Death Road to Capitalism: Business Ontology of the Zombie Apocalypse in Death Road to Canada

by Caighlan SmithAbstract

This article explores the contradictory nature of the zombie in video games as a symbol of both living and dead labor under neoliberal capitalism. This argument is advanced through a close Marxist reading of the business ontology behind the procedural rhetoric of Death Road to Canada (Rocketcat Games & Madgarden, 2016). Death Road operates as both zombie apocalypse game and life management simulator, in which the player less manages “life” and more manages “business” in the apocalypse. To succeed in Death Road, players are required to engage areas of business management, including time management, asset management, team management and morale management. I argue that in parodying the zombie apocalypse game genre through gameplay processes which also evoke the life/business management sim, Death Road reveals the business management inherent to the gameplay of zombie apocalypse games, if not zombie media more broadly. Specifically, I explore how the zombie, as engaged through business ontology, allows for simultaneously anti- and pro-capitalist gameplay. Such zombie play, however ostensibly liberatory it may be on certain levels, ultimately negotiates liberatory post-apocalyptic play through a very capitalist-sustaining cruel optimism. The zombie game’s optimism is cruel in that it requires a maintenance of the very neoliberal fantasies and consumer culture that distract from, if not excuse, capitalism’s exploitative labor conditions and the premature death it inflicts on many. As pleasurable and critically enlightening as it may be to play with the zombie’s end of the world, the zombie does not play with the end of capitalism; rather, the zombie reanimates it and the player in its image.

Keywords: zombie apocalypse games, business ontology, neoliberal capitalism, cruel optimism, premature death, consumer culture, life management simulator, parodic gameplay

Introduction

The zombie is a fundamentally contradictory figure. At its most basic level, it signifies as both living and dead yet cannot be comfortably placed in either category. This base contradiction of the zombie imbues it with symbolic affordances, where the zombie is never just representing the crossed boundary of life and death. Rather, zombies always signify other ideologically constructed boundaries that hold dominance in society at the time, as well as the marginalizing social dualisms that such boundaries can create (Bishop, 2009; Dendle, 2007; Kee, 2017). The zombie’s ability to represent and contradict ideologically constructed social boundaries is critically valuable, in that it illustrates Bailes’ observation that, “the first step to any social change is recognizing how certain assumptions underpinning our behavioral and ideological norms are contradictory or counterproductive” (2019, p. 1). Yet, as Bailes highlights, exposing the contradictions of the status quo is only the initial phase in sustainable social change.

In this article, I unpack how the zombie apocalypse video game offers a first step towards specifically neoliberal capitalist critique yet forecloses further steps away from capitalism. In taking this stance, I argue that there is capitalist complicity embedded in playful engagements with the zombie. I explore how contemporary zombie games, as capitalist leisure activity, are inextricably linked to performances of Fisher’s “business ontology,” which, under capitalism, naturalizes the belief “that everything in society, including healthcare and education, should be run as a business” (2009, p. 17). I review how zombie games -- as designed under capitalism -- are always also life management sims, and that life management sims -- as designed under capitalism -- are always also business management sims. I make this argument through a close reading of the business ontology in Rocketcat Games and Madgarden’s Death Road to Canada (2016).

Death Road is a 2D zombie apocalypse game billed as a “Randomly Generated Road Trip Simulator” in which players “control and manage a car full of jerks as they explore cities, recruit weird people, argue with each other, and face gigantic swarms of slow zombies” (Rocketcat Games and Madgarden, 2016). Death Road operates as both a zombie game and a life sim management game, as players juggle fighting zombies, resource acquisition and the physical and mental health of their group of survivors. As indicated by its description, Death Road is parodic in nature and, as Hutcheon suggests, parody is an artistic approach which provides “repetition with critical distance” of tropes, genres and archetypes (1985, p. 6). In parodying the zombie apocalypse genre through an amalgamation of zombie game and life sim mechanics, Death Road critically distances itself from standard zombie game affects, such as that of horror or thrill (Schmeink, 2016). By designing this critical distance through the life sim, Death Road reveals the business ontology that haunts the zombie genre’s procedural rhetoric across gaming, if not across zombie media itself.

Through a review of Death Road’s business ontology as well as the contradictory zombie as both dead labor (representing capitalist expansion) and living labor (representing the premature death of the capitalist laboring class), my aim in this article is to show how zombie games let players fight against but simultaneously fight for capitalism. I contend that such undead gameplay provides a cruelly optimistic outlet for capitalist driven woes and anxieties, which leaves the player’s complicity with capitalism itself intact. Berlant defines cruel optimism as the “relation of attachment to compromised conditions of possibility whose realization is discovered either to be impossible, sheer fantasy, or too possible, and toxic” (2011, p. 24). Zombie games steer their players not towards optimistic alternatives to capitalism, but towards cruelly optimistic acceptance of the capitalist status quo.

To advance such an argument, I first position my analysis in the context of critical ideology theory as it relates to capitalism, living and dead labor and neoliberal business ontology. Following this, I explore previous scholarship on zombie games to address how the zombie is repeatedly entangled with the ideological tensions of social exploitation under neoliberal capitalism. I then provide my close reading of Death Road’s business ontology, with a focus on four business management categories embedded in the game’s procedural rhetoric: time management, asset management, team management and morale management. The remainder of my article discusses how Death Road’s parodic nature and engagement of neoliberal fantasies reveals the capitalist nature of zombie games more broadly.

