Radical Digital Fishing: From Minigames to Bad Environmentalism

by Marco CaraccioloAbstract

This article develops an approach to the representation of fishing in video games and its cultural significance in times of ecological crisis. In several games, self-contained fishing “minigames” provide counterpoint to the neoliberal temporalities and pressures involved in mainstream game experiences. My two examples of “radical digital fishing” -- Dave the Diver (Mintrocket, 2023) and Dredge (Black Salt Games, 2023) -- go one step further: they create incongruous situations that defamiliarize players’ imagination of fishing in both the real world and digital gameplay. Dave the Diver does so by combining a satire of the environmental movement with humorous experimentation with various game genres. Meanwhile, Dredge does so by staging the breakdown of human subjectivity as it comes into contact with the weirdness of nonhuman materiality. In this way, I show how modern games resonate with what Nicole Seymour has called “bad environmentalism,” using fishing to disrupt the conventional understanding of the nonhuman of Western modernity.

Keywords: nonhuman, weird, humor, satire, materiality

Introduction

Fishing has long played an outsize role across various video game genres. Just one year after the release of Colossal Cave Adventure (Crowther, 1976) -- seen by many as the urtext of interactive fiction and role-playing games (Barton, 2008) -- William Engel developed a text-based game titled Gone Fishing (1977) for the TRS-80 home computer. Engel’s game lists, in starkly repetitive prose, the player’s location, fishing time and catch [1]. As in Colossal Cave Adventure, the player navigates the gameworld by entering a letter for the cardinal direction they want to move in as part of a six-hour-long fishing trip. That is, essentially, all the challenge that the game offers: the rest is sheer luck.

It is hard to know whether the game is an earnest attempt to simulate fishing in a text-only medium or a satirical take on the repetitiveness of text adventures. What is clear is that, after Engel’s 1977 experiment, fishing became ubiquitous in games, both as a primary focus and as a side activity or game-within-the-game (“minigame”). In addition to numerous fishing simulators, fishing is featured by games that do not seem to require it conceptually or thematically. Sprawling open-world action games such as Red Dead Redemption 2 (Rockstar Games, 2018), roguelikes such as Hades (Supergiant Games, 2018) and numerous survival games from The Forest (Endnight Games, 2014) to Valheim (Iron Gate, 2021) all contain fishing, usually with extremely limited payoffs for the player pursuing quests or simply attempting to “beat” the game. The reasons for this pervasiveness are not straightforward: the cultural perception of angling as a slow-paced, old-school hobby seems to clash with the high-stakes situations and fantastical worlds typically associated with gaming. The attractions of digital fishing might lie in the humorous incongruity generated by this conflict of expectations, as well as the way it challenges a culture of mainstream gaming invested in maximizing gameplay benefits through strategic choices.

In this article, I read digital fishing as a litmus test for human-nonhuman relations and how they are negotiated by contemporary games. Though this negotiation can take profoundly different forms, I focus on innovative games that position fishing as an act of resistance to both mainstream gaming and dominant views of the nonhuman world as passive and available to human exploitation. Nicole Seymour’s (2018) account of “bad environmentalism,” discussed below, captures the subversive potential of what I call radical digital fishing. While ironic critique does not fully explain the near-ubiquity of digital fishing, it does account for some of its appeal across a broad range of genres. As I argue below, the incongruity of digital fishing gives rise to a variety of formal experiments with genre and gameplay conventions, performing a conceptual subversion of Western binaries (particularly nature vs. culture dichotomies).

In game studies, resistance to the values of mainstream gaming culture has often been conceptualized as a clash of temporalities. John Vanderhoef and Matthew Thomas Payne (2022), for example, discuss the slow pace of Red Dead Redemption 2 (Rockstar Games, 2018) as an implicit response to a neoliberal understanding of time, whereby even leisure activities are subject to standards of quantification and productivity. The checklists, scores and achievements that structure the experience of many (if not most) modern games are of course an expression of this hegemonic understanding of temporality. Against the “chrononormativity” of neoliberal culture (Freeman, 2010), Red Dead Redemption 2 deliberately decelerates the player’s progress through its loose open-world structure, long travel times and sections containing very little of the white-knuckled combat for which the Western genre is known. The game incentivizes exploration that is decoupled from tactical gains, creating opportunities for “radical slowness” (Scully-Blaker, 2019) that serves -- Vanderhoef and Payne argue -- as a critique of hegemonic time and the crunch culture in which the game was produced.

In Red Dead Redemption 2, fishing is closely involved in this decelerating dynamic. It is unlocked by a side mission and can be used as a source of sustenance, but there are far more efficient ways of obtaining food in the game. Instead, fishing deepens the relationship between the player character (Arthur Morgan) and the gameworld, inviting players to pay attention to features of the landscape that may otherwise pass unobserved: different types of bait are required by rivers, lakes and marshes. This is of course not unusual in fishing minigames, but the need to adjust fishing practices to the player character’s surroundings takes on special significance with how the game emphasizes exploring a vast and diverse natural environment.

As Leon Xiao (2023, p. 5) argues in a discussion of fishing minigames, waiting is almost invariably involved in digital fishing: this delay is also an opportunity for players to distance themselves from the demands of the gameworld and reconfigure their relationship with the landscape. It is, somewhat paradoxically, a pastime within a pastime, providing respite from the neoliberal work culture that pervades game experience (and particularly the experience of AAA games). The protagonist of Hades (Supergiant Games, 2018), another game featuring a fishing minigame, spells it out for the player: “I’ll have you know some of us take matters of fishing very seriously, sir! Besides… helps take my mind off having to fight your Elysian brethren nonstop.”

If digital fishing forms part of games’ resistance to the aggressive temporalities of neoliberal modernity, it often conjugates that resistance in environmental terms. As Alenda Chang discusses in Playing Nature (2019, pp. 187-236), video games tend to reflect Western modernity’s extractivist assumptions about the natural world: they often present the landscape reductively, as a set of resources to be extracted and exploited. Because of its slowness and relative inefficiency, digital fishing promises to disrupt that understanding: in games like Red Dead Redemption 2, which overflow with tasks and missions, fishing shifts the focus from the player character’s in-game goals to a more distanced, contemplative appreciation of the natural environment. Contemplative appreciation sounds like a good thing, and it is certainly an improvement over capitalist exploitation, but even this experience of nature is not necessarily unproblematic since it can romanticize the wilderness and thus reify it as a binary alternative to urban life.

