Playstyles in Signalis: Style as an Aesthetic Habit

by Johan KalmanlehtoAbstract

In this article, I construct a theoretical conception of playstyle as the way in which a player interacts with game mechanics to complete goal-oriented gameplay tasks. I argue that instead of the optimisation of gameplay performance in terms of tactical and strategic decisions, playstyle can be viewed as an aesthetically valuable way to play a game. Focusing on style as an aesthetic phenomenon also allows it to be distinguished from the notions of personal style and player typologies. In this work, I inspect style as a way of enacting practical actions and I highlight its conceptual relations to strategy and habit. As an example of the aesthetics of playstyle, I analyse the game mechanics of Signalis (Rose-engine, 2022) and how the game connects different playstyles to its narrative conclusion. Overall, I suggest that playstyle is not merely a matter of strategic decisions or personal gameplay motivation but also a phenomenon that can be interpreted in terms of beautiful gameplay. Especially in leisurely gameplay, playing beautifully can be more important for the player than mastery over the ludic system.

Keywords: style, playstyle, agency, habit, practice, aesthetics, personality

Introduction

The concept of playstyle is often used to denote different ways to play a game. However, while style generally means the way of doing something, I argue that not all ways of playing a game are variations in playstyle [1]. Indeed, gameplay itself is a multifaceted concept, and hence, in order to define playstyle as the way in which a player plays a game, it is important to demarcate which part of gameplay is relevant for playstyle. In this article, I construct a theoretical conception of playstyle as an aesthetically valuable way of completing goal-oriented, practical gameplay [2] tasks. I then use the game Signalis (Rose-engine, 2022) to highlight how aesthetic playstyles can be incorporated into game design.

Playstyle has been investigated in previous gameplay research, but most studies have focused on style as a matter of personality trait(s) or in terms of winning strategies in competitive gameplay (e.g., Eggert et al., 2015; Gow et al., 2012; Tekofsky et al., 2015). Most of the research on playstyle does not problematize the concept of style itself, but rather uses it to answer another research question, one regarding e.g., the correlation between playstyle and player age (Tekofsky et al., 2015), cultural differences (Bialas et al., 2014) or nationality (Ravari et al., 2022). According to Mader and Tassin (2022), previous research has either defined different styles a priori based on pre-made categories or has not provided interpretations of different playstyles. Research focusing on competitive multiplayer games tends to interpret playstyles in relation to skill, scores and winning strategies (Normoyle & Jensen, 2015), whereas other scholars have focused on style in terms of gameplay motivations, such as role-playing, competitiveness or social relations (Jaćević, 2021; Kallio et al., 2011).

I argue that instead of merely representing an effective gameplay strategy, playstyle should be regarded as an aesthetic phenomenon. Additionally, while personality and playstyle may affect each other, there is no necessary connection between the two. Indeed, similar to artistic style, playstyle can be guided by the player’s aesthetic judgement of beautiful gameplay. In this way, having a style is not so much about reflecting one’s personality than about playing in a way that is aesthetically enjoyable. Interpreting playstyle as an aesthetic phenomenon provides a way to consider how players’ gameplay decisions might be guided by aesthetic motivation instead of competitiveness and optimisation. From the player’s perspective, style may be a matter of transforming passive gameplay habits into aesthetic gameplay practices; in this context, the aesthetics of actions are prioritised instead of the aesthetics of game artefacts (see Nguyen, 2020a; 2020b).

I begin by defining playstyle as a way of playing a game that relates to the player’s attempt to accomplish a practical task defined by the game. I consider style first through the distinctions between the style of an object and the style of a process, descriptive and evaluative interpretations of style and the difference between aesthetic and artistic styles. In the next section, I consider how aesthetic style differs from personal style. From these distinctions I proceed to highlight how aesthetic playstyle differs from strategic and tactical optimisation of gameplay, and how style shares with habit a twofold nature between passive tendency and active practice. Lastly, I explore how the survival horror game Signalis uses interpretations of playstyle to decide the game’s branching narrative closure as an example of how games can highlight style as an aesthetic choice.

Conceptual Distinctions of Playstyle

In terms of etymological background, the word “style” originates from the Latin word stylus, which refers to a pointed inscription tool (Oxford University Press, 2023). The meaning of the word style stems from the context of literary expression, from which it has spread into the domains of artistic expression, modes of behaving and even ways of life. Most importantly, style refers to how something is done, not what is done. For example, a novelist can write the same story with multiple variations in style, like Raymond Queneau in Exercices de style (1947), and painters can produce stylistically different paintings of the same subject. According to Siefkes and Arielli (2018), style is an ambiguous concept that can describe any kind of human practice; it has even been suggested that the term should be abandoned altogether for not having any theoretical value. Style has proven especially difficult to distinguish from the concepts of technique, content and function, yet none of these terms can completely replace the meaning of style (Siefkes & Arielli, 2018). Playstyle is similarly difficult to distinguish from strategy, habit and behaviour, but cannot be fully replaced by these terms. Generally, all these terms can refer to how a game is played, but style differs from them by introducing an aesthetic motivation for varying one’s way of playing.

As I focus on playstyle in terms of how players complete practical tasks to reach the goal of the game, I leave some elements of gameplay outside of my conception of playstyle. Hence, I consider only the ways in which players attempt to complete gameplay tasks to be relevant for determining their styles of play. For this reason, I do not consider such things as the social context of playing, visual appearance of a playable character, or narrative and moral choices in the gameworld as part of playstyle. On occasion, such choices may affect playstyle, such as when the chosen equipment modifies the character’s abilities. For example, in the Dark Souls Series, the wearable equipment chosen for the character affects the character’s movement and defensive statistics. A phenomenon called “fashion souls” within player communities refers to choosing equipment solely based on how it looks, disregarding its effects on gameplay (e.g., Brock & Jonhson, 2022). When such choices related to appearance are made purely for the purpose of fashion, they are unrelated to playstyle as I construe it.

Likewise, when a game features narrative or moral choices, it might be tempting to refer to the moral characteristics of the chosen character as a playstyle. However, playing an evil or a good character is more related to narrative content than reflecting variation in how the player completes the gameplay task. Players can have similar playstyles regardless of the moral stance of their characters or the narrative choices they make. In games in which narrative or moral choices are the main gameplay mechanic, these choices could constitute playstyle, but such games tend to have heavy restrictions on the ways in which they can be played. The social context of gameplay, such playing with or against other players, might also affect the style of play, but it does not necessarily determine how the player pursues the goal of the game.

