Identifying with Lack: The Enjoyment of Nonbelonging in Her Story

by Benjamin NicollAbstract

The notion of complete identification in videogame play, wherein the player undergoes a state akin to entering someone else’s skin, is a myth. Psychoanalysis, like critical race theory, post-phenomenology and cultural studies, lends support to this observation. But psychoanalysis also retains a normative theory of successful identification, even as it rejects the possibility of complete identification. For psychoanalysis, identification paradoxically succeeds when the subject identifies with the very failure, or “lack,” that constitutes their subjectivity. Distinguishing between the fantasmatic pleasure of complete identification and the enjoyment of identifying with lack, this article argues that the failure to identify with on-screen referents in videogame play is unconsciously satisfying because it reproduces the constitutive failure of subjectivity. The article draws on an analysis of Her Story (Barlow, 2015) to make this argument.

Keywords: avatar identification, big Other, interpassivity, jouissance, Lacan, mirror stage, player identification, psychoanalysis, representation

Introduction

The question of how, or indeed whether, videogame players identify with their on-screen referents continues to animate popular and scholarly debates about the medium. The popular view tends to be that playing videogames is akin to entering someone else’s skin. Most videogame theorists reject this commonsense conception of player identification. Lisa Nakamura (2000, see also 2020), for example, argues that the very notion that players can and should embody their on-screen referents is an Orientalist fantasy. Brendan Keogh rejects the dual relation between player and on-screen referent altogether, proposing instead that “the actual actor active in videogame play is in fact a hybrid of both player and game” (2014, n.p.). Adrienne Shaw (2014) challenges the assumption that player identification relies on shared identity markers between player and avatar. Instead, she finds that player identification is a radically contextual process wherein players may, for example, identify with character traits, narrative situations and play mechanics that both resonate with and diverge from their own identities and experiences.

Based on these accounts, complete identification in videogame play might be considered a myth. This view finds support not only from critical race theory, post-phenomenology and cultural studies, as exemplified by Nakamura, Keogh and Shaw, but also from psychoanalysis. According to psychoanalysis, complete identification with oneself, let alone with a representation of oneself or the symbolic position from which one views oneself, is always and already a failure. The failure to identify completely with oneself is, for psychoanalysis, the constitutive failure of subjectivity. The subject tries to identify with the signifiers it uses to represent itself. But the subject’s conscious wish to achieve parity with itself is invariably undermined by its unconscious desire, the latter of which might manifest in, for example, a slip of the tongue (I try to convey something about myself, but I misspeak in a way that suggests the opposite of my intended meaning) or bungled action (I believe I am a particular type of person, but my actions reveal a repeated failure to be that person). To be a subject is to be divided from oneself in this sense. As Slavoj Žižek puts it, “the subject endeavours to adequately represent itself, this representation fails, and the subject is the result of this failure” (2012, p. 174, italics in original).

Psychoanalysis is not unique in rejecting the possibility of complete identification. But as Žižek emphasises, what is unique about the psychoanalytic conception of identification is the idea that subjectivity is the result of a failed identification. For theorists such as Nakamura, Keogh and Shaw, identification fails because no representation, videogame or otherwise, can possibly approximate the radical contextuality of subjectivity. According to this line of thought, subjectivity comes first and the failure of identification second. But for psychoanalysis, the failure of identification precipitates the formation of subjectivity. Subjectivity emerges from a failure to fully integrate oneself into a symbolic identity. This reversal of the usual way we think about the relationship between subjectivity and identification enables psychoanalysis to go where other theories of player identification do not. It gives us territory to explore a normative theory of successful player identification, without losing sight of the critique of complete identification.

This may sound odd -- how could identification succeed if not through complete (or even partial) identification with oneself (or a representation of oneself)? For psychoanalysis, identification paradoxically succeeds when the subject identifies with the very failure, or “lack,” that constitutes their subjectivity. For the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, all speaking subjects are lacking subjects. Language inaugurates a split in subjectivity that ensures the subject’s conscious intentions fail to coincide with their unconscious desire. As Bruce Fink explains, “it is language that, while allowing desire to come into being, ties knots therein, and makes us such that we can both want and not want one and the same thing, never be satisfied when we get what we thought we wanted, and so on” (1995, p. 7). Successful identification, in this context, means identifying with a lack that manifests itself in both the “ideal ego” (an ideal representation one attempts to embody) and “ego ideal” (the symbolic position from which one views oneself) (see Freud, 1957, p. 94). Here, psychoanalysis makes an important distinction between the fantasmatic pleasure of complete identification and the enjoyment, or what Lacan calls jouissance, of identifying with lack. While the subject’s conscious wish is to gain mastery over its existence by identifying completely with itself, its unconscious desire is to fail to satisfy this wish, and it derives an odd sort of satisfaction from the repetition of this failure.

It is my contention, therefore, that while the player’s conscious wish may be to locate themselves in the videogames they play by, for example, identifying with character traits, narrative situations and play mechanics, their unconscious desire is to enjoy their repeated failure to identify with their on-screen referents. The failure of player identification is unconsciously satisfying because it reproduces the constitutive failure of subjectivity. What keeps us coming back to videogames is not the fantasmatic pleasure of complete identification but the enjoyment of identifying with lack. For psychoanalysis, then, the truth of player identification consists in the contradiction between the popular view (which holds that player identification is too successful) and the prevailing scholarly view (which argues that complete identification is a myth): identification succeeds, but it succeeds only to the extent that it fails.

In what follows, I explore the critical implications of this claim with reference to the videogame Her Story (Barlow, 2015). I treat Her Story not as a case study per se but as a text that performs theoretical work for me. In doing so, I propose three interlinked modes of player identification: imaginary, symbolic and real. Imaginary identification is the player’s attempt to identify with an image of who or what they want to be. This mode of identification fails, not simply because of the radical contextuality of player identity, but because there is a “lack in the image,” an ontological gap in the visual field that prevents the player from achieving parity with what they see [1]. Symbolic identification is the player’s answer to the failure of imaginary identification. It describes a process where the player calls upon the assent of a naïve observer -- a figure Lacan calls the Other -- to ratify their imaginary relation with their on-screen referents. Yet, like imaginary identification, symbolic identification fails, because there is also a “lack in the Other,” an ontological gap in the symbolic field that ensures no final answer to the question, “what am I?” [2]. Despite these failures, players typically ascribe fantasmatic pleasure to imaginary and symbolic identification (see Nicoll, 2022; 2023a; 2023b). The pleasure ascribed to imaginary and symbolic identification may be as conformist as, say, identifying with a character who shares similar identity markers to one’s own, or as nonconformist as, say, identifying with a queer mode of videogame play (see Ruberg, 2019). But the psychical satisfaction of playing videogames consists in the failure to attain either imaginary fulfilment or symbolic recognition. Real identification is what happens when the player successfully identifies with, and subsequently enjoys, their inability to fit within the assigned places of belonging in videogame play. It is in this sense that videogame play can be understood as a staging ground for the constitutive failure of subjectivity.

