Time and Reparative Game Design: Queerness, Disability, and Affect

by Kara StoneAbstract

This essay uses a personal account of the process of creating a videogame to explore themes of queerness, disability, and labour. I track the production of the videogame Ritual of the Moon, a game following a queer woman sent to the moon. It is played for 5 minutes per day over 28 days with choices that determine the player’s unique path. The story takes up imagining the future, especially what the future looks like for queer women. Time becomes cyclical, and the fear of women with power bleeds from the past into the future, creating a future that exists between utopia and dystopia. The themes embedded in the game were experienced during production, as well: the effects of psycho-social disability (commonly labelled mental illness) on labour and art practice, queer discovery and narratives, and working through and with “negative” feelings. This paper intermixes theories of queer time with crip time to detail possible approaches to a queer, accessible art practice that takes seriously social inequalities yet moves towards healing. I augment Eve Sedgwick’s idea of reparative reading to form a reparative art practice, one that is inclusive of the paranoid, critical, difficult, and bad feelings that are a part of queer and debilitated life.

Keywords: Affect, Queer theory, Disability, Psycho-Social Disability, Critical Praxis

Content note: This article includes descriptions of experiences of psychosocial disability/mental illness, and discussion, but no graphic description, of suicide.

Videogames are a time-based medium. The playtimes of videogames are precisely calculated: 60 hours, 240 hours, 1 hour, 15 minutes a day over 3 years. The production time is measured as well, though often with less precision. Much has been made recently about crunch and the dangers of cramming development into bursts of unhealthy and inaccessible work habits (see Short, 2016, and Schreier, 2017). Crunch is the dominant mode of working in western technology industries beyond videogames. Like film, videogames are at an intersection of technology, entertainment, and art, often coming with a pressure to produce--and produce at a quick turnaround. The solution sounds so easy: just don’t crunch. Take your time. Live your life outside of development and making. But what are sustainable practices of making? Ones that can follow the ebbs and flows of the sometimes erratic and out-of-grasp force of creativity? Ones that don’t drag out a project or get caught up in perfectionist detailing? Not that any of these are antithetical to crunch; they most often work hand in hand. I’ve been reconsidering my own approach to design and thinking about time and process because I’ve been working on a game about time. And it has taken way too much of it.

Four years ago I received the bud of the idea for Ritual of the Moon. I felt that a close friend of mine was abandoning me. I didn’t know if I should blow up and expel all my rage and burn our friendship so she would finally know how much she hurt me, or if I should keep offering love and try to heal the relationship even if it feels unreciprocated and unnoticed. This blossomed into a story about a witch who has been exiled to the moon, left there to die by the people on earth who fear her power. When comets start hitting the earth, she realizes she has the ability to protect the earth--or let it burn. This essay is a combination of the personal and the theoretical, threading together the process of creating Ritual of the Moon as it relates to time, queerness, and psycho-social disability. It moves between personal reflection on the process of creating and theories on time, queerness, psycho-social disability, labour, and affect. For an artist-scholar, it can be difficult to reconcile those two sides of the dash. It means that I take process very seriously; I consider my work research creation, where the end result is not a simple outcome and demonstration of research, but a process of coming to an understanding, making as research. Writing this paper too is an act that I take in hope of coming to an understanding. To be precise, the goal of writing this paper was to find and understand a process of game design that is healing yet not forcefully positive, emotional yet sustainable. I will detail the game itself, the theories that both informed it and came from it, and theorize what I call reparative game design.

Queer Time

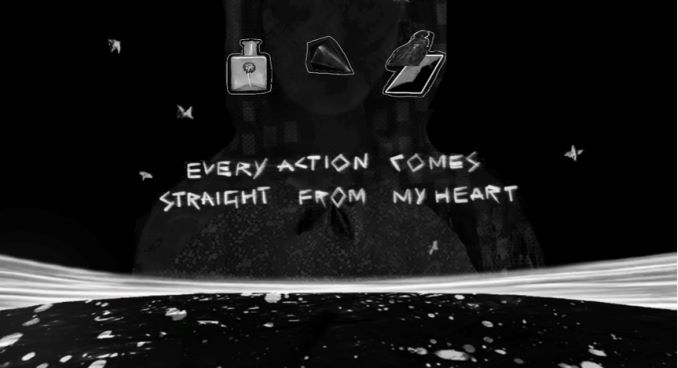

Ritual of the Moon is played for 5 minutes per day over 28 days with choices that determine the player’s unique path. Each day that passes delivers a small bit of the love and betrayal that has landed the witch on the moon to watch over the earth that does not accept her. The flow of each day is as follows: she reflects on the earth, she meditates at an altar, receives a daily mantra, and then makes the decision of whether to destroy or protect the earth. It is also part memory game. The objects at the altar have to be arranged a certain way. Each day that passes, a new object is added and the order has to be continued. It resets each week, so the player does not have to remember the order of more than 7 things, but it is done to connect each day, as well as be ritualistic, to attend to something in a specific way. The story takes up imagining the future: in particular, what the future looks like for queer women. Time becomes cyclical, and the fear of women with power bleeds from the past into the future, creating a time that exists between utopia and dystopia.

Figure 1. Screenshot of the witch directing the comet, Ritual of the Moon.

Figure 2. Screenshot of altar objects and manta, Ritual of the Moon.