Although the term style can be discussed under numerous conceptual distinctions (e.g., Shusterman, 2011), my conception of playstyle is grounded in three particular distinctions: 1) the style of an object versus the style of a process, 2) evaluative versus descriptive meanings of style, 3) artistic versus aesthetic style.

First, I consider playstyle as the player’s aesthetic preference regarding what kind of goal-oriented gameplay feels aesthetically valuable for them. It is not possible to delve into the discussions about the nature of aesthetic experience within the scope of this article, and hence, I will offer here a rudimentary definition of it as an experience that is pleasurable for its own sake. Although style can be considered as a perceived quality of an aesthetic object, such as an artwork or a performance of gameplay, my conception of playstyle refers to the player’s aesthetic experience of their own goal-oriented action. Nguyen (2020b) has considered a such difference in terms of object and process aesthetics: in object aesthetics, an object that is external to the observer is appreciated aesthetically, but in process aesthetics, an enactor of an action appreciates aesthetically how engaging in such an action feels like. In process aesthetics, including games, only the subject who enacts the action can experience it aesthetically. Viewing someone else play can at best provide a glimpse of what it would feel like. The aesthetic value of playstyle is hence appreciated by the player in terms of how it feels like to engage in goal-oriented play in a certain way.

Second, the term style can be used in both a descriptive and evaluative sense. It can refer to the way something is done as a mere habit or manner, but more often style is used to denote an aesthetically valuable way of doing something (Riggle, 2015; Siefkes & Arielli, 2018; Shusterman, 2011). All actions have a style in the descriptive sense, because they must be enacted in one way or another. However, to say that something is done with style tends to mean that the action was performed in a distinguishable or aesthetically valuable way. Similarly, all players necessarily play a game in some manner or another, but playstyle can also refer to an aesthetically valuable way of playing. My purpose here is to investigate playstyle as an aesthetic preference, which is used in the evaluative sense by the player. This allows me to distinguish aesthetic playstyle, for example, from pure strategy. While both are related to how a game is played, strategy is motivated only by the goal of a game, whereas playstyle is motivated by the aesthetic value of the player’s action.

Third, I consider playstyle primarily as an aesthetic rather than artistic phenomenon. Because goal-oriented gameplay involves a practical attitude of overcoming the game’s obstacles, its style is closer to the styles of practical everyday actions than artistic creation. An intention of presenting one’s style of play to an audience could make it closer to artistic style as it transforms gameplay into performance. Such a precondition for considering something as art has been made, for example, in institutional art theory (Dickie, 1974). However, I do not make a categorical distinction between art and aesthetic experience, but instead suggest that the styles of practical gameplay actions are situated between art and everyday aesthetic experience. Von Bonsdorff has used the term “aesthetic practice” to refer to different aesthetically motivated practices that are not quite art but do not belong to everyday aesthetic experiences either, characterising them as “first-person aesthetics” (Bonsdorff, 2023, p. 35). Hence, artistic and aesthetic styles can overlap, but I consider artistic gameplay to be more focused on presenting ways of playing that can be appreciated by others, whereas playstyle as an aesthetic preference needs to be aesthetically valuable only for the player and is not necessarily distinct in its outward appearance. For example, two players might play a game in a similarly looking way, but one might play in this way because it provides a competitive advantage, and the other because it provides them aesthetic enjoyment.

In summary, I consider playstyle in terms of the player’s aesthetic evaluation of how their practical, goal-oriented gameplay actions feel like. Playstyle is related to process aesthetics, in which aesthetic value is not located in a quality of a perceived object but in an inner sensation of engaging in practical actions. Because the focus is on the player’s own experience rather than on how others perceive the gameplay, playstyle is more an aesthetic than artistic phenomenon. However, styles can also be presented to others, and instead of strict demarcation, there is a continuum between aesthetic and artistic styles. In the next section, I consider how aesthetic playstyle differs from personal style.

Playstyle and Personality

Style and personality have often been connected in the Western philosophical context (Kalmanlehto, 2025; Jenewein, 2024). In this article, I focus on playstyle as an aesthetic phenomenon using an analysis of Signalis as a case study and do not engage in a deeper investigation of the relationship between style and the self. However, as many previous investigations view playstyle in relation to personality, it is important to consider how playstyle as an aesthetic phenomenon differs from such viewpoints.

An influential definition of playstyle comes from Bartle’s (1996) player typology, which includes achievers, explorers, socializers and killers. According to this typology, different ways to play a game correspond to distinct types of players: achievers play for the sake of achievement, such as a high score or a reward; explorers favour immersion and narrative details, preferring to discover the gameworld; socializers are more interested in social aspects of gameplay than the game itself; and killers enjoy the competitive side of games. Bartle discussed these types of players in terms of styles, but in my view, the categories should rather be considered as gameplay preferences or motivations, which can affect playstyles but do not define them.

More recent research on playstyle has provided numerous typologies that are similar to Bartle’s, such as veterans, solvers, pacifists and runners (Drachen et al., 2009) or puzzle-solvers, detectives goal-seekers and explorers (Valls-Vargas et al., 2015; Jaćević, 2011). Bean and Groth-Marnat (2016) divide styles between player versus player, player versus environment and role-play. Styles have also been categorised through a widely used personality measure called the Big Five Inventory, which classifies personality based on the domains of openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism (Bean & Groth-Marnat, 2016; Tekofsky et al., 2015).

As with Bartle’s formulation, I argue that such player classifications are related to gameplay motivations rather than playstyles, because they pertain to choosing what goal to pursue rather than how to pursue it. In other words, gameplay preferences and motivations are related to what is done, not to how something is done. Such motivations can influence playstyle; for example, an explorer, who prefers to explore their own goals within the game or engage with its narrative details, might play in a more relaxed and carefree manner, whereas a goal-seeker’s style might be dictated by speed and efficiency. However, the connection between gameplay motivation and playstyle is not a necessary one.

Instead of using psychological profiles, players can also be categorized by their strategic styles. For example, Eggert et al. (2015) identify playstyles as roles that are established informally among players in multiplayer games; examples of such roles may include taking on different supporting and attacking strategies. However, the same role could also be played with different styles. This is more evident with formally established roles, such as character classes in role playing games. While they can be viewed as strategic choices, the same class can also be played with different styles.

