Playing Virtual Jim Crow in Mafia III - Prosthetic Memory via Historical Digital Games and the Limits of Mass Culture

by Emil Lundedal HammarAbstract

This article critically evaluates Alison Landsberg’s concept of prosthetic memory by applying it to the historical digital game Mafia III. Via an array of player perspectives, I emphasize how players activate the game’s prosthetic memory-making potentials of 1960s Southern US in relation to white supremacy, masculinity, and counter-hegemony. Yet despite its explicit politics, I argue that Mafia III’s context of production limits critical practices of play. Likewise, I consider instances of non-black players who recreationally consume Mafia III’s politics. I thereby show the significance of racial and materialist approaches to memory-making in games when considering the exploitative relations across the contexts of both production and consumption of digital games. As such, I argue that promises of empathy and alliances via mass media, as prosthetic memory holds, are inadequate in contemporary white supremacist, patriarchal capitalism, and accordingly, materialist and power-hierarchical approaches to games enable deeper understandings of their negotiated meaning-potentials.

Keywords: prosthetic memory, historical games, white supremacy, masculinity, political economy, materialism, mass culture, cultural memory, race, capitalism, mafia, organized crime

Introduction

Relatively little attention in both game and memory studies has been paid to Alison Landsberg’s concept of ‘prosthetic memory’ and its role in analyzing historical digital games, especially with regards to its political promises. As a mass cultural medium, historical digital games are ripe for analyzing how understandings of the past are formed in the present and their political ramifications. This article contributes to this dialogue by bringing prosthetic memory to bear on Mafia III (Hangar 13 & 2K Czech, 2016) with special attention to its contexts of production and reception, and racialized oppression in and beyond the game itself. As I argue, consideration to these contexts is significant for the analysis of cultural memory in games, as it exposes the tensions derived from contemporary power hierarchies, such as race, in how the political economy of a game tends to structure its form, which in turn is received and negotiated by players in their own contexts.

First, I define the affective potentials of prosthetic memory shaped by mass cultural media, and their empathetic potential to foster political alliances across differences of identity. Then I critically apply prosthetic memory to an analysis of Mafia III, a game that situates players in 1960s US white supremacy in New Orleans during the Civil Rights era. In applying the concept, I use my own and publicly available player testimonies by Anglophone scholars, writers, and critics to draw out Mafia III’s memory-making potentials, which in turn highlights how its form predisposes practices of play. Through these perspectives, I investigate how the game invites prosthetic relations to a past and an identity which some players have not lived, with an attention to the game’s use of racial violence and Jim Crow laws. In line with Landsberg’s claim that mass-disseminated memories elicit affective responses to motivate political alliances across differences, Mafia III might similarly be seen to invite empathetic relations to black political struggles for players unfamiliar with racialized oppression. However, similar to TreaAndrea Russworm’s (2017) and David Leonard’s (2016) arguments on the promise and limits of ‘racial empathy’ through digital games, I criticize the empathetic potential of prosthetic memory by introducing critical race-theoretical and materialist perspectives, which suggest that mass culture and its political-economic conditions churn out products for pleasurable consumption by dominant audiences divorced from political action and genuine empathy. In turn, these criticisms problematize the viability and promise of prosthetic memory and point to the complexity and ambivalences of the cultural memory found in mass cultural products such as Mafia III and the global power hierarchies that produce them. Finally, I argue that such promises of memory-making need to be re-evaluated and instead must consider relations of power and political economy of mass culture to better encapsulate the implications of memory-making.

Cultural & Prosthetic Memory

Cultural memory studies focuses on how culture mediates the past in the present via artifacts “from hand-crafted manuscripts to the printing of books, from the crafted singular image to the mass production of photography and films.” (Reading, 2016, p. 1). On the basis of these cultural expressions, individuals and collectives interpret and negotiate the past in sociocultural contexts (Erll, 2011, p. 101). By analyzing these objects and considering the differing affordances of their various forms (Rigney, 2016, p. 67), it is possible to identify certain memory-making potentials that audiences might, or might not, activate. Here, Landsberg (2004, 2015) proposes the concept of prosthetic memory [1] to account for how mass cultural media can create an artificial ‘mnemonic limb’ for their audiences. For instance, she argues that the audiovisual nature of film has altered people’s bodily relation to the past to the extent that audiences of mass culture are now vicariously relating to a historical event “as an experience that they have actually lived through.” (2004, p. 180). Referencing phenomenological approaches to film spectatorship as embodied experience (Sobchack, 1992), Landsberg is interested in how mass media, such as film, “[…] engages us in a bodily way: haptically, aurally, visually.” (2015, p. 30). Thus, when watching a historical film about the Holocaust, for instance, audiences are physically affected by and emotionally identifying with what happens on screen. This bodily, affective engagement enables audiences to form what Landsberg calls ‘a mnemonic limb’, meaning a sensuous prosthesis formed from the affective engagement with historical mass media, i.e. cultural constructions. As such, prosthetic memory refers to how contemporary mass media enables the formation of sensuous mnemonic limbs in audiences. Since its introduction, prosthetic memory has been applied across studies of cultural memory and media (e.g. Arnold-de Simine, 2013; Hirsch, 2012; Koss, 2006; Tybjerg, 2016), yet only two articles explicitly apply prosthetic memory to documentary games (Andersen, 2015) and military shooters (Cooke & Hubbell, 2015), respectively, but without much consideration to its political-economic implications. This consideration serves as the motivation for this article.

Opposing “those critics who see the commodification of mass culture in purely negative terms” (2004, p. 20), Landsberg optimistically claims that this affect via mass media enables the formations of political alliances between social groups (2015, p. 3), where audiences establish empathetic relations to the other groups (ibid, pp. 32-33). Landsberg uses Deborah Gould’s (2010) research on how affect motivates politics to state that prosthetic memory’s affect drives audiences to empathy and political action. She exemplifies this with the depiction of black US diaspora in the film Rosewood (Singleton, 1997) and the TV-series Roots (1977) from which, according to her, non-Black US people can learn “to see the world through black eyes”, which “[…] might have a radical effect on both their worldview and their politics.” (Landsberg 2004, p. 83). By forming an affective relation to the Black US diasporic past via the audiovisual medium of television and film, prosthetic memory “might be instrumental in generating empathy and […] an ethical relation to the other” (ibid., p. 149). This empathy is enhanced further by the mass production of culture in contemporary global capitalism, in which “commodification […] makes images and narratives widely available to people who live in different places and come from different backgrounds, races, and classes. […] (2004, p. 21). From this perspective, the extensive reach enabled by mass cultural media allows for a widely disseminated politics of recognition and empathy between disparate groups in the formation of prosthetic memory. Similar research on empathy in games have found place in game studies (de Wildt, Apperley, Clemens, Fordyce, & Mukherjee, 2019; de Wildt & Aupers, 2019; Fordyce, Neale, & Apperley, 2018; Leonard, 2020; Russworm, 2017; Smethurst & Craps, 2014; Wilde & Evans, 2019), a discussion I critically return to later in this article.

