Bewildered by the Apparatus: Toward Opacity in Video Game Production

by Chaz EvansAbstract

This essay compares Activision Blizzard’s Overwatch and Studio Oleomingus’ Somewhere as two case studies. At opposite ends of the video game production scale, they evince cultural identity in very different ways. Through analysis of company press releases, trade press and close reading, these distinct mediated constructions of cultural identity reveal how gestures toward diversity in Overwatch demand legibility and subjection to terms set by a Global North-centric perspective, while the Somewhere series expresses specific histories and cultural traditions that refuse legibility to a larger image economy. The author evaluates both games through Souvik Mukherjee’s model of postcolonial video game criticism, Herman Gray’s theories of subjection and opacity, and Alexander Galloway’s realist notion of fidelities of context. When viewed through these theoretical lenses the character design choices in Overwatch belie a single-tier, postcolonial, transparent fidelity of context. Conversely, the work of Oleomingus offers an opaque fidelity of context built as a two-tier construction of postcolonial play. As a pair, they represent the limits of representation afforded to mass-market video game production methods, as well as the political efficacy afforded to small-scale game producers working with opacity. Additionally, the comparison directs attention to the video game production of the Global South as a critical area for reevaluating current assumptions and conventions of playable media.

Keywords: art games, Blizzard Entertainment, globalization, indie games, opacity, Overwatch, postcolonialism, representation, Studio Oleomingus

Introduction

The expectation around the term “video game” often presumes international megahits that take years and hundreds of workers to produce and demand the attention of fans distributed across markets and continents. However, video game production also exists at a smaller, regional level that corresponds to more specific cultures and audiences. While distinct from mass market video games, independent and arthouse game production is still connected to and affected by the flows of globalization. But indie and arthouse games are often not produced to be easily legible to a global audience. Considering the huge gap in resources between these two production contexts, how do we evaluate the valences of cultural, national and racial identity embedded in different scales of video game production? Is there a single method for understanding the effects of representation in video games writ large and small? How do multinational video game studios, and local artist-run video game studios deploy images of cultural identity differently? To consider these questions I’d like to compare Blizzard Entertainment’s Overwatch (2023) and Studio Oleomingus’ Somewhere (2018, 2020). Through close readings of these titles along with press and online reaction, I’ll position both in a political economy provided by Herman Gray’s theories of subjection and opacity. This framework is combined with an art historical perspective found in Alexander Galloway’s concept of fidelities of context, as well as a larger tradition of critical theory via Souvik Mukherjee’s model of postcolonial video game criticism. While different in aesthetics, mechanics and most of all production scope, the comparison of Overwatch and Somewhere will produce clarity on the overlooked tension between global and local video game production. Their comparison reveals the limits of representation for multi-national game studios and the discursive options available in regional small-scale video game production. Ultimately, Overwatch employs a transparent approach to representation that converts diversity into brand value so that identity can be exchanged in a media marketplace. On the other hand, the work of Studio Oleomingus operates in an opaque fashion which denies easy legibility in a Global North-centric attention economy, while making an offer of collectivity to a specific audience. The contrast between these two studios reveals how a game producers’ position on a production scale can reproduce or challenge extant power dynamics through video game texts in very different ways.

The Postcolonial Approach of Oleomingus

Dhruv Jani and his collaborator Sushant Chakraborty are the core of the small video game production team Studio Oleomingus. They have been developing video games and related art since 2014. They are based in Chala, India. Their games are distributed through their website and the video game sales platforms itch.io and Steam. While their audience is global, it is on a much smaller scale than any AAA game production company, yet like many of the large studios they create games through a transmedia approach. Since they began, they have been working on an ongoing project called Somewhere. Somewhere is a series of short narrative-driven video game vignettes. One of these short games, a Museum of Dubious Splendors (Studio Oleomingus, 2018), possesses a tableaux-style aesthetic constructed of objects and patterns that nod to India’s complex history, as well as themes of postcolonial Indian identity through a mix of fantasy and fact. Like other Oleomingus short games, it only offers glimpses of the larger world of Somewhere.

In Videogames and Postcolonialism: Empire Plays Back, Souvik Muhkerjee develops a model for understanding colonial and postcolonial notions expressed through the rhetoric of video games while also pointing out the lack of postcolonial theorization in video games studies. The postcolonial here is defined by Mukherjee (2017, p. 3) as any response to “a wide range of issues connected to the exploitative master discourses of Imperial Europe.” He emphasizes that many mass-market games (especially those that take human history as their subject matter) such as Civilization and Empire: Total War are developed from a deeply colonial perspective. The mechanics of these games frequently position the player as the mastermind of a society that values resource extraction and world domination as end-game goals and represents other cultures (often the cultures of the Global South) as exploitable subalterns.

However, for Mukherjee, it is in the moment of play that postcolonial review is temporarily brought into being, and therefore is the most important site of study, even if colonial ideas recalcify after play has concluded. If a player can rethink colonial norms by liberating a peasant or sabotaging British sea power in-game, it reveals the “fragility of colonial and neocolonial centers that apparently lend an air of finality to global representation.” Or, while borrowing a term’s specific usage from Homi Bhabha, Mukherjee (2017, p. 71) contends that the moment of postcolonial play can illustrate the “catachrestic” picture of modernity and globalization.

