“theyre all trans sharon”: Authoring Gender in Video Game Fan Fiction

by Brianna Dym, Jed Brubaker, Casey FieslerAbstract

Underrepresented fans of media, such as women, members of the LGBTQIA community, and other marginalized people use fan fiction (new narratives constructed from elements of existing media) to critique and recraft their representation in media such as television, movies, books and video games. This article explores fan response to diverse gender identities, or their absence, in video games, through stories found on the popular fan fiction website Archive of Our Own (AO3). The analysis examines metadata from over 2,200 unique fan fiction stories, focusing on freeform, user-generated tags. In addition to categorizing works, tags are also a place for authors to describe their intentions and respond to the source material. This analysis reveals that authors are recrafting video game narratives to include more diverse gender representation in a way unique to the current cultural nuances of video games. This article argues that game developers can expand diversity in games not only by adding queer characters but by leaving narrative choices and details open so that players can interpret character identities in multiple ways. By challenging the hegemonic barriers in games, the diverse communities that take place in authoring and reading fan fiction expand the boundaries of video game culture while also revealing ways that video games themselves can open the doors to greater diversity in their narratives.

Keywords: fan fiction, discourse analysis, transgender identity, LGBTQ, folksonomy, archive of our own, queer game studies

Content note: This article includes brief discussions of transphobia, homophobia, trans misogyny, and heterosexism.

Yes, in My Story They’re Trans

Video games offer a variety of experiences to their players. A game experience might focus on learning a combat system and coordinating with teammates to overcome an opposing team, it might provide a series of puzzles to overcome--or it might provide a story-driven journey controlled by the player. Often, video games mix and match these elements to present an immersive experience. Much like other forms of media, games provide players the opportunity to see themselves reflected in the narrative, particularly since players have some control over the actions of a character they portray in a game. However, this control is still limited, and not all players have the same opportunity to see themselves in games. Video game developers expand diversity in games by including diverse characters and different player mechanics, but in an industry still dominated by white, cisgender, and straight men (Paul, 2018), how do video game fans coming from those diverse backgrounds respond to representation in games?

Fan fiction communities, where writers create new narratives based on existing media, can provide a window of insight. Through video game fan fiction, these writers also respond to and reconstruct depictions of diversity within video games. Fan fiction communities, such as the popular website Archive of Our Own (AO3), therefore offer a space for video game fans to push back against different assumptions within games. The flippant statement “theyre all trans sharon” appears in the metadata of one story in this archive that re-imagines the main characters of a video game as transgender--a rhetorical move that in the context of this particular community of video game fans is nothing unusual. The sarcastic statement warns off any confused readers with a dismissive, textual wave of the hand. Of course they are trans, Sharon. Why would they be otherwise?

This comment appears in a freeform “tag” that describes and categorizes one of the many video game-based works in a fan fiction archive, where media remixes thrive. As they do on platforms like Tumblr, tags often serve as commentary in addition to categorizing function (Bourlai, 2017). This tag also pushes back against the heteronormative, hypermasculine tension surrounding the video game community. Certain disgruntled players argue that video games no longer value cisgender, straight, white male players, and that a feminist conspiracy lurks within news media and academia to negatively alter games forever (Chess & Shaw, 2015). If video games are shifting away from the stereotypical gamer, then how do groups marginalized within the gaming industry perceive that shift? While the state of racial diversity portrayed in games is still abysmal, even among independent developers (Passmore et al., 2018), a recent study from Cole et al. (2017) indicated a sharp increase in queer representation across standalone game titles in the last ten years. If representation has increased so much, then are queer players overjoyed with their new presence in the gaming market? Furthermore, does the portrayal of those queer identities speak to queer experiences, or reduce them to a token role?

Regardless of the answers, expanded representation does not benefit all queer identities equally. In the following discussion, we sometimes use “queer” to refer to non-straight sexualities and non-cisgender identities. For clarity’s sake, we will distinguish between the two as “queer sexualities” and “non-cisgender identities” -- the former represented more often within games. Cole et al.’s findings point to an overwhelming increase in gay and lesbian representation, while other queer identities, especially non-cisgender identities, remain underrepresented by comparison (2017). However, depictions of non-cisgender identities are growing more frequent in modern games, if still largely underrepresented (Shaw & Friesem, 2016). In addition to issues of underrepresentation, few online spaces offer large-scale critical feminist or queer-oriented discussions about video games. Though critical perspectives appear in venues like the video series Feminist Frequency (Sarkeesian, n.d.) and in academic game studies literature (Ruberg & Shaw, 2017), another rich source for gamer response and creative critique is video game fan fiction communities.

Historically, queer and other marginalized media fans have used fan fiction to critique or recraft how they are represented in television, books, video games and more (Jenkins, 1988; Bury, 2005). Fan fiction is the product of remixing elements of a prior published piece of media into a new text-based work, which the creator then shares among other members of an online community, or “fandom” (Coppa, 2017). Within online fandom, women and the LGBTQIA community are the most active fan fiction writers (Bacon-Smith, 1992; Centrumlumina, 2013), partly because writing fan fiction provides a way to “reclaim [their] interests from the margins of masculine texts” (Jenkins, 1988, p. 477). Commercial depictions and fan expectations surrounding marginalized identities are often misaligned. As Erica Friedman argues concerning queer women, “commercial publishers sell to nonlesbian audiences; researchers seek to codify from a distance; and fans want stories of their own fantasies and realities” (2017, para 5.3).

Therefore, fan fiction can provide insight into how players from marginalized backgrounds respond to and critique different video game design choices and narrative elements. In this article, we examine the popular fan fiction site AO3 as a space that amplifies the voices of marginalized and minority video game fans. We find rich discussion of the video games those stories critique as well as fan reactions to misrepresentations in video games.

Marginalization and Diversity in Video Games

Because of this struggle, the queer authorship practices we examine sit in contrast to a broader gaming culture. Minority gamers face hardships ranging from bullying that targets women and queer people (Ballard and Welch, 2015; Massanari, 2017) to cooperative online gaming spaces reinforcing sexist narratives (Stone et al., 2013). Gaming also becomes a way for players to enact not only masculinity, but also a specific brand of masculinity that is defined by what it is not--queer or feminine (Healey, 2016). As such, the stereotypical gamer may perceive any moves to introduce queer or feminine elements into gamer culture as a threat to the state of video games. This tension marks a clear divide in gaming culture between a hypermasculine narrative at risk of being displaced and the struggle of minority players to find themselves in games.

