Coin of Another Realm: Gaming’s Queer Economy

by Christopher GoetzAbstract

This essay explores gaming's "queer economy," joining frameworks of intimacy (affect theory and queer theory) with those of extimacy (systemic and economic analysis) in a discussion of meaning in video game play. It explores how gaming might be a special or strange consumer good that uniquely addresses (and thus queers) children, including the child that survives in adults. Video games are discussed as special consumer items in relation to queer theorist Kathryn Bond Stockton's notion of the "child queered by money" (the child made strange by its exclusion from wider economic exchange) and surrealist Roger Caillois' essay about the child's game of hiding treasure. Each interlocutor offers a way to think about video games through the coordinates of a wasteful consumption characteristic of childhood. Though gaming is, in this sense, a strange or queer economic activity that swerves away from future-oriented, consumer exchanges, gaming is simultaneously what Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter consider a key example of the immaterial labor of global empire. These ideas are discussed in relation to gaming's role in both the global exchange of goods and the hegemonic notion of heterosexual (re)productivity.

Keywords: Queer, Economy, Childhood, Kathryn Bond Stockton, Georges Bataille, Roger Caillois, Queer Growth, Shame, Empire

In her presentation at the first Queerness and Games Conference (2013), Samantha Allen offered a compelling analogy between gamer shame and queer shame. Following Eve Sedgwick and Adam Frank (1995) by drawing on psychologist Silvan Tomkins’ definition of shame as "an incomplete reduction of positive affect" (a "negative affect" that is "uniquely contingent on a previously positive affect"), Allen argues that a straight person experiencing shame due to pleasure taken in excessive or illicit gameplay (play beyond what is deemed acceptable by parental or societal standards) may feel something of the "skeletal structure" of queer shame (Allen, 2013). Allen’s talk is particularly interesting for how it bridges two seemingly incommensurate subjectivities: queerness and the aggressively competitive commercial game player (aka, "gamer"). Though the latter is often directly responsible for the former’s marginalization in online spaces, both subjects eschew what Lee Edelman (2004) identifies as the "reproductive futurism" of heterosexual culture, or the notion that, in a heteronormative world, growing up entails entering into expected societal (and familial) positions and becoming a (re)productive member of society. Although (or precisely because) queer people and gamers tend to experience marginal relationships to hegemonic power in a heterosexual world, Allen argues that queerness and gaming both signify a form of resistance to “heteronormative practices, kinship structures, and social formations” (Allen, 2013). In other words, these subjectivities are joined via an intimate framework of personal failure, and Allen articulates this merger, in part, through her own narrative about a summer of convalescent binging on Red Faction: Guerrilla (Volition, 2009) and her mother's discovery of hidden plastic bins containing women’s clothing. During Q&A, an audience member at Allen’s talk asked how money fits into the analogy of queer and gamer shame--that is, how the video game (a mass commodity) can be seen as marginal, and how playing a commercial game can be a form of resistance, when gaming occupies such a pre-eminent position in hegemonic consumer capitalism? Allen conceded that the personal/affective framework of shame is not ideally suited to discussing gaming’s wider economic role ("I guess I need to think more about money after this") (Allen, 2013). This was not a failure on Allen's part, since situating gaming within the global flow of capital was beyond the scope of her talk about queer and gamer shame. And it is not at all easy to bridge such different approaches to the study of video games. One is personal, designed around theories of affect and psychological frameworks that have already been employed across the humanities in textual analysis (be it literature, cinema, or video games). The other approach tends to treat games as one commodity among others in a totalizing global economy.

Viewing these two approaches as distinct perhaps reflects the “schism between Marxism and queer theory” that Kevin Floyd (2009) argues stems from “Foucault’s, not Marx’s, formative influence on queer theory” (p. 2). Floyd’s book addresses this schism, which persists despite the early-1990s queer studies texts Floyd identifies (such as those by Judith Butler, Eve Sedgwick, or Warner’s 1993 edited volume, Fear of a Queer Planet) that persuasively engage with social theory, making it, in Floyd’s words, “impossible any longer to account for gender without also accounting for the normalization of heterosexuality” (Floyd, 2009, p. 2). Indeed, there has been a fair amount of queer economic scholarship since the early 1990s. This scholarship both critiques and corrects Marxian elisions of queer subjectivity, from Cornwall’s (1997) identification of a normalization of heterosexuality at the root of economic theory’s foundational efficiency theorems (1997, p. 89) to Davidson’s (2012) complication of scholarly tendencies to sharply oppose queer commodification to queer community. However, the question raised by Allen’s joining of queer and gamer shame presents two additional difficulties that are, perhaps, reflective of a wider challenge facing queer game studies when money enters the picture.

First, Silvan Tomkin’s highly personal psychological framework is itself an outlier to the Foucauldian queer theory traditions that have been the focus of reconciliation within Marxist economic models. Second, games are an emergent medium and pose unique definitional problems while striding a series of resonant cultural binaries: video games are, on one hand, highly technical, mass-produced, mass-consumed commodities that are quickly updated and outmoded; and, on the other hand, playing a game is often an affectively charged, personal experience that takes place in intimate spaces over long periods of time (sometimes even across generations).

