Loops, Spirals, Kennings: Metamodernism in Alan Wake 2

by Steven ConwayAbstract

This article traces Remedy Entertainment’s evolution as a noted triple-A developer of postmodern digital games (Fuchs, 2016; Stobbart, 2016), such as the Max Payne series and the original Alan Wake (Remedy Entertainment, 2010), towards a distinctly metamodern impulse, embodied in their latest release, Alan Wake 2 (Remedy Entertainment, 2023). Whilst postmodernism emphasises artifice, solipsism, and pessimism, metamodernism negotiates these tendencies with sincerity, community, and optimism. Remedy Entertainment’s aesthetic approach is mapped across three key vectors evidenced across their history. Firstly metatextuality, foregrounding relations between their games and other texts, genres, and media. Secondly, meta-mediality, integrating stylistic devices and tropes from other media, especially television, music and literature. Thirdly, metalepsis, transgressing and toying with a variety of ontological boundaries. An overview of metamodernism and Remedy Entertainment’s oeuvre situates the analysis before introducing the concept of the kenning: a figurative phrase, adapted from literature as a design principle within Alan Wake 2, emphasising circularity. The kenning is extrapolated via interrogation of character, narrative, level, mechanics and genre design. Finally, these design kennings are linked to the image of the spiral, a symbol featured throughout Remedy Entertainment’s later output, evident too in metamodernist work. We argue that if postmodern aesthetics can be conceived as loops, metamodernist practice adds three-dimensionality, and teleological momentum, embodied as kennings, becoming a spiral.

Keywords: metamodernism, postmodernism, metatextuality, meta-mediality, metalepsis, Alan Wake, Remedy Entertainment

Introduction: The Loop

Postmodernism abhors the concise lines redolent of modernism. In contrast, it obsesses over loops and circles (Altheide, 1995; Bourriaud, 2009). As a metaphysical perspective, it rejects linearity. Instead of progress, it emphasizes recurrence; instead of the momentum of certainty, it traffics in the recoil of doubt; instead of construction, it offers deconstruction; instead of newness, we find reappropriation, recycling, pastiche and irony (see Eagleton, 1996; Hassan, 1998; Hutcheon, 1988; Jameson, 1997; Lyotard, 1984). This tendency is seen across many domains, mediums, platforms and practices, but in terms of narrative design, this formal tendency lends itself towards content containing stories and characters that question themselves, their relationships and their realities. This is often embodied in protagonists either genuinely suffering, or suspected of being afflicted by mental illness (McHale, 2008). Often postmodern plots involve conspiracies and unreliable narrators (Butter & Knight, 2021). Postmodern motifs often entail multiple, fractured identities with distributed agency (Elsaesser 2021) or temporal disjunctions and loops placing the onus on the audience to untangle (Elsaesser, 2018). Acknowledging this, it becomes clear why games, and especially their digital incarnation, have been ruminated upon as innately postmodern (Aarseth, 1997), since recursive processes (Wood, 2012) and pastiches abound whatever ontological or epistemological trajectory we trace: graphics and perspective, game mechanics, animations, soundscapes, level design, quest design, narrative, player behaviours, affect, and so on. Loops are immanent to games.

Accordingly, games from the Alan Wake franchise, which include Alan Wake (Remedy Entertainment, 2010), Alan Wake’s American Nightmare (Remedy Entertainment, 2012) and Alan Wake 2 (Remedy Entertainment, 2023) are, at first glance, exemplars of such tendencies. The titular character, in 2010’s first game, is introduced as an author, also acting as the game’s narrator; it is also hinted that Wake himself is yet the creation of another mysterious character in the game, known as Thomas Zane (see Fuchs, 2013; 2016). In the midst of psychological distress, he has taken a holiday to a quiet American town, Bright Falls, at the encouragement of his partner, Alice. Soon after arriving, his larger reality begins to collapse: Alice disappears and Alan finds himself in the “dark place,” a surreal alternate dimension where art has the capacity to change reality.

Wake soon realises he is following a journey outlined in a manuscript he has written (though has no memory of writing), titled “Departure.” The pages are player collectibles found throughout the game space, and within one Wake offers a description of the dark place that also quite accurately surmises key aspects of postmodernism: “The dark place I found myself in was unlike anything I could ever have imagined; it wasn't solid, it flowed. It was conceptual and subjective.” 2012’s spin-off, Alan Wake’s American Nightmare (Remedy Entertainment) calcifies these postmodern impulses (reappropriation, pastiche, fractured identities, temporal disjunctions) in a literal time loop, as the player-character repeats the same sequence of events in a cycle to defeat their nihilistic doppelgänger, “Mr. Scratch” -- all while trying to convince other characters that Alan is not in the midst of a psychotic break.

As this article outlines, the sequel, Alan Wake 2 (Remedy Entertainment, 2023), is however, not postmodern, but a quintessentially metamodern progression of Remedy Entertainment’s design practice, as an example of “contemporary aesthetic sensibilities of resistance, sincerity, reconstruction and ethics, which have been identified as typical of metamodernism” (Backe, 2022). This is primarily evidenced across three key vectors of Remedy Entertainment’s metareferential aesthetic strategy: metatextuality, meta-mediality and metalepsis. Providing a close reading of Alan Wake 2 as a metamodern work allows us to consider Remedy Entertainment’s design ethos as an influential studio within the games industry. This framing contextualizes how the medium’s conventions are evolving in conversation with larger social, cultural and political tendencies. This movement, from postmodern loop to metamodern spiral, is brought together in the stylistic device of the “kenning,” adapted from literature to digital games, as outlined later in the article, pointing towards a larger evolution in the language of game design.

Work such as Simon Radchenko’s (ibid.; 2020), and Hans-Joachim Backe’s (2022) superb analysis of “Deathloop” (Arkane Studios Lyon, 2021) illustrate the utility of metamodernism as a hermeneutic lens to understand how games generate meaning for users not in isolation, but as social beings located in a specific historical moment. Such views are in conversation with contemporary aesthetic trends, as Jacqueline Moran comments:

The perception and meaning of a digital game depend on the existential situation of the person to whom it appears, including the bodies, technologies, skills, knowledge, literacies, history, culture, assumption, intentions and any virtual worlds subjects adopt into consciousness as part of their environment. (2023)

Before we delve into Remedy Entertainment’s history and use of metatextuality, meta-mediality and metalepsis across their catalogue, an overview of metamodernism is necessary.

Metamodernism: The Spiral

Acknowledging the eclectic and rhizomatic nature inherent to any cultural, intellectual and artistic movement, we can nonetheless step back and attempt to sketch a few larger principles underwriting modernism and postmodernism before illustrating how they find expression in metamodernism. Modernism emerged in the wake of, to name but a few key factors, accelerated industrialisation, urbanisation and nationalism. Modernist thought was bound up with the growing acceptance of scientific theories such as evolution (and later relativity), the introduction of new technologies across a host of domains, and the rise of capitalism (Eysteinsson, 2018). ”Tradition” from this perspective (such as the fixed nature of truth, Victorian morals and the virtues of imperialism, artistic movements such as naturalism and realism) were questioned as archaic, obtrusive and incompatible in the face of such change (ibid.).

Modernism was essentially a search for new standards, new metaphysical foundations capable of bearing the weight of this shift; an optimistic endeavour with constructive aims. In philosophy this is perhaps most popularly expressed in the existentialism of Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Heidegger, and then later de Beauvoir, Sartre and Camus. In terms of design, the Bauhaus school’s emphasis, epitomised in their slogan “truth to materials” (Mindrup, 2014, p. 166), is a good example of such a foundation: a focus on form following function, and a rejection of ornamentation or embellishment. In art, Cubism similarly disavowed adornment, breaking down phenomena into geometric shapes and multiple perspectives. In literature there is a search for the truth of the form, found in the Modernist slogan “a poem should not mean but be” (Beebe, 1974, p. 1075), reinforced by self-reflexivity, allusions to and modern reworkings of myth, and experimentation with language to convey the inhabitants’ varied lifeworlds (Gasiorek, 2015).

