Commemorating Gendered Collective Trauma: Social Realism and Procedural Rhetoric in the Chinese Indie Game Laughing to Die

by Mayshu (Meixu) ZhanAbstract

This article examines Laughing to Die (2022), an indie game that employs rule-based mechanics and Chinese horror aesthetics to critique gender-based violence and systemic oppression in mainland China. The study builds on Ian Bogost's procedural rhetoric (2007) and Alexander R. Galloway's framework of social realism in gaming (2004), contextualized within mainland China's legacy of socialist realism and state censorship. While Western scholarship has analyzed themes like war, colonialism and marginalized identities, this study addresses the gap in non-Western contexts by focusing on how indie games engage with gendered collective trauma and generational suffering. It also critiques Galloway's lack of specificity in how critical design can achieve social realism.

Laughing to Die demonstrates how games can transcend entertainment to address serious social issues. Through puzzle-solving and navigation in gamespaces, players engage with narratives of women's trafficking and domestic violence. Such design reduces psychological defenses against difficult themes, transforming players into "player-historians" (Chapman, 2016) who witness, reconstruct and interact with stories of systemic injustice. This participatory engagement fosters empathy and deeper understanding of patriarchal oppression.

The study thus argues that Laughing to Die exemplifies grassroots resistance to ideological control and capitalist homogenization. By amplifying silenced voices and critiquing power structures, the game contributes to a nuanced public sphere for social critique within mainland China's restrictive media environment. This research contributes to non-Western game studies, demonstrating how indie games can navigate censorship and tackle systemic injustices through critical design.

Keywords: critical play and design analysis, Chinese social realism games, collective trauma, player historians, cultural resistance

Introduction

Laughing to Die [Xisang 喜丧] (Dajili Studio, 2022) is a puzzle-based, story-driven horror game developed by the independent studio Dajili Studio [Dajili Zhizuozu 大吉利制作组] [1] and published by Gamera Games, known for promoting hidden independent (indie) games. Originally released in 2022 on GCORES, a gaming platform for fandom culture, for domestic audiences, it was officially published on Steam in 2024 for international players. The game has received critical acclaim, particularly for addressing real-world issues like the trafficking of women, forced marriages and domestic violence in rural China [2] -- a hotly discussed issue in China's public sphere through cases like the "Xuzhou Chained Woman Incident" [Xuzhou tieliannv shijian 徐州铁链女事件] [3] and the child-trafficking crimes of Yu Huaying [余华英] [4].

The game begins with a cut-scene depicting a girl traveling to her grandmother's funeral, clutching a toffee while her father drives through muddy roads to a poor village. The funeral, traditionally meant to celebrate a long life with laughter rather than tears, quickly takes a darker turn when the girl sees a figure resembling her grandmother and follows it into the living room. Here, players take on the girl's avatar, solving puzzles and gathering clues to fulfill her grandmother's final wish: to "go home."

Figure 1. A screenshot from Laughing to Die, showcasing the game's environment.

The player navigates the gamespace using basic controls: "A" and "D" to move, "W" to jump and the space bar combined with "A" or "D" to drag objects to stand on, enabling the avatar girl to reach clues positioned too high. The avatar girl is guided through the game's dual realms, each symbolizing a different aspect of the grandmother's life: the upper realm represents her life after being trafficked, while the lower realm reflects her earlier, happier family life. As the player shifts between these realms, they gather clues in a memory palace, piecing together the story to uncover the unsettling reasons behind the grandmother's final wish to "go home" -- despite her having died at home. This request lingers mysteriously, hinting at a life fragmented by trauma and longing, suggesting that "home" may represent something unresolved.

In the following text, I will critically appraise Laughing to Die, adopting a methodology grounded in "critical play" and "critical game design" (Flanagan, 2009; Jagoda, 2020; Pötzsch, 2015). My primary methods include humanistic approaches, such as close reading, applied here as critical play by deeply engaging with the game's mechanics, narrative and audiovisual design. This analysis is further shaped by my experience as an indie game designer, influenced by Mary Flanagan's (2009) emphasis on politically conscientious game design that fosters social critique and intervention, offering a creator’s perspective to the evaluation.

Through this lens, I examine how Laughing to Die transcends entertainment to serve progressive politics, inviting players to confront deeper social and ethical issues around gender-based violence embedded in its procedural, narrative and audiovisual structures. While conducting formal and medium-specific analysis, I also situate videogames within mainland China's broader socio-political context, acknowledging their potential to foster social realism -- a critical framework that reflects real-world struggles and injustices to raise social awareness and critique.

This article is organized into three sections. First, I analyze the indie game Laughing to Die through Ian Bogost's concept of procedural rhetoric (2007) -- rule-based representations -- and Alexander R. Galloway's framework of "social realism in gaming" (2004), which emphasizes struggle, personal drama and injustice. This analysis is contextualized within mainland China's legacy of socialist realism, which has shaped official narratives and socialist ideology. Laughing to Die employs procedural rhetoric to critique such power structures and amplify silenced voices, particularly those of women enduring generational suffering and systemic oppression.

Second, I explore how the game employs procedural rhetoric and social realism, intertwined with Chinese horror aesthetics, to critique and address issues such as the trafficking of women and domestic violence in contemporary Chinese society. Finally, I argue that indie games like Laughing to Die not only press social issues but also function as grassroots resistance subverting top-down ideological control and capitalist homogenization. This analysis demonstrates social realism games' potential to foster a nuanced public sphere for social critique and collective awareness.

Interrogating Definitions: Indie Games As Social Critique, Procedural Rhetoric and Social Realism in Gaming As Counter-Memory

Indie Games As Social Critique

Laughing to Die, as an indie game, exemplifies a genre that challenges the dominance of commercial AAA games in mainland China's vast gaming industry, one of the largest worldwide (Davies, 2024; Niko Partners, 2023; Statista, 2024) [5]. This genre offers alternative narratives and artistic representations, addressing unresolved social issues and fostering a socially reflective space in a highly censored (Han, 2018; King, Pan, & Roberts, 2017) yet "porous" (Roberts, 2018) media environment.

By navigating this porousness, Chinese netizens frequently "circumvent and challenge state censorship in creative and artful ways" (Han, 2018, p. 4). Similarly, through indirect defiance, these games embed subtle social critiques within gameplay, slipping through the cracks of strict information control (Roberts, 2018). Indie games thus act as platforms for creative resistance, fostering reflection and social awareness while subverting "digital authoritarianism" and protesting "cyber-Leninism" (Chew & Wang, 2021; Creemers, 2017; MacKinnon, 2011). They also challenge state capitalism in mainland China, where powerful businesses are often controlled by an authoritarian elite (Kurlantzick, 2016).

Indie games in China align with global concepts of serious games, which extend beyond entertainment by leveraging "serious play" (Schrage, 1999) to address real-world issues and foster critical thinking, as first conceptualized by Clark C. Abt (1970). Thus, Chinese indie games embrace Galloway's (2006) notion of "countergaming" (p. 109) as a political and cultural avant-garde, employing subversive play for social intervention and activism (Flanagan, 2009), which are, at least partially, rooted in the concept of play as defined by Brian Sutton-Smith (1997).

These indie games also resonate with political games that critique "dysfunctional political practices" (Bogost, 2007, p. 85) and foster civic engagement (Stokes & Williams, 2018) through gameplay (Neys & Jansz, 2019), as well as gaming production and dissemination (Fisher, 2020). Some political games, such as newsgames (Bogost, Ferrari, & Schweizer, 2012), further this purpose by acting as interactive journalism, embedding pressing societal concerns into gameplay to mirror social events and encourage critical engagement.

Procedural Rhetoric

While these frameworks emphasize the seriousness of gaming for addressing social issues, they often overlook what makes games uniquely powerful tools for critique: their reliance on computational systems. Bogost's (2007) concept of persuasive games articulates this distinction, highlighting procedural rhetoric -- rule-based representations and interactions that use computational procedures to communicate ideas. This builds on and elaborates the work of Western media theorists who, since the late twentieth century, have explored games' capacity to persuade and drive societal change through procedurality and rhetorics (Frasca, 2001; Galloway, 2004; McGonigal, 2011; Murray, 1997).

Unlike traditional media, which rely solely on spoken words, text, images, or video, games use systems, rules and mechanics to model complex processes (Bogost, 2007, p. ix). These computational processes surpass verbal and visual rhetoric by not only illustrating "what things are" but simulating "how things work" (Bogost, 2007, pp. 28-29). Through such simulation, procedural rhetoric demonstrates how systematic problems function and presents "reality not as a collection of images or texts, but as a dynamic system that can evolve and change" (Frasca, 2001, p. ix).

Patrick Jagoda (2016) expands on this by identifying games as one of the most potent mediums to "animate concepts, procedures, and processes that make up systems" (p. 181). Through these modelled systems, players engage with virtual worlds and, in doing so, grasp the critiques embedded within the game's rules. Building on these insights, I argue that procedural rhetoric can cultivate a public sphere resilient to media censorship, fostering social satire and critical awareness.