Building on Kathryn Bond Stockton’s notion of childhood’s “mysterious economy of candy” (2009, p. 57) and Roger Caillois’ essay on the “Myth of Secret Treasures in Childhood” (1942/2003), which references normal economic exchange as a point of departure, this paper considers how video games function as queer economy. That is, it considers how both purchasing and playing a game constitutes a mode of consumption that revels in loss, where values accrue in arbitrary and fantastic circuits of exchange and discovery that mock regular economic accumulation. Though childhood is viewed as a normal developmental period in Caillois’ work and problematized (made queer) in Stockton’s, both writers embrace and find critical potential in childhood’s strange occlusion from the adult economic world. Following Caillois and Stockton, who both also write about games, this paper introduces and tracks a dialectic within gaming that oscillates between superseding and being subsumed within wider economic patterns. As virtual spaces, video games are an exemplary medium for childhood’s enforced logic of delay (“not yet”). But as a major sector of the entertainment industry, they are also precariously emblematic of the shameful overextension of play into adulthood (“still…”). The following analysis explores how in both cases gaming, like childhood, represents an outside to normal, productive economic practice--an outside which many forces are actively seeking to fold back in. If play during childhood is still imagined as a protected, walled-off domain--freed from reality testing as well as demands for productivity--then video game play is a form of play that opens onto a quintessentially adult world (a multi-billion-dollar, competitive, high-stakes entertainment industry) where definitions of reality and questions of value are paramount. The extreme liminality of the video game as an artifact--one that joins child and adult, rule and fiction, code and image, work and play--is partly why games are challenging to discuss in economic frameworks.

Perhaps this is also partly the reason why scholars engaging with gaming's economic formations and effects have tended to emphasize MMO's that contain virtual economies, microcosms of real-world systems of monetary exchange (e.g., Dibbel, 2003; Yee, 2006; Castronova, 2008). Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter's Games of Empire (2009) eschews this pattern by broadly considering how all video games are part (or are even “paradigmatic”) of global empire, the key manifestation of which is “immaterial labor" or "work involving information and communication" (Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter, 2009, pp. xiv, xx). Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter historicize video games as a medium that straddles the "tectonic shift [from Fordist to post-Fordist modes of labor]," issuing "a playful promise to generations of new, upcoming post-Fordist workers--a promise of escape from the hard, soulless Fordist labor their parents or grandparents suffered into a world of digital freedom and possibility" (Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter, 2009, p. 4). But the promise of “digital freedom” is deceptive and pernicious, masking the increasing exploitation of immaterial labor, exemplified vis-á-vis gaming by Kü’s (2005) notion of “playbour,” as well as the industry’s movement towards “microtransactions” that extend the reach of economic exchange long beyond the initial purchase of a game.

This paper suggests that for perhaps the same reasons games are paradigmatic of capitalistic exchange in present-day empire, games are also strange commodities. They stretch the meaning of consumption by seeming to exceed traditional models of utility and developing an afterlife that regularly outgrows patterns of exchange found in other consumer technologies (like smartphones). Perhaps a game behaves like a commodity in its initial play-through, but repetition over time stretches its intended meanings, values, and pleasures into an intimate and personal set of associations that gradually outweigh the game’s initial status as commodity. From a Marxian perspective, this temporal stretching is a temporary inefficiency, an anomaly--perhaps even a Deleuzian “line of flight” that always ties back in to the rhizome’s wider totality (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987, p. 9). For example, Nintendo's recent release of the NES Classic Edition (2016) and Super NES Classic Edition (2017) gestures towards how gaming seems to outgrow its normal economic function, and also represents a simultaneous effort to bring that excess back into the profit loop. Player nostalgia for the games (and paraphernal materials) of their youth is epiphenomenal of this "excess," referring back to initial experiences of prolonged, affectively charged engagement with certain games.

When discussing games as a commodity, it is appropriate to think of them as queer economy. The meaning of “queer” here is less directly tied to sexuality and is more closely related to the forms of labor traded in a collaborative setting shielded from wider capitalist systems as described by Ricardo Montez (2006). Montez explains queer trade as "a mode of relation--and its psychic, spiritual, and material effects--that cannot be clearly defined in normative terms of sexuality and exchange" (Montez, 2006, p. 426). Montez's essay focuses on Keith Haring and his collaborator, LA2--both exceptionally talented artists whose collaborative works were exchanged on the basis of mutual respect and admiration. In contrast, Kathryn Bond Stockton locates a mode of relation far more commonplace (and apt for a discussion of gaming) that is queered by its refusal of "normative terms of sexuality and exchange": childhood.

Addressing the Child Queered by Money

In The Queer Child (2009), Stockton argues that, like the Oompa-Loompas in Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory (who are paid "wages in cocoa beans"), children are "queered by money":

What changes so dramatically for Anglo-American children in the early 1900s, according to all historians of childhood, is their economic role. Through labor laws, children, who were once working bodies in the labor force, cease to work for wages. How, then, are children made unique and strange by money? Among other ways, by not bringing money in the form of incomes into their families; by receiving, instead, an "allowance" from their parents; by spending money on toys and consumer choices driven by media targeted at them (and later sexually aimed at them). (Stockton, 2009, p. 38)

For Stockton, both money and sex are part of childhood's central condition of delay. Through delay, children are given "a shelter, though often incomplete, from knowledge of money," and, as a result, "labor relations take on imaginative, fantastical forms, including what one's parents do for money" (2009, pp. 222-223). Their nonproductive economic role within the family (and sole designation as consumer within wider economic relations), renders children strange. In her reading of the film Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005), Stockton argues that through candy, children spin fantastical images of labor and economic utility. This is hyperbolically literalized in Willy Wonka's factory, where, rather than the poorly lit and harsh working conditions of pre-WWI production lines, children discover a brightly colorful world where nearly everything is edible. It is "hardly an epiphany," Stockton suggests, "that children want to grasp the production of a coin they do understand: namely, candy. They want to grasp the economy of candy that early structures their intense pleasure: where they do have agency, choice, access, a measure for barter, and clear permission to over-indulge" (Stockton, 2009, p. 38). The candy children buy and quickly consume functions as a stand-in for consumption and exchange more generally. And, of course, by candy, Stockton also has in mind colorful, stimulating consumer goods like video games.