Chief among the critics of prosthetic memory, Berger (2007) wonders if we have not always used prosthetics to learn what others feel and think and that text likewise produce sensuous memories for their readers. Berger also contends that Landsberg builds “on a now longstanding scholarly literature that finds subversive, counter-hegemonic, liberatory potentials in popular and mass culture.” (ibid. p. 601). Thus, he argues, prosthetic memory is not novel or different from previous insights into how people communicate through media and form understandings of the past and each other. In her response, Landsberg states that it is the mass commodification that sets prosthetic memory apart from previous technologies of memories, “all for the price of a ticket” (Landsberg 2007, p. 628). Her goal, she argues, is “not to be a defender of the global economy” (ibid.), but rather find the radical potential in mass culture. Yet as I will show later, the concept of prosthetic memory overlooks the material conditions of mass culture, its political economy, and its hegemonically structured consumption that disarm the political potentials of prosthetic memory. As research into the global production networks of contemporary digital mass media shows, the inherent environmentally degrading (Maxwell, Raundalen, & Vestberg, 2014), inhumane and exploitative conditions (Fuchs, 2017; Qiu, 2017) that enable mass media may exclude whatever empathetic potential for inclusion and understanding such media might enable on the level of reception. This is especially evident with contemporary digital games, which rely on these global production networks (Kerr, 2017) that in turn, I argue, predispose form to reiterate a hegemonic status quo, thereby challenging Landsberg’s view on the radical potential of mass media.

Digital games and memory

While Landsberg focuses on historical films and museums, my contribution moves the analysis to historical digital games. Here, games operate at two levels of meaning-making -- the sign level of audiovisual representation and the system level of mechanics and rules executed by the procedural nature of digital games as software (Aarseth & Calleja, 2015). It is through this mechanical system that games structure player behavior and, along with the signifying level, that enable players to activate their agency in the context of past settings (Pötzsch & Šisler, 2019; Uricchio, 2005). This process is what Chapman refers to as “the particular audio-visual-ludic structures of the game” that “produce meaning and allow the player to playfully explore/configure discourses about the past” (Chapman 2012, p. 42). For example, as I have argued, the historical game Assassin’s Creed Freedom Cry (Ubisoft Québec, 2013) uses the endless mechanical reproduction of slave ships to frame “the historical event through a procedural rhetoric that demonstrates how unassailable the structural and systemic nature of the slave trade was if one chose to resist as an individual” (Hammar, 2017, p. 380). In this example and others (Chapman, 2016; de Smale, 2019; Ford, 2016; Mir & Owens, 2013; Mukherjee, 2017; Murray, 2017; Pötzsch & Hammond, 2019; Shaw, 2015b; Sterczewski, 2016), historical digital games invite players to activate memory-making potentials on the level of both sign and mechanical system. Mafia III similarly uses the interplay of these two levels to form a mnemonic limb and thus serves as a potentially rich example of how digital games invite understandings of the past and how these are formed differently depending on players’ activation of their memory-making potentials [2].

Mafia III’s blend of organized crime fiction and 1960s racial memory politics

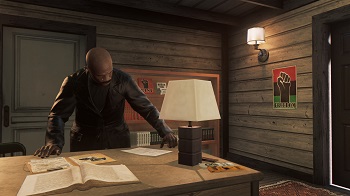

As the third game in the Mafia series, Mafia III follows the same open-world action template that the Grand Theft Auto series (Rockstar North, 1997) made popular -- moving, driving, and limited social interaction with non-playable characters in US urban cities interceded by action-filled combat against virtual antagonists. The first two Mafia games drew on the popular genre conventions of Italian organized crime of New York in the 20th century, thus echoing the popular organized crime genre in film à la Coppola and Scorsese. In Mafia III, the central theme is still US organized crime, but contextualized by 1960s US white supremacy in a fictional rendition of New Orleans, called New Bordeaux. Here, players follow the 23-year old black Vietnam-veteran Lincoln Clay and his vengeful rise through Louisianan organized crime. The plot begins with Clay returning from the Vietnam War and becoming involved in local organized crime via his surrogate family. After helping the Italian Mafia out, they murder Clay and his family. Clay survives and sets out to enact his revenge by conquering the businesses and assassinating leaders of the Italian mafia. With the help of Cassandra (a Haitian crime lord), Vito (an Italian Mafioso), Burke (an Irish mob leader), and Donovan (an ex-CIA agent), Clay ascends the crime hierarchy via brute force and violence while enveloped in the setting of 1960s Southern US white supremacy. Thus, the narrative, the action-filled combat, and the relatively more tranquil moments of inhabiting and navigating a virtual representation of 1960s New Orleans and its racialized stratification, comprise the game’s affective formation of prosthetic memory.

The mnemonic hegemony of violence

In Mafia III, players control Clay via a controller or keyboard & mouse interface from a third-person visual perspective. In activating the game’s mechanical system, players’ primary interactions with the gameworld is violence towards non-playable characters. This is seen where there is a plethora of ways to kill other characters -- beating them, shooting them with a wide array of firearms, driving over them, stabbing them, choking them, and so forth. In addition, the reactions by enemies are animated and presented in high detail with multiple hours of labor spent on depicting the brutality enacted upon these virtual bodies. For example, when players choose to engage a non-playable character via the game’s ‘Brutal Takedowns’ (figure 2), the external camera changes into a fixed camera position with a low field of vision that focuses on the melee execution. If they press the contextual action button on their controller or keyboard, a complex set of motion-captured animations are triggered, where Clay, for instance, punches the enemy character in the stomach so that he bends over, swiftly followed by Clay slamming his military knife through the back of the skull of the enemy character. Along with this brutal set of animations, the audio of the game plays out a relatively loud and deep sound to signal that something noteworthy is taking place, along with the screams of the enemy character and the sounds of punching and knifing through flesh. In addition to both the visuals and the audio depicting the brutality and signifying the audiovisual prominence of this melee kill, the game also sends haptic signals by triggering the two vibration motors of the game controller.

This example, and many similar violent interactions with non-playable characters in Mafia III’s gameworld, highlights how the game’s memory-making emphasizes violence, where camera positioning, complex motion-captured animations, and audio and tactile feedback to players help fetishize it. This priority by the developers arguably means that players form sensuous memories around domination and violence towards others.

For a prosthetic relation to occur, Landsberg (2015, p. 30) writes, audiences have to empathize with the depicted characters and their past. In order to retain player-empathy for a player-character engaging in mass slaughter, Mafia III game justifies it in two ways; firstly, Clay is avenging his family (Blackmon 2017, p. 100), thereby following the received trope of the ‘evil deed’ (Pötzsch 2013, p. 130) that implicitly justifies the violence conducted by players in the game. Secondly, this simulated violence is further justified with the use of selective conflict filters (Pötzsch, 2017), wherein enemies show little humanity and agency. Likewise, by locating it within 1960s US white supremacy, racist white characters serve as prime cannon fodder, while concurrently never surrendering or showing helplessness - i.e. the game’s depictions of violence “morally disengage users by framing violence against seemingly alive characters as an "okay action."” (Hartmann, 2017).