Over the last two decades, work in the environmental humanities has emphasized the inseparability of human cultures and nonhuman processes (including the Earth’s climate and its ecosystems) -- the kind of inseparability that Donna Haraway (2003) calls “natureculture” and Timothy Morton (2010) describes under the heading of the “mesh.” Nonhuman is, admittedly, a broad term that encompasses animals but also processes affecting ecological systems (including for instance climate change) as well as computational technologies such as AI. In the context of this article, “nonhuman” functions mainly as a signifier for animal life, but it also denotes the larger ecological forces in which both human societies and animals are embedded. Even more broadly, the nonhuman refers to algorithmic technologies that can draw attention to the limits of Western understandings of the human in practices like digital gameplay (see Gallagher, 2020; Wilde, 2024).

Insofar as fishing (real or digital) embraces idealized notions of the wilderness as a space devoid of human presence, it deflects attention from the pervasiveness of human impact on ecosystems in the real world. Fish itself is, of course, involved in this dynamic: wild fish stocks have been steadily declining due to overfishing and various forms of pollution, while intensive aquaculture dramatically reshapes the bodies and affects the lives of farmed fish [2]. Put more simply, Red Dead Redemption 2 deploys fishing as a means of disrupting the hegemonic temporalities of game experience, but it does not go very far in challenging an idealized understanding of nature. In that respect, digital fishing in Red Dead Redemption 2 builds on, and propagates, many of the ideas that surround real fishing as the vehicle of a dichotomous understanding of the human-nonhuman divide -- an activity that reconnects us with nature seen as categorically distinct from “us.” But digital fishing can be much more radical in its subversion of conventional views of the natural world. Further on, I will examine two games in which fishing is not just a minigame but rather a primary gameplay system that unsettles binary thinking, either through cartoonish satire and generic experimentation in Dave the Diver, or through a "weird" narrative staging the breakdown of human subjectivity in Dredge. Before turning to those examples, I will build on work in the social sciences and environmental humanities to unpack the cultural meanings of angling and its digital counterpart. I will also situate digital fishing within contemporary debates on ecogames.

Embodying the Waterscape

Over the last two decades, researchers in the “blue humanities” have been exploring the cultural negotiation of water as a site of considerable ecological significance, particularly in times of climate crisis (see, e.g., Alaimo, 2019). Commercial and recreational forms of fishing are clearly an important focus of those discussions. According to sociologist Adrian Franklin, “the underlying attraction of [fishing] is the possibility of a highly sensualized, intimate and exciting relation with the natural world” (2001, p. 58). This conclusion is based on the analysis of the cultural discourse surrounding fishing, which Franklin traces back to Isaak Walton’s highly influential treatise The Compleat Angler (1897; originally published in 1653). Social scientists have tended to foreground the ideological construction of fishing and hunting, particularly their link with gender (through their masculine connotation), their role in establishing social identity and the nostalgia they express for a premodern or romanticized understanding of nature. This is a plausible explanation of the appeal of these recreational activities, Franklin argues, but it is incomplete in that it misses an important dimension of fishing and hunting -- namely, their embodied quality. Largely, this means that hunting and fishing push back against the ocularcentrism of Western modernity (see, e.g., Levin, 1993): namely, its tendency to foreground vision as the most significant and reliable of the senses. Instead, the hunter and angler are asked to embrace a broad range of sensory stimuli in their engagement with the natural world. Vision is not enough to be an effective angler; instead, one must learn to pick up on subtle auditory cues (such as a splashing sound on the water’s surface) or haptic sensations (a light vibration on the rod). The sensory stimulation of fishing was already foregrounded in Walton’s seventeenth-century account, as Franklin points out, and it emerges repeatedly in recreational fishing manuals or magazines.

This sensory emphasis is sometimes present in digital games as well. Consider again fishing in Red Dead Redemption 2: a light vibration of the controller signals that a fish is close, so we should press the right trigger to hook it. This is a rather uncommon use of the controller’s haptic feedback, which is generally a response to our input (and to in-game events). In this case, however, the vibration is a signal we must respond to, in the absence of visual cues in the gameworld: the fishing mechanic thus shifts the sensory emphasis in a way that deepens the player’s embodied engagement with the fishing simulation [3].

In real-world fishing, the result of this heightened attention to the sensory world is an experience of bodily wholeness or completeness as well as immersion in the natural environment: Franklin (2001, p. 72) calls it “spatial locatedness.” The angler’s body is thus elevated from the routines of city life and situated within a uniquely rich and patterned sensory environment, leading to a heightened appreciation of being-in-nature. It is easy, as Franklin points out, to interpret this immersive experience in terms of established dichotomies between nature and culture. But that is not the only way in which the sensory stimulation of fishing can be framed. Another social scientist, Jacob Bull (2011), has developed an alternative account of the experience of angling, one that is more in line with contemporary theorizations of natureculture. Bull identifies a fundamental tension in anglers’ experience between a romanticized, dichotomous understanding of nature (derived from conventional notions of the wilderness) and awareness of human impact on fish populations. As Bull describes the latter position, “the various processes of ‘landscape’” are shaped by “the different pressures of aquaculture, angling, and the biochemical processes of catchments” (2011, p. 2276). These pressures emerge repeatedly in Bull’s interviews, for instance when one of his participants, Eric, discusses physical differences between wild fish and the diminished bodies of stocked (i.e., farmed) fish. Even when an idealized notion of nature is invoked by the participants, their language and practices display incipient awareness of the inseparability of natureculture. This provides Bull with an opportunity to reframe angling as an activity that can, potentially at least, bring into view the materiality of fish. Materiality is seen here as a foil to narratives of human mastery, which are deeply bound up (conceptually and historically) with the romantic idealization of nature.