As noted within the introduction, postmodernism opposed modernism’s trajectory with a metaphysics of circularity; a pessimistic endeavour with deconstructive aims. This is not the opposite of modernism, but perhaps its logical conclusion, as Lyotard famously noted, “A work can become modern only if it is first postmodern. Postmodernism thus understood is not modernism at its end but in the nascent state and this state is constant” (1984, p. 130). Simply, for the postmodernist, the modernist search for stable foundations has concluded without success, and thus we find ourselves back at the beginning with no stable footing; no truths to situate our conduct in any field. The modernist begins their enquiry from skeptical, subjectivist or relativist positions, and, at its extreme, postmodernism pushes it to an absolute: from existentialism to nihilism. Stylistically, this finds expression in an emphasis upon artifice; a claim of arbitrariness against the rules of any field, form or content. Thus incongruity and negation are lauded in aesthetic approaches such eclecticism, pastiche, irony, kitsch and so on (Eagleton, 1996; Jameson, 1997), expressive of a crisis of identity, as Hassan notes (2003). Taylor provides an acute diagnosis:

Beginnings are always a problem, but nowhere more so than in the case of postmodernism. Postmodernism involves a thoroughgoing critique of the belief in origins and originality. For postmodernists, the notion of origin is a fiction that is first constructed and then projected back to a prelapsarian paradise in which everything is still pure and perfect... From a postmodernist perspective, nothing is original, and thus everything is always already secondary. (1992, p. 189)

Hassan’s masterful overview presents a dialectical table illustrating the movement between modernism and postmodernism. From modernism’s “purpose” we move towards postmodernism’s “play”; from “design” to “chance”; from “finished work” to “process”; from “synthesis” to “antithesis”; from “paranoia” to “schizophrenia” (1998, pp. 591-592). As Linda Hutcheon notes (1988), these are better read not as oppositions but as one residing in the other: postmodernism foregrounds the purpose of play, the antithesis within synthesis, the process of the work, and so on. Hassan further ponders, “the public world dissolves as fact and fiction blend, history becomes derealized by media into a happening… what construction lies beyond, behind, within that construction?” (1998, p. 593).

Enter metamodernism as a tentative answer to Hassan’s question. Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker summarise:

Ontologically, metamodernism oscillates between the modern and the postmodern. It oscillates between a modern enthusiasm and a postmodern irony, between hope and melancholy, between naïveté and knowingness, empathy and apathy, unity and plurality, totality and fragmentation, purity and ambiguity. Indeed, by oscillating to and fro or back and forth, the metamodern negotiates between the modern and the postmodern. One should be careful not to think of this oscillation as a balance however; rather, it is a pendulum swinging between 2, 3, 5, 10, innumerable poles. Each time the metamodern enthusiasm swings toward fanaticism, gravity pulls it back toward irony; the moment its irony sways toward apathy, gravity pulls it back toward enthusiasm. (2010, pp. 5-6)

In a later article, Vermeulen and van den Akker explicitly cite metamodernism as an example of Raymond Williams’ “structure of feeling” (1977), noting “metamodernism is a structure of feeling, a mood, if you will, an attitude ‘dependent’… on the overall state of the organism, its level of energy” (Vermeulen & van den Akker, 2015, emphasis in original). Turning specifically to design, we may better conceive of Williams’ concept not as a structure of feeling, but more adroitly as a feeling that structures; a socio-cultural, political mood which influences design sensibilities and aesthetic choices. Radchenko concisely outlines in an analysis of Death Stranding (Kojima Productions, 2019), “the metamodern feeling might be outlined as a struggle to [re]construct… This [re]construction cannot be done by ironic or self-sufficient postmodern heroes that desire to stay alone and avoid being close to one another” (2023, p. 5). Instead, the metamodern structure of feeling emphasises community, “through the new level of emotionality and sincerity” (ibid.) seeking construction, as “destructive postmodernism left the social and cultural horizons empty, there is a need to [re]construct, [re]invent a new truth, new sincerity, new sociality, and new systems. It is essential to share and belong to something” (ibid., p. 6). We now provide an overview of Remedy Entertainment’s history as a studio, to better contextualise their design ethos.

Remedy’s Metamodern Metamorphosis

Metatextuality, as introduced in Gerard Genette’s work, is a type of “textual transcendence” which “unites a given text to another, of which it speaks without necessarily citing it… in fact sometimes without naming it” (1997, p. 4). Whilst related to Genette’s other categories of textuality such as intertextuality, the key difference is in the explicitness of the reference, and intention: for example intertextuality directly emulates, quotes or summons, whilst metatextuality infers the existence of other texts the reader should be aware of, and often provides critique, even on itself as an example of the form or genre it refers to (ibid.). A classic example of metatextuality, occurring throughout the Alan Wake series, is the detailing, subversion and sometimes parody of genre tropes, as detailed further on. Meanwhile there also exist many intertextual moments within the series, such as in the original game, where Wake repeatedly refers to Stephen King’s body of work, and even its cinematic adaptations (such as a cutscene aping the famous “Here’s Johnny!” moment from Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of King’s The Shining (1980)).

Building upon influential computer scientist Alan Kay’s view of the “computer as a simulation machine for old media” (Manovich, 2005), Lev Manovich articulates meta-media:

What is crucial is that the computer’s simulational role is as revolutionary as its other roles. Most software tools for media creation and manipulation do not simply simulate old media interfaces… but also allow for new types of operations on the media content. In other words, these tools carry the potential to transform media into meta-media… This is not accidental. The logic of meta-media fits well with other key aesthetic paradigms of today -- the remixing of previous cultural forms of a given media (most visible in music, architecture, design, and fashion), and a second type of remixing -- that of national cultural traditions now submerged into the medium of globalization… Meta-media then can be thought alongside these two types of remixing as a third type: the remixing of interfaces of various cultural forms and of new software techniques -- in short, the remix of culture and computers. (ibid.)

Of course, as Manovich further highlighted in The Language of New Media (2002), and Fuchs and Thoss discuss within their edited collection on intermediality in games (2019), the very nature of the medium means that “digital games are enmeshed in a network of media that shape one another” and “are, moreover, often part of (if not the foundations of) larger transmedia universes” (ibid., pp .2-3).

Remedy Entertainment’s Max Payne series, beginning in 2001, established their signature as a developer: metatextual, meta-medial and metaleptic gameworlds narrated by the protagonist. The Max Payne series is built around game mechanics focused on manipulation of time and space, using an in-house game engine taking advantage of the latest graphical rendering technologies [1]. In both Max Payne (Remedy Entertainment, 2001) and Max Payne 2: The Fall of Max Payne (ibid., 2003), meta-media and metatextuality run rife: between “chapters” (i.e. levels), graphical panels are used to tell a film noir, "hardboiled" detective story in the style of a comic book, weaving in numerous aspects of Norse mythology [3]. This mechanic is triggered by the player as a limited “adrenaline” resource, slowing down everything in the environment (enemies, sound effects, debris and so on) whilst they maintain real-time control of their aiming reticule, to place precise shots and dodge bullets.

The series would also solidify their use of metalepsis, defined by Genette as:

[A] shifting but sacred frontier between two worlds, the world in which one tells, the world of which one tells… The most troubling thing about metalepsis indeed lies in this unacceptable and insistent hypothesis, that the extradiegetic is perhaps always diegetic, and that the narrator and his narratees -- you and I -- perhaps belong to some narrative. ([1972] 1980, p. 236)

This movement across ontological planes by the developers, the characters, the plot and so on, happens in numerous instances and in many directions. Firstly, the lead writer of Max Payne, Sam Lake (an anglicization of his Finnish name, Sami Järvi, later becoming Remedy’s creative director) provided his face and clothes for the protagonist’s in-game model, whilst his mother was used as the face for main antagonist Nicole Horne. Marko Saaresto also appears in-game as major character Vladimir Lem (going on to become the main antagonist of Max Payne 2: The Fall of Max Payne). Saaresto is founder of Finnish rock band “Poets of the Fall,” whose music features heavily in Remedy Entertainment’s output from 2003 onwards. Secondly, if the game is completed on its hardest difficulty, a secret room becomes accessible. This area contains a spinning Remedy Entertainment logo, is adorned with multiple images of the studio’s staff, and contains photos across the production of the game, such as location shots inspiring game levels [4]. Finally, in an acutely postmodern moment, a narrative sequence takes place where Payne realizes that he is actually in a videogame, and ruminates on the horrifying nature of being stuck in its gameplay loop.