Undead Capital

Before approaching my close reading of Death Road, I must frame how I am reading the zombie as a figure of capitalist contradictions. The zombie, despite its contradictory nature, nonetheless operates to maintain capitalist dominance. This requires a contextualization of capitalist ideology itself. Capitalism may be understood as:

an economic system in which: the material conditions of life are to be obtained nearly exclusively via the free market; wage labor is a defining characteristic; private ownership of the means of production is promoted; and the system as a whole is driven by certain systemic imperatives, by competition and surplus accumulation. (Tyner, 2019, p. 39)

Yet capitalism has expanded into much more than simply an economic philosophy (Fisher, 2009), and it is here that its nature as ideology comes into play. Bailes defines ideology “not only as a social background of assumptions and pressures, but also [the] different ways in which people justify behaving in accordance with that background” (2019, p. 19). Understanding capitalism through an ideological lens is essential because capitalism “makes demands upon us” to act a certain way, and because of its ability to function as ideology, capitalism’s demands “do not simply programme us to fulfil specific social roles but encourage us to make choices and take responsibility for them” (Bailes, p. 19). In other words, the choices people are incited to make under capitalist ideology can register as “common-sense” rather than capitalism-constructed modes of being in the world. But why is it essential to question the common sense of capitalism?

As previously indicated, capitalism functions on exploitative social hierarchies, which allows those who control the flow of capital to likewise control the livelihoods of those who do not control that flow, but whose living labor is required to generate profit (Tyner, 2019). Despite such exploitation, capitalism justifies itself as the best of any possible social structure through such alleged phenomena as the “trickle-down” effect, in which capitalist-guided societal advancement benefits every class, even if some classes benefit more than others. Yet in practice the benefits of this “trickle-down” are near impossible to measure or adequately evaluate. Trickle-down economic systems take no accountability for the continuously expanding gap between the rich and the poor created under capitalism (Wilson, 2017). This phenomenon also does not account for capitalism’s ongoing marginalization of various peoples, including women, people of color, queer people, trans people and the elderly, whose labor and identities are continuously undervalued and devalued by capitalist social hierarchy (Brown, 2019; Leeb, 2018; Tyner, 2019).

Rather than acknowledge the violence and discrimination of its exploitative operations, capitalist common-sense contends that anyone can “make it on their own -- through their own hard work and initiative” (Wilson, 2017, p. 101). As Bailes highlights, “[c]apital moves to take advantage of lucrative opportunities” -- such as the financial exploitation of already marginalized peoples -- and capitalist subjects prescribed to capitalism’s common-sense, “are supposed to be endlessly flexible and continually reinventing ourselves to keep up” (2019, p. 13). Such an observation recalls the metaphor of the “race,” well-known and often circulated among capitalist subjects, to refer to capitalism’s demands that laborers metaphorically race towards a more lucrative capitalist position. Such a race notably involves competing against each other to win, but also competing so as not to “fall behind” and suffer the extremes of capitalist exploitation (Wilson, 2017).

Zombie games not only figuratively but literally involve various types of “races”: the race of the survivors away from pursuing zombies, and the race of the zombies in their pursuit of survivors. Here, I return to the contradiction of the zombie: in this race, are zombies the power of capital, hounding the laborer-survivor to keep racing? Or are zombies those already consumed, those who could not “reinvent” themselves adequately to “keep up,” and who hound the laborer-survivors? This “race” serves as a reminder of the premature death the working class may face if they fall behind in -- or dare to opt out of -- the capitalist race.

Earlier, I claimed the zombie symbolized both dead and living labor, but before explaining this symbolic function and its interactions with business ontology, I must first discuss how capital negotiates living and dead labor. A Marxist reading of capitalism holds that “dead labor constitutes past labor power, the expended energy that is embodied within a thing,” such as a commodity, where “‘dead labor’ serves as a metaphor, in opposition to the living laborer who expends his or her own energy reanimating the dead labor to serve a useful purpose” (Tyner, 2019, pp. 17-18). This reanimation comes at the expense of the laborer, whose living labor is exploited by the capitalist to create surplus value, which benefits the capitalist by draining the laborer. As Marx observes, “[c]apital is dead labour, that, vampire-like, only lives by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks” (1887, p. 163). While Marx here uses the metaphor of the vampire, both the vampire and zombie share a cannibalistic desire to consume the life force of their laborer-victim -- be it blood, body and/or brains -- for the sake of increasing their own vitality.

The insatiability of capital produces work relations which risk metaphorical if not literal “premature death” for the laborer (Tyner, 2019). Through a Marxist lens, Tyner identifies that one’s “social relations and one’s position to the generation and distribution of surplus inform one’s vulnerability to premature death” (p. 19), highlighting how capitalism safeguards its winners, while rendering its losers vulnerable not only to social oppression and marginalization, but also to an early death. Such premature death can and has stemmed from overworking, underpayment, malnourishment, lack of proper healthcare and unsafe working conditions, among other exploitative capitalist factors (Tyner, 2019). Yet laborers can also experience a figurative premature death. Consider Leeb’s observation that “encounters in capitalism are structured in such a way that they deplete a large part of society of its bodily and mental powers, whereas they augment the powers of a small minority” (2018, p. 266). Here, to provide profit for the few, many labors are so “depleted” by a draining of the mind, body and spirit, that while they may still be physically alive -- and, often, able to work and lead long lives in capitalist society -- they have no energy left over to improve their circumstances within that society, let alone to rally against capitalist exploitation.