This understanding resonates with how the concept of materiality has been formulated and discussed in the environmental humanities, for instance in Karen Barad’s (2007) or Jane Bennett’s (2010) work (the former is explicitly referenced by Bull). Materiality suggests reciprocity in human-nonhuman relations: the human world shapes the material, but the material has in turn powers and modes of agency that resist (and can potentially upend) human control. Sensory apprehension is crucial to grasping how the nonhuman environment is no mere passive background to human activities but rather a stage for processes -- forms of agency -- that elude human subjectivity. For Bull, the bodies of fish are a living illustration of this reciprocity: as fish are violently reshaped and scarred by human activities (for instance in aquaculture), their vitality becomes difficult to pin down. Fish bodies, argues Bull, “are physical and imaginative icons of the various landscapes in which they exist but also trouble their construction” (2011, p. 2275). This difficulty of capturing fish within the anthropocentric grid of landscape -- including dichotomies between rural and urban, wild and farmed -- plays a prominent role in radical digital fishing, too, as I will detail in the next sections.

Bull highlights that this insight into nonhuman materiality is not a theoretical posit but emerges in the experience and language of angling once nature vs. culture binaries break down. Conceptually, this is a two-step process, although in experience it may play out as a continuum (as Bull’s discussion emphasizes). First, the angler’s attention is trained on the material coexistence of water and fish: the animals inhabit a fluid medium -- the “waterscape” -- in which gravity and movement work in a profoundly different way from terrestrial environments. Building on Maxine Sheets-Johnston’s (2011) phenomenology of movement, Bull suggests that the “angler [must] understand movement in ways which challenge airy understandings of the world. Water is full of flows, boundaries, and gradients which act as friction on the free movement of bodies through space” (2011, p. 2279). But the angler is no impassive observer of the waterscape, because their own body resonates with it. This is the second step in Bull’s account of materiality, and it brings us back to Franklin’s discussion of embodiment in fishing. The angler’s body aligns itself with the waterscape, taking in its rich materiality and adjusting imaginatively to its flow-like qualities.

Note that this is a profoundly different construal of embodiment in fishing from the notion of immersion in supposedly pristine nature. While the latter understanding is broad, unspecific and builds on preconceived notions of human-nonhuman distinction, what Bull calls bodily “alignment” with the materiality of the waterscape implies acknowledgment of reciprocity in human-nonhuman encounters. The coexistence of these modes of relation to the nonhuman is one of the defining tensions of the experience of angling. However, the former, dualistic conceptualization tends to be foregrounded by anglers’ language, while the latter is more likely to emerge in the practice of angling than in explicit discourse -- or it has to be carefully teased out from the anglers’ observations, as Bull shows. In any case, the experience of angling remains suspended between the assumed separateness of nature and awareness of the unique material properties of the waterscape as an environment that differs fundamentally from the angler’s own terrestrial lifeworld. Whether this experience ends up reaffirming binary thinking on the nonhuman or challenging it depends on a variety of factors, both personal and contextual. This ambiguity applies to digital fishing as well. The case studies below implement strategies on the level of both gameplay and narrative to tilt the balance toward critique of the dualistic or romanticized understanding of fishing. But before turning to the game analysis, it will be helpful to position radical fishing games within debates on the ecological potential of digital gameplay.

Ecogames between the Sublime and Irreverence

In times of overlapping ecological crises (from global warming to ocean acidification, to name just two of the anthropogenic threats the planet is facing), the environmental significance of video games has not gone unnoticed. John Parham (2016) and Alenda Chang (2019) were among the first scholars to interrogate the ecological assumptions embedded in games, discussing topics including games’ alignment with extractivist modernity or the way they give shape to anxieties of environmental collapse. “Ecogame” is a loose term to describe any video game that resonates with environmental questions [4]. Parham’s reading of Journey (thatgamecompany, 2012), for instance, focuses on how the sublime of that game’s vast landscape speaks to themes of ecological interconnectedness and human insignificance -- a “dark ecology” that Parham (2016, pp. 224-225) links to Morton’s (2010) theorization of the nonhuman. Chang’s more comprehensive approach to ecogames combines ideological critique and conceptual analysis of how games “dramatize and make actionable a variety of ecological entities, processes, and framings, from mesocosmic experimentation to scalar toggling to empathy for nonhuman animals and matter” (2019, p. 145). Chang’s critique focuses on how particular games or genres embed a reductive vision of the nonhuman, whereas her conceptual analysis highlights the potential of certain game design choices and mechanics for capturing the scale and complexity of ecological relations.

In parallel with these large-scale conceptualizations of ecogames, researchers have offered insight into how digital play engages with the life and experience of nonhuman animals. Michael Fuchs (2021), for example, reads Bear Simulator as a game that challenges anthropocentric thinking by asking the player to take on the body and sensorimotor affordances of a bear. Despite its conceptual and practical limitations, which Fuchs underlines, this type of gameplay confronts players with the enmeshment of human subjectivity, nonhuman life, and digital technology: “players dissociate themselves from parts of their humanity and temporarily transform into a hybrid, posthuman creature entangled with human, bear, avatar, and computer” (Fuchs, 2021, p. 271). Games like this, which cast the player in the role of a nonhuman animal, thus have the potential to participate in the deconstruction of Western conceptions of human subjectivity [5]. They do so by promoting what David Herman (2018, p. 139) calls “Umwelt modeling,” or the imaginative exploration of lifeworlds that are explicitly coded as nonhuman. There are limitations to this project, however: projection into animal lifeworlds can lead to complacency or a delusion of mastery if the player is made to believe that technology allows them to fully understand nonhuman ways of being [6].

What I call radical fishing games explore the nonhuman without engaging in direct identification with a single nonhuman protagonist. The protagonist (and player-controlled character) is coded as human, but the player’s relationship with animals is complicated by incongruities that defamiliarize the experience of fishing along two routes: Dave the Diver steers it toward creative experimentation with genre, while Dredge blends it with mystery and horror elements. In both instances, it is the ecological potential of the incongruous that comes to the fore; this is an aspect of ecogaming that has received scarce attention in games research. A significant exception is Tom Tyler, whose book Game (2022) discusses the multiple meanings of animals in games, including their incongruities. Tyler (2022, pp. 59-64) offers a critical reading of Vlambeer’s mobile game Ridiculous Fishing (2013), which centers on the game’s problematic obsession with (virtual) money-making. Dave the Diver also adopts a cartoonish lens and turns fish into a source of revenue, but it does so in a much more sophisticated way than Ridiculous Fishing, emphasizing the stakes of ecosystemic relationships and also integrating an explicit satire of the environmental movement.