Max Payne 2: The Fall of Max Payne furthers these metatextual, metaleptic and meta-medial trajectories. For example the traditional “game over” screen takes on the voice of the protagonist: instead of “game over,” the screen states “death kept writing me valentines in blood,” and the player is able to select either “I was afraid to go on” to quit the game, or “but I refused to give in. I had to continue” to load a checkpoint. The game also introduced what would become another meta-medial hallmark of Remedy Entertainment’s games: television shows made by the developers, each offering parodic, ironic, or surreal commentaries on the game itself. The player could view these within the game by activating television sets found across levels.

2010’s Alan Wake also presents a metaleptic and metatextual core draped in postmodern sentiment. In many ways the game’s narrative can be interpreted as autofiction based upon Remedy Entertainment’s own trajectory as a studio [5]. Within the game, Max Payne’s character is transmogrified into a character named Alex Casey, the protagonist of a highly successful series of hardboiled detective novels written by Wake. This spurs writer’s block and ennui, as Wake agonises over his status as an artist. A therapeutic vacation to Bright Falls is initiated by his partner, Alice, serving as the game’s main setting. Quickly finding himself stuck in the dark place, a sinister version of Bright Falls, Wake employs flashlight and gun to fight “the taken,” ghostly imitations of town residents and objects such as barrels and mining carts, infected by the “dark presence” hunting him. Wake acts as narrator, providing metatextual ruminations on horror, crime and thriller motifs in deliberately ham-fisted prose, highlighting Wake’s obvious limitations as a writer and the absurdity of his angst regarding his status as a serious artist. Beyond books, magazine articles, television and radio shows accessible within the game, the format of Alan Wake is explicitly meta-medial, imitating a television serial containing six “episodes,” i.e. discrete quest lines. Each is replete with its own outro, featuring an original musical track reflecting the episode’s themes, followed by a “Previously On…” bumper.

Remedy Gets Weird

Alan Wake also represents Remedy Entertainment’s first sustained foray into what would become its staple genre, weird fiction. This style can be traced back to gothic literature, though its more modern elements find expression in writers such as HP Lovecraft and Edgar Allan Poe. It is described by weird fiction author China Miéville as an “obsession with numinosity under the everyday,” as it “punctures the supposed membrane separating off the sublime, and allows swillage of that awe and horror from "beyond" back into the everyday -- into angles, bushes, the touch of strange limbs, noises, etc. The weird is a radicalized sublime backwash” (2009, pp. 510-511) conveying the “burgeoning sense that there is no stable status quo but a horror underlying the everyday, the global and absolute catastrophe implying poisonous totality” (ibid., p. 513). Weird fiction thrives upon juxtaposition, the uncanny and the sublime, often in the form of intrusions upon the everyday by inexplicable, unknowable powers; a kind of metalepsis, a monstrous collision of ontological planes, as Fuchs has ruminated upon (2016). Mark Frost and David Lynch’s Twin Peaks series is a clear example in television and has deeply influenced the Alan Wake series, from its setting in a rural Washington town, to key characters and locations.

Remedy Entertainment once again weave Norse mythology and Slavic folklore (most notably the figure of Baba Yaga (see Stobbart, 2016)) into their design. In accord with their weird fiction predilection, fantastical figures such as the Norse gods Odin and Thor live, though as retired members of a rock band residing in a nursing home; a typewriter has the power to recreate reality, whilst a humble flashlight and, later, disconnected light switch (known as “the clicker”) become the ultimate weapons in the fight against evil. Two years later, Remedy Entertainment would release a spin-off, Alan Wake’s American Nightmare, narratively framed as an episode of “Night Springs” (i.e. the opposite of Bright Falls), a television show watchable within the original game, written by Wake. Night Springs metatextually positions itself alongside weird fiction television serials, most notably The Twilight Zone.

2016’s Quantum Break (Remedy Entertainment) incorporated a live-action television show into its structure, as key narrative choices made by the player are followed by a 20-plus minute live-action episode outlining the impact of the choice. Shawn Ashmore stars as the protagonist, with Aidan Gillen and the late Lance Reddick serving as antagonists. Control followed in 2019 (ibid.), positioning the player as an agent for the “Federal Bureau of Control” (FBC), a secret agency within the United States government tasked with investigating and restraining paranormal forces. Following Remedy Entertainment’s weird fiction proclivities, the game is set in an eerily empty office space. Malevolent paranormal forces, embodied in “Objects of Power,” are often surprisingly quotidian in appearance, such as a floppy disk, jukebox or film camera. Much like Alan Wake, Control pivots around a fundamental corruption of reality, and it is once more the player’s task to restore normality. Once again the protagonist, Jesse Faden, narrates the plot, though unlike Alan Wake, cannot directly alter reality.

An expansion for Control directly ties these universes together, initiating the ”Remedy Connected Universe” (RCU). This DLC package is titled AWE ((ibid., 2020) a Bureau acronym for “Altered World Event,” also “Alan Wake Experience”), the expansion has Alan Wake contact Jesse Faden. Wake advises Jesse to find and confront Dr. Hartman, a sinister psychotherapist from the original Alan Wake, monstrously transformed by the dark presence and unleashed within the FBC’s headquarters. Now we understand Remedy Entertainment’s historical, multifarious use of metalepsis, meta-mediality and metatextuality, we provide a brief overview of “meta” research within game studies.

Metaization in Game Studies

Since play itself is an act of metacommunication (as Gregory Bateson famously noted (1979), even dogs and monkeys playfight, illustrating awareness of the gap between action and signification), there is a long history of discussion focusing upon the precise nature of the meta in game studies. Building upon Bateson and others, Neitzel points out even single player computer games contain metacommunication since they “set up a fictional play situation in which metacommunication from the fictional level to the player world can take place” (2008, p. 292), positioning metacommunication as innate to the fluidity and penetrability of magic circles. Krampe et al. (2022) summarise much work on the metareferential capacity of game interfaces (and indeed, gameworlds as interfaces, as Jørgensen’s work (2013) points out), highlighting the multifarious use of hardware and software to generate ontological intrusions, transgressions and disruptions interwoven with the narrative and mechanics of (especially independent) digital games, towards particular aesthetic goals. Similarly, Waszkiewicz’s (2024) recent contribution ponders the relation between ontology and meta aesthetics. Defining metareferentiality as "a form of self-referentiality of media through which a text highlights its existence and status by commenting on its own characteristics, production methods, or elements” (2024, p. 3), Waszkiewicz ultimately advocates understanding a variety of meta tactics as “ontological reframing,” a “shift in perception between a character seen as a natural (but fictional) person and a character-as-a-pseudonym,” circumventing any distinction between fiction, non-fiction, claims of the “real” etc.

Schmidt (2021) points towards the confluence between metareferentiality and the palimpsest, describing how many games gesture for the player to impress their literacy and history upon the play experience; weaving together the design’s intertextual, intermedial, transmedial features, “assembling textual predecessors… providing a second textual level,” often reshaping the boundaries of the magic circle of play such that other objects, geographies, histories, are brought inside the diegesis of the gameworld. Similarly, Kielich and Hall’s (2024) brilliant analysis of the Metal Gear Solid series illustrates the ways many games demand the user write over, stitch together, and reconfigure the play experience in dialogue with the developer.

Offering a practitioner’s perspective, Stefano Gualeni (2016) details the use of self-reflexivity in digital game design, urging a phenomenological understanding sensitive to media forms. Gualeni advocates leveraging the affordances of specific technologies (and, therefore, their unique techno-logics) to provoke thinking. Keeping this in mind, we now turn to Remedy’s latest implementation of some of these vectors as part of their metamodernist turn within Alan Wake 2, epitomised in a meta-medial, metatextual adaptation of the literary concept of the kenning into game design. In Remedy Entertainment’s hands, the kenning operates not as postmodern loop, but metamodern spiral.