Time is a generative topic for queer studies. According to Jack Halberstam (2005), queer time can be thought of as a mode away from linear patterns of living pushed onto us by heteronormativity, such as biological reproduction and familial institutions. The history of conceiving queer time is built in the AIDS epidemic in America: the shortened lives and the communities assembled to protest and take care of each other. Lee Edelman’s No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (2004) urges queer people to refuse the dominant social order and reproductive futurism, to embrace the ways in which queer people have been positioned as negative. I see this in line with the destruction path of Ritual of the Moon--and I don’t mean that as a bad thing. The daily decision of protecting or destroying the earth seems like an easy choice. Protection and healing is always better than destruction, right? But something that has been reaffirmed over the political landscape of 2016 and 2017 is that some things need to be destroyed. We need to wipe some things out and sweep away their ashes before we have the space for something else.

In Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (2009), Jose Esteban Muñoz, like Edelman, argues against consuming ourselves with homonormative, assimilationist issues like gay marriage and queer people in the military, but unlike Edelman, Muñoz believes that we need to stop focusing solely on the present--he calls the present a “prison house.” He argues that need to look to the future with a queer political imagination: “queerness is not yet here; thus, we must always be future bound in our desires and designs.” (p.185) To Muñoz, queerness itself is utopian. There is always something queer about dreaming of utopia, for it means living inside straight time while designing for another time and place. That forward-looking utopia is needed because the present is so “poisonous and insolvent.” (p.30) Whereas straight time is linear, queerness has a horizontal temporality, deeply embedded in the affective, particularly the ecstatic and the hopeful. Muñoz holds on to the revolutionary potential of hope--and yet I can see the other side too, the hopelessness and despair and celebration of our short lives, the need to embrace the negative and destructive. Is it possible there are ways in which we can strategically move between these two positions? Is there a way to allow for a time for no future and a time for all future? In Ritual of the Moon, the player can make different choices each day, to protect the earth, destroy the earth, or destroy oneself. If one holds out a rejuvenating hope, the witch becomes an eternal goddess, destined to spend every day continuing to protect an earth that still does not yet care for her, but holding onto the hope that they may one day recognize her power and love. On the other hand, the player can destroy the earth, then all the planets, then finally the sun to be able to rest in a timeless darkness, emotions spent. In a less academic line, Ritual of the Moon is also a part of a current field of young queer and feminist artists making work that focuses on self-care, astrology, herbalism, and witchcraft (see Arielle Grimes’ The Eldritch Teller (2016) and Broken Folx (2014), Lauren Fournier’s curated exhibitions The Sustenance Rite (2017), Epistemologies of the Moon (2018), and zine Self Care For Skeptics (2015)). They’re looking to the past to form practices that sustain their lives, heal queer wounds, and ensure their existence in the future. Astrology in particular can be seen as a way of imagining the future outside of the influences of racism, sexism, and homophobia; imagining a world determined instead by the movement of planets and the alignment of stars.

Time offers illumination and revelation. I did not even know that there was going to be a queer love story until I started writing. I’m not sure I even knew how queer I really was until I started writing. Things just pour out sometimes if there is space for them to move. To quote this oft-quoted section of Muñoz:

Queerness is not here yet. Queerness is an identity. Put another way, we are not yet queer. We may never touch queerness, but we can feel it as the warm illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality. We have never been queer, yet queerness exists for us as an identity that can be distilled from the past and used to imagine a future. The future is queerness’s domain. (2009, p.1)

I cannot explain how much this quote means to me. It is something I read years ago but became truer and truer over the course of writing my first queer love story set in the future, understanding that I am, in ways, writing a future for myself.

I’m starting to see time in more than the theory and the content of the game. I’ve been working on this game for three and a half years now. It’s the longest I’ve worked on any creative project. I’m two years over the time I thought it would take, with still more time that has to be taken. There are a few reasons why it has taken so much time.

Labour and Psychosocial Disability

This section will detail the process of creating Ritual of the Moon as it relates to gendered labour and crip labour. The visuals consist of handmade objects crafted by the art team: Rekha Ramachandran, Julia Gingrich, and me. We used yarn, paper, clay, quilting, solder, and other crafting media. I hand-embroidered or wood-burned all the text in the game, providing a sort of proof-reading, allowing for personal meditations on time and the affect embodied in the words themselves. It took my spare time over two months to embroider the witch’s reflections, the main story text of the game. We then scanned, digitized, and manipulated our crafted objects as well as found objects such as deconstructed computer chips. All of these objects reflect the story’s blend of past and future, mystical and technological.

Figure 3. Embroidered text.

Figure 4. Scanned bottles (left) and altar object (right).

Figure 5. Paper and chalk crystals (left) and crystal altar object (right).

Figure 6. Social media buttons.

Craft is laborious, but labour here does not necessitate a negative connotation. Queer affect scholar Ann Cvetkovich (2012) writes:

Unlike forms of self-sovereignty that depend on a rational self, crafting is a form of body politics where agency takes a different form than application of the will. It fosters ways of being in the world [in which] body and mind are deeply enmeshed or holistically connected. It produces forms of felt sovereignty that consists not of exercising more control over the body and senses but instead of “recovering” from the mind or integrating them with it. (p.168)

The slow and sensual process of crafting can be a healing experience. It is also important to note the ways in which crafting has been taken up recently, “lest crafting seem pervaded by nostalgia for the past, it is important to note that it belongs to new queer cultures and disability cultures that (along with animal studies) are inventing different ways of being more “in the body” and less in the head.” (p.168) Although it may seem unique to have handmade art in a videogame, the digital and the handmade are more connected than most realize. The history of technology is interwoven with that of women’s work and traditional crafts. We aimed to sew together dichotomous ideas of handmade and digital, the past and the future, magic and science fiction. Sadie Plant’s book Zeros and Ones: Digital Women and the New Technoculture (1997) revisits women’s part in creating and using technologies, pointing out that early computer programming was likened to weaving on a loom. Early film editing was also seen as women’s work, similar to sewing. Pixel art is constructed in the same gridded way as cross-stitching. The connection between craft and technology does not exist only in the past: current technology is made by young women of colour in low-paying factory jobs wrapping thin wires in a specific pattern, bonding to chips, and packaging. They literally make phones, computers, and consoles with their hands (Nakamura 2014). Still, computer technology has become masculinized, dominated by men, cold, and un-embodied. The visuals of Ritual of the Moon were made to evoke a combination of handmade and digital, not as opposing but as united.