In literary ecocriticism, Nicole Seymour’s work has influentially addressed the role that irony can play in ecological thinking. Her book Bad Environmentalism takes its cues from the limited affective repertoire of the environmental movement, whose earnest appeals can sometimes be perceived as moralizing and sanctimonious, thus triggering psychological resistance. Moreover, as Seymour (2018, p. 3) notes, the negative emotions associated with the ecological crisis -- the “doom and gloom” scenarios and cautionary tales brandished by the media -- can easily backfire: instead of being politically empowering and transformative, they can lead to psychological paralysis and inaction. This prompts Seymour to turn to artistic works that employ irony to critique the shortcomings of the environmental movement and question one of its main tenets -- namely, that “reverence is required for ethical relations to the nonhuman, that knowledge is key to fighting problems like climate change” (2018, p. 5). Irreverence might be able to disrupt and complicate the dyad of concern and hope that shapes the rhetoric of the environmental movement. It can decenter human assumptions but also denounce specific historical responsibilities vis-à-vis an ecological crisis that is too often blandly imputed to “humanity” and not to the governments and corporations that are legitimizing environmental destruction. Lastly, irreverence might be used to shift the focus from nature vs. culture binaries toward the amalgam of natureculture.

Seymour focuses on irony and carefully uncouples it from the comic and humor as literary modes that can “reaffirm normative values” (2018, p. 33). My focus here is on incongruity rather than irony per se, and particularly incongruity as leading to either cartoonish exaggeration or the sense of wrongness that Mark Fisher associates with the weird mode of narrative representation [7]. Weird fiction has been hailed by numerous scholars as a productive mode for engaging ecological issues: its distinctive mixture of cosmic horror, fantasy and science-fiction elements speaks to the uncertainties of the climate crisis (Robertson, 2018; Ulstein, 2017). This is particularly true for “new weird” fiction à la Jeff VanderMeer, whose framing is explicitly ecological and avoids the problematic racism and gender politics of H. P. Lovecraft’s “old” weird [8]. Like irony, the weird is transgressive and blurs generic as well as conceptual and affective boundaries; the sense of incongruity or wrongness it evokes is thus ideally positioned to complicate conventional emotional responses to the nonhuman world. Humor may also be a byproduct of incongruity, particularly in my first case study, but it is (as I will argue in more detail) certainly not humor aligned with normative values. In fact, the incongruities I focus on are irreverent and subversive: like the “animal mayhem games” I discuss elsewhere (Caracciolo, 2021), my examples suggest that the nonhuman may enter gaming practices and trouble anthropocentric ways of relating to nature. Through its ambiguities and paradoxical tensions, digital fishing becomes a springboard for playful engagement with received ideas of nature.

Humor and Genre in Dave the Diver

Both Dave the Diver and Dredge can be classified as independent games, but the former more clearly embraces the vintage aesthetics that are typically associated with indie productions: the side-scrolling layout of the levels and pixelated graphics are closely reminiscent of classic video games from the 1990s [9]. The humor of the cut-scenes harkens back to early LucasArts games such as Day of the Tentacle or the Monkey Island series, but instead of the point-and-click mechanics of those games, Dave the Diver builds on an innovative combination of platform gameplay and restaurant management simulation. Each in-game day starts with the titular Dave, the player-controlled character, diving to catch fish that will be prepared and served that night at his sushi restaurant. While Dave is solely responsible for catching fish (at least until a fish farming mechanic is unlocked later in the game), he is assisted at night by a sushi chef, Bancho, and several employees. Most of the quests revolve around Bancho and Dave’s business partner, Cobra, along with an expansive cast of side characters. Developed by a Korean studio, Dave the Diver is also a humorous reflection on global representations of East Asian identity and culture, with food playing a key role in both the gameplay and narrative.

The main story centers on the secrets hidden within the expansive body of water where Dave dives every day to fish, known as the Blue Hole. Inspired by a Japanese manga series from the 1990s (Blue Hole), the Hole houses an anomalous ecosystem that contains fish from multiple regions of the world as well as prehistoric species not found anywhere else. In the course of his underwater explorations, Dave comes into contact with a population of humanoid “Sea People” who live deep in the Blue Hole (see Figure 1). This civilization is inspired by ancient East Asian cultures, as their architecture and clothing attest, but the Sea People are also visibly nonhuman (they are fish-like from the waist down, like mermaids). The Sea People are threatened by the melting of a glacier located under their village, which is causing earthquakes that disrupt the community’s daily life and the ecosystem they depend on. Dave’s task is to enter this frozen area and restore the underwater world’s balance by solving puzzles and defeating a number of challenging bosses, including a giant prehistoric shrimp which serves as the game’s final boss.

Figure 1. Dave among the Sea People in Dave the Diver. Click image to enlarge.

This hodgepodge of real-world ecosystems and cultural references is of course an invitation not to read the game as an accurate exploration of fishing or its ecological significance. If Dave the Diver raises provocative questions from a nonhuman-oriented perspective, it is through its sophisticated combination of representational and formal (algorithmic) strategies: on the one hand, the game thematizes nonhuman life and environmental activism; on the other, its mechanics constantly challenge the player’s genre-based expectations, creating humor that defamiliarizes the human-nonhuman binary.

The environmental overtones of the story should be clear, particularly since the melting glacier functions as a thinly veiled allegory for global warming. Dave the Diver also stages environmental activism via an organization known as Sea Blue. A number of hostile encounters with the cartoonish Sea Blue leader, John Watson, punctuate the story, and Watson repeatedly accuses Dave of destroying the ecosystem. As Dave’s friend, Cobra, explains: “That group is infamous. They commit acts of violence under the pretext of environmental protection. It’s mostly the large corporations with big fishing businesses and not the small fisheries, that harm the environment most. They say nothing to the corporations, however.” Eventually, an incursion into the Sea Blue base reveals that the organization’s environmental focus is only a front for a lucrative business that involves selling dolphin meat for human consumption.

