo-cultural peculiarities of Russian online communication by Smirnov (2005) shows that: "[D]irect insults used by participants of e-communication in Russian language are almost 1.5 times more frequent than among English-speaking communicants" (p.3). We assume that this phenomenon impacts the way users communicate in a Russian online game environment as well.

It is a common opinion that Russian gamers behave in a special way in gaming communities, e.g. are aggressive and quick to attack others; secretive and insular, speak their own language rather than English; violate, bend, or exploit the game and "generally interact in an aggressive manner" (Goodfellow, p. 349). In our research we hope to find out whether it also can be observed in out-of-game environment. Brazilian gamers, on the other hand, are known for spreading memes and annoying others through ridicule. According to Fragoso and Hackner (2014) Brazilian gamers are involved in remarkable episodes of aggressive trolling towards other nationalities, and are often spamming; labeling them as toxic gamers. They also find that Brazilian gamers speak Portuguese where the official language is English for preference, not for lack of ability. However, the actions of Russian and Brazilian trolls are still unobserved in an out-of-game environment. This is also true for gamers as a whole, even with research regarding in-game trolling (Bakioglu, 2009; Thaker & Griffiths, 2012; Kirman et al., 2012; Fragoso, 2015), there is significantly less about trolling of gamers in an out-of-game environment.

Research Questions

As the literature review shows, trolling is a form of antisocial behavior that is often seen in online platforms and popular among gamers. Trolling in out-of-game online gaming communities has not been commonly analyzed, especially in a transcultural comparative perspective.

To answer our research question, the trolling strategies system proposed by Hardaker (2013) was combined with inductively developed categories, which were created to match the reality of the national communities. As the following questions show, in order to have a detailed picture, different aspects of trolling had to be analyzed:

RQ 1: Which trolling strategies are more common and acceptable in each respective community?

Our first goal was to compare how people troll in both imageboard communities. Additionally, our intention was to understand how the community reacts to these acts of trolling. Whether some are more accepted than others, totally unacceptable, or even encouraged. Hence, we investigated acceptance, by looking at the responses to the trolling messages. After looking at manifestations of trolling and their responses, we found it interesting to consider specific situations that trigger trolling behavior, and whether there is a difference between the boards. We assume that various situations can be perceived differently in each respective community, an important consideration for transcultural communication.

RQ 2: What are the common situations that trigger trolling in each respective community?

Finally, the previous research questions combined help us in answering our overall research question:

RQ 3: How does trolling differ in Brazilian and Russian gaming chan imageboards?

Methodology

In order to investigate the perceived trolling in online gaming communities, we performed a qualitative content analysis of posts from Brazilian and Russian online chan imageboards. We opted for a qualitative approach to build on Hardaker's (2013) work, which is primarily quantitative, in hopes of providing contextual examples of trolling and a more detailed image of the phenomena. Our data was collected from the most popular chans in Brazil and Russia. In Brazil, the most popular chans are brchan and 55chan (Antonio, 2013, p. 43), we selected 55chan because it shows more activity and volume of posts dedicated to games. In Russia, we chose 2ch.hk because it is one of the most popular national imageboards (Potapova & Gordeev, 2015, p. 30). Since we are looking at gamer behavior, the analysis was conducted using the message boards dedicated to games, namely /jo/ (digital games in general) and /lan/ (online multiplayer) on 55chan, and for 2ch.hk we selected /v/ (digital games in general). These message boards are an ideal source of data since they are one of the most widely and frequently used platforms for the purpose of gamer communication outside games (Seay et al., 2004).

The posts were collected through purposive sampling. According to Krippendorf (2004, p. 119), when applying purposive or relevance sampling, researchers have to examine the text, often in several stages, and select "all textual units that contribute to answering research questions". In our case, we selected threads with provocative topics and with no less than 100 posts, as they are more likely to have manifestations of trolling. In total we chose 1443 posts from seven threads from two Brazilians imageboards (/jo/ and /lan) on 55chan and 1439 posts from six threads on the /v/ board from the Russian 2ch.