Published one year after Mukherjee’s Videogames and Postcolonialism, a Museum of Dubious Splendors is an excellent example of a postcolonial approach to a first-person perspective exploration game that leads the user through an unstable series of galleries and museum placards. The artifacts in each gallery form impressive still life compositions of everyday objects that hold special significance in the stories described in the placards. The stories in the placards are often told from a faux-colonial perspective. To offer an example, the first placard tells the story of Peter Gregory Cantor, a fictional British traveler that discovered an inscrutable device in India that he could only refer to as “The Apparatus.” Cantor becomes obsessed and undone by his confrontation with the object that he cannot describe or understand. Oleomingus then tells the player that they may now view “The Apparatus” that so bewildered Cantor right here in the Museum. The sequence ends with a visual joke revealing that “The Apparatus” is simply an imposing tube of toothpaste with a logo designed in Hindi. Oleomingus has not just created a work that is difficult to decipher, but also incorporates the narrative of the colonizer being undone by their own obsession with understanding their Other on their own terms. In doing so they extend the tradition of returning the colonial gaze to contemporary video game art. Oleomingus’ work broadens the postcolonial media making conversation (present in cinema through films like those of Med Hondo, or more recently in the photography of Tayo Adekunle) into video game-making practices.

Figure 1. The apparatus that so bewildered Peter Gregory Cantor in a Museum of Dubious Splendors. Copyright 2018 by Studio Oleomingus. Click image to enlarge.

While a player can open up a moment of postcolonial thinking in the playing of a Museum of Dubious Splendors (in the manner described by Mukherjee), for this work the moment of postcolonial play is of a second order. These video game makers are working at a small scale, are biographically Indian, are geographically based in the Global South, and are highly conversant in discursive reactions of European master discourses before the plan for producing a video game is hatched. What is the impact then of a moment of postcolonial gameplay, played in a game born of postcolonial game development? This is a question that would be difficult to even arrive at without considering specifically regional and economically small-scale video game production. But with this question at hand, how does the postcolonial view play out when a mass-market studio champions diversity through character design, art direction and narrative design? What kind of production choices are made when a AAA studio (often informed by fan reactions) is aware of problems in the marginalization of player characters representing the Global South, people of color, indigeneity, or queerness? Or in other words: what happens when a globalized, multinational video game studio produces games for the postcolonial moment? For this inquiry I turn to Blizzard Activision’s Overwatch.

Overwatch as Global Media Platform

Overwatch was officially released in 2016 by Blizzard Entertainment Inc.: a video game production company, and subsidiary of Activision Blizzard, headquartered in Irvine, California. Overwatch is a team-based, first-person shooter available for the Sony PlayStation, Microsoft Xbox, and Nintendo Switch consoles, as well as Windows PCs [1]. Beyond the game software running on PCs and home consoles, there and related paramedia such as animations, comic books and e-sports league competition broadcasts. The title Overwatch therefore refers to a large trans-media platform (or to use industry jargon, as intellectual property or an “IP”) as opposed to a singular video game.

Figure 2. The cast of characters included in the original Overwatch press kit. Copyright 2014 by Blizzard Entertainment. Click image to enlarge.

Although Overwatch is ultimately a varied set of media, the standard objective of the game at its core is simple. Two teams, composed of player characters with various identity assignments of nationality, gender, race, sexual orientation and religious backgrounds aim to control specific areas of maps for certain amounts of time. Players try to kill opposing players and keep teammates alive to control territory in futuristic versions of real-world countries. In other words, the team that controls geopolitical spaces through shooting and teamwork wins.

Subject(ed) to Recognition

The global scope of a media property like Overwatch is proportional to the scope defined in Herman Gray’s (2013) influential essay “Subject(ed) to Recognition.” While he does not discuss video games explicitly, Gray’s focus on the limits of representational politics across all media in the contemporary neoliberal political moment offers a valuable framework for considering the dynamics between Overwatch’s producer, Blizzard Entertainment, and its globally distributed audiences. Drawing primarily from examples of African-American media representation at different points in American history, Gray advances a theory that runs counter to some prevailing attitudes on representation of other cultural studies scholars and, increasingly, the public at large. This essay fits into a larger movement theorizing the political limits of representation in media such as Kristen Warner's (2017) critique of positive versus negative character depictions and plastic representation. Subject(ed) to Recognition is particularly relevant to this study of video game production as Gray directs his critique of representation past textual analysis and into the flows of global political economy.

Gray questions the link between increased media representation and the political advancement of a marginalized group. Instead, he suggests that the political efficacy of increased representation of marginalized groups is null and void, stating, “Rather than struggle to rearticulate and restructure the social, economic, and cultural basis of a collective disadvantage, the cultural politics of diversity seeks recognition and visibility as the end itself” (Gray, 2013, p. 2). This re-evaluation of identity politics is nuanced but centers around the logic that the increased representation of different minority groups in mainstream film, television and other media normalizes those groups into a celebration of “diversity” which replaces a discussion of “race” and alienates identity from its own politics. Instead of collective progressive movements based on racial identity during the civil rights era, representation of the early 21st Century is centered around the entrepreneurial subject using assignments of race, ethnicity, nationality, gender, sexuality, class and religion as branding strategies to advance the individual’s position within a consumer-driven, neoliberal system rather than to incite political change:

The object of recognition is the self-crafting entrepreneurial subject whose racial difference is the source of brand value celebrated and marketed as diversity; a subject whose very visibility and recognition at the level of representation affirms a freedom realized by applying a market calculus to social relations. This alliance of social, technological, and cultural fields constitutes a new racial regime -- the shift from race to difference. (Gray, 2013, p. 1)

Gray articulates his theory in the landscape of popular media in general, but only gestures at the role that digital media play in the co-optation of political power through representation (Gray, 2013, p. 771). Gray mainly focuses on writing about television and televised award shows as his objects of analysis in the latter half of the essay. Connecting Gray’s theory directly to Overwatch can reveal the limits of representation in globally distributed AAA video games and their paratexts. The application of Grey’s political economy-oriented approach beyond film and television to video games is a valuable supplement to scholars who have investigated video games through the lenses of race, gender and sexuality; such as the work of Jennifer Malkowski and TreaAndrea M. Russworm (2017), Carly Kocurek (2015) and Whit Pow (2024) among many others.