This humorous subplot, which turns environmental activists into cartoonish villains, exposes the inadequacies of environmental rhetoric that solely targets individual consumption instead of the large-scale corporate interests that are driving the ecological crisis. More indirectly, the Sea Blue story highlights the ecological stakes of the player character’s actions: Dave’s efforts at catching individual fish do inflict violence on the nonhuman, but on a scale that does not jeopardize entire ecosystems -- unlike far more destructive industrial fishing. The word “efforts” is important here: many tasks in the game can be automated (for instance, by hiring or training staff at the restaurant), but the fishing mechanic never loses relevance. It requires shooting with a harpoon or gun repeatedly until the fish dies or is sedated and can thus be collected by Dave. Given the fishes’ wide variety of movement and attack patterns, this is never a trivial act but requires speed and tactical thinking. For larger fish, the challenge is increased by the need to complete a series of timed puzzles (for instance, pressing the spacebar or a combination of buttons quickly). Even if Dave’s armament improves significantly over the course of the game, fishing remains effortful throughout, which is an important factor in the player’s enjoyment.

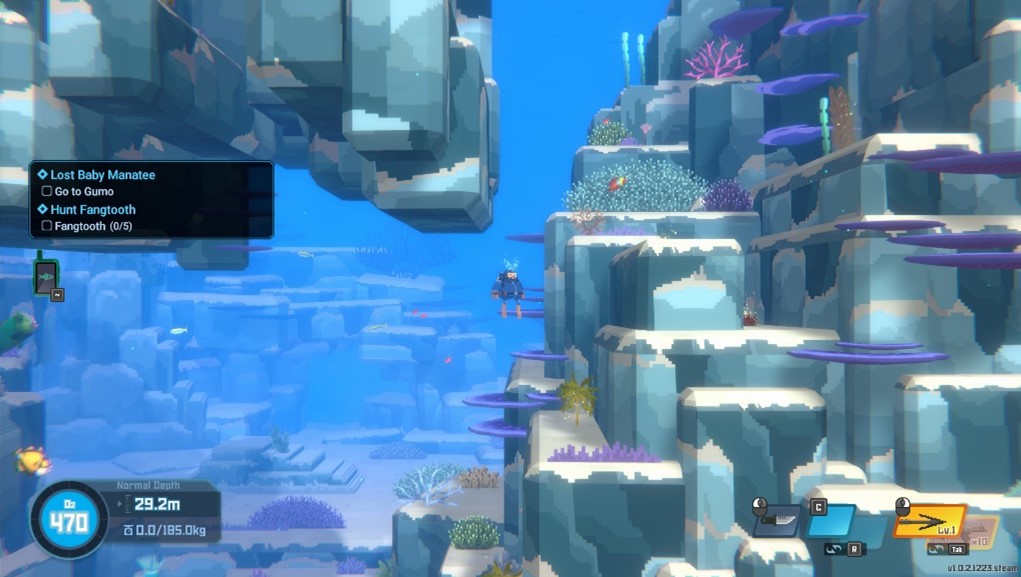

Equally important are two other factors: the pleasure of exploring levels that change depending on the weather, the time of day, and the game’s randomization algorithm; and the way in which the game keeps diversifying and complicating its basic gameplay formula. The underwater world of Dave the Diver is rendered in attractive pixelated graphics, which foreground a variety of biomes, from the tropical reef of the Blue Hole Shallows (up to 50 meters in depth; see Figure 2) to the frozen Glacial Area. As the player dives deeper, they are introduced to new mechanics that facilitate or even enable exploration: for instance, the biome known as Blue Hole Depth requires a special UV lamp to push back dangerous tubeworms that block access to several tunnels. Moreover, every time the player dives, the game selects the layout of the level from a number of available maps, so there is some degree of randomization at work. When the player dives at night, the map contains entirely new species and threats. The diversity of levels and biomes, fishes and exploration mechanics creates a sense of unpredictability, which -- together with the visual appeal of the maps -- speaks to notions of nonhuman agency and vitality.

Figure 2. Exploring the Blue Hole Shallows in Dave the Diver. Click image to enlarge.

The game asks the player to engage with the nonhuman materiality of the sea through a satisfyingly embodied gameplay loop. As the player learns how to maneuver Dave around the dangerous wildlife and the physical features of the biomes he explores, the impression of continuity between his embodiment and the waterscape contributes to the rewards of gameplay. Put otherwise, the flow of Dave the Diver emphasizes the kinesthetic and imaginative pleasures of the player character’s encounter with a multiplicity of waterscapes, in line with the embodied accounts of fishing offered by Franklin and Bull. However, the unpredictability of the maps keeps players from projecting anthropocentric control: the player is immersed in nonhuman materiality but is also reminded of its elusiveness and autonomy. The game’s representation of the Sea People, who are anthropomorphic but aquatic, goes even further: the Sea People embody the impossibility of drawing sharp distinctions between human and nonhuman lifeworlds.

This redrawing of human vs. nonhuman distinctions is not only performed through basic gameplay and narrative, but is also linked to the game’s brilliant experimentation on the level of genre. Many reviewers (e.g., Livingston, 2023) have remarked on the seemingly endless creativity of Dave the Diver, which keeps introducing new mechanics and minigames even when the player is approaching the ending. The Sea People Village, for example, offers both a racing simulation (Seahorse Racing) and a card game reminiscent of Concentration. New types of spatial puzzles are introduced as the main story progresses, along with a variety of farming minigames (a fish farm, plots for growing vegetarian sushi ingredients, and an underwater seaweed farm). The end credits themselves are presented in the form of a space shooting minigame. A certain amount of diversity on the level of genre and mechanics is present in many successful games, but the over-the-top quality of Mintrocket’s inventiveness turns Dave the Diver into something like a metagame: a game that reflects humorously on the affordances and limitations of game genres, particularly genres (such as farming or restaurant management) associated with casual gaming.