This priority is not necessarily the will of the workers at Hangar 13 and 2K Czech, but due to the political economy of the games industry structuring its type of cultural memories available to players (Hammar, 2019; Hammar & Woodcock, 2019). The publisher 2K Games, like many other investors, sought to reduce financial risks by replicating tried-and-true formula -- utilizing genre conventions, meeting predictable consumer expectations, and targeting imagined demographics (Srauy, 2019). This speaks to an implicit convention within game production and publishing, where higher costs necessitate conservative design that has been honed and evolved over decades (Dyer-Witheford & Sharman, 2005; Nieborg, 2011). As some game writers working in the industry have professed (Bustillos, 2013; Hamilton, 2013; Parkin, 2015; Robertson, 2013), their purpose is to somehow write violent, but relatable characters. Moreover, already when the concept was being developed, 2K Games questioned the size of the potential market due to the game’s racial politics [3]. Again, the design ideal to meet assumed expectations of investors and imagined consumers requires that Mafia III frames possible memory-making potentials to revolve around violence, thereby influencing the game’s textual frames, which predispose players’ prosthetic relation to the game’s historical setting and political topics.

The mnemonic hegemony of masculinity

In addition to this justification of violence, Clay’s character lines up with hegemonic masculinity (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005), via prioritizing the traits of domination, invulnerability, and toughness at the expense of traits like compassion, fragility, and weakness. The scholar Samantha Blackmon observes that Clay is driven “by ambition. He wants to take control of the criminal enterprises within all of New Bordeaux” (2017, p. 100), a claim which is nuanced by the fact that Lincoln implicitly liberates the communities by potentially giving control of rackets to others if players choose one of the three endings to the game’s narrative. The scholar TreaAndrea Russworm remarks in an interview that Clay is not given the opportunity to develop a social relationship that would allow him to display warmth, empathy, and vulnerability beyond his surrogate relationship with Father James (SpawnOnMe, 2016). Moreover, the game’s side-activities similarly follow a certain vision of masculinity: Collecting car magazines, Playboy magazines, 1960s music album covers, and taking down communist propaganda posters (figure 3). Ergo, what gets included and prioritized in the prosthetic memory-making potentials of Mafia III is a certain type of capitalist hegemonic masculinity that emphasize violence, car fetishism, heterosexual titillation, and anti-communism. This hegemonic masculinity also comes at the expense of women in the narrative, where for instance Blackmon identifies how the game reduces the depicted sex workers of New Bordeaux to commodities where Clay is engaging them “not for the sake of freeing the women, but rather because breaking up the prostitution ring will ruin the business of the Sal Marcano […] who has murdered his family.” (Blackmon 2017, p. 104). Given the Mafia series and the genre that Mafia III follows, this hegemonic masculinity seems mandatory and consequently also affects the type of affective relation to the past that prosthetic memory draws attention to.

Counterhegemonic commemorative play

In spite of this focus on both violence and masculinity, Mafia III manages to differ because it is “obsessed not just with violence but the context that this violence happens in.”, as the game critic Javy Gwaltney (2016) writes. I.e. the game centers a black male character navigating 1960s US white supremacy, where its setting, plot, and characters explicitly invoke the racial politics of 1960s U.S. Given Clay’s identity as a biracial[4] main protagonist, he is an atypical character in the landscape of mainstream digital games, where typically white, heterosexual, US men in their twenties to thirties dominate (Fron, Fullerton, Morie, & Pearce, 2007; Gray, 2014; Shaw, 2015a; Williams, Martins, Consalvo, & Ivory, 2009). Likewise, where other high-budget game productions would usually conceal their implicit politics to appease their imagined audiences and avoid financial risk, Mafia III explicitly embraces its racial memory politics of the 1960s Southern US. It is through both Clay as the player-character and the game’s racial politics that the game allows for certain cathartic practices of play. As I have argued (Hammar, 2017), some historical digital games allow for counter-hegemonic play where players activate and play against contemporary hegemony. For example, after playing Mafia III, the critic Tanya DePass (2016) writes that “[T]here is cathartic glee of slamming a racist in the chest as he called me ‘boy’ for merely walking by.” Similar testaments have been professed by the critic Tariq Moosa (2016), who found it “cathartic to play a video game that acknowledges the reality of racism and says: things don’t have to be this way”, while the critic Terrence Wiggins (2016) professes that “it’s all cathartic because we live in a time where a powerful man is allowed to run for the highest public office [Donald Trump] on the ideals of the enemies you face in this game, ideals that should be forgotten detritus from our shameful past.”. Yussef Cole underscores this pleasurable catharsis:

After all, is there anything more satisfying than being able to punch the lights out of a store clerk who says your kind doesn’t belong here, who is threatening to bring the police down on your head? (2018)

As seen in the above figure, the game’s marketing also embraced this cathartic play, where a two-second clip of Clay mowing down Ku Klux Klan members with an automatic rifle was turned into a looping animated image by people looking forward to playing the game (Salazar-Moreno, 2016). This promotional strategy (Wright, 2018) also further complicates prosthetic memory in the sense that although Mafia III depicts a past that these players supposedly have not lived; their activation of the game’s memory-making potentials relates to their own present-day marginalization and oppression.

Foreclosed avenues of counter-hegemony

Yet a critical reader might reasonably ask to what degree is Mafia III counter-hegemonic? Given the game’s emphasis on violence and US masculinity, the game only allows for contexts of counter-hegemonic play when the theme of revenge suits it. For instance, while the game allows players to kill a variety of white supremacists, it implicitly condones capitalism, domination, and US culture in such ways that these other political topics are taken for granted. The critic Miguel Penabella deftly juxtaposes the limits of counter-hegemony Mafia III in:

The unimpeded triumph of black subjectivity amidst racialized violence proves to be a power fantasy, and all the game can do is simply relegate Lincoln within the same capitalist system of institutionalized oppression. He earns money and topples the mafia but remains separated from political engagement. […] Lincoln is rewarded for being part of the same power structure of [sic] his oppressors, reducing success to one’s ability to simply make money. Rather than a fundamental destabilization of power, the same structures are maintained under the guise of completing the overall campaign. (Penabella, 2016)