Capitalism’s draining social order is both sustained and exacerbated by neoliberal rationality. Neoliberalism, or neoliberal capitalism, may be understood as the current dominating iteration of capitalism. While it finds its roots in economic principles intended to facilitate the growth of the capitalist market, neoliberalism’s ideological relevance has expanded far beyond economics (Harvey, 2005). Following Foucault, Brown describes neoliberalism as a “novel political rationality” in which “market principles become […] saturating reality principles governing every sphere of existence” and converting people into subjects “of competition and human capital enhancement” (2019, pp. 19-20). Under neoliberal rationality, capitalist common-sense has come to include an “entrepreneurialization” or “responsibilization” of the subject as human capital (Brown, p. 38), in which the subject must constantly compete not just against other subjects but against prior versions of themselves to always enhance the self-as-capital.

Neoliberal rationality’s injunction to compete rises from its entrepreneurial individualization of the capitalist subject, in which: the subject is individually responsible for both their successes and their failures (rather than the capitalist socioeconomic order and its systemic barriers); individuality and the familial are venerated over community and the social; and individuality is celebrated by and through participation in consumer culture (Bailes, 2019; Brown, 2019; Wilson, 2017). I have concluded this section by introducing the term “neoliberalism” to highlight a specific capitalist-serving rationality that holds ongoing ideological dominance. Neoliberal rationality grounds the contemporary business ontology that sustains marginalizing capitalist social boundaries, both in the world more broadly and in the games played with zombies.

Zombie Play

Zombie games scholarship has already highlighted how the genre can simultaneously empower and disempower identities marginalized under capitalism. The hallmark zombie game series Resident Evil offers many examples. Resident Evil 4 (Capcom Production Studio 4, 2005) symbolically employs the zombie as terrorist, which inevitably plays into the xenophobic marginalization of capitalism’s post-9/11 cultural terrain (Taylor, 2009, p. 57). Meanwhile, Resident Evil 5 (Capcom, 2009) perpetuates “Western hegemonic conceptions of femininity and race” (Brock, 2011, p. 443) through both Sheva, its African female lead, and its racialized depiction of zombies, evoking capitalist-colonial exploitation of both women and people of color. Elsewhere, Pokornowski discusses colonialism in the Resident Evil franchise and reveals how the national and colonial “history of empire cited by and embodied in the zombie figure can be obscured by a narrative focus on global health and security” (2013, p. 217). The zombie as antagonist to global health and security affords the player the justification to oppress the zombie. Such justifications are likewise put forth by capitalist ideology, empowering the holders of capital to oppress living labor in the name of global benefit (Wilson, 2017).

Putting forth a more optimistic reading of the zombie game’s boundary-breaking potential, Jennings (2018) argues that Resident Evil’s recurring woman of color lead, Ada Wong, is empowered through her zombie apocalypse narrative in Resident Evil 6 (Capcom, 2012) in such a way that counteracts sexist and racial stereotypes. Yet Wong achieves that empowerment in part through the neoliberal rational of individualization and domination over one’s competitors. While Wong’s empowerment as woman of color is still empowering to various marginalized communities, the fact that it happens through the zombie genre’s complicity in neoliberal business ontology leaves capitalist structures ideologically intact. If such structures are not exploiting Wong, they will exploit others instead. Someone’s premature death is still required to give the zombie its playable form and its subsequent potential to empower those who have not yet been disempowered/zombified.

Social exploitation is inherent to zombie apocalypse games beyond the Resident Evil franchise as well. Kee highlights how the use of “extra-ordinary” zombies/playable zombies in various games as contrasted by the ordinary, cannon fodder zombie can reinforce how “victimization is appropriate for some bodies and not others” (2017, 129). Elsewhere, Russworm exposes how both The Walking Dead (Telltale Games, 2012) and The Last of Us (Naughty Dog, 2013) perpetuate racial stereotypes in the “muted or thwarted hope and resistance and obligatory sacrifice” of black characters, thereby reproducing dystopias in which “the fate of black subjectivities remains as predictable as the narrative conventions of the next zombie apocalypse” (2017, p. 126). Meanwhile, Butt and Dunne reveal the gendered bias underlying narrative presentation in The Walking Dead: Season Two (Telltale Games, 2013-2014), in which players are given more incentive to villainize and sacrifice Jane -- a female character who defies gender expectations -- over Kenny, who fits the role of a patriarchal father figure (2019, pp. 437-438).

The aforementioned zombie games are read by scholars as critically engaging power dynamics around marginalized identities, particularly how those identities can be empowered and/or disempowered in the zombie apocalypse. Some of these identities are marginalized under patriarchy, white supremacy, colonialism or other oppressive ideologies, yet notably each of these identities is also vulnerable to marginalization under capitalism. My analysis of Death Road, as an exposure of the zombie game’s inherent business ontology, is intended to help draw capitalism to the fore of zombie game critique. Specifically, I add to zombie game scholarship by proposing that Death Road’s dual function as zombie game and life/business management sim highlights how contemporary zombie games as a genre empower/disempower players less as human survivors and more as human capital.