The time-consuming labour of crafting stretched the production time but in a beneficial way, unlike another influencing aspect: working long-distance. Over the past 3 years, the team has been scattered across Toronto, Montreal, and Kitchener-Waterloo in Canada, as well as Santa Cruz in California. Our working style took the form of random “crafternoons” when the visual team could meet in person and weekly skype dates. We’re not at a studio eight hours a day together. We’re working elsewhere for eight or more hours and squeezing in an hour here and there when we have the energy. Ultimately, as many of my games are, I view Ritual of the Moon as about mental and emotional wellbeing, which are not only present in the content but the process as well. A few of the team members, including myself, experience various psycho-social disabilities, and there were flare-ups over the course of development. As the person in charge, I tried to navigate everyone’s ups and downs--including my own. It is an ongoing process to figure out the best ways to run with my own cycles of work and recuperation, but to factor in many people is exponentially harder. When we will sync up? How do we give ourselves and others time to heal while having deadlines, pressure, and even sometimes the desire to work? I don’t know the answers, but I know that I had to learn to be softer with myself and others, to accept that there will be times when we really want to be productive but we just can’t be, and that’s more important than any game. I deeply believe that creating art can be a healing, reparative process, something that sustains us and gives us life, rather than draining it. But what are the structures that ensure that? And what kind of art do we make?

In the last century, psycho-social disability has been tied to the ability to work. Depression, for example, becomes legitimate when it prevents a person from performing tasks as they should, or are expected to. Nikolas Rose (2009) expects that depression will grow to be the most prevalent disability in North America. Race, sexuality, and disability scholar Jasbir Puar suggests that this will not happen through an increase of depression as an entity or identity, but “through the evaluation and accommodation of degrees: to what degree is one depressed?” (2013, p.182) The distinction between disabled and nondisabled becomes blurrier. Those of us with certain disabilities may not be able to work in ways that are expected of us, often as expected by others but sometimes also as expected by ourselves. Disability scholar Susan Wendell (2001) writes on what she calls the ‘unhealthy disabled’: those of us with chronic illness and psycho-social disabilities as opposed to the ‘healthy disabled’: those who are disabled but do not identify as sick. For the unhealthy disabled, energy can be a major issue in performing labour. She writes of activist work:

Commitment to a cause is usually equated to energy expended, even to pushing one’s body and mind excessively, if not cruelly. But pushing our bodies and minds excessively means something different to people with chronic illnesses: it means danger, risk of relapse, hospitalization, long-lasting or permanent damage to our capacities to function (as for some people with MS). And sometimes it is simply impossible; people get too tired to sit up, to think, to listen, and there are no reserves of energy to call upon… Stamina is required for commitment to a cause. (p.167)

This can be equated with creating artwork too. Much disability activism understandably has been directed towards proving that if barriers are removed, then those with disabilities will perform as well the non-disabled. For the unhealthy disabled, the barriers are not easily removed. Time and pace are what need to be addressed for many chronic conditions. Wendall makes the point that loosening expectations around time and pace actually counteract dominant disability activism around work because “working according to the employer’s schedule and at the pace he/she [sic] requires are usually considered to be aspects of job performance, even in jobs where they are not critical to the adequate completion of tasks.” (p.168) This applies most directly to those who work for AAA studios and III studios, but what about indie or art game developers without a ‘boss’? What if the people we may fail are our colleagues and collaborators? Kickstarter backers? Patreon patrons? Ourselves?

As Wendall notes, it can be hard to tell how much energy we have available, when to push ourselves, and when to pull back: “Even those of us who have lived a long time with chronic fatigue cannot always tell whether we are not trying hard enough or experiencing a physical/mental limitation, whether we need inspiration, self-discipline, or a nap.” (p.167) Certainly this was an issue in Ritual of the Moon. Would it feel better to take the day off, or would it feel nice to have completed a task? Will writing a sad ending be too much for now, or will it be cathartic? Would it be helpful if I send my collaborator a third reminder email, or trust they will eventually get back to me when they are able? A flexible and changing time and pace of labour is needed for many unhealthy disabled, though it is difficult to argue for this without making us seem unnecessarily burdensome, especially within corporate structures.

Disability may seem like a burden and financial risk inside individual companies, but debility is hugely profitable to capitalism--or, as Puar (2013) notes, the “demand to ‘recover’ from or overcome it.” (p.181) I follow Puar’s practice of “critical deployment of the concepts of debility and capacity to rethink disability through, against, and across the disabled/non-disabled binary”(2017, 2). Debility helps to think about the ways in which the experiences of disability are pervasive and insidious to current culture, circulating through different bodies without necessarily attaching an identity category or binary yes/no box to checkmark. This is not to say they are necessarily different; instead, they are constituted by each other. In North America, the relationship between finance and debility is extreme. Money is often the deciding factor of what treatment to undergo, what kind of therapy is available, what preventative lifestyle choices are possible. Puar writes that “…the forms of financialization that accompany neoliberal economics and the privatization of services also produce debt as debility… Debt becomes a way to measure capacity for recovery, not only physical but also financial.” (p.181) Work simultaneously operates as a factor in defining disability, which then adds the already debilitating culture of work, when able to be performed at all, which also acts as a limiting agent to recovery if one has an unsustainable income.