Blizzard’s Subjects of Recognition

The category of game development that players and fans typically believe has the greatest political consequence is the design of the player character, the protagonists that players control and, to some extent, identify with. Representation in video game player characters is skewed toward male and white identity assignments (Lin, 2023). Blizzard (2014) positioned Overwatch as a counter to this trend from its first press fact sheet released in 2014, stating that “Every match is an intense multiplayer showdown pitting a diverse cast of heroes, mercenaries, scientists, adventurers, and oddities against each other in an epic, globe-spanning conflict.” Although new characters are added over time, the cast maintains a calculated identity balance. Half the cast of playable characters are female, half are male. A quarter of the cast are women of color (such as Sombra the Mexican hacker, and Symmetra the Indian architect), a quarter are men of color (such as Lucio, the Brazilian D.J. and Doomfist the Nigerian cyborg mercenary), a quarter are white men (typified by Cassidy, the American Cowboy and Torbjörn the Swedish Engineer) and a quarter are white women (including Widowmaker the French Assassin and Mercy the Swiss Doctor). There are also some characters that would not fit traditional demography classifications, such as Bastion, a genderless robot, and Winston, a gorilla from the moon. Overall, the game’s character design proposes a demographic world that is somehow symmetrically fifty percent male, fifty percent female, fifty percent whiteness and fifty percent all other racial groups.

Overwatch is a visible example of a global production company presenting an intentional statement about inclusion and diversity in games, especially in comparison to other player character options in the field. In his panel presentation at the 2017 Progression Mechanics conference at Northwestern University, then Blizzard Senior Vice-President of Human Resources Jesse Meschuk (2017) cited the diverse characters available in Overwatch as emblematic of their company philosophy, stating:

We really believe in inclusiveness -- the power… people feel when they belong to a community that’s bigger than themselves… Overwatch is a good example of where we deliberately have tried to be inclusive of all different types of people.

Meschuk mentioned that Blizzard’s employees represent thirty-eight countries working at nine separate international campuses [2]. By associating the character design and background narrative of Overwatch as a Blizzard’s HR strategy, Meschuk suggests that the diversity of the Overwatch cast is not just a gesture of inclusion for players but is also a symbol of Blizzard’s corporate ethos.

Popular press has acknowledged how diversity was made a priority in Overwatch’s production history. Online video game trade magazine Gamasutra (now Game Developer) published an article titled “How Overwatch's bleak beginnings turned into positivity and inclusiveness” in 2017, less than a year after release. Its author Kris Graft (2017) tells the story of how, over the late 2000s and early 2010s, video game professionals from all over the world were developing a new game for Blizzard called Titan. In 2013 the game was canceled, and the majority of the large team were reassigned to different teams across the globe. Forty remaining developers from the Titan project were challenged with coming up with a new game idea to replace the canceled one in two weeks, and in that time they came up with the concept for Overwatch. Graft is quick to point out that the relocation of many international team members mirrors an important part of the Overwatch backstory, where a daring group of international heroes is assembled to save the world but then is forced to disband by a global government that no longer trusts them and forces them to hide in all corners of the world. The unstable but determined labor climate set the stage for Overwatch's near-future dystopia of global instability portrayed through a bright, adventurous and optimistic tone. Overwatch game director Jeff Kaplan places inclusion at the center of this concept, saying:

What we cared about a game and a game universe and a world where everyone felt welcomed… What the goal was was [sic] inclusivity and open-mindedness… Diversity is a beautiful end result when you embrace inclusivity and open-mindedness. (Graft, 2017)

There are examples of a “push” for diversity playing out dynamically between Blizzard and its audiences. After characters were announced, but before the game’s release, popular video game blog Kotaku published a story titled “New Overwatch Character Shows Blizzard is Really Listening,” (Hernandez, 2015) which detailed the call and response of fan criticism and developer changes in anticipation of the game. Kotaku suggests that feminist critics, including noteworthy feminist video game vlogger Anita Sarkeesian, were unsatisfied with the female cast of Overwatch as they all conformed to the same body type that expresses unrealistic standards of female beauty. Blizzard responded by announcing a new character Zarya, the Russian bodybuilder, one of the world’s strongest women. Blizzard released a statement claiming the new character was an expression of improved representation and diversity:

We've been hearing a lot of discussion among players about the need for diversity in video games. That means a lot of things. They want to see gender diversity, they want to see racial diversity, they want to see diversity along the lines of what country people are from. There is also talk about diversity in different body types in that not everybody wants to have the exact same body type always represented. And we just want you to know that we're listening and we're trying hard and we hope Zarya is a step in the right direction… We want everybody to come and play. Increasingly people want to feel represented from all walks of life, everywhere in the world. Boys and girls -- everybody. We feel indebted to do our best to honor that. (Hernandez, 2015)

As the title of the Kotaku article indicates, the press praised the new character as a progressive step in the right direction. Its author concluded, “It really is cool to see more body types represented in games, you know (Hernandez, 2015)?” Pleased as this Kotaku writer was about the response from Blizzard, Blizzard’s language frames diversity as a matter of customer service. The desire for “everybody to come and play” is enacted as a revaluation of identity as brand value (vis-à-vis Gray) and player base growth.