Different attempts to classify players according to their gameplay behaviour risks disregarding more nuanced variations in the styles of play, as especially the pre-made personality classifications tend to define styles beforehand. While style and personality might be connected, it is also questionable whether style affects personality or vice versa. For example, Jenewein (2024) has differentiated between individual, collective, expressive and constructive interpretations of style. Styles can pertain to individual persons but also to collective movements or historical epochs, and styles can be considered in terms of self-expression or self-construction. According to Jenewein, expressive interpretations have emphasised that style is either an expression of authentic and original individuality, or an expression of collective identities. Constructive viewpoints have regarded style as impersonal in the sense that it precedes individuality -- people rather become individuals and construct their belonging to different groups by learning and reproducing styles. Jenewein argues that style and the self should not be thought as separate entities; instead, style is the relation of human beings to the world (Jenewein, 2024).

I have previously argued that playstyle is related to the continuous process of self-formation through sharing and cultivating embodied habits rather than expressing or revealing the personality of the player (Kalmanlehto, 2025). However, playstyle does not necessarily correspond to one’s personal style. Regarding the difference between personal and artistic style, Riggle (2015) argues that personal style is not an expression of the actual self but rather an ideal that one aspires to be. Artistic style is also a presentation of ideals, but instead of presenting personal ideals, it is a presentation of ideals that the artist has for their art. According to Riggle, artistic style is not merely the selection and application of an artistic technique for solving an artistic problem, but rather discovering the solution and technique through practice, and artistic style is reflected in the results of this activity. Riggle’s examples of potential artistic ideals include expressing a clean simplicity in visual arts, or to be bold, sparse, perceptive or compassionate writer (Riggle, 2015). Most importantly, while the artist’s personality and physiology play a role in the development of style, artistic ideals are free to be completely different from the artist’s non-artistic ideals.

Even if one’s personal ideals could overlap with the artistic ones, Riggle’s argument supports the idea that artistic and personal styles are not necessarily connected. This suggests that there is no necessary connection between playstyle and personality either. On the contrary, games allow players to experiment with different styles and find aesthetic enjoyment in them. Although Riggle’s argument focuses exclusively on artistic style, it applies also to non-artistic playstyles that have an aesthetic motivation. While not guided by artistic ideals, such styles can be motivated by the player’s understanding of what kind of gameplay feels aesthetically enjoyable for them. I will settle here for differentiating between playstyle and personal style, and will not pursue further the theme of self-formation through stylistic variations. In the next part, I inspect closer how playstyle as the player’s aesthetic appreciation of goal-oriented play differs from strategic optimisation and how such style is connected to habit.

Strategic Optimisation and Aesthetic Habits

Previously, playstyle has been considered as a rather broad category: for example, Tekofsky et al. defined style as “any (set of) patterns in game actions performed by a player” (Tekofsky et al., 2015, p. 3). In my view, this is not precise enough to demarcate aesthetic playstyle, as games can be played in a wide variety of manners that are not related to the aesthetic appreciation of one’s way of playing. To understand playstyle in terms of goal-oriented gameplay, I follow the work of Suits (1978) and Nguyen (2020a), who have argued that playing games is an attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles. In Nguyen’s view, agency is the aesthetic medium of games. Games are artefacts that frame different kinds of practical agencies for players to enact; specifically, a game features an arbitrary goal that the player voluntarily strives to achieve. By temporarily adopting the agential posture framed by the game’s structure, players can appreciate aesthetically their own enactment of different agencies. It is important to note that these agential modes are abstract: they do not signify verbally but are experienced, for example, as graciously executed manoeuvres instead of representations or fictions.

My purpose is not to insist upon the Suitsian definition of games or Nguyen’s claim that agency is the aesthetic medium of games, but rather to conceptualise gameplay as a practical goal-oriented action that is engaged in for its own sake. Hence, I approach playstyle as the mode of the player’s interaction with the goal-oriented game mechanics and the rules of the game, which could be referred to as mechanical agency (Cole and Gillies, 2021). In games that do not have explicit goals or difficult obstacles, the player nevertheless interacts with the game mechanics, and the player’s way of navigating such interactions can be viewed as their playstyle.

To view playstyle as the player’s aesthetic preference means seeing a way of playing as valuable as such, regardless of its effectiveness or visual spectacularity. However, the design elements of a game might impose restrictions on the player’s freedom to vary their style, as for example an impractical style that constantly leads to death might render gameplay unenjoyable, although such style could have aesthetic value as an artistic performance. Purposelessness has often been considered a key element of art and aesthetic experience, and my view of playstyle also suggests that players can engage in goal-oriented tactical and strategic choices for their aesthetic value rather than their effectiveness. A similar view has been proposed by Nguyen with the notions of “disinterested interestedness” and “impractical practicality” (Nguyen, 2020a, p. 117), which refer to the player’s disinterested, aesthetically motivated attitude to the very interestedness that is part of goal-oriented play. Nguyen argues that the striving towards a game’s goal enables the aesthetic experience of the agential posture through which the goal is achieved, but my conception of playstyle suggests that suboptimal styles of playing can also be aesthetically valuable.

Some empirical approaches have focused on goal-oriented playstyles by analysing different kinds of gameplay data. For example, Drachen et al. (2009) measure game completion time, total number of deaths, number of puzzle hints used and different causes of deaths. Additionally, Gow et al. (2012) measure the frequency of key presses, ineffective key presses, the distance from obstacles, wall hits and scores in a snake game, as well as character movement and the use of cover in a third-person shooter game. Mader and Tassin (2022) investigate playstyles in a Tetris game in terms of how players turn the blocks, how skilfully they clear the rows and the height of the ceiling.

Some researchers have also approached playstyles by analysing gameplay databases and forming clusters of player types through statistical analysis (e.g., Gow et al., 2012; Eggert et al., 2015; Tekofsky et al., 2015). However, as Mader and Tassin (2022) have noticed, such approaches tend not to provide interpretations of the playstyles in question. The data contain information that is mostly related to competitive gameplay performance, which makes playstyle primarily a question of skill. Factors such as kill count, shots fired and hits per shot in a first-person shooter (Tekofsky et al., 2015) can be relevant for identifying playstyles, but are more related to how efficiently the goal of the game is achieved than to style as the way of achieving that goal. Although varying one’s playstyle can require skill, different playstyles might also lead to similar performances in terms of scores and kill counts.