Queer time intersects with crip time, the relationship of labour, capitalism, and disability. In Feminist, Queer, Crip, Alison Kafer argues for an intersectional and coalition-based politic, utilizing notions of queer time to conceive of crip time, and their differences and similarities. She states that crip time “requires reimagining our notions of what can and should happen in time, or recognizing how expectations of 'how long things take' are based on very particular minds and bodies… Rather than bend disabled bodies and minds to meet the clock, crip time bends the clock to meet disabled bodies and minds" (2013, p. 27). Labour and leisure are connected and confused: sometimes to enact leisure one must labour. Like queerness, disability is often defined by chrononormativity, Elizabeth Freeman’s queer conceptualization of the pressure to move through life in a predetermined way that ensures maximum productivity. We are pressured to produce in a certain way, experience time in a linear fashion, and orient ourselves towards a certain mode of living, one that is not accessible (or desirable) to queer and disabled people.

Queer Death

Inside the game, the player tracks their choices over the 28 days. They can look back and see how they were feeling each day, if they wanted to protect the earth, destroy the earth, or destroy themselves. This tracking came from my own practice of journaling. I rate my days 3 hearts out of 5, 1 star out of 5, 5 moons out of 5. Being able to look back at the shifting stages pulls me out of the belief that I’m stuck in a certain feeling, that the way I feel at that moment is the way I will feel forever. It helps detect patterns over time and better understand the cycles of my moods and identify if anything is really becoming an issue that needs to be addressed. The option of suicide was one of the last additions to the narrative of the game, added about a year after the rest had been written and, I thought, finalized. That came from a time when I felt I wanted to die. This synced up with the time I spent hand-embroidering all the text of the game, so I added on another route that spoke to me at that time. Depending on the choices you make, suicide becomes a third option, a way to escape the binary choice of destroy or protect. It is an example of the ways in which these social hardships drain us and wear us out over time; the ways some of us, especially women, internalize conflict into self-hatred, anger at ourselves, and self-destruction.

In Lauren Berlant’s book Cruel Optimism, the chapter entitled "Slow Death" details “the physical wearing out of a population and the deterioration of people in that population that is very nearly a defining condition of their experience and historical existence.” (2011 p. 95) It conceptualizes the gradual wearing out of people, specifically the debilitated. Slow death does not progress linearly toward an end; it does not denote advancement in a slow pace towards death. Puar suggests that slow death is “non-linear, starting, stopping, redoubling and leaping ahead.” (p.179) Life maintenance becomes a primary focus, the daily “ordinary work of living on.” (Berlant, 2011 p.761) In this zone, life narratives are created not through events that have memorable impact but as episodes that make up day-to-day experiences while not individually changing much of anything. Berlant’s slow death can be linked with crip time. Debility as a whole prospers not in distinct, traumatic events but in day-to-day living, “in temporal environments whose qualities and whose contours in time and space are often identified with the presentness of ordinariness itself, that domain of living on, in which everyday activity; memory, needs, and desires.” (2007 p.759) ‘Events’ are distinct entities that happen rarely in terms of time whereas the ‘episodic’ is described as how “time ordinarily passes, how forgettable most events are, and, overall, how people’s ordinary perseverations fluctuate in patterns of undramatic attachment and identification.” (p.160) The mundane is commonly ignored and taken for granted. Episodic videogames, games that are meant to be played in little bits over longer periods of time, can be incredibly mundane: picking fruit in Animal Crossing: New Leaf (2013) or answering texts about what you ate for lunch in Mystic Messenger (2016). Mattie Brice’s Mainichi (2012), though not a durational or episodic game, also is about the mundane decisions and microaggressions that debilitated people have to navigate each day. Ritual of the Moon takes place in the mundane. Although it is a mixture of sci-fi and fantasy and takes place in space, it is the daily living and small choices made each day that create the world, not single huge events.

The queerness of the witch and the considerations of suicide are not incidental. Pyscho-social disability and queerness intersect here too. The prevalence of suicide by trans and queer youth is a crisis. Dan Savage’s popular ‘It Gets Better’ project is a campaign to prevent suicide by convincing youth that their circumstances and experiences will change and improve as they get older. In her article “The Cost of Getting Better: Ability and Debility” (2013), Puar connects queer neoliberalism to the economics of debility. She utilizes Berlant’s theory of slow death to ‘slow down’ suicide in order to “offer a concomitant yet different temporality of relating to living and dying” (p.179). It is not just the moment of suicide that needs to be prevented, but the many mundane, draining, exhausting, debilitating daily stressors that need to be completely restructured. The connection between queerness and debility within Savage’s campaign ties white cis gay men to capacity, “ensuring that queerness operates as a machine of regenerative productivity” (p.180). The declarative statement “It Gets Better” holds a performative promise: if we state it enough, it will become true. But it is only true for certain populations. Puar argues that “It Gets Better” is a “mandate to fold oneself into urban, neoliberal gay enclaves: a call to upward mobility that discordantly echoes the now-discredited ‘pull yourself up by the bootstraps’ immigrant motto” (p.179). The campaign is in line with positive psychology and the pressure to narrativize with only the positive aspects of life. Our lives are demanded to move towards perfection and happiness, as queer affect theorist Sara Ahmed’s uses as focal point of her book The Promise of Happiness (2010). There is an imperative to be happy, directing us towards particular life choices (heteronormative) and away from others (queer). I will interrogate this binary of positive and negative feelings and life experiences in the next section. For the It Gets Better Project, Puar notes that “… part of the outrage generated by these deaths [LGBTQ+ suicides] is based precisely in a belief that things are indeed supposed to be better, especially for a particular class of white gay men… This amounts to a reinstatement of white racial privilege that was lost with being gay” (179). How then does a non-white queer woman like the witch from Ritual of the Moon, who cannot move to an urban homonationalist hub, whose life will not “get better,” relate to suicide, to the impossibility of a normatively happy future, to a possible eternity of negative feelings? How could she possibly heal from all this?