Years after the release of Overwatch, the image of diversity as a key corporate value has been compromised by a series of lawsuits brought against Activision Blizzard that drew heavy attention in both video game and conventional press. In 2021 the California Department of Fair Employment & Housing (2021) brought a suit against Blizzard alleging an ongoing culture of sex discrimination and sexual harassment that was known and tolerated at the highest level of management following a two-year investigation. Also in 2021, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission brought a similar suit that was eventually settled for $18 million, complicating the proceedings of the ongoing DFEH Lawsuit (Jiang, 2022). Related, but separate lawsuits include a case against brought by attorney Lisa Bloom who represents eight women with sexual harassment complaints against Blizzard (Silberling, 2022), and a wrongful death lawsuit from the family of a Blizzard employee who committed suicide during a company retreat (which has since been dropped) (Phillips, 2022), multiple class action lawsuits from the company’s stockholders over false statements made regarding the above allegations of widespread culture of sexual misconduct (Fahey, 2021), and an additional suit from the U.S. Department of Justice (2023) alleging suppression of e-sport player compensation directly concerning players in The Overwatch League. The ongoing coverage of these events have pushed Blizzard’s image far from a paragon of diversity and inclusion for both video game workplaces and character design, but instead a symbol of the video game industry reckoning with its own #MeToo moment.

Overwatch can be read as an aspirational self-portrait of Blizzard Entertainment, the global corporation who produces it. This self-portrayal is set in tension against its labor environment described as toxic by press coverage and legal challenges. T.L. Taylor (2012) describes how emerging esports communities are shaped by the competing interests of several stakeholders. In a similar way, the flows of Overwatch are defined by different stakeholders, at distinctly different positions of power, striving for competing (and often mutually exclusive) goals. Developers and staffers strive for identification and creative autonomy in their work, pushing against the discretion of management. Hobbyist players make demands for representation and access in the games they play, while others demand its negation, both negotiating with the labor time and creative discretion of developers. Professionally competitive players, and team owners want their commensurate portion of credit, control and compensation, competing with the vertically integrated control of management. Management tries to extract the maximum play effort, labor and revenue without discouraging participation, sales and morale of all other parties. All the while, developers and staffers legally confront management over toxic workplace conditions, directly contradicting the progressive and diverse corporate ethos that management is trying to project. These struggles over power and access are competing drives that never reconcile or reach equilibrium, yet the ongoing conflict has a sustaining effect for the entire enterprise.

If all these negotiations are holistically viewed as a complex network of competing interests, Overwatch can be recognized not as a simple video game, but as a whole political system with a video game running at its core. The “diversity” of the image economy of Overwatch characters does not deliver political progress per se. Instead, they normalize marginalized groups as better consumers of the media market that is controlled and managed by companies like Blizzard. Although marginalized groups are afforded more opportunities to identify with the characters represented on screen, the design of these characters and the terms of their release and use are set by Blizzard, Jeff Kaplan and the Overwatch team, headquartered in California, but with aspirations of becoming an ever more powerful, though benevolent in appearance, global corporate power. Small, quotidian gains are made in individual negotiations, but according to Gray, in individual victory, marginalized groups are alienated from their ability to deliver collective grievances to the system that governs them.

It’s important to acknowledge how counterproductive a critique like Gray’s can feel to those who are actively involved with projects to increase representation of marginalized groups in media. Is nothing of value in diversity for a video game fan who has more ability to identify with one part of an enormous media system, rather than being left out of it like so many other power structures? Here it’s useful to consider Overwatch through Mukherjee’s lens of postcolonial play. Blizzard is attempting to solve problems of exclusion with a push for diversity while simultaneously making a push for more gaming subjects. Their legal dramas suggest that values of diversity writ large are compromised by the production culture within the company. As Mukherjee suggests, a player can play through the multiple identities embedded in Overwatch characters in a manner that creates space for postcolonial imagination, review and criticism. This is a moment of engagement similar to the playful erotics described by Christopher Patterson’s analysis of Overwatch in Open World Empire. Patterson (2020) contends the moment of play can be conceptually generative and consciousness-raising, but concludes that video games ultimately have no liberatory power over empire; no moment of systemic change. Therefore, even the reflexive, postcolonial act of playing Overwatch can only be an act of postcolonial play of the first-order: one generated by a postcolonial player of a game created through a colonial development process. But Patterson’s claims are based on a survey of AAA titles and small-scale studios have been left out. Could the small side of the production scale point us toward how to practically build a moment postcolonial play of a second order, one that can resolve identity outside of the terms set by global centers of power?

Transparency and Opacity

Gray’s framework in “Subject(ed) to Recognition” can look like what Alexander Galloway (2014) calls “reticular pessimism,” where an ideological network is so pervasive there is simply no outside and apparently no theoretical alternative. In “Reading Peabody,” Gray offers a way out of this representational cul-de-sac (Gray, 2019). Through research in the Peabody Television Archives, Gray identifies two approaches for television production built upon the theory of Édouard Glissant: transparent programs and opaque programs. Analyzing locally produced television dealing with the subject of race during the American Civil Rights era, Gray determines that transparent shows incorporate marginalized groups into media where they can be clearly seen and understood in terms determined by the party in power (Gray draws on shows where African-Americans are questioned about race by white interviewers). However, opaque shows are developed from the perspective of the marginalized party through artistic and experimental techniques that do not submit to the questions put in place by the hegemon. In Gray’s examples, opaque television, made by African-Americans on their own terms, refuses the white desire to know the Other.

