When (and What) Queerness Counts: Homonationalism and Militarism in the Mass Effect Series

by Jordan YoungbloodAbstract

Drawing upon the theoretical work done by Jasbir Puar and other scholars in linking normative queer identity to trends of militarism and national identity, this paper examines how two titles by the developer BioWare--2010’s Mass Effect 2 and 2012’s Mass Effect 3--integrate various depictions of LGBTQ-affiliated characters into a larger systemic ludic process of thinking about populations as resources, numbers, and ultimately quite literally “war assets” to be expended. In tethering representations of willing, patriotic queer crew members willing to offer themselves up to the game’s overall edict and play structure to save the galaxy and the future at all costs, BioWare renders LGBTQ identity as ideally complicit with neocolonial objectives and counted as a “positive” resource in the fight. By tracing what queer bodies are allowed to count--and what ways--within the abstracted, mission-first logic and gameplay objectives of each title, a vision of Mass Effect (and the modern BioWare RPG more widely) emerges in which queerness is made, above all, to be a useful asset to the nation-state, and expendable when not. In fact, queerness serves, in many ways, as a useful economic resource as well, allowing the company to appeal to LGBTQ consumers via the lure of representation while only offering a vision of queer life that earns approval via military service and diligence.

Keywords: queer, homonationalism, BioWare, Mass Effect, biopower, populations

Content note: This article discusses death and space military violence.

On July 26, 2017, President Donald Trump announced via Twitter in a series of surprise announcements that the government’s policy on transgender soldiers was about to change. Citing consultation with “my Generals and military experts,” Trump claimed that “the United States Government will not accept or allow transgender individuals to serve in any capacity in the U.S. Military,” rescinding a policy that had existed under the Obama administration (Frank, 2017). Strikingly, his rhetoric repeatedly focused on transgender soldiers as a negative net resource, justifying the new policy by claiming “[o]ur military must be focused on decisive and overwhelming victory and cannot be burdened with the tremendous medical costs and disruption” of transgender service members. It was not morality, but sheer financial efficiency, that demanded such sweeping action.

In the following days and weeks, numerous editorials, speeches, and political responses latched onto Trump’s claim of “tremendous medical costs” in order to debunk them. Such comparisons ranged from the intentionally provocative, claiming that the military spends five times as much on Viagra as it does on transgender troops (Ingraham, 2017), to the decidedly pragmatic, often looping back to a much-cited 2016 report by the Rand Corporation breaking down just how much the U.S. government might be spending on these efforts (Schaefer, et al., 2016). Yet many of the responses ended up validating the logic, if not the outcome, of Trump’s thinking. Transgender troops were not a problem because they incurred such a small overall cost to the war effort, made such a minimal impact on morale, and ultimately proved worth the investment being made in them. Even a late 2017 policy brief by a collection of former military Surgeons General stressed convenience, claiming that the necessary medical training for recruiters “could be accomplished by sending a one-page instruction to all recruiting stations,” requiring less than a day to complete (Frank, 2017). Indeed, it was these troops’ very desire to be counted as resources, to offer themselves as protecting freedom, that should vouchsafe them: a point crystallized in John McCain’s public statement from July 26 disagreeing with Trump, claiming that “[t]here is no reason to force service members who are able to fight, train and deploy to leave the military -- regardless of their gender identity” (Ingraham, 2017).

Such arguments would seem to have little to do with videogames. However, the logic of when and how bodies are made to count, the expense of service and allegiance to the overall effort of fighting a foreign enemy, and the role of queer people within these systems might be strikingly familiar to players of any major BioWare title over the past ten years. Consider 2014’s Dragon Age: Inquisition and the case of the mercenary Krem, the first openly trans character in a BioWare title. While Krem is given a series of optional dialogue sequences arguing for his value as an individual, his primary purpose in the game’s narrative is to serve as a sort of moral bargaining chip within the larger effort to consolidate military power for the titular Inquisition. Leaving Krem’s unit to die in a specific story sequence allows the player to solidify an alliance with an entire militarized nation, while protecting his unit means unlocking optional sidequest missions--and more importantly, maintaining the loyalty of his commander and controllable squadmate Iron Bull, who the player may value as a powerful warrior-class team member and/or romance option. The complexity of Krem’s gender identity and role as a soldier ultimately boils down to how the player chooses to literally value him within the game’s systems, which Dragon Age: Inquisition neatly boils down to a numeric value called, of course, “Power.”

Drawing in part upon the work done by Jasbir Puar in her 2007 book Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times and subsequent studies of the link between LGBTQ-supportive politics and militarism, this article focuses upon how two specific titles--2010’s Mass Effect 2 and its sequel, 2012’s Mass Effect 3--established this systemic gameplay and narrative formula of the modern BioWare title: a formula that leans heavily on teaching the player the abstracted algorithms of warfare and then enacting those algorithms via queer characters that often almost fall over themselves to prove themselves useful to the overall equation. As BioWare has chosen to go “bigger” with each subsequent title, the scope of conflict has reached the macro level, with the player often in charge of nebulous concepts like “galactic readiness” and “planet viability,” conveyed to the player as numbers that fluctuate based on varying gameplay decisions.