Death Road to Canada

To discuss how Death Road’s gameplay highlights the zombie game genre’s inherent business ontology, I follow Bogost in prioritizing analysis of the game’s procedural rhetoric. Bogost defines procedural rhetoric as “the practice of using processes persuasively” (2007, p. 28). Unpacking a game’s procedural rhetoric allows consideration of how its processes (such as its mechanics) produce certain persuasive arguments about the world and what they mean for players. Prior to unpacking Death Road’s procedural rhetoric, it is therefore essential to explain the game’s key processes.

In Death Road, a player’s main goal is to guide their survivors through a zombie-infested United States to reach the safety of Canada. Based on the selected game mode, the player is given a certain number of days until their survivors reach their Canadian destination. To beat the game, the player simply needs to have at least one character reach the end of the road, defeat a final horde of zombies and cross the Canadian border. Achieving this goal requires the player to alternate between making narrative choices based on randomly generated scenarios, such as how to handle bandits attempting to extort their survivors, and playing as their survivors to stockpile resources in randomly generated locations. Such locations include either hostile, zombie-invested areas which survivors can loot, or survivor camps in which the player can trade with non-player characters (NPCs) and sometimes recruit new survivors.

The primary resources required to reach Canada, as quantified in the game’s main menu, include food (the standard survivor requires two foods per one day of travel), medicine (to heal survivors that have lost health fighting zombies or in narrative incidents), gas (to keep the player’s car running) and bullets (for various guns). All these resources are necessary not only for their use-value, as described above, but also for their exchange-value at trading camps, in which each may be exchanged with NPCs for better equipment or for other necessary resources. Equipment in the game also includes weapons (such as guns, knives, baseball bats or even electric guitars and spatulas), throwables (such as molotovs or grenades), flashlights (necessary for scavenging at night or in dark areas), medical spray (which heals during combat rather than the medicine resource which heals while on the road) and special items such as robots or the “Pukeyball” (parodying Pokémon’s Pokéball).

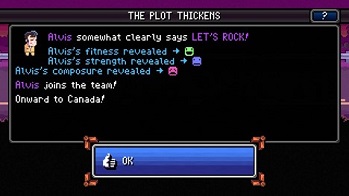

Alongside such equipment and the player’s quantified resources, the player’s third main asset category is the survivors themselves. The player can “manage” up to four survivors at a time, which may mean kicking a survivor out of their group if another, more promising survivor appears. Survivors may be custom-created by the player, randomly generated by the game or randomly encountered on the road as one of the “rare” pre-scripted characters (Figure 1). Rare characters all parody pop culture icons or trends (for example, Alvis, Anime Girl, Kaiju, L*nk), typically come with special abilities and often earn the player a metagame achievement if they reach Canada with that survivor still in their group (for example, the “Thankyaverymuch” achievement for winning with Alvis). Survivors, whether random, custom or rare, come with unique perks and stats, and sometimes also add equipment to the group inventory.

Figure 1. Screenshot from Death Road to Canada introducing pre-scripted rare character and Elvis parody “Alvis” (Rocketcat Games & Madgarden, 2016).

A successful game of Death Road therefore necessitates managing a variety of assets (including the lives of survivors) to reach the Canadian border. In the following section, I unpack how the above mechanics fold into capitalist business ontology through management processes that find their counterparts in business management. These processes include: 1. time management, 2. asset management, 3. team management and 4. morale management. In Death Road, success is not a matter of saving the weak and valuing all human life, but rather of saving people for what they can give the player and feeding excess survivors to zombies when the group needs to downsize. That is, Death Road’s gameplay highlights the zombie apocalypse’s business ontology, which puts forth premature death and the race to enhance (human) capital as inevitable conditions of doing business.

An Undead Business Ontology

1. Time Management

Death Road begins by informing players of how many days it will take their survivors to reach Canada, thus introducing the very first corporate management skill into gameplay: time management. All the player’s decisions, moving forward, must be based on the number of days until their deadline. For a new Death Road player, this initially means balancing assets such as food and gas to make sure they have enough to last x-number of days to Canada. However, the player will also need to stockpile sufficient weaponry, survivors (in terms of numbers and ability) and special items, to give them a better chance of surviving the three final hordes that greet each Death Road player at the end of their trip. These hordes increase in scale, time duration and difficulty, up until the player reaches the border. In other words, the experienced post-apocalyptic manager knows how to prepare for crunch time.

Time management in Death Road also requires the management of the day-to-day. Every day in Death Road must be used wisely, and this includes picking the best scavenging location from those with which the player is randomly presented, as the player only has time to scavenge in one location per day. Additionally, the player must manage their time within the scavenging location. Time passes quickly when scavenging, and when night falls zombies become more aggressive and begin actively swarming the survivors. The player is therefore incentivized to scavenge in a location as efficiently as possible, so as not to risk losing their survivors or valuable combat resources to the nocturnal zombie hordes. If a player finds themselves in a particularly well-stocked scavenge location, however, they may choose to work late and risk their survivors’ well-being. Such risks are often undertaken for the sake of an equally important area of management: the management of player assets.

2. Asset Management

As indicated above, competent asset management is necessary to a successful run at Death Road. Players must secure enough food and gas to get their team of survivors to Canada, while also acquiring enough weaponry and combat items to defeat the final hordes at the Canadian border. The savvy asset manager knows to prioritize food and gas in the early days of travel, so that their survivors will maintain morale and health, and so that the player may take on more survivors or trade in the camps for better supplies. This correlates to a typical business practice of covering one’s necessary base resources before investing in other resources which could either enhance or expedite profit.