The essay begins with an epigram from the W.E.B. Dubois’ The Souls of Black Folk: “To the real question, How does it feel to be a problem? I answer seldom a word.” (Gray, 2019, p. 79). The quote distills Dubois’ refusal of the terms of the question set by a white power structure. In so doing, he redirects attention to the ways white America has produced the black American as an inscrutable social problem in need of observation and analysis. Similarly, the opaque television programs produced by black Americans redirect attention away from definitions and questions of race set by white hegemony, while simultaneously refusing legibility to the white viewer as well. In this recentered construction of identity in media, different engagements with race can begin to take shape and function outside the hegemonically-driven politics of representation.

A similar maneuver could take place through other media, between different geographical relationships and between different sets of power relationships. Opaque media is not specific to mid-century regional television of the United States. Discursive refusal can be historically and regionally variable. But how do you produce a video game that refuses the hegemonic way that Blizzard governs the terms of identity in Overwatch?

The Video Game Producer’s Fidelity of Context

I’d like to pair Gray’s framework with an additional tool from video game studies that rhymes with the distinction between transparent and opaque media. In “Social Realism” Alexander Galloway provides a clarification between what is realistic and realist, two terms that are often conflated in video games. Galloway argues that when people talk about video game realism, they are normally referring to how realistic they are represented visually. Realisticness is simply a measure of visual accuracy. In contrast, realism is an art historical term with a long tradition of social commentary behind it. Borrowing concepts from Italian neo-realist film, Galloway states that realist games must evince some kind of critique of lived reality (Galloway, 75).

In other words, realism can speak politically, where a “realistic” work of art is not interested in (or capable of) doing so. Most American military shooters, such as the Call of Duty franchise, are simply realistic; they function as propaganda and have little bearing on the lived experience of contemporary theaters of war. On the other hand, Galloway suggests a “congruence requirement” for a video game to be considered realist. He says that for a video game to be truly realist, there must be a “fidelity of context” between player and game (Galloway, 78). If a video game does have social commentary on human experience embedded in it the player of the game must also have an individual connection to the lived reality commented upon in the game, whether it be a shared race, gender, sexuality, class, national, or cultural context. A game could then cease to be, and then again become, realist depending on who is playing.

While I have found the categorical distinction between realist and realistic invaluable for clearing confusion in the language of game studies, I find the fidelity of context between video game industries and the representations they produce to be more relevant than the fidelity of context between player and game. At least some of the political reality described by a realist video game could be communicated to a player of a different cultural context, even if they have not experienced the full political reality of the game firsthand. Attention toward the congruence between game and lived experience is valuable for considering the wide contingency of playstyle and player reception, but why not also focus on the contingencies between developer style and game production? The developer’s fidelity of context (or lack thereof) is embedded into game mechanics, character design, art assets and environmental design. The political valences of identity in video games are visible in the relationship between playable representation and video game producer.

The Transparency of Symmetra

Let me return to the Overwatch character offered by Blizzard to represent India, Symmetra. Symmetra’s backstory is that she is originally from an impoverished community in Hyderabad but is now employed as an architect for the high-powered Vishkar Corporation. In a web comic published about the character, Blizzard reveals that although Symmetra believes in utopian values of improved lives for all, she is compromised by the dubious methods used by her employer to secure public sector contracts. In-game, she is considered a “support” character (rather than a “damage” or “tank” character). She has a weak handheld weapon which is not effective in direct combat. Instead, she builds laser turrets that serve as remote traps for the enemy team, has the ability to build a teleporter that teammates can travel through, and can deploy an energy barrier that blocks enemy attacks. In other words, her role is to build technology to aid teammates.

Figure 3. The selection screen for Symmetra included in the original Overwatch press kit. Copyright 2014 by Blizzard Entertainment. Click image to enlarge.

While she is portrayed as a powerful female character embraced by many players [3], I’d like to suggest that Symmetra is an example of a transparent fidelity of context between the producer and designed gameplay elements. Powerful as she may be, Symmetra’s design is undergirded by a Global North-centric perspective trying to engage Indian and female identifying players while trafficking in stereotypes of Indian people and women held by that same Global North-centric perspective: Symmetra is a skilled professional, not a soldier, lone-gun, or assassin. Essentially, Blizzard has positioned Symmetra as the tech support character for the other fighters of the Overwatch cast. Her design conceals a US-originating technology company’s attitude toward Indian labor within a heroic exterior. Visually speaking, her character design looks highly impractical for combat and has as much to do with superhero aesthetics as South Asian sartorial traditions. She can be quickly identified as Indian by players, but more importantly is quickly and digestibly identifiable as Indian to Blizzard. In other words, Symmetra is a transparent approach to game production; a template of Indian identity developed by a globalized American company. India is represented, yet carved from an idea of recognition designed by a mass market studio with a vested interest in diversity as corporate reputation. Following Mukherjee's invocation of Bhabha, the design of a character like Symmetra, along with other identities represented in Overwatch, presents a highly catachrestic image of world cultures. Overwatch offers representations for many, yet those representations contain assumptions, omissions and misunderstandings that are built into the perspective from which they were designed.

The Opacity of Oleomingus

If Symmetra is an exemplar of transparent character design, what do opaque video game production choices look like? Let us refer back to when fictional British traveler Peter Gregory Cantor was bewildered by “The Apparatus” in a Museum of Dubious Splendors. The moment reads like a playful example of Gray’s theory of opacity. It narrativizes a white British colonial perspective blocked through the opacity of its own obsessive terms of vision, while also providing a puzzlingly opaque play experience for the audience member in the non-fictional global present. Many expectations of the “core” gamer perceived by AAA studio designers are deliberately obviated by the game’s mechanics. There are no points to score, there is no combat to wage, no way to win or lose and no fantasy to empower. Instead, the challenge of this game is deciphering the tableaux of the museum, the puzzling texts that accompany them and generally figuring out what it is you are even supposed to do in this experience. These can all be considered techniques of opaque video game production more available to small-scale game artists than to the mass-market studio. As Studio Oleomingus’ career progressed, they have found ways to deepen and reposition the effect of opaque game making where, similar to Grey’s conclusion on opaque television, “the gaze of whiteness and the desire of whiteness to know is no longer the point (Gray, 2019, p. 93).”