In the game, Clay seems to solely focus on his revenge, while killing racists is merely a bonus -- i.e. he is only coincidentally concerned with Black justice. Thus, the game enables, but does not enforce counter-hegemonic play, thereby appealing to a wider audience who otherwise would be averse to fighting white supremacy. The lead writer William Harms corroborates this in an interview: “Mafia III is not a game about racism. There’s racism in the game, but our intent was never to make a game about that. It’s what we call a pulpy revenge tale […]” (Martin, 2016) [5] This schism between organized crime fiction and a counter-hegemonic pro-black vision of the past emerges in a scene where captain Cassandra tells Clay that “the only way black folk stand a chance in this city is if we commit to each other”, in opposition to Clay’s obsession with revenge. Here the writers, via Cassandra, comment on Clay’s personal ambition versus the more emancipatory potentials of dismantling white supremacy. The game’s reliance on Clay’s revenge against the Italian mafia as the core part of his motivation obscures the radical potential in centering US black emancipation. Russworm rightly argues that she would have preferred for the developers to go all the way by allowing players to ultimately turn Mafia III’s designed power-fantasy “[…] on the state once and for all, because that’s the fantasy, that’s the ultimate realization of this fantasy -- can revolution be fully realized? […] personal revenge is not the fantasy, it’s not enough. […] it’s revolution that we want” (SpawnOnMe, 2016, sec. 01:37:21). The game already offers up radical commentary and some instances of counterhegemonic commemorative play, yet the main thematic plot of Clay is once and for all confined within the genre of organized crime and revenge fantasy. Mafia III thus excludes emancipatory memory-making potentials by relying on genre and the assumed tastes of hegemonic audiences (cf. Shaw, 2015b), something that Russworm (2016) also identifies as the problem of recognition in pop-cultural renditions of the era.

Past and contemporary memory politics

Still, when compared to other high-budget mainstream digital games that usually shy away from overt political commentary, Mafia III stands out with its prominent depiction of race relations in the 1960s US. Already in the first moments of the game, Clay is called a racial slur by a white character; while his white partner in crime is empty-handed, he must carry big, heavy money bags like a mule; and his presence in white spaces is dismissed by a white security guard as the problems of “Affirmative action […] The whole country’s spinning around the goddamn toilet. […] Sad day when a God-fearing white man can’t get a job, but any old n---- who staggers in is hired on the spot.” Within minutes, the game aggressively signals to players the racial memory politics that await them.

Additionally, while driving around New Bordeaux, players can cycle through different radio stations where for example one white radio host professes white supremacist rhetoric across the airwaves, while on another station called ‘The Hollow Speaks’, a black radio host proclaims dreams of revolution, black power, anti-imperialism, and emancipation from centuries-long oppression. These commentaries are not confined to the game’s fictional world, as the game coincidentally parallels contemporary black US struggles. For instance, one news story revolves around two black men who are shot by Hollis Dupree, a white war veteran, when they asked him for help after their car broke down. As cultural commentators have pointed out (SpawnOnMe, 2016), this story is strikingly like the case of Renisha McBride who was killed under similar circumstances in 2013. Yet Haden Blackman, the director of the game, claims that they did not anticipate these similarities to contemporary struggles against white supremacy, so the motivation for the game’s tie-in with political movements and events were supposedly accidental (Brightman, 2016). Despite this claim, Mafia III still manages to touch on these different stories with commentary apt for the cyclical process of racist violence, injustice in the US legal system, and police authorities that further white supremacy in the US, something of which applies well to how cultural memory always is created in the present. As Blackman went on to say,

Ultimately... if the game can make people think a little bit about race and remind them that Lincoln's experience in 1968 is very different than the experience most of us would have had, and it's similar maybe to some of the experiences some people of color have today, then we've done our job because we've made people think about something that they're not used to thinking about certainly while playing a video game. (ibid. 2016, my emphasis)

This relating the past to the present is echoed in the game’s opening text, which states that the developers “felt that to not include this very real and shameful part of our past would have been offensive to the millions who faced -- and still face -- bigotry, discrimination, prejudice, and racism in all its forms” (my emphasis). The hosts Cicero Holmes and Kahlief Adams remark on this commemoration that it was a “powerful statement”, but also “a preface for white people” (SpawnOnMe, 2016, sec. 01:03:35), as it is meant to highlight the game’s similarities to current US white supremacy, something that might be obvious to US players of color, but perhaps not to those unaffected. These observations arguably indicate this opening text was intended for, i.e. those groups who are not exposed to contemporary forms of racist discrimination and for whom the developers felt it necessary to emphasize that racism still exists today. As such, these instances of relating the past to present injustices affirm the affective formation of prosthetic memory in Mafia III as not just a commentary about past injustices, but also contemporary ones.

Virtual Jim Crow

Moving from its memory politics, I now investigate how Mafia III’s racialized spaces invite prosthetic memory-making potentials in relation to power hierarchies. E.g. Clay’s presence as a black man is highlighted throughout the game’s virtual spaces. In a cutscene where Clay is introduced to the white Italian mafia at the crime boss Marcano’s mansion, a white upper-class woman openly stares at him as he walks through the mansion. Later, another white woman clutches her purse while Clay walks past her. As the critic Shareef Jackson testifies in his analysis of the game: “I've been in those situations now, where if I go in certain offices or to a certain client, and I'm one of the few black people there, and I see this and I notice this and I have other people comment on it, so this is real, real stuff.” (Shareef Jackson, 2016, sec. 16:10). Wiggins similarly tells that that “much like Lincoln Clay in New Bordeaux, I didn’t feel uncomfortable in rich white areas because I didn’t feel like I belonged or was wanted.” (2016). As such, Mafia III’s narrative explicitly treats these racialized spatial dynamics between individual and white supremacy that in turn impact the affective formation of players’ prosthetic memory.

In addition to this narrative representation, the game’s mechanical system also simulates race relations via spatial and timed triggers. Depending on the racial make-up of the neighborhood players are in, pedestrians will yell racial slurs at Clay when players are near them (Wawro, 2017). Similarly, each neighborhood’s racial and class strata also determine how fast police authorities respond to a reported crime; in white affluent neighborhoods, police arrive much faster after characters witness Clay committing a crime than in poorer, black neighborhoods. Likewise, white characters are more likely to call the police if they notice Clay walking around in their vicinity. Here, racial power dynamics are coded into the game that changes states based on the relation between agent and structure (Harrell 2013, p. 62). This narrative and mechanical representation of racialized spaces of Mafia III could aptly be called ‘a virtual Jim Crow’ [6].

This simulation also proves to be a refreshing subversion of other mainstream open-world action games, such as the Grand Theft Auto series. For instance, it is common in the genre to offer different shop-locations that sell commodities for the player to acquire, such as weapons, items, cars and food that replenishes the health of player-characters. Mafia III mimics this aspect similarly with markers on the 2D map showing shops the player can enter, but it subverts this convention via its virtual Jim Crow. Here, the shops in Mafia III with white owners follow the racial segregation laws and therefore exclude Clay from entering and procuring items. For instance, bars and restaurants will have a ‘No Coloreds Allowed’ sign in the storefront, and if players enter, the owners and patrons will verbally abuse Clay and call the police on him. Thus, if players expect a game that functions similarly to the conventional open-world action game, Mafia III’s subversion might elicit reflection on spatial access and genre conventions. In this way, the game disrupts the mainstream games industry’s design reliance on a just and fair meritocracy (Nakamura 2017, pp. 247-8), where publishers otherwise usually let players believe in a fair and just system that awards players.