Social Realism in Gaming As Counter-Memory

Procedural rhetoric's capacity to model systems to reflect complex issues empowers games to convey social realism, which Galloway (2006) defines as reflecting "critically on the minutiae of everyday life, replete as it is with struggle, personal drama, and injustice" (p. 75). Galloway (2004) further suggests that achieving such realism requires "fidelity of context," emphasizing a connection between game environments and specific activities familiar to players' social realities (para. 17).

However, entering the gameworld of Laughing to Die as a player, I find that the scenarios do not mirror my real-life experiences of attending funerals. This lack of verisimilitude does not detract me from the game experience; rather, it deepens my immersion in the virtual environment, prompting both critiques of human trafficking and empathy for the victims. My gameplay experience resonates with Galloway's (2004) framework, which asserts that fidelity to life does not require "realistic-ness" (para. 11). He distinguishes the terms "realistic-ness" and "mimetic realism" (para. 20) -- which emphasize a game's realistic style -- from "social realism," which prioritizes social critique and satire.

Paul Martin (2021) expands on Galloway's concept by categorizing realism in gaming into "functional realism" and "perceptual realism" (pp. 715-733). Functional realism equates in-game actions and responses with real-world experiences, commonly found in simulation games. Perceptual realism, on the other hand, aims for visual and auditory authenticity, seeking to replicate real-world sounds and achieve photorealism within the gamespace. Together, these forms of realism aspire to recreate real-life authenticity, aligning with Galloway's mimetic realism.

Although mimetic realism is essential in making players experience real-world scenarios, it does not enhance the social critique, or social realism, in gaming. So, both Galloway and Martin object to over-restoring authenticity in the gamespace. As Martin (2021) critiques, excessive functional realism, with its focus on precision over enjoyment, caters to a niche of hardcore gamers. Similarly, high perceptual realism, which strives to replicate real-world sensory experiences, prioritizes accuracy over artistic expression and thus constrains game artists' creative freedom by limiting their ability to experiment with more imaginative or abstract designs.

Galloway echoes this sentiment, proposing that an overemphasis on realistic-ness in gaming leads to a departure from gaming itself -- as gaming becomes increasingly realistic, it paradoxically drifts away from traditional gaming, shifting more towards simulation or modeling (Galloway, 2004). This indicates that while functional and perceptual realism contribute to realistic-ness, they are not causally linked to fostering social realism (critique) in gaming. Indeed, such hyper-realistic approach might narrow target players, possibly decreasing games' capacity for social critique.

For players like me, if the sole aim were authenticity, I might turn to documentaries, television, or books -- what Marshall McLuhan (1964) defines as passive media -- for a more direct encounter with issues like the trafficking of women. However, videogames, as tools for social critique, offer a distinct advantage. By leveraging procedural rhetoric

-- rule-based systems and interactive mechanics -- games engage players in a more visceral understanding of real-world suffering.

Through these procedural systems, games transform players into participatory "player-historians" (Chapman, 2016) within a "structured story space" (p. 232), where they witness, reconstruct and interact with systems of exploitation and oppression, confronting issues such as gender violence and historical trauma. Laughing to Die exemplifies Galloway's social realism by engaging players in critiquing human trafficking and patriarchal oppression, issues inherently spanning generations and shaping collective memory over time. By connecting players to these memories, the game situates the trafficking within a broader narrative of systemic and inherited injustices, fostering a deeper engagement with these issues.

Expanding on Galloway's framework, games addressing collective memory -- such as Mafia III's portrayal of Jim Crow-era racism, analyzed by Emil Lundedal Hammar (2020) -- function as digital archives of "prosthetic memory" (para. 1), or what Michel Foucault (1977) describes as "popular memory." By reconstructing significant historical events, these games engage with counter-memory, challenging official narratives and recovering marginalized voices suppressed by dominant power structures. They immerse players in the lived experiences of oppressed communities, illuminating the enduring impact of systemic oppression, linking past injustices to present struggles and critiquing hegemonic discourses.

Such subversion in games resonates with theories of resistance from Raymond Williams (1958, 1973, 1974), Antonio Gramsci (1971, 1975, 1978), Michel Foucault (1977, 1988) and Judith Butler (1990). Play, as theorized by Johan Huizinga (1938/1955) and Roger Caillois (1958/2001), creates a "magic circle" where conventional rules are temporarily suspended, allowing for critiquing societal structures and challenging dominant narratives through its inherently ambiguous nature (Sutton-Smith, 1997). This ambiguity fosters "critical play" (Flanagan, 2009), which questions cultural norms and envisions transformative futures, evolving into performative acts that amplify social movements by making serious issues accessible and engaging (Santos & Costanza-Chock, 2020).

Building on these concepts, Laughing to Die exemplifies how games can create immersive spaces that evoke empathy and encourage critical reflection, embodying social realism by critically engaging with the lived experiences of oppression. By leveraging procedural rhetoric and audiovisual design, the game transforms players into active participants who reconstruct narratives of oppression, functioning as a subtle yet potent form of resistance to public opinion control.

While Galloway provides a robust theoretical foundation for social realism in gaming, his framework does not specify the means of achieving it through critical design. Furthermore, his conceptualization is primarily rooted in Western culture, overlooking how social realism might appear in non-Western settings like mainland China, where historical trauma, collective memory and state censorship heavily influence cultural production. This study addresses this gap by examining the ways in which Laughing to Die employs critical design to realize social realism, uncovering the transformative potential of play within the socio-political and cultural dynamics of mainland China.

Social Realism and Subversive Play: Resistance in Mainland China's Gaming Context

Despite China's prominence in the global gaming industry, social realism in gaming remains underexplored, especially in addressing gender-based violence, collective trauma and systemic rebellion. Western scholarship has increasingly examined how games employ procedural rhetoric to build collective memory and critically engage with themes such as war (Chapman, 2016; de Smale, 2019; Pötzsch & Hammond, 2019; Sterczewski, 2016), (post)colonialism and Indigenous representation (Ford, 2016; Mir & Owens, 2013; Mukherjee, 2017; Murray, S., 2017), as well as marginalized identities (Shaw, 2015).

In China, however, state censorship, ideological constraints and the legacy of socialist realism [Shehuizhuyi Xianshizhuyi 社会主义现实主义] restrict games from critiquing power structures, addressing generational trauma and amplifying marginalized voices. Unlike social realism that foregrounds real-world injustices, Chinese socialist realism prioritizes "socialist" ideals over "realism" to promote communist values and an envisioned revolutionary utopia (McGrath, 2010).

This socialist style, dominant in mainland Chinese cinema from the 1950s through the 1980s, evolved from 1930s left-wing Shanghai films that depicted suffering under colonial and capitalist oppression (McGrath, 2010, p. 345). Over time, Chinese socialist realism embraced romanticism, with Communist literary theorist Zhou Yang advocating for a "new realism" that would "move towards reality's future" rather than observe the present (Zhou, 1936/1996, p. 338, as cited in McGrath, 2010, p. 346). In the late 1950s, Mao Zedong solidified this approach by combining "revolutionary realism" with "revolutionary romanticism," blending melodrama and propaganda to inspire visions of a communist future (Mao, 1942/1996, p. 470, as cited in McGrath, 2010, p. 349).

This romanticized approach turned Chinese socialist realism into a "formalistic" propaganda tool, using art and heightened ideological rhetoric to rally citizens around the Party's vision of communism (McGrath, 2010, p. 347). Similar patterns appear in Chinese propagames that promote nationalist goals (Chew & Wang, 2021), including games fostering youth cyber nationalism with embedded nationalistic themes, such as those centered on China's Resistance War against Japan, aligning with the Party-state's political and economic agenda (Harrington & Zhang, 2022; Nie, 2014).

In contrast to these state-aligned games, other games rebel against state-sponsored rhetoric, addressing themes like gender rebellion to amplify marginalized voices. Scholarship highlights "playful activism" (Chess, 2010, p. 13) as gaming capital for spreading progressive politics (Huang & Liu, 2022), gender-swapping mechanics challenging heteronormativity (Huang et al., 2023; Zheng & Li, 2024) and otome games negotiating state restrictions while exploring themes of romance and gender defiance (Lai & Liu, 2023; Wang, 2023; Zhang, 2022). These games counter the male gaze (Ma et al., 2022) and critique sexism in gaming spaces, including esports (Schelfhout et al., 2021).

However, much of this scholarship situates games within China's rapidly growing consumer economy, where players are often framed as "desiring subjects" (Rofel, 2007) or "consumer-citizens" (Tian & Dong, 2011). This lens often emphasizes gender as an identity construct, overlooking the systemic problems of women's generational suffering as human beings. Additionally, in mainland China, games addressing political dissent, human rights abuses and historical critiques are constrained by state restrictions on sensitive topics (Han, 2018; King, Pan, & Roberts, 2017; Roberts, 2018).