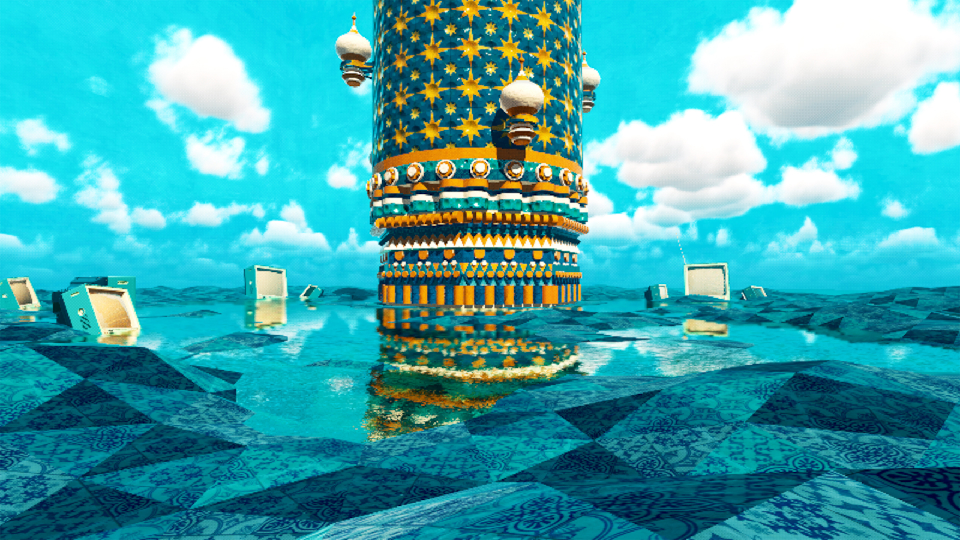

Figure 4. The tower assigned to be eaten in The Indifferent Wonder of Edible Places. Copyright 2020 by Studio Oleomingus. Click image to enlarge.

In 2020, Studio Oleomingus published The Indifferent Wonder of Edible Places as a later entry in the Somewhere series and also exhibited versions of the game in Phoenix Gallery, Leicester and VGA Gallery, Chicago in advance of its wider release. This is a 3D first-person perspective game where you play as Anwar A. Hamid, who is a newly licensed building eater. The job of building eater is assigned by The Ministry of Entangled Histories and the Ministry of Labour and Employment in order to “employ jobless youth by the state and remove entangled and dubious history that prevents glorious national destiny.” After learning this through title cards type-set with bureaucratic aesthetics, the player is confronted with an imposing tower with a few cathode-ray tube style monitors dappled around its perimeter. The playable task is to eat blocks of the tower in a certain numerical order that is displayed on the monitors to clear it away. Between eating blocks, the player is shown a series of epistolary text cards that display a message from Hamid to his brother. Hamid expresses deep regret and reluctance for taking the role of building eater but also did not feel he had any other choice. He considers himself lucky to be eating a remote building that no one is using rather than a home or a mosque. Over the course of play, it becomes clear that building eaters like Hamid have been conscripted to erase their own culture through the sponsorship of a state power. The player’s “reward” for completing the task of eating the building blocks in the right order is an urgent missive from Dhruv Jani of Oleomingus:

I write this note while my country has become a colonizer of its own people.

When my government is excluding and including citizens, to curate for itself a republic that is as willing to forget uncomfortable truths as it is to defend unfortunate lies. I write amidst a degree of religious and doctrinal violence perpetrated on fragile bodies and fragile communities, that is scarcely to be imagined. And when, places of entangled heritage and syncretic history, that repudiate the rule and narrative of a Hindutva majority, have become sites of perpetual conflict. If amidst such hurt and erasure, believing in and espousing the possibility of an inclusive record of our lives, is a form of rebellion, then this game is certainly an act of resistance. Created in solidarity with all those brave enough to stand against the government and protest the withdrawal of our right to live in a generous nation.

January 2020 (Studio Oleomingus, 2020)

The puzzle of eating a building block by block is revealed to be a pretext. The real puzzle solved through the play and effort of this game is to learn who the player character is and what predicament they are in: Hamid is a Muslim minority pressured to deny their own identity at the directive of a Hindu nationalist state. However, because this predicament is revealed through a poetic play space the first-person identity that the player inhabits could function as a stand-in for Othered identities coerced into participating in their own erasure.

The Indifferent Wonder of Edible Places is developed through a highly congruent fidelity of context between author and subject matter, although the fidelity of context between game and player is indeterminate. It is a noteworthy example of a postcolonial video game designed through opaque production techniques. As a work of software where a minority perspective is voiced as a reaction against a colonizing master discourse, it is a postcolonial gesture by design. In a moment of play, an Othered perspective that decenters neo-colonial power is given affordance in virtual space where it is otherwise restricted. This is where a deepened notion of opacity in video game production is particularly significant. This game is not about returning the gaze of the white colonizer, or about deconstructing a Eurocentric description of the Global South. Here the white, European and North American perspective is denied a place in the conversation altogether. A different line of sight is obscured by video game opacity: the sight of an Islamophobic Hindutva majority that would seek to determine the shape of non-Hindu culture on its own terms. While identifying the Hindu nationalist majority as a neo-colonial construction, Oleomingus’ proposal is not to replace it with another neo-colonial reversal of power. Instead, they make an interactive artwork that serves as a space for a counter-perspective to temporarily exist.