Kenning as Meta-Design

Encompassing aspects of metalepsis, metatextuality, and meta-mediality, Krampe et al. define metareferentiality as “self-reflexive elements that a text or artifact may use to comment on itself or on the media system it is embedded in… the metareferential artifact encourages reflection in its recipients and draws their attention to its mediality and representationality” (2022, p. 735). A kenning is a compound figure of speech delighting in its highly figurative nature; its status as a semantic puzzle. In a poetic manner, it asks the user to focus upon its configuration, purposeful combination of words and structure to generate meaning. It has significant overlaps with metareference as a phenomenon drawing attention to its status as playful linguistic representation. In his classic analysis of Beowulf, Friedrich Klaeber defines kennings as “those picturesque circumlocutory words and phrases… which, emphasizing a certain quality of a person or thing, are used in place of the plain, abstract designation” (1922, p. 64). It is rife in Old Norse-Icelandic and Old English poetry and sagas (e.g. “whale-path” means sea; “battle-sweat” means blood; “water-ropes” mean icicles), but survives in everyday language across innumerable phrases, such as “ankle-biter” (child), “motor-mouth” (someone who talks a lot), “sky-scraper” (a very tall building) and so on. Much like game loops, kennings operate cyclically, exposing the user to new features and ways of interpreting the referent each time that phenomenon is invoked. For example, in Beowulf, the word “sword” has many kennings, from “light-of-battle” and “corpse-candle” to “the harsh swallower of the board of defence” and so on [6].

Kennings are polysemic and periphrastic, placing the onus upon the audience to do the work, constantly circling back to solve the gap between the phrase and its referent. As often is the case with metareferential aesthetics, kennings emerge at a certain point in the maturity of a language, as innately intertextual, metatextual phenomena. The medium’s conventions and parameters become objects of play and manipulation for the communicator. It is no coincidence that the term “kenning” shares an etymological heritage with the word “cunning,” connoting not only skill and special knowledge, but also trickery and deceit. These are also essential aspects of Remedy’s oeuvre from Max Payne onwards: conspiracies, betrayals, hidden dimensions, metaleptic intrusions and so on. In addition, the words “canny” and “uncanny” are derived from kenning, linking well with the studio’s penchant for weird fiction. In sum, there are three key aspects of kennings: they are compound, periphrastic and polysemic. As design gestures, they operate in loops -- cycling back to the same essential phenomenon time and again, yet with a new twist or emphasis. With each loop, they abound with fresh meaning for the reader. Expanding this understanding of linguistic kennings to the language of game design, we can identify a design motif in Alan Wake 2’s character, level and narrative design described below as “ludic kennings.”

The Role-Shifter

As befits Remedy Entertainment’s meta-medial, metatextual leanings across diverse ontological and epistemological planes, Alan Wake 2 delights in looping back to the same phenomenon, yet with a new feature or inflection. For much of the game, the player controls two characters: Alan Wake, and, new to the series, an FBI profiler named Saga Anderson [7], who Wake has partially written into this reality. Saga arrives at Bright Falls with her partner, Alex Casey (sharing his name with the protagonist of Alan Wake’s successful book series), to investigate a ritualistic homicide.

This murder in fact serves as the opening level of the game, where the player controls a confused, naked man surfacing from Cauldron Lake, stumbling through the forest, encountering attackers in deer masks. The victim turns out to be Nightingale, an FBI agent and antagonist from the first game. He has returned as one of the taken, i.e. infused by the dark presence, and though ritually murdered, re-emerges as the first boss fight of the game for Saga Anderson. This is the initial ludic kenning: the player cycling as Nightingale, as Saga, as Wake. Exploring the same base phenomenon (Cauldron Lake, Bright Falls, the dark place and so on) from multiple perspectives, this is not simply looped, but whorled, each character offering vital standpoints for the player to comprehend and progress through the narrative to its centre, the literal writer’s room described in the next section, serving as the final location of the game.

This use of the ludic kenning not simply as static, self-referential loop, but kinetic spiral making new connections, emphasises one of the key aspects of metamodernism distinguishing it from postmodernism: problems are not solvable by a singular agency, especially not the cynical postmodern hero, but by an emotionally open, sincere community of actors (Radchenko, 2023). This tenet operates across two domains: firstly, the player’s sincere commitment to solving the narrative through appropriate use of the stable of characters, obeying the rules of the game to progress. Secondly, the evolving relationships between the characters themselves. For example, when Wake first reappears in Bright Falls, he is taken into custody and treated with suspicion by Saga and her partner. As the game progresses, Saga and Wake enter earnest, open collaboration, leading towards a solution requiring absolute trust in one another: Saga must murder Wake, according to his exact instructions.

The (Uni)Verse-Shaper

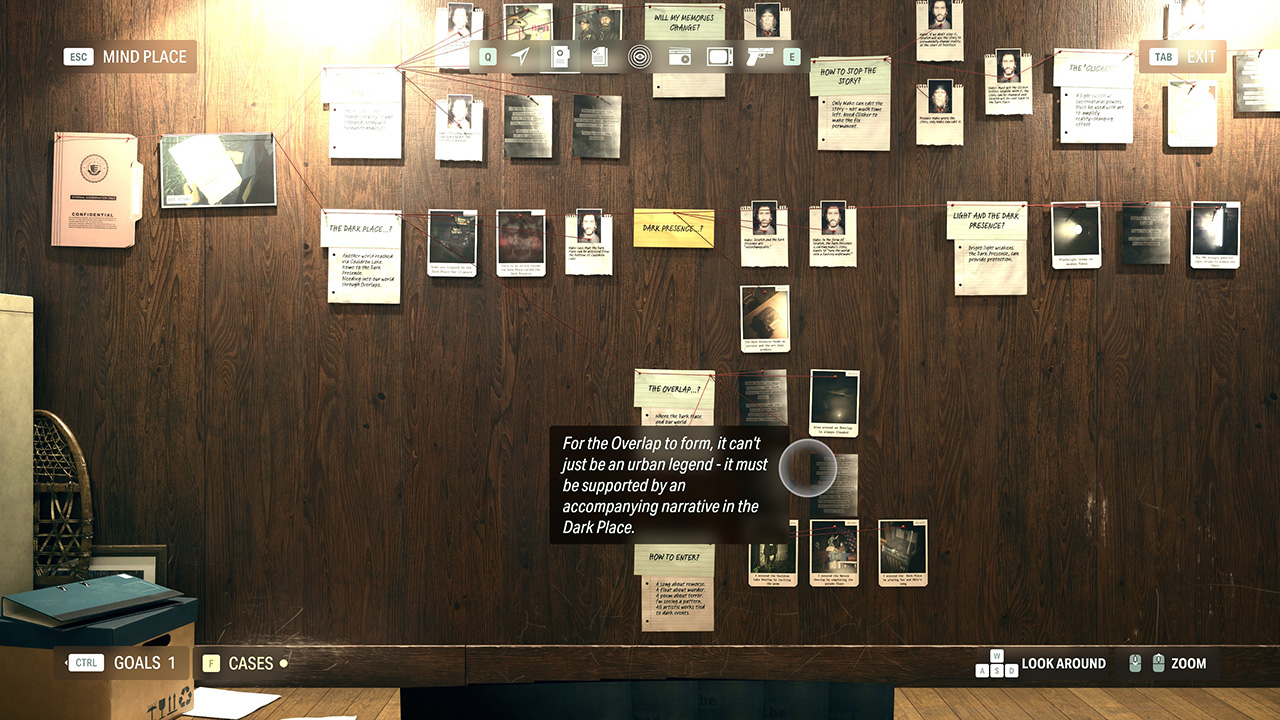

Figure 1. Saga Anderson's Case Board. Click image to enlarge.