Imaginary identification

It is thanks to the first wave of psychoanalytic screen theory that Lacan’s theory of imaginary identification is so widely known, and yet so widely misunderstood, in media and cultural studies. At its core, imaginary identification is “identification with the image in which we appear likeable to ourselves, with the image representing ‘what we would like to be’” (Žižek, 2008a, p. 116). Screen theorists such as Daniel Dayan (1974), Christian Metz (1982) and Laura Mulvey (1975) developed an understanding of this mode of identification based on readings of Lacan’s (2006) mirror stage paper, his theory of the gaze (Lacan, 1998) and Jacques-Allain Miller’s (1978) exposition of Lacan’s concept of suture. Their objective was to understand how films were able to interpellate viewers as, for example, gendered subjects. But more recently, Lacanian film theorists such as Joan Copjec (2015), Todd McGowan (2007; 2015) and Slavoj Žižek (2001) have argued that screen theory largely overlooked the constitutive role of failure in imaginary identification, focusing as it did on how films successfully interpellated viewers (see McGowan, 2015, pp. 56-75 for an overview of this critique). Psychoanalytic theories of player identification often take inspiration from screen theory and, as a result, tend to repeat the error of overlooking the constitutive role of failure in imaginary identification (see, for example, Kennedy, 2002: n.p.; Kinder, 1991, p. 95; Rehak, 2003, pp. 103-104). Jan Jagoszinski (2007) develops a more explicitly Lacanian theory of player identification but is more concerned with its fantasmatic power than its constitutive failure (see also Goetz, 2023) [3]. My rationale for beginning with imaginary identification is, then, twofold. First, imaginary identification is the dimension of Lacan’s thought most familiar to videogame and media theorists. Second, it is, or at least should be, the starting point for understanding the foundational role of failure in any act of identification.

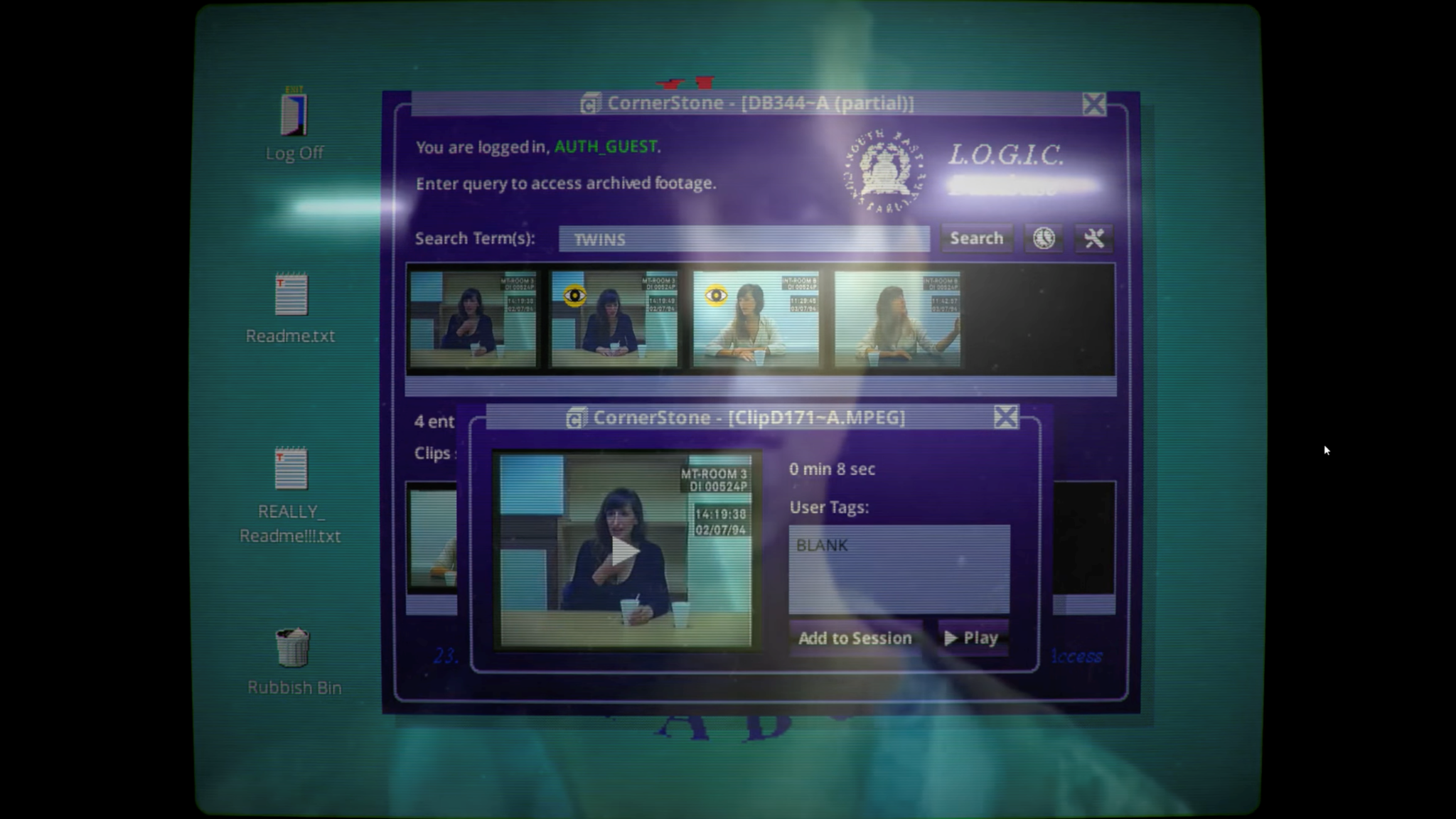

Her Story provides a neat introduction to the process of imaginary identification. In the game, players inhabit a first-person view of a 1990s-era computer monitor. The computer is running software called “L.O.G.I.C. Database,” a searchable archive of video-recorded police interviews. The game begins with the search term “MURDER” prefilled in the database search box. Searching the database for this term yields four live-action video clips of a woman being questioned by police. All four of these initial clips, and all 271 clips contained in the database, feature live-action footage of the same female actor (Viva Seifert). While police questions can be inferred from the woman’s testimonials, players never see or hear directly from police in any of the video recordings. In the first clip players are likely to watch, the woman says “you think it’s murder? I mean, clearly, it’s murder.” In the second clip, the woman mentions “Simon’s murder.” If players search for “SIMON,” the database returns 61 unique results but limits access to the first five entries. To solve the murder mystery, then, players must identify or infer phrases of interest from the woman’s testimonials and make targeted keyword searches to uncover more clips from the database.