Healing Affect and Repairative Art

The necessity of healing goes beyond what most people would classify as illness or disability, towards other states that deteriorate lives, such as socioeconomic status, homophobia, gendered violence, racism, transphobia and more. For most states, healing is a never-ending process. Time is a flow of action and recovery, of tiny traumas and mundane distress. Cvetkovich describes healing as “open-ended and marked by struggle, not by magic bullet solutions or happy endings, even the happy ending of social justice that many political critiques of therapeutic culture recommend” (2013, p.80). Recovery, then, is a constant process with no solid and fixed end-state. It is always healing rather than healed. There is no end point because there is always something that is draining.

Affect theory has made affect, emotion, and feelings into both subject of study and method. It breaks down body/mind dualism and offers different modes of knowing other than cognitive rationalization, even suggesting that affect always informs and creates the so-called rational. Cvetkovich explains affect as a mix of psychic emotion and bodily feelings. Affect, emotions, and feelings have different, nuanced meanings and though some theorists make distinctions, Cvetkovich uses all three in order to portray the blurry, indistinguishable ways in which these forces work. Affect, too, is connected to time and futurity. Puar outlines that “affect entails not only a dissolution of the subject but, more significantly, a dissolution of the stable contours of the organic body, as forces of energy are transmitted, shared, circulated. The body… is always bound up in the lived past of the body but always in passage to a changed future.” (2013, p.181)

The affect theory I use is in this essay is distinctly feminist, anti-racist, and queer. Cvetkovich details that the “affective turn” did not feel so new to her because of the long-standing mantra “the personal is political” in feminism. For feminists, theoretical practice was never separate from everyday life, and the public and private were always intertwined. Memoir, personal accounts, and non-traditional forms of learning are embraced in the field, and I align myself with this mode in this essay in hopes to elucidate connections between the personal and the theoretical. Though distinctly political, this affect theory differs from a standard political analysis. Cvetkovich writes: "A political analysis of depression might advocate revolution and regime change over pills, but in the world of Public Feelings there are no magic bullet solutions, whether medical or political, just the slow steady work of resilient survival, utopian dreaming, and other affective tools for transformation." (p.2) This quote outlines some affective methods: the slow, steady work of resilient survival and utopian dreaming.

In her book Touching Feeling (2003), queer theorist Eve Sedgwick proposes two forms of analysis: paranoid reading and reparative reading. (Her use of the words “paranoid” and “schizoid,” often medicalized and pathologized terms, is not lost on me. It is emblematic of a larger culture of using disability as metaphor.) Paranoid reading is the most common form of critique. It consists of familiar protocols in academia like maintaining critical distance, outsmarting each other, and one-upmanship (Love, 2012). The “first imperative of paranoia is There must be no bad surprises.” (Sedgwick 2003, p.130, emphasis hers). According to Sedgwick, paranoia works to anticipate and to ward off negative feeling, in particular “the negative affect of humiliation” (p.145). In its resistance to surprise, “paranoia is at once anticipatory and retroactive, thinking about all the bad things that have happened in order to be ready for all the bad things that are still to come. In this sense, the image of the paranoid person is both aggressive and wounded, knowing better but feeling worse, lashing out from a position of weakness" (Love 2012, p. 237). Heather Love describes it as “grim, single-minded, self-defeating, circular, reductive, hypervigilant, scouringly thorough, contemptuous, sneering, risk-averse, cruel, monopolistic, and terrible” (p. 237). Reparative reading, on the other hand, is a less suspicious mode of critique that focuses on healing queer wounds rather than simply pointing out more insidious forms of oppression. It is “multiplicity, surprise, rich divergence, consolation, creativity, and love" (p. 237). Reparative reading is a form of academic creation where the emphasis is on finding forms of healing and reparation rather than the seemingly endless approach of finding more things to be depressed about. I remember being an undergraduate student and being put off by queer theory’s constant pointing out of homophobia and opening up of queer wounds. I understood that the world was anti-queer. Anti-me. I didn’t need queer theory to tell me the advertisement on my cereal box also wanted me dead. When I came across Sedgwick’s reparative reading as a grad student, I felt suddenly engaged with queer theory again. What can academia do to heal, to comfort, and to reform dominant understandings of the world into something that enables queer people to keep living? Love honours Sedgwick in her writing on reparative reading, saying Sedgwick "enabled" Love to have a tolerable job and to live a queer life she could never have imagined. Judith Butler says Sedgwick made her "more capacious rather than less" (2013, p.109). Cvetkovich cites authors like Audre Lorde for enabling her to get up in the morning (2012, p.26). I deeply appreciate these nods to the importance of critical theory in reframing one’s worldview. Shifting one’s thinking can be a healing tool.