The demand of skill in difficult games is not trivial for playstyle, as a lack of adequate skill also restricts variations of styles. In order to experience gameplay aesthetically, a player must be able to overcome the game’s obstacles. However, skill alone does not determine playstyle, if such skill is not used for aesthetic purposes. A player might play technically well, but in a manner that feels mechanical or monotonous, without any enjoyment in their way of playing. Working out for oneself how a game functions might provide more opportunity for the development of an aesthetically valuable style, whereas looking up the most efficient way to play from an online guide can force the player’s style into a predefined optimised strategy. As Riggle (2015) noticed, forming a style is not a question of simple problem solving but a reflective process of discovering a technique through practice.

In competitive gaming, as in all sports, style is often seen as a matter of performance and winning strategy. Even in single-player games, the player’s aim to complete the gameplay task can become a matter of optimisation. Juul (2018) raises concerns that the importance of optimisation, caused by game designs that emphasise difficulty and skill, threatens to impair players’ ability to appreciate games aesthetically. I argue that playstyle as an aesthetically pleasing way to play could mitigate such concerns, because instead of optimisation, players are focusing on exploring the different ways of playing afforded by the game mechanics. Notably, Leino (2020) argues that the game designer’s artistry and the player’s performance are in conflict; if a game has unambiguous rules, the player’s performance, style and self-realisation come to the foreground, while the designer’s aesthetic ideas become displaced. Conversely, according to Leino, games that remove failure conditions and the demand of skill preserve the designer’s artistry, but make the player a passive audience [3].

However, if the very act of striving to overcome a game’s obstacles is considered aesthetically valuable, then playstyle can be also a way to shape one’s gameplay into an aesthetically pleasing action. Thinking of style as an aesthetic mode of gameplay through a reflection of how the game mechanics are designed also alleviates Leino’s concerns regarding the conflict of artistry and gameplay. Moreover, if playstyle is considered primarily as an aesthetic but not necessarily artistic phenomenon, the aesthetic appreciation of one’s own way of playing might not be in direct opposition to the designer’s artistic intent. If gameplay is considered to involve an aesthetic experience of practical action, instead of players playing for the sake of winning or completing the game, playstyle becomes guided by aesthetic values instead of strategy and optimisation. Difficult games demand optimal strategies, but tend to also leave room for stylistic variation in those strategies, which enables aesthetic enjoyment of even the optimisation of gameplay itself.

Although aesthetic playstyles can be viewed as a counterpoint to strategic optimisation, they are not always deliberately sought by players. Because they are dependent on both the design of the game and the player’s dispositions, playstyles have a dual nature between passivity and activity, a distinction which has been discussed under the notion of habit. Jaćević (2021) argues that playstyle is affected by two factors: elements of the game design and the player’s ludic habitus. The former, elements of the game design, refers to all parts of the game, whereas the ludic habitus is, in Jaćević’s terms, “the collection of [the player’s] game-domain-related experiences, knowledges and attitudes” (Jaćević, 2021). All design elements can indeed affect playstyle, but as I have argued, only goal-oriented elements of gameplay comprise playstyle. As games restrict the ways in which they can be played, and since game design can suggest different ways to play, style is not completely dependent on the player. The styles that the player brings into play can also be accidental or not consciously chosen, because habitual ways of playing games may be accumulated from previous gameplay experiences, the surrounding game culture and other players.

As with Nguyen’s conception of agency, the meaning of playstyle does not operate on the level of verbal meaning. For example, the way a person speaks affects how their words are interpreted and can change their meaning without altering the content of the phrase, although such variations may go unnoticed even by the speaker. Indeed, many areas of style, such as fashion or ways of speaking, are acquired without notice through the accumulation of habits and subtle nudges from the individual’s culture (Portera, 2022). While style can be constructed deliberately, it often operates inconspicuously in the background of one’s actions. In this context, it is clear that playstyle can be formed at will, but is also constructed through the accumulated experiences and skills of the player, even though they may be unaware of this. Particularly difficult games can condition players into habitual ways of playing, where optimisation of strategy can lead to a disregard for the aesthetic enjoyment of playstyle.

Consequently, in some ways style is sought and performed, while in other ways it is adopted without noticing. This latter aspect of style is formulated based on impressions left to the individual by others; in this way, style simultaneously characterises persons and deprives them of proper originality, as style is an imprint that precedes conscious actions (Lacoue-Labarthe, 1971). In a similar manner to this interpretation of style, Carlisle (2014) characterizes habit as a twofold concept that can refer both to automated patterns of actions that are acquired without the individual noticing, and to consciously developed skills. According to Carlisle, an action becomes a habit when it is repeated, but deliberately formed habits transform into practices. Camilleri (2018) argues that habit has often been viewed as a passive and numbing tendency, whereas benevolent habits have been discussed under more positive terms, such as practice or habitus. Regarding style, these conceptions of habit as a twofold concept correspond to the descriptive and evaluative uses of style. Although I thematise style as an aesthetic practice, this does not mean that styles cannot be also passive tendencies. For style to be distinguishable, it needs to have a degree of consistency and repeatability, which in the context of goal-oriented play leads to habitual patterns of action.

As with styles, habits are contagious and often acquired through social life, as people tend to imitate others. However, habits can also be consciously formed, especially when practicing an action that requires skill, such as playing a game. Zhu (2023) argues that especially in high-skilled competitive gameplay situations, players need to learn proper gameplay actions and then ensure that these become habitual and automated. This process is necessary for any action that requires finesse, but Zhu highlights that this is also true for slower-paced games, where the complexity of the gameplay situation prevents the calculation of all possible affordances. Overall, games tend to require tacit knowledge, and players can possess this in the form of automated habits.

Although style can be thematised as an aesthetic habit, all habits are not styles. Any action can become a habit when it is repeated, but style refers to how such action is enacted. Hence, a habit of doing something involves another habit of doing it in a certain style. However, while style can be varied, it becomes distinct only when repeated. Developing a characteristic way of playing in an aesthetically valuable style requires that a player reflects on the aesthetic value of their own gameplay. Such transformation of habits of playing into aesthetic practices may also require the development of skills to play in a certain way. For example, in Signalis an aggressive and reckless playstyle requires less knowledge of the game mechanics than a fast and stealth-oriented style of play. In the next section, I investigate in greater detail how such choices in Signalis are related to different styles of play, and how the game uses gameplay metrics to provide its own interpretation of the player’s style.