As Stockton notes, the commercial address of consumer items aimed at children often emphasizes blissfully wasteful consumption, which Stockton links to Georges Bataille's notion of "nonproductive expenditure," meaning the wasting of "money or energy or life itself--outlays that (happily) do not serve, that indeed defy, the ends of production; these would be wastings such as 'luxury,' 'mourning,' 'competitive games,' 'artistic productions,' and 'perverse sexual activity (i.e. deflected from genital finality)'" (Stockton, 2009, p. 227). These are all activities that, for Bataille, "have no end beyond themselves," and should be understood through a "principle of loss.” Writes Bataille, “In each case the accent is placed on a loss that must be as great as possible in order for that activity to take on its true meaning" (Bataille, 1985, p. 118). "Loss," in this sense, means an expenditure that does not seem to feed back into the circulation of goods, wealth, or values of wider systems of exchange--money, time, or energy that is misspent, squandered, or hidden away in miserly fashion. Stockton's queer interpretation of Bataille coalesces in her reading of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, which she describes as "Bataille for kids: children's unedited pleasure in obvious extremes of consumption and destruction" (Stockton, 2009, p. 238). In this way, Stockton aligns empty calories (over-indulgent eating for pleasure, not for nutritive gain) with Bataille's category of loss (verging on perverse destruction), and in so doing she also joins "'the child' to 'the queer'": "in this allowable economy of candy,… each child becomes a self-consuming artifact" (Stockton, 2009, pp. 238, 240). For Stockton, this sense of loss mocks reproductive futurism and helps articulate a queer resistance. But from another perspective, loss figures video games as strange commodities, as weak points in what Marx lamented as capital’s impulse to grow, its "werewolf-like hunger for surplus labour" (Bennet, 2010, p. 110; Marx, 1977, p. 353).

It must be noted that, although Stockton helps queer Bataille's notion of nonproductive expenditure, Bataille's framework already is a kind of refusal of reproductive futurism, where society both "recognizes the right to acquire, to conserve, and to consume rationally" but "excludes in principle nonproductive expenditure" (Bataille, 1985, p. 117). Indeed, David Bennet (2010) argues that Bataille's move was already a rejection of Papa Freud's "politically conservative libidinal economy," which:

produced a petit-bourgeois psyche, managing its economy of energy as a self-employed businessman must: spending only frugally, whenever possible re-investing in increased productivity, eschewing conspicuous consumption and credit--treating desire, or libidinal energy, as a relatively scarce resource, not as surplus (Bennet, 2010, p. 106).

Bataille calls for a more liberal libidinal economy, a free release of this controlled libido as destructive or wasteful spending--what Bennet simply refers to as "libidinal spending of the not-for-profit or wasteful variety" (110). From the point of view of political economy, it is significant to note that in Libidinal Economy (1993) Lyotard counters that Bataille's libidinal spending has no real oppositional power since all exchange is already libidinal--that is, driven by desire. Lyotard argues that the prevailing capitalist order is "barely interrupted by expenditure as pure loss" because such "outpourings of pulsional intensities pouring towards an alleged outside" to economic exchange are largely offset by a payment of some sort ("compensated for by a return") (1993, p. 201). For Lyotard, there really is no outside--at least not one offered by desire, since desire already underlies exchange in the most general sense. Lyotard's view of libidinal economy reconciles blissful consumption, wasteful expenditure, and the abnegation of personal responsibility with everyday, banal patterns of consumption, because, in Bennett's (2010) words "all that seems to matter to Lyotard is that desire, like money, should circulate as quickly and polyvalently as possible," with the goal being to embrace and exacerbate capital's wider impulse to grow (Bennet, 2010, p. 110).

Stockton pivots away from philosophical debates about opposing or exacerbating capitalism and instead focuses on the effects on the people caught up in these dynamics--people for whom nonproductive expenditure is enforced as the only accessible economic relation. Building on Edelman’s work, she explores the queer subjectivity that this pattern of consumption helps create by providing a strange space for growth and connections to the side of the family's expectation of heterosexual (re)productivity. In a more general sense, the claim that began this paper--that queer shame and gamer shame are both outlays of time, energy, and money deemed wasteful in terms of reproductive futurism--is an analogy that seems to align queer subjectivity with the commodity and against the heterosexual family. It echoes D'Emilio's (1993) assertion that queer subjectivity has historically depended on capital's division of labor. De'Emilio argues that the free labor system offered an alternative basis for identity formation beyond traditional familial roles, permitting "large numbers of men and women in the late twentieth-century to call themselves gay, to see themselves as part of a community of similar men and women, and to organize politically on the basis of that identity" (D'Emilio, 1993, p. 468). Gaming is an interest and an industry--one characterized by polymorphous perversity, the unchecked multiplication of pleasures, forms, and discourses--within a wider system of commodity exchange. As such it further offers a space to the side of traditional familial expectations.

Yet questions quickly emerge. What happens to this space to the side of expected or upward growth? Does it remain a personal treasure that is held back from wider circulation, or does it coalesce into queer community (or even a queer gamer community)? Is it co-opted by capital? Industry benefits most clearly when wasteful consumption is harnessed, counted, directed back into more productive exchanges. But the social forces that might depend on a certain kind and certain amount of play (those who view play itself as productive towards some culturally valued end) also seek to harness and redirect play that exceeds discernible contexts for productivity.

