Sonic Mechanics: Audio as Gameplay

by Aaron OldenburgAbstract

This paper will discuss the past and potential future intersections between game design and theories within contemporary sound art. It will look at methods for broadening the ways in which videogames engage with the world of audio. The author will describe his design process in the creation of several experimental audio games. These range from music composition based on chance game events to silent games that simulate aspects of sound. Future experiments and applications are suggested.

Keywords: audio, sound art, conceptual art, Proceduralism, experimental, acousmatic, non-cochlear, experimental, artgames, vision-impaired

Introduction

While audio has always been a major component of videogame design, and currently there is a popular trend to create music-based gameplay, there have been limits to the extent of audio exploration. This paper discusses recent experiments in audio-based gameplay. It presents observations on the effects of these experiments, contextualizes them within the history of sound in games as well as sonic experimentation within the fine arts, and draws attention to areas of current and future experimentation. It analyzes the potential contributions of gameplay to the realm of sound art and gives examples of work that straddles the borders of these fields, particularly audio-based digital games.

The author created a series of short games that explore new forms of audio-based game design. The intention of these gameplay experiments is to broaden the ways in which videogames engage with the world of audio. Thus, the author looks to the relatively new area of sound art and its related body of artwork and theory as the springboard to experimentation with gameplay. Games that are discussed use gameplay for collaborative sound effect-based music composition, attempt to simulate how humans engage with sound, as well as create visual and auditory landscapes based on invisible (and sometimes sub-auditory) properties of audio. They all specifically strive to address under-explored areas in audio-based game design.

Sound Art & Interactivity

In order to discuss the potential for merging of the two fields, this paper will give background and definitions to sound art as well as game design. Neither have definitions that are universally agreed-upon. In the mid-80s Dan Lander, an audio artist, coined the term "sound art" to refer to what was known as experimental music (Licht, 2007, p. 11), but examples of what may now be called "sound art" date back to the early 20th century. Composer John Cage famously declared that all sound can be music (Licht, 2007, p. 12), an idea that was preceded a few decades earlier by Futurist Luigi Russolo's essay "The Art of Noises" (1913), which advocated for dissonant musical compositions consisting of "noise-sounds" created by everyday objects and events rather than musical instruments. The realm of sound art goes beyond performance, and encompasses installation and sculptural work that produces or references audio. Experiments in sound art include exploration of spatial arrangement of sound, the effects of sound physically and cognitively, and the extraction of sound from otherwise inaudible objects and events.

Russolo's The Art of Noises was a letter-form manifesto with the aim to expand musical vocabulary to include the variety of timbres found in noises. His argument was that in the industrial age, human ears were becoming more accustomed to discordant noises, to the extent that they become "pleasant", and in fact our ears are no longer satisfied with the limitations of musical notes but "demand an abundance of acoustic emotions", which noise-sound provides. His goal was to create music by "attun[ing] and regulat[ing] this tremendous variety of noises harmonically and rhythmically", using the rich variation in noise while also modifying the sounds to fit compositional purposes. In a sense, this is a more honest approach to musical composition, as all abstract musical notation is divorced from the reality of the actual sound a performance produces. Russolo's type of music embraces the "multiple, complex, heterogeneous, and three-dimensional" nature of sounds, the "specific events" that the performing of musical notation creates (Altman, 1992, p. 16). This is composition with traditional authorship, without necessarily an improvisational or chance element, but harnessing sound that is outside of the realm of traditional Western musical notation and instruments.

As the definition of music has thus been expanded, it is difficult to differentiate what is to be termed experimental music and what is sound art, if there is even any distinction to be made. Some insisted this blurring required a different approach to engaging with music. "[Composer] Morton Feldman once said that his music should be approached 'as if you're not listening, but looking at something in nature; the loud and repeated sounds are akin to any unexpected natural features that might suddenly appear out of nowhere on a country walk'" (Licht, 2007, p. 74)—something that could be said about many sound art installations. Various experiments in sound art could easily be categorized under experimental music:

"disembodied sound, sound superimposition, sound and visual time reversal, abrupt sound breaks, abrupt tonal contrast, sounded edited to create the effect of inappropriate physical connection with the image, synthetic sound collage, inappropriate sounds, mismatching of sound and visual distance, mismatching sound and visual location, metaphorical use of sound, sound distortion, technological reflexivity, association of one sound with various images, and simple asynchronies of sound and image" (Kahn, 2001, p. 142).

Many experiments in sound art and experimental music forego standard notation for compositional techniques based on chance, improvisation and the influence of the surrounding environment.

Improvisation in music has a history that dates back to the organum melodies of medieval Western Europe and the ragas of Indian classical music. It generally begins with a loose composition or set of rules within which musicians perform spontaneously (with the exception of free improvisation, where there are no rules). Players are acting with a specified amount of freedom within the guidelines set by the composer.

It would be necessary that for music to be interactive, to be created within the space of a game, there would need to be an element of improvisation. A common definition of interactivity defines it as a feature of a communication medium, one that allows it to be "altered by the actions of a user or audience, as well as suggesting a technology which requires input from a user to work effectively" (as cited in Cover, 2006, p. 142). Musical improvisation generally only gives interactive choice from the composer to the musician(s), still leaving the audience as passive listeners.