Casual gaming (along the lines of FarmVille) tends to de-emphasize the complicated mechanics of more mainstream titles, instead focusing on streamlined gameplay loops and immediate rewards, which are frequently monetized by developers through in-game transactions [10]. Dave the Diver offers a satire of this type of shallow gameplay: it borrows the relaxed atmosphere of these games but also recontextualizes it within a much more sophisticated design in both mechanical and narrative terms. Simultaneously, the game pokes fun at how minigames (including fishing minigames) promise respite from the teleological or quantifiable nature of gameplay in AAA productions like Red Dead Redemption 2 (as discussed above). This is not to say that Dave the Diver rejects quantification entirely: revenues from the sushi restaurant can be used to purchase equipment upgrades, many of which are needed to complete the story. But the game allows players to tackle this challenge at their own pace: while some side quests can only be completed at a certain time (for instance, in stormy weather), the player can put the story on hold for as long as they would like to focus on exploration or fishing rare species instead. Many elements of the game’s aesthetics and atmosphere contribute to setting a relaxed pace that is reminiscent of casual gaming but also critical of its complicity with neoliberal ideology. Largely this depends on how the fishing and restaurant simulation mechanics are embedded in a thematically complex narrative. The game’s plot offers nuanced engagement with ecological crisis and the exploitation of the sea at the hands of the capitalist world system. Dave the Diver’s bad environmentalism employs cartoonish comedy to blur the divide between human and nonhuman life (via the Sea People). It foregrounds the scale of environmental impact and also critiques the rhetoric and biases of environmental activism.

All of these elements are supported by the way in which the gameplay keeps evolving and diversifying. On the one hand, the inventiveness of the game’s string of minigames serves as a formal equivalent of the fluidity of the waterscape that the player character is exploring. Just as water and fish evoke associations with slipperiness and shapelessness, Dave the Diver is difficult to pin down at the level of genre. It is constantly evolving and boasting a creativity that mirrors the endless variety of nonhuman materiality. On the other hand, the game is well aware of the limitations of this parallel between game design and the nonhuman world. It does not take itself too seriously, either as a metagame or as a satire of the environmental movement. Instead, it invites the player to confront the ambiguity of their engagement with the game, enjoying the embodied flow of their interactions with waterscapes while remaining aware of the destructive impact of large-scale industrial practices.

Weird Fishing in Dredge

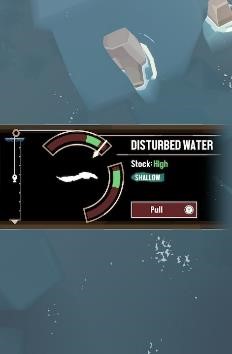

If humorous experimentation is the main source of incongruity in Dave the Diver, Dredge stages a different form of incongruity -- the sense of wrongness that Mark Fisher sees as central to the “weird” mode of representation: the “weird . . . is a signal that the concepts and framework which we have previously employed are now obsolete” (2016, p. 13). The incongruity can be simply stated as follows: apparently a fishing game, Dredge is actually a puzzle game about confronting a mystery that, in keeping with H. P. Lovecraft’s weird fiction, threatens the player character’s sanity. Fishing is the player’s main means of solving the game’s puzzles and unraveling the mystery. How that works is fairly complicated, but a useful starting point is the idea that, just like Mintrocket’s game, Dredge turns fish into a currency of sorts, with more exotic or rare fish fetching a higher price. The money obtained from fishing can be used to buy a wide range of upgrades, including fishing nets, better engine parts for the player’s boats, and so on. Differently from Dave the Diver, the player does not control a human player character directly but instead drives a small boat, which can be steered towards numerous fishing areas (recognizable from the splashes on the surface). The fishable species vary greatly depending on sea depth and the region of the gameworld (see Figure 3). The fishing itself takes the form of timed minigames: when a special on-screen prompt appears (see Figure 4), the player must interact with the controls in order to successfully catch fish. The exact task varies depending on the fish species, but the time-based logic of the challenge does not change.

Figure 3. World exploration in Dredge. Click image to enlarge.

Figure 4. Timed fishing minigame in Dredge: to catch fish, the player has to “pull” (by pressing the Y button on the controller) when the arrow in the green zone.

The game takes place on a fairly vast map divided into five different archipelagos. The archipelagos have different visual and physical characteristics, functioning as self-contained biomes with their own fish species and locations where the player can sell fish or repair the ship. The difficulty of navigating these waters (and fishing in them) increases as players sail from one archipelago to another, typically by following the game’s main quest. In fact, the narrative of Dredge is responsible for creating the sense of mystery that, as I mentioned, shapes the player’s experience of incongruity during gameplay. The game starts with the player character stranded on the island known as Greater Marrow after a shipwreck. The town’s mayor offers to advance the money for the repairs, and the first, tutorial section of the game is spent fishing in order to repay the debt. Atmospherically, the simplicity of the fishing mechanic is underscored by the game’s pleasantly cartoonish graphics, but the mayor’s warning not to fish at night complicates the player’s interactions with the game by introducing a sense of dread -- in itself an emotion typical of the weird genre -- over what may lurk in the sea. The first appearance of a key character, an old woman known as the Lighthouse Keeper, confirms the impression that there is more to the world of Dredge than meets the eye. The mystery vaguely hinted at by the Lighthouse Keeper is linked to fish, and specifically to the first “aberration” or “grotesque fish” that the player character comes across after the prologue. These mutated fish confirm that something is amiss in the gameworld; from now on, they will keep popping up as the player fishes, fetching a higher price from the fishmonger but also acting as a constant reminder of the fact that this is not a regular fishing game. The player-character is soon approached by a mysterious character, the Collector, who explains how to retrieve a number of sunken treasures through a special fishing mechanic called “dredging.” Clearly, the Collector is not telling the whole story, but the player’s only choice is to do his bidding, sailing from one archipelago to another to search for these valuable relics (this is the game’s main quest).