Almost every action committed by the player feeds into these larger equations, many of which dictate aspects from the quality of ending the player receives to the items and perks unlocked to make the player-character and their party better. In learning how to navigate the math of war and crisis-time leadership, each title teaches the player to constantly consider cost: what strategies are most useful, which acts most beneficial, which communities most worth the effort to keep them alive. A successful Mass Effect series player typically learns, in essence, biopolitics, along with a wealth of other modern political values tied to capital and power; as Nick Dyer-Witheford and Greig de Peuter write in their critique of videogames and global capitalism, games “simulate identities as citizen-soldiers, free-agent workers, cyborg adventurers, and corporate criminals: virtual play trains flexible personalities for flexible jobs, shapes subjects for militarized markets, and makes becoming a neoliberal subject fun” (2009, p.xxix-xxx). I link these trends to what Puar deems “homonationalism”: an extension of Lisa Duggan’s concept of homonormativity, where queer identities are allowed into the acceptable social fold (and thus rendered normative) by adhering to knowable, homogenous ideals and patriotism. In fact, it is the apparent acceptance of queer identity in relation to other countries that allows for exceptionalism at the global level; as Puar writes, “homonormativity… ties the recognition of homosexual subjects, both legally and representationally, to the national and transnational political agendas of U.S. imperialism” (2007, p.9)--a method echoed and adopted by other Western countries as well.

It is this “safe,” normative, state-supported model of queerness--represented by a menagerie of LGBTQ individuals who habitually prove their merit by demonstrating unfailing loyalty to the player-character and a knack for military-related prowess--that is juxtaposed in Mass Effect to a variety of destructive, foreign, even terrorist “others,” populations that are “peripheral to the project of living, expendable as human waste and shunted to the spaces of deferred death” (Puar, 2007, p.xxvii). Mass Effect, in essence, performs a variation of what Spade and Willse see as the ongoing multicultural imperialist project, where “the rape victim, the persecuted homosexual, the gay soldier, and most recently, the trans soldier…are mobilized in ways that do not relieve the actual enduring realities of heteropatriarchal violence, but instead shore up the apparatuses that produce that violence” (2014, p.7). Playing with an awareness of this inherent logic reveals the procedural rhetoric underneath, and as Ian Bogost claims, allows us “to expose and explain the hidden ways of thinking that often drive social, political, or cultural behavior” (2008, p.128).

In particular, this article draws upon and further complicates the early work on BioWare and imperialist logics done by Christopher Patterson in his striking 2015 essay “Role-Playing the Multiculturalist Umpire: Loyalty and War in BioWare’s Mass Effect Series.” Patterson’s focus throughout is on the player’s role as a navigator of multiracial alliances in bringing the galaxy together under one military banner, particularly in how the game’s morality system and dialogue choices for party members “put the player in the curious position of managing--and often manipulating--those characters, reducing the value of their psychological complexity to abilities that must be manipulated and employed during battles” (2015, p.208). In close-playing Mass Effect, Patterson similarly acknowledges how the role-playing and gameplay mechanics of each title “which require the player to learn strategies and tactics to engage enemies, use highly problematic assumptions about cultural difference to bolster suspicion and violence onto those cast as ‘monocultural’ or ‘nontolerant’” (2015, p.208). While not as focused on the systems of equations, values, and resource management, Patterson’s language here clearly points the way towards the abstracted logic necessary to see teammates, in-world characters, and other objects as resources to be employed towards the greater good of preserving tolerance, “civilization,” and other attributes of the imperialist nation-state.

Yet while Patterson does a remarkable job throughout of connecting this line of criticism throughout the essay to questions of race and ethnicity, the question of sexual orientation is largely relegated to a quick aside where he notes that players of a female Shepard have more romantic choices in the first two games, and that Jennifer Hale’s performance “allows the player to diverge from the heterosexual norm through a more empathetic voice actor” (2015, p.223). A full discussion of the themes of tolerance, acceptance, and neoliberal values in connection to imperialism in BioWare games must incorporate sexuality and orientation into its larger purview, particularly as few companies have more openly and repeatedly attempted to court the money and loyalty of the LGBTQ community through representation in their titles than BioWare--and few publishers more willing to employ that apparent progressivism as a marketing strategy than its parent company, Electronic Arts. To utilize queer representation as a hook and then fold that representation back into the service of a gameplay model that primarily deploys queerness as docile, loyal, and nation-centered undoes the potentiality at the heart of such a gesture; as Edmond Y. Chang writes in his analysis of queergaming, “representation must inform mechanics, and mechanics must deepen and thicken representation” (2017, p.18).

Similarly, while a number of essays have tackled the question of queer topics in BioWare games, most focus primarily on either the question of LGBTQ presence at all (such as Megan Condis’s 2015 essay on fan community reactions to queer characters in BioWare titles like Dragon Age II) or on the language of sexual choice for players, such as Summer Glassie’s 2015 analysis of Asari sexuality and desire in the Mass Effect series, or Eva Zekany’s 2016 reading of what it means to desire the “alien” as a player of Mass Effect. To look at queerness as a component within a larger systems-level reading of BioWare’s overall normative, militaristic world building projects means to further expand the project put forth by Bonnie Ruberg and Adrienne Shaw in their introduction to the 2017 collection Queer Game Studies, where queer game studies and queer theory is “not simply acknowledgement of LGBTQ lives, but dismantling systems of oppression and normalization” (2017, p.xviii). Queer lives in BioWare games are pieces of a larger puzzle, one tied to questions of national identity, neocolonial thinking, and ultimately the fantasy ofsaving the “right” kind of future. In challenging one, the ripples extend outward into systems both within and outside the game, pointing the way toward a richer vein of criticism and the possibility of gameplay (and cultural) structures that do not perpetuate these same assumptions.