In the 1950s, however, sound art and interactivity crossed paths in a way that empowered the audience as active participants in the performance of a work. Composer John Cage, who had begun advocating the idea that all sound was music, whether it was arranged with regard to pitch and harmony or not, created a "silent" composition titled 4'33" (1952). This is a block of time where the performers are still and the noises the audience and the environment created become the performance. The composition invites sounds that musicians normally want to avoid disrupting their performance, such as coughs, murmurings, and the sound of traffic outside. Seth Kim-Cohen disagrees with the notion that intrusive external sounds are to be avoided, stating that "only music includes, as part of its discursive vocabulary, a term for the foreign matter threatening always to infect it: 'the extramusical'" (2009, p. 39). These extramusical interruptions are what John Cage intended to bring into the musical performance. Much of the audience participation was inadvertent rather than intentional, however, as many came with the expectation of a passive performance. Whether their contributions were intentional or unintentional, this could be seen as giving authorial control to the audience as far as the audio content of the piece was concerned. As such, it is considered an early interactive artwork.

Interactivity has been deemed to empower the audience by some and dissolve the "traditional concept of audiencehood" by others (Cover, 2006, p. 10). The role of authorship in interaction design becomes less about authoring content than about authoring rules, or spaces for the audience to create content. The artwork emerges through a dialog between the audience and artist.

Audio Games

The definition of a game provided in Rules of Play is "a system in which players engage in an artificial conflict, defined by rules, that results in a quantifiable outcome" (Salen & Zimmerman, 2003, p. 80). Artists and composers have used game rules to influence the production of sound and musical composition. For example, experimental composer John Zorn composed Lacrosse (2000) and Cobra (2002) with rules of performance linked to game rules, but in ways that were abstract and unexplained. Game rules would seem, at the very least, to be potential resources for chance-based musical composition, through linking musical events to game events, or creating rules for the emergence of more complex musical structures.

Both the designing of game rules and the composing of music require the creation of a space for the direct action of a participant: players to create the game and performers to interpret the score. In gameplay, the actions of the players are less predictable, a series of intriguingly surprising events that the designer sets in motion, performed within the boundaries that the designer creates. Musical composition introduces fewer variables, unless the composition requires improvisation. The openings that the improvisational composition provides are the closest mirror to the area where game players are encouraged to express themselves. In both cases the author cedes some control through interactivity.

Although music-based play in games has been popular for some time, dating as far back as Mozart’s musical dice game (Kayali, Fares, 2007, p. 2), other forms of sound are relatively under-explored as the basis of game mechanics. The most common type of audio gameplay is the music game. There are two major categories of music games: those that build gameplay around pre-existing compositions and those that generate dynamic music as a result of player action. In Parappa the Rapper (NanaOn-Sha, 1996), players must hit specific buttons in time with the beat of pre-composed music, leaving little room for creative improvisation. By contrast, the game Rez (United Game Artists, 2001) creates music as a result of the player’s shooting rhythm. The player's goal can either be to shoot enemies, with music being an unintended consequence, or she can specifically time her shots to proactively alter the music. There are other games that take the reverse approach, where the environment or other gameplay elements are created by the music. Vib Ribbon (NanaOn-Sha, 1999) is one of those, generating the game's level map and obstacles from the rhythm of the game.

Generative music games range from the linear, like Rez, to open-ended sandbox toys like Brian Eno’s Bloom (Opal Limited, 2008) for iPhone — debatably not games — where the player is free to experiment, using tools within constraints with the sole objective of making music. Often there is a strong visual component, and play usually involves the manipulation of visual space with audio as a side-effect of this. The iPhone toy Sonic Wire Sculptor (Pitaru, 2010) is an example of this, as players design a three-dimensional rotating sculpture, creating music with the location and direction of the lines. Other iPhone apps like Bloom and SynthPond (Gage, 2008) also have a strong, two-dimensional spatial method of composing music. Users of this type of sound toy almost always make conventionally melodic and harmonic music, as they are limited in choice of notes. Some games, like Rez, even control the rhythm of the player’s composition, as the note associated with the player’s action will be slightly delayed to fall on the next beat. Broader definitions of music, such as those proposed by Cage and Russolo, have not been widely explored in music-based digital games or sound toys.

Games for the Blind and Acousmatic Sound

Among researchers and independent game designers a popular challenge is to create games for a visually-impaired audience. Usually these are audio-only, although there is at least one example of a game that makes use of haptic, or touch, feedback. The main challenge in a game without visuals is a similar one to being visually impaired in real life: how to develop a mental map of the environment. Without the sense of touch, one relies on the sounds objects make. These are often exaggerated temporally or by volume. Objects in the gameworld that would not normally make noise now emit sounds, others repeat themselves when normally they would not, so the player has a constant understanding of where they are in relation to the objects.

Another major challenge is inaccessibility of genuine 3D audio. Some non-visual games, such as Mudsplat (2000) for the PC, simply reduce their play field to a two-dimensional plane, so that players can orient themselves with a stereo headset. Others, such as Papa Sangre (2013) for iOS, simulate 3D audio by making the sounds quieter when the sounding objects are behind the player than when they are in front. There is, however, nothing physically telling the player's ears whether a sound is coming from front or back in the same way that headphones can tell them left or right, so location of objects in this type of game is a conclusion arrived at through reasoning rather than through sensing.

Others forego the challenge of orienting a player within a dark space by telling the player exactly where they are through narrative. Kaze No Regret (Eno, 1997), rather than being a real-time action game, is a text adventure set to speech, narrating to the player a description of their surroundings rather than placing sounding objects in virtual space.

In a traditional game, there are two main types of dynamic audio that occur: interactive audio that responds directly to the player's immediate actions and adaptive audio that responds to the game system itself, either reacting to or predicting events and thus indirectly controlled by the player (Collins, 2007, p. 2). The former are diegetic (coming from within the fictional world) and the latter usually non-diegetic. Alongside this is static audio, often a game's musical soundtrack, though nowadays these are becoming more dynamic.