In a correspondence with their audience on their itch.io page, Oleomingus has mentioned that they are interested in the idea of appropriating ideas and aesthetics of British Colonial narratives of India, such as Rudyard Kipling (Jani, 2018), but refashioning them in their own pastiche of metatextual gameplay in a way that counter-colonizes cultural notions placed by the historical colonizer. But over their career they have moved past the analysis of Indian identity entangled with British colonization to an opaque game making technique that can apply postcolonial approach to current political crises in the subcontinent. Oleomingus designs characters, environments and mechanics that distinctly reflect Indian traditions but refuse normalization in a global marketplace of imagery. They are not drawing on a template of how Indian culture ought to look in terms of diversity and representation, yet they are in a sense representing India through an opaque fidelity of context. By obscuring the clarity of Indian identity, their work offers a subtle refusal of the impossible task of representing a formation as vast and complex as “Indian-ness.” Beautiful as they appear, these games are, by design, challenging to understand, for an English-speaking audience. They are also challenging to understand for a Hindutva majority in India and its diaspora. They therefore offer something simple, yet difficult to come by in corporeal space in times of crisis, a moment of solidarity between those who might share a voice and perspective.

Conclusion: In Support of Opaque Video Games

Ultimately, The Indifferent Wonder of Edible Spaces is developed from a postcolonial approach that supports moments of postcolonial play of a second order. But what is the magnitude of postcolonial play occurring at two levels? This game advances what Gray says is impossible in the neoliberal subjection of media representation: an offer of collectivity, an act of coalition building. A poetic space of oppositional solidarity. Oleomingus does not exchange their own identity formation for brand power. Their self-depiction of cultural heritage is too opaque to function as currency in the attention economy. Compared to the statistics of Blizzard, these are not popular games. When addressing a specific political crisis, unpopularity is an affordance, not a problem to be solved with more promotion or addictive mechanics. Instead of legibility to a larger global media economy, they are legible to those they need to reach. The game is not a campaign for audience members or replayability, but a beacon for those who share a perspective. Unlike the passionate mischief of playful erotics, this second order of postcolonial play can find a purchase in a coalition. It is a small foothold at the margin of empire, but it can announce a moment of collective grievance, working against the individualist brand value activism criticized by Gray.

This then is the opportunity available for indie and arthouse games running at a small scale that AAA games are denied: do not endeavor to gain more recognition for your games in a popular attention economy. Instead, make your video game realities visible to yourselves and those you can build collectivity with. If opacity to popularity is what it takes to build that collectivity in times of crisis, so be it.

Oleomingus' Somewhere series embeds visual motifs, story and play that draws deeply from regional identification with India in a way that does not fit a system of globalization delineated by a company like Blizzard. Like Grey’s theory of opaque television, Oleomingus’ work resists clear recognition and therefore frictionless neoliberal subjection. While I would not argue that producers of opaque video games have found a way to escape neoliberal subjection altogether, there are certain methods of opaque game production that can embed unrecognized and therefore unsubjected elements of cultural identity into the discipline. In the case of Overwatch, the subjection of representation plays out in a manner compatible with Gray's theory of subject recognition where race is exchanged for “diversity” and “difference.” Blizzard’s methods of signifying cultural identity in the design of characters and game mechanics are transparent, recognizable and easily digested by the globalized “view from nowhere” which is in fact shaped by a white North American and European-centric perspective. These two distinct approaches can be found by comparing fidelities of context between video game producer and the modes of play they produce and discursively refusing hegemonically contrived terms of subjection and visibility.

When the fidelity of context is congruent and a media text refuses transparency, we may see methods of political negotiation not previously available in game production. Opaque elements of game design are in fact an expression of specific cultural identity and difference. Yet they speak from a non-hegemonic perspective that can alter the global conversation of game production. This in turn generates a richer set of representative possibilities and complicates the prefabricated constructions of representation distributed from the post-colonizer to the post-colonized. Opaque games are especially timely for video games simply because their conventions are emergent and often unresolved. This study in opacity should draw the attention of video game players, historians, critics and scholars away from the video game studio system of the Global North (AAA, indie, arthouse, or otherwise). Instead, we can relocate our attention to Global South’s production centers where neoliberal assumptions of play can be unpacked, and discipline-changing interventions in game making can be found.

Acknowledgements

I am sincerely grateful for the generous feedback of Evan Meaney, Sriram Mohan, Maureen Ryan, David Sella-Villa, and the anonymous reviewers. Additional thanks to Dibyadyuti Roy and the Digital Humanities Alliance for Research and Teaching Innovations (DHARTI) for inviting me to share an early version of this project with them at IIM Indore and offering me their thoughtful responses and questions.

Endnotes

[1] In August of 2023 Blizzard Entertainment released a new version of the game and rebranded the title Overwatch 2. Unlike many sequels which deliver a new and distinct product, this new version replaced the earlier version of the game and, to the confusion of some audience members, makes the current title both an updated version and a sequel of sorts. Since this analysis targets the entire Overwatch media franchise over its history as a scope, I will continue to refer to the title as Overwatch for the sake of brevity, even though its current brand is Overwatch 2.

[2] At the time of Meschuk’s remarks there were two campuses in the US: Irvine and Austin, then Versailles, Seoul, Cork, Shanghai, Sydney, Taipei and the Hague. At the time of writing there are four in the US: Albany, Austin, Irvine and Boston, then Cork, Seoul, Shanghai, Sydney and Taipei.

[3] Refer to Tanja Välisalo and Maria Ruotsalainen’s work about how Symmetra has been championed by some Overwatch fans as a queer icon, despite Blizzard’s identity assignments designed into the character (Ruotsalainen, 2022).