A key aspect of asset management in Death Road is evaluating which of the randomly provided scavenging locations will yield the best assets. For example, if the player is short on food, they may have to prioritize a scavenging location with a grocery store, even if another scavenging location promises better weapons. If the player has their base assets covered, it may be worthwhile to take a chance on one of Death Road’s rare locations, such as the “Mystery Factory” or “Ominous Labs.” These locations could provide food, bullets or other useful resources, but they also promise valuable hidden loot. Such loot is often acquired by unlocking safes, which contain randomly generated items, such as ample food supplies, submachine guns, knight swords and so on. At other times, random encounters allow the player to choose from randomly generated loot -- perhaps by saving an NPC while scavenging, or picking the right narrative choice in a narrative prompt on the road. In each case, the logic of asset management is required in responding to these random loot offers. If the player wants to win a given Death Road run, they are incentivized to cover their base assets, stockpile assets for the final hordes and acquire whatever assets will streamline their advance to Canada.

3. Team Management

Death Road managers do not just manage the resources used by their team, they also build and manage the team itself. This management requires savvy hiring practices and employee skill development. At the beginning of the game, players can choose to start with one or two survivors -- either randomized characters or characters of their own making. As indicated, each character has certain perks, which give them a boost and/or penalty to Death Road’s list of pertinent skills. Although the player may be aware of a survivor’s potential strengths and weaknesses, they will not know the survivor’s level of ability in any given skill until that skill is put to the test (Figure 2). The player may give their survivor the “Mechanic” perk, or the player may accept into their group a survivor who claims to be good at fixing cars, but when the car breaks down and needs to be repaired, that survivor’s skill may be revealed as average, or even subpar. When the player puts survivors’ skills to the test, this mirrors the testing of newly hired employees, who claim certain competencies in an interview or on their resumes, but in practice fall short. The player can then decide, like the manager, to let that survivor go, to replace that survivor with a seemingly more competent survivor, or to train that survivor either in their deficient skills or focus on building their more promising skills.

Figure 2. Screenshot from Death Road to Canada illustrating a custom-made character’s tested and untested skills (Rocketcat Games & Madgarden, 2016).

In Death Road the player can only hire so many survivors. Since the game caps the group at four, the player must select survivors and their various skill combinations wisely if they wish to have a group capable of reaching Canada. Having a survivor competent in each skill is the player’s best chance at a successful journey. Beyond fixing the car (mechanical), zombies must be fought (strength or shooting), survivors cannot tire while fighting (fitness) or they will slow down and be bitten, in which case they must be healed (medical). If the group comes across bandits, the survivors need to calmly come up with a plan to deal with them (wits, attitude, composure). The survivors also need to be loyal, so that they do not betray the group to the bandits. As with any department that requires multiple skills, training each survivor to have diverse and complementary skill sets means the player can delegate certain tasks to whichever survivor has the suitable skills -- thereby maintaining team efficiency, harmony and morale.

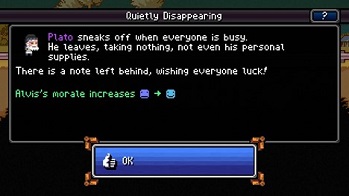

4. Morale Management

Keeping up survivor (or employee) morale is a major aspect of Death Road. Morale can be positively affected by having enough food for each survivor, finding safe locations for them to rest through the night, completing special random missions and choosing “morale boost” as a reward for the group, or random positive dialogue exchanges between survivors. On the other hand, morale drops when the survivors do not have enough food, cannot rest safely or at all, are hurt during combat, or have a random negative dialogue exchange with other survivors. Death Road’s morale mechanics, and the player’s management thereof, mirror how employees can suffer a morale boost or morale deficiency in the real world. Consider how employees are typically motivated to work when doing so allows them to: fulfill their basic needs, adequately rest and socially engage with people they like. Random events that result in “morale boost” rewards also mirror how team building exercises are intended to raise morale among coworkers. Employees lose morale when they do not get along with their team, when they are overworked, when they are in mentally and physically unsafe environments and/or when their basic needs are under threat.

In business management, it is necessary to keep up employee morale so that employees continue working efficiently and do not protest their working conditions or quit. Death Road reflects this too, in that if a survivor’s morale drops too low, they may abandon the group (Figure 3), sometimes stealing from the group before departing. Maintaining morale is therefore imperative to a successful post-apocalyptic journey. Unlike in real life, the game makes morale immediately quantifiable, representing each survivors’ current attitude through emoticons which change color and expression as survivors’ moods shift along the morale scale. If a survivor’s morale begins to run too low, and the player has no way of satisfying that survivor, it is altogether too easy to “layoff” the discontent of their team. That is, to drive off without them at the end of a scavenging mission or to lead them to their death in the middle of a zombie horde. Remediating competitive, capitalist logics, this tactic is beneficial in the game system, not only because it gets rid of a survivor that threatens the harmony of the group, but also because it (1) maintains limited resources (removing another mouth to feed) and (2) provides a distraction if the horde proves too overwhelming for the player. While the zombies are busy feasting on the player’s most disposable member, the player’s most valued survivors will have a chance to escape. It is also worth mentioning that a group member’s death does not bring down survivor morale, unlike running out of food. So long as the survivors (employees) are still being fed (paid) they can deal with losing a coworker.