In audio-only games, it is helpful to break these distinctions down more. Friberg and Gärdenfors divide up the sounds in their audio games into avatar, object, character, ornamental and instruction sounds. Avatar, object and characters sounds refer to the interactive audio that distinguishes between the player's character, objects present in the environment and sounds coming from non-player characters (NPCs). There are several ways to make an object known. The presence could be indicated continuously, through a repetitive sound, momentarily, for instance when the player bumps into it, or spontaneously, based on another in-game action or rule. Ornamental sounds are adaptive audio that do not necessarily correspond to gameplay. Instructions are usually given by speech (Friberg & Gärdenfors, 2004, p.4).

This of course can lead to the problem of having too many sounds playing at once and confusing the player. One way to avoid confusion is to mix event-based and repeating sounds. Most game environments tend to be complex, and with our eyes we can take in most of the complexity fairly rapidly. We distinguish objects, shapes and the layout of a scene holistically. With audio, the player is relying on a time-based medium to convey what the eyes take in within a fraction of a second. What games such as Mudsplat (2000) and Papa Sangre (2013) do is simplify the rooms and let the player's imagination fill in the rest. The design goal is to find the shortest sounds that hint at evocative scenes. Monster sounds in dark, horror-themed environments are particularly successful doing this in the aforementioned games.

There are audio cues to give players an immediate sense of an overall environment. An echo can read as a cavernous indoor area. Rain can give away the presence of large structures and hint at their material. Communicating spatial relationships between the general shapes dividing up an environment would seem to be an interesting area of research for blind games.

Another strategy is to train the player to recognize certain musical phrases, called "earcons" (from the word "icon"), to mean something complex (Friberg & Gärdenfors, 2004, p. 4). This is how a level's end goal is designated in Papa Sangre (2013), which is a concept that would be difficult to convey using recognizable sound effects. Some argue that having "a distinct auditory beacon towards which they can head... [will] help [players] to create a mental map of the entire game space…" (Collins & Kapralos, 2012, p. 4).

Even more experimental blind games have come from the free independent game scene, student game projects, as well as artists making games for gallery exhibition. Makers of these types of games, in a manner similar to to independent short filmmakers, have more freedom to experiment than commercial mainstream or even independent commercial game designers, as the consequences of failure are smaller. There is less money involved, and these communities embrace failed projects as worthwhile for their own sake. Eddo Stern’s current work in progress, Dark Game (2008), involves sensory deprivation, and a side effect of blindness: the heightening of other senses. It is an art installation for two players, one of whom is deprived of sight, but wears a headset that provides haptic feedback, as well as audio. Increpare’s downloadable game Forest (2009) is without visuals, a game where the player is guided only by abstract sound. Copenhagen Game Collective’s Dark Room Sex Game (2008) is an audio-only game where two players competitively try to bring each other's invisible avatar to orgasm through shaking of Wii motion controls, the designers attempting to create awkwardness between the players through sound. In these games, sound is the subject and the effect of sound is the goal. The meaning behind sounds, their impact on the choices the player makes, is the content.

Acousmatic sounds are those divorced from their origins. In a blind game, all sounds are necessarily acousmatic, as the player cannot see from where they came. Videogames, particularly those with three-dimensional, first-person environments, change the player's role from passive to active listener, as audio is used as a cue to anticipate near-future events, as well as understand the parts of the world the player cannot see (Collins, 2007, p. 8). The player makes decisions based on sounds, for instance turning if they hear an enemy behind them. Acousmatic sounds play a particularly large role in mainstream horror games, sparking the imagination and fear of unseen presences, or by disturbing the player with a sense of the uncanny through sounds that do not match their assumptions about the environment (Tinwell, Grimshaw & Williams, 2010, p. 10). Further research into blind games could, in this sense, provide lessons applicable to games with visuals as well, since all rely on sound to give a sense that there is a world larger than what the player sees.

Acousmatic sounds play a significant role in early experimental music, particularly the Musique Concrète, or "Concrete Music" of Pierre Schaeffer, made of sound effects separated in use and occurrence from the objects that created them. He argues that this type of music forces the audience into a state of active listening "that would avoid the habit of searching for the semantic properties of sounds and instead try to find ways of describing their specific properties and perceptual characteristics" (Stockburger, 2003, p. 4). This is opposite of the way in which acousmatic audio is used in games, as players actively search for the meaning behind sounds, and often eventually encounter the source. With sound, players are cued "to head in a particular direction or to run the other way." (Collins, 2007, p. 8). The unseen sounding objects are meant to be taken literally, whereas in Schaeffer's work, the listener is not supposed to think about the object or activity making the sound, but its musical qualities. However, those listening likely get a certain pleasure from the back and forth between the two types of listening, a split mind that is conscious of or searching for the origin but also appreciating the musical qualities divorced from it. Film theorist Rick Altman argues that "[b]y offering itself up to be heard, every sound loses its autonomy, surrendering the power and meaning of its own structure to the various contexts in which it might be heard, to the varying narratives that it might construct," (1992, p. 19) and acousmatic sound gives the designer and audience the opportunity to play with those narratives. There seems to be much opportunity to experiment with the meanings of sounds that occur off-screen, and bend the player's expectations of their relevance to the choices made in the game.

Just as types of sound can be broken into categories, as seen above, so can types of listening. Film sound theorist Michel Chion defines three modes— casual, semantic and reduced listening:

"Casual listening refers to listening for the source of the sound, attempting to understand what caused the sound. Semantic listening is used when understanding auditory codes such as speech or Morse code. Reduced listening is less common. This third listening mode is used when listening to qualities of a sound without considering its source. Thus, reduced listening is involved when appreciating music by listening to pitches, harmonies and rhythms" (Friberg & Gärdenfors, 2004, 4).

Thus reduced listening is how Musique Concrète should be approached and casual listening how most in-game effects are heard. Semantic listening should be reserved for NPC speech or instructions, although it would be interesting to find new ways to require this of other in-game sounding objects, for the sake of puzzles or other challenges.