Mirrors are a recurring motif throughout Her Story. In a clip that players are likely to uncover early on, the woman introduces herself to her unseen interrogator as Hannah, and remarks that while her name is a palindrome, it will not appear symmetrical if reflected in a mirror (Figure 1). Hannah’s deceased partner, Simon, worked at a glazier, where he made a mirror for Hannah as a gift -- a mirror that, players later learn, was used as a weapon in Simon’s murder. A “Mirror Game” file can be found in the computer’s trash bin. The game, which is playable on the diegetic desktop display, is Reversi, a variation on the two-player board game Othello. The player unlocks a special achievement if they bring the game to a stalemate.

Figure 1. Screenshot from Her Story (Barlow, 2015), taken by author. Click image to enlarge.

The most significant mirror motif for our purposes, however, is that Hannah might have an identical twin sister: Eve. According to Hannah’s fragmented testimonial, she was separated from Eve at birth. The girls’ midwife faked Eve’s death because she wanted a child for herself. Eve subsequently lived with the midwife, while Hannah lived with her biological parents. Hannah one day discovered Eve by peering into the windows of the midwife’s house. The two played a “mirror game” that involved copying each other’s gestures. The girls eventually met but decided to keep their discovery hidden from their parents. They continued to live as one person -- Hannah -- by mirroring each other’s activities. If Hannah made a friend, for example, Eve would befriend that person. While the ruse works for the most part, the twins fail to consistently embody the ideal image of Hannah. They bungle their actions, and their romantic relationships create rifts in their own relationship.

In its opening vignettes, Her Story works through the basics of Lacan’s oft-cited concept of the mirror stage. Lacan (2006) claims that between the ages of six to eighteen months, the infant starts to identify with its mirror reflection. The infant subsequently forms an ideal image of itself as a unified and self-mastering being, where previously it experienced the world as an undifferentiated bundle of drives. Imaginary identification of the sort typified by the mirror stage is not restricted to childhood experience, however, and it is not restricted to the act of looking at oneself in the mirror. Imaginary identification is at work in any psychical process -- which may or may not be visual -- wherein the subject attempts to embody an ideal image (such as, for example, the ideal image of Hannah). Sigmund Freud’s term for the ideal image is the “ideal ego” (1957, p. 94).

The image of bodily wholeness perceived in the mirror is, however, a false one, as it obscures the subject’s lack. For Lacan (2014, pp. 315-316), subjectivity is ontologically lacking. To be a subject is to lack the object that would satisfy desire completely. The absence of such an object causes desire to slip from one object to another. The subject tries to fill its lack by attaining various objects of desire, but because its object-cause of desire is constitutively absent, the subject can only ever run circles around its lack (see Lacan, 1998, p. 178 for a schematic representation of this process). The ideal image is seductive because it offers an impression of imaginary wholeness in place of a constitutive lack. In this sense, the very notion of identifying completely with oneself or with an image of what one aspires to be is nothing but a fantasy brought on by the mirror stage, the inaugural moment of (mis)recognition. Screen theorists such as Dayan (1974), Metz (1982) and Mulvey (1975) drew attention to this dimension of imaginary identification to account for the seductive power of the cinematic image.

But while the ideal image does indeed offer an impression of imaginary wholeness, it never succeeds in blotting out lack entirely. For example, when we look in the mirror, we might fixate on the parts of our bodies we find most unappealing: on what, colloquially speaking, we lack. But the lack of, for example, a conventionally attractive physique is not the same as the constitutive lack that defines subjectivity. The former is empirical, whereas the latter is ontological. The mirror reflection transfers our constitutive lack onto an empirical deficit, and this is key to its psychic appeal. If I look in the mirror and see nothing but a lacking body in the colloquial sense, this might motivate me to work out more or cut out junk food. But even if I successfully attain the physique I desire, my constitutive lack will find expression in some other form in my image. The subject’s lack of oneness with itself ensures that it never fits into its image without leaving a remainder, and this remainder manifests itself as a lack in the image. The lack in the image can appear in the guise of an empirical deficit, but it nonetheless functions ontologically to prevent the subject from coinciding completely with itself. It is this lack in the image that prompts new Lacanian film theorists, such as Copjec (2015), McGowan (2007, 2015) and Žižek (2001), to shift our attention from the seductive power of imaginary identification to its constitutive failure.

We can return to Her Story for an illustration of the lack in the image. As the player learns more about Eve, Hannah’s twin sister, a division emerges in the image. What at first appeared to be a single woman in the police interviews -- Hannah -- may in fact be two women, both masquerading as Hannah. However, because Eve never identifies herself, and because in most clips the women are both playing the role of Hannah, it is difficult to tell the twins apart. But should Hannah’s testimonial be trusted in the first place? Is Eve a real person, or has Hannah (or Eve, for that matter) constructed the story to mislead the police interrogators? Fans of the game are divided on which explanation is the most convincing. Viewed through a Lacanian lens, however, the “secret” of Hannah’s subjectivity is far more obvious than it first appears. Hannah, like all speaking subjects, is a lacking subject. She is not identical with herself. Her attempt to fully integrate herself into her ideal image fails. This failure manifests itself as a lack in the image, an antagonism that motivates the player’s own desire for imaginary fulfilment. The player is encouraged to establish a coherent avatarial identity for Hannah by piecing together her fragmented testimonials, but this quest for completion leads inexorably to failure.