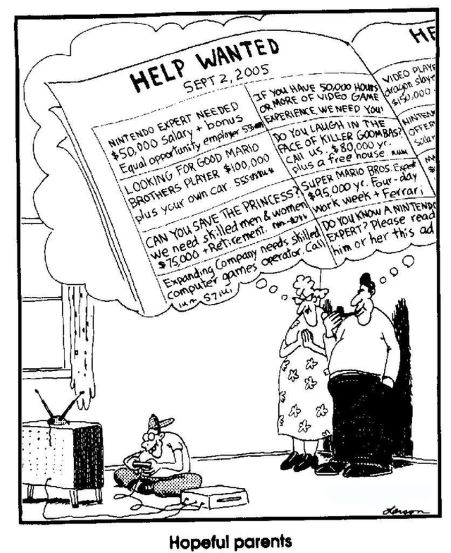

Figure 1: Figure , Gary Larson's "Hopeful parents"

Contestations over the value of time spent gaming have become crucial for cultural definitions of the medium. This dynamic can be illustrated in a 1980s Gary Larson comic [Figure 1] titled "Hopeful parents," which pokes fun at the notion that time playing games leads to career opportunities. The comic is happily invoked in articles about how "Our children's workplace will be different from ours. Their toys already reflect this difference" (Fournier, 2010), or in Reddit posts (such as JavierLoustaunau’s from 2016) marveling about Larson’s near perfect prediction of professional gaming (e-sports). However, this comic’s most radical meaning is perhaps one that embraces its original criticism--the blissful waste of time and energy that gaming represented to children in the 1980s. What does it mean that to think of gaming as a pure waste of time is, today, itself a joke?

Videogames, or the Problem of the Frivolous Adult

In her chapter in Queer Game Studies (Ruberg and Shaw, 2017), Stockton explicitly links video games to candy: games are “libidinal, captivating, repetitive, time wasting, grandly lateralizing of adults and children, and linked to the pleasures of self-destruction” (Stockton, 2017, p. 232). In particular, smartphones--“a pantry in our pockets”--feature games where “You stomp on candy, wear it, and become it; you move it on a screen. You puzzle it out” (Stockton, 2017, p. 232). Games are part of Bataille's original list of nonproductive expenditures, and Stockton's description of candy seems ready-made for a discussion of games as an economy of candy ("where [children] do have agency, choice, access, a measure for barter, and clear permission to over-indulge"). But, compared with the consumption of candy, are children's efforts to grasp a world that excludes them through delay made more or less strange through games? Are games as truly meaningful as candy in terms of loss?

After all, though strange commodities that promise dozens of hours of wasted time, games are often touted for their utility within educational contexts. Games such as Capitalism II (Enlight, 2001), Cities: Skylines (Colossal Order, 2015), and Factorio (Wube Software, 2014) even help their players imagine real-world economic conditions. And yet, because such games sometimes present plausible economic simulations (minus the experience of alienating labor), they perhaps (compared with colorful Mario games) even more closely exemplify what Games of Empire describes as gaming's deceptive utopia of post-Fordist, non-alienating labor. These games are still constructed around a central experience of pleasure, even as they also seem to broach wider concerns about the place of labor in the adult world. In this sense, even in the most fully conceived make-believe games about entering a workforce, players, like Wonka's Oompa-Loompas, "become workers by seeking their pleasure" (Stockton, 2009, pp. 240). And like Wonka, games do offer us "non-alienation of a strange sort: eat at work what you make on the job: let what you make involve your play: eat playfulness" (Stockton, 2009, pp. 240-242).

When considering gaming as an extreme and blissful loss of time (energy, money, and value), one wonders if Stockton’s allusion to smartphone games like Candy Crush Saga (2012) points us towards the best examples, since the smartphone's data-generating seepage into moments of boredom seems to exemplify the promise described in Games of Empire of immaterial labor's expansion into formerly discrete moments of private leisure. Scott Richmond (2015) refers to casual games like Candy Crush as "the expropriation of our attention, monetizing even those small moments of boredom where I might be released from desire," adding that "capitalism ruins everything" (2015, p. 35). Filling a moment of "microboredom" ("waiting in line… sitting on the toilet") (Richmond, 2015, p. 35) seems more like protecting against loss, correcting an inefficiency.

Though Richmond references Kracauer on this topic, smartphone games also seem poor examples of Kracauer's "radical boredom," a kind of surrender to one's surroundings, shut inside on a sunny day with the curtains drawn (1995, p. 334). Kracauer describes contemplating the tiny glass figures on the table, feeling "content to do nothing more than be with oneself" (p. 334). When I first read this passage in Kracauer, I was taken back to long summer afternoons when (avoiding friends who wanted to "play outside") I occupied indoor spaces and, though I wished for something new, I contented myself with non-networked Nintendo 64 games that I had already completed several times. The hours spent wandering, zoning out, curtains drawn, hardly doing anything at all--surely this was time misspent, time and energy lost. Wandering aimlessly for hours in The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (Nintendo EAD, 1998) cannot quite be "playbour" if no data is collected or transmitted. The only microtransactions that apply are temporal: moments of time slid across the floor that will never return. Such loss is different from "snacking" to keep up one's strength in line at the bank, or filling an idle moment on the train with constantly stimulating onscreen activity (moving candy around, puzzling it out, etc.) in order to cope with (or procrastinate in response to) the high demands of productivity in the modern workplace.