However, finding oneself in a game can be important for players. For example, designing and naming an avatar can create a safe space for players to explore gender (Crenshaw & Nardi, 2014). Prior work in game studies posited that the relationship between player and main character is so strong that players are participating in “transgender play” when a male player controls a female character and vice versa, though players often have much different understandings of their relationship with the controlled character (Kinder, 1993; Kennedy, 2002). As Esther MacCallum-Stewart states, “Considerable evidence suggests that players (especially male ones) will happily cross-gender, and do so for a variety of reasons that have little to do with sexuality, appropriation or gender preference” (MacCaullum-Stewart, 2014, para. 23; c.f., Yee, 2006; MacCallum-Stewart, 2008; Lou et al., 2013). A number of factors, including the strength of a narrative, how important character interaction is, and how a player is expected to engage with the game will frame what a player expects from representation and how they will value it against other competing factors (Shaw, 2015).

These findings do not suggest that diversity in games does not matter. Rather, they prompt further discussion to determine when and how diversity is important in games. Asking whether or not diverse representation is present in a game stops short of understanding how that representation matters. A transgender character that misrepresents transgender people may cause more damage than no representation at all. The gaming industry is still very much a straight, cisgender, male-dominated space (Paul, 2018). Despite best efforts, misinterpretations happen when adding diversity to media.

For example, players reacted harshly to the presentation of the transgender character Hainly Abrams within Bioware’s 2017 game Mass Effect: Andromeda. Briefly after meeting the player character, Abrams discloses her “deadname,” or her name before transitioning (Pettigrew, 2016). Fans stated that this depiction of transgender identity was unrealistic to the transgender experience, and a later patch in the game revised the dialogue to no longer explicitly disclose the character’s transgender identity (Chalk, 2017).

For people affected by misinterpretations like this, fan fiction can be a form of recovery, a way to reclaim and reimagine games. Fans write fan fiction for many types of video games, even those which do not have rich narratives (Rambusch et al., 2009). Fan fiction can be written in response to any part of a video game, including the fallibility of technology itself (Crawford, 2017). For this analysis, we engage with fan fiction as a tool fans use to rewrite or expand on narratives and characters that are presented by game developers as queer. Fan scholars consistently demonstrate that fan fiction communities are a safe space for minority and marginalized voices to explore new interpretations of masculine and heterocentric media (De Kosnik, 2016; Derecho, 2006; Isaksson, 2014; Jones, 2014; Lackner et al., 2006; Strauch, 2017; Willis, 2006). These communities also provide a space for fans to heal from critical misinterpretations of queer experiences (Ng, 2017).

Archive of Our Own

For many video game fans, fan fiction provides an opportunity to critique a game by rewriting or expanding on its different elements. To better understand what people are critiquing, we examined metadata from the video game fan fiction on AO3, a popular, fan-run fan fiction archive. AO3 is a rich site for observing voices usually marginalized in online spaces because of its inception as a feminist response to male-dominated online spaces (Fiesler et al., 2016), and because of its status as a queer archive that draws the LGBTQIA community in to develop content that reflects and celebrates queer interpretations of media (De Kosnik, 2016).

As of July 2018, AO3 has over 1.5 million registered users and over 4 million fan works archived. The video game section hosts hundreds of thousands of entries about games ranging from small and independent works to large, multi-million dollar games (AAA titles). While the stories range from 100-word flash fictions to novel-length epics, the metadata for each entry can concisely provide insight into what the author considers most important about their story. AO3 writers and readers utilize a user-generated content labeling and organizational system, a “folksonomy” (Trant, 2009) that grew out of user needs (Bullard, 2016; Fiesler et al., 2016). AO3 categorizes stories based on relationship types (male/ female, male/ male, female/ female, other, multi, or general), provides content rating (general, teen, mature and explicit), and features an archive warning for material readers might find troubling (such as extreme gore or violence).

In addition to these required tags, authors tag elements of the story including major relationships, plot elements, and characters in a freeform tagging section that often become part of a “curated folksonomy” (Bullard, 2016) to help readers find stories with elements that matter the most to them. Site volunteers, or “tag wranglers,” develop and maintain the curated folksonomy that ties freeform tags supplied by the authors to a related parent tag. The content in the story tags provides unique data for analysis, with tags representing themes and characters from the story that an author chooses to highlight for readers. A study of archive users found that the freeform tag structure, which does not privilege certain terms or categories over others, helps with a sense of inclusivity; for example, there are not constraints on how an author can describe a character’s identity in tags (Fiesler et al., 2016).

While tags provide categorization, authors also use them to speak to their readers and make personal comments about their stories, much like comment-based tags found on Tumblr (Bourlai, 2017). Though the tagging space on AO3 is relatively unconstrained, site users demonstrate selective habits around what becomes a comment in the tags, with few users opting to put more than a couple conversational tags in an entry (Bullard, 2016). Using this rationale, we can determine that whatever authors choose to comment on within tags holds significance to the author. For example, an author writes in their tagging section for a story about the game Dragon Age: Inquisition (Bioware, 2014), “Male Inquisitor, Misgendering, my inquisitor is trans and is with Cullen.” With these tags, the author is communicating information about both their character’s gender identity and their romantic relationship. In the tags for a fan fiction about Life is Strange, (Dontnod Entertainment, 2015) another author writes: “Genderfluid Character, Road Trips, in which Rachel is astute AF and knows Chloe too well, in which Chloe buys her first pair of boxers.” Tags like these offer criticism and praise regarding diversity in games through focused statements that hone in on what matters most to that fan.

Methods for Observing Tags as Queer Spaces

This research began with the intent to further understand how queer players react to and interpret representation of queerness in video games as represented through fan fiction. We scraped fan fiction metadata from stories posted in the video game category on AO3, taking steps to minimize burden on AO3’s servers and abiding by AO3’s guidelines for researchers. To respect authors’ privacy and minimize risk of unanticipated exposure to archive users (Busse & Hellekson, 2012), we only gathered publicly viewable entries. Though this means that we may be missing content in our dataset (as AO3 allows users to “lock” stories so they are only viewable to logged-in users), we felt that the ethical considerations were more important. Additionally, in this article we do not provide links

to fan works or include author information from archive entries. Despite the delicate nature of privacy concerns on AO3, its population grants unique affordances making it an ideal site of research.