Figure 1: Screenshot from Escape the Cage.

The 3D spatio-centric worlds of videogames give artists who work with audio a space where they can explore goal and conflict-based compositional techniques, giving their audiences the potential to engage and procedurally explore the processes of hearing and listening. The game Escape the Cage (2011) explores collaborative, if accidental, asynchronous composition between two players over a network. It was a submission for the Experimental Gameplay Project's March/ April 2011 theme "Cheap Clone," and is a play on the popular Escape the Room-style Flash games, such as Crimson Room (2006). In these types of games a player is trapped in a small room and, using point and click mechanics, has to solve puzzles to find her way out. In Escape the Cage, one player finds herself trapped in the room; the other finds herself outside, listening. Although to the trapped player it appears to be a puzzle game where the player must hunt in her environment for objects to help her escape, there is actually no solution. The listening player simply opens the door and frees the other player, who has inadvertently been creating a cacophony by picking up objects and trying to use them to escape, some of which are percussive, others of which are repeating. The sounds for all are exaggerated, and many of them reference typical objects found and used in Escape the Room-style games, such as keys, which instead of opening doors, produce a scraping sound in every location clicked. In contrast to the trapped player who is in the room performing a cacophony, the listening player only has two options: to open the door or keep listening to the acousmatic sounds the other is producing. As a result, she has a direct, even if accidental, part in the composition, as the amount of time in which she listens limits the other player’s indirect performance.

These are not the acousmatic sounds of a lurking NPC behind the player, but one on which the player is actively eavesdropping. Jennifer González, an art writer who analyzes Christian Marclay's piece Door, an artwork that put the viewer into a similar position, states that it "suggests not only that forms of listening might be a kind of regular or illicit passion but also that the space of a room behind any door is itself an instrument, a reverberating chamber for sound" (2005, p. 44). David Toop elaborates on a particular kind of acousmatic sound which he calls 'vicinal' noises, "the sound of activities that transmit through partitions, the intimacies of private domestic life that soak through architecture to invade the lives of others" (2010, p. 88). Players such as the blogger Pierrec writing on l'Oujevipo (2011) felt that the waiting and listening mechanic was in fact more interesting than exploring the room, even though in the latter the player arguably had more choices and agency. As the gameplay is asynchronous, the listening player is actually listening to the recorded performance of the previously-trapped player, and the next player to be trapped will be restricted by the time the previous listener waited to open the door. These acousmatic sounds are not only detached from visuals but from their place in time as well. The listening player’s role is as eavesdropper, but with control over the end of the performance. The listener realizes their choices are limited and may decide to enjoy playing as the audience. The performing player has a misconception as to the constraints and results of his or her gameplay.

Chance-based and Spatial Musical Composition

The incorporation of two players who are composing together, intentionally or unintentionally, brings an added psychological dimension to the gameplay, performance and listening experience. It enters the realm of the sometimes mysterious social context of online interactions, where the source of all actions on the part of the player are invisible, but lead the imagination to conjure up the other player, much in the same way acousmatic sounds trigger an imagining of their source.

Interactive art that creates some give and take relationship between the designer and player, or between multiple players, engages some of the ideas of relational aesthetics. This is, as defined by French art critic Nicolas Bourriaud, "an art taking as its theoretical horizon the realm of human interactions and its social context, rather than assertion of an independent and private symbolic space" (1998, p. 14) It states that "forms come into being" by an "encounter between two hitherto parallel elements" (p. 19). Whereas other forms of art with passive audiences might be a shared activity in the sense that audience members are in the same space having a similar experience, relational art focuses solely on the encounter, which although is generally seen as ephemeral, is intended to create a lasting form (Bourriaud, 1998, p. 21). Participation in Escape the Cage creates something out of the space of the interaction, part of which is recorded over a network, and part of which is imagined by the participants.

Although the performer in this game has more choice in actions than the listener, the listener has a powerful control over the ending, and thus the timespan, of the composition. Composers like John Cage often give listeners the same amount of agency, or at least credit, in composition. David Rosenboom in an essay in Arcana redefines composer to include listeners, among many others who have an active role in the creation and continued existence of musical pieces:

"By composer I often simply mean, the creative music maker. This may include creative performers, composers, analysts, historians, philosophers, writers, thinkers, producers, technicians, programmers, designers and listeners—and the listeners are perhaps the most important of these. The term composer is just convenient shorthand. To the extent that music is a shared experience, audiences must understand that this experience can not take place in a meaningful way without their active participation. This requires a view of LISTENING AS COMPOSITION. LISTENERS ARE PART OF THE COMPOSITIONAL PROCESS" (2000, p. 206).

Considering listeners to be a part of the compositional process is focusing on the relational aspect of a performance, that moment where the composition meets the audience at the point of music creation.

Figure 2: Screenshot from Invisible Landscaping.

The improvisational aspect of the musical gameplay also make it a form of chance-based composition, or composition that involves randomness or spontaneous events. This type of composition cedes control over timing to environmental or other factors that are not a direct result of conscious choices on the part of the performer. Type of sound, volume, duration, and repetition, although often guided by rules, are controlled by agents that are not the original author of the work.

Another method of ceding control of a sonic experience is to arrange a composition spatially. Often this is seen in sound art installations, where sound emitters are arranged meaningfully throughout a space for the audience to pass through non-linearly. Audience choice in movement decides the order in which sounds are heard and the ways in which they are blended. In an article in the new media art magazine neural, Matteo Marangoni states, “Sound installations frequently dispense with linear musical time by means of spatial arrangements. In the work ‘another soundscape’ by Chung-Kun Wang, linear time is reintroduced and represented spatially following the model of western musical notation” (2010). Videogames, whether two- or three-dimensional, are largely spatial in their interactions. The interactive triggering of diagetic sounds in games, in combination with ambient sounds that are outside the player’s control, can work together to form a spatially composed music or sound art piece.