Playing smartphone games (especially when it is deemed opposition research) is a key example of the erosion between play and work in this postmodern world of immaterial labor. Play is no longer wasteful (and so it no longer directly evokes shame). But this is far from the only example of harnessing whatever motivates people to play video games in the first place in order to serve some wider cultural end--that is, to educate, edify, or redirect energies to solving real-world problems (cure disease, seek optimal organizational strategies, etc.). If, in other words, the pleasure of gaming were not so selfishly or wastefully pleasurable, then playing would not evoke shame; we could walk with gaming, hand-in-hand, rather than hiding it in the closet. In fact, of course, much ink has been spilled making exactly these sorts of claims about games (respectively: Gee, 2014; Bogost, 2007; Jenkins, 2007; McGonigal, 2011). In a way, these arguments countervail the notion of gaming's queer economy. Games are not candy--they're actually healthy. And when children play, they are apparently participating in a wider exchange that, in theory, benefits everyone involved.

Even when returning to the question Stockton raises about how children invent (or participate in) strange and imaginative economic worlds to compensate for an incomplete understanding of the world of commerce, it is still possible for what Brian Sutton-Smith (1997) calls a "rhetoric of play" to creep in and recuperate (i.e., normalize) what is strange or queer about childhood through a narrative of "play as progress." This narrative advocates “the notion that animals and children, but not adults, adapt and develop through their play" (Sutton-Smith, 1997, p. 9). In Sutton-Smith's definition, rhetorics (plural) "are narratives that have the intent to persuade because there is some kind of gain for those who are successful in their persuasion" (Sutton-Smith, 1997, p. 15). There is always a rhetoric around play, Sutton-Smith argues, adding that "it may be possible to show that the rhetoric itself is often the way in which the play passes into the culture, because the play practice is thus justified ideologically. In this way, the two, play and rhetoric, have an impact on each other" (1997, p. 16).

Sutton-Smith identifies seven rhetorics of play: progress, fate, power, identity, the imaginary, the self, and frivolous. The first six "exist as rhetorics of rebuttal" against a pervasive Protestant work ethic, which opposes play as a misspending of time. By opposing this deep and widespread ideology within American culture, these rhetorics seek to reshape play as time well spent. However, the last rhetoric, "play as frivolous," inverts the work ethic, becoming "not just the puritanic negative" to this ethic, but "also a term to be applied more to historical trickster figures and fools, who were once the central and carnivalesque persons who enacted playful protest against the orders of the ordained world" (1997, p. 11). The reference to the carnivalesque here hints at the marginality of the last rhetoric and the ephemerality of its inversions. Sutton-Smith positions it last among the rhetorics of play in his comprehensive analysis because of "its largely reflexive character, as commentary on all the other rhetorics," (p. 11). The rhetoric of play as frivolous, far from directly overthrowing the foundational values of the prevailing capitalist order (p. 11), has a guerrilla nature.

Following Stockton's lead (and thinking of nonproductive expenditure as a key rhetoric of play as frivolous), one might say that the first six cultural rhetorics of play do to actual play what rhetorics of the child do to actual children: they create a situation of unacknowledged sideways growth, strange values and relations. The various ways of sanctioning play for its wider cultural significance establish sanctioned forms and outcomes, denying or blocking formations that do not fit these molds. In short, they queer play. A queer economy of play would be located within this unacknowledged space--made visible only when the central virtue of work ethic (of progress, identity, power, etc.) is disbanded. When children are the focus of this question, it is difficult not to imagine some value attached to any act of play--in Lyotard's terms, some anticipated return that compensates the expenditure. The designation of a queer economy of play is complicated by the fact that capitalist exchange both frames and intersects at many points with the child's partially cordoned-off systems of trade (candy and games traded in classrooms, playgrounds, inside the private family home, etc.), so that value of some kind can return through a variety of means, overwhelming what bit is truly lost in expenditure to entropy ("as heat, as smoke, as jouissance") (Lyotard, 1993, p. 201). Loss is sharper in the domain of adulthood.

What rhetoric of progress could justify the fact that the average age of video game players is now 35 (ESA, 2017)? The paradoxical division between child and adult lies at the heart of Stockton's book (the basis of the notion of sideways growth as well as the "ghostly" gay child). It is helpful to keep in mind queerness's rejection of reproductive futurism (its refusal to "grow up" in sanctioned ways) when thinking of queer economy as something defined by or through childhood, and yet engaged with largely by adults. As Samantha Allen's strategy makes clear, there is power in embracing and reorienting societal disapprobation of adults behaving like children--whether this means being a gamer or being queer, seeking pleasure instead of "responsibility." Like a rescue operation, two categories of adults are pulled back across the boundary beyond which people are generally written off as a loss, as incapable of growth or change, as not worth redeeming, as not mattering, as not having a future, and as having no shame.

Plundered Objects: Secret Treasures and Horcruxes

In "The Myth of Secret Treasures in Childhood," Roger Caillois (1942/2003) presents what I take as an alternative approach to conceiving of the economic strangeness of Stockton's child queered by money. In a previous essay, Caillois compares the figure of the miser and its "joy of pure possession" with "the sterile possession of riches held back from circulation, kept unproductive and that one prefers to destroy rather than turn into usefulness or happiness" (Caillois, as cited in Frank, 2003, p. 253). That Caillois seems to admire the miser's intense pleasure of destruction led Walter Benjamin to critique him for apparently endorsing a monopolistic economic model which "prefers to destroy its resources rather than transform them into utility or happiness'" (Benjamin, as cited in Frank, 2003, p. 253). However, in Caillois' later essay on secret treasure, "such unproductive hoarding has shed its Bataillean associations with destruction and 'expenditure'" (Frank, 2003, p. 253).