Non-cisgender identities receive the least official representation in games and are most often depicted in explicitly harmful or malicious ways (Cole et al., 2017; LGBTQ Games Archive). Similarly, stories featuring characters with non-cisgender identities are the least common occurring queer narratives on AO3 (see Table 1). To better understand this underrepresented area, we focused our analysis on authoring non-cisgender identities on AO3, allowing for a qualitative examination of how people craft gender identity through their own narratives. Through this data, we also explored how people react to narratives about gender identity in video games and what design choices they critique through rewriting these narratives.

Our complete dataset contains metadata for 402,084 unique fan fictions, including story ratings, summaries, statistics on hits and comments, and tags provided by the author. We conducted iterative, open coding on the data to identify common tags and keywords related to non-cisgender identities (e.g., “trans”, “non-binary”) and sexualities (e.g., “lesbian”, “bisexual”), and then filtered the data set using those keywords. Table 1 displays the most commonly occurring keywords (n > 30) from our dataset. We also filtered for common misspellings and slang variations on these identifiers to ensure they were included in the dataset. While our analysis targets non-cisgender identities, we counted tag usage for the sexualities gay, lesbian, and bisexual in order to compare their frequency with gender identity tags across AO3. Table 1 shows that tags for non-cisgender identities are the least commonly occurring keywords about queer identity within video game fan fiction. Both fan fiction authors and scholarship about queerness in games engage with gender identity less than other queer identities. However, the unique tagging practices we saw around recrafting gender identity in fan fiction motivated us to investigate further.

Terms for Queerness in Fan Fiction

| Term | Frequency (count of word usage in dataset) |

|---|---|

| "gay" | 9,323 |

| "lesbian" | 3,190 |

| "nonbinary"/"non-binary" | 2,082 |

| "bisexual" | 1,868 |

| "trans male" | 1,531 |

| "queer" | 969 |

| "agender" | 589 |

| "trans female" | 517 |

| "transgender" | 423 |

| "genderfluid" | 377 |

| "gender dysphoria" | 189 |

| "genderqueer" | 177 |

| "intersex" | 162 |

| "bigender" | 33 |

Table 1. Frequencies for queer terms across the dataset of 402,084 fan fictions

To focus our inquiry, we started by identifying video game fandoms for further analysis. Fandoms were included if: (1) the video game demonstrated a history of purposefully engaging with LGBTQIA identities (as determined by the LGBTQ Game Archive and Queerly Represent Me’s discussion of the game); (2) if the fandom contained more than 50 fan fictions tagged with non-cisgender identities; and (3) multiple authors had contributed such stories to the given fandom. These criteria allowed us to target the areas of fandom where the most people were writing about non-cisgender identities while also critiquing different portrayals of queerness in games (see Table 2).

Based on these criteria, the video games we analyzed share the following characteristics: they are all western, they emphasize strong narrative arcs or develop story for characters, and most have strong role-playing game elements. The demographics of AO3, which is overwhelmingly comprised of western, white users typically in their twenties, most of whom identify as female and/ or queer (Centrumlumina, 2013), likely inform these characteristics. In addition to the site users shaping our data, this framework for analysis also excludes games that do not engage with LGBTQIA representation. Interestingly, though there are many games in the databases that negatively portray non-cisgender identities or misconstrue those identities as a problem, we found little to no fan fiction engaging with these depictions or correcting them.

Video Game Fandoms Analyzed

| Fandom | Archive Entries | Non-cisgender Entries | LGBTQ Game Archive & Queerly Represent Me Notes on Gender Diversity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dragon Age series | 51,408 | 527 (1.03%) | In Dragon Age 2, the character “Serendipity” is played off as a drag queen, but creators have since stated the character is problematic. Maevaris Tilani is a hero in the phone game and comics that is presented as a transgender woman. “Krem” in Dragon Age: Inquisition is presented as a transgender man (LGBTQ Game Archive) |

| Overwatch | 19,158 | 527 (664 (3.46%) | Overwatch’s characters are “varied and unique” in their gender presentation, allowing players a wide range of options to choose from in character appearance (Queerly Represent Me) |

| Undertale | 18,391 | 182 (0.98%) | In Dragon Age 2, the character “Serendipity” is played off as a drag queen, but creators have since stated the character is problematic. Maevaris Tilani is a hero in the phone game and comics that is presented as a transgender woman. “Krem” in Dragon Age: Inquisition is presented as a transgender man (LGBTQ Game Archive) |

| Dragon Age series | 51,408 | 527 (1.03%) | The player character is referred to with they/ them pronouns throughout Undertale, as are other characters (LGBTQ Game Archive) |

| Mass Effect series | 16,697 | 139 (0.83%) | In Mass Effect: Andromeda, “Hainly Abrams” is presented as a transgender woman, though her interaction with the player character was revised. The alien race the asari are also given more nuanced gender expressions over the course of the series (Queerly Represent Me) |

| Fallout series | 8,933 | 215 (2.41%) | Fallout 4 no longer genders equipment such as clothing, and the character KL-E-O discusses identity in a way considered similar to transgender experiences (Queerly Represent Me) |

| Assassin’s Creed series | 6,128 | 87 (1.42%) | Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate - “Ned Wynert” is presented as a transgender man (LGBTQ Game Archive) |

| Elder Scrolls series | 4,704 | 58 (1.23%) | Series characters Deadric Lords are depicted as intersex or agender and Argonian sexual development is described as a gender nonconforming process (LGBTQ Game Archive) |

| Borderlands series | 3,407 | 54 (1.84%) | Series character “Chloe Price” is considered by some fans to be bigender or genderfluid, a theory endorsed by the character’s voice actor Ashly Burch (Queerly Represent Me) |

| Dream Daddy: A Dad Dating Simulator | 936 | 226 (24.15%) | The player character may present as transgender through the choice of a “binder bod”. “Damien Bloodmarch” is transgender (Queerly Represent Me) |

Table 2. Games for which an in-depth analysis was performed, including count of total and non-cisgender entries. Notes about gender representation in each game from different game archives are provided.