References

Blizzard Entertainment. (November 7, 2014). Blizzcon 2014 Overwatch Press Kit. Blizzard Press Center. https://blizzard.gamespress.com/blizzcon-2014-overwatch-press-kit

Blizzard Entertainment. (2023). Welcome to the Overwatch League. The Overwatch League. https://overwatchleague.com/en-us/about

Blizzard Entertainment. (2.8.0.0.119560, 2023) [2016]. Overwatch 2/Overwatch [Sony PlayStation 4]. Digital game directed by Jeff Kaplan (2016-18) and Aaron Keller (2018-), published by Blizzard Entertainment.

California Department of Fair Employment & Housing. (July 21, 2021). DFEH Sues California Gaming Companies for Equal Pay Violations, Sex Discrimination, and Sexual

Harassment. Civil Rights Department, State of California. https://calcivilrights.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/32/2021/07/BlizzardPR.7.21.21.pdf

Fahey, M. (August 3, 2021). Activision Blizzard Faces Second Lawsuit Over First Lawsuit. Kotaku. https://kotaku.com/activistion-blizzard-faces-second-lawsuit-over-first-la-1847415904

Galloway, A. (2006). Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture. University of Minnesota Press.

Galloway. A. (2014). Network Pessimism. Alexander R. Galloway website. http://cultureandcommunication.org/galloway/network-pessimism

Graft, K. (February 22, 2017). How Overwatch's bleak beginnings turned into positivity and inclusiveness. Game Developer. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/design/how-i-overwatch-i-s-bleak-beginnings-turned-into-positivity-and-inclusiveness

Gray, H. (2019). Reading Peabody: Transparency, Opacity and the Black Subject(ion) of Twentieth-Century American Television. In Thompson, E., Jones, J. P., & Hatlen, L. (Eds.), Television history, the Peabody Archive, and Cultural Memory (pp. 79-95). The University of Georgia Press.

Gray, H. (2013). Subject(ed) to Recognition. American Quarterly, 65(4), 771-798. https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2013.0058

Hernandez, P. (March 6, 2015). New Overwatch Character Shows Blizzard Really Is Listening. Kotaku. https://kotaku.com/new-overwatch-character-shows-blizzard-really-is-listen-1689904549

Jani, D. [Studio Oleomingus]. (2018). p.s : The reason it seems a little bit like Kipling's writings [Comment on the online forum post a Museum of Dubious Splendors.]. Itch.io. https://itch.io/post/333960

Jiang, S. (March 29, 2022). Activision Blizzard Settles Sexual Harassment Lawsuit For $18 Million. Kotaku. https://kotaku.com/activision-blizzard-settlement-eeoc-dfeh-trial-call-of-1848719873

Kocurek, C. A. (2015). Coin-Operated Americans: Rebooting Boyhood at the Video Game Arcade. University of Minnesota Press.

Lin, B. (February 22, 2023). Diversity in Gaming Report: An Analysis of Diversity in Video Game Characters. https://diamondlobby.com/geeky-stuff/diversity-in-gaming/

Malkowski, J., & Russworm, T. M. (Eds.). (2017). Gaming representation: race, gender, and sexuality in video games. Indiana University Press.

Meschuk, J. (2017, September 15-17). Issues in Video Game Culture - Ongoing, Current, Upcoming [Conference presentation]. Progression Mechanics, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, United States. https://www.youtube.com/live/L67Xb4tgVv8?feature=shared

Mukherjee, S. (2017). Videogames and Postcolonialism: Empire Plays Back. Palgrave Macmillan.

Patterson, C. B. (2020). Open World Empire: Race, Erotics, and the Global Rise of Video Games. New York University Press.

Phillips, T. (June 1, 2022). Activision employee wrongful death lawsuit dropped. Eurogamer. https://www.eurogamer.net/activision-employee-wrongful-death-lawsuit-dropped

Pow, W. (June 5, 2024). "Critical Game Studies and Its Afterlives: Why Game Studies Needs Software Studies and Computer History." Just Tech. Social Science Research Council. DOI: doi.org/10.35650/JT.3071.d.2024.

Ruotsalainen, M., Välisalo, T. (2022). “Sexuality does not belong to the game” - Discourses in Overwatch Community and the Privilege of Belonging. Game Studies, 22(3). https://gamestudies.org/2203/articles/valisalo_ruotsalainen

Silberling, A. (October 13, 2022). Activision Blizzard is once again being sued for sexual harassment. Tech Crunch. https://techcrunch.com/2022/10/13/activision-blizzard-is-once-again-being-sued-for-sexual-harassment/

Studio Oleomingus. (2018). a Museum of Dubious Splendors [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Dhruv Jani, published by Studio Oleomingus. https://studio-oleomingus.itch.io/a-museum-of-dubious-splendors

Studio Oleomingus. (2020). The Indifferent Wonder of an Edible Place [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Dhruv Jani, published by Studio Oleomingus. https://studio-oleomingus.itch.io/the-indifferent-wonder-of-an-edible-place

Taylor, T. L. (2012). Raising the Stakes: E-Sports and the Professionalization of Computer Gaming. MIT Press.

U.S. Department of Justice. (April 3, 2023). Justice Department Files Lawsuit and Proposed Consent Decree to Prohibit Activision Blizzard from Suppressing Esports Player Compensation. U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-files-lawsuit-and-proposed-consent-decree-prohibit-activision-blizzard

Warner, K. J. (2017). In the Time of Plastic Representation, Film Quarterly, 71(2). https://filmquarterly.org/2017/12/04/in-the-time-of-plastic-representation/