Instead, Caillois argues that a child's game of imbuing a "treasure" with psychic significance exceeding standard measures of exchange, and then hiding it (miser-like), helps found and shore up the individual: "The child tempers his spirit and is enabled to safeguard, with a little secret, the source and warrant of his future strength" (Caillois, 1942/2003, p. 261). Hiding treasures helps compensate for the child's exclusion from the affairs of adults, offering the child magical confidence and other fantastic formations in imagination. Though, for Caillois, the power of the occulted treasure is normalized in its restriction to childhood (this "future strength" implies growing up and outgrowing the need for secret hiding places), how Caillois conceives of treasure as "infinitely exceeding" the steady accumulation of everyday labor activity is especially apt to the question of a queer economy, and worth quoting at length:

Far removed from economic concerns is the concept of treasure. It is their precise negation. It belongs to the realm of the magical. It evokes an inalienable opulence, not symbols of conventional exchange. Never has treasure been composed of notes and titles. A mother calls her son her treasure. The money of a banker is only wealth. The riches residing in treasures cannot be bargained for. They heighten the spirit of the discoverer. They have to glow with every kind of fire. They may have been acquired by crime, but not by avarice. Coins may be mixed with pearls and rubies, but they must have long since lost currency and have value only as gold. Where pirates have interred their splendid plunder an adventurer finds by chance a brilliance increased by shadowy depths. This is nothing that labor can amass…. The qualities employed to obtain it are clearly opposed to … patient, regular toil…. Real treasures are not accumulated. No amount of obstinacy discovers them, no foresight expects them; they infinitely exceed the capital a life of privation and effort is able to amass. They are sudden bursts of splendor, and bestow less money than glory on the young hero who has conquered them. (Caillois, 1942/2003, p. 259)

Though "precious," the child's treasure has no exchange value (Caillois, 1942/2003, p. 255). Its value lies in its removal and subsequent occlusion from the adult world--a relation that chance sometimes helps along: "[Treasures] are often found in the gutters. It is not that they are rare, but that they are coin of another realm" (Caillois, 1942/2003, p. 255). In Caillois' account, the child destroys normal economic order by delighting not just in beholding and fixating on an object with no exchange value--an object of contemplation, an object of reverie--but also in holding the precious object back from circulation. Doing so also means holding a piece of the child's own identity in safekeeping. Keeping the treasure’s secret does not mean accruing interest or acquiring greater wealth through interest or investment; rather, the treasure’s occlusion (its mere possession) lends power in imagination (in games, in play) to “go beyond what is normally possible: it permits you to disappear at will, to paralyze from a distance, to subdue without a struggle, to read thoughts, and to be carried in an instant wherever you want to go” (Caillois, 1942/2003, p. 257). Caillois' essay always calls to mind two references from popular culture: Voldemort's hidden Horcruxes from the Harry Potter book series (itself a variant on the fable of the giant who hid his heart in the goose egg at the bottom of a well), and the video game Pikmin 2 (Nintendo EAD, 2004).

Pikmin 2 makes self-reflexively clear the relation of gaming to outside value systems. In it, Olimar and Louie arrive on an Earth-like planet from a far-off galaxy, and search through the dirt and gutters for brilliant scraps of consumer culture (bottle caps, marbles, batteries, video game controller buttons, etc.). That these objects are, to the two protagonists, clearly coin of another realm is made delightfully clear not only in the staggering monetary value attached to them (by game's end, more than the equivalent of 100 years of salary is gathered), but also through the unique names given by the Hocotate ship computer, which encounters each item for the first time: a rusted spring is a "Coiled Launcher," an old fishing bobber is an "Aquatic Mine," the head of a rubber duck is a "Paradoxical Enigma," and so on.

That the players are familiar with these consumer items is assumed (in fact, nostalgia for these discarded bits plays a large role in the pleasure of their unearthing). How else to make sense of the proliferating references and jokes about these things, such as when something conventionally valuable (e.g. an emerald-studded broach or a massive cut diamond) is deemed of equivalent worth to (and was just as difficult to acquire as) a YooHoo bottle cap? These objects exist in the game precisely because they have fallen through the cracks, surrendered to a different mode of exchange--and not one that, as in The Borrowers (Norton, 1952), is predicated on the convention that everyday objects take on strange new utility in a magically shrunken world (e.g., a sewing needle becomes a sword; thread becomes a climbing rope; a cube of sugar becomes a month's ration, etc.). The items in Pikmin 2, with the exception of special treasures dropped by boss monsters, have no utility beyond their status as treasures that are stored away in the ship's hull.

Taken as a metaphor for a queer economy of play, this game's emphasis falls not on wasteful consumption (depletion), but on narcissistic squirreling away. Video games, in this sense, are not about time, energy, interest, and money conspicuously wasted but rather saved, converted through play's long hours into the coin of another realm, coin that is not so much blissfully cashed in as left behind, or sought again later when the past becomes meaningful. Though Lyotard would mock the toothlessness of such withholding, inventing an entirely personalized value system that opposes the specie (the bread and butter) of the adult world does seem like a queer offshoot to the Oedpial narrative. A YouTube search for parents destroying their children's Xboxes reflects reproductive futurism's brutal return--as if the depicted violence and disregard for the psychic investments of children might break the spell that games seem to hold over them (like an object enchanted with dark magic, like a Horcrux) and return the child to the proper path.