The Endings of Signalis as an Interpretation of Playstyle

Here, I analyse playstyles in Signalis as an example of making stylistic variations as an aesthetic choice. While any game could be used to analyse style, the game design of Signalis emphasises style in an interesting way by determining its narrative closure through gameplay statistics that, in my interpretation, define the playstyle of the finished playthrough. Signalis is a survival horror game in which the player controls a character named Elster. The game is viewed from a top-down perspective, aside from a few story-focused first-person sequences. The main gameplay mechanics include navigating corridors, exploring rooms, collecting items, solving puzzles and dealing with numerous enemies while managing a limited inventory and equipment. The design of the game borrows significantly from similar earlier titles, such as Silent Hill (Team Silent, 1999), Resident Evil (Capcom, 1996) and their sequels.

In Signalis, sneaking, fighting and fleeing are the main options for dealing with the game’s enemies, and can mark the difference between, for example, cautious and reckless playstyle. Elster remains undetected by enemies if she keeps enough distance from them or is not in their line of sight, whereas running or firing a weapon causes nearby enemies to attack her. The maps of the game are interconnected with unlockable doors and one-way shortcuts, providing different options for navigation. An explorative playstyle requires killing the enemies in order to search every room, whereas a hastier approach might demand sprinting past them and collecting only necessary items. A combat-oriented approach to the game also requires the player to sacrifice limited inventory slots for weapons and ammunition, which leads to running back and forth between different locations to collect necessary items, such as keys. Puzzles, such as those involving determining keycodes or radio frequencies are also an essential part of Signalis. As each puzzle has only one solution, and they do not offer room for stylistic variations. However, to locate clues to puzzles, the player must pay attention to the game environment, read in-game documents and listen to the monologues of NPCs, thus encouraging a playstyle that focuses on exploring the areas.

Signalis interweaves the player’s style of play with the meaning of the game’s narrative, which not only makes the game an example of ludonarrative harmony (e.g., Saldivar, 2022) but also highlights how game designers can incorporate the player’s own performance and stylistic variations into the narrative. However, my purpose here is to interpret not the narrative of the game, but the playstyles afforded by its game mechanics. The narrative events of the game always play out in a similar way, until the ending. After the final combat section of the game, the story branches into three different outcomes, which, at this point, cannot be changed by the player, as they are determined by hidden gameplay statistics. There is also a fourth ending that is obtained by collecting hidden items, but is unaffected by the factors determining the other endings.

The ending mechanics of Signalis are similar to those of the influential survival horror game Silent Hill 2 (Team Silent, 2001), which has multiple endings. In Silent Hill 2, the player unlocks the endings through gaining points from certain in-game actions. However, most of those actions are focused on the narrative, such as reading letters and listening to conversations, although the average health and stamina levels of the playable character also affect the ending. In contrast, Signalis does not provide the player with any type of narrative or ethical choice to decide the ending, instead employing a strictly technical approach to deciding how the story will play out.

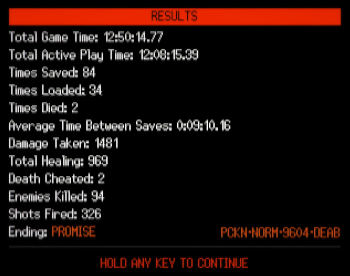

When the game ends, the name of the ending and certain statistics of the playthrough are revealed to the player on a results screen, like those in previous survival horror games (Figure 1). The list includes the name of the ending, hence the game hints that there are different endings which might be affected by such factors. But there is no indication of how these factors have affected the ending. The endings are named “Leave,” “Memory” and “Promise” -- all of which refer in some way to a promise Elster attempts to fulfil. In the “Leave” ending, Elster is ultimately unwilling to carry out the promise. In “Memory,” Elster attempts to fulfil the promise but fails to do so because another character does not remember it. In “Promise,” she succeeds in the task.

Figure 1. Results screen, Singalis (Rose-engine, 2022). All screenshots taken by author.

Both the Endings (2024) page on the Singalis Wiki and a guide in Steam user forums (Timbrewolf, 2024) list different sets of factors that determine the ending, which are claimed to be based on data mined from the game files. Another Signalis Wiki (Endings, 2025), based on a more recent guide in Steam Community (Death is Coming, 2024), lists the same factors, which are claimed to be obtained by testing with a debugging tool. The newer guide is based on a more recent version of the game, while the other is based on the initial release. It is not possible to verify this information comprehensively, but for the sake of simplicity, I have analysed the ending mechanics as stated in the more recent Signalis Wiki. Even though these mechanisms represent only one possible way in which the game’s ending is determined, this analysis functions as a suitable example of how variations in playstyle can be affected and interpreted by game design.

The list of factors and points for determining the ending are listed in the Table 1. I have modified the names of the variables for readability.

|

Variable |

Points to ending |

|

New game |

+2 to Memory |

|

Less than 6 hours of active play time |

+2 to Memory |

|

More than 12 hours of active play time |

+1 to Promise |

|

More than 5 minutes of health regeneration time |

+2 to Promise |

|

More than 1900 points of damage taken |

+1 to Promise |

|

More than 8 near death survivals |

+1 to Promise |

|

More than 5 deaths |

+1 to Promise |

|

More than 90 enemies killed |

+1 to Promise |

|

More than 120 enemies killed |

+1 to Promise |

|

More than 25 unique NPC interactions |

+1 to Leave |

|

More than 35 unique NPC interactions |

+1 to Leave |

|

More than 60 % of active play time over 80 % of maximum health |

+1 to Leave |

|

More than 80 % of active play time over 80 % of maximum health |

+1 to Leave |

|

More than 5 minutes spent in memory sequences |

+1 to Leave |

|

Interacting with inaccessible doors more than 40 times |

+1 to Leave |

Table 1. Signalis ending factors, based on wiki.gg Singalis Wiki (Endings, 2025).

Active play time excludes time spent in menus, inventory, dialogue, notes and loading screens. Health regeneration time refers to a mechanic that passively recovers part of Elster’s health if it drops to a low level. Near death survivals occur when Elster’s health is over a critical threshold, and she receives fatal damage; instead of dying, this causes her health drop to a critical level. The number of interactions with NPCs are counted until there is no new content available from the same NPC. Each statistic gives points towards an ending, and the game chooses the ending with the highest points.