An attempt at spatial composition, Invisible Landscaping (2011) is game created by the author that allows the player to garden an audio terrain, trimming down larger, identifiable ambient sound and watering and growing small, abstract, subterranean sounds. By distinguishing sounds within noise, the player is able to create a new soundscape. It is partly inspired by John Cage's dichotomy of large and small sounds, and his methods for searching for them:

"small sounds were to be detected through a supple direction of attention and more often using technological means, whereas loud sounds were to be found through a peripatetic trek that would place him in the vicinity of a loud sound. Small sounds were absolutely everywhere; loud sounds dwelled in certain locations and drew Cage himself in their direction, as if by gravitational pull of their mass" (Kahn, 2001, p. 234).

Through the metaphor of gardening, the player inverts their sonic environment. Although the game has no end state, a goal is implied: to eliminate the large sounds and grow the small sounds so that eventually the subterranean world dominates. Although the game has visuals, much of the challenge is still in the realm of blind games, in that the player is searching through the invisible environment, using the microphone as a "sound-camera" (Altman, 1992, p. 23), zooming through the use of either a wide or narrow focus, for the sources of large and small sounds. Blogger Line Hollis wrote that the game did not give "quite enough information to make sense of your environment," and that it was difficult to formulate goals (2011), a testament to the challenge of navigation and orientation in non-visual space.

Sonic Simulation

As the visual arts became more conceptual, shifting importance from the retinal, meaning the immediate response to visuals, to ideas and texts, so too have some sound artists begun focusing on the idea of sound and the imagined experience. Christian Marclay's work in particular focuses on implied sound, provoking the imagination of the viewer to have auditory hallucinations. His framed photograph of the Simon and Garfunkel record The Sounds of Silence (1988) produces the aftereffect of sound, a sort of synesthesia as the silent visual provokes the music to play in the audience's head (González, 2005, p. 52). Sonic art theorist Seth Kim-Cohen argues for a conceptual sound art that is not based on what is heard, “but in the elsewhere/elsewhen engagement with ideas, conventions and preoccupations” (2009, p. 37).

Are there ways that games can represent sound without reproducing it? Games are simulations, or, as Salen & Zimmerman put it, “procedural representations of reality” (2003, p. 457). It is worth noting that most representations in gameworlds, whether they be of death, conflict, or conversation, are all simulated, yet sound is almost always reproduced, as are visuals. An important area to explore, it would seem, would be simulation of sound through gameplay: having the player perform actions that are representative of the physical and cognitive aspects of hearing, listening and sounding. These qualities could be represented in a game by gameplay, not just by visuals but by the player’s moment-to-moment actions. Through game mechanics one could explore the emotional engagement with hearing without the production of audio.

It is taken for granted that those who are hearing-impaired do not have the level of challenge in playing videogames that those with visual impairments have. We are used to seeing closed captions on TV to allow the hearing impaired to know intellectually the content of what the hearing audience is experiencing, and take for granted that this system of visual alerts and transcriptions is enough. There are, however, other aspects of engagement with sound that are not communicated through a summary description of its content.

A game whose mechanics attempt to simulate aspects of sound would not necessarily have to make noise any more than a simulated killing in a typical first-person shooter has to result in a death. There are elements intrinsic to sound that games can appear to simulate with their mechanics. An attempt to simulate these intangible qualities of auditory experience would generally fall under the category of "Proceduralist Games," a term coined by game studies theorist Ian Bogost. These are games that are abstractly expressive through the use of their rules, more so than narrative. He describes this type of game as valuing abstraction over realism, in an attempt to cause reflection in the player by provoking questions (Bogost, 2009).

What aspects of audio hold potential for game-based simulation? Consider the following descriptions of sounds in the context of actions, environments and visual representations in videogames. David Toop compares sound’s properties to those of “perfume or smoke,” stating that “sound’s boundaries lack clarity, spreading in the air as they do or arriving from hidden places” (2010, p. 24). He points out that sound “implies some degree of insubstantiality and uncertainty, some potential for illusion or deception, some ambiguity of absence or presence,” and that, "Through sound, the boundaries of the physical world are questioned, even threatened or undone by instability” (2010, p. 36). Sound also has the “ability to stretch across the cut, to meld continuously from one ‘object’ or entity to another” (Kahn, 2001, p. 148). Sound always arrives at our ears blended, like shadows (Dyson, 2009, p. 121). Typical games, by contrast, are often about the manipulation of distinct objects with logical boundaries. Games are often, however, also about discovering alternate universes, and so contain the potential to allow players to explore worlds with fluid boundaries and objects that blend or arrive with ambiguous origins, like sound. The author created a series of videogames that draw on analysis of the human experience of engagement with sound, using it as a starting point for creating new forms of gameplay.

Figure 3: Environment from Optic Echo.

The game Optic Echo (2011) is an attempt to represent visuals as sound is heard. It is a silent game from the perspective of a blind character, a voice-activated game that requires the player to find their way by echolocation in a three-dimensional silent soundscape. The goal of the game is for the player to chase a disappearing man through the maze, following the ephemeral sparks of his footsteps, and inscribe her sound on his body. The player physically screams (or whistles, plays music, etc.) into a microphone to reveal the previously-invisible environment. Visualization of the player’s environment and non-player characters is migratory, ephemeral, like sound. Walls in the environment are not revealed as solid, but as particles moving toward the player from their origins. Using this visualization, the player must guess at the general locations of walls. The location of solid objects, like the origin of sound, must be inferred from the “optic echo’s” movement. Visuals were inspired by Frances Dyson's description in Sounding New Media:

"like the fire, sound is always coming into and going out of existence, evading the continuous presence that metaphysics requires; like the fire also, sound is heard and felt simultaneously, dissolving subject and object, interior and exterior. Like the river, sound cannot be called ‘the same’ since it changes at every point in its movement through a space; yet like ‘Soul,’ it does not strictly belong to the object. Nor can sound's source and ending be defined, for it originates as already multiple, a ‘mix,’ which makes it impossible to speak of ‘a’ sound without endangering the structure of Western thought itself" (2009, p. 121).