Conclusion: Queer Video Game Play and a Cashless Future

Viewing games as queer economy is helpful for bridging the intimate experience of gameplay with the wider socioeconomic and cultural forces that intersect with play and therefore change it. Nintendo was, for instance, apparently not at all pleased with the unending shelf-life of Super Smash Bros. Melee (HAL Laboratory, 2001), which, though released 17 years ago, is still actively played in both casual and competitive contexts. As if having accidentally let out a truly Everlasting Gobstopper, Nintendo decided to make sure their next entry in the series--Super Smash Bros. Brawl (Game Arts and Sora Ltd., 2008) could not possibly enjoy a long life in competitive gaming circles. That is, they made sure the game would never be coin of another realm, would never facilitate dwelling more than intended, would never exceed in use value (as the industry might measure in terms of "content" and "playtime") what Nintendo gains in its exchange value. Nintendo sought to undermine the online communities that teased out glitches or quirks in Melee's complicated game engine by (with Brawl) drastically simplifying and slowing the rate of exchange, and introducing a random tripping mechanic. A game becomes coin of another realm in extreme repetition, when it becomes an object of reverie, an object of contemplation, an object that is long dead to digital game markets and thus loses (or, perhaps, "infinitely exceeds") its original exchange value. When there are no more updates, no more changes, the game can finally begin its afterlife as an enclosed universe, an object that grows stranger the more a player gets to know it.

Imagine a post-apocalyptic world in which the modes of production break down and it is no longer possible to produce or safely distribute new videogame hardware. In this world, the previous cycle's (widely circulated) console hardware allows a core group of hackers/programmers/artists to develop new software and find an audience. But they must forever work within (and grow creatively in response to) a fixed set of built-in hardware limitations. Or, better yet, imagine that the universe decided there would be no more new games; what we have is all we will ever have, and as players we must reconcile ourselves, desert-island-like, to creatively expanding the boundaries of (and forever dwelling within) the software already at our disposal. Speedrunners who invest thousands of hours into single videogames, discovering new time-saving techniques decades after a game’s release, already provide a glimpse of this expansion of a game’s afterlife. So too do memories of long summers in childhood when there was little to do (and few games to play). Fantasies of dwelling forever in a game encapsulate one major way of conceiving of gaming's queer economy, an impulse brought to any specific game which pulls it forever out of its wider, future-oriented, consumer exchanges and linear-futurist chronologies.

The recent trend towards free-to-play games represents an industry shifting, changing to incorporate whatever was economically resistant in gaming's queer economy back into the folds of its always-updating circulation of digital goods. A game like Smash Melee may become coin of another realm when its purchase (that single monetary transaction) fades from memory after a decade of regular play. Over time, and in place of exchange value, embodied competencies develop. These entail storing the game in the self, along with, it could be said, a piece of the self in the game--the game as Horcrux, hidden and left behind as a marker of self sacrificed, of loss.

With a free-to-play game, such as League of Legends (Riot Games, 2009), no money is exchanged initially, and many players will never pay any money for the game at all. In its regular updates, League implements subtle imbalances between in-game characters (“champions”), so that the metagame (the game about/within/around the game) shifts and remains engaging to a wide community of players. All the while, new skins, emotes, and champions become available for purchase with real-world money. An unending schedule of updates subtly changes play mechanics so players can never quite take ownership of the game; what was learned must, sometimes, be unlearned. Those who do not play often risk falling behind their peers. Playing means contributing to an online community whose wider activities (and in-app purchases) underlie the game’s profit model. In play, nothing goes to waste.

Today, we monetize what once had "nil" value in games: our attachments to favored characters or costumes, the development of skill and muscle memory. In a free-to-play world, wasteful expenditure is no longer sustainable since such consumption is policed and charged. What was perhaps a form of subtle economic resistance through nonproductive expenditure is now measured and billed. As a result, even parents who permit video game play are implementing security measures on their iPads so that their young children do not irresponsibly and blissfully consume to the extreme. Games may or may not be "addictive"--but developers are undeniably better today at capitalizing on player habits than in the past. A player's (temporal and fiscal) investment in-game over long periods of time is now carefully positioned to reflect social status and online credibility. The possibility of player profit has even entered the picture. Unlike Stockton’s Oompa-Loompas, popular Twitch streamers and YouTube personalities would explode if they were to consume on the spot all the bread and butter they generate for themselves at work, playing these games. Their profession reveals the extent to which gaming’s current free-to-watch and free-to-play world is constructed through immaterial labor. It is highly profitable for some. It is labor for all.

Despite this, an intimate, queer economy (that shameful pleasure that we stubbornly cling to) somehow (also) stubbornly remains. Even if queer economy can no longer easily be found in games themselves, it at least persists in our recollections of childhood, or somewhere in the desert islands and postapocalyptic wastelands we visit (literally and figuratively) when we play games. Fancifully beyond the reaches of capitalist expanse, divested of all meaningful exchange value, gaming’s coin of another realm helps characterize the life we spend playing as incommensurate with the capital we accrue during that lifetime (an affront to capitalism’s tendency to see our lives as exchange value). By embracing the time we lose, the time we waste, it might be said, we also embrace the notion of infinitely exceeding the capitalist logic of what might have been gained in “a life of privation and effort,” the value future consumers will place in what we leave behind.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge and thank both the anonymous article reviewers as well as the Game Studies special issue editors, Bo Ruberg and Amanda Phillips, for guidance and insightful feedback during the revision process. I would also like to acknowledge my past and present Queerness and Games Conference (QGCon) co-organizers, a list of kind, brilliant, and generous people that includes Dietrich "Squinky" Squinkifer, Teddy Pozo, Bo Ruberg, Chuck Roslof, Emma Kinema, Chelsea Howe, Jess Marcotte, Cameron Siebold, Zoya Street, Jasmine Aguilar, Terran Pierola, and Mattie Brice. Their hard work each year has made possible an important cultural, artistic, and intellectual event, one that both frames andinspires the ideas in this paper.