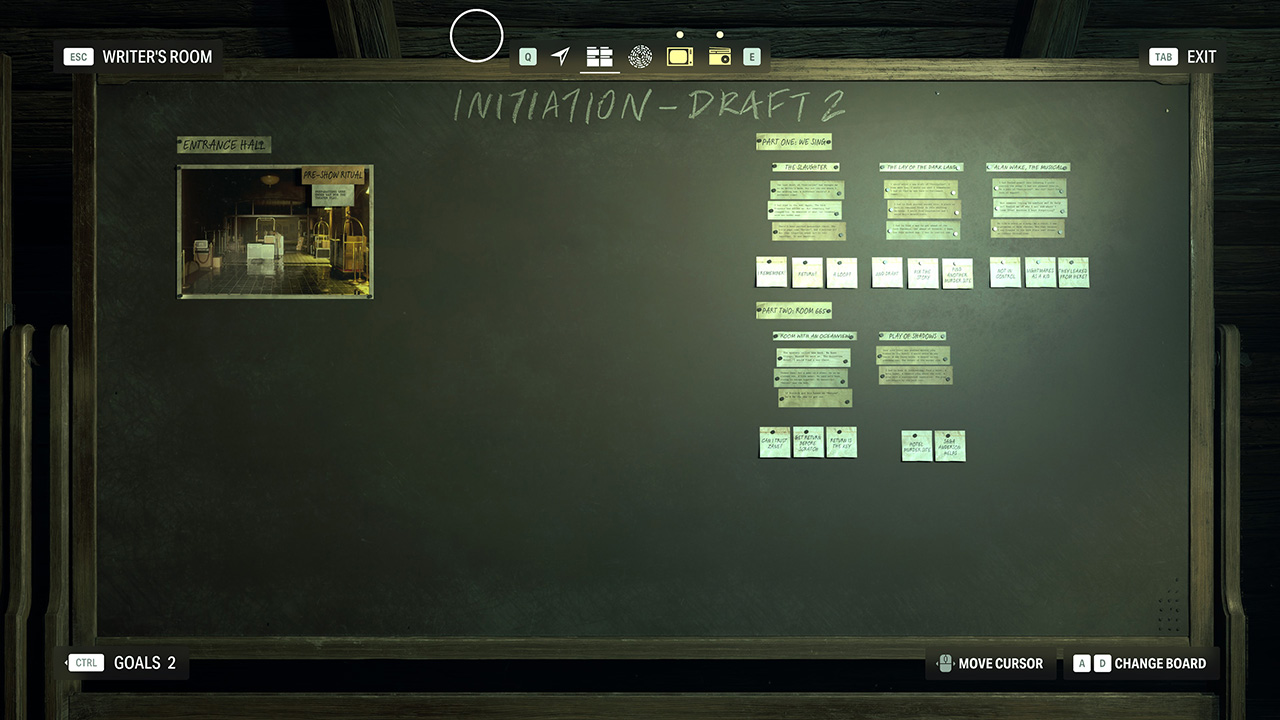

Following the opening level, the player-character can shift between two domains at the press of a button: Saga travels to Bright Falls, and other nearby areas, but can also enter her “mind place” at will. This is an impromptu office within a cabin, dominated by a case board wall. This board, an agglomeration of photographs and notes stuck to the wall, is used to map out the various aspects of the case files Saga is investigating; as new clues are found, the player-character links them to key events, or pins up new events, connected by a thin piece of red string. Similarly, Alan can explore the dark place he is trapped within, a metropolitan space reminiscent of New York City, and shift to the writer’s room, a minimal workspace reminiscent of the Bird Leg Cabin [8] Alan and his partner visited in the first game. This darkened room contains a desk with a typewriter, and other useful items, but is dominated by a chalkboard. Upon this, we find Alan’s plot points for his new manuscript, “Initiation,” and later, “Return.”

Figure 2. Alan Wake's Plot Board. Click image to enlarge.

The player interacts with the chalkboard to rewrite the story, change the plot elements within specific locations, thereby changing routes, access points, environmental hazards, and so on. For example, early in the game Caldera Station is pinned on the chalkboard as a key location, a setting from an Alex Casey novel (Casey appears in flashes, narrating the plot). This is a subway environment within the dark place, and initially the player-character is unable to proceed past an abandoned, unpowered train. However, moving back into the writer’s room, Alan notes a plot element, “missing FBI agent,” has emerged. Attaching it to Caldera Station on the board, the player-character now switches back to the subway. A typewriter sound is triggered as Alan writes the new plot into the location, and the environment suddenly shifts: the lighting undergoes a drastic change, and the train tunnel is now clear.

The system is a quite literal embodiment of Linda Hutcheon’s notion of the “palimpsestuous” (2006), “a derivation that is not derivative -- a work that is second without being secondary. It is its own palimpsestic thing” (ibid., p. 9). However, whilst Hutcheon focuses upon adaptation and the intertext, the palimpsestuous is reworked here as ludic kenning -- as inflection and refraction of the very same phenomenon, precisely a “derivation that is not derivative” (ibid.). Later, more plot elements are found, and can be swapped between, such as “Summoning Ritual” or “Murder Cult.” The text operates as palimpsestuous kenning, an intratextual, intertextual and metatextual puzzle for the user’s rumination, its constant metareferentiality demanding re-inscription.

Kennings are extrapolated into level design: the train of the Missing FBI Agent is also the tracks of the Murder Cult, is also the Summoning Ritual rails, and so on across the game. This is also evident in the player-character’s use of a lamp which Alan carries with him: the player uses it to alternately absorb and give luminescence to lightbulbs across levels, changing the immediate geometry, hazards, items and so on. The kenning transmutes into a spatio-temporal phenomenon, and the onus is upon the player to be canny and solve the puzzle; to direct Alan to write the appropriate kenning, to change the environment into its most apt form for the story, characters and genre.

The Phantom-Person(a)

Each major character, and many minor, in the Remedy Connected Universe exist in kenning format: as metaleptic and metatextual puzzles providing new ways of understanding their various aspects, plot, and cross-world connections. Alan Wake’s likeness, as portrayed by Ilkka Villi and voiced by Matthew Porretta, is also used for other characters, such as series antagonist “Mr. Scratch.” Mr. Door, an enigmatic character, first appears as a talk show host interviewing Alan about his book, “Initiation.” Mr. Door’s full name is Warlin Door, evoking movement between places (whirling door), i.e. metaleptic transgression of boundaries. It is also heavily hinted that Mr. Door is Martin Hatch from Quantum Break ("Warlin" is close to "Martin" flipped upside down; Hatch instead of Door), and as Óðr ("divine inspiration" (Polomé, 1972)) from Norse mythology; a mysterious figure married to the goddess Freyja. Finally, it is also suggested in documents found within the game that Door is the father of deuteragonist Saga Anderson, and once-husband of her absent mother, Freya (again, linking the character to the figure of Óðr).

Saga’s partner, Alex Casey, is an FBI agent within Bright Falls, but also the fictional hardboiled detective of Alan Wake’s novels, appearing to Wake in the dark place as such; he also of course is a meta fictional copy of Max Payne in appearance, voice, and vocation. Tim Breaker, sheriff of Bright Falls, is played by actor Shawn Ashmore, who also played Jack Joyce, protagonist of Quantum Break. He is frequently found within the dark place, managing his own palimpsest, plotting the timeline of the game’s narrative and characters on a whiteboard. Jesse Faden, the protagonist of Control, is played by the same actor who portrays Beth Wilder in Quantum Break, and makes appearances on Sheriff Breaker’s whiteboard and later on an in-game television as she searches for Alan Wake.

As noted Barbara Jagger from the original game is also Baba Yaga from Eastern European folklore (Stobbart, 2016), whilst retired rock stars Odin and Tor Anderson are also hinted to be Norse Gods Odin and Thor. Saga Anderson is an FBI agent, but it is later revealed, also someone with paranormal abilities (a "parautilitarian"). The name, Saga, etymologically finds its roots in Old Norse, the verb sjá, "to see," evolving to "seeress" (someone who practices divination), and has come to be associated with the telling of stories and fables. In Norse mythology the goddess, Sága, sits at Sökkvabekkr ("sunken-bank") drinking from a cup of gold with Odin; she is associated with water streams, memory, history and enigma (and, indeed, Saga learns over the course of the game that the character Odin is her long-lost grandfather). It is no coincidence Saga Anderson begins the game at the sunken bank of Lake Cauldron, finding the mysterious Alan Wake, suddenly washed upon the shore.