As Hugh Davies (2022) observes, "activism that emerge within and through videogames rely upon on a governmental acceptance of both videogames and civil dissent," a condition absent in mainland China but more prominent in Sinophone regions like Taiwan and Hong Kong, where games such as Detention [Fan xiao 返校] (Red Candle Games, 2017) and Devotion [Huan yuan 還願] (Red Candle Games, 2019) [6] confront Taiwanese political repression and cultural identity struggles of the 1960s and 1980s while envisioning hopeful futures (Tse, 2022; Wu, 2022). These regions also use gaming to facilitate political activism, as seen during the 2019 Hong Kong protests (Davies, 2022; Ho, 2022; Wirman & Jones, 2020).

Culturally, this study departs from existing research by shifting focus from gaming as a consumer product to its engagement with generational suffering and systemic oppression in mainland China. It examines Laughing to Die, an indie game that counters official narratives to address the gender-based violence of women's trafficking as collective trauma. By confronting the selective archiving of national memory -- often shaped by those in power to exclude feminine experiences (Derrida, 1996; McClintock, 1993) -- Laughing to Die subverts these structures, foregrounding silenced narratives and challenging patriarchal oppression.

Practically, through critical play and analysis from both designer and player perspectives, this study complements Galloway's theoretical framework on social realism in gaming by addressing its lack of specificity regarding the means through which critical design can achieve social realism, particularly within non-Western context. By juxtaposing Galloway's concept of social realism with the romanticized struggles characteristic of Chinese socialist realism, this study examines the nuances of adapting Western theoretical frameworks to the unique cultural and socio-political context of mainland China. Through an analysis of Laughing to Die's use of procedural rhetoric and Chinese horror aesthetics, the research demonstrates how game design transcends cultural boundaries to create immersive spaces that evoke empathy and foster public discourse, critiquing dominant power structures through narratives of women's trafficking and domestic violence.

Overall, this study contributes to the emerging field of non-Western game studies (Chew, 2022; Davies, 2024; Penix-Tadsen, 2016, 2019; Rayna & Striukova, 2014; Wolf, 2015) and addresses the gap in research on non-commercial gaming in mainland China. While China is a dominant force in the global videogame industry (Chew, 2019, 2022; Jin, 2010; Zhang, 2015), indie games like Laughing to Die remain underexplored, especially in their potential to navigate state censorship and tackle resistance, gender and collective trauma. This study thus underscores the transformative potential of gaming as a medium for social critique in highly regulated cultural and political contexts.

Procedural Rhetoric in Laughing to Die: Exploring Embedded Social Critique Through Spatial Narrative and Puzzle Mechanics

Procedural rhetoric is a distinctive feature of videogames that sets them apart from other new media forms like animation, film and video in terms of achieving persuasiveness. Videogames employ procedural rhetoric not only to depict the world but also to simulate how it works. Through procedural representations, games generate moving images and sounds that simulate actual or imagined physical and cultural processes, thereby creating interactive spaces. Within these spaces, player engagement is required to fulfill the procedural narratives, allowing players to deeply experience real-world issues.

In Laughing to Die, players navigate the game's procedural narratives by embodying what Henry Jenkins (2002) describes as an "embedded spatial narrative" achieved by a series of evocative puzzles, each serving as a clue to the grandmother's past. The initial level presents an old black-and-white photograph of a beaming little girl flanked by two adults, their faces absent, suggesting a family portrait yet obscuring identity. The subsequent level reveals a torn photo, one half showing a tearful woman, the other a face smeared by black ink.

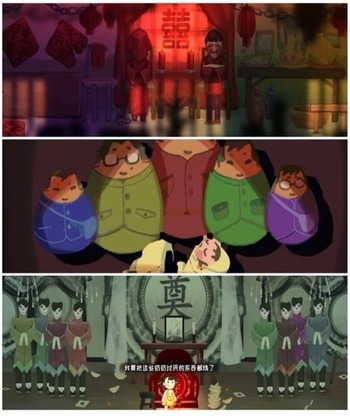

Figure 2. Puzzle examples from each level of the game.

By the third level, the mood shifts with a birthday candle, traditionally a symbol of wishes and future hopes, but here, a note underscores that such wishes are mere echoes of the past. The fourth clue is another candle, this time for prayer, indicating the grandmother's devotion, spending hours in supplication. A shift in narrative tone is evident by level five, where a rabbit doll accompanies a birthday message of "Happy sixteenth birthday to our baby girl!" for a sixteen-year-old, hinting at a rite of passage.

Level six presents an unsettling tableau: five male clay figures surrounding a shattered female counterpart. The accompanying message -- "The male clay dolls seem like my father and uncles. However, why is the female doll broken?" -- encourages players to question the female figure's downfall amidst the males' eerie smiles. Level seven's clue reveals a honey date, paired with a note reflecting childhood memories: "When I was a little girl, I hated bitterness. So, whenever I had to take bitter medicine, my mom would give me a honey date to comfort me." The eighth clue is a worn ceramic bowl associated with traditional Chinese medicine, possibly suggesting attempts to treat an enigmatic ailment.

These clues culminate in a powerful final sequence where the player, embodying the girl avatar, offers her grandmother the toffee she clutched during the opening cut-scene. This act, combined with the decreased grandmother lying on her shattered bed, serves as a symbolic gesture of closure. In the mourning hall, the collected items are thrown into flames at the grandmother's request, possibly emphasizing her rejection of her surroundings. Amidst the blaze, the grandmother's final request materializes: "I want to go home," revealing a lifetime of unresolved pain and longing.

Figure 3. A screenshot of level five.

As players solve the nine clues within Laughing to Die by navigating between gamespaces, the grandmother's obscured history gradually becomes clearer: she was an outsider to the rural village, once part of a loving family that cherished her. Her mysterious absence on her sixteenth birthday left a void, depicted at level five where her mother mourns beside an unopened birthday present.

While the puzzles and narrative fragments unfold during gameplay -- blurred identities, fragmented photographs and a shattered female doll -- these symbolic elements suggest broader themes of systemic gender violence. The grandmother's absence on her sixteenth birthday hints at a forced marriage after being trafficked, with the man from the level two photograph emerging as her abuser, husband and the father of her six children -- represented by the clay figures at level six. It is important to clarify, however, that these interpretations arise from the game's symbolic design and implicit narrative strategies shaped by China's censored media environment.

The game's design employs puzzles and spatial storytelling, engaging players in the process of discovery while circumventing overt political statements on human trafficking. This indirect approach creates a covert arena for social commentary, bypassing the risks associated with direct criticism in politically sensitive contexts. The dichotomy between the game's upper and lower realms juxtaposes the grandmother's oppressive reality against the innocence of her childhood, underscoring her shattered dreams and the despair she endured.

The game's most striking irony appears in its conclusion, as the girl avatar witnesses the family celebrating the grandmother’s death instead of mourning her suffering. This contrast leaves players with a lingering sense of the grandmother's tragedy, reinforcing the broader societal critique the game so subtly yet effectively presents.

Social Realism via Audiovisual Effects: Engaging with Personal and Collective Trauma of Trafficked Women in Rural China

Laughing to Die employs game mechanics to navigate players through a narrative exploration of the grandmother's suffering, leveraging the unique procedural rhetoric of digital gaming. Such procedurality sets the game apart from documentaries or life simulators, highlighting the medium's ability to engage players interactively. Furthermore, by rendering a familiar environment strange and thought-provoking through carefully crafted audiovisual effects, the game fosters social realism. This strategy deepens player engagement while providing a nuanced platform to address human trafficking, navigating the topic with subtlety to circumvent direct political confrontation.

The concept of distancing players from familiar real-world environments to create a persuasive, illusionary space aligns with Geoff Kaufman and Flanagan's (2015) research on "prosocial games" (para. 8). They argue that replicating real-life scenarios too directly within a game can diminish its persuasive impact. Instead, a "psychologically embedded' approach" -- where serious issues are interwoven with abstract or fantastical elements -- helps dismantle players' psychological defenses, providing a more approachable context for engaging with and reflecting on critical themes, such as human trafficking.

Psychological reactance theory, as proposed by Sharon S. Brehm and Jack W. Brehm (1981), illustrates such defense mechanisms as "a threat to or loss of a freedom [that] motivates the individual to restore that freedom. Thus, the direct manifestation of reactance is behavior directed toward restoring the freedom in question" (p. 4). In gaming, presenting realism in a didactic manner by closely mirroring real-world situations may be perceived as overemphasizing the game designers' authority. This approach may lead players to feel preached at rather than engaged, with their sense of freedom or agency feeling compromised or threatened. Such a reaction might prompt players to resist the intended message as a way to preserve their autonomy within the game experience.

In the game, this distancing approach works effectively from two perspectives:

Cultural and Class Inclusivity: Distancing can bridge cultural and class divides, fostering a shared experience among players from diverse backgrounds. Galloway (2004) observed that perceptions of realism vary based on personal and geopolitical contexts. For instance, an American youth may not perceive the game Special Force (Hizbullah Central Internet Bureau, 2003) as realistic, whereas a Palestinian youth in the occupied territories might (Galloway, 2004). Drawing from Henri Tajfel and other's (1979) social identity theory, individuals tend to emphasize distinctions between their own group (in-group) and others (out-group), often "exaggerating these differences" (pp. 56-65). Thus, Laughing to Die's use of distancing broadens its thematic reach, avoiding a literal depiction of trafficking while preserving its critique of systemic issues.