In order to further focus on writers engaging with gender identity, we only examined fan fiction metadata that contained a character identified as some non-cisgender identity or an author tag related to a non-cisgender identity (see Table 1). While these keywords helped identify games that we should look at metadata from, two researchers read each entry from those games to ensure we captured data that might speak to themes around gender identity.

Our final dataset consisted of the metadata from 2,279 archive entries. Drawing from discourse analysis techniques (Gee, 2014), we conducted a thematic analysis to explore emergent themes in the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). We identified three major ways in which writers interacted with video game narratives and queerness within fan fiction metadata. Firstly, writers reconstruct different gender identities to expand or reclaim narrative space. Secondly, player character gender identity is often rewritten to encompass a gender spectrum broader than the “male/ female” binary. Thirdly, writers use tags to respond to specific game developers and design choices. All of these actions critique the current state of non-cisgender identities as they are represented (or not represented) within video games.

Rewriting the Narrative

AAA video games do not feature characters with non-cisgender identities as prominently or as positively in comparison to characters with queer sexualities. Within the Dragon Age universe, a series usually lauded for its depiction of queer characters (Shaw & Friesem, 2016), the only transgender woman appears in a mobile game and her identity is only critically discussed in a comic book separate from the games. Her trans male counterpart, Cremisius “Krem” Aclassi, has been described as a “rare example” among depictions of transgender men (Shaw & Friesem, 2016). He plays a supporting character role in Dragon Age: Inquisition (Bioware, 2014), in which he discusses his gender identity with the player character. While developers designed Krem’s character thoughtfully, players still rewrite opportunities to interact with Krem in ways that the game did not originally allow. Dragon Age: Inquisition is an example of a game that does include transgender characters, but these characters are not an integral part of the story’s plot. Fan fiction for games such as this one often rewrites or expands on the roles of transgender characters in the games. In the case of Dragon Age, players will also frequently rewrite their player character as transgender, non-binary, or genderqueer, signposting these identities in the stories’ tags.

Currently, the only game with a wide-reaching audience that allows a person to play explicitly as a transgender character or become romantically involved with a transgender character is Dream Daddy: A Dad Dating Simulator (Game Grumps, 2017). While not a big-budget AAA game, Dream Daddy achieved wider recognition than most independent, small-budget games get, and as a result affected a broader gaming audience than most independent titles. Dream Daddy features a trans male romance option, Damian Bloodmarch, who discloses his identity through character dialogue late into his romantic arc. The game also allows the player to code their male character as trans by selecting a “binder” (a common article of clothing for transgender men) to wear in the character creation menu. Out of 936 Dream Daddy entries on AO3, 226 of those feature stories about non-cisgender identities, making up over 24 percent of the game’s archive entries, an overwhelming percentage compared to other fandoms. In comparison, the Borderlands series is the next closest category with its non-cisgender fan fiction at 3.73 percent. The presence of more fine-grained-choice around gender identity seems to have encouraged writers to engage with gender identity much more than in other game fandoms.

While Dream Daddy is a positive step for media depictions of transgender men, representation of transgender women and other non-cisgender identities still lags behind. For example, the majority of stories about transgender women in AO3 are rewrites of cisgender characters. Where there is no adequate representation, our findings suggest that people author their own. Within fan fiction that relates to the Dragon Age franchise, for example, a popular tag is “Trans Inquisitor,” which is used to signal that the player character, the Inquisitor, is transgender. Usually, clarification accompanies this tag: “trans female character” or “trans male character.” In one instance, an author writes about the character’s identity shift within a tag: “Male Trevelyan (sort of but not really; just until she realizes she's not a he).” Another author takes cisgender, straight female characters from the Mass Effect franchise and uses tags to communicate both their gender identities and sexuality: “trans Miranda, Genderqueer Jack, they’re just in love ok.”

When the character already identifies as transgender within the game, writers use the wrangled tag “Canon Trans Character” (which appears across Dragon Age, Assassin’s Creed, and Dream Daddy entries 144 times) to indicate their story contains content about transgender identity that is canon to the game. Writers will also tag the same characters with generic tags like “Trans Character” or “Trans Male Character.” These tags ensure that readers searching the archive can find representation they might not otherwise be aware of or filter out archive entries that do not engage with queer identities.

As is common in Overwatch, authors also use tags to identify non-canon transgender characters. Within these tags, authors often talk about their decisions to rewrite these characters. One author provides the following rationale in a tag: “I don't know of any Transgender characters in [this game] and I wanted to change that.” Some game characters inspire multiple authors to rewrite that same character as a specific non-cisgender identity. For example, Rhys, the player character from Tales from the Borderlands (Telltale Games, 2014), presents as male. However, some of the gaming community rewrites Rhys as a transgender man. Authors justify the rewrite with the character’s tattoos, which resemble tattoos found on the game’s all-female warriors known as “sirens.” As a result, authors tag “Trans Rhys” and “Siren Rhys” together. Fans also adopt a similar perspective for the character Mettaton from Undertale (Toby Fox, 2015). In the game, Mettaton starts out as a ghost, and is then given a corporeal form. His house, which has feminine-coded decorations, leads fans to regularly tag the character as “Trans Mettaton.” Both characters signify a moment in games in which fans are able to build on seemingly throwaway details to insert queer representation. Both Undertale and the Borderlands series do not shy away from diversity in their games and already incorporate queer themes. However, there is no maximum threshold for representation. These character details allow players even more opportunities to find the representation they want to see in video games.

It is well-known that fandomts often take miniscule details and run with them to craft alternative narratives, especially when inserting queerness into those narratives (Jenkins, 1988). However, authors commonly recraft canonically cisgender characters as transgender without making significant changes to a game’s narrative. Authors will also regularly acknowledge that they wrote Rhys as a transgender man, even when nothing else in the story would indicate this detail to the reader: “Trans rhys is implied because that's my headcanon and i'll take it to my grave”; “Trans Rhys, it's not mentioned but he's trans in the AU”; “trans!Rhys AU...uh yeah that's it im just a sap for trans rhys”; and “Also there's only like one thing barely implying it in this but you should know I wrote this with Trans Rhys in mind.” This sort of explanation is not unique to Rhys. Authors of fan fiction for other games also clarify that they had written a transgender character, even though nothing in the game’s story suggests that the character might be transgender. The author of one story about the Dragon Age series used this tag: “garrett is also trans but isn't specified in here.” Another author, writing about >Undertale“Trans Mettaton, FTM Mettaton, It's only mentioned but still.” These tagging practices critique the concept of gender identity as a seamless presentation of either “male” or “female.” For these writers, being transgender is unique and inseparable from the lived experiences that define it.