To obtain the “Memory” ending, the player needs to avoid receiving too many points for the other endings and complete the game quickly. Therefore, this ending requires a meticulous and systematic playstyle, in which the player completes the game in a fast and efficient manner, i.e., does not kill many enemies, ignores NPCs, and keeps their health below the threshold that gives points for the “Leave” ending. They must do this without taking too much damage to avoid points for the “Promise” ending. The player will also receive the “Memory” ending if there is a tie in points between the “Promise” and “Leave” endings. However, obtaining a tie between “Promise” and “Leave” might be difficult to calculate and is perhaps based more on luck.

The “Leave” ending is a result of a safety-oriented playstyle, in which the player needs to stay in full health and have a moderate completion time. This ending also requires investment in the gameworld, highlighted by the need to interact with NPCs multiple times to exhaust their monologues, and to linger in memory sequences where there are no enemies. Trying repeatedly to open doors that are already marked unopenable can also be interpreted thematically as a desire to leave rather than a stylistic variation related to the main gameplay task. However, an attempt to interact with everything and explore every location thoroughly could represent also an explorative or slow-paced playstyle.

The points given for the “Promise” ending seem to relate to an aggressive and reckless playstyle, in which the player kills many enemies, takes considerable damage, does not prioritise healing or stealth, has their health dropped to a critical level often and dies multiple times. Long play time could be a result of unsystematic exploration, becoming lost or backtracking, which might also be a result of an impulsive style of play. However, the mere need to carry weapons and ammunition can also result in a longer playtime, as the player might not have enough inventory slots to collect key items, which can force them to revisit previously explored locations.

As every ending allows the player to also gain points for the other endings, the scoring system allows for variation in the styles of play. The “Memory” ending has the strictest requirements, as the maximum of four points is easily surpassed by the six and seven points available for the “Leave” and “Promise” endings. Interestingly, the factors related to the choice of ending are similar to statistics that have been related to style of play in empirical research (e.g., Tekofsky et al., 2015). These factors also incorporate differences between role-based play and goal-oriented play, as talking to other characters and lingering in memory sequences is not relevant for proceeding in the game. However, this mostly affects the possibility to obtain the “Memory” ending, as the “Promise” ending can be obtained even while gaining multiple points for the “Leave” ending.

As Signalis emphasises challenging gameplay with hostile environments and a scarcity of resources, the playstyles it encourages are tied to the player’s tactical and strategic decisions. However, instead of making style a matter of optimising gameplay performance, Signalis interweaves different styles into the game’s fiction. Fierce and risky gameplay might emphasise Elster’s craving to fulfil the promise at all costs, which results in the “Promise” ending, whereas a more careful playstyle might suggest that she is overly occupied by the gameworld and its inhabitants and not dedicated enough to carry out the promise, leading to her refusing it in the “Leave” ending. Finally, an efficient and calculated playstyle might signal dedication to reach the final goal but in an unpassionate manner, which makes the promise meaningless for the other character. Such interpretations could be developed further using all the narrative details of the game, but this is not within the scope of the current study.

It is also possible that the way Signalis clusters different styles into its various endings does not correspond to a player’s own interpretation of their playstyle. As with the research that categorises different ways of playing into certain types through clustering gameplay data, the ending system of Signalis categorises playstyles through predefined interpretations. However, Signalis does not imply that playstyle should be connected to the player’s personality but instead links their playstyle to the emotional states of the playable character. As the game does not reveal how the statistics affect the ending, it leaves the player free to play in any style. While some endings may be considered more difficult to obtain, their requirements are not directly linked to the player’s skill.

Overall, Signalis guides the player into forming habitual ways to overcome its obstacles while simultaneously allowing variation in them. While the connection between the ways of playing the game and its narrative elements could indicate ludonarrative harmony, the style is also constructed through the player’s ludic habitus. Signalis makes its message dependent on the player’s style instead of merely attempting to bridge the gap between narrative and game mechanics.

Through its thematic approach to different ways of playing, Signalis highlights the aesthetic relevance of playstyle. The game does not interpret styles in terms of competitive performance or skill, but rather as different ways to complete the practical gameplay task of navigating through the game environment and avoiding damage from enemies. Linking the gameplay statistics to narrative outcomes suggests a predefined interpretation of different styles of play, although this may not have been the developer’s intention. The factors that are used for selecting narrative outcomes do not alone determine playstyle, because style could also be manifested through variations in the player’s physical input, due to twitchiness, unnecessary keypresses, or the player’s attention to different details on the screen. As gameplay data can only indicate style from the perspective of the game’s procedural system, it cannot be used to fully capture the more subtle variations of style. Playstyle can include almost completely unnoticeable phenomena, such as a habitual way of moving one’s hands and fingers on the keyboard, shifts in the player's attention to the changing affordances (Peacocke, 2021) or the rhythms of micro-level game interactions (Costello, 2018; Kalmanlehto, 2024).

Conclusion

In this article, I have formulated a conception of playstyle as an aesthetic attitude to the way of enacting practical, goal-oriented gameplay tasks. By considering such style as habit, I have highlighted how it is affected by both the player’s deliberate aesthetic attitude, and the tacit influences of game design and the player’s accumulated experiences. The previous research on playstyle has tended to focus either on competitive gameplay, in which the question of style is considered in terms of winning strategies, different gameplay preferences and motivations, such as roleplaying or problem-solving, or player typologies. Such research has often discussed playstyle as an indicator of personality traits by inspecting styles through the perspective of predefined personality categories. Some previous research has also focused on the types of actions that define different styles, without elaborating on what the styles are in practice. I have highlighted the importance of playstyle as an aesthetic phenomenon, which allows players to reflect the aesthetic value of their own actions and agencies in gameplay.

Identifying different styles is challenging because styles often operate outside of verbal meaning. Instead of having distinct conceptual meanings, playstyles are more related to embodiment, moods, rhythms and affective states. Hence, interpretations of different styles tend to remain open-ended. Indeed, discussions on philosophical aesthetics have noted how difficult it is to describe aesthetic experiences or the beautiful through specific concepts (e.g., Sibley, 1959). Furthermore, the problem of interpreting playstyles is part of a more general question of how games are interpreted, and could be further addressed by integrating theories of game hermeneutics, such as Arjoranta’s notion of ludo-hermeneutics (Arjoranta, 2022). However, the purpose of the current article has been to highlight the aesthetic relevance of style as a form of practical action in gameplay, and investigating more specific questions about the interpretations of such styles require further research.