Figure 3. Screenshot from Death Road to Canada featuring a custom-made character leaving the group (Rocketcat Games & Madgarden, 2016).

Discussion

Death Road necessitates the player’s mastery of managerial skills inherent to business ontology, which connects to the presence in contemporary zombie media of what Fisher calls “capitalist realism” (2009, p. 2). Fisher defines capitalist realism as “the widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to it” (p. 5). One would think that, if any environment were conducive to imagining a reality beyond capitalism, it would be a post-apocalyptic environment. Yet Death Road shows that the collapse of society is rather a vehicle through which to assure the survivability of neoliberal capitalist ideology and, by extension, the survival of neoliberal capitalist subjecthoods. As Berlant observes, such “subjects of productive and consumer capital, [are] willing to have our memories rezoned by the constant tinkering required to maintain the machinery and appearance of dependable life” (2011, p. 31). Death Road, in its explicit procedural operations as a life management sim, highlights how producing a “dependable life” out of zombie apocalypse play relies on capitalist business ontology. In zombie games, players enter into a cruelly optimistic contract with the zombie apocalypse. Such game systems incentivize pleasure from playing at managing the end of the world, rather than playing at ending capitalism’s management of the world and of ourselves.

What’s more, play at managing the end of the world is facilitated through the indulgence of neoliberal fantasies. Consider how Death Road’s business ontology is supported not only by win-conditions which prioritize consumption and accumulation, but also on the fantasy of infinite resources, which are out there somewhere to be acquired by the savvy manager of the post-apocalypse. Fisher notes that the fantasy of inexhaustible resources is essential to maintaining neoliberal capitalist dominance, as it obscures this ideology’s all-encompassing destruction of the natural environment for capital expansion. As Fisher articulates, such erasure of or diversion from “environmental catastrophe illustrates […] the fantasy structure on which capitalist realism depends: a presupposition that resources are infinite” (2009, p. 18). Death Road, like other zombie games, taps into this capitalist desire for infinite resources.

So long as the player has one survivor, there are infinite other survivors that may appear to join their group, due to the game’s procedural reliance on randomly generated events, characters and items. There is also the infinite potential for supplies. If the last trek into an abandoned town did not net enough food or gas, the player simply needs to keep their survivors alive until the next opportunity to loot. Until the player reaches Canada or until their last survivor dies, there is always the possibility to find and collect more items and people. The player’s personal supplies may run low or run out -- mimicking the precarity of survival for many neoliberal subjects -- but the gameworld of Death Road revitalizes this precarious subject’s commitment to neoliberal rationality through processes that promise infinitely more, if one just keeps working/playing.

The zombie game fulfills not only the neoliberal fantasy of infinite resources, but also the fantasy of rampant individualized consumption as it is linked to capitalist-sustaining consumer culture. Consider, for instance, Death Road’s parodic centering of the shopping center/mall, specifically through scavenging gameplay. One of Death Road’s most obvious shots at consumerism is taken through the in-game department store “Yall-Mart.” This obvious Walmart parody is equipped with a parking lot full of zombies, wrecked cars and abandoned shopping carts (which can be picked up and thrown at the zombies). Inside the department store, players might find food, bullets, medical supplies or guns. Players will almost certainly acquire at least one gas tank if they check the toilets in the public washroom. In terms of resource acquisition, Yall-Mart is a wise scavenging choice, which pushes the game’s simultaneous mocking of and reliance on consumerism to the fore: of course, one’s smartest post-apocalyptic plan is a shopping spree at Walmart.

Death Road’s use of the shopping center/mall plays on a longstanding deployment of such commercial venues in zombie media, and in zombie games in particular (Left 4 Dead 2, Valve, 2009; Dead Rising, Capcom Production Studio 1, 2006; The Last of Us: Left Behind, Naughty Dog, 2014). The mall as favored zombie apocalypse location was originally popularized through George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978). Responding to Romero’s work, Harper observes that the film transforms the mall “into a Dionysian orgy of violent indulgence [which] has a deep attraction for its American consumers” (2002, p. 5). Harper highlights Romero’s critical focus on the zombie apocalypse mall as symbolic of consumer culture’s social dominance (especially Americanized consumer culture). Romero’s film also plays on the contradictory nature of the zombie, in casting the zombies, who seek access to the mall and survivors within, as mindless consumers clamoring at the mall’s doors. Romero achieves this while also portraying the survivors trapped in the mall as giving into mindless consumption, rather than facing the pressures of the world (and zombies) outside. Although Romero’s critique of consumerist culture here is more sobering in tone, Death Road’s subversion of the shopping center puts forth the same consumerist message: the shopping center of the zombie apocalypse evokes the neoliberal fantasy of infinite and unbridled consumption.

Such consumption fantasies are pervasive to the zombie apocalypse genre. For example, one of the main appeals of the Dead Rising series is its wide array of -- often ridiculous -- methods for zombie disposal, from giant swordfish to lawnmowers to the player-made “drill bucket,” all of which contribute to the series’ simultaneous mocking and indulgence of consumerism and its general “sense of excess” (Hunt, 2015, pp. 116-117), while also emphasizing a very neoliberal individualizing of one’s custom weapons and preferred zombie-killing style. Dead Rising in this way critiques capitalist consumption through parody (Weise, 2009), while simultaneously allowing the player to indulge in capitalist consumptive fantasies.