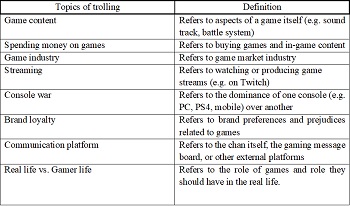

A codebook based on Mayring's (2000) qualitative content analysis approach was created in English for both samples. It was divided into four major codes according to our sub-research questions: strategies of trolling, topics of trolling, reactions to trolling and ways of posting. Our initial strategies category is based on Hardarker's (2013) six strategies mentioned before (aggress, digress, antipathize, shock, endanger and criticize). They are defined as " goal-driven behavior, and as such, this can occur over multiple posts," (p.69). Topics of trolling and reactions to trolls were categorized inductively after a pre-analysis of the data. Topics are themes of the posts that trigger trolling behavior (see Table 2). Certain posts that were sure to trigger trolling behavior, such as gender equality, did not receive their own category because they did not occur often enough in our sample and are instead subsumed in other topics. However, we do note each respective community's outlook on gender when observing sexist behavior in trolling.

Reactions were coded as acceptance (such as when user feeds the fire and adds to an obvious trolling attempt), rejection (such as reacting aggressively or disagreeing with the trolling post: taking the "bait"), ignore (when obvious trolling attempts have no post replies) or baiting (acknowledging that the behavior is obvious trolling). The following thread from the Brazilian sample displays our coding of rejection and acceptance:

Post 1: I am a successful business man and work in the IT field, more than 30 years old and I simply don't even think about the possibility of playing something that is not the best of the market for pure lack of time. And because the formulas of the games have been improving for so long instead of depending on drama made for teenagers, I have literally all Nintendo consoles except VB and PS2 that I did not sell. Where is your God now?(antipathise trolling)

Post 2: >successful business man in IT field

>"I only play the best of the market"

>lack of time

>self-affirmation on the little game table of a transvestites' forum

>I HAVE ALL THE PUPPETS (originally, he says "hominho" instead of "puppets", which is how little boys refer to their toys)

(rejection of post 1)

Post 3:

>I HAVE ALL THE PUPPETS

Laughing out loud in a rude and inelegant way

(acceptance of trolling in post 2)

As can be seen above, trolling the troll who made a specific post was considered a sign of rejection. Finally, an obvious example of ignoring a troll is when an individual attempted to start a console war in a thread discussing game news, stating "everything is consolistas' [console users] fault," and was not replied to.

Each sample was coded by either Brazilian or Russian researchers to ensure accuracy and understanding of various cultural contexts. When problems arose with game-or-meme-specific jargon, an internet search was conducted to better contextualize coding. The pretest included around 20% of the sample (314 posts from the Brazilian community and 322 from the Russian community), which was translated into English and coded by coders from each language to establish intercoder reliability and accuracy.

Strategies, reactions and topics were combined to answer RQ1, in hopes of discovering the common and acceptable methods of trolling in each community, as well as which contexts they arise. Topics codes were primarily used to answer RQ2. The answers to RQ1 and 2 assist us in answering RQ3, or how trolling differs in Brazilian and Russian chan imageboards.

Findings

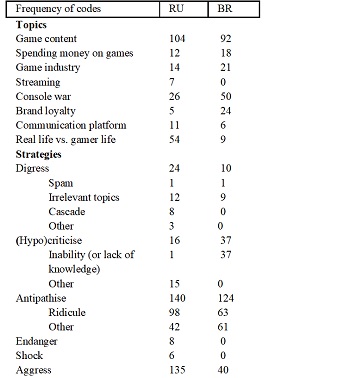

As this research is qualitative, it is important to note that the frequency of codes is not important but we still mention them to illustrate our content analysis (see Table 2).

Table 2. Frequency of coded strategies and topics in our sample (click to expand).

RQ1 - Common and Acceptable Strategies in Each Community

Overall, there was more trolling activity in the Russian than in the Brazilian community. However, in both communities the most common trolling strategy was antipathise (including the subcategory ridicule). The second most common strategy in both countries is aggress, with the difference that in Russia it is almost as popular as antipathise, while in Brazil the difference between strategies is much bigger (see Table 2). Endanger and shock strategies were not identified in the Brazilian community at all, however, in the Russian chan there is at least one occurrence of each.