By detaching playstyle from gameplay preferences, narrative agency and the choice of what goals to pursue, playstyle can be defined as a style of instrumental and practical action that makes the action aesthetically valuable for the player. Game developers can influence the ways in which a game can be played and even incorporate different playstyles into the narrative of the game, as exemplified by the ending mechanics of Signalis. While such predefined interpretations of styles might not always correspond to how players experience their playstyles, this type of game design emphasises that playstyle does not need to be a matter of strategy optimisation or taking control of the ludic system, but can instead be a way of playing that makes the action of accomplishing practical gameplay tasks aesthetically valuable.

While playstyle may be distinct from personal style, just as narrative and moral choices in games can occur through curiosity or for the sake of roleplaying, there is nevertheless a connection between style and subjectivity. However, asking whether individuals repeat their personal styles through gameplay or whether players can be categorised in terms of their gameplay preferences is not relevant for understanding the aesthetic experience of playstyle. Instead, it is possible to consider how players can mould themselves through variations in playstyles, as I have argued in my previous research on the relation between playstyle and subjectivity (Kalmanlehto, 2025).

Nguyen suggests that by playing a variety of different games, players can expand their agential repertoires, as games communicate different agential orientations and styles (Nguyen, 2020a, p. 98). Regarding playstyles, different games also encourage different styles through their design and the options available for players. However, style is not wholly dependent on a game’s design elements; instead, style is formed through the integration of the game design and the player’s habitual gameplay practices. As a way of engaging in practical gameplay action, playstyle is not equal to artistic style, nor is it identical to the styles of everyday practices, which are not constrained by predefined mechanics as gameplay. Hence, this notion of playstyle allows for an understanding of the aesthetic experience that pertains specifically to playing games, even though the question of the interpretation of different styles may remain unanswered.

Endnotes

[1] For example, Kallio et al. (2011) have explored different ways to play games in terms of gaming mentalities and practices of play.

[2] By gameplay I refer to the process of playing a game, which includes both the game and the player. For example, Leino (2012) has described gameplay as an ontological hybrid that is shaped by both the player and the game.

[3] The question of power is a fundamental problem in game studies, often traced back to Gadamer, who claimed that “all playing is being-played” (Gadamer, 2004, p. 106), and more recently addressed by e.g., Mäyrä (2019) in terms of hybrid agency.

References

Arjoranta, J. (2022). How are Games Interpreted? Hermeneutics for Game Studies. Game Studies, 22(3). https://gamestudies.org/2203/articles/arjoranta_how_are_games_interpreted

Bartle, R. (1996). Hearts, clubs, diamonds, spades: Players who suit MUDs. Journal of MUD Research, 1(1).

Bean, A., & Groth-Marnat, G. (2016). Video gamers and personality: A five-factor model to understand game playing style. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 5(1), 27-38. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000025

Bialas, M., Tekofsky, S., & Spronck, P. H. M. (2014). Cultural Influences on Play Style: Computational Intelligence and Games (CIG). Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computational Intelligence in Games, 271-277. https://doi.org/10.1109/CIG.2014.6932894

Bonsdorff, P. von. (2023). Aesthetic Practices. In V. Vinogradovs (Ed.), Aesthetic Literacy Vol. II: Out of Mind (pp. 30-37). Mongrel Matter.

Bontchev, B., & Georgieva, O. (2018). Playing style recognition through an adaptive video game. Computers in Human Behavior, 82, 136-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.12.040

Camilleri, F. (2018). On habit and performer training. Theatre, Dance and Performance Training, 9(1), 36-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443927.2017.1390494

Capcom. (1996). Resident Evil [Sony PlayStation]. Digital game directed by Shinji Mikami, published by Capcom.

Carlisle, C. (2014). On Habit: Thinking Action. Routledge.

Cole, T., & Gillies, M. (2021). Thinking and Doing: Challenge, Agency, and the Eudaimonic Experience in Video Games. Games and Culture, 16(2), 187-207. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412019881536

Costello, B. M. (2018). The Rhythm of Game Interactions: Player Experience and Rhythm in Minecraft and Don’t Starve. Games and Culture, 13(8), 807-824. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412016646668

Death is Coming. (2024). Ending Requirements 1.2.1 Updated 4/6/24 [Online post]. Steam Community. https://steamcommunity.com/sharedfiles/filedetails/?id=3070353184

Dickie, G. (1974). Art and the Aesthetic: An Institutional Analysis. Cornell University Press.

Drachen, A., Canossa, A., & Yannakakis, G. N. (2009). Player modeling using self-organization in Tomb Raider: Underworld. 2009 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Games, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1109/CIG.2009.5286500

Eggert, C., Herrlich, M., Smeddinck, J., & Malaka, R. (2015). Classification of Player Roles in the Team-Based Multi-player Game Dota 2. In K. Chorianopoulos, M. Divitini, J. Baalsrud Hauge, L. Jaccheri, & R. Malaka (Eds.), Entertainment Computing -- ICEC 2015 (pp. 112-125). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24589-8_9

Endings. (2024, May 20). In Fandom Signalis wiki. https://signalis.fandom.com/wiki/Endings

Endings. (2025, June 26). In wiki.ggSignalis wiki. https://signalis.wiki.gg/wiki/Endings

Gadamer, H.-G. (2004). Truth and method. (J. Weinsheimer & D. G. Marshall, Trans.) (2., rev. ed). Continuum.