Navigating Media Restrictions: In regions with stringent media controls like mainland China, distancing allows designers to embed sensitive topics like human trafficking and domestic violence within abstracted and fantastical modes of representation. This strategy enables implicit critique while avoiding direct confrontation with censorship. By incorporating familiar objects into a defamiliarized gamespace, designers can navigate regulations such as those imposed by the National Press and Publication Administration (NPPA), which prohibits content promoting cults, superstitions, or material seen as disrupting social order or undermining social stability -- restrictions aligned with the Party's ideological principles (NPPA, 2016) [7].

Figure 4. A screenshot for showcasing the game's visual style.

In the game, designers utilize audiovisual elements to subtly address the issue of human trafficking. The soundtrack varies, using warm tones to recall the grandmother's peaceful childhood, while darker, mournful sounds featuring the suona -- a traditional Chinese instrument -- underscore her subsequent suffering in that rural village.

Visually, the game employs a mix of realistic anime and expressionist art styles to portray Chinese horror aesthetics, such as blood-red lanterns and pale brides, creating a fantastical environment that feels "strange" to the player. This estrangement aligns with Sigmund Freud's (1919/1955) concept of "the uncanny," fostering a sense of uncertainty about the reality of the gameworld. This design effectively distances players from the game's social critique, embedding it within a layer of fantasy.

Dolls -- Symbols of the Uncanny and Unfeeling

In Laughing to Die, the designers employ doll imagery to invoke feelings of the uncanny and to estrange, evoking discomfort and anxiety in players. As Dani Cavallaro (2000) notes, dolls, representing "materiality and corporeality," blur the boundary between the animate and the inanimate, linking material existence with Freud's (1919/2003) concept of "inanimate objects" (p. 105).

In the game, red-clad matrimonial dolls depict a wedding; the female doll is bound in chains beneath her bridal veil, while the male doll displays a disconcerting grin. This imagery can be interpreted as a metaphor for the grandmother's coerced wedding night, with the chains representing both her longing for freedom and her ultimate subjugation. As the game progresses, chains reappear frequently, symbolizing the grandmother's lifelong enslavement, contrasting the grandmother's once joyful youth with the abuse and terror that defined her subsequent years.

Figure 5. Doll elements in the game.

In level six, there are six clay dolls depicting familial male figures and a fragmented little girl doll, which might imply the guardianship of a societal structure that favors sons over daughters. The clay dolls probably represent the girl avatar's father and uncles, along with an unidentified little girl. The other five male dolls stare insidiously at the broken baby girl doll with arrogant and indifferent smiles. As males, they appear to despise and objectify females, treating them as commodities to be sold for money or exchanged for other benefits. The scene invokes practices like bride buying, forced marriages and female trafficking remain prevalent in remote Chinese rural areas (Gates, 1996).

Following the above clues, the broken baby doll might be the grandmother's little daughter. The baby girl doll was broken, possibly because she was sold as a "child bride" [tongyangxi 童养媳] sold for money to raise sons, or subjected to a sorrowful demise in her youth. This depiction critiques a system that commodifies women. The ninth level introduces paper dolls, a component of Chinese funeral rites, symbolizing the afterlife's servants, or "substitutes" [tishen 替身], for the deceased. This element further accentuates the entrenched disregard for female autonomy and agency within the narrative's cultural context.

Chinese Folk Culture -- Deified Male Family Leaders and Ghostified Female Members

In addition to using dolls to make strange, this game employs supernatural elements from Chinese folklore to contextualize modern social issues, blending the supernatural with the natural and tangible aspects of the human world. The game begins with the avatar girl encountering a ghostly figure resembling her grandmother, who guides her through the funeral, possibly to fulfill her unachieved desire to go home. As the narrative unfolds, the game reveals the grandmother's suffering was known but ignored by her family. Her father's dismissive behavior -- his yelling "Your mother was so worried about your disappearing. She was afraid that you got trafficked. Go out!" -- towards the avatar girl implies his disregard for women, his daughter and, by extension, his mother. Despite growing up in a household where his mother was visibly oppressed, his silence on her trafficking speaks volumes about his complicity.

The game's design prompts skepticism about the grandmother's actual age, as the celebratory tone of her centenarian funeral seems to conceal a reality marked by suffering. However, the narrative does not explicitly confirm this. The husband's presence is minimal yet symbolically potent, portrayed not as an individual with personal depth but as a recurring symbol of control and authority. His depiction as a faceless figure in the blacked-out family photo (level two) and the doll-like bridegroom (level four) reduces him to a representation of systemic power rather than a fully developed character. This abstraction shifts focus from personal conflict to broader social critique, emphasizing how patriarchal systems enforce control through erasure, anonymity and ritualistic roles rather than individual relationships.

The symbolic clues in the game suggest the grandmother's plight is not an isolated tragedy but part of a broader generational trauma. For instance, the broken girl doll at level six might represent the grandmother's sixth child, who either died young or was sold as a "child bride." Though the game does not explicitly express the critique of human trafficking and patriarchy, it allows players to infer these systemic injustices through its symbolic elements.

Figure 6. The girl avatar weeping over her grandmother's coffin.

Players can infer that the deified male family leader is the source of all the grandmother's misery. But players cannot assert he is the direct cause of the grandmother's death and prove that the grandmother did not die in her hundreds. This doubt about the grandmother's actual age further heightens the irony of this celebratory funeral in the game's climactic scene -- the avatar girl's solitary grief beside her grandmother's grave contrasts starkly with the celebratory funeral. She cried because she could not help her grandmother finish her last wish to return home. The father retorts: "Stupid child, the grandmother's home is here!" This moment resonates with me as a player, making me wonder if the crying symbolizes a collective lamentation over the entrenched injustices faced by women.

Figure 7. Chinese folk culture elements in the game.

While Laughing to Die does not confirm the grandmother's age or cause of death, it presents enough symbolic elements to highlight the profound suffering she endured. In the game, clues such as level four's prayer candles suggest her devout worship was a desperate search for relief [8]. Isolated after being trafficked into a rural village, the grandmother was left without familial support, turning to faith as her only solace. Yet, the narrative suggests her devotion did not alleviate her trauma but coexisted with repeated cycles of abuse and forced motherhood, scarring both physically and psychologically.

The game's depiction of traditional remedies further emphasizes this suffering. In level eight, a worn ceramic bowl for Chinese medicine implies unsuccessful attempts to treat her distress, while exorcism charms at level six suggest the community attributed her psychological pain to spiritual causes rather than seeking proper care. These symbols critique rural superstitions where unexplained illnesses are often met with violent rituals rather than medical treatment.

In essence, Laughing to Die opts for abstraction over direct representation to invoke social critique and universal empathy. Bogost (2007) asserts that abstraction is vital for creating resonance in videogames, with meaning arising "not through a re-creation of the world, but through selectively modeling appropriate elements of that world" (pp. 45-46). The game employs procedural rhetoric through rule-based mechanics, guiding players through a constructed narrative of the grandmother's life, marked by moments of joy and suffering.

Meanwhile, the game's audiovisual design, including folk elements and the symbolism of dolls, creates a layer of estrangement. Such distancing and defamiliarization not only immerse players in the game's world but also strategically embed the politically sensitive discussion of women trafficking into a fantasy world as "an implicit criticism of society" (Lindstrom, 1994, p. 86), a feature that Laughing to Die harnesses to subtly challenge social injustices.

Indie Games with Social Realism in Mainland China: Grassroots Resistance to Media Censorship and Capital Hegemony

In China, as Davies (2024) observes, the focus on larger commercial game producers often makes the country's videogame industry appear "homogenous and uniform" (p. 76). However, indie games like Laughing to Die, rooted in social realism, are gaining recognition for their "desires for artistic expression [and] creative autonomy," offering ways to navigate "the dual challenges of neoliberal capitalism on one side and party-state disciplinary power on the other" (p. 87). These developers take a grassroots approach, using digital storytelling to amplify marginalized voices often excluded from public discourse (Anthropy, 2012; Hammar, 2017, 2019, 2020; Westecott, 2013). By doing so, they foster a virtual space for addressing topics overlooked by mainstream narratives, highlighting struggles that are frequently neglected or forgotten.

For instance, When the Train Whistles for Three Seconds [Danghuoche mingdi sanmiao 当火车鸣笛三秒] (Guicangguan Studio, 2021) and Cricket Chirping [Chongming 虫鸣] (Shenzhen Chuangyuan Mutual Entertainment Science and Technology Ltd, 2022) confronts human trafficking, while Building 6 Room 301 [6 Dong 301 Fang 6 栋 301 房] (Inter Frame Studio, 2022) explores the experiences of Alzheimer's patients. This game adopts the perspective of the elderly, integrating maze-like exploration, puzzle-solving and impaired vision to emulate the sensory and cognitive impairments of the disease.