This invocation of classical myth, so popular within modernism, so critiqued, parodied and ridiculed by postmodernism, is reconciled by metamodernism as mythopoetic kennings, “multidimensional/polyphasic resources for determining existential standpoints… Such “orientation points” would not be dogmatic, non-falsifiable truths, but rather myths are… fictions recognized helping us to imagine our participation in our life worlds alternatively and critically” (Doty, 2003, p. 145). Rather than the “flat” characters often encountered in postmodernism (Fokkema, 1991), these metamodern characters are coiled into a helix structure, allowing the player access from multiple perspectives to deepen empathy and understanding. Even characters such as Alex Casey, whose very ontological status is at question (does he have autonomous existence? Is he the fictional detective of Wake’s imagination? Is he an actor playing Alex Casey?) could be used simply for postmodern ridicule and metaleptic humour. Instead, Casey is given a depth and multivocality. He is portrayed as Saga’s supportive partner detective, a heartbroken divorcee, budding romantic interest for another character in the game, and finally as Mr. Scratch, becoming a crucial aspect of the game’s ending. His ambiguous creation by Wake’s typewriter does not diminish him to a postmodern punchline, but is treated as one aspect of a fuller, complex metamodern existence.

The Mind-Maze-Mandala

The titles of Wake’s chalkboard drafts in his writer’s room are deeply intertextual and metatextual. The drafts assume the player is aware of the Hero’s Journey plot structure as described by Joseph Campbell (1968). Campbell’s formula is very popular within film and games, as Moran outlines (2023) and Stobbart (2016) applies fruitfully in a narrative explication of the original Alan Wake. The model is based upon C.G. Jung’s analytical psychology, a theoretical framework evident within the Alan Wake series’ notions of the taken, the dark presence, the psychotherapist Dr. Hartman and so on (Garcia, 2022). Indeed, Jung’s concepts of “individuation,” the “collective unconscious’ and “archetypes” such as the “shadow” are specifically highlighted and defined in Control, and it is hinted in the game that Jung himself has, or had, some kind of relationship with the Federal Bureau of Control.

Further, across a number of Remedy’s releases, a spiral symbol can be found on doors. These doors, such as in Control and the Alan Wake series, are always locked. It is finally revealed within Alan Wake 2 that behind the door is Wake’s writer’s room. The symbol of the spiral is enormously important within analytical psychology. In an early series of lectures, Jung emphasises the spiral is a kind of mandala (interestingly for game studies, this is Sanskrit for “magic circle,” though not Huizinga’s kind), a symbol of psychological growth and maturation. Jung articulates in a lecture from 1930:

[T]he spiral, showing the attempt of the unconscious to penetrate the conscious. In the progress of the dreams, you really see that attempt to impress the conscious with the unconscious point of view. The final fact would be the complete blending of the unconscious attempt with the actual quality of consciousness. In colour that would mean the mixture or the sum of all colours, which would be pure white. (1984, pp. 524-525)

Russack notes the appearance of the symbol across historical periods and cultures, used as a symbol of healing, protection (1984), and a cue for the dreamer to act. Jung goes on to explicitly link the symbol to movement and discovery, as a kind of labyrinth structure:

The way to the goal seems chaotic and interminable at first, and only gradually do the signs increase that it is leading anywhere. The way is not straight but appears to go round in circles. More accurate knowledge has proved it to go in spirals: the dream-motifs always return after certain intervals to definite forms, whose characteristic it is to define a centre. And as a matter of fact the whole process revolves about a central point or some arrangement round a centre, which may in certain circumstances appear even in the initial dreams. As manifestations of unconscious processes the dreams rotate or circumambulate round the centre, drawing closer to it as the amplifications increase in distinctness and in scope. (Jung, 2014, p. 28)

As noted, this obsession with loops and circles is essential to the game medium, and spatially is often expressed as a labyrinth structure. As Rolf Nohr outlines the “labyrinth is a central metaphor of the game… It limits the subject and is a training tool” (2021, p. 134), going on:

The labyrinth organises the player’s action according to a purpose. It directs the path and the action towards a single meaning: the boss fight against the Minotaur at the end of the path. In addition, the labyrinth evokes a clear concept of the subject. The subject is controlled by the labyrinth -- or processed by the topography of it. And the pure clarity of the labyrinth (its topology as well as its architecture) reflects the hidden processing, the calculating, and also the algorithm working ‘behind’ the ‘interface’ of the game labyrinth. (ibid., p. 136)

Similar to Jung’s earlier quote, an essential phenomenological point Nohr makes, regarding player experience, is how the labyrinth, though unicursal (i.e. having a single correct path) appears multicursal to the player (i.e. having many routes and possibilities), also noted by Golding as the view “from below” (2013, p. 117). This is also expressed in a song written for the game, playing at the end of Saga’s first chapter, titled "Follow You Into The Dark.” This also hints at another key point of Nohr’s, and before him, Hans-Georg Gadamer’s emphasis on the game playing the player (2004), rather than the other way around: the subject is not the primary agency, but instead processed by the game, according to its rules and parameters. The player, Alan, Saga, are never in control, they simply play their role. As Fuchs notes, in 2010’s Alan Wake, this is viewed with postmodern pessimism, “This is what Alan’s horror is about… Through repeated metaleptic transgressions, Alan Wake is not only likened to the author and creator of his life… but also to the gamer sitting in front of the monitor… trying to escape everyday reality” (2016, p. 102). However, as we now turn to, Alan Wake 2’s metamodern ethos presents a more optimistic view.

The Prose-Plot-Pattern

One of the many paradoxes of postmodernism is its dismissal of the author and de-mythologizing of originality (championing intertextuality, polysemy, pluralism, collage etc.), whilst contemporaneously emphasizing the author’s presence: to draw attention to one’s authorship as a limiting factor, the artifice and bias of the design, most evident in styles such as irony, cynicism, pastiche, parody and so on. Metamodernism’s reconciliation leans into this paradox, acknowledging the limitations of the authorial voice, whilst also pointing towards the value of its claims as context sensitive. Storm clarifies, “There are no eternal facts. Neither are there brute facts… facts have a ‘half-life’ like radioactive materials, giving off flashes of energy before they decay… Instead of choosing between false certainty and incomplete skepticism, we need emancipatory, humble, Zetetic knowledge” (2021, pp. 222-223).

Whilst postmodernism often used genre as a tool for deconstruction, to pick apart authorial conceit, to dispel the illusion produced by craft, to ironically dance on the parameters of a design, metamodernism offers a markedly different perspective. Metamodernism metatextually, metaleptically and meta-medially plays with genre. It seeks out a genre’s limitations, yet still respects and works within them. Towards the end of the game, Saga, Wake and residents of Bright Falls collaborate to banish the dark presence, which as noted earlier, inhabits Alex Casey. Wake outlines the need to satisfy genre tropes to succeed. Wake specifies the story they are in, his draft of “Return,” is a horror story. He explains they must “earn” the ending according to genre parameters, “there are only victims, and monsters… If there is a hero, they ultimately pay a heavy price,” pointing out Saga is the protagonist.

Saga responds, “I’ve been through hell to be here. And this is my life. It feels ‘earned’ to me that I rise above the story and be there to create the ending.” She acknowledges “the more people we save, the greater the cost, and the hero must pay the price.” They devise a plan to draw the dark presence out of Casey using Wake’s clicker, so Wake can absorb the darkness into himself. As the darkness enters Wake, he provides a monologue evocative of postmodern terror, “What if there is nothing waiting to be revealed? The play of shadows fooled us all… Darkness not as a monster, but as emptiness. We are none the wiser. No answers. No truths.” Saga fires a bullet of light into Wake’s head, ending the darkness, sacrificing Wake, satiating genre expectations. Konstantinou speaks of this kind of self-aware, yet sincere stylistic device as “credulous metafiction,” an evolution of postmodern metafiction using the characters’ self-awareness “not to cultivate incredulity or irony but rather to foster faith, conviction, immersion and emotional connection” (2017, p. 93).