In this way, Her Story not only dramatizes the failure of imaginary identification through its narrative; it also enacts this failure by staging an encounter between the player and the lack in the image. Rather than satisfying the player’s desire for imaginary fulfilment by progressively resolving the contradiction in Hannah’s subjectivity, Her Story is structured such that the lack in the image becomes increasingly intractable as the player progresses. This mimics the process by which the subject encounters its own lack in any act of imaginary identification. When the subject tries to embody its ideal image, it invariably encounters its own lack as a disruption in the visual field. The failure of imaginary identification, as Lacan understands it, is not an intimate failure -- it is not a failure subjects encounter through introspection -- but is instead an “extimate” failure, a failure that manifests itself as a disruption in the visual field (on extimacy, see Lacan, 1997, p. 139). A persistent misconception about psychoanalysis is that it is founded on a depth model of the psyche, where the subject’s true desires are buried deep within. But Freud’s insight is practically the opposite: unconscious desire is “out there,” implicated in the very patterns and disorders that the subject believes it is separate from (Žižek, 2008b, p. 1; the classic example of this is a slip of the tongue). As McGowan puts it, the subject’s lack “defines the visual field through the distortion that it creates, but most of the time, it remains difficult to detect even as it motivates the subject’s act of seeing” (2015, p. 72). Imaginary identification in videogame play is impossible not simply because there is a mismatch between the player’s identity and the content of the image, but because the player’s lack distorts the very image they try to inhabit (see Nicoll, 2022; Taylor, 2003). Her Story renders this lack in the image apparent through the lack in Hannah -- a lack that the player tries but invariably fails to amend.

Symbolic identification

Symbolic identification is what happens when the player calls upon the Other to answer for the failure of imaginary identification [4]. For Lacan, the Other is not a substantive entity. It is more like a faceless authority that, in Žižek’s terms, represents “the substance of our social being, the thick social network of written and unwritten rules and patterns” (2022, p. 62). In any act of identification, the subject turns to the Other to authenticate its imaginary relation with its image. As Lacan puts it, the subject “call[s] upon the assent” of the Other to “ratify the value of [its] image” (2014, p. 32). If imaginary identification is “identification with the image in which we appear likeable to ourselves,” then symbolic identification is “identification with the very place from where we are being observed, from where we look at ourselves so that we appear to ourselves likeable, worthy of love” (Žižek, 2008a, p. 116, italics in original). Like imaginary identification, however, symbolic identification fails, and it is important to understand how this failure transpires in videogame play. But symbolic identification can also function as a bulwark against the failure of imaginary identification.

Although Lacan’s (2006) 1949 paper on the mirror stage focuses on the process of imaginary identification, his conception of the mirror stage later evolves to incorporate aspects of symbolic identification. In Seminar X, for example, he claims that when the infant is confronted with its mirror reflection, it often turns to its caregivers -- who give face to the symbolic authority of the Other but are not themselves the Other -- in a bid to secure support for its trepidatious attempts at imaginary identification (Lacan, 2014, p. 32). The infant’s caregivers might respond by offering support in the form of verbal encouragement: “yes, baby, that’s you in the mirror!” The effect of this encouragement is not simply that the infant achieves parity with its mirror reflection but that it identifies with the symbolic identity (“you,” “baby,” etc.) given to it by its caregivers, thereby facilitating its entry into the social order as a signifier. The infant is subsequently inscribed in the symbolic field insofar as it identifies with the desire of the Other, or with what Freud calls the mediating role of the “ego ideal” (as against “ideal ego” or ideal image, discussed in the previous section) (1957, p. 94). Symbolic identification is an important developmental stage because it means that the infant is identifying itself as a signifier in the locus of the Other rather than just an image over which it has mastery. In any act of symbolic identification, the subject identifies itself as a signifier that relates to other signifiers by means of the mediating role of the Other.

Identification in videogame play is not simply a process where the player attempts to establish an imaginary relation with their on-screen referents; it is also an attempt to ratify the very terms of this relation by means of the mediating role of the Other. We can again turn to Her Story for an illustration of this process. At key points in Her Story, the office lights reflected on the diegetic computer screen flicker, giving us a brief glimpse of a figure looking at the screen (the figure whose perspective players inhabit) (Figure 2). The figure looks like Hannah. The player never sees the figure in full, however, and while the identity of the figure is eventually revealed -- she is Sarah, Hannah’s daughter -- the game does not explain what Sarah is trying to discover (or indeed what she does discover) by watching Hannah’s testimonials. At the very end of the game, the player is prompted to open a chat window on the diegetic desktop display, where an anonymous character asks Sarah if she understands why her mother did what she did. The player can answer yes or no (neither answer reveals additional information), at which point the game ends.

Figure 2. Screenshot from Her Story (Barlow, 2015), taken by author. Click image to enlarge.

The spectral presence of Sarah can be read as a very literal representation of the ego ideal, the Other who mediates all acts of imaginary identification in videogame play. Imaginary identification must be given support by the attending gaze of the Other. It is implied that Sarah identifies completely with the image of Hannah. It is through Sarah, then, that the player authenticates their own relation to what they see. In this way, the spectral presence of Sarah works to cover over the lack in the image.

In her book Gaming at the Edge, Shaw (2014) provides an empirical study of symbolic identification in videogame play (although she does not draw on psychoanalytic terminology to theorize her findings). Her book asks whether videogame players identify as their on-screen referents and concludes that, for the most part, they do not. While she finds evidence to suggest that players sometimes identify “with” (rather than “as”) certain character traits, narrative situations and play mechanics, her findings nonetheless affirm the idea that imaginary identification in videogame play is more of a failure than it is a success (Shaw, 2014, pp. 55-56). Moreover, Shaw finds that players whose identities are underrepresented in videogames do not themselves place much stock in their ability to identify with their on-screen referents. Seeing certain aspects of their identities represented in videogames is, for Shaw’s interviewees, “nice when it happens,” but it is not the “driving factor in [their] media consumption” (2014, p. 209, 212) [5]. While underrepresented players may not identify completely (or even partially) with, for example, videogame characters with whom they share similar identity markers, Shaw (2014, pp. 211-212) finds that they nonetheless tend to take pleasure in the idea that other players might be identifying with characters who look like them. In psychoanalytic terms, while Shaw’s interviewees do not themselves place much stock in their ability to identify with their on-screen referents (imaginary identification), they still believe in the pleasure of identification through the mediating role of the Other (symbolic identification).