Regarding the topics of trolling, game content is the most common trigger in both communities. Real life vs. gamer life is the second most popular trigger in the Russian community, but it does not get much attention in the Brazilian one. Console war, or the battle between fans of each respective console (PC, PlayStation, Xbox and Nintendo) is the second most common topic for the Brazilian community and the third in the Russian one (Table 2).

The Importance of Information: You Know Nothing, Anon

Within both imageboard communities, specific information, or feigning ignorance on certain topics was used as a strategy to troll others; triggering a response more often than not. Using the strategy of (hypo)criticize (when an induvial criticizes someone for something they are guilty of), and its sub strategy inability/lack of knowledge, to troll others was quite common in both communities. In the Russian community, trolls did not use this strategy frequently as other ones but when they did, it was usually directed at the grammar and spelling mistakes of others. For example, when one user made mistakes in spelling, he was trolled with "Go and cure your dyslexia," while others posted after him frequently misspelling the same words in the same manner. In the Brazilian chan, however, inability/lack of knowledge was frequently used to criticize others' information regarding game content and consoles. Brazilians chose to poke fun at knowledge specifically, instead of the inability of others, and usually did so in either a comedic or aggressive manner.

Trolling in this method was negatively received on the Brazilian chan, causing others to argue against the trolling comments and to take the "bait". On rare occasions, acceptance of the trolling comment occurred when another user would join the debate and agree with the troll's comment. This contrasts to responses in the Russian community, where almost all cases of (hypo)criticize were ignored. It seems that correct information is prized more in the Brazilian chan, or simply that the Russian community is wiser to this form of trolling and choose to ignore it.

Still, oddly enough, even when Russians are aware of (hypo)criticisms, they still seem to be triggered by trolling in the form of "playing dumb", or feigning ignorance. Antipathising is strategy by which users ask naïve questions or post provocative and sometimes (obviously) incorrect statements. When discussing Dark Souls 3, a highly treasured game by many for its challenging difficulty, a number of users posted trolling comments calling it a bad game, justifying their decisions through naming specific streamers who showcase it horribly. This trolling about Dark Souls 3 was negatively received, resulting in numerous reactions from the community members who took the bait. Some even responded to this trolling through aggressive trolling of their own, using foul language and threats. Even trolling approaches using antipathise that are quite obvious received a negative reaction in the Russian community. For example, regarding the topic of real life vs. gamer life, several users posted obvious trolling comments, stating things such as there being no good games left, or that gaming is a hobby for unsuccessful people (all while providing advice on how users should improve their lives). These types of posts are obvious examples of trolling since they are posted on a gaming board to trigger a reaction, and oddly enough Russian users almost always took the bait, rarely ignoring incidents and using several aggressive and argumentative responses.

Similar to Russians, Brazilians also found it hard to ignore instants of antipathise trolling. Almost all incidents triggered a response from other users but unlike Russians, Brazilians were not quick to respond negatively and instead acknowledged the instances as baiting (more frequently than any other form of trolling).

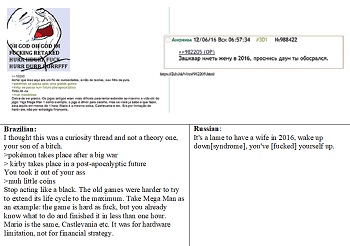

Aggression, Shock and Danger: The Darker Side of Trolling

Utilizing the trolling strategy of aggress, where users threaten, insult and attack others without any provocation is extremely common in both samples. This aggressive trolling strategy was directed at various topics and used in multiple contexts, signaling that on these imageboards, everything is fair game. On the Russian board, aggression was quite commonly used to negatively discuss gamer identity. When one user posts about how his wife is always criticizing him for playing too much, he is trolled with comments such as: "Your wife just wants to make a normal man out of you, nerd". Expectedly, aggressive comments also tend to have a sexist aspect, with multiple users trolling the original poster for being married. One troll even comments, "to get married to a Russian whore…are you stupid? They don't love anyone except alcoholics,". On the Brazilian chan, the aggressive strategy was even used to depreciate the value of the board itself, "Defenders of DLC…this /jo/ is really crap," proving that nothing is sacred, not even the community which brings all these users together.