Even if catching fish ceases to be the main objective of the game at this point, it does not drop out of the picture entirely. The search for the relics involves a number of spatial puzzles, many of which require the player (against any real-world logic) to use certain fish types as a key to unlock particular areas or devices (see Figure 5). Fish advance the story in unexpected ways, but obtaining fish also exposes the player to a number of risky situations. First, some fish can only be caught at night, which forces the player to sail out while it is dark and the boat is surrounded by disturbing apparitions. When the player character’s sanity meter -- a feature Dredge borrows from horror games such as Amnesia: The Dark Descent (Frictional Games, 2010) -- descends below a certain threshold, sharp rocks will start popping up suddenly while sailing. Collisions are the most significant source of gameplay challenge, because the archipelagos are designed as maze-like spaces requiring the player to maneuver carefully or risk game over (even an upgraded boat can sink after a handful of crashes). The sailing mechanic thus represents the main way in which Dredge creates flow in the player’s experience, offering a good balance of satisfaction (particularly as the boat becomes faster, with upgraded engines, etc.) and difficulty. The timed fishing or dredging tasks enhance this flow by introducing variations in pace: going from steering the boat to time-based interactions (and back to steering) generates an embodied rhythm that deepens the player’s engagement with Dredge. While the game’s exploration of what Bull would call the waterscape is more distanced than in Dave the Diver, owing to the camera’s positioning with respect to the boat, the material flow of water and fish is recreated at a higher level through the rhythmic combination of sailing and fishing mechanics. The combination is oriented by the narrative-advancing dialogues, which punctuate and frame the player’s experience of the game (provided, of course, that the player is paying attention to the narrative, and that might not be true for everyone) [11].

Figure 5. A fish-based puzzle in Dredge: a “rock slab” requiring “two heavily plated creatures” (i.e., two crabs found in the surrounding ocean) to be activated. Click image to enlarge.

On a thematic and narrative level, a pervasive feeling of incongruity reflects the “wrongness” associated with the weird genre. The story eventually leads the player character to realize that he himself is the Collector. Through a “mind-tricking” twist reminiscent of films such as David Fincher’s Fight Club (see Klecker, 2013), we discover that the Collector is a projection of the player character’s own subjectivity, and that the mystery he is working through -- which involves the death of the Collector’s lover -- is in fact the mystery of the player character’s own life and identity. This ending echoes the Lovecraftian trope of first-person narrators descending into madness as a result of the disturbing events they have witnessed. The wrongness that surrounded the Collector’s figure from the player’s first encounter with him is thus justified psychologically. But the wrongness is not merely hinted at on a thematic level: it is baked into game mechanics through the surprising versatility of fish in the game. In Dredge, fish serve as a currency supporting the player’s progression but also as a solution to many of the game’s puzzles. Fish can and should be sold in Dredge if the player wants to progress through the game, but some fish species -- particularly rare or mutated specimens -- are worth much more than the price they command at the market: they are a key to solving the games’ puzzles and uncovering a mystery that, as the ending reveals, envelops the player character’s own subjectivity.

Fishing is thus consistently defamiliarized by Dredge: it is made weird and turned into the engine of a narrative that blurs the dividing line between the natural world and human psychology. Contagion and mutation are, of course, themes that recur throughout the weird tradition, from Lovecraft to Jeff VanderMeer’s “new weird” fiction. Particularly in the latter strand of the weird, these themes are employed to transgress and disrupt Western dichotomies between the human and the nonhuman -- an ecological dimension of the weird that has been highlighted by many recent commentators (see again Robertson, 2018). Contagion generates incongruity, not through humor (the main focus of Dave the Diver) but through unsettling closeness between human agency and the material powers of the nonhuman world. In Dredge, fish and the gameplay systems that surround it embody this conceptual dynamic: mutation brings together the “grotesque” fish caught around the game’s islands and the player character’s own destabilized mind. Meanwhile, the fishing minigames are not an alternative to hegemonic game time but become fully integrated within narrative progression -- in itself an experimental “mutation” of what is, in most games, merely a relaxing sideshow.

Conclusion

Fishing is caught in a number of cultural and experiential dynamics that reflect the separation between human societies and the natural world (a staple of Western modernity) but also evoke concepts of human and nonhuman embodiment as well as materiality. In video games, too, the representation and simulation of fishing can stage and engage with these ideas, defamiliarizing gameplay and the cultural perception of fishing in the same breath. Following Vanderhoef and Payne’s analysis of Red Dead Redemption 2, I have started from the idea that, as a minigame, fishing can provide a foil to the normative temporal regimes of gameplay, which tend to replicate the pressures of the neoliberal economic system. However, fishing minigames are not ideologically unproblematic: by fostering immersion in simulated natural environments, they risk reinforcing the human vs. nonhuman binary that also shapes the imaginary of real-world fishing. To go beyond this limited imaginary, I have discussed anthropological work that highlights an alternative perspective on fishing, one centered on the embodied possibilities of encountering nonhuman materiality through the flow-like assemblage of water and fish. From that vantage point, the waterscape is interlinked with human agency but can also, paradoxically, resist this agency.

The two fishing games I have discussed in the final sections expose this paradox through algorithmic and thus, at least in part, nonhuman strategies. This is what makes them radical: by elevating fishing to a central game mechanic, they cultivate imaginative engagement with nonhuman materiality while displaying the contradictions of real-world environmentalism (Dave the Diver) and exploring the common ground between human subjectivity and the natural world through the language of grotesque mutation (Dredge). The two games do so by defamiliarizing the act of fishing and foregrounding its incongruity, which is conjugated as humor (Dave the Diver) or disturbing weirdness (Dredge). Dave the Diver and Dredge thus function as ecogames, but only insofar as they practice something akin to what Seymour has called bad environmentalism: they decenter the discourse of the environmental movement, with its earnestness and focus on easily digestible messages, and instead employ formal strategies such as satire and the weird to complicate human-nonhuman relations in times of ecological crisis.

Endnotes

[1] A gameplay video is available here: https://youtu.be/nRg11wqHqMk?si=BnRsGQzBcmJ8zlNi.

[2] My main source here is Bull (2011), which features prominently in my discussion below.

[3] Andreas Gregersen and Torben Grodal (2009) discuss the cognitive-level processes through which game interfaces, including input devices, maximize embodied involvement in games.

[4] See also the collection edited by Op de Beke et al. (2024), which covers a broad range of perspectives on ecogames.

[5] See also Heijmen and Vervoort (2023) for a more sustained account of how games can put pressure on human subjectivity. Heijmen and Vervoort’s discussion doesn’t engage with animal life explicitly, however.

[6] See also my discussion of the ecological significance of “unreadable” animal protagonists in contemporary literature (Caracciolo, 2020).