Viewed this way, the very notion of identifying completely (or even partially) with an on-screen referent in videogame play can be understood as what Robert Pfaller (2014) calls an “illusion without an owner.” Player identification is a powerful illusion not because everyone believes in it but because everyone believes the Other believes in it. Pfaller (2017) develops the concept of “interpassivity” -- which he derives from Lacan -- to describe the psychical process of outsourcing one’s belief in the pleasure of a cultural activity to the Other [6]. For him, there is a “double delegation” at work in any interpassive exchange (Pfaller, 2017, p. 7). In videogame play, for example, the interpassive player first delegates the fantasmatic pleasure of complete identification to an external agent -- for example, another player whose imaginary identification allegedly succeeds where the interpassive player’s fails. The interpassive player also delegates a belief in the very ruse of the interpassive exchange to the Other. Interpassive activities such as taking pleasure in imaginary identification without it succeeding are pleasurable not because we take pleasure in them but because we believe the Other believes we take pleasure in them. In the subject’s fantasy space, the Other “provides the necessary fictional guise” for the interpassive act by believing where the subject doubts, and this psychical pact with the Other frees the subject to take pleasure in its (non-)activity (Friedlander, 2018, p. 95).

Importantly, the interpassive player in this scenario does not occupy the position of what Lacan (1973) might call the “non-duped” -- that is, the cynic who dismisses diverse representation in videogames as nothing but empty virtue signalling. Rather, as Jennifer Friedlander argues, the genuinely interpassive subject “embrace[s] the illusion as an illusion” by believing in a “naïve observer” who “provides the necessary fictional guise for us to engage together in shared pleasures” (2018, p. 95). For Shaw (2014, pp. 211-212), the fact that underrepresented players delegate the fantasmatic pleasure of complete identification to other players and, in so doing, believe in the positive effects of identification through an Other who naïvely believes, is evidence that diversity in representation can be pursued out of a commitment to communal pleasures rather than a self-interested demand to see ourselves more accurately reflected in videogames. This perspective advocates for better and more inclusive representation not because it satisfies our individual egos, but because it satisfies an Other who represents our commitment to shared pleasures as the basis of the social bond. Player identification may be an illusion without an owner, but it is an illusion that can have positive social effects.

However, just as any attempt at imaginary identification is invariably short-circuited by a lack in the image, so too is any attempt at symbolic identification invariably short-circuited by a lack in the Other. The subject attempts to be the symbolic identity it thinks the Other wants it to be, but in so doing it invariably encounters a lack in the Other, a point at which the Other does not know what it wants. There is an ontological incompleteness in the Other that shatters the apparent consistency of the social order and, by extension, the apparent consistency of the subject’s symbolic identity. Jordan Osserman explains the lack in the Other with reference to the infant’s relation to its caregivers:

This Other frustrates the child, for in this process of alienation in the Other it encounters the Other’s own lack; the Other cannot provide the completion that the child desperately seeks. This can be thought of in terms of the mother’s unpredictable comings and goings, which suggest to the child that the (m)Other is wanting, as well as the gap encountered in relation to the mirror image itself, the point where the specular image fails to entirely account for and incorporate the ‘real’ of the body. This induces the child into an attempt to fill in the lack in the Other by becoming that which it presumes the Other lacks. (Osserman, 2022, p. 24)

For Osserman, the subject tries to fill the lack in the Other -- to answer the question of who or what the Other wants it to be -- to “achieve a longed-for coherence” (2022, p. 24). But this quest for symbolic recognition serves only to compound the subject’s alienation in the Other, for the Other is, like the subject, constitutively lacking. If, as Žižek claims, it is something of a theoretical “commonplace that the Lacanian subject is divided, crossed-out, identical to a lack in the signifying chain,” then a far more “radical dimension of Lacanian theory lies in […] realizing that the big Other, the symbolic order itself, is also barré, crossed-out, by a fundamental impossibility, structured around an impossible/traumatic kernel, around a central lack” (2008a, p. 137).

I mentioned above that the figure of Sarah in Her Story represents the spectral presence of the Other, the naïve observer who ratifies the player’s imaginary relation with the image. However, the question of who Sarah really is and what she wants from us remains ambiguous throughout Her Story. What is Sarah trying to discover by searching through the database of police interviews? What does she see in Hannah’s testimonials that we do not? There is, in other words, a lack in Sarah, in the ego ideal, just as there is a lack in Hannah, in the ideal ego. The player is driven by a desire to fill the lack in the Other -- to answer the question of who Sarah is and what she wants from us -- and, in so doing, to attain symbolic recognition. But Her Story provides no closure on Sarah’s motivations for watching Hannah’s testimonials. What we are dealing with in Her Story, then, is a sort of double lack: a lack in the image and a lack in the Other. The lack in Sarah, like the lack in Hannah, short-circuits the player’s attempt to achieve parity with what they see.

The notion of the lack in the Other is what distinguishes Lacan’s theory of symbolic identification from Louis Althusser’s (2014) theory of interpellation. For Althusser (2014, p. 190), interpellation is what happens when “concrete individuals” believe they are the symbolic identities the social order tells them they are (cf. Keever, 2022). The problem with this idea is that it presupposes a consistent social order, an Other who either knows what it wants or naïvely believes in the legitimacy of the symbolic identities taken up by “concrete individuals.” For Althusser, subjectivity is the result of a successful interpellation, but for Lacan, subjectivity is the result of a failed interpellation -- that is, an encounter with the failure of the social order to answer the question, “what am I?” (see Pluth, 2007, pp. 73-74). “When you encounter the gaze of the Other,” as Copjec writes, “you meet not a seeing eye but a blind one. The gaze is not clear or penetrating, not filled with knowledge or recognition […] The horrible truth […] is that the gaze does not see you” (2015, p. 36, italics in original). The subject is constantly turning to the Other in search of a gaze that might lend support to its symbolic identity. It bears repeating that the interpassive gesture of delegating belief in the legitimacy of one’s symbolic identity to the Other is, as Shaw might argue, a necessary one, as it represents our commitment to communal pleasures as the basis of the social bond. But ultimately, “[t]he Other’s desire is a mirror that does not return my reflection,” as Ed Pluth (2007, p. 74) puts it. What is traumatic about encountering the lack in the Other is that it “throws one’s symbolic identity into disarray” (McGowan, 2022a, p. 18). The fantasy of symbolic recognition, even under the guise of an interpassive delegation, works to insulate the subject from an encounter with the lack in the Other (see Žižek, 2008a, pp. 139-144). Real identification is what happens when the subject identifies with, rather than retreats from, this lack.