This is not to say that paranoia is never necessary. The criticisms of Sedgwick’s reparative readings are generative as well. Edelman argues that Sedgwick “repeats the schizoid practice it claims to depart from” (Berlant and Edelman 2013, p.44) Distinguishing paranoia from reparation enacts a hypocritical circularity. Edelman is not arguing there is no healing that can take place within reparative reading, but that amelioration will always inflict some harm. Love makes the case that the essay itself is not only reparative, but it is also paranoid:

Yet, just as allowing for good surprises means risking bad surprises, practicing reparative reading means leaving the door open to paranoid reading. There is risk in love, including the risk of antagonism, aggression, irritation, contempt, anger--love means trying to destroy the object as well as trying to repair it. Not only are these two positions--the schizoid and the depressive--inseparable, not only is oscillation between them inevitable, but they are also bound together by the glue of shared affect. (p.239)

The good and the bad are not divisible. Cvetkovich seeks to depathologize negative affects to prevent them from being dismissed as resources for political action. At the same time, she is careful not to suggest that mental illness and “bad” affects should be transformed into positivity: depression “retains its associations with inertia and despair, if not apathy and indifference, but these affects become sites of publicity and community formation” (2012, p.2). She does not transform bad experiences and negative feelings into positive things to be celebrated, but instead frames them as political statements. The good and the bad are wrapped up into one: we are "not to presume that they are separate from one another or that happiness or pleasure constitutes the absence or elimination of negative feeling" (2012, p.6).

My videogames about psycho-social disability, including Ritual of the Moon, Medication Meditation (2014), and Cyclothymia (2015), are never meant to find the “good” in mental illness, never to look on the bright side. Instead, they are meant to explore those feelings we think are wrong or are told are bad, and use them to build communities and encourage social change, similar to what Cvetkovich describes of her own work: “Thus, although this book is about depression it’s also about hope and even happiness, about how to live a better life by embracing rather than glossing over bad feelings.... It asks how it might be possible to tarry with the negative as part of daily practice, cultural production, and political activism" (p.2-3). Embracing the possibility of hard, difficult, and unwanted feelings is a way to fully utilize reparative reading. Criticism, paranoia, and refusal are part of self-defence, protection, and healing.

A long, slow art practice is a unique way into examining and repairing from the everyday. I propose that reparative game design is a method to work through difficult feelings, but it is also a means to stay in them as long as they need to be felt. Sometimes the work is to bring out difficult feelings. Sometimes the work is to make yourself and others feel worse. Reparative art, like reparative reading, does not seek to expose wounds, but to focus on healing--the many states that need healing and the many forms that healing takes, including the “negative,” the difficult, the unwanted. Cvetkovich includes the transformative possibilities of bad feelings. She warns against:

moving too quickly to recuperate them [bad feelings] or put them to good use. It might instead be important to let depression linger, to explore the feeling of remaining or resting in sadness without insisting that it be trans- formed or reconceived. But through an engagement with depression, this book also finds its way to forms of hope, creativity, and even spirituality that are intimately connected with experiences of despair, hopelessness, and being stuck. (p.14)

Depression is associated with being stuck. Creativity is associated with movement. If depression is a block or an impasse, Cvetkovich suggests the way to deal with it might lie in forms of flexibility and creativity. Sometimes creativity moves forward, sometimes sideways, and sometimes even backward. It is a multiplicity of ways of being able to move, solve problems, and have ideas. Reparative art is not a way to move on from or be cured of mental illness or other the states in need of healing, but actually a mode of staying in them. Surviving through them. Sometimes that means moving in them, sometimes being stuck in them.

Reparative art sits between research creation and art therapy. Art therapy is psychoanalytic, wrapped up in the subconscious and the symbolic. Many people understand it as a “make art = get better” field. After reading this far into the paper, you may guess my thoughts on that! We often hear that making art can be therapeutic. You might also realize that I have not used the word therapeutic in this paper before now. It has too many meanings, from soothing to revelatory. But therapy itself can be very difficult! A therapist might design a session in order to stay in the difficult feelings on purpose. Making art can be a way to feel release (a common way of thinking about art therapy), but it can also be a way to realize things, to come to understand yourself, others, and the world. It is a process of bringing out difficult feelings, and working through them, and sometimes actually staying inside those feelings for as long as they need to be felt. And sometimes, it is a process of feeling even worse.

Like affect theory, reparative art is situated in the everyday. It is connected to repetition, mundanity, and urgency, rather than event, catastrophe, and emergency. I see it as a daily ritual, something that needs to be tended to everyday. In a conversation with an artist-scholar friend, we discussed our turns towards durational art. They shared a story with me about a time in their life when they were feeling incredibly low and as if life could not go on, when their father told them to do something every single day. It didn’t matter what it was, as long as they did it. My friend then put on mascara every day. They said it saved their life. I too have daily rituals that sustain my life, primarily a rigid yoga and meditation practice, and a much less rigid daily writing practice. I suspect that if healing through and with videogame technology is at all possible, it exists at this level.

We tend to portray most art practice, including game design, as an individual pursuit, so I want to be clear that I view reparative art as tied to the collective and to community. Berlant and Cvetkovich emphasize the importance of affect in forming their FeelTank project. Cvetkovich writes, "if we can come to know each other through our depression, then perhaps we can use it to make forms of sociability that not only move us forward past our moments of impasse but understand impasse itself to be a state that has productive potential" (p.23). The collective is an integral part of healing and thus reparative art. Anti-oppression communities formed around videogames have been necessary to sustaining my art and scholarly practice. This is not to paint a totally utopic portrait of these communities. Many individuals in these communities, myself included, have had tumultuous experiences, often alongside life-changing, heart-opening, encouraging ones. What do we put at stake when we build such communities? How do we account for the harm they can cause? For their lack of reparative techniques? How can communities enable reparative art? Can reparative art made by groups heal the individual? We need to find ways that we can repair our creative process so our creative process can repair us. I theorize a reparative game design practice that is based on the theories I’ve written on above about queerness, disability, and affect, one that aims to integrate emotion into the art piece with an orientation toward healing.