Some authors even use tags to disclose their own gender identity in relation to the characters. Fan fiction entries from Dream Daddy: A Dad Dating Simulator often contained tags like, “Trans Author Writing Trans Character,” “Trans Writer,” or “mlm writer.” This practice is most common within fan fiction about Dream Daddy. Disclosures about gender identity almost never appear in the other video game fandoms we examined. In general, fans are protective of their identities. The “worst fannish sin” is to out someone as a fellow fan participating in online fandom (Busse & Hellekson, 2012). The fact that the authors of stories about Dream Daddy share information about their identities suggests that there is something unique about Dream Daddy. In the case of Dream Daddy, fans use these tags to stake a claim on a narrative. The canon transgender characters of Dream Daddy become a space for trans writers to reclaim identities for transgender men. In comparison, one author discloses, “cis female writer trying her best” in a tag for a story about the transgender character Damien Bloodmarch from Dream Daddy.

The Gender Binary Is Not Enough

The range of gender identities and expressions is limitless, and so finding a video game that encompasses all of those experiences is a tall order. Instead, fans pick up and expand on video games’ limited gender expression through their works. Writers tag characters as non-binary, agender, genderqueer, and bigender, among other identities. Authors frequently revise the player characters that have the choice between male or female, such as Hawke from Dragon Age II, to be non-binary or agender. Among the games we analyzed, authors took more liberties altering the player character’s gender identity than they did non-playable characters. The player character in Undertale, for example, is gender-ambiguous throughout the game. The player can interpret the character’s gender identity as they wish. Fans frequently tag this character, Frisk, as different gender identities, such as, “Nonbinary Frisk,” “Genderless Frisk,” or “Agender Frisk.” These rewrites are distinguishable from instances when authors present a character with gender-neutral pronouns to allow the reader a free interpretation of their gender. Admittedly, in the case of Undertale, it can sometimes be difficult to understand if the writer is also allowing the player to interpret the character’s identity as the game does, or if they are authoring the character with a specific non-cisgender identity.

Writers will often actively enforce their character’s gender identiaty within tags to distinguish these identities from something ambiguous: “agender [player character], [My character] doesn't like being referred to as Female but i have to work with what i'm given for tags.” This comment refers to character tags preceding the freeform tagging section that typically look like “male main character” or “female main character.” The archive utilizes these specific tags to separate different types of player characters. If a video game only allows for “male” or “female” player characters, then AO3 is far less likely to generate an official, curated tag to represent that gender identity. In the example above, the author uses a freeform tag to clarify their character’s gender identity beyond the game’s default choices.

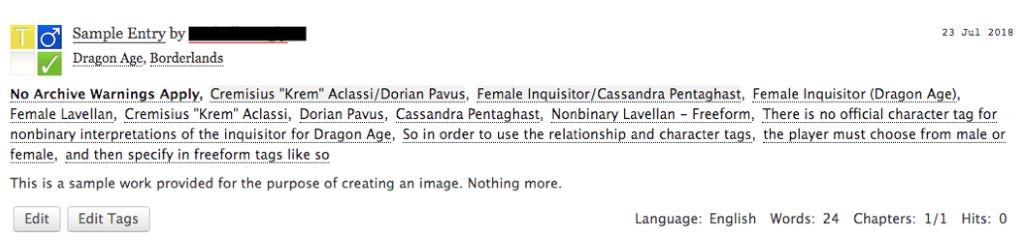

Figure 1: The image displays a sample story entry generated on AO3.

Figure 1 displays a sample of what that entry might look like on AO3. After the story title, author name, and listed fandoms (the source material) come tags generated by the writer. Some tags are auto-generated or are assisted by AO3 (e.g., “No Archive Warnings Apply” comes from a required list). Character relationships and major characters are also specific tag categories, and though AO3 suggests popular ones for a fandom, the author can tag any relationship they wish to.

However, AO3 can sometimes be only as flexible as the game a story is based on. As Avery Dame has shown in work on the relationship between tagging practices and transgender identity on Tumblr, “The performance of self cannot exist independent of the social and technical classification systems that will be applied to it” (Dame, 2016, p. 35). In other words, if a non-binary character is not already present in a video game, the tagging framework within AO3’s curated folksonomy, not the freeform tags, will struggle to accommodate a person’s rewrite. In the example in Figure 1, we intended to write the player character, a non-binary Lavellan (elf), in a relationship with Cassandra Pentaghast from the Dragon Age series. Because the options “Female” or “Male” were only available for Lavellan in the relationship and character tags, we tagged “Nonbinary Lavellan” after the fact. AO3’s system allows this, which is an improvement over most tagging systems (Fiesler et al., 2016). However, this tagging option remains limiting, since it can only be a “freeform” tag.

Authors push against this barrier in their own freeform tags. One author asks in a freeform tag, “how do I tag nonbinary Lavellan in a romance with Solas” while other authors make new freeform tags that express the romantic pairing without gendered language attached. Rejecting the male/female binary, writers emphasize player character pronoun choice through the tagging system in addition to labeling their character’s gender identity. Examples of tags that function in this way include: “they/them pronouns used to refer to my [character]” and “Non-binary [character], they/them pronouns.” Writers also discuss the difficulties surrounding gender identity, such as in the following tag: “gender matters, slight non-malicious misgendering, that is corrected, positive reinforcement.” In this example, the author is warning their audience that misgendering occurs in the story, which can be a difficult topic for people that are coming out. While the author identifies that misgendering happens, they also disclose that positive interactions happen around it. Much like this tag, many tags in AO3 act as a space for conversation around gender identity and navigating the social hardships surrounding non-cisgender identities.