Real identification

What remains of the player once they are laid bare by the failure of imaginary and symbolic identification? For Lacan, the “subjective destitution” wrought by this failure frees the subject to identify with its symptom -- that is, with its own mode of finding satisfaction in lack (see Žižek, 1999, p. 266). As argued, the subject consciously seeks the fantasmatic pleasure of imaginary fulfilment and symbolic recognition. But it derives an unconscious satisfaction, or enjoyment, from its failure to identify completely with both its image and the gaze of the Other. A psychoanalytic view suggests that players enjoy the failure of identification because it is the closest they can get to inhabiting lack itself -- that is, to inhabiting the inaugural loss that brought them into being as divided subjects. As McGowan puts it, “the subject can enjoy because it does not fit completely in the identity that is laid out for it. Enjoyment consists in the gap between one’s subjectivity and the social identity that has been established for the subject” (2022b, n.p.). The satisfaction of player identification, in this sense, consists not in the fantasmatic pleasure of imaginary fulfilment and symbolic recognition, but in the enjoyment of identifying with lack.

Pleasure and enjoyment are distinct psychical processes. Pleasure, according to Freud’s (1961) theory of the pleasure principle, is experienced in the relief occasioned by the diminution, rather than the intensification, of psychic excitation. Pleasure can be found in, for example, the relief occasioned by winning an online competitive videogame. From a Freudian perspective, the pleasure of playing an online competitive videogame consists not in the intensity of the videogame play itself but in the successful discharge of this intensity. Enjoyment, by contrast, is a by-product of the subject’s unconscious desire to intensify their excitation without successfully discharging it. Players experience enjoyment in what Freud (1955, p. 167) would call the “horror at pleasure” of struggling to win an online competitive videogame, or perhaps even in the agony of losing (see Jagodzinski, 2007, pp. 51-52; Nicoll, 2022, 2023a, 2023b). Importantly, the unconscious desire to enjoy has psychic priority over the conscious wish for pleasure. While the subject’s conscious wish might be to experience the pleasure of winning, its unconscious desire is to enjoy the agony of losing. The subject consciously aims to rid itself of excitation by obtaining its object of desire, but it derives an unconscious satisfaction from repeatedly missing its object (Freud, 1961; see also Lacan, 1998, p. 178). The subject is impelled to manufacture situations for itself where it can reproduce, and subsequently enjoy, the loss of its object.

Freud (1961, pp. 8-11) provides a famous case study of this phenomenon in Beyond the Pleasure Principle. In this article, he describes witnessing his grandson, Ernst, play a game with a reel on a string. When alone, Ernst would throw the reel from his cot and, using the string coiled around it, pull it back in again. When the reel was overboard and out of view, Ernst would mutter “o-o-o-o,” which Freud suggests was his attempt at saying “fort” (gone). When Ernst retrieved the reel, he would say “da” (here). What intrigues Freud about Ernst’s play is that while his grandson derived “greater pleasure” from the retrieval of the reel, he was more psychically invested in “the first act, that of departure,” which he “staged as a game in itself far more frequently than the episode in its entirety” (1961, p. 10). On the one hand, then, Ernst’s play seems to affirm the primacy of the pleasure principle. Ernst experiences a “greater pleasure” in the discharge of excitation occasioned by the successful retrieval of the reel (Freud, 1961, p. 10). But as Freud recognizes, the pleasure principle cannot explain the surplus satisfaction Ernst derives from the seemingly unpleasurable act of repeatedly discarding the reel. This case study, among countless others from his clinical practice, prompts Freud (1961) to hypothesize the existence of a death drive -- a drive that impels the subject to repeat painful experiences. When the subject satisfies its death drive, Freud speculates, it generates a satisfaction for itself that goes beyond the pleasure principle. Lacan’s term for this satisfaction in dissatisfaction is enjoyment.

As in Ernst’s play, the enjoyment of videogame play consists not in the fantasmatic pleasure of attaining fulfilment and recognition but in the act of repeating the constitutive failure of subjectivity (see Nicoll, 2022; 2023a; 2023b). In this sense, the enjoyment of playing Her Story consists in searching for, but ultimately failing to find, a phrase that would reveal a video clip that would enable the player to determine who Hannah really is and why they are playing as Sarah. Like most videogames, Her Story is structured to make players feel as if they are constantly on the verge of finding this missing signifier. There is even an application on the game’s diegetic computer that displays the amount of video clips the player has successfully found and watched. The player might therefore hypothesize that a clip exists that could explain everything. But once the player exhausts all possible search terms, it becomes clear that no such missing signifier exists. In this way, Her Story retroactively reveals that the player’s satisfaction consisted not in the fantasmatic pleasure of successfully attaining the missing signifier but in the enjoyment of incessantly circling the lack in both the image and the Other.

In this sense, the experience of playing Her Story is akin (but not identical, of course) to the process of undergoing psychoanalysis itself. In psychoanalytic therapy, the analyst infamously refuses to offer the patient imaginary fulfilment and symbolic recognition. The patient may try to position the analyst as an ideal ego, as a role model to embody, but the analyst refuses to occupy this role for the patient (see Lacan, 1998, pp. 271-272). Likewise, the patient may seek symbolic support from the analyst in the form of validation, encouragement, or reassurance, but the analyst responds to the patient’s demands for recognition with more questions or, perhaps even more frustratingly for the patient, with nothing but silence. This may seem cruel on the part of the analyst, but it has a very important purpose. By enacting the patient’s failure to identify with their ideal ego and ego ideal in the therapeutic relation, the analyst aims to draw out the patient’s unconscious rationale for seeking imaginary fulfilment and symbolic recognition in the first place. Once the patient exhausts their attempts at identification, they often resort to “unconscious speech” -- that is, they begin to speak to their analyst not through “ego discourse” but through symptoms, slips of the tongue, bungled actions, dreams and so on (Fink, 1997, p. 46). These unconscious speech acts are very important for the analyst because they reveal, albeit obliquely, where, how and why the patient’s enjoyment is implicated in the very patterns and disorders that drove them to seek therapy in the first place.