Gow, J., Baumgarten, R., Cairns, P., Colton, S., & Miller, P. (2012). Unsupervised Modeling of Player Style With LDA. IEEE Transactions on Computational Intelligence and AI in Games, 4(3), 152-166. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCIAIG.2012.2213600

Gualeni, S., & Vella, D. (2020). Virtual Existentialism: Meaning and Subjectivity in Virtual Worlds. Palgrave Pivot. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-38478-4

Ingram, B., van Alten, C., Klein, R., & Rosman, B. (2023). Generating Interpretable Play-style Descriptions through Deep Unsupervised Clustering of Trajectories. IEEE Transactions on Games, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1109/TG.2023.3299074

Jaćević, M. (2021). How the Players Get Their Spots: A Study of Playstyle Emergence in Digital Games. 2021 IEEE Conference on Games (CoG), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1109/CoG52621.2021.9619067

Jenewein, M. (2024). Wölfflin and Wiesing. Style as a Principle of Anthropological Thinking. Aisthesis, 17(1), 301-316. https://doi.org/10.7413/2035-8466020

Juul, J. (2018). The Aesthetics of the Aesthetics of the Aesthetics of Video Games: Walking Simulators as Response to the problem of Optimization. 12th International Conference on the Philosophy of Computer Games Conference, Copenhagen.

Kallio, K. P., Mäyrä, F., & Kaipainen, K. (2011). At Least Nine Ways to Play: Approaching Gamer Mentalities. Games and Culture, 6(4), 327-353. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412010391089

Kalmanlehto, J. (2024). Aesthetics of Agency and the Rhythm of Gameplay. Games and Culture,19(8), 1038-1054. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120231185630

Kalmanlehto, J. (2025). Style Makes the Player? The Relation between Playstyle, Aesthetics and Subjectivity. ACM Games, 3(2), 13:1-13:15. https://doi.org/10.1145/3721120

Lacoue-Labarthe, P. (1979). Le sujet de la philosophie (typographies 1). Flammarion.

Leino, O. T. (2020). The Tragedy of the Art Game. DiGRA ’20 -- Proceedings of the 2020 DiGRA International Conference: Play Everywhere. http://www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/DiGRA_2020_paper_232.pdf

Leino, O. T. (2012). Untangling Gameplay: An Account of Experience, Activity and Materiality Within Computer Game Play. In J. R. Sageng, H. Fossheim, & T. Mandt Larsen (Eds.), The Philosophy of Computer Games (pp. 57-75). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4249-9_5

Mader, S., & Tassin, E. (2022). Playstyles in Tetris: Beyond Player Skill, Score, and Competition. In B. Göbl, E. van der Spek, J. Baalsrud Hauge, & R. McCall (Eds.), Entertainment Computing - ICEC 2022 (pp. 162-170). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-20212-4_13

Nguyen, C. T. (2020a). Games: Agency As Art. Oxford University Press.

Nguyen, C. T. (2020b). The Arts of Action. Philosophers’ Imprint, 20(14), 1-27.

Normoyle, A., & Jensen, S. (2015). Bayesian Clustering of Player Styles for Multiplayer Games. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Entertainment, 11(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1609/aiide.v11i1.12805

Oxford University Press. (2023, December). Style (n.). In Oxford English Dictionary, retrieved February 3, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/4127274906

Peacocke, A. (2021). Phenomenal experience and the aesthetics of agency. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 48(3), 380-391. https://doi.org/10.1080/00948705.2021.1952879

Portera, M. (2022). Aesthetics as a Habit: Between Constraints and Freedom, Nudges and Creativity. Philosophies, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies7020024

Queneau, R. (1947). Exercices de style. Éditions Gallimard.

Riggle, N. (2015). Personal Style and Artistic Style. The Philosophical Quarterly, 65(261), 711-731.

Ravari, Y. N., Bakkes, S., & Spronck, P. (2018). Playing styles in starcraft. European GAME-ON Conference on Simulation and AI in Computer Games. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Yaser-Norouzzadeh/publication/327837683_PLAYING_STYLES_IN_STA RCRAFT/links/5ba8bba792851ca9ed2180d4/PLAYING-STYLES-IN-STARCRAFT.pdf

Ravari, Y. N., Strijbos, L., & Spronck, P. (2022). Investigating the Relation Between Playing Style and National Culture. IEEE Transactions on Games, 14(1), 36-45. https://doi.org/10.1109/TG.2020.3025042

Rose-engine. (2022). Signalis [Microsoft Windows]. Digital game directed by Yuri Stern, published by Humble Games and Playism.

Saldivar, D. (2022). Cyberpunk 2077: A case study of ludonarrative harmonies. In Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds (Vol. 14, Issue Cyberpunk 2077, pp. 39-50). Intellect. https://doi.org/10.1386/jgvw_00050_1

Shusterman, R. (2011). Somatic Style. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 69(2), 147-159. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6245.2011.01457.x

Sibley, F. (1959). Aesthetic Concepts. The Philosophical Review, 68(4), 421-450. https://doi.org/10.2307/2182490

Siefkes, M., & Arielli, E. (2018). The aesthetics and multimodality of style: Experimental research on the edge of theory. Berlin: Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/978-3-653-07090-3

Suits, B. (1978). The Grasshopper: Games, life and utopia. University of Toronto Press.

Swink, S. (2009). Game feel: A game designer’s guide to virtual sensation. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers/Elsevier.

Tekofsky, S., Spronck, P., Goudbeek, M., Plaat, A., & van den Herik, J. (2015). Past Our Prime: A Study of Age and Play Style Development in Battlefield 3. IEEE Transactions on Computational Intelligence and AI in Games, 7(3), 292-303. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCIAIG.2015.2393433

Tekofsky, S., Spronck, P., Plaat, A., van den Herik, J., & Broersen, J. (2013). Play style: Showing your age. 2013 IEEE Conference on Computational Intelligence in Games (CIG), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1109/CIG.2013.6633616

Team Silent. (1999). Silent Hill [Sony PlayStation]. Digital game directed by Keiichiro Toyama, published by Konami.

Team Silent. (2001). Silent Hill 2 [Sony PlayStation 2]. Digital game directed by Masashi Tsuboyama, published by Konami.

Timbrewolf. (2022). Endings Requirements. Attempting to puzzle out the different endings for Signalis [Online forum post]. Steam Community. https://steamcommunity.com/sharedfiles/filedetails/?id=2881225317

Valls-Vargas, J., Ontañón, S., & Zhu, J. (2015). Exploring Player Trace Segmentation for Dynamic Play Style Prediction. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Entertainment, 11(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1609/aiide.v11i1.12782

Vella, D. (2021). Beyond agency: Games as the aesthetics of being. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 48(3), 436-447. https://doi.org/10.1080/00948705.2021.1952880

Zhu, F. (2023). The Intelligence of Player Habits and Reflexivity in Magic: The Gathering Arena Limited Draft. Angelaki, 28(3), 38-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969725X.2023.2216545