Figure 1. Unprovoked aggression in Russian sample as opposed to aggression due to game information in Brazilian sample (click to expand).

Within the Brazilian sample, aggressive trolling was not tolerated and mostly met with levelheaded arguments, or rarely, bans for posting aggressive comments. Alternatively, on the Russian chan, these strategies were mostly ignored. So, it seems that most Russians users are wiser to this sort of trolling, or desensitized to online aggression, which is typical in their game communication (Goodfellow, 2014).

Highlighting the desensitization of Russians to darker topics and approaches, strategies such as shock and endangerment were also only observed in that sample and not the Brazilian one. Providing advice to the married gamer once again, a Russian troll utilized the endangerment strategy, giving facetious advice and stating, "Just let her go and become a prostitute…every day will become brighter". These strategies were mostly ignored by Russian users, as well as any shock strategies. Deciding on what is considered shocking is quite difficult on a chan imageboard, especially since nothing is sacred and insults are thrown around regarding everything, from parents to partners. Still, we made sure to pay attention to specific topics that would be considered taboo in Russian culture. Nevertheless, we found that even utilizing these topics was either ignored, or accepted, and exploited further by subsequent trolling commenters.

Ridiculing Others: Let Me Quote You on This.jpeg

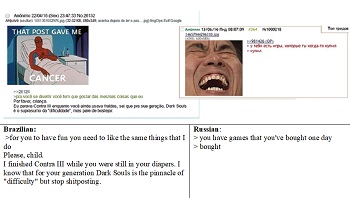

In both Russian and Brazilian communities, ridiculing others was a common trolling strategy. Using this strategy was also carried out in a similar manner in both communities, where trolls would quote portions of a previous post and ridicule them with comments or reaction images. This method of posting is very characteristic of chan imageboards and is assumed to be the reason this trolling strategy manifests in the same way in both communities; not just unique to Brazilian trolls (Fragoso, 2015).

Figure 2. Ridicule trolling posts from Brazilian and Russian samples compared (click to expand).

Other similarities in this strategy between both communities is that trolls almost always ridicule the opinions of others with which they disagree, using sarcasm, irony and overly exaggerated comments. In the Brazilian community, users were mostly ridiculed when posting opinions on specific games, brands or consoles. One user comments, "The AAA market is dead" and is immediately trolled by others posting various reaction images of laughing anime and game characters, while some even add sarcastic commentary such as "Every year more and more super productions". There were even ridicule posts trolling the trolls, with one user adding "Super productions…Every 50 AAA games we have with quality like Witcher 3". Likewise, in the Russian imageboard, opinions on specifics console choices or games are directly trolled, and PC-gamers are constantly ridiculed for their elitist attitude: "Don't ruin the fag-world of PC-boys. They still think Mario is exclusively a 2D platformer".

Surprisingly, trolling through ridiculing others was less accepted than aggressive strategies in both communities. Using a sarcastic tone and image responses usually triggered flame wars and responses from more users. This could possibly be attributed to the fact that trolling through ridiculing is more covert than outright aggression, giving users an impression that the poster is serious about what they are stating.

RQ2 - Troll Bait: Triggering Topics and Situations

In order to see which situations triggered trolling the most, we observed topics of trolling (Table 3), strategies used in these topics and community reactions.

Games and Their Content: There's No Better Game!

Given the nature of game oriented imageboards, one topic that almost always gave rise to trolling was the discussion of games content and their preferences. On the Brazilian board, and in line with their obsession of knowledge and "correct" information, several users were trolled for posting obvious facts about certain games. One such case was debating the origin of Megaman X characters, where one user jokes that they are inspired by objects in daily life (using Cutman as an example). The majority of users responded to this post with reaction images (ridicule), however, some were quick to anger (aggress) and reject the post with comments such as "you ruined the post of anon with this retardation," while others assumed that the user was a troll himself and utilizing the antipathise strategy, "people here are much too serious business to understand this kind of humor". On the other hand, Russians trolls were quickly triggered when discussing specific game preferences. The culprit which triggered the most reactions and responses was usually Dark Souls 3. Whenever any user criticized the game, a flame war began with both fans and nonfans of the game trolling each other.