Conclusion: Not A Loop, A Spiral

The game credits roll. Suddenly Alice, Alan Wake’s missing partner from the first game, appears as a video recording. She reveals an alliance with the FBC from Control, and advises in a metareferential tone pointing towards the goal of any Hero’s Journey, “the only way out of your loop is destruction or ascension.” At this point, Alan has already been shot in the head by Saga. Yet he suddenly awakes from his apparent sacrifice: “It’s not a loop… It’s a spiral” he gasps in the game’s last line.

Wake now realises: this is not the two-dimensional loop of postmodernism, but the spiral of metamodernism. It has a teleological impulse, a three-dimensionality, momentum upwards. Lyotard outlines, “[M]odernity, in whatever age it appears, cannot exist without a shattering of belief and without the discovery of the ‘lack of reality’ of reality, together with the invention of other realities” (1984, p. 77). However, instead of “what Nietzsche calls nihilism” Lyotard sees “the Kantian theme of the sublime” (ibid.), a transcendent impulse. Metamodernism does not follow the straight lines of modernism, but neither does it embrace the circularity of postmodernism. Instead, it is a fusion of both, acknowledging the need to move forwards, upwards, whilst often correcting itself by looking backwards, downwards; instead of a loop, a spiral. Modernism demanded originality. Postmodernism bemoaned the impossibility of originality. Metamodernism holds both in tension: originality lies in reconstruction. In their discussion of metamodernism, Storm too uses this geometric metaphor:

The preceding system is not only cancelled out but is also assimilated into the new system… It therefore preserves in its movement the contradictions of various inherent negativities… passing over its starting point while perpetually ascending. It is a return, but a return in a higher key… Rather than running in circles, we need to spiral upward. (2021, p. 6)

Pastiche, collage, kitsch, irony, eclecticism -- all noted as hallmarks of postmodernism, find a place in Alan Wake 2’s use of metatextuality, meta-mediality and metalepsis. However, they are put to fundamentally different uses. Between the bold, but naïve plea of the modernist, and critical, yet caustic touch of the postmodernist, the metamodernist uses such stylistic devices to weave together a sincere, impassioned claim: forward, together. Appropriately, Alan Wake 2’s final kenning exists at the end of the game, as “The Final Draft,” a new game mode available after completion. The player is now tasked quite literally to treat the game as palimpsestuous kenning, writing over it with full knowledge of the various loops and trajectories of the plots and characters within. They are tasked with seeking reconstruction, not of the same, but something better for not only himself (as is often the case with postmodern anti-heroes), but for the entire community of characters.

The first playthrough ends with Saga shooting Alan through the head with a bullet made of light. “The Final Draft” begins with the bullet entering Alan’s head, as he narrates:

Back to the beginning, with the memory of this past loop already fading fast. But while it lingers, I know there is hope. We are not doomed to repeat our failures in an eternal loop. This is a spiral. A fictional poet once said: beyond the shadow you settle for, there is a miracle, illuminated. I will not settle for a shadow. I will find the miracle. Through the night. It’s not just victims and monsters. I see now there are heroes as well. We can find our way through the darkness. We will break through the surface. We will emerge into the light. (Remedy Entertainment, 2023)

Perhaps there is no better description of both metamodernism’s intentions, and Remedy Entertainment’s evolving design ethos. As noted, ludic kennings, as metareferential devices, require a high degree of fluency on behalf of all parties in the communication loop, to construct, recognise and solve the puzzle. Similarly, it could be argued that as the language of digital games evolve, we see an analogous movement in its design practice -- from loops to spirals, embodied as ludic kennings. We can trace an evolution from designs strictly obeying tropes and medial standards to more experimental, subversive designs, to metareferential gestures playing with the parameters of the medium, encouraging reflection and critical awareness. One could point to a host of phenomena: from the blending of genre such as the contemporarily popular “Metroidvania” and “Roguelite” offerings, to intertextuality, metatextual subversions of gameplay and narrative, metaleptic incursions and excursions, and meta-medial incorporations. Remedy Entertainment, then, as a historied, highly popular development studio, provides a fascinating case study at the vanguard of this metamorphosis.

Endnotes

[1] Popular developer of PC benchmarking software, Futuremark (now UL Benchmarks), would begin at Remedy Entertainment before forming as a separate entity.

[2] Featuring characters named Woden and Balder, the evil corporation is named Aesir, the illegal drug they manufacture is named Valkyr, and more.

[3] The film is also nodded towards in chapter 7 of the game, which features a lobby design replete with metal detector entrance, similar to the film’s famous action sequence.

[4] A video of the secret room can be viewed here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=19geDYDIzhQ&t=114s

[5] Indeed, this is directly commented upon by Sam Lake in his video commentary for Alan Wake Remastered (2021).

[6] See https://skaldic.org/db.php?if=default&table=kenning&val=SWORD (Accessed 7/11/2023).

[7] Perhaps an intertextual nod to detective Saga Norén from the enormously popular Nordic noir television show Bron ("The Bridge").

[8] This is once again a reference to the legend of Baba Yaga, a witch who lived in a cabin standing on chicken’s legs.

References

Aarseth, E. (1997). Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. John Hopkins University Press.

Altheide, D. L. (1995). Horsing Around with Literary Loops, or Why Postmodernism is Fun. Symbolic Interaction, 18(4), 519-526. https://doi.org/10.1525/si.1995.18.4.519

Arkane Studios Lyon. (2021). “Deathloop” [Windows PC]. Digital game directed by Dinga Bakaba, published by Bethesda Softworks.

Backe, H-J. (2022). “Deathloop”: the Meta(modern) Immersive Simulation Game. Game Studies, 22(2). https://gamestudies.org/2202/articles/gap_backe

Bateson, G. (1979). Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity. Dutton.

Beebe, M. (1974). Introduction: What Modernism Was. Journal of Modern Literature, 3(5), 1065-1084.

Bolter, J.D., & Grusin, R. (1999). Remediation: Understanding New Media. MIT Press.

Bourriaud, N. (2009). Altermodern manifesto: postmodernism is dead. Supplanting the Postmodern, An Anthology of Writings on the Arts and Culture of the Early 21st Century, 255-269.

Butter, M. and Knight, P. (2021). Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Theories. Routledge.

Campbell, J. (1968). The Hero with a Thousand Faces (2nd ed). Princeton University.

Cudmore, D. (2018). Prophet, Poet, Seer, Skald: Poetic Diction in Merlínusspá. International Journal of Language Studies, 12(4), 29-60.

Doty, W. G. (2003). Myth and postmodernist philosophy. In K. Schillbrack (Ed.) Thinking Through Myths (pp. 142-157). Routledge.

Eagleton, T. (1996). The Illusions of Postmodernism. John Wiley & Sons.

Elsaesser, T. (2018). Contingency, causality, complexity: distributed agency in the mind-game

film. New Review of Film and Television Studies, 16(1), 1-39.

Elsaesser, T. (2021). The mind-game film: distributed agency, time travel, and productive

pathology. Routledge.

Eysteinsson, A. (2018). The concept of modernism. Cornell University Press.

Fokkema, A. (1991). Postmodern characters: A study of characterization in British and American postmodern fiction. Rodopi.

Fuchs, M. (2013). “My name is Alan Wake. I'm a Writer”. Crafting narrative complexity in the Age of Transmedia Storytelling. In G. Papazian, & J. M. Sommers (Eds.), Game On, Hollywood (pp. 144-155). McFarland & Company.

Fuchs, M. (2016). A Different Kind of Monster: Uncanny Media and Alan Wake's Textual Monstrosity. Global Interdisciplinary Research Studies, 3(1), 95-108.