References

Allen, S. (2013). Thwarted enjoyments: queering gamer shame. Paper presented at the 1st annual meeting of the Queerness and Games Conference, Berkeley, CA. https://www.twitch.tv/videos/49465339.

Barrett, D. (2007). Waistland: a (r)evolutionary view of our weight and fitness crisis. New York: WW Nortan and Company.

Bataille, G. (1985). The Notion of Expenditure. In A. Stoekl (Ed.) Visions of excess, selected writings, 1927-1939 (A. Stoekl, Trans.). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 116-129.

Boellstorff, T. (2006). A ludicrous discipline? Ethnography and game studies. Games and Culture, 1(1): pp. 29-35.

Bogost, I. (2007). Persuasive games: the expressive power of videogames. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Caillois, R. (2001). Man, play and games (M. Barash, Trans.). Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. (Original work published in 1958; English translation 1961).

Caillois, R. (2003). The myth of secret treasures in childhood. In C. Frank (Ed.) The edge of surrealism: a Roger Caillois reader (C. Frank and C. Naish, Trans.). Durham and London: Duke University Press. pp. 254-261. (Original work published in 1942)

Castronova, E. (2008). Synthetic worlds: the business and culture of online games. University of Chicago Press.

Cubitt, S. (2016). Finite media: environmental implications of digital technologies. Duke University Press.

D'Emilio, J. (1993). "Capitalism and Gay Identity," in The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader, ed. Henry Abelove, Michèle Aina Barale, and David M. Halperin. New York, Routledge, pp. 467-476.

Dibbel, J. (2003). The unreal estate boom. Wired, 11(1). Retrieved Dec 30, 2017, from https://www.wired.com/2003/01/gaming-2/.

Dyer-Witheford, N. and de Peuter, G. (2009). Games of empire: global capitalism and video games. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

ESA. (2017). Annual report. Retrieved Jan 6, 2018, from http://www.theesa.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/EF2017_Design_FinalDigital.pdf.

Edelman, L. (2004). No future: queer theory and the death drive. Duke University Press.

Foucault, M. (1990). The History of Sexuality: An Introduction (R. Hurley, Trans.). New York: Vintage.

Fournier, Y. (2010) "Don't Judge New Toys in Yesterday's Context." NewsBlaze. <https://newsblaze.com/business/technology/don-t-judge-new-toys-in-yesterdays-context_14799/>

Frank, C. (2003). Introduction to "The myth of secret treasure in childhood" In C. Frank (Ed.) The edge of surrealism: a Roger Caillois reader (C. Frank and C. Naish, Trans.). Durham and London: Duke University Press. pp. 252-254.

Gee, J.P. (2014). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. MacMillan Press.

Guins, R. (2014). Game after: a cultural study of video game afterlife. MIT Press.

Hu, T.H. (2015). A prehistory of the cloud. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

JavierLoustaunau (2016) "Found an old Far Side joking about 'pro gamers' (well assuming it would never happen). https://imgur.com/jYT8MKi" Reddit. <https://www.reddit.com/r/gaming/comments/4jx280/found_an_old_far_side_joking_about_pro_gamers/>

Jenkins, H. (2007). The wow climax: tracing the emotional impact of popular culture. NYU Press.

Kracauer, S. (1995). "Boredom." The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays (T. Levin, Trans.). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 331-334.

Kücklich, J. (2005). "Precarious playbour: Modders and the digital games industry." Fibreculture 5(1).

McGonigal, J. (2011). Reality is broken: why games make us better and how they can change the world. Penguin.

Montez, R. (2006). "Trade"marks: LA2, Keith Haring, and a queer economy of collaboration. GLQ: a journal of lesbian and gay studies. 12(3): pp. 425-440.

Norton, M. (1952). The borrowers. J. M. Dent.

Parikka, J. (2015). A geology of media. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Richmond, S. (2015). "Vulgar Boredom, or What Andy Warhol Can Teach Us about Candy Crush." Journal of Visual Culture 14(1): pp. 21-39.

Stockton, K. B. (2009). The queer child, or growing sideways in the twentieth century. Duke University Press.

Sutton-Smith, B. (1997) The ambiguity of play. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press.

Virno, P. and Hardt, M. (1996). P. Virno and M. Hardt (Eds.) Radical thought in Italy: a potential politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Whalen, Z. and Taylor, L.N. (2008). Playing the past: history and nostalgia in video games. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

Ludography

Colossal Order (2015). Cities: Skylines [PC] USA: Paradox Interactive.

Enlight. (2001). Trevor Chan's Capitalism II [PC] USA: Ubisoft.

Game Arts and Sora Ltd. (2008). Super Smash Bros. Brawl [Wii] USA: Nintendo.

HAL Laboratory. (2001). Super Smash Bros. Melee [Gamecube] USA: Nintendo.

HAL Laboratory and Nintendo SPD. (2015). Kirby and the Rainbow Curse [Wii U] USA: Nintendo.

King. (2012). Candy Crush Saga. App Store. USA: King.

Nintendo EAD. (1998). The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time [Nintendo 64] USA: Nintendo.

Nintendo EAD. (2004). Pikmin 2 [Gamecube] USA: Nintendo.

Riot Games. (2011). League of Legends [PC] USA: Riot Games.

Volition. (2009). Red Faction: Guerrilla [Xbox 360] USA: THQ.

Wube Software. (2014). Factorio [PC] USA: Wube Software.