Table 3. Overview of all topics of trolling categories with definitions (click to expand).

Brand Loyalty and Consoles: The Prosecution of Fanboys

As customary in other game communities, the topic of console choices was highly polarized, with an obvious opposition between PC and console gamers. On the Brazilian boards, and again customary with their information obsession, most users were usually trolled within this topic for posting incorrect information, or weak argumentation regarding console or PC hardware. One user left a long comment comparing his PS4 and Xbox which triggered a variety of trolls indicating the pointlessness of the post, "there is no difference, show the differences…I suppose you have mental problems since your denial is strong." Within the Russian community, however, individuals were trolled for their preferences, with PC gamers being labeled as too focused on graphics, "People talk about different stuff but PCfag can only talk about graphics. Go and watch walls," while console gamers were criticized for having weaker hardware and enjoying simplified games.

Oddly enough, preferences for specific consoles or hardware (brand loyalty) did not attract too much trolling on the Russian boards. In the Brazilian community, however, being loyal to a specific brand did trigger some trolling. Nintendo fans were usually the victims of these trolling attacks. Most discussion regarding Nintendo consoles or games resulted in users being trolled for their loyalty to the company and immediately labeled as "fanboys".

Conduct and Identity: You're Not One of Us!

One major topic which frequently triggered trolling was related to issues relevant to gamer identity. Various topics are included under this including, among others: spending money on games and real life vs. gamer life. On the Russian boards, a discussion of paying for early access to a game triggered a variety of trolls into calling the original poster a fool for doing so, utilizing an assortment of ridicule and aggress strategies. The use of in-game microtransactions was also a trigger in both communities, with those who use them being stripped of their gamer identity and labeled non-gamers. The issue of gamer identity triggered various other instances of trolling on the Russian boards, where individuals who posted regarding not having enough time to play labeled as "casual gamers," something seen as extremely negative within this community. Oddly enough, those who play too much were also trolled and labeled as "underage", with no other responsibilities.

Finally, while not dealing with gamer identity itself, certain conduct which is deemed not suitable for these game imageboards was also frequently trolled. For example, in both communities, any discussion of gender equality was immediately trolled using aggress strategies. Additionally, even when used to intentionally troll, atypical communication for gamers, such as the overuse of emojis, drove Russian members to aggress trolling, "don't drive me crazy, smileywhore".

RQ3 - Same but Different: Two Communities Compared

The aim of this research was to compare the perceived trolling in online gaming imageboards in Russia and Brazil, analyzing the strategies of trolling, the reaction of the community and the situation which triggered trolling attacks. Observing things from a transcultural perspective (Hepp, 2015) proves interesting as it makes to possible to note and analyze not only national differences, but also transcultural commonalities. However, we only use these imageboard communities as a micro representation of their respective national game cultures (Elmezeny and Wimmer, 2018), allowing us to make some assumptions regarding overall differences.

Some similarities in trolling strategies can be attributed to the platform itself, such as quoting the previous comment in order to ridicule someone, which is quite common in imageboard conduct (Ludemann, 2018). Reponses to certain attacks were also similar in both communities and can be attributed to more than just the platform itself. Within both nationally appropriated boards, trolling using the ridicule strategy was intolerable, almost always instigating a response. While humor is a mostly positive phenomenon, and in online environment it even has a "community-building" function that "shapes and structures the interactions in the online community" (Marone, 20015, 65), instances of humor observed were mostly negative in both gaming imageboards.

Another commonality between both communities is the prevalence of aggress trolling. This confirms previous research that indicates that trolling is associated with aggression (Hardaker, 2010, p. 232). Personal insults and abusive language are some examples of aggression in both Brazilian and Russian online communities. However, aggression did manifest differently and with varying frequencies in each respective community. It was much more common to observe aggress strategies in the Russian boards, supporting findings of Goodfellow's (2014), who states that Russian EVE Online players have "principal archetypes" of behavior: being aggressive and quick to attack (p. 344). Additionally, in line with Potapova and Gordeev's research (2015, p. 35), other than preferences for games, that aggression was directed towards users' age, sexual orientation, state of mind, nationality, political affiliation or socioeconomic class. Our findings add to both these previous studies, noting that this aggression also manifests in an out-of-game but still game-centric environment. These instances of aggress trolling were mostly ignored on the Russian chan, while in the Brazilian counterpart, it caused argumentation and even bans for instigating aggression. It is important to mention that reactions to trolling in both samples seem to depend on personal preferences. For example, when dealing with console wars, gamers with the same console preference usually support each other's trolling.