Meanwhile, the “Dead Center” campaign of popular zombie shooter Left 4 Dead 2 (Valve, 2009) is situated around reaching and fighting through a mall. This campaign culminates in a final fight in the mall atrium, in which players shoot down waves of zombies before making off with a display sports car through the front doors of the mall in a cinematic, triumphant escape, glorifying the survivors’ apocalypse-necessitated consumption of a flashy getaway vehicle. Sports cars, in consumer culture, represent high-end consumers in both their cost and cultural significance. In Left 4 Dead 2’s use of the sports car, as well as in other zombie games, the player is yet again allowed to indulge in consumer culture as they also seemingly mock, subvert and destroy it.

This brings my argument back to the contradictory nature of the zombie and its apocalypse. If zombies are read as dead labor, as capital pursuing the rebellious survivors, then survivors are subverting capitalism’s reward system. In this framing, survivors bypass the demands of capital which seek to drain their living labor, and shoot or flee straight to what capitalism held up as the reward for said draining: an electric guitar, expensive jewelry, the flashy sports car. Meanwhile, if the zombies represent living labor, e.g., laborers in the process of being drained entirely by capital, then the survivors become those who are working to avoid the ranks of the lower class. The survivors, in this framing, do not challenge capitalism’s reward system but work to be rewarded by it. Survivors fight to prove themselves skilled and/or savvy enough in managing their apocalypse to be worthy of capitalist-consumer rewards; an electric guitar, expensive jewelry, the flashy sports car.

While the former reading appears anti-capitalist, and the latter appears to conform to the capitalist incentive for social mobility, both readings exist within the undead, contradictory body of the zombie. Its corpse -- and playful engagements with that corpse -- are both anti-capitalist and capitalist-conforming. The zombie game plays with capitalism, simultaneously turning away from and turning back to it, rather than eschewing capitalist social relations to holistically play with ideological alternatives. If this statement seems broad, consider again the above examples. Even as they contradict each other, with one allowing the anti-capitalist rebel to “stick it to the man” and the other allowing the staunch capitalist to pursue winning the capitalist game, both hinge on neoliberal fantasies of deregulated consumption.

Even if the player only wants to own a flashy sports car in their post-apocalyptic play to crash it through hordes of zombies, the player still seeks to consume the flashy sports car. Indeed -- much like Marx’s capital vampire/zombie, draining its victims to the point of premature death -- such subversive consumption still consumes the sports car for one’s own pleasure. The zombie game player is positioned to take advantage of such consumptive pleasure as supposedly liberated pioneer of the new post-apocalyptic landscape. As Dendle surmises, “[p]ost-apocalyptic zombie worlds are fantasies of liberation: the intrepid pioneers of a new world trek through the shattered remnants of the old, trudging through the shells of building and the husks of people” (2007, p. 54).

Death Road, like many other zombie games, presents the possibility of liberation through unpoliced, unrestricted consumption, as well as through the idea of infinite consumables existing somewhere in the gameworld to be uncovered by the effective player-manager. Such liberatory zombie play echoes Berlant’s cruel optimism, in which the fantasy of liberation is cruel in that it is just that, a “sheer fantasy” -- one built on an optimism generated by living labor that is not yet consigned to premature death.

Conclusion

In its direct engagement with business ontology’s management of time, assets, people (teams) and morale, this reading of Death Road explores how the zombie apocalypse game genre may appear chaotic, but is in fact efficiently ordered by neoliberal rationality. The chaos of the zombie game is more akin to the neoliberal fantasy of the unregulated free market, no longer restricted by the state. The zombie apocalypse’s business ontology and neoliberal fantasy highlights the contradictory nature of the zombie under capitalism. The zombie is a figure through which capitalist frustrations are excised, and capitalist complicity simultaneously entrained. While the zombie game genre provides opportunities in both its play and design for players to consider, unpack and interrogate the social contradictions of late capitalist society, it remains a genre that is saturated with capitalist values, rewards and fantasies.

In the 1980s, Jameson observed that “[i]t seems to be easier for us today to imagine the thoroughgoing deterioration of the earth and of nature than the breakdown of late capitalism” (1998, p. 50). He was later echoed by Fisher, who surmised, “[i]t’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism” (2009, p. 1). Fisher also added -- to the point of my focus on the zombified end of the world -- “[c]apital is an abstract parasite, an insatiable vampire and zombie maker; but the living flesh it converts into dead labor is ours, and the zombies it makes are us” (p. 15). Following these scholars, I hold that the end of the world in contemporary zombie games, and zombie media more broadly, does not likewise depict the end of capitalism. The specter of capitalism remains in post-apocalyptic zombie play, in which capitalism is exorcised, even as it continues to possess post-apocalyptic subjects. This is not to say zombies should be eschewed in game design and play entirely. However, the contradictory capitalist valiances of zombie media must be brought to attention. Perhaps other genres, and perhaps other monsters, may illuminate new forms of being, or new contradictions, which can move game design beyond the cruel optimism of capitalism.

References

Bailes, J. (2019). Ideology and the Virtual City: Videogames, Power Fantasies and Neoliberalism. Zero Books.

Berlant, L. (2011). Cruel Optimism. Duke University Press.

Bishop, K. (2009). Dead Man Still Walking: Explaining the Zombie Renaissance. The Journal of Popular Film and Television, 37(1), 16-25.

Bogost, I. (2007). Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. The MIT Press.