In addition to discussing themes around gender identity, authors also use these tags to enforce different interpretations of characters that game developers might encourage after a game’s release. Chloe Price from Life Is Strange (Dontnod Entertainment, 2015) is frequently reimagined as bigender or genderfluid. Many authors use the “bigender!Chloe” or “Genderfluid Chloe” tag due to her androgynous character design and an endorsement from the voice actor, who stated in an interview that she thinks of Chloe as fluid in both her sexuality and gender (Sloane, 2016). Within the Life is Strange fan community, both fans and someone from the video game’s official team agreed on a more nuanced interpretation of the character. Similarly, Gearbox CEO Randy Pitchford considers the Borderlands series character Zer0 to be either agender or non-binary, much like how fans rewrote them: “Zer0 (Borderlands), Gender-Neutral Pronouns”, “Rewrite, nonbinary!zer0.” Even with agreement from officials, these tags signify rewrites by fans and talk back to game developers and even other people within a fandom.

Talking Back in Tags

Writers use freeform tags to talk back at both specific choices video games make about representing gender identity as well as perceptions surrounding gender within a broader community. We noticed three trends among tags that addressed an audience. Firstly, writers used hyperbolic or sarcastic statements as a form of critique. Secondly, writers disclosed that they personally related to a character and their struggles. Thirdly, writers disclosed when their own identity aligned with the characters they were writing about.

Satirical and hyperbolic comments point to iterative misinterpretations of gender identity embodied by traditional video game design. Tags like “everyone is trans i don’t make the rules (except i do),” “Basically, everyone is neurodivergent/trans/gay, and everything hurts,” and “trans original character, gays... gays everywhere” make universal claims to a space normally denied to those existing outside of heteronormative game designs. Writers might make a generalization, such as “all my inquisitors are trans,” or critique a specific way transgender identity is represented, as in the tag “No angst over the trans thing too bc thats overdone, world needs more unapologetic happy trans sex.” Sometimes, writers responded directly to the game studio in tags: “Bioware can eat my entire ass.” When game studios engaged less directly with queer diversity, such as in the case of Blizzard’s attitude toward Overwatch, writers often used sarcastic statements to challenge other fans that might critique their rewrite: “if somebody tells me i can't make them gay and trans in 1868, but magic dragon tattoos are fine then, i am going to eat their keyboard.” Statements like, “trans!zenyatta, dont ask how robots are trans im a writer it can happen” and “i headcannon outertale sans as trans and this story focuses on him ok” point to imagined nay-sayers lurking in the comments.

However, not all tags of this sort are critical of games. In the case of Dream Daddy, fan fiction writers used these tags to express their approval of the game: “damien bloodmarch is trans and i am LIVING, what a great game” and “I love Damien so much, protect the smol bean, I'm so glad this is canon Well my writing isn't the trans part is.” The comments highlight something from the game that writers liked: Damien’s transgender identity. Overall, our findings suggest that fans respond well when game developers make the effort to incorporate diverse characters into well-rounded stories. When authors made critical statements about transgender identity in games, they sometimes focused on the lack of representation available, such as in comments like, “my dude theres like a handful of fics on here with trans characters so, i made one :/,” “As a trans guy I feel like we could always use more people to relate to.” These conversational tags are speaking to other writers and readers on AO3. In this example, writers are encouraging the development of more queer content.

Creating Space for More Fans

Even if the fan fiction on AO3 does not directly influence industry practices, the stories there provide critical discussion concerning topics less often explored in video games and the game industry. Fans have long used fan fiction to reimagine themselves in media. As we have demonstrated, fan fiction can also be used to expand narrative spaces in an attempt to make them more welcoming. The fan fictions around the video games that we have discussed represent epicenters of critical conversations that push at the boundaries of diversity in games and in broader gaming communities. Authors took advantage of the nuances that articulated character gender identity in Dream Daddy and created a vibrant space for writing about trans identity. The small details provided by the game developers provided a significant payoff for players. In other instances, fans found different routes to broadening diversity. In the case of Overwatch, authors rewrote many characters as different gender identities rather than adopting specific readings for a select few characters. In the case of Chloe Price from Life is Strange and Zer0 from Borderlands 2 (Gearbox Software, 2012), players drew inspiration from comments made by people involved in the game development process to establish a character interpretation outside of the default assumption.

Video games will never satisfy fans’ desire for diversity with a magical number of token characters. While developers should continue to move toward providing diverse characters in games, they can also provide more opportunities for fans by leaving characters open to interpretation. In the case of Borderlands, authors rewrite Rhys as transgender widely across the fan community because nothing in the game narrative strictly denies this interpretation of the character. In addition to designing for multiple interpretations, developers can help fans craft more complex narratives by including character options that speak to more diverse gender identities. As is demonstrated in Dream Daddy, meaningful design choices can be as small as letting a character wear a binder instead of a tank top. While developers are making strides to improve diversity in games, there is still much to be done.

Fan fiction communities remain an under-explored area for video game research, even in the field of queer game studies. Fan fiction communities have long been a safe space for people when a narrative misinterprets them or pushes their identity to the margins. While this analysis emphasizes those who write fan fiction, further research could also consider those who read fan fiction as a way to see themselves in narratives that have excluded or misrepresented them. Readers need to see themselves rewritten into narratives as much as writers need to reclaim and reconstruct their own narrative spaces.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Anthony Pinter for programming the web scraper we used toacquire our data. We would also like to thank Ellie, who discussed early insights into the data with us. We would also like to thank the rest of our research labs for their feedback and support.

References

Bacon-Smith, C. (1992). Enterprising women: Television fandom and the creation of popular myth. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Ballard, M. E., & Welch, K. M. (2015). Virtual warfare: Cyberbullying and cyber-victimization in MMOG play. Games and Culture, 1555412015592473.

Bourlai, E. E. (2017). ‘Comments in Tags, Please!’: Tagging practices on Tumblr. Discourse, Context & Media.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

Bullard, J. (2016, November). Motivating invisible contributions: framing volunteer classification design in a fanfiction repository. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Supporting Group Work (pp. 181-193). ACM.

Bury, R. (2005). Cyberspaces of their own: Female fandoms online. Peter Lang.

Busse, K., & Hellekson, K. (2012). Identity, ethics, and fan privacy. Fan Culture: Theory/Practice, 38.