Some trigger topics were common between both communities, such as discussing console preferences, loyalty to certain brands, or microtransactions, but the situations which lead to being trolled differed. Overall, trolling in the Brazilian chan was triggered by misinformed posts or weak argumentation: even when stating your opinion, it needs to be based in fact or logic. In the Russian sample, however, trolling was triggered simply due to having different opinions, highlighting somewhat of a hivemind, and that having unconventional preferences makes you bait for trolls.

Conclusion

Our research attempts to address gaps in current research regarding the transcultural comparison of both game communities and trolling behavior. We attempted to do so by analyzing trolling communication in two nationally different game imageboards, and our analysis shows that while there are differences between the methods of trolling in Russian and Brazilian online gaming imageboards, there are still several similarities.

With so much in common between both samples, we find that there might be an overall trolling and game culture that spreads across borders and is spread broader than any national culture. Goodfellow (2014) notes that there are trolling differences in-game between Russian and English players, and Fragoso (2015) finds that Brazilians gamers also have unique trolling features. Our findings indicate, however, that strategies of trolling are very much alike in both national imageboards, with some slight differences. While this might not be indicative of the national game cultures (or a global game culture) as a whole, it does signal that the culture of imageboards is somewhat homogenous, and that a global trolling or imageboard culture is certainly very possible. A culture that is only slightly appropriated by national locales; observable in the minor differences when it comes to acceptance of trolling, the victims of these attacks, or the topics that trigger them. Due to the homogeneity observed in these imageboard communities, we can only assume that the nationally appropriated game cultures would also share a number of qualities, hinting at the possibility of a global game culture that is adopted and augmented with national characteristics.

Limitations and further research

One important limitation to note is that results of our research may reflect specific characteristics of the chosen online gaming communities or of selected threads, rather than overall Russian or Brazilian trolling behavior.

An additional limitation is the identity of participants observed. Although they spoke Russian or Portuguese, there is no way of verifying what their real nationality is, or what culture they identify with. Hence, we assume that our sample represents either the Brazilian or Russian online imageboard community. Moreover, there is also a small risk of confusing trolls with inexperienced, young or vulnerable users (Hardaker, 2010, 226).

In the future, it would be interesting to analyze images in a separate codebook. Images not only enrich the context of the text but can also shed light on useful details regarding trolling and Internet behavior. Another suggestion for future research is to refine the topic of game content into subcategories, since this topic was coded more than any other in both samples. This is not surprising since we were dealing with a forum about games, however; this can be also an indication that varying results might be achieved if discussion surrounding additional aspects of games are analyzed separately.

References

2ch.hk. (2016). /v/ – Video Games General – Catalog – 2ch. [online] Available at: https://2ch.hk/vg/ [Accessed 25 Aug. 2016].

55chan.org. (2016). /jo/, /lan/ – Jogos – Catalog – 55chan [online] Retrieved from www.55chan.org

Anderson, C. A., Gentile, D. A., & Dill, K. E. (2012). Prosocial, antisocial, and other effects of recreational video games. In D. G. Singer, J. L. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of children and the media (2nd ed.) (pp.249-272). Thousand Oaks, CA US: Sage Publications, Inc.

Antonio, B. L. C. T (2013). Nós somos anonymous: As relações comunicacionais entre o coletivo Anonymous e a mídia (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://sapientia.pucsp.br/handle/handle/4515

Bakioglu, B. (2009). Goon culture, griefing, and disruption in virtual spaces. Journal of Virtual Worlds Research, 1(3), 4–21.

Bargh, J. A., McKenna, K. Y. A., & Fitzsimons, G. M. (2002), Can you see the real me? Activation and expression of the "True Self" on the Internet. Journal of social issues 58, 1, 33–48.