Figure 4: Navigating Optic Echo.

Design compromises were made on how closely the visuals should resemble the physics of sounds. Some were made for the sake of playability. For instance, the sound "bounces" once off of each wall, rather than bouncing back and forth between them, which would be a more accurate emulation of real-world physics. Multiple bounces created too much overlap between sounds and it was impossible to tell from where they originated. Also considered was making the echoes linger more, but it was decided that if the beginning and ending of the visuals more closely corresponded to the beginning and ending of the sound the player made, it would be easier for the player to create a mental map of the basic interaction mechanic.

This game is difficult, even with the compromises. Playtesters on online forums often stated that they had trouble understanding the environment and their place within it. Some, even when shown video of gameplay, say that they couldn't get their heads around the sense of space. The goal, however, was to give a less concrete representation of an environment. One player contrasted the game to The Devil's Tuning Fork (DePaul Game Elites, 2010), which also has an environment that is revealed by sound, although with an object that produces it from within the game rather than the player's voice. The way the environment in that game was revealed, however, was still as a concrete representation of the visual, similar to waving a flashlight. Modifications to Optic Echo could still be made for the sake of playability. The echo could be altered based on loudness and proximity to improve the player's ability to get their bearings. Although the intention is to stretch the player's perception of the environment, they should also feel like they have a sense of agency.

Humans cognitively approach sound in ways that we do not engage with our other senses. Could it be that in games, navigating a 3D spatial tactile world is not the best way to move? How about forward and backward through the time of a sound? What choices could the player make as they move, what obstacles overcome? Studying audio gives game designers new ways to construct space and action.

Figure 5: Screenshot from ThatTimeIAlmostDiedAtAConcert.

ThatTimeIAlmostDiedAtAConcert (2011) is a silent touch-based mobile game that proceduralizes the experience of trying to follow a story though interaction with the visual waveform of that story's audio. The player attempts to stay on the path created by the (now silent) waveform of a spoken narrative, while passing distractions pull the player away. The reason for showing the waveform rather than producing the audio from the story is to focus on the experience of attention. The movement of a sound is used as a reference for game movement. Game rules and visual elements can be observed and studied like a static text or painting, but gameplay has the more ephemeral quality of sound and must be observed in motion. Sound artist Christian Marclay compares these qualities:

"repetition isn't a necessity when looking at a static art object, a painting or sculpture that's there as long as you want to look at it. Sound recordings are time-based—more like films that you can look at over and over. But with film you can stop the flow of time and you still get a frame. With sound, you can't stop time, you can only repeat it. The present is instantly relegated to the past. So sound remains more elusive." (González, 2005, p. 121).

Figure 6: Slicing mechanic in Ohrwurm.

Another touch game for Android mobile devices, created in the software Processing, was Ohrwurm (2011). This game was an attempt to provoke auditory hallucination, through visual and tactile interaction with sounding objects. The player is slicing through walls, looking for brass objects against which to hit her sword. The materials of which the walls are made were chosen for their ability to convey implied sound: the sword—silently in reality but perhaps loudly in our heads—scrapes against metal, breaks glass, Styrofoam, dead leaves, macaroni and cheese. Eventually the player finds a resonant object, which vibrates the phone when it is hit. This was an experiment in procedural implied sound, an attempt at tactile/ auditory synesthesia.

Conclusion

Using game mechanics to expressively proceduralize experiences such as sound and using sound to break apart the visual-centric space of games opens up the potential to create new expressive forms of gameplay. Game design also gives artists who work with sound or experimental music the ability to focus their creative decisions on creating spaces and rules for sound to emerge, incorporating spontaneity and the player and audience's external environment in compositions that reinvent themselves whenever they are performed. Audio experimentation in game design can influence in both directions: sound art composition through gameplay, as in Escape the Cage, gameworld space expanded through the influence of sound properties as in Optic Echo, and our relationship with sound inspiring a game mechanic which in turn encourages us to examine the ways in which we engage with audio, such as in ThatTimeIAlmostDiedAtAConcert.

Given that videogames are still heavily defined by the mainstream commercial industry, it may be asked what is the importance of short, free, experimental games. It is sometimes assumed that the usefulness of noncommercial games created for artistic purposes are as prototypes testing mechanics that, if deemed successful experiments, will find their way into mainstream commercial games. This creates a judgment of value that is never considered in the evaluation of experimental film, which is not required to influence Hollywood filmmaking in order to be considered for possible historical or artistic importance. However, a growing community of indie and "artgame" developers (games, often in the Proceduralist style, that deal with "profound, existential themes long associated with fine art and high culture" (Parker, 2013, p. 8)) argue for the legitimacy of short, often freely available, experimental games as important on their own, without having to demonstrate their usefulness to mainstream game design. Tools for game development are becoming more readily available to creators outside of the industry (Parker, 2013, p. 6), and popular independent game designers like Anna Anthropy advocate for the role of outsiders as "important new voices" whose every game created "makes the boundaries of our art form (and it is ours) larger" (Anthropy, 2012, p. 160). Others argue that an independent videogame industry may be "the only answer to creating videogame art," as well as having the added benefit of "end[ing] the cycle of cloning more popular games and making repetitious sequels within the industry" (Martin, 2007, p. 207). In the art world, exhibitions and festivals have focused on experimental games, such as the "Vector Game + Art Convergence" conference in Toronto (2013), as well as contemporary art shows that include games alongside artists of other media such as the New Museum in New York's "The Generational: Younger than Jesus" exhibit (2009), which included Mark Essen's game FLYWRENCH (2007). The impact indie and artgames have on big-budget AAA games is not the main decider of their importance, as they are necessary for moving the medium forward.