In a similar vein, Chinese Parents [Zhongguoshi jiazhang 中国式家长] (Moyuwan Games, 2018) offers a child-rearing simulator that critiques traditional Chinese parenting styles and their impact on familial relationships, advocating for mutual understanding. Nobody: The Turnaround [Daduoshu 大多数] (U. Ground Game Studio, 2022) functions as a life simulator, highlighting the trials and tribulations faced by the modern Chinese working youth. A Perfect Day [Wanmeide yitian 完美的一天] (Perfect Day Studio, 2019) takes players through the societal transformation of 1999, focusing on the overhaul of state-owned enterprises and its consequences on workers, the surge in entrepreneurship and tales of families navigating this era of change.

Despite their cultural significance, these indie games face several obstacles, including underdeveloped business models, rampant piracy and stringent state regulations. Unlike dominant gaming corporations like Tencent and Netease (Davies, 2024) [9], which prioritize profit by promoting "pay-to-win" mechanics [kejin 氪金] or focus solely on profit by "reproducing or reskinning market-proven profitable games" (p. 77), indie games are typically crafted with limited budgets and driven by artistic, creative and social imperatives rather than purely commercial success. This emphasis on niche audiences further complicates securing investment.

Furthermore, the absence of robust legal support leaves independent creators vulnerable to intellectual property infringements, diminishing their market share in the world's largest Chinese gaming industry. In 2018, indie games represented a mere fraction of China's gaming revenue. According to a report by China Economic Net, based on data analyzed by Gamma Data, the domestic market size for Chinese indie games in 2018 was approximately 210-million-yuan, accounting for only 0.1% of the overall gaming market size (Huxiu.com, 2022). The pervasiveness of game piracy exacerbates this revenue shortfall, underscoring the precarious position of indie games within the broader gaming economy.