Centrumlumina. (2013, October 05). AO3 Census: Masterpost. Retrieved December 27, 2017, from centrumlumina.tumblr.com/post/63208278796/ao3-census-masterpost

Chalk, A. (2017, April 05). BioWare apologizes for Mass Effect: Andromeda's Hainly Abrams character. Retrieved December 27, 2017, from www.pcgamer.com/bioware-apologizes-for-mass-effect-andromedas-hainly-abrams-character/

Chess, S., & Shaw, A. (2015). A conspiracy of fishes, or, how we learned to stop worrying about #GamerGate and embrace hegemonic masculinity. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 59(1), 208-220.

Cole, A. (2016, May 1). Queerly Represent Me | QueerlyRepresent.me. Retrieved December 27, 2017, from https://queerlyrepresent.me/

Cole, A. M., Shaw, A., & Zammit, J. (2017). Representations of queer identity in games from 2013-2015. In Proceedings of DiGRA 2017 International Conference (pp. 1-5). Digital Games Research Association.

Coppa, F. (2017). The fanfiction reader: Folk tales for the digital age. University of Michigan Press.

Crawford, E. E. (2017). Glitch horror: BEN Drowned and the fallibility of technology in game fan fiction. In DiGRA Conference.

Crenshaw, N., & Nardi, B. (2014, October). What's in a name?: Naming practices in online video games. In Proceedings of the first ACM SIGCHI annual symposium on Computer-human interaction in play (pp. 67-76). ACM.

Dame, A. (2016). Making a name for yourself: Tagging as transgender ontological practice on Tumblr. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 33(1), 23-37.

De Kosnik, A. (2016). Rogue archives: Digital cultural memory and media fandom. MIT Press.

Derecho, A. (2006). Archontic literature: A definition, a history, and several theories of fan fiction. In K. Hellekson & K. Busse (Eds.). Fan Fiction and Fan Communities in the Age of the Internet: New Essays (pp. 57-75). Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

Fiesler, C., Morrison, S., & Bruckman, A. S. (2016, May). An archive of their own: A case study of feminist HCI and values in design. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 2574-2585). ACM.

Friedman, E. (2017). On defining yuri. Transformative Works and Cultures, 24.

Gee, J. P. (2014). An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method. Routledge.

Healey, G. (2016). Proving grounds: Performing masculine identities in Call of Duty: Black Ops. Game Studies, 16(2).

Isaksson, M. (2014). Negotiating contemporary romance: Twilight fan fiction. Interactions: Studies in Communication & Culture, 5(3), 351-364.

Jenkins III, H. (1988). Star Trek rerun, reread, rewritten: Fan writing as textual poaching. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 5(2), 85-107.

Jones, G. (2014). The sex lives of cult television characters. In Hellekson, K., & Busse, K. The Fan Fiction Studies Reader. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Kennedy, H. W. (2002). Lara Croft: Feminist icon or cyberbimbo? On the limits of textual analysis. Game Studies: International Journal of Computer Games Research, 2(2).

Kinder, M. (1993) Playing with power in movies, television and video games: From Muppet Babies to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. London: University Of California Press.

Lackner, E., Lucas, B. & Reid, R. (2006). Cunning linguist: The bisexual erotics of words/silence/flesh. In Hellekson, K. & Busse, K. (Eds.). Fan Fiction and Fan Communities in the Age of the Internet: New Essays. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

Lou, J. K., Park, K., Cha, M., Park, J., Lei, C. L., & Chen, K. T. (2013). “Gender Swapping and User Behaviors in Online Social Games” Paper given at the International World Wide Web Conference Committee (IW3C2). May 13-17 2013, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

MacCallum-Stewart, E. (2008). Real men carry girly epics: Normalising gender bending in online games. Eludamos, Vol 1 #2.

MacCallum-Stewart, E. (2014). “Take that, bitches!” Refiguring Lara Croft in feminist game narratives. Game Studies, 14(2).

Massanari, A. (2017). # Gamergate and the Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures. New Media & Society, 19(3), 329-346.

Ng, E. (2017). Between text, paratext, and context: Queerbaiting and the contemporary media landscape. Transformative Works and Cultures, 24.

Passmore, C. J., Birk, M. V., & Mandryk, R. L. (2018, April). The privilege of immersion: Racial and ethnic experiences, perceptions, and beliefs in digital gaming. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (p. 383). ACM.

Paul, C. A. (2018). The Toxic meritocracy of video games: Why gaming culture is the worst. University of Minnesota Press.

Pettigrew, S. (2016). Discrimination and hate crimes against the trans community.

Rambusch, J., Susi, T., Ekman, S., & Wilhelmsson, U. (2009). A literary excursion into the hidden (fan) fictional worlds of Tetris, Starcraft, and Dreamfall. In DiGRA Conference.

Ruberg, B., & Shaw, A. (2017). Queer Game Studies. University of Minnesota Press.

Sarkeesian, A. (n.d.). Feminist Frequency. Retrieved December 27, 2017, from https://feministfrequency.com/

Shaw, A. (n.d.). LGBTQ Video Game Archive. Retrieved December 27, 2017, from https://lgbtqgamearchive.com/

Shaw, A. (2015). Gaming at the edge: Sexuality and gender at the margins of gamer culture. Univ Of Minnesota Press.

Shaw, A. & Friesem, E. (2016). Where is the queerness in games? Types of lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and queer content in games. International Journal of Communication 10: 3877-3889.

Sloane. (2016, October 09). Hella talk: An interview with Ashly Burch on Chloe Price,queerness, & ‘Life Is Strange’. Retrieved December 27, 2017, from https://femhype.com/2015/10/27/hella-talk-an-interview-with-ashly-burch-on-chloe-price-queerness-life-is-strange

Stone, J. C., Kudenov, P., & Comb, T. (2013) Accumulating histories: A social practice approach to medievalism in high-fantasy MMORPGs. (pp. 107-118). In Kline, D. T. (Ed.). Digital Gaming Re-imagines the Middle Ages (Vol. 15). Routledge.

Strauch, S. (2017). Once Upon a Time in queer fandom. Transformative Works and Cultures, 24.

Trant, J. (2009). Studying social tagging and folksonomy: A review and framework. Journal of Digital Information, 10(1).

Yee, N. (2006). The demographics, motivations and derived experiences of users of massively-multiuser online graphical environments. in PRESENCE: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 15, 309-329.