That said, there is a great potential for the impact of these experiments to be had on games that are not simply "for art's sake." The aforementioned use of procedural representations of sound to create richer experiences for the hearing impaired by simulating emotional qualities of sounds is an almost totally-unexplored area of research. Games for the blind for a long time were the sole interest of academic researchers and non-commercial indie game designers until recently with the commercial success of non-visual games Papa Sangre (2013)and its follow-up title The Nightjar (2013). It would seem that this possibility also exists for games for the hearing impaired. Experimental sound games also are uniquely posed to discover new uses for acousmatic sounds that can be applied to mainstream games for player emotional response or new ways to use semantic listening as part of a gameplay puzzle or other challenge. There are even examples of mainstream games using experimental audio techniques to great effect, such as Metal Gear Solid 2 (KCEJ Success, 2001), which incorporated microphone-based eavesdropping into gameplay, as the player used an onscreen shotgun microphone to search for an irregular heart pattern among NPCs (Stockburger, 2003, p. 10). Searching for something that cannot be seen through patterns in sound, similar to Invisible Landscaping, has broad potential for puzzle-based gameplay. Further mechanics may be found in audio-only game experiments to augment the experience of mainstream games with visuals.

One of the author's game experiments that relied on a mechanic similar to some mainstream non-audio-based games, but where audio was crucial, was Sound Swallower (2011).

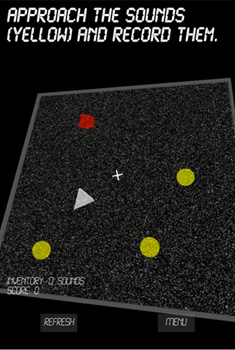

Figure 7: Image of Sound Swallower gameplay.

In this game, the player's goal is to run and collect fragments of her environment's auditory history before it is erased. It uses the iPhone's GPS and built-in microphone to create an environment around the player. It records the ambient audio environment and on top of this it layers abstracted sound effects that are meant to hint at an ephemeral past. Gameplay takes place on a map that corresponds to the player's GPS coordinates. The player runs to locations on the maps that specify the locations of sounds, then records them and brings them back to her base. The Sound Swallower is an enemy that roams the map, absorbing sounds and chasing the player, in a way similar to other games where the player is running from an NPC in a real-world GPS location, such as the iOS game Zombie Escape (Chillingo, 2010). The enemy is loosely based on German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen's conceptual, sanitation-minded "Sound Swallower", a device that "would be equipped with hidden microphones to pick up sounds on the streets and a computer to analyze the sounds, create negative wave patterns, and return them to cancel out the original sounds… " (Kahn, 2001, p. 222). However in the game, the Sound Swallower is not erasing sounds as they are created in the present to create a quiet environment, but is cleaning up an imaginary world where sounds are archived in the air around us. Both Charles Babbage and Thomas Edison, among perhaps many others, felt that sounds lingered in the air, that the air recorded sounds that could potentially be extracted (Toop, 2010, p. 34 & 151). We can use audio-based artgame design to explore myths about sound in ways that allow players to discover their essential truths. This is a game that creates a composition based on the real world ambient environment, and so one truth it explores is that "recorded sound... always carries some record of the recording process, superimposed on the sound event itself… including information on the location, type, orientation, and movement of the sound collection devices…" (Altman, 1992, p. 26) It is about the surprises often found in the aftermath of a recording session, sometimes associated with the supernatural. A reviewer on the iTunes App Store praised the game's use of abstract acousmatic sound as "scary" (as well as the GPS component being "good exercise"), suggesting that the game had found a new way to achieve an effect that is the goal of certain genres of commercial games.

There are many aspects of game environments and narrative that are represented for the player and have never been proceduralized. It is worthwhile to explore how to make each element of a game resonant in the manner unique to games, through their mechanics. Much as visual artists are encouraged to look at the world, to observe it in unfamiliar ways, upside down, focusing on light and color contrasts rather than distinct objects, game designers should focus on a heightened awareness of their moment-to-moment actions and the ways in which they engage with their environments. It is here that there is a wealth of not only novel game mechanics, but mechanics that could resonate on a deeper level with players.

References

Altman, R. (1992). Sound Theory Sound Practice. New York: Routledge.

Anthropy, A. (2012). Rise of the Videogame Zinesters: How Freaks, Normals, Amateurs, Artists, Dreamers, Dropouts, Queers, Housewives, and People Like You Are Taking Back an Art Form. New York: Seven Stories Press.

Bogost, I. (2009). Persuasive games: the Proceduralist style. Gamasutra. Retrieved October 30, 2012 from http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/3909/persuasive_games_the_.php

Bourriaud, N. (1998). Relational Aesthetics. Dijon, France: Les presses du réel.

Cage, J. (1952). 4'33" [music composition].

Chillingo, Ltd. (2010). Zombie Escape. USA: Viquasoft Co., Ltd.

Collins, K. (2007). An introduction to the participatory and non-linear aspects of video games audio. In J. Richardson & S. Hawkins (Eds.), Essays on Sound and Vision (pp. 263‐298). Helsinki: Helsinki University Press.

Collins, K. and Kapralos, B. (2012). Beyond the Screen: What we can Learn about Game Design from Audio-Based Games. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Computer Games Multimedia and Allied Technology. Bali, Indonesia 7-8 May, 2012.