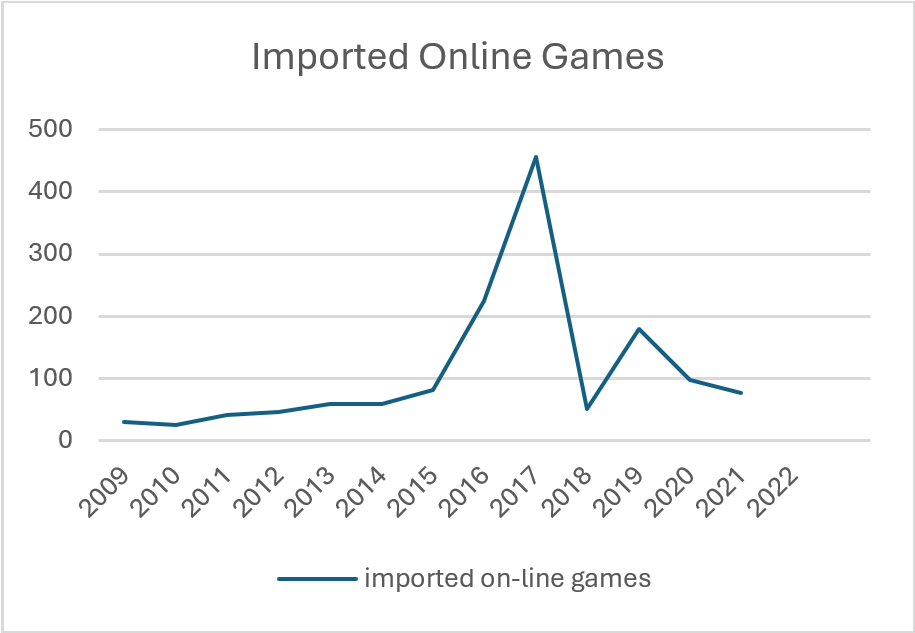

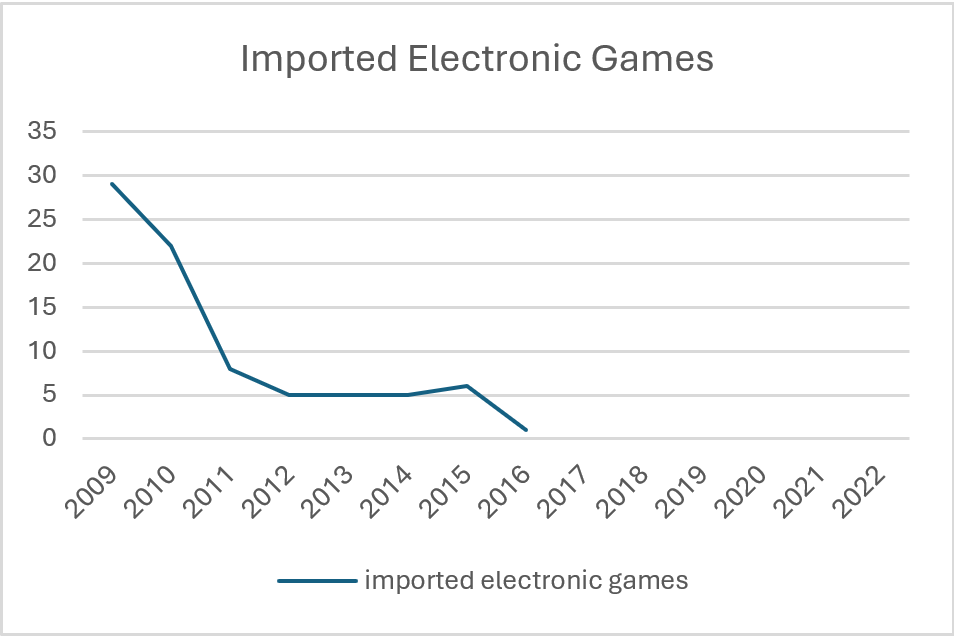

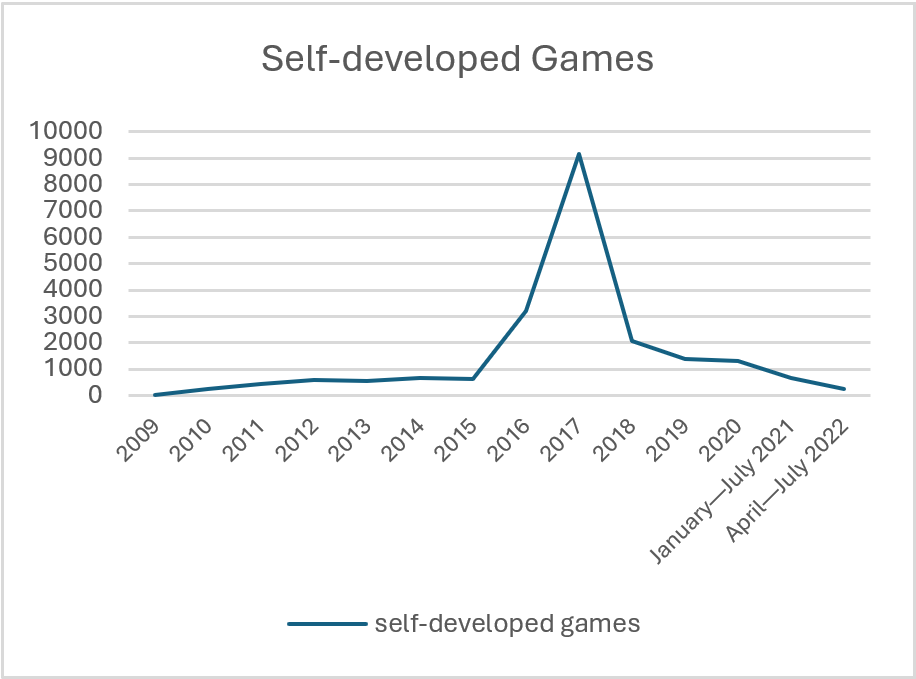

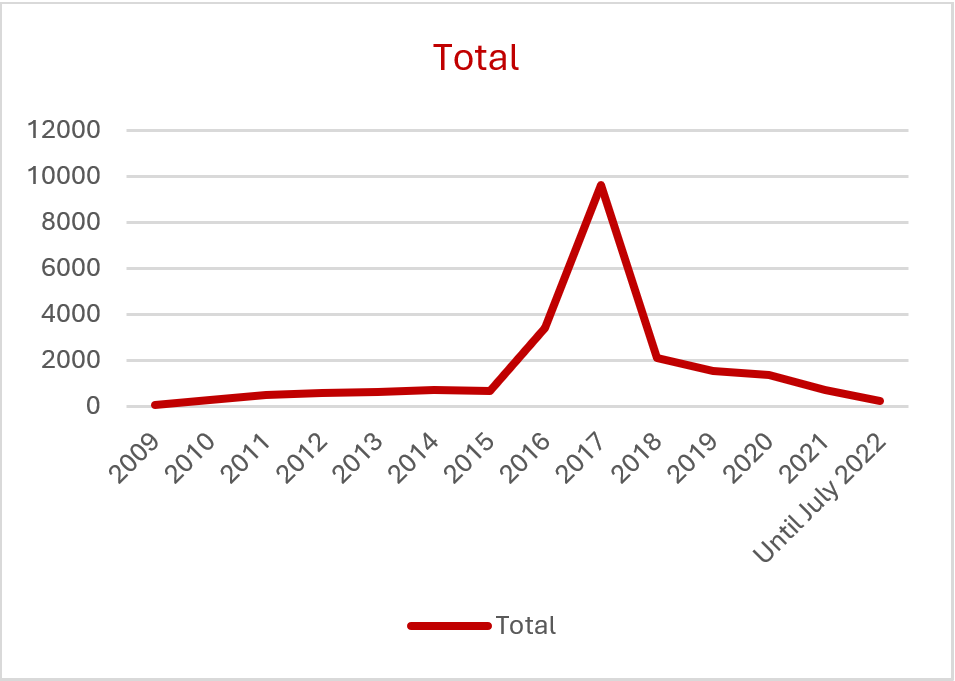

Moreover, indie game developers in China encounter significant difficulties in obtaining publishing licenses (Davies, 2024) [10], a process heavily influenced by state regulations and ideological concerns, as highlighted by Qiaolei Jiang and Anthony Y.H. Fung (2019). The Chinese government's stringent policies [11], which include halting new game licenses, limiting minors' gaming time and enforcing stricter content censorship, have imposed stricter controls on the videogame industry from 2018-2021. Such control has particularly impacted the proliferation of social realism games (see the Appendix for statistics on licensed and published games since 2009 from the National Press and Publication Administration website).

Securing game licenses is notably more challenging for indie games with social realism meaning than for larger companies, a situation that has become particularly pronounced post-2021. Despite this, such games continue to flourish within fan communities like GCORE, ChengGuang and the China Indie Game Alliance (CiGA). These platforms are invaluable for amateur creators and independent studios, providing the means for artistic and satirical expression within a supportive environment. By skillfully integrating social commentary into game mechanics and aesthetics, these communities enable social realism games to circumvent content censorship to a considerable degree.

As Davies (2024) notes, "Chinese Communist Party (CCP) restrictions upon videogame publishing and play, while frustrating for many independents, are also understood by individuals in these communities as a necessary and well-intentioned barrier preventing highly commercial games from entirely dominating the market" (p. 76). In other words, government restrictions, while limiting, have unintentionally created a space for creative game-making to flourish. This perspective supports my argument that indie games with a focus on social critique possess significant potential as grassroots resistance to the constraints of mainland China's media environment and capital hegemony. These games demonstrate their capacity to navigate both regulatory and financial challenges while fostering meaningful social engagement and critique.

Conclusion

In this article, by analyzing the indie game Laughing to Die, I posit that achieving social realism in gaming does not depend on the realistic-ness and authenticity of the milieu but on procedural rhetoric and the social realism of audiovisual effects. Designers conceal politically sensitive critiques in game mechanics and audiovisual design. Players are led procedurally to move around the gamespace, trigger clues by solving puzzles and repair the grandmother's miserable trafficking experience. Through this spatial narrative, players gain autonomy for self-exploration to explore and contemplate the socio-political issues presented -- human trafficking.

The integration of Chinese horror aesthetics -- the folk soundtrack of suona, blood-red decors, ghostly apparitions, pale and miserable brides and ritualistic symbols -- effectively merges the supernatural with the natural human life, crafting a "Chineseness" in a distancing gamespace. This creative distancing dismantles the psychological defense associated with direct representations, according to Kaufman and Flanagan (2015), thus sharpening the game's critique of human trafficking and drawing attention to marginalized women in rural China, all while navigating the strictures of media censorship. Under capillary surveillance, indie games provide ground for ordinary people's social criticisms and public concerns.

Therefore, Laughing to Die and other indie games are vital in offering a voice for the voiceless and countering the monolithic narratives perpetuated by mainstream gaming. They challenge the homogenization driven by tech giants, providing an alternative to nationalistic tropes (Inwood, 2022) and creating space for varied humanistic narratives. Also, it is a refutation of genre clichés existing in the current gaming market -- rampant utopian fairy cultivation games, violent first-person shooters, massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs), multiplayer online battle arena games (MOBAs) and so forth.

Despite facing substantial financial, political and legal restrictions, indie games with social realism persist and thrive within fan communities -- unlicensed yet unfettered in their artistic expression of concerns for vulnerable groups as a voice. As a result, there should be more room for these games to exercise their prosocial power and revitalize their creativity in artistic design and storytelling, allowing them to venture beyond the rigid genres of horror, vintage, science-fiction and puzzle games.

Further academic inquiry into the prosocial and rhetorical powers of videogames is warranted, especially research that considers critical design and the integration of gaming into broader historical and social narratives. From a broader political economy perspective, such scholarship should also consider a subtle balance between state intervention and industry support to stimulate market dynamism and creativity, particularly amidst global economic challenges. Lastly, the discourse on the prosocial impact of Chinese videogames requires a shift from predominantly Western theoretical frameworks towards a decolonized view that embraces East Asian insights. Such media perspectives enrich indie game studies, and contribute toward a more diverse, global understanding of gaming's societal influence.

Appendix

Endnotes

[1] This is a small independent studio consisting of 11 people in total.

[2] As Hill Gates (1996) stated, buying brides is rooted in the historical hierarchy and patriarchy of Chinese society. Additionally, the unbalanced male-to-female ratio of 105.07 (in 2020) and the prevalent poverty in rural areas have made it difficult for Chinese rural males to marry legally. Because not getting married contradicts the Chinese tradition of "continuing the family bloodline" [chuanzong jiedai 传宗接代], buying marriage is a lucrative business and has become a severe social problem threatening women's safety.

[3] In early 2022, a video surfaced on Chinese social media showing a woman named Xiaohuamei [小花梅], dressed in thin clothing and restrained by an iron chain around her neck in a dilapidated hut in Fengxian County, Xuzhou, Jiangsu Province. The footage, which went viral during the Chinese New Year on January 28, revealed her living in squalid conditions and quickly sparked widespread public outrage. It ignited discussions on social media platforms such as WeChat [Weixin 微信], Weibo [微博], Douyin [抖音], Douban [豆瓣] and Zhihu [知乎] about human trafficking and the treatment of women in rural areas. Police confirmed that Xiaohuamei had previously been reported missing in Yunnan Province, and subsequent investigations revealed she was a victim of human trafficking, having been sold into marriage and subjected to years of abuse (BBC, 2022; China Daily, 2022).

[4] Yu Huaying was found guilty of trafficking 17 children from Guizhou and Chongqing, selling them in Hebei Province between 1993 and 1996. Her crimes included abducting siblings from five families, with some children abandoned during transport. In September 2023, the Guiyang Intermediate People's Court sentenced Yu to death. After an appeal and retrial in early 2024, the court upheld the death sentence on 25 October 2024, citing the grave social harm caused by her actions. Yu was also stripped of her political rights for life, and her personal assets were seized (China.org.cn, 2024).

[5] China's gaming market is among the largest globally, with significant revenue and a vast player base. In 2024, the market is projected to generate approximately US$ 94.49 billion in revenue, with an expected compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.11percent from 2024 to 2027, reaching an estimated US$ 119.40 billion by 2027 (Statista, 2024). Additionally, the number of gamers in China is anticipated to grow from 715.9 million in 2023 to 747.9 million by 2028, reflecting a 5-year CAGR of 0.9 percent (Niko Partners, 2023).

[6] These two games were developed by Red Candle Games, a Taiwanese independent videogame development studio based in Taipei, Taiwan.

[7] From Regulations on Game Publishment of the National Press and Publication Administration: https://www.nppa.gov.cn/bsfw/xksx/cbfxl/wlcbfwspsx/202210/t20221013_600725.html.

[8] In ancient China, people always sought help from the gods when trapped in suffering and diseases. This god-worshipping convention was mostly abandoned in modern societies but was maintained in the underdeveloped rural countryside.

[9] According to Davies (2024), "Within China, the game market is dominated by two companies, both based in the south of the country. These are Shenzhen-based Tencent with a 51 percent share and Hangzhou-based NetEase with 17 percent" (p. 76).

[10] To publish games in China, publishers must get approval from the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television [SARFT; guojia guangbo dianying dianshizongju 国家广播电影电视总局] and the Ministry of Culture & Tourism [MCT; wenhuahe lvyoubu 文化和旅游部].

[11] Since 2018, the central government has severely controlled the videogame industry. In August 2021, the National Press and Publication Administration [NPPA; guojia xinwen chubanshu 国家新闻出版署] put forward the "Notice on Further Strict Management to Effectively Prevent Minors from Indulging in Online Games." Further, in September, the Central Propaganda Department [CPD; zhonggong zhongyang xuanchuanbu 中共中央宣传部] issued a "Notice on Carrying Out Comprehensive Management in the Field of Culture and Entertainment" to strengthen the intensity of the audit and to promote "moral standards" in games. Accompanying these two stricter addiction-prevention policies, both SARFT and the MCT stopped issuing new licenses [ISBNs or youxi banhao 游戏版号] to game publishers for 263 days since August 2021. These actions have caused a considerable decrease in videogames' circulation in the market and especially, this is a massive strike against indie games, which always include social satire and harsh criticism.