Bernstein, M. S., Monroy-Hernández, A., Harry, D., André, P., Panovich, K., & Vargas, G. (2011). 4chan and /b/: An analysis of anonymity and ephemerality in a large online community. In Proceedings of AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media (ICWSM) (pp. 50–57). Menlo Park, CA: AAAI Press.

Bishop, J. (2014). Trolling for the Lulz? Using media theory to understand transgressive humour and other Internet trolling in online communities. In Bishop, J (Ed.) Transforming Politics and Policy in the Digital Age (pp. 155-172). IGI Global.

Coleman, G. (2014). The many faces of anonymous. London: Verso.

Consalvo, M. (2005). Gaining advantage: how videogame players define and negotiate cheating. Paper presented at the DIGRA 2005: Changing Views, Worlds in Play. Vancouver, Canada.

Crawford, G., & Rutter, J. (2006). Digital games and cultural studies. In J. Rutter & J. Bryce (Eds.), Understanding Digital Games, (pp. 148-165). London: SAGE

Dovey, J., & Kennedy, H. W. (2006). Game cultures: Computer games as new media. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Downing, S. (2009). Attitudinal and behavioral pathways of deviance in online gaming. Deviant Behavior, 30, 293–320.

Driessen, P., & Diele, O. (2013). State of online gaming (Rep.). Retrieved August 22, 2016, from Spil Games website: http://auth-83051f68-ec6c-44e0-afe5-bd8902acff57.cdn.spilcloud.com/v1/archives/1384952861.25_ State_of_Gaming_2013_US_FINAL.pdf

Elmezeny, A., Wimmer, J. (2018). Games without frontiers: A framework for analyzing digital game cultures comparatively. Media and Communication. 6(2), 80-89.

Fragoso, S. (2015). HUEHUEHUE eu sou BR. Revista Famecos, 22(3), 129-146.

Fragoso, S. & Hackner, F. (2014). "HUEHUEHUE BR é só zuera": um estudo sobre o comportamento disruptivo dos brasileiros nos jogos online. Proceedings of Culture Track of the XIII Brazilian Symposium on Computer Games and Digital Entertainment (pp. 383-392). Porto Alegre, RS.

Fichman, P., & Sanfilippo, M. R. (2014). The bad boys and girls of cyberspace: How gender and context impact perception of and reaction to trolling. Social Science Computer Review, 33(2), 163-180.

Fichman, Pnina, and Sanfilippo (2016). Online trolling and its perpetrators: under the cyberbridge. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Gammon, A. (2014). Over a quarter of Americans have made malicious online comments. YouGov, October 20. Retrieved 23.01.2016 from: https://today.yougov.com/news/2014/10/20/over-quarter-americans-admit-malicious-online-comm/

Goodfellow, C. (2014). Russian overlords, vodka, and logoffski: Russian- and English-language discourse about anti-Russian xenophobia in the EVE online community. Games and Culture, 10(4), 343-364.

Griffiths, M. D. (2014). Adolescent trolling in online environments: A brief overview. Education and Health, 32(3), 85-87.

Hardaker, C. (2010). Trolling in asynchronous computer-mediated communication: From user discussions to academic definitions. Journal of Politeness Research. Language, Behaviour, Culture, (6), 215-242.

Hardaker, C. (2013). "Uh. … not to be nitpicky… but … the past tense of drag is dragged, not drug.": An overview of trolling strategies. Journal of Language Aggression and Conflict JLAC, 58-86.

Hepp, A. (2011). Cultures of Mediatization. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Hepp, A. (2015). Introduction. In Blackwell, W. (Ed), Transcultural Communication. Retrieved from: http://www.andreas-hepp.name/hepp_2015_introduction-2.pdf

Jane, E. A. (2014). "You're an ugly, whorish, slut": Understanding e-bile. Feminist Media Studies, 14, 531–546.

Kirman, B., Lineham, C., & Lawson, S. (2012). Exploring mischief and mayhem in social computing or. Proceedings of the 2012 ACM Annual Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems Extended Abstracts – CHI EA '12.

Knuttila, L. (2011). User unknown: 4chan, anonymity and contingency. First Monday, 16(10), 1-12.