[7] “The weird is that which does not belong” (Fisher, 2016, p. 10).

[8] See Luckhurst (2017) for more on this distinction between old and new weird.

[9] For more on independent games, see Juul (2019).

[10] See Trépannier-Jobin (2019) for more on casual gaming and its parodies.

[11] See Caracciolo (2015) on the coexistence of ludic and narrative values in gameplay.

References

Alaimo, S. (Ed.). (2019). Science Studies and the Blue Humanities (special issue). Configurations, 27(4).

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Duke University Press.

Barton, M. (2008). Dungeons and Desktops: The History of Computer Role-Playing Games. A. K. Peters.

Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Duke University Press Books.

Black Salt Games. (2023). Dredge [Nintendo Switch]. Digital game published by Team 17.

Bull, J. (2011). Encountering Fish, Flows, and Waterscapes through Angling. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 43(10), 2267-2284.

Caracciolo, M. (2015). Playing Home: Video Game Experiences Between Narrative and Ludic Interests. Narrative, 23(3), 231-251.

Caracciolo, M. (2020). Strange Birds and Uncertain Futures in Anthropocene Fiction. Green Letters, 24(2), 125-139.

Caracciolo, M. (2021). Animal Mayhem Games and Nonhuman-Oriented Thinking. Game Studies, 21(1). http://gamestudies.org/2101/articles/caracciolo

Chang, A. Y. (2019). Playing Nature: Ecology in Video Games. University of Minnesota Press.

Crowther, W. (1976). Colossal Cave Adventure [PDP-10]. Digital game designed by William Crowther.

Endnight Games. (2014) The Forest [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game designed and published by Endnight Games.

Engel, W. (1977). Gone Fishing [TRS-80]. Digital game designed by William Engel.

Fisher, M. (2016). The Weird and the Eerie. Repeater.

Franklin, A. (2001). Neo-Darwinian Leisures, the Body and Nature: Hunting and Angling in Modernity. Body & Society, 7(4), 57-76.

Freeman, E. (2010). Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories. Duke University Press.

Frictional Games. (2010). Amnesia: The Dark Descent [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game designed and published by Frictional Games.

Fuchs, M. (2021). Playing (With) the Non-human: The Animal Avatar in Bear Simulator. In C. Mengozzi (Ed.), Outside the Anthropological Machine: Crossing the Human-Animal Divide and Other Exit Strategies (pp. 261-274). Routledge.

Gallagher, R. (2020). Volatile Memories: Personal Data and Post Human Subjectivity in The Aspern Papers, Analogue: A Hate Story and Tacoma. Games and Culture, 15(7), 757-71.

Gregersen, A., & Grodal, T. (2009). Embodiment and Interface. In B. Perron & M. J. P. Wolf (Eds.), The Video Game Theory Reader 2 (pp. 65-83). Routledge.

Haraway, D. J. (2003). The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. Prickly Paradigm Press.

Heijmen, N., & Vervoort, J. (2023). It’s Not Always About You: The Subject and Ecological Entanglement in Video Games. Games and Culture. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120231179261

Herman, D. (2018.) Narratology Beyond the Human: Storytelling and Animal Life. Oxford University Press.

Iron Gate. (2021). Valheim [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game published by Coffee Stain Publishing.

Juul, J. (2019). Handmade Pixels: Independent Video Games and the Quest for Authenticity. MIT Press.

Klecker, C. (2013). Mind-Tricking Narratives: Between Classical and Art-Cinema Narration. Poetics Today, 34(1-2), 119-146.

Levin, D. M. (Ed.). (1993). Modernity and the Hegemony of Vision. University of California Press.

Livingston, C. (2023, July 12). Dave the Diver Review. PC Gamer. https://www.pcgamer.com/dave-the-diver-review/

Luckhurst, R. (2017). The Weird: A Dis/orientation. Textual Practice, 31(6), 1041-1061.

Mintrocket. (2023). Dave the Diver [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game designed and published by Mintrocket.

Morton, T. (2010). The Ecological Thought. Harvard University Press.

Op de Beke, L., Raessens, J., Werning, S., & Farca, G. (Eds.). (2024). Ecogames: Playful Perspectives on the Climate Crisis. Amsterdam University Press.

Parham, J. (2016). Green Media and Popular Culture: An Introduction. Palgrave Macmillan.

Vanderhoef, M. T., & Payne, J. (2022). Press X to Wait: The Cultural Politics of Slow Game Time in Red Dead Redemption 2. Game Studies, 22(3). https://gamestudies.org/2203/articles/vanderhoef_payne

Robertson, B. J. (2018). None of This Is Normal: The Fiction of Jeff VanderMeer. University of Minnesota Press.

Rockstar Games. (2018). Red Dead Redemption 2 [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game designed and published by Rockstar Games.

Scully-Blaker, R. (2019). Buying Time: Capitalist Temporalities in Animal Crossing: Pocket Camp. Loading: The Journal of the Canadian Game Studies Association, 12(20), 90-106.

Seymour, N. (2018). Bad Environmentalism: Irony and Irreverence in the Ecological Age. University of Minnesota Press.

Sheets-Johnstone, M. (2011). The Primacy of Movement (Expanded second edition). John Benjamins.

Supergiant Games. (2018). Hades [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game designed and published by Supergiant Games.

thatgamecompany. (2012). Journey [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Jenova Chen, published by Annapurna Interactive.

Trépannier-Jobin, G. (2019). The Ambiguity of Casual Game Parodies. Kinephanos, 103-136.

Tyler, T. (2022). Game: Animals, Video Games, and Humanity. University of Minnesota Press.

Ulstein, G. (2017). Brave New Weird: Anthropocene Monsters in Jeff VanderMeer’s “The Southern Reach.” Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies, 43(1), 71-96.

Vlambeer. (2013). Ridiculous Fishing [Google Android]. Digital game designed and published by Vlambeer.

Walton, I. (1897). The Compleat Angler. John Lane.

Wilde, P. (2024). Posthuman Gaming: Avatars, Gamers, and Entangled Subjectivities. Routledge.

Xiao, L. Y. (2023). What’s a Mini-Game? The Anatomy of Fishing Mini-Games. Proceedings of DiGRA 2023. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/4g9ku