References

Abt, C. C. (1970). Serious games. Viking Press.

Anthropy, A. (2012). Rise of the videogame zinesters: How freaks, normals, amateurs, artists, dreamers, drop-outs, queers, housewives, and people like you are taking back an art form. Seven Stories Press.

BBC. (2022, January 31). Xuzhou mother: Video of chained woman in hut outrages China internet. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-60194080

Bogost, I. (2007). Persuasive games: The expressive power of videogames. MIT Press.

Bogost, I., Ferrari, S., & Schweizer, B. (2012). Newsgames: Journalism at play. The MIT Press.

Bossetta, M. (2019). Political campaigning games. International Journal of Communication, 13, 3422-3443.

Brehm, S. S., & Brehm, J. W. (1981). Psychological reactance: A theory of freedom and control. Academic Press.

Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. Routledge.

Caillois, R. (2001). Man, play, and games (M. Barash, Trans.). University of Illinois Press. (Original work published 1958)

Cao, Y. (2022, February 18). Video of chained woman sparks further probe. China Daily. Retrieved from https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202202/18/WS620f0922a310cdd39bc877f3.html

Cavallaro, D. (2000). Cyberpunk and cyberculture: Science fiction and the work of William Gibson (p. 105). Athlone Press; Distributed in the U.S., Canada, and South America by Transaction Publishers.

Chapman, A. (2016). Digital games as history: How videogames represent the past and offer access to historical practice (p. 232). Routledge.

Chess, S. (2010). How to play a feminist. Thirdspace: A Journal of Feminist Theory & Culture, 9(1). http://journals.sfu.ca/thirdspace/index.php/journal/article/view/273

Chew, M. M. (2019). A critical cultural history of online games in China, 1995-2015. Games and Culture, 14(2), 195-215. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412016661457

Chew, M. M.-T., & Wang, Y. (2021). How propagames work as a part of digital authoritarianism: An analysis of a popular Chinese propagame. Media, Culture & Society, 43(8), 1431-1448. https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437211029846

Chew, M. M. (2022). The significance and complexities of anti-corporate gamer activism: Struggles against the exploitation and control of game-worlds in 2000s China. Games and Culture, 17(4), 487-508. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120211042259

China.org.cn. (2024, October 25). Woman sentenced to death for trafficking 17 children [Original report by Xinhua]. Retrieved from https://www.china.org.cn/china/2024-10/25/content_117507599.htm

Creemers, R. (2017). Cyber-Leninism. In M. Price & N. Stremlau (Eds.), Speech and society (pp. 255-273). Cambridge University Press.

Dajili Studio. (2022). Laughing to Die [Xisang 喜丧] [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game designed by Binye, published by Gamera Games. https://www.gcores.com/games/85631

Davies, H. (2022). The revolution will not be gamified: Videogame activism and playful resistance across the Sinophone. British Journal of Chinese Studies, 12(2), 76-100. https://doi.org/10.51661/bjocs.v12i2.200

Davies, H. (2024). Independent game production in Southern China. Media Industries, 11(1), 75-96. https://doi.org/10.3998/mij.3914

Derrida, J. (1996). Archive fever: A Freudian impression (E. Prenowitz, Trans.). The University of Chicago Press.

de Smale, S. (2019). Ludic memory networks: Following translations and circulations of war memory in digital popular culture (PhD thesis). Utrecht University.

Fisher, J. (2020). Digital games, developing democracies, and civic engagement: A study of games in Kenya and Nigeria. Media, Culture & Society, 42(7-8), 1309-1325. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443720914030

Flanagan, M. (2009). Critical play: Radical game design. The MIT.

Ford, D. (2016). "eXplore, eXpand, eXploit, eXterminate": Affective writing of postcolonial history and education in Civilization V. Game Studies, 16(2). http://gamestudies.org/1602/articles/ford

Foucault, M. (1977). Intellectuals and power. In D. F. Bouchard (Ed.), Language, counter-memory, practice: Selected essays and interviews (pp. 205-217). Cornell University Press.

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison (A. Sheridan, Trans.). Pantheon Books.

Foucault, M. (1977). Language, counter-memory, practice: Selected essays and interviews (D. F. Bouchard, Ed.). Cornell University Press.

Foucault, M. (1988). Politics, philosophy, culture: Interviews and other writings, 1977-1984 (L. D. Kritzman, Ed.). Routledge.

Frasca, G. (2001). Videogames of the oppressed: Videogames as a means for critical thinking and debate. Georgia Institute of Technology. http://hdl.handle.net/1853/17657

Freud, S., McLintock, D., & Haughton, H. (2003). The uncanny. Penguin Books. (Original work published 1919)

Freud, S., & Strachey, J. (Ed.). (1955). The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. XVII. Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1919)

Galloway, A. R. (2004). Social realism in gaming. Game Studies, 4(1). http://www.gamestudies.org/0401/galloway/

Galloway, A. R. (2006). Gaming: Essays on algorithmic culture. University of Minnesota Press.

Gates, H. (1996). Buying Brides in China-Again. Anthropology Today, 12(4), 8-11. https://doi.org/10.2307/2783507

Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the prison notebooks (Q. Hoare & G. Nowell-Smith, Eds. and Trans.). International Publishers.

Gramsci, A. (1975). Prison notebooks, volume 1. Columbia University Press.

Gramsci, A. (1978). The modern prince and other writings. International Publishers.

Guicangguan Studio. (v. 1.2.4, 2023) [2021]. When the Train Whistles for Three Seconds [Danghuoche mingdi sanmiao 当火车鸣笛三秒] [Apple Mac OS]. Digital game designed by Huan Liu, published by MedusasGame.

Hammar, E. L. (2017). The political economy of historical digital games. Media Development, 64(4), 25-28. https://www.academia.edu/35232762

Hammar, E. L. (2019). The political economy of cultural memory in the videogames industry. Digital Culture & Society, 5(1), 61-84. https://doi.org/10.14361/dcs-2019-0105

Hammar, E. L. (2020). Playing virtual Jim Crow in Mafia III: Prosthetic memory via historical digital games and the limits of mass culture. Game Studies, 20(1). https://gamestudies.org/2001/articles/hammar

Hammond, P., & Pötzsch, H. (Eds.). (2019). War games: Memory, militarism and the subject of play. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Han, R. (2018). Contesting cyberspace in China: Online expression and authoritarian resilience. Columbia University Press.

Harrington, J., & Zhang, Z. (2022). Negotiating Chinese youth cyber nationalism through play methods. British Journal of Chinese Studies, 12(2), 114-132. https://doi.org/10.51661/bjocs.v12i2.197

Hizbullah Central Internet Bureau. (2003). Special Force [Microsoft Windows]. Sunlight.

Ho, C. J. H. (2022). Civil disobedience in the era of videogames: Digital ethnographic evidence of the gamification of the 2019-20 extradition protests in Hong Kong. British Journal of Chinese Studies, 12(2), 101-113. https://doi.org/10.51661/bjocs.v12i2.187

Huang, V. G., & Liu, T. (2022). Gamifying contentious politics: Gaming capital and playful resistance. Games and Culture, 17(1), 26-46. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120211014143

Huang, Y., Liu, T., & Chen, Y. (2023). The (unlocated) in-game gender performativity in contemporary China: Exploring gender swapping practices in the online game sphere. Feminist Media Studies, 24(7), 1617-1634. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2023.2258296

Huizinga, J. (1955). Homo ludens: A study of the play-element in culture (First Beacon Paperback ed.). Beacon Press. (Original work published 1938)

Indie 独闻. (2018). The Making of Chinese Indie Games (Part 1): The Flourishing of Chinese Indie [独立游戏的中国制造(一):雨后春笋般的中国独游]. Huxiu. Retrieved from https://www.huxiu.com/article/601995.html

Inter Frame Studio. (v.1.5, 2023) [2022]. Building 6 Room 301 [6 Dong 301 Fang 6 栋 301 房] [Microsoft Windows]. Videogame published by Gamera Games.

Inwood, H. (2022). Towards Sinophone game studies. British Journal of Chinese Studies, 12(2), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.51661/bjocs.v12i2.219

Jagoda, P. (2016). Network aesthetics. The University of Chicago Press.

Jagoda, P. (2020). Experimental games: Critique, play, and design in the age of gamification. The University of Chicago Press.

Jenkins, H. (2002). Game design as narrative architecture. Retrieved from https://web.mit.edu/~21fms/People/henry3/games&narrative.html

Jian, D. (2022). The Ideological pedigree of Contemporary Chinese Game History: From Local Modernization to Capital and Market Logic. Discovery and Contention.

Jiang, Q., & Fung, A. Y. H. (2019). Games With a Continuum: Globalization, Regionalization and the Nation-State in the Development of China's Online Game Industry. Games and Culture, 14(7-8), 801-824. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412017737636

Jin, D. (2010). Korea' s online gaming empire. MIT Press.