“I feel like I’m actually being useful”: Homonationalism and Mass Effect 3

The Mass Effect series is a collection of third-person science fiction shooters set in the year 2183, where humanity has moved into space and begun to visit other star systems in the galaxy. The player-character is Commander Shepard, a military hero of the human Alliance who can be created as either a man or a woman; from there, the player can choose a background story, combat class, and general appearance of the avatar. The game’s design was intended to combine the action and intensity of a more traditional shooter with the customization and branching narratives that are the hallmark of Western role-playing. Most of the content is oriented around a mixture of combat missions and player exploration, with a large portion of the game’s narrative conveyed through dialogue trees with other characters. Selecting certain responses and choices is linked to a moral binary, here dubbed as “paragon” and “renegade,” which affects certain dialogue options and perceptions of the avatar in the game world [1]. As with previous titles from BioWare like 2005’s Jade Empire, the player must recruit a party of fellow adventurers to help her complete various quests across different planets, develop various skills and abilities, and obtain new items. Both within and outside this recruitable party, opportunities arise for romantic relationships, many of which can carry over between titles.

These options for romance became a central lingering criticism of Mass Effect 2: namely, the absolute lack of any same-sex relationships, whether bisexual or specifically gay and lesbian. This shying away from sexual controversy was particularly notable in 2010, given that BioWare had released the year before Dragon Age: Origins, which contained two bisexual characters as romance options. When questioned about Mass Effect 2 declining to include such options, series producer Casey Hudson claimed that “[w]e still view it as... if you’re picturing a PG-13 action movie. That’s how we’re trying to design it. So that’s why the love interest is relatively light” (John, 2010). Ray Muzaka, co-founder of BioWare, responded in the same interview that “[s]ome game franchises are going to be slightly different but that’s part of our effort to diversify the portfolio and enable some franchises to have some more choice and some of them are around defining a more specific character” (John, 2010). In their responses, at least, the game was intended to be a safe bet, a portfolio diversifier meant to appeal to a wide audience: language deeply infused with BioWare’s use of sexuality and representation as driven by profit as much as narrative viability.

Yet this approach to same-sex romances suddenly shifted course in Mass Effect 3. While prior Mass Effect titles had never featured human LGBTQ material, BioWare, in what they claimed was a response to player demand, declared that Mass Effect 3 would feature openly and exclusively gay and lesbian relationships for the first time in the series. Subsequently, online discussion about the role of gay and lesbian relationships in Mass Effect proliferated, from commentators praising BioWare for “dragging [games] out of their adolescent phase” to irate players sabotaging the user scores of the game on sites like Metacritic and Amazon with thousands of negative reviews within hours of the game’s release due to this queer content (David, 2012). Threats of boycotts against BioWare games were met by vows of staunch support in exchange for further LGBTQ content. It was clear that discussions behind the scenes at EA and BioWare determined that it was worth--on multiple levels--the effort to include gay and lesbian relationships; the PG-13 portfolio diversifier of Mass Effect 2 now attempted to deploy diversity as a means of both social and financial capital.

Sustaining this future requires individuals willing to adhere to its vision above all else, a focus which drives the majority of Shepard’s personal relationships with his crew. As mentioned, a player wanting to pursue an exclusively gay or lesbian relationship has two new possible options aboard the Normandy, shuttle pilot Esteban “Steve” Cortez if Shepard is a man and specialist Samantha Traynor if she is a woman. Far from being a disruptive, deviant presence--providing the anywhere, anytime sodomy simulation the original Mass Effect was feared to be [2]--they actually represent two of the most order-maintaining positions on the ship: Cortez procures supplies, flies the mission shuttle, and oversees the Normandy’s inventory, while Traynor is in charge of coordinating Shepard’s schedule and duties with the rest of the crew. This order extends to their romantic interactions, as like their heterosexual counterparts, they too demand an extended courtship and monogamy before entering into a relationship. They are professional, polite, duty-driven soldiers whose primary goal is ensuring the success of the mission and winning the war; upon entering a relationship with Shepard, that loyalty extends to supporting him or her emotionally and ensuring the task is done, each of them spending a night in Shepard’s cabin before the final assault on Earth. Both Cortez and Traynor also fuse benign queerness to questions of race; Traynor hails from the UK and is suggested to be of Indian heritage, prickling at the suggestion that she might be the “curry expert” of the ship in the Citadel DLC, while Cortez’s brown body and occasional Spanish barbs at his fellow squadmate of color, James Vega, give him a veneer of exoticism. Patterson’s reading of “the sanctity of diversity and tolerance represented through the player’s squad and the multicultural federation that they fight to protect” (2015, p. 213) here gains a queerer angle, one where race and sexual orientation are connected into a docile Other which is happy to fight for the right to sustain normality into the infinite future.

While I do not want to turn an analysis of Traynor and Cortez into an attack on their lack of deviance--to lapse purely into an oppositional reading upholding one purest ideal of “queer,” or of racial identity--it is decidedly noticeable how far Mass Effect 3 goes to make them unthreatening, while ensuring that the future in which they exist mirrors normative assumptions of LGBTQ life and family structure in the present day. Cortez, for example, spends the early portions of his storyline mourning the loss of his husband Robert, while Traynor tells a female Shepard before the final battle that she wants “a house with a white picket fence, a dog, I’m thinking two kids… you are taking notes, aren’t you?” The future Earth they fight to preserve is one marked by the apparent full assimilation of gays and lesbians into the nuclear family structure and domestic lifestyle, and the future they will step into is highlighted with the usual milestones of middle-class identity; Puar’s suggestion that “the capitalist reproductive economy (in conjunction with technology: in vitro, sperm banks, cloning, sex selection, genetic testing) no longer exclusively demands heteronormativity as an absolute” (2007, p.31) is born out in Mass Effect’s fleeting visions of 2186 outside of wartime. They are compliant, inviting, adhering to normative convention down to the precise number of desired offspring. Cortez’s writer Dusty Everman affirmed this outlook in an online interview, explaining that “I believe that by the 22nd century, declaring your gender preference will be about as profound as saying, 'I like blondes.' It will just be an accepted part of who we are. So I tried to write a meaningful human relationship that just happens to be between two men” (Purchese, 2012). Everman’s specific utilization of “meaningful” is apt, as even if the relationship “just happens” to be between two men, it must still signify a sufficiently valuable social union. A fleeting hookup will not do; finding a replacement for a lost husband will.