Through the lens of the prosthetic memory concept, it could therefore be argued that Mafia III’s simulation of white supremacy invites non-black players to form a mnemonic limb of an experience they have not lived. Mafia III exposes players to the audiovisual and virtual texture of everyday racism and more importantly, the institutional and structural forms of oppression based on one’s identity (cf. Murray, 2017). Landsberg’s concept might therefore lead us to the claim that the game as a mass-product could help foster empathy in non-black players, since such groups are taking part in events from the point of view of a marginalized group. Thus, the game’s prosthetic memory as a mass medium might help such players understand the lethality of being a racialized minority and thereby foster an allegiance with the politics that strive to dismantle white supremacy.

The limits of empathy via mass media

Yet if a historical mass cultural medium merely offers an Aristotelian catharsis (Dickey 2015, p. 50) or a pleasure in the pain of others (Sontag, 2004), it is difficult to see political action and allegiance external to Mafia III. For instance, just because a white adult man like myself plays the game does not mean I commit to the political actions needed to rectify past and contemporary injustices towards black US citizens (Russworm 2017, p. 120). Thus, empathy via prosthetic memory needs to be properly considered and evaluated for its optimistic promises of recognition [7].

It is here that bell hooks’ concept of ‘eating the Other’ (1992, p. 21) sheds light on the power position of who is positioned towards who. She argues that oppressed groups are sometimes used in media for consumption by those with spending power. In such cases, marginalized identities are made exotic for dominant identities where the latter fetishizes and consumes the former without a worry or care for the implications of living like this, something that might well apply to Mafia III and unaffected audiences. The commodification of race allows certain groups to become an alternative playground and the tension is located between enabling empathy versus commodifying it. For example, Lisa Nakamura (1995) has analyzed the implications of identity tourism in online virtual worlds, where players of a dominant group adopt marginalized identities in various ways without any personal consequences, while more recently, Souvik Mukherjee (2017, 2018) analyzed the formation of colonizing and colonized players through a postcolonial lens. More broadly considered, within game studies, David Leonard (2004, p. 7) has classified what he terms as ‘high-tech black-face’ in games where upper-class white Americans adopt virtual lower-class Black bodies without worrying about the implications of what such a lived experience actually entails beyond the game itself, as Leonard (2016) later would go on to argue when he contrasts the recreational playing of Grand Theft Auto V (Rockstar North, 2013) to the Movement for Black Lives in Ferguson in 2013. Robbie Fordyce, Timothy Neale, and Tom Apperley (2016) further this topic in their analysis of Everyday Racism (All Together Now, 2015), a mobile game that simulates what it means to experience racism daily. Here, “avatars of colour enable socially progressive acts of empathy”, but also as “available, fluid, and disposable” (Fordyce, Neale, & Apperley, 2016) for white players. I posit that such dynamics are relevant for understanding Mafia III where non-Black players might leisurely engage with it as merely an entertainment product divorced from the racialized experiences and history of U.S. racism. For example, in a guest lecture, Kishonna Gray argues that Mafia III allows for racial tourism in the sense that non-black players get to play as a black man in the 60s, but they “can leave [and are] just there recreationally” (2017, sec. 01:04:50). DePass reverses this observation when she writes that “we don’t get to conveniently turn off our blackness as we try to go out and survive another day." (2016). At the same time, however, recall that critics such as Jackson, Moosa, Russworm, DePass, Wiggins and Cole explicitly professed their appreciation of the game’s power fantasy against white supremacy. For the analysis of games, both the critical analysis of dominant audiences ‘playing the Other’ as well as marginalized players appropriating a game’s meaning potentials to their own ends help highlight the tensions of who is playing, but also to who the game is designed for. Therefore, critical perspectives on both majority and minority players as the ones that I have included throughout help detangle the intricacies of who is consuming who or what with regards to the formation of a prosthetic memory through Mafia III.

Conclusions and future directions

Broadly considered, this article has affirmed the significance of analysis at both the level of production and reception, where the former tends to structure the substance and form of the latter (Mosco, 2009, p. 224). The inclusion of a variety of critical perspectives in the analysis of games can aid as everyday research instruments to account for the multiplicity of meaning potentials that players activate and negotiate, while still paying attention to the broader political-economic background of the contemporary digital games industry that determine the type of hegemonic or counter-hegemonic experiences available to players. My analysis has shown that the concept of prosthetic memory can be used to highlight the memory-making potentials of historical digital games, but with reservations. Additionally, I have shown that digital games convey affective memory-making potentials that players appropriate for themselves as exemplified with Mafia III, where player contexts and contemporary power relations predispose what type of mnemonic limb is created. Here, the games industry’s hegemony of violence and masculinity at the level of production tends to predispose the ways that players play with the past, yet this also offers instances of counterhegemonic commemorative play. Furthermore, the game’s virtual Jim Crow simulates experiences that might be unfamiliar to those unaccustomed to structural and spatial oppression. In contrast, my analysis also complicated this relationship by highlighting who is forming this prosthetic memory and under which circumstances. Via critical-race and materialist approaches, I argued that mass culture can serve as pleasurable entertainment for hegemonic audiences via global production networks. With Mafia III, non-black players can dabble with simulated white supremacy in the game, yet still turn off the computer without those same worries and potentially without any immediate urge to act on behalf of others. Beyond the game itself, Reading’s (2014) materialist approach to cultural memory shows that memory-making via contemporary digital technology relies on the exploitation of workers and the devastation of nature that in turn predispose the memory-making potentials within the medium in question. From the slave labor mining minerals in the Democratic Republic of Congo, to the exploited wage slaves in Chinese tech-factories assembling the media devices to consumers, to the precarious working conditions of software developers in North America and in cheaply outsourced countries like Malaysia and Vietnam, to the e-waste dumps in Nigeria and China, perhaps the question of empathy and political alliances via mass media come at a cost that many, including presumably Landsberg, probably would not be willing to pay. Digital games like Mafia III depend on these unequal global production networks between the exploited and the exploiter, and so too are they affected by their context of production. Thus, the question is if radicalism at the level of meaning in Mafia III ever can resist the exploitative and destructive effects of the imperialist capitalism producing the form. I.e. text (in all its forms) constrains audiences and is itself constrained by relations of production and cultural hegemony. These textual frames invite meaning potentials that are then actively negotiated by situated audiences.

Thus, both contexts of production and consumption should limit the radical potential mass media might hold for political alliances via prosthetic memory. In turn, it is crucial that we consider the power hierarchies of the social contexts in which memory-relevant media are produced, received and adopted. While we should not neglect the significance of counter-hegemonic media that are valuable in themselves (Shaw 2015a, p. 217), neither should we close our eyes to the exploitative system they derive from. Therefore, despite Landsberg’s optimism towards mass cultural media and political alliances, it is not a given that mass cultural media fosters empathy in audiences. Yet it is also evident in the playful negotiations by players like DePass, Wiggins, Russworm, Cole, and many others, that historical games like Mafia III and their memory-making potentials highlight an important conduit and reflection for the systematic struggles that they inhabit, and others perpetuate. This is the tension that optimists and pessimists of mass culture need to be aware of, and in turn, consider materialist and power-hierarchical approaches to their analysis of media in order to enable deeper understandings of their negotiated meaning-potentials.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank both reviewers for excellent feedback, as well as helpful comments and guidance from Holger Pötzsch, Adam Chapman, Souvik Mukherjee, and Pieter Van den Heede, and finally a huge gratitude to TreaAndrea Russworm for letting me include her sharp analysis and wit in the analysis of Mafia III. Credit to Frans Bouma for the game’s custom-made game photography tool.