Copenhagen Game Collective. (2008). Dark Room Sex Game. Denmark: Copenhagen Game Collective.

Cover, R. 2006. Audience Inter/active: Interactive Media, Narrative Control and Reconceiving Audience History. New Media and Society, 8 (1): 139—158.

DePaul Game Elites. (2010). Devil's Tuning Fork. USA: DePaul University Game Development program.

Dyson, F. (2009). Sounding New Media : Immersion and Embodiment in the Arts and Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Eno, B. (2008). Bloom. USA: Opal Limited.

Eno, K. (1997). Kaze No Regret. Japan: Sega.

Essen, M. (2007). FLYWRENCH. USA: Mark Essen.

Friberg, J. and Gärdenfors, D. Audio games: New perspectives on game audio. In Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Advances in Computer Entertainment Technology (pp. 148—154), Jumanji, Singapore, 2004.

Gage, Z. (2009). synthPond. USA: Zach Gage.

González, J. (2005). Christian Marclay. London: Phaidon Press.

Hollis, L. (2011). Players are planners. Robot Geek. Retrieved March 21, 2012. Retrieved from http://robotgeek.co.uk/2011/09/27/players-are-planners/

Increpare. (2009). Forest. Retrieved October 30, 2012, from http://www.increpare.com/2009/12/forest/

Kahn, D. (2001). Noise, Water, Meat : a History of Sound in the Arts. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kayali, F., and Martin P. (2007). Levels of sound: on the principles of interactivity in music video games. Proceedings of DiGRA 2007: Situated Play (Tokyo). http://fares.attacksyour.net/site/publications/Entries/2007/9/24_Levels_of_Sound%3A_On_the_Principles_of_Interactivity_in_Music_Video_Games.html.

Kim-Cohen, S. (2009). In the Blink of an Ear : Toward a Non-cochlear Sonic Art. New York: Continuum.

Kojima, H. (2001). Metal Gear Solid 2. Japan: Konami.

Licht, A. (2007). Sound Art: Beyond Music, Between Categories. New York: Rizzoli International Publications.

Marangoni, M. (2010). Another Soundscape, cable car-like sequencing. neural. Retrieved March 21, 2012, from http://www.neural.it/art/2010/09/another_soundscapes_cable_car.phtml

Marclay, C. (1988). The Sound of Silence [artwork].

Martin, B. (2007). Should Videogames be Viewed as Art? In A. Clarke & G. Mitchell (Eds.), Videogames and Art (201-210). Bristol, UK: intellect.

Matsuura, M. (1996). Parappa the Rapper. Japan: Sony Computer Entertainment.

Matsuura, M. (1999). Vib-ribbon. Japan: Sony Computer Entertainment.

Mizuguchi, T. (2001). Rez. Japan: Sega.

Oldenburg, A. (2011). Escape the Cage. USA: Aaron Oldenburg.

Oldenburg, A. (2011). Invisible Landscaping. USA: Aaron Oldenburg.

Oldenburg, A. (2011). Ohrwurm. USA: Aaron Oldenburg.

Oldenburg, A. (2011). Optic Echo. USA: Aaron Oldenburg.

Oldenburg, A. (2011). Sound Swallower. USA: Aaron Oldenburg.

Oldenburg, A. (2011). ThatTimeIAlmostDiedAtAConcert. USA: Aaron Oldenburg.

Parker, Felan. (2013). An Art World for Artgames. In Loading... The Journal of the Canadian Game Studies Association. Retrieved on July 1st, 2013 from http://journals.sfu.ca/loading/index.php/loading/article/viewArticle/119.

Pierrec. (2011). Escape the cage: 10 minutes. Self-published on l'Oujevipo. Retrieved on November 9th, 2012 from http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:hvdf70TSrlEJ:oujevipo.fr/index.php%3Foption%3Dcom_content%26task%3Dview%26id%3D358%26Itemid%3D55+oujevipo.fr+aaron+olsenburg&cd=2&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us.

Pitaru, A. (2010). Sonic Wire Sculpture. USA: Amit Pitaru.

Rosenboom, D. (2000). Propositional music : on emergent properties in morphogenesis and the evolution of music. In J. Zorn (Ed.), Arcana: Musicians on Music. USA: Granary Books.

Russolo, L. (1913) The art of noises. Retrieved October 30, 2012 from http://www.unknown.nu/futurism/noises.html.

Salen, K., and Zimmerman, E. (2003). Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Boston: The MIT Press.

Somethin' Else. (2013). The Night Jar. London: Somethin' Else.

Somethin' Else. (2013). Papa Sangre. London: Somethin' Else.

Stern, E. (2008). Darkgame (prototype stage). Retrieved October 30, 2012. Retrieved from http://www.eddostern.com/darkgame/index.html

Stockburger, A. (2003) The game environment from an auditive perspective. Proceedings of the Level Up, Digital Games Research Conference (NL, '03). Retrieved October 22, 2012. Retrieved from http://www.stockburger.at/files/2010/04/gameinvironment_stockburger1.pdf

Takagi, T. (2006). Crimson Room. [Online Game], New York: Viacom New Media, played 5 July, 2013.

TiM. (2000). Mudsplat. Paris: Université Pierre et Marie Curie.

Tinwell, A., Grimshaw, M., & Williams, A. (2010). Uncanny behaviour in survival horror games. Journal of Gaming and Virtual Worlds, 2 (1): 3-25.

Toop, T. (2010) Sinister Resonance: The Mediumship of the Listener. England: Continuum Pub Group.

Zorn, J (2002). Cobra. USA: Tzadik.

Zorn, J (2000). Lacrosse. USA: Tzadik.