What makes Cortez still valuable on a gameplay and narrative level, however, is his capability to fly--a capability apparently impeded by feelings like grief. In fact, it can be fatal: if the player does not talk to Cortez a sufficient number of times in the game to help him recover over the loss of his husband--regardless of if the player chooses to romance him or not (or cannot due to playing as a female Shepard)--he will die on the final mission of the game, shot down and killed by a missile that will only damage his shuttle instead if he has fully “recovered.” While Shepard may tell Cortez at a scene in front of a military monument that “your past is yours--no one can take it away,” the whole purpose of his storyline is, essentially, to wipe it clean and replace it with a suitably acceptable and productive emotional outlook; even the last recording of his husband Robert just before he is killed actively tries to stamp out their past, begging “I know you. Don’t make me an anchor. Promise me, Steve.” The potential queer resonance of looking back--of seeing a history marked with loss and refusing to “move forward” from it, to reject a normative arc of restoration and reestablishment within monogamy--is here a fatal allure, and one that wastes both time and resources. Everman even notes that Cortez’s past history (in a use of economic language that again stresses queerness as a resource) is there to quickly label him as gay and then move forward: “[w]hen Cortez says 'I lost my husband', every player knows his sexuality, so precious word budgets aren't spent to establish that fact. Instead, the time is spent bonding over past losses and future hopes" (Purchese, 2012). In order for Cortez to ever see those hopes, he must be pointed forward: toward Shepard, towards the mission, towards the future.

These same logics extend to Cortez’s feelings toward Shepard, particularly if they have entered into a committed relationship to one another. In a scene available in the Citadel downloadable content, a romanced Cortez explains his role within the game and within Shepard’s life in a speech that encapsulates the idea of identity and affection as resource:

I’m not just a shuttle pilot. I’m your shuttle pilot. When you’re approaching a landing zone, you’re just another soldier. Vulnerable. Nothing you can do if we’re shot down. Getting you to the ground alive is a responsibility I can’t give to anyone else. I love you.

What Cortez means to Shepard--and Shepard to Cortez--is a direct extension of his primary gameplay mechanic. The irony of the game’s encoded mechanics meaning Cortez can indeed never give anyone else the opportunity to get Shepard to the ground aside, the depths of their affection are driven by his capability to execute a role; Cortez takes pains to stress he is “your” shuttle pilot, the dividing line between vulnerability and the completion of another successful mission. Ensuring Shepard stays alive is what draws out his declaration of love: I serve, therefore I care. His use value is also the central component of their romance.

While Cortez sees himself as a vital resource to the cause, Traynor is given far less opportunity to integrate herself into the role of gameplay, often used as a disembodied voice announcing to Shepard that an important email has arrived for him or her. Her job is largely coordination, ensuring the player is aware of important missions and staying on task; in fact, she serves as the initial tour guide to Shepard’s ship, the Normandy, pointing out various rooms the player will repeatedly visit and their gameplay purpose. Otherwise she is largely peripheral to the game’s central mechanical loop, outside the action, occasionally noting that “it was fairly intense up here. I can only imagine what it was like down on that moon.” And compared to the wartime journey of grief and pain Cortez goes through, Traynor’s main trauma is a toothbrush she left on earth “worth 6,000 credits”: a decidedly different quantification of loss. Her storyline, and its stakes, are decidedly softened from Cortez, and the near invisibility of her character on a gameplay level again reiterates the habitual invisibility of lesbian identity within a variety of media. For many players, their only engagement with Traynor will be to hear her remind them that the galaxy needs saving--and it can’t be done without them answering that vidcom and jetting off to the next planet.

However, when Mass Effect 3 does choose to make Traynor visible, it is her sexuality--and specifically her body--that end up being deployed as a resource of titillation. Traynor is sexualized from the moment she appears, apologizing to the ship’s female-identified AI for “all those times I talked about how attractive your voice was,” and later finding an excuse to show up in Shepard’s cabin to take a shower with little to no explanation as to why. While word budgets may be precious, the game finds sufficient time in Traynor’s romance storyline to strip her down to her underwear twice: once in the aformentioned shower scene where she first has sex with Shepard, and again in a final rendezvous before landing on Earth. This also occurs in Citadel, where a conveniently located hot tub once again provides the opportunity for Traynor to shed clothing. A variety of potential lines from Shepard in a later dialogue sequence, claiming that “my shower is for winners” and that Traynor “hit the showers” after winning a board game, similarly loop around to the prioritization of when and how her body will be exposed. Cortez, however, is only seen sexually with a male Shepard once in a far less explicit and brief sequence. While the game may present a 22nd century apparently open to all gender preferences, the 2012 audience it clearly caters towards wants a female body presented as often as possible within the game’s “limited” resources--and two male bodies kept off screen.

Yet just like Cortez, Traynor repeatedly returns to one central theme: how proud she is to serve the military effort, and to serve Shepard. “If anyone in the galaxy can stop the Reapers, it’s you. And if flagging your messages and managing strategic intel helps you in any way, then it’s worth it,” she tells Shepard in dialogue, affirming both her role as subservient gameplay support and also the ultimate power fantasy of the game. In fact, it is her role in the storyline that ensures the game’s core military conflict moves along successfully, as the ship’s computer tells Shepard “the accuracy of our war room data is a direct result of her work.” She is an Oxford graduate, an Alliance scholarship-winner, and a devoted servant to the cause; if Cortez gets Shepard to the ground to fight the battles, Traynor ensures the math behind the battles adds up. The two most prominently advertised gay and lesbian characters turn out to be central non-playable facilitators of the imperial effort, and draw strength from their role as resources. “I feel like I’m actually being useful,” Traynor admits to Shepard, a resonant line on a number of levels: “useful” as a representational marketing hook, a coordinator of untold numbers of bodies transformed into “war room data,” and as a ready shower companion.

From Representation to System: Tracing the Biopolitics of the War Room

While I have focused thus far on questions of narrative themes and character depictions, these elements serve to foreground an even deeper level of “valuing” queerness and bodies that is, in many ways, the central gameplay mechanic of Mass Effect 3. As the conclusion of a series built around branching storylines--not to mention the possibility of having the majority of Shepard’s crew dead by the end of Mass Effect 2--the prospect of writing a game that could account for and actively utilize each outcome of those prior storylines left BioWare’s writing staff in a tough situation. Lead writer Mac Walters admitted this issue in an interview with game website GameTrailers, explaining that “Mass Effect has been the ultimate example of tying up loose ends. We did some in ME2, more like dealing with consequences from the original, but we knew that ME3 had to be an amazing story regardless of what the player's choices were previously” (Kayser, 2012). If, as the first Mass Effect promised, the fate of the galaxy depended on your actions, Mass Effect 3 had to present a series of fates built around a multitude of variables: in essence, a narrative funnel that could catch and collect any number of possibilities and convert them into a small, contained set of conclusions.

To do so, Mass Effect 3 presents the most narrow, direct experience of the series, both narratively and thematically. In contrast to the nebulous sprawl of Mass Effect 2, which features players drifting about the galaxy on a series of loosely connected missions, the final game sets the player on a very clear story arc in order to drive home the fact the galaxy needs saving immediately. Indeed, Mass Effect 3 is a game both about military conquest and also designed in a direct reflection of exceptionalist military logic; for a game ostensibly about saving the entire galaxy, it is one obsessed about saving humanity first and foremost, with the idea that the other alien species will naturally benefit from this effort. In its efforts to make the player feel meaningful and empowered in the scale of her decisions, Mass Effect 3 transforms the entire universe into an agency-less resource pool: biopolitics on a galactic level, with populations either brought into normative line with the goal of saving the world or wiped out altogether. Patterson notes this struggle in his reading of the game’s political arc, specifically in the player’s role as a deployer and purveyor of labor, as “by putting the player in a position to evaluate racial attributes and manage teammates, Mass Effect [3] challenges the player to derive military labor from otherwise disinterested teammates” (2015, p.217). The power fantasy at the core of the game, with the player-character as the literal Shepard of the galaxy, gains its charge from the extent by which the eventual work, life, and death of various bodies feel sufficiently bound to and motivated by the player’s choices.

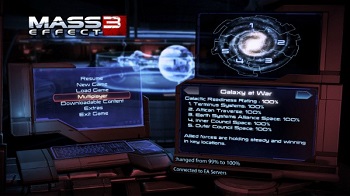

Figure 1: The “Galaxy at War” screen. (Source: Mass Effect 3)

This biopolitical logic becomes clear before the player even has a chance to begin playing the game. The opening menu, from which a new game can be selected, bears a large map on the right side of the screen declaring “Galaxy at War,” with a series of numbered quadrants and percentages displayed (Figure 1). These percentages add up into the “galactic readiness rating,” which indicates how prepared each part of the galaxy is to help combat the Reapers. Immediately, the prospect of any intimate knowledge of what these sections contain--or who or why they have chosen to fight--is reduced to a numeric value of usefulness; the player does not need to know who or what exactly is in the Terminus Systems, only that they are anywhere from 50 to 100 percent ready to help her win the war. Of course, the systems are unable to raise these numbers themselves, as the only way to increase these ratings is for the player to participate in the game’s multiplayer modes (a new addition in Mass Effect 3) and repeatedly fight staged battles in each of the regions to drive the percentage up. Nor can the player stop fighting, as the game has a built-in system that reduces the percentage for every day spent away from participating in the multiplayer mode. It is an endless cycle of repetition, driven not by any specific attachment to the regions being “readied” but by the numbers fluctuating up and down every time the player wishes to begin playing [3].

Figure 2: The “war assets” display. (Source: Mass Effect 3)

The readiness rating ultimately serves as a multiplier for the “war assets” score earned in the single-player mode, the final total of which serves as the scale for both what endings are available to the players and how “victorious” those endings are. War assets constitute a variety of things: weapon caches, spaceships, computer systems, and--most strikingly--specific people and populations, all of which are given different point values according to their apparent usefulness to the war effort and its “effective military strength” (Figure 2). In fact, all of the major decisions in the game boil down to the ability to increase this score; at numerous turns, Shepard is placed in a position of deciding whether or not to allow the whole-scale annihilation of an entire alien species due to the fact it will conflict with recruiting another, more “valuable” population to his or her cause. These decisions can usually only be avoided by a carefully established history of choices across the entire series; for a player who plays Mass Effect 3 with no save data from a previous file--or made the wrong decisions on an existing file--no such option will be available. Avoiding genocide is handed out as a reward for playing the “correct” way; for all other players, they will witness at least one entire race die as a direct result of selecting one military option over another. And ensuring a human future takes precedence over all others, as Shepard’s early lines to a military council on Earth--declaring that “we fight or we die”--are often transformed into “we fight, so you die” on the galactic level.

In many ways, Mass Effect 3 turns what had been a narrative theme in Mass Effect 2 (the dangers and risks of what populations matter) into the primary system of play--a distinction captured by the way each title deals with the same storyline built around biopower and reproduction. One of the central paragon/renegade choices in Mass Effect 2 deals directly with the threat of dangerous, destructive pleasures being linked to non-reproductive bodies, a recurring narrative theme in the game and one increasingly driven by questions around biopower and reproduction. Mordin, an alien scientist recruited to the team, reveals that years before the game’s events, he developed a sterility plague known as the “genophage” to be used upon the krogan--a large, reptilian alien species known throughout the galaxy for their prowess in combat and ruthless nature. Instead of enforcing total sterility, the genophage limits the amount of live births to roughly one in a thousand, crippling the krogan’s ability to spread and leaving their population decimated. Mordin describes the logic behind the genophage as constructed from “millions of data points, years of arguments, countless scenarios” which showed the krogan spreading beyond their means and violently conquering most of the known galaxy. Claiming the options were “genophage or genocide,” Mordin notes the ratio of one in a thousand was decided upon as the “perfect target, optimal growth. Like gardening.”

Following in this need to regulate life and control populations, Mordin’s continued discussion of the krogan takes on a decidedly racialized component as well. The krogan are described as violent, primitive, and uncivilized, having reduced their world to a “nuclear winter” in previous civil wars and now subsisting on a “war economy.” Patterson notes this in his reading of the krogan squadmate Wrex from the original Mass Effect, “who must either be trained to submit his military labor power to the multicultural alliance or be killed for corrupting the multiculturalist imperium as a terrorist-monster” (2015, p.218). Krogan are said to spread too fast, have limited culture, possess little government of their own, lack recognition from the Council government, consist of a “bloodthirsty army” and are guilty of “war crimes.” Through this language, the statistical evaluation of “data points” and “countless scenarios” for the genophage turns resistant bodies into statistics--and eventually, into plants, removed of subjecthood and evaluated along the lines of “proper” growth.

The genophage is Foucault’s concept of biopolitics written large, focused upon “the species body, the body imbued with the mechanics of life and serving as the basis of the biological processes: propagation, births and mortality…effected through an entire series of interventions and regulatory controls” (1990, p.139); the power to control life rises over the threat of looming death, born out in Mordin’s statement that “[we] could have eradicated [the] krogan but chose not to.” Thus the krogan become flowers to cultivate, populations to control for the sake of galactic stability. Puar notes that “the biopolitics of regenerative capacity already demarcate racialized and sexualized statistical population aggregates as those in decay, destined with no future, based upon whether they can or cannot reproduce children” (2007, p.211); here, by ensuring the decay of a racialized Other, the galactic government ensures the data will match the biopolitical mandate. In fact, it is deployed for their own good; according to Mordin, the genophage is “not punishment” but the ideal way for them to live.

In Mass Effect 2, this storyline is largely used as a means of developing Mordin as a character and establishing the larger implications of certain actions between alien species. By Mass Effect 3, however, the genophage is actively folded into the mechanics of the war room as a means of obtaining bodies for the galactic battle. Shepard, realizing the krogan would make useful soldiers against the Reapers, finds out that one fertile krogan female still exists in the galaxy--and is being held by the salarians, who created the genophage in the first place. The possibility of a krogan future--sustained biologically--is thus dangled in front of them as incentive for fighting the Reapers, and in front of the player in having a valuable war asset to add to the equation; however, should the player manipulate the situation in the right fashion, Shepard can actually fake giving them a cure for the genophage and earn their numbers without actually changing their reproductive fate. In fact, in terms of sheer asset numbers, this is the best possible outcome: the salarians are satisfied due to the fact the krogan remain sterile and donate their warships, while the krogan--unaware they have been duped--donate soldiers to fight on Earth as well.

The player who chooses this route may find herself confronted by Mordin himself, who has had a change of heart about his decision; yelling at Shepard, he declares, “I made a mistake! I only saw the big picture. Big picture made of little pictures. Too many variables. Can’t hide behind statistics.” Yet this is exactly the logic of Mass Effect 3: a game made up primarily of a big picture that visually confronts the player the moment she opens the game and manifests itself in a statistical model made up of variables that dictate the future of the galaxy. Whatever sense of moral guilt the player may feel over the decision (and the game does mark it as heavily on the “renegade” spectrum), Mass Effect 3’s overriding model of the war room ultimately marks it as a valuable choice, in the most basic sense of the word. And those valuable choices will always be added together in the background by a “useful” queer figure, while another awaits the opportunity to fly Shepard down to the next population to be quantified.

This division between Mass Effect 2 and 3 of how bodies are regulated and counted on a systemic level takes an even queerer turn via the character of Morinth. Introduced in Mass Effect 2, Morinth is a potentially recruitable alien character with “a rare genetic disorder” that causes her to kill whomever she sleeps with. It is “an addictive condition,” manifesting at sexual maturity and advancing with each fatal union. Known as “Ardat-Yakshi” (“demon of the night winds”), these individuals are offered upon being diagnosed the chance to live “in seclusion and comfort,” hidden from society. Some, however, are too “addicted to the ecstasy” gained from fatal sex, and escape to other worlds. Immediately, the parallels between Ardat-Yakshi and what Lee Edelman deems sinthomosexuality--“the cultural fantasy that conjures homosexuality, and with it the definitional importance of sex in our imagining of homosexuality, in intimate relation to a fatal, and even murderous, jouissance” (2004, p.39)--become apparent. Plagued by a genetic aberration that develops over time and driven by the need for “ecstasy” that only comes from deviant sex, Morinth is constructed by her mother as a “demon,” a queer vampire that feeds on pleasure by “hunting” for bodies in the hedonistic space of nightclubs. [4]

The desire, only growing with each union, is not resisted but indulged; her mother’s comment that “if Morinth does not want to be cured, she won’t be” evokes any number of contemporary discourses on homosexuality as a “curable” condition with the proper willpower and attitude. The comparison becomes even more blatant when consulting the codex entry in the game’s menu on Ardat-Yakshi, where “contrary to popular belief, Ardat-Yakshi are neither extremely rare (around one per cent of asari dwell on the AY spectrum), nor are they all murderers. Most cultivate and discard countless exploitative or abusive relationships during their legally marginal lives… by nature Ardat-Yakshi are incapable of long-term cooperation.” [5] As a “legally marginal” population minority incapable of “long-term” relationships, Ardat-Yakshi represent in the Mass Effect series not only the “fatal lure of sterile, narcissistic enjoyments” (Edelman, 2004, p.13), but an entire wealth of assumptions about queer life in general.

Should the player have recruited Morinth in Mass Effect 2, she sends Shepard an email early in Mass Effect 3 noting how she had to leave his crew, as “we both know the Alliance wouldn't take too kindly to my presence there… I'm still grateful you took a chance on me. Take care of yourself. I'd hate to hear you were killed before we get the chance to meet up again.” No such option will ever occur, however. Unlike the numerous reunions with former crew that pepper Mass Effect 3, Morinth can only appear in one way: as a repurposed Reaper creation called a Banshee, which the player must kill while retaking Earth (Figure 3). The game does not even acknowledge the act has been done, as no comment is made by Shepard or the crew after her death; in fact, it is entirely possible to miss she is there at all, as the only sign of her identity is the small name label over her health bar. Instead, she becomes one more monstrous obstacle in the path of preserving the proper future, as apparently do the rest of her kind--the Codex entry on Banshees claims they can only be made from Ardat-Yakshis, whose genetics make them incapable of reproducing and only able to bring about death through sex.

Figure 3: Morinth as monstrous transformed Banshee. (Source: Mass Effect 3)

Compared to any other squadmate who survived Mass Effect 2, all of whom end up being potentially usable as literal war assets who add to the galactic readiness score, there is no Mass Effect 3 in which Morinth can “count.” While she may be grateful for it on a narrative level, taking a chance on Morinth means a net gameplay loss, and with no husband or picket-fence hopes in front of them, she and all other transformed Ardat-Yakshis end up unidentified, unacknowledged cannon fodder. They are a resource only usable by the side of destruction, and as such must deny themselves or die; in fact, Mass Effect 3 goes so far to send the player to an Asari monastery of sorts where Ardat-Yakshis have willingly isolated themselves from the rest of the galaxy for the greater good, docile and self-sacrificing to ensure their “legally marginal” lives do not taint any others. These are, in essence, the options allowed to queer bodies in Mass Effect 3: streamline the biopolitical math like Traynor; serve alongside the war effort like Cortez; remain quietly on the sidelines like the Ardat-Yakshi; or, to draw from Patterson, die as Morinth does, an unacknowledged terrorist-monster threatening the multicultural alliance.

Conclusions: Beyond Machine Thinking

At the end of Mass Effect 3, a bloodied, battered Shepard argues for the future in front of the leader of the Reapers: an AI program called the Catalyst, whose original purpose was to find a solution to the growing conflict between organic life and its synthetic creations. After observing the conflict, the Catalyst concluded that synthetics would always destroy their creators, thus necessitating the “harvest” of advanced organic civilizations to preserve their genetic essence while also destroying their existing synthetic creations. On a loop every ten thousand years, the Reapers come back, wipe the slate clean, and leave the most primitive organic civilizations alone, returning again once they too develop synthetic life. “Like a cleansing fire, we restore balance,” the Catalyst claims, preventing the “chaos” of conflict from ever tipping too far in one direction to completely destroy organic life.

Shepard, of course, initially rejects this “inhuman” line of thinking; the player may have him or her tell the Catalyst that “[t]he defining characteristic of organic life is that we think for ourselves, make our own choices. You take that away, and we might as well be machines just like you.” Yet this elides over the increasingly visible fact that the player has been asked to think like a machine the entire game: she, too, has been focused on the task of saving the future through following a central equation, potentially annihilating entire civilizations herself in the goal of finding the proper numeric war asset “solution” to the Reapers. In fact, the number of choices the player has in her confrontation with the Catalyst is entirely dictated by the value of the war value score. If Mordin cannot “hide behind statistics,” neither can the narrative.

While Mass Effect--and BioWare more generally--may represent LGBTQ characters, it cannot truly represent queer life, queer possibilities, so long as these representations remain tethered to and in service of a set of dehumanizing, abstract gameplay systems that prioritize above all else efficiency, military dominance, and loyalty to the larger nation-state. Queerness that is only rewarded, only “counted” when properly subsumed within these systems, is not the goal we are fighting for, no more than acknowledging queerness for its willingness to stand behind a military uniform. Here, Chang’s demand for queergaming to include “full, dimensional, consequential, variegated, and playable experiences, lives, bodies, and worlds” gains an even more urgent charge (2017, p.22). The more these rhetorics find an established and unquestioned home within games under the guise of progressivism, the more difficult it will be to articulate a resistance against them. Games must look beyond “machine thinking” and towards new storylines, new dynamics, new ways of prioritizing the player experience beyond dominance and power. A future where BioWare games feature a set of queer characters whose worth is established on terms beyond their eventual use and support of missions of conquest within a biopolitical context might welcome an equally intriguing possibility, and one likely necessary for the former to happen at all: a BioWare game without missions of conquest.

Endnotes

[1] It is this system of “paragon” and “renegade” that first establishes how equations fuel Mass Effect’s idea of choice and consequence. The more actions the player commits that are marked as a particular moral category, the more that category’s scale fills up, with the first Mass Effect quite literally displaying the moral value of the player’s action (such as “Paragon +24”). The higher the number, the more players can choose certain persuasive options in dialogue and gain an advantage in situations. By Mass Effect 2, however, an equation running in the background evaluates the player on how consistently they have chosen particular options, not just the cumulative moral score. A player may disagree with the given Paragon or Renegade option in a situation but chooses it nonetheless to maintain a necessary numeric level of ideological “stability” and unlock top-tier persuasive options. Thus, the only way to be “free” to choose certain outcomes in Mass Effect 2 is sticking with a repetitive set of binarized moral decisions.

[2] Shortly after the release of Mass Effect in late 2007, a news article titled “Sex in Video Game Makes Waves Through Industry” appeared on a conservative Christian news website called the Cybercast News Network, claiming Mass Effect “even goes so far as to allow homosexuality to be on par with heterosexuality and heterosexuality outside of its proper context of marriage” (Moore, 2008). This was echoed by conservative blogger Kevin McCullogh in a post entitled “GAMER rights to lesbo-alien sex,” where he claimed rather vividly that the game was “customized to sodomise whatever, whomever, however, the game player wishes.”

[3] While the multiplayer is free to play initially, it also contains a variety of randomized item packs that the player can pay for immediately rather than wait to earn points through play to access them. Thus, it is also decidedly profitable for BioWare to continually send the player to this section of the game, hoping that she will eventually decide to pay real money in order to speed up improving her combat skills.

[4] This point is driven further home by the fact she escaped her home planet on a ship called the Demeter--the name of the vessel Dracula traveled on to London.

[5] Further sections of the codex claim that “Asari psychologists regard this incapacity for mental fusion as preventing the development of empathy, leading to psychopathy. There is no known cure.” Thus the Ardat-Yakshi are linked not only to death, but the diagnosis of mental illness, tying the historical connection to queerness even further.

References

Bogost, I. (2007). Persuasive games: The expressive power of videogames. Cambridge: MIT Press.

---. (2008). The rhetoric of video games. In K. Salen (ed.), The ecology of games: Connecting youth, games, and learning (pp. 117-140). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chang, E.Y. (2017). Queergaming. In Ruberg, B. and Shaw, A. (eds), Queer game studies (pp. 15-23). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Condis, M. (2015). No homosexuals in Star Wars? BioWare, ‘gamer’ identity, and the politics of privilege in a convergence culture. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 21(2), 198-212.

David, B. (2012, March 8). Mass Effect 3 'gay romance' slammed by Metacritics. GMA News Online. Retrieved from .

Dyer-Witheford, N., and de Peuter, G. (2009). Games of empire: Global capitalism and video games. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Edelman, L. (2004). No future: Queer theory and the death drive. Durham: Duke University Press.

Foucault, M. (1990). The history of sexuality - Volume I: An introduction. Trans. R. Hurley. New York: Vintage Books.

Frank, N. (2017, December 18). Trump is forcing the military to lie in court about the transgender troops ban. Slate. Retrieved from https://www.slate.com.

Glassie, S. (2015). ‘Embraced eternity lately?’: Mislabeling and subversion of sexuality labels through the Asari in the Mass Effect trilogy. In M. Wysocki and E.W. Lauteria (eds), Rated M for mature: Sex and sexuality in video games (pp. 161-174). New York: Bloomsbury.

Ingraham, C. (2017, July 26). The military spends five times as much on Viagra as it would on transgender troops’ medical care. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com.

John, T (2010, April 5). BioWare explains why there's no homosexuality in Mass Effect 2. 1Up Games. Retrieved from http://www.1up.com.

Kayser, D. (2012, February 13). Mass Effect 3 - lead writer Mac Walters on crafting a conclusion for the masses. GameTrailers. Retrieved from http://gametrailers.com.

King, C. R, and Leonard, D.J. (2010). Wargames as a new frontier: Securing American empire in virtual space. In N.B. Huntemann and M. Thomas (eds), Joystick soldiers: The politics of play in military video games (pp. 108-122). New York: Routledge.

Moore, E. (2008, January 11). Sex in video game makes waves through industry. Cybercast News Service. Retrieved from http://www.cnsnews.com.

Patterson, C. (2015). Role-playing the multiculturalist umpire: Loyalty and war in BioWare’s Mass Effect series. Games and Culture, 10(3), 207-228.

Puar, J. (2007). Terrorist assemblages: homonationalism in queer times. Durham: Duke University Press.

Purchese, R. (2012, May 8). How BioWare wrote gay Mass Effect 3 romances. Eurogamer. Retrieved from http://www.eurogamer.net.

Roberts, S. (2017, July 27). Transgender liberation won't be found in the military. Truthout. Retrieved from http://www.truth-out.com.

Ruberg, B., and Shaw, A. (2017). Introduction: Imagining queer game studies. In Ruberg, B., and Shaw, A. (eds), Queer game studies (pp. ix-xxxiii). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Schaefer, A.G., Iyengar, R. Kadiyala, R.S, Kavanagh, J., Engel, C.C., Williams, K.M., and Kress, A.M. (2016). Assessing the implications of allowing transgender personnel to serve openly. Washington: RAND Corporation.

Spade, D. and Willse, C. (2014). Sex, gender, and war in an age of multicultural imperialism. QED: A Journal in GLBTQ Worldmaking, 1(1), 5-29.

Zekany, E. (2016). “A horrible interspecies awkwardness thing”: (Non)human desire in the Mass Effect universe. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 36(1), 66-77.

Ludography

BioWare. (2010). Mass Effect 2. Electronic Arts.

BioWare. (2012). Mass Effect 3. Electronic Arts.

BioWare. (2014). Dragon Age: Inquisition. Electronic Arts.