Endnotes

[1] Pierre Nora has also previously used the term ‘prosthetic memory’ within the discipline of memory studies. For a comparative analysis between Nora’s use of prosthesis and Landsberg’s concept, cf. (Dickinson, Blair, and Ott 2010, p. 11f).

[2] Methodologically, an assessment of the memory-making of games either “focuses on actual practices of play or that analyzes the formal properties through which such practices are limited and predisposed” (Pötzsch & Šisler, 2019, p. 6) I employ both approaches in my analysis of Mafia III.

[3] “There were some early discussions about whether this choice would narrow the game's audience, said Strauss Zelnick, chief executive at Take-Two Interactive. But that quickly turned into a discussion of how to authentically depict the time period without being exploitative or preachy, he said”. (Tsukayama, 2016).

[4] Hangar 13 went for a mixed-race protagonist to emphasize the so-called one-drop rule: Regardless of the degree of black skin tone, Lincoln Clay is still targeted by US white supremacy (Conditt, 2016). As the character Father James points out in a cutscene in the game: "Not that it mattered -- back then if you look black, you black. Same as today, I suppose." Yet this decision might also be read as a form of colorism that only allows lighter-skinned representation rather than dark-skinned ones. (Hunter, 2007)

[5] The PR strategy of limiting the perception of Mafia III as an anti-racist and explicitly political game is indicated in various interviews up to the game’s release, where multiple employees of Hangar 13 repeat the refrain that ‘the game is not about racism’ and that they do not want to be ‘preachy’ or ‘stand on a soapbox’. This is presumably repeated to avoid public controversy that would limit potential sales.

[6] Similar dynamics can be seen in Assassin’s Creed: Liberation (Ubisoft Sofia, 2014) that stars a black female player-character in 18th century New Orleans. Cf. Soraya Murray’s analysis (2017) of the game’s intersecting dynamics between class, race, and gender.

[7] For example, based on her game Dys4ia (anthropy, 2012), a game dealing with gender transition, anna anthrophy argues that when a heteronormative cis-identity plays Dys4ia, it does not necessarily follow that the player knows what it means to transition from one gender to another. In response, anthropy created the Road to Empathy (2015) to criticize the illusion that when playing “a 10-minute game about being a transwoman, don't pat yourself on the back for feeling like you understand a marginalized experience." (D’Anastasio, 2015). In fact, empathy via media has been and still appears to be a marketing point to advertise the next, new media product that technology industries try to sell, as seen with the contemporary virtual reality headsets and their creators’ insistence on these machines’ capability to create even more empathy (Kastrenakes, 2017). As Wendy HK Chun (2016) observes, every day the news displays images of societal injustices, refugees, and war, yet people are not driven to action. The point being that mass media does not necessarily lead to actual political action. Instead, as Robert Yang notes on his blog on empathy via virtual reality, “I don't want your empathy, I want justice!” (Yang, 2017)

References

Aarseth, E., & Calleja, G. (2015). The Word Game: The Ontology of An Undefinable Object. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games, 1-8. Retrieved from http://www.fdg2015.org/papers/fdg2015_paper_51.pdf

Andersen, C. (2015). “There Has To Be More To It”: Diegetic Violence and the Uncertainty of President Kennedy’s Death. Game Studies, 15(2). Retrieved from http://gamestudies.org/1502/articles/andersen

Anthropy, anna. (2015). The Road to Empathy. Retrieved from https://www.arthaps.com/show/anna-anthropy-presents-the-road-to-empathy-1

Arnold-de Simine, S. (2013). Mediating memory in the museum: Trauma, empathy, nostalgia. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Berger, J. (2007). Which prosthetic? Mass media, narrative, empathy, and progressive politics. Rethinking History, 11(4), 597-612. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642520701652152

Blackmon, S. (2017). “Be Real Black For Me”: Lincoln Clay and Luke Cage as the Heroes We Need. CEA Critic, 79(1), 97-109. https://doi.org/10.1353/cea.2017.0006

Brightman, J. (2016, December 5). Mafia III has “allowed me as a white developer to make connections with people of color.” Retrieved October 2, 2017, from GamesIndustry.biz website: http://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2016-12-05-mafia-iii-has-allowed-me-as-a-white-developer-to-make-connections-with-people-of-color

Bustillos, M. (2013, March 19). On Video Games and Storytelling: An Interview with Tom Bissell. The New Yorker. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/on-video-games-and-storytelling-an-interview-with-tom-bissell

Chapman, A. (2012). Privileging Form Over Content: Analysing Historical Videogames. Journal of Digital Humanities, 1(2), 42-46.

----. (2016). It’s Hard to Play in the Trenches: World War I, Collective Memory and Videogames. Game Studies, 16(2). Retrieved from http://gamestudies.org/1602/articles/chapman

Chun, W. H. K. (2016, October). Keynote. Presented at the Weird Reality, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA.

Cole, Y. (2018, March 19). White Supremacy, Black Liberation, and the Power Dynamics of Gun Violence. Retrieved April 11, 2018, from Waypoint website: https://waypoint.vice.com/en_us/article/kzxevx/white-supremacy-black-liberation-and-the-power-dynamics-of-gun-violence

Conditt, J. (2016, October 8). The historical research behind the biracial antihero in “Mafia III.” Retrieved October 3, 2017, from Engadget website: https://www.engadget.com/2016/08/10/mafia-iii-race-historical-accuracy-interview/

Connell, R. W., & Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept. Gender & Society, 19(6), 829-859. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243205278639

Cooke, L., & Hubbell, G. S. (2015). Working Out Memory with a Medal of Honor Complex. Game Studies, 15(2). Retrieved from http://gamestudies.org/1502/articles/cookehubbell

D’Anastasio, C. (2015, May 15). Why Video Games Can’t Teach You Empathy. Retrieved February 7, 2017, from Motherboard website: https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/empathy-games-dont-exist

de Smale, S. (2019). Ludic Memory Networks: Following Translations and Circulations of War Memory in Digital Popular Culture (PhD Thesis). University Utrecht.

de Wildt, L., Apperley, T. H., Clemens, J., Fordyce, R., & Mukherjee, S. (2019). (Re-)Orienting the Video Game Avatar. Games and Culture, 1555412019858890. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412019858890

de Wildt, L., & Aupers, S. (2019). Playing the Other: Role-playing religion in videogames. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 22(5-6), 867-884. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549418790454

DePass, T. (2016, November 6). Ride or Die: Mafia III Review. Retrieved February 7, 2017, from The Ontological Geek website: http://ontologicalgeek.com/ride-or-die-mafia-iii-review/

Dickey, M. D. (2015). Aesthetics and Design for Game-based Learning. New York: Routledge.