Psychoanalytic therapy succeeds not when the patient identifies with the analyst as a role model or receives recognition from the analyst in the form of encouraging advice, but when they identify with the lack in the therapeutic relation. The patient, like the player in Her Story, throws out signifier after signifier, hoping that the Other will eventually hear them. But the necessary trauma of undergoing psychoanalysis is that the analyst responds to the patient’s ego discourse with nothing but silence, or at best with more questions. The effect of this is that the patient eventually recognizes that there is no Other who knows, no ineffable secret that would provide a final answer to the question, “what am I?” In this sense, the “subject” of psychoanalysis consists not in the diagnostic category assigned to the patient by the analyst, nor in the ego discourse that the patient hides behind to avoid an encounter with lack. Instead, the subject of psychoanalysis consists in the enjoyment that pulses around the lack in the therapeutic relation, and the analyst’s task is to help the patient identify with this enjoyment. In a similar vein, the “subject” of videogame play is not the consciously thinking person who types words into Her Story’s diegetic computer. Instead, the subject of videogame play consists in the enjoyment that pulses around the lack in both the image and the Other. This is the kind of subject that Her Story brings to the fore through its ludonarrative structure.

Real identification has important implications for the politics of player identification. In his book Enjoyment Right & Left, McGowan (2022a) theorizes the political implications of the “enjoyment of nonbelonging” to which my title refers. For McGowan, a psychoanalytically informed politics of emancipation must be organized around the enjoyment of a shared failure to belong -- that is, a shared identification with lack -- rather than the pleasure of inhabiting a particular symbolic identity. As he writes, “[t]o struggle for emancipation is to find oneself without a group that would give one an identity. Leftism has nothing to hold people together other than their commitment to a shared failure to belong and the enjoyment that this failure provides” (McGowan, 2022a, p. 26). The pleasure of belonging can, of course, have important personal and political functions. But as McGowan (2022a, pp. 105-110) argues, any political project organized around the pleasure of belonging runs the risk of reproducing a Schmittian distinction between friend and enemy, between those who belong and those who do not. The enjoyment of nonbelonging, by contrast, “is available to everyone because no one can assuredly belong” (McGowan, 2022a, p. 21). McGowan (2022a, pp. 91-97) is careful to distinguish this enjoyment from the transgressive or carnivalesque hedonism that might be associated with, say, the storming of the U.S. Capitol Building in 2021. Transgression, even in its more progressive guises, reinstates what McGowan calls a “conservative opposition between the friends of the social order and its enemies who transgress its edicts” (2022a, p. 92). The subject who enjoys their nonbelonging in the social order recognizes that all belonging is fundamentally illusory. They achieve solidarity with other subjects by identifying with a shared failure to belong. For McGowan, enjoyment is the index of this solidarity.

The politics of player identification is usually thought of as a struggle for better and more inclusive representation in videogame play. As argued, there is an interpassive dimension to this struggle. It is possible to pursue better and more inclusive representation in videogame play out of a commitment to shared pleasures rather than a desire for individual ego-fortification. But psychoanalysis also enables us to conceive an alternative politics of player identification. If, as I have argued, player identification is a staging ground for the constitutive failure of subjectivity, then it is also a means by which to engage in the enjoyment of nonbelonging described by McGowan. Videogames such as Her Story are political, in this sense, because they corral us -- against our conscious wishes, perhaps -- into an identification with this position of nonbelonging.

Conclusion

Player identification fails, not simply because player identity is radically contextual, but because subjectivity is defined by a constitutive failure. For psychoanalysis, we are not even identical with ourselves let alone our mirror reflections or videogame avatars. Early psychoanalytic theorists of player identification, such as Bob Rehak (2003) and Sherry Turkle (1995), rightly observed that videogame play is not simply a form of escapism wherein players experiment with or take on different identities. Rather, it is an exploitation of the avatarial (non-)relation we always and already have with ourselves. As Rehak writes, “[i]f the mirror stage initiates a lifelong split between self-as-observer and self-as-observed, then, in one sense, we already exist in an avatarial relation to ourselves” (2003, p. 123; see also Turkle, 1995, pp. 178-179). What these theorists missed, however, is the constitutive role of failure in any act of player identification. By exploiting this failure, videogames tap into an enjoyment of nonbelonging that all subjects of language experience in common. The enjoyment of nonbelonging is psychically satisfying because it reproduces the constitutive failure of subjectivity. In so doing, however, it “throws one’s symbolic identity into disarray” (McGowan, 2022a, p. 18). It is for this reason that most videogames, unlike Her Story, do not explicitly avow the failure of imaginary and symbolic identification, much less encourage players to identify with this failure. But even when this failure is not explicitly avowed, and even when videogames do not corral players into a process of real identification in the way Her Story does, the enjoyment of nonbelonging still informs the psychical satisfaction of videogame play. Identification succeeds when the player identifies the lack in both the image and the Other as their own. It succeeds when the player recognizes that their satisfaction is a matter of failing to fit within the assigned places of belonging in videogame play.

Endnotes

[1] Rather than explicitly invoking the phrases “lack in the image” and “lack in the Other,” Lacan tends to schematize them in algebraic form. In Seminar X, for example, he schematizes the lack in the image as a minus-phi (Lacan, 2014, p. 39; see also pp. 44-51).

[2] Lacan schematizes the lack in the Other as a barred-A (see, for example, pp. 22-27 of Seminar X). See also Žižek (2008a, p. 93 onwards) for a more detailed theorization of the lack in the Other.

[3] Jagoszinski (2007, pp. 51-52) does, however, make an important connection between failure and enjoyment in videogame play, which is an idea I develop further in this article and elsewhere (see Nicoll, 2022; 2023a; 2023b).

[4] My framing here perhaps misleadingly suggests that there is a causal link between imaginary and symbolic identification, but it would be more accurate to say that that they are knotted together (see Soler, 2024, pp. 23-24).

[5] Shaw interprets this “nice when it happens” refrain as a “defense mechanism” on the part of marginalized players against having to shoulder the burden of demanding better and more inclusive representation in videogames (2014, p. 217).

[6] Sonia Fizek (2018; 2022) applies the concept of interpassivity to videogame play more broadly. As she argues, much of what constitutes videogame play is an interpassive process where the player delegates their pleasure to an external agent -- a Twitch streamer, for example, or an idle videogame that effectively plays itself without human input -- and, in so doing, enjoys vicariously through that agent. Here, I build on Fizek by considering player identification as an interpassive activity, but I do so by paying closer attention to the psychical dimensions of interpassivity.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Ben Egliston, Brendan Keogh, Erin Maclean, Dan Padua, Britt Wilkins and the anonymous reviewers, whose feedback on earlier drafts inspired significant improvements in the final article. I would also like to thank Lee Dallas, Ryan Wright and the Game Studies editors for their guidance throughout the publication process.

References

Althusser, L. (2014). On the Reproduction of Capitalism: Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses. Trans. G. M. Goshgarian. Verso.