Brock, A. (2011). “‘When Keeping it Real Goes Wrong’”: Resident Evil 5, Racial Representation, and Gamers. Games and Culture, 6(5), 429-452. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412011402676

Brown, W. (2019). In the Ruins of Neoliberalism: The Rise of Antidemocratic Politics in the West. Columbia University Press.

Butt, M.R. & Dunne, D. (2019). Rebel Girls and Consequence in Life Is Strange and The Walking Dead. Games and Culture, 14(4), 430-449. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412017744695

Cameron, A. (2021). Zombie Media: Transmission, Reproduction, and the Digital Dead. Cinema Journal, 52(1), 66-89.

Capcom. (2009). Resident Evil 5. [Sony PlayStation 3]. Digital game directed by Y. Anpo & K. Ueda, published by Capcom.

Capcom. (2012). Resident Evil 6. [Sony PlayStation 3]. Digital game directed by E. Sasaki, published by Capcom.

Capcom Production Studio 1. (2006). Dead Rising. [Microsoft Xbox 360]. Digital game directed by Y. Kawano, published by Capcom.

Capcom Production Studio 4. (2005). Resident Evil 4. [Nintendo GameCube]. Digital game directed by S. Mikami, published by Capcom.

Dendle, P. (2007). The Zombie as Barometer of Cultural Anxiety. In N. Scott (Ed.), Monsters and the Monstrous: Myths and Metaphors of Enduring Evil (pp. 45-57). BRILL.

Fisher, M. (2009). Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Zero Books.

Harper, S. (2002). Zombies, Malls, and the Consumerism Debate: George Romero’s Dawn of the Dead. Americana: The Journal of American Popular Culture, 1900 to Present; Hollywood, 1(2), 1-10.

Harvey, D. (2005). A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford University Press.

Hunt, N. (2015). A Utilitarian Antagonist: The Zombie in Popular Video Games. In L. Hubner, M. Leaning & P. Manning (Eds.), The Zombie Renaissance in Popular Culture (pp. 107-123). Palgrave Macmillan.

Hutcheon, L. (1985). A Theory of Parody: The Teachings of Twentieth-Century Art Forms. Methuen & Co.

Jameson, F. (1998). The Cultural Turn: Selected Writings on the Postmodern, 1983-1998. Verso.

Jennings, S.C. (2018). Women Agents and Double-Agents: Theorizing Feminine Gaze in Video Games. In K.L. Gray, G. Voorhees, & E. Vossen (Eds.), Feminism in Play (pp. 235-249). Palgrave Macmillan.

Kee, C. (2017). Not Your Average Zombie: Rehumanizing the Undead from Voodoo to Zombie Walks. University of Texas Press. https://doi.org/10.7560/313176

Leeb, C. (2018). Rebelling Against Suffering in Capitalism. Contemporary Political Theory, 17(3), 263-282. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41296-017-0185-0

Marx, K. (1887). Capital: A Critique of Political Economy: Volume I Book One: The Process of Production of Capital. Progress Publishers. (Original work published 1867)

Naughty Dog. (2013). The Last of Us. [Sony PlayStation 3]. Digital game directed by B. Straley & N. Druckmann, published by Sony Computer Entertainment.

Naughty Dog. (2014). The Last of Us: Left Behind. [Sony PlayStation 3]. Digital game directed by B. Straley & N. Druckmann, published by Sony Computer Entertainment.

Pokornowski, S. (2013). Insecure Lives: Zombies, Global Health, and the Totalitarianism of Generalization. Literature and Medicine, 31(2), 216-234. https://doi.org/10.1353/lm.2013.0017

Rocketcat Games & Madgarden. (2016). Death Road to Canada. [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game designed by K. Auwae, published by Ukiyo Publishing Limited & Noodlecake Studios.

Romero, G. A. (Director). (1968). Night of the Living Dead. [Film]. Image Ten.

Romero, G. A. (Director). (1978). Dawn of the Dead. [Film]. Laurel Group.

Russworm, T.M. (2017). Dystopian Blackness and the Limits of Racial Empathy in The Walking Dead and The Last of Us. In J. Malkowski & T.M. Russworm (Eds.), Gaming Representation: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in Video Games (pp. 109-128). Indiana University Press.

Schmeink, L. (2016). “Scavenge, Slay, Survive”: The Zombie Apocalypse, Exploration, and Lived Experience in DayZ. Science Fiction Studies, 43(1), 67-84.

Taylor, L.N. (2009). Gothic Bloodlines in Survival Horror Gaming. In B. Perron (Ed.), Horror Video Games: Essays on the Fusion of Fear and Play (pp. 46-61). McFarland & Co.

Telltale Games. (2012). The Walking Dead. [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by S. Vanaman et al., published by Telltale Games.

Telltale Games. (2013-2014). The Walking Dead: Season Two. [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by D. Lenart et al., published by Telltale Games.

Tyner, J. A. (2019). Dead Labor: Toward a Political Economy of Premature Death. University of Minnesota Press.

Valve. (2009). Left 4 Dead 2. [Xbox 360]. Digital game designed by M. Booth, published by Valve.

Weise, M. (2009). The Rules of Horror: Procedural Adaptation in Clock Tower, Resident Evil, and Dead Rising. In B. Perron (Ed.), Horror Video Games: Essays on the Fusion of Fear and Play (pp. 238-266). McFarland & Co.

Wilson, J. A. (2017). Neoliberalism. Routledge.