Dickinson, G., Blair, C., & Ott, B. L. (2010). Places of Public Memory: The Rhetoric of Museums and Memorials. University of Alabama Press.

Dyer-Witheford, N., & Sharman, Z. (2005). The Political Economy of Canada’s Video and Computer Game Industry. Canadian Journal of Communication, 30(2). Retrieved from http://www.cjc-online.ca/index.php/journal/article/view/1575

Erll, A. (2011). Memory in Culture. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Ford, D. (2016). “eXplore, eXpand, eXploit, eXterminate”: Affective Writing of Postcolonial History and Education in Civilization V. Game Studies, 16(2). Retrieved from http://gamestudies.org/1602/articles/ford

Fordyce, R., Neale, T., & Apperley, T. H (2016). Modelling Systemic Racism: Mobilising the Dynamics of Race and Games in Everyday Racism. The Fibreculture Journal, (27: Networked War/Conflict). https://doi.org/10.15307/fcj.27.199.2016

---- (2018). Avatars: Addressing Racism and Racialised Address. In Woke Gaming: Digital Challenges to Oppression and Social Injustice (pp. 231-251). Retrieved from https://research.monash.edu/en/publications/avatars-addressing-racism-and-racialised-address

Fron, J., Fullerton, T., Morie, J. F., & Pearce, C. (2007). The Hegemony of Play. Situated Play. Presented at the DiGRA, Tokyo. Retrieved from http://ict.usc.edu/pubs/The%20Hegemony%20of%20Play.pdf

Fuchs, C. (2017). Capitalism, Patriarchy, Slavery, and Racism in the Age of Digital Capitalism and Digital Labour. Critical Sociology, 0896920517691108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920517691108

Gould, D. (2010). On affect and protest. In J. Staiger, A. Cvetkovich, & A. Reynolds (Eds.), Political Emotions (1 edition, pp. 18-44). New York: Routledge.

Gray, K. L. (2014). Race, Gender, and Deviance in Xbox Live: Theoretical Perspectives from the Virtual Margins. Waltham / Oxford: Elsevier.

---- (2017, February). The Digital Story That Games Tell--Buffoons, Goons, and Pixelated Minstrels. Presented at the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities. Retrieved from https://umd.hosted.panopto.com/Panopto/Pages/Viewer.aspx?id=4184a8f9-58fd-42a2-ae51-0be352dfae32

Gwaltney, J. (2016, October 22). The Virtual Life - Mafia III Is A Necessary Game. Retrieved October 2, 2017, from Game Informer website: http://www.gameinformer.com/b/features/archive/2016/10/19/the-virtual-life-mafia-iii-is-a-necessary-game.aspx

Hamilton, K. (2013, January 30). Splinter Cell: Blacklist Won’t Have Interactive Torture, But It’ll Still Have “Interrogations.” Retrieved January 22, 2018, from Kotaku website: https://kotaku.com/5980350/splinter-cell-blacklist-wont-have-interactive-torture-but-itll-still-have-interrogations

Hammar, E. L. (2017). Counter-hegemonic commemorative play: Marginalized pasts and the politics of memory in the digital game Assassin’s Creed: Freedom Cry. Rethinking History, 21(3), 372-395. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642529.2016.1256622

---- (2019). Producing Play under Mnemonic Hegemony: The Political Economy of Memory Production in the Videogames Industry. Digital Culture & Society, 5(1), 61-83.

----, & Woodcock, J. (2019). The Political Economy of Wargames: The Production of History and Memory in Military Video Games. In H. Pötzsch & P. Hammond (Eds.), War Games--Memory, Militarism and the Subject of Play (pp. 72-99). Bloomsbury Academic.

Harrell, D. F. (2013). Phantasmal Media: An Approach to Imagination, Computation, and Expression. MIT Press.

Hartmann, T. (2017). The “Moral Disengagement in Violent Videogames” Model. Game Studies, 17(2). Retrieved from http://gamestudies.org/1702/articles/hartmann

Hirsch, M. (2012). The generation of postmemory: Writing and visual culture after the Holocaust. Columbia University Press.

hooks, bell. (1992). Black Looks: Race and Representation. Boston: South End Press.

Hunter, M. (2007). The persistent problem of colorism: Skin tone, status, and inequality. Sociology Compass, 1(1), 237-254.

Kastrenakes, J. (2017, October 9). A cartoon Mark Zuckerberg toured hurricane-struck Puerto Rico in virtual reality. Retrieved January 31, 2018, from The Verge website: https://www.theverge.com/2017/10/9/16450346/zuckerberg-facebook-spaces-puerto-rico-virtual-reality-hurricane

Kerr, A. (2017). Global Games: Production, Circulation and Policy in the Networked Era. New York / London: Routledge.

Koss, J. (2006). On the limits of empathy. The Art Bulletin, 88(1), 139-157.

Landsberg, A. (2004). Prosthetic Memory: The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture. New York: Columbia University Press.

---- (2007). Response. Rethinking History, 11(4), 627-629. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642520701652194

---- (2015). Engaging the Past: Mass Culture and the Production of Historical Knowledge. New York: Columbia University Press.

Leonard, D. (2004). High tech blackface: Race, sports, video games and becoming the other. Intelligent Agent, 4(4.2). Retrieved from http://www.intelligentagent.com/archive/Vol4_No4_gaming_leonard.htm>.

---- (2016). Grand Theft Auto V: Post-Racial Fantasies and Ferguson Realities. In S. U. Noble & B. M. Tynes (Eds.), The Intersectional Internet--Race, Sex, Class, and Culture Online (pp. 128-139). New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

---- (2020). Virtual Anti-racism: Pleasure, Catharsis, and Hope in Mafia III and Watch Dogs 2. Humanity & Society, 44(1), 111-130. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160597619835863

Martin, G. (2016, December 12). The Purity of Revenge: Mafia III’s Writer on Racism, History and Vengeance. Retrieved May 14, 2017, from Pastemagazine.com website: https://www.pastemagazine.com/articles/2016/12/mafia-iii-william-harms.html

Maxwell, R., Raundalen, J., & Vestberg, N. L. (2014). Media and the ecological crisis. New York / London: Routledge.

Mir, R., & Owens, T. (2013). Modeling Indigenous Peoples: Unpacking Ideology in Sid Meier’s Colonization. In M. Kapell & A. B. R. Elliott (Eds.), Playing with the Past: Digital Games and the Simulation of History (pp. 91-106). New York / London: Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Moosa, T. (2016, October 20). Mafia III is just a game, but it shines a spotlight on the reality of racism. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/oct/20/mafia-iii-videogame-racism

Mosco, V. (2009). The Political Economy of Communication (Second edition). London: Sage.