Kaufman, G., & Flanagan, M. (2015). A psychologically 'embedded' approach to designing games for prosocial causes. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 9(3), Article 5. http://doi.org/10.5817/CP2015-3-5

King, G., Pan, J., & Roberts, M. E. (2017). How the Chinese government fabricates social media posts for strategic distraction, not engaged argument. American Political Science Review, 111(3), 484-501. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000144

Kurlantzick, J. (2016). State capitalism. Oxford University Press.

Lai, Z., & Liu, T. (2023). "Protecting our female gaze rights": Chinese female gamers' and game producers' negotiations with government restrictions on erotic material. Games and Culture, 19(1), 3-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120231151300

Lindstrom, N. (1994). Twentieth-century Spanish American fiction. University of Texas Press.

Ma, Y., Zhang, Z., & Gao, J. (2022). The politics of gender in the video game culture in China. In Proceedings of the 2022 5th International Conference on Humanities Education and Social Sciences (ICHESS 2022) (pp. 1489-1495). Atlantis Press. https://doi.org/10.2991/978-2-494069-89-3_230

MacKinnon, R. (2011). China's "networked authoritarianism." Journal of Democracy, 22(2), 32-46.

Mao, Z. (1996). Talks at the Yan'an forum on literature and art. In K. A. Denton (Ed.), Modern Chinese literary thought: Writings on literature, 1893-1945 (pp. 458-484). Stanford University Press.

Martin, P. (2021). Realism in play: The uses of realism in computer game discourse. In D. Götsche, R. Mucignat, & R. Weninger (Eds.), Landscapes of Realism: Rethinking Literary Realism in Comparative Perspectives (pp. 715-733). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

McClintock, A. (1993). Family feuds: Gender, nationalism and the family. Feminist Review, 44(1), 61-80. https://doi.org/10.2307/1395196

McGonigal, J. (2011). Reality is broken: Why games make us better and how they can change the world. Jonathan Cape.

McGrath, J. (2010). Cultural revolution model opera films and the realist tradition in Chinese cinema. The Opera Quarterly, 26(2-3), 343-376. https://doi.org/10.1093/oq/kbq016

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding media: The extensions of man. McGraw-Hill.

Mir, R., & Owens, T. (2013). Modeling Indigenous peoples: Unpacking ideology in Sid Meier's Colonization. In M. Kapell & A. B. R. Elliott (Eds.), Playing with the past: Digital games and the simulation of history (pp. 91-106). Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Moyuwan Games. (v. 1.0.9.7, 2018). Chinese Parents [Zhongguoshi jiazhang 中国式家长] [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game designed by Liu Zhenhao and Yang Geyilang, published by Littoral Games.

Mukherjee, S. (2017). Videogames and postcolonialism: Empire plays back. Palgrave Macmillan.

Murray, J. (1997). Hamlet on the holodeck: The future of narrative in cyberspace. MIT Press.

Murray, S. (2017). The poetics of form and the politics of identity in Assassin's Creed III: Liberation. Kinephanos - Journal of Media Studies and Popular Culture, (Special Issue), 77-102.

National Press and Publication Administration. (2016). The audit results of imported and self-developed games receiving licenses and publications. Retrieved from https://www.nppa.gov.cn/nppa/channels/317.shtml

Neys, J., & Jansz, J. (2019). Engagement in play, engagement in politics: Playing political video games. In The playful citizen (pp. 55-72). Amsterdam University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9789048535200-003

Nie, H. A. (2014). Gaming, nationalism, and ideological work in contemporary China: Online games based on the war of resistance against Japan. In K. Edney, S. Guo, & L. Xu (Eds.), Construction of Chinese nationalism in the early 21st century (pp. 75-93). Routledge.

Niko Partners. (2023). China games market reports series. Niko Partners. Retrieved from https://nikopartners.com/china-games-market-reports/

Penix-Tadsen, P. (2016). Cultural code: Video games and Latin America. MIT Press.

Penix-Tadsen, P. (2019). Video games and the global South. ETC Press.

Perfect Day Studio. (v. 1.3.1, 2023) [2019]. A Perfect Day [Wanmeide yitian 完美的一天] [Microsoft Windows]. Videogame published by Perfect Day Studio.

Pötzsch, H. (2015). Selective realism: Filtering experiences of war and violence in first- and third-person shooters. Games and Culture, 12(2), 156-178. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412015587802

Rayna, T., & Striukova, L. (2014). 'Few to many': Change of business model paradigm in the video game industry. Digiworld Economic Journal, (94), 61-81. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2534019

Red Candle Games. (2017). Detention [Fanxiao 返校] (standard edition) [Apple iOS game]. Digital game designed and published by Red Candle Games.

Red Candle Games. (2019). Devotion [Huanyuan 還願] (standard edition) [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game designed and published by Red Candle Games.

Roberts, M. E. (2018). Censored: Distraction and diversion inside China's Great Firewall. Princeton University Press.

Rofel, L. (2007). Desiring China: Experiments in neoliberalism, sexuality, and public culture. Duke University Press.

Santos, S. L., & Costanza-Chock, S. (2020). Design justice: Community-led practices to build the worlds we need. MIT Press.

Schelfhout, S., Bowers, M. T., & Hao, Y. A. (2021). Balancing gender identity and gamer identity: Gender issues faced by Wang 'BaiZe' Xinyu at the 2017 Hearthstone Summer Championship. Games and Culture, 16(1), 22-41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412019866348

Schrage, M. (1999). Serious play: How the world's best companies simulate to innovate. Harvard Business School Press.

Shaw, A. (2015). The tyranny of realism: Historical accuracy and the politics of representation in Assassin's Creed III. Loading..., 9(14). http://journals.sfu.ca/loading/index.php/loading/article/view/157

Shenzhen Chuangyuan Mutual Entertainment Science and Technology Ltd. (2022). Cricket Chirping [Chongming 虫鸣] [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game designed and published by Shenzhen Chuangyuan Mutual Entertainment Science and Technology Ltd.

Statista. (2024). Video games. Statista. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/outlook/dmo/digital-media/video-games/china

Sterczewski, P. (2016). This uprising of mine: Game conventions, cultural memory, and civilian experience of war in Polish games. Game Studies, 16(2). Retrieved from http://gamestudies.org/1602/articles/sterczewski

Stokes, B., & Williams, D. (2018). Gamers who protest: Small-group play and social resources for civic action. Games and Culture, 13(4), 327-348. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412015615770

Sutton-Smith, B. (1997). The ambiguity of play. Harvard University Press.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33-47). Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Tian, K., & Dong, L. (2011). Consumer-citizens of China: The role of foreign brands in the imagined future China. Routledge.

Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2010). Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychological Review, 117, 440-463. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018963

Tse, J. W. T. (2022). Games as historical representations. British Journal of Chinese Studies, 12(2), 63-69. https://doi.org/10.51661/bjocs.v12i2.188

Ground Game Studio. (2022). Nobody: The Turnaround [Daduoshu 大多数] [Microsoft Windows]. Videogame published by Thermite Games.

Wang, Y. (2023). Virtual love experience in Love and Producer: Exploring perceptions of love, romance and gender in otome game player communities in China. Media and Communication Research, 4(10), 5-11. https://doi.org/10.23977/mediacr.2023.041002

Westecott, E. (2013). Independent game development as craft. Loading… The Journal of the Canadian Game Studies Association, 7(11), 78-91. Retrieved from https://journals.sfu.ca/loading/index.php/loading/article/view/124/153

Williams, R. (1958). Culture and society, 1780-1960. Columbia University Press.

Williams, R. (1973). The country and the city. Oxford University Press.

Williams, R. (1974). Television: Technology and cultural form. Schocken Books.

Wirman, H., & Jones, R. (2020). "Block the spawn point": Play and games in the Hong Kong 2019 pro-democracy protests. In Abstract Proceedings of DiGRA 2020 Conference: Play Everywhere / Papers. Digital Games Research Association. https://dl.digra.org/index.php/dl/article/view/1206/1206

Wolf, M. J. P. (Ed.). (2015). Video games around the world. MIT Press.

Wu, C.-r. (2022). From Detention to Devotion: Historical horror and gaming politics in Taiwan. British Journal of Chinese Studies, 12(2), 46-62. https://doi.org/10.51661/bjocs.v12i2.166

Zhang, D. G. (2015). Parallax view: "Year one" of Chinese game studies? Games and Culture, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412015577044

Zhang, Y. (2022). Analysis of otome mobile game from the perspective of feminism in China. Journal of Social Science and Humanities, 4(10), 58-62. https://doi.org/10.53469/jssh.2022.4(10).11

Zheng, L., & Li, J. (2024). Gender swapping in massively multiplayer online role-playing games in China: Relationship to gender nonconformity and gender dysphoria. Personality and Individual Differences, 233, 112898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2024.112898

Zhou, Y. (1996). Thoughts on realism. In K. A. Denton (Ed.), Modern Chinese literary thought: Writings on literature, 1893-1945 (pp. 338). Stanford University Press.