Time Again

As much as I acknowledge the importance of negativity and difficulty, it is not easy to view ‘stuckness’ as an acceptable state. I’m writing this reflection from a precarious place: 4 years in, unfinished, feeling like all the creative work is over, waiting for programmers and playtesters to do their work. I just want it to be over and the game to be released. It is draining. It feels like there a heavy cloud on my head pushing me into the ground, even though I know that the prolonged time has changed the game for the better. The first iteration of Ritual of the Moon was a basic resource management game. There were once items and ways of winning and losing, numbers, and lots of UI. I did not set out trying to incorporate social politics into the piece. It was just a relationship between me and a close friend. Yet over the past 4 years, I see so much of it coming from, informed by, and responding to the political climate. I’ve been thinking about what I’ve been calling “late inspiration,” yet another form of time working in an unexpected way. It encompasses media I feel have inspired my own work but did not see until after the idea had been formed. Ideas that are already--in past, present, and future--floating out in the world with multiple people picking them up. These pieces pull out fragments in my work that I didn’t know were there because they were so deeply embedded I couldn’t see them.

One example of this is Larissa Sansour’s video A Space Exodus. It was made in 2009 but I didn’t know of it until early 2017. Sansour is a Palestinian woman, and in this piece she travels to the moon and plants the Palestinian flag on it. It is obviously bittersweet, to claim a space finally as her own, but there is nowhere on earth that she or other Palestinian people can be citizens. Nowhere on earth to exist.

Another late inspiration is Mystic Messenger (2016), a mobile game that you play for 15 minutes at a time over 11 days. It is multi-linear and real-time based. Cute boys and a woman message you 4-7 times a day, asking if you’ve eaten. It locks you out when there is nothing left to do at that time. I played it a year ago, blown away by the joy of having a durational game in short bursts carried around with me on my phone.

When designing the witch, the only person we see in the game, the art team (Julia Gingrich, Rekha Ramachandran, and myself) tried to stay away from skinny and white as default. When initially writing the game, the only thing I knew about the witch was that she was a woman. She became (or was revealed as) queer as I was writing. In the same way she became/was revealed as queer, her identity formed as we designed her visuals. Ramachandran designed a face that shifted colours, flickering and fading, that spoke to her own body of work about mixed race identity. The witch’s veil developed new meaning over time. We started with the intention of it being a classic witch’s cape, but it has become cemented as a hijab. Though no one on the team is Muslim, I believe one cannot let all the work of representation fall solely on the shoulders of those in dire need of representation. It is so important right now for those of us in North America and Europe, to consider Muslim futures, to realize the path our governments are on and then fight for a future where Muslim people are welcomed and not sent away.

Figure 7. Animation frames of the witch.

But how can this be? How can these inspirations and politics come after the project has already been written and designed? Here I turn to quantum physics, primarily the work of Karen Barad, to creatively imagine the ways in which the past and the future are connected--not just in the way the content of Ritual of the Moon combines them, but that time itself is open and unresolved.

In the paper “Quantum Entanglements and Hauntological Relations of Inheritance: Dis/Continuitues, SpaceTime Enfoldings, and Justice-to-Come,” Barad theorizes that time does not operate in the way we commonly think:

…the past is not set in stone and the future is not a line extended in front of us: that the past was never simply there to begin with and the future is not simply what will unfold; the ‘past’ and the ‘future’ are iteratively reworked and enfolded through the iterative practices of spacetimemattering--including the which-slit measurement and the subsequent erasure of which-slit information--all are one phenomenon. (p.261)

The past is never closed, over and complete, existing behind us--but it’s also not fully changeable. It will hold remnants, ghostly-hauntings only seen when sought out:

…it is not the case that the past (a past that is given) can be changed (contrary to what some physicists have said), or that the effects of past actions can be fully mended, but rather that the ‘past’ is always already open to change. There can never be complete redemption, but spacetime mattering can be productively reconfigured, as im/possibilites are reworked. (p.266)

Black Quantum Futurism, proposed by Rasheedah Phillips and Camae Ayewa, is a speculative approach to reality that aims to manipulate space-time in order to see into possible futures and bring out a desired future for Black people. They write that “the past and future are not cut off from the present--both dimensions have influence over the whole of our lives, who we are and we become at any particular point in space-time” (2016). Phillips puts forth the idea of retrocurrences, defined as “a backwards happening, an event whose influence or effect is not discrete and timebound--it extends in all possible directions and encompasses all possible time modes.” (p.30) I propose that what I called “late inspiration” are examples of retrocurrences, the future affecting the present, in a retrocausal fashion. The future has changed the game. What I’m trying to get at with this idea of “late inspiration”--with trying to use quantum field theory alongside art--is that the creative process is not so linear. It is linear in some ways: there wasn’t a game, there was work on the game, and someday hopefully there will be a game, but within that guiding timeline, there are instances that don’t make sense. Things drip out that we do not initially intend. We re-reading our work and find new meanings in it. But that newness does not mean it was not already there. It’s not simple revisionism. If we are open, porous, sensitive people, we will take in ideas from the past, the future, and the present without realizing, and then we will leak and seep them out. We just need to give ourselves and our artwork time.

At least, that is what I’m telling myself. I’ve spent a lot of the past two years agonizing and complaining. Oh my god I want the game to come out so much. It’s a year over my estimation. It’s not done. I really want it to be done. I’m scared it will never be done. I’m scared it will loom over my head for the rest of my life. I’m scared I will put it out before it’s ready.

How do you know when it’s time to let go?

But I’ve had to shift my thinking about it. Instead of hating that it isn’t out yet, I’ve started to tell myself that it needed time to be fully digested, for me and the team to fully understand it and do the idea justice. It needed time to transform. I tell myself that labour takes time. That love takes time. I needed time to strip it to the barest bones of meditation on healing the future.