Willis, I. (2006). Keeping promises to queer children: Making space for Mary Sue at Hogwarts. In Hellekson, K. & Busse, K. (Eds.). Fan Fiction and Fan Communities in the Age of the Internet: New Essays. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

Ludography

2K Australia & Gearbox Software. (2014). Borderlands: The Pre-Sequel. [Linux, Microsoft Windows, Nvidia Shield, OS X, PlayStation 3, PlayStation 4, Xbox 360, Xbox One], Canberra, Australia: 2K Games.

Bethesda Game Studios. (2002). The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind. [Microsoft Windows, Xbox], Rockville, USA: Bethesda Softworks.

Bethesda Game Studios. (2006). The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion. [Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 3, Xbox 360], Rockville, USA: Bethesda Softworks, 2K Games.

Bethesda Game Studios. (2008). Fallout 3. [Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 3, Xbox 360], Rockville, USA: Bethesda Softworks.

Bethesda Game Studios. (2011). The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim. [Microsoft Windows, Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 3, PlayStation 4, PlayStation VR, Xbox 360, Xbox One], Rockville, USA: Bethesda Softworks.

Bethesda Game Studios. (2015). Fallout 4. [Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 4, Xbox One], Rockville, USA: Bethesda Softworks.

Bethesda Softworks. (1994). The Elder Scrolls: Arena. [MS DOS], Rockville USA: Bethesda Softworks.

Bethesda Softworks. (1996). The Elder Scrolls II: Daggerfall. [MS DOS], Rockville, USA: Bethesda Softworks.

Bioware. (2007). Mass Effect. [Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 3, Xbox 360], Edmonton, Canada: Microsoft Game Studios, Electronic Arts.

Bioware. (2009). Dragon Age: Origins. [Microsoft Windows, OS X, PlayStation 3, Xbox 360], Edmonton, Canada: Electronic Arts.

Bioware. (2010). Mass Effect 2. [Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 3, Xbox 360], Edmonton, Canada: Electronic Arts.

Bioware. (2011). Dragon Age 2. [Microsoft Windows, OS X, PlayStation 3, Xbox 360], Edmonton, Canada: Electronic Arts.

Bioware. (2012). Mass Effect 3. [Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 3, Wii U, Xbox 360], Edmonton, Canada: Electronic Arts.

Bioware. (2014). Dragon Age: Inquisition. [Microsoft Windows, OS X, PlayStation 3, PlayStation 4, Xbox 360, Xbox One], Edmonton, Canada: Electronic Arts.

Bioware. (2017). Mass Effect: Andromeda. [Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 4, Xbox One], Montreal, Canada: Electronic Arts.

Blizzard Entertainment. (2016). Overwatch. [Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 4, Xbox One], Irvine, USA: Blizzard Entertainment.

Black Isle Studios. (1998). Fallout 2: A Post Nuclear Role Playing Game. [Microsoft Windows, OS X], Orange County, USA: Interplay Productions.

Capital Games. (2013). Heroes of Dragon Age. [Android, iOS], Sacramento, USA: Electronic Arts.

Deck Nine. (2017). Life is Strange: Before the Storm. [Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 4, Xbox One], Westminster USA: Square Enix.

Dontnod Entertainment. (2015). Life is Strange. [Android, iOS, Linux, Microsoft Windows, OS X, PlayStation 3, PlayStation 4, Xbox 360, Xbox One], Paris, France: Square Enix, Feral Interactive, & Black Wing Foundation.

Game Grumps. (2017). Dream Daddy: A Dad Dating Simulator. [Linux, Mac OS, Microsoft Windows]. Game Grumps.

Gearbox Software. (2009). Borderlands. [Microsoft Windows, OS X, PlayStation 3, Xbox 360], Release Frisco, USA: 2K.

Gearbox Software. (2012). Borderlands 2. [Linux, Microsoft Windows, Nvidia Shield, OS X, PlayStation 3, PlayStation Vita, PlayStation 4, Xbox 360, Xbox One], Frisco, USA: 2K Games.

Interplay Productions. (1997). Fallout: A Post Nuclear Role Playing Game. [Microsoft Windows, Mac OS, MS Dos, OS X], Los Angeles, USA: Interplay Productions.

Obsidian Entertainment. (2010). Fallout: New Vegas. [Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 3, Xbox 360], Irvine, USA: Bethesda Softworks.

Telltale Games. (2014). Tales from the Borderlands. [Android, iOS, Microsoft Windows, OS X, PlayStation 3, PlayStation 4, Xbox 360, Xbox One], San Rafael, California: Telltale Games.

Toby Fox. (2015). Undertale. [Linux, Microsoft Windows, Nintendo Switch, OS X, PlayStation 4, PlayStation Vita

Ubisoft Montreal. (2007). Assassin’s Creed. [Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 3, Xbox 360], Montreal, Canada: Ubisoft.

Ubisoft Montreal. (2009). Assassin’s Creed II. [Microsoft Windows, OS X, PlayStation 3, PlayStation 4, Xbox 360, Xbox One], Montreal, Canada: Ubisoft.

Ubisoft Montreal. (2010). Assassin’s Creed: Brotherhood. [Microsoft Windows, OS X, PlayStation 3, PlayStation 4, Xbox 360, Xbox One], Montreal, Canada: Ubisoft.

Ubisoft Montreal. (2011). Assassin’s Creed: Revelations. [Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 3, PlayStation 4, Xbox 360, Xbox One], Montreal, Canada: Ubisoft.

Ubisoft Montreal. (2012). Assassin’s Creed III. [Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 3, WiiGearbox Software. (2009). Borderlands. [Microsoft Windows, OS X, PlayStation 3, Xbox 360], Release Frisco, USA: 2K.

Ubisoft Montreal. (2013). Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag. [Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 3, PlayStation 4, Wii U, Xbox 360, Xbox One], Montreal, Canada: Ubisoft.

Ubisoft Montreal. (2014). Assassin’s Creed Unity. [Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 4, Xbox One], Montreal, Canada: Ubisoft.

Ubisoft Sofia. (2014). Assassin’s Creed Rogue. [Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 3, Xbox 360], Sofia, Bulgaria: Ubisoft.

Ubisoft Quebec. (2015). Assassin’s Creed Syndicate. [Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 4, Xbox One], Ville de Québec, Canada: Ubisoft.

Ubisoft Montreal. (2017). Assassin’s Creed Origins. [Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 4, Xbox One], Montreal, Canada: Ubisoft