Barlow, S. (2015). Her Story [multiplatform]. Digital game directed by Sam Barlow, published by Sam Barlow.

Copjec, J. (2015). Read my Desire: Lacan Against the Historicists. Verso.

Dayan, D. (1974). The Tutor-Code of Classical Cinema. Film Quarterly, 28(1): 22-31.

Fink, B. (1995). The Lacanian Subject: Between Language and Jouissance. Princeton University Press.

Fink, B. (1997). A Clinical Introduction to Lacanian Psychoanalysis: Theory and Technique. Harvard University Press.

Fizek, S. (2018). Interpassivity and the Joy of Delegated Play in Idle Games. Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association, 3(3), 137-163.

Fizek, S. (2022). Playing at a Distance: Borderlands of Video Game Aesthetic. MIT Press.

Freud, S. (1955). The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud: Volume X. Ed. and Trans. J. Strachey. The Hogarth Press.

Freud, S. (1957). The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XIV (1914-1916). Ed. and Trans. J. Strachey. The Hogarth Press.

Freud, S. (1961). Beyond the Pleasure Principle. Trans. J. Strachey. New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company.

Friedlander, J. (2018). Interpassivity: Bonds of Pleasure and Belief. Continental Thought & Theory, 2(1), 91-103.

Goetz, C. (2023). The Counterfeit Coin: Videogames and Fantasies of Empowerment. Rutgers University Press.

Jagodzinksi, J. (2007). Videogame Cybersubjects: Questioning the Myths of Violence and Identification (Implications for Educational Technologies). The Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 53(1): 45-62.

Keever, J. (2022). Videogames and the Technicity of Ideology: The Case for Critique. Game Studies, 22(2). https://gamestudies.org/2202/articles/gap_keever

Kennedy, H. (2002). Lara Croft: Feminist Icon or Cyberbimbo? On the Limits of Textual Analysis. Game Studies 2(2). https://www.gamestudies.org/0202/kennedy/

Keogh, B. (2014). Across worlds and bodies: Criticism in the age of video games. Journal of Games Criticism, 1(1). http://gamescriticism.org/articles/keogh-1-1/

Kinder, M. (1991). Playing with Power in Movies, Television, and Video Games: From Muppet Babies to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. University of California Press.

Lacan, J. (1973). The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XXI: The Non-Duped Err. Trans. C. Gallagher. http://www.lacaninireland.com/web/translations/seminars/

Lacan, J. (1997). The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book VII: The Ethics of Psychoanalysis. Ed. J. Miller, Trans. D. Porter. W. W. Norton & Company.

Lacan, J. (1998). The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XI: Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis. Ed. J. Miller and Trans. A. Sheridan. W. W. Norton & Company.

Lacan. J. (2006). The Mirror Stage as Formative of the I Function as Revealed in Psychoanalytic Experience. In B. Fink (Ed. and Trans.), Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English (pp. 75-81). Norton.

Lacan, J. (2014). The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book X: Anxiety. Ed. J. Miller and Trans. A. R. Price. Polity Press.

McGowan, T. (2007). The Real Gaze: Film Theory After Lacan. State University of New York Press.

McGowan, T. (2015). Psychoanalytic Film Theory and The Rules of the Game. Bloomsbury.

McGowan, T. (2022a). Enjoyment Right & Left. Sublation Media.

McGowan, T. (2022b, June 7). On the Paradigms of Jouissance [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LbiJusZhvuI

Metz, C. (1982). The Imaginary Signifier: Psychoanalysis and the Cinema. Indiana University Press.

Miller, J. (1978). Suture (Notes on the Logic of a Signifier). Trans. J. Rose. Screen, 18(4): 24-34.

Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Screen, 16(3): 6-18.

Nakamura, L. (2000). Race In/For Cyberspace: Identity Tourism and Racial Passing on the Internet. In D. Bell and B. M. Kennedy (Eds.), The Cybercultures Reader (pp. 712-720). Routledge.

Nakamura, L. (2020). Feeling good about feeling bad: virtuous virtual reality and the automation of racial empathy. Journal of Visual Culture, 19(1), 47-64.

Nicoll, B. (2022). Looking for the Gamic Gaze: Desire, Fantasy, and Enjoyment in Gorogoa. Games and Culture, 17(4): 528-551.

Nicoll, B. (2023a). Enjoyment with(out) exception: Sex and the unconscious drive to fail in videogame play. Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities, 28(5): 97-114.

Nicoll, B. (2023b). Enjoyment in the Anthropocene: the extimacy of ecological catastrophe in Donut County. Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory. Advance Online Publication. DOI: 0.1080/1600910X.2023.2188439

Osserman, J. (2022). Circumcision on the Couch: The Cultural, Psychological, and Gendered Dimensions of the World’s Oldest Surgery. Bloomsbury.

Pfaller, R. (2014). On the Pleasure Principle in Culture: Illusions Without Owners. Verso.

Pfaller, R. (2017). Interpassivity: The Aesthetics of Delegated Enjoyment. Edinburgh University Press.

Pluth, E. (2007). Signifiers and Acts: Freedom in Lacan’s Theory of the Subject. State University of New York Press.

Rehak, B. (2003). Playing at Being: Psychoanalysis and the Avatar. In B. Perron and M. J. P. Wolf (Eds.), The Video Game Theory Reader (pp. 103-127). Routledge.

Ruberg, B. (2019). Video Games Have Always Been Queer. New York University Press.

Shaw, A. (2014). Gaming at the Edge: Sexuality and Gender at the Margins of Gamer Culture. University of Minnesota Press.

Soler, C. (2023). Towards Identity in the Psychoanalytic Encounter: A Lacanian Perspective. Trans. C. Degril and D. Kirkman. Routledge.

Taylor, L. (2003). When Seams Fall Apart: Video Game Space and the Player. Game Studies, 3(2). https://www.gamestudies.org/0302/taylor/

Turkle, S. (1995). Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. Touchstone.

Žižek, S. (1999). The Ticklish Subject: The Absent Centre of Political Ontology. Verso.

Žižek, S. (2008a). The Sublime Object of Ideology. Verso.

Žižek, S. (2008b). The Plague of Fantasies. Verso.

Žižek, S. (2012). Less Than Nothing: Hegel and the Shadow of Dialectical Materialism. Verso.

Žižek, S. (2022). Surplus-Enjoyment: A Guide for the Non-Perplexed. Bloomsbury.