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Livingstone, S. (2003). On the challenges of cross-national comparative media research. European Journal of Communication, 18(4), 477-500.

Ludemann, D. (2018). /pol/emics: Ambiguity, scales, and digital discourse on 4chan. Discourse, Context & Media, 92-98.

Manivannan, V. (2012,). Attaining the ninth square: Cybertextuality, gamification, and institutional memory on 4chan. Enculturation, 1-21.

Marone, V. (2015). Online humour as a community-building cushioning glue. European Journal of Humour Research EJHR, 3(1), 61-83.

Mäyrä, F. (2008a). Open invitation: Mapping global game cultures. Issues for a sociocultural study of games and players. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 11(2), 249-257. doi:10.1177/1367549407088337

Mäyrä, F. (2008b). An introduction to game studies: Games in culture. London: SAGE.

Mäyrä, F. (2016). Exploring Gaming Communities. In Kowert, R & Quandt, T (Eds.). The Video Game Debate: Unraveling the Physical, Social and Psychological Effects of Video Games. (153-176) New York: Routledge.

Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative Content Analysis. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(2).

McDonald, K.(2015). From Indymedia to Anonymous: rethinking action and identity in digital cultures. Information, Communicatio & Society, 18(8), 968-982.

Morrissey, L. (2010). Trolling is a art: Towards a schematic classification of intention in internet trolling. Pragmatics and Intercultural Communication 3(2), 75-82.

Newzoo. (2016, June). The 2016 global games market report | Segments [Chart]. In Newzoo. Retrieved October 25, 2016, from http://resources.newzoo.com/hubfs/Reports/Newzoo_Free_2016 _Global_Games_Market_Report.pdf

Nissenbaum, A., & Shifman, L. (2015). Internet memes as contested cultural capital: The case of 4chan's /b/ board. New Media & Society, 1-19.

Phillips, W. (2015). This Is Why We Can't Have Nice Things. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Potapova, R. & Gordeev, D. (2015). Determination of the internet anonymity influence on the level of aggression and usage of obscene lexis. In Proceedings of the 17th International conference Speech and Computer (SPECOM 2015). Athens, Greece, September 20-24, 2015, volume 2, pages 29–36. University of Patras Press: Patras.

Seay, A. F., Jerome, W. J., Lee, K. S., & Kraut, R. E. (2004). Project massive. Extended Abstracts of the 2004 Conference on Human Factors and Computing Systems - CHI '04.

Shaw, A. (2010). What is video game culture? Cultural studies and Game studies. Games and Culture, 5(4), 403-424.

Smirnov, F. O. (2005). Internet-obshhenie na anglijskom i russkom yazykah: Opyt lingvokul'turnogo sopostavleniya [Internet communication in English and Russian languages: Experience of linguo-cultural comparison]. In Proceedings of the 2005 "Dialogue" Conference on Computational Linguistics and Intellectual Technologies. Bekasovo, Russian Federation, 2005.

Sparby, E.M (2017). Digital Social Media and Aggression: Memetic Rhetoric in 4chan's Collective Identity. Computers and Composition, 85-97.

Suler, J. (2004). The online disinhibition effect. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 7(3), 321-326.

Taylor, T.L. (2006). Does WoW Change Everything? How a PvP server, multinational player base, and surveillance mod scene caused me pause. Games and Culture, 1(4), 318-337.

The NPD Group: Report shows increased number of online gamers and hours spent gaming. (2013, May 02). Retrieved August 22, 2016, from https://www.npd.com/wps/portal/npd/us/news/press-releases/the-npd-group-report-shows-increased-number-of-online-gamers-and-hours-spent-gaming/

Williams, J. P., Hendricks, S. Q., & Winkler, W. K. (2006). Gaming as culture: Essays on reality, identity and experience in fantasy games. Jefferson, NC: McFarland

Wimmer, J. (2012). Digital game culture(s)s as prototype(s) of mediatization and commercialization of society: The World Cyber Games 2008 in Cologne as an example. In J. Fromme & A. Unger (Eds.), Computer games and new media cultures: A handbook of digital games studies (pp. 525–540). London, New York: Springer.

Wolf, M. (2015). Video Games Around the World. Cambridge: MIT Press.