Fuchs, M., & Thoss, J. (Eds.). (2019). Intermedia Games-Games Inter Media: Video Games and Intermediality (First edition.). Bloomsbury Publishing.

Future Crew (1993). Second Reality [IBM PC compatible]. Published by Future Crew.

Gadamer, H-G. (2004). Truth and Method (J. Weinsheimer & D. G. Marshall, Trans.). Continuum.

Garcia, A. (2022). Archetype and Individuation Process in Alan Wake (2010) Video Game: Game and Psychoanalytic Studies. Journal of Games, Game Art, and Gamification, 7(2), 1-10.

Gasiorek, A. (2015). A History of Modernist Literature (Vol. 7). John Wiley & Sons.

Genette, G. ([1972] 1980). Narrative discourse: an essay in method (J.E. Lewin, Trans.). Cornell University Press.

Genette, G. (1997). Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree (C. Newman & C. Doubinsky, Trans.). University of Nebraska Press.

Golding, D (2013) Putting the Player Back in Their Place: Spatial Analysis from Below. Journal of Gaming and Virtual Worlds 5(2), 117-130.

Gualeni, S. (2016). Self-reflexive videogames: observations and corollaries on virtual worlds as philosophical artifacts. G|A|M|E -- The Italian Journal of Game Studies, 1(5), 11-20.

Hassan, I. (1998). Toward a Concept of Postmodernism. In P. Geyh, F. Leebron, & A. Levy (Eds.), Postmodern American fiction: a Norton anthology (1st ed.). W.W. Norton.

Hassan, I. (2003). Beyond Postmodernism. Angelaki, 8(1), 3-11.

Hilliard, K. (2016). Making Max Payne -- How Hong Kong Kung Fu and Family Photo Shoots Built a Noir Thriller. GameInformer. https://www.gameinformer.com/b/features/archive/2016/03/27/making-max-payne-how-hong-kong-kung-fu-and-family-photo-shoots-built-a-noir-thriller.aspx

Hutcheon, L. (2006). A Theory of Adaptation. Routledge.

Hutcheon, L. (1988). The Poetics of Postmodernism. Routledge.

Jameson, F. (1997). Postmodernism, Or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Duke University Press.

Jørgensen, K. (2013). Gameworld Interfaces. MIT Press.

Jung, C. G. (1984). In W. McGuire (Ed.), Dream analysis: notes of the seminar given in 1928-1930. Routledge & Kegan Paul. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203754290

Kielich, S., and Hall, C. (2024). “As if Possessed by a Demon”: Subjectivity,

Possession, and Undeadness in Metal Gear Solid. Games and Culture, 0(0), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120241226828

Klaeber, F. (1922). Beowulf and the fight at Finnsburg. D.C. Heath & Co.

Konstantinou, L. (2017). Four Faces of Postirony. In R. van den Akker, A. Gibbons & T. Vermeleun (Eds.), Metamodernism: Historicity, Affect, and Depth After Postmodernism (87-102). Rowman & Littlefield International.

Kubrick, S. (Director). (1980). The Shining [Film]. Warner Bros.

Lyotard, J-F. (1984). The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge (G. Bennington & B. Massumi, Trans.). University of Minnesota Press.

Manovich, L. (2002). The Language of New Media. MIT Press.

Manovich, L. (2005). Understanding Meta-Media. CTHEORY. https://journals.uvic.ca/index.php/ctheory/article/view/14459/5301

McCarter, R. (2023). Alan Wake II Is Far Darker Than Its Predecessor -- and Perfects the Horror Genre. Wired. https://www.wired.com/review/alan-wake-ii-review/#:~:text=The%20first%20Alan%20Wake%20riffed,attempt %20to%20overcome%20writer%27s%20block.

McHale, B. (2008). 1966 nervous breakdown; or, when did postmodernism begin?. Modern Language Quarterly, 69(3), 391-413.

Miéville, C. (2009). Weird Fiction. In M. Bould, A. Butler, A. Roberts, & S. Vint (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Science Fiction (510-516). Routledge.

Mindrup, M. (2014). Translations of material to technology in Bauhaus architecture. Wolkenkuckucksheim Internationale Zeitschrift zur Theorie der Architektur, 19(33), 161-172.

Moran, J. (2023). Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis of Hero's Journeys in Zelda: Opportunities & Issues for Games Studies. Game Studies: The International Journal of Computer Game Research. 23(2), online. https://gamestudies.org/2302/articles/moran

Neitzel, B. (2008). Metacommunicative Circles. In S. Günzel, M. Liebe & D. Mersch (Eds.), Conference Proceedings of the Philosophy of Computer Games 2008 (pp. 278-295). Potsdam University Press.

Nohr, R. F. (2021). The Labyrinth Digital Games as Media of Decision-Making. In M. Bonner (Ed.), Game | World | Architectonics. Transdisciplinary Approaches on Structures and Mechanics, Levels and Spaces, Aesthetics and Perception (pp.133-49). Heidelberg University Publishing.

Polomé, E. (1972). 2. Germanic and the other Indo-European languages. In F. Coetsem & H. Kufner (Eds.), Toward a grammar of Proto-Germanic (pp. 43-70). Max Niemeyer Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783111549040.43

Radchenko, S. (2020). Metamodern gaming: Literary analysis of the last of us. Interlitteraria, 25(1), 246-259.

Radchenko, S. (2023). Metamodern Nature of Hideo Kojima’s Death Stranding Synopsis and Gameplay. Games and Culture, 0(0), 1-18.

Remedy Entertainment Oyj. (2010). Alan Wake [Microsoft Xbox 360]. Digital game directed by Sam Lake, published by Microsoft Game Studios.

Remedy Entertainment Oyj. (2023). Alan Wake II [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Sam Lake, published by Epic Games, Inc.

Remedy Entertainment Oyj. (2012). Alan Wake’s American Nightmare [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Sam Lake, published by Microsoft Game Studios.

Remedy Entertainment Oyj, D3T Ltd. (2021). Alan Wake Remastered [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Sam Lake, published by Epic Games Publishing.

Remedy Entertainment Oyj. (2019). Control [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Sam Lake, published by Microsoft Game Studios.

Remedy Entertainment Oyj. (2001). Max Payne [Microsoft Windows]. Published by Rockstar Games, Inc.

Remedy Entertainment Oyj. (2003). Max Payne 2: The Fall of Max Payne [Microsoft Windows]. Published by Rockstar Games, Inc.

Remedy Entertainment Oyj. (2016). Quantum Break [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Sam Lake, published by Microsoft Game Studios.

Russack, N.W. (1984). Amplification: The Spiral. Journal of Analytical Psychology. 29, 125-134.

Schmidt, H.C. (2021). The Paratext, the Palimpsest, and the Pandemic. In B. Beli, G.S. Freyermuth & H.C. Schmidt (Eds.) Paratextualizing Games: Investigations on the Paraphernalia and Peripheries of Play (pp. 373-398). Transcript Verlag.

Stobbart, D. C. (2016). Telling Tales with Technology: Remediating Folklore and Myth through the Videogame Alan Wake. In Examining the Evolution of Gaming and Its Impact on Social, Cultural, and Political Perspectives (pp. 38-53). IGI Global.

Storm, J. A. J. (2021). Metamodernism: The future of theory. University of Chicago Press.

Taylor, M. C. (1986) Deconstruction in Context: Literature and Philosophy. University of Chicago Press.

Vermeulen, T. & van den Akker, R. (2015). Misunderstandings and clarifications. Notes on Metamodernism. https://www.metamodernism.com/2015/06/03/misunderstandings-and-clarifications/

Wachowski, L. & Wachowski, L. (Directors). (1999). The Matrix [Film]. Warner Bros.

Waszkiewicz, A. (2024). The Show, the Game, and the Old Gods: On the Ontological Reframing and the Fiction/Real Boundary. Games and Culture, 0(0), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120241263652

Williams, R. (1977). Marxism and Literature. Oxford University Press.

Wood, A. (2012). Recursive Space. Games and Culture, 7(1), 87-105.