I’m so used to making things in a hypomanic state: work work work, exhaust myself then be done. But the pace has to be different for this game because it is about a different pace. It is about daily dedication in small bits over long periods of time. It is about being confused, stuck, suicidal. It is about meditating for 5 minutes a day because over time that creates a ritual that sustains us. And maybe the game is waiting for the right time to be released. Maybe it is waiting for when it makes the most sense. I’m realizing that it feels more prescient than ever. I know it is on so many of our minds, that push and pull between the desire to set the world on fire, giving up on it, and only caring for each present instant, and on the other hand, putting every ounce of ourselves into making the world better even if it feels fruitless, even when the majority seems against us. It feels befitting and relevant to consider the future of queerness, of racism, and of disability in North America and much of the world, at a time when living on the moon by yourself doesn’t seem like such a bad idea.

Ritual of the Moon will be available in the future. www.ritualofthemoongame.com

Acknowledgements

Infinite thanks to my Ritual of the Moon teammates Rekha Ramachandran, Julia Gingrich, Maggie McLean, Halina Heron, Hope Erin Phillips, Matthew R.F. Balousek, Kevin Stone, and Chris Kerich for all the work, creativity, and sensitivity over the years. Thank you Jess Marcotte for providing valuable feedback on this paper. Thank you Karen Barad and our feminist science class for helping me think through time.

References

Ahmed, Sara. 2010. The Promise of Happiness. Durham: Duke University Press.

Barad, Karen. 2017. “No Small Matter: Mushroom Clouds, Ecologies of Nothingness, and Strange Topologies of Spacetimemattering.” In Anna Tsing et al (Eds. ) Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene. Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 103-120.

Barad, Karen. 2015. “TransMaterialities: Trans*/Matter/Realities and Queer Political Imaginings.” GLQ 21 (2-3): 387-422.

Barad, Karen. 2010. “Quantum Entanglements and Hauntological Relations of Inheritance: Dis/continuities, SpaceTime Enfoldings, and Justice-to-Come.” Derrida Today 3(2): 240-268.

Berlant, Lauren. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham: Duke University Press.

Berlant Lauren. 2007. “Slow Death,” Critical Inquiry, Vol. 33. 754-80.

Berlant, Lauren and Lee Edelman. 2013. Sex, or the Unbearable. Durham: Duke University Press.

Butler, Judith. 2013. “Capacity.” In Stephen M. Barber, & David L. Clarke (Eds.), Regarding Sedgwick: Essays on Queer Culture and Critical Theory. London: Routledge.

Cvetkovich, Ann. 2007. “Public Feelings.” South Atlantic Quarterly 106(3): 459-68.

Cvetkovich, Ann. 2012. Depression: A Public Feeling. Durham: Duke University Press.

Edelman, Lee. 2004. No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Durham: Duke University Press.

Fazeli, Taraneh. 2016. “Notes for ‘Sick Time, Sleepy Time, Crip Time: Against Capitalism’s Temporal Bullying,’ in Conversation with the Canaries.” Temporary Art Review, May 26. http://temporaryartreview.com/notes-for-sick-time-sleepy-time-crip-time-against-capitalisms-temporal-bullying-in-conversation-with-the-canaries/

Haraway, Donna. J. 2016. Staying With the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

Halberstam, J. 2005. In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives. New York: New York University Press.

Kafer, Alison. 2013. Feminist, Queer, Crip. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

Love, Heather. 2011. “Truth and Consequences: On Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading.” Criticism 52(2): 235-41.

Munñoz, Joseé Esteban. 2009. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York: New York University Press.

Nakamura, L. (2014). Indigenous Circuits: Navajo Women and the Racialization of Early Electronic Manufacture. American Quarterly 66(4), 919-941. Johns Hopkins University Press. Retrieved December 7, 2018, from Project MUSE database.

Plant, Sadie. 1997. Zeroes + Ones: Digital Women and the New Technoculture. New York: Doubleday.

Phillips, Rasheedah. 2016. “Dismantling the Master(s) Clock.” In Rasheeda Phillips and Dominique Mattie (Eds.) Space-Time Collapse 1: From the Congo to the Carolinas: Black Quantum Futurism. Afro Futurist Affair/House of Future Sciences Books.

Puar, Jasbir K. 2013. “The Cost of Getting Better: Ability and Debility.” In Lennard J Davis (Ed.), The Disability Reader, Fourth Edition. Routledge: New York and London.

Puar, Jasbir K. 2005. “Queer Times, Queer Assemblages.” Social Text, Vol 23, No. 3-4, 121-140.

Sedgwick, Eve. 2003. Touching Feeling. Durham: Duke University Press.

Stewart, Kathleen. 2007. Ordinary Affects. Durham: Duke University Press.

Stewart, Kathleen. 2017 “In the World That Affect Proposed.” Cultural Anthropology 32(2): 192-98.

Wendell, Susan. 2013. “Unhealthy Disabled: Treating Chronic Illnesses as Disabilities” In Lennard J Davis (Ed.), The Disability Reader: Fourth Edition. Routledge: New York and London.

Ludography

Brice, Mattie, (2012). Mainichi. [PC & Mac]. Self Published.

Cheritz. (2016). Mystic Messenger. [iOS & Android]. Cheritz.

Grimes, Arielle. (2014) Broken Folx. [Browser]. Self Published.

Grimes, Arielle. (2016) The Eldritch Teller. [Browser]. Self Published.

Nintendo EAD. (2013). Animal Crossing: New Leaf. [Nintendo 3DS]. USA: Nintendo.

Stone, Kara. (2015). Cyclothymia. [PC & Mac]. Self Published.

Stone, Kara. (2014). Medication Meditation. [iOS & Google Play]. Self Published.

Stone, Kara. (TBA). Ritual of the Moon. [PC, Mac, iOS, and Android]. Self Published