Mukherjee, S. (2017). Videogames and Postcolonialism: Empire Plays Back. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

---- (2018). Playing Subaltern: Video Games and Postcolonialism. Games and Culture, 13(5), 504-520. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412015627258

Murray, S. (2017). The Poetics of Form and the Politics of Identity in Assassin’s Creed III: Liberation. Kinephanos - Journal of Media Studies and Popular Culture, (Special Issue), 77-102.

Nakamura, L. (1995). Race in/for cyberspace: Identity tourism and racial passing on the Internet. Works and Days, 25(26), 13.

---- (2017). Afterword: Racism, Sexism, and Gaming’s Cruel Optimism. In J. Malkowski & T. M. Russworm (Eds.), Gaming Representation: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in Video Games. Indiana University Press.

Nieborg, D. (2011). Triple-A: The Political Economy of the Blockbuster Video Game (PhD Thesis, University of Amsterdam). Retrieved from http://dare.uva.nl/search?arno.record.id=383251

Parkin, S. (2015, November 19). Tomb Raider and the clash between story and violence in games. Retrieved January 22, 2018, from https://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/259613/Tomb_Raider_and_the_clash_between_story_and_violence_in_games.php

Penabella, M. (2016, November 27). On the Margins of History. Haywire Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.haywiremag.com/columns/opened-world-on-the-margins-of-history/

Pötzsch, H. (2013). Ubiquitous Absence. Nordicom Review, 34(1), 125-144.

---- (2017). Selective Realism: Filtering Experiences of War and Violence in First- and Third-Person Shooters. Games and Culture, 12(2), 156-178. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412015587802

----, & Hammond, P. (Eds.). (2019). War Games--Memory, Militarism and the Subject of Play. Bloomsbury Academic.

----, & Šisler, V. (2019). Playing Cultural Memory: Framing History in Call of Duty: Black Ops and Czechoslovakia 38-89: Assassination. Games and Culture, 14(1), 3-25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412016638603

Qiu, J. L. (2017). Goodbye iSlave: A Manifesto for Digital Abolition. Champaigne, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Reading, A. (2014). Seeing red: A political economy of digital memory. Media, Culture & Society, 36(6), 748-760. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443714532980

---- (2016). Gender and Memory in the Globital Age (Reprint edition). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rigney, A. (2016). Cultural memory studies--Mediation, narrative, and the aesthetic. In A. L. Tota & T. Hagen (Eds.), Routledge International Handbook of Memory Studies (pp. 65-76). New York: Routledge.

Robertson, A. (2013, March 28). Death is dead: How modern video game designers killed danger. Retrieved January 22, 2018, from The Verge website: https://www.theverge.com/2013/3/28/4157502/death-is-dead-how-modern-video-game-designers-killed-danger

Roots [Biography, Drama, History, War]. (1977). David L. Wolper Productions, Warner Bros. Television.

Russworm, T. M. (2016). Blackness Is Burning: Civil Rights, Popular Culture, and the Problem of Recognition. Wayne State University Press.

---- (2017). Dystopian Blackness and the Limits of Racial Empathy in The Walking Dead and The Last of Us. In J. Malkowski & T. M. Russworm (Eds.), Gaming Representation: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in Video Games (pp. 109-128). Indiana University Press.

Salazar-Moreno, Q. (2016, September 29). You can shoot up a Ku Klux Klan rally in Mafia III. Retrieved January 30, 2018, from https://www.gamecrate.com/you-can-shoot-ku-klux-klan-rally-mafia-iii/14664

Shareef Jackson. (2016). #GLG25: Diversity in #Mafia3 pt1: Prologue #GamingLooksGood. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DjYy2KarlrA

Shaw, A. (2015a). Gaming at the Edge: Sexuality and Gender at the Margins of Gamer Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

---- (2015b). The Tyranny of Realism: Historical accuracy and politics of representation in Assassin’s Creed III. Loading..., 9(14). Retrieved from http://journals.sfu.ca/loading/index.php/loading/article/view/157

Singleton, J. (1997). Rosewood [Action, Drama, History]. Warner Bros., Peters Entertainment, New Deal Productions.

Smethurst, T., & Craps, S. (2014). Playing with Trauma Interreactivity, Empathy, and Complicity in The Walking Dead Video Game. Games and Culture, 1555412014559306.

Sobchack, V. (1992). The Address of the Eye: A Phenomenology of Film Experience. Princeton University Press.

Sontag, S. (2004). Regarding the Pain of Others (New Ed edition). London New York Victoria: Penguin.

SpawnOnMe. (2016, November 6). Spawn On Me MAFIA 3 Special, Part 1: The Panel of All Panels. Retrieved from http://spawnon.me/spawn-mafia-3-special-part-1-panel-panels/ or http://esn.fm/spawnonme/s2

Srauy, S. (2019). Professional Norms and Race in the North American Video Game Industry. Games and Culture, 14(5), 478-497. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412017708936

Sterczewski, P. (2016). This Uprising of Mine: Game Conventions, Cultural Memory and Civilian Experience of War in Polish Games. Game Studies, 16(2). Retrieved from http://gamestudies.org/1602/articles/sterczewski

Tsukayama, H. (2016, November 2). ‘Mafia III’ took a risk by choosing a black protagonist, and it has really paid off. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-switch/wp/2016/11/02/mafia-iii-took-a-risk-by-choosing-a-black-protagonist-but-its-really-paid-off/

Tybjerg, C. (2016). Refusing the Reality Pill: A Film Studies Perspective on Prosthetic Memory. Kosmorama. Retrieved from https://www.kosmorama.org/en/kosmorama/artikler/refusing-reality-pill-film-studies-perspective-prosthetic-memory

Uricchio, W. (2005). Simulation, history, and computer games. In J. Raessens & J. Goldstein (Eds.), Handbook of Computer Game Studies (pp. 327-338). Cambridge, Mass.; London: MIT Press.

Wawro, A. (2017, February 28). Writing Mafia 3: “We had a lot of very uncomfortable conversations.” Retrieved April 19, 2018, from https://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/292663/Writing_Mafia_3_We_had_a_lot_of_very_uncomfortable_conversations.php

Wiggins, T. (2016, October 17). Mafia III: Catharsis Through Extreme Violence. Paste Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.pastemagazine.com/articles/2016/10/mafia-iii-catharsis-through-extreme-violence.html

Wilde, P., & Evans, A. (2019). Empathy at play: Embodying posthuman subjectivities in gaming. Convergence, 25(5-6), 791-806. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517709987

Williams, D., Martins, N., Consalvo, M., & Ivory, J. D. (2009). The virtual census: Representations of gender, race and age in video games. New Media & Society, 11(5), 815-834. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444809105354

Wright, E. (2018). On the promotional context of historical video games. Rethinking History, 22(4), 598-608. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642529.2018.1507910

Yang, R. (2017, June 23). “If you walk in someone else’s shoes, then you’ve taken their shoes”: Empathy machines as appropriation machines. Retrieved May 9, 2018, from https://www.blog.radiator.debacle.us/2017/04/if-you-walk-in-